#film noir pastiche

Note

Oh, we can’t ask anonymously anymore, dang it. Still gonna ask my question. Do you like movies? If so, do you have a favorite movie?

The amount of profanity has drastically declined since I made that decision, meaning it was a good one.

I prefer film noir pastiche above anything else.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

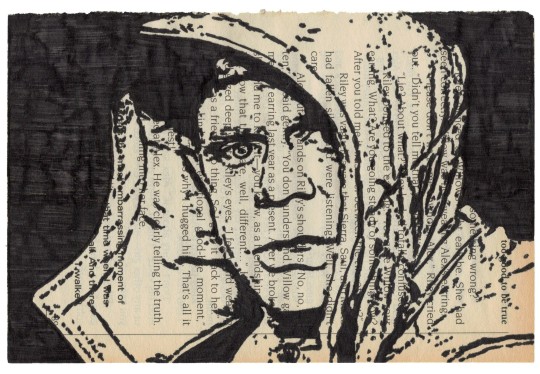

Happy National Minnesota Day cult film fans! Here's some Fargo art to mark the occasion!

#national minnesota day#minnesota#fargo#fargo 1996#neonoir movies#neonoir#black comedy movies#film noir pastiche#noir pastiche#detective film#frances mcdormand#william h. macy#peter stormare#steve buscemi#crime movies#crime comedy movies#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#pop art#modern art#pop surrealism#cult movies#portrait#cult film

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Coat, A Hat, And A Gun Department:

In a world of Film Noir tropes and curious anachronisms, where Duesenberg Model A's coexist with smartphones, and space stations run on vacuum tubes and reel-to-reel computers, Slim the Snake and his unflappable partner Doll fight a never-ending battle against crime and corruption in Big City. SLiM CHANCE! was the first in a series of seven films featuring the hard-boiled, no-fisted hero and the phlegmatic femme fatale. Are they new films that homage the past or old films that predict the future? Hard to tell, because they only exist in an alternate universe where time passes differently than in ours, so you'll never get to see them. Tough luck, kid.

© 2024 Rick Hutchins

#alternate universe#pastiche#homage#fake movie poster#fake movies#film noir#detective fiction#rick hutchins#rjdiogenes

0 notes

Text

I thought the big sleep and the big heat would similar films (b&w film noir, basically the same title) but the big sleep is basically a rom com and the big heat made me CRY FOR REAL!!!!

#debbie marsh u would have been a blorbo#the way she looks over her shoulder and SMILES as her boyfriend shoots her bc she knows she fucked his shit up irrevocably#until like a month ago my only exposure to film noir was thru pastiche#but now that i am getting into it….! the richness and diversity of the genre

0 notes

Text

We Wouldn't Have Alan Wake II Without Quantum Break

Remember Quantum Break? The first game announced for the Xbox One? The link between cult classic Alan Wake and surprising studio-saving hit Control? That prominently features Lance Reddick, the much-missed actor who was frequently one of the most electric screen presences of our time?

Don't worry, I barely do either, and I played the game yesterday.

So, a refresher. Quantum Break, announced in 2013 alongside the Xbox One and released three years later, is a third-person shooter starring Shawn Ashmore aka Iceman from the X-Men movies as Jack Joyce (and not Jake Joyce as I constantly remembered him as. In my defense, it's a better name, if only because then his superhero name could be Quantum Jake...), who, after being turned into A Remedy Entertainment Protagonist after a time-travel experiment gone wrong, battles against fellow Remedy Entertainment Protagonist Aidan Gillen aka Doctor Pavel I'm CIA as Paul Serene, over what to do about an imminent apocalypse after Time starts Breaking because of the aforementioned time-travel experiment.

As a rehabilitating former Doctor Who obsessive, I'm particularly open to this kind of time-travel nonsense, but Quantum Break is frustratingly unwilling to capitalize on its own premise. Interesting things happen, sure: people get stuck in causality loops, confront and become acausal time monsters, and live entire second lives in the past after time-traveling, but almost none of it occurs to Jack Joyce: he just spends his time just shooting guys in a series of warehouses and offices. Quantum Break is a potentially interesting story that we don't really get to see anything of, instead anything compelling in the narrative is relayed to us second-hand, by the myriad emails and documents scattered throughout the gunfights, or over the radio, and, of course, Remedy's now-signature multimedia ambitions.

In between acts of the video game Quantum Break, you'll be treated to episodes of the TV show Quantum Break, a live-action c-tier circa-2009 network TV production starring some of the big(ish) names that headline the game Quantum Break, but mostly follows a cast of extras who navigate around the events of the game while working for baddie Paul Serene's Evil Corporation, Monarch.

It's in the TV show that what Quantum Break actually is begins to take shape. Remedy, as a studio, has always been interested - and unusually adept at - pastiche, whether it's the noir comic stylings of their still-astonishing Max Payne duology or the rickety but deeply charming Stephen King love-in that is Alan Wake. And here, they do a genuinely stellar job at replicating the look, feel, and sensibilities of a 2008-2013 network TV Lost/Fringe rip-off that gets canceled after one season.

That may sound backhanded, but I assure you it isn't. I've long been a fan of Remedy, in spite of, or perhaps because I don't think they've made a truly great game since Max Payne 2. In a medium that often pillages relentlessly from Film and TV, Remedy set themselves apart from their competition with the depth of their understanding of the production of film, bringing into games a deftness of set construction and filmic pacing that blows their contemporaries out of the water. Even more-lauded names like Naughty Dog and Rockstar come up short against Alan Wake's hauntingly gorgeous misty woods, best illustrated with Rockstar's Max Payne 3, which matched Remedy's cinematographical flair in the cutscenes, but fell far short of their level design chops and breadth of influences.

Quantum Break is, in aesthetics and production, a genuinely extremely well-considered pastiche of this period of sci-fi television that is now comfortably in the rear-view mirror, the time since its release having given it a real nostalgic charm that would have been dulled at the time of release. It really reminded me of the years I spent watching shows like Heroes, or Flash/Forward, shows that may not have been very good, but are intoxicatingly emblematic of their time and place, hiding just beneath the floorboards of the shows that would actually get to be remembered.

It's a shame, then, that it just fails to really compel on any level beyond appreciation for the pastiche.

Much like the gameplay, the TV episodes of Quantum Break feel almost ancillary to another, better story that we never get to see. The stars of the game feel wasted here - particularly Lance Reddick, one of my favorite actors, who steals the show every time he appears, but is given vanishingly little to do in comparison with a group of wafer-thin characters that struggle to manifest a single dimension, with relational at best connection to the concerns of the narrative. It looks like a particularly budget-strapped episode of Warehouse 13, sure, but it doesn't really feel like one, as the episodes - until the last one, which is a noticeable improvement - are shockingly paceless and devoid of the arcs that would make a singular episode of television compelling. They are, ultimately, primarily dreary, overlong, and constantly highlighting the fact that they are largely interstitial filler.

It would be wrong to accuse Remedy of not having their heart in Quantum Break, as there is too much evident passion to discount, but I do feel like they struggle to find a core to this idea, something that they truly want to explore. Whether I'm playing the game or watching the show, QB leaves everything on the surface, with nothing to really find beneath the surface. It's notable that the game is absolutely filled with constant allusions to Alan Wake - including a full-blown trailer found on a TV moments after starting the game that bears startling resemblance to the eventual plot of this year's Alan Wake II - and that the game started life as a pitch to Microsoft for Alan Wake II: one suspects that they would much rather be making that game at this moment in time than Quantum Break, or that the game is a test-bed of ideas for the studio's future, the act of throwing a thousand darts at a quantum dartboard, and seeing which ones find their mark. It's just that for this effort, precious few of them do.

And yet, the surprise is that by the end, I truly felt like Remedy was genuinely onto something with the spirit of Quantum Break's ideas, if not the execution of them. The television show is the thing that makes Quantum Break live, that marks it out as something worth remembering in a sea of slick third-person shooters with cinematic ambitions. It is the icon of the foundational belief of the Xbox One, that the future of games lay in a synthesis with television, a dead-end future that had already worn out by the time the game was actually released. What remains is little more than a gimmick, sure, but it is one that, by the end, is oddly compelling, even if most of it is terrifically boring to actually experience.

There is a genuine thrill to seeing characters in both video game graphics and live-action forms, shifting between the two seamlessly thanks to some genuinely well-realized digitized actors that still look good today, a shift that blends well with the time-space bending of the plot. Do I care about Jack Joyce, as a person? Not even slightly. Did I still grin when I saw Actual Shawn Ashmore briefly appear in the TV episodes after controlling Virtual Shawn Ashmore? Absolutely. It's the same kind of shallow thrill you get from Cheers allumni showing up for a visit in Frasier, or when the Torchwood crew talk around the presence of Mr. Doctor Who, Esq, but as something that works with what the game is doing rather than distracting your attention elsewhere.

The gameplay portions represent time breaking down with (genuinely cool, if shallow) shards of space and glass and stuttering loops of physical time, but the collision of the Real and the Virtual feels so much more effective in communicating the idea of time and space shattering and colliding into one another. I just wish it played in this space more, focusing on Ashmore, Reddick, Monaghan, and Hope, rather than the cast of goons and extras who feel wholly separated from the game until the final mission.

I'd like to say that I'd love Remedy to take another crack at this idea, with the lessons they've learned from Control and Alan Wake II, but that already feels like a fool's hope. The ballooning costs of video game development make the idea of filming an entire TV mini-series alongside it feel laughable. Sure, Control's live-action segments were plentiful and superbly produced, but they were also far more restrained than Quantum Break, focusing on short segments with one non-big-name actor each in a couple of highly reusable sets. With both this and its open-world, side-questing structure with plenty of loot and upgrades to collect, Control is something largely in line with the realities and productions of modern game development

Quantum Break isn't rooted in reality for even a second. It's a time-locked instant, the most 2015 game ever made, which makes it all the better that it came out in 2016. There's no future in what Quantum Break envisions. It's a failed experiment, something to shrug at and move on. And yet, it compels me regardless, despite the fact that I don't really like it.

We need games like this, I feel. Historical curios like this show that the shifting landscape of the medium isn't a straight line, it splits off into splintered fraying timelines, some leading to nothing, but others spilling back in unexpected ways. After all, Courtney Hope, who played Beth Wilder here, returned for the starring role in Control, and that game feels so keenly like the product of lessons learned from QB, with everything from the live-action segments, the document-reading, and the combat feeling like a progression from Remedy's previous work. In particular, my complaints about QB's narrative taking place almost entirely off-screen evolves into a hugely compelling aspect of Control, with the genuine highlight of that game being reading the endless documents detailing the horrors and nightmares of America transcribed into corporate mundanity.

And while I've only played a taster of Alan Wake II, there's no doubt in my mind that that game, a bona-fide critical darling the likes of which Remedy hasn't had since Max Payne 2, owes a great debt to QB. Not least because its engine provides the framework for the game, but also because, well, it's been in there, this whole time.

Waiting for The Return.

youtube

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Dahlia (2006)

Though her role is rather brief, appearing in only two scenes, Fiona Shaw absolutely carries The Black Dahlia on her back in terms of making this movie somewhat watchable. By and large this film is a slog, unsure whether it wants to be a noir pastiche, a police procedural, or a torrid romance. Foundering, it manages to find the worst possible confluence between the three options. The end result is an aimless, boring mess that somehow manages to make one of the most sensationalized murders in Los Angeles history a bit of a shrug. But for a few shining moments, we get to bask in the deranged glow of Ramona Linscott. This old money snob is introduced drunkenly dressing down the visiting policeman. It’s an amusing interlude, but little could prepare us for her final appearance. Bedraggled and still with her hair pinned up, Ramona unloads what can only be described as a Joker-tier rant, manipulating her mouth with her fingers like Silly Putty as she screams about the Dahlia murder. More of this please. Shaw knew more than anyone else in the history of cinema EXACTLY what kind of movie she was shooting.

Because oh right, this is a Brian De Palma flick. While he strives for a slick LA Confidential styling to his crime procedural, he achieves something more like the glossy but bizarre cutscene structure of LA Noire. It slips through the tropes, all hard shadows and sultry trumpet riffs. But at intervals, the director seems to slap himself in the face to wake up and remember that he’s Brian De fucking Palma. Sadly, at this juncture in his career, his trademarks veer more in the direction of unintentional hilarity than operatic excess. Sex scenes in the final act are like the cork popping off a champagne bottle, bodies vigorously slamming against one another, paintings dropped off the wall and tablecloths torn away as the camera retreats from the passion. It’s all the better given how muted and chaste the bulk of the movie preceding it proved to be. Bravura camera moves similarly have a contradictory effect. The initial discovery of the body by a woman is just kind of silly, the camera incidentally capturing her panic as it faffs about. It could be some sort of commentary on how a jarring discovery is taking place within a wider, mundane world. But a movie with this many looming face cross-fades, that weird Final Cut Pro dissolve when our hero gets knocked out, and whatever Hilary Swank’s accent is supposed to be doesn’t get to pretend it’s serious and observational.

THE RULES

SIP

Someone says 'fight' or 'alibi'.

Noir jazz trumpet starts to play in the score.

Josh Hartnett looks like he's about to cry.

The movie cuts to a film recording.

Wipe transition between scenes.

BIG DRINK

Someone names a Hollywood figure or film title.

Aaron Eckhart is BIG MAD

Weird cuckolding behavior.

#drinking games#the black dahlia#brian de palma#josh hartnett#scarlett johansson#aaron eckhart#david dastmalchian#fiona shaw#hilary swank#crime

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 1941. Eight decades on, the deification of CITIZEN KANE as "the greatest movie of all time" is doing it no great favors, at least in terms of persuading people to actually watch it. The title suggests a ponderous art film that will feel like homework, which some of its fans try to counter by claiming that its moody deep-focus cinematography and Bernard Hermann score make it some kind of early film noir. Neither of those things is true: CITIZEN KANE is essentially an impish pastiche of the rise-and-fall-of-the-great-man variety of Hollywood biopics, dressed up with (and held together by) a series of shameless narrative contrivances, some memorably witty dialogue, and as many inventive cinematic gimmicks as Welles could squeeze into the two-hour running time. It is, like the radio shows Welles and his Mercury Theatre company had been doing for about two and a half years beforehand, aggressively middlebrow: As Welles himself later admitted, the story really isn't that deep, but it gives the impression of depth, just as some of the clever framing devices create the illusion of a bigger cast and larger budget.

If you take it seriously, KANE, like a lot of later Welles films, is fun for a while and becomes rather dour toward the end, but taking it seriously is a mistake, and the dourness is itself a contrivance. This is a story about an old man's tragic regrets … as imagined by a 25-year-old in a bald cap and padded suit who'd made his name on the legitimate stage, where no death scene is too final to prevent a star from taking his bows after the curtain falls. It's a game, like a cat losing its mind chasing down and vanquishing a new catnip mouse, and the finale, where the plot's central contrivance comes full circle, has that same tail-in-the-air sense of triumph.

#movies#citizen kane#orson welles#herman mankiewicz#bernard hermann#mercury theatre#if you haven't seen it it also helps if you first listen to#some of the surviving mercury theatre radio productions#not even a lot of them!#start with their dracula#or either one-hour production of the count of monte cristo#and of course there's war of the worlds#but if you also listen to a few others you'll get the concept

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

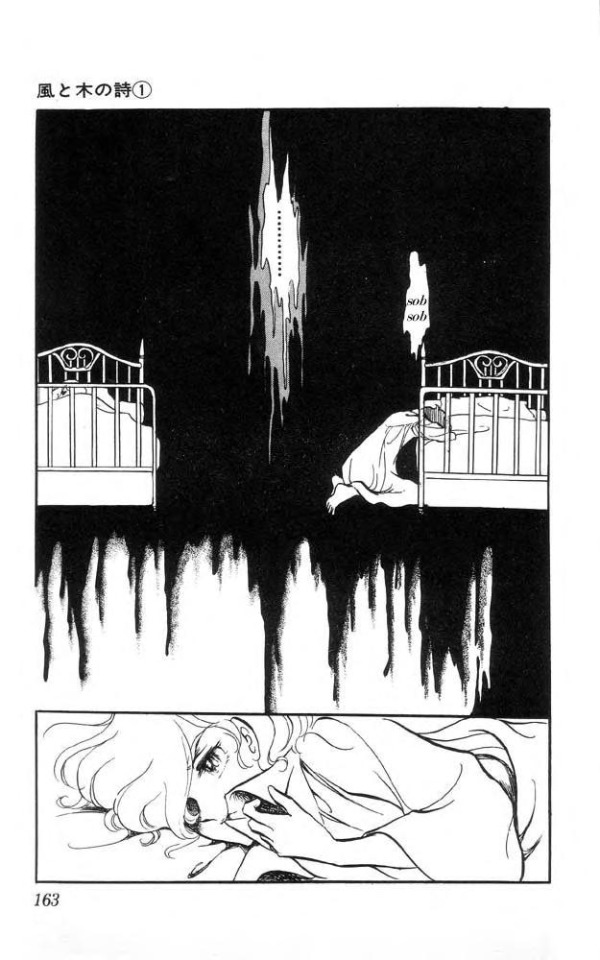

Parallels Between Kaze to Ki no Uta and Blue Velvet

Whenever I read a manga, I take notes and such on the side as I'm reading it.

I went through those notes for Keiko Takemiya's Kaze to Ki no Uta, which was an even more rough read for me than the first time that I read Berserk, and I had a thought; the scene in the first arc which has this page is oddly similar to the scene in David Lynch's Blue Velvet where Frank Booth is introduced.

CWs; discussions of drugging, sexual violence, misogyny/patriarchy; everything that happens in Kazeki and Blue Velvet, pretty much.

What happens in each scene is very similar; a horrified protagonist powerlessly witnessing a rape in the other side of the room which they are in. The impact is very similar, one of terror and confusion with a level of the absurd. The thematics are very similar as well, with Frank Booth's sexual violence throughout Blue Velvet *always* being half an attempt at real sexual pleasure, half an attempt at forcibly asserting a position of patriarchal dominance. The parallels are much more pronounced in the OVA, since that's in a semi-cinematic medium rather than manga, but the feeling was always there.

Much of this came to mind when I thought to myself about how similar Auguste Beau and Frank Booth are conceptually. They both function as living examples of the Lacan quote which goes "masculinity is the pervert's position", they both obsessively control an otherwise picturesque rural environment through intimidation and shadow power, they both use a mix of blackmail, rape, and mercenary violence to torment and suppress those who pose a threat to them, and they both have a high level of familiarity with drugs, though Auguste doesn't have a cpap machine filled with strong drugs. I'm not sure if a parallel could be drawn between Dean Stockwell in the film and Jean-Pierre Bonnard in Kazeki, though both serve as the other half of their respective shadow tyrant's double-bind.

Since Kazeki started a full decade before Blue Velvet, the latter could not have inspired the former and I don't know if manga piracy was advanced enough for it to reach the United States for David Lynch to read after his Dune adaptation crashed and burned. However, if I was to ask this to David Lynch, he'd probably tell me that they were both drawing on the same experiences, emotions, and ultimately societal systems. I remember once joking to my therapist that the plot of Death in Venice happened three separate times in the first Drakengard game and since he's a Jungian, he joked about Yoko Taro having the same "collective unconscious connection" as Thomas Mann.

If a difference were to be drawn between Kazeki and Blue Velvet, it might be that the latter is much more optimistic.

Despite how horrific, lurid, and simply bizarre Blue Velvet is as a genre pastiche of 50's Film Noir films such as Sunset Boulevard or Double Indemnity, Blue Velvet is ostensibly a film about the hero defeating the bad guy and saving the day. It was set at a point which was deep enough into the Aeon of Aquarius that the segmentary systems of heirarchic violence which sustain patriarchy, portrayed in the film as sexual or mercenary violence going downward from a symbolic father to those who are contained within his regime, had imploded so heavily that Patriarchy was rapidly ripping itself apart and self-destroying. The film, furthermore, takes a similar position to patriarchy to what Marx is described by Bataille as having taken about Capital, where once all of its various obstructions toward Human Development are simply removed, Humanity will flourish once more.

With Kazeki, however? It's set during a time when there are some old people who were alive when Mary Wollstonecraft was still alive, when universal suffrage is many decades into the future, when the authoritarian rule of the church and the nobility is *only beginning* to be contested, when colonialism is at its highest levels of brutality (which the manga makes very clear, connecting Auguste's brother's incest and generalized sadism to his position as a colonial official in French Indochina), and in which the development of all of the forces of oppression and unfreedom present will not begin to be possible to assail until the First World War destroys their productive capabilities at least. Auguste Beau isn't as much of a cartoon villain as Frank Booth, furthermore, and has an ability to check his boundless hatred for all which is young and beautiful for the sake of self-preservation, rather than simply erupting into ultimately self-destructive violence at the slightest notice.

#kaze to ki no uta#blue velvet#surrealism#babst blue ribbon#Tumblr kept breaking when I tried to post this.#They must hate Decadent Art.#Sometimes I wish that Kazeki was as surrealistic as a David Lynch film.#Then that would just be Berserk of Evangelion though.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who Theme: Round 1

The Maltese Penguin

"The 2002 story The Maltese Penguin, a pastiche of 1940s noir detective films, featured an appropriate slow-jazz score which, at the end, transitioned into a rendering of the closing theme."

youtube

The Rapture

"2002's The Rapture, which was set at a 1990s Electronic Dance Music rave, featured an EDM version of the theme."

youtube

Doctor Who and The Pirates

"For the 2003 audio Doctor Who and the Pirates, a musical story in the vein of Gilbert and Sullivan productions, the closing credits used a new sea-shanty rearrangement of the theme in line with the story's score."

youtube

Horror of Glam Rock

"The 2006 story Horror of Glam Rock featured an appropriate glam rock version of the theme."

youtube

#doctor who#classic who#doctor who theme#big finish#sixth doctor#seventh doctor#eighth doctor#dw soundtrack poll#round 1#Youtube

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from "Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy" (1990), Arjun Appadurai

Iyer's own account of the uncanny Philippine affinity for American popular music is rich testimony to the global culture of the hyperreal, for somehow Philippine renditions of American popular songs are both more widespread in the Philippines, and more disturbingly faithful to their originals, then they are in the United States today. An entire nation seems to have learned to mimic Kenny Rogers and the Lennon sisters, like a vast Asian Motown chorus. But Americanization is certainly a pallid term to apply to such a situation, for not only are there more Filipinos singing perfect renditions of some American songs (often from the American past) than there are Americans doing so, there is also, of course, the fact that the rest of their lives is not in complete synchrony with the referential world that first gave birth to these songs.

In a further globalizing twist on what Frederic Jameson has recently called "nostalgia for the present" (1989), these Filipinos look back to a world they have never lost. This is one of the central ironies of the politics of global cultural flows, especially in the arena of entertainment and leisure. It plays havoc with the hegemony of Eurochronology. American nostalgia feeds on Filipino desire represented as a hypercompetent reproduction. Here, we have nostalgia without memory. The paradox, of course, has its explanations, and they are historical; unpacked, they lay bare the story of the American missionization and political rape of the Philippines, one result of which has been the creation of a nation of make-believe Americans, who tolerated for so long a leading lady who played the piano while the slums of Manila expanded and decayed. Perhaps the most radical postmodernists would argue that this is hardly surprising because in the peculiar chronicities of late capitalism, pastiche and nostalgia are central modes of image production and reception. Americans themselves are hardly in the present anymore as they stumble into the mega-technologies of the twenty-first century garbed in the film-noir scenarios of sixties' chills, fifties' diners, forties' clothing, thirties' houses, twenties' dances, and so on ad infinitum.

As far as the United States is concerned, one might suggest that the issue is no longer one of nostalgia but of a social imaginaire built largely around reruns. Jameson was bold to link the politics of nostalgia to the postmodern commodity sensibility, and surely he was right (1983). The drug wars in Colombia recapitulate the tropical sweat of Vietnam, with Ollie North and his succession of masks - Jimmy Stewart concealing John Wayne concealing Spiro Agnew and all of them transmogrifying into Sylvester Stallone, who wins in Afghanistan - thus simultaneously fulfilling the secret American envy of Soviet imperialism and the rerun (this time with a happy ending) of the Vietnam War. The Rolling Stones, approaching their fifties, gyrate before eighteen-year-olds who do not appear to need the machinery of nostalgia to be sold on their parents' heroes. Paul McCartney is selling the Beatles to a new audience by hitching his oblique nostalgia to their desire for the new that smacks of the old. Dragnet is back in nineties' drag, and so is Adam-12, not to speak of Batman and Mission Impossible, all dressed up technologically but remarkably faithful to the atmospherics of their originals.

The past is now not a land to return to in simple politics of memory. It has become a synchronic warehouse of cultural scenarios, a kind of temporal central casting, to which recourse can be taken as appropriate, depending on the movie to be made, the scene to be enacted, the hostages to be rescued. All this is par for the course, if you follow Jean Baudrillard or Jean-François Lyotard in a world of signs wholly unmoored from their social signifiers (all the world's a Disneyland). But I would like to suggest that the apparent increasing substitutability of whole periods and postures for one another, in the cultural styles of advanced capitalism, is tied to larger global forces, which have done much to show Americans that the past is usually another country. If your present is their future (as in much modernization theory and in many self-satisfied tourist fantasies), and their future is your past (as in the case of Filipino virtuosos of American popular music), then your own past can be made to appear as simply a normalized modality of your present.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

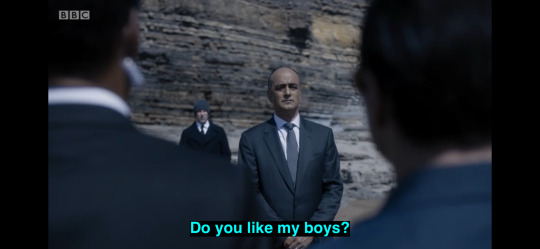

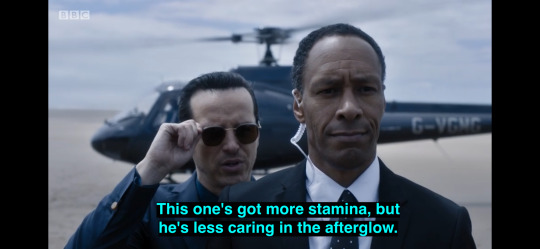

Mycroft’s romance film in TFP.

I don’t usually rewatch BBC Sherlocks’ The Final Problem… nor season 4 for that matter, but recently I revisited the awkward season and when it came to the early scenes in the finale episode, I couldn’t help but laugh over the fact that Mycroft’s romantic film he watches ends up being corrupted… which is already pretty telling on a ground level analysis, especially considering Mycroft is played by Mark Gatiss, the literal writer.

Naturally, I investigated further into the film that is used in an attempt to see if the plot line possibly matches/ mirrors that of Sherlock and John. However I found out that the film was in fact made by Mark and Steven. In response to the question, Ian Hallard (Marks husband) responded:

I'm not sure they gave it a name! It's a film noir

pastiche they wrote and shot themselves

though - not an existing film.

So… in some way this makes things more interesting. I find it very unlikely that they didn’t leave us little clues and subplots intermingled within the romance. With that being said, I decided to analyse the scene, and this is my findings…

The plot of the romance.

From the short clip we get, we can gather that a woman is heavily flirting with a police officer in his office whom he returns the flirting.

The woman insists she will be arrested by the man (in a seductive tone of manner) and he replies that he will not arrest her, only keep a very… very… close eye on her… (if you get my drift.)

Props and design.

The first thing I noticed in the backdrop led me to immediately link the man with another character. It was a globe in the background which reminded me of Mycroft’s in his office.

And then in Mycroft’s office (TEH)

Furthermore, the lamp closely resembles Mycroft’s which we see in The Six Thatchers. The fact that both of them have an office and hold authority in some kind of civil occupation makes it quite an obvious mirroring.

Who’s the woman then?

I think that the woman represents Moriarty. Her characteristics and flirty manner to higher ranks perfectly matches Moriarty, who we see uses seduction and ‘love’ to gain closure on Sherlock. This is evidenced with himself posing as Molly’s boyfriend to meet Sherlock and Kitty’s boyfriend to expose Sherlocks public image through the media. Moriarty flirts a hell of a lot with Sherlock in the pool scene (TGG) and also makes sex references with the governor in the flashback scene in The Final Problem.

Keeping the M theory in mind that Moriarty manipulates and threatens Mycroft into giving information about Sherlock, it’s not impossible that Jim keeps up with his flirty attitude with Mycroft … in fact it’s made explicit that he does and we are shown this in the flashback too.

But the man quite clearly flirts back in the film? This is a tricky one but it’s pretty clear that Mycroft underestimates Moriarty’s power in the beginning of the series. Perhaps he plays along to (in his mind) humour the idea that Jim has already won to give the perception he is less smarter than he gives on. This is until he got too deep in the threats and manipulation and finds himself messed up in the web. The man also finds himself having to hold back in the film as well when things get a little too risky.

So we have established that The man is a Mycroft mirror and the woman is a Moriarty mirror. But what can we take away from it? I’ll start at the beginning and make my way through :)

A CHRONOLOGICAL ANALYSIS.

The scene begins with the following:

Man- You know I could arrest you.

woman- What for?

man- Wearing a dress like that.

woman- Would you like me to take it off?

man- Then i’d really have to press charges.

Woman- Press away.

Prior to The Reichenbach Fall in season 2, we are aware that Mycroft has been trying to keep Sherlock safe from Moriarty. In fact, in the end of The Hound Of The Baskervilles, Moriarty has been in a cell before Mycroft says “Let him go.”

We can assume they wanted the none existent “key code” which in unlikely because I don’t think Mycroft would be so naïve. So I think what the scene tells us is that Mycroft had no hard evidence to put Moriarty behind bars. No matter what he accuses him of, Moriarty is already ahead of him, and he almost mocks Mycroft. “Would you like me to take it off?” because he knows he can play the Government and the Secret service, they have nothing on him.

In The Final Problem flashback, Mycroft tells Moriarty: “Until you commit a verifiable crime, you are, I regret, at liberty.”

Then the camera angle changes so that we see the projector light blinding us so that Mycroft is barely visible.

The two dim lights appear to look like dying flowers, representative of Mycroft’s dying power and authority. The blinding light corresponds to the blind ignorance and stupidity that Mycroft held for not realising he was being played.

woman- Isn’t that how they got started?

man- Who? (The camera cutes to Mycroft)

woman- Adam and Eve.

man- Oh them.

woman- And that turned out ok.

man- You think so? I thought it was supposed to be the beginning of all human misery.

The use of “they” makes me wonder who they are referring to… if not Adam and Eve. I’m not too sure on this one to be honest with you. Could Adam and Eve represent Sherlock and John? Of the top of my head, Mark Gatiss could be referring to the ACD Sherlock Holmes because its the first fabrication of these characters. I can’t seem to link them to the previous lines though, however the next line “Oh, them.” is a line that Mycroft (Mark) lip-sinks.

That’s why I assume we are talking about Sherlock and John because of the ironic smile and knowing shake of the head. He also happens to lip-sinks “You think so? I thought it was supposed to the beginning of all human misery.” With the continuation of Adam and Eve as the first Sherlock and John, this implies that, as a result of Moriarty, Mycroft questions the sanity of of his brother and John.

Mycroft then takes a sip of alcohol, whether it be whisky or brandy...

Despite his cool façade, The Drink Code suggests that taking hard alcohol means fear. Mycroft fears for Sherlock and feels as if he has been caught in Moriarty’s web, leaving his younger brother suggestable and in danger. Human misery.

The camera then turns back to the film.

woman- Now what was all that about arresting me?

This line from the woman closely resembles that of Moriarty in The Final Problem when he is at Sherrinford with Mycroft.

“So am I under arrest again?” To which Mycroft says: “You remain a person of interest.”

The camera closes in on Mycroft once again, articulating the idea that Mycroft wanted to arrest Moriarty. He even smiles at the idea.

man- well maybe not arresting you.

woman- no?

man- I could just keep you under close watch.

The camera returns to Mycroft once more. This was maybe his error. Letting Moriarty go free and underestimating his danger. He thought if he just kept an eye on what he thought (which was indefinitely a mis-calculation) Moriarty was up to, he would keep himself and Sherlock safe...

Following this line, Mycroft and us witness the first corrupted glitch which we know after to be Sherlock and John. However, it’s quite ironic that it occurs at the same point at which Mycroft makes his error in letting Moriarty be liberated.

After a few corrupted scenes, Mycroft frowns and looks behind at the projector. He turns to the blinding light of ignorance and sees what has happened to him.

Meanwhile:

woman- shame I was looking forward to putting myself into the hands of the authorities.

If that doesn’t sound like Moriarty then I don’t know what does! It makes if even better that at this exact point, the camera shows a close up of a rather worried Mycroft.

man- you were?

woman- finger-printing, being searched... thoroughly.

Again, it’s the spitting image of Moriarty!

The film glitches between a young Mycroft and the woman, furthermore proving some kind of link between these two.

Then Mycroft appears to lose his disturbance when an extended clip of the Holmes family plays before his whole nostalgia is corrupted..

“I’m back.”

#sherlock#sherlock holmes#acd canon#bbc sherlock#sherlock icons#mark gatiss#mofftiss#theory#benedict cumberbatch#martin freeman#season 4#the final problem

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, Sus: excuse me, but how come I've NEVER HEARD OF ROUGH MAGIC BEFORE???? Like, WHAAT??? your description on that gifset has got my jaw on the floor, OBVIOUSLY i must find this film immediately!!!

Angie, my lamb, my heart, my little pastry, I am DELIGHTED to throw Rough Magic, (1995, dir. Clare Peploe) at you.

What is this 'noir pastiche road-movie with magical realism and magical magic', you ask? Besides GENIUS?? Well, firstly, it is not a Good Movie. I mean that's a given. Sitting on 25% review score on Rottem Tomatoes so like let's be reasonable about this. But also I am frequently obsessed with movies that can't climb over that quarter line, so this is not new territory for me, lol.

OK, so: it's a mid-90's little caper film based on a James Hadley Chase pulp novel from 1944. This guy is sort of the British Louis L'amour but he wrote about American gangsters. Shrug emoji I guess. After WW2, settled down in France, and using a slang phrasebook and a map, churned out over 90 smash hit, all plot, no lore, american gangster pulp pagerturner novels. One of which was 'Ms Shumway Waves a Wand', which I have not read. But someone did, and this movie happened. It's an incredibly odd mix of genres, some of which just don't gel and it's awkward, and some of which are so great they rewire my brain.

The late great Roger Ebert said Clare Peploe "deserves credit for the uncompromising way in which she stage manages a head-on collision between [the 2 genres] in Rough Magic, an oddly enchanting fantasy that almost works" - that sort of sums it up, a head-on collision but it ALMOST works. But also it has so much bizarre, fun, aimed-directly-at-me stuff.

Everyone in this movie is basically some kind of con artist. No one is playing straight with anyone, ever. Always a treat. The protagonist witnesses a crime in Act 1, goes on the run by heading for the Mexico/Guatemalan border to a) skip town, and b) keep a promise about finding a holy woman there who can help her with her own magic. Everyone else follows. Hijinks ensue.

Bridget Fonda: Myra, a cynical magician's assistant in LA, big Lauren Bacall vibes. Fast-talking. Excellently dressed. Unruffled. On the run. Cranky. Probably/definitely an actual witch. Big heart but she'd never admit it, and removes it (literally) to prove the fact. Lays a giant robin's egg at one point.

Russel Crowe: a down-on his-luck PI. If you saw La Confidential and though 'hmm Russel Crowe looks nice in 40's gear, he should always wear that', then congratulations, he's wearing that, but he's a PRE-FAME BABY. Has PTSD but would never admit it. Dies and is resurrected at one point.

Jim Broadbent: possibly an anthropologist, possibly a snake-oil salesman, mostly he's just drunk. Believes in magic, wants to prove it. Idealist but would never admit it.

Also featuring: Myra's nuclear-obsessed fiance, his secretary Toby Ziegler, unsubtitled spanish dialogue, a man turned into a sausage, everyone refusing to admit Feelings, hallucinogenic drugs in gourds, floating make-outs, top hats. 'Comedy, love, and a bit with a dog'.

The dialogue is EXTREMELY mannered, in that 'everyone talks like roger rabbit pretending to be a gangster' sort of way, which Bridget Fonda admits she struggled with making it sound natural, but I think it works. That Big Sleep kind of quick back-and-forth can seem a bit off when the picture is in colour and you're otherwise aware it's 1995, but honestly it's no LESS mannered than the Whedon-speak that's overtaken contemporary american films, which is an equally specific/mannered dialogue form tbh. The costumes are beautiful. The cars are beautiful. The photography is beautiful. There's a double in the casting re: the holy woman and a cantina owner they meet along the way that is never explained. It's just that kind of party.

If you have not been able to obtain it: it used to float around in t*rrenting, but those golden days are probably over. I recently got a hard copy DVD from an online retailer. I think Amzn will sell you a digital one.

Or I have an .avi file if you ask nice :-P

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

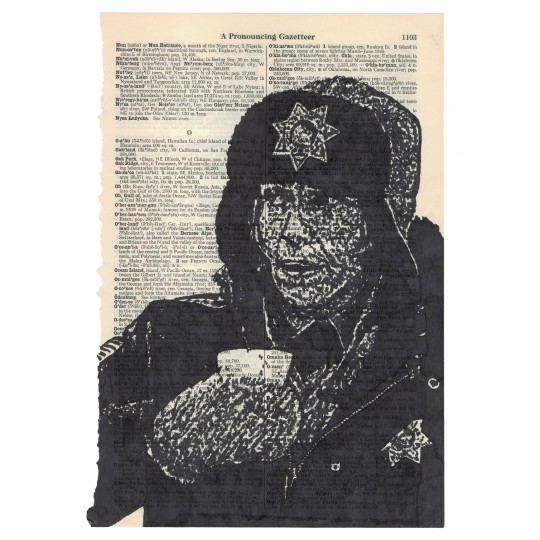

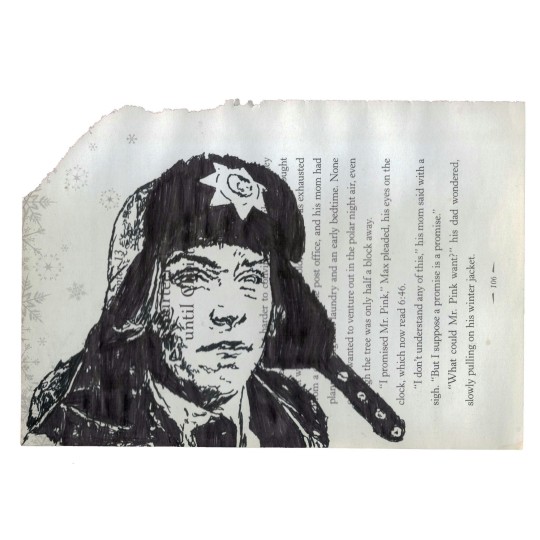

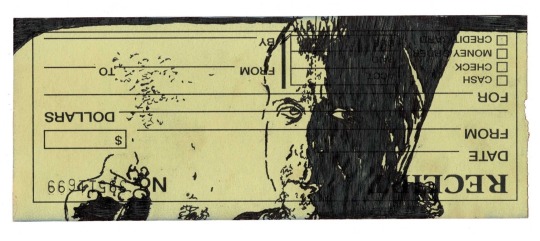

On February 3, 2012 Brick debuted on Swedish television.

#brick#brick 2005#joseph gordon levitt#film noir pastiche#noir pastiche#neonoir movies#crime film#crime thriller#drug movies#drug film#neonoir#neonoir thriller#neonoir film#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#pop art#modern art#pop surrealism#cult movies#portrait#cult film

1 note

·

View note

Text

Goncharov: The Red Edit predates Schindler's List by 5 years and I'm tired of the claims that it's a derivative piece of stunt editing. The exclusive use of red explores Color Theory, and, if I may be so bold, Color Perception. By which I mean not only the emotions and esoteric concepts ascribed to colors, but also the myths,l egends, stories, and sayings that inform those emotions and concepts.

The Red Edit renders the world of Goncharov in black and white, linking it even closer to noir films of the early 20th century, with red being recolored where it was present before, with two notable exceptions.

This, to me, highlights the commonalities between the two sides, as the Italian and Russian flags both feature prominently. The viciously brutal and cathartically gory action scenes, (Often mistaken for a Hammer Horror pastiche, but is more likely a response to and exaggeration of the gore present in Twitch of the Death Nerve (1971)) take on a different, more melancholy tone, specifically when compared and contrasted to Katya's pining and romantic scenes.

So before we can discuss the ways in which the actions scenes are reframed, we must discuss the first notable exception to the use of red in the film. Katya's pining and romantic scenes are tinted rose-pink, a clear play on the phrase rose-colored glasses. They are not uniformly pink, merely the red that Gancharov or Andrey are wearing is instead pink, including the blood on their clothes when they first fight over her and Goncharov leaves Andrey for dead with a bullet in his chest.

(Sidebar, totally lost it the first time I saw this and Andrey came back, the explanation of his heart being on the right side of his chest, and the confessional scene with the priest where he admits Goncharov stole his heart anyways, *chef's kiss*)

Goncharov actually introduces pink to the film first, the blood of his enemies as he storms through the Russian safehouse for Katya is initially confusing, as we've seen blood as red previously in the film, but is contextualized by Katya's use of pink to mean that Goncharov loves something about this violence.

Through out both Goncharov and Katya's development, the pink darkens to red as they grow and shed their naivete and selfishness, coming to empathize with their enemies.

Lastly, the use of the color red is altered in one other specific context, and is often mistaken as homophobic. When Andrey and Goncharov finally kiss, the strand of saliva that lingers between their lips on the close up is red. While the creator (a gay Korean-Italian man whose gows by the name Amedeo Amadeus) has stated in interviews that it was meant to symbolize the Red String of Fate and the concept of Jung, not blood.

Given that the scene is, in it's original context, explicitly homosexual; deliberately shown and framed to not be an attempt a CPR, it is unrealistically tender, and passionate but not fetishistic, it's somewhat suprising that anyone would mistake this as a censorship edit.

However, the creator stated that this was actually meant to symbolize the acceptance of a marriage proposal, which was his interpretation of Goncharov's last line, spoken to Andrey but unheard by the audience.

Before I can recommend the Red Edit, however, I must recommend those at risk for seizures instead watch the Re:Red Edit, as the original Red Edit my cause episodes bc of the way it was made.

When Goncharov released in 1973, it was in color, and the Red Edit achieved its black and white capture by handcranking a film camera aimed at a theater screen displaying the color movie. despite the creator's best efforts, there is an unavoidable flickering at times, as the hand crank desyncs from the projection.

In conclusion, no matter how you watch it, the Red Edit is astonishing peice of critique, a display of technical skill, and an artwork in it's own right that deserves better than to be derided as a derivative of 'that one Schindler's List scene'.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blood and Blue Diamonds: Chapter 5 Notes

Every Sane Writer: 1920s noir AUs are the best, just glitzy parties and speakeasies everywhere, or maybe the 1940s, after everybody got back from a war…

Me: Might I interest you in... the Great Depression

So obviously I’m writing a pretty stock detective pastiche, but a huge amount of Blood and Blue Diamonds was inspired by something I’m not sure counts as noir or hardboiled: The Day of the Locust, a 1930s novel about a failed artist in Hollywood during the Depression. It’s an amazing book — acerbic and witty and quietly sad — and I highly recommend it, although if you read it you will recognize just how much of its style I’ve badly ripped off.

Jayce’s building was based on the Villa Primavera, an apartment complex built by a husband-and-wife architecture team that worked in LA during the 1920s. The villa was probably the inspiration for the setting of In A Lonely Place, a (likewise absolutely fantastic) classic Humphrey Bogart noir. Let’s just… not think about how my fic’s whole plot is basically “Humphrey Bogart is blorbo now.” The Villa Primavera never ended up a weird decrepit ghost building, but in my defense the LA housing market did flat-out crater during the Depression and sometimes resulted in places being all but abandoned by their owners.

Viktor’s camera is (well, was) a Leica I, a high-end compact design that set the 35mm film standard in the mid-1920s and completely revolutionized photography in the process. The market would get flooded by far cheaper imitations (roughly starting with the Argus), but mainly in the later '30s and '40s, a little after where I’m staking my claim.

Incidentally at one point I had Viktor as a newspaper photographer, but it gave him too much steady work to let him go running around with Jayce, and I liked the dynamic of him being the demimonde foil to Jayce’s relatively upstanding citizen. But it means we don’t get to imagine his gorgeous hands on one of those giant Speed Graphic press cameras.

Jinx’s (spoilers for the unnamed girl who looks exactly like Jinx, I guess) outfit is premised on the popularity of flowing women’s slacks and beach pajamas in ‘30s fashion. As seen on this McCall's cover, beach pajamas could be extremely extra, but think something more along the lines of flared capris.

And finally, before researching this fic I was vaguely familiar with Four Roses as the thing Philip Marlowe drinks in Raymond Chandler novels, but it was also just the most popular whiskey of the period, having survived Prohibition by rebranding as an obviously totally non-recreational, health-promoting medical whiskey company.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week I released a new book; The Man We Knew, a third party adventure for Orbital Blues. I've described it as a noirish thriller for sad space cowboys.

It's a pastiche if the film The Third Man (directed by Carol Reed and starring Orson Welles) and begins much the same way, but In Space.

The Crew of Interstellar Outlaws arrive on Catapult Station Odessa because a friend of theirs, Cash Chi, has a job offer. Questions are provided to establish how the crew all knew Chi but upon their arrival the Crew finds Chi deceased, after an alleged accident.

From there the book introduces a range of characters who populate the station, possible leads into both the death and the racket Chi was involved in and various directions for the story to go in.

It all takes places on Catapult Station Odessa; an entryway to the system divided between three squabbling conglomerates. Life is hard and the black market thrives there.

The adventure is 26 pages in a black and white layout with high contrast photography, mimicking the style of the film noir that inspired it.

This is the first adventure I've written, rather than a self contained game and it was a lot of fun to do. I think that's something I'll try and do more of this year.

You can get it over on Itch for $10; https://ratwavegamehouse.itch.io/the-man-we-knew

2 notes

·

View notes