#but like if i do go for MA/MFA then I mean what's the point in stopping there ya get me?

Text

i've been out of academia so long (less than a year) that i forgot there were various citation styles

#anyway chicago ftw#mla is okay I GUESS#apa is annoying af#i saw a poll about it and that's why i'm thinking about it#haunted bc the two departments i was a student of only accepted extremely specific styles of citation#(IHS for history and a semi-adapted version of Chicago for German)#i miss the self-hatred i'd generate adding all the information into the footnotes AFTER writing my piece#idk man i think in terms of academia i'm a bit of a masochist LOL#also i just miss not having drama w my profs??? one dude tried to make my life so hard for no damn reason#and then i slayed while simultaneously proving i had a backbone and he was so taken aback by that#i hope the prof nearly the entire class had a crush on is doing well <3#we nicknamed ourselves [Prof's name]'s Angels#...y'know...like Charlie's Angels...#anyway yeah lol#roacc#Y'ALL I'M AFRAID I'LL END UP GOING FOR A MASTERS BC IK IF I TRY GO FOR A MASTERS THEN I'LL END UP W A PHD#IDEK WHAT I'D WANNA DO A MASTERS IN LET ALONE PHD#but like if i do go for MA/MFA then I mean what's the point in stopping there ya get me?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2. Natalia Nakazawa & Nazanin Noroozi

Natalia Nakazawa and Nazanin Noroozi discuss their use of archives and photographs, creating hybrid narratives, cultural transmission, and the formation of personal and cultural memories.

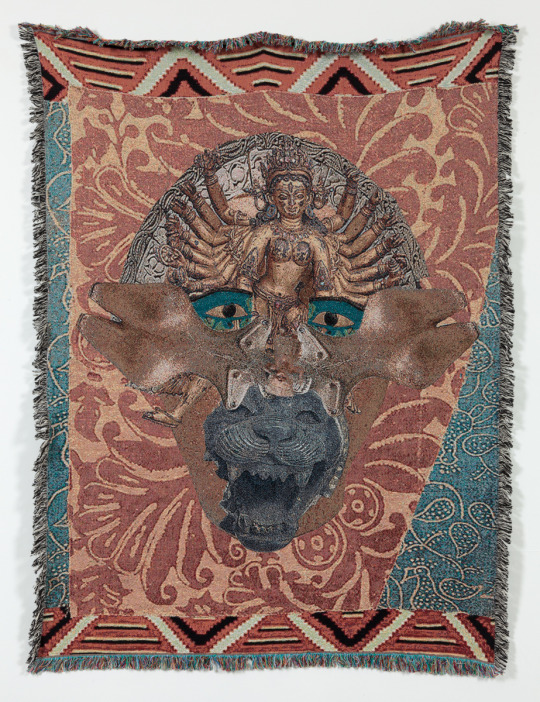

Natalia Nakazawa, Obtrait I, Jacquard woven textile, 71 x 53 inches, 2015, Photo credit: Jeanette May

Natalia Nakazawa:

First off, Naz, how are you doing? There has been so much going on - it is far too easy to forget we have bodies. We have families, we have things we need to do, and we need to take care of ourselves. As they say, put the oxygen mask on first, and then help others. Can you maybe start by just telling us what your day looks like? What are you doing to take care of yourself?

Nazanin Noroozi:

I’m doing ok. I have to balance my day job and my studio time. My day job is working in high-end interior design firms in which our clients spend millions and millions of $$$ on luxury goods. It is very interesting to look at the wage gap especially considering the pandemic. When someone can spend 40k on a coffee table for their vacation house, and you hear all the issues with the stimulus checks etc, it makes you wonder about our value system and how our society functions.

As for self-care, I guess just like any other artist, I buy tons of art supplies that I may or may not need! I just bought a heavy-duty industrial paper cutter that can cut a really thick stack of paper! I needed it! I really don't have room for it, but I bought it! So that is my method of self-care! Treat myself to things that I like but may be problematic in the future. ;)

Natalia:

I recently re-watched Stephanie Syjuco’s Art21 feature online where she talks about having to actively decide to become a citizen of the US, despite having come to this country at the age of 3. One of the poignant points she brings up is how we are all reckoning right now with what it means to be “American”. She also brings up the iconic photo taken by Dorothea Lange of a large sign reading “I am an American” put up by a Japanese American in Oakland right after the declaration of internment - thinking about how citizenship can be given or taken away. This all feels very relevant right now. What do you think about these questions? How do you use archives and photos of our past to engage in these issues of belonging, citizenship, and the precarity of it all?

Nazanin:

What I try to do with archives is to question them as modes of cultural transmission and historical memory. I think many artists deal with archives in a more clinical and objective manner, whereas I like to add my own agency to these found photographs. When one looks at a family album or found footage, one is already looking at fragmented narratives. You never know a whole story when you look at your friend’s old family albums. I truly embrace this fragmented, broken narrative and try to make it my own. I also constantly move back and forth between still and moving images, printmaking and painting, experimental films and artist books. So there is this hybridity in the nature of found footage itself that I try to activate in my work. In these works handmade cinema is used as a medium to re-create an already broken narrative told by others, sometimes complete strangers to tell stories about trauma and displacement. That is what fascinates me about archives. The fact that you can recreate your story and make a new fictional alt-reality.

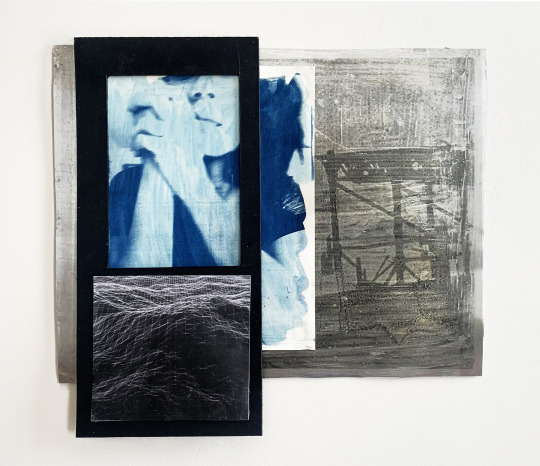

Nazanin Noroozi, Self Portrait

Natalia:

But who is to say these if fictional alt-realities are less important or less serious than purely “art historical” narratives? One of the things that I am exploring in my work is giving space for slippages in memory, rearranging of timelines to accommodate a lived experience. What happens when we look at collections - even museum collections - with the same warmth, tenderness, and care that we would an old friend? What possibilities are dislodged there? What benefit is there to towing the status quo - which is built on white supremacy, stolen artifacts, and other types of lying, exclusion and dubious authoritative storytelling? Also, there are so many family histories that often become reified - being told and retold with certainty over and over again. How do we claim agency from that oppressive knowledge? The things we tell ourselves about our families may not be “true” so what do we risk by revisiting our archives and re-telling those histories through our current eyes? When we re-examine the history - we may discover new ways of seeing and being with ourselves.

Nazanin:

I like to think of photographs as sites of refuge. When you look at a photograph of a kid’s birthday from many years ago, you know for fact that this joyous moment is long gone. These mundane moments that bring you “happiness” and security won't last. It’s like “all that is solid melts into air”. In a larger picture, isn't everything in life fragile and fleeting and there is absolutely no certainty in life? For example, look at how Covid has changed our “normal everyday” life. A simple birthday party for your kid was unimaginable for months. In “Purl” and “Elite 1984” I mix these mundane moments with images of flood, natural disasters and other forces of nature to talk about fragile states of being and ideas of home. I digitally and manually manipulate footages of a stormy Caspain Sea, Mount Damavand or a glacier melt to ask my questions about failure or resistance, you know? I let the images tell me the new narrative, both visually and thematically.

Something I find really interesting in your work is how you re-create these alt-realities by actively and physically engaging your audience into participating in your work, like your textile maps - called Our Stories of Migration? Do you have any fear that they may tell a story you don't like? Or take your work to a place that you didn't anticipate? How do you deal with an open-ended artwork that is finished but it needs an audience to be complete?

Natalia Nakazawa, Our Stories of Migration, Jaquard woven textiles, hand embroidery, shisha mirrors, beetle wings, beads, yarn, 36 x 16 feet, 2020, Photo credit: Vanessa Albury

Natalia:

I am always stunned by the generosity of the people I meet - those who dive in and share their own histories - and I think it points to a universal need of ours to share and connect. There is always potential to create intimacy - even within the walls of large institutions, such as schools or museums - when our own lives are placed at the center with care and concern. I’ve never heard a story that didn’t make me pause and grant me more space for contemplating the complexity of being a human on this planet. We have all kinds of mechanisms for memory - archives, written diaries, photos, paintings, objects - but at the end of the day they are nothing without our active participation. Quite literally they are meaningless unless they are being interacted with. That has been the entry point for me, as an artist and educator. How do we take all of these things that exist in the material world and make sense out of them? What does the process of “making sense” do to the way we live TODAY? Or, perhaps, how we envision the future? It is almost like a yoga practice, a stretching of the mind, a flexibility to think backwards and forwards - that lends us more space to consider the present.

Nazanin:

Yeah! I think you really are on point here! I think we really can't understand our existence without retelling the history and recreating new realities.

Nazanin Noroozi, The Rip Tide

Natalia:

Thank you, Nazanin! Anything coming up for you that you want to mention?

Nazanin:

Yes, I am actually doing a really amazing residency at Westbeth for a year. This is an incredible opportunity as I get to live in the Village for one year and have a live-work space in such an amazing place. Westbeth is home to many wonderful artists!

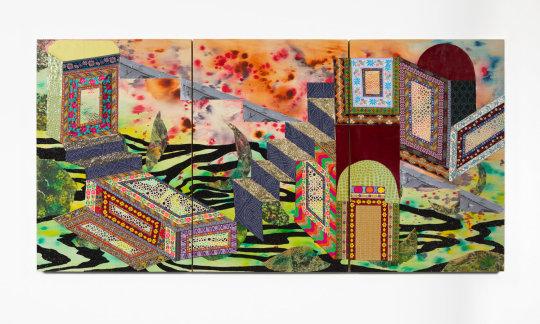

Natalia Nakazawa, History has failed us...but no matter, Jacquard textiles, laser cut Arches watercolor paper, vinyl, jewels, concentrated watercolor and acrylic on wood panel, 40 x 90 inches, 2019, Photo credit: Jeanette May

Natalia Nakazawa is a Queens-based interdisciplinary artist working across the mediums of painting, textiles, and social practice. Utilizing strategies drawn from a range of experiences in the fields of education, arts administration, and community activism, Natalia negotiates spaces between institutions and individuals, often inviting participation and collective imagining. Natalia received her MFA in studio practice from California College of the Arts, a MSEd from Queens College, and a BFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design. She has recently presented work at the Arlington Arts Center (Washington, DC), Transmitter Gallery (Brooklyn, NY), Wassaic Project (Wassaic, NY), Museum of Arts and Design (New York, NY), and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY). Natalia was an artist in residence at MASS MoCA, SPACE on Ryder Farm, The Children’s Museum of Manhattan, Wassaic Project, and Triangle Arts.

www.natalianakazawa.com

@nakazawastudio

Nazanin Noroozi is a multimedia artist incorporating moving images, printmaking and alternative photography processes to reflect on notions of collective memory, displacement and fragility. Noroozi’s work has been widely exhibited in both Iran and the United States, including the Immigrant Artist Biennial, Noyes Museum of Art, NY Live Arts, Prizm Art Fair, and Columbia University. She is the recipient of awards and fellowships from the Artistic Freedom Initiative, Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, NYFA IAP 2018, Mass MoCA Residency, North Adams, MA and Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts Residency, NY. She is an editor at large of Kaarnamaa, a Journal of Art History and Criticism. Noroozi completed her MFA in painting and drawing from Pratt Institute. Her works have been featured in various publications and media including BBC News Persian, Elephant Magazine, Financial Times, and Brooklyn Rail.

www.nazaninnoroozi.net

@nazaninnoroozi

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

cheat sheet for college/university AUs

because academia is the least transparent place in the world, i made a quick reference guide for academic ranks/positions in the united states. this is totally not a big deal at all, but for your reference if you ever need/want it:

undergraduate: students in their first four years of college education

graduate: students who typically have their bachelor’s/4-year degree and are moving on to more specialized education. Note: It’s weird/special if someone younger than 21-22 is in Master’s programs. weird/special if someone is younger than 23-24 for PhDs. some degrees:

Master of Arts/Master of Science. same as bachelor’s but more specialized and shorter. Usually 2-3 years to complete. typically requires a thesis

Master of Fine Arts (MFA). specialist degree for someone in the arts--usually works more like a residency program and has less teaching obligations. 1-3 years typically. separate degree from a Master’s (most creative fields value MFAs over MAs fwiw)

Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD). After Master’s, but sometimes there’s joint programs. typically 4-7 years to complete. in STEM, it usually goes faster than in humanities or social sciences. typically requires a dissertation

then we got postdocs and non-tenure track positions. postdocs are fixed-term positions, either teaching or in research, that are done after completing a PhD. average is 1-3 years. non-tenure track, sometimes called “contingent” positions, are basically what it says on the tin--academic positions that don’t work toward tenure. adjuncts fit under this umbrella.

then as a graduate student, there’s a couple ways students work for funding:

TA or teaching assistant. works directly underneath a professor to assist in things like grading, office hours, running lab or discussion sections, etc. usually in large or lecture classrooms

graduate instructor. runs their own class without a professor directly supervising

research assistant. works out of a lab, with a professor for a specialized project, or wherever the department wants to throw them :’D

now professors, have different ranks and this is what i see incorrectly labelled for the most part in fic (understandable lol i had no idea what any of it meant until my 2nd year of grad school):

assistant professor. your brand new professor! anything under mid-twenties is weird/special for this rank. they don’t have tenure yet, and are typically in this position for 5-6 years before they go up for tenure.tenure can be denied, and many assistant professors peace out of programs at that point if you want Drama. typically these people are very very stressed out lol

associate professor. mid-career! they’ve achieved tenure and job security. it’s weird/special for someone under 30 to have this position. some people stay at this rank for the rest of their career. or, after 5-6 years they might apply for

full professor. tenured, “senior academics.” they’re probably Names in the field or have been at the university for a long time. majority are old, white dudes :/ beaucoup pay, as far as what that means for academics. at least mid to late 30s.

professor emeritus. retired professors that might still pop in every once in awhile to teach a class, guest lecture, or serve on thesis or dissertation committees

there’s also honorary doctorates which means the person in question didn’t do the degree, but are honored for contributions to the field/industry at large by a university. darkside academia: usually it’s a recruitment strategy

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

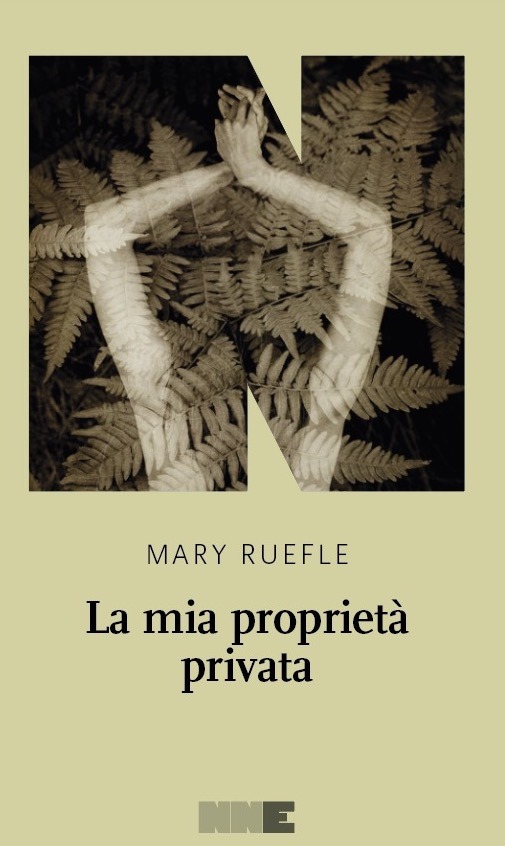

Nota del traduttore

Translator’s note

English below

Ho ricevuto in regalo tutto i libri di Mary Ruefle dal suo editor, più o meno tre anni fa. È stato amore a prima vista. Una montagna di libri vicini vicini in borsa, poesia e prosa. Non un amore canonico, passionale, no, ma una cosa fatta di strane affinità elettive e un costante senso di smarrimento che non trovavo sgradevole, forse perché mi piace perdermi.

La scrittura di Ruefle può provocare uno strano timore reverenziale – il misto di paura e fascino che forse proverei davanti a un marziano – però a volte ti fa scoppiare a ridere. O almeno a me capita spesso. E soprattutto ti fa perdere l’orientamento. A un certo punto non capisci più dove sei e segui solo le immagini come i sassolini e le briciole di Hansel e Gretel. È affascinante se leggi e basta, un po’ una fregatura se devi tradurre.

Le poesie me le ero lette in un sorso appena avevo avuto i libri in mano. La sensazione di perdersi c'era, ma in quella forma me l'aspettavo, e mi dava chiavi di ritmo ma non soluzioni sensate per tradurre.

Ho deciso quindi di lavorare su pezzi a caso, uno sui colori e uno con una struttura più convenzionale – se mai Ruefle si può definire convenzionale – per capire cosa poteva farmi da sassolino oltre alle immagini. Perché io le immagini le vedevo bene, e le sentivo, ma dovevo stare nella griglia della scrittura, che non è mai colloquiale, ma sempre precisa e algida e severa nella forma - d’altronde in America la sua prosa è venduta nel settore poesia, oltre a essere insegnata in tantissimi master di scrittura creativa - ma poi in parecchi punti fa ridere o rimanere a bocca aperta. Tipo, quando scrive di menopausa, ‘Quando impazzisci non hai la minima propensione a leggere quello che Foucault ha scritto a proposito di cultura e pazzia’. Oppure “Una cosa è certa: non vorrei essere un albero di Natale.” O quando parla di teste rimpicciolite chiedendosi, sinceramente stupita, come mai la gente non ci pensa spesso.

Dopo la prima stesura di qualche frammento non ero soddisfatta. Allora mi sono messa a guardare i video di lei su YouTube. Dice cose serissime con un’espressione impassibile – la classica deadpan, letteralmente faccia morta – ma anche furba e allerta, sembra una volpe, e poi qua e là inserisce delle battute rimanendo seria seria, magari con l’aggiunta di un piccolo sorriso. A un certo punto durante una conferenza dice: ‘Gli artisti sono solo persone che non hanno dimenticato come si disegna, e per disegnare intendo creare. Ma non fatevi ingannare, hanno dimenticato moltissime altre cose. A volte si dimenticano che non hanno più otto anni. Ecco perché gli artisti sono per natura molesti.” E poi in un’altra conferenza dice che bisogna tornare bambini per ritrovare quel tipo di immaginazione, e che il buon senso e la razionalità non vanno molto d’accordo. “L’immaginazione ha vita propria e autonoma, l’immaginazione non è una cosa con cui giochi, è l’immaginazione che gioca con te. Ha il potere di creare e distruggere, di formare e deformare.”

Poi ho guardato alcuni dei suoi lavori di cancellatura, le erasures, perché Ruefle è anche un'artista di talento. E mi è venuto in mente che era tutto un lavoro per sopprimere la comprensione e creare qualcosa di nuovo a partire dalle parole pure.

E così finalmente ho capito, come in una sorta di epifania, che dovevo sospendere la logica. Esattamente come nella poesia. Anche perché non potevo farle cento domande su cinquanta pagine (via lettera poi, perché non ha il computer, scrive tutto a macchina). Nella sezione Contact del suo sito si legge: “Sorpresa! Non posseggo un computer. L'unico modo per contattarmi è scrivere alla mia casa editrice, Wave Press, oppure incontrare per strada qualcuno che conosco di persona.” Quando ho visto quella frase sul suo sito, praticamente dopo aver letto tre poesie, mi è venuta in mente la parola sassy, simpatica sfacciata e poi ho pensato, è matta. E poi ho pensato, non vedo l'ora di conoscerla.

Comunque a quel punto non so bene cosa sia successo, quando ho abbandonato la comprensione per il dubbio, ed è stato un po’ come entrare in uno stato di trance e lasciarsi guidare – forse anche commettendo errori ignobili, ma era il rischio da correre. Un po’ come succede con gli allucinogeni. E in effetti ho capito che leggere e tradurre la prosa-poesia di Ruefle è un'esperienza sinestesica, in cui senti colori e annusi parole e tocchi suoni.

Ovviamente gliel'ho scritto. Cioè in pratica mi sono immaginata un sacco di soluzioni di cose non solo difficili da tradurre (tipo giochi di parole di cui ho cambiato proprio il testo) ma a volte del tutto incomprensibili senza chiederle il permesso, senza la certezza che fossero giuste, come buttarsi in mare e nuotare di notte. E alla seconda lettera (gentilmente stampata e spedita con francobollo dal suo editor e poi via mail la risposta fotografata se no ci mettevamo due anni tra poste italiane e greche), quando le ho chiesto il significato di una parola contenuta in un brano già di per sé a dir poco astratto, ashling (che i vocabolari danno come sogno o visione in una rara accezione irlandese) lei mi ha risposto: 'Oddio pensavo a ash, a cenere ma non ricordo dove ho trovato quella parola, o se l'ho inventata, ma che bello questo significato irlandese del sogno che hai scovato! Comunque usa l'immaginazione e inventati qualcosa che dia l'idea di sogno, oppure di cenere ma anche di albero, e fai che sembri piccolo, minuscolo... Magari tipo ashtray??'

Per un altro brano intero dove c'era un gioco di parole praticamente intraducibile mi ha scritto: “Oh sì che guaio. Vuoi che lo riscrivo? Anzi, riscrivilo tu! Cambia anche il titolo!”

In fondo a una delle lettere ha scritto: “Bellissima questa cosa che le lettere ci mettono settimane ad arrivare fino a te. Non ho mai messo piede su un'isola greca. È solida o spugnosa?” Eh. Bella domanda. Però mi ha fatto capire che dovevo vedere l'isola – e il mio modo di tradurre lei – toccandola con i piedi, annusandola con le mani, immaginando tutto con i sensi ribaltati.

Dopo varie riscritture, ho fatto un po' di prove di lettura con alcuni amici, chiedendo di chiudere gli occhi e ascoltare senza sforzarsi di capire e mi hanno detto che funzionava, che cadevano in quello stato di trance e vedevano le immagini. Ho amici adorabili ma non compiacenti, quindi forse non finirò nell'inferno dei traduttori. E se anche fosse, probabilmente sarebbe una storia in stile Ruefle.

xxxxxx

I received all of Mary Ruefle's books from her editor at Wave about three years ago, and it was love at first sight. A mountain of beautiful books sitting close together in my bag, poetry and prose. It was not a canonical, passionate love, no, more like a feeling of deep closeness made of elective affinities and a constant, but not unpleasant – maybe because I like getting lost - sensation of being confused and out of my depth. A complex kind of love. Ruefle's writing can be a source of strange awe - the mix of fear and fascination that perhaps I'd feel in front of a Martian - and make you lose your bearings. At some point you don't understand anything anymore and just follow images, like Hansel and Gretel's pebbles and crumbs. It's fascinating if you just read it, but it's a bit of a bummer if you have to translate it.

I had read all of her poetry as soon as I had the books in my hand. The feeling of being lost was definitely the same, but perhaps I kind of expected it in that form. The poems gave me keys to the rhythm, but not reasonable enough solutions.

So I decided to translate some fragments at random, one about colors and one with a more conventional structure - if ever Ruefle's writing can be called conventional - to understand what else, besides images, could be my pebbles. Because I did see the images quite vividly, and I felt them, but I had to keep playing within the writing grid, which is never colloquial but always precise and aloof in its form – after all in the US her prose is sold in the poetry section, and it's being taught in many creative writing MFA - but it is often very funny. Like, talking about menopause, "When you go crazy, you don’t have the slightest inclination to read anything Foucault ever wrote about culture and madness”.

Or "One thing is certain: I wouldn't want to be a Christmas tree." Or when she talks about shrunken heads wondering with genuine surprise why people don't think about them very often.

After the first draft I was not at all satisfied. So I started watching her videos on YouTube. She says very serious things with an impassive expression - the classic deadpan, an expression that I always liked - but also crafty and mischievous at times. Then here and there she just comes out with a joke while remaining very serious, maybe with a tiny smile. In one lecture she says: "Artists are just people who have not forgotten how to draw, by which I mean create. But don’t be taken in; they have forgotten a great many other things. Sometimes they forget they are no longer eight years old. This is why artists are of a troublesome nature.” And then in another conference she says that we need to become children again to rediscover that kind of imagination, and that common sense and rationality do not go very well with it. "The imagination has its own independent life, the imagination is not something you play with, it is the imagination that plays with you. It has the power to create and destroy, to form and deform. " Then I looked at some of her erasures, because Ruefle is also a talented artist. And it occurred to me that it was a way to suppress understanding and create something new from pure words. So I finally realized, like an epiphany, that I had to suspend logic. Exactly like with poetry. Also because I couldn't ask her 100 questions in 50 pages (and send them by letter, because she doesn't have a computer, she works only with her typewriter). In the Contact section of her website, she writes: "Surprise! I do not actually own a computer.

The only way to contact me is by contacting my press, Wave Books, or by running into someone I know personally on the street." When I checked her website, immediately after reading three poems, I heard the word sassy in my mind, and I thought, She is crazy. I can't wait to meet her, she must be adorable. I don't really know what happened next when I gave up understanding, and it was a bit like entering into a trance state and letting myself be guided - perhaps even making ignoble mistakes, but that was the risk I had to run. A bit like what happens with hallucinogens. And in fact, I realized that reading and translating Ruefle's prose-poetry is a synaesthetic experience, in which you hear colours and smell words and touch sounds. Obviously, I tried – tried – to explain all this to her. In other words, I came up with a lot of solutions for things that were not only difficult to translate (such as puns I had to change the whole text for) but sometimes completely incomprehensible, and this without asking permission, without the certainty that they were right, like jumping in the sea and have a swim at night. And at the second letter (kindly printed, stamped and sent by her wonderful editor who also scanned and sent me her answer otherwise it would have taken years – Greece is paradise, but speed is not its forte), when I asked her the meaning of a word contained in a piece which is already abstract, to say the least, ashling (according to one of the many dictionaries I consulted it is a dream or a vision in a rare Irish meaning) she answered: 'Oh 'God I was thinking of ash, but I don't remember where I found that word, or if I invented it, but how beautiful this Irish meaning of the dream you found! Anyway use your imagination and come up with something that gives the idea of a dream, or ash but also a tree, and make it look small, tiny...? Maybe like an ashtray??' For another whole piece where there was a pun that was practically untranslatable, and she wrote, "Oh yes, that's a problem. Do you want me to rewrite it? In fact, you should rewrite it! Change the title too!" At the bottom of one of the letters, she wrote, "Isn't it beautiful this thing that letters take weeks to get to you. I've never set foot on a Greek island. Is it solid or spongy?" Ha. Good question. It made me realize, though, that I needed to see the island - and my way of translating her - touching it with my feet, smelling it with my hands, imagining everything with my senses turned upside down. After

several rewritings, I did some tests with friends, asking them to close their eyes and listen without trying to understand. They told me it worked, they could see the images and get into a kind of trance too. I have lovely friends and I know for sure that they are not complacent, so maybe I won't end up in translators' hell. And if that were the case, it would probably be a Ruefle style story.

1 note

·

View note

Text

for fanfic authors considering a creative writing graduate degree

i’ve had a few people PM me about the grad program i’m in, and i thought maybe i would share some information i’ve learned about creative writing graduate degrees plus all the stuff i wish someone had told me before i started applying.

to give you some context: i own a house (that i purchased, i didn’t inherit) and i support myself completely. i’m not married or in a relationship and i don’t have kids yet. my undergraduate degree is in psychology. i came from a lower-class upbringing. i had never written an original work of fiction before applying; i had only written fanfic. i worked in finance for ten years at a dead-end job before i decided to go back to school. i applied to six schools and got accepted into one.

basic info

usually a creative writing graduate degree is called an MFA, or a Master of Fine Arts. it’s considered a terminal degree, that is to say, it’s the highest degree you can attain in the field of creative writing.

however, some programs are also MAs, and usually those are combined with literature or pedagogy. there are also a number of creative writing PhDs, which are less about the craft of writing and more about teaching and research.

MAs are generally two years, MFAs are anywhere from two to three years, and PhDs are around four. most schools offer the MFA, so going forward that’s the type of degree i’ll be discussing. the MA doesn’t stray far from the MFA, and the PhD is a whole other beast.

you’ll need to choose a focus for your degree. most MFAs offer fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. some offer scriptwriting or experimental/hybrid forms. some expect you to play around with multiple genres.

MFA classwork revolves around the creative writing workshop. a workshop is a class where you meet with your peers once a week to discuss the work you’ve read the prior week. you take turns submitting a story, poem, or excerpt, and while you’re the one being workshopped, you take notes while everyone talks. when you workshop your peers, you offer a letter of critique and participate in the discussion. workshop is also the place where you can ask about craft, publishing, or anything else you have questions about. workshops are run by a leader, usually a professor, someone who has a significant publishing history and experience teaching.

other classwork for MFAs include literature seminars, where you read already published work and discuss it with your peers while applying it to established theory.

an MFA thesis is generally a book-length work of your given genre, due at the end of your studies to grant your degree. it may also include some research component, like a craft essay or reading list, and an oral examination. you work with an advising committee throughout your degree to hone and revise your thesis, and generally use workshop to get peer feedback on early drafts.

MFA extracurriculars include working on your school’s literary magazine, doing readings of your work, and participating in your English department’s student organizations. there are usually additional opportunities that pop up throughout each semester, including meeting with established visiting writers (and hopefully these are writers of the super famous variety, which makes for great networking).

applying to an MFA involves a writing sample (the most important piece of the application), undergraduate transcripts, letters of recommendation, and a letter of intent. some also require the GRE. many have a $50-100 fee, but sometimes you can request a waiver.

assumptions debunked

here are some misconceptions i’ve come across and some i had when i began researching.

expectation: i can’t afford it

reality: that’s possible, but consider that many programs are fully funded, that is to say, the school will pay you to go there. no tuition, no loans, just a stipend that you’ll receive in monthly disbursements. it’s not a lot, but usually enough to get by.

the way it works is that in exchange for grad classes, you teach undergraduate english. this is usually a class called english composition, and many schools make it mandatory for all incoming freshman, which is how the english department gets funded, and they can return those funds to you, the grad student.

personally, teaching has become one of my favorite things i’ve ever done. i want to continue teaching when i graduate because it’s just really fun and incredibly rewarding. i highly recommend this route for an MFA because you won’t end up in debt afterward and you’ll gain a marketable skill (pedagogy) if your writing career doesn’t take off immediately.

expectation: i can’t quit my job

reality: there are a growing number of what are called low-residency MFAs. the above fully funded scenario are programs called full-residency, where you have to be on campus a few days a week, but low-res programs are mostly online, with 1-2 weeks per year spent on campus.

the downside to this is that there is usually minimal funding for these programs, which means you’re paying for them out of pocket or with loans. the people who go into low-res programs are usually people firmly established in their lives with some disposable income and a desire to improve their work. this is a great option if you’re currently working full time and can’t move to be near a fully funded program.

expectation: but my undergrad degree isn’t in english or CW

reality: GOOD. that’s what’s so great about writing as an academic discipline -- when we get nothing but formally trained writers, we get too many stories about the formally trained life.

your background, your work history, and your life experiences are all enormously valuable to a writing program. the weirder and more diverse you are, the more intrigued admissions people will be. they want people who can bring new perspectives to workshop, who see the world in different ways than those who have been trapped in academia for ages.

it’s definitely valuable to have an english undergrad degree, but it’s equally valuable to have life experience.

expectation: i’m just a fanfic writer

reality: GOOD. do you know how amazing fanfic is? of course you do, you write it. now imagine the sense of community and purpose and drive you have while writing fanfic, and put that in a physical place, and you basically have grad school. so if you like fanfic for all those things -- community, purpose, drive -- you’re going to love getting an MFA.

from a skill perspective, fanfic authors have something major that non-established ofic writers are missing: an audience. if you write fanfic to post on tumblr or ao3, you’re writing it with a specific audience in mind. you are probably acutely aware of how that audience will react, how to entertain them, and most importantly, HOW TO DEVELOP CHARACTERS.

i really thought i would get into an MFA and turn into some kind of holier-than-thou snob about fanfic, like suddenly my eyes would open and i would gain such an appreciation for, idk, Hemingway or some shit that i would completely forget about my fanfic roots.

N O P E. i’ve found a lot of published authors i like, sure, but i like them because their writing reminds me of my favorite things about fanfic. you will not have to sacrifice your love of fanfiction* to pursue an MFA, and you won’t have to change the things you love writing. people may think what you write is weird, but fuck ‘em. write what you want to write.

*you won’t be able to write actual fanfic in grad school, but there’s nothing stopping you from filing off the serial numbers. if str8 white men can do it over the entire span of civilization, so can you.

expectation: i don’t need an MFA to be a writer

reality: god, so true. if you write fanfic, you probably already have all the skill necessary to begin the publishing game if you want to go that route, and potentially all the feedback you need to keep improving. which begs the question, why would you even want an MFA?

i can only tell you why i applied:

i had reached a ceiling in my writing and wanted to explore and experiment with things i knew would never fly in the land of fanfic

i wanted to belong in a physical community of people who took creative writing as seriously as i did

i wanted ofic reading recommendations and a structured environment in which to work

i wanted to teach!!

i wanted to learn about and discuss literature at a level that is difficult to find outside of academia

i didn’t feel like my education was complete, and while i could have gone back to school for psychology, my qualifications more closely aligned with creative writing programs and honestly, it just sounded way more fun

i wanted access to databases beyond jstor

i had a lot of perspectives and opinions i wanted to learn to voice more articulately and in an artistic or research-based form

i was tired of my job and looking for a different career path

you might have different needs, or maybe some of these resonate with you. people get MFAs for all sorts of reasons. plus, your perceptions might change when you get there; mine definitely did.

expectation: i only write genre fiction, not “literature”

reality: you can write whatever the hell you want for whatever reason you want. you’re going to get feedback regardless, and your peers are going to care about the things you care about, and if they’re worth a damn, they’ll give you crit on their perception of your priorities, not what they think is important to the field of literature.

in the past year, i’ve read workshop submissions ranging from the onion style satire, to children’s literature, to hard sci fi. the point of an MFA is that you’re there to explore the work that interests you. you don’t have to conform for anyone for any reason. you are there to do your work, and the program is there to guide you and offer you support.

expectation: i’m not qualified because don’t have any publications

reality: you don’t need to be published to apply for an MFA. most people aren’t even published by the time they graduate. what you do need is evidence of your commitment to writing and the discipline thereof, that is to say, you write consistently, you’re passionate about writing, and that your writing sample shows both a command of writing as well as promise of improvement.

expectation: i don’t have what it takes to pursue a graduate degree

reality: i promise you do. the reason i’m writing this is because the fanfic community has some of the most humble individuals i’ve ever met, who are compulsively shy about their craft, and who have no concept how good they actually are. i see so much self-defeated mentality, so much impostor syndrome. but please believe me when i say

LITERATURE NEEDS YOU

literature needs the way you see humanity, your compassion, your interest in telling stories without want of profit, your eye for character, your drive, your commitment, your voice.

you are so much better than most of what’s out there. you may not see it now but it’s true.

expectation: i won’t be able to get a job with an MFA

reality: ehhhh kinda true, but if that’s the only thing stopping you, ignore it. a (full-res) MFA trains you for three things: writing, editing, and teaching. all of these are lucrative careers that are no more difficult to establish yourself in than most other fields. the graduate chemist has the same concerns about the job market as the graduate writer. it’s all gatekeeping rhetoric steeped in a terrible economy. you just have to trust you’ll be ok.

expectation: i don’t know what i would write about

reality: you can figure it out when you get there. no one else knows what they’re doing either.

i’m happy to answer more questions if you have them! i hope this helps some of you who are curious about how MFAs work. i’m sharing this because i never thought i would be able to do a graduate degree, and now that i’m here, even though it was a huge risk, it’s the best decision i’ve ever made.

[writing advice tag]

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

Osama Bin Dramaturgy: Knaive Theatre @ Edfringe 2017

Explosive Osama Bin Laden Show Returns To Edinburgh Fresh From US Tour

“Tonight, ladies and gentlemen,

I am going to show you how to change the world”

BIN LADEN: THE ONE MAN SHOW returns to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival from 2nd-28th August at C (Venue 34).

The world’s most notorious terrorist tells his story in BIN LADEN: THE ONE MAN SHOW a remarkable, provocative and multi-award-winning production from Knaïve Theatre.

The twist? Bin Laden is 28 years old, White British and charming as cream teas in summer. After a critically acclaimed and highly successful American Tour, this ‘must-see’ production returns to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, where it originally premiered, from 2nd-28th August before beginning a UK tour that includes The Royal Exchange Theatre, The Sherman and The New Wolsey.

What was the inspiration for this performance?

We don’t want to give away too much of the show, but what we can say is that we believe that the best theatre tries to understand the world, and even the most terrible actions within it. A quest for understanding was the starting point for this show.

Is performance still a good space for the public discussion of ideas?

We hope so! In our experience audiences are becoming more and more eager to see work that provokes them to discussion. Theatrical performance can – like very little else - combine the messy and personal with the universal and academic, the imaginative with the factual; and immerse you in a dialectic world of ideas, images and stories and confront you with things you might have never wanted to consider before. That, to us, provides very fertile ground for the public discussion of ideas – particularly ideas we might rather not discuss.

How did you become interested in making performance?

We were both engaged with performance making from a frighteningly young age. At age 3 Sam (the actor) spent whole days as his female alter-ego, Madam (complete with pearl necklaces and red leather handbags). He would also put on strange musical comedies with his two older brothers for their parents’ “benefit” which mostly involved Sam flinging himself about the living room trying to catch an imaginary cow and milk it.

Tyrrell (the director) spent his early years refusing to wear anything but his Thunderbird Two costume and spent his university days (while apparently studying politics) refusing to do anything but theatre. We met in 2012 working for the Barbican Theatre in Plymouth and began making theatre together in 2013 with this show!

Is there any particular approach to the making of the show?

This show came about through heartbreak, particularly awful accommodation in London and a lot of rum – a long story we will happily tell when asked! It was made through 3 months of intensive research, reading and watching everything we could lay our hands on related to Bin Laden.

Then we locked ourselves away in various parts of the world (to stave off insanity) and experimented with the source material, wrote, improvised, invited some people to impart some thoughts with us and eventually we had something looking like a show and opened it – terrified – at the Buxton Fringe. Since then we have rewritten, developed and taken further risks every time we have taken the show out. So not a particular approach, more a desire to provoke the most exciting debate we can with the extraordinary story of this man.

Does the show fit with your usual productions?

We haven’t yet tied ourselves to an approach as a theatre company. We try to let the form be governed by how best to communicate the content of the piece. We have, since Bin Laden made immersive games-based theatre (Power To The North), a Dance-Theatre adaptations of Baal with Impermanence Dance Theatre, Public Understanding of Science Theatre (Pain, The Brain & A Little Bit of Magic) and we are currently working on an adaptation of 1936 apocalyptic Sci-Fi novel, War With The Newts, with writer Tim Foley.

Although in form our work is broad, we have a very focussed intention which unifies all of the work we have created so far: to create dangerous theatre which engages and empowers audiences into vibrant discussions around the political dialectics of our time.

What do you hope that the audience will experience?

The audience will experience, not just watch, an incredible story and a world-changing journey. We hope they will experience, as we have done, something that will change the way they view the world, perhaps in some small but very real way.

We hope they will experience something they never expected. But mostly, we hope they experience an unforgettable evening that lasts far longer than the Edinburgh hour; long into the night with fellow audience members, and long into their lives as they share their experience with others.

What strategies did you consider towards shaping this audience experience?

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Times; color: #2d2d2d} p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 9.5px Arial; color: #ff2600} p.p3 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Times; color: #2d2d2d; min-height: 14.0px}

Let’s just say that we did a lot of research into American self-help culture…but what that means, you’ll have to come see to find out. The audience experience is still evolving, in front of our very eyes. The more we have performed the show (the 28th August is our 100th performance) the more we have realised that the audience experience is key to the success of the show.

So we have crafted and honed that experience over 4 years, and it is still growing. Every time we tour the show we challenge our assumptions about the last time and challenge ourselves to see if we can go further.

With populist rhetoric playing an ever-increasing role in Western politics, Knaïve Theatre’s Tyrrell Jones and Sam Redway pry apart what it is that draws us to follow demagogues, asking if the world’s most wanted terrorist might have been more persuasive than we ever imagined. They ask audiences to re-examine their own information and prejudices from a naïve perspective, just as the company have.

The award-winning hit of the fringes in San Diego and Hollywood, Bin Laden returned home to perform a sell-out show at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester. Knaïve Theatre are now Supported Artists at the Exchange and have redeveloped the show with the help of the theatre’s creative team ready for a return to Edinburgh before the company’s first national tour.

Having provoked important and timely debate surrounding Middle East conflict and the War On Terror internationally, they will now bring that discussion to a national audience. Though they expected this story would become less relevant, current global tensions and recent events have galvanised an ever-increasing appetite for the debate they inspire.

Bin Laden was made in 2013 on a shoestring by Tyrrell Jones and Sam Redway. After previews in Buxton and London, it opened at Edinburgh and the show was awarded the first Broadway Bobby of 2013. It was in The List’s Top 5 Theatre Shows To See and received a host of first-rate reviews. Quickly, the show started selling out, and before long it was a hit. With the success of Edinburgh 2013 behind them, Tyrrell and Sam undertook formal training (Birkbeck MFA in Directing and RADA MA Theatre Lab respectively). They then redeveloped and toured the show, this time around USA with Arts Council AIDF funding.

AWARDS

Encore! Producer’s Award – Hollywood Fringe Festival 2016

Critic’s Pick Of The Fringe Award – Hollywood Fringe Festival 2016

Outstanding Actor in a Drama – San Diego International Fringe Festival 2016

Gold Award – Tvolution Los Angeles 2016

Broadway Bobby (Sixth Star) – Broadway Baby, Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2013

Top 5 Shows at the Fringe – The List, Edinburgh 2013

Venue: C, Adam House, Chambers Street, EH1 1HR, venue 34, Edinburgh Festival Fringe

Dates: 2-28 Aug (not 15)

Time: 18:30 (1h00)

Ticket prices: £9.50-£11.50 / concessions £7.50-£9.50 / under 18s £5.50-£7.50

C venues box office: http://ift.tt/2tQxW68017/bin-laden-the-one-man-show or 0845 260 1234

Fringe box office: www.edfringe.com or 0131 226 0000

Full Tour Dates:

2nd – 28th August – C Venues, Edinburgh Fringe Festival

5th- 7th September – Royal Exchange Theatre

21st September – Square Chapel, Halifax

28th September – New Wolsey, Ipswich

5th October – CAST, Doncaster

19th- 20th October – Sherman, Cardiff

24th- 28th October – Bike Shed, Exeter

3rd November – Litchfield Garrick

9th- 11th November – Mercury, Colchester

from the vileblog http://ift.tt/2veZJAt

1 note

·

View note

Text

quarter life crisis

I am a writer. I’m not super famous or super rich, but I am successful enough to live in an adorable bungalow surrounded by trees, hills, trails, and close to water. I spend a large amount of time in the outdoors – switching between trail running, swimming, and biking with my husband. For fun we sit in the backyard and drink hoppy beer or go hiking. Each morning I drink coffee and read in our hammock. We have two friendly and energetic docs – Pickle McParty the dachshund, and Markus the lab.

So, that was all a lie.

Life is a funny thing. You don’t realize it, but you live your life by the book and expect it to be rewarding. Then one day you wake up and have a quarter-life crisis.

I started getting recognition and awards as young as in the first grade. My teacher recognized I was engaged and kind to my classmates, as a first grader, and I got the Eagle Award – awarded to 2 people in each grade. My mother immediately went to my teacher and voiced her concern that this couldn’t possibly be for Kerry, the little girl she knows is whiney. But Mrs. Beehler set her straight – at least she was kind at school and an terror at home – what if it were reversed?

I continued into middle school and got academic awards and teacher awards. My best friend dated my long-time crush because I was too nervous to tell anyone about it because I was terrified of being kissed.

Some may say I peaked in high school. I was a three-sport athlete, and held a few leadership positions (why is “spirit chair” not a viable office role?), the summit of which was Associated Student Body President. I was voted homecoming princess, then queen. I dated a lovable Mormon for the majority of the time until he broke my heart, at which point I checked off the rebound boyfriend box.

Eventually I headed off to college where I played almost an entire season of water polo, balancing it with a full academic schedule until I decided it was time to be social. My then boyfriend, now husband asked me out on the beach. I earned good grades, wrote for the school paper, joined a sorority, studied aboard in Italy. I graduated on time and moved home to save money.

For my first job, my dad’s law firm hired me as a file clerk. I honed in on my organization skills, was promoted to legal assistant while someone went on maternity leave, then became a paralegal. After some time, I decided it was time to move into the infamous San Francisco with my best friend from high school as well as my best friend from college.

I landed a job at a staffing agency. It was my first taste of doing a job I don’t give a damn about. But it paid okay, and I could walk to work.

As soon as I figured out some of my normal friends had better jobs than I did, I was stunned. I had an amazing resume, how did this happen?! I started looking for a new job, interviewing for recruiting coordinator roles at every tech company imaginable. I knew I’d be great at it, but could not seem to get past the phone interview. Eventually my best friend’s brother hooked me up with the front desk coordinator role at the tech company he worked for, and I jumped at the chance. Somehow they paid me exactly what I was making at my horrible agency job.

Since starting at the front desk, I’ve been promoted to recruiting coordinator, recruiter, talent operations specialist, talent operations lead, and not sure where to go from here.

All of this to say, am I crazy to have followed this route? Or would I be crazy to toss it all aside?

When I think of this all at once, it is so easy to think of my career trajectory going in the direction of climbing the corporate ladder. No wonder so many people get sucked into it.

It is so hard to think of throwing that all away. But what if I look back one day and just kept falling into roles with more responsibility, that sure, I’ve earned and I’m good at. But what if I never stopped to try something my heart was telling me to do? Isn’t that so much scarier?

One huge factor here, is money. I grew up in a household where my dad had a substantial and steady income. On top of my mom’s job as a fitness instructor, she was a stay at home mom who did it all. When I graduated from college and was driving back from a football game with my mom, I asked her why she never went back to work after we all went to college and subsequently became furious with her answer. If she went back to work, it would basically all go towards taxes since my dad’s earnings put them into a higher tax bracket. I somehow had never really thought about how my life would be different from that, and after a year in an office, I couldn’t believe the trajectory I was on.

Growing up I must have had some deep-rooted, unconscious beliefs that working in the corporate world is easier, you can climb the ladder, make more money, and then eventually retire and enjoy the remainder of your life. Although I’m sure my dad is very passionate about being a lawyer, I never understood how he decided on that career and stuck with the same law firm. How were his dreams and aspirations so properly framed at his job? I’m sure he is very fulfilled with his career. And I know I could also climb the corporate ladder for the rest of my life and make a good amount of money.

But it feels kind of fake. Like I’m an impostor. These fools hired and promoted me? Don’t they know I should be in a different industry? Challenging myself in a way that is scary and makes me kind of uncomfortable until I’m good at it?

Let’s break that down. What scares me about not making money (as much, or as steady)? We won’t be able to purchase a home, we won’t be able to travel as often as we’d like, we won’t be able to retire.

I have these false beliefs about trying something new – writing, freelancing, opening a restaurant, or starting a business - anything outside of the corporate 9am-5pm job. I know myself. I’m a hard worker. For some reason I think I wouldn’t work as hard at another job, when I know that wouldn’t be the case.

Wouldn’t I rather live my unique, true life, than be concerned about retiring? For god’s sake, that’s 35+ years away! Who knows if retiring will still be a thing at that point!

Outside of my career, I think the next most important thing is getting a place of our own. Another place where I feel like an impostor. We can’t possibly afford and purchase a home, can we? I’ve mentioned moving so many times over the last year, but if it came down to it, I don’t know if we would, and the housing prices in the bay area are out of control. But I do want a place where we have our own space. I want to be able to grab my bike out of the garage and go on a long bike ride. I want to be able to have dogs, and to take them on a walk around the block or a jog. I want to have to get in the card to go grocery shopping! That sounds odd, but I think that would get me more excited about cooking and planning out meals. I think if we had our own place, I would spend more time outside. It is so easy to get myself stuck indoors at this point.

So here’s what is next. I’m going to work my way towards these totally achievable goals. I’m going to start writing (truly) to get better and faster at it. I’ll start by blogging and reading blogs on how to get started as a freelance writer (and start contributing and earning money this way). After a year or so of this, I will consider going back to school to get my MA or MFA in writing.

Simultaneously, my husband and I will take serious strides towards owning a home. We will talk to a financial advisor and our parents to see what type of loan we can get, what our budget is, and start looking at open houses. We have a great deal on our apartment now, but I’m ready to live in a stand-alone building with a backyard and a dog.

Just because it seems like a long shot doesn’t mean it has to be. I need to take charge, or I’m just living out someone else’s life. I will start living deliberately.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wombwell Rainbow Interviews

I am honoured and privileged that the following writers local, national and international have agreed to be interviewed by me. I gave the writers two options: an emailed list of questions or a more fluid interview via messenger.

The usual ground is covered about motivation, daily routines and work ethic, but some surprises too. Some of these poets you may know, others may be new to you. I hope you enjoy the experience as much as I do.

Austin Smith

grew up on a family dairy farm in northwestern Illinois. He received a BA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, an MA from the University of California-Davis, and an MFA from the University of Virginia. Most recently he was a Wallace Stegner Fellow in fiction at Stanford University, where he is currently a Jones Lecturer. He has published three poetry chapbooks: In the Silence of the Migrated Birds; Wheat and Distance; Instructions for How to Put an Old Horse Down; and one full-length collection, Almanac, which was chosen by Paul Muldoon for the Princeton Series of Contemporary Poets. His last collection, Flyover Country, was published by Princeton in Fall 2018. Austin’s poems have appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry Magazine, Yale Review, Sewanee Review, Ploughshares, New England Review, Poetry East, ZYZZYVA, Pleiades, Virginia Quarterly Review, Asheville Poetry Review, and Cortland Review, amongst others. His stories have appeared or will appear in Harper’s, Glimmer Train, Kenyon Review, EPOCH, Sewanee Review, Threepenny Review, Fiction and Narrative Magazine. He was the recipient of the 2015 Narrative Prize for his short story, “The Halverson Brothers,” and an NEA Fellowship in Prose for FY 2018. He is currently a Jones Lecturer at Stanford University, where he teaches courses in poetry, fiction, environmental literature and documentary journalism. He lives in Oakland.

http://www.austinrobertsmith.com/

The Interview

When and why did you begin to write poetry?

I started writing poems quite young because my father is a poet, along with being a dairy farmer. Some nights he would come in from the barn, clean up, and we’d go into town to hear him read poems at the local art museum. Glancing down the page, I see that this answer I’m giving can apply to the second question, as well, in that it was certainly my father who introduced me to poetry, not only through his readings, but through the collections on my parents’ shelves. From a young age I felt a particular pleasure in looking at a poem, even, I think, before really reading them. The shape of the poem on the page, the prevalence of white space, the way the lines broke on the right margin like surf. It appealed to me immediately. I still remember distinctly the first line I wrote: “The fire is burning hot.” I was kneeling in front of the fire (of course). Something had changed: I’d gone from hearing my father read poems to trying to make a poem myself. I must have been twelve or so. I still have the notebook, labelled “Poetrey” (sic), various marks in the corners of the pages, some lost order that I was already putting the poems in. As to why I began to write poetry, that’s more mysterious. Of course, I was following my father (my favorite poem on this score is Heaney’s “Digging”), but at the same time, I was striking out on my own, trying to speak of the same place and the same livelihood in a different way.

2. How aware were and are you of the dominating presence of older poets?

Again. I think I touch on this above, but I can say more. I wouldn’t say that I felt that older poets were dominating presences. The poets who meant the most to me were the poets who meant the most to my father: Gary Snyder, Wendell Berry, W.S. Merwin, Donald Hall, Jane Kenyon, Forrest Gander, etc. Actually, my father and I have met and/or corresponded with many of these poets. I met Snyder when he came to Freeport, IL to give a reading, and visited us on the farm. My Dad and I have both corresponded with Berry, and I’ve corresponded with Merwin. We both know Forrest. The point being, it was clear to me early on that being a poet was about more than writing poems. It was a whole life, a way of being in the world. It had a lot to do with friendship, with the simple pleasures of sharing a meal and some drinks, trying to say something for the earth and our presence upon it. In other words, it struck me that to be a poet was to take up a kind of moral calling. So rather than their presence being dominating, I felt that a kind of gauntlet had been laid down that I better walk if I was going to call myself a poet. Now, whether I’ve actually managed to walk it is another matter, that I can’t speak to.

3. What is your daily writing routine?

Right now my routine is waking up, trying to write, realizing I have to get my shit together and drive an hour to school, and daydreaming about what I would have written had I been able to stay home. I’m teaching a lot at the moment so I’m hardly writing at all. Certainly no poems. An occasional short story. Anyway, when things are calmer I write in the mornings. After noon I’m kind of worthless. Sometimes I’ll work on poems at night: they seem to require less attention than fiction does. What I mean by that is that poems seem to exercise a different part of the brain. I think it’s actually best to be a little tired, a little distracted, when working on a poem. I don’t like to bear down on them too much, or exert too much control, whereas, with fiction, it’s quite a bit different.

4. What motivates you to write?

I don’t really know anymore. Actually, I’m concerned that I’m losing the will to write. I used to write so much that it bordered on obsessive-compulsive behaviour. I have, in a file cabinet at home, approximately 1700 poems. I don’t write like that anymore. I don’t feel the pull to write about everything like I once did. I used to have to write in order to feel that I had experienced something. In some ways I’m happier, not writing all the time, but when one has identified oneself as a writer, to not write is a terrifying thing. These days, what motivates me to write is the thought of sharing the work with a half dozen or so people (my parents, my brothers, several good friends). I’ve pretty much given up on the publishing world, selling a novel, going on book tours, all that bullshit. I’m more or less writing letters to people I love, only they’re in the form of poems and stories.

5. What is your work ethic?

Well, again, it used to be much stronger! I’ll say this, though: I work hard, harder than anyone I’ve ever met. I don’t say that to brag. I’m actually not all that proud of it. It comes, probably, from having grown up on a dairy farm, and watching my dad get up every single morning at 3:30 for thirty years without a single day off. I approach writing that way. I had a pretty woeful time in graduate school because I encountered poets who don’t think of writing in that way, and I judged them, thinking they were lazy, or fake. The truth is, they were just working differently. Anyway, I like that phrase, “work ethic.” It really is an ethics of work. For me, the ethics of work is the ethics of dairy farming. For someone else, the ethics of work may be very different. Who am I to judge them? I just grew up in a particular world that has guided the way I approach my work. And so I am always reading, always writing or trying to write, always bearing down on one page or another, either mine or someone else’s.

6. Who of today’s writers do you admire the most and why?

Haha, hmm. Well, I don’t admire too many. Hardly any fiction, most of it strikes me as absolutely inane bullshit that is only getting published because it might sell books. Only a few poets. Maurice Manning, for how he has blent his work and his life in Kentucky. Joanna Klink, whose poems strike me as truly vital and consequential. Ilya Kaminsky: I trust and admire his patience and his passion. My friend Nate Klug, whose poems are as perfect and precious as diamonds. Yea, that’s about it.

7. What would you say to someone who asked you “How do you become a writer?”

Read. Read until you find writers who make you so envious that you would die to write like them. Then try to write like them. Try to write like so many of them for so long that you eventually write like yourself.

8. Tell me about the writing projects you have on at the moment.

Oh there are so many. I’m like Coleridge in this. I have a thousand ideas and hardly any of them ever come to fruition. I’m experimenting with several different novels, trying to get one to click and carry me forward. One is about the appearance of the Virgin Mary to a community of beleaguered farmers in the midst of the Farm Crisis of the 1980s (but it’s a hoax perpetrated by the mother of the boy who sees her). Another novel is about a young woman who marries into a dairy farming family and, over the course of several decades, tries to get to the bottom of a dark family secret. Another novel is narrated from the perspective of a farmhouse. There’s a linked story collection called BROOD XIII, following generations of a farm family, jumping every seventeen years with the emergence of the Northwestern Illinois brood of periodical cicadas. My third poetry collection will be called ALL THY TRIBE after a line of Keats’s. I’m working on a memoir about growing up on a farm, as well as a collection of essays oriented around specific substances (“Milk,” “Blood,” “Grain,” “Manure,” etc.). And I have a short story collection finished, which the NYC editors called “quiet,” which I’ll probably just self-publish online. Again, I don’t really care that much anymore about publishing, I just want to keep writing and sharing my work with the people in my life who matter most to me.

Wombwell Rainbow Interviews: Austin Smith Wombwell Rainbow Interviews I am honoured and privileged that the following writers local, national and international have agreed to be interviewed by me.

0 notes

Link

Not long ago, my wife, a composer, asked me if I would ever advise a student from a low-income family to pursue a career in the arts. I am a writer, librettist, and an arts and literature teacher. I thought the answer was obvious.

“What do you mean? Of course.”

“But they don’t have money.”

“If a student were really passionate and talented, she’d figure out a way.” That’s always been something my parents told me. “Think about what you’d do if money were no object, and then work hard. You’ll find a way to make money.”

“Your parents give you $28,000 a year. They paid for your tuition. They made it possible for you to do what you’d do if money were no object — because money was no object for you.”

I got a little defensive at this point.

“Well, my parents did it themselves. They started out with nothing. My dad worked at a bookstore and taught himself to program computers by reading books about it. He started two companies, one from his garage. My mom helped and provided additional income by teaching—”

“Right. Your dad loved technology. He loved business. He did not try to go into the arts with no money. Do you really think it would have been the same?”

“You sound like a Midwestern grandpa,” I said. “Not mine — he was the one who said the thing about ‘what if money were no object’ to my dad in the first place. But like a stereotypical conservative Midwestern grandpa. ‘It’s time ya quit that artsy-fartsy stuff and get yerself a useful degree.’”

“Well?”

“Well what?”

“You would tell a low-income student to go for it? Take out the loans?”

The truth is, I’ve never actually been asked that by a student from a low-income family. despite the fact that I have taught English, drama, and opera composition in low-income communities — and a few students have even enjoyed my classes. The reason, I’m guessing, is that for the most part, they’ve already ruled that out, likely because they have never met someone who actually acts, sings, writes, or plays an instrument for a living.

For the most part, students say they want to be doctors or social workers or lawyers, sometimes professional athletes. When students tell me they want to be professional athletes, I always ask, “What’s your backup plan?” Sure, some might make it. But most of them won’t. With sports, though, it sorts itself out pretty quickly. The students get the college scholarship or they don’t. I don’t really have to discourage them. I just have to say, maybe have a backup.

But if students want to pursue the arts, they may be accepted to an arts program without a scholarship and find themselves $200,000 in debt before realizing they aren’t going to be able to get a real paycheck with their arts degree — at least in the next decade. Sure, there are exceptions. But for every exception, there are many more people who are impoverished by their arts education or by working part-time or temporary jobs as they struggle early in their careers.

“Don’t you think conservative Midwestern grandpas occasionally have a point?”

It’s not a point that I conceded lightly, but my wife, who lived with student loans, pushed me to continue thinking beyond the often unrealistic narrative that all it takes is talent and work.

We spend a lot of time in the New York City theater scene talking about ways to create more performance opportunities for “new voices,” meaning historically underrepresented groups, such as women and people of color. We talk about ways society as a whole tends to favor straight white guys and how that manifests itself in the arts. And while these conversations are important, and while I agree that society is, often, skewed to favor those SWGs (bless their hearts), it’s amazing how little time we spend discussing the largest, most obvious barrier to new voices in the arts: money.

After college, I was expected to earn my own living. My parents had paid for tuition and room and board through my undergraduate degree in English at Yale, which, because we didn’t quite qualify for the school’s generous financial aid, meant something like $180,000 a year. I was able to graduate debt-free, unlike 71 percent of American students who graduate with student loans.

After school, I worked as a receptionist, then as a public high school teacher and coach in Baltimore making around $45,000 annually. For me, it was plenty. My rent was low. I never ate expensive meals, almost never shopped for clothes, bought my groceries from Aldi, and was able to pay off my heavily subsidized MA in writing at Johns Hopkins. Baltimore City paid 75 percent of my master’s degree cost; I covered the rest.

I was able to pursue my goal of writing in a very part-time way during the academic year and in a more serious way over summer breaks. I finished drafts of three novels and a short story collection, but I didn’t have time to think about publishing my work. I didn’t have the energy to do the submission/rejection/revision routine (an extremely time-consuming, somewhat expensive process with low returns). I didn’t have any connections to the publishing industry, and I didn’t have the time to go to conferences or do additional networking. So, aside from a couple of stories that I managed to get published in small literary magazines, most of my work sat on my hard drive, where it still is today.

Then my dad received several million dollars from his shares in the sale of his second company. That’s when my parents told me they were going to give me about $2,000 a month — ultimately, this grew to $28,000 a year.

$28,000 is a dollar figure familiar to children of the wealthy. It’s the maximum amount a couple can give to an individual tax-free. Wealthy individuals are frequently advised by their accountants to do this to avoid the (quite low) inheritance tax. It results in free income for wealthy kids. I don’t even report it to the IRS — and that’s entirely legal. I could get this money every year for the rest of my life, or as long as my parents choose to give it to me, without having to lift a finger. I took the money, spent part of it helping my then-boyfriend pay off his student loans, and put the rest in the bank.

After three years of teaching, completely exhausted from my crazy schedule and the emotional toll of teaching in a broken system — and frustrated by my inability to finish or publish any major projects — I decided to move back to Missouri to see if a normal “9 to 5” job might leave me time to pursue my creative writing career. It didn’t. I still couldn’t find a foothold. I ultimately managed to scrape enough time together to self-publish a novel, but I didn’t have the extra time to market it. Despite positive reviews and feedback, the book didn’t sell many copies outside of my friends and family.

I needed to change tactics and mediums. I decided to bite the bullet and move to New York to pursue writing for theater full-time. This time, I knew I’d need regular feedback and networking connections. I started a graduate degree: an MFA in musical theater writing at New York University. My parents agreed to pay the remainder of my tuition after a small scholarship, spending another $70,000 or so for the two-year program. I was nervous, but I was driven. And I had enough money — $28,00 a year, to be exact — that taking a “risk” wasn’t exactly risky.

Of course, New York is expensive. When my boyfriend suddenly left me, I had to pay $1,450 a month, or $17,400 a year, for rent on my own, not including utilities. I quickly drained my savings and found myself dependent on the gift money from my parents. My work-study position and stint as a brunch hostess — all I could manage during my intensive program — were not enough to cover basic living expenses.

Still, when I graduated, I had a huge advantage over many of my classmates. I was debt-free, and the $28,000 kept coming.

$28,000. A person in my home state of Missouri can work 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, and make only $16,328, and still have to pay tax on it. So what does this $28,000 a year mean to me as an artist? The biggest thing it buys is time. Instead of working 50 to 60 hours a week at “survival jobs,” like many of my art school friends, I was working 20 to 30 hours a week, which included reffing for an adult sports league, “matchmaking” for a dating company, typing payroll for a law firm, and coordinating for a youth tennis league.

I was able to use the remaining time to write. I was able to take fulfilling, career-enhancing teaching artist residencies, participate in a well-connected biweekly workshop, and network through an unpaid internship, all of which helped get my career started — none of which I could have done with a full-time job.

I could also cover the “little things.” When my hard drive crashed, I just went to the Apple store that day and picked up a new $1,000 MacBook Air. I had money to pay for recordings and submission fees for workshops and contests. I wasn’t living extravagantly, and I wasn’t putting away enough to retire, but I could keep pushing ahead in my career in those crucial years immediately after school.

I finally made those connections. I got my work to increasingly bigger stages. I did that without the financial anxiety that so many of my friends have — anxiety that can lead to panic attacks. I did it without having to rely on a partner for steady income. My parents always spoke of the gift as an investment, and I did my best to make it pay off.

Still, it wasn’t until I got married this year, moved to an affordable part of Connecticut, and took on a new full-time teaching position, that I felt financially stable and responsible. Shortly after we started dating, my wife began her graduate program at a music school that covers tuition and provides a stipend and teaching opportunities for all of its students. Between teaching and commissions, we now make enough in combined income that we no longer live off the gift but can pass it along to others.

We can also start planning for a family and saving for retirement while continuing to work in the fields we love, oftentimes together. We still have to put in long hours — and we certainly aren’t famous — but we don’t have to worry. Finally, at age 33, I can earn my own way and still move forward in an arts career.

All it took was a hell of a lot of work and nearly half a million dollars from my parents.

Of course, I don’t like to talk about money around my colleagues who are struggling. It’s uncomfortable (to say the least) to think about our financial advantage. When people asked me how I made it work, I would mumble something about my teaching artist gig paying well. (It did, but it wasn’t that many hours.) If I were feeling honest, I might have said something vague like, “Well, my parents help a little.” When the talk went to student loans, I would go silent or say something super helpful like: “Well, almost everyone has them, so they probably won’t hurt you in the long run,” or, “Yeah, it’s a crisis.”

But I think it’s important for us to have real numbers to think about, which is why I’m sharing mine. We should understand the reality of the situation we’re in. Or rather, the different realities of the situations we are in. My friends are out there hustling and making all kinds of sacrifices to get a foothold and, when it’s not working, feeling like failures.

Their voices are the “new voices” we are losing. Theirs and the those of the people who gave up long before. Musicians who couldn’t afford lessons to begin with. Actors who couldn’t pay rent and eat on temp work. Singers who couldn’t afford to go to unpaid young artist programs. Writers who couldn’t afford to take a risk.