#chinese railroad workers

Note

unfortunately I have been having the same struggle wrt westerns (the few books I've found that touch well on the actual variance of culture and such have not clicked at all in strength of plot :/ ) but if you're really searching for the Vibe (and yes this is a real stretch) I do recommend what can be had of the lobbyists' in-progress musical 'golden mountain'. there are six songs from it out currently and I do think they get at what you're asking for, or at least they do for me.

The famous 1869 photograph of the Golden Spike ceremony — Andrew J. Russell’s “East and West Shaking Hands at Laying of Last Rail,” at Promontory Summit in Utah — focused sharply on white people as the builders of the railroad. You can’t discern any Chinese workers in the glassplate exposure. But some 20,000 Chinese immigrants were key to the building of the rails, which essentially laid the foundation for a modern United States of America.

Ooh this does look promising! It gets into what I was talking about with stories from the Wild West that are actually based in its diverse reality and are super interesting. I'll go take a look at it, thanks!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Also I feel like if you were going to accuse me of anti-asian racism for writing sex work into avatar fic, the fact I made up an in-universe jazz band called Yoshiwara's Children or had Jin sarcastically joke that she's in the situation she's in because she ran away from the upper ring to escape the inevitability of becoming a royal concubine instead of the vagueness of "making earth kingdom characters sex workers" which i'll be honest, i'm still not entirely sure if they mean headcanons for Jet and Jin or my own goddamn oc's, and yet.

Also that anon failed to mention my au where Yue and Hahn survive and marry and become wife exchange partners with Sokka and Suki and Sokka and Yue have tender, intimate quality time while Hahn comes to terms with the fact he likes getting beaten and roped up and it amuses Suki to no end. Like no, it's not just the east asian coded characters i write as taking people to bed for social and material benefits, and the native-coded characters tend to get written in more explicit and steamy terms. The only reason you wouldn't see that is if you're only looking where you want to look.

#sex work mention#as if having these earth kingdom characters working any other jobs with racist histories and western perceptions would get me called out#things like cheap restaurants or laundries or laying down railroads#not to mention han bangqing's sing-song girls of shanghai is considered one of the best chinese novels EVER WRITTEN#in no small part because it depicts sex workers as human beings in spite of their customers treating them like consumable objects

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do think Blazing Saddles handled its one depiction of native americans very poorly, and the full extent of its representation of chinese workers on the railroad is they were literally just there. not even one single speaking line. unclear if this is worse or better than the redface.

it's fucking phenomenal at lampooning antiblack racism though. extremely blatant, extremely funny satire, which is constantly and loudly saying "racism is the philosophy of the terminally stupid at best and morally depraved at worst, and we should all be pointing and laughing at them 24/7"

plus the main character is a heroic black man who has to navigate a whole lot of bullshit but is constantly smirking at the extraordinarily stupid racists and inviting the audience into the joke. the one heroic white character is a guy who was suicidally depressed until he met the protagonist and they just instantly became buds, and he's firmly in a supporting role the whole time and happy to be there. the protagonist saves the day with the help of his black friends from the railroad, and uses the position of power he was given to uplift not only those friends, but all the railroad workers of other minorities too, in an explicit show of solidarity.

anyone saying "Blazing Saddles is racist" had better be talking about its treatment of non-black minorities. it had better not be such superficial takes as "oh but they say the n-word all the time" or "they have nazis and the kkk in there!" because goddamn if that's the full extent of your critique I very seriously suggest you read up on media analysis. there is too much going over your head, you need to learn to recognize satire.

#blazing saddles#finx watches tv#finx rambles#I recognize that I'm saying all this as someone who's not black#but I am also saying it as someone with a basic understanding of race relations in the usa#and a basic understanding of sarcasm#bc it really does not take more than that to recognize what they're doing in this movie#it is NOT subtle#and it is very funny#mel brooks movies are kinda hit or miss for me ngl#men in tights is great if a bit too crass for my taste#spaceballs has great jokes but the central story lacks any real heart so it doesn't grab me#history of the world was just kind of unpleasant and then I switched it off#but blazing saddles? phenomenal#I could not stop laughing the whole way through#and the central story DOES have heart bc it's the friendship between bart and#whassisname#jim#the Kid#plus bart working out how to succeed at an impossible task#also frankly cleavon little just grounds the comedy really well even before gene wilder shows up and we get their chemistry#bc he's cool calm collected and constantly inviting the audience into the joke#but the character's not too cool to ever mess up or ever be silly#he makes bad choices and gets into bad situations and then has to get himself out of them#but it's.....oh wait duh there's a term for this already#he's the straight man#he grounds all the zany nonsense by being in strong contrast to it#and he does a great job of it!#anyway#point is I deeply enjoyed this movie and I'm glad I finally watched it

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

In fact, far more Asian workers moved to the Americas in the 19th century to make sugar than to build the transcontinental railroad [...]. [T]housands of Chinese migrants were recruited to work [...] on Louisiana’s sugar plantations after the Civil War. [...] Recruited and reviled as "coolies," their presence in sugar production helped justify racial exclusion after the abolition of slavery.

In places where sugar cane is grown, such as Mauritius, Fiji, Hawaii, Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname, there is usually a sizable population of Asians who can trace their ancestry to India, China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia and elsewhere. They are descendants of sugar plantation workers, whose migration and labor embodied the limitations and contradictions of chattel slavery’s slow death in the 19th century. [...]

---

Mass consumption of sugar in industrializing Europe and North America rested on mass production of sugar by enslaved Africans in the colonies. The whip, the market, and the law institutionalized slavery across the Americas, including in the U.S. When the Haitian Revolution erupted in 1791 and Napoleon Bonaparte’s mission to reclaim Saint-Domingue, France’s most prized colony, failed, slaveholding regimes around the world grew alarmed. In response to a series of slave rebellions in its own sugar colonies, especially in Jamaica, the British Empire formally abolished slavery in the 1830s. British emancipation included a payment of £20 million to slave owners, an immense sum of money that British taxpayers made loan payments on until 2015.

Importing indentured labor from Asia emerged as a potential way to maintain the British Empire’s sugar plantation system.

In 1838 John Gladstone, father of future prime minister William E. Gladstone, arranged for the shipment of 396 South Asian workers, bound to five years of indentured labor, to his sugar estates in British Guiana. The experiment with “Gladstone coolies,” as those workers came to be known, inaugurated [...] “a new system of [...] [indentured servitude],” which would endure for nearly a century. [...]

---

Bonaparte [...] agreed to sell France's claims [...] to the U.S. [...] in 1803, in [...] the Louisiana Purchase. Plantation owners who escaped Saint-Domingue [Haiti] with their enslaved workers helped establish a booming sugar industry in southern Louisiana. On huge plantations surrounding New Orleans, home of the largest slave market in the antebellum South, sugar production took off in the first half of the 19th century. By 1853, Louisiana was producing nearly 25% of all exportable sugar in the world. [...] On the eve of the Civil War, Louisiana’s sugar industry was valued at US$200 million. More than half of that figure represented the valuation of the ownership of human beings – Black people who did the backbreaking labor [...]. By the war’s end, approximately $193 million of the sugar industry’s prewar value had vanished.

Desperate to regain power and authority after the war, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters studied and learned from their Caribbean counterparts. They, too, looked to Asian workers for their salvation, fantasizing that so-called “coolies” [...].

Thousands of Chinese workers landed in Louisiana between 1866 and 1870, recruited from the Caribbean, China and California. Bound to multiyear contracts, they symbolized Louisiana planters’ racial hope [...].

To great fanfare, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters spent thousands of dollars to recruit gangs of Chinese workers. When 140 Chinese laborers arrived on Millaudon plantation near New Orleans on July 4, 1870, at a cost of about $10,000 in recruitment fees, the New Orleans Times reported that they were “young, athletic, intelligent, sober and cleanly” and superior to “the vast majority of our African population.” [...] But [...] [w]hen they heard that other workers earned more, they demanded the same. When planters refused, they ran away. The Chinese recruits, the Planters’ Banner observed in 1871, were “fond of changing about, run away worse than [Black people], and … leave as soon as anybody offers them higher wages.”

When Congress debated excluding the Chinese from the United States in 1882, Rep. Horace F. Page of California argued that the United States could not allow the entry of “millions of cooly slaves and serfs.” That racial reasoning would justify a long series of anti-Asian laws and policies on immigration and naturalization for nearly a century.

---

All text above by: Moon-Ho Jung. "Making sugar, making 'coolies': Chinese laborers toiled alongside Black workers on 19th-century Louisiana plantations". The Conversation. 13 January 2022. [All bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

#abolition#tidalectics#caribbean#ecology#multispecies#imperial#colonial#plantation#landscape#indigenous#intimacies of four continents#geographic imaginaries

460 notes

·

View notes

Note

Eating your art style, sorry

Anyways, imagine if Jed can read Chinese (learned from the railroad workers, both historically and movie canon! Well meaning they speak Chinese in the movie) And translates something into English for Larry while everyone just collectively goes "sorry, huh?"

Larry would be so done with that situation

Imagine your boyfriend knowing Chinese but not being able to learn Latin

Edit: there's, there's a fanfic of this now. Go read it.

#this took literally forever#you really got me trying to draw ahkmenrah and attila here#google translated that don't try to see what is says#ask#anonymous#answered#night at the museum#natm#natm larry#larry daley#natm ahkmenrah#ahkmenrah#natm attila#attila the hun#natm octavius#gaius octavius#octavius#natm jedediah#jedediah#jedediah smith#jedediah and octavius#jedtavius#fanart#art#traditional art#took me 3 days to come up with this nonexistent plot#don't ask me who the new guy is I haven't thought about that and I never will#anyway thank you ♡ it was legitimately a fun idea and I liked drawing it#I just suck at character design

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

TODAYBORDAY IS LABOR DAY

Brought to you by your local children's librarian! 😊

The library today is, obviously, closed. Thank goodness. However, we were open earlier this weekend, and I was grateful to have been given a chance to make a labor day display in the children's department!

And Y'ALL. Pickings were SLIM. Believe it or not, but society at large does NOT like teaching children about worker's rights, unionizing, and negotiations! 😭 Never fear, however, because I, under an extreme time crunch (3pm on a friday right before labor day) came up with a short list on kids' books that might help get thoughts flowing on what Labor Day means to us as a country. Good ol' 'Merica or whatever we're saying these days.

Behold: a kid's labor day reading list! ⬇

The candy conspiracy : a tale of sweet victory is classic "boss gets a dollar, I get a dime" story about the power of labor and bargaining. With candy! 🍫🍭🍬 Quick, sweet, and good enough to eat.

Click Clack Moo: Cows that Type is a great story about negotiating for better working conditions. That's right, the barnyard goes on strike for electric blankets and a diving board in the duck pond! A silly, quick read, told largely by the typewritten letters from the cows themselves. Click Clack, Moo!

Hey, remember when children used to have to work countless hours for pennies a day if that just to possibly die or be permanently disfigured on the job? The traveling camera : Lewis Hine and the fight to end child labor is the story of one man's quest to document child labor all across the country in hopes of finally ending it for good— through the work of the National Child Labor Committee. Remember to thank labor laws for the good they've done in your life!

Every student in the country ought to learn about exactly how many people died unnecessary deaths in the industries before workplace safety laws were implemented nationwide. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire : core events of an industrial disaster is a nonfiction title about the how and whys of this horrific event. The most famous of its kind, we should not forget the people lost due to casual workplace cruelty and the demands of overwork.

Teach children to respect blue collar and working class heroes in Real Superheroes: a celebration of essential workers! From the people who keep our towns and cities free of debris and contaminants to healthcare professionals to emergency services, every down and dirty job is held by someone who keeps our towns up and running. Thanks, everyone! (I also recommend Night Job for the same reasons; very sweet, very good at portraying what a school janitor does as their work.)

I was going to add a book on the Mine Wars in West Virginia, since one recently published for a younger age group, but it was more teen than kid friendly unfortunately so I ended up cutting it. I was able to find another book on a different circumstance, however:

The real history of the transcontinental railroad covers a bevvy of relevant topics from the displacement of Native people in the west, the exploitation of Chinese immigrants, worker's rights, and the lingering ghost of Manifest Destiny that haunts this country to this day. Not every kid is ready for intersectional thinking on racism, xenophobia, and colonization, but at the very least, kids are very good at recognizing when a situation is "fair" or "unfair". Let them chew on this for a little bit and see what conversations come out of it.

Happy Labor Day, everyone! Be safe, be strong, and work in groups!

youtube

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

PEOPLE

I think there is a WELL of untapped potential in the category of jedtavius, learning each other's cultures especially

Because people forget that in the movie, it's historically accurate, it was the west side of the transcontinental railroad, those were Chinese workers! And in that the miniatures themselves have been there for 50 YEARS, I think it's safe to say they would influence each other the tiniest bit if not outright accepting not even mentioning how culture changes and grows overtime!

What about Chinese/Lunar New Year? Or lantern festivals? The languages? The games? There had to be Japanese folk as well, what if they played games like hanafuda and konpira funefune? Not to mention that most cowboys were Hispanic! What about the Hispanic folk? Día de muertos? Spanish sayings? How many times have one of the cowboys gotten tripped up talking to the Romans because they speak in a more polished English? What if Jedediah called Octavius pet names from the languages he knows?

POSSIBILITIES, PEOPLE, POSSIBLITIES

#night at the museum#natm jedediah#jedtavius#natm octavius#antropology#chinese culture#hispanic culture#the wild west#theres so much you could do#practically inspired by that one episode of Andi mack were she celebrates Chinese new Year#i love andi mack#such a good show

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oooooh… Cowgirl AU got me feeling things…

Clorinde as the sheriff who cuffs you and tosses you in a dark little cell in the town jail so she breed you in private…

Lynette and/or Arlecchino as wild bandits, bringing you back to their camp in the middle of the desert to fuck you by the campfire… the town thinks you’re an innocent maiden who’s been kidnapped just as she was due to be happily (unwillingly) wedded to a good (horrible) man, but you were actually seduced by their roguish charm…

Maybe Beidou is one of the Chinese workers the rail company imported as cheap labor to work on the new rail line coming though*, and she sneaks into your fancy house at night so she can fuck you nice and good before you shoo her out at dawn so your father doesn’t learn you’ve fallen in love with one of those ‘damn [insert slur typical of the 19th Century here]’…

*per the Smithsonian, 1/6 of Chinese immigrants in the 1860s ended up working on railroad construction, and the Guardian puts a more specific number of Chinese working on railroad construction at roughly 15,000.

Ohmygod this is all really cool! Sheriff Clorinde and Arlecchino + Lynette as bandits?? That’s so hot jaidjsjdn 💕

I will say though, despite how cool it is that you know so much about the historical accuracy of the cowboy times, I’m going to leave out any racial/discriminatory topics since it can be really sensitive/triggering for my readers.

If I choose to write an AU based on historic times (Ex. Empress AU, Pirate AU, Cowboy AU, etc.) there will be little to no mention of discrimination even if it’s historically accurate. This blog is safe space for all sapphics 💘

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

#tumblr polls#red dead redemption 2#red dead redemption two#red dead fandom#red dead redemption#rdr2#rdr#rdr1#arthur morgan#john marston#charles smith#sadie adler#jack marston#kieran duffy#red harlow#uncle rdr2#landon ricketts#bonnie macfarlane#gta v#rockstar games#gaming#gaming poll#red dead redemption community

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

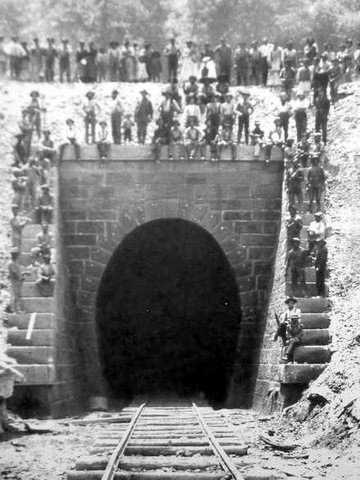

Dingess Tunnel

Hidden deep within the coal filled Appalachian Mountains of Southern West Virginia rests a forgotten land that is older than time itself. Its valleys are deep, its waters polluted and its terrain is as rough as the rugged men and women who have occupied these centuries old plats for thousands of years.

The region is known as “Bloody Mingo” and for decades the area has been regarded as one of the most murderous areas in all of American history.

The haunted mountains of this territory have been the stage of blood baths too numerous to number, including those of the famed Hatfield’s and McCoy’s, Matewan Massacre and the Battle of Blair Mountain. Even the county’s sheriff was murdered this past spring, while eating lunch in his vehicle.

Tucked away in a dark corner of this remote area is an even greater anomaly – a town, whose primary entrance is a deserted one lane train tunnel nearly 4/5 of a mile long.

The story of this town’s unique entrance dates back nearly a century and a half ago, back to an era when coal mining in West Virginia was first becoming profitable.

For generations, the people of what is now Mingo County, West Virginia, had lived quiet and peaceable lives, enjoying the fruits of the land, living secluded within the tall and unforgiving mountains surrounding them.

All of this changed, however, with the industrial revolution, as the demand for coal soared to record highs.

Soon outside capital began flowing into “Bloody Mingo” and within a decade railroads had linked the previously isolated communities of southern West Virginia to the outside world.

The most notorious of these new railways was Norfolk & Western’s line between Lenore and Wayne County – a railroad that split through the hazardous and lawless region known as “Twelve Pole Creek.”

At the heart of Twelve Pole Creek, railroad workers forged a 3,300 foot long railroad tunnel just south of the community of Dingess.

As new mines began to open, destitute families poured into Mingo County in search of labor in the coal mines. Among the population of workers were large numbers of both African-Americans and Chinese emigrants.

Despising outsiders, and particularly the thought of dark skinned people moving into what had long been viewed as a region exclusively all their own, residents of Dingess, West Virginia, are said to have hid along the hillsides just outside of the tunnel’s entrance, shooting any dark skinned travelers riding aboard the train.

Though no official numbers were ever kept, it has been estimated that hundreds of black and Chinese workers were killed at the entrance and exits of this tunnel.

Norfolk & Western soon afterward abandonment the Twelve Pole line. Within months two forces of workmen began removing the tracks, ties, and accessory facilities.

#Dingess Tunnel#haunted tunnels#ghost and hauntings#paranormal#ghost and spirits#haunted locations#haunted salem#myhauntedsalem#paranormal phenomena

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daguerreotype of an Asian man, possibly a Chinese railroad worker, America, c. 1850s

#a very rare and beautiful image#the look in his eyes!#19th century#1800s#1850s#19th century fashion#historical fashion#fashion history#men's fashion#occupational#19th century photography#daguerreotype

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

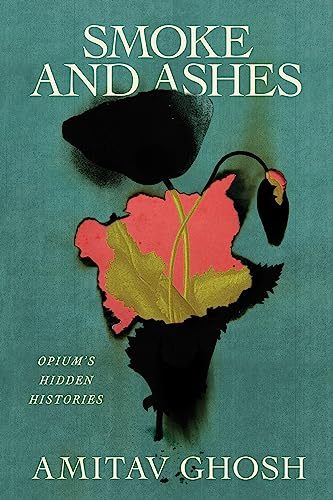

Smoke and Ashes: Opium's Hidden Histories

"Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories" is a sweeping and jarring work of how opium became an insidious capitalistic tool to generate wealth for the British Empire and other Western powers at the expense of an epidemic of addiction in China and the impoverishment of millions of farmers in India. The legacy of this “criminal enterprise,” as the author puts it, left lasting influences that reverberate across cultures and societies even today.

Written in engaging language, Smoke and Ashes is a scholarly follow-up to the author’s famous Ibis trilogy, a collection of fiction that uses the opium trade as its backdrop. In Smoke and Ashes, the author draws on his years-long research into opium supplemented by his family history, personal travels, cross-cultural experience, and expertise in works of historical verisimilitude. Composed over 18 chapters, the author delves into a diverse set of primary and secondary data, including Chinese sources. He also brings a multidimensional angle to the study by highlighting the opium trade's legacy in diverse areas such as art, architecture, horticulture, printmaking, and calligraphy. 23 pictorial illustrations serve as powerful eyewitness accounts to the discourse.

This book should interest students and scholars seeking historical analysis based on facts on the ground instead of colonial narratives. Readers will also find answers to how opium continues to play an outsize role in modern-day conflicts, addictions, corporate behavior, and globalism.

Amitav Ghosh’s research convincingly points out that while opium had always been used for recreational purposes across cultures, it was the Western powers such as the British, Portuguese, the Spaniards, and the Dutch that discovered its significant potential as a trading vehicle. Ghosh adds that colonial rulers, especially the British, often rationalized their actions by arguing that the Asian population was naturally predisposed to narcotics. However, it was British India that bested others in virtually monopolizing the market for the highly addictive Indian opium in China. Used as a currency to redress the East India Company (EIC)’s trade deficit with China, the opium trade by the 1890s generated about five million sterling a year for Britain. Meanwhile, as many as 40 million Chinese became addicted to opium.

Eastern India became the epicenter of British opium production. Workers in opium factories in Patna and Benares toiled under severe conditions, often earning less than the cost of production while their British managers lived in luxury. Ghosh asserts that opium farming permanently impoverished a region that was an economic powerhouse before the British arrived. Ghosh’s work echoes developmental economists such as Jonathan Lehne, who has documented opium-growing communities' lower literacy and economic progress compared to their neighbors.

Ghosh states that after Britain, “the country that benefited most from the opium trade” with China, was the United States. American traders skirted the British opium monopoly by sourcing from Turkey and Malwa in Western India. By 1818, American traders were smuggling about one-third of all the opium consumed in China. Many powerful families like the Astors, Coolidges, Forbes, Irvings, and Roosevelts built their fortunes from the opium trade. Much of this opium money, Ghosh shows, also financed banking, railroads, and Ivy League institutions. While Ghosh mentions that many of these families developed a huge collection of Chinese art, he could have also discussed that some of their holdings were most probably part of millions of Chinese cultural icons plundered by colonialists.

Ghosh ends the book by discussing how the EIC's predatory behaviors have been replicated by modern corporations, like Purdue Pharma, that are responsible for the opium-derived OxyContin addiction. He adds that fossil fuel companies such as BP have also reaped enormous profits at the expense of consumer health or environmental damage.

Perhaps one omission in this book is that the author does not hold Indian opium traders from Malwa, such as the Marwaris, Parsis, and Jews, under the same ethical scrutiny as he does to the British and the Americans. While various other works have covered the British Empire's involvement in the opium trade, most readers would find Ghosh's narrative of American involvement to be eye-opening. Likewise, his linkage of present-day eastern India's economic backwardness to opium is both revealing and insightful.

Winner of India's highest literary award Jnanpith and nominated author for the Man Booker Prize, Amitav Ghosh's works concern colonialism, identity, migration, environmentalism, and climate change. In this book, he provides an invaluable lesson for political and business leaders that abdication of ethics and social responsibility have lasting consequences impacting us all.

Continue reading...

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fresno Chinatown, c. 1880. Photographer unknown.

The Armed Chinatown of Fresno

For this short roadtrip away from San Francisco, this brief paragraph from the Stockton Independent newspaper of September 15, 1879, mentioning “guns, pistols and daggers” illustrates the seriousness with which early Chinese Americans in Fresno, California, and other rural Chinatowns addressed external threats to their lives and livelihoods. This included threats from the then-surging Workingmen’s Party, led by notorious demagogue, xenophobe and racist agitator Denis Kearney.

from the "Valley Items" column published in the Stockton Independent newspaper of September 15, 1879.

In the 1870s Kearney began denouncing Chinese immigrants as the cause of white workers’ economic woes. By 1878, he frequently gave violent speeches against Chinese at San Francisco’s Sandlot forum, blaming them for white labor problems. His movement propelled his party to the 1879 California Constitutional Convention where various anti-Chinese laws, including a ban on employing Chinese laborers, were enacted. Kearney also took credit for nationalizing the debate over Chinese immigration to the US, culminating in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Dennis Kearney (1847-1907), Irish-American political leader, influential in the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

As recounted in more detail by author Jean Pfaelzer in her book, Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans, (pub. Random House) rural Chinatowns throughout California became targets of economic boycotts and vigilante violence. Fresno’s Chinatown, established during the construction of railroad lines after the Transcontinental Railroad’s completion in 1869, was not immune from persecution by white agitators. Despite it’s the residents arming themselves, possibly for deterrence, the community faced vigilante violence in the next decade.

The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 did little to calm rural California and its unemployed white workers. In 1886, an anti-Chinese economic boycott movement began in Truckee. Fresno’s local anti-Chinese club set up a whites-only employment office, attracting four hundred men. However, during the early spring planting season near Fresno, vineyard and fruit growers in the Fresno area rejected the boycott, stating that it was “absolutely impossible” to obtain white labor. The troubles in Fresno represented a symptom of the violence and roundup of Chinese Americans throughout California during the latter half of the 19th century, when Chinese were literally driven out rural areas to concentrate in the state’s cities, particularly San Francisco.

A map showing more than 200 incidents of rounding up Chinese in California for expulsions during 1849 to 1906.

Rather than calm the hostility by whites against Chinese, the congressional enactments of the 1882 Act and its 10-year extension, the Geary Act of 1892, seemed to foment more anti-Chinese boycotts, violence, and expulsions.

In Fresno, anti-Chinese violence peaked in the summer of 1893, when deliberately-set fires in Fresno destroyed several mills and packinghouses, not all of which employed Chinese workers. White workers demanded that merchants fire their Chinese workers. Fearing the mob, several packinghouse and vineyard owners complied and fired their Chinese workers. Many Chinese field-workers sought protection in Fresno’s Chinatown, which continued to provide refuge from mob violence.

Detail from Fresno Chinatown's main street, c. 1880.

On August 15, rioters invaded vineyards near Fresno, and another white mob raided the Fracher Creek Nursery, capturing Chinese workers, stealing their money and belongings, and bludgeoning one man to death. The mob marched the Chinese nursery workers toward Fresno in the valley heat until the sheriff intervened and released them. That same week, Chinese packers at the nearby Earl Fruit Company were forced onto a train to Fresno and given five days to leave the county. Gangs forced more Chinese men out of local vineyards and destroyed their tent camps. Hundreds of unemployed white workers and vagrants milled around Fresno’s streets, watching the Chinese depart. The roundups and expulsions of Chinese workers did not solve the massive unemployment crisis. Even after the purges, few jobs were available for whites. Hunger exacerbated the riots. By late August, Fresno’s Presbyterian church was providing eight hundred meals nightly to white men, some of whom had not eaten for days. The city council’s plan to give meal tickets to “idle men” for cleaning alleys failed due to a lack of funds.

The roundups and expulsions of Chinese did not solve the crisis of massive unemployment. Even after the purges, there were few jobs for whites. Hunger exacerbated the riots. Toward the end of August, Fresno’s Presbyterian church was nightly providing eight hundred meals to white men, some of whom had not eaten for days. The city council’s plan to give meal tickets to “idle men” for cleaning alleys failed when it ran out of money. The supervisors moved some of the “tramps and ruffians” out of town by forming them into chain gangs to clear roads or do field work.

The temple in old Fresno Chinatown, c. 1880. This detail from a larger photo appears to depict the Chee Kung Tong temple at 939 G Street, which was built in the early 1880's with contributions from the tong. The temple housed a wooden altar reportedly carved in 1869 in China. The two-story brick structure contained a meeting hall on the first floor. Lodgings wer located next door. The joss house was closed to the public in 1936 and later used by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Society. The structure no longer exists.

The purge of Chinese workers from California’s fields, citrus groves, and orchards worsened the economic situation. Fresno’s labor bureau had over six hundred men seeking work, but farmers and nurserymen knew their crops would perish if unskilled laborers replaced the skilled Chinese workers, such as fruit tree "budders." Banks closed, and local stores went out of business.

Roundups of Chinese residents continued into the following year, often with judicial sanction. In May 1894, the Del Rio Rey Vineyard in Fresno replaced its white employees with Chinese workers. Within days, dynamite bombs were found under the bunkhouses. The new Chinese workers fled in response to the terrorism, but no arrests were made. Today’s diaspora communities across the US could learn from these pioneers who, contrary to passive stereotypes, were prepared to protect themselves by any means necessary. This was just one small railroad Chinatown arming itself in difficult times.

New Year's celebration and parade in Fresno, California, c. 1900. Some researchers have speculated that the dragon shown in this photo was the well-known Marysville Chinatown dragon which appeared all over California during this period.

Lessons from these small Chinatowns of the past regain relevance today. Asian American communities should recommit to self-defense where local governments fail to provide basic public safety.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1833, Parliament finally abolished slavery in the British Caribbean, and the taxpayer payout of £20 million in “compensation” [paid by the government to slave owners] built the material, geophysical (railways, mines, factories), and imperial infrastructures of Britain [...]. Slavery and industrialization were tied by the various afterlives of slavery in the form of indentured and carceral labor that continued to enrich new emergent industrial powers [...]. Enslaved “free” African Americans predominately mined coal in the corporate use of black power or the new “industrial slavery,” [...]. The labor of the coffee - the carceral penance of the rock pile, “breaking rocks out here and keeping on the chain gang” (Nina Simone, Work Song, 1966), laying iron on the railroads - is the carceral future mobilized at plantation’s end (or the “nonevent” of emancipation). [...] [T]he racial circumscription of slavery predates and prepares the material ground for Europe and the Americas in terms of both nation and empire building - and continues to sustain it.

Text by: Kathryn Yusoff. "White Utopia/Black Inferno: Life on a Geologic Spike". e-flux Journal Issue #97. February 2019.

---

When the Haitian Revolution erupted [...], slaveholding regimes around the world grew alarmed. In response to a series of slave rebellions in its own sugar colonies, especially in Jamaica, the British Empire formally abolished slavery in the 1830s. [...] Importing indentured labor from Asia emerged as a potential way to maintain the British Empire’s sugar plantation system. In 1838 John Gladstone, father of future prime minister William E. Gladstone, arranged for the shipment of 396 South Asian workers, bound to five years of indentured labor, to his sugar estates in British Guiana. The experiment [...] inaugurated [...] "a new system of [...] [indentured servitude]," which would endure for nearly a century. [...] Desperate to regain power and authority after the war [and abolition of chattel slavery in the US], Louisiana’s wealthiest planters studied and learned from their Caribbean counterparts. [...] Thousands of Chinese workers landed in Louisiana between 1866 and 1870, recruited from the Caribbean, China and California. [...] When Congress debated excluding the Chinese from the United States in 1882, Rep. Horace F. Page of California argued that the United States could not allow the entry of “millions of cooly slaves and serfs.”

Text by: Moon-Ho Jung. "Making sugar, making 'coolies': Chinese laborers toiled alongside Black workers on 19th-century Louisiana plantations". The Conversation. 13 January 2022.

---

The durability and extensibility of plantations [...] have been tracked most especially in the contemporary United States’ prison archipelago and segregated urban areas [...], [including] “skewed life chances, limited access to health [...], premature death, incarceration [...]”. [...] [In labor arrangements there exists] a moral tie that indefinitely indebts the laborers to their master, [...] the main mechanisms reproducing the plantation system long after the abolition of slavery [...]. [G]enealogies of labor management […] have been traced […] linking different features of plantations to later economic enterprises, such as factories […] or diamond mines […] [,] chartered companies, free ports, dependencies, trusteeships [...].

Text by: Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. "Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times". Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives (edited by Petitcrops, Macedo, and Peano). Published 2023.

---

Louis-Napoleon, still serving in the capacity of president of the [French] republic, threw his weight behind […] the exile of criminals as well as political dissidents. “It seems possible to me,” he declared near the end of 1850, “to render the punishment of hard labor more efficient, more moralizing, less expensive […], by using it to advance French colonization.” [...] Slavery had just been abolished in the French Empire [...]. If slavery were at an end, then the crucial question facing the colony was that of finding an alternative source of labor. During the period of the early penal colony we see this search for new slaves, not only in French Guiana, but also throughout [other European] colonies built on the plantation model.

Text by: Peter Redfield. Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana. 2000.

---

To control the desperate and the jobless, the authorities passed harsh new laws, a legislative program designed to quell disorder and ensure a pliant workforce for the factories. The Riot Act banned public disorder; the Combination Act made trade unions illegal; the Workhouse Act forced the poor to work; the Vagrancy Act turned joblessness into a crime. Eventually, over 220 offences could attract capital punishment - or, indeed, transportation. […] [C]onvict transportation - a system in which prisoners toiled without pay under military discipline - replicated many of the worst cruelties of slavery. […] Middle-class anti-slavery activists expressed little sympathy for Britain’s ragged and desperate, holding […] [them] responsible for their own misery. The men and women of London’s slums weren’t slaves. They were free individuals - and if they chose criminality, […] they brought their punishment on themselves. That was how Phillip [commander of the British First Fleet settlement in Australia] could decry chattel slavery while simultaneously relying on unfree labour from convicts. The experience of John Moseley, one of the eleven people of colour on the First Fleet, illustrates how, in the Australian settlement, a rhetoric of liberty accompanied a new kind of bondage. [Moseley was Black and had been a slave at a plantation in America before escaping to Britain, where he was charged with a crime and shipped to do convict labor in Australia.] […] The eventual commutation of a capital sentence to transportation meant that armed guards marched a black ex-slave, chained once more by the neck and ankles, to the Scarborough, on which he sailed to New South Wales. […] For John Moseley, the “free land” of New South Wales brought only a replication of that captivity he’d endured in Virginia. His experience was not unique. […] [T]hroughout the settlement, the old strode in, disguised as the new. [...] In the context of that widespread enthusiasm [in Australia] for the [American] South (the welcome extended to the Confederate ship Shenandoah in Melbourne in 1865 led one of its officers to conclude “the heart of colonial Britain was in our cause”), Queenslanders dreamed of building a “second Louisiana”. [...] The men did not merely adopt a lifestyle associated with New World slavery. They also relied on its techniques and its personnel. [...] Hope, for instance, acquired his sugar plants from the old slaver Thomas Scott. He hired supervisors from Jamaica and Barbados, looking for those with experience driving plantation slaves. [...] The Royal Navy’s Commander George Palmer described Lewin’s vessels as “fitted up precisely like an African slaver [...]".

Text by: Jeff Sparrow. “Friday essay: a slave state - how blackbirding in colonial Australia created a legacy of racism.” The Conversation. 4 August 2022.

#abolition#tidalectics#multispecies#ecology#intimacies of four continents#ecologies#confinement mobility borders escape etc#homeless housing precarity etc#plantation afterlives#archipelagic thinking

181 notes

·

View notes

Photo

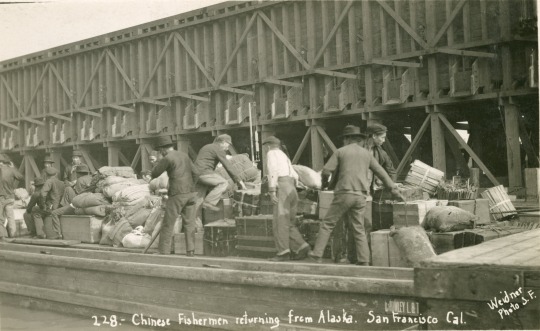

This 1904 image of Chinese fishermen on a dock, having returned from Alaska to San Francisco, helps to illustrate Chinese workers’ huge role in the cannery business at the time. Chinese immigrants have a long history in Alaska; many Chinese immigrants built railroads, worked in mines, and played a large role in the cannery industry. Alaska’s wild salmon industry was turned into today’s international, multi-billion-dollar business by immigrants. Chinese immigrants were the first to take over salmon cannery work, and were followed by Japanese workers, who were then followed by Filipino workers, according to San Francisco Maritime’s Park Curator.

#Chinese History#Alaska#California#San Francisco#1900s#AANHPI Month#AANHPI#AAPI Month#AAPI#Libraries#Librarian

24 notes

·

View notes