#fossil spiral shell

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Fossil Goniatite in Matrix – Devonian Period, Erfoud Morocco, Authentic Prehistoric Specimen

A stunning and authentic Fossil Goniatite preserved in its original limestone matrix, dating to the Devonian Period, approximately 390–400 million years ago. This specimen comes from the Erfoud region of Morocco, an area renowned for its rich fossil beds and well-preserved marine invertebrates.

Goniatites are extinct ammonoid cephalopods, ancestral relatives of modern squids and octopuses. They are characterised by their tightly coiled, planispiral shells and simpler suture patterns compared to later ammonites. This fossil offers excellent detail of the shell's spiral and internal chamber structure.

Fossil Type: Ammonoid Cephalopod (Goniatite)

Geological Age: Devonian – Middle to Late Devonian (Givetian-Frasnian)

Formation: Likely Maïder Basin marine limestone beds near Erfoud

Depositional Environment: These goniatites lived in warm, shallow marine environments of the ancient Paleozoic seas. After death, their shells settled into fine carbonate sediments that later lithified into limestone. The conditions allowed for excellent preservation of both external and internal shell structures.

Morphological Features:

Tightly coiled spiral shell (planispiral)

Distinct chamber divisions (septa)

Suture lines typically simple and curved (goniatitic)

Presented in limestone matrix, sometimes with associated fauna

Notable:

Classic example of early ammonoid evolution

Attractive fossil suitable for display or study

Collected from Morocco’s famous Devonian fossil beds

Photo shows the exact item you will receive

Authenticity: All of our fossils are 100% genuine natural specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity. Please refer to the scale image for sizing – each square or cube represents 1cm.

This Devonian Goniatite fossil from Morocco is a beautifully preserved relic of Earth’s ancient oceans and an excellent addition to any fossil collection or educational setting.

#Goniatite fossil#Devonian fossil Morocco#fossil cephalopod#Erfoud fossil#matrix fossil#goniatite ammonoid#prehistoric marine fossil#fossil spiral shell#Morocco fossil specimen#genuine goniatite#collector fossil ammonite#orthoceras and goniatite#fossil display plate

0 notes

Text

6 larger Turritella fossils spiral snail shell gastropod internal molds

#turritella#snail shell#gastropod#gastropods#mold fossil#spiral#snail shell fossil#fossil#fossils#fossilized#png#transparent#paleontology#prehistoric#paleoblr

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's already shaping up to be a good vacation :)

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ammonite fossils

I have two fossils, each of which show just a little bit of iridescence when they hit the light just right. One has some crystallized interior structures which I found very interesting. I enjoy that they each offer a unique view of shell structures (interior and exterior)

#ammonite#witchblr#grimoire study#witchcore#diary entry#witchcraft#fossils#fossil collection#shelly fossilian#fossil#ammonite shell#shell#witchy#spirals#spiral shell#my post#my pictures

1 note

·

View note

Text

My instagram explore page 🌀

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Photo

(via "The Marine Spiral - A Tribute to the Nautilus Ammonite" Metal Print for Sale by OLena Art ❣️) "Luminous Depths." This stunning artwork showcases the detailed structure of an ammonite fossil, capturing its spiraled shell in all its glory. The warm oranges and browns at the center transition seamlessly into cooler blues and purples at the edges, creating a mesmerizing display of color gradients. The luminescent quality of the shell gives it a lifelike appearance, while the deep blue background makes the fossil truly pop. Each chamber is meticulously defined, revealing the fossil's natural geometric patterns and beauty. Dive into the depths of history with this captivating piece.

#findyourthing#redbubble#ammonite fossil marine creature Luminous Depths detailed structure spiraled shell color gradients luminescent deep blue background geometric

1 note

·

View note

Text

Random PNGs, part 217

(1. Spiral of shells, 2. Janus head from whale vertebrae, 3. Crinoid fossils, 4. Ceramic art by Dominique Mercadal, 5. Glass model of amoebae by Leopold & Rudolf Blaschka, 6. Slime mold (Stemonitis), 7. Hakutaku by Miyagi Gengyo (1958), 8. Slime mold (Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa), 9. Yup'ik seal float (?))

#png#pngs#transparent#transparents#moodboard#artboard#imageboard#collage#digital collage#mixed media#sticker#stickers#fossils#slime mold#217

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

🦖 Description des mollusques fossiles qui se trouvent dans les grès verts des environs de Genève /. Genève: impr. de Jules-Guillaume Fick, 1847-1853.. Original source Image description: Illustration plate showing detailed black-and-white drawings of 30 fossilized Cretaceous mollusk shells from the genus Solarium. The shells vary in shape, including tightly coiled spirals, conical forms, and partial cross-sections, revealing intricate surface textures such as ridges, grooves, and dotted patterns. The specimens are labeled numerically and alphabetically (e.g., 1a, 4c), with sections displaying broken or cut views to expose internal shell structures. The image is from a 19th-century scientific publication documenting mollusks found in green sandstones near Geneva. The detailed depictions aid in the identification and comparison of extinct species from this geological period.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

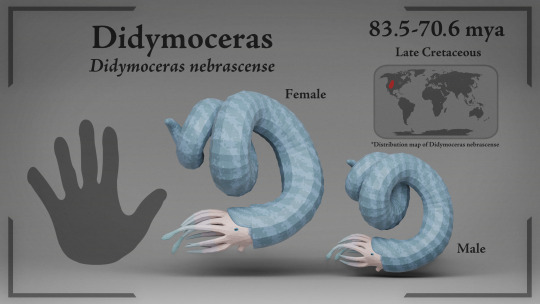

Didymoceras nebrascense - an unusual ammonite from the Late Cretaceous, ~70 million years ago, found in the seas of North America. It was one of heteromorph ammonites, known for their odd shells that formed a variety of strange and complex shapes. The spiral shell of Didymoceras, like other heteromorphs, impacted its locomotion, causing it to drift slowly with ocean currents. During that it likely used its tentacles to catch small prey, while the unusual shell shape might have helped against predators.

Fossil evidence suggests sexual dimorphism, with females larger than males. This size difference was likely linked to reproductive roles, as females needed more space to store eggs and additional protection, a trait common in other ammonites.

224 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lytoceras adeloides Ammonite Fossil – Pliensbachian Jurassic Italy, Rare Authentic Specimen

A beautiful and rare example of Lytoceras adeloides, a distinctive ammonite fossil from the Pliensbachian Stage of the Lower Jurassic, approximately 190–192 million years ago. This specimen was collected from classic Jurassic deposits in Italy, a region known for its high-quality marine fossils.

Lytoceras ammonites are recognised for their smooth, involute coiling and finely ribbed or even nearly smooth shells, with wide umbilici and complex suture lines. L. adeloides is a rare and elegant representative of this genus and is especially sought after by collectors for its aesthetic structure and scientific interest.

Fossil Type: Ammonite (extinct marine cephalopod)

Species: Lytoceras adeloides

Geological Age: Lower Jurassic – Pliensbachian Stage

Formation: Likely part of Pliensbachian marine limestone or marl deposits of northern or central Italy

Depositional Environment: These ammonites lived in open marine environments, often deeper shelf settings, where sediments accumulated slowly. Preservation is generally excellent due to fine sediment and low disturbance.

Morphological Features:

Smooth, evolute shell with faint or absent ribbing

Wide umbilicus

Complex suture lines characteristic of Lytoceras

Coiling generally open and symmetrical

Notable:

Rare species from the Lytoceratidae family

Elegant appearance, ideal for fossil displays or academic collections

Sourced from Jurassic fossil beds of Italy

The specimen shown is the exact one you will receive

Authenticity: All of our fossils are 100% genuine natural specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity. Please refer to the included scale cube or ruler (1cm per square) for exact sizing.

This rare Lytoceras adeloides ammonite from the Pliensbachian of Italy is a fine example of early Jurassic cephalopods—elegant, scientifically relevant, and ideal for collectors seeking something special.

#Lytoceras adeloides#Jurassic ammonite fossil#Pliensbachian ammonite#Italian fossil ammonite#fossil cephalopod#Lytoceratidae fossil#spiral ammonite fossil#fossil shell Italy#Jurassic marine fossil#rare ammonite#authentic fossil specimen#collector ammonite

0 notes

Text

Ammonoid from Morocco

#145$#ammonite#ammonoid#fossil#fossils#spiral#png#transparent#Etsy#paleontology#prehistoric#ocean fossil#fossil shell#ammonite shell#fav

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sedimental Value

Megatron vs. Paleontology

I just wanted to yap about fossils lmao and pun.

Part 1/4 Link

---

The battle had been fierce—briefly.

Optimus and Megatron had traded blows across the rocky slopes, scattering wildlife and triggering small landslides somewhere in the Appalachian Mountains.

“For once,” Megatron growled, “stay down, Prime!”

Optimus Prime landed with a heavy thud, shaking pine needles loose from the trees. Megatron followed, crashing through the canopy, fusion cannon flaring.

“This ends now, Prime!” Megatron snarled, charging with wild force.

Optimus sidestepped just in time.

CRUNCH .

Megatron pitched forward with a mechanical yelp as his foot caught something buried in the dirt. He tripped in glorious, undignified fashion and landed face-first into a rocky embankment.

CRACK. “GRAAAUGH!”

One clumsy misstep, one badly-placed foot, and the Warlord of Kaon was suddenly flailing—arms windmilling—before crashing into the side of a shale outcrop.

A boulder split in half.

Megatron lay there for a moment in stunned silence, then shoved himself upright with a snarl. “What in the pit—?!”

He looked down, half-expecting a landmine or a hidden Autobot trap.

Instead, he saw... a rock.

Optimus skidded to a halt, mid-leap. “...Are you alright?”

Megatron roared and shoved himself up. “WHO PUT THIS RIDICULOUS... LUMP OF ROCK IN MY PATH?!”

Optimus stepped over calmly, peering at the object Megatron had tripped on. Embedded in the earth was a large, spiral-shaped fossil.

The Prime paused mid-charge, optics flicking from Megatron to the object. Then his expression changed.

“Oh—oh, no way.” He stepped forward quickly, crouching beside the half-buried stone. “Is that a fossil?”

Megatron blinked. “A what?”

Optimus’s entire demeanor shifted, tension evaporating like mist in sunlight. “It’s a Brachiopod. Look at this—still partially embedded, but you can make out the hinge and the ridges across the shell. Perfect symmetry.” He brushed away some soil with careful fingers. “And the preservation? It’s Devonian. Has to be. This entire region used to be seabed over 400 million Earth years ago.”

Megatron blinked. “Prime. We are in the middle of a battle.”

Optimus continued excitedly monologuing.

Megatron just stared.

Optimus was... smiling.

His voice had gone light and enthusiastic, the way it never did during war. There was something unguarded in him—something Megatron hadn’t seen in millennia.

“You're monologuing about sea bugs,” Megatron said flatly.

But Optimus wasn’t listening anymore.

“This one likely lived anchored to the ocean floor, filtering particles from the water. And here it is—untouched for eons, until you stepped on it.” He chuckled softly. “Poor thing.”

Megatron grumbled and leaned on a nearby tree, rubbing his helm. “This was supposed to be a combat operation.”

Optimus didn’t even glance up. “Do you remember when I used to do this full-time? Study, document, preserve? I spent megacycles in the Hall of Records, cataloging ancient systems, reading about long-dead civilizations. Back then, nothing was more important to me than understanding the past.”

Megatron didn’t answer. Not right away.

But he did remember.

He remembered a younger Optimus—Orion Pax then—hovering over datacores and relics with the same reverence he now gave the little fossil. Megatron had walked those archives once, long before revolution burned away what they’d been. He’d argued with Orion about injustice and philosophy in the low-lit vaults beneath Iacon. They’d fought then too—verbally, eloquently. Earnestly.

“You were different then,” Megatron muttered, his voice low.

Optimus finally looked up.

“You talked about knowledge like it was sacred,” Megatron continued. “You wanted to build something with it. Something with me. Not—" he gestured vaguely at the broken trees and scorched earth, “—this.”

Optimus’s gaze softened. “I never stopped wanting that, Megatron.”

“I know.” He looked away. “That was the tragedy, wasn’t it?”

For a long moment, neither of them moved. The wind whispered through the trees, stirring branches and memories alike.

Optimus turned back to the fossil. “Do you ever miss it?”

“What?”

“The people we were before war turned us into this.”

“…Sometimes,” Megatron admitted. “But then I remember who I was forced to become.”

Silence again. Not tense—just... quiet.

Optimus stood and gently set the fossil back in the dirt, carefully packing soil around it.

“You’re preserving it?” Megatron asked incredulously.

“Of course. Some things are worth protecting.”

Megatron huffed. “You’ll never change.”

“Maybe not,” Optimus said. “But I still remember how to value something ancient and fragile.”

Megatron stared at him. “You’re talking about the rock, aren’t you?”

Optimus smiled faintly. “Mostly.”

Megatron shook his head, a reluctant smirk twitching at the corner of his mouth.

“You’re lucky I tripped on that thing,” he said. “Any longer and I might’ve hit you hard enough to shut you up.”

“You could try,” Optimus replied, tone amused. “But I’d probably start quoting paleontology terms while half delirious anyway.”

Megatron groaned. “I hate that I missed this part of you.”

Optimus tilted his head. “You didn’t miss it. It was always there. You just stopped listening.”

Megatron shook his head, rising. “I’m leaving before you start talking about trilobites.”

“I do love trilobites,” Optimus called after him as Megatron transformed and blasted off.

“You’re unbearable,” he called as he lifted off. “Tell your fossil goodbye for me.”

“I will,” Optimus said softly, watching him disappear into the sky.

He turned back to the ridge, brushing his hand once more over the ancient shell, then sat down beside it.

And for a while, he simply watched the wind move through the trees.

#ao3#fanfic#The inner archivist is a history buff#optimus prime#optimus x megatron#transformers optimus#Optimus prime#optimus#opmeg#megop#transformers#transformers fanfiction#megatron x optimus prime#megatron#tf megatron#transformers megatron#transformers megop#transformers opmeg

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fossils you’re seeing are from the Jimbacrinus crinoid, found in Western Australia (Gascoyne Junction), and they’re believed to be approximately 280 million years old.

These marine creatures, also known as sea lilies, lived during the Permian period. The fossils are usually found complete and have not been uncovered in any other location. They were first discovered in 1949 by the manager of Jimba Jimba cattle station, for which the genus was named.

The Permian period was the final period of the Paleozoic Era, lasting from 298.9 million to 252.2 million years ago. The climate was warming throughout Permian times, and, by the end of the period, hot and dry conditions were so extensive that they caused a crisis in Permian marine and terrestrial life.

The Permian seas were dominated by bony fishes with fan-shaped fins and thick, heavy scales. There were large reef communities that harbored squidlike nautiloids. Ammonoids, with their tightly coiled, spiral shells, are also widespread in the Permian fossil record.

Gascoyne Junction is a remote area in Western Australia known for its geological diversity. Geologists have determined that magmatic fluids came up from the earth’s mantle repeatedly over the past 1600 million years, depositing minerals along a fault line in the Gascoyne region. This area is also known for its remarkable fossil finds, including the Jimbacrinus crinoid fossils. This specimen is part of the collection at Crystal World, under the ownership of Tom Kapitany.

351 notes

·

View notes

Text

Наутилус (лат. Nautilus) — род головоногих моллюсков, которых относят к «живым ископаемым». Самый распространенный вид — Nautilus pompilius. Наутилусы относятся к единственному современному роду подкласса наутилоидей. Первые представители наутилоидей появились в кембрии, а его развитие пришлось на палеозой. Наутилиды почти вымерли на границе триаса и юры, но все же дожили до наших дней, в отличие от своих родственников аммонитов. Некоторые виды древних наутилусов достигали размера в 3,5 м. Представители самого крупного вида современных наутилусов достигают максимального размера в 25 см.

Спиральный «домик» моллюска состоит из 38 камер и «построен» по сложному математическому принципу (закон логарифмической прогрессии). Все камеры, кроме последней и самой большой, где размещается тело наутилуса с девятью десятками «ног», соединяются через отверстия между собой сифоном. Раковина наутилуса двухслойная: верхний (наружный) слой – фарфоровидный – действительно напоминает хрупкий фарфор, а внутренний, с перламутровым блеском – перламутровый. «Домик» наутилуса растет вместе с хозяином, который перемещается по мере роста раковины в камеру попросторней. Пустое жилище моллюска после его гибели можно встретить далеко от его места обитания – после гибели «хозяина» их раковины остаются на плаву и перемещаются по воле волн, ветров и течений.

Интересно, что двигается наутилус «в слепую», задом наперед, не видя и не представляя препятствий, которые могут оказаться на его пути.И еще одно удивительное качество этих древних обитателей Земли – у них потрясающая регенерация: буквально через несколько часов раны на их телах затягиваются, а в случае потери щупальца быстро отрастает новое.

Nautilus is a genus of cephalopods, which are classified as "living fossils". The most common species is Nautilus pompilius. Nautilus belong to the only modern genus of the Nautiloid subclass. The first representatives of the Nautiloids appeared in the Cambrian, and its development took place during the Paleozoic. The Nautilids almost died out on the border of the Triassic and Jurassic, but still survived to the present day, unlike their Ammonite relatives. Some species of ancient Nautilus reached a size of 3.5 m. Representatives of the largest species of modern nautilus reach a maximum size of 25 cm.

The spiral "house" of the mollusk consists of 38 chambers and is "built" according to a complex mathematical principle (the law of logarithmic progression). All chambers, except the last and largest, where the nautilus body with nine dozen "legs" is located, are connected through holes with a siphon. The nautilus shell is two–layered: the upper (outer) layer – porcelain–like - really resembles fragile porcelain, and the inner, with a mother-of-pearl luster - mother-of-pearl. The nautilus's "house" grows with its owner, who moves as the shell grows into a larger chamber. The empty dwelling of a mollusk after its death can be found far from its habitat – after the death of the "owner", their shells remain afloat and move at the will of waves, winds and currents.

Interestingly, the Nautilus moves "blindly", backwards, without seeing or imagining the obstacles that may be in its path.And another amazing quality of these ancient inhabitants of the Earth is that they have amazing regeneration: in just a few hours, the wounds on their bodies heal, and in case of loss of tentacles, a new one grows quickly.

Источник:://t.me/+t0G9OYaBjn9kNTBi, /sevaquarium.ru/nautilus/, /habr.com/ru/articles/369547/, //wallpapers.com/nautilus, poknok.art/6613-nautilus-molljusk.html, //wildfauna.ru/nautilus-pompilius, /www.artfile.ru/i.php?i=536090.

#fauna#video#animal video#marine life#marine biology#nature#aquatic animals#cephalopods#Nautilus#nautilus pompilius#living fossils#ocean#benthic#coral#plankton#beautiful#animal photography#nature aesthetic#видео#фауна#природнаякрасота#природа#океан#бентосные#головоногие моллюски#Наутилус#живое ископаемое#коралл#планктон

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you asked me as a kid what my favorite animal was, there's a good chance I'd respond "chambered nautilus", though I probably would mispronounce it. I don't know if it's still my favorite but it's definitely up there in the pantheon of weird critters. For this Wet Beast Wednesday, I'll discuss my childhood favorite.

(image: a nautilus)

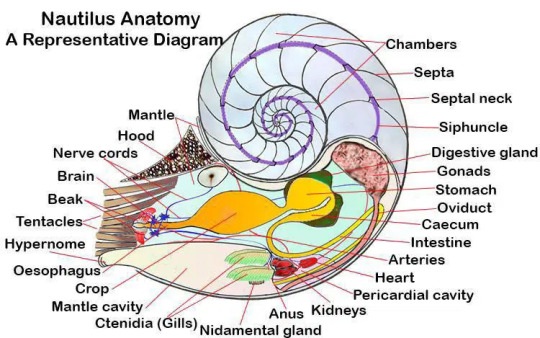

The nautilus is a cephalopod that lives in a curved shell and looks similar to (but is not closely related to) the extinct ammonites. There are 6 living species in two genera, but 90% of the time when someone is discussing nautiluses they are referring to the most well-known species: Nautilus pompilius or the chambered nautilus. Nautiloids are ancient, going back to at least the late triassic with their more primitive ancestors going back as far as the ordovician period, a time when only invertebrates and primitive plants occupied the land and true fish had not yet appeared. Because of their ancient history, nautiluses are sometimes considered living fossils. I have ranted before on how misleading the term "living fossil" is so I'll spare you that for now. Nautiloids are considered a sister group to the celoids, which contains all the squid, octopus, cuttlefish, and everything else we thinks of as cephalopods. Nautiluses should not be confused with paper nautiluses. Also called argonauts, paper nautiluses are a group of octopi that make an egg case which looks like a shell.

(image: a nautilus)

The most noticeable feature of a nautilus is its shell. The shell is smooth and finely curving, naturally growing in the shape of a logarithmic spiral (though not, as is commonly stated, a golden ratio spiral). The shell has a stripy outer layer and an inner layer coated with nacre. Internally, the shell is divided into camarae (chambers) separated from each other by walls called septa. Each septum has a small hole in it through which a strand of tissue called the siphuncle passes. Most of the nautilus's body is in the foremost and largest chamber. The shell grows new septa as the animal grows, with the nautilus's body moving to a new chamber as it becomes too large for previous ones. Juveniles are typically born with 4 septa, with adults having as many as 30. In addition to providing protection from predators, the shell is also key for regulating buoyancy. The septa can contain pressurized gas or water and the siphuncle regulates their contents by either adding or removing water to increase or decrease buoyancy. Because of its pressurized contents, the shell can only withstand pressure at depths up to 800 M (2,400 ft) before imploding. Oddly enough, nautiluses can be safely brought up from deep waters where most animals would be killed by the pressure changes. To move, the nautilus pulls water into the first chamber of the shell using its hyponome (siphon) and shoots it back out. The chambered nautilus is the largest species, with a maximum shell diameter of 25 cm (10 in), though most get no larger than 20 cm (8 in).

(image: a diagram of nautilus anatomy. source)

Where celoid cephalopods have tentacles, nautiluses instead have numerous cirri. Unlike tentacles, cirri are less muscular, are not elastic, and have no suckers. They are used to grab objects using their ridged surfaces and can hold in so hard that trying to take an object away from a nautilus can rip off its cirri, which will remain firmly attached. In addition, the nautilus has modified cirri that serve as olfactory receptors and a pair that serve to open and close the shell when the nautilus needs to retract into it or emerge. Nestled within the cirri is the beak, which is used to consume the nautilus's primary prey of invertebrates, though they have also been seen scavenging fish. Their eyes are less developed than most cephalopods, lacking a lens and consisting of a small pinhole that only allows the nautilus to see simple imagery. Their brains are differently structured than most cephalopods and studies have found them to have considerably shorter long-term memories.

(image: a chambered nautilus (upper left) next to a rare Allonautilus scrobiculatus. source)

Cephalopod reproduction is quite different than that of other cephalopods. While most cephalopods are short-lived and semelparous (reproducing only once), nautiluses can live over 20 years and reproduce multiple times (iteroparity). They do not reach sexual maturity until around 15 years old, with females laying eggs once per year. Eggs are attached to rocks and take 8 to 12 months to hatch. Males have a structure called the spadix composed of 4 fused cirri that they use to transfer sperm to females. Females lose their gonads after laying their eggs and will regenerate them for the next year's mating season. Interestingly, male nautiluses seem to vastly outnumber the females. EDIT: @bri-the-nautilus in the replies found an alternate explanation for the disparity in male and female numbers you should check out. TLDR; the females are asocial.

(image: nautiluses mating)

Nautiluses are found in the Indo-Pacific reagion of the ocean and can be found on the steep slopes of coral reefs. They prefer to inhabit waters several hundred meters down. It was once believed that they would rise to shallow waters at night to feed, lay eggs, and mate, but their vertical migration behavior has since been shown to be more complex than that. They have noon been fished by humans for their shells, which have become popular subjects in art and can be made into a number of decorative pieces. The nacre of the shell can be polished into osmeña pearl, which can be quite valuable. Demand for the shells combined with the late sexual maturity and low fecundity is threatening all the species. As of 2016, nautiluses have been added to the CITES Appendix II, making them protected by limiting international trade of their shells. Despite this, they are still threatened and require further protection

(image: a carved and painted nautilus shell from the Poldi Pezzoli Museum, Milan)

#wet beast wednesday#nautilus#chambered nautilus#cephalopod#marine biology#zoology#biology#ecology#animal facts

1K notes

·

View notes