#but now it’s like. you are deliberately ignoring lore to make your theory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

POPPING BOTTLES MATPAT OFF YOUTUBE FINALLY!!!

Maybe the channel will turn into something good, maybe the channel will completely die in 6 months.

i really do hope it turns into something good. because there’s a genuine reason why game theory was so beloved in its beginning and why so many people (myself included) have so much nostalgia towards it. and yeah, not all their old videos were great either, but they weren’t plagiarized. they weren’t directly contradicting canonical points for the sake of being “out there” and “different”. i really do hope the channel(s) can slow down and take its time to focus more on the love of theory crafting instead of the shock value of being different

#muse talk#anon#as much as i hate#i was a fan!! i loved their old stuff!!#i still hold the portal theory fondly#and a lot of their scientific/mathematical stuff too!#but now it’s like. you are deliberately ignoring lore to make your theory#you shouldn’t cherry pick

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

My controversial Milex theory

So, common lore is that Miles has always been this free and easy, liberated rocker, and Alex was the repressed, closeted one, holding Miles back from coming out. But recent events have made me think differently. There was the Miles at church thing, the realisation from Knee Socks that that is possibly about Miles and his religious guilt (the ghost in your room etc), and now the Suki Waterhouse thing. He has deliberately posted her song, congratulating her on her hit. It is an unusual move for him, but there won’t be any speculation about them because she is settled with Robert Pattison and they have recently had a baby. It is like Miles is making an effort to show there is no bad blood between them.

Why? Well I am thinking that maybe he is gearing up to come out, and seeing as Suki was his biggest publicised romance and she was supposed to have left him for Bradley Cooper (who it is rumoured also gay/bi) then Miles is now saying between the lines that it is no big deal what happened between them.

Alex always gets the bad rap because he is the one who has had long term girlfriends, but I think we have to look closer at Miles. He too has been in situations where he was sticking his tongue down the throat of a Page Three Girl or some model, and his lyrics in the early days were full of ‘she’ and ‘girl’ much more than FWN or Humbug. Even his videos always had females in them, just as much as AM’s videos (and let’s not forget, Alex has never fully interacted with a woman in an MV).

Personally, I think from 2008 – 2015 Miles and Alex had a casual thing going, but listening to Alex’s lyrics from this period, I would say that he realised early on that he was in love with Miles, and it was an open secret. See any clip of the Monkeys being interviewed around this time and the other boys pull faces when he talks about Miles. Whereas I think Miles was still convincing himself he could ‘go straight’ if he wanted to. I say this because in between DWYA and CDG we have EYCTE, and twice Alex has made reference to them ‘falling in love’ during this time, and by the end of the tour, Miles looks as lovesick and smitten with Alex as Alex has with him since 2008. Miles could no longer fight his feelings and had to come to terms with his sexuality, but by then he had mucked Alex around too much, and Alex had to go back to being CEO of Arctic Monkeys, so Alex wouldn’t commit to him. Hence you get CDG (but you also get the Ultracheese). This led to their breakdown around 2017 -2018. But instead of what everyone thinks, that La Cigale was the beginning of the end, I think it was the opposite.

By NYE 2018/2019 they are in their local in Bethnal Green, celebrating (Louise is there but Alex is trying to ignore her) and by Change the Show, Miles’ lyrics are no longer gender specific (apart from Caroline) and he sounds more annoyed at Alex rather than full of angst and hurt like CDG.

Then we get to OMB/The Car. OMB is full of songs where Miles is reflecting upon his own behaviour, and on The Car we have Jet Skis and Hello You that hint at their reconciliation.

So in summary, I think Alex’s closet is very public but in their inner circle everyone knew the truth, but Miles’ struggles were far more internal and it took for him to realise he was in love with Alex for him to come to terms with who he really was and he had to become comfortable with that before they had any future.

#i'm not making Miles the bad guy#but i think his internalised homophobia is deeper than we thought#alex turner#miles kane#milex#milex theory

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey man. h. hey man. hey man i hope you know what you just did. i just wrote one essay in the rbs and trust i WILL write another

so like LITERALLY YES I HAVE SEEN PEOPLE WITH MY OWN EYES TYPE THE WORDS TYLER WAS LYING IN I AM CLANCY AND POST IT ON TWITTER DOT COM AND RECEIVE AGREEMENT IN THE REPLIES. im not gonna be messy and post usernames but

out of the 12 replies under this tweet, almost every single one is in agreement. and i have to ask, like genuinely, do any of you people know how storytelling works?

and im so dead serious when i say that. i’ve talked about this to moots, ive talked about this to my irl clikkie friends, ive talked about this to my bsf who doesnt even know the story (yet), id be surprised if i havent posted about it on here yet. and i never post abt it on twt because of how prominent this theory is, and the way people talk about it, i just dont feel it would be a receptive environment. and while i absolutely acknowledge i might be wrong, that doesn’t change the fact that i feel so unwelcome (in this regard) i dont even try. a lot of people openly shit on tyler = clancy truthers, and once again i admit maybe i just don’t know where the joke line is! but regardless of intent this is definitely the outcome, because i cannot be the only one on that godforsaken app.

but my question—why in the every loving fuck would tyler lie to us? yes, he likes to make fun of us, and yes, things can be misleading before they are explained. but why would he lie. concept albums/music videos/other sporadic things are a very hard medium to tell a story through, something tyler openly stated during the clancy livestream while explaining torch’s guiding ability! so when giving us material, LITERALLY WHY WOULD HE LIE ??

sorry for shouting. but people constantly discredit tyler’s ability as a storyteller, as if he has not been writing it for over ten years. i promise he knows the story better than you. i promise. and i also promise when posting a video like this, where he brings the whole clique into the story regardless of their knowledge level, he would not lie. it would be literally balls to the walls batshit insane to do that. he isnt a 12 year old writing a fanfic making it up as he goes (as someone who was one), he is a grown man who has been writing for years and has been writing this specific story for, oh yeah, OVER TEN YEARS. YES, he said they react to us, but that’s more in the way he tells it, he’s not changing the story with how we react. he’s laying it out for us, and people are, at this point, deliberately ignoring it. that’s the only explanation i can fathom.

it goes in tandem with torch’s guiding ability. once again, i acknowledge i am not always great with determining where the jokes start and stop. but things about torch not being real, especially around bandito torch, tick me off to no end. because tyler fully said “bandito torch is real.” not only that, but voldsøy torch being a projection doesn’t mean he wasn’t real, it just means it was different. like he’s still there, and the neds/keons can see him at least, we just don’t know if anyone else can.

tyler talking abt the story and torch’s guiding btw

MOVING ON from how lore clikkie twitter gets on my nerves, though, i have thoughts on what vialism may have been! because of course i do. and courtesy content warning for discussions of death and suicide

so, vialism as a word of course comes from the fact that vial is a container. a vessel, if you will. and as the religion currently stands, committing yourself to it renders you a vessel for the bishops upon achieving glorious gone, aka your death. and as clancy says, “it teaches that self destruction is the only way to paradise.” they use this to feed their power cycle.

so now that we have those concepts established, i think vialism was not all that different in its original form. i think it was a religion meant to celebrate death, and the fact that we are all vessels for something greater. when you die, it’s a glorious gone because whatever message you were carrying has been achieved. it’s not about self destruction, it’s about moving through life with a purpose, and the joy that comes when you have finally reached the end of your journey. it’s sad, but you’re meant to move on and continue being a vessel for your message.

hold on a second! that sounds familiar! that sounds like a certain album relased in 2013, whose songs are easily connected to the story! it almost sounds like this video of tyler talking about the name vessel, even.

i don’t know why im being such a smart aleck. basically yeah i think vialism used to be a religion built around the concepts within vessel, and the bishops twisted it to mean only suicide could get you to the “glorious gone” status.

i want to draw a connection to neon gravestones, as one of the closest looks at the culture within dema we get (especially within the songs)

now you wait just a minute! doesn’t that sound like clancy asking for a healthier view of death—not lingering on it but celebrating the life and its conclusion? and you know…that reminds me of another song…another close look at dema within the music itself…

hmmm…almost like the bishops have twisted what used to be the act of honoring the life and death of a person into minimizing the life and glorifying the death, and now encourage people to ruminate on that so much they never move on with their own life…and leave the people confused and guilty when they feel the pull to continue living…

much to think about!

hi guys im back to be really fucking annoying abt lore again

upon a rewatch of the “i am clancy” video, i caught a line i think people have glossed over. when talking about the creation of sai, he specifically says “they made me entertain the people. lie to them.” and you know what the big message behind scaled and icy was? clancy is dead. he full tells us he was lying. like we already knew it was propaganda, and that the bishops were filtering everything he said, and then he outright says “i lied.” of course, this only holds merit if you believe what he says in this video (no im not bitter people think he’s lying in it. youre crazy)

also, just other thoughts—i think people are way too hung up on the tyclancy debate. besides the fact that i don’t understand why it’s still a debate at all, but the stuff he talks in this video goes so far past that.

first of all, he mentions his friends (“i can feel my friends rolling their eyes”). he has friends dude. i cant fucking get over that. he even laughs a little when he says it too. guys he has real friends besides torch. i think we moved on from that too fast. tell me more about your friends catboy

second of all and more importantly: “i am a citizen of an old city. well, they say it’s old, but there’s just no proof.” this was also hinted at in two of the fpe letters (transcriptions from ciancyisdead on twt)

and clancy also says vialism is a “hijacked religion”

WHY do we not talk about this more often. guys theyre faking a whole history within dema and manipulating a religion to keep the appearance up. we have no idea what vialism used to be before the bishops got ahold of it and began twisting it to fuel their seizing ability. the bishops’ corruption runs so much deeper than just clancy. his importance comes from his status as an exception and escapee, but like, the bishops are doing a lot outside of him. he has a personal connection that is the center of the story, as it should be, but like. there is so much more. why don’t people ever talk about vialism dude it’s so frustrating to only see the same couple of things constantly debated, especially because half of them have already been laid out, people just refuse to believe the information theyre given

okay leaving this here now bc one of my fics updated

#does this even make sense#it does to me but who knows#anyway yeah i have many thoughts. more thoughts honestly#esp on the clique but we aren’t unpacking that#twenty one pilots lore#tyler joseph#clancy#twenty one pilots

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, sorry to bother you 🥺 when was the first hint, in your opinion, that something was wrong with osiris?

You're not bothering me at all! I'd love to discuss it a bit more to mention some stuff I haven't before.

First chronologically would probably be the deliberate framing of the ending of Immolant. He is shown alive after Sagira's death and they mention that Sagira's Light stood above the Pyramid for days. Since this is the last Osiris POV we have, it implies that he stayed in the Hellmouth for ?? days until managing to message for help.

But personally, I wasn't thinking about it until some time midway through Season of the Chosen. Around Chosen, I started noticing minor things that would mildly irritate me about him, like the way he was talking. His tone. The way he kinda goaded Saladin into scheming against the Cabal? But I chalked it up to him being bored in the Tower. Rest under the cut because of length:

Presage got me thinking more. The way he spoke about the Crown of Sorrow, the way he told us about how "The Darkness" and "The Entity" are two separate things (something Osiris never mentioned before). When I first started considering the theory, the first thing that popped to my mind was what he says to Caiatl during Presage when they both hear voices. Osiris says that he heard the following:

The ignorance of my youth. The pain of change. Unproven faith wilted by logic.

I never understood what he meant by that. I mean, it could be a number of things. It's frustratingly vague, more so than Osiris is usually. This isn't too much of a direct evidence because it can be interpreted in multiple ways but it struck me really hard when I first heard about the theory. Because it could be applied to Savathun.

She was also ignorant in her youth, following the words of her father's worm and leading her siblings to the Worm Gods. The pain of change from simple krill into Hive and then further into Hive Gods. Unproven faith (in the Worms and the Darkness) wilted by Sword logic.

This is a huge reach btw and the reason why I don't include it as evidence. It's having a conclusion and then looking for evidence, in a way. But at that point, I decided to look into it more.

I think the first proper direct hints were all the strange encounters various characters had with him and the way he's described as "melting out of the shadows." Noted in the first part of this post. Specifically how Ikora and Saint think they can hardly recognise him. They are the closest to Osiris so they know him best (with Ikora saying Saint specifically knows him best and Saint was utterly confused about him post-Immolant, especially in Boots of the Assembler lore tab).

Once you start thinking about it tho, you can go to any point in any of the three seasons and there will be something that's off. For example, early in Hunt, Crow makes a note that Osiris has been coming to him (secretly?) to teach him about Hive stuff:

Now, again, Osiris knows a lot about the Hive. He participated in the plot to take down Oryx and he knew how to interface with the Dreadnaught in Immolant. So on its own, this isn't much of a proof. But when you look at all the stuff together, it starts being hard to ignore.

But yeah, I think the best proper hints were the way other people reacted to him. People closest to him. I'd also say that both lore tabs of Savathun's POV of being in the City are good hints too, but they don't work as well if you don't already suspect Osiris. Retrofuturist and Ripe. The "this form allows me some dignities" from Retrofuturist is weird, but fits when you apply it to Osiris. And in Ripe, she has to make a random civilian forget what he saw which makes little sense if the civilian just saw a random person. More about Ripe here. We're kinda expected to start piecing things together at this point.

While Hunt and Chosen were somewhat subtle overall and relied more on what we don't have (lore from Osiris' POV), Splicer really didn't fuck around. Most of the stuff he says and does in Splicer is really bizarre, starting with the fact that he seems completely uninterested in exploring the Vex Network, to randomly antagonising Mithrax despite being one of the first people to advocate for Eliksni allies, to "underestimating the Young Wolf," to helping Lakshmi with the Vex portal and then going all out with showing us that cutscene. I legit did not think they would show us something so blatant already.

Something I haven't discussed yet at all is the phrasing of Lakshmi's radio message (1 minute, 46 seconds if the timestamp doesn't work) and how she says Osiris helped her "open a rift."

First, this reminded me of the lore book Empress, lore page New Gods. The lore page is defaced with Savathun's scribbling where she explicitly states she corrupted Umun'Arath and gifted Torobatl to Xivu Arath, "her favourite sister." The page ends with this:

She laughed and laughed and laughed until her mouth began to ooze. Until Caiatl, disgusted, pushed her off the sword with her foot. The body tumbled back onto the green blaze.

[A gift for my favorite sister.]

As the fire consumed the corpse, a gargantuan portal opened in the sky.

A portal opening above the City and flooding it with enemies? Happened before, with the Cabal. This was a more direct intervention by Savathun because she used Umun'Arath's dead body for the portal somehow.

However, this isn't the first time Savathun tricked someone into opening a rift to unleash the Vex. She tricked Crota into cutting open a rift in space and unleashing the Vex into Oryx's throne world.

The portal/rift that let the Vex into the City also unleashed the Taken as well. With Quria dead, Savathun really (presumably) has no way of controlling either of them. It explains the chaotic nature of Override: Last City. And of course, Lakshmi would need help from someone who knows how to manipulate Vex portals AND from Savathun. Savathun using Osiris as her meat puppet is a perfect fit.

#destiny 2#osiris#savathun#lore vibing#more stuff for the evidence pile!!#i'm thinking about this a lot#at this point if we're wrong about this whole thing i am SO INTRIGUED to find out what's happening if not this#like it must be absolutely mind blowing#more so than this is#ask

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

//rp

Before I get into it, I want to state that is EXPLICITLY an analysis of the Characters, and is not intended to touch on how the cc's played them in a meta sense unless specifically stated otherwise.

Also, I just wanna put out there that I started writing this as soon as the streams ended and I LOVED THEM SO MUCH. I had such a good time watching them, and serious kudos to all the cc's for putting on such a good show.

I'm not writing this analysis to critique the way the story is being written, I really, really enjoy it, I just want to put my two cents out there on some of the differing character interpretations going on right now. I think this will come off as critical of the Syndicate, but I'm not trying to tear them down from a writing standpoint, but examine the characters' morality, the narrative direction that the story is going, and express my overall thoughts on both.

NOTE: The original post ended up breaking Tumblr's post editor because it was so goddamn long (i think??? or tumblr just hates this meta specifically.) So there is a part two to this, which I cannot link because it screws with Tumblr's tagging system. Thank you, you garbage website.

-

Tommy.

There is a relatively large section of people who believe that Techno and Phil's characters reactions to Tommy dying (Techno saying “pog” upon hearing that Tommy was beaten to death, and Phil's chuckling and insistence that he wasn't really dead) do not reflect on their characters' moralities.

I HUGELY beg to differ.

Tommy and Techno had a massive falling out. I'm not going to talk about who was 'right or wrong' in this situation because at the end of the day, they both ended up feeling hurt and betrayed by each other.

I think there is a degree of misplaced anger over this reaction and feeling hurt on Tommy's behalf, as he implied that he wanted to reconcile with Technoblade and clearly still cared about him on some level. However, this is audience only knowledge. Techno has no way to know this, and shouldn't be criticized for feeling more or less on same page as he was post-doomsday, seeing as Tommy never got the chance to try and make things better or even just talk to Techno, either by choice or by chance.

That being said.

Techno is the one who, himself said “I would have fought the world for you-” during their screaming match on Doomsday. Techno knows that Tommy went through something deeply traumatic due to Dream during exile, although not the whole of it. Techno is the one who took in the half-dead raccoon boy who had nothing to offer him, and tried to make him an ally.

It's not unreasonable to be shocked, surprised, or concerned that his reaction to a former friend's brutal death at the hands of his abuser was, and I quote, “Tommy's dead? Pog, I hated that guy.”

Yes, Techno feels betrayed by Tommy. But that doesn't mean that the attachment that was clearly there (again, took in the half-dead raccoon boy who had nothing to offer him) turning to spite and mild joy at his death should go without comment because “it makes sense.” It is still shocking. It is still worth examining as a character moment.

This is not meant as a critique on how cc!Techno is playing his character. I am pointing this out to say that I think this reaction was intentionally done to portray c!Techno as a person who has been so blinded by the attacks against him and the hurt he feels that he would revel in a former-friend's brutal murder, which is in my opinion, and I know this is a controversial take, kinda fucked up. (the c!techno part. Playing a messy character is pog.)

Now, none of this inherently makes Techno a villain*. He's allowed to feel however he wants about whoever he wants, and none of that makes him a villain. It does however deal a hit to his morality. It's not... good, to laugh at someone dying to their abuser in a prison. It's something that might make sense for someone in Techno's situation to do, but the fact that it makes sense doesn't mean it's not still a huge dick move.

He (and Phil for that matter) are both fairly emotionally stunted people – they struggle to express themselves well, and often hide their true feelings. It's fair to view this reaction as a form of denial, shoving down any last traces of attachment to Tommy and laughing it off instead, similar to Jack.

However, it reads less like that to me, and more like Techno has already cut Tommy, and by extension all of those residual feelings, out of his life. Which is still a coping mechanism to deal with the pain of being hurt by someone you care about.

But he and Tommy didn't fall out over nothing – Again, I don't want to get into the morality of who was right or wrong on Doomsday, but It's fair say that they both felt hurt, and had such a bad miscommunication by the end of things that it came as a surprise to them both. Even if Techno was 100% morally justified on Doomsday, the fact that he was surprised by Tommy's switching sides should be an indication that he missed something - that he needs to look beyond the surface level.

This coping mechanism is dangerous – it paints Tommy as something a lot worse than he was to Techno, and helps him further ignore the idea that he had any fault for what happened, or to perform any introspection going further.

Once again, this is not a bad writing choice. It's actually really compelling.

((*note: the definition of 'Villain' I am using here is:

1 : a character in a story or play who opposes the hero. 2 : a deliberate scoundrel or criminal.

c!Techno is not currently opposed to a 'hero' character, and he is not AFAIK deliberately being 'villainous' or 'criminal.'

I think it's important to differentiate a character that is acting amorally or immorally, from a character who is being cast narratively as a villain. More on that later.))

Phil is a little more clear cut, but also a little more ambiguous, and... that's right... you know what time it is!

IT'S SBI FAMILY DYNAMICS DISCOURSE TIME! YAAAAAAAY!!!!!!!!!

...no thank you actually.

The SBI family dynamic is so, so fraught, and so argued inside and out and backwards and forwards... I'm tired of it and I don't really have anything to add. I'm just gonna clarify how I personally interpret Phil's relationship to Tommy, and then move on with that assumption in mind.

Tommy seems to view Phil as a father figure, someone who he wants to impress and earn the affection of, as seen when he tries to claim that he was the sole builder of the hotel to him, and also someone who he sees a protective figure, as seen when he calls out to him in the prison, multiple times.

I've seen some people argue that the above lines aren't canon, and are meant as meta jokes about cc!Phil, and.... I disagree? Both are stated during and about lore, extremely heavy lore in the latter case when Phil is one of the first people Tommy calls out for after being resurrected. It reads to me as an intentional character moment on Tommy's part.

Whether or not Phil knows that Tommy views him this way is up for debate. I'd argue that he probably doesn't – Phil doesn't seem to think much of Tommy one way or the other, and only seems to view him as an annoying kid that followed Wilbur around.

As an aside, I have seen some people claim that c!Phil doesn't know c!Tommy at all beyond their canon interactions, but I haven't seen anything from Phil's streams to confirm this as canon? I don't catch all of his streams so it's possible that i've missed this, but it would a huge deal if so and a bit of an outlier within the overall SMP. Almost all of the characters on the SMP come in with their out-of-character dynamics to other streamers somewhat intact. If there is genuinely a clip of Phil saying that his character has not met Tommy before this, please send it to me.

I'm gonna direct anyone else curious about this topic over to @lucemferto's excellent video, link in the source. It goes over the muddled history of the SBI family dynamic in an accessible and informative way.

To summarize: I consider Tommy to view Phil as a father-figure, while Phil does not return the sentiment. That's what we're going with today, watch them canonize Tommy as his biological son tomorrow just to spite me specifically.

So, after all that, does it matter when looking at Phil's reaction to Tommy dying?

Well, not really. Phil's reaction was a lot more... reasonable. That is to say, he completely denied it and therefore did not go through any processing of it. We don't know exactly what he'd think, if he discovered it was true, and there's a good chance that we wont seeing as Tommy has been revived.

He also seemed a surprised by Techno's cold reaction, assuring Ranboo that “he has a heart in there somewhere.” It's just theory at this point, but I do think this suggests that if Tommy was proven dead, Phil probably would have a more emotional reaction.

I do want to take the chance to comment on Phil's overall relationship with Tommy though, and why it matters to his character as a whole, mainly because he canonized a little something today.

Wilbur wrote him letters.

And if you're telling me that Wilbur “Don't call me your brother I'll cry” Soot wouldn't be telling his dad about Tommy – Tommy annoying him, Tommy's stupid cobblestone towers, Tommy sacrificing his discs, Tommy, his vice president and best friend,

Then I have to ask if we're talking about the same guy.

And this is why, even if Phil's first time ever talking to Tommy was after Nov 16th(something that I highly doubt) It still wouldn't make sense for the audience to disregard Phil's more callous interactions with Tommy, such as during Doomsday, and the fact that he hasn't really taken any interest in Tommy or had any urge be active in his life.

Just like L'manberg was Tommy's last connection to Wilbur, Tommy is one of Phil's last connection to Wilbur – he is one of the last remaining things that Wilbur truly cared about, however strained it was at the end.

I think that reading Phil as a character going through a negative arc rather than a positive one is a valid interpretation. I don't think it's the only valid interpretation, but it's one that can and should be discussed by those that want to engage in analyzing the dsmp. Phil, as a character who is failing, who is genuinely doing a disservice to himself, Tommy, or both, is a facet of this character that should be examined, and his non-relationship with Tommy is a good avenue to do so.

TLDR: Techno's reaction to Tommy dying paints him as being blinded by hatred. Phil's reaction less so, but it points to a general disinterest in Tommy's life that ought to be better explored.

In part two, we'll look at the syndicate as an entity, what it's role in the story might be, and, of course...

#Dream smp#Tommyinnit#c!phil critical#c!techno critical#dream smp analysis#lazytext#i tried so SO SO HARD to prevent this from ending up in the main tags#if it slips through the cracks i WILL cry

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

//Because I lack self control and have too much interest in the shadow kids, I asked the LN twitter about a random thought I had on discord yesterday and wanna share it for anyone that isn't in there so I can hear any opinions or just talk about lore.

Ramble incoming

Link to their answer here (has my late theory in it)

Only things I can way with a lot of certainty but not 100% (is anything really ever 100%?) is:

-Nomes are only one (1) remnant of a previous life

-There is possibly some other remnant, as they stated the Nome needs another remnant to exist. This *could* be the shadow(or rather a soul) to exist but it could mean there is still a body (altho kinda weird to take a body but leave the clothes, wouldn't it make more sense if you took the body to feed someone/threw it overboard/whatever the Lady would have done with it and also take the clothes to toss or give to other kids or some other use rather than leave them there?)

-That Nome™ is not RK. Not entirely, maybe not even 50%. It's moreso a collection of his memories and behavior, I theorize, and that's what all Nomes are if they are just echoes of the past

-For that Nome to exist there has to be something left of RK, reverse engineering this the only things he could have left behind were likely his clothes, memories, a physical object he was attached to maybe (like the doll from the first scenes in the Depths?) or possibly the floatsam bottles

Some less certain things:

-Are they directly answering my questions? My main questions I was looking for answers here (even though I write unclear I know I'm sorry) were:

1. Who or what are/were the Shadow Kids?

2. Are Nomes and Shadow Kids related?

3. Is there any connection between the Runaway Kid and the Shadow Kids?

4. Who or what ARE the Shadow Kids connected to besides anything with RK?

-What they answered was about the Nomes and remnants of someone else. Something we have heard before if I'm correct. But the Nomes were only a little portion of what I was asking about, so it could be that they deliberately chose the easier topic of Nomes, or they have more connection than thought, as the other topic was remnants. Are they comparing Nomes to Shadow Kids as a remnant?

-Reverse engineering their answer to my rambles and questions, they were very much targeting the portions of said remnants. Likely especially the comments of what happens to the Thin Man and Lady's bodies after they die compared to the Shadow Kids and their boss fight, and the question of if the Shadow Kids are connected to the Runaway Kid as remnants themselves of him or other Maw children. This could very well provide the information that they are at least remnants of someone

-

Some images here for reference too, I didn't know or forgot but the Shadow Kids do have the same sense of fashion as our beloved RK apparently (photos taken from a first person mod and I don't have the tools to find a model of them). They appear to have at least one model (with the shackle) and at least 3 masks iirc.

I'm gunna be fixating and researching everything about these ignored boss enemies even worse now great but I need some answers and theories man. Any help for resources or your thoughts and theories would be wonderful to hear! If you'll excuse me I'm gunna need to replay the dlc and LN1 again later

#||east:ooc#*hides sk* guess my favorite enemies and protag kid you cant#little nightmares#spoilers and theories

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monday 7: Thunderstorm

[doing this] ~1,2k

Danger averted and monster slayed, Dean and Cas turn towards each other with wide eyes.

Before Cas can open his mouth, Dean points a warning finger at him. "Don't say it!”

"I told you!" Cas growls anyway, making Dean throw up his arms in annoyance. "I told you this was not a simple vengeful spirit, yet did you listen to me?"

And it’s true, Cas had said this hunt was likely to be more complicated than it seemed, but can anyone blame Dean for discarding his manticore theory? He’d always thought those were just stories, and if real after all, long extinct.

His ignorance had led him into the creature’s den without any backup, and had Cas not followed him despite the rising tension between them, he’d likely be half-lion-half-dragon meat by now.

Still, guy doesn’t have to be so haughty about it.

So Dean doesn’t let up. "I know, okay? But all evidence pointed to-"

"Evidence that has more weight than my word?"

"Oh, because your word is law?"

"In this case, maybe it should be."

Dean rolls his eyes. "Maybe you should get off your high horse."

"Maybe you should acknowledge that my experience spans billions of years further than yours and that my judgment rarely fails me when it comes to ancient lore."

"Are you calling me a child?"

"You're certainly acting like one."

“Well, I’m not a child and your not my dictator!” Dean spits, and storms off. He can barely see the path he’s walking on, but it doesn’t stop him from homing in on the exit out of this stupid den like a drowning man chasing air.

At one point he almost stumbles over something, and it’s only for Cas’ sudden appearance beside him that he doesn’t fall. Somehow, it only makes him more furious. He bats Cas’ supporting hand away and resumes sprinting away from him. What is he, a clumsy little damsel?

Outside doesn’t bring the desired relief: As soon as Dean steps out in the open air, he’s assaulted with buckets full of raindrops and he’s soaked to the bone in a manner of seconds.

Startled, Dean freezes right at the mouth of the late manticore’s cave. It’s been like a whole other world in there, full of blood and dirt and ancient monsters that such a simple thing like a change in weather is what finally rattles him.

“Dean-” Cas stops right behind Dean as he takes in the next problem they certainly can’t fight.

Thunder roars somewhere ahead, and it’s so loud, the storm can’t be far away from them.

Frustratingly, Cas seems wholly unbothered by the rain. It seems to make a deliberate detour around Cas’ shape, and he’s as dry as ever, looking to Dean like nothing in this world can touch him.

And nothing can touch him. Not the stuff of ancient legends, and certainly no puny human.

Turning his face towards the mourning sky, Dean lets the drops of rain clear his face of dust and grime. He huffs a laugh. "Are you mad because it rains or does it rain because you're mad?" he says out of nowhere, more to himself than anything else.

Cas looks at him, frustrated with a language he can't translate. "What?"

He wouldn’t be getting that reference, Dean thinks. “Nevermind,” he says dryly and moves to sit down on the ground.

"This is not a good idea, Dean. You'll catch a cold, or worse."

Ignoring Cas’ warning, Dean taps the space beside him. "Come here"

Cas hesitates. Then, after a moment of inner struggle, he steps closer to Dean, slowly, as though afraid Dean might evade his touch again. He doesn’t dare dry Dean yet, but —

"At least let me-" He concentrates, and the thunderstorm gives way to a calm drizzle, a sliver of sunlight reaching through the clouds.

When he turns his attention back to Dean, he finds Dean gaping at him. "So you can control the weather."

"I can't,” Cas corrects. “Nature is a force that bows to no one. I can just offer a nudge, a request that it go easier on us. Fortunately, nature rather seems to like you."

A force in the universe actually being on his side, wouldn’t that be something, Dean thinks.

“I s’ppose that’s ‘cuz of my dashing looks and charming personality,” he says, wiggling his brows for emphasis.

When Cas says nothing in response, Dean sighs, defeated. “Why do we keep doing this?”

“Doing what?”

“This,” Dean gestures helplessly between them. “Fighting. About everything. About nothing. Goddammit, everything turns into a fight between us, these days.”

Cas opens his mouth. Closes it. He begins subconsciously fiddling with the sleeve of his coat. He feels so small, suddenly. Against the logic of physics, his body feels drowned out in the coat, his existence paling in comparison to the world, the universe.

“I wish…,” he tries again, and that’s as far as he comes.

But Dean seems to understand even what Cas doesn’t. “Yeah, me too.”

Cas is not used to wishing for anything, other than for the most imminent mission to succeed. Wishing for himself, however… what an amazing thing to presume.

It’s frustrating, fighting with Dean. But Cas would be lying if he said some part of him doesn’t enjoy it a little bit too. He’s never felt as alive as when Dean yelled at him, when he told him to make a choice, to take the leap.

He’s never felt as alive as when Dean gets all up in his face and pushes and prods until Cas pushes back and they fall into a dance so unlike anything Cas has ever known. Not functional and clean, but passionate and messy and so very very… real.

He would, Cas realizes, always choose the thunderstorm over the quiet.

“I was scared for your life,” Cas says softly. “I’m sorry I overreacted.”

Dean looks down, shakes his head once, and when he turns back to return Cas’ gaze, there’s a grin on his face. “It’s cool,” he says. “I was stupid. Just hate being treated like I can’t handle myself during a hunt.”

Cas’ gaze drops to his hands. “I’m sorry for being patronizing.”

“Told you, Cas, it’s fine,” Dean repeats, and after hesitating briefly, he extends a hand to place it on Cas’ open palm. His hands are smooth and warm despite the chilly air, but it’s not the reason for the sudden warmth that fills Dean from his core. He refuses to look anywhere but straight ahead, giving Cas the opportunity to admire his profile in the mysterious glow of the approaching sunset. His cheeks are a little red, but Cas will politely blame that on the lighting.

“I’m sorry for yelling, I guess,” Dean says lightly, though Cas knows just these few words took a lot out of him.

Cas smiles, a slight uptick of the mouth. “If you ever stop yelling at me, Dean Winchester,” he says. “I know something must be very, very wrong.”

Dean makes a noise of protest, but it’s half-hearted, and when he shoves at Cas companionably, it leaves their shoulders lingering. “Shut up,” he says in a way that has the words carry a whole other meaning. That much Cas has learned about the intricacies of human interaction, at least where this particular human is concerned.

“Look,” Dean says, pointing towards something beyond the crowns of trees. A rainbow has formed across the sky, a blending of red and green and indigo, and sitting shoulder to shoulder, they admire it together in companionable silence.

Yes, Cas thinks. Every thunderstorm with Dean is worth it. If only for what follows.

#SPNStayAtHome#monday 7: thunderstorm#ficlet#spn#destiel#heli tries to write#long post#sorry i didn't research the manticore beyond what it is#just needed a rare dangerous monster#there's a pov shift that wasn't planned ugh#it's bc this started on a scene without context#and when i came back to it suddenly i started with dean's pov#dunno where in their relationship they are or what season#im thinking like 5 or 6#they fight a lot but also are v soft#assholes in love

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

MSA: Winged Arthur AU (part 8)

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7,

Part 9: here

.

Vivi POV 3

“What the?” There is a loud declaration of confusion from Lance. Vivi follows his line of sight to Arthur. Vivi assumes he has just spotted the wings.

“I know. I have no idea how they got there. He collapsed before he could say anything.”

Lance, attention moving between her, the ghost, and Artur, exhales long and hard. Then he angles the gun more towards the ground, ordering, “Keep an eye on that bastard. If it moves, give a yell.”

She nods, stepping forward, allowing Lance inch around her and crouch next to Arthur. He needs to do a bit of manoeuvring to avoid stepping on Arthur’s mess of feathers, but he manages it in his grumpy Lance fashion.

While Lance checks on Arthur, she once again makes eye contact with the ghost. Now hovering closer to the entrance, near a beat-up semi-trailer – where had that come from? – the ghost is anxiously clenching and unclenching its fists. Purple eyes are tracking their movements with a disturbing intensity. Creepy. Doubly so now ‘Lewis’ looks like a flaming skeleton again. She glares and receives that pitiful expression. Thankfully, with both her and Lance there, the ghost has decided to keep its distance. Vivi would rather it go away and return to its middle-of-nowhere-mansion, but it appears she’ll have to settle for whatever this was.

“He’s okay, I think, apart from the wings anyway. Too dark out here to see much besides feathers. I want to move him inside ta get a better look.” Lance leans back, muttering under his breath, “Also, it’s gotten mighty cold all of a sudden.”

Vivi nods again, relieved to have confirmation on Arthur’s wellbeing. She’s not really feeling the cold but going inside seems like a good a course of action as any.

“What happened to that tree creature?” She asks while Lance goes about trying to pick Arthur up.

“Gone, ran off into the desert with the giant fox.”

“That’s good…I think?” Vivi can’t help the twinge of worry for her fake dog who had been bleeding heavily last she’d seen. Mystery, who had been injured protecting her. Secret or no secret, she feels responsible.

“I got in a few good shots on the tree before they went outta range.” Lance continues to speak, before narrowing his eyes at ghost-Lewis, “What’s that things deal?”

“It’s a wraith,” She states, ignoring the way ‘Lewis’ wilts, flinching back, “They’re dangerous. It’s probably best we keep an eye on it.” Sure, ghost-Lewis seems relatively fine now but she knows that calm is a facade hiding a whole lot of angry fire.

“Right.” Lance doesn’t question her, focusing instead on carrying Arthur which looks difficult due to how the wings flop about. Vivi wants to help but doesn’t like the idea of taking her attention off the ghost for any length of time. Luckily, after a little fussing and several swear words, Lance manages to sling Arthur over his back, so it looks like he’s wearing a very feathery coat. He shuffles his way to the front door. The trip takes an unreasonably long time, considering the door is only a few feet away. Vivi tracks their progress, on edge and anxious.

There is some difficulty fitting Arthur through the screen door, forcing Vivi to turn and help arrange the wings in a way that will allow them past the frame. Once done, she about-faces to find the ghost has drifted closer, appearing hopeful now neither her or Lance are acting outwardly aggressive.

“No,” She says, brandishing her bat again. “You stay out here.”

“What,” The ghost, stunned, freezes in place, staring like she’s grown an extra head. Vivi steps forward, blocking the entrance.

“You’re not welcome inside this home,” She reiterates. “Uncle Lance. Tell ‘Lewis’ he’s not welcome inside.”

Lance, now just through the doorway, stumbles almost dropping Arthur, giving an abrupt, “Huh?”

“First rule of supernatural anything. They have to be invited into homes.”

“Not what…” Lance shakes his head, “What do yeh mean by ‘Lewis.’”

Okay, so Lance knows who Lewis is��Perfect. That doesn’t change anything aside from confirming her theory that she had known this ghost at some point. She waves pointedly, giving Lance as serious an expression as she can manage.

Lance’s gaze snaps to the ghost in befuddlement. “Hold up. Yeh not tellin me that that, right there, is Lewis?”

“That’s what he said his name was. Right before he tried to burn me and Arthur,” She states.

“I would never hurt you…I swear. It’s just…Arthur…he’s done something. I don’t know...there’s a lot I… you… don’t know. If you would just let me explain,” The ghost pleads again, genuinely remorseful. Talk about your mood swings. Another point in favour of her wraith hypothesis.

“Is that before or after you burn us both to a crisp.” Vivi snaps back.

Lance side-eyes her seriously. Then he examines the ghost, expression hardening.

“Hurt my nephew and yeh ain’t welcome here. Simple as that,” He grunts and turns, heaving Arthur with him.

“No! You can’t. I’m telling the truth!” The ghost reaches out, fire guttering and flickering to his more human form. He sounds desperate. With one shaking arm, he grasps towards her, “Please.”

Vivi glowers and deliberately slams the door in the, now human, face. For a second, she doesn’t move, waiting to see if ‘Lewis’ is going force his way in. There is only a loud cry of frustration, more sad and mournful than angry. Back against the door, Vivi exhales hard. Why does her chest hurt like it’s full of breaking glass? She runs a hand along her collar bone trying to massage the ache away. It’s useless, the pain isn’t physical. An inhale, and she pushes herself off the door.

When she enters the combined living-dining space, Lance has already dragged Arthur to the couch and is in process of wrestling him into a comfortable position. He’s doing his best to work around the copious number of feathers but is struggling to find success. Vivi rushes forward to help, glad for the distraction. They end up lying Arthur down on his stomach so the wings are draped over the couch’s backrest and spill onto the carpeted floor.

“That true? The stuff about welcoming in supernatural creatures?” Lance grunts, while he checks Arthur’s pulse and breathing, running a hand over Arthur’s head and the rest of his limbs, searching for breaks or other injuries.

“I don’t know,” She sighs, straightening, “There’s a lot of lore spanning multiple mythologies, and it crops up a lot in older superstitions. It's more of an educated guess.”

A thoughtful hum.

“Suppose it’s better than nothin. Those myths happen ta mention anything like this?” Lance is now repositioning the wings to look more natural while muttering, “Don’t know nothin about birds. Do these look like they’re sittin right?”

“No myths that I can think of off the top of my head. I mean there are a few where people turn into birds. Not that I think that Arthur is turning into a bird,” Vivi hastens to clarify when Lance gives her an expression of acute alarm. She shuffles nearer, pointing at Arthur, “I think those are flight feathers. They’re definitely not supposed to be bent like that.”

They spent a few seconds straightening the plumages in soft silence.

“There are a bunch of mythical humanoid creatures that have wings and such. I don’t know…maybe you’re related?" Vivi breaks the quiet and is met with a blank expression. “Do you have any relatives who mysteriously vanished for a few years then rocked up pregnant or with an unknown baby? Was anyone adopted into the family? Like, did someone find a child abandoned on the steps to your house and decided to keep it? Any sudden changes in a family member’s personality like they’d been mysteriously replaced?”

“What are yeh on about?”

“The most common reason why humans’ manifest supernatural traits is usually bloodline related. Someone somewhere had a fling with something not quite human,” Vivi elaborates to which Lance frowns, obviously thinking.

“There’s nothin like that that I can think of. But, don’t get along with the bastards, so who the hell knows.”

“Oh, that’s a shame. I guess I can jump online and look into it.” She looks back to Arthur. “Maybe later...”

Carefully, she reaches out from where she is crouched to smooth out a few more feathers which are twisted at odd-looking angles. They feel real, growing from between Arthur’s shoulder blades and extending into smaller downier feathers a little along his back. His shirt has ripped from where the appendages had grown in. No sign of that golden light from earlier.

“Who’s Lewis.” She asks, the question coming suddenly. The response is particular. A huff of air followed by tired and drawn eyes. Lance appears almost haunted.

“Humph. Ain’t that a question and a half,” He stands, glancing towards the broken windows. From this angle, they can just make out the back end of the semi-trailer but said ghost is out of view.

“I know him, right? This Lewis person?” Vivi prods.

“Yeah. Yeh know him.”

Lance turns, calculating, “Suppose I could tell yeh more, seeing as ya seem to be retainin the name ‘Lewis’ well enough.”

“Wh...?”

“But not before I get a drink and yeh see to any of ya own injuries. Arthur’s fine enough, but yeh look dead on ya feet."

What did Lance mean by ‘retaining the name?’ Was this linked to her memory gaps? Probably.

“I’m fine. I mean, I wasn’t fine. I got stabbed here,” She rubs her shoulder, “but, Arthur kind of took care of it.”

Lance peers at her shoulder. There’s a lot of dried blood but no sign of the injury it came from.

“Arthur? He did what now?”

“Healing magic. It’s what knocked him out. He just, I don’t know, healed everything. I actually feel great, like I’m on some crazy energy drink. Ah… Sorry.”

Lance snorts, rubbing his eyes, “Don’t apologise. That boy wouldn’t know self-preservation if it hit him over the head. If you’re sure ya ain’t injured any, then how about yeh keep an eye on the kid while I get us something to drink. Then I’ll tell yeh what I know of Lewis.”

Vivi relaxes a little and nods.

“What can I get yeh?” Lance pauses in the doorway.

“Uh…Tea I guess? Herbal if you have it.”

Lance disappears and she hears things being moved around in the kitchen. Vivi settles down into a more comfortable position on the ground next to Arthur, continuing to smooth the feathers. So, she was right, ghost-Lewis fit somewhere into the swiss-cheese that was her memory of the last several years.

.

Note: Okay, so do people want to read a ‘Lance explains Lewis to Vivi’ conversation (if so, then whose POV do you want it in). Or do people want me to skip to Arthur waking up. I’m leaning more towards skipping atm but if there’s interest I’ll probably write that scene first.

Part 9: here

#MSA#mystery skulls animated#fanfiction#fanfic#Vivi Yukino#lance kingsmen#Lewis pepper#winged arthur#ghost lewis#supportive vivi#lance and vivi have a small chat#lewis angst

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

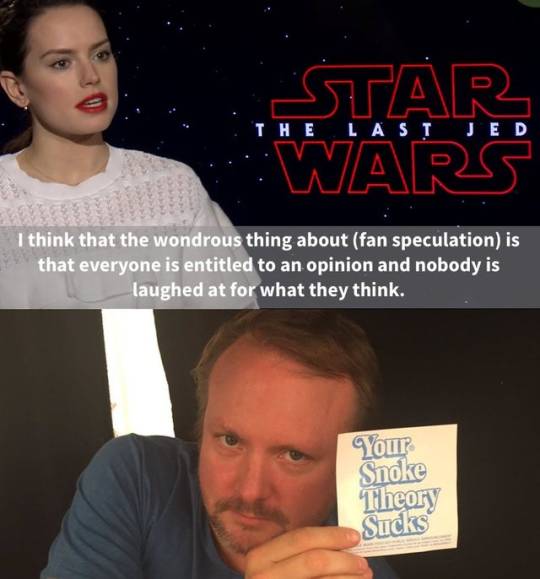

Ways they could’ve handled Supreme Leader Snoke in the Last Jedi and what they did instead

My other Sequel trilogy wasted potential posts

Rey

Finn

Poe

Rose

Luke

Han

Leia

Kylo Ren

Captain Phasma

Hux

List of ways they could’ve handled Snoke in TLJ

Show Snoke completing Kylo Ren’s training. SHow Snoke sending Kylo to Mustafar, Dathomir, Malachor and Moraband

Have Snoke give Kylo Ren one final test, killing his mother General Organa

Order Kylo Ren and the Knights Of Ren to Ach-To to kill Luke Skywalker and bring Rey to him

Show Snoke using Battle Meditation against The Resistance, while Leia uses BM against Snoke. Leia’s will against Snoke’s might over Ach-To, while Snoke is trying to kill Luke, Leia is trying to save her brother.

Make Snoke Darth Plagueis It makes sense and ties the three trilogies together. Darth Plagueis was a powerful Sith Lord who could influence the midichlorians to create life and also save others from dying. He taught everything he knew to his apprentice, Sheev Palpatine (aka Darth Sidious), but he eventually lost his power and young Palpatine killed him in his sleep. How could Plagueis not foresee his own demise at the hands of his ambitious apprentice? Why did Plagueis suddenly “lose his power”? The truth is, he didn’t lose his power and he knew Sheev planned to kill him. It was part of the plan. By dying, I believe Darth Plagueis was able to transmit himself into Sheev and assume control of his body, almost like an infectious disease. Ever notice his name? Darth Plagueis. Plague, as in an infectious disease. Darth Plagueis unlocked the secret to immortality by moving from one body to the next, continuing his lifespan through multiple hosts over countless years. Ever wonder why Palpatine was so obsessed with training a powerful young apprentice? Surely he knew that one day the apprentice would want to overthrow him, so why train his own murderer? In Return of the Jedi, Emperor Palpatine continually provokes Luke to strike him down. Why would Palpatine want to be killed if the goal is longevity? Because Emperor Palpatine was assumed by Darth Plagueis and, through his death, he would then be able to transmit himself into a new host body. He wasn’t just looking for an apprentice, he was looking for a new body since Palpatine’s body was growing old. Luke Skywalker was meant to be the next host body for Darth Plagueis. But unfortunately for Plagueis, Darth Vader had a change of heart and defeated the Emperor. Snoke was Plagueis. It’s the only way to make things work. StarWars.com describes Snoke as a seeker of arcane and ancient lore, and the Last Jedi Visual Dictionary shows that he is a collector of rare memorabilia. At some point, Snoke must have found the wreckage of the Death Star on the forest moon Endor, and was infected by Darth Plagueis when he came upon the corpse of Palpatine. Did you ever wonder why Snoke thought it was so important to complete Kylo Ren’s training? It’s because Snoke was Darth Plagueis and he was training his next host body. Plagueis didn’t have a choice but to infect a really old political influencer like Snoke. Kylo was being groomed to become the next host body. Remember the infamous(ly terrible) scene in The Last Jedi where Snoke is “predicting” how Kylo Ren will kill Rey? Wasn’t it a little too obvious? Wouldn’t Snoke have been able to foresee Kylo’s treachery? See through his conflict? It’s because he wasn’t predicting Rey’s death, he predicted his own. He knew Kylo would kill him. He deliberately bullied and provoked Kylo in order to stir his anger into hatred to further fuel his dark side and lead him to completing his training. So let’s say Kylo puts on his ring for his official coronation as Supreme Leader and Plagueis take’s full possession of Kylo Ren, Plagueis had an apprentice who has fully cemented himself into the dark side and now a new and more powerful body. Darth Plagueis has everything he needs to way waste to the Resistance and the final destruction of the Jedi.

What they chose to do with Snoke instead

Snoke died pointlessly without doing anything with him. Supreme Leader Snoke is wasted and there is no reason to care now that the villain you’ve been building your trilogy around is dead. Snoke’s death was too soon. Snoke is a dark side user. Calm and collected. Old enough to see the rise and fall of the empire. He takes no risks and does what it takes to win. He was different from Palpatine and I dare say he even had potential to rival Kreia. He was a mastermind and did not allow himself to be a slave to the dark side. He did not want his apprentice to die like the Sith masters of old. He did not want to keep power until his dying breath. Snoke was not the average Sith Lord, he was different. He was respectful, he was very powerful, and watching his scenes, even when faced with failure, he remained calm and collected because he was playing the long game and was not a slave to the Darkside like the Sith. He was invested in turning Kylo Ren into Vader’s heir and even has a ring from the catacombs of Vader’s castle. Snoke was so interesting, so many unanswered questions and this well thought out villain. And then TLJ turned him into a dumbed down Palpatine rip off. The claim that Snoke and his backstory is not important is dumb, considering that we know nothing on why this war is even happening or even why The First Order is doing ANYTHING! We want to know who Snoke is because we want to know how this random evil guy was able to destroy the lives of the entire original trio, corrupted Ben Solo and override the happy ending the entire original trilogy and prequels were fighting for. The struggles of the prequels, the clone wars, rebels, original trilogy, all of these stories and struggles were undone because of Snoke, so of course we have questions. Why do the remnants of the Empire follow Snoke and where did he come from? Not wanting to know the motivation of the villains is just plain ignorant. They completely wasted Snoke. Snoke is a power from the unknown regions. He was SO powerful that Palpatine sensed him, Palpatine was so focused and invested in Jakku in hopes of getting closer to the Unknown regions and he wanted to meet what he believed was the source of the dark side of the force. And they just kill him off so easy? Now there is no reason to care. Kylo Ren is not an intimidating villain and it’s pretty obvious he’s turning to the light in Episode IX. Hux is a bumbling incompetent fool and I’m pretty sure they already confirmed he will be more comedic in Episode IX instead of being a threat. There is a villain problem for the Sequel Trilogy. There is no menace in The First Order anymore and I really feel there is no reason to care.

Pointlessly tried to kill Rey instead of trying to turn her

“Your Snoke theory sucks” card is patronizing and insulting. God fucking forbid your audience is fucking invested in the story. God forbid we actually care about learning about the big bad of the sequel trilogy. God forbid we put more thought into Snoke than you did. “Your Snoke theory sucks” no Rian, your Snoke card sucks, your inability to do ANYTHING with Snoke sucks and talking down to us for caring about the direction of the big bad and killing him for no reason sucks. You arrogant piece of fucking shit.

Because Snoke was killed, they copped out and lied out their asses that it was always the plan to bring back Palpatine….bullshit. “oh but wait Snoke was a host body for Palpatine” BULLFUCKINGSHIT. Not originally. Snoke was someone who was supposed to be the darkness Palpatine was trying to get closer. Snoke was the man who destroyed 30 years of peace. He could’ve been anyone, hell even Darth Plagueis. But no, why create interesting characters when you can bring Palpatine back because it’s obvious you have no original ideas.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

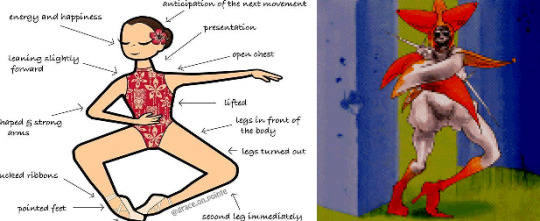

WILD ARMS 2 - Raline Observatory

The Raline Observatory is a neat set piece, albeit one riddled with issues in English. It distracts us with side characters, but actually sets up a pretty core feature of the world that will come back much later in conjunction with the Live Reflectors (which are about to become defunct once we finish this quest and unlock our flying ship) The name however is yet another mistransliteration from the Japanese for “Ley Line.”

Ley Lines came from the observations of one Alfred Watkins, an amateur archaeologist/explorer of the 1920s (as was not terribly uncommon at the time) who made note of the arrangement of major historical landmarks in straight lines across the British country side, from which he questioned the meaning, cause, or function. In the 1960s this work was incorporated along side Chinese fengshui to theorize that a kind of natural flow of energies across the Earth existed, and that spiritually attuned cultures all across history had been drawn to places where such streams of energy intersected, either by divination or by the consequence of ideal circumstances for settlement or ritual structures stemming from said concentrated energies.

Here, it those theories are applied rather literally, and will be revisited more explicitly at a later point in the story. Not coincidentally, this dungeon is located on a string of volcanic not-quite-islands, volcanoes being a rather on the nose example of a point at which energy has built up and been released from the Earth, literal energy obviously but in many belief systems spiritual energy as well. Oddly there aren’t actually any apparent Ley Lines on the Filgaia map; the dungeons are all pretty evenly distributed. The only semblance of patterns* are that various locations that come in 4s are deliberately scattered across 4 quadrants, but that’s less meaningful and more just practical when you don’t want your game’s marathon of dungeons to take place right next to each other.

*(The ones I’ve marked here are the 4 Live Reactors: red, the 4 Diablo Pillars: Blue, and the 4 Ray Points: Green. Perhaps the only real deliberate design here is that the finale dungeon which is tied by lore to the Raypoints, is located right in between the 4 of them; the intersection if you draw lines between opposite points. On this note: the Raypoint dungeons may also be a mistransliteration, meant to be “Ley Points.”)

Anyway we get into this neat abandoned lab setting and immediately have a boss thrown at us.

I think I’ve mentioned both the Kobold, and accidentally the Salamandra, now but among those iconic elemental monsters is also the Undine; Generally portrayed as a beautiful humanoid water nymph. The boss monster, Undines (I don’t know why there’s an “s”, the Japanese even reads ウンディーネ:u-n’-di-ne) is very much not. Actually, given the circumstances I’d almost assume this was some kind of mistransliteration, but the boss card even says “Elemental Spirit,” so what else could it be other than a water spirit? (although when I looked over the epithet in Japanese the phrase is 素体 精霊獣, so what they translated as “Elemental” actually means something more in line with “base form” as in a chemical element, not an alchemical one.) Also of note are its moves: Hookey Bust, Intafada, Reject all Fools, and Shocking Guinea.

We’ll start with Shocking Guinea, as it might be the most straight forward; it alludes to Undines being a manufactured monster, and presumably kind of a lab experiment. It has turned on its creators so perhaps it was inhumanely experimented on until it lashed out? This move is also perhaps the outlier in the set. Intafada I can only assume refers here to the literal meaning of “shaking” or a small tremor and not the Palestinian-Israeli conflict in Gaza in the early 90s... Ignoring the bizarre language choice for that, the move Hookey Bust is a little confusing but suggests one of two things to me; either being caught playing hooky, or rolling a losing number in a game of dice. The former fits with the idea of an escaped experiment, but the latter along with Intafada and the general jester look of Undines seems to suggest shaking and rolling dice? That in some vague sense seems to match with the Reject all Fools, if it means Fool like a court jester.

Okay you know what, I gave the translators too much credit. The moment I started digging things got all kinds of muddled. The move Reject All Fools in Japanese is 理解できないモノは拒絶: “[I] reject things [I] don’t understand.” I take it the translators interpreted 理解できない モノ as “things/people that can not understand” i.e. “Fools,” but it might also be, “things/people that cannot be understood.” I make the distinction because I think it has to do with ghost stories and belief in the supernatural, although what “supernatural” would really mean in a fantasy setting isn’t super clear...

The move Hookey Bust is 学校の怖い胸像: “Scary Bust of School” as in a scary sculpture found in a school, which I’m pretty certain is a reference to the trope of Japanese middle or high schools having a kind of local hauntings where some kind of ghost turns out to be the anatomical model in the science lab or the nurse’s office. It ties into the science lab/experiment theme going on all throughout here. Spooky science lab also explains the “shiver”/”shake”/”tremor” we get from Intafada.

Speaking of terrible translations, the baffling Lilly Pad monster appears here, a bizarre imp with a little sword and cape, and boobs on its head??? The katakana here is I believe meant to be a transliteration of Lilliput, as in Lilliputians from Jonathan Swift’s novel, Gulliver’s Travels. The actual design doesn’t make much more sense in light of that, as they aren’t especially tiny, but at least the basic idea gets across, as opposed to the entirely nonsensical Lilly Pad. I’m not sure they add to the theme going on exactly, but the visual aesthetic of a tiny or shrunken person does resonate with some classic mad science lab cliches.

And we also have the Jelly Blob, which is just a staple of RPGs by this point. Technically speaking I think the origin is, again, Dungeons and Dragons, with he Gelatinous Cube and Ooze monsters, and in turn any number of variants on the both as well as the off shoot Slime family of monsters. Again, very in line with the science experiment vibes.

The one thing that presents a tiny hiccup in this is the Pas de Chat; in Japanese simply named Laughing Haunt. It might be a stretch, but I think it’s just another reference to school hauntings, like the Hookey Bust reference. It’s the only way I can think to fit this into the overarching themes of the dungeon. The “English” name, Pas de Chat, is a ballet term referring to a jump in which the legs are brought up toward the opposite knee in quick sequence before landing. It is French for “Step of the Cat.”

I have no idea why it looks the way it does, but it does display some interesting animations with leaps and twirls that is understandably evocative of dancers. It also fights with a pair of stiletto daggers.

I kind of neglected to mention, but throughout this whole dungeon we’ve been followed by the wacky comedy relief duo, Liz and Ard. (Toka and Ge in Japanese: You get one guess as to what the word “Tokage” translates to.) As we reach the end of the dungeon they of course spring on us that they too are after the rare Germatron mineral, and that they are apparently Odessa’s free lance monster engineers. The two jump us with a second boss fight where the two showcase a host of battle tactics about as wacky as everything else we’ve put up with from them thus far:

Liz, the self-styled lead researcher of the duo can throw concoctions to ail the team, but that also hit himself and his assistant, Ard. Meanwhile Ard is a tank and a powerhouse, even as the inevitable Poison ailment from Liz’s attacks chips away at his HP. But to add to it, his strongest attack deals huge recoil damage to himself trading off for yet more offensive power. If you focus your attacks on Liz and heal as needed, Ard will likely kill himself even before Liz falls. An appropriate end to the mad science theme of the dungeon all around. And naturally, we’ll be seeing more of the lizard duo as the game goes on.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

live blogging but it’s all one post and not actually live at all. this one is really long open at your own peril.

This has to be one of my favorite cutscenes in the game... I skipped most of the cutscenes in this questline with “Tsuyu” and whatever else went on because I don’t care for it, aside from some funny Asahi bits. And this cutscene is the KING of funny Asahi scenes, him just getting straight up murdered. It’s even funnier the second time around because now I realize... he was never actually acknowledged by Zenos. That was Elidibus controlling his body, simply using Asahi’s devotion for his own devices. And I realize now that Elidibus was trying to back up Emet-Selch’s own carefully laid plans, which... is something to keep in mind for later. I can’t wait to see more of Fandaniel later I love his/Asahi’s voice actor. And I know it’s fairly negative in this case but I can’t help but enjoy the campy villains...

And now I can finally stop skipping cutscenes! I realize I just now skipped the part where Alphinaud set out on his doomed journey to Garlemald, but... man I didn’t want to hear Gosetsu cry about Tsuyu I just hate that plot point so much. They really shoulda just let them die.

Oh my god I forgot that Gosetsu is bald now. I know it’s like a tradition thing and serious and everything but. Hhhh he looks so silly without it... Doesn’t help that it lets you see the outlines of all the polygons comprising his head...

Oh man I appear to have gotten events swapped around. Is it now that we see that energy source on the Azim Steppe? We’re about to go and put up that barrier in the Brume, which I’m pretty sure i thought came after ShB for whatever reason. I think I’ve mentioned it in a previous post... though that one I also think I deleted for an unrelated reason, I think because I was tired and got some details wrong and in my frustration and exhaustion threw the whole thing out. I’ll have to write down those particular thoughts again, after I see whatever it is that’s about to happen.

Oh man. i wonder if Hien doesn’t realize that Y’shtola is blind. They get to the Azim Steppe and he’s immediately like “Let me show you my favorite spot where you can see the pretty fields and sky :)” and she returns with “Yeah yeha okay let’s get on with what we came here to do”. Very funny. Actually Hien and Y’shtola are in general very funny together I like seeing him react to her talking to him like he’s an idiot.

So, the legend goes that a “wayfaring soul” came to the Steppe and received a sliver of Nhaama’s power in the form of a shard, and used it to cleft the earth and raise it to the heavens to avert calamity, then made an offering of blood. The sliver of power is Allagan technology, which was used to raise Azys Lla and create Dalamud. The dialogue has been very particular about referring to the person in this story as “wayfaring soul” and not shorter synonyms like “traveler”, which i think is probably deliberate? Especially with this now being the lead-up to ShB.

I guess now would be a good time to re-write some of my thoughts about the Steppe. It is not an original theory that Azim the god and Azem the ancient are related if not one in the same. They are both light, and related to travel. The WoL is expressly referred to as a traveler by Cirina’s grandmother, and iirc Azem is as well. Azim descended from the heavens to walk amongst his children, who are all nomadic. If they do have a relation, then the people of the Azim Steppe might be thought of as Azem’s people. I say this because I’ve been wondering why the Empire hasn’t touched the Azim Steppe, the real reason. The Xaela would make incredibly useful conscripts, and could be easily trounced by a suitably large magitek army during any one of their squabbles, or I’m sure the Empire could destabilize them in any other way. And that isn’t even to mention the large energy source hidden away in its cliffs, which have to be giving off some kind of signal. I wonder if the Empire ignoring the Steppe has anything to do with Solus and his sentiment for Azem.

I suppose I should actually get on with re-seeing this part, then.

God. I love y’shtola the bit with Magnai is so good. The voice acting. He sounds so hurt with his “Little...?”. “Look into my eyes” She’s blind you absolute dumbass.

Alright. Well. I didn’t actually gleam anything new. We’re about to go into the meeting sequence and. God. This is another one of my favorite cutscenes in the game. the visual effect used to represent the WoL’s soul being torn from their body is so cool... I wonder which outfit I should wear? I’ve changed all of them I think since uploading screenshots last. AST is cute and what I’ve been using for the last few quests to soak what little exp I can, but... this is a bit too serious for a cute healer in a skirt and glasses, plus the collar on the shirt would cover his face in some of the shots... DRG it is again then, I guess. It has sort of taken over as my primary class. I enjoy playing it more than BRD :\

“Let us hope that the coming meeting passes more peacably than the last such gathering in ala Mhigo” jfc Y’shtola. Hhhhhooooo here we go!!!!!!! Hhhhh I love Alisaie I remember this was the part that solidified her as precious little sister numero uno.... god... the scene where she gets taken away I’m already nearly tearing up I love Shadowbringers man holy shit.

Raha you dumbass!!!!! Endangering everyone like that. Literally takes five tries before he gets it right, and trying to explain everything while the WoL can’t rightly hear. I know he’s desperate but goddamn dude. Just. God. I’m so excited. I’m excited to see Urianger get to be an actual character again. I’m excited for the Scions to actually care about each other and especially the WoL. Also to see Doran grapple with these troubles as Secret did, finally finally learning why the hell he’s here, what Secret is and what he is, and... coming to terms with it. He was excited when it first happened, before his memory was sapped, mostly a product of being fused with Secret for so long without a will of his own, but... after experiencing all this, seeing these people as his friends. Learning to accept his place in the story much more easily than Secret...

There’s a reason I’ve kept the title “The Last Resort” on him. It’s for my own purposes. Secret has still not accepted that she as a person, though not her soul was created for the sole purpose of being a hero. If she can’t accept this in time... she might resort to letting Doran take the reins. Forfeiting her personhood altogether. This path would rely on unofficial lore about Fantasia, about how it warps reality to make it so that you were always this race or that... I might actually do it, too. I’ve done more things right with Doran, and I have friends on this server. I... suppose Secret would take Doran’s place in my personal narrative then. Which. Feels bad. Like a disservice to Secret, though... I suppose it doesn’t have to be. At this point Doran is still no less relevant to her. Secret will have simply gotten literally washed away with her memories.

I’m uh. Starting to think I might be too attached to Secret. The thought of having her not be my main character, of neglecting her in any way, of having to make this choice is. Making me genuinely emotional... though I suppose I’ve seen enough people on here talk about how they cry about ocs and whatnot.

Anyhow. I think I might change Doran’s hairstyle for Shadowbringers. might make it longer. It seems only appropriate, it having been so long... and something more elegant would be fitting. Maybe I’ll finally find and settle on an AST glam that is suitably pretty. I adore my current one for how cute it is but it doesn’t exactly fit ShB’s vibes.

Oh wait back to serious stuff. It’s funny that Lyse didn’t get called. G’raha explained it as the people closest to the WoL were called, and... for even Urianger to be called and not Lyse. It has funny implications.

MAN....... WHY does this game put Alisaie through so much :(((((((( Endwalker had BETTER give her and Alphinaud some damn good development like they implied. LET THE WoL BE THEIR OLDER SIBLING OR SOMETHING...... The WoL and Alphinaud were so good together during HW, and then them and Alisaie in this sequence and a few other scenes before now and during ShB but... it just doesn’t feel like it’s there during ShB, not with all the other adult characters around.

Granted I do this with every kid in this game. I saw Myste and even before I knew what their deal was it was just

this plays in my head every single time i see a kid. Let me adopt Unukalhai. Game. Game I am demanding now let the WoL care about others. That poor kid has just been sitting in the Solar for two entire expansions then some, and not even as a result of being a necessary quest npc stuck in a time bubble like Urianger’s double in the Waking Sands like he’s aware of what’s going on. I... actually imagine he might be relevant in Endwalker. Reaper comes with your very own voidsent, which means the void will be relevant again which might mean Unukalhai will be relevant!!! At the very least to the Reaper questline, if it has one.

Continuing the story again. Actually you know what LET THE WOL HUG THEIR FUCKING FRIENDS!!! It wouldn’t take THAT long to set it up for each different race which I assume is what keeps them from having the WoL physically interacting with much of anything but it would be SO GOOD!!! IT WOULD BE WORTH IT!!! I wanna give Alisaie a hug she’s suffering so much :(