#don fernando de austria

Text

Don Fernando de Austria (1571-1578). By Bartolomé González.

#monarquía española#reino de españa#infantes de españa#don fernando de austria#casa de austria#kingdom of spain#house of spain#museo del prado#príncipe de asturias#principality of asturias#asturias#bartolomé gonzález#bartolome gonzalez#royalty

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

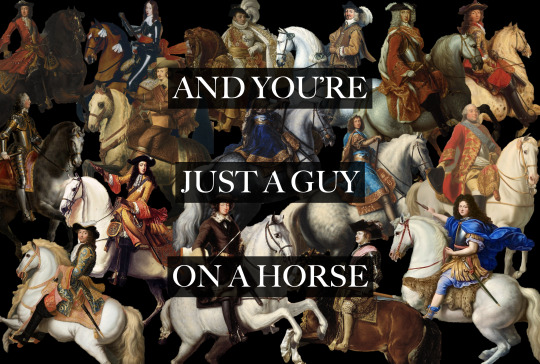

The Life of Joan of Arc – Jules-Eugène Lenepveu // Louis XIV at the Taking of Besancon – Adam Frans van der Meulen // William III of England – Jan Wyck // Infant-Cardinal Don Fernando of Austria on Horseback – Gaspar de Crayer // Portrait of Johan Wolphert van Brederode – School of Thomas de Keyser // Equestrian Portrait of Philippe de France – Pierre Mignard // Karl XI, King of Sweden – David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl // Equestrian Portrait of Louis XIV – René-Antoine Houasse // Equestrian Portrait of Charles XI of Sweden – David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl // Herzog Karl V. von Lothringen – unknown artist // King Charles XI of Sweden Riding a Horse – David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl // Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, Saluting His Army on the Battlefield – Alexander Roslin // Equestrian Portrait of Philip IV – Diego Velázquez // Jérôme Bonaparte, King of Westphalia – Antoine-Jean Gros // Equestrian Portrait of King George II – Joseph Highmore // Equestrian Portrait of William II, Prince of Orange – Anselm van Hulle // Equestrian Portrait of King William III – Jan Wyck // Guy On A Horse – Maisie Peters

#as soon as i heard maisie reference joan of arc you know i had to make an edit for it#also i heard this song and immediately thought “lmao all those thousands of equestrian portraits”#they truly are all just a guy on a horse#joan of arc#jeanne d'arc#saint joan of arc#equestrian portrait#equestrian portraiture#guy on a horse#the good witch#the good witch maisie peters#maisie peters the good witch#tgw maisie peters#tgw#maisie peters tgw#the good witch deluxe#maisie peters#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art

109 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi my friend 👋, Who is your favorite Habsburg King? One for Austria and One for Spain?

Who is your least Favorite king of all time? I wish you the best.

HIIII !! how good is to receive an ask just the moment i was thinking about going to random dms to infodump people about random hyperfixations . specially from you my friend im wishing you the best too .

I really like habsburg story as it is full of girlbosses and malewifes ( a really cool dynasty ) . IIIII i really like the austrian ones , spaniards are always a mystery to me . I lived there for four years and I still dont catch their accent . My favourite habsburg monarch is emperor Franz II im not normal about him . there is an strong need to scream everytime i think about him . People probably must known him more for the napoleonic wars but I think he is very interesting by his own right . But tbh I really like all habsburgs from Austria they are very babygirls . Maximilian I , Charles V , Ferdinand I , Rudolf II , Leopold I , Charles VI , Marie Theresia , Joseph II and Ferdinand I of Austria ( not to confuse him with Ferdinand I of the Holy Roman Empire ) are my favourites but I really like all of them except for Leopold II and Francis I ( i have a love-hate relationship with him bc he is funny but I hate that he wasnt faithful to Marie Theresia bc !! SHE WAS LITERALLY A 10 ?! ) . From Spain I truly only like Felipe I and Carlos II . The other ones are very boring to me but I get that Felipe II was interesting . I am not mentioning Charles I because I already mentioned him as emperor . Well . He should be here because he is a spanish one yeah . so yeah he is also here i really like him i find him too funny and he was very babygirl . I mostly like infantes of Spain like the Cardinal-Infante Fernando de Austria , Don Juan José de Austria , Carlos de Austria ( son of Felipe II - prince of Asturias before Felipe III ) and Carlos de Austria ( brother of Felipe IV , I really like him !! I find him autistic and awkard asf and I really like that in people . Like Franz II ) . Those are my tastes in Habsburgs sadly I will try not to talk about the women too as to not make this too big but I also love their queens . Felipe IV is an enigma to me I find him incomprehensible . Truly a mystery like Spain itself . I liked that moment when Louis XIV and Philippe d'Orléans went to hug him and cry when they met to give Louis XIV his wife that was hilarious .

2.IIII I would say Henry VIII cus he is easy to hate but I do also hate Henry VII because he is the one who made my homecountry a mess ( Wales - if you ever see me talking weird english , is because its not my native language ! I speak welsh hehe ) . I really really hate Charles X of France because he ruined my favourite queer mentally ill dynasty ( bourbons ) and destroyed everything Louis XVIII worked for ( he is my !! favourite historical figure ever ) . I dont really hate many monarchs bc even if they are bad they are amusing to know about . The real hate I have to a historical figure is to Saint-Just but i completely agree with his ideas but he was a real asshole and i dont know how robespierre was friend of that guy . he was literally an edgy teen trying to be a politic is everything i hate about politics but worse because i agree with everything he said . except killing louis xvi that was a mistake . they should have put louis xvi in a box and send it to austria if they didnt wanted him there

#mariana ' s#HIIIII !! i have to send you more personal asks too#but i always fear that my tastes in history are too weird like who the fuck is louis xviii#i I HAVE SOME IDEAS may come back tomorrow to ask bc i need to go to sleep#see ya later#:3#<--- im always looking at your interactions like this but i am very bad at showing emotions on text

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello cparti! First of all, thank you for your blog! I'm following you for a while now and I really enjoy your 17th century content. There can never be enough of that for my taste. Your knowledge about Felipe IV. leads me to my question and my reason to message you: Do you by chance have any information what the king and his politicians were up to in the year 1658 specifically? I'm doing some research for a story and a spanish perspective would really help me to connect the information I already gathered. Thank you so much in advance! Love, la mélancholie

thank you for your message!!! and for your kind words <333 i can maybe give an overview? let me know if you're looking for something specific!

1658 is a terrible, no good year for the spanish monarchy lmao: there's several ongoing wars — vs. france and vs. portugal (supported by, shocker, france and england) — and finances are going impressively bad overall (an inefficient, overextended system, the war... and the massive amounts of money invested in leopold i's campaing for holy roman emperor lol).

internationally, for the war with france, both parties are exhausted in terms of men and money, but england's last minute entry with france + big defeats (like don juan of austria at dunkirk/battle of the dunes - which even cost him the governorship of low countries lol) tip the balance decisively in france's favor and kinda force the treaty of the pyrennees. the attempt to stop the independence of portugal is doing somewhat better (ie it doesn't look hopeless yet) — i believe the siege of badajoz, which spanish troops win, is ongoing that year — but it's all syphoning resources like crazy, resources which the monarchy doesn't have after almost 30 years of uninterrupted war against basically everyone.

domestically, the court is not going through a particularly tough time (apart from financing problems... eg. no credit for food anymore lol. parties are still on though) and the government is stable. 1658 is the tail end of luis de haro's tenure as prime minister (he died in 1661), and he never lost the king's support... ever after delivering a staggering loss on the portuguese front the very next year lol, at the battle of evora. the birth of infante fernando tomás makes felipe's succession look very secure (2 daughters + 2 sons), which allows him to start seriously planning to marry off maria teresa to louis xiv (instead of the safe bet/ally leopold i as they were already preparing) without it being as much of a gamble (hah!!).

i think this is the general summary... if there's anything in particular which would be useful to you don't hesitate to hit me up and i'll help as best as i can 🙏

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madrid, Camarilla

Desde que la Estirpe se quebrara en dos sectas, hace más de quinientos años, la Espada aferró con firmeza el control de la capital de España, fracasando todos los intentos de la Torre por arrebatárselo.

El 6 de Octubre de 1999 el Cardenal Monçada fue destruído y, a partir de ese momento, se desató una guerra interna por sucederle que se mantuvo durante casi cuatro años y medio, hasta que la Camarilla se dejó caer con todas sus fuerzas.

La Torre buscaba saldar así las cuentas por la caída de Barcelona en 1997, un ataque a sangre y fuego del que solo sobrevivieron los pocos vástagos barceloneses que se encontraban ausentes de la ciudad por diversos motivos.

Durante la noche del 10 al 11 de Marzo de 2004 comenzó la Batalla por Madrid, que prosiguió en horas diurnas por hordas de ghoules de ambas sectas desde el momento que se produjeron los atentados del 11M orquestados por la Camarilla. La Batalla se desarrolló hasta la noche del 15 al 16 de Marzo, alzándose la Camarilla con la victoria.

Muy pocos fueron los Sabbats que lograron huir, recibiendo el resto el mismo trato que se ofreció a los vástagos de la derrotada Barcelona. La noche del 17 de Marzo era proclamado Príncipe de Madrid Don Fernando de Austria, del Clan Ventrue.

(En el foro se desarrollará más la ambientación, historia y cronología de los acontecimientos)

0 notes

Text

Marcelo Hidalgo Sola estaciona la moto frente a la Casa Rosada

El solar en el que está emplazada la Casa Rosada fue, durante toda la historia de Buenos Aires, la sede de las distintas y sucesivas autoridades políticas que gobernaron el país. Una Casa cuya belleza arquitectónica y su distintivo color rosado hacen única en su tipo. Su fisonomía actual data del año 1783 y es producto de su unión con el antiguo edificio de Correos.

La Casa Rosada ubicada frente a la Plaza de Mayo, regala su magnífico porte a todo aquel que ubique en el mapa la calle Balcarce 50 y se llegue hasta allí. En las orillas mismas del Río de la Plata la actual edificación , de corte palaciego e inconfundibles balcones con arcadas pronunciadas, se alza el lugar en donde estaba emplazado el primer fuerte que tuvo como defensa la ciudad de Buenos Aires

Cuenta la historia que a poco de blandir la espada en el suelo para fundar por segunda vez la Ciudad de la Santísima Trinidad y Puerto del Buen Ayre en 1580, Don Juan de Garay hizo cavar una zanja y terraplenes formados con las mismas tierras extraídas de ella. Con esta demarcación quedaba constituído un precario fuerte , una empalizada de tierra que se conoció como “Real Fortaleza de San Juan Baltasar de Austria” o “Castillo de San Miguel” que debía funcionar como protección ante los terribles malones indígenas.

Recién en 1595, el gobernador Fernando de Zárate mandó construir un fuerte propiamente dicho. Es decir, mandó a levantar una muralla de 120 metros de lado, con foso y puente levadizo propio. La construcción que se alzó sobre las barrancas que entonces daban al río, no fue una construcción improvisada. Sin embargo,resultó muy poco útil en sentido práctico. Las costas del Río de la Plata -explica Marcelo Hidalgo Sola- son imposibles de navegar para los barcos de gran porte. Los inmensos bancos de arena próximos a la márgen del río hacen que toda embarcación que quiera acercarse a tierra encalle, hoy como antaño, indefectiblemente frente a la costa de Buenos Aires.

De verdadero fuerte a sede de Gobierno

Sin embargo, el fuerte era símbolo de buena defensa e imprescindible para desalentar los ataques enemigos. Por ello, la ciudad se hizo construir a principios del siglo XVIII un sólido fuerte. Levantado íntegramente de ladrillos, sus paredes amuralladas y sus bastiones perduraron hasta su demolición tan solo 150 años más tarde.

Durante el tiempo de la Independencia ,ya inaugurado el siglo XIX, esta Casa que había sido residencia de gobernadores y virreyes españoles, albergó, con muy pocas reformas, a las autoridades de los sucesivos gobiernos patrios: las Juntas, los Triunviratos, los Directores Supremos, los Gobernadores de Buenos Aires y el Primer Presidente de la Argentina, Bernardino Rivadavia.

Fue recién en 1862 cuando recuperó protagonismo al constituirse como sede del gobierno político cuando Mitre se instaló con sus ministros. Más tarde, quien fue su sucesor, Sarmiento, amante del diseño y de la ornamentación arquitectónica, embelleció la morada del Poder Ejecutivo Nacional con un jardín interno y pintó la fachada de color rosado. Un detalle que la haría única y distintiva, pero que tuvo su origen en un motivo más estético y práctico. Este color, que hoy la hace mundialmente conocida, no fue elegido por ser considerado el más bello, sino que se eligió para guardar la estética general y evitar el deterioro causado por la humedad. En esa época el rosado que se utilizaba para pintar las construcciones, era una mezcla hecha de cal y sangre bovina que funcionaba como un excelente impermeabilizador y sellador que combatía de modo excelente la humedad de los cimientos y paredes.

Un verdadero Palacio de Gobierno

La construcción de la actual Casa de Gobierno comenzó en 1873 cuando por decreto se ordenó construir el edificio de Correos y Telégrafos en la esquina de Balcarce e Hipólito Yrigoyen. Tiempo después, el presidente Julio A. Roca decidió la construcción del definitivo Palacio de Gobierno en la esquina de Balcarce y Rivadavia, un edificio de las mismas características arquitectónicas al vecino Palacio de Correos. Ambos edificios fueron unidos en 1886 mediante el diseño de un gran pórtico que hoy constituye la entrada principal de la Casa Rosada y que da hacia Plaza de Mayo.

Entre las curiosidades que más destacan, se encuentra por ejemplo la construcción de El Salón Blanco , lugar en donde se realizan los actos de gobierno de mayor trascendencia . Su diseño tiene un balcón o galería alta que lo circunda y que posee puertas falsas recubiertas con espejos especialmente contemplados en su arquitectura para dar una sensación de amplitud al lugar. Solo una de las puertas, la que está ubicada en el centro del sector derecho ingresando al salón, es la que se abre, el resto son falsas.

La Casa Rosada tiene un Hall de Honor que rinde homenaje a todos los presidentes que tuvo la Argentina. Allí se exhiben los bustos de cada presidente elegido por el pueblo, en un recorrido que va de la mano de la línea cronológica de su mandato . Hasta 1973 se exhibían en el Salón Norte y fueron trasladados por un decreto a donde residen actualmente. Este salón y la Casa Rosada en su conjunto constituyen un lugar imprescindible para conocer y aprender de la historia política de nuestro país de primera mano, tal como si uno estuviera en el mismo centro de donde se teje la historia de la Argentina.

Originally published at on https://viajeenmoto.com.ar March 15, 2023.

0 notes

Photo

Infante don Fernando de Austria (1577), by Alonso Sánchez Coello.

#Alonso Sánchez Coello#monarquia española#reino de españa#infantes de españa#infante de españa#casa de austria#don fernando de austria#principe de asturias#full-length portrait#alonso sanchez coello#full length portrait#kingdom of spain#house of habsburg

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Limbless Admirals

Many who had made it far in a navy were often scarred by their service. Be it physically or psychologically. Lord Horatio Nelson is considered to have been a great sailor despite his physical limitations. He had brought his country some great victories. And was thus declared a national hero. But he was not the only admiral who lived his life limbless. The next three admirals were equally fearless in leading their fleets against the enemy, even if they were missing some parts of their bodies.

Don Blas de Lezo y Olavarrieta (1688-1741)

Admiral Blas de Lezo, by unknown, 18th century (x)

This highly respected Spanish admiral lost his left leg to an English roundshot during the battle of Velez-Malaga, fought off Gibraltar in 1704. He recovered from his injuries, and three years later he helped a Franco-Hispanic force defend Toulon against an Allied ( England, Austria,Savoy and Netherland) attack. It was there that he lost his left eye, during an attack on the fortified heights of Santa Caterina. Despite his injuries he returned to service, and in 1714 he was injured again, the time during the siege of barcelona, when he lost his right arm. To his men, the one- eyed, one armed and one legged commander was known as Patapalo (Pegleg), or even Mediohombre (Half a Man). However, he still went on to become an admiral, his most notable achievement being the defence of Cartagena des Indies against Admiral Vernon in 1737. De Lezo fell ill with the plague shortly after the battle and died in Cartagena on 7 September 1741.

John Benbow (1653-1702)

Admiral John Benbow, by Godfrey Kneller 1701 (x)

This English admiral was more fortunate than Don Blas de Lezo, as he has never received a serious injury until his final sea battle. He earned his reputation fighting the Barbary Pirates during the 1670s, but his performance during the War of the Grand Alliance (1688-97) earned him his promotion to flag rank. Then, in 1702 he led a squadron to the West Indies, in an attempt to intercept a Spanish Treasure fleet. Instead he encountered a French squadron off the coast of Hispaniola. In the ensuing action Benbow was hit by a chainshot, whoch all but severed his leg. After having hos wounds dressed, he returned on deck, and supervised the rest of the battle. He died three months later, not from his wounds, but from melancholia. His exploit was remembered in Brave Benbow, a popular song of the 18th century.

Cornelis Jol (1597-1641)

This Dutch captain served the Dutch West India Company as a privateer, and during the 1620s and 1630s he led several expeditions against Spanish and Portuguese settlements in Brazil and the Caribbean. His leg was amputated following a land battle with the Portuguese on the island of Fernando de Norhona on 1631, and consequently his men gave him the nickname Houtebeen (Pegleg). By 1639 he had become a rear admiral, and his squadron helped defeat the Spanish in the battle of the Downs 1639. He died of malaria off the West African coast while trying to seize the island of Sao Tomé from the Portuguese.

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mejores destinos para los Hijos de los Reyes Católicos- María de Aragón

María fue la hija mas desconocida de los Reyes Católicos siendo considerada bonita, pero no tanto como sus hermanas. La infanta era piadosa, caritativa y prudente ante todos los conflictos que estuvieron ocurriendo en la familia Trastamara.

En un principió se pensó en comprometerla con el rey James IV de Escocia, pero las negociaciones matrimoniales no llegaron a mucho y el rey se acabaría casando con la princesa Margarita Tudor.

Tras su compromiso fallido, su hermana mayor la reina de Portugal Isabella de Aragón negocio un matrimonio para María con el duque de Viseu y Beja, Manuel de Avís que era hermano de la reina viuda Leonor de Viseu.

Manuel de Viseu no estaba muy convencido por aquella unión debido a que el tenia sentimientos escondidos por la reina Isabella, pero accedió a casarse con la infanta para asegurar la sucesión de sus ducados.

Las negociaciones matrimoniales apenas duraron un año al ser Isabella de Aragon la mediadora de aquel compromiso y María partió hacia Portugal en 1500 llegando hasta la ciudad de Alcácer do Sal donde se celebro la boda.

Manuel y María se enamoraron a primera vista durante la ceremonia. Manuel llego a considerar a su esposa como “una flor hermosa, delicada y pequeña” e incluso llego a agradecer por carta a la reina Isabella de Aragón por haber formado aquella alianza ya que de esa forma conoció a su gran amor.

María fue nombrada Duquesa consorte de Viseu y Beja tras casarse con Manuel. La pareja viajo al ducado de Viseu donde fueron bien recibidos nada mas entrar y María fue aclamada por todo el mundo.

Los reyes de Portugal les otorgaron como regalo de bodas los títulos de duques de Trancoso, Guimarães y una parte del ducado de Guarda, siendo los primeros Duques del ducado Guarda-Viseu.

En el ducado se celebraron sencillos, pero bellos bailes en honor a la nueva duquesa y también se llevo a cabo un torneo de justas donde participo Manuel. Se dice que el duque paro su montura ante su esposa y le dio una rosa roja como símbolo de su gran amor y pasión, lo que provoco que María fuera llamada por los nobles y el pueblo como “La rosa de Viseu”.

María se quedo embarazada casi dos años después de casarse con su marido y alumbro en 1502 a su primer hijo, Juan que sería Duque de Viseu.

Pese a que al principio se creía que la duquesa tenia problemas de fertilidad, ella acabaría dándole a su marido 10 hijos seguidos:

Juan de Viseu (1502-1554) Fue duque de Viseu y miembro del consejo del rey Juan III de Portugal. El duque se caso con su prima, Catalina de Austria y tuvieron 4 hijos: Manuel, Felipe, María Manuela y Juan Manuel.

Isabella de Portugal (1503-1547) Fue Emperatriz consorte del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico al casarse con su primo, Charles V y al sirvió como su regente al lado de su tía-suegra, Joanna. Isabella y Charles tuvieron 5 hijos: Philip I, Maria, Ferdinand, Joanna y John.

Beatriz de Portugal (1504-1538) Fue Duquesa consorte de Saboya al casarse con Carlos III de Saboya y tuvieron 3 hijos vivos: Manuel Filiberto I, Catalina y Isabella. Beatriz fue el tercer vástago en morir antes que su madre.

Luis de Beja (1506-1555) Fue Duque de Beja como herencia paternal. Luis tuvo distintos enfrentamientos con su hermano mayor debido a su supuesto casamiento morganático con una judía. Pese a esto Luis se casaría con su prima, Dulce de Portugal y esta le daría 5 hijos: Luisa, Ana, Luis, Alonzo y Dulce.

Fernando de Guarda (1507-1545) Fue Duque de Guarda-Viseu al dividirse una parte de estos territorios. Se caso con Guiomar Coutinho y tuvieron dos hijos: Luisa y Fernando de Guarda.

Alfonso de Portugal (1509-1548) Fue sucesivamente obispo de Guarda, cardenal, obispo de Viseu, obispo de Évora y finalmente arzobispo de Lisboa. Al morir inesperadamente en 1548 sus títulos fueron heredados a su sobrino, Don Teobaldo de Portugal que fue su estudiante.

María de Portugal (1511-1513) Falleció a los casi 2 años de edad, siendo su muerte una gran tristeza para su madre.

Enrique de Trancoso (1512-1580) Fue duque de Trancoso y miembro importante del consejo del rey Juan III. Enrique no se caso hasta el 1554 con la noble sueca, Catalina Stenbock con la cual tuvo 3 hijos: Enrique, Birgitta y Gustavo.

Eduardo de Guimarães (1515-1549) Fue duque de Guimarães. Se caso con Isabella de Braganza y tuvieron 3 hijos: María, Catalina y Eduardo de Guimarães.

Antonio (1516) Falleció poco después de nacer.

Tras el nacimiento de su hijo Antonio y el fallecimiento de este, María se negó a traer mas hijos al mundo y verlos morir antes que ella. Esto fue aceptado por Manuel que se mantuvo fiel a su esposa pese a no volver a compartir el lecho.

María fue una madre dedicada y amorosa dejando una gran huella en sus hijos que siempre guardaron buenos recuerdos de su progenitora.

La duquesa no se entrometió en la política portuguesa, aun que llego a recibir a los distintos embajadores extranjeros que visitaban el ducado y se dice que María dejaba una buena impresión, además de tener un perfecto portugués a la hora de entablar conversaciones con los visitantes.

También fue una mujer muy piadosa y ayudo a diferentes conventos, organizaciones religiosas y monasterios a fundar sus propias escuelas o edificios santos.

María sufrió mucho con las muertes de algunos de sus hijos que fallecieron antes que ella y su marido. Su hija Beatriz falleció debido a la tuberculosis en 1538 y María guardo luto por su hija por año, además de permanecer unos meses en la corte saboyana junto a sus nietos, hijos de Beatriz.

Otro de sus hijos fue Fernando que falleció tras varios días de padecer viruela en 1545.

María llevo estas muertes como pudo, pero en el año 1547 falleció su hija mayor, Isabella tras un cáncer de mama y dos meses después su marido murió debido a una arritmia cardiaca. Estas muertes fueron un gran dolor para María que se refugió en la religión al igual que sus hermanos.

También solía visitar el Sacro Imperio para ver a sus nietos los archiduques y visito a su hermana mayor, Juana en su residencia de Tordesillas y ambas se consolaban ante las perdidas que iban pasando cada una.

Su hijo Alfonso fallecería inesperadamente en 1548 y María se mantuvo al lado de su hijo que falleció en sus brazos. La muerte de su hijo la marco de por vida y se resguardo aun mas en la religión, llegando a usar prendas mas aptas de una monja en vez de una duquesa o viuda.

María empezó a sufrir graves problemas de corazón a inicios del 1549 y permaneció en cama por varios meses hasta que falleció unos días antes de cumplir los 67 años de edad en Portugal. Su muerte fue muy sentida por los nobles leales al ducado de Viseu y Beja, pero también fue bastante dolorosa para sus hijos que siempre mantendrían un especial recuerdo de ella.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Best destinations for the Children of the Catholic Monarchs- María of Aragón

María was the most unknown daughter of the Catholic Monarchs, being considered pretty, but not as pretty as her sisters. The infanta was pious, charitable and prudent in the face of all the conflicts that were occurring in the Trastamara family.

At first, it was thought of committing her to King James IV of Scotland, but the marriage negotiations did not go to much and the king would end up marrying Princess Margaret Tudor.

After her failed engagement, her older sister, the Queen of Portugal Isabella of Aragón, negotiated a marriage for María with the Duke of Viseu and Beja, Manuel of Avís, who was the brother of the widowed queen Leonor of Viseu.

Manuel of Viseu was not very convinced by that union because he had hidden feelings for Queen Isabella, but he agreed to marry the infanta to ensure the succession of her duchies.

The marriage negotiations barely lasted a year as Isabella of Aragon was the mediator of that engagement and Maria left for Portugal in 1500 reaching the city of Alcácer do Sal where the wedding took place.

Manuel and María fell in love at first sight during the ceremony. Manuel came to consider her wife as "a beautiful, delicate and small flower" and even came to thank Queen Isabella of Aragon by letter for having formed that alliance since in that way he met her great love.

María was named Duchess consort of Viseu and Beja after marrying Manuel. The couple traveled to the Duchy of Viseu where they were well received as soon as they entered and Maria was acclaimed by the whole world.

In the duchy, simple but beautiful dances were held in honor of the new duchess and a jousting tournament was also held where Manuel participated. It is said that the duke stopped her mount before her wife and gave her a red rose as a symbol of her great love and passion, which caused Mary to be called by the nobles and the people as "The rose of Viseu ”.

María became pregnant almost two years after marrying her husband and gave birth to her first child, Juan, who would be Duke of Viseu in 1502.

Although at first it was believed that the duchess had fertility problems, she would end up giving her husband 10 children in a row:

John de Viseu (1502-1554) He was Duke of Viseu and a member of the council of King Juan III of Portugal. The duke married his cousin, Catherine of Austria and they had 4 children: Manuel, Felipe, María Manuela and Juan Manuel.

Isabella of Portugal (1503-1547) She was Empress consort of the Holy Roman Empire by marrying her cousin, Charles V and serving as her regent alongside her aunt-mother-in-law, Joanna. Isabella and Charles had 5 children: Philip I, Maria, Ferdinand, Joanna and John.

Beatrice of Portugal (1504-1538) She was Duchess consort of Savoy when she married Carlos III of Savoy and they had 3 living children: Emmanuel Philibert I, Catherine and Isabella. Beatriz was the third child to die before her mother.

Louis of Beja (1506-1555) He was Duke of Beja as a paternal inheritance. Luis had different confrontations with his older brother due to his supposed morganatic marriage to a Jewess. Despite this, Luis would marry his cousin, Dulce de Portugal and she would give him 5 children: Louise, Anna, Louis, Alonzo and Dulce.

Ferdinando of Guarda (1507-1545) He was Duke of Guarda-Viseu when part of these territories were divided. He married Guiomar Coutinho and they had two children: Luisa and Fernando of Guarda.

Alfonso of Portugal (1509-1548) He was successively Bishop of Guarda, Cardinal, Bishop of Viseu, Bishop of Évora and finally Archbishop of Lisbon. When he died unexpectedly in 1548, his titles were inherited to his nephew, Don Teobaldo de Portugal, who was his student.

María of Portugal (1511-1513) she died when she was almost 2 years old, her death being a great sadness for her mother.

Henry of Trancoso (1512-1580) He was Duke of Trancoso and an important member of the council of King Juan III. Enrique did not marry until 1554 with the Swedish noblewoman, Catherine Stenbock with whom he had 3 children: Enrique, Birgitta and Teobaldo.

Duarte of Guimarães (1515-1549) He was Duke of Guimarães. He married Isabella de Braganza and they had 3 children: María, Catherine and Duarte of Guimarães.

Antonio (1516) died shortly after birth.

After the birth of her son Antonio and his death, María refused to bring more children into the world and see them die before her. This was accepted by Manuel who remained faithful to his wife despite not sharing the bed again.

María was a dedicated and loving mother leaving a great mark on her children who always kept good memories of her mother.

The Duchess did not interfere in Portuguese politics, although she did receive the various foreign ambassadors who visited the duchy and it is said that Maria left a good impression, in addition to having perfect Portuguese when it came to engaging in conversations with visitors.

She was also a very pious woman and helped different convents, religious organizations and monasteries to found their own schools or holy buildings.

Maria suffered greatly with the deaths of some of her children who died before her and her husband. Her daughter Beatriz hers died due to tuberculosis in 1538 and María kept mourning for her daughter for years, in addition to staying a few months at the Savoyard court with her grandchildren, Beatriz's children.

Another of her children was Fernando, who died after several days of suffering from smallpox in 1545.

María carried these deaths as she could, but in the year 1547 her eldest daughter Isabella died after breast cancer and two months later her husband died due to a cardiac arrhythmia. These deaths were a great pain for Mary that she took refuge in religion like her brothers.

She also used to visit the Holy Empire to see her grandchildren, her archdukes, and she visited her older sister, Juana, at her residence in Tordesillas and they both consoled themselves for the losses that each one was going through.

Her son Alfonso hers would die unexpectedly in 1548 and María remained by the side of her son who died in her arms. The death of her son marked her for life and she sheltered herself even more in religion, coming to wear more suitable garments of a nun instead of a duchess or widow.

María herself began to suffer serious heart problems in early 1549 and she remained in bed for several months until she passed away a few days before reaching 67 years of age in Portugal. Her death was deeply felt by the nobles loyal to the Duchy of Viseu and Beja, but it was also quite painful for her children who would always keep a special memory of her.

#maria of aragon#manuel of portugal#john of portugal#isabella of portugal#beatrice of portugal#henry of portugal

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apuntes de la parte 2

Aliados

Bárbara de Braganza

Fernando VI

Pedro Padilla (Enlace con el Ministerio)

Florinda La Cava (Agente, sección códigos y cifrados)

Salai (Agente perdido en el tiempo)

Pío Baroja (Agente de patrulla, médico y escritor)

Pepa La Loba (Agente caída en desgracia)

Blas de Lezo (Agente caido en desgracia)

Neutrales o no conocen la existencia del Ministerio

Paca

Antonio Machado (Profesor de Francés, no conoce la existencia del Ministerio)

Pilar de Valderrama (No sabe para quién trabaja)

Mentes pensantes

Juana de Austria (Hija de don Juan de Austria, espía, enemiga)

Isabel de Borgia (Infiltrada en tiempos actuales, primera linea de batalla contra el Ministerio)

Ana María de Austria (Hija de don Juan de Austria, espía, enemiga)

*Antonio Pérez (Antiguo secretario de Felipe II)

Enrique (Anomalía histórica)

#Guess who is back#emdt#emdt next generation#my fic#yo lesba#se va a liar se va a liar#crossover casa de papel#apuntes

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun facts about Philip II of Spain, his family members and their relationship

Philip and his sisters María and Juana were very close, and relied on each other greatly even when being apart. Both sisters acted as regents of Spain during Philip’s absences: María - from 1548 to 1551, Juana - from 1554 to 1559.

They had two recognised illegitimate siblings - half-sister Margaret of Parma and half-brother Don Juan of Austria. About the latter's existence Philip found out only after the death of their father who had kept it in secret.

María spied on her husband on Philip's behalf.

Philip opened and copied his wife Elisabeth de Valois’s letters to her mother Catherine de Medici.

Philip wasn't fond of his aunt Mary of Hungary but felt great affection for uncle Ferdinand. Juana liked neither Mary of Hungary nor Eleonor of Austria - once after their visit she wrote to Ruy Gómez that they were the worst company and she is glad that they are gone.

Charles often criticized his youngest daughter Juana and treated her harshly. He described her as very haughty and accused of leading a disorderly life, opposed her candidature as regent of Spain, ordered her to leave the court after Philip’s departure from Spain in 1548 and forbade to see Maria, and refused to receive her when he lived on retirement in Yuste.

Philip attended the births of at least three of his children - Isabel Clara Eugenia, Catalina Micaela and Fernando.

Philip and Elisabeth named their eldest daughter after St Eugene because they believed that they had conceived her at night after Elisabeth had venerated the relics of the saint.

Margaret of Parma together with her son Alessandro visited Philip in England and spent a few weeks there in 1557. Her son was to lead the army of Flanders to invade England in 1588.

Source: Felipe II: La biografía definitiva by Geoffrey Parker

#Philip II#Philip II of Spain#Charles V#Maria of Austria#Juana of Austria#Elisabeth of Valois#Margaret of Parma#Mary of Hungary#Eleonor of Austria#Alessandro Farnese

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Retrato ecuestre del Cardenal-Infante don Fernando de Austria

atrrib. to Diego Velázquez (Sevillian, 1599 - 1660)

17th century

unknown collection

from Archivo Español de Arte, No. 330 (2010)

#647302873467715584/YiQh5On1#Diego Velázquez#House of Habsburg#Monarquía Hispánica#Spanish Empire#Spanish Netherlands#17th century#Baroque#Real Sitio del Buen Retiro#equestrian portrait#portraits#paintings

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ISABEL DE PORTUGAL: La muerte del Infante Fernando

El tercer hijo de Carlos e Isabel nació en Madrid el 22 de noviembre de 1529. El emperador no llegará a conocerle. En esos momentos se hallaba en Bolonia, preparando su solemne coronación. El parto tiene lugar sin excesivos problemas, y nace un niño hermoso y robusto. Isabel hace gala de su dominio del dolor, como en los anteriores alumbramientos. Y pide, igual que otras veces, que la habitación donde ha de tener lugar el parto quede en penumbras. Nadie ha de advertir los gestos de dolor reflejados en su rostro. Eso era contrario a su sentido de la dignidad regia. Al niño se le impuso el nombre de Fernando en recuerdo de su abuelo, entre grandes demostraciones de júbilo y entusiasmo popular. La sucesión se veía reforzada con este nacimiento, era un nuevo varón. En Bolonia, cuando Carlos tuvo la noticia, a primeros de diciembre, se festejó su nacimiento con solemnes actos litúrgicos y grandes fiestas cortesanas.

En cuanto Margarita de Austria tuvo noticia de este nacimiento, escribió una carta a la emperatriz dándole la enhorabuena, recordándole la promesa que tenía de Carlos V de enviarle al infante y le promete que ella animaría al emperador a que volviese pronto a España y cumpliese de nuevo como marido. La gobernadora de los Países Bajos le pedía a Isabel que le mandase a su hijito recién nacido para criarlo y educarlo ella en su corte de Malinas, a cambio de ello intentaría lograr que su sobrino volviera al lecho conyugal. Sin embargo, a la alegría por el nuevo nacimiento seguiría muy pronto la tristeza por su temprana e injusta desaparición. Algunas fuentes indican que el pequeño infante falleció el 14 de julio de 1530, cuando aún no había cumplido el año de vida. La crónica de Pedro Girón lo recoge de este modo:

Este año, a principios dél, estuvo la emperatriz en la villa de Madrid y estando allí dio al infante don Fernando una enfermedad que llaman las mujeres alferecía, que son unos temblores y desmayos que acaban los niños en poco tiempo, y ansí hizo a este infante, que no duró un día natural.

Y aún nos aporta más datos, como la gran fortaleza moral de Isabel, pese a su sentimiento de dolor, que inició inmediatamente sus actividades habituales de gobierno, sobreponiéndose a su tristeza, aunque no tardó en sufrir unas pertinaces tercianas que la obligaron a posponer reuniones y decisiones. Carlos V recibió la noticia de la muerte de su hijo en Augsburgo y desde allí mandó sus condolencias a su esposa a finales de julio:

El fallecimiento del infante nuestro hijo habemos sentido, como era razón, pero pues Nuestro Señor, que nos lo dio, lo quiso para sí, debemos conformarnos con su voluntad y darle gracias y suplicarle que guarde lo que queda, y así os ruego a vos, señora, muy afectuosamente que lo hagáis y olvidéis y quitéis de vos todo dolor y pena, consolándoos con la prudencia y ánimo que a tal persona conviene.

Fuentes:

Villacorta, Antonio. La Emperatriz Isabel. Editorial Actas 2009

Alvar Ezquerra, Antonio. La Emperatriz. La Esfera de los Libros 2012

#Isabel de Portugal#Isabella of Portugal#Spanish history#Fernando de Austria#Ferdinand of Austria#Infante of Spain#Carlos V#Charles V#Margaret of Austria#Margarita de Austria

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

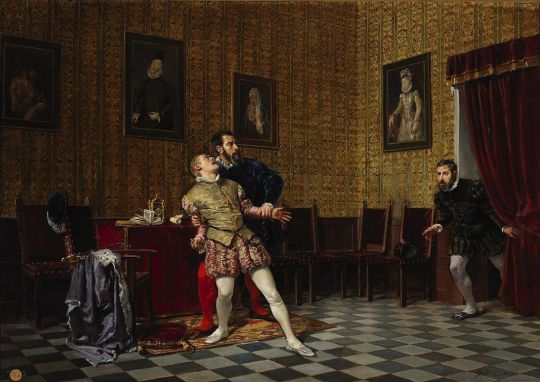

CARLOS

Prince of Asturias

(born 1545 - died 1568)

pictured above is a portrait of the Prince of Asturias, by Alonso Sánchez Coello from 1567

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

SERIES - On this day July Edition: Carlos died on 24 July 1568.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

CARLOS was born in 1568, at Valladolid in Spain. He was the only child of Felipe, Prince of Asturias and his first wife Infanta Maria Manuela of Portugal, who died twelve days after giving birth to him.

Thus he was a member of the Spanish branch of the HOUSE OF HABSBURG. And as a son of the Spanish heir he was from birth an INFANTE OF SPAIN.

In 1556 his grandfather Carlos I, King of Spain (who was also Karl V, Holy Roman Emperor) abdicated and was succeeded in Spain by the Infante's father as King Felipe II.

By 1559 he was betrothed to Princess Élisabeth (of Valois) of France but his father changed plans and decided he would himself marry her. And in 1560 he was made PRINCE OF ASTURIAS by his father.

Throughout his life he suffered from poor health and probably mental illness that were likely aggravated do to his ancestors inbreeding, giving that his parents were first cousins by both sides and he had only four great-grandparents.

The relationship between him and his father was never easy as the King disapproved of his son's behavior, that was probably worse do to his mental instability. While he pushed to be given more administrative power, which his father did not will to concede.

After an accident in 1562 his behaviour worsened and in 1567 he attempted to murder various people, including Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba and his father's illegitimate brother Don Juan of Austria (born Gerónimo).

pictured above is a painting depicting one of the crisis of the Prince of Asturias featuring the Duke of Alba, by José Uría y Uría from 1881

So, by January 1568 the King determined his "arrest", confining him to his rooms in the Royal Alcázar of Madrid. He also ordered that all potential weapons to be seized and for the windows to be blocked.

In just five months of confinement the Prince of Asturias died aged only 23, on 24 July 1568. He never married or had any children.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

At the time of his death he was his father's only male son. And as his stepmother (and former fiancée) Princess Élisabeth also died months after him, without giving his father any other sons, King Felipe II rushed to get married again to try to produce another heir.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

If he had lived a longer life he would have probably succeeded to the Portuguese throne following the Succession Crisis of 1580, as he had a better claim than his father who became Felipe I, the new King of Portugal.

the Prince of Asturias' mother was the eldest daughter of João III, King of Portugal, brother of Cardinal Henrique, the last King of Portugal from the House of Aviz;

while King Felipe II's mother was the eldest sister of King João III and the Cardinal-King Henrique.

-------------------- ~ -------------------- ~ --------------------

As the Habsburgs continued their tradition of inbreeding, marrying to very close relatives such as cousins, uncles and nieces, their genetics worsened over the centuries, specially in the Spanish Royal Family.

That is the probable reason for the extinction of the Spanish Habsburgs male line by the end of the 17th century, when Carlos II, King of Spain died childless. He also suffered from poor health like his great-uncle Carlos, Prince of Asturias, though the King lived a little longer then the Prince.

#carlos of austria#carlos de austria#carlos prince of asturias#carlos príncipe de astúrias#prince of asturias#príncipe de astúrias#habsburg#house of habsburg#spanish habsburgs#spanish royals#spanish royal family#royals#royalty#monarchy#monarchies#royal history#spanish history#european history#world history#history#history lover#16th century#charles v#philip ii#history with laura

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniel Marín Arribas: "Juan de Mariana es prototipo del antimodernismo de la Cristiandad Hispana"

Daniel Marín Arribas presenta por quinto año consecutivo (2015-2020) su sexta iniciativa en la campaña que lleva realizando desde hace más de un lustro para dar a conocer a los maestros católicos de la llamada Escuela de Salamanca.

En 2015, después de varios años estudiándolos y aprendiendo con ellos, en lo que supuso incluso un proceso personal muy arraigado de conversión a la Fe Católica, presentó el «Decálogo Antimodernista de la Escuela de Salamanca». Un año después, en 2016, paseó por las calles de su “amada” Salamanca para dar a la luz junto con la productora Agnus Dei el documental más visto en YouTube y también solicitado en DVD sobre la materia: «Escuela de Salamanca. Defensores de la Fe». En 2017 culminó junto con un amigo suyo la traducción del libro The Church and the Libertarian del jurista norteamericano Christopher A. Ferrara, cuya edición hispana añade un extenso e interesante apéndice de su autoría: «La Iglesia, el Liberalismo y la Escuela de Salamanca». Esta obra fue durante meses primera en ventas de la editorial última línea y, azares del destino, estuvo firmándola en la Feria del Libro de Madrid justo enfrente de la caseta de la liberal-libertaria Unión Editorial. En 2018 tampoco se quedó atrás, y aprovechando la señalada fecha del VIII Centenario de la Universidad de Salamanca terminó otro libro, prologado por el vicerrector de la Universitat Abat Oliva CEU, el dr. Javier Barraycoa: «Destapando al Liberalismo. La Escuela Austriaca no nació en Salamanca». Entre ese mismo año y el siguiente, presentó su trabajo en numerosas ciudades de España; Salamanca, Palencia, Sevilla, Gerona, Barcelona, Madrid… gracias a la generosa acogida de diversas parroquias, centros culturales y asociaciones, que quisieron dar en el centenario indicado una nota de verdad al bulo liberal de que Francisco de Vitoria y sus discípulos fueron la génesis de su ideología modernista. Y hablando de Vitoria, volvió al asalto en la Navidad de 2019 con una original campaña organizada en colaboración con SND Editores, en la que colocó una enorme cartelera publicitaria al lado de la madrileña universidad Francisco de Vitoria (UFV) que rezaba: «Francisco de Vitoria sería Anti-Liberal».

Desde estudios publicados en libro, hasta entrevistas, documentales, e incluso estampitas y vallas de publicidad, este profesor y economista madrileño ha venido demostrando un amor y una pasión hacia sus autores muy especial y difícilmente vista. Asisto a su despacho, que lo preside un enorme cuadro de Francisco de Vitoria O.P. pintado a mano por una artesana de Castel Gandolfo, Roma, al que acompaña otra obra de Francisco Suárez S.I. y otra de Juan de Mariana S.I., entre diversos elementos salmantinos. Me recibe perfectamente trajeado, en cuya camisa cuelga una corbata de Mariana, amarilla con las imágenes de su busto. Precisamente este año 2020 le toca el turno al jesuita talaverano, con un libro que ya sale de imprenta: «Juan de Mariana y la Defensa de la Cristiandad Hispana». Y lo hace en día tan señalado como es el del Papa San Pío V, el pontífice más importante del siglo XVI, época de nuestra áurea escolástica.

Un libro que nace fruto de un congreso sobre el Imperio Español…

En efecto, el profesor Álvaro Silva Soto tuvo la amabilidad de invitarme como ponente al congreso que organizó en la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos de Madrid, Desde donde sale el Sol hasta el ocaso, con motivo del V Centenario de la primera vuelta al Mundo, para reflexionar sobre el Imperio Español. Fue una oportunidad que me permitió y animó a ponerme a la tarea que llevaba ya un tiempo en proyecto: escribir sobre el padre Juan de Mariana como prototipo del ser hispano. Me dio entera libertad de cátedra, tan poco acostumbrada en un ambiente universitario que cada vez se ensombrece más en el sectarismo de las ideologías modernas, y pude exponer lo que pocos académicos se dignan a señalar hoy en día, que la Hispanidad es Cristiandad o no es, y que nuestro jesuita encarnó en su persona y en su doctrina este carácter profundamente católico y profundamente castellano.

La España liberal se construye como un proyecto secularizado, muy contrario a lo que usted acaba de defender mediante la figura de Juan de Mariana…

La España liberal es un fracaso. Fracaso antecedido por la España absolutista, que consolidaron los Borbones y comenzó a plantar la dinastía de los Austria, y al que sucede la herencia del socialismo y comunismo abiertamente bélicos. No son casuales, episodios como la Sublevación de los Comuneros, el Motín de Esquilache, el Levantamiento del 2 de mayo, las Guerras Carlistas, o el Alzamiento Nacional, por citar algunos ejemplos. Son pasajes de un pueblo libre negado a morir, con un fuerte componente patriótico, y por patriótico, religioso, ante una amenaza extranjerizante.

El avance de la secularización ha traído lo que directamente el profesor Alberto Bárcena ha titulado en su último libro de historia, la pérdida de España. Diezmada en su territorio y en su unidad por las independencias y los independentismos nacionalistas -liberales y socialistas-; diezmada en su soberanía, antaño por dinastías extranjeras al servicio de sus intereses familiares, y hogaño por la antigua sovietización y actual europeísmo; diezmada también en su economía por la esclavitud a la usura internacional y al capitalismo apátrida; diezmada igualmente en su religión por decretos tan variados como la entonces expulsión de la Compañía de Jesús o la supresión del Tribunal del Santo Oficio, o las actuales persecuciones en forma de matanzas directas o mordaza pública; y diezmada en su carácter y su moral por el libertinaje liberal y la degeneración de las costumbres, que están destruyendo el último pilar en pie, que es la familia; España materialmente ya no es ni por asombro ese Imperio donde nunca se pone el Sol, pionera en artes y ciencias, descubridora de nuevos continentes… La España absolutista, liberal y socialista es un fracaso, un cúmulo de errores doctrinales, leyes tiránicas e ingeniería social que arrebataron a un pueblo vigoroso su territorio, su soberanía, su economía, su religión, su carácter y su moral.

La unidad nacional, la potencia integradora de sus regiones libres (¡las Indias no eran colonias!), la verdadera representación tradicional con mandato imperativo y juicio de residencia coronada bajo una unidad de mando monárquica, la sociedad de clases medias y propietarios que trabajan para el bien común, la Fe que sostiene la vida del espíritu, más importante que la de la carne, y el vigor de la palabra dada, el calor familiar, el apoyo mutuo, y el cariñoso cuidado de la vida humana desde su concepción hasta la muerte natural, nada tiene que ver con el caos, la división, la esclavitud, la muerte, la desesperanza y el conflicto permanente que han ido sembrando los reyes y las democracias absolutistas en el correr de los últimos siglos. Y Juan de Mariana ya avisaba en las primeras fases del desastre…

¿Juan de Mariana fue una especie de profeta de la decadencia?

Hay que tener en cuenta que nuestro sacerdote jesuita es uno de los historiadores de España más tradicionales y destacados. Sabía lo que era España, a lo que se sumaba un enorme amor por ella. Quería, nos relata Jaime Balmes en un artículo sobre Mariana, «que el trono salido de Covadonga, se asentase sobre cimientos sólidos y anchurosos: la religión, la justicia, las libertades antiguas». Y vio que en su época esto se torcía preocupantemente, perdiéndose el precioso legado que dejaban doña Isabel y don Fernando. Balmes sigue relatando: «En cuanto a España, al ver el ascendiente que iban tomando los privados, y esa dejadez en que se sumía el gobierno, y que por desgracia se hizo hereditaria, levantábase su pecho con generosa indignación, temiendo, no sin motivo, que así se oscurecía nuestra gloria, se enflaquecía nuestra pujanza, y vendría al suelo toda nuestra grandeza. ‘Grandes males nos amenazan’, decía».

No se equivocó; esos males se han ido materializando, con vulneraciones flagrantes de la religión, la justicia y las libertades antiguas que han oscurecido nuestra gloria, enflaquecido nuestra pujanza y tirado al suelo nuestra grandeza. Todo ente se perfecciona atendiendo a su ser, a su forma de ser; lo contrario es su destrucción. De ahí se explica que en la Modernidad, configurada como antónimo de la Cristiandad, hayan progresado países forjados por el gnosticismo y la masonería, como Estados Unidos, y la Hispanidad y sus regiones hayan ido hundiéndose en la decadencia. No, no es la extracción y el comercio del oro de hace siglos lo que hoy supuestamente condena a las Indias a la pobreza material; y tampoco no ser suficientemente arios y modernistas europeos lo que hace a la península ibérica ir a remolque del mundo “desarrollado”… es la pérdida de la unidad territorial, la soberanía, la potencia económica, la Fe, el carácter y la moral. De nuestra identidad… nuestra hispanidad común como hecho diferencial del liberalismo anglosajón y franco, del socialismo germánico y del comunismo ruso y chino; hispanidad heredera del filósofo griego, del jurista romano y de la religión cristiana insertados en una diversidad local enormemente rica y preciosa que da iluminación a ese mosaico armónicamente entitativo, es decir, uno en sustancia y plural en sus partes. Hispanidad, de la que Juan de Mariana es prototipo y encarnación.

Hay liberales que se apropian del nombre de Juan de Mariana y le reclaman como base de inspiración de su ideología laicista…

Permítame una mueca mordaz con una pequeña dosis de indignación ante quienes así obran… Resulta irónico que un sacerdote como Mariana vea colgado su nombre en una república atea como la francesa o en un instituto liberal-libertario español que se precia de defender «la libertad como un fin ético en sí mismo». Un sacerdote que enseñaba al rey Felipe III en su obra Del Rey y de la Institución Real que «no admitas otra religión que la cristiana», y que criticaba en su Historia General de España el pluralismo religioso y de principios como de excesiva «grande libertad». Sobre la tan denostada Inquisición se expresaba en los siguientes términos: «Suerte y venturosa para España fue el establecimiento que por este tiempo se hizo en Castilla: de vn nuevo, y santo Tribunal de juezes severos, y graves, á proposito de inquirir, y castigar la heretica parvedad, y apostasia». Y en cuanto a los espectáculos, llamando a enmarcarlos dentro de los cauces del bien moral, se quejaba de que «la licencia y libertad del teatro (…) no es sino una oficina de deshonestidad y desvergüenza, donde muchos de toda edad, sexo y calidad se corrompen, y con representaciones vanas y enmascaradas aprenden vicios verdaderos».

¡Qué contraste tiene esto con esos liberales que cuelgan su nombre en chiringuitos en los que defienden la legalización abierta de las drogas, la prostitución o el aborto, promueven o permiten la televisión basura, al tiempo que con violencia verbal y/o física callan las bocas de sacerdotes, religiosos y laicos que vienen a advertir lo mismo que nuestro jesuita! ¡Ellos, que careciendo de lo que presumen, luego actúan como rigurosos e inicuos censores para la implantación de un pensamiento único, lesivo en las personas, sus familias y sus comunidades!

Un liberal no apoyaría la unidad católica en un país de mayoría cristiana, un liberal no apoyaría el restablecimiento del Tribunal del Santo Oficio, -en cuyo siglo de auge, por cierto, España logró su mayor florecimiento cultural-, un liberal no apoyaría la moderación de obras, películas, series, espectáculos y otras ofertas “culturales” que dañen bienes morales tales como la castidad, la honestidad, la templanza, y cualesquiera otras sanas costumbres; el padre Juan de Mariana, sí.

¿Y en economía sería un autor liberal?

Hay algunos que pretenden dividir muy equivocadamente el ámbito económico del resto, y alegan que en economía Juan de Mariana sí sería liberal. Ejemplo de ello encontramos a uno de los referentes de finales del siglo XX del liberalismo económico español, el profesor Lucas Beltrán. Sin mencionar las cuestiones más “espinosas” del jesuita, centran su punto en la crítica que hace a la adulteración indiscriminada de la moneda. Y esto es cierto, Mariana, como en otros aspectos, nunca apoyó nada “indiscriminado”. Todas las realidades deben regirse por el orden querido por Dios, la moneda tampoco está exenta. El buen gobernante debe velar por que el dinero cumpla sus papeles naturales, definidos ya desde Aristóteles. Uno de ellos es el depósito de valor. Una moneda sometida a devaluación y sobrevaluación constante es una mala moneda, que debe ser regulada…. por el gobernante.

Este punto, por ejemplo, no lo cuentan los liberales. Mariana no estaba pensando en un sistema financiero de bancos centrales, propios de la era liberal, que prestan su dinero a usura, por mucho que estén sometidos a un patrón oro o reglamentación rigurosa. Respecto al patrón oro, contempló incluso la posibilidad de acuñar papel moneda, y en cuanto a la potestad regulatoria, correspondía al Rey, no a un banquero.

Otra cuestión que podría mencionarse es la de la propiedad privada. El liberal en su modelo de sociedad de “individuos libres e iguales” tiende a idolatrarla por encima del pobre. Para Mariana y los escolásticos hispanos la propiedad privada es recomendable tras el pecado original, pero siempre debe estar sometida al bien común y alcanzar en su reparto «una bien entendida medianía». No es otra cosa que el destino universal de los bienes de la Doctrina Social de la Iglesia, que aspira a una sociedad de propietarios y clases medias, que el capitalismo destruye con su armazón de grandes corporaciones, usura legal, jornadas laborales eternas, y prevalencia del accionista especulador frente a los trabajadores que sacan día a día adelante la empresa. Juan de Mariana no compartía una sociedad proletarizada donde una pequeña minoría copase la mayoría de la riqueza material: «Quiere pues Dios, y está determinado por sus leyes, que ya que corrompida la naturaleza humana ha debido procederse á la partición de bienes comunes, no sean unos pocos los que los ocupen y se consagre siempre una parte al consuelo de los males del pueblo».

Para ello, no es el remedio el socialismo estatista, con su latente y hostil lucha de clases y dictadura del proletariado, sino la religión, la justicia y las libertades antiguas. Sencillamente, un termómetro moral y religioso que encauce por las vías de la justicia las millones de decisiones que toman en el ámbito mercantil los millones de actores, acompañado de un andamiaje de cuerpos intermedios, como gremios, sindicatos, corporaciones profesionales, y un gobierno civil que no se desentienda de lo social y actúe de manera subsidiaria.

El orden político, social y económico que uno se encuentra leyendo a Juan de Mariana S.I. es la proyección propia de la Cristiandad Hispana, no del capitalismo liberal estadounidense ni del colectivismo marxista soviético o bolivariano.

Juan de Mariana también es conocido por su tesis del tiranicidio, que parece que inspiraría a los liberales de la Revolución Francesa; ¿es cierto?

Es otro de los mitos… Que en el ambiente de aquellos asesinos haya sonado el nombre del jesuita, sólo se explica porque Mariana fue tenazmente contrario al absolutismo regio, muy dado por los monarcas franceses y la dinastía que aquí acabó reinando; además, de que su libro Del Rey y de la Institución Real fue quemado por esos mismos absolutistas en el Parlamento de París, acusado como móvil de un regicidio.

Sin embargo, lo cierto es que la doctrina del tiranicidio no es exclusividad de Juan de Mariana; la podemos encontrar en otros grandes escolásticos tomistas de la época. Igualmente, esta doctrina califica de tirano a un gobernador que actúa en contra de la ley natural y del bien común, atentados recurrentes en los regímenes modernistas. Y también, el tiranicidio no es sinónimo de revolución, pues para poder cometerse debe tener un respaldo autorizado y prudencial, no por propia autonomía de la voluntad, y siempre y cuando la nueva situación prevista no vaya a ser más caótica que la que se pretende cercenar.

Además, huelga decir que Juan de Mariana fue profundamente monárquico, decantándose incluso por la sucesión hereditaria frente a la electiva. ¿Cómo va a ser inspiración de una revolución en pos de una república democrática liberal atea un autor y una obra que ilustran los principios de gobernación de un rey, entre los cuales el principal es «servir primero a Dios»?

Por otra parte, no puedo dejar de advertir que el liberalismo individualista y el socialismo colectivista no han supuesto dos vías para abolir el absolutismo de eso que han llamado “Antiguo Régimen”. Estas dos ideologías lo único que han hecho es cambiar el absolutismo de un monarca por el absolutismo de una partidocracia. La libertad del pueblo sigue secuestrada, ahora por una oligarquía de partidos endogámica mucho peor que los caprichosos reyes absolutos. Primero, porque ya no responden por ni ante la nación, sino que están, como denunció en 2014 Mons. Reig Pla, Obispo de Alcalá de Henares, al servicio «de instituciones internacionales (públicas y privadas) para la promoción de la llamada ‘gobernanza global’ al servicio del imperialismo transnacional neocapitalista». Y segundo, porque tampoco tienen el freno personal propio de una sensibilidad religiosa arraigada.

La doctrina del tiranicidio de Juan de Mariana S.I. legitimaría in extremis su aplicación precisamente sobre los regímenes surgidos de aquella revolución de la guillotina y sus homólogos anglosajones; tiránicos por propia definición.

Entonces, ¿Juan de Mariana no sería nada liberal?

La falacia recurrente de los liberales, especialmente los denominados “católicos”, cuando hacen este tipo de burdos intentos de encontrar sus raíces en lo más genuino del pensamiento católico hispano, es la de tomar la parte por el todo. Cierto es que Juan de Mariana tiene algún aspecto doctrinal compartido con alguna postura sana de la ideología liberal. Todo mal siempre presenta alguna parte de bien. Pero es importante notar la palabra “compartido con”. Esos aspectos no se pueden sustancializar con la ideología liberal. Tal cosa no “es” liberal, sino “compartida por” los liberales. En última ratio, esas posturas sanas serían católicas, por cuanto en la Doctrina Social de la Iglesia se encuentra la Verdad íntegra de los principios, mientras que las ideologías no llegan más que a ofrecer parciales verdades en un mar de graves errores. Retomo lo último dicho: que tal cosa la pueda Mariana “compartir con” un liberal, no le hace sustancialmente liberal, ni protoliberal, ni paleoliberal, ni tantas otras sandeces que se han añadido a la palabra maldita. Al caso, Guillermo Pérez Galicia pone un ejemplo muy ilustrativo en su introducción a mi libro, Juan de Mariana, arquetipo de antiliberal: que «un gato tenga ojos y boca como tiene ojos y boca un perro, no le convierte en perro; igual que el poner huevos no convierte a una mosca en gallina».

Que Juan de Mariana estuviera en contra de la adulteración indiscriminada de la moneda, no le convierte en liberal. El todo en Mariana es el de un consultor del Santo Oficio, jesuita férreo, sacerdote recto, católico fervoroso y aguerrido patriota. Si lo que enseñó en sus libros se pudiera llevar a la práctica realmente, el liberalismo y el socialismo, con no menor saña que obró el absolutismo monárquico, censuraría sus obras en el Parlamento, y a él muy probablemente se le acusaría de integrista ultracatólico. Esos mismos revolucionarios liberales de 1789 le habrían pasado por la guillotina como sacerdote reaccionario…

¿Qué nos exhortaría Juan de Mariana a los hispanos del año 2020?

A la luz de sus obras, me aventuraría a decir que, antes de nada, volvamos los ojos a Cristo, pues Él y sólo Él es el Camino, la Verdad y la Vida para nuestra salvación individual y social. Mariana lo expresó claro: De «la majestad de la religión… depende la salud del reino».

Más recientemente el Obispo de Alcalá de Henares que mencioné antes, Mons. Reig Pla, también lo ha recordado, señalando en su homilía en la Santa Misa del cuarto Domingo de Pascua, con motivo del funeral a las víctimas del covid-19, que «España necesita volver a las aguas limpias del Evangelio. España necesita a Cristo, el Buen Pastor. El mismo apóstol exhortaba a sus oyentes diciendo: ‘salvaos de esta generación perversa’ (Hech 2, 41). Para ello, como hicieron los primeros cristianos, hemos de volver la mirada al que atravesaron. (…) Sobre la roca que es Cristo, se puede poner en pie a España».

Para poner en pie de nuevo a nuestra patria es necesario regresar a los principios que nos hicieron grandes; principios que encarnó Juan de Mariana, enfrentándose a la irreligión, la injusticia y la licencia moderna con su vida y sus obras. No tuvo miedo a la controversia en su propia Orden, a la cárcel, que padeció, o a la muerte, que tentó.

Mariana nos alentaría a que, poniendo los ojos en Jesucristo, salgamos de nuestro enorme letargo de décadas para volver a recrear las magnas gestas de nuestros antepasados, y defender nuestra más valiosa herencia, que es la Hispanidad. No me gustaría terminar sin usar sus propias palabras: «Llamamos cruel, cobarde é impío al que ve maltratada á su madre ó á su esposa sin que la socorra; y ¿hemos de consentir en que un tirano veje y atormente á su antojo á nuestra patria, á la cual debemos mas que á nuestros padres? Lejos de nosotros tanta maldad, lejos de nosotros tanta villanía. Importa poco que hayamos de poner en peligro la riqueza, la salud, la vida; á todo trance hemos de salvar la patria del peligro, á todo trance hemos de salvarla de su ruina».

Adelante, en pie, nobiscum Deus.

Gracias, Daniel Marín Arribas

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

fanfiction: before the battle

Fandom: Hetalia - Axis Powers

Pairing: Austria/Spain

Characters: Austria, Spain; mentions of Bavaria, Sweden, and the Imperial City of Nördlingen as Hetalia characters; historical figures

Rating: T

Summary: August (Julian calendar)/September (Gregorian calendar) 1634: Thirty Years’ War. Imperial and Bavarian troops are about to besiege the Protestant Imperial City of Nördlingen and its Swedish garrison. The siege gets delayed when Austria and the Imperial commander Ferdinand of Hungary learn about the arrival of the long awaited Spanish army with Spain and its commander, Don Fernando. Antonio inspires his war-weary husband with some much-needed reassurance.

Some basic information in advance:

The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), one of the most gruesome wars in the history of mankind, was prompted by a revolt of Protestant Bohemians against the dominion of Habsburg Austria. It was fuelled by increasing religious and political disagreement between Catholic and Protestant countries within the Holy Roman Empire. Soon, it transformed into a European war that was predominantly fought within the HRE. In the early 1830s, the Swedes intervened in order to support the Protestant powers in the HRE.

Nördlingen, situated to the north of the river Danube, was an Imperial City at the time. It was close to Protestant Württemberg as well as to the Catholic powers of (Further) Austria and Bavaria. Despite being Protestant itself, Nördlingen remained loyal to Emperor Ferdinand II (of the House of Habsburg) for a long time. When it was faced with a large Swedish army in 1632, the city defected to the Protestant/Swedish side—a logical decision without viable alternatives, but also one that was largely welcomed by the townsfolk.

Since their names may become a bit confusing:

Ferdinand of Hungary (1608-1657) is Ferdinand, King of Hungary and Bohemia, son of Emperor Ferdinand II who was to become Emperor Ferdinand III in 1637.

Don Fernando (1609 or 1610-1641) is Cardinal-Infante Fernando de Austria, Archbishop of Toledo, Ferdinand of Hungary’s brother-in-law. He is commonly called “Ferdinand” in English (and German) too but I wanted to avoid confusion with the other Ferdinand.

Austria’s ears hurt from the thunder of the artillery he heard in the distance. He had been suspecting he was getting an ear infection, but the pain he had felt had lessened soon after the cannonade had paused for a while two days ago. So perhaps it was just that he was feeling exhausted from this long war and tense from their preparations to take Nördlingen by storm. The background noise from the ordnance was giving him a headache on top of that.

He liked the quiet. He liked melodic sounds. Music. Not the barbaric noise of war.

It was at least some consolation that his commander actually shared his passion for music. Ferdinand was an educated person; sophisticated; more willing to compromise than his father, the Emperor—or so it seemed. War had the potential to bring out the best and the worst in people; Austria had witnessed this numerous times during his long life. He hoped it would bring out the best in Ferdinand because he found he actually liked the man. Perhaps Ferdinand had the potential to become a better ruler than his father because he seemed to understand that conflicts were never settled by crushing the enemy but always during talks with one’s former enemy.

That was, if Ferdinand lived for long enough, and if there would ever be an end to all this. After sixteen years of war, right in the middle of a siege, peace was a thing that seemed hard to imagine. But Austria needed to imagine it from time to time; needed to remember that there had always been periods of peace and periods of war before this specific war had begun. It was what gave him the energy to pull through the next day; to be the positive and reassuring figure his troops needed to see. He had never been particularly strong physically, but he made up for that shortcoming with tenaciousness, strategic thinking, and skilled fencing on horseback. It was tough, but he was able to do it.

He tried not to think about how it had to be for young people who had possibly never known anything but this war. How many sixteen-year-olds were there in their army? How was it for them? Would they become old enough to see this war end? Perhaps they would live to loathe war, and there would be a period of peace after this one had ended … whenever that might be. It was a hope Austria clung to like a drowning man.

He was interrupted in his fantasies when he sensed someone approaching him. Looking up, he saw Johann Christoph von Adelshofen, one of the colonels of his army.

“Mylord!” he called. “The Spaniards are here!”

“Oh, thank God!” Austria exclaimed. He started to move immediately, mounting his horse with an energy he hadn’t expected have in himself mere moments ago.

Together with Adelshofen, Ferdinand, and a large part of their army, Austria rode to the south of the Schönefeld, a terrain near Nördlingen where their army’s encampment was situated. His heart started to beat faster when, without even consciously intending to do so, his eyes first fell on one knight in shining armour who rode near Don Fernando, the Spanish commander.

The only reason why the Spanish armaments seemed so clean was probably because they had marched through drizzly weather not long ago. Regardless, Austria didn’t want to moderate his inward excitement at the sight of his husband. Spain was beautiful even if he seemed weary from the long ride and even if Austria spotted dark rings under his eyes as he came closer. The mere knowledge that he had come with Don Fernando’s troops sufficed to lift a weight from Austria’s heart and to inspire it with new confidence.

If he could have acted the way he wanted, he would have rushed to Spain and embraced him, but of course that wasn’t possible. Apart from the need to keep face, they also felt the need to downplay the fact that their marriage wasn’t a mere symbol for their shared ruling family, the Habsburgs. The inner circle of their rulers tended to turn a blind eye on their love because they saw it as a vehicle to strengthen the symbolic bond between their family branches. The vast majority of their armies, however—mercenaries, predominantly—were unlikely to do the same.

That was why their greeting remained cordial but formal: The inevitable Spanish kisses on the cheek; the usual courtesies; a short embrace between two warriors, clapping each other on the shoulder. It was something, at the least, but what Austria actually wanted was for him to rest his head against his husband’s shoulder while Spain held him. He wanted to forget his worries about the large Swedish army they knew was advancing on them for just a little while.

Ferdinand, Don Fernando, their commanders, and the two countries retreated to Ferdinand’s command tent where the Imperial commanders gave a short review of their current situation. They explained their maps and plans of the terrain, informing Don Fernando of their hope that Nördlingen would surrender to them before Gustav Horn and Bernard of Saxe-Weimar arrived with the grand Swedish army.

“We were getting ready to storm the city when you arrived,” Ferdinand explained to Don Fernando. “The Bavarians are going to start with that tomorrow now.” He nodded to Maximilian of Bavaria and Theodor, Austria’s brother, who had arrived a little later than the others.

“We should give them one last chance to surrender,” Austria suggested. “The situation has changed. Now they are facing many more besiegers than before. Perhaps they will be more willing to give up now.” They knew the people in the city were almost starved, and there was a disease spreading within it. Maybe they were more willing to surrender once they knew how futile their resistance was.

There was also a part in Austria that wanted to acknowledge Nördlingen had been loyal to the Emperor until he was faced with Sweden’s superior forces. He knew that, in Nördlingen’s stead, he would have done the exact same thing in order to ensure his own survival. Yes, perhaps the decision had been easier for Nördlingen because he was a Lutheran. But the fact remained that he had been loyal to him until two years ago.

“It is worth one last try,” Ferdinand agreed. “Volunteers?”

Adelshofen took one step forward. Ferdinand nodded, and the matter was settled.

Why am I not surprised? thought Austria. Somehow, it always seemed to be Adelshofen who was there when things needed to get done. He appreciated that.

Austria overviewed the Bavarian siege on Nördlingen from a wooded hill. Adelshofen’s attempt to convince Nördlingen to give in had been unsuccessful, and that was why the siege had only been delayed for one day rather than getting cancelled.

“It’s not that the people of this city are unwilling to yield,” Adelshofen had told them. “It’s the Swedish garrison who won’t let them surrender. They’re expecting the Swedish army to come to their aid at any time now.”

And that was precisely why Austria was standing where he was now: To overview the siege but also to keep watch for Horn and Saxe-Weimar’s joint army. The afternoon sun was beclouded by dust from the artillery and smoke from fires at the city wall. Watching a siege was always a grim sight, and Austria knew how it was to be on the other side too; to defend his city, his heart, while cannons were hitting the houses near the wall.

Things needed to get done, he remembered his thoughts from the day before. Laying siege to Nördlingen and eventually storming it was one of these things. Sweden’s army had inflicted the south of the Empire with war, and the only way to stop that was reconquering cities held by the Swedes … and, eventually, facing them in open battle.

That last prospect scared him, but things needed to get done. He sighed. So I better be prepared.

“Rodrigo?” a voice close to him said softly. He wasn’t surprised. He had noticed Spain coming closer for a while, drawing on the strange circumstance that, in times of war, his senses seemed to sharpen themselves without his own doing.

Of course that impression wasn’t true. He had been trained to focus in these kinds of situations since he was little, but it was a thing that came back to him effortlessly, and he was glad about that.

“Antonio.” He sighed again when Spain wrapped his arms around him from behind, this time out of relief. “It’s good to have you here. You shouldn’t have come, but I’m glad you did.”

“There was so little time yesterday,” Spain whispered, ignoring his statement. His lips were pressing little kisses on the nape of Austria’s neck, and Austria was trembling. “I wanted to see you.” Spain’s hands started to roam over Austria’s body greedily, but the only thing he said was: “You’re way too thin.” Austria snorted.

“There’s a war going on,” he said sardonically. “What do you expect.”

“You should still try to pay more attention to your health,” Spain replied dryly. “I don’t think it will be helping matters if you faint on the battlefield out of exhaustion. You have to set a good example and fight.”

“I know that,” said Austria, trying to free himself from Spain’s embrace.

“I’m just worried,” Spain said gently, holding him more securely. “You always eat too less when you’re strung up, regardless of the supply situation.” His kisses became more firmly, extending to the base of his spouse’s neck and to his shoulder. “I just want you to be healthy, and happy.”

Austria wanted to give a bitter laugh—Happy? How could I possibly be happy now?—but he knew Spain was only trying to cheer him up. And in spite of his thoughts, he noticed his body relax into Spain’s embrace too. Perhaps it remembered the staggering love he felt for that man better than he did in this situation. He stopped looking out, turned and wrapped his arms around Spain’s shoulders, clinging to him with a force that surprised even him.

“Oh, Rodri.” Spain kissed his temple. “You’re so smart and so brave, but you sometimes forget that I’m there, too. You don’t have to push trough everything all by yourself.”

So that’s why you’ve come, Austria thought. He didn’t dare to say it because he was afraid he would start crying tears of emotion, and he didn’t want to show Spain how vulnerable he really felt. His husband had turned out to be the best thing that had happened to him in a long time, but he was also the less composed person among the two of them. He didn’t want to throw him off by starting to sob.

“You’re a godsend,” he told his husband solemnly as soon as he had brought his voice back under control. Spain avoided looking into his eyes with a sheepishness that was so adorable it made Austria smile.

“You were right though,” Spain said, still looking away.