#for illustrative purposes it is irrelevant

Text

How my identity be feeling rn

#asexual biromantic#asexual lesbian#asexual#ace#add some demi to that romance and it's more accurate#but like#for illustrative purposes it is irrelevant

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before you kill a character...

Consider the following.

Does it advance the plot?

Killing off a character should serve a purpose in propelling the story forward. It could introduce a new conflict, escalate existing tensions, or trigger a series of events that drive the plot in a new direction. If the character's death doesn't contribute to the overall narrative arc, it might feel gratuitous or unnecessary.

Does it fulfil their personal goal?

Each character has their own arcs and objectives within the story. If the character's death aligns with or resolves their personal journey or goal, it can add depth and closure to their character arc. Conversely, if their death feels disconnected from their goals or character development, it may come across as arbitrary or unsatisfying.

Does it emphasise the theme?

The death of a character can highlight or support key themes by demonstrating their consequences or illustrating the moral dilemmas faced by the remaining characters. A well-executed death can deepen the audience's understanding of the story's themes and add layers of complexity to the narrative.

Does it motivate other characters?

Character deaths can serve as catalysts for growth or change in other characters. The loss of a loved one or ally can drive characters to reevaluate their beliefs, make difficult decisions, or embark on new paths. The impact of the death on other characters can reveal their strengths, weaknesses, and relationships, adding depth to the story's interpersonal dynamics.

Does it create realism?

The inclusion of death can lend authenticity to the story world. If the character's death feels earned and plausible within the context of the narrative, it can enhance the story's credibility and emotional resonance. However, if the death feels contrived or forced, it may strain the reader's suspension of disbelief.

Is it a fitting recompense?

In some cases, characters may meet their demise as a consequence of their actions or decisions. If the character's death serves as a form of justice or retribution for their deeds, it can feel narratively satisfying and thematically resonant. However, if the death feels arbitrary or disconnected from the character's arc or the story's events, it may feel unsatisfying or even unjustified.

Don't kill off a character for the sake of shocking the reader or invoking sadness; when considering whether to kill off a character in your story, it's crucial to ensure their demise serves a purpose beyond mere shock value or convenience. Ensure each character serves a purpose that enriches and enhances the story to avoid having to eliminate them solely for convenience. Don't use death as a means to remove an extra or irrelevant character—you shouldn't have them in the first place, if they're disposable. Doing so will undermine the depth and integrity of the narrative.

Hope this was helpful! Happy writing ❤

#writeblr#writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#writing resources#creative writing#character writing#plot development#deception-united

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the most common criticisms of "housing first" initiatives (programs to provide housing for unhoused people unconditionally without gatekeeping) is that housing first "does not improve mental health."

Now, let's set aside for the moment that this criticism is irrelevant -- the purpose of housing is to provide shelter, not to "improve mental health" -- what definition of "mental health" could possibly make this true? As much as I try to critique and deconstruct the social construction of "mental health," how could it possibly be true that having a safe, assured place to live would not result in greater happiness, greater inner peace, less depression, less anxiety, less negative emotions, than living on the street?

What possible definition of "mental health" would not be improved by being housed rather than unhoused?

Answering this requires unpacking the wildly different, almost completely unrelated, definitions of "mental health," one applied to relatively privileged people, and one applied to oppressed people.

For relatively privileged people, the concept of "mental health" is centered on emotional well-being, introspection and self-awareness, and the mitigation or management of negative emotions like pain, depression, anxiety, and anger.

For oppressed people, the concept of "mental health" is centered on compliance, obedience, and productivity.

Like most privilege disparities, this isn't binary. For most people who are privileged in some ways and marginalized in other ways, "mental health support" will include some degree of the emotional support given to privileged people, and some degree of the compliance and productivity training given to oppressed people, with the proportions varying on where exactly each person falls on various privilege axes. All children are oppressed by ageism, so all children's "mental health" has some elements promoting compliance, obedience, and productivity. But relatively privileged children may also receive some emotional support mixed in, while children of color, children in poverty, and children with existing neurodivergence labels will receive a much higher ratio of compliance training to emotional support.

One of the clearest illustrations of this disparity is the contrast between the "self-care" recommended to privileged people, and the "meaningful days" imposed on oppressed people.

Relatively privileged people are often told, by therapists, doctors, mental health culture, and self-help books, that they are working too hard and need to rest more. They're told that for the sake of their mental health, they need work-life balance, self-care, walks in the woods, baths with scented candles. Implicit in these recommendations is that the reason these people are working too hard is because of internal factors, like guilt or emotional drive, rather than external factors, like needing to pay the bills and not being able to afford a day off.

By contrast, unhoused people, institutionalized people, people labeled with "severe" or "serious" or "low-functioning" mental disabilities, are literally prescribed labor. Publicly funded "mental health initiatives" require the most marginalized members of society to work tedious jobs for little or no pay, under the premise that loading boxes at a warehouse will make their days "meaningful" and thus improve their "mental health." And unlike the self-care advice given to relatively privileged people, the forced-labor-for-your-own-good approach is not optional. People are either forced into it directly by guardians or institutions, or coerced into it as a precondition to access material needs like housing and food.

The form of "mental health" applied to relatively privileged people has some genuinely useful and beneficial elements. We could all stand to introspect and examine our own feelings more, manage our negative emotions without being overwhelmed by them, have self-confidence. We all need rest and self-care.

Still, privileged mental health culture, even at its best, is deeply flawed. At best, it tends to encourage a degree of self-centeredness and condescension. It's obsessed with classifying experiences as "trauma" or "toxic." It's one of the worst culprits in feeding the "long adolescence" phenomenon and generally perpetuating the idea that treating people as incompetent is doing them a kindness. Even the best therapists serving the most privileged clients have a strong tendency towards gaslighting and "correcting" people about their own feelings and desires.

But perhaps the worst consequence of privileged mental health culture is that it gives cover to the dehumanizing, abusive, compliance-oriented "mental health care" forced upon the most marginalized people. Privileged people are encouraged to universalize their experiences with sentiments like "We all deal with mental health" or assume that the mild, relatively benign "mental health care" they experienced are the norm, so what are those silly mad liberation people complaining about?

Tonight, I listened to a leader from an agency serving unhoused people talk about how "Everyone struggled with mental health during the pandemic"... and then later mention that their shelter categorically excludes people with paranoid schizophrenia diagnoses.

So perhaps "everyone struggles with mental health," but only certain people are categorically excluded from services, from shelter, from autonomy, from basic human rights, because of how their brains happen to work.

As always, it seems like so much effort in the mad liberation/ neurodiversity/ antipsychiatry movement is spent holding the hands of relatively privileged people receiving relatively privileged "mental health care" and reassuring them that we're not trying to take it away from them. Fine, it's great that you like your antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication and your nice therapist who listens to you and your support group. Great. Go live your best life. But that has nothing to do with our fight against forced drugging, forced labor, forced institutionalization, forced poverty. It's not even close to the same "mental health."

#mad pride#universal housing#neurodiversity#anti psych#ableism#social services#mental health#poverty#housing#housing crisis#capitalism#late capitalism

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

[Information regarding the visual stylization and anthropomorphization in my OC world/story in development 'circusworld']

The "animals" in circusworld are all people. They are drawn as anthropomorphic animals for stylistic and symbolic purposes. Any species may exist, but I tend to prefer to draw my favorite animals or the animals which are most symbolically important to me. So while birds, reptiles, fish, and insects exist in their world, you are more likely to see lions and zebras as the main characters. They should all be drawn with human bodies and limbs, including plantigrade legs/feet, with the exception of ungulates which may be given ungulate feet. Insect species may have wings on their backs. Bird and bat species may have wings either on their backs or as extensions of their fingers. Their hands are humanlike with the exception of paw pads and claws for mammals, and the aforementioned avian species. Their heads should have humanlike foreheads, brow ridges/eyebrows, and eyes, but they may have animalistic noses and mouths. They have hair on their heads. They have animal ears and tails. For all intents and purposes, they are "humans," but artistically, they are "animals" who are undoubtedly people.

They may have flat chests or defined chests, including through transitional surgery. Nipples are not drawn. Lower genitalia is not drawn. Both of these features technically do exist in their world for reproductive/child raising purposes, but it is not the focus of the story and is not necessary to illustrate them. They may have body hair in addition to the fur/feathers/skin/scales on their bodies. They do not necessarily feel the need to wear clothes. Many of them do, for various reasons. Clothes may be physically necessary for warmth, protection, or as a uniform. Some clothes are worn simply for fun or fashion. Many circus characters enjoy clothing as costume.

Feral animals exist in their universe and appear and behave exactly as they do in our universe. They cannot talk, and they are kept as pets and used as livestock. It is not seen as weird for an animal person to own a feral animal pet, because animal people are entirely separate beings from feral animals.

Essentially, animal people are just people. Thus, their species is not often commented on by other animal people, and is often entirely irrelevant to their lives. There is no species discrimination or predation amongst animal people, although certain animal people species may have more of a taste for feral animal meat than others. In addition, some species behaviors may be adapted into personality or lifestyle traits, such as a sea lion enjoying swimming. However, a cat could enjoy swimming just as much. Animals of all different lifestyles and personalities exist.

Animal species are often used to symbolize different traits that we humans attribute to animals. For example, a lion symbolizes bravery/courage, devotion to a group/family, and physical strength. As such, a lion character may embody these themes more heavily. In the case of zebras, they are used specifically because of their symbolic meaning as a representation for under-diagnosed/rare medical conditions, and zebra characters are likely to be used to explore concepts related to illness and disability.

In conclusion: I am a furry artist above all else. I thrive when I am making furry art. I love the creative freedom and opportunity to explore symbolism that is inherent to furry art. I do not think I could tell a story or create a world that I was satisfied with if all of the characters were humans, because of the way my brain thinks in colors and symbols like this. But with this project specifically, the characters are just people who happen to be animals.

#art#circusworld#IM SICK OF FURRY MEDIA BEING WEIRD ABOUT THIS STUFF#no more furry racism and antisemitism metaphors that are always poorly handled

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about John Silver being the one main character who has no backstory, on a show where all the main characters are so driven and so created and driven by their backstories (Flint most of all but not just Flint). While Silver is left a mystery, on purpose by the writers, and stated outright by the character, that he’s not going to tell and the reasons. That he couldn't find meaning in it and that all it would do is become yet another illustration of how the world is full of horrors. He calls it “irrelevant.”

I’m torn between believing Silver's backstory was prosaic, that he had a decent childhood, with kind parents of modest means, and ran away to become a ship’s cook because he got bored and wanted to see the world vs believing he survived many abuses and tragedies and not telling his tale is his way of shrinking it. It gives him power over what will define him. He starts writing his own story fresh from the first episode of Black Sails. Flint gets almost lost in his own narrative. Max and Eleanor and Anne's back story fuels their anger and keeps them going and gives them determination as they try to become beyond it, not get lost in it. Whereas Silver refuses to let his backstory narrative write him--what happens is that Silver starts letting the freshly created legend of Long John Silver take hold, starts becoming the legend. So he finally gives in to letting a story define him to some extent but he keeps the divide between himself and the persona far more than Flint does

On a show about the power of stories and narratives, Silver, who is a skilled storyteller, and himself becomes a legendary story, the one story he can’t tell and won't use, is his own before Nassau, before he meets Captain Flint.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

//Spoilers for Everything in AC6: Fires of Rubicon//

The Meaning of the Motif of "Borrowed Wings" and how G5 Iguazu Exists to Reinforce It

What seems to fly over everyone's heads about G5 Iguazu is that the point of his character is how 'deciding upon a goal and having the willpower to strive for it, no matter what' is literally as important as the line between life and death.

You need to find a purpose for yourself that you personally believe in. Cause no matter how grand or how petty that purpose is, if you don't have one... you die!

With whether or not you actually succeed at that goal being completely irrelevant... to your conviction for it.

(Something, something, it's the ambition that you're living for, not whether or not you get the accolades at the end.)

A moral proclaiming the importance of "deciding upon a purpose of your own free will, and then pursuing that goal no matter what setbacks you encounter" is all nice and easy when you're main character e621, who experiences no setbacks because, as the player, you're necessarily going to be strongest fighter in the galaxy.

But it's pretty obvious how trite that is on its own, where your only canonical character trait is that you always win no matter what.

And so, Iguazu's purpose narratively is to show how, beyond any ounce of doubt whatsoever, that 'winning' is not a relevant part in what makes "having a purpose" so important, or so necessary.

In essence: It's what makes Iguazu live.

Start of the Game: Volta and Iguazu both want to beat up Michigan.

- Volta gives up, and then he gets sent by Michigan to die at the Wall.

- Iguazu deserts. And he does not die at the Wall.

After Gallia Dam he send you hatemail to say that the Redguns will scale the wall, but Iguazu himself doesn't even approach the Wall after this. As G4 Volta's last words reveal, he deserts before the operation is attempted.

Iguazu *himself* watches from the sidelines, costing him no less than an almost certain death like Volta's.

And the reason Iguazu changes his mind about scaling the wall with the Redguns is because, after Gallia Dam, Iguazu decides upon his purpose. His personal conviction.

Iguazu personal goal becomes -> He wants to kill you.

We love pathetic boys.

But the reason Iguazu deserts for the sake of this new goal is specifically because he wants to become stronger than 621, and not want his obligations as part of the Redguns to get in the way of this goal of his, he goes independent.

--- Correction ---

Iguazu deserts the Redguns at Watchpoint Alpha, prior to the death of G1 Michigan. He doesn't desert the Redguns at the Wall, he only goes Away WithOut Leave. The reason for which he goes AWOL being to take independent work, as we see an example of at Grid 086. Outcomes of everything are still the same, I just mixed up the order.

Also;

Volta: "Iguazu, listen, like, Michigan really like cares about us...! It's like we're part of his family, man, just give him a chance."

Volta: *Gives Michigan a chance*

Volta: *Gets killed under the leadership of G1 Michigan*

It's really funny but sad.

It's also really funny and sad how effective at Yank-bait G1 Michigan was.

But it's illustrative of how effective it is to break down someone's expectations and feelings of self-worth to legit 0, such that empty platitudes like simply saying the right words, like the names of the expendables themselves or to bring in the medical teams after a battle (as if they wouldn't have come otherwise?), will leave such an impression that they think you really do care about them--even in despite of how worthless they obviously are~!

And all at the same time as your direct actions and orders lead them straight to their meaningless avoidable deaths.

What could be more cost-efficient for your employers than soldiers who're literally suicidal for you, right?

Ha!

--- ---

And not only does this decision directly lead to Iguazu not dying at the Wall, but, no longer squeezed under G1 Michigan's boots, G5 even directly improves as a fighter.

This is shown in how his AI differs between his fighting at the Gallia Dam--where he's overly defensive, constantly having his shield up, despite wielding two guns.

And then, later at the Grid--where he actually fights aggressively like his AC's loadout is built for.

The second major encounter with Iguazu is Watchpoint Alpha where he either fights you directly, and dies there. Or he hires Coldcall to kill you, and survives elsewhere. Again, this is an instance of Iguazu's legitimate determination towards his chosen goal directly separating him from life and death.

When he hires Coldcall, Iguazu focuses on his goal, and let's go of distractions like his personal pride and image.

Ridiculous, right? Iguazu letting go of his pride?

But consider how it's directly Iguazu's personal feelings that lead him to facing 621 personally. He doesn't *just* want to kill you in that instant, he wants the glory of killing you as well.

But the accolades at the end aren't what makes it worthy to pursue a chosen goal.

Iguazu wants 621 dead. And when he hires Coldcall, this is him coming to terms with pursuing his goal, regardless of his personal setbacks. Iguazu faces the fact that he personally wouldn't be able to kill you. And, because he comes to term with this setback, he finds an alternative method that would still lead towards fulfilling his chosen purpose.

To confirm, of course, Iguazu's purpose is really dumb and terrible. But it's not whether one's chosen purpose is 'a good goal' or not that the value of pursuing it comes from. The value comes from it being one you decided for yourself, as opposed to, for, for example, by a corporation's profits. (Not a coincidence narratively how Balam's forces, united most in their complete idolization of G1 Michigan, following *his* word no matter what even knowingly to their deaths, are the deadmost losers in the story.)

Unlike for example e621's chosen conviction, or Rusty's chosen conviction, (Also no coincidence narratively that G1 Michigan, who only exists as the weapon of his corporation and put out a bounty for his own assassination--expressing how he has no personal plans for the future and literally wants to die--is guaranteed to be taken out by either of these two, no matter what.)

It's not the loftiness of a goal that determines if it's of worth to decide upon one of your own free will and pursue it in the first place.

The 'value' of pursuing a goal is unrelated to what that goal itself is.

What makes pursuing a goal valuable, is the conviction.

You don't have to be smart. You don't have to be emotionally mature. You don't have to be a good fighter. You don't even have to be brave.

You just need to choose your purpose and follow it.

This is what the motif of 'wings' and 'borrowed wings' are all about in the story as well. It's about pursuing a goal that was chosen by someone else, versus pursuing a goal that was chosen by you yourself.

"They choose what to fight for, and take to the skies in flight."

"One cannot fly on borrowed wings" in this case literally meaning that if you pursue a goal not because you want it, but because someone else wants it, it will directly lead to your death.

Criticizing their "borrowed wings" is what Ayre and Rusty chastise the RLF for for solely repeating slogans and "not bothering to think [for themselves]."

And Iguazu, deciding he doesn't care about how he'd be seen by others, and only caring for the goal itself to be accomplished. Survives, where Coldcall dies in his place.

Coldcall, a far superior fighter to Iguazu. Dies, instead of Iguazu, because he was flying for Iguazu's purpose -> Fighting on borrowed wings.

Etc etc "this is hell, we're in hell!" and so on and in the Alea Iacta Est true ending of the game Iguazu, outta nowhere!, becomes the legit Final Boss of Armored Core 6.

How the hell did this 4th-gen AC pilot, otherwise a completely random nobody without a purpose not given to him by his employer, get to outer space and stuff, right?

Well, consider how the complete rando that was e621 does the same: Their personal conviction.

"But Iguazu only got to become the final boss out of dumb luck," right? ALLMIND chose him for little else but that he was the only old-gen Augmented Human that was still alive. If ALLMIND wasn't there, he couldn't have accomplished anything, so obviously it can't actually be meaningful.

But how would 621 have escaped Institute City without being rescued by Carla? How would we have escaped Arquebus re-education without the AC that Handler Walter secretly assembled left for us?

And, most relevantly here since this is the Alea Iacta Est route itself: How would 621 have known about V.II Snail planning to ambush you in Institute City without ALLMIND herself's very assistance?

C4-621 is, at a glance, just as much a recipient of dumb luck as Iguazu.

But thematically, it's not pure happenchance.

It's the results of the both of these characters continuing to fight for a cause they chose to believe in, no matter what.

So Iguazu survives. He survives the hijacking of Watchpoint Alpha by ALLMIND. And he even goes so far as to survive the hijacking of his own brain by ALLMIND, taking over the final boss even after being assimilated.

"What essential difference made ACs superior to unpiloted craft?"

The answer is simple -> One cannot fly on borrowed wings.

Unpiloted craft can never have a purpose that is actually their own. They exist only for the person who's wings they borrow--who's purpose they serve--who built them.

That's why piloted ACs are better. *Not* on borrowed wings, in this case, they can fly higher.

For C4-621, that chosen goal is to achieve Coral Release. (Since it's is still the mission you yourself choose that finally puts you on the Alea Iacta Est route or not, it fits within the theme of free will. Even though, as a videogame, there's an obvious limit to just *how* much free will the player is actually able to express. Within the story, however, when 621 chooses the mission to begin the path to an ending, that's them deciding for themselves 100% that's that the goal they want to achieve, no matter what.)

For Iguazu, that chosen goal is to kill you. (The goal he wants to achieve, no matter what.)

And so, because he was not flying on borrowed wings. Iguazu survives fucking everything. Stupid wings, yeah. But that just shows: What matters is only that they were his own.

Even against the most powerful super duper AI mastermind that ALLMIND was, the biggest loser on Earth, G5 Iguazu, survived.

Where even she is made to give way to Iguazu's conviction -> Killing e621.

Hammering this point home is why "I'm only here for what *I* want! I don't care about ALLMIND's goals, just my own!" is basically the only thing Iguazu says across like 2 entire 3rds of the final boss.

Iguazu's chosen goal is not ultimately successful.

But it wasn't whether or not Iguazu ultimately killed 621 in Rubicon's exosphere that lead to him not dying at the Wall like G4 Volta, or at Watchpoint Alpha like G1 Michigan and Coldcall, or upon the destruction of his physical body by ALLMIND.

It was his conviction that lead him past those things. His WINGS!

He chose what to fight for, and he fought for it.

On the wings of his free will, Iguazu flew above even the very clouds of Rubicon itself.

And that's why he was the Final Boss.

The only thing able to finally kill him being the person with a conviction even greater, C4-621.

(As a sidenote; Taking account of the main moral of Armored Core 6 really puts into perspective how many trillions of times it gets repeated explicitly across the game lol.

VS Rusty, VS Rusty when he calls you "power without a purpose," VS Cinder Carla, VS Handler Walter, Ayre's description of what the name "Raven" is literally supposed to mean, etc.

They all talk about how you've chosen your path and you'd made sacrifices to get this far and you finally have a conviction that is your own and how big a deal that is and so on.)

#tlgtw ooc#g5 iguazu#my boyfriend who hates me g5 iguazu#armored core 6#armored core 6 spoilers#alea iacta est#armored core lore#g1 michigan#it is way late at night and I am stressed out about computer problems and the only way for me to feel better#is to get as many thoughts out of my brain as possible. I'm not even really sure if this is coherent or not#but that's okay#as far as I'm concerned anyway e621's conviction is just seeing G5 Iguazu again gehehehehhehehe

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

you guys know that "landlords are leeches get a real job" is a haha funny bit you say to illustrate the hypocrisy of the rhetoric surrounding work and what qualifies as 'contributing' to capitalist society and not a coherent leftist belief right? you guys are saying that because it's funny to watch landlords sputter to come up with a response to the kind of attitude they have always subjected tenants and renters to and not because you genuinely believe your worth is determined by the money you earn under capitalism, right? you understand that once you believe it is possible for someone (even landlords) to be a 'leech' on society if they arent working (or aren't working enough, or aren't doing the right kind of work, etc), this will bleed into the way you think of everyone else too, right? you guys know that legitimate and meaningful critiques of landlords are not and can never be based on whether or not they are working because that is irrelevant to the fact that they own property for the express purpose of charging other people for access to shelter, which is a basic human need and shouldnt be controlled by the whims of Some Guy just because its his name on the deed... right???

#good idea generator#preaching to the choir on this one for sure i just sometimes see interactions on this website that worry me#like babygirl what about people who cannot work due to circumstance ability or both? ppl who will NEVER work?#do u think theyre leeches too??? you can SAY 'oh well i obviously dont mean those ppl' but like#the rhetoric was designed to be used against Those People specifically to turn YOU against THEM when youre on the same side#its funny to use against the ruling class but its not like. effective except as a snappy comeback#additionally what about landlords who do work?? who have dayjobs??#landlords who do live in the property they rent. who rent out bedrooms or basement suites or the like#are these people no longer leeches? do you think this system of land ownership is fine if all parties have jobs??#do you see what i am saying. it is not possible to critique capitalism as a system#while relying on the frameworks capitalism uses to prop itself up.#you will only EVER end up tacitly supporting the very thing you declare youre against

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

fwiw that rude commenter is a transphobe, a post a few down on their blog is real blatant (and in that vein I think their comment was less a judgement of your anatomy and more saying Charlie is 'too' muscular/angular)

It's rude and out of pocket REGARDLESS but I also think you're a little hard on yourself! You even said, you hadn't illustrated exactly what you were after with her, and you hadn't intended for a collection of doodles you happened to still like to blow up. You're entirely right that we should all be drawing more than conventionally attractive people, but idk. It's a process and you're a great artist who's working toward it! Don't feel like you have to answer this btw I mostly wanted to let you know that commenter was a double idiot and started rambling. Hope you have a lovely day!!

oh absolutely! i have a feeling you're right abt what they meant considering i saw the transphobic comment they made a couple posts down on their blog lmao but i wanted to add that part anyway. and i appreciate your words a ton, but dw im not hurt or upset! i get a lot of weird comments all the time, i just wanted to use that one as a platform to bounce off of a thought ive been having lately. i wouldn't post a negative remark like that unless i wanted to use it for something. the actual comment was mostly irrelevant to the point i wanted to make, which is also not meant to be super serious, just a thought soup to stir around

and i mean my interpretation of my art as purely objective, i think its important to think critically about yourself and in general. from an objective standpoint, i dont believe the way shes drawn is too out of the norm and is fairly tame (disregarding her ox/bull parts lol), thats basically what i was aiming for with that section. i constantly get stuck in a rut without improving by much because im usually just drawing to doodle after a school day and not rlly with any purpose. i tend to keep drawing the same things out of habit and it gets stale really quickly. so i know my faults and im rlly looking forward to getting better!

also rq, what you said about how we need to draw more than conventionally attractive people- while i do agree with that, in my post i was more saying its important for people to be more open-minded about how they view gender expression and attractiveness in general, myself included! i dont think how i drew charlie was very revolutionary, but ive seen so many tags speaking otherwise. which is either reflective of how small the bubble is for whats acceptable or maybe i have a skewed perception of things? for example if having a bush or something is gender envy we need to look at ourselves. bush is so normal to me. (which i dont if thats what even drew ppl to it BUT. just as an example). would those same people say the same if i drew a very fat woman with a beard, unibrow, etc.? i have no idea. but i have had my eyes opened so many times before its incredible. little things ive never thought about before through new perspective. so thats why i want to encourage it too. i hope that makes sense. thank you so much i hope you have an equally lovely day!! 🫶🫶

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

regarding that ask i got about how most ppl see Yoi as like plot irrelevant, her first story quest is literary the best and closest explanation\illustration of makoto’s ideas of transience we get in the game, even better than in raiden’s second quest. Yoimiya is literally Inazuma’s spiritual end game, hoyo just didn’t fucking structure it coherently

Yoimiya: It was by chance that I happened to be born into the Naganohara family, so it was by chance that I ended up learning this craft from my pops.

Yoimiya: It's also by chance that I've met so many people, learned so many things, and discovered that people associate watching fireworks with the things that are most precious to them.

Yoimiya: Fireworks that disappear in a flash of light are probably the furthest thing away from the eternity that our Shogun desires.

Yoimiya: But people's feelings don't just disappear, and it's those feelings that give fireworks their purpose. If nobody wanted to watch fireworks, then they wouldn't exist.

Traveler: That's another kind of eternity.

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think your takes an AI are pretty interesting, especially as someone who’s not in a very tech-related field. So since you’ve invoked Searle a few times wrt to the AI art debate, I’m wondering what your thoughts on his position are? As someone who deals with neuroscience/philosophy to some degree, I’m inclined to agree with some aspects of his argument (namely that you couldn’t reproduce the human mind with a computer programmed to like replicate human cognitive processes; “the empty brain” by Robert Epstein is a decent illustration of that point). But I’m also less versed in just like how ai functions so I’m curious to hear your take on Searle’s philosophy — I don’t have a specific question here, I’m genuinely just curious about what your thoughts are more generally.

the question "can an AI ever be truly sentient in the same way as a human?" is extremely contentious and has given rise to two schools of thought over the last half century

"weak AI" proponents assert that AI is fundamentally incapable of being sentient/self-aware in the same way that humans are. regardless of how advanced they get, the way computer programs "think" is completely alien to us, and there's no way to see inside their head to determine if they actually understand the things they're spitting out or if they've just correlated arbitrary inputs with desired outputs based on statistics

"strong AI" proponents point out that the entire second sentence of the above paragraph applies equally well to other human beings, at which point the weak AI proponents get extremely mad and start ranting about the necessity of a human soul (which is invisible, massless, and undefinable, but also a prerequisite for sentience). John Searle was the first proponent of this idea back in the mid-20th century, which is why i frequently curse his name when this argument resurfaces

jokes and snide jabs aside, the core disagreement between the two camps hinges on this idea of an entity truly ""understanding"" the output it produces. google "chinese room thought experiment" if you're interested in learning more, but here's the gist of the issue as i see it, with a translation from the generalist perspective to the current debate over AI art programs like DALL-E

problem: one of the arguments against an AI ever [being sentient, even after passing the Turing test]/[producing "true art"] is that it could simply be using statistics to correlate certain inputs with the outputs most likely to lead to a desired outcome, like [talking in a way that passes for human]/[making art that elicits specific emotions in the viewer]. however, because we fundamentally don't understand a LOT about how human consciousness works, and because humans can only ever experience the world from their own perspective, there is no way to definitively say that these same observations don't also apply to other humans, who we'll just assume are sentient as an axiom (no brain-in-a-jar theory this time, sorry). furthermore, when you simplify human [sentience]/[artistic talent] down to its barest bones, it really is just a nonstop process of correlating inputs with actions that can be taken to arrive at a specific outcomes. sure, we don't know "how" AI thinks, but we also don't really know "how" other humans - or even ourselves! - think. what's to be done?

strong AI camp answer: "since it's fundamentally impossible to peer at the inner workings of any entity's mind and ascribe meaning to the connections and neural firings being made therein, any comparison between the [sentience]/[artistic talent] of AIs and humans must be judged solely on the [conversations]/[art] being output. if the output of the two parties is mostly indistinguishable, then one is forced to conclude that any differences between the inner workings of the entity's minds is irrelevant to the question at hand. if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then for all intents and purposes, it is a duck."

[weak AI camp]/[Patreon artist] answer: "well, i know I'M definitely [sentient]/[capable of producing meaningful art], and clearly other humans are, but computers definitely AREN'T for reasons that make me uncomfortable to explore. clearly, this is explained by a common factor that humans share and AIs lack: [a soul]/[literally just being a human and not an AI]. man, this philosophy shit is easy!"

tl;dr: sentience and artistic talent are not uniquely human, and if you feel the need to defend them as such, you should probably examine your sense of self-importance and what it's founded on.

#none of this touches on any potential economic impact of AI art#im strictly referring to people hand-wringing over the death of art as an expressive medium

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't care about how beautiful or ugly AI pictures are.

Before you read this, keep in mind that I have taken History and Culture of the Arts classes (from ancient history to the days of today), History of Drawing classes, as well as studying on my free time because this quite literally my area of expertise. I am also finalizing my license degree in the artes field.

Art in it's many forms is a form of communication. It doesn't matter if it's paintings, illustrations, video games, books, architecture, sculpting, pottery, you name it. It's how each artist/writer/musician views and shares the world, how each person has an unique approach reflecting their own life experiences and tastes.

It's how one writer drafts poetry upon the ocean, while another fears it, and a third one merely views it as a body of salty water. How one artist tenderly paints the hands of a portrait while another slaps a couple of brush strokes on it and calls it a day. How some do a lot of messy and sketchy charcoal lines, while others prefer a pretty and rendered piece. How some prefer the melody of the violin, while others the beat of the drums. It's how you draw backgrounds, what backgrounds, people, which people.

The details you choose to put in - a flower pressed into the background, with no importance to the picture or environment but still consciously put there, for a reason or another; the way a character shows their emotions, in ways we rarely think about but the author knows intimately; how a game developer hides little easter eggs in their game and delights in those who find them and get the reference...

How we still talk to Homero after he's been dead for millennia. How we see ruins from civilizations past, where people once had their first love, first tragedy, last breath. How now we use digital art to depict animals, the same way ancient humans used stone to carve them upon walls.

A machine has no thought. It copies without meaning. You cannot talk to it or marvel at the details it puts in, because they are mindless. The machine puts in a rose because the artists it references also put in roses. It draws a blue ocean when you write prompts for mermaids because mermaid = water = blue. It takes from the humans before it and doesn't adapt it or build upon it, for it cannot combine two completely different - and at first sight irrelevant - things on its own without it having been done before. This is not Detroit: Become Human. The AI is not alive or intelligent. It's a tool, the same way your phone or microwave are.

I love pretty art. In fact, as someone finishing my license in the arts field, I would consider myself quite elitist. I have a strong love for Pre-Raphaelite and Noveau art, and classical architecture. I would suck Alphonse Mucha and John William Waterhouse's dicks if they so commanded, if I could get a small napkin drawing from them afterwards. I don't like XX century art movements like cubism or dadaism. I find them ugly, and they go completely against my aesthetics.

But as much as I hate those, the artists who made them had a story to tell. They had hands and a brain. They put it forward in their own way, with their own language, based on their own likes and dislikes, happy and tragic memories.

A machine has none of the touch.

Art is not the same as working in the mines or in the sewers. It's a human connection. It has been here before we even called ourselves human, it has been here when there was more than one human species walking the planet (for the homo sapiens wasn't always alone). There ir no need to replace it.

Does AI artwork has it's uses? Well, I believe so. I believe there could be ways to make it work. A tool is a tool, after all. But I have yet to see it being used in a ""good"", innovative, useful way.

There is no TLDR. I cannot contain what I just wrote in few words. It would defeat the purpose.

#ai#ai art discourse#ai art isn't real art#anti ai art#my opinion if you disagree ignore#unless you have the bare minimum of art history I don't believe I can have a conversation with you on this topic#I dont care how much faster AI is#I dont care if you think I'm gatekeeping art#shoving prompts into a machine isn't creating art the same way me shoving a pre made meal in a microwave isn't cooking#if you have a disability there are many different types of art you can follow so don't even try to use that as an excuse

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

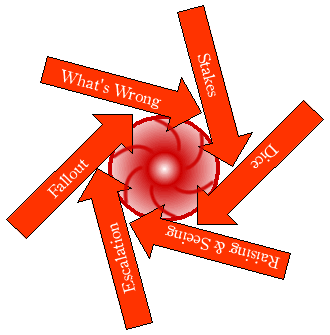

Plumbing the Depths: "The Fruitful Void"

Watch the video for context – I can't spare the space to summarize the whole debacle here. What's important for my purposes is that the "fruitful void" that Milton describes around 7m19s is... not what Mulligan is talking about with his tortured "stove" metaphor.

The "fruitful void" refers to the idea that a system should take care not to accidentally answer the focal questions that are supposed to be answered through play. Baker illustrates this with a diagram describing the rules for the now-defunct Dogs in the Vineyard:

At the centre of the diagram are the unanswered questions of the game. The mechanics surround them, support them, and direct play toward them, but the mechanics must never directly answer those questions – or else the game would "play itself" (at least with respect to whatever topics are in the middle of the diagram, there). Like in Snakes & Ladders, the participants would have nothing to add.

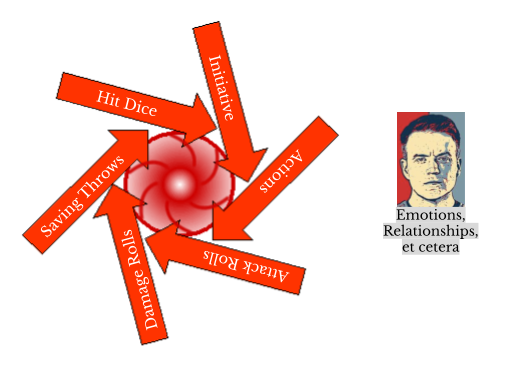

Now, Milton is indicating that he thinks that because D&D doesn't have rules for things like "emotions, relationships, and character", that must mean that those things exist within D&D's fruitful void. But what he's not realizing is that, in addition to the fruitful void at the centre of the rules, there's also another, regular-ass, non-fruitful void that exists entirely outside of a game's rules. Here's a diagram for D&D:

Over on the left, the "fruitful void" is, of course, combat. All of D&D's rules surround and support combat, directing us toward it. If we engage with those rules (if we're taking turns in initiative order, using the actions, rolling saving throws, adjusting our hit points, and so on) then we are necessarily also answering D&D's focal questions, like "Will we survive? Will we triumph? How will we do it?" Even when we use those rules to the absolute fullest, we will never be obliged to talk about our characters' emotional journeys or the arc of their relationships.

By contrast: if we are managing to avoid answering the focal combat questions, then we're probably disregarding many or most of the rules of D&D. Perhaps instead we are out over on the right of the diagram, in the space where D&D's rules are largely irrelevant. Trying to use the rules of D&D to play a game in this space is... well, it's a bit like trying to eat your stove. Stoves are related to eating, but they're not for eating – you need other things, like food, to do that.

These metaphorical "other things", of course, include what Milton describes as "the very sophisticated and finely honed set of improv rules that [Mulligan] has running in his head". This system in Mulligan's head – and not D&D – is the primary game system upon which Dimension 20 runs. And that works wonders for Mulligan! But for those of us who are not trained, experienced, professional writer/actors, trying to use a system that only exists in Mulligan's brain is challenging. What the fans of Dimension20 need, and what Mulligan and Milton therefore ought to promote, is a system with a fruitful void that encompasses those emotions and relationships that Mulligan finds so easy.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

tell me more about angel wn pls

Angel's character arc is, thematically speaking, primarily about grief. Grief for the community he was denied, grief for the relationship he couldn't have with his maternal figure, grief for Dido/his relationship with Dido, grief over his own failures, grief for the relationship he couldn't have with his children, grief over the potential futures that the past has killed.

His arc basically follows, vaguely, the 5 stages of grief, as well as (even more vaguely) the 12 steps of recovery. (Eddie's arc is similar, but is more about recovery than grief.) The bulk of Angel's story is Denial.

He also is a representative of grief in the other characters' arcs. For Eddie, Angel's narrative presence (but in-universe absence) in Curse The Messenger is used to illustrate her grieving for her lack of childhood as well as her more literal grief for her parents and her guilt and regret over people she perceives herself to have failed to save. For Fred, Angel in CTM also illustrates xyr grief for a lost childhood, as well as xyr grief-driven fear of abandonment.

He's not in Gilded Verdict at all. Incidentally, the main characters in that one either don't have anything they grieve (Evan) or project their feelings externally to such a pathological degree that they don't feel grief so much as things like resentment or unfulfilled entitlement (Lily). A character is a symbol just as much as any blue curtain.

In The Vanishing Point, Angel has only negative character development, spiraling deeper and deeper into avoidance. He can't bear to acknowledge his losses or his mistakes, and makes them immeasurably worse by obsessively denying them. This is the bulk of his on-page character arc, really, and it is entirely in the Denial stage of grief and well out of reach of the "admitting he has a problem" stage of recovery. He ends the book at the lowest low achievable in the witch noir universe, the ultimate and rockiest of rock bottoms.

For Dido in TVP, Angel represents her grief over the life she thought she'd have before her schizophrenia onset. She continues to grieve herself in other ways, with Angel as the narrative proxy for her feelings (just romantic lead things) throughout the book. At the end [SPOILER] more literally, thus making Angel also the proxy for [SPOILER].

In a slightly more literal sense, every single character who interacts with Angel will lose him. Every single relationship he ever has ends.

Then at last in Latchkey Craft, Angel gets to have his own POV. LC is basically Angel speedrunning the 5 stages (because he is still firmly in Denial even at the beginning of this book, 13 years after hitting his rock bottom). There are three other characters in LC that aren't in the rest of the series at all because [SPOILER], and each of them represents a different direction Angel could go from here.

Clara is the possibility of Angel stubbornly - and now consciously, purposely - staying in Denial and never admitting he has a problem, and the consequences thereof, repeating the same mistakes in the same way forever.

Kapua is - er, actually I'm looking at the 12 steps right now and fuck's sake these bitches be Christian as hell lol, we are ignoring like 8 of these steps because they're fucking irrelevant and also frankly antithetical to the other ones?? anyway-

So Kapua is steps 1 (admitting there's a problem), 4 (naming the problem and facing it directly), two thirds of 5 (saying it out loud), and 10 (committing to face up to relapses and other problems in the future). He also to some degree is Bargaining and Depression. As you can see here, there's a reason why he and Wapo are a package deal.

Wapo is steps 3 (deciding to make a change) and 8 (making amends), as well as stages Anger and Acceptance. Where Kapua is a more internal and less outwardly responsible path for Angel, Wapo represents Angel becoming more diligent and proactive in his life.

Clara, Kapua, and Wapo are all [SPOILER], and my goal is to leave it up to reader interpretation whether or not they are [SPOILER]. For this reason, and because the plot is so Man vs Self, I think LC will be the hardest book of the series to write.

witch noir taglist: @haectemporasunt @jezifster @blackhannetandco @fearofahumanplanet @godsleftarmpit @littlehastyhoneydew @rainbowabomination @antihell @isherwoodj @marrowwife @ashen-crest @wildswrites @ceph-the-ghost-writer @garthcelyn @muddshadow @cohldhands @unrealistic-android

Sign up here to be tagged when I post about this project.

#jack facts#i think i've said most of this in less detailed bits and pieces but#here it all is together and in as much detail as i'm willing to share pre-pub lol#jack chats#angel wn#witch noir#writing process#horror tag#tragedy tag

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

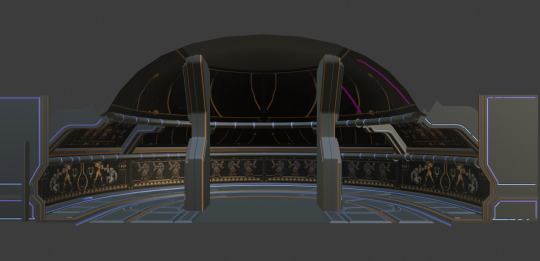

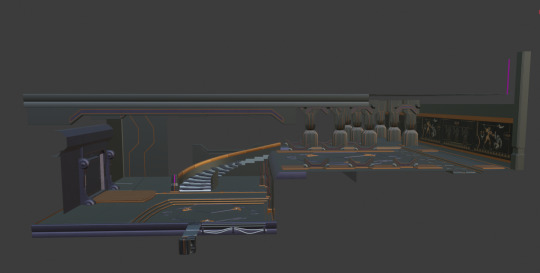

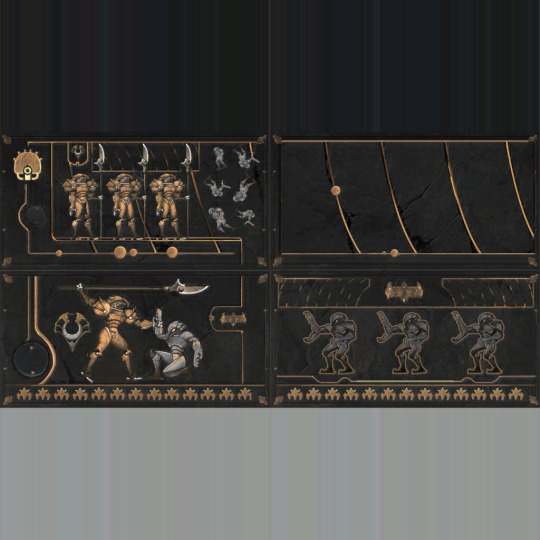

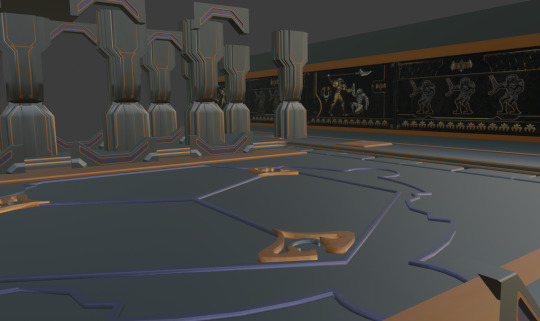

I'm going to explore a few more background elements that I'm personally interested in. This time, we're returning to Ferenia, home of the murals.

Chances are, you'll exit Ferenia for the first time using the elevator (not pictured) in this room. You may immediately notice the mural on the back wall. I'm not going to zoom in on it here because it appears in another room that's easier to shoot.

When you enter Ferenia from the trolley station, you'll enter a large fortified door that leads you into this room. Let's take a look at the walls.

There are Space Pirates on this mural.

Here, we see a confrontation between a Chozo soldier and a Space Pirate. The soldier is identified as a Mawkin tribesman with the tribe's sigil to the left of the figure. This symbol appears on the banners and flags scattered throughout Ferenia. The soldier is holding the pirate's right claw shut. The soldier has their spear raised to strike, and the pirate is kneeling, indicating a submissive position. We could speculate about whether or not the Space Pirate in this mural is acknowledging the Mawkin's superior prowess, but that's irrelevant: it's kneeling, and there's a weapon in its face. The Space Pirate is losing this battle.

There's a pattern of small, repeating symbols beneath the main scene in both of these murals. I'd be glad to hear outside input as to what they could be, but I think they're Mawkin fighter jets.

These first two panels are repeated three times on the upper floor of this hallway.

Here's a shot of the full length of the second story mural from behind. There's a third mural on the ground floor of this hallway.

Central to the piece is a group of Mawkin soldiers, again identified by the sigil positioned above the leftmost soldier. On the right, we see the Space Pirates falling. If you've played Metroid Dread, you'll recognize this symbolism from another mural (which we'll cover later) as symbolic of a group of people dying. The image is quite literally depicting the fall of the Space Pirates.

You'll notice a symbol on the left that looks like Mother Brain. Here's the texture in full.

There's a lot to unpack here. Mother Brain isn't massive on the canvas, so hierarchic scale doesn't deem her the Most Important Guy Here, but she's here, and she's involved.

Her representation here might mean she informed the Mawkin of Space Pirate activity near their planet, territories, etc. I don't think it'd be too far-fetched to assume Mother Brain, a Chozo supercomputer built by a tribe of Chozo, would be able to communicate to Raven Beak, the leader of another Chozo society, that "hey, your neighboring planets are being overtaken by these hivemind organisms, just thought you'd like to be aware of that".

It could also mean that the Mawkin know that she's the leader of the Space Pirates.

The symbolism of the Space Pirates falling from the sky in the Mother Brain section of the mural and the Mawkin soldier with the raised weapon in the panel with the kneeling Space Pirate indicates to me that the Space Pirates aren't submitting to the Mawkin, they're being defeated by them. As established by the other mural, Group of Guys Falling indicates large-scale killing or the killing of an opposing group, as armies do during war.

I've seen people on the Metroid subreddit theorize that Mother Brain and Raven Beak could have conspired together at one point. People point to the fact that the Space Pirates used a black hole generator (which they don't usually have access to) to bypass Zebes' planetary defense systems and the fact that Raven Beak is capable of throwing little black holes during combat to illustrate the idea that the Mawkin could have provided such a weapon for that purpose.

It seems plausible, but now that I've had the chance to look at all the map bits themselves in Blender, I don't think that's what this mural is conveying. People took the kneeling Space Pirate to mean "they submitted to the Mawkin", but as I've stated before, the raised weapon (indicating continued aggression despite the kneel) combined with the wholesale slaughter of Pirates in the Mother Brain panel lead me to believe otherwise. I don't think it's impossible for Raven Beak to have been the Pirates' arms dealer at one point, but I don't think that's what this mural is trying to clue us in on.

The best I can come out with is "the Mawkin either know Mother Brain is the leader of the Space Pirates, or she was involved in directing their attention towards the Pirates".

Now that I think about it, she could very well have misdirected the Mawkin so they wouldn't come to Zebes' aid during the Pirates' invasion. This doesn't have anything to do with the contents of the murals themselves, but it's a thought.

Anyways, with the mural out of the way, let's talk about the floor.

I've never noticed these little flourishes before, and I think they're neat.

I'm not certain what the significance of the arrangement is, but I do know that the yellow bits are the Mawkin sigil done up all fancy with clever use of negative space. It conveys what it's depicting without using a whole lot of detail.

This post was originally supposed to be about the floor, but the length of the mural actually surprised me. I knew there was a mural on the bottom floor, but I never noticed the wall on the second floor until recently.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lessons Learned From Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

III. How to experience spontaneous, self-directed learning

Frankly, I don’t believe that Ferris, Cameron and Sloane would have spent their ‘day off’ better in school. Consider everything they pack into it: they ascend to the top of Willis Tower and observe the ant-like movements of workers 1400 feet below; they stare at the frenzied floor of the stock exchange and learn the sign-language of its traders; they take in a baseball game at Wrigley Field at the exact moment they should be enduring a gym lesson. Far from blowing learning off, Ferris’s rich schedule of activities achieves anything you could want for an educational field trip. The point is well made in a scene filmed inside the Art Institute of Chicago in which Ferris, Cameron and Sloane hold hands with a group of much younger children who are there with their teacher – everything they do mirrors the curriculum being delivered to their campus-bound classmates, the difference being how much more engaged they are.

youtube

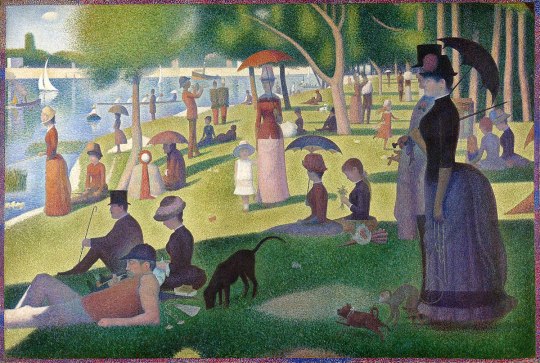

John Hughes offers a comparable opportunity to the film’s audience. During the same gallery sequence, lengthy shots of masterpieces by Edward Hopper, Amedeo Modigliani, Jackson Pollock and Pablo Picasso fill the screen to an instrumental version of the Smiths’ song ‘Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want’. There is no clear motive to this montage: it doesn’t advance the film’s plot or match the frenetic pace of its comic hijinks; the art is celebrated for its own sake. Perhaps Hughes is doing for Ferris Bueller’s Day Off what galleries do for cities the world over, providing a respite to the bustle and purpose of everything else. In narrative terms, the scene is a prime example of what Timothy Morton means when he says that a ‘middle’ (development) is characterized by a slow, meditative pace and a feeling of absorption. In educational terms, the scene supports a claim for the value of the unplanned (much of it was improvised) or the apparently irrelevant. It can be frustrating for English or Arts teachers to vindicate their content in ‘lessons planned for … audit and accountability’, sacrificing ‘the unfinalisable struggle for meaning’ at the mendacious altar of ‘the easily-measurable’. Art, music and literature are illustrative of the ways in which meaning can be a slippery, mercurial thing; when they appear in an educational context they can also force a distinction between usefulness and value, reminding us that many of the things we place the highest value on are, from a utilitarian perspective, useless: chocolate, wine, sunsets, love. Hughes’s Art Institute sequence invites us to consider the flaws of an education system so staid and inflexible that it requires a ‘day off’ for students to reckon with something powerful enough to influence their perception of themselves and the world around them.

It is just such a reckoning that occurs when Cameron stands alone before Georges Seurat’s pointillist work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. The painting depicts a group of well-to-do people promenading by the banks of the river Seine in the late 19th century, the men in top hats and the women in bustle-heavy dresses. Everyone in the painting seems together yet somehow alone, and a small girl dressed in white stares at the viewer from the centre of the canvas. Cameron fixates on this little girl – she is the only figure in the painting who makes a connection to the world outside its frame, and so the raw perceptive powers of childhood are contrasted against the dulling superficiality of adulthood. A teenager hovering between these two states of being, Cameron’s wrapped expression suggests that he is young enough to identify with the child but old enough to fear the looming demands of adult life. The film cross-cuts between increasingly close shots of his face and that of the girl, who on closer inspection appears to be wailing in distress. Eventually, Cameron’s eyes and the specks of paint on Seurat’s canvas appear in such extreme close-up that they cannot be resolved as themselves – they become abstract details of shape and colour.

It’s an ambiguous but quite moving sequence of film, especially when set inside of a breezy, feel-good comedy. If there’s a point, it may be that Cameron sees his own anxieties reflected in the girl’s anguished face and either he or the audience (or both) are made aware that overwhelming pain can obliterate identity. Hughes alludes to this in an audio commentary recorded for the film’s DVD release:

The closer he looks at the child, the less he sees with this style of painting. The more he looks at it there’s nothing there. He fears that the more you look at him there isn’t anything to see. There’s nothing there. That’s him.

Erik Erikson’s seminal research into identity formation considers that emerging adults experience a dynamic interplay between identity synthesis and identity confusion: while most of us use the process of ‘trying out’ possibilities to determine an internally consistent sense of self, some experience an arrested development in which a fragmented or piecemeal selfhood does not support decision making. On this basis, we might consider Ferris’s play-acting to be an example of normative behaviour leading to identify formation. Cameron, on the other hand, appears to be enduring an atypical crisis: believing himself to be dying from an incurable disease, immobile with anxiety at the wheel of his car, staring in horrified recognition at the deconstructed face of Suerat’s child, he could be said to exemplify what James Marcia calls ‘identity diffusion’: he does not enjoy exploring options in the way that Ferris does, nor does he make a commitment to any of the possibilities lain before him. When an incredulous Ferris asks him to acknowledge all that he’s seen and done on his ‘day off’, Cameron’s laconic response is, ‘Nothing good’.

Perhaps we should resist the temptation to psychoanalyse a fictional character as though he were possessed of a ‘real’ inner life. Cameron has more depth than Ed Rooney, but he’s not Hamlet. Ferris is the character you want to be, but Cameron is who you think you are (or fear you might be). Because you identify with him, there’s a temptation to project your psychology onto him. This might lead to the sobering realisation that you share some of his issues, but it’s worth remembering that Cameron is also a more perceptive individual than his famous friend. It is his depth and sensitivity that awe him when confronted by Seurat’s painting. The moment is almost epiphanic: what could be more absorbing than seeing yourself staring back at you from a hundred-year-old work of art? Ferris and Sloane enjoy their ‘day off’, but Cameron has a life-altering encounter, despite his claim of not having seen anything good. At the end of the film (and in a revealing act of growth) he resolves to confront his authoritarian father. Eleanor Harvey, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, considers there to be a direct link between his experience of the painting and the way the arc of his character resolves: ‘That encounter with the painting … gives [Cameron] courage to understand that he can stand up for himself’. Not a bad lesson to have learned on your day off.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think you're being a little too generous towards the DE piece- I ended up watching it and like maybe this would be a different conversation if like Kurvitz was heinously criminal or something but all the complaints from employees were like Miyazaki level stuff- which isn't *good* or anything and Kutvitz should be criticized for it, but the video keeps framing it as though maybe Kurvitz shouldn't get the ip back because of it and like even if he was heinous you're still talking a court case with potential to have some pretty wide reaching affects on creator rights and ownership. I think itd be one thing to have a piece letting the workers have a say on their work experience and being caught in middle and like fan harassment etc etc which it partly aims to, but then why is Kurvitz and the estonian money man being interviewed? It actively advertises itself as being a "both sides" piece and as finding "nuance" on "the issues" (and thus is fair to judge on its stated intent) but the "issues" in question is the lawsuit on ip ownership which is imo very clear cut morally- I don't think they neccasarily meant to with a malicous intent but it purposely focuses a lot on Kurvitz character in an attempt to find said "nuance" when its pretty irrelevant to the actual issue and it just makes them patzies for ZU/AM's corporate takeover. I fundamentally refuse to buy into the idea that this is any way about Kurvitz's management when they could of fired him lol and I think the whole piece is tainted by this pig-headed and hopefully ill-fated view. But different reads here I guess and if Kurvitz was just like fired and kept his work this would be a piece I'd be way more into ie collaborative endeavours.

Yeah this is a very reasonable position, I mostly agree. When I talk about the 'editorial' content being wishy washy and kind of stupid, I include things like the marketing of the video and host's framing of the big picture. It's very pathetic and immensely frustrating. Please don't mistake me saying the video is a solid piece of journalism for me remotely endorsing its conclusions.

My sticking point is a practical one: how do you meaningfully report on a story as convoluted, messy and acrimonious as this without exploring each claim and counter-claim in its context? This isn't a 'pet shelter vs. league of racist cat eaters' debate, it's an investigation of factual claims around a series of pending legal actions. I agree that the video uses its material to weave a deeply toothless narrative that serves the studio heads more than the employees they purport to be 'in solidarity' with (lol) but I don't think presenting the material itself is without value. It illustrates the vacuity of studio za/um's claims, which are relevant in a tortured way if kompus wants anyone to believe the team were just fired on merit by total coincidence.

And however we feel about it, a version of the video that didn't address the 'workplace bullying' narrative, or didn't speak to studio employees, would immediately have been attacked on credibility. It sucks shit on a whole second axis because it's similar logic that leads the host to go "this aint it chief!!!" in response to kurvitz refusing to take his bait. This is just the nature of the repulsive accountability performance culture we live in unfortunately.

3 notes

·

View notes