#language history

Text

The Czechs would like to have a chat

Edit: since this post blew up: This was intended as a sharing of a funny blunder I found in a book, and to prompt the sharing of the stories of other marginalized languages.

It was NOT intended as an invitation for people to a) call all English speakers stupid and imply they all think like this and b) trashtalk the authors, who, apart from this singular paragraph, wrote an immensely valuable resource for anyone interested in the history of English and arguably have achieved more within the linguistic community than any of us will.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

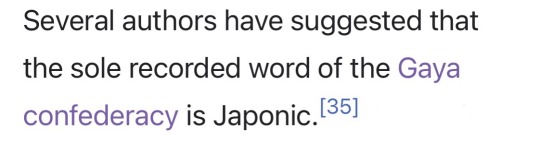

i found out about a language with one recorded word left a few weeks ago and i can’t stop thinking about it

i was reading random stuff and the reference to “the sole recorded word” of a language just struck me in a way. but i can really only just look at the one word there is and think about how a whole society once spoke a whole language and now there’s one word left to speak for that language. one word left that that society spoke. and people make all kinds of speculations about that society based on the one and only known word. just a random word that someone bothered to write in a document that happened to survive til now. just one word left. just one word.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

~Languages~

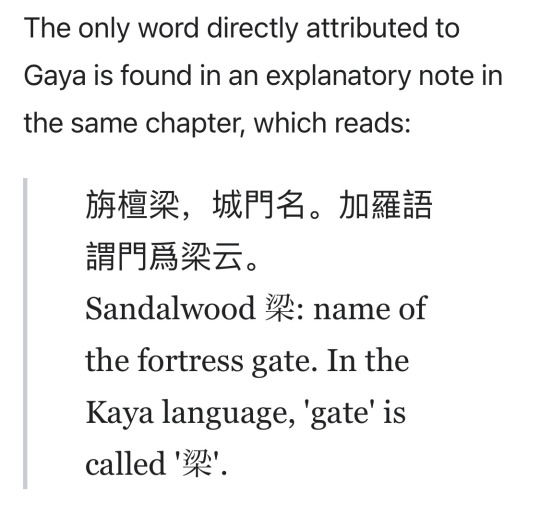

Obviously BES is dubbed entirely in whatever language the audience is watching it in, but how much Japanese would Fowler actually be speaking and when?

Obviously during diplomatic exchanges and monologues towards the Shogun he would be speaking (Early Modern)Japanese (use of Late Middle Japanese phased out around the 16th century and Early Modern Japanese began use around the 17th century, so I'm not sure if it would be one, the other, a mix or even a particular dialect I haven't considered ^^'). Personally I'd love to hear what Japanese would sound like through a relatively thick Irish accent. But with Heiji? I reckon Heiji would know at least some (Early Modern) English and use it with Fowler and the other white men for trade purposes.

(Early modern English / the transition to modern English started bang on around the time BES takes place - the mid to late 17th century!)

That said, I reckon Fowler would want to speak Gaelic more than English where possible as a minor rebellion against the Tudors' attempts to subdue the Irish language. He'd only be using English with Heiji and other middlemen because it was the main language of trade. Fowler's english surname and his role in trade clearly shows he's willing to play into the power structures set up by the British to thrive within them, but I feel he only weilds them (as the English language) only insofar as they're useful.

In Fowler's conversation with God though, it'd be interesting if he spoke in Gaelic (specifically, Early Modern Irish). And just generally if he was voicing his inner monologue or any derrogatory thoughts others needn't hear he'd probably speak in Gaelic. Also, with how classical gaelic was taught and used in bardic poetry I'd love to try and learn it if only to rewrite some of Fowler's dialogue as bardic poetry! ^^

Also I'm excited to see how they handle Mizu's language barrier in London, and how much English Fowler might teach Mizu. Since everything is still dubbed entirely in English, it's easy to forget that Mizu probably wouldn't be fluent, so conveying any lack of understanding and miscommunications may be difficult when, to us, everyone's speaking the same language.

Plus, if Fowler's the one teaching Mizu English, surely Mizu would have a slight Irish accent when they speak English? Amusing to imagine ^^

Just ramblings me and my friend had about the show's time period :3

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lingthusiasm Episode 88: No such thing as the oldest language

It's easy to find claims that certain languages are old or even the oldest, but which one is actually true? Fortunately, there's an easy (though unsatisfying) answer: none of them! Like how humans are all descended from other humans, even though some of us may have longer or shorter family trees found in written records, all human languages are shaped by contact with other languages. We don't even know whether the oldest language(s) was/were spoken or signed, or even whether there was a singular common ancestor language or several.

In this episode, your hosts Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne get enthusiastic about what people mean when we talk about a language as being old. We talk about how classifying languages as old or classical is often a political or cultural decision, how the materials that are used to write a language influence whether it gets preserved (from clay to bark), and how people talk about creoles and signed languages in terms of oldness and newness. And finally, how a language doesn't need to be justified in terms of its age for whether it's interesting or worthy of respect.

Read the transcript here.

Here are the links mentioned in the episode:

Lingthusiasm episode 'Tracing languages back before recorded history'

'My Big Fat Greek Wedding- Give me any word and I show you the Greek root' on YouTube

Glottolog entry for 'classical'

Wikipedia entry for 'Complaint tablet to Ea-nāṣir'

Wikipedia entry for 'Bath curse tablets'

Wikipedia entry for 'Cuneiform'

Wikipedia entry for 'Mesopotamian writing systems'

Wikipedia entry for 'Home Sign'

Lingthusiasm episode 'Villages, gifs, and children: Researching signed languages in real-world contexts with Lynn Hou'

Wikipedia entry for 'Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language'

Wikipedia entry for 'Kata Kolok' (also known as Benkala Sign Language)

True Biz by Sara Nović on Goodreads

Gretchen's thread about reading True Biz

You can listen to this episode via Lingthusiasm.com, Soundcloud, RSS, Apple Podcasts/iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also download an mp3 via the Soundcloud page for offline listening.

To receive an email whenever a new episode drops, sign up for the Lingthusiasm mailing list.

You can help keep Lingthusiasm ad-free, get access to bonus content, and more perks by supporting us on Patreon.

Lingthusiasm is on Bluesky, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Mastodon, and Tumblr. Email us at contact [at] lingthusiasm [dot] com

Gretchen is on Bluesky as @GretchenMcC and blogs at All Things Linguistic.

Lauren is on Bluesky as @superlinguo and blogs at Superlinguo.

Lingthusiasm is created by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our senior producer is Claire Gawne, our production editor is Sarah Dopierala, our production assistant is Martha Tsutsui Billins, and our editorial assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is ‘Ancient City’ by The Triangles.

This episode of Lingthusiasm is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license (CC 4.0 BY-NC-SA).

#linguistics#language#lingthusiasm#episodes#podcast#podcasts#episode 88#language history#oldest language#classical languages#ancient languages#sign language#home sign#cuneiform#writing technology#writing systems#SoundCloud

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Be wary of linguistics rant, Elden Ring ahead

Ok so I just made a different post about this but I need to elaborate: The Elden Ring messaging system is legitimately such an interesting microcosm about how language is used as a tool and shaped to suit the needs it's being used for. I could actually make an entire study about how this can be used to better understand the formation of pidgin languages in the same way that epidemiologists studied the Corrupted Blood Incident in World of Warcraft to better understand the mechanics of how disease affects human behavior. Video games as an academic lens into peoples' minds has always been a fascinating topic to me, and by the end of this, you'll see why.

First off, message.

So for those not indoctrinated into the series/game, Elden Ring is a big open world game made by From Software, which won game of the year 2022 among some other awards (if you've played it or know anything about it, just skip to the next header). Each player plays as a Tarnished and explores this massive environment called The Lands Between individually, but if another player is walking in the same area that you are, you can see their "ghost" moving through the world, and you can "invade" or "be summoned" into another player's iteration of the world in order to briefly interact with it before returning to your own iteration. This occupies a weird space in between singleplayer and multiplayer, with these heavily limited and kind of random methods of interaction between players, but that's not the most interesting way of communicating with your fellow Tarnished; that title goes to the messages system. You can write a message onto a small stone, and leave it on the ground, and then that little stone with the message on it will have a random chance to appear in any player's iteration of the world for them to read. This is a tradition which has been going in From Software's games long since before the inception of Elden Ring, although I'm mostly going to be focusing on the message system of that title, because documenting the history of the 13+ years running Soulsbourne franchise is way too much, even for a nerd like me. The point is that messages are a lot more likely to be seen than any other method of player-to-player interaction, and you can even leave little "gestures" to go with them, where the reader can see your character striking a pose while they read the message. What a neat little mechanic, which definitely doesn't have any hidden layers of depth, and certainly wouldn't spawn an entire emergent system of pseudolinguistics, right?

No message ahead, be wary of mimicry

Well, when I said that messages are written by other players, that was a lie. To make a message, you don't type it out with your keyboard, you select what you want to say, from a big list of preset phrases. It works that way for a lot of reasons, foremost of all as a profanity filter, but also to prevent too many spoilers and maintain atmosphere. The sets of phrases are incredibly limiting, famously requiring players to use weird fake old-english diction in order to express a simple thought (Strong foe ahead, be weary of death. Look carefully ahead, visions of item. Suffering, o suffering, why is it always bad luck? etc). This seems like a limitation which would put a serious damper on anyone trying to actually communicate their thoughts, but gamers are a persistent sort, and have a lot of trouble taking no for an answer. They also have way too much time on their hands, and like to solve puzzles, a terrifying combination of traits, and the perfect one to accidentally create a conlang. With the unexpectedly massive audience that this game picked up on launch, millions of people left messages desperately trying to get something across, and if the game's preset vocabulary didn't contain the phrases to express it, they would forge their own path. Any big fans of linguistic history can already tell the direction that this might be going, as we move on into the next chapter:

Teacher, Liar, Lovable Sort

When the game released, there was chaos. The Lands Between are fraught with hidden passages, deception, and blatant bullshit, and the first kind of players leaving messages tried to helpfully communicate what you could trust, and what you couldn't. This is what the message system was intended for after all, giving advice to your peers, and what many people still use it for today. The second kind of players tried to do the opposite, deliberately leading people to their doom, just because they could. The third, and most numerous sort, were simply awestruck at everything the game had to offer, and left a series of remarks on the beauty and humor of the world. The messages left by each group are pretty easy to differentiate to the trained eye, which is the main feature causing me to point out this division of players. Let's call these groups the teachers, the liars, and the lovable sorts. A teacher can be recognized if their messages suggest something within reason, and being backed up by the peer-review of nearby messages to the same effect. If three messages are all sitting on the ground next to eachother, each saying something along the lines of "seek up, look carefully ahead", then a local collage of teachers are trying to let you know about a secret path ahead leading you up towards a hidden objective. However, a single message next to a bloodstained cliff-edge stating "jumping required ahead" is almost certainly a liar, trying to deceive an unsuspecting player into making a dubious leap. Liars sometimes use slightly simpler grammar than teachers do, being less committed to getting their point across. Wait a minute, linguistic variance based on intent? No no, this is just a video game about fighting monsters, surely such an interesting emergent system wouldn't arise from something like that. Lastly, the lovable sorts have the most ranging grammar, spanning from a simple word such as "dog" (a word used colloquially to describe all creatures, from turtles to dragons), to complex sentences requiring the combination of many phrases. However, a lovable sort can be differentiated by the fact that they merely remark upon the world as it is, instead of trying to offer advice to other players, as a teacher or liar might. Some of their most iconic phrases are "Elden ring ahead", used to sarcastically denote a dead end where a player might have been expecting treasure, "you don't have the right, o, you don't have the right" which indicates a locked door, or the world-famous "try finger, but hole", a phrase which explains itself. The most incredible thing about the words of the lovable sort, is that they all require a little bit of thinking to understand their actual meaning, but once you get the hang of it, it becomes like a second language to you! Wait a minute, a second language?

Message? Wasn't expecting introspection

As time went on, the three main groups of message-writers still kept chugging along, creating new works of writing every day, but advancements in understanding of the game's inner workings allowed these messages to become more and more complex. Compound words started to be formed to represent concepts outside of the preset vocabulary, like "skeleton, house" for coffin, "dung, key" to describe the donkeys accompanying traveling merchants, and "edge, lord" being used to refer to the NPC Ensha, a man wearing flamboyant armor made out of bones who takes himself way too seriously. It's worth noting in this section that for a specific period of time, The Lands Between were overtaken by a horde of messages stating only the words "fort, night". Despite the crude and humorous nature of the entire thing, it was clear to see that the linguistic patterns of the Elden Ring community were evolving into their own beast, far beyond the usages that the developers had intended. Words had shed their original meaning, to instead take up contextual meanings based on how players used them, effectively becoming different words entirely. Depending on how you define this, it's either a microcosm of incredibly fast and severe linguistic drift, or the emergence of a new pidgin or conlang entirely. If you really stretch things, you could almost call the message system of Elden Ring an entirely new language in and of itself.

Well done, victory ahead!

I think that video games are an excellent way to observe human behavior under conditions which are controlled, accelerated, and completely recordable, and this is the closest that we've ever seen to an entire language growing completely from scratch. People are always the same, whether you want to call it instinct or just cyclical tendencies, but normally the formation of a new language can take incredible periods of time, hastened only by tragic events like diaspora or massive losses of cultural knowledge (research what's been happening to Gaelic as a spoken language for more info about this sort of thing, it's kind of depressing but is also important to learn about, and there's a lot of people on this site talking about it who can do the topic way more justice than I can). Even for other topics which either require great passage of time, or great tragedy in order to research (I.E. geology or epidemiology, respectively), there are a lot of simulations and predictive models which can tell us how these systems behave without actually experiencing them. Linguistics has never had this sort of thing...until now, perhaps. Obviously there won't be any academic breakthroughs based on a bunch of people online all writing "rump ahead", but it's an incredibly interesting thing to see happening for a field which is so hard to actively advance, and it could lead to actual scientific methods of generating new languages via human interaction for research purposes. Of course, there's always the sizable chance that this goes nowhere and I just wrote this insane rant because I like to type, but if nothing else, I at the very least exposed some of my mutuals to "try finger, but hole".

#elden ring#linguistics#elden ring ahead#behold dog#dung key#pidgin language#pidgin#language#old english#linguistic studies#language history#conlangs

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

My choir is rehearsing for the upcoming season; here's our rendition of "Kinderly", a 14th century poem in Middle English set to music by Katharine Blake of the group Mediaeval Baebes.

Kyndeli is now mi coming

in to ȝis werld wiht teres and cry;

Litel and pouere is myn hauing,

briȝel and sone i-falle from hi;

Scharp and strong is mi deying,

i ne woth whider schal i;

Fowl and stinkande is mi roting—

on me, ihesu, ȝow haue mercy!

----

Kinderly is now my coming

into this world with tears and cries;

Little and poor is my having,

brittle and soon I fall from high;

Sharp and strong is my dying

I know not whither shall I;

Foul and stinking is my rotting —

on me, Jesu, you have mercy!

#it's a real break from shepherds in the fields fa la la la la I gotta say#the guys are on percussion in the background#'kinderly' is hard to translate#the idea is that they're like a baby coming into the world crying#'childlike' maybe#language history#music history#memento mori

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

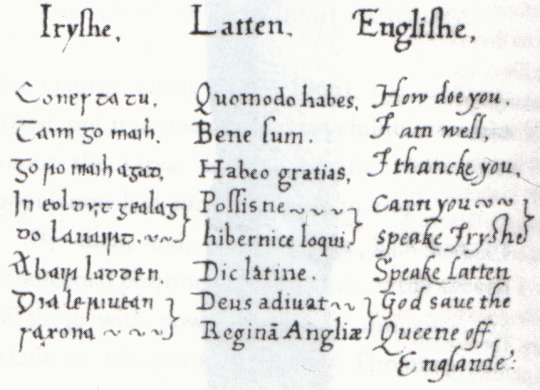

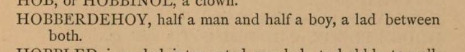

perusing the Good Book, the Scriptures, the Truth (Francis Grose's Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue) and I finally found an old-timey word for teenager:

Honestly, petition to use this instead of teenager now.

#18th century#18th century slang#slang#linguistics#language stuff#language history#English#18th century english#classical dictionary of the vulgar tongue#my beloved

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

the past tense of bake used to be what now?

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily Etymology #153

Potato

Potato came from the Spanish patata, which was derived from the Taíno batata, meaning sweet potato. Taíno is the language of the Taíno people, an Arawak culture native to the Caribbean and Florida. The Spanish brought this word back with them, along with the plant itself, when they returned from colonising America in the 1500s.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

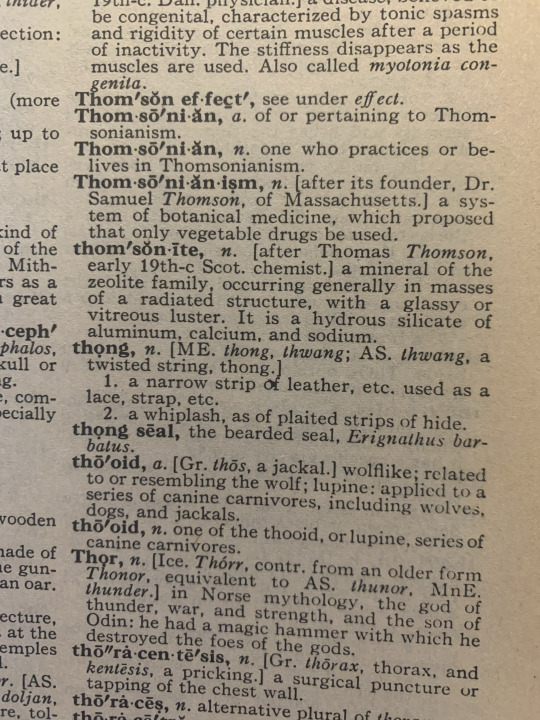

now heres an interesting addition to my quest to find all old pronouns.

so, I bought a book. exciting, right? that book is the second edition of the merriam webster unabridged dictionary, printed from 1934 to 1961. this thing is fucking massive, its 11′ by 8.5′ by 4.5′ and weighs so much. i paid like 40 dollars for it. Anyway, i got this book because of this quote, on the merriam websters dictionary page: 'Thon', short for "that one," appeared in our Unabridged dictionary from 1934-1961. Though the word was dropped for lack of use, other gender-neutral pronouns—'they', 'their', and 'them'—remain.*

This is cool, right? the article includes a picture of the entry, but that isn’t good enough for me, i need the book itself.

so, it came. guess whats missing?

thats right, the word i bought it for. this is super cool, to be honest. as frustrating as it is to still not have a physical copy of this entry, the exclusion of the word from this dictionary is Fascinating. why is it excluded?

i cant tell what year this specific dictionary is from, but i know it isnt an ‘early addition,’ as (apparently) the word Dord was in early editions but edited out of late prints because it was a mistake. Plus, the website says it was in every second edition dictionary from 1934-1961, which was all of them, so I would assume they all have thon, but obviously, they do not.

My only theories are that it is specifically only in the unabridged dictionary, whereas I have the new universal deluxe edition, however, i cant really see this being the case? it is a collection of all of their second edition books, as far as I know? does anyone have any ideas for this missing word?

*the article is “The History of 'Thon', the Forgotten Gender-Neutral Pronoun”

108 notes

·

View notes

Video

a closed language

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

gender oppression is the result of language.

post modern feminists

the crux that the above statement holds is how the society & their derogatory remarks has been gender based. the common connotations that we use in daily life more often shows the patriarchal approach since the ages.

for ex : in the modern times, the women reproductive part is used as a term to symbolise a person who's weaker in any manner, who's lacking gut approach a task. while on the other hand men's weakest point - 'the testes' is again used to define the same feeble will of a person as in "you don't have balls man".

the society/the family/the group has always used language mechanisms to lower the standard of a woman. one might hear it on a daily basis. for ex : in Dangal Movie Amir Khan quoted " मारी छोरियां, छोरो से कम हैं के" at a moment it feels like wow but then you realise that even to lift up the girls spirit he's actually accepting that the bar set up by the boys is actually higher than the girls. he's actually establishing a mere fact that girls are not equal.

let me give you another example: tiger shroff's famous meme "छोटी बच्ची हो क्या" nobody questioned why not ’ बच्चा ’ which symbolises that yes the society accepts that the women are the trademark of 'crying'.

every slang which modern society uses to show the anger is based on demeaning a woman or her body parts & even the woman enjoys using such slang which shows how effortlessly the language has penetrated our mind.

once we start making ourselves of the fact that the major part of our life is governed by the kind of language or dialects we use. we can change the discrimination in any major grounds.

-apollo

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Epicine & Neopronouns That Predate 1999

This list is very long, with many similar pronouns! Contrary to popular belief, neopronouns aren't that new, and were never that rare. A noticable potrion of this list contains neopronouns 100 or more years old, and even more that are 50+ years old!

The vast majority pronouns in this post are sourced from Aether Lumina. Some pronouns were left off this list, so if you want to dig deeper, check the page out!

And we're not kidding--the list under the cut is LONG!

Non-Alphabetical

[name]/[name]/[name]s/[name]s/[name]self [replace [name] with person’s name, ie Alex would be Alex/Alexs]

*e, h*, h*s, h*s, h*self (splat pronouns, c.1990s) [source] [source2]

þe/þim/þir/þirs/þimself (þ is pronouned th & þe rhymes with he, 1978) [source] [source2]

3e/3im/3er/3ers/3imself (3 is pronounced z &3e sounds like zee, 1995) [source]

ðe (conjugation unknown, 1995) [source]

A-G

a/a/as/as/aself (from Middle english, 1789) [source] [source2]

ae/aer/aer/aers/aerself (1920) [origin/source]

ala/alum/ales/ales/alumself (derived from Latin and Hawai'ian, 1989) [source] [source2]

che/chim/chis/chis/chimself (1951) [source]

co/co/cos/cos/coself (1970) [source]

e/em/eir/eirs/emself

E/Em/E's/E's/E'sself (c.1977) [source]

e/em/es/es/esself or emself (1878 and 1890) [source]

E/Ir/Ir/Irs/Irself (1982) [source]

e/rim/ris/ris/risself (1977) [source]

em/em/ems/ems/emsself (1977) [source]

en/ar/es/es/esself (1974) [source]

en/en/en/ens/enself (1868) [source]

er/er/ers/ers/erself (1863) [source]

et/et/ets/ets/etself (1979) [source]

ey/em/eir/eirs/eirself (Elverson pronouns) [source]

fm/fm/fms/fms/fmself (1972) [source]

ghach (Klingon, conjugation unknown, 1992) [source]

H

ha/hem/hez/hez/hezself (1927) [source]

han/han/hans/hans/hanself (1868) [source]

hann/hann/hanns/hanns/hannself (1984) [source]

he/him/his/his/himself (generic; not actually a neopronoun)

he'er/him'er/his'er/his'er's/his'er'self (1912) [source]

heesh/heesh/heeshs/heeshs/heeshself (c.1940) [source]

heesh/herm/hiser/hisers/hermself (1978) [source]

heesh/himer/hiser/hisers/hiserself (1934) [source]

hem/hem/hes/hes/hesself (1974) [source]

heor/himor/hisor/hisor/himorself (1912) [source]

her'n/her'n/her'ns/her'ns/her'nself (1935) [source]

herm/herm/herm/herms/hermself (1985) [source]

hes/hem/hir/hirs/hirself (1935) [source]

hes/hes/hes/hes/hesself (1984) [source]

hesh/himmer/hizzer/hizzers/hizzerself (1927) [source]

hesh/hiser/himer/himer/hermself (1974) [source]

heshe/hem/hes/hes/hemself (1981) [source]

hey/heir/heir/heirs/heirself (1979) [source]

hi/hem/hes/hes/hesself (1884) [source]

hir/hirem/hires/hires/hirself (1979) [source]

h'orsh'it (1975--joke pronoun but it rocks) [source]

ho/hom/hos/hos/homself (1976--not a joke pronoun but prone to jokes) [source]

hor/hor/hors/hors/horself (1890) [source]

hse/hse/hses/hses/hseself (1945) [source]

hu/hum/hus/hus/huself (1982) [source]

hymer/hymer/hyser/hysers/hyserself (1884) [source]

I-P

id/idre/ids/ids/idself (1989) [source]

ip/ip/ips/ips/ipsself (1884) [source]

ir/im/iro/iros/iroself (1888) [source]

kai/kaim/kais/kais/kaiself (1998) [source]

kin/kin/kins/kins/kinself (1969) [source]

le/lem/les/les/lesself (borrowed from French, 1884) [source]

le/lim/lis/lis/limself (1884) [source]

na/na/nan/nans/nanself (1973) [origin/source] [source2] [source3]

ne/nem/nir/nirs/nemself

ne/nim/nis/nis/nimself (c.1850) [source]

on/on/ons/ons/onsself (1927?) [source]

one/one/ones/ones/oneself (1770) [source]

per/per/pers/pers/perself or personself (1972) [origin-ish/source] [source]

phe/per/per/pers/perself (1998) [source]

po/xe/jhe/jhes/jheself (c.1997) [source]

S-T

s/he / him/er / his/her / his/ers / him/erself (1973) [source]

se/hir/hir/hirs/hirself (1977?) [source]

se/sem/ses/ses/sesself (1990) [source]

she/herim/heris/heris/herisself (1970) [source] [source2]

she/herm/herm/herms/hermself (1976) [source]

SHe/Hir/Hir/Hirs/Hirself (1997 or earlier) [source]

shem/hem/hes/hes/hesself (1974) [source]

shem/herm/herm/herms/hermself (1973) [source]

sheorhe/herorhim/herorhis/hersorhis/herorhimself (1974) [source]

shey/shem/sheir/sheirs/sheirself or shemself (1982 & 1979) [source] [source2]

sie/hir/hir/hirs/hirself (borrowed from German, pre-2001) [source]

soloc/sebita/seniri/siculis/sulago (1998) [source]

su/su/sus/sus/suself (borrowed from Spanish, 1921) [source]

ta/ta/tas/tas/tasself (borrowed from Mandarin Chinese, 1971) [source]

tey/tem/ter/ters/temself (1971) [source]

tey/tem/term/terms/termself (1972) [source]

thir/thim/thiro/thiros/thiroselves (plural form of ir/im, 1888) [source]

thon/thon/thon/thons/thonself (allegedly 1858, definitely existed since or before 1884) [source] [source2]

U-Z

uh/uh/uhs/uhs/uhself (1975) [source]

um/um/ums/ums/umself (1877, 1879) [source]

un/un/uns/uns/unself (1868) [source]

ve/ver/vis/vis/verself (1995) [source]

ve/vim/vis/vis/visself (1974) [source]

ve/vir/vis/vis/visself (1970) [source]

xe/xem/xyr/xyrs/xemself

z/z/z/z/zself (1972) [source]

ze/zim/zee/zees/zeeself (1972) [source]

ze/hir/hir/hirs/hirself (1996) [source]

ze/zir/zir/zirs/zirself

#pronouns#neopronouns#pronoun suggestions#pronoun sets#queer history#trans history#nonbinary history#language history#queer#trans#transgender#transsexual#nonbinary#anarcha queer#pronoun list

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey can the linguistics/etymology side of Tumblr explain to me why we say His and Hers instead of "Him's" and "Her's"? While where at it, could anyone explain how we ended up having both "He/She" and "Him/Her", which are ostensibly the same words but cannot be used interchangeably? This has been gnawing at my brain all day

#linguistics#linguistry#english linguistics#English#etymology#english etymology#language#language history#grammar#just plunking all these tags in here in hopes that someone will see this#i know you nerds are out there I see you on the dash all the time#and now I am humbly begging your services

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 88: No such thing as the oldest language

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘No such thing as the oldest language. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Gretchen McCulloch.

Lauren: I’m Lauren Gawne. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about old languages. But first, our most recent bonus episode was deleted scenes with three of our interviews from this year.

Gretchen: We had deleted scenes from our liveshow Q&A with Kirby Conrod about language and gender. We talked about reflexive pronouns, multiple pronouns in fiction, and talking about people who use multiple pronoun sets.

Lauren: We also have an excerpt from our interview with Itxaso Rodríguez-Ordóñez about Basque because it’s famous among linguists for having ergativity.

Gretchen: We wanted to know “What do Basque people themselves think about ergativity?” It turns out, there are jokes and cartoons about it, which Itxaso was able to share with us.

Lauren: Amazing and charming.

Gretchen: Finally, we have an excerpt from my conversation with authors Ada Palmer and Jo Walton about swearing in science fiction and fantasy. This excerpt talks about acronyms both of the swear-y and non-swear-y kind.

Lauren: You can get this bonus episode as well as a whole bunch more at patreon.com/lingthusiasm.

Gretchen: Also, yeah, maybe this is a good time to remember that we have over 80 bonus episodes.

Lauren: We have bonus episodes about the time a researcher smuggled a bunny into a classroom to do linguistics on children.

Gretchen: We also have a bonus episode about “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” and more phrases that contain all the letters of the alphabet – plus, what people do with phrases like this in languages that don’t have alphabets.

Lauren: We also have an entire bonus episode that’s just about the linguistics of numbers.

Gretchen: If you wish you had more lingthusiasm episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help us keep making this podcast long into the future, we really appreciate everyone who becomes a patron.

Lauren: You can find all of that at patreon.com/lingthusiasm.

[Music]

Gretchen: Hey, Lauren, I’ve got big news.

Lauren: Yeah?

Gretchen: Did you know I’m from the oldest family lineage in the world?

Lauren: Wow! You sound like you are part of some prestigious, ancient, royal – I can only assume royal with that level of knowledge about your family lineage.

Gretchen: Well, you know, I have some family members who are really into genealogy. I’ve been looking at some family trees. And I have come to the conclusion that my family is the oldest family in the world.

Lauren: You know, I have grandparents, and they have grandparents, and I assume they had grandparents, and I guess my family goes all the way back as well. We didn’t come out of nowhere. I might not know all their names. I don’t think we were ever rulers of any nation state as far as I’m aware. But I dunno if you are from the oldest family lineage because I think everyone is.

Gretchen: Well, this is not a mutually exclusive statement. I can be from the oldest family lineage, and you can be from the oldest family lineage, and everyone listening to this podcast can be all from the oldest family lineage in the world because we’re all descended from the earliest humans.

Lauren: This is a good point.

Gretchen: Psych!

Lauren: I think it’s definitely worth remembering the difference between the very fact that we are all from the same humans – and the difference between that and knowing names of specific individuals back to a certain point.

Gretchen: I should clarify – I am not royalty. I do not actually know the names all the way back because at a certain point writing stops existing and, at some point before that, people stopped recording my ancestors. I don’t know when it stops.

Lauren: But there’s definitely a tradition in certain royal families and stuff of being able to claim that you can trace your family back to, you know, maybe –

Gretchen: Like Apollo or something.

Lauren: Oh, gosh, like, mythical characters, okay. I was thinking of just tracing them back a thousand years, but I guess –

Gretchen: Tracing them back to Adam and Eve or tracing them back to Helen of Troy or Apollo or these sorts of things. I feel like – at least I’ve heard of this. I think that talking about human ancestral lineages helps us make sense of the types of claims that people also make about languages being the oldest language.

Lauren: I feel like I’ve heard this before – different languages making claim to being the oldest language.

Gretchen: I’ve heard it quite a lot. I did a bit of research, and I looked up a list of some languages that people have claimed to be the oldest.

Lauren: Okay, what did you find?

Gretchen: A lot of things that can’t all be true at the same time.

Lauren: Or can all be true because all languages are descended from some early human capacity for human language.

Gretchen: Right. There’s different geographical hot spots, you know, people making claims about Egyptian, about Sanskrit, Greek, Chinese, Aramaic, Farsi, Tamil, Korean, Basque – speaking of Basque episodes. Sometimes, people look at reconstructed languages like Proto-Indo-European, which is, you know, the old thing that the modern-day Indo-European Languages are descended from. But part of the issue here is that, at least for spoken languages – and we’re gonna get to sign languages – but at least for spoken languages, babies can’t raise themselves.

Lauren: Unfortunately, I, personally, have to say after the last few years.

Gretchen: Deeply inconveniently –

Lauren: Yeah.

Gretchen: – for adult sleep schedules. If you have a baby with typical hearing, and they’re being raised in a community or even by one person, they’re gonna acquire language from the people that are raising it.

Lauren: Absolutely – in much the same way we all have people giving us genetic input, we also have people giving us linguistic input and continuing on that transmission of human language.

Gretchen: Exactly. When the languages claim to be “old,” that’s often more of a political claim or a religious claim or a heritage claim than it is a linguistic claim because we think that languages probably have a common ancestor. Certainly, all languages are learnable by all humans. If you raise a baby in a given environment, they’ll grow up with the language that’s around them. The human capacity for language seems to be common across all of us. We just don’t know what that tens-of-thousands-year-old early language looked like.

Lauren: In much the same way we lose track of earlier ancestors when we get earlier than written records. We talked about this in the reconstructing old languages episode that there’s just a point where you can’t go back further because there’s just not enough information to say exactly how Proto-Indo-European might have, at some earlier point, been related to, say, the Sino-Tibetan languages or the Niger-Congo family.

Gretchen: Right. We also talked about this in the writing systems episode where writing systems had been invented about 4,000, 5,000, 6,000 years ago, but human language probably emerged sometime between 50,000 and 150,000 years ago, which is so much older. That’s 10-times-to-30-times older than that. We don’t know because sounds and signs leave impressions on the air waves that vanish very quickly and don’t leave fossils until writing starts being developed much later.

Lauren: Very inconvenient.

Gretchen: Absolutely the first thing I would do with a time machine.

Lauren: All of those languages that you mentioned as people laying claim to them being the oldest, they come from all kinds of different language families. Although, I have to say, a very Indo-European, Western skew there, which probably reflects the corners of the internet that you have access to.

Gretchen: This reflects the people that are making claims like this on the English-speaking internet that I’m looking at and the modern-day nation states and religious traditions and cultural traditions that are making claims to certain types of legitimacy via having access to old texts or having access to uninterrupted transmission of stories and legends and mythologies that give them those sorts of claims. There’s no reason to think that a whole bunch of languages on the North and South American continents are not also equally old as all the other languages, but people aren’t doing nation state building with them, and so they don’t tend to show up on those lists.

Lauren: Yeah. A lot of nation state building, a lot of religion happening there as well. I think about how yoga is – I love a bit of yoga, and I think it’s really lovely that all the yoga terms are still given to you in this older Sanskritic language, but it definitely is done sometimes with this claim to legitimacy and prestige in the same way that having something in Latin for the Catholic Church gives that same kind of vibe.

Gretchen: I think about this scene from the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding where you have the daughter, who’s the one that’s getting married. She’s in the car as a teen with her parents. It’s this scene where the parents are being a bit cringe-y in the way that teens often experience their parents to be. The dad is saying, “Name a word. I will tell you how it comes from Greek,” because he’s got this big Greek pride thing going.

Lauren: This a classic Greek-American migrant pride happening.

Gretchen: Right. He says, “arachnophobia,” and he’s explaining how the roots come from Greek, and that one’s true. Then the daughter’s friend, who’s in the back seat, is rolling her eyes and saying, “Well, what about ‘kimono’?”

Lauren: Ah, “kimono” the Japanese robe?

Gretchen: Yes. The Dad’s like, “Oh, no, it’s from Greek. Here’s this connection that I have found.”

Lauren: I like his linguistic ad-libbing skills.

Gretchen: It’s certainly a great improvisational performance skill. The movie is clearly designed to put the viewer in sympathy with the young girls in the back seat who are teasing him, and the daughter’s face-palming at this claim, which is one of the reasons why it’s one of my favourite examples of people making up fake etymologies in media because you don’t leave the movie thinking, “Oh, I never realised ‘kimono’ was from Greek.” You leave that movie being like, “Ah, here’s this dad who has over-exaggerated pride in his heritage that doesn’t allow for other people’s heritage to also have words that come from them.” It’s a claim that he's making for personal reasons and for heritage reasons that doesn’t have linguistic founding, but none of these claims have linguistic founding.

Lauren: The dad has come kind of close to a linguistic truth though, which is that linguists talk about languages having features that can be either conservative or innovative. Modern Greek has a lot of the same sound features as Ancient Greek, which is probably helped by that consistent writing system. A writing system definitely helps transmission stay stable because you can point back to older texts. English has probably slowed down a lot in its change because of the writing system as well.

Gretchen: Genuinely, English has borrowed a lot of words from Greek – as well as a lot of other languages that are not Greek. This gets to both Greek and Sanskrit and Chinese having these eras that are talked about as “classical” or as “old,” which is an era that the present-day people, or some slightly earlier group of people, looked back on and thought, “Yeah, those people were doing some cool stuff. We’re gonna call it ‘classical’ because we liked it in history.”

Lauren: I do love the idea that Chaucer had no idea that he was moving on from Old English to Middle English because there wasn’t a Modern English yet.

Gretchen: How could you describe yourself as “Middle English” – that’s sort of like the “late-stage capitalism” that implies that we’re towards the end of something. Like, we don’t know, folks.

Lauren: I don’t think English always does self-deprecating well. English has a lot of belief in its superiority as a language. I think we can say that about the ideology behind English. But I do love that English didn’t go for “Classical English.” Imagine if we said Beowulf was written in “Classical English.”

Gretchen: We could have, yeah. We could have.

Lauren: We just went with, “Ah, that’s old. I don’t understand it. It’s got cases. It’s got all these extra affixes. It’s old. It’s a bit stuffy.”

Gretchen: That may have been because they were comparing it already to Classical Latin and Classical Greek, which was even more antique. The English speakers were looking elsewhere for their golden age. I don’t think people often claim that English is the oldest language because English speakers are seeing the history of their society located in this Greco-Latin tradition.

Lauren: Yeah, I think that’s a good explanation for it. I do wonder if maybe the attitude that we now have towards Shakespearean English, if maybe that will become “Classical English” when we’re a bit further on, and Shakespeare becomes even less accessible.

Gretchen: Right. And if Shakespeare becomes the text that everyone is referring to because it’s this quote-unquote “classic” text but calling something a “classical era” reflects on the subsequent era and what they thought about the older one more so than the era itself.

Lauren: Having this ability to distinguish between an “old” or a “classical” and a “modern” version of a language requires that writing tradition, whereas the majority of human languages, for the majority of human history, have happily existed and transmitted knowledge without a writing system. These writing systems make us very focused on pinning down. I super appreciate the website Glottolog, which catalogues languages and all the names they’re known by. We have a lot of languages that are “classical,” like “Classical Chinese” or “Classical Quechua.” We have some “early” – so “Early Irish.”

Gretchen: I think I’ve also heard of “Old Irish.”

Lauren: We have “Old Chinese” and “Old Japanese” in Glottolog, but I’ve definitely also heard them referred to as “classical,” so slightly different vibes there. Of course, you have things like “Ancient Hebrew,” which, older than old, very prestigious. I particularly like the precision with which some names get given to different languages over time. Glottolog has an “Old Modern Welsh,” which is nice and specific. I particularly appreciate the “Imperial-Middle-Modern Aramaic.”

Gretchen: “Imperial-Middle-Modern Aramaic.” That also gets to languages being named and being spread through empire and conquest and wars, which is also part of that historical tradition that people look back to.

Lauren: For sure. That’s part of the narrative building around languages. A lot of what is maintained about a language is religious documents or documents of imperial rule. That means that that imperial form might have been a particular register. Imagine if all that we had about English was the tax forms that we have.

Gretchen: Oh, god, that would be really boring.

Lauren: You would have a very different idea of what English is compared to how it’s spoken day-to-day. That’s what makes this understanding of old languages just from a written record really challenging.

Gretchen: When I think about trying to understand the history of languages just from the written record, I’m reminded of this classic joke – I dunno if you’ve heard this one – where you’re walking down the street one night, and you see someone standing under a streetlight looking at their feet and trying to search for something. You go, “Oh, what are you looking for?” And the person says, “Oh, my contact lens. It fell out. I’m trying to find it.” And you say, “Oh, did you lose it under the streetlight?” And the person goes, “No, I lost it a block over that way, but there’s no streetlight there, so it’s much easier to search here.”

Lauren: [Laughs] Hmm.

Gretchen: I guess this is a joke that doesn’t work so well now that everyone has phones with flashlights on them, and contact lenses have improved their technology and don’t pop out spontaneously like that. But when we’re looking for the history of language, it’s like looking under the streetlight because that’s where it’s easy to look. It’s not actually doing a random sample of all of the bits of history – many of which are just lost to us.

Lauren: Indeed. I like thinking about the imperial languages and the classical languages because sometimes we do get written records that help give us a glimpse into just how ordinary people were going about living their lives.

Gretchen: Oh, oh, oh, oh, oh, can we talk about the clay tablet?

Lauren: We can absolutely talk about the clay tablet that I know what you mean because you’re talking about the complaint to Ea-nāṣir, which is a clay tablet that’s written in Akkadian cuneiform. It’s considered to be the world’s oldest known written complaint.

Gretchen: This is from a customer named Nanni who’s complaining about the quality of the copper ingots that was received.

Lauren: The thing that I love about this is that there is this complaint, but also, they’re pretty sure they found Ea-nāṣir’s house because there are other complaints about the quality of the copper in this residence.

Gretchen: We really think we know who’s at fault here.

Lauren: Yeah. It seems like he was just a provider of adequate quality copper, and people really needed to go to a better place to get a better quality of copper.

Gretchen: Cuneiform is also this interesting example of searching under the streetlight for the contact lens because the language Sumerian was written in cuneiform, and then later, Akkadian, which is a Semitic language related to modern-day Arabic and Hebrew, and Hittite, which is an Indo-European language related to English and Sanskrit and a bunch of other languages. They were all using this system of stamping the ends of reeds in these pointy triangle shapes onto clay blocks. Do you know what happens to clay blocks when they’re in a house, and the house burns down?

Lauren: They just get fired and made more resilient.

Gretchen: They get made incredibly durable. If people were writing on parchment or in textiles – like in fabrics or cords or strings or on leather or wood – most of those don’t get preserved the same way because you expose them to water, and they start rotting.

Lauren: And they don’t do great with fire.

Gretchen: They really don’t do great with fire. Animals will eat them. Clay has none of these problems. We don’t even know if we know what all of the ancient writing systems are because the ones that have survived are the ones on clay or stone.

Lauren: I was so charmed when I learnt about Latin curse tablets, which are very similar to the complaints to Ea-nāṣir. These are small bits of lead that people could scratch a curse or a wish onto, and then they would throw them into some kind of sacred water. They found, like, 130 of these at Bath in Britian, but they appear to have popped up all over the Roman Empire. It’s just like these tiny insights into the pettiness of humanity as opposed to the great works of literature, or we’ve talked about how the Rosetta Stone was in these three official languages and was all about a declaration about taxation.

Gretchen: But instead, you can have “This curse is on Gaius because he stole my dog” sort of thing.

Lauren: “I have given to the goddess Sulis the six silver coins which I have lost. It is for the goddess to extract them from the names written below” – and then just lists people who owe this person cash.

Gretchen: That’s petty. I like it.

Lauren: Yeah, so annoyed.

Gretchen: I actually read a romance novel called Mortal Follies by Alexis Hall, which was set in Bath and used the ancient Bath curse tablets as a plot point.

Lauren: So charming.

Gretchen: If anyone wants to read curse tablets and also “romantasy” I think is what we’re calling the genre now.

Lauren: I feel like Jane Austen would’ve included curse tablets if she knew about them.

Gretchen: I think she was no stranger to pettiness. It’s very convenient that they wrote their curses on lead tablets, which is such an incredibly durable format. Imagine if they’d written them on cloth, and then we’d never have them for posterity.

Lauren: I feel sad for all the human pettiness that we’ve lost access to.

Gretchen: Two other old writing systems that we have access to because of the durability of the materials they were written on are oracle bone script, which is the ancestor to Chinese – another writing system that we think developed from scratch because we can see it developing thousands of years ago.

Lauren: Oracle bones written on I believe turtle bones and turtle shells.

Gretchen: Yes, hence the “bone” part – also very durable material and also used for religious purposes.

Lauren: My sympathy and thanks to the turtles.

Gretchen: Indeed. Then the early Mesoamerican writing systems, of which the oldest one is the Olmec writing system, which were written on ceramics. They show representations of drawings of things that look like a codex-shaped book made out of bark which, obviously, we don’t have. We just have ceramic drawings of the bark. Come on!

Lauren: Oh, no!

Gretchen: Ah, it’s so close!

Lauren: How cruel to point out that we’re missing information.

Gretchen: You thought you were mad about the Library of Alexandria burning down. Wait until you hear about the Olmec bark.

Lauren: Yeah, ah, that really gets you and just is a reminder of how much we can’t say about the history of human language because of what we don’t have a record of.

Gretchen: Well, you know, before we do a whole episode about things that we don’t know – because much as we can make fun of searching for the contact lens under the streetlight, we don’t know what we don’t know.

Lauren: Indeed.

Gretchen: What’s something else that people sometimes mean when they say a language is “old”?

Lauren: Well, this goes back to that conservative idea that some languages just have conservative features that haven’t changed as much. A language that has a lot of sound changes we might call very “innovative,” or they’ve “innovated” a new way of doing the tense on the verbs. You can trace it back to an older form of the language, but it looks very different at this point in time.

Gretchen: I think the example that I’m most familiar with this is Icelandic versus English. In the last thousand years or so, English has had a lot of contact from things like the Norman Conquest, which introduced a lot of French words to English, compared to Icelandic, which has had less of that. Icelanders have an easier time reading something like their sagas, which are 800 and more years old, than English speakers have reading texts like Chaucer, which are about the same age but have had a lot more linguistic changes happening because of more contact in English over the years.

Lauren: That’s one of the things that linguists who look at when a language tends to be more innovative and change, it tends to be during these periods of contact. It tends to be during periods of invasion. English had the French come up from the south, repeated Viking incursions from all around the coast. They all had an impact on the language. I find it really interesting. Icelanders are really proud of how conservative the language is and that they still can read these older stories. I think in some ways English has created this story for itself where it’s really proud of the fact that it is this language that continues to take influences from places and is really innovative. These are just part of the story that a language can tell about itself and the speakers can tell about it.

Gretchen: I think that there are reasons to be proud of any language that don’t have to rely on age as the sole arbiter of legitimacy. In some cases, it’s that rupture with the past that people use as a point of pride. I’m thinking of Haitian Creole, for example, which is descended from French. You can hear that French influence. When I’ve heard people speaking Haitian Creole, it almost sounds like they’re speaking a French dialect that I don’t quite know. But the writing system is very different. It’s much more phonetic than French is. The word for “me” in Haitian Creole is “mwa,” and it’s written M-W-A. The word for “me” in Modern French is “moi,” pronounced the same way but written M-O-I.

Lauren: Right.

Gretchen: It used to be pronounced /moɪ/. This is why you get “roy” and /ʁwa/ for “king” and stuff like this, hence the spelling. But the sound changes happened in French. When the Haitian speakers were deciding how to write their language down, they were like, “No, we’re gonna have a phonetic system. We don’t need to be beholden to the French system. We’re gonna have something that establishes our identity as something that’s distinct from French.”

Lauren: For anyone who’s tried to learn the French spelling, especially those endings that are still in the writing system but not in the pronunciation system, I think it’s fair to say French has gone through a number of sound innovations, even if it might be more conservative in other features of the grammar.

Gretchen: It’s very conservative in the writing system, but the sounds have changed a lot.

Lauren: It’s interesting you bring up Haitian Creole because creoles are the result of this intense contact between two or more languages. They often get labelled as being “new,” which is kind of the flip side of this discourse around “old” languages.

Gretchen: That’s controversial in linguistics whether to consider creoles “new” or to consider them older. What they definitely have is children being raised by people who also already had some amount of language. Babies can’t raise themselves. But they do have this situation where their speakers were prevented from learning how to read and write, learning how to access the formal varieties of language, often very violently and through horrible circumstances. A lot of creoles came about because of the slave trade, because of historical systems of oppression. The language transmission was not the same as if you were learning it from parents who’d been educated in the language, but they were still learning from people who had access to the language. There’s been a bit of a swing in creole studies more recently to say, “What if we don’t consider these completely new? What if we think about the ancestral features that they have in common with the languages they’re descended from?” which you can readily trace as well.

Lauren: Thinking in terms of which features are innovative rather than the whole language as being new. Maybe it has a very innovative way of doing the noun structure, but it still has a lot of the features of the two different – or multiple different – languages in terms of sounds, and so taking apart the different linguistic elements and not just focusing on the whole thing as being “new” or “old” and trying to apply these labels that don’t actually account for what’s happening.

Gretchen: It can be kind of exoticising to creoles to say, “Oh, these are completely different from all of the other ways that languages have gotten transmitted,” when what’s also going on is kids in a community who were exposed to a bunch of languages or a bunch of different linguistic inputs at a time making sense of that and coming up with, collaboratively, something with the other kids in the community that is different from what people were speaking before but still has that ancestral link.

Lauren: There are contexts in which children are raised without that access to language transmission. That is when a d/Deaf child is born into a hearing and spoken language family context, which means that they’re not getting that language.

Gretchen: Generally, the child and the parents and the family and community members do end up with some amount of ways of communicating based on the existing gestures that people do alongside a spoken language and elaborating on them, making them more complex, because you are trying to communicate somehow. There are linguistic studies about this, right?

Lauren: Ideally, in an ideal world, if you’re a d/Deaf child, you would want to have access to signed language input through, ideally, your family but also your wider educational context. Some d/Deaf children do get hearing aids. They are useful but not a perfect replication of the hearing child experience. That’s a possibility. There are some contexts where children have just developed this communication system with their hearing family in their own home context. These are known as “home sign.” There have been examples of this, and they have been studied. One of the most famous examples that has been described in a lot of detail is the example of David and his family. Susan Goldin-Meadow and her collaborators over the years have done a lot of work looking at the way David and, especially, his mother communicate with each other.

Gretchen: This is a really tough situation. I think these studies started in the early ’90s. Hopefully, people know better now and can give their d/Deaf kids access to a sign language, but given that this happened, what can we learn from the situation?

Lauren: Goldin-Meadow definitely started publishing about this in the early ’80s. So, David – who I will forever think of as a 7-to-10-year-old child – is actually a GenX-er who, if he had kids himself, they’re undergraduates now.

Gretchen: Okay. It’s good to put famous children from studies in perspective.

Lauren: Because they are – it’s like the Shirley Temple phenomenon, right. David, in my mind, is always just this kid who’s learning to communicate with his mom, but he’s a fully-grown, tax-paying adult now.

Gretchen: What was he doing when he was communicating with his mom in this immortalised-in-amber childhood years?

Lauren: What was really interesting from a thinking-about-this-human-capacity-for-language-and-communication perspective is that his mother and the family developed this way of communicating with him that grew out of their typical gestures and context and a lot of showing each other stuff.

Gretchen: Pointing to things and so on.

Lauren: Pointing – so useful in all languages and all contexts. What they found was that David was creating systematic order out of the gestures that he was getting. So, he had more systematic structure in terms of the hand shape that he was using – he created these hand shape structures and these individual signs that his mom would also use but not as consistently as him. It’s actually the child taking this really idiosyncratic, raw gesture material from his mom. Gestures in spoken language context tend to be a bit more freeform and unstructured than, say, something like a signed language, which uses the same hands but in a very different way. He wasn’t doing something that was a fully structured language, but it had more structure than what he was being given.

Gretchen: His brain was really starved for linguistic input, and he was trying to extract as many linguistic vitamins and minerals as he could from this incomplete gestural system that he was being given as the closest approximation of language. Obviously, we do wish that David, who was raised in the US I think –

Lauren: I think.

Gretchen: – had just been given access to ASL, which lots of people already were using in the US and could’ve happened where he would’ve gotten the fully-fledged, healthy balanced diet of lots of linguistic input from lots of people, but the child brain seems to want to reconstruct language out of whatever is available to it.

Lauren: This type of system, which is often called “home sign,” is not the same as a fully-fledged sign language. Children often don’t have the same level of linguistic structure. They obviously can’t communicate with people outside of the home context who don’t know the signs that they’ve created with the family. I think it’s also worth pointing out that it is more structured than you would expect it to be from the input. We’ve seen when you take children from these emerging structures, and you bring enough d/Deaf people together, you actually get a real blossoming of a full linguistic system.

Gretchen: The most famous example of this is in Nicaragua in the 1980s, where a bunch of d/Deaf children were brought together at a school for the first time. The school wasn’t trying to teach them a signed language; they were trying to do an oralist method of education, which is [grumbles] – about which the less said, the better – but the kids themselves were coming in with their home sign systems and developing them further in contact with each other. When the next generation of kids showed up, and they had access to this combined home sign system, they really turned it into a full-fledged sign language, which is now – Nicaraguan Sign Language is the national sign language in Nicaragua. These types of languages are some good candidates for “youngest” language, even if we don’t know what the “oldest” language looked like.

Lauren: The amazing thing about Nicaraguan Sign Language is there were linguists on the ground pretty much from the beginning of the school in 1980s. There is a documentation of how this language has evolved. It was the older signers coming in, communicating with the younger children coming to the school, who then created more of the structure – so being a bit like David but in this really rich communicative and linguistic environment and building this structure into the language.

Gretchen: It seems to take those two generations of linguistic input. That feels very reassuring to me which is that language is so robust that even if we lose all of our writing systems, and we lose all of our memory of writing systems, and we lose access to the memory of what language looks – like, suddenly we all wake up with amnesia or something – we would rediscover this. Even though they wouldn’t be the same languages, we’d put something back together and still be able to talk to each other.

Lauren: We know this because Nicaraguan Sign Language is not the only example we have of a recently developed language that has emerged. The Nicaraguan Sign Language is a school-based sign, but we also have what are known as “village-based” sign systems, which is where there might be a d/Deaf family, or a number of d/Deaf families in the village – or a very high percentage of d/Deaf population – and a sign language emerges that the whole village, d/Deaf and hearing, use to communicate. It’s usually “village” because it is these smaller communities where people gather and live together and have to communicate with each other all the time.

Gretchen: And if you have an island or somewhere in the mountains or somewhere were there’s a high degree of genetic d/Deafness because there’s a relatively high degree of isolation, you can have a third of the village be d/Deaf, in which case, everybody in that village is learning signs from each other at a young age. I think the famous example of that that I’ve heard of relatively nearby is Martha’s Vineyard in the US, which is an island, I think. It has a village sign language.

Lauren: Lynn Hou talked about Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language in the interview she did with us, which is in a tribal group in a desert in southern Israel.

Gretchen: There’s also Kata Kolok, which is also know as Benkala Sign Language or Balinese Sign Language, which is a village sign language indigenous to two neighbouring villages in northern Bali, Indonesia. Similar situations there.

Lauren: We see this robustness of language and these “young” languages but building on this underlying human tendency to want to create linguistic structure when you bring enough people who can communicate together.

Gretchen: A really interesting example that I’ve encountered recently of what it’s like to suddenly have at least access in terms of format or modality to language, even if you don’t know what everything means yet, is in the book True Biz by Sara Novic, which is set at a school for the d/Deaf. One of the main characters is a d/Deaf girl whose cochlear implants have been malfunctioning, and so she hasn’t been raised with access to a sign language, but suddenly, she’s in this school now and is learning ASL and trying to get her cochlear implants to still work but, in the meantime, is suddenly immersed in this environment where she has full access to language instead of this piecemeal access via attempting to lip read or attempting to use these implants that haven’t been working very well for her. The author is d/Deaf and talks about a variety of different types of experiences that people can have in that context.

Lauren: I really appreciated how this book made the most of the written format to occasionally just not give you what another character was saying, and so you get this experience of being the young protagonist in the book suddenly like, “I’m only getting half of this sentence. I don’t know what’s happening. It’s very stressful.”

Gretchen: Because there’s just a bunch of blank spaces. There were also some places where there were drawings of words that were being talked about or worksheets that she was seeing with line diagrams of different signs. Despite the fact that it’s a book that’s in written English trying to convey ASL, which is not English and doesn’t have a standard way of being written, I think it’s doing a really interesting job of trying to convey that experience.

Lauren: That lack of writing system for signed languages means that a lot of the history of signing in human language history has been lost to us. There have been different signing communities at different times in history. It’s probably been a very common way of humans doing language, but we just don’t know because it’s not in the streetlight of the written record.

Gretchen: Right. We don’t even know if the first language – the “oldest” language – was a spoken language or a signed language. People have come up with arguments for both things. We just don’t know.

Lauren: Which in some ways I find very relaxing instead of constantly trying to make cases for which language is the “oldest” or which is the “newest,” you can just let go of those debates because they are all, at the end of the day, unproveable. You can just enjoy the variety of human language without it being a competition.

Gretchen: A language doesn’t have to be the oldest language or even the newest language in order to be cool. Languages are great. All languages are interesting and valid, and people should have the right to have access to them when they want them. By listening to this episode, you’re participating in part of that chain of human language transmission that stretches beyond anyone’s written record or recorded record or video record. You’re still part of it.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on all the podcast platforms or at lingthusiasm.com. You can get transcripts of every episode at lingthusiasm.com/transcripts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on all of the social media sites. You can get scarves with lots of linguistics patterns on them including IPA symbols, branching tree diagrams, bouba and kiki, and our favourite esoteric Unicode symbols, plus other Lingthusiasm merch – like our new “Etymology isn’t Destiny” t-shirts and aesthetic IPA posters – at lingthusiasm.com/merch. Links to my social media can be found at gretchenmcculloch.com. I blog as AllThingsLinguistic.com. My book about internet language is called Because Internet.

Lauren: My social media and blog is Superlinguo. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk to other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus topics include fun interview excerpts, an interview about swearing with Jo Walton and Ada Palmer, and our very special linguistics advice episode where you asked questions, and we answered them. If you can’t afford to pledge, that’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Gretchen: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Lauren: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#language#linguistics#lingthusiasm#episodes#podcast#transcripts#podcasts#language history#Olmec Bark#cuneiform#writing systems#sign language#home sign

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arika Okrent: Highly Irregular: Why Tough, Through, and Dough Don't Rhyme and Other Oddities of the English Language (2021)

#akira okrent#sean oneill#highly irregular#english#language history#grammar#linguistics#oxford university press

6 notes

·

View notes