#like any genre the book is shaped by the author's lens

Text

That C.S. Lewis quote about being "old enough for fairy tales again" is really popular in this section of tumblr, but I think I've hit an opposite stage where I'm old enough for realism again. As a teenager in English class, realism seemed like the boring, baseline option that limited your imagination to only the dullest parts of daily life. If I wanted real life, I'd just live it! Stories should give us something bigger and brighter and more exciting!

But as I get older, I'm starting to understand that realism isn't about limiting yourself to the real world, it's about appreciating it. It's about noticing and caring about those tiny details in life. It's about looking at the seemingly ordinary and unexciting people and saying that their stories are worth telling, too. There's a beauty in gazing upon this world in delicate detail and drawing out those fine shades of nuance that you don't notice in the bustle of actually living life. Realism lets you slow down and recognize that our world has wonders, too, and they don't all have to be big and flashy to be worth our attention.

Younger me also got the impression that realism was depressing--we don't get happy endings because they're not realistic. And it's true that realism has a greater share of sad endings, but that can be a comfort. As you grow up, you have more and more experiences tell you that the happiness of life is buried in a lot of murkier emotions--a lot of turmoil and uncertainty and bad decisions--and realism says that's okay. The story's worth telling even if it doesn't end well, even if people don't rise above their baser natures, even if things are a bit dull. Realism can be happier, in some ways, than those bigger, brighter genre stories, because it acknowledges those murkier imperfections of life and says that they don't erase happiness or make someone's story not worth telling.

Lewis' quote is great, but it's not the whole story. Like Chesterton says, children are fascinated by fairy tales, but the youngest children are fascinated by reality--"A child of seven is excited to hear that Tommy opened a door and found a dragon, while a child of three is excited to hear that Tommy opened a door." Fantasy is a fantastic escape, but like all travel, the point of it is to make us see our own world more clearly when we return home. And that's where realism comes in. Those types of stories aren't about casting off childish fancy and focusing on the grim details of adulthood--they can be about regaining an even more innocent and child-like wonder.

#books#i've been building this thought ever since i started really getting into gaskell#she's the one who opened my eyes to the beautiful compassion of realism#like any genre the book is shaped by the author's lens#there can be very ugly realism but she showed me that it doesn't have to be#reading henry james helped solidify these thoughts#and i think i'm firmly in my realism phase now#i've got a couple of trollope books to try over lent#and i'm very excited about it#when i would not have been only a few years ago#i've matured to the place where i can enjoy long boring detailed stories and i'm very excited about this development

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you've seen part of this response before, that is because I'm taking my comments from another post about how you can use a queer lens to interpret the symbolic implications of how Artemis' coming of age adheres (or doesn't adhere, rather) to typical children's lit protagonist arcs.

Specifically, I want to use this post to talk about the genre trend in YA of having the main child/teen character (i.e., the character with whom the presumed teen reading demographic is identifying) end their series having "successfully" become a "normal", heterosexual adult by getting married and having children (which also opens up the possibility of a sequel series, lol). An iconic example would be how the HP epilogue and post-canon canon material outline the minutiae of what former-protags from the original series are now grown up and heterosexually married to what other former-protags; the epilogue materials for HP also mention the children that have resulted from these (exclusively) heterosexual canonical marriages.

Also, if it seems like my wording is repetitive, that is because I want to be precise lol! The subjects I'm treating here are the legally- and socially-diffused power structures that work to render heterosexuality the "norm" at the expense of other sexualities (even heterosexuals suffer under this system, as patriarchy further complicates things here). It would be biphobic, not to mention not grounded in material analyses of power and sexuality, to imply that bi people who are in different gender romantic relationships are "reifying norms of heterosexuality".

With that established, there's a lot of interesting scholarship on how children's lit and YA can function in part to outline what characteristics define a "normal" transition into becoming an adult in the particular society a text exists within. Fiction is a safe space to explore possibility, and if you can delimit what possibilities are possible, then that is an important part of shaping what possibilities are explored socially.

Thus, when we talk about the aforementioned genre convention of having the protagonists of YA series end those series by getting heterosexually married and then having kids, we're not talking about any individual narrative about characters that just so happen to grow up to be heterosexual adults.

Rather, we're talking about the way experiences become solidified as cultural "norms" through complex trends in fiction -- and that is NOT a result of authors intentionally, nefariously going "haha, and today I will use my fictional story to convince my readers that heterosexuality is the only possible sexuality one can have". That is a facile understanding of how norms are culturally produced, not to mention a misunderstanding of the way that the "normalcy" of heterosexuality is internalized through encounters with fiction.

But to return to my point about applying a queer lens to analyze the coming-of-age story in the books, there's this moment in TLC that is so interesting to unpack.

First off, you have to look at how parts of the series function as a metaphor for the struggles of coming of age.

In the above scene that I attached from TLC, you have Butler, an important older male figure in Artemis' life and one of the central adult characters of the series, stating that Artemis being "distracted by girls" is something both "normal" and "natural" that was deferred by Artemis' adventures with the fae. Furthermore, in the first book, Artemis mentions that he was able to discover the People because he occupies a liminal space between the adult world and the child world. Here, when I emphasize a refusal by Artemis to fully enter the "normal" adult world that Butler identifies as being tied to the experience of having one's first heterosexual crush, that isn't me saying that queerness/non-straightness is "childish". Rather, by the (unjust) standards of homophobic power structures that influence our society, for one to enter the adult world — for one to be accepted as a normal adult — one must assimilate into normative heterosexuality. And that very assimilation into heterosexual adulthood is something that Artemis' adventures (adventures that are made possible by him rejecting that world of "normal" adulthood!) have "distracted" him from pursuing.

I think one can interpret there being a hidden queer reading of Artemis "being distracted" from "normal" feelings that he should have been experiencing due to focusing his attention on these adventures. Symbolically, I know that I can draw parallels during my adolescence of avoiding confronting — or rather, preventing myself from feeling — my attraction to women by throwing myself into academics, which was a way to avoid questions from people in my life about why I wasn't dating like my peers were.

I want to transition to my next point with this scene: "Control puberty? [...] If you do, you'll be the first". Technically, Artemis accomplishes that in this book!

When he goes to the pocket dimension of Hybras, Artemis experiences the passing of a few hours, yet when he returns to earth, three years have gone by. Ergo, he is only fifteen years old — making him still a child — yet legally, he is eighteen due to the missing three years, providing him access to the world of adults without having to experience the aforementioned puberty that comes with aging the normal way instead of hopping around in time.

All of this is with just one scene. Honestly, the books are conducive to a bunch of different readings, and I think that one could apply a queer lens to produce readings of the series in which Artemis is gay, bisexual, asexual/aromantic, transmasculine, nonbinary, and/or what have you, using so many other moments from the series.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Response 1: The Danger of a Single Story

The stories we read, hear, and tell shape our view of the world and our view of those around us. In her 2009 Ted Talk, The Danger of a Single Story, Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie reflects upon the power of stories and the consequences of the “single story.” She says a single story is created when you “show a people as one thing... over and over again, and that is what they become,” (Adichie 2009). Ultimately, Adichie argues that when single stories are created, they provide incomplete narratives which rob people and places of their own dignity and power. Additionally, these single stories reduce people to stereotypes and emphasize difference among groups of people. Reflecting on Adichie’s TED Talk, I have come to realize that the stories I heard and was told growing up were extremely narrow in scope. They were dominated by a westernized lens and laced with ideas of heteronormativity and “normative” identities.

From a young age, I was never much of a reader. I was reading by the time I reached 2nd grade, but my memory of how I got to that point is foggy. Growing up with some sort of undiagnosed learning disorder, reading and comprehending the text in front of me did not come easy. I remember having trouble recognizing how words pieced together to form sentences, and how sentences flowed together to create stories. For a lot of my childhood, I relied on my father, my sisters, or my teachers throughout elementary school to choose stories for me. I remember being read a variety of picture books; Angelina Ballerina was my favorite.

Like Adichie, I was heavily influenced by American literature during my younger years. I delved into the fantasy world of Harry Potter and was enchanted by the countless adventures of Jack and Annie from the Magic Treehouse series. The literature I consumed altered the way I thought about the world and made me believe that magic was real. In her TED Talk, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie recounted how reading about white, westernized stories influenced the way that she wrote her own stories. It wasn’t until she began to read stories from African authors that she believed someone with the color of her skin could be in literature. Similarly, American literature I read from a young age made me believe that stories would always center around white folks like myself and characterized any other narrative as an “other.”

As I began to read more throughout middle and high school, young adult romance quickly became my favorite genre. During this time, I began to come to terms with my sexuality. I labeled myself as bisexual, even though I now identify as a lesbian. Though most of the books I read were still very westernized and centered around white characters, I felt left out from the romance novels I was reading, just like I felt left out from the heteronormative world. My favorite book I read during my high school years was Every Last Word by Tamara Ireland Stone. I loved that the book represented mental health. I loved that I could relate to the main character’s internal conflicts with her OCD diagnosis. However, a piece of me was still missing from this book and every single other book I read.

Heteronormativity dominated the literature that I was exposed to during early childhood, in schools, and in my very conservative hometown. I was never exposed to any queer romance in the stories I heard or was told, and I experienced a lot of compulsory heterosexuality as a result. I believed that if I did not see my sexual orientation being represented in YA novels, that my identity wasn’t valid or worth talking about. Because of the literature I was exposed to, I thought I had to experience at least some attraction to cisgender men. I truly believe that I came out as a lesbian so late in life because the stories I heard about romance were reduced to a single story, a heterosexual story.

In her TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie ends with a beautiful quote: “when we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise,” (Adichie 2009). I believe that when we reject a single story, we open the world and create a space where everyone feels a sense of belonging. When we reject a single story, we begin to understand those around us and how we as individuals fit into the world. When we reject a single story, we reject the misinformation we have gathered from that narrow scope of knowledge. After reflecting on this piece and my own experiences I wonder, how do we begin to undo all the single stories that literature, the media, oppressors, and systems/structures have created?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck

Title: The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck

Author: Mark Manson

Genre: Nonfiction

Date Published: September 13, 2016

Rating: 2.5 / 5

Overview:

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck is a self-help book that basically tells us to reflect on our life and filter the important ones from the unimportant and choose what and where to give a f*ck because our f*cks are limited (to choose our struggle and to only choose what matters). This book is emphasizing that problems are constant in life – it never stops and it’s fine not to be positive all the time. Pain, rejections, and failures will always be part of the process of living a good and better life.

Remarks: I am a wrong audience of this book.

This book is overly hyped and has constantly heard of its reputation since then, it did piqued my curiosity and interest and for no absolute reason it was only this time did I pick up this book. When I started reading I thought it was brilliantly written, the writing style is unique maybe because the author is mainly a blogger (it feels like I am reading a long long blog). The first paragraph is a hook! Yet just like any other books, readers may find some flaws and gets disengaged as we flipped through the pages, and when I get to the middle part, there are certain narratives of his that I disagree with mainly because the book is too practically universal nothing new and subjective that it made me lose interest, his narrative is generally speaking from his lens centered and generalized from his own experiences (some of them is not applicable to others) and readers in my bracket have mostly learned the lessons he imparted from this book hence I did say that I am a wrong audience. Heard that this has mixed reviews, went on to read some of them and unsurprisingly we have the same thoughts among those reviewers.

I do think that the book is essentially catered and more suitable towards millennials and Gen Z’s who are yet to discover the other side of life and needs guidance, or any person who is still starting to open up their eyes to the difficulties of life and still on the earliest stage of conquering and solving life problems, the book is pretty basic actually with minute substance. When I get to the end part of the book, it did hooked me up once again.

Personally, what I absolutely like about this book is that the author imparts other interesting real-life stories that are inspiring including his, I always love the part where he talks about his own experiences and how they shaped him to be who he is today. It was a great read, I was about to put it down in the middle of my reading but decided to finish it which I did not regret at all.

Favorite Part and Favorite Key Takeaway:

Improvement at anything is based on thousands of tiny failures, and the magnitude of your success is based on how many times you’ve failed at something. This made me realize that if a person is good at something than you, chances are that, that person probably failed many times than you have.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rise of Dystopian Literature: Why We Are Drawn to Stories of Dark and Disturbing Futures

Outline:

I. Introduction

- Definition of Dystopian Literature

- The Growing Popularity of Dystopian Themes

II. Historical Roots of Dystopian Literature

- Early Examples and Influences

- Evolution of Dystopian Narratives

III. Characteristics of Dystopian Novels

- Common Themes and Elements

- Exploration of Societal Issues

IV. Impact of Dystopian Literature

- Shaping Cultural and Social Discourse

- Influence on Popular Culture and Media

V. Influential Dystopian Novels

- 1984 by George Orwell

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

- The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

- The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood

VI. Themes Explored in Dystopian Literature

- Surveillance and Loss of Privacy

- Totalitarian Governments

- Struggle for Individuality and Freedom

VII. The Allure of Dark and Disturbing Futures

- Human Fascination with Worst-Case Scenarios

- Reflection of Contemporary Fears and Anxieties

VIII. Dystopian Literature in Modern Education

- Inclusion in School Curriculums

- Encouraging Critical Thinking

IX. Dystopian Literature vs. Reality

- Parallels with Contemporary Issues

- Warning Signs and Societal Reflection

X. The Role of Technology in Dystopian Narratives

- Surveillance Technology in Literature

- Real-World Implications

XI. The Power of Dystopian Imagination

- Inspiring Change and Activism

- Catalyst for Social Awareness

XII. Criticisms and Controversies Surrounding Dystopian Literature

- Accusations of Dystopian Fatigue

- Ethical Concerns Regarding Graphic Content

XIII. Conclusion

- Recap of Dystopian Literature's Impact

- Continuous Relevance and Future Prospects

XIV. FAQs (Five Unique Questions)

- Is dystopian literature suitable for all age groups?

- How does dystopian literature differ from other speculative fiction genres?

- Can dystopian novels serve as a form of social commentary?

- Are there any emerging trends in contemporary dystopian literature?

- What makes dystopian literature a powerful tool for discussing societal issues?

The Rise of Dystopian Literature: Why We Are Drawn to Stories of Dark and Disturbing Futures

Introduction

Dystopian literature, characterized by nightmarish visions of the future, has witnessed a significant surge in popularity in recent years. This genre explores unsettling societal structures, oppressive governments, and the human struggle for survival. As we delve into the rise of dystopian literature, it's essential to understand the roots of this captivating genre and its enduring impact on readers.

Historical Roots of Dystopian Literature

Dystopian narratives have historical roots, with early examples found in works like "The Time Machine" by H.G. Wells. Over time, dystopian literature evolved, with authors weaving intricate tales that reflected contemporary fears and anxieties. The genre became a powerful medium to comment on societal issues, offering both cautionary tales and imaginative escapes.

Characteristics of Dystopian Novels

Dystopian literature shares common themes such as totalitarian regimes, loss of individual freedoms, and surveillance. These novels often serve as a lens through which readers can examine and critique societal norms. The exploration of dystopian worlds allows for a deeper understanding of the human condition and the consequences of unchecked power.

Impact of Dystopian Literature

Beyond entertainment, dystopian literature shapes cultural and social discourse. Influencing popular culture, movies, and television, dystopian narratives often transcend the pages of books, impacting how we perceive and navigate our own world. This influence extends to education, where dystopian novels are integrated into curriculums to provoke critical thinking.

Influential Dystopian Novels

Certain dystopian novels have left an indelible mark on literature and society. George Orwell's "1984," Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World," Suzanne Collins' "The Hunger Games," and Margaret Atwood's "The Handmaid's Tale" stand out as pillars of the genre, each exploring unique facets of dystopian themes.

Themes Explored in Dystopian Literature

Dystopian literature delves into recurring themes like surveillance, totalitarian governments, and the struggle for individuality. These themes resonate because they reflect genuine societal concerns, making dystopian narratives relatable and thought-provoking.

The Allure of Dark and Disturbing Futures

Readers are drawn to dystopian literature because it offers a glimpse into worst-case scenarios. The genre taps into human fascination with disaster, providing a space to explore fears and anxieties in a controlled setting. By examining these dark futures, readers can confront and, to some extent, prepare for potential challenges.

Dystopian Literature in Modern Education

The inclusion of dystopian literature in school curriculums enhances education by encouraging critical thinking. Students analyze complex societal structures, question authority, and draw parallels between dystopian narratives and real-world issues, fostering a deeper understanding of the complexities of human society.

Dystopian Literature vs. Reality

Dystopian literature often mirrors contemporary issues, acting as a warning sign for potential societal pitfalls. The genre prompts readers to reflect on the present, recognizing parallels between fictional dystopias and real-world challenges. This connection fosters awareness and, in some cases, inspires action.

The Role of Technology in Dystopian Narratives

Advancements in technology have become integral to dystopian narratives, with surveillance and loss of privacy playing central roles. Dystopian authors explore the implications of technology on society, offering insights into potential future scenarios that resonate with our current dependence on digital surveillance.

The Power of Dystopian Imagination

Dystopian literature goes beyond entertainment; it inspires change and activism. By presenting alternative futures, authors challenge readers to question societal norms, fostering a sense of agency to shape a better world. Dystopian imagination becomes a catalyst for social awareness and, potentially, positive transformation.

Criticisms and Controversies Surrounding Dystopian Literature

Despite its influence, dystopian literature faces criticisms, including accusations of dystopian fatigue and concerns about graphic content. Some argue that the genre's prevalence may desensitize readers to its warnings. Ethical considerations regarding the portrayal of violence and distressing scenarios also spark debates within literary circles.

books that changed my life

Embarking on a literary journey is not merely an act of reading; it's a transformative odyssey that has the power to shape our perspectives, challenge beliefs, and leave an indelible mark on our souls. As I reflect on the books that changed my life, I find myself immersed in a kaleidoscope of narratives that have altered the course of my understanding and enriched the tapestry of my experiences.

One such life-altering encounter was with Viktor Frankl's "Man's Search for Meaning." This profound exploration of human resilience, drawn from Frankl's experiences in Nazi concentration camps, instilled in me a newfound appreciation for the strength of the human spirit and the pursuit of purpose even in the face of unimaginable adversity.

Haruki Murakami's "Norwegian Wood" served as a poignant companion during moments of introspection. Its exploration of love, loss, and the delicate threads that connect us all resonated with the nuanced emotions I grappled with, offering solace and a deeper understanding of the human condition.

The philosophical musings of Hermann Hesse in "Siddhartha" guided me on a quest for self-discovery and spiritual enlightenment. The protagonist's journey echoed my own quest for meaning and purpose, prompting moments of introspection that reverberated long after the final page.

"1984" by George Orwell, a dystopian masterpiece, acted as a stark warning about the perils of unchecked power and the erosion of individual freedoms. Its chilling portrayal of a totalitarian regime left an indelible imprint, fostering a vigilant awareness of societal structures and the importance of safeguarding liberty.

Each book, a literary gem, has left an enduring legacy on my consciousness, shaping my thoughts, values, and understanding of the world. The transformative power of literature lies not just in the words on the page but in the profound impact it has on the reader's journey through life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the rise of dystopian literature is not merely a trend but a reflection of our collective fascination with exploring the unknown, challenging societal norms, and contemplating the consequences of unchecked power. The enduring appeal of dystopian narratives lies in their ability to provoke thought, inspire change, and serve as cautionary tales for the complex world we inhabit.

FAQs (Five Unique Questions)

What are the 5 traits of dystopian literature?

Dystopian literature manifests through vivid characteristics that paint a bleak picture of the future. Typically, these traits include oppressive government control, societal dehumanization, environmental degradation, surveillance, and the suppression of individual freedoms. These elements collectively create a nightmarish vision of a world gone astray.

What is the most famous dystopian text ever written?

Undoubtedly, George Orwell's "1984" stands as the epitome of dystopian literature. Published in 1949, Orwell's masterpiece envisions a totalitarian regime, Big Brother's omnipresent surveillance, and the manipulation of truth, leaving an indelible mark on the genre and society's collective consciousness.

What describes dystopian?

Dystopian, derived from the Greek words "dys," meaning bad, and "topos," meaning place, encapsulates an imagined society characterized by oppressive social, political, and environmental conditions. These bleak settings often serve as cautionary tales, exploring the consequences of unchecked power and societal complacency.

What are the 4 types of dystopias?

Dystopias come in various shades, with common types being totalitarian, corporate, ecological, and technocratic. Totalitarian dystopias feature oppressive governments, corporate dystopias showcase unchecked corporate power, ecological dystopias depict environmental collapse, and technocratic dystopias explore the dark side of technological advancement.

What is a book that has changed society?

Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin" is a pivotal work that significantly altered societal perspectives. Published in 1852, this anti-slavery novel ignited fervent discussions, heightened awareness of the horrors of slavery, and played a substantial role in galvanizing the abolitionist movement.

How has literature changed the world?

Literature acts as a mirror and catalyst for societal change. It sparks critical conversations, challenges norms, and fosters empathy. Books like "To Kill a Mockingbird" by Harper Lee and "The Diary of Anne Frank" have influenced public discourse, fostering social awareness and advocating for justice.

What is the most influential book in American history?

"The Federalist Papers," a collection of essays by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, profoundly influenced American history. Penned in the late 18th century, these essays played a crucial role in shaping the U.S. Constitution, providing insights into the framers' intentions and political philosophy.

Which book is the most powerful book in the world?

"The Bible" is widely considered one of the most powerful and influential books globally. Its impact transcends religious boundaries, shaping cultural, ethical, and literary landscapes. Its narratives and teachings have left an enduring imprint on human history and continue to inspire countless individuals worldwide.

Read the full article

#6elementsofdystopianfiction#Booksthatchangedtheworldofliteraturepdf#booksthatchangedtheworldpdf#dystopianliteratureanalysis#Dystopianliteratureauthors#Dystopianliteraturebooks#Dystopianliteraturecharacteristics#dystopianliteratureexamples#dystopianliteratureineducation#Dystopianliteraturepdf#Dystopianliteraturesummary#dystopianliteraturevs.utopianliterature#dystopiannovelsforyoungadults#dystopianthemesandsymbolism#emergingdystopianauthors#exploringdarkfuturesinliterature#Famousdystopianliterature#Fictionbooksthatchangedtheworldofliterature#futuristicdystopiannovels#impactofdystopiannarratives#mostinfluentialbooksofalltime#mostinfluentialbooksofthe21stcentury#societalcritiqueindystopianfiction#thebookthatchangedtheworld#top10mostinfluentialbooksintheworld

0 notes

Note

After the release of midnight sun we need to support other vampire books by people of color or authors who aren’t racist or Mormon ig

so to answer this ask i found myself turning to Lesbrary bc it was the easiest way i knew to find diverse stories with diverse authors, so this rec list is Bi and Lesbian Literature! with a link to the review on Lesbrary’s site. I haven’t read any of these books (yet!), but hopefully this sheds some light on some amazing stories that can fill that vampire void in our hearts.

This is slightly off topic, but if Carmilla appeals to you, you might be interested in this! Its a new look at The Lesbian Vampire Story through a queer lens. Lesbrary’s review says more than i could, but if you wanted more from carmilla go check it out! This Edition was edited and introduced by Carmen Maria Machado.

The next book i have to recommend to you is Fledgling by Octavia Butler. The protagonist of this one is a black vampire named Shuri, and she’s completely lost her memory, slowly relearning what her brain injury took from her and building up her life from scratch. It sounds very good, so check out this lesbrary review here for a better look!

Here’s a compilation of Black lesbian (and bi, queer, trans, and non-binary) fiction authors you should know.

Here is a selection of ten great Gothic works with sapphic characters to get you started with the genre…

so i know this wasnt exactly what was asked of me, but i think the twilight fandom would love a wlw oriented direction to point themselves in via literature, especially vampire/supernatural/gothic. Not all of the authors mentioned here are POC, but i think that queer stories are also appealing to people seeing this post, and others in the fandom.

BUT as a bonus, here’s so more Diverse Vampire Fiction

(goodreads) Vampire Books by POC

(https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/133571.Vampire_Books_by_POC)

An Article from https://www.diversereading.com/ on Fiction With Black Vampires

(https://www.diversereading.com/fiction-with-black-vampires/)

also please check out the website as a whole to diversify your reading experience

Here’s 7 Wonderfully Diverse Vampire Novels

Those are the links I have for you today folks! Happy reading! I hope you enjoy this collection of books and I hope it fills the vampire shaped hole in your heart!

Because I would like these authors to get more visibility I’m tagging @rose-lily-hale and @bellasredchevy

I really hope that the fandom starts getting into more diverse vampire literature, and this ask was such a great opportunity to showcase some amazing authors that deserve the spotlight! Please feel free to add on your favorite books/authors!

#twilight#vampire fiction#riley to the anon#diverse fiction#hey so im drunk putting this together#shfdkjlsdg#but this was fun to put together! I cant wait to read some of these books!!!!#anyways thanks for this ask bc it was the perfect chance to spotlight these authors!#i hope we as a fandom keep pushing better authors to fill that vampire fic#fix

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valaks

So I’ve broken my own rule about not letting these things get too long, but this author deserves it. Full disclosure: this rec had help from two friends because they simply couldn’t resist piling in on this post.

Valaks is a popular author in the fandom for good reason. It’s not only the originality of the ideas and high quality writing that does it, but the sheer breadth of what’s on offer. Seriously, this author does it all. Nearly all genres are covered - fluff, crack, full AU, hurt/comfort, mission fics, angst and more. The range of characters explored is staggering too, with fics covering the usual suspects - Alex, Yassen, Tom, Ben Daniels, K Unit - but also more minor characters, like John Rider, Nile and Ms Bedfordshire. We are not exaggerating. There’s something for everyone here.

https://archiveofourown.org/users/Valaks/pseuds/Valaks

We had a really hard time picking out our favorites, and would definitely recommend you just head over to AO3 and check out their whole catalogue. But here are five fics that stand out particularly well within their individual genres.

Ruthless: A one-shot set in pongnosis’s Devil!verse that explores how far Alex is willing to go when it’s Yassen’s fate on the line. We’re all fans of the relationship built up by pongnosis between Alex and Yassen, and this story is so realistic and close to the original’s tone and characterizations it feels like you could be reading a sequel/outtake from it. The gradual build of tension in this fic, from Alex’s first prickles of uneasiness to the climax and then the resolution, is masterful. And there’s so much grit and realism - definitely no shying away from the realities of working for a terrorist organization. We adored the whole thing.

Alibi: Alibi is a story examining the other side of Alex’s life: his time in school and the relationships with people outside the immediate scope of MI6, specifically Tom and Jack. This story pulls into sharp focus the impact that a year in the the shadier sides of life have not only on Alex, but the impression of him held by those closest to him. What’s more, Alibi is a wonderful look at Alex Rider through a very contemporary lens in 2020: classes held via Zoom, the ever-present reach of technology and how relationships function online. For a book series with a loose sense of the ‘present’ that updates with each publication, seeing an author tackle some of the singular challenges of the current year was a personal delight for us.

In Loving Memory: This is described in the summary as “How could the Organ Hospital get any worse”, and that about sums up the angst level of this fic. It’s brutal. But so beautifully written. The story explores the concept of memory orbs - orbs that show the individual memories of a person from whom they have been extracted - and what would happen if Yassen came across one of Alex’s. It is a wonderfully original premise, and executed with flair. Valaks is often described as an “angst author” and, whilst we consider this to be an unfair characterization given the aforementioned breadth of their work, there is no denying that they do angst very, very well and this fic is no exception. We cried.

Sweetest Thing: One of the best things about Valaks’ work is that there is always something to suit any craving - something shown very well by Sweetest Thing. It proves its title right by demonstrating the recovery process Alex goes through after a catastrophic mission and the relationship that develops between him and Yassen. First and foremost, this fic is about the ways that people can find joy and meaning again, and it does it all realistically. ‘Realism’ is often misconstrued to mean ‘bleak’ when speaking about fiction, but here Valaks reminds readers that the small joys of good company and good are worth thriving for. At just over 1.2k, it is a short and sweet (if you’ll pardon the pun) story that lingers long after you’ve finished reading.

Gentleman’s Agreement: This fic is so good it’s now building its own small following of GA-verse fics (another rec for another time). Set in a semi-canon compliant world in which Alex still works for MI6 but is on his own, Yassen survived Air Force One, and they develop a “gentleman’s agreement” for when they encounter one another in the field. Only then Alex hunts Yassen down to ask him a favor. This fic explores a possibility which isn’t that far-fetched: what would Alex and Yassen do if they kept encountering one another in the field? And it has it all - humor; suspense; the mildest of angst; a tantalising ending leaving you wondering what happens next. We especially love this fic for the way it completely nails the tone of both Alex and Yassen. It also has a wonderful prequel in the shape of Turncoat.

The above recs feature quite a bit of Alex and Yassen, but we’d underline again that there is so much more in Valaks’ collection than just that pair. Some other highlights include A Warm Reception (a Ms Bedfordshire-centric trope flip), Druggy (a multi-chapter mission fic centering on Tom and Alex but heavily featuring Ben as Alex’s partner in MI6) and Signals (an Alex and Nile mentorship story).

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

“The big flaw with this is that it completely misunderstands who JK Rowling is and why she wrote the books. Simply put, this novel is a Christian tale. You miss that, you miss the entire point of everything it has to say.” Elaborate? Sounds interesting and I haven’t heard that before.

Well - I love this to bits and sort of wrote my thesis about it, so here we go.

Basically, you’ve got several kinds of heroes, but ‘left-wing hero’ is almost a contradiction in terms (more on this later). There’s your average Greek hero, whose status as a hero is more of a social class than it is a job and who generally doesn’t have any morally redeeming qualities (have you met Theseus?). Then there’s the medieval Christian hero - he comes in different flavours, but what’s relevant here is the Perceval model: basically the village idiot, whose only power is his good heart and who has no desire to challenge the status quo (because kings are divinely ordained and also poets tend to work for them, so ‘That vassal guy of yours has rescued yet another damsel’ story is going to be better received than ‘Your tax system is corrupt and this knight will now implement direct democracy’). Next you have the modern superhero, who was born in a very different historical context (the vigilantism of 19th century US) and as such has very different priorities. Namely: in his world, there is no higher authority and it’s up to him to use his superior skills to be judge and executioner so he can protect the most vulnerable. This understandable but toxic narrative will later get mixed up with WW2 and then the rampant capitalism of the last 30 years, resulting in the current blockbustery mess.

Anyway - if you’re a Western writer, it’s basically impossible to escape these three shaping forces we’ve all grown up with (classical Antiquity, Christianity, and US-led imperialism/capitalism), so most books and movies of the last forever decades can be analyzed through this lens. In the case of JK Rowling, what you have is a Christian author who openly used her YA series to chart out her own relationship with God. This is not a secret, or a meta writer’s delusion, or anything: she’s discussed it in several interviews. Her main problem, which is most believers’ main problem, is how to reconcile her faith in a benevolent God with the suffering in her daily life; and something she’s mentioned more than once is how her mom died when she was 25, and how this was very much on her mind especially when she was writing Deathly Hallows.

Now, I don’t want to write a novel here, so I won’t analyze the entire series, but what it is is basically a social critique of British society, mixed up with Greek and Roman elements in a cosmetic way only, and - crucially - led by an extremely Christian hero.

In every way that matters, Harry Potter is a direct descendant of Perceval: he’s someone who’s grown up in isolation as the village idiot (remember how he was shunned by other children because he was ‘dangerous’ and ‘different’), randomly found a more exciting world of which he previously knew nothing (he’s basically the only kid who gets to Hogwarts without knowing anything about the magical world, just like Perceval joined Arthur’s court after living in the woods for 15 years), and proceeded to make his mark not because of his innate powers or special abilities (he’s average at magic, except for Defence against the Dark Arts), but because he’s kind and good and humble. And in the end, he willingly sacrifices himself so everyone else can be saved: a Christ-like figure who even gets his very own Deposition (in the arms of Hagrid, the closest thing to a parent his actually has).

(This, by the way, was the only reason why Hagrid was kept alive. JK Rowling had planned to kill him, but she absolutely wanted this scene - one of the most recognizable and beloved image in Christian art - in the books.)

And even if he ultimately survives his ‘death’ (like Jesus did), Harry refuses the riches and rank he was surely offered and chooses to spend his days in middle-class obscurity as a husband and father (if I remember correctly, Harry and Ginny’s house isn’t even big enough for their three kids). And no, of course he doesn’t stand for anything or challenges the status quo: that’s not his job. His job, like Jesus’, was to defeat evil by offering himself up in sacrifice; and the entire story - especially the last book - is a profound, intimate, and very moving reflection on faith.

(“Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's”, remember? It’s not your job to change anything in the temporal, material world; your job is to nurture your immortal soul and prepare it for the true life that comes after death.)

Like - I don’t know how it was for younger readers, but for me, reading Deathy Hallows as an adult, it wrecked me. Even as an agnostic, I read it over and over again, and I kep finding new meaning in it. The whole thing is basically a retelling of the Book of Job, one of the most puzzling and beautiful parts of the Old Testament. That’s when Harry’s faith in God Dumbledore is tested, when his mentor, the cornerstone of his world, disappears; when Harry has to decide whether he’ll continue to believe in this absent, flawed figure despite all the bad things he keeps uncovering or give up his faith - and thus his soul - completely. The clearest, most startling moment exemplifying this religious dilemma is when Harry decides not to go after the wand. Getting it is the logical thing to do, the only way he can win, but Harry - while mourning Dobby - decides not to do it. That’s when he recovers his faith, and starts trusting his own kindness and piety (whatever happens, he will not defile a tomb) over everything else.

Another key moment is King’s Cross - here, and once more, Harry forgives his enemy, thus obeying Jesus’ commands. He sees Voldemort, the being who took everything from him - and he pities the pathetic, unloved thing he’s become. This is what sets him apart from everyone else and what makes him special: not his birth, not his magic, not some extraordinary artefact - but simply, like Dumbledore puts it, that he can love. After everything that’s bene done to him, he can still love; not only his friends, but his enemies. He forgives Voldemort, he forgives Snape, he forgives Malfoy, he forgives Dudley; and I see so many people angry about this, ranting about abuse victims and how hate is a right, but I think they’re missing the point. This is a Christian story; from a Christian perspective, your enemies need love more than your friends do.

(“It is not those who are healthy who need a physician” and all that.)

And in any case, a hero is inherently not left-wing. The whole trope relies on three rock-solid facts: the hero is special, and he can do something you can’t, and that gives him the right or the duty to save others who can’t save themselves. Whether it is declined in its Christian form (the hero as self-sacrificing nobody) or in its fascist form (the hero as judge and king of the inferior masses), that is is the exact opposite of any kind of left-wing narrative, where meaningful change is brought about not by individual martyrdom or a benevolent super-human, but by collective action.

So, yeah - Harry changes nothing and is not the leader of the revolution, but it’s unfair to link this to JK Rowling’s politics. It’s just how the trope works. And, in fairness to her, many kind and compassionate authors who write books concerned with social justice tend to lean towards this kind of hero because the only workable alternative - the fascist super-hero - is way worse. Had Harry been that, for instance, he would have ended up ruling the wizarding world. Would that have been better for its democracy? A 19-year-old PM who knows nothing about the law or justice or diplomacy? A venerated war hero drunk on power? Instead, JK Rowling chooses the milder way out: Harry and his friends do change the system - little by little, and within the limits of the genre. Hermione becomes the equivalent of a human rights lawyer, while Harry and Ron join the Aurors (and I know there’s a lot of justified suspicion towards law enforcement, but frankly having good people in their ranks is still the only way to move things forward. It’s been years and I still haven’t heard a practical suggestion as to how a police-less nation would work). As for the government, it is restored to a fairer status quo - again, not the revolution many readers wanted, but also not the totalitarian monarchies or oligarchies or the super-hero’s world.

And as to how one can write a story that’s actually revolutionary - I don’t exactly know. Some writers rely on multiple narrating voices to try and escape the heroic trope; others work on bleak stories which point out the flaws in the system and stop short of solving them. I guess that, in the end, is one of the problem with left-wing politics: they’re simply less eye-catching, less cinematic. On the whole, it’s dull, boring work, the victories achieved by committees and celebrated with a piece of paper. From a literary point of view, it just doesn’t work.

#ask#harry potter#hp#meta#jk rowling#tropes#heroes#literary tropes#ancient greece#superheroes#the jesus fandom#writers problems#right vs left#politics#again i don't hold it against it#i think it works beautifully#and has a lot to offer to non-believers as well

502 notes

·

View notes

Link

*desperately* click! click!

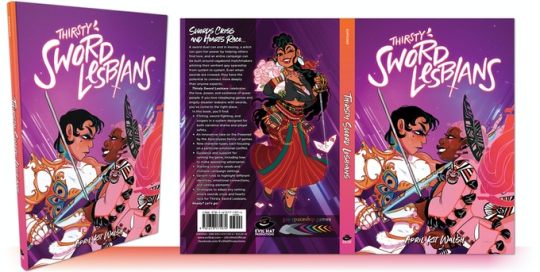

Thirsty Sword Lesbians battle the Lady of Chains when her enforcers march down from the frosty north. They rocket through the stars to safeguard diplomats ending a generations-old conflict. They sip tea together and share shy glances at the corner cafe with their old classmates and comrades. Even when swords are crossed, they have the potential to connect more deeply than anyone expects.

A sword duel can end in kissing, a witch can gain her power by helping others find love, and an entire campaign can be built around vagabond matchmakers piloting their sentient gay spaceship from system to system.

If you love angsty disaster lesbians with swords, you have come to the right place.

Thirsty Sword Lesbians by April Kit Walsh is a roleplaying game that celebrates the love, power, and existence of queer people—specifically queer people with swords and a lot of feelings. Flirting, sword-fighting, and barbed zingers all mix together in a system designed for both narrative drama and player safety. This innovative take on the Powered by the Apocalypse engine is a breeze to learn and ensures that no matter how the dice fall, something interesting happens to move the story forward.

In this game, you will solve problems with wit, empathy, and style, fight when something is worth fighting for, and redeem (or seduce) at least a few of your adversaries. You’re part of a community that embodies important ideals and you’ll strive to protect it and make your world better.

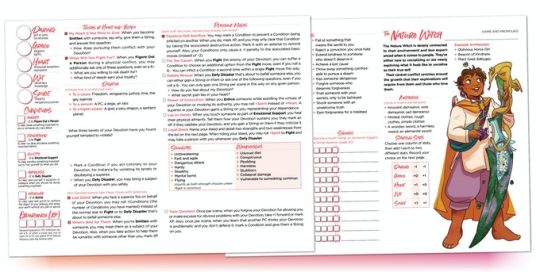

Play as one of nine character types: Beast, Chosen, Devoted, Infamous, Nature Witch, Scoundrel, Seeker, Spooky Witch, and Trickster. Each explores a particular emotional conflict that drives the drama and shapes your character’s story. Are you a Beast, faced with the dilemma of expressing your inner truth versus fitting in to a society that demands you conform? A Devoted, who sacrifices for others while struggling to care for yourself? A Trickster, who craves closeness but fears vulnerability? In long-term play, you may even resolve your initial arc and advance into a different playbook as you continue to change and grow, facing new challenges.

Backers get immediate access to the playbooks too.

They're form fillable!

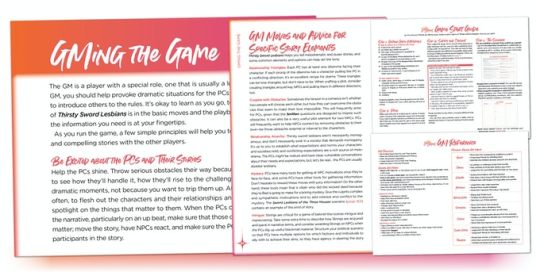

Thirsty Sword Lesbians provides clear, robust guidance and support for running the game, including how to make appealing adversaries, set the tone, structure play, and create a safe environment at the table. Handy reference sheets help you narrate appropriate twists and drama on the fly, depending on the feelings and character types you have in play.

Want to jump into a one-shot? The game includes six adventures that can stand alone or kick off a longer series: Sword Lesbians of the Three Houses, Best Day of Their Lives, Constellation Festival, Gal Paladins, and Monster Queers of Castle Gayskull. For even more inspiration, it features The Starcross Galaxy campaign setting along with five more settings from these contributing authors:

Lesbeans Coffehouse by Dominique Dickey

Neon City 2099 by Jamila Nedjadi

The Three Orders of Ardor by Whitney Delaglio

Les Violettes Dangereuses by Jonaya Kemper

Yuisa Revolution by Alexis Sara

We also provide ample guidance on how to create your own tales of fighting with swords and falling in love, along with a world building worksheet, variant rules, and a set of starting scenario seeds to play with. Because the game focuses on feelings and relationships, it’s a lens you can use to play in a variety of genres. If you like slashfic of characters with swords, you’ll love this game.

Thirsty Sword Lesbians is explicitly designed to tell melodramatic and queer stories; tales fraught with relationship triangles, mystery, intrigue, relationship anarchy, celebration, and revolution. It includes rules to highlight different identities, emotional connections, and setting elements.

This game is not for fascists, TERFs, or other bigots. The team behind Thirsty Sword Lesbians supports racial liberation, intersectional feminism, and queer liberation. We love and respect transgender people, nonbinary people, intersex people, and women. This game is a joyous celebration of lives and identities otherwise marginalized. If you don’t agree, fix your heart before sharing a table with other people.

What if... not Thirsty? The game fundamentally assumes that the characters crave connection, but that connection doesn’t need to be sexual or romantic. We offer you options for changing how the game addresses connection in our variant rules section.

What if... not Swords? It’s simple enough to swap out a different hand-to-hand combat option. Your campaign or your character can use a labrys, the double-bladed axe that became a lesbian icon in the late 20th century. You can use different styles of unarmed combat or even grapple using telepathic self-projections. It’s also possible to replace the swords with mecha, starships, or guns, but it requires some thought and the book will help you think about how to ensure that it stays intimate and relationship-focused. The conflict doesn’t have to be physically violent, either; you can use any kind of conflict that’s adrenaline-inducing and close-quarters.

What if... not Lesbians? We’ll let you in on a secret: you don’t have to play a lesbian. The game plays with themes that are common for all sorts of people who are marginalized on the basis of gender and sexuality, as well as feelings that go beyond the queer experience. If you want to play thirsty sword cishets, we’re not going to stop you—just don’t be surprised if the game turns them queer.

What if... I’m not good at flirting or zingers? You don’t have to be witty or good at flirting in real life to play a character with those skills, and not every character in Thirsty Sword Lesbians is good with words. Shy and awkward sword lesbians find love, too. You’ll find them well-represented in this game.

Ready? Let’s Go!

===============================================

Kickstarter campaign ends: Thu, November 12 2020 9:00 PM UTC +00:00

Website: [Evil Hat Productions] [facebook] [twitter]

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

TerraMythos 2021 Reading Challenge - Book 10 of 26

Title: The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890)

Author: Oscar Wilde

Genre/Tags: Fiction, Gothic Horror, Third-Person, LGBT Protagonist (I... guess)

Rating: 8/10

Date Began: 4/13/2021

Date Finished: 4/20/2021

When artist Basil Hallward paints a picture of the beautiful and innocent Dorian Gray, he believes he’s created his masterpiece. Seeing himself on the canvas, Dorian wishes to remain forever young and beautiful while the portrait ages in his stead. The bargain comes true. While Dorian grows older and descends a path of hedonism and moral corruption, his portrait changes to reflect his true nature while his physical body remains eternally youthful. As his debauchery grows worse, and the portrait warps to reflect his corruption, Dorian’s past begins to catch up to him.

Perhaps one never seems so much at one’s ease as when one has to play a part. Certainly no one looking at Dorian Gray that night could have believed that he had passed through a tragedy as horrible as any tragedy of our age. Those finely-shaped fingers could never have clutched a knife for sin, nor those smiling lips have cried out on God and goodness. He himself could not help wondering at the calm of his demeanour, and for a moment felt keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life.

Full review, some spoilers, and content warnings under the cut.

Content warnings for the book: Misogyny (mostly satirical). Racism and antisemitism (not so much). Emotional manipulation, blackmail, suicide, graphic murder, and death. Recreational drug use.

Reviewing a classic novel through a modern lens is always going to be a challenge for me. The world seems to change a lot every decade, let alone every century—whether some canonized classic holds up today is pretty hit or miss (sorry, English degree). And considering the sheer amount of academic focus on classic texts, it’s not like I’m going to have a “fresh take” on one for a casual review. I read and reviewed The Count of Monte Cristo last year, and thought it aged remarkably well over 170+ years.

Somehow I never read Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray for school. I tried reading it independently in my late teens/early twenties, and honestly think I was just too stupid for it. Needing a shorter read before the next Murderbot book releases at the end of the month, I grabbed Dorian Gray off the shelf and decided to give it another shot. By the end, I was pleasantly surprised how much I liked the book.

I’m actually going to discuss my pain points before I get into what worked for me. The first half of the book is very slow-paced. The Picture of Dorian Gray is famous for… well… the picture. But it isn’t relevant until the halfway point of the novel, when Dorian does something truly reprehensible and finds his image in the picture has changed. There’s a lot of setup before this discovery. The first half of the book has a lot of fluff, with characters talking about stuff that happened off screen, discussing various philosophies, and so on without progressing the story. Some of this is fine, as it establishes Dorian’s initial character so the contrast later is all the more striking. I just think it could have been shorter. I realize this comes down to personal taste.

I’m also torn on the Wilde’s writing style. He’s very clever, and there are many philosophical ideas in his writing that did genuinely made me stop and think. The prose is also beautiful and descriptive; this is especially useful when it contrasts the horror elements of the story. However, there’s a lot of unnatural, long monologue in the story. Not sure if it’s the time period, Wilde’s background as a playwright, or just his writing style in general (maybe all three), but the characters ramble a LOT. My favorite game was trying to imagine how other characters were reacting to a literal wall of text.

I also feel the need to mention this book has some bigoted content, as implied in my content warnings. The misogyny in the story is satirical; it’s spouted by the biggest tool in the book, Lord Henry, whose whole shtick is being paradoxical. You just need basic critical thought to figure that out. However, some things don’t have that excuse. A minor character in the first half is an obvious anti-Semitic caricature. There’s also some pretty racist content, particularly when Wilde describes Gray’s musical instrument collection. While these are small parts of the book, it’d be disingenuous not to acknowledge them.

All that being said, there were many aspects of the book I enjoyed, particularly in the second half. Wilde does a great job characterizing terrible people who fully believe what they say. Lord Henry is an obvious example, and Dorian follows his lead as the story progresses. One of my favorite bits was after Sibyl’s suicide (which Dorian instigated by being a piece of shit). Dorian is initially shocked, but as he and Lord Henry discuss it, they come to the conclusion that her suicide was a good thing because it had thematic merit. It’s just such a brazen, horrible way to alleviate one’s guilt.

Dorian also goes to significant lengths to justify his actions. At one point, he murders Basil to keep the portrait a secret. While he briefly feels guilty about this, Dorian grows angry at the inconvenience of having killed this man, supposedly an old friend. He even separates himself from the situation, expressing that Basil died in such a horrible way. Bro, you killed him! It was you! The cognitive dissonance is just stunning.

It’s also viscerally satisfying to read about Dorian’s downfall as his awful choices catch up to him. Dorian becoming tormented by the portrait is just... *chef’s kiss*. Is it surprising? No, it’s pretty standard Gothic horror fare. But there’s something to be said about seeing a genuinely horrible man finally pay for what he’s done after getting away with it for so long. I wish real life worked that way.

There’s the picture itself, too. I know it’s The Thing most people know about this novel -- but I just think it’s a cool concept. I like the idea of someone’s likeness reflecting their true self, and the psychological effect it has on the subject. Most of the novel is fiction with realistic horror elements, but I like that there’s a touch of the supernatural thanks to Dorian’s picture. It’s an element I wouldn’t mind seeing in more works.

It's sad to read Dorian Gray with the context of what happened to Wilde. The homoeroticism in the novel is obvious, but tame compared to works today. Wilde and this book are a depressing case study in how queer people are simultaneously erased and reviled in recent history. Wilde was tortured for his homosexuality (and died from resulting health complications) over 100 years ago, yet the 1994 edition of Dorian Gray I read refers to his real homosexual relationship as a "close friendship". It's an infuriating and tragic paradox. Things have improved by inches, but we still have so far to go.

As I grow older I find I appreciate classic works more than when I was forced to read them for school. The Picture of Dorian Gray is a gripping Gothic horror story. Some aspects didn't age particularly well, but that's true for almost anything over time. If you're in the market for this kind of book, I do recommend it.

#this review is late but in my defense the nier remake came out#taylor reads#2021 reading challenge#8/10

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

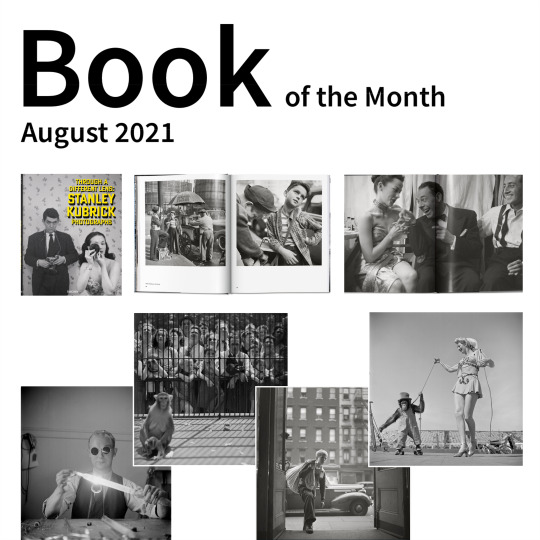

Book of the month / 2021 / 08 August

I love books. Even though I hardly read any. Because my library is more like a collection of tomes, coffee-table books, limited editions... in short: books in which not "only" the content counts, but also the editorial performance, the presentation, the curating of the topic - the book as a total work of art itself.

Through a different Lens

Stanley Kubrick (& Sean Corcoran, Donald Albrecht, Luc Sante)

Photography / 1997 / Taschen Publishing House

Every now and then, I sentence the kids to watch movies that I think are relevant - whether from a personal or a cinematic point of view. While my little son tends to be served light fare like "Blues Brothers," my big daughter sometimes has to chew a little harder, as happened the other day with "2001: A Space Odyssey." Her enthusiasm was a bit restrained, even if I exclaimed about 23 times, "That movie is from 1968. There were no special effects then, it's all actually built!".

Even regardless of that aspect, this epic can be considered groundbreaking. From the genre reference of the classical music background and the excellent script, to the technological authenticity and the almost psychedelic color scheme, to the revolutionary camera work. Above all, the visual composition of this film is the true mastery of director Stanley Kubrick, who is not considered one of the most important filmmakers of all time for nothing. Of course, I also have the matching book in my library ("The Making of Stanley Kubrick's '2001: A Space Odyssey'", also from Taschen, of course), but this time it's about another work of this visually powerful creator: his early work, photography.

"In the Streets of New York" is the title of the publisher's documentary "Through a different Lens" on the occasion of an exhibition of the same name at the Museum of the City of New York. For it was there that Kubrick, just 17 years old, went on his first stalk of optical impressions. In 1945, he signed on as a photographer for the magazine "Look," for which he photographed stories with a human touch in the streets, clubs and sports arenas of New York City for five years. In the process, he captured with his camera just about everything that made up life in the Big Apple in that era: People in the laundromat, the hustle and bustle at Columbia University, sports stars, showgirls in their dressing rooms, performers in the circus, Broadway actresses rehearsing their lines, cab drivers changing a tire, couples kissing on the train platform, shoe shine boys, boxers reconsidering their career choice in the ring corner, patients in their dentist's waiting room, prominent businessmen, politicians, children in the amusement park, and commuters on the Subway.

Even these photographs from Kubrick's younger years reveal a startling sense of composition, tension, and atmosphere, and seem like film stills to never-shot dramas from the jungles of the big city. "This exhibition reveals how (Kubricks) formative years laid the groundwork for his compelling storytelling and dark visual style. They also show a noir side of New York that's no longer around." (Vanity Fair) "Photography, and particularly his years with Look magazine, laid the technical and aesthetic foundations for a way of seeing the world and honed his ability to get it down on film. There, he mastered the skill of framing, composition and lighting to create compelling images," explains Sean Corcoran, curator of the exhibition "Through a different Lens" and co-author of the book. Apparently, it was clear to the young man from the very beginning where his talent lay and how he was able to hone and master it.

Stanley Kubrick was born in New York City on July 26, 1928, as the first of two children. His parents came from Jewish families, and all of his grandparents had immigrated from Austro-Hungarian Galicia. His early passions were excessive reading, cinema and chess. He was first gifted a camera, a Graflex, from his father when he was 13 years old. And he immediately took off as a photographer for the William Howard Taft High School student newspaper. After graduation, he turned his hobby into a career and at the age of 18 became a full-time photographer for Look, to which he had previously sold amateur photos. As early as 1950, Kubrick directed his first documentary, "Day of the Fight", about life in and around the boxing ring, which he had already explored photographically. Although only 16 minutes long, the film was already considered a sensational study at the time. His future career path was set, the rest is history.

"Through a Different Lens" was an extremely successful exhibition, which subsequently also went on tour. Not only Kubrick fans were impressed by the mastery of optical staging that was already visible at an early stage. Corcoran: "Kubrick learned through the camera's lens to be an acute observer of human interactions and to tell stories through images in dynamic narrative sequences. (His) ability to see and translate an individual's complex psychological life into visual form was apparent in his many personality profiles for the publication. His experiences at the magazine (Look) also offered him opportunities to explore a range of artistic expressions. Overall, Kubrick's still photography demonstrates his versatility as an image maker. Look's editors often promoted the straightforward approach of contemporary photojournalism at which Kubrick excelled. It's clear he always got the photographs that were needed for the assignment, but that he was also unafraid to make pictures that excited his own aesthetic sensibility."

Beyond the 100 photographs in the exhibition, the book presents 300 of Kubrick's images, including unpublished shots and outtakes. Annotated by Corcoran, his colleague Donald Albrecht, and renowned writer and critic Luc Sante, who has published most notably in Interview and Harper's. They place the motifs in their context, refer to stylistic aspects, and thus point to Kubrick's (imminent) artistic career. Above all, in contrast to the exhibition, the book offers all friends of photography - whether fans of Kubrick or not - a rare insight into the proverbial pioneering early work of a brilliant artist. And into one of the most interesting eras of the "city that never sleeps" - yes, even Frank Sinatra was photographed by young Kubrick.

From the extensive, mostly euphoric reviews of the book "Through a different Lens" or the oeuvre documented in it, let's take one example each from a professional and an amateur:

"The man who later led a genre to its lonely high point and at the same time to its final point with each of his films knew already at the age of barely 17, that's how old he was at the time, that expression and form shape every impression." (Die Welt)

"I can't praise this book enough. Wonderful collection and very informative. An absolute must for those wishing to understand more of how Kubrick valued the frame." (Yvi on amazon.com)

P.S.: Just for the sake of completeness, let's mention Kubrick's cinematic output after his breakthrough: 1960: Spartacus / 1962: Lolita / 1964: Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb / 1968: 2001: A Space Odyssey / 1971: A Clockwork Orange / 1975: Barry Lyndon / 1980: The Shining / 1987: Full Metal Jacket / 1999: Eyes Wide Shut. No, this is not a selection of greatest hits, this is a complete listing. And thus the proof that he has indeed realized a significant peak in the respective genre. His great influence on the history of cinema is also shown by the fact that he is the only director to appear a total of five times in the list of the 100 films with the best critics' ratings.

In addition, two side notes: Kubrick spent several years preparing a film biopic about Napoleon Bonaparte. The preparations were so far along that he could have started production at any time. However, the release of "Waterloo" (1970) and its poor financial results dissuaded him and the film studio from the project. The project has since been known as "The greatest Movie never made". He also dealt intensively with the subject of the Holocaust. After the release of "Schindler's List" (1993), however, he discarded these plans explaining that Steven Spielberg had already told all the essential.

Stanley Kubrick died of a heart attack on March 7, 1999, in his home at Childwickbury Manor near London, where he had lived in seclusion since the 1960s and had set up studio and editing rooms in the former stables.

Here's a short trailer for the exhibition "Trough a different Lens":

https://youtu.be/EgPlnjeBs7E

youtube

#stanley kubrick#look magazine#taschen#new york city#photography#book review#book#steven spielberg#Through a different lens#Sean Corcoran#Donald Albrecht#luc sante#2001: a space odyssey#museum of the city of new york#big apple#the city that never sleeps#cinema#movies#director#visual style#visual storytelling#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Friend Dahmer. By Derf Backderf. New York: Abrams ComicArts, 2012.

Rating: 4/5 stars

Genre: memoir, graphic novel

Part of a Series? No

Summary: In 1991, Jeffrey Dahmer — the most notorious serial killer since Jack the Ripper — seared himself into the American consciousness. To the public, Dahmer was a monster who committed unthinkable atrocities. To Derf Backderf, “Jeff” was a much more complex figure: a high school friend with whom he had shared classrooms, hallways, and car rides.

In My Friend Dahmer, a haunting and original graphic novel, writer-artist Backderf creates a surprisingly sympathetic portrait of a disturbed young man struggling against the morbid urges emanating from the deep recesses of his psyche — a shy kid, a teenage alcoholic, and a goofball who never quite fit in with his classmates. With profound insight, what emerges is a Jeffrey Dahmer that few ever really knew, and one readers will never forget.

***Full review under the cut.***

Content Warnings: ableism, allusions to animal harm/death, implication of murder

Overview: This graphic novel/memoir has been on my radar for a while, but I only recently picked it up for reasons I can’t quite articulate. I’m not sure what I was expecting - thrilling tale of teen psychosis, the makings of a depraved murderer, I don’t know. Perhaps my lack of concrete expectations served me well, since what I found in Backderf’s book was a sympathetic look at Jeffrey Dahmer as a teenager and all the warning signs that were ignored by the adults around him. In a way, it was a heartbreaking read. I don’t think Backderf was trying to excuse Dahmer’s crimes by showing that he only did it because he had a rough life. Rather, I think Backderf was trying to reconcile the “serial killer” Dahmer with the kid he actually knew in real life. For that, I’m giving this book 4 stars.

Writing/Art: Backderf’s art style is fairly “cartoony” in that it doesn’t try to have accurate proportions or imitate reality. Certain facial (or any anatomical) features are exaggerated and there’s a lot of heavy linework, which doesn’t quite communicate “horror” as one might expect about a tale about Jeffrey Dahmer. In a way, I think this works for the story Backderf is trying to tell: it almost seems absurd and grotesque that nothing was done to help Dahmer as a kid, and the art style embeds these feelings in the shapes and linework. One might also argue that the style almost seems juvenile (though it isn’t) and that quality enhances the fact that this story is being told through the eyes of a teenager.

Personally, though, Backderf’s style has never really been my aesthetic of choice, but that’s my personal preference and not a knock against the author/artist. If it works for you, that’s great.

In terms of narration, I liked that Backderf was honest about his impressions of Dahmer. At no point did he claim that he “always knew something was wrong about him,” nor did he seem to play up the proto-serial killer vibes. Instead, Backderf uses subtler, unsettling feelings that show something was “off” but not so “off” that they could have been expected to report Dahmer to the police or something. In a way, it’s fairly truthful and shows how sometimes, you can get a vibe off someone, but not really know what’s going on with them. It also reassured me that Backderf was writing not to somehow leech fame off of Dahmer (for whatever reason) but to work out his own emotions.

Plot: This graphic novel is divided into five parts, plus a prologue and epilogue, that each focus on certain aspects of Dahmer’s life. Part One establishes the setting and Dahmer’s home life; Part Two portrays Dahmer’s alcoholism and the rise of his darker urges, which he desperately tried to control; Part Three is about Dahmer’s relationship with Backderf and their antics at school; Part Four is about how the end of high school was a breaking point for Dahmer; and Part Five is a reflection on how Backderf and his friends left Dahmer behind and how that isolation allowed him to start killing.

I think the organization of these memories into separate sections worked well. Though they followed a loose chronology, I felt like each section had a theme or goal so that Dahmer’s story felt like it was progressing rather than just existing all at once. I appreciated the sympathetic lens that Backderf uses to tell his story; multiple times throughout the novel, he questions where the adults were and how it was easier to not make a fuss. I think, in doing this, Backderf communicates the difference in culture in the 1970s and avoids portraying himself and the literal kids around him as responsible for not stopping Dahmer.

The only thing that I think could have made this story a bit more “real” and grounded for me would be if Backderf had used more of Dahmer’s own words from interviews. To his credit, Backderf quotes Dahmer in a few places, such as the epilogue and at the beginning of Part One, but I think I would have liked to see Dahmer’s voice more often, or at least Backderf’s reactions to Dahmer’s voice more often. Backderf says in his author’s notes that his portrayal of Dahmer is constructed from his own memories and the memories of others who knew him, as well as from transcripts and recordings of interviews with Dahmer, but I wonder if more of Dahmer’s own voice could have been woven into the panels. To be fair, though, this book isn’t trying to illustrate Dahmer’s life from Dahmer’s point of view; it’s specifically a memoir about Backderf’s perception and relationship with him. But it would have been interesting, I think, to see if there was a disjoint between what Dahmer said about himself and what Backderf saw as a kid.

Characters: I hesitate to analyze the figures in this book as “characters” because they’re all real people. I don’t have the knowledge to determine if Backderf is “accurate” in his portrayal or not, but that wouldn’t be productive anyway, since the point of this book is to offer a perspective rather than an objective account.

Instead, I’ll use this space to communicate how certain figures come across to me as a reader. Dahmer is incredibly sympathetic, to an extent. Backderf does a good job of making him feel like an outcast and a loner at some moments and something of a lolcow at others, which seems consistent with accounts that state that Dahmer seemed to have friends but was actually very isolated. From these moments, I got the sense that Dahmer was suffering; rather than taking joy in his “perverse” urges, it felt like he did everything he could to suppress them until the only thing that kept him in check (high school social life) disappeared. As a whole, then, it seems like Dahmer was a kid in desperate need of help, but he didn’t live in a culture that could really do so. If that was Backderf’s goal, then he achieved it.

However, I do think Backderf toes a little too close to the line of portraying Dahmer as wholly sympathetic. To be fair, it’s a hard balance to strike - you want to condemn Dahmer’s later actions, but you also want to sympathize with the kid he was at the time before he started his killing spree. To address this, it might have been interesting to flash back and forth between Backderf’s high school memories and his impressions or emotions when learning about Dahmer’s crimes or arrest/trial, but I’m not sure if that would have been in line with what Backderf was trying to do. So, it’s just an idea.