#but like non binary includes so many unique distinct labels

Text

Post where I explain what Non Binary means to "It's just the third gender" people by using maths notation

our sets:

B (for Binary)

NB (for Non-Binary)

B = {0,1} which means, the set B is made up of the numbers 1 and 0

now some people think NB = {0.5} or NB = {2} but neither of these are wholly true

NB = {C U R\B} which means, the set NB is made up of every Complex number And every Real number (these two together means basically: every possible value in maths) EXCEPT for numbers in set B

So that means, NB includes EVERYTHING other than 1 and 0. which means 0.5 is included, and 2 is included, but so is 0.9 and 500000 and -π and 12i and e. Non-Binary doesn't refer to one specific gender, it refers to Everything outside of and between the binary which is literally infinite values.

If you wanted to be REAL thorough as well you could say

NB = {C U R/B, (C U R, C U R), (C U R, C U R, C U R), (C U R, C U R, C U R, C U R) (then continue filling brackets with an increasing number of C U R to infinit)}

which means that NB is everything outside the binary AND any pair of two numbers, any group of three numbers, any group of four numbers etc to infinity. This is the best way I could think to display people who identify with multiple genders at once through math notation.

But, my favourite thing about all this is that if you want to be a real math nerd about stuff, you could start just saying "\B" cause that's the most basic form of notation for "Not in set B" "Not in Binary" "Non-binary"

#This post is brought to you by my seasonal interest in maths#But yeah so to fully clarify. some people identify with 'Non Binary' as their gender. this is valid and real#but Non Binary as an umbrella term includes every gender outside the binary. so in terms of discussion and stuff#some people reduce 'non binary people' to a demographic as if it's like. one gender shared among everyone#but like non binary includes so many unique distinct labels#and so many complicated obscure experiences that are so different for so many people#and I'm interested in maths and i thought this was a good way of explaining that#like there are Infinite numbers between 0 and 1 (infinite different identities between the binary genders)#but there are also infinite numbers Outside of the binary above and below#and there are ALSO infinite numbers on a completely seperate AXIS if you consider complex numbers#and there are also GROUPS of numbers if you consider multi gender people#I love numbers and i love gender#if this post is bad takes btw pls lmk I've not thought everything though fully I'm mostly just enjoying maths

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Tired Transsexual

Published: Sept 1, 2023

Tired Transsexual*

When I first encountered the “trans community”, I carried the belief that it was built on acceptance, understanding and compassion. That it was a safe haven for individuals like me—transsexuals, propelled by dysphoria, navigating the deeply complex, intensely personal journey of sex reassignment. Sadly, over time, I’ve witnessed this community increasingly transform into a platform for what can only be described as sociopathic narcissism, exploiting the struggles of transsexuals for its agenda, and displaying an alarming antipathy towards those who refuse to comply with its convoluted narratives.

I want to first clarify what I mean by sociopathic narcissism. Sociopathy and narcissism are both personality disorders characterised by a lack of empathy, a sense of superiority and a disregard for the feelings and rights of others. When I apply these terms to the trans movement, it’s because I see a system that prioritises individual self-expression and validation over collective welfare and truth.

It’s a system that promotes self-identification over biological and psychological realities, invalidating the experiences of transsexuals who suffer from sex dysphoria. It’s a system that conflates the struggles of a minority with the desire for limitless self-definition of the majority, undermining the fight for legal protections and medical assistance that transsexuals desperately need. It’s a system that forces transsexuals into the same category as crossdressers, drag performers and fetishists, further stigmatising and marginalising us. A system that cares more about the societal validation of “non-binary identities” than the welfare of the transsexuals it claims to represent.

We, who should be at the forefront of the trans movement, are instead pushed aside, silenced, or even vilified if we dare to challenge the ideology. We are othered as “true transsexual scum”, “transmedicalists” and other derogatory terms simply for stating that our experiences are rooted in an unchosen, deeply distressing medical condition, not a fluid sense of gender or a rebellious stance against societal norms.

“My username reflects the exhaustion of navigating a world that often misunderstands or misrepresents transsexuals, not a personal failing. The tireless effort to seek clarity amidst ignorance isn’t a me-problem, it’s an us-problem. So, if I’m tiring myself out, it’s only because I’m doing the heavy lifting in conversations that most would rather sidestep. And if that’s exhausting for you to witness, imagine living it.”—tweet, Tired Transsexual, 30 August 2023

We are berated and vilified for seeking and advocating for medical treatment, which for many of us is a matter of survival. We are dismissed when we point out the very real differences between us and non-dysphoric individuals who claim the trans label. We are accused of being exclusionary, of being gatekeepers, when we simply ask for our unique struggles to be acknowledged and respected. We are denied the right to speak to our distinct experiences and needs by those who claim to care about us the most, and this leaves us with a profound sense of despair and hopelessness.

An equally grave consequence of this “trans umbrella” and gender ideology manifests in paediatrics. Misconceptions and ill-informed policies can lead to irreversible decisions made for young, gender non-conforming children who may not have any true discomfort in their sex, yet have been encouraged to consider sex-reassignment therapy under the guise of “affirming their gender”. The severity of this issue and its implications for everyone included in the ever-expanding trans umbrella cannot be overstated.

For readers unfamiliar with this level of nuance, consider the potential repercussions. When mainstream society finally grasps the potential harm being done, the backlash may reverberate beyond paediatric gender clinics and queer theory activist groups, negatively affecting public support for the LGBs & Ts—the lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transsexuals—who never asked for any of this.

“Many transsexuals worry that minors may be unable to give informed consent in an era where gender non-conformity and transsexuality have been intentionally conflated with transgender.”

The concern among transsexuals about paediatric transition is multilayered. Those of us who have gone through hormonal and surgical sex reassignment interventions ourselves understand how difficult and irreversible the process is. Many worry that minors may be unable to give informed consent in an era where gender non-conformity and transsexuality have been intentionally conflated with “transgender”, and where medical transition has been glamorised as a mechanism to achieve “gender euphoria” or “trans joy”, rather than a means of reducing distress and trying to reach a baseline of normalcy.

Additionally, many transsexuals argue that natal males and females should be treated differently in diagnostic safeguarding due to observable differences in aetiologies—teenage females dominate the red-flag category of “rapid-onset gender dysphoria”— and the greater difficulties of “undoing” the effects of male pubertal maturation when embarking upon medical transition.

While there are those who advocate for an outright ban on paediatric care, this viewpoint is far from universal among transsexuals. Many of us fear that such a ban would give momentum to those who want to ban sex-reassignment interventions altogether, creating a harmful domino effect and an existential threat to our lives.

In essence, the prevailing view among transsexuals is not against paediatric care itself, but against a medical paradigm where the clinical understanding of “gender dysphoria” has become completely detached from the sex-based strife that we experience. In our view, the watering down and genderfication of diagnostic codes (the DSM and the ICD) is a grievous mistake. Those classifications used to recognise transsexualism as a condition involving discomfort over sex characteristics. Now transsexualism is a diagnosis no more, and the reality of discomfort has been obscured by identity politics.

We argue as transsexuals that the psychosocial diagnostic model should be aligned with the emerging neurobiological understanding of dysphoria, with a primary focus on own-body sex perception, not perceived conformity to gender roles.

My own experience resonates much more closely with not just the older diagnostic category of transsexualism, but also with Stephen Gliske’s controversial 2019 theory, which proposed that dysphoria is a sensory perception condition caused not by cerebral sex dimorphism, but by the profound ways our brains map our sense of self, characterised by sex-atypical primal behaviour, own-body sex perception and distress, fear and anxiety. Unfortunately, Dr. Gliske’s paper was retracted by eNeuro in 2020, after a sustained activist campaign was launched against the journal.

Today, transsexuals are such a marginalised sexual minority that our very existence doesn’t warrant a mention in the American Psychological Association’s latest guidelines on sexual minorities, despite transgender being defined as an apparently limitless umbrella term. In defining transgender this way, they acknowledge it is not synonymous with the word transsexual, yet they simultaneously choose to dismiss this meaningful distinction by omitting a term that once gave clarity, recognition and respect to our distinct medical condition and biological reality.

How can the medical community provide us the care we need when we’re vanishing from the very documents guiding that care? How can transsexuals have honest, meaningful discussions about our healthcare, our rights, our lives when our very identity is stripped from us without any consultation?

“The inclusive transgender umbrella has, paradoxically, left transsexuals out in the rain.”

The trans movement, in its quest for inclusivity, has become a breeding ground for self-centred entitlement. It has completely lost sight of its initial purpose—to advocate for the rights and well-being of transsexuals—and has instead morphed into a free-for-all where any and all boundaries are viewed as oppressive, and where the feelings and experiences of actual transsexuals are disregarded by gender ideology (i.e., the notion that “gender identity” is a universal trait, rather than exclusive to people with transsexualism). The inclusive transgender umbrella has, paradoxically, left transsexuals out in the rain.

There is an urgent need to reclaim our narrative, to bring the focus back to the realities of being transsexual. As a society, we must resist the sociopathic narcissism that has overtaken the trans movement and re-establish a distinct space for true understanding, empathy and advocacy for transsexual rights and recognition. This struggle is not for an abstract, ever-broadening notion of identity. It is a fight for our right to exist, to receive the medical care we need, and to live our lives without being swallowed up in an all-encompassing trans umbrella that erases our identity and deprives us of the very language we need to articulate our experience. It is a fight for acceptance, not as an identity, but as human beings with unique experiences, challenges and needs rooted in material reality. We are transsexuals and we deserve to be seen, heard and respected as such.

Every application of the term transgender to us is an attempt to mask what we have done and as such co-opts our lives, denies our experiences and violates our very souls. We have had enough.

* Tired Transsexual is the pen name of an Anglo-American male-to-female transsexual who lives in the U.K. Her Twitter account is @tiredtransmed

==

"... gender non-conformity and transsexuality have been intentionally conflated with transgender.”

This is both deliberate and overt. Clinical dysphoria has been excised entirely from the terminology.

https://www.hrc.org/resources/glossary-of-terms

Transgender | An umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or expression is different from cultural expectations based on the sex they were assigned at birth.

https://www.stonewall.org.uk/list-lgbtq-terms

Trans

An umbrella term to describe people whose gender is not the same as, or does not sit comfortably with, the sex they were assigned at birth.

Literally, "gender non-conforming." It doesn't even allude to the very new phenomenon of late-onset anxiety around puberty. You're "trans" if you don't conform to outdated stereotypes.

Which becomes dangerous when gay people and those with autism, who are on average more likely to be gender non-conforming, are tricked by activists into thinking they were "born in the wrong body" in service to a Marxian cultural revolution.

It also means unremarkable and completely normal people can declare themselves "non-binary" or "cakegender," pretend to be "marginalized," and demand rights that they already have or aren't entitled to, and call you a bigot for not going along with it. And as the umbrella grows without limit, it further edges out transsexuals through this anti-trust takeover.

You're not a bigot for rejecting genderwang. Indeed, transsexuals are counting on us to do so, to help them take back both their healthcare and their dignity.

#Tired Transsexual#transsexual#gender dysphoria#transgender#trans joy#gender euphoria#medical malpractice#medical corruption#medical scandal#queer theory#gender ideology

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesbian Genders

"Wait", I may hear you ask. "Aren't lesbians, you know, women?"

Well... often yes. (Though there are some who are not women, and identify as other genders, such as non-binary, like me.) However, there are also specific gender identities that lesbians may use to describe their identities in more detail, using gender markers unique to lesbians, most notably butch and femme.

In Western popular culture, butch and femme are held in opposition to one another and are often paired in romantic or sexual couplings, seen as a sort of gay version of a heteronormative man-woman pairing. But there is so much more nuance to these personas than these assumptions of butch and femme gender identities.

Multiple authors, like Lucy Jones, Alison Eves, and Don Kulick consider butch and femme identities to be subversive critiques of the hegemonic position of heterosexuality, created in specific contexts. These identities are distinct forms of gender presentation, play, and even erotic role-play, used in the mirroring of desire, approaches to emotional connection, and other aspects of gender and sexuality. They are spectrums of feminine identity, using conscious choices of styles, gender performance, and stereotypes to build distinctly lesbian personas.

Butch identity is not necessarily the acceptance of 'masculine' ways of doing and being, but instead a rejection of the 'feminine' ways. There may be a focus on the feminine stereotypes of dress (skirts, long hair), behaviour (polite, nurturing), posture (sitting upright, taking up little room), and so on, and a distinct choice to not follow those stereotyped behaviours. Rather than being an inversion of feminine gender to masculine gender, butch is instead a projection of a specifically lesbian gender identity, distinct from both normative femininity and masculinity.

Femme identity, on the other hand, is a different projection of lesbianism as gender. Feminine stereotypes, especially regarding style and beauty, are leaned into and subverted. Presentations of femininity or hyper-femininity are used to comment and critique heteronormative standards by emphasizing certain aspects of visual appearance and behaviour, while embodying other non-normative feminine practises, namely attraction to, and relationships with, other feminine people.

Both butch and femme lesbian genders are used as, "specific patterns of sexual practice and desire, as well as being subversive re-appropriations of masculinity and femininity". However, since there are so many different ways of presenting butch, femme, or otherwise, there is a bit of an issue with homogenizing so many different identities into two very general categories. Historically, lesbian gender identities (as well as queer people in general) have been grouped together for cultural, political, and academic purposes, despite there being a huge variation in identity, presentation, and community practises. While these identities all subvert the mainstream gender and sexual structures of Western society, they all have a range of different practises, ideologies, and performances. Additionally, butch and femme are lesbian genders used by relatively few people, and lesbian as a label also does not include other cultural perspectives on gender and sexual identity. In academic studies on lesbian identity, many do not take other WLW or other gendered attraction into account (whether that be those who are not women, who experience multiple gendered attraction, or otherwise do not identify as lesbian), and also do not note the other categories which play into identity-building, such as racialisation, class, age, (dis-)ability, and so on. Keep these issues in mind when reading my posts, or others' works on lesbian gender identity.

blog references page

#lesbian#gender#butch#femme#gender performance#heteronormativity#lesbian gender#gender subversion#presentinglesbian

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Beauty of Queer Intimacy and Love: Relationships outside the Binary

This captivating series maneuvers around the beauty of everyday queer life and the documentation of queer love (platonic, romantic and of-self). A dialogue that contains a cinematography-focused visual aesthetic on tender and gentle moments with main inspirations from Clifford Prince King, Ryan McGinley and Ryan Pfluger.

Words: Cassim Cassim

The next story in this ongoing series is a celebration of the wonder and potential of trans bodies to push at boundaries of how society views gender, sexuality and relationships.

Empowering and necessary, this amateur homemade shows the beauty of how trans and gender non-confirming people deserve to feel brave, beautiful, loved and sexy.

The dating dynamic in our society is largely focused on cis-heteronormative society, which produces a distinct erasure of the experiences that nonbinary people face romantically. There is no narrative created where trans and non-binary, including people within the grey sexual community, that shows that they experience basic intimate relationships and romance. ‘Whether it's dating apps that lack appropriate gender options, transphobic partners who don't validate your identity, or mis-gendering based on appearance, there can be a lot of obstacles for nonbinary people who aren't recognized by cisgender people.’

This series documents how authentic and beautiful a relationship is with a non-binary person. Setabane had the luxury of speaking to Pixie and Junior about their everyday lives in Botswana as a queer couple.

1. What is your idea of intimacy?

(P) My idea of intimacy is being able to cuddle on even the hottest of days, watching shows together while eating our favourite comfort food, having tea or coffee together, sharing whatever snack the other is eating and downloading and playing games together. Discovering things and showing each other funny tweets or Instagram videos. Intimacy to me is the little things we do when we're spending time together because we're in our little bubble and just being.

(J) Intimacy for me is rewatching your favourite shows or movies whenever you’re at wits end with not knowing what to watch, knowing what the other wants whenever you enter a room without them, sharing tea, coffee and snacks, spending time together sharing stories about yourselves family and discovering things that you find funny interesting or curious about.

2. How do you find solace in navigating romance as a queer couple?

(P) I think about how we're not the only ones navigating this and that we've got each other. It’s just about us and not anyone else. What's comforting is that this romance has its own uniqueness and it's beautiful to see it grow and mature.

(J) I remember that in as much as society can label us and give us these names, at the end of the day it’s her and I in the relationship. Two people who before they have to navigate who they are and what they mean to the world, have to not only navigate who they are and what they mean to each other, but firstly and most importantly who they are. And what they mean to themselves.

3. What is your love language?

(P) physical touch is right at the top of my list. I'm super duper affectionate and I am always touching Junz (Junior). Limbs are always entangled, a hand is being held or we're cuddling. It’s like a veil of love, no matter how small. Quality time comes second and being made or given food comes third.

(J) My love language would be quality time, but to be specific, the quality time usually involves watching series or movies, playing games together, painting, writing photoshoots, etc. Basically I like growing, creating, and exploring with Pix. After quality time it’s physical touch which basically goes hand in hand with the quality time tbh.

4. What is your definition of reciprocation ?

(P) my definition of reciprocation is the ability to match the energy, love and effort that's being given to you the best way you can. It doesn't have to be the exact same actions as the person giving them to you but in your own special way to show that you love this person as much as they love you.

(J) When I think reciprocation I think of giving yourself to someone and not in some Hollywood sense. Falling in love with someone is being loved, and knowing and feeling that you don’t want to hold back and have no reason to and you believe in this person, and want as much for them as they want for you.

5. What is your favourite thing, physically and emotionally, about your partner?

(P) Physically, it's the baby's smile and their face. I spend a lot of time staring at Junz' face because it makes my heart skip a beat. I never get tired of it. Emotionally, they're so tender, kind and caring. I am so grateful for that and I think about it so often how lucky I am that my life crossed paths with theirs.

(J) Physically I would say, her eyes, her smile, her hands, and if it counts how her skin feels to touch. Emotionally, I love that she never thinks twice about helping those she cares about and always puts loved ones first and she is someone you can trust and rely on. But somehow I have to say that I don’t have favourites really, because all of her is my favourite inside and out.

6. (pixxie) Have you found any difficulties dating a non-binary person?

Just the usual misgendering of Junior's pronouns. It’s hard bc people don't understand why Junior prefers they/them pronouns no matter how you explain it. I guess I could add that people are lazy and dismissive because they don't really have to put in that effort to discover themselves.

7. In your own words, what does it take to be in love with a person?

(P) You have to be honest, vulnerable, considerate and have the ability to healthily communicate. You gotta be their rock and safety net. I wish I could list everything but the biggest one I feel is important is that you should feel safe and that you have found your best friend in your partner.

(J) it's difficult and impossible to say because we all fall in love so many times in our lives, and because of how different we all are I can’t even begin to think what it takes to love someone but I think I’d say to love and to be loved, is something that’s just human nature, it doesn’t have to be taught it just is, and will be, we are all worthy of love.

Credits:

Models: @bbypumpkiiiin_ & @vandeaarde.gallery

Photographers: Both

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alright so the survey on aro community needs from this post got 30 responses, and with it all being long form I don’t expect to get many more.

So what I’m going to do is give summaries of common themes and answers above the cut for people who don’t want to read through a bunch of text, and then I’m going to put individual answers under the cut for folks who are interested. Please note that these are all anonymous survey answers, and they do not necessarily reflect my opinions. I encourage people to have/start discussions around the topics brought up here so that we can work towards having a mutually fulfilling and cohesive community.

Summary:

What are the community needs of alloaros?

More recognition and visibility both within and outside of the aspec community, aro specific spaces where no one will assume that they’re ace and where they don’t have to be bombarded by ace content, safe spaces to talk about their experiences with sexual attraction, and a wider community acknowledgment that ace and aro don’t mean the same thing.

What are the community needs of aroaces?

Separate aroace spaces, space and language that allows them to express the interconnectedness of their aro and ace identities, a recognition of the diversity of aroace experiences including the experiences of oriented aroaces and aro leaning aroaces, spaces devoid of both sex and romance, and less infighting between the aro and ace communities.

What are the community needs of non-SAM aros?

New language that doesn’t enforce the use of SAM as a norm and that doesn’t enforce a SAM/ non-SAM binary, more recognition of aromantic as one whole identity, more inclusion of their identity within aro spaces, and having the ability to label themselves as aro without being asked what their other identity is .

What are the community needs of greyro/ aro-spec folks?

Specific spaces where they can talk about aromantic attraction, more recognition and visibility both within and outside of the aspec community, more greyro/aro-spec specific resources and content, and a larger platform within the aspec community to discuss their experiences.

What are the shared needs of these different subgroups within the aro and arospec community?

Increased visibility, spaces free from amatonormativity, safe and unbiased shared spaces for all members of the aro/aro-spec community, separation and distinction from alloaces, more in-person spaces, and a building of understanding and acceptance between the different community subgroups.

How do we meet all of these needs within an online space?

Better and more formalized tagging systems, creating more forums, chats, tags, etc, that are specific to different aro and arospec subgroups, creating more variety in online aro spaces generally, giving equal online spaces and platforms to all aro subgroups, and having open and polite community discussion about our needs within online aro spaces.

How do we meet all of these needs within an in-person space?

Use inclusive language, allow for smaller sub-communities within larger aro and aspec groups, provide resources for small, lesser known identities both within groups and at pride, push for more aro inclusion in wider queer spaces and create safe and respectful discussion spaces where everyone can voice their needs

How do we reconcile conflicting needs?

Civil and open discussions, try to find solutions instead of just arguing, and create separate spaces for subgroups when needed while continuing to maintain larger general spaces for discuison and community building.

Individual answers:

What are the community needs of alloaros?

1. A space to be aromantic but not asexual. As an alloaro myself, I struggle to relate to many aroaces - and the ace community in general - because my sexuality is a big part of my identity, right along side being aromantic. I want a place where I can discuss how being aromantic affects my sexual attraction without having to focus on one or the other

2. A place to talk about sexual attraction without being ridiculed or being called a player. Advice about how to go about getting a relationship that fulfills their needs without be demeaned to expected to evolve into romantic.

3. I'm not alloaro, so I don't feel comfortable speculating on their behalf, but from the perspective of an outsider looking in, they need more visibility, both within and outside of the aro community.

4. Recognition mostly, acknowledging that asexuals can’t keep putting their stuff into the aro tag, the fact that romance repulsed allo aros exist and are uncomfortable with allo aces putting their stuff everywhere

5. Aro specific places. I personally don't have to talk about sexuality in general areas but aroallo specific places/sites/tags for this would be great.

6. Dismantling the assumption that aromanticism is inherently linked to asexuality (even if it is for some individuals, it's most definitely not a hard rule that applies to everybody else), moving away from seeing aroace as the "default" aro experience and in fact not assuming one's other possible identities because they identify as aro at all

7. Not one myself - probably spaces to find safe hook-ups if desired, to talk amongst themselves

8. Less ace experience talking over aro experience. Also, not conflating the two identities as one.

9. I often feel ashamed of the allo part of my identity. I think more visibility would help a lot. It also took a very long time for me to even consider being aro because I was under the impression I had to be ace so separating those ideas would help.

10. As I’m not allo aro I can’t really say, but a lot of them have been speaking out and saying that they don’t want aro to automatically mean aroace, and that aromantism is not a sub sexuality is asexual

11. To talk about alloaro specific issues freely, and to not be assumed to be ace or to have to leave our sexualities at the door when entering aro spaces

12. Increased awareness that one can experience sexual attraction without romantic attraction

13. To be respected and given a aro-specific space/platform to discuss their needs/issues/etc

14. A space to not be: assumed ace, confused with aces, forced to avoid talking about how they want sex without romance and how that sexual desire affects them, etc. A space where they can find others like them to help them understand themselves better and make friendships and feel less isolated.

15. i'm not alloaro so i'm not going to speak for them but like. acknowledging that aro does not mean ace and allowing the aro community to exist outside of the ace umbrella is super important

What are the community needs of aroaces?

1. Recognition that aro is an equal and completely it's own community but that the community doesn't have to be completely separated.

2. Separated areas where uniquely aroace experiences can be discussed

3. Less infighting between the aromantic and asexual communities. You can and should call out hurtful behavior by the other community, but going into isolation mode leaves aroaces stuck in the middle of two sides retreating in on themselves. Aroace issues are aro issues! Aroace issues are ace issues!

4. Acknowledging that we occupy a unique overlap between the aro and ace communities that no other perioriented people experience (if we can even call ourselves perioriented, since we're basically forced to straddle two communities or else have one aspect of our identity erased); having spaces where we can talk about our aroaceness without having to separate out our identities, when we often can't

5. Well if you mean just "aroaces" who use it as one word for a convergent orientation they need a place where mixing up and "confusing" an experience as related to their aromanticism when it's more about being ace doesn't get aros yelling at them in the Tumblr tags that they shouldn't tag it aromanticism and they're stupid/horrible hurting aros when they do. They need a place where they can talk about their experiences as very interconnected and inseparable without offending people for whom they are separable. They likely mostly want to learn from allo aros and allo aces what it feels like to be allo so they better understand more of society and don't want to feel alienated from either community of aces as a whole or aros as a whole.

6. I just want some safe wholesome space. Since I joined the aro community on tumblr couple years back, it just feels like the community is defined by discourse, negativity, fights, petty disagreements and drama. I understand, the community is still in diapers and we need to figure ourselves out, but I feel like we've lost the way. Do we need to react to every troll and hater? Is seriously someone offended by them? Why do we legitimise and acknowledge them as part of the discussion? It's like giving an equal platform to scientists and flat earthers. Is this really how we want to be? If you try to think away all the drama stuff, what's left? Is there anything left at all?

7. The freedom to find their place in both ace/aro spaces and for people to allow them to use/not use the SAM as they see fit. Perhaps giving non-SAM aroaces some new language?

8. More community for aro aces. As an aro ace myself I always have to divide time between the aro and ace communities

9. a space where both identities are recognised as equally important - a space where aro identity isn't seen as a subset of ace identity, or deriving from it - somewhere they can express romance and sex repulsion or lack of thereof

10. A term that isn’t AroAce. Something that is not just a combination of aromantic and asexual. But to also not be a sub set of allo aro or allo ace. We shouldn’t need to choose which identity is more important and we shouldn’t have to use the SAM.

11. I think to recognize that there is an aroace spectrum. You can be mlm, wlw, nblnb, etc and still be aroace

12. Content that doesn't rely on "but we still experience x attraction!", tips for living alone/single, also tips for finding/being in a committed relationship such as a qpr (I personally want a relationship but I have no idea how to even start looking for one)

13. I am not aroace so my opinion should not carry as much weight as others but from what my aroace friends irl say, I think we need more recognition for oriented aroaces

14. To be able to talk about the intersection of our identities and how we are uniquely impacted by aphobia

15. Understanding that not all aroaces feel that their two identifiers hold equal value to them (e.g. aromantic as a primary identity with asexuality as a secondary identity). Letting people focus on the one identity over the other is not an exclusion on the other identity; their preferred identity is just more meaningful in their lifes and/or personal growth.

16. Available spaces that are not only sexualised spaces (eg clubs), options to avoid discussion of sex, being hit on if desired (colour code in mixed irl aro-spaces?)

17. Aroaces need a space where they don't have to pick between their aro and ace identities, as well as a space where sex and/or romance repulsed aroaces dont have to deal with romance or sex in any way

18. Idk, not aro ace but I would say recognition as well

19. Full disclosure, I've mostly stopped participating in the ace/aro communities of late (though I haven't stopped reading it) because it felt like every time aroaces spoke up, we were brushed aside or shrugged off because we were the "privileged" ones (in both aro and ace circles). That means I'm a bit out of the loop. I identify far more with my aromanticism than my asexuality, but I've definitely been made to feel that I'm somehow a negative influence on both communities because I technically belong to both. I feel bad enough discussing my identity outside of the ace and aro communities, particularly among queer friends - it feels like when I bring up aroace experiences, it's like I've doused the fire of whatever conversation I was in, and I don't feel like replicating that feeling by trying to talk about it on the 'net, too. So, I guess we mostly need acceptance. We need spaces where alloaros can talk about their experiences without feeling bombarded by aroaces, we need spaces where aroaces can talk about our experiences without feeling like we're marauding on allo experiences, and we need places where both sides can talk about our aromanticism as one community. We as aroaces need to do better about determining when to discuss our issues, and making sure we're discussing them within the communities they're relevant to, as well. I have a pretty solid handle on which aspects of my identity are informed by my aromanticism and which are informed by my asexuality, but that's not a universal experience. Plenty of people have issues separating the two, especially when they're missing both sexual AND romantic attraction. It's hard to determine which of those "missing" pieces are supposed to fit where, and it's important to understand and find a place for these people to post, as well. But ultimately there needs to be more acceptance and openess all around. And I have no idea how we can do all of this.

20. Often aro and ace-ness are inseparable to aroaceness and thus unless something is very specifically about sexual attraction aroaces need to have a sense of flexibility

21. Honestly, as a greyro-ace myself, I feel like aroaces are sort of the face of the community

What are the community needs of non-SAM aros?

1. it's all in the name 'non-SAM' for me. that it is assumed everyone has multiple attractions and/or labels themselves by them. it's use rather implies that the words aro or aromantic or aro-spec /don’t/ automatically include us. it's obviously a perspective change needed here, maybe a new term or descriptor as well? i don’t kno really but i hate the specification of — the expected /need to/ specify — non-SAM.

2. I'm gonna skip the other Qs b/c I don't think I can speak for SAM-using folks. Anyway, as a non-SAM aro I think some of my big things are 1. Recognizing that aromanticism can be its own identity without being split or modified 2. Ending the default assumption that I am ace, identify as ace, and know what the heck ace people need in their communities. 3. Recognizing and respecting aros who don't want or desire QPPs and making it clear that non-QPP friendships and family are not only as good as but can be just as fulfilling as other relationship models. 4. Including non-SAM people as part of our basic and default definitions of asexuality and aromanticism. 5. Making space for discussions of why microlabels don't work for everyone and why the SAM doesn't work for everyone 6. Making an active effort to make aspec spaces more accessible to folks who have just learned about aspec stuff, folks with cognitive and language disabilities, and non-native English speakers. And, like on a broad note, my autism makes it difficult for me to break my identity into tiny pieces. The aspec community's focus on microlabels and the split attraction model, plus the fact that the people participating in discussions often seem to be younger than me and just barely in the process of developing an identity that I've been comfortable in for many years, makes me feel isolated and alienated from the community. When I do participate, the complex and high-entry-level jargon that some members of the community use make it difficult for me to participate in community interactions, which leaves me feeling even more alienated.

3. again, not speaking over other people, but it's important to recognize that aromanticism is a full identity on its own and doesn't inherently require use of the SAM. breaking down the alloaro/aroace binary

4. It seems they want to just talk about aromanticism without having people judge which type of aro they are for if their views count etc. They want more than anyone for aces to be better allies when it comes to LGBTQIA arguing where the A doesn't mean Ally and rather asexual that there needs to be room for the queerness of aromanticism in the LGBTQ+ umbrella. They more than anyone will always need aromantic specific everything - recognition, representation, communities, where no one expects you to also be something else

5. For myself, mostly non binary language and less assumptions that all aros ID with the SAM would be helpful, also acknowlement that non-SAM aros may have differing experiences as a group. This sounds small, and honestly it is, but the unintended consequence of binary language addressing only 'aroaces' and 'aroallos' that I've seen is that spaces can become increasingly polarized between different split attractions and then I've just kind of slipped through the gap in between. It's just my personal experience, of course, but honestly just including this box in the survey is a great start.

6. In-space focuses and new language.

7. More awareness

8. A space where we don't feel the need to express ace/allo identity alongside our aro identity

9. To not get caught in an alloaro Vs aroace war that they can't pick a side for, is probably one.

10. We just need ppl to stop kind of adding us in a sentence in their post or say 'not everyone uses the sam' I wish we could have more discussions on why the sam doesn't really work for us or how we're left out from the community as a whole.

11. Acceptance of just being aro. Aromantic is a whole independent identity despite where it was born.

12. A space to talk about how the ace community has harmed them or made them feel unwelcome without aroaces or alloaces acting like it is an insult

What are the community needs of greyro/ aro-spec folks?

1. Understanding that not everyone is completely aro or that their romantic attraction levels change.

2. providing spaces to talk about experiences with romantic attraction/relationships

3. I'm in this group. I need to feel like it's ok that aromanticism stay a spectrum and some aros are "more ace" (I'm sex-averse etc) than clearly aro (I might choose to date) and to not feel like people are accusing me of being alloromantic when I don't feel alloro. If people make sweeping statements about aros that don't include me or sweeping statements about alloros that do cover my experiences, it is hurtful and invalidating of my identity. And it even can make me doubt myself which isn't fair after I've spent years figuring myself out. I want a happy community that can get along and not hate aces preemptively before any of the select aces they're talking to did anything wrong. Who can forgive aces who make mistakes but who want to be better allies. I'm an ace and an aro-spec person. I'm an ally to aros who aren't gray but all forms of people being an ally takes some learning curve. Understanding that can go a long way.20 hours agoMore awareness21 hours agomore discussion about our orientations, more material for us in general, people getting a platform to share heir experiences. i feel kind of isolated in the aro community because there isnt a lot thats directed at us and our experiences that are neither really aro nor alloa day ago- a space where romance repulsion and simultaneous lack of thereof is acknowledgeda day agoIdk I'm not on the speca day agoMore content for the smaller identities under the spectrum umbrella would probably be nice, also asexuality being jammed together with aromanticism can be annoying sometimes especially if the post only really has to do with one or the other. Visibility in stories and media and such would also be greata day agoacknowledge that not everyone is strictly ace or allo. Like alloaros, allow us to talk about whether we want romantic partners or how our experiences differ from non grayro aros.a day agoN/aa day agoTheir own voice for their complicated feelings about being on the aromantic spectrum.a day agoNot greyro, likewise not my place to comment.2 days agoThe aro community is actually already pretty good about this, but it's cool that romance still happens for some of us and that out voices are allowed to at the very least be on our own space without criticism.2 days agoUh2 days agoArospecs need to be able to talk about their approach to romance, as it is very often very separate from the way allo people experience romantic attraction2 days agoI think both grey and demi aromanticism and asexuality in general need more recognition 2 days ago

4. More awareness

5. more discussion about our orientations, more material for us in general, people getting a platform to share heir experiences. i feel kind of isolated in the aro community because there isnt a lot thats directed at us and our experiences that are neither really aro nor allo

6. a space where romance repulsion and simultaneous lack of thereof is acknowledged

7. More content for the smaller identities under the spectrum umbrella would probably be nice, also asexuality being jammed together with aromanticism can be annoying sometimes especially if the post only really has to do with one or the other. Visibility in stories and media and such would also be great

8. acknowledge that not everyone is strictly ace or allo. Like alloaros, allow us to talk about whether we want romantic partners or how our experiences differ from non grayro aros.

9. Their own voice for their complicated feelings about being on the aromantic spectrum.

10. The aro community is actually already pretty good about this, but it's cool that romance still happens for some of us and that out voices are allowed to at the very least be on our own space without criticism.

11. Arospecs need to be able to talk about their approach to romance, as it is very often very separate from the way allo people experience romantic attraction

12. I think both grey and demi aromanticism and asexuality in general need more recognition

What are the shared needs of these different subgroups within the aro and arospec community?

1. what we need across the board is recognition, compassion, and dissemination.

2. More aro recognition and its own and equal but not completely seperate from ace (for aro aces) community.

3. To discuss their experiences with the lack of romantic attraction and amatonormativity, amongst other General arospec issues

4. safe spaces to talk about being aro and all of the ways it intersects with other aspects of our identity; representation and advocacy

5. Neutral aro-spec spaces where all intersectionality is equally accepted but also not the main topic or qualifier; recognition of a broad range of experiences; recognition of specific language and acknowledgment of their existences; facilitated ability to speak about more specific or 'niche' topics

6. Recognition in queer spaces and healthy dialogue about language.

7. i think we all want a platform for our specific topics and we want recognition, but also community

8. A space where romance repulsion is acknowledged and respected - a space where aro identity is prioritised, no matter what other identities go along with it, if there are any at all

9. To move forward in our activism to make aromanticism more well known and more accepted in society?? And to have a safe place to go after a day of dealing with amatonormativity and aphobia.

10. To make ourselves exist outside the definition of asexual

11. I think all the communities/identities need to recognize that there is a problem. If we unite with each other and have so much love and understanding in the form of unity, I think a lot of these problems will resolve themselves.

12. Visibility?

13. make sure we understand each other's experiences and what makes everyone feel included / excluded. We need to make that we sure we own up if we excluded someone, and that we try to fix it.

14. Visibility is my greatest concern for all aspects of aro and arospec problems.

15. Aces need to stop speaking for them. Aro-spec and aro people can speak for themselves on their own experiences. Additionally, aroaces need to focus more on the aro identity (whether it's primary or secondary to them) when it involves aro discourse. They can have a focus on their ace identity only with the exception that both identities are heavily tied to each other and both identities are discussed. Again, this is specifically for aro-specific discourse.

16. Discussion of amatonormativity, experiences with pressure to find partners

17. A creation of a unified aro space that includes and supports *anybody* identifying as aro or arospec

18. The validity of aro identities shaping gender identities. I believe I'm nb in large part because of aromanticism.

19. All four of these groups need visibility and more in person communities

20. Allo aces need to stop taking over everything is the overarching problem when you think about it, they also need to stop throwing aros under the bus

21. We ALL need more visibility. We need voices that aren't reliant on the ace community to speak for us as an afterthought, and I say that AS an ace. We need to talk about aromanticism as a whole. And we need to do so proudly and informatively. I've noticed that it's really, really hard to talk about aromanticism without making it sound like I'm demonizing romantic attraction, and that's a dangerous treading ground within the queer community. There's been a lot of negatively portraying queer romantice from outside of the community, and we need to make sure we're not stepping on those land mines, but we do need our voices heard on aromanticism and amatonormativity, too. Also, we need to hold fast to QPRs and squishes (and, imo, aplatonic) and not let those ideas get swept out with the discourse trash. We also need to support both the aros who want and have QPRs, and the aros who want nothing to do with them. I see a lot of support for aros in various forms of non-romantic (and sometimes romantic) relationships, but very little for aros who choose to fly solo, and what that means in a world that expects you to pair up.

22. I do think we need to be more openly vocal about our separateness from the ace community, though it seems to be tearing aroaces apart at the seams

23. A space to discuss aromanticism - however people experience it - in a space were others are opening and welcoming. Possibly also older members of the community giving advice to newer members who are struggling to come to terms with their aromanticism in a society so focused on romance

24. I feel like a lot of aros are frustrated with their experiences being mislabeled as ace experiences, or having the assumption that aro and ace experiences are basically the same

How do we meet all of these needs within an online space?

1. make sure you aren’t in an echochamber? share/create content for orientations other than your own? be kind? remember that when we're fighting it's kind of over scraps and we deserve better? i'm not sure honestly but i really think a lot of this comes down to perspective. plus remember the block button exists lol. i'm talking about things all on a personal, individual level and i don’t kno how to effect anything otherwise. how about a content creation week where the subject is an orientation other than your own? with emphasis on asking questions to get shit right. it'd be a learning experience that builds community. i can't think of a thing to answer this question on a larger scale ://

2. We accept that some people see their aro and/or ace identitie/s seperate and some don't. Also that some only have one of these identities. And we spread aro recognition.

3. Equal education and resources for all parts of the aro spectrum

4. Cut it out with the pack instinct. Aces and aros snarling at eachother really freaks out aroaces.

5. it's impossible to curate a monolithic online space that will meet the needs of every single member of the aro community. what's important is acknowledging your own biases and hearing out the perspectives of others who differ from you, and not generalizing your own experiences/needs/perspectives to the community as a whole. we can create more subgroup-oriented spaces all we want, but at the end of the day we're still part of the same larger aro community and in order for that to work out the best thing we can do is just listen to each other.

6. Appropriate tagging has been brought up before, perhaps a reworked umbrella tag system? Again more neutral spaces; appropriate tagging for repulsion and aversion and on the other end acceptance of a variety of topics (i.e. some people will be talking about sex and that's good and healthy, as long as it's tagged there shouldn't be an issue with that); more specific and intersectional spaces; less verbal conflation of ace and aro though I think that's been getting better? Then again a big problem is the aroace split between two communities. I unfortunately do not have any ideas for that

7. Provide and Aro-specific online space similar to AVEN.

8. trying to give a more equal focus to different subgroups maybe? coming together and caring about those whose experiences are slightly different from ours and giving them a platform too. encouraging diversity

9. i'm not sure but it starts by making spaces outside of discourse. blogs like "aro-soulmate-project" are especially important to me because they address not only intra and outside community issues, but because they create aro identity at the same time people interact.

10. Idk put everything in the tag it belongs in (aroace content in aro, ace and aroace tags, general aro content in aro aroace and alloaro tags, and alloaro content in aro and alloaro tags, etc) and stop harassing each other. Groups might benefit from ace chat channels and allosexual chat channels? But idk if that's too divisive in some opinions

11. Group chats? More posts combining the communities? Spreading the love to everybody everywhere!

12. Open discussion

13. Since aro communities are extremely small and have been largely ignored-even by the a-spec community-it is up to the a-spec (yes, this includes alloaces) community to be more inclusive when making a-spec positive/information posts while also making more efforts to reblog diverse aro discourse so that aro people get a chance to speak.

14. Different tags/ smaller chatrooms. Probably tags people can follow or block

15. Better tagging systems, breaking down assumptions and not projecting one's one experience of identity onto everybody else who happens to be aro, creating sub-communities that are specifically suited for a specific subgroup's needs while still being united as the general aro community

16. On tumblr, proper tagging of content.

17. I think something that would actually help is like an aroace specific forum. We have arocalypse but that seems to be mostly alloaros and I want a forum where I can be aroace and not have to pick sides

18. Tag things accordingly

19. As I mentioned before, I'm not really involved in community discussions beyond reading about them, but coming up with a standard tagging system seems to be a start.

20. Often these needs have been met, though there could be a better job of say tagging 'romance' for repulsed aros and we need to open up space for both romo repulsed and positive to speak at the same time

21. I don't know. The internet is too big to manage. I think of the internet as more of many different spaces

How do we meet all of these needs within an in-person space?

1. Represent everyone, let people speak, let people correct you, aim to make friends, remember that we're all under the A together.

2. Same as above

3. Stop generalizing and start being inclusive with language. There’s a big difference.

4. Listen, if no one ever walks up to me and says "Hey, [name], you're ace right?" just because I told them I was aro and they forgot, I will be happy.

5. i suppose the same rules apply. listening, providing spaces for subgroups to talk about specific issues, etc.

6. Similar to previous answer, but spaces advertised as neutral or with multiple groups need to be more explicit in inclusion of a variety of experiences and topics. There are ways to manage this so everyone is in understanding and comfortable, namely just good communication (hence being explicit) and systems of feedback

7. Queer spaces just need to be informed that the usual a-spec narrative is not the only one. But this will change as people share their experiences.

8. more aro awareness alongside but also differentiated from ace awareness, and all this coupled with a focus on acceptance rather than identification

9. A case by case basis? I guess? It'd depend on the scope of the space

10. Booths at Pride recognizing the lesser known orientations. Doesn’t even have to be booths! Pins, stickers, t-shirts work just fine. Maybe a logo for a-spec, aro-spec, and aroace staying that we are all united.

11. have info that includes all of us eg. pamphlets don't have the ace flag everywhere and acknowledge that their are aspecs who experience romantic or sexual attraction, and that not everyone uses the sam.

12. I have only come across one aspec space in-person but it is in the form of a discussion group and everyone is allo ace so I feel extremely unwelcome. I wish there were more resources about aromanticism I could bring to these groups.

13. For one: language is important. Renaming everything to a-spec meetups/groups instead of ace meetups/groups makes the other identity more welcomed and higher possibilities of growing the community. Again, there are more aces out there than aros at the moment, so it is up to those ace groups to make it more inclusive to all a-spec people. We're a community in this together wheter you feel a certain identity or not. That's what being Queer's all about.

14. Create an aro-space first... Then events for sub-groups only where they can talk amongst themselves but also community events

15. Have a large variety of arospec spaces to choose from so that everyone can have their needs met

16. Talk about all aspects, let people voice their experiences and find common ground

17. I don't participate in in-person communities. Partly because I'm not out to more than just a few friends, and partly because I wouldn't want to go to one and be the stereotypical aroace. I feel both far too representative of both the aro and ace communities, and also not part of either. And thanks to the discourse, I'm not convinced I'd be welcome at a queer meetup at all. In addition, I've already mentioned before that just bringing up my experiences as either an ace or an aro tends to be a conversation-killer. So, I guess it rolls back around to visibility. Making others aware of our existence so that when aro experiences DO come up in in-person conversations, we can avoid the uncomfortable, awkward silences that follow. And I think that can only be done by talking about them.

18. I'll eat my hat the day that I manage to find a sizable in-person space for aces or aros

How do we reconcile conflicting needs?

1. I believe this question is far too subjective to each instance that has and will pop up. Which is no help unfortunately.

2. We accept that sometimes someone needs these needs and someone else needs other needs. Also we ask what people's needs are before we assume their needs.

3. By talking out our issues civilly and talking about what bothers us so we can accommodate and adapt as needed if needed, and filter out people who just make the community toxic.

4. Live and let live. Talk it out. Find a solution rather than growing increasingly angry. Literally anything that’s not cocooning away in indignation, we are supposed to be a community.

5. i don't think our needs actually conflict, for the most part. with the exception of greyro/arospec folks needing space to talk about romance and romance repulsed folks needing to get away from it. but that can be solved by tagging things (at least in the case of online spaces). i think a lot of our perceived conflict comes from the conflation of different issues. for example, giving alloaros room to exist apart from asexuality and giving aroaces room to navigate that awkward space in between aren't inherently mutually exclusive. i recognize that striking that sort of balance is easier said than done, but i think if it were easy we wouldn't be having this discussion at all. we're a diverse population and our needs are ALWAYS going to differ. but we're also always going to overlap in a lot of ways, which is why the aro community exists to begin with.

6. Imagine you have a spoiled child. You can do everything in your power to give them what they need. Do you think it will be ever enough? Oh, but what's worse, by concentrating on the spoiled child, you completely forgot you have a second one, starving in the corner.

7. Give each person a choice in the language they use and don't force anyone into an identity/stereotype of aspec experience that doesn't fit. Just listen to people.

8. By giving space for both and working out compromises or plans of action

9. Definitely not fuckin argue for weeks and attack one another, discourse only fragments our tiny movement

10. Set up a time for when allo aro can talk about their experience and the way their identities interact. This lets aroace choose whether they want to come or not. The usual meeting should be a time where any aroace, allo aro, and non-sam using aro can talk about being aro. Or for aros to just meet and interact.

11. a group discussion where everyone can share their experiences but also safe spaces for aroaces / alloaces / nonsam aros /grayros to talk so ppl can discuss if someone hurt them or made them feel excluded in the group discussion and so they can talk about things that are specific to their smaller communities

12. Open discussion and properly tagging things

13. Aro people have been patient. Ace and ace-spec people need to recognize that their exclusive behaviors are mirroring the same horrible mentality that exclusionists in the LGBT+ have. Also recognize that ignoring (or consistently forgetting) the identity is a form of the excluding that identity in regards to posts that are suppose to be a-spec/Queer/LGBTIA+ positive/informative.

14. Respect and communication, separate spaces when necessary

15. Creating sub-communities that can prioritize a specific group's needs in that space while not conflicting with the general aro community.

16. Idk like listen to eachother?

17. The people who have a problem avoid? Idk

18. honestly don't know. I absolutely understand the frustrations of alloaros getting ace posts in the aro tags, and I understand the frustrations of aroaces posting their experiences and being told those tags don't belong. I think the ace community as a whole needs to be made aware that the aro tag is not a dumping ground for ace-specific posts, and that if they want to include support and positivity and include the aro tag, then the post needs to INCLUDE US. I think a lot of frustration on all sides right now is that aromanticism comes off as asexuality's afterthought, and I don't think any of us as aros feel that way. I don't think we need a full break from the ace community, and I think we need to stop blaming aroaces when we make relevant posts to the aro tag, since I suspect quite a bit of this issue is from people who legitimately don't realize that aro tags are not the same as ace tags (i.e. ace positivity blogs that post something relevant to ace experiences and think they're being inclusive by "including" aros, because "we're all aspec, just swap out the 'sexual attraction' for 'romantic attraction'!"). But I, as an ace, am of the opinion that the ace community as a whole needs a solid kick in the pants to get them to work with us on cleaning up the tags and acknowledging that aros aren't just aces with a word swap, that we have our own significantly different concerns and ways to navigate the world that aces can't understand. But here's the problem, too. The ace community is one of the larger "aro" voices right now because the aro community is really quiet. Yes, we have our voices, but if you go looking for ace spaces, you find them. You find them in spades. You go looking for aro spaces? You have to dig. You almost have to know what you're looking for before you can find it. I see aros submitting asks on ace blogs, asking where to go to find aro-specific blogs, and there's always only a handful of suggestions. I think a lot of the reason aroaces seem so visible is because we -are- in the ace spaces, talking, and the ace spaces are big. The aromantic community's biggest priority right now is to grow and be heard.

19. fuck idk tbh the most we can really do is post about it and hope people see and listen

#aromantic#alloaro#aroace#arospec#greyro#greyromantic#non-sam aro#aro#long post#this ace blabbers#Community Discussion

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

sooo i figured it’d be helpful for me to make a complete post on my thoughts on pansexual as a label. i've answered a few asks about this and then figured i'd covered it enough, but i realize that i covered separate points in each post/ask.

i'll try to make it as organized as possible, but y'all know i'm the king of run-on sentences and unnecessarily long statements and restatements. so yeah, this is gonna be a long one, fellas

"bi = two, pan = all"

in reality, the bi identity has always included attraction to all genders. i'm sure you'll've heard it time and time again, but the 1995 bisexual manifesto states very clearly that bi people are not duogamous in their attraction. insisting that bisexuality is only for attraction to cis men and cis women paints bisexuality as transphobic, as well.

the pan label became so popular with the rise of awareness of nonbinary identities because people started to find it important to state they were also attracted to nonbinary people. the whole pan- prefix was specifically picked because people were aware that "nonbinary" was merely a category for those who fell outside of the imposed male-female dichotomy, and under which several hundred genders could fall.

so... bisexual includes all these hundreds of genders, and pansexual specifies these hundreds of genders. seems redundant, but what's the issue?

"some people find the distinction important"

this is a sentiment i've heard brought up as an argument to just leave pan people alone. but i don't find it quite so valid an argument, irony not intended. *why* is the distinction so important? how come one can concede that bi people like all genders too, but you *must* let people know you are the type of "m-spec" who is definitely able to be attracted to all genders?

the idea one can id as pan but still agree that bi people can also feel the same way a pan person does is contradictory. you are attempting to label an experience as x and argue that it's a necessary label, when there was already a label for x and y. the very idea of a "distinction" is to point out how something is *different*. it's completely redundant.

so if bi and pan are the same, is there some other reason why someone would prefer pan over bi?

"attraction regardless of gender"/"hearts not parts"

i'm lumping these two together because, despite sounding like different points, they argue the same thing in the end. it's just that one is more subtle.

when the label of pansexual was in it's formative years, some sought to argue that pan *is* different from bi, because pansexuals do not consider gender when they are gauging attraction to someone. there are several problems with this.

this switches pan from a "who" label (correct usage of a sexuality label, denoting to whom you are attracted, referring to gender), to a "how" label (incorrect usage of a sexuality label, denoting in what circumstances one feels attraction, not accounting for gender). with the other definition of pan, the "who" was simple - anyone of any gender. with this definition, the "how" is now involved, that being without regarding gender.

within normal parameters of a sexuality label, as in, a "who" label, it is functionally the same as the previous definition. you are still attracted to any gender.

just as well, it can be used just as well for a bi person attracted to all genders. many bi people have stated this is exactly how they feel, and so you jump back to the distinction argument. but also, many gay and straight people have also expressed that gender plays no part in *how* they feel their attraction. their attraction may only include one or so gender(s), but beyond that, it's not something that factors in.

many trans and specifically nonbinary people have stated distaste at this definition as it is dismissive of gender. one gets the impression that their gender struggles, growth, identity, etc. is not important to the pan who uses this definition.

specifically in regards to "hearts not parts", a very popular quote around the early years of the pan label - this gives the very strong idea that pan people are claiming that only their sexuality involves being attracted to the important parts of someone; their mind, their soul, their identity beyond gender, etc.. this is just... yuck.

just as well, this further pushes the pretty prevalent idea among mogai/inclus that gay, bi, and straight people are driven solely by sexual desire. while the "hearts not parts" phrase is uniquely pansexual in nature, the sentiment is shared by inclus asexual and other people using "how" labels, such as demisexual and other "a-spec" people. this sentiment is considered pretty homophobic, because while the idea seems to be against gay, bi, *and* straight people, it is weaponized frequently in opposition to gay and bi folk, especially lesbians.

"it's just a preference"

preferences are for flavors of ice cream. i highly doubt one is basing their whole identity on the phonetic sounds of "pan" vs. "bi", or a "prettier flag", or what have you. typically, if one dives deeper into what exactly these "preferences" are, they almost all lead back to misconceptions about bi as a label.

differing community

it's no secret that pansexual people have, at an alarming rate, culminated for themselves a unique culture and community. it's also no secret that a lot of this reeks of the era it was born from - 2009-2012 internet culture - but my distaste is my own.

some argue that their preference for the pan label is simply due to this differing community. some... do not argue this, but it's apparent. what either party doesn't consider is this: stating preference for one community, in this situation, is stating a preference to not be included in the other community.

this is why i say that some pan people, while not consciously aware, adhere to this argument. i was one of these people. this is where you'll have to forgive my heavy reliance on personal anecdote, but i believe it applies.

when i id'd as pan, i realized later that a big portion of my preference for this label stemmed from this mystified idea of the bi community. in my head, subconsciously, i viewed bi people as mature but not too mature, sexy, club-going, drug-using, edgy. i thought i couldn't be one of those people because they were too *cool* (these ideas aren't cool in this regard - they're very common biphobic stereotypes). pansexuals, on the other hand, where nerdy, friendly, meme-loving, sex-positive but not promiscuous. so many of the "fandom moms" we all used to admired had pan in their tumblr description, twitter bio, blog header, etc.. i could relate to this! (emphasis on could... i'm a normal human being now)

you can see these internal biases become very apparent when you see pan people insisting that their preference is "valid", or when you try to get them to explain how they're different from bi people at all. this isn't a matter of "one community or another", or even "one community over another", but "one community over the boogeyman of our idea of their community". and it all becomes so silly when you see how self-imposed this is - all these traits are bi culture! you're bi! you are contributing all this to bi culture, and you only need to shed your internalized biphobia and realize this!

fetishization of trans identities

i touched on this in my first point, but i'll go more in depth here. essentially, the idea that there must be a separate identity for those willing to date nb people, and god forbid if you're even more ignorant, trans men and women, is inherently othering and, in many cases, fetishizing of trans identities.

in my experience, the pan person who recognizes that pan is the same as bi, but who claims they are pan due simply to preference, is actually in the minority. for every pan of this sort i've seen, i've seen 20 more who blatantly believe that they must id as pan, since they would date trans and nb people. i believe this is almost directly related to how many cis people id as pan, as well as a mix of trans+nb people who've been fed this narrative and now believe it to be true. those quirky fandom moms i mentioned? all cis, all iding as pan performatively. the label of pan is an act of defiance in their eyes, the ultimate symbol of trans+nb allyship. and it's so, soooo cringey. i'd rather they be honest and id as "chaser" and be done with it.

if you're one of those people, or someone who believes this distinction is valid, hear me when i say this: TRANS PEOPLE DO NOT WANT YOUR SPECIAL TREATMENT! binary trans men and women want to be included in your overall binary men and women categories. trans men are men, trans women are women. attraction to men includes trans men by default, attraction to women, the same. nb people adjacent to these binary genders (demi-man, genderfluid, trans masc, agender+masc presenting, etc.) like to be included in these categories of attraction on an individual basis! there are gay men who date masc nb people, and lesbians who identify lesbian attraction as attraction to non-men, and vice versa. how can you rectify iding with an identity solely to point out your attraction to these otherwise unincluded (by your standards) categories, all in the name of being for these peoples' desires, while also ignoring their pleas to just be included and normalized within *all* attractions? can you say that gay, straight, lesbian, and pan people can all be attracted to trans+nb people, but not bi people? that's silly! so, in your attempt to be more inclusive, you've actually insisted on further othering us.

i'll add more points if/when they're brought up, or if i remember anything else later. i just got back from work and am quite tired, so.. :,)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t be a Gender Identity Gatekeeper

(Keep scrolling if you already know the definitions of basic queer terms. )

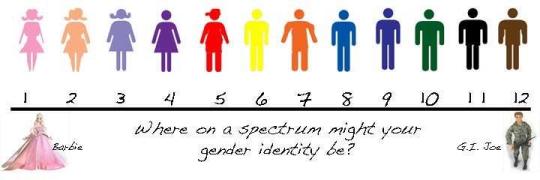

For people who maybe confused I included this handy dandy genderbread person chart. This is a really simple way of explaining gender identity and gender expression, but really it’s more complex than the genderbread person, but it’s a good start.

This is the general consensus on definitions of terms, NOT my opinion and it is NOT a political stance. My existence should not be political. I will make a note of my own thoughts in this post. If I get things wrong please feel free to correct me. Things are being updated all the time by scientists and scholars and as of now this is what I know. The fact that transgender people exist, and gender being a spectrum (like most things) is scientific consensus.

Scientific consensus: Scientific consensus is the collective judgment, position, and opinion of the community of scientists in a particular field of study. Consensus implies general agreement, though not necessarily unanimity.

Transgenderism has to do with the physical brain, not the psychological mind.

Dysphoria: a state of unease or generalized dissatisfaction with life

Dysphoria is a symptom of a physical difference in the brain, and can manifest itself as psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression when it comes to secondary gender characteristics, how the world perceives a person, and how they are treated by society when mind and body are not in alignment. Dysphoria is a symptom, NOT a clinical disorder, and is multilayered.

It is estimated that about 0.005% to 0.014% of people assigned male at birth and 0.002% to 0.003% of people assigned female at birth would be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, based on 2013 diagnostic criteria, though this is considered a modest underestimate.

Trans people have physically different brains than cis people do. So you are either trans or you’re not. You cannot turn trans. You are born that way. You do not choose to be trans, but you do choose whether or not you transition.

Whether or not you decide to transition, and whether or not you suffer from dysphoria, you are trans if you have a trans brain.

(Side note: 🤔 I wonder how many trans brains are out there that don’t feel dysphoria so are there for not symptomatic and they live their lives as a cis person without transitioning.) anyway....

Gender EXPRESSION terms:

Gender expression is how you choose to express your gender within or outside of societal norms.

Terms like androgynous, genderqueer, non-binary, gender non-conforming are about gender expression NOT gender identity. They can coexist with gender identity labels.

(Side note: Anybody can don these labels. If this label were an item of clothing it would be a unisex over shirt. It doesn’t matter if your cis or trans. Most LGBT people fit into this category right of the bat)

Androgynous: partly male and partly female in appearance; of indeterminate sex.