#how to be an antiracist

Text

"Keep your city clean, destroy fascism" (EN: English)

#Keep your city clean#destroy fascism#161#1312#antifa#antifascist#antifaschistische aktion#antinazi#anti capitalism#antiauthoritarian#antiwork#anti slavery#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#antiracism#how to be an antiracist#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#antifascismo#antifaschismus#anarchism#anarchist

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I am not my ancestors!!!"

*Doesn't call out their friends racism, believes in stereotypes, denies their white privilege, uses the police as a way to keep black people in line, steals from black creators then tries to rebrand it as something new, gets mad a black safe spaces, uses their white tears as a way to get black people in trouble, whitewashes the truth,and is somehow always the victim in any situation at all time.*

Just cuz you don't have a whip in your hand and aren't telling black people to get back into the fields doesn't mean you're any different from your meemaw in the 50s or your pop pop in the 1700s bitch 🤷🏾♂️

#rants n rambles#antiblackness#antiracism#how to be an antiracist#anti blackness#lgbtq community#lgbtq#racism#race issues#racial bias#racial justice#racial profiling

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The most threatening racist movement is not the alt right’s unlikely drive for a White ethnostate but the regular American’s drive for a “race-neutral” one.”

-- Ibram X. Kendi, “How to Be an Antiracist”

Not being racist is more racist than being racist. 🤡

#Ibram X. Kendi#kendi is a racist#How to Be an Antiracist#smooth brain#woke doctrine#neoracism#antiracism as religion#antiracism#wokeness as religion#cult of woke#woke#wokeism#woke activism#race neutral#colorblind#colorblindness#religion is a mental illness

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

NPR: In new documentary, Ibram X. Kendi asks 'What is wrong with Black people?'

In new documentary, Ibram X. Kendi asks 'What is wrong with Black people?'

Eric Deggans looks at the new documentary "Stamped from the Beginning," which looks at the history of racist ideas in America.

AYESHA RASCOE, HOST:

The Netflix documentary "Stamped From The Beginning" starts with a provocative question writer and professor Ibram X. Kendi asks of other Black academics.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOCUMENTARY, "STAMPED FROM THE BEGINNING")

IBRAM X KENDI: Can you please tell me what is wrong with Black people?

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #1: What is wrong with Black people?

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #2: OK, what do you mean by that?

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON #3: What is wrong with Black people?

RASCOE: Kendi, who founded the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University, answers by invoking how systemic racism can convince Black people and everyone else that Black people deserve to be marginalized. NPR TV critic and media analyst Eric Deggans has watched "Stamped From The Beginning" and has also been following recent allegations of mismanagement against Kendi at the BU center. Hi, Eric.

ERIC DEGGANS, BYLINE: Hi.

RASCOE: So first, tell us more about this documentary. It's out on Netflix later this month.

DEGGANS: Yeah, it's this percolating primer on the themes in Kendi's award-winning 2016 book of the same name. Now, there's compelling animation, historical photos, interviews with lots of academics - although it might be tough for some people to watch. It's centered on this idea that much of the systemic racism that's directed against Black people was created as an attempt to justify enslavement and exploitation of Black people, not the other way around. And in the film, you know, Kendi speaks of this ruler known as Prince Henry of Portugal who he says turned to enslaving Black people from Africa in the mid-1400s instead of Europeans because it was harder for them to run away. Here's a clip. Let's listen.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOCUMENTARY, "STAMPED FROM THE BEGINNING")

KENDI: Prince Henry didn't want to admit he was violently enslaving African people to make money, so he dispatched a royal chronicler by the name of Gomes Zurara.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

KENDI: Gomes Zurara justified his slave trading by stating that Prince Henry was doing it to save souls and that these people in Africa were inferior.

DEGGANS: So that, Kendi says, is the creation of Blackness in which Europeans treat Africans from many different tribes and countries as one inferior race to justify exploiting them.

RASCOE: So these are some very complex concepts about race and history. How does this fit with his other work, you know, like his bestselling book "How To Be An Antiracist" or his ESPN series on sports and race?

DEGGANS: Well, you know, I've interviewed Kendi for NPR's Life Kit podcast. And at the core of a lot of his work is this idea that racism is a behavior, not just a state of being - that it comes down to choices you make every day. And in Netflix's "Stamped From The Beginning," that means examining these ideas like the myth of Black hypersexuality, which has been invoked throughout history to justify raping Black women or lynching Black men. And after the death of George Floyd in 2020, you know, Kendi gained new prominence speaking on these themes - the themes in "How To Be An Antiracist." And those ideas are found in so many contemporary issues that it makes sense that Kendi could leverage them into an ESPN project on racism in sports or this Netflix film.

RASCOE: And what about that criticism Kendi ran into following his decision earlier this year to lay off about half the staff at the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University? Where do those allegations of mismanagement stand?

DEGGANS: Well, the university just released an internal audit finding there were no issues with how the center's finances were handled, which kind of backed up Kendi's contention that the layoffs were not a result of bad fiscal management. And it also pushes back against some critics who tried to delegitimize his concepts by suggesting he's some kind of fraud. Now, hopefully, this will allow people to focus more on his ideas, which he sums up at the end of "Stamped From The Beginning" by answering that original question. The only thing wrong with Black people, he says, is that we think something is wrong with Black people.

RASCOE: NPR TV critic and media analyst Eric Deggans. Thank you so much.

DEGGANS: Thank you.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i just realised that all THREE (3) books im currently reading are about racism

#the books are:#how to be an antiracist#superman: dawnbreaker#what does justice look like: the struggle for liberation in dakota homeland#life of con#conpost

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

r/Europe has gone full Nazi and when you say something against this shit you're downvoted into oblivion. We are talking about thousands of people living on the continent genuinely thinking of refugees as "economic migrant" who take to the sea as if the Nazi do for a holiday. And you can't fuckin educate them and it drives me insane.

Yesterday I spent an hour chatting with a friend and colleague, so eloquent and insanely well educated. He's a refugee in the UK. I asked him about the asylum process and he was extremely candid and again, so acutely aware of the system and with the language to break it down. Dog whistles like "economic migrant" are just Nazi Europe trying to forget the fact that if they left countries on their knees that people cannot feed themselves and so they have every right to survival including migrating to a country where food is no question.

Between colonialism and resources extraction from the third world Europe should fucking bow their head and pay reparations to every country they destroyed instead these white fuckers who have not worked for the luck hey have of being white of being born on the right side of an imaginary line talk about refugees as liars, as calculated manipulators who supposedly want more than even white people have. I'm not surprised the media came up with this stories but that adult people just eat it up?

And then I'm reminded, people with privilege just care about keeping their birth lottery ticket valid.

And then maybe we deserve to go extinct

#racism#antiracism#how to be an antiracist#europe#social justice#intersectional social justice#intersectionalfeminist#intersectionality#refugees welcome#united nations#economic migrants#privilege#white privilege#first world problems

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book 37: How to be an Antiracist

This week I chose How to be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi. It was a tough book. There is just a ton of historical racist ideas and rhetoric presented as what we're fighting against and it made for very uncomfortable reading. My library's copy was an updated book that had annotations that fixed problematic terms and clarified points he had been criticized about.

Kendi's premise is that one cannot simply be a "not racist" person and the opposite of racism is antiracism. There are two kinds of racism - one that thinks some races are inferior and always will be and one that says some races are inferior, but not inherently because if they assimilate to the right (white) ideas they can become equals. He talks about the connection and intertwining of Capitalism and racism and the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality. Apparently modern Capitalism was born when Prince Henry the "Navigator" started Black slavery. Racism isn't necessarily about bad people hating other people for the color of their skin- it's more about self interest and using the concept that others are inferior to justify unfair policies.

Kendi is absolutely frank about his own history of internalized racist ideas and college era bigotry against white people. At one point he even believed whites were aliens that came to oppress Earthlings of color (his friend laughed him out of the room at that one and he soon dropped the idea).

Essentially to be an antiracist is to support policies that seek to eliminate racial injustice.

BEST QUOTE: We cannot be antiracist if we are homophobic or transphobic.

SHOULD YOU READ THIS BOOK? I give this one a resounding yes! It's an interesting premise and a great look into America's and the World's racism problem.

ART PROJECT:

Ok, I really couldn't think of anything to do for this that wasn't totally cheesy.

So I thought in the spirit of the self confession in the book that I would share my history of being racist. I started a few spaces ahead as my parents are antiracist oriented (nobody's perfect though), and and raised me as best they could in a racist society. I still held a lot of racist ideas and ignorance honestly. And though I was raised to be a gay ally, back when I was a kid I was pretty transphobic and would be until the trans movement gained better traction in the 2000s and I finally learned that trans men and women are in fact men and women. Unfortunately for me, I was in a very white area and the only substantial population of people of color were Latinix. That thankfully made most of my racist mistakes not targeted at actual individuals. I still struggle with racist ideas though I try very hard to be antiracist. All I can do is continue to chip away at my ignorance and be eternally vigilant.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

If the children do not stop using the language of social justice to reinforce the same tired segregationist boundaries I swEAR TO MYSELF

“Maybe I shouldn’t hang out with the working-class kids because I am upper-middle class and my privilege might be a problem” is the second most cop thing I have read today

#persephone#punk#punk rock#greek goddess#antiauthoritarian#antiracisteducation#how to be an antiracist#anticlassist

3 notes

·

View notes

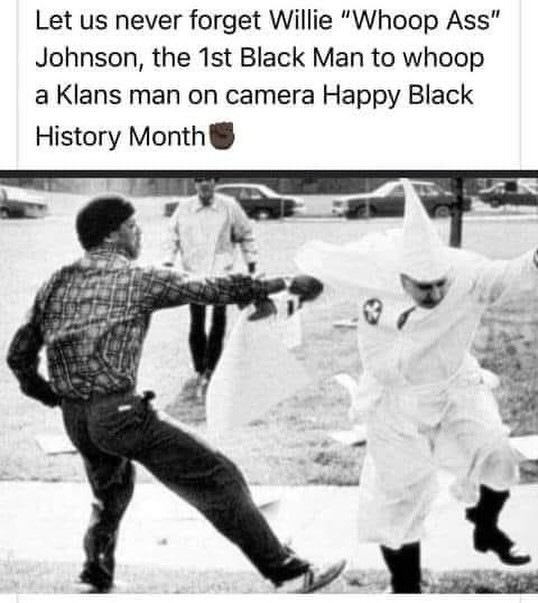

Text

#black history#black history month#161#1312#antifa#antifascist#antifaschistische aktion#antinazi#antiauthoritarian#antiracism#how to be an antiracist#class war#goodnightwhitepride#anti imperialism#anti colonialism#ku klux klan#kkk#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#nazisploitation#sacha baron cohen accuses tiktok of ‘biggest antisemitism movement since the nazis’#nazis

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gals! Gals, gals, gals, gals!

WHAT IF THE NEXT ANIMATED DISNEY MOVIE WAS HUCK FINN?

#disney#huckleberry finn#disney princess#gimme a PRINCE film#atlantis#grab JTT outta retirement#give FL the Fucking Loser treatment#funny shit#classic#how to be an antiracist#corporate warfare#Government wants propoganda?#make the banned books movies 🎬

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Coleman Hughes

Published: Oct 27, 2019

In 2016, Ibram X. Kendi became the youngest person ever to win the National Book Award for Nonfiction. His surprise bestseller, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas, cast him in his role as an activist-historian, ambitiously attempting to make 600 years of racial history digestible in 500 pages. In his follow-up, How to Be an Antiracist, Kendi––now 37, a Guggenheim fellow, and a contributing writer at The Atlantic––reveals his personal side, weaving together memoir, polemic, and instruction as he invites the reader to join him on the frontlines of what I like to call the War on Racism.

If the book has a core thesis, it is that this war admits of no neutral parties and no ceasefires. For Kendi, “there is no such thing as a not-racist idea,” only “racist ideas and antiracist ideas.” His Manichaean outlook extends to policy. “Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity,” Kendi proclaims, defining the former as racist policies and the latter as antiracist ones.

Every policy? That question was posed to Kendi by Vox cofounder Ezra Klein, who gave the hypothetical example of a capital-gains tax cut. Most of us think of the capital-gains tax, if we think about it at all, as a policy that is neutral as regards questions of race or racism. But given that blacks are underrepresented among stockowners, Klein asked, would it be racist to support a capital-gains tax cut? “Yes,” Kendi answered, without hesitation. And in case you planned on escaping the charge of racism by remaining agnostic on the capital-gains tax, that won’t work either, because Kendi defines a racist as anyone who supports “a racist policy through their actions or inaction.”

Hailed by the New York Times as “the most courageous book to date on the problem of race in the Western mind,” How to Be an Antiracist is certainly bold in its effort to redefine a concept that bedevils American society. On his unusually expansive definition, Kendi sees racism operating not just behind niche issues like the capital-gains tax but also behind problems of civilizational significance. “Racism,” he writes, “has spread to nearly every part of the body politic,” “heightening exploitation,” causing “arms races,” and “threatening the life of human society with nuclear war and climate change.” How, exactly, racism is behind the threat of nuclear holocaust is left to the reader’s imagination.

At times, it’s hard to know whether to interpret Kendi’s arguments as factual claims subject to empirical scrutiny or as diary entries to be accepted as personal truths. Indeed, much of the book reads like a seeker’s memoir or a conversion story in the mold of Augustine’s Confessions. Raised in a rough part of Queens in the 1990s, Kendi recounts his long journey from anti-black racism to anti-white racism, and eventually, to antiracism. In high school, Kendi delivered a speech bemoaning the bad behavior of black youth; by college, he had outgrown that phase and become anti-white, convinced at one point that white people were literal aliens but later scaling down to the belief that they were “simply a different breed of human.” A New Yorker piece cites a column he wrote as an undergraduate, in which he argued that “white people were fending off racial extinction, using ‘psychological brainwashing’ and ‘the aids virus.’”

Having matured out of his anti-white phase, Kendi takes a refreshingly strong stand against anti-white racism in the book, rejecting the fashionable argument that blacks cannot be racist because they lack power. He reflects with embarrassment on his old beliefs, avoiding condescension by lecturing his former self instead of the reader. Still, certain autobiographical details call for embarrassment but don’t get it. He recalls, for example, his first night living in Virginia as a teenager, during which he stayed up all night, “worried the Ku Klux Klan would arrive any minute.” That took place in 1997.

The book is weakest in its chapter devoted to capitalism. “Capitalism is essentially racist,” Kendi proclaims, and “racism is essentially capitalist.” To test this claim, a careful thinker might compare racism in capitalist countries with racism in socialist/Communist ones; or he might compare racism in the private sector with racism in the public sector. Kendi does neither. Instead, he presents the link between capitalism and racism as self-evidently true: “Since the dawn of racial capitalism, when were markets level playing fields? . . . . When could Black people compete equally with White people?” Kendi asks, implying that the answer is “never.”

I can think of several historical examples in which capitalism inspired anti-racism. The most famous is the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court case, when a profit-hungry railroad company––upset that legally mandated segregation meant adding costly train cars––teamed up with a civil rights group to challenge racial segregation. Nor was that case unique. Privately owned bus and trolley companies in the Jim Crow South “frequently resisted segregation” because “separate cars and sections” were “too expensive,” according to one scholarly paper on the subject.

A lesser known example is the South African housing market under Apartheid. Though landlords in whites-only areas were legally barred from renting to nonwhites, vacancies made discrimination against non-white tenants costly. As a result, white landlords often ignored the law. In his book South Africa’s War on Capitalism, economist Walter Williams notes that at least one “whites-only” district was in fact comprised of a majority of nonwhites.

History offers little evidence that capitalism is either inherently racist or antiracist. As a result, Kendi must resort to cherry-picking data to demonstrate a link. Citing a Pew article, he asserts that the “Black unemployment rate has been at least twice as high as the White unemployment rate for the last fifty years” because of the “conjoined twins” of racism and capitalism. But why limit the analysis to the past 50 years? A paper cited in the same Pew article reveals that the black-white unemployment gap was “small or nonexistent before 1940,” when America was arguably more capitalist—and certainly more racist.

Kendi also cherry-picks his data when discussing race and health. He laments that blacks are more likely than whites to have Alzheimer’s disease, but neglects to mention that whites are more likely to die from it, according to the latest mortality data from the Center for Disease Control. In the same vein, he correctly notes that blacks are more likely than whites to die of prostate cancer and breast cancer, but does not include the fact that blacks are less likely than whites to die of esophageal cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, ovarian cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and leukemia. Of course, it should not be a competition over which race is more likely to die of which disease––but that’s precisely my point. By selectively citing data that show blacks suffering more than whites, Kendi turns what should be a unifying, race-neutral battle ground––namely, humanity’s fight against deadly diseases––into another proxy battle in the War on Racism.

Worse than the skewed approach to data in Kendi’s book are the factual errors. Citing an entire book by Manning Marable (but no specific page), Kendi claims that in 1982, “[President Reagan] cut the safety net of federal welfare programs and Medicaid, sending more low-income Blacks into poverty.” I could not find any data in Marable’s book showing that the black poverty rate rose during Reagan’s tenure. In fact, the opposite appears to be true, according to the Census Bureau’s historical poverty tables: the black poverty rate decreased for every age group between 1982 and the end of Reagan’s tenure in 1989.

Also erroneous is Kendi’s claim, for which he offers no citation, that “White women” are the “primary beneficiaries” of “affirmative-action programs.” Judging from a similar claim made in Vox, this myth seems to come from a paper published by the critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 2006. Crenshaw’s paper, troublingly, contains no data and no empirical analysis. However, a group of political scientists did conduct an empirical study on the relationship between white women and affirmative action in the same year. They found that employers who supported affirmative action were no more likely to employ white women than employers who didn’t. The primary beneficiaries of affirmative action—at least in university admissions—are, in fact, the black and Latino children of middle- and upper-middle-class families.

What Kendi lacks in empirical rigor he makes up for in candor. Whereas many antiracists dance awkwardly around the fact that affirmative action is a racially discriminatory policy, Kendi says what they probably believe but are too afraid to say: namely, that “racial discrimination is not inherently racist.” He continues:

The defining question is whether the discrimination is creating equity or inequity. If discrimination is creating equity, then it is antiracist. If discrimination is creating inequity, then it is racist. . . . The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.

Insofar as Kendi’s book speaks for modern antiracism, then it should be praised for clarifying what the “anti” really means. Fundamentally, the modern antiracist movement is not against discrimination. It is against inequity, which in many cases makes it pro-discrimination.

The problem with racial equity––defined as numerically equal outcomes between races––is that it’s unachievable. Without doubt, we have a long way to go in terms of maximizing opportunity for America’s most disadvantaged citizens. Many public schools are subpar, and some are atrocious; a sizable minority of black children grow up in neighborhoods replete with crime and abandoned buildings, while a majority grow up in single-parent homes. Too many blacks are behind bars.

All this is true, yet none of it implies that equal outcomes are possible. Kendi discusses inequity between ethnic groups––which he views as identical to inequity between racial groups—as problems created by racist policy. This view commits him to some bizarre conclusions. For example, according to 2017 Census Bureau data, the average Haitian-American earned 68 cents for every dollar earned by the average Nigerian-American. The average French-American earned 70 cents for every dollar earned by the average Russian-American. Similar examples abound. Is it more likely that our society imposes policies that discriminate against American descendants of Haiti and France, but not Nigeria and Russia—or that disparities between racial and ethnic groups are normal, even in the absence of racist policies? Kendi’s view puts him firmly in the former camp. “To be antiracist,” he claims, “is to view the inequities between all racialized ethnic groups”––by which he means groups like Haitian-Americans and Nigerian-Americans––“as a problem of policy.” Put bluntly, this assumption is indefensible.

What would it take to achieve a world of racial equity? Top-down enforcement of racial quotas? A constitutional amendment banning racial disparity? A Department of Antiracism to prescreen every policy for racially disparate impact? These ideas may sound like they were conjured up to caricature antiracists as Orwellian supervillains, but Kendi has actually suggested them as policy recommendations. His proposal is worth quoting in full:

To fix the original sin of racism, Americans should pass an anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution that enshrines two guiding anti-racist principles: Racial inequity is evidence of racist policy and the different racial groups are equals. The amendment would make unconstitutional racial inequity over a certain threshold, as well as racist ideas by public officials (with “racist ideas” and “public official” clearly defined).

Kendi’s suggestion that “racist ideas” would or could be rigorously defined is cold comfort, given his capacious definition of racism. In his book, Kendi calls belief in an achievement gap between black and white students a “racist idea.” Does that mean that President Obama would have violated Kendi’s antiracist amendment when he talked about the achievement gap in 2016? Would we have to overturn the First Amendment to make way for the anti-racist amendment?

Kendi’s proposal continues:

[The anti-racist amendment] would establish and permanently fund the Department of Anti-racism (DOA) comprised of formally trained experts on racism and no political appointees. The DOA would be responsible for preclearing all local, state and federal public policies to ensure they won’t yield racial inequity, monitor those policies, investigate private racist policies when racial inequity surfaces, and monitor public officials for expressions of racist ideas. The DOA would be empowered with disciplinary tools to wield over and against policymakers and public officials who do not voluntarily change their racist policy and ideas.

Kendi’s goals are openly totalitarian. The DOA would be tasked with “investigating” private businesses and “monitoring” the speech of public officials; it would have the power to reject any local, state, or federal policy before it’s implemented; it would be made up of “experts” who could not be fired, even by the president; and it would wield “disciplinary tools” over public officials who did not “voluntarily” change their “racist ideas”—as defined, presumably, by people like Kendi. What could possibly go wrong?

The odds of Kendi’s proposal entering the political mainstream may seem miniscule and therefore not worth worrying about. But that’s what people said about reparations as recently as two years ago. In the long run, American public opinion on race will change. In five, ten, or 50 years, supporting an anti-racist constitutional amendment might become the new progressive purity test.

Kendi, however, doesn’t think it’s likely. Despite the wild success of his own book tour––drawing crowds “so large that bookstores have resorted to holding readings in churches, synagogues and school auditoriums”––he nevertheless thinks that the antiracist project will probably fail. For one thing, he doesn’t believe that people can be persuaded out of racism. “People are racist out of self-interest, not out of ignorance,” Kendi writes. Thus, racists can’t be educated out of their racism. “Educational and moral suasion is not only a failed strategy,” he laments, it’s a “suicidal” one.

This is a tough claim to square with the rest of the book, which contains story after story in which Kendi gets persuaded out of his racist beliefs––including one where a friend named Clarence reasons him out of believing that white people are extraterrestrials. Indeed, what makes Kendi’s personal story so compelling is precisely the fact that he’s constantly changing. That said, when reflecting on his college days, Kendi describes his former self as “a believer more than a thinker,” so perhaps not everything about him has changed.

How to Be an Antiracist is the clearest and most jargon-free articulation of modern antiracism I’ve read, and for that reason alone it is a useful contribution. But the book is poorly argued, sloppily researched, insufficiently fact-checked, and occasionally self-contradictory. As a result, it fails to live up to its titular promise, ultimately teaching the reader less about how to be antiracist than about how to be anti-intellectual.

==

"I would define [racism] as a collection of racist policies that lead to racial inequity that are substantiated by racist ideas."

-- Ibram X. Kendi

-

"I take umbrage at the lionization of lightweight, empty-suited, empty-headed mother-fuckers like Ibram X. Kendi, who couldn’t carry my book-bag."

-- Glenn Loury

#Coleman Hughes#Kendi is a racist#Ibram X. Kendi#Henry Rogers#How to Be an Antiracist#antiracism as religion#antiracism#anti intellectualism#anti intellectual#intellectual fraud#religion is a mental illness

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back on my reading goals! Next up....

#books and reading#how to be an antiracist#black liberation#social justice books#black lives matter#education#black authors

0 notes

Text

Let’s go!

#witchblr#witches of tumblr#tarot for the hard work#how to be an antiracist#tarot#tarot reader#what I’m reading

1 note

·

View note

Text

Always remember that we cannot change the hearts of man. We can pray but we cannot change their heart. Sometimes we get beside ourselves and think that we can change who people are by being our best selves. Well here is three things you can do to ensure you aren’t playing God.

1. Pray- Give everything to God. At the end of the day He is the one who has the final say. Surrender BOTH the situation and the person to God and let Him do the rest.

2. Self Reflect- Take a step back and look at how you are behaving. Are you being controlling and pushy? Are you trying to change this person for you? Are you loving them unconditionally flaws and all? Do you love and like yourself? Sometimes our actions towards others is a reflection of how we feel about ourselves.

3. Remain Patient and Faithful- Nothing in this life is easy and instant. Things take time and lasting changes do not happen overnight. Be patient and always extend grace.

#love#ahduck#single living#black single female#dating#tumblr#barbie#love life#god is good#be patient#how to be patient#how to be an antiracist#how to be a human being#daddy's good girl

1 note

·

View note