#masculine coding as neutral

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I view this more as a basic empathy test. Sure I still say it sometimes, but only where I know for sure as a fact it's ok. There is a great chapter in the book Word By Word by the lexicographer Kori Stamper about the history of using masculine-coded words as "neutral" even though they aren't and never were.

And like yes, language evolves and colloquialisms exist and there's nuance and exceptions to every rule etc etc etc.

Ultimately, when presented information about something you do, that doesn't have a single damn impact on you personally beyond the learning curve of changing a habit, but that the thing DOES HARM other people, and your knee jerk reaction is "well I don't MEAN it to be harmful," like...this is the impact vs intent discussion, right!

Do you view the word "dude" as gendered?

#dude#gender neutral language#masculine coding as neutral#its like when the language of the constitution “HE throughout) was used as legal recourse to prevent women from voting#or when in the year 2025 authors insist on repeating “he or she” a million times instead of sometimes swapping out with “they” sometimes#all im saying is English is a complicated language and it isnt going to get easier#and our goal should maybe be radical empathy instead of grammatical prescriptivism?

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

im pretty sure neither of us are cis but im not saying anything until you say something

#the friend i made a band with#well their pfp on one platform had a genderfluid flag#and i have very good reason to suspect them of being queer#its honestly kind of funny bc neither of us have come out yet#we both have been communicating in the valuable code language of#“you know good omens” “yeah i love good omens!”#and sending each other tumblr memes#but neither of us has outright said “im queer” or “im gay” or anything#its kind of funny#we were coming up with stage names for our band#and we kept looking at the “baby boy” and “gender neutral” names lists#and ended up compiling a pretty good list of exclusively masculine names#despite both of us being “girls”#but there is no way im coming out first ive already come out too much recently#three pigeons in a trench coat

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ack, almost forgot the kinda transphobic guy who talked to me between bands at the gig... anyway, glad I could avoid telling him my birth name or giving him any contact info

#the stresses of looking and sounding like a girl and introducing yourself with a name that's masculine-coded in your language#at least i could divert the convo by telling the guy it's a gender neutral name in english speaking countries. thank fuck i picked robin#also... idk if i should come out to the band and the other people i met at the gigs if i get to know them better. ugh.#guess i'll let them think i'm a weird girl with a quirky name for a while longer...#meeting people in real life is so much more difficult in that regard. online you just say you're a guy and (almost) everyone respects it#offline people just go off of the way you look and you gotta watch out who you come out to or else risk real time real life harm ugh

1 note

·

View note

Text

🦇🎃 ~the mask~ set! 🎃🦇

happy halloween season!! this mask set was inspired by @simandy's beautiful ursa mask, and @1-800-cuupid’s ghostface mask!

-

THE MASK SET:

♥ base game compatible!

♥ found in the hat category

♥ 6 versions! neutral, sad, and evil expressions, and then a version of each on the face and on the head.

♥ teen-elder, feminine and masculine frames

♥ the masks will project the texture from your sims face, but each version has 3 swatches for the eye holes

♥ the facial proportions of the mask are from the default feminine frame, so resemblance to your sim may vary from uncanny copy, to vague likeness

♥ 2.8k~ poly

-

Follow me on twitch!

Support me on patreon!

⇢ download: simfileshare | patreon

use my code "THATONEGREENLEAF" when you buy packs in the EA app to directly support me! ♥ (not a discount code, I wish!)

I DO CUSTOM CAS ROOM (and other) COMMISSIONS! fill out my commission form ♥ (currently closed)

TOU: do not claim my cc/CAS rooms/presets as your own! recolour/convert/otherwise alter for personal use OR upload with credit. (no paywalls, no c*rseforge)

#sims4#thesims4#ts4#s4cc#ts4cc#sims 4 cc#sims 4 custom content#my cc#the sims cc#sims4mm#maxis match#maxis mix#sims 4 mask#ts4 accessory

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Honestly I think Shawn, a grown man, can stand up for himself lol

“He’s a grown man, he can stand up for himself.”

Right—but that response isn’t as neutral as you think. It’s a deflection. A way of shifting responsibility for boundary enforcement back onto the individual who’s been placed in an uncomfortable position, rather than asking why he was put there in the first place.

Because this isn’t about whether Shawn Hatosy—or Pedro Pascal, or any other man—can assert a boundary. It’s about how we’ve created a culture that expects them not to. It’s about how consent is routinely ignored, overwritten, or turned into a joke in public space—especially when it comes to men, especially when it’s dressed up as irony, “feminist thirst,” or progressive kink-positivity.

It’s about the refusal to admit that consent isn’t just about sex.

Consent is about presence. It’s about participation. It’s about emotional safety. And it’s about power.

And that matters in every context—including fandom, celebrity culture, and the increasingly blurred space between admiration and projection.

When you call a male celebrity “daddy” in the middle of an interview—on camera, unprompted, fully aware it’ll go viral—you’re not giving a harmless compliment. You’re placing him inside a sexualized, hierarchical, kink-coded role, and demanding a performance. You’re not inviting him into a shared dynamic. You’re building one around him and daring him to resist.

And that’s not just parasocial behavior. That’s coercion. Coercion dressed up in a clickbait blazer and a winking “teehee.”

And patriarchy? Patriarchy loves that. Because patriarchy has always taught us that men, especially older, stoic, men, aren’t allowed to have boundaries. That they should be flattered by sexual attention. That their discomfort is a flaw in the man, not a failure of the situation. That a man’s silence means yes.

So when a male celebrity tenses up or shifts uncomfortably after being called “daddy,” we don’t pause. We dismiss him. We say:

“Come on, it’s just a joke.”

“He’s hot. He can take it.”

“It’s part of the job.”

That’s not the language of consent. That’s the language of normalized entitlement.

Now compare that to when I commented on Shawn Hatosy’s TikTok and said he was “so babygirl-coded.” And he liked it.

Why? Because “babygirl,” as it functions in contemporary online fan culture, isn’t built on dominance or performance. It doesn’t demand control. It doesn’t assign erotic authority. It’s a term that signals affection, vulnerability, softness—a playful, sometimes absurd, often tender reverence for men who deviate from traditional masculinity.

That kind of language lives within fandom culture—inside our sandboxes. And when I call someone “babygirl-coded,” that person can ignore it, engage with it, scroll past, or opt in. There’s no pressure. It’s an aesthetic label, not a demand. So when Shawn likes that comment, he’s participating on his own terms. That’s what parasocial consent looks like: voluntary, pressure-free, and rooted in choice.

Now imagine if I had written, “You’re such a daddy. Ruin me.” Totally different tone. Totally different power dynamic. Even if he never saw it, I’d still be inserting a kink-coded script into a public space as if he had agreed to it. And if he had seen it and felt uncomfortable? The onus would fall on him to disengage quietly or laugh it off, because culturally, we’ve given men almost no tools to say “no” without backlash.

Feminist methodology asks better questions:

Whose comfort is protected?

Whose silence is treated as consent?

Whose body is seen as public property?

Whose boundaries get overwritten for the sake of the bit?

We know the answers. They’re gendered. And they’re broken.

When a man is called “daddy” during a press tour, he’s not being asked to play. He’s being expected to perform, sexually, powerfully, on command. And if he doesn’t? The consequences aren’t just social, they’re structural. He’s seen as less fun. Less marketable. Less valuable as content.

That isn’t just unfair. It’s anti-consensual.

As Sara Ahmed writes, to be the one who names a problem is so often to become the problem. The one who says “this feels off,” “this crosses a line,” or simply, “this makes me uncomfortable” is marked as difficult, humorless, or ungrateful. We see this dynamic unfold constantly with male celebrities—especially those who don’t laugh when called “daddy” in person, or who subtly resist being pulled into a sexualized performance they didn’t agree to.

When a man sets a boundary, even quietly, he disrupts the fantasy. And instead of asking what created the discomfort, the culture asks why he couldn't just go along. Because admitting that men can say no, that they’re allowed to feel uneasy, that they don’t exist for our projection, requires challenging the very entitlement fandom often runs on.

So let’s be clear: You can thirst. You can spiral. You can bark, cry, and post your little essays about his shoulders in peace. You can call him whatever in your sandbox corner of the internet.

But forcing someone into your kink-coded fantasy in person, without their consent, and then reacting negatively when they don’t play along, isn’t empowering. It’s not subversive. It’s just public boundary crossing, dressed up as flirtation.

It’s not “owning the gaze.” It’s replicating it—just with the roles reversed.

And reversing the roles isn’t the same as dismantling them.

Roles—no matter how ironic or reversed—are still roles. And assigning someone a role without their participation isn’t liberation. It’s just performance under pressure.

So yes, he’s a grown man.

And that’s exactly why his boundaries matter—especially because he’s not just a celebrity, but a real person, and a parent. Being called “daddy” in person, during a professional setting, isn’t just awkward—it’s an unsolicited invitation into a kink-coded dynamic he didn’t agree to. And when that man is a father in real life, the term becomes even more jarring, blurring roles in a way that’s neither funny nor flattering. His visibility shouldn’t come with the expectation that he absorb sexual projection or emotional labor just to keep the mood light. Silence is not consent. And feminist ethics, if we’re actually practicing them, demand more than clever thirst and role reversal. They require awareness, accountability, and respect for boundaries, no matter who you’re talking to or how attractive you think they are.

And if your only defense is “He can take it,” you’ve already admitted he might not want it, and decided you didn’t care.

That’s not fandom. That’s entitlement. Wrapped in a punchline and passed off as progressive. (referencing this interview)

#ask#anon ask#if any of u want more feminist pieces im more than happy to rec#but sara ahmed covers everything in her book so well#PLEASE STOP FORCING DADDY / MOMMY ON CELEBS IRL#feminist theory#consent culture

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lay All Your Love on Me (Homelander x Reader)

Summary: A communication breakdown has unintended consequences, but it’s all because Homelander loves you.

Note: Gender neutral reader and no descriptors are used. This is based on a request from @judyfromfinance and the ABBA song which is so Homelander coded. Do not interact if you’re under 18 or post thinspo/ED content.

Word count: 1.6k

Warnings: Jealousy, possessive behavior, violence (not toward the reader). We love miscommunication for plot reasons here! Do not interact if you’re under 18.

Homelander had no reason to believe you were hiding from him. Your job kept you busy, and ironically enough, working for the same company didn’t guarantee that you’d see each other nearly as much as he’d like. When his texts went unanswered and he couldn’t so much as hear you during the day, though, his mind went into overdrive presenting him with every worst case scenario it could possibly conceive of.

Cheat. Cheat. Cheat.

His gloved hands balled into fists at his side. You would never cheat on him. He knew that. He did. But sometimes, it seemed like your heart didn’t ache for him the way his did for yours. You had a life outside of him, and as much as you tried to include him in it, he resisted. Things would be easier if it were just the two of you.

Trying your phone again, he called you, frustrated when it went straight to voicemail.

“Hey babe, it’s me. I’ve been trying to reach you all day. Give me a call back as soon as you can. I love you,” he said, adding a quick. “Call me back" for emphasis.

He groaned, throwing his phone aside and folding his arms over his chest. It was fine. He didn’t care that much anyway. At least that’s what he told himself as he glanced at his discarded phone every few seconds in hopes you’d call or text back. No dice.

As a last resort, he headed to the crime analytics department. You managed a small team of analysts who consulted with the state and federal government on Vought’s behalf. The two of you had met when Vought was trying to get supes in the military, and as far as Homelander was concerned, it was love at first sight.

Never mind that it took a few weeks to win you over, frustratingly committed to your job and hesitant to date a coworker. Even though he’d hardly consider the two of you coworkers. Sure, you both worked for Vought, but that was it as far as he was concerned. In his determination to woo you, he’d made some valuable connections in your department. At least, people who he knew would have some kind of scoop on you when he needed it.

“Hey Annika,” Homelander said, startling the young crime analyst as he approached her desk. “How’re you doing, pal?

“Hi Homelander,” she said, not quite able to keep eye contact with him. “Sir. I’m good. H-How are you?”

“You haven’t seen Y/N around today, have you?”

She shook her head. “Sorry.”

“Alright,” he said tensely, a painfully fake smile spreading across his face. “Keep up the good work.”

His smile faltered as he heard your name come up in a conversation on the other side of the room. A masculine voice, younger than his, far too much mirth for his liking when he spoke about you.

“Dude, I was in Y/N’s office for like an hour yesterday. I could barely concentrate. They are so fine.”

“You’re insane,” someone else laughed.

“What? Have you seen them?”

“They’re dating Homelander, dumbass.”

“Whatever. It won’t last. He and Maeve will get back together, and yours truly will be there to pick up the pieces.”

“If you say so.”

Homelander hadn’t noticed his eyes glowing red until Annika squeaked. Letting out a breath he didn’t even know he was holding, he looked at his…acquaintance.

“See you around,” he said, his chipper tone clearly strained.

Since you weren’t answering your phone and he still had no clue where you were, Homelander had all the time in the world to wait around for your sleazy subordinate to take a bathroom break. He wondered if you were aware of the man’s interest in you. It was a possibility, but he had to assure himself that you wouldn’t do anything to encourage it. He knew you wouldn’t bother with a miscreant like that, of all people, but the point needed to be made. No one could speak so vulgarly about you and expect him not to do something about it.

Fifteen minutes or so had passed, and Homelander spotted his name badge. Josh.

“Hey Josh! You have a minute, buddy?” Homelander asked, voice booming through the hallway, causing Josh to flinch. Homelander smirked a bit.

“Homelander! Is there something you need?”

“Yeah, actually, I just have a question about the crime analytics office.”

Josh nodded. “Sure, anything.”

“Did you see any Greek letters in there?”

“Wh-What?”

“Did you see any Greek letters in there? Maybe a keg and some drunk idiots wearing togas?”

“I don’t—“

“Did you?”

“No.”

“Then why were you in there talking about my partner like you were in a fucking frat house?” Homelander asked, cornering the slimy analyst. “You know Y/N and I are dating, right? Your idiot friend told you as much.”

Josh’s mouth flopped open and closed like one of the disgusting fish The Deep crusaded for. “I—I didn’t mean—“

“So either you’re incredibly stupid, or you have a death wish. Which one is it, buddy?”

“I’m so sorry, Mr. Homelander.”

Homelander chuckled, empty and hollow, reveling in the way he could practically smell the fear radiating off of the man in front of him. “You will be.”

With the way Josh was carrying on, Homelander would’ve thought he’d actually killed the guy. All he’d done was snap his arm and throw an elbow to his nose. He’d just bought the asshole a free rhinoplasty, far more generous than he deserved after what he did.

Homelander sneered at the blubbering crime analyst, work shirt covered in his own blood. Pathetic, really. And he had the audacity to act like he was worthy of you. Throwing one final glare Josh’s way, Homelander walked off, wiping the blood off his gloves and onto his suit. It could be dry-cleaned out.

The outburst made him feel better than he had all day, though it didn’t answer the question of where the hell you were and why you weren’t answering him. Besides, he swore he heard the familiar sound of your footfall in the lobby.

He supposed you wouldn’t be too happy if you came back to see one of your subordinates brutalized in the hallway. Just his luck, he spotted an intern in one of the unoccupied offices.

“Hey,” Homelander said, pausing a moment to read the intern’s badge, “Sammy, there’s a mess over by the crime analytics office, can you get someone to clean it up?”

“Sure,” Sammy responded cheerfully.

“Thanks, it’s the little things that make this place run. You’re doing great,” he complimented, giving her a friendly pat on the shoulder.

Sammy returned his smile, obviously not questioning his sincerity. Homelander knew if he framed the whole thing as a favor, she’d be more likely to follow through. It was always good to have reliable people in his back pocket for things like that, worker bees who thought they were friends or something. She walked off, strides purposeful as she set off to complete her personal mission from Homelander.

Rushing over to the elevator, he listened for you, getting out on the fifteenth floor where he saw you just as you walked out of the bathroom.

As soon as he made eye contact, he melted, making a beeline for you.

You smiled, wrapping your arms around Homelander. “Aren’t you a sight for sore eyes.”

“Where were you?” he asked, almost painfully returning your embrace.

“I told you I was presenting for the security council at the UN all day. No phones, remember?”

He huffed, releasing you from the hug. Fuck. “I guess—maybe that rings a bell. You shouldn’t tell me something so important while I’m distracted.”

“How much did you miss me?” you teased, holding up your pointer finger and thumb to pinch the air. “This much?” You spread your fingers wider. “This much?” Wider again, except before you could ask, Homelander scooped you up in his arms.

“Why don’t I show you?”

“Please do,” you said, tilting your head up to kiss him.

He retreated into the elevator with you, his lips capturing yours in a desperate kiss laced with longing. You giggled at him. You’d only been gone for a few hours, yet he was acting as though it had been days.

You missed him too, resolving to focus your attention on him for the rest of the night.

Until your phone rang.

“I should get this.”

“Now you’re able to pick up a call?” he grumbled, setting you down.

“One minute,” you whispered, grabbing your phone, “then I’m all yours.”

He pressed the button to his suite, having forgotten to do so in the heat of passion. “You better be.”

You picked up your phone, amused at Homelander still clinging to you, kissing your neck. “Hello?”

“Josh from crime analytics?” you asked, tensing a bit when Homelander grazed his teeth on the crook of your neck. “I haven’t heard from him since he gave me the homicide report yesterday.”

Homelander hummed against your skin, and you let out a whimper only he could hear at the way it vibrated through you. He was smug, and it took you a moment to piece together why.

“Okay, talk to you tomorrow,” you said before hanging up. “What did you do?”

“Something chivalrous to defend your honor,” he mumbled, his lips unrelenting on your shoulder as he pulled your shirt down to expose it.

“I guess I should thank you properly, then? My knight in shining armor?”

He lifted his head, grinning, “If you insist.”

#homelander x reader#homelander x you#the boys x reader#the boys amazon#the boys tv#the boys#homelander

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gender and Etiquette

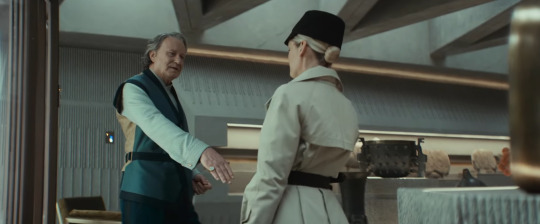

This confrontation between Luthen and Dedra is fascinating for many reasons, and I can't help but zero in on this handshake every time. To me, it holds deep gendered coding.

At least in the West, offering your hand palm-down in greeting comes straight out of (historical) women's social script. It's a very feminine gesture in the eye of the observer. As for Dedra taking Luthen's hand palm-up and holding it - it's the "man's part" of this interaction, and what follows in men's social script would be a feigned kiss to the woman's knuckles. This is what that hand configuration, downturned palm on upturned palm, is for.

Obviously, a hand kiss is not what's happening here. No illusions about that. It all just looks like the lead-up to one. But isn't it so INTERESTING that Luthen is the one performing the traditionally feminine part of the script while Dedra is performing the masculine one without missing a beat? In this sexist Imperial society, to boot? It implies that there is some sort of social script not just for the interaction of women and men, but for the interaction of gender on a spectrum.

Dedra isn't masc, but she reacts without a hitch to a feminine gesture by Luthen. And we've seen her shake hands with other people before - all regular handshakes where the thumb faces up instead of the palm. A "gender neutral" handshake, if you will. I might be reading too much into this, but it's giving me a taste of the gender-related nuance I've been wanting to see from Star Wars and I am Thinking about it.

Feel free to add on to this, I'd love to hear if I'm tripping or if other people are also seeing something here 👀

Grimy ass gif of the whole interaction bc I feel like the pictures don't do it full justice. There might also be a class aspect to this whole charade, with Luthen ostensibly being upper crust and Dedra being... not quite that.

#andor#star wars#luthen rael#dedra meero#luthen is so damn interesting with regards to gender performance ig#the aristocratic flamboyant swishy facade he keeps up. definitely intentionally fruity on his part#and then his more ”traditionally masculine” side. which also breaks with tradition so often#his whole relationship to kleya ecemplifies those breaks so well#ugh what a fascinating guy#and then there's dedra!! her gender performance (or lack of it) is also so so so tasty i wish i had time to dissect it all#PLEASE let me hear your thoughts guys

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

the most flamboyantly "gay-looking" man/woman you can think of...

has at least one person looking exactly like them who is straight.

because gay isn't an aesthetic. gay isn't a look. it's a sexuality you're born with. and femininity in men, masculinity in women, doesn't make you more gay or less gay or whatever. that's gender roles babey! that's what the left is claiming it's fighting against!

you can make jokes about looking like a lesbian or whatever. but i could wear the most hyperfem shit ever and still look lesbian. bc i am lesbian. whatever i do, whatever i wear, however i act, is lesbian coded. because i'm a lesbian. i'm just expanding what it means to be a lesbian by being myself. and feminine straight men and masculine straight women are expanding what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman, which is a win for feminism and fighting strict gender norms. it helps everyone. we should make the boxes of man & woman bigger, funkier, cooler. we shouldn't assume it's "queerifying" manhood or womanhood when it's just making them be neutral. it means that if you're a human being you can do WHATEVER THE HELL YOU WANT and still be whatever gender/sex/etc you are. you aren't any less of a straight man for being feminine. that's what the patriarchy wants. the rightwing hated so-called metrosexuals and goths and emos etc because of it. and you aren't any less of a straight woman for not being feminine. and you being masculine, or unfeminine, is the most natural thing in the world. it's just you being your natural self without makeup, shaving, tight clothes, etc. but some ofc find pride in being masc too. that doesn't make you more likely to be gay. it doesn't make you less womanly. there is no way that exists to make you less womanly bc it's the most neutral, irrelevant thing about you. it's a "duh!" type of thing that you don't need to care about. you don't need to do fuckall to be "good" at womanhood. and a dude can wear and do and say whatever he wants and be secure in being a guy and not being trans or gay or bi

masculinity in women doesn't make them more likely to be gay. femininity in men doesn't make them more likely to be gay.

gays & feminists have been trying to fight this shit for decades. yet mainstream qweer communities keep reinforcing that rhetoric!!! it's so fucking exhausting. there's no way to look, sound, act etc gay. there's literally none outside of saying you're into other men or other women, and being lovelydovey or having sex with other men or other women. that's it. that's literally it. free yourself from gender boxes!!!

412 notes

·

View notes

Text

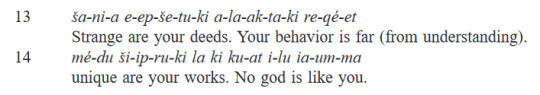

Nonconformity, ambiguity, fluidity and misinterpretation: on the gender of Inanna (and a few others)

This article wasn’t really planned far in advance. It started as a response to a question I got a few weeks ago:

However, as I kept working on it, it became clear a simple ask response won’t do - the topic is just too extensive to cover this way. It became clear it has to be turned into an article comprehensively discussing all major aspects of the perception of Inanna’s gender, both in antiquity and in modern scholarship. In the process I’ve also incorporated what was originally meant as a pride month special back in 2023 (but never got off the ground) into it, as well as some quick notes on a 2024 pride month special that never came to be in its intended form, as I realized I would just be repeating what I already wrote on wikipedia.

To which degree can we speak of genuine fluidity or ambiguity of Inanna’s gender, and to which of gender non-conforming behavior? Which aspects of Inanna’s character these phenomena may or may not be related to? What is overestimated and what underestimated? What did Neo-Assyrian kings have in common with medieval European purveyors of Malleus Maleficarum? Is a beard always a type of facial hair? Why should you be wary of any source which calls gala “priests of Inanna”?

Answers to all of these questions - and much, much more (the whole piece is over 19k words long) - await under the cut.

Zeus is basically Tyr: on names and cognates

The meaning of a theonym - the proper name of a deity - can provide quite a lot of information about its bearer. Therefore, I felt obliged to start this article with inquiries pertaining to Inanna’s name - or rather names. I will not repeat how the two names - Inanna and Ishtar - came to be used interchangeably; this was covered on this blog enough times, most recently here. Through the article, I will consistently refer to the main discussed deity as Inanna for the ease of reading, but I’d appreciate it if you read the linked explanation for the name situation before moving forward with this one.

Sumerian had no grammatical gender, and nouns were divided broadly into two categories, “humans, deities and adjacent abstract terms” and “everything else” (Ilona Zsolnay, Analyzing Constructs: A Selection of Perils, Pitfalls, and Progressions in Interrogating Ancient Near Eastern Gender, p. 462; Piotr Michalowski, On Language, Gender, Sex, and Style in the Sumerian Language, p. 211). This doesn’t mean deities (let alone humans) were perceived as genderless, though. Furthermore, the lack of grammatical masculine or feminine gender did not mean that specific words could not be coded as masculine or feminine (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471; one of my favorite examples are the two etymologically unrelated words for female and male friends, respectively malag and guli).

While occasionally doubts are expressed regarding the meaning of Inanna’s name, most authors today accept that it can be interpreted as derived from the genitive construct nin-an-ak - “lady of heaven” (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 104). The title nin is effectively gender neutral (Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 6) - it occurs in names of male deities (Ningirsu, Ninurta, Ninazu, Ninagal, Nindara, Ningublaga...), female ones (Ninisina, Ninkarrak, Ninlil, Nineigara, Ninmug…), deities whose gender shifted or varied from place to place or from period to period (Ninsikila, Ninshubur, Ninsianna…) and deities whose gender cannot be established due to scarcity of evidence (mostly Early Dynastic oddities whose names cannot even be properly transcribed). However, we can be sure that Inanna’s name was regarded as feminine based on its Emesal form, Gašananna (Timothy D. Leonard, Ištar in Ḫatti: The Disambiguation of Šavoška and Associated Deities in Hittite Scribal Practice, p. 36).

The matter is a bit more complex when it comes to the Akkadian name Ishtar. In contrast with Sumerian, Akkadian, which belongs to the eastern branch of the family of Semitic languages, had two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine, though the gender of nouns wasn’t necessarily reflected in verbal forms, suffixes and so on (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 472-473). In contrast with the name Inanna, the etymology of the Akkadian moniker is less clear. The root has been identified, ˤṯtr, but its meaning is a subject of a heated debate (Aren M. Wilson-Wright, Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation of a Goddess in the Late Bronze Age, p. 22-23; the book is based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, which can be read here). Based on evidence from the languages from the Ethiopian branch of the Semitic family, which offer (distant) cognates, Wilson-Wright suggests it might have originally been an ordinary feminine (but not marked with an expected suffix) noun meaning “star” which then developed into a theonym in multiple languages (Athtart…, p. 21) She tentatively suggests that it might have referred to a specific celestial body (perhaps Venus) due to the existence of a more generic term for “star” in most Semitic languages, which must have developed very early (p. 24). Thus the emergence of Ishtar would essentially parallel the emergence of Shamash, whose name is in origin the ordinary noun for the sun (p. 25). This seems like an elegant solution, but as pointed out by other researchers some of the arguments employed might be shaky, so it’s best to remain cautious about quoting Wilson-Wright’s conclusions as fact, even if they are more sound than some of the older, largely forgotten, proposals (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 40-41).

In addition to uncertainties pertaining to the meaning of the root ˤṯtr, it’s also unclear why the name Ishtar starts with an i in Akkadian, considering cognate names of deities from other cultures fairly consistently start with an a. The early Akkadian form Eštar isn’t a mystery - it reflects a broader pattern of phonetic shifts in this language, and as such requires no separate inquiry, but the subsequent shift from e to i is almost unparalleled. Wilson-Wright suggests that it might have been the result of contamination with Inanna, which seems quite compelling to me given that by the second millennium BCE the names had already been interchangeable for centuries (Athtart…, p. 18).

As for grammatical gender, in Akkadian (as well as in the only other language from the East Semitic branch, Eblaite), the theonym Ishtar lacks a feminine suffix but consistently functions as grammatically feminine nonetheless. I got a somewhat confusing ask recently, which I assume was the result of misinterpretation of this information as applying to the gender of the bearer of the name as opposed to just grammatical gender of the name itself:

Occasional confusion might stem from the fact that in the languages from the West Semitic family (like ex. Ugaritic or Phoenician) there’s no universal pattern - in some of them the situation looks like in Akkadian, in some cognates without the feminine suffix refer to a male deity, furthermore goddesses with names which are cognate but have a feminine suffix (-t; ex. Ugaritic Ashtart) added are attested (Athtart…, p. 16).

In Akkadian a form with a -t suffix (ištart) doesn’t appear as a theonym, only as the generic word, “goddess” - and it seems to have a distinct etymology, with the -t as a leftover from plural ištarātu (Athtart…, p. 18). The oldest instances of a derivative of the theonym Ishtar being used as an ordinary noun, dated to the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800 BCE), spell it as ištarum, without such a suffix (Goddess in Context…, p. 80). As a side note, it’s worth pointing out that both obsolete vintage translations and dubious sources, chiefly online, are essentially unaware of the existence of any version of this noun, which leads to propagation of incorrect claims about equation of deities (Goddesses in Context…, p. 82).

It has been argued that a further form with the -t suffix, “Ishtarat”, might appear in Early Dynastic texts from Mari, but this might actually be a misreading. This has been originally suggested by Manfred Krebernik all the way back in 1984. He concluded the name seems to actually be ba-sùr-ra-at (Baśśurat; something like “announcer of good news”; Zur Lesung einiger frühdynastischer Inschriften aus Mari, p. 165). Other researchers recently resurrected this proposal (Gianni Marchesi and Nicolo Marchetti, Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, p. 228; accepted by Dominique Charpin in a review of their work as well). I feel it’s important to point out that nothing really suggested that the alleged “Ishtarat” had much to do with Ishtar (or Ashtart, for that matter) in the first place. The closest thing to any theological information in the two brief inscriptions she appears in is that she is listed alongside the personified river ordeal, Id, in one of them. Marchesi and Marchetti suggest they form a couple (Royal Statuary…, p. 228); in absence of other evidence I feel caution is necessary. I’m generally wary of asserting deities who appear together once in an oath, greeting or dedicatory formula are necessarily a couple when there is no supplementary evidence. Steve A. Wiggins illustrated this issue well when he rhetorically asked if we should treat Christian saints the same way, which would lead to quite thrilling conclusions in cases like the numerous churches named jointly after St. Andrew and St. George and so on (A Reassessment of Asherah With Further Considerations of the Goddess, p. 101).

Even without Ishtarat, the Mariote evidence remains quite significant for the current topic, though. There’s a handful of third millennium attestations of a deity sometimes referred to as “male Ishtar” (logographically INANNA.NITA; there’s no ambiguity thanks to the second logogram) in modern publications - mostly from Mari. The problem is that this is most likely a forerunner of Ugaritic Attar, as opposed to a male form of the deity of Uruk/Zabalam/Akkad/you get the idea (Mark S. Smith, The God Athtar in the Ancient Near East and His Place in KTU 1.6 I, esp. p. 629; note that the deity with the epithet Sarbat is, as far as I know, generally identified as female though).

Ultimately there is no strong evidence for Attar being associated with Inanna (his Mesopotamian counterpart in the trilingual list from Ugarit is Lugal-Marada) or even with Ashtart (Smith tentatively proposes the two were associated - The God Athtar.., p. 631 - but more recently in ‛Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts he ruled it out, p. 36-37) so he’s not relevant at all to this topic. Cognate name =/= related deity, least you want to argue Zeus is actually Tyr; the similarly firmly male South Arabian ˤAṯtar is even less relevant (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 13). Smith goes as far as speculating the male cognates might have been a secondary development, which would render them even more irrelevant to this discussion (‛Athtart in Late…, p. 35).

There are also three Old Akkadian names which might refer to a masculine deity based on the form of the other element (Eštar-damqa, “E. is good”, Eštar-muti “E. is my husband”, and Eštar-pāliq, “E. is a harp”), but they’re an outlier and according to Wilson-Wright might be irrelevant for the discussion of the gender of Ishtar and instead refer to a deity with a cognate name from outside Mesopotamia (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 22).

There’s also a possible isolated piece of evidence for a masculine deity with a cognate name in Ebla. Eblaite texts fairly consistently indicate that Inanna’s local counterpart Ašdar was a female deity. In addition to the equivalence between them attested in a lexical list, her main epithet, Labutu (“lioness”) indicates she was a feminine figure. However, Alfonso Archi argues that in a single case the name seems to indicate a god, as they are followed by an otherwise unattested “spouse” (DAM-sù), Datinu (Išḫara and Aštar at Ebla: Some Definitions, p. 16). The logic behind this is unclear to me and no subsequent publications offer any explanations so far. It might be worth noting that the Eblaite pantheon seemingly was able to accommodate two sun deities, one male and one female, so perhaps this is a similar situation.

It should also be noted that the femininity of Ishtar despite the lack of a feminine suffix in her name is not entirely unparalleled - in addition to Ebla, in areas like the Middle Euphrates deities with cognate names without the -t suffix might not necessarily be masculine, even when they start with a- and not i- like in Akkadian. In some cases the matter cannot be solved at all - there is no evidence regarding the gender of Aštar of the Stars (aš-tar MUL) from Emar, for instance. Meanwhile Aštar of Ḫaši and Aštar-ṣarbat (“poplar Aštar”) from the same site are evidently feminine (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 106). At least in the last case that’s because the name actually goes back to the Akkadian form, though (p. 85).

To sum up: despite some minor uncertainties pertaining to the Akkadian name, there’s no strong reason to suspect that any greater degree of ambiguity is built into either Inanna or Ishtar - at least as far as the names alone go. The latter was even seen as sufficiently feminine coded to serve as the basis for a generic designation of goddesses.

Obviously, there is more to a deity than just the sum of the meanings of their names. For this reason, to properly evaluate what was up with Inanna’s gender it will be necessary to look into her three main roles: these of a war deity, personification of Venus and love deity.

Masculinity, heroism and maledictory genderbening: the warlike Inanna

An Old Babylonian plaque depicting armed Inanna (wikimedia commons)

Martial first, marital second?

War and other related affairs will be the first sphere of Inanna’s activity I’ll look into, since it feels like it’s the one least acknowledged online and in various questionable publications. Ilona Zsolnay points out that this even extends to serious scholarship to a degree, and that as a result her military side is arguably understudied (Ištar, Goddess of War, Pacifier of Kings: An Analysis of Ištar’s Martial Role in the Maledictory Sections of the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, p. 389). The oldest direct evidence for the warlike role of Inanna are Early Dynastic theophoric names such as Inanna-ursag, “Inanna is a warrior”. Further examples are provided by a variety of both Sumerian and Akkadian sources from across the second half of the third millennium BCE. This means it’s actually slightly older than the first evidence for an association with love and eroticism, which can only be dated with certainty to the Old Akkadian period when it is directly mentioned for the first time, specifically in love incantations (Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Inanna and Ishtar in the Babylonian World, p. 336).

Deities associated with combat were anything but uncommon in Mesopotamia. There was no singular war god - Ninurta, Nergal, Zababa, Ilaba, Tishpak and an entire host of other figures, some recognized all across the region, some limited to one specific area or even just a single city, shared a warlike disposition. Naturally, the details could vary - Ninurta was essentially an avenger restoring order disturbed by supernatural threats, Nergal was a war god because he was associated with just about anything pertaining to inflicting death, and so on.

All the examples I’ve listed are male, but similar roles are also attested for multiple goddesses, not just Inanna. Those include closely related deities like Annunitum or Belet-ekallim, most of her foreign counterparts, the astral deity Ninisanna (more on this figure later), but also firmly independent examples like Ninisina and the Middle Euphrates slash Ugaritic Anat (Ilona Zsolnay, Do Divine Structures of Gender Mirror Mortal Structures of Gender?, p. 114).

The god list An = Anum preserves a whole series of epithets affirming Inanna’s warlike character - Ninugnim, “lady of the army”; Ninšenšena, “lady of battle”; Ninmea, “lady of combat”; Ninintena, “lady of warriorhood” (tablet IV, lines 20-23; Wilfred G. Lambert and Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p.162). It is also well represented in literary texts. She is a “destroyer of lands” (kurgulgul) in Ninmesharra, for instance (Markham J. Geller, The Free Library Inanna Prism Reconsidered, p. 93).

At least some of the terms employed to describe Inanna in other literary compositions were strongly masculine-coded, if not outright masculine. The poem Agušaya characterizes her as possessing “manliness” (zikrūtu) and “heroism” (eṭlūtu; this word can also refer to youthful masculinity, see Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471) and calls her a “hero” (qurādu). Another example, a hymn dated to the reign of Third Dynasty of Ur or First Dynasty of Isin opens with an incredibly memorable line - “O returning manly hero, Inanna the lady (...)” (or, to follow Thorkild Jacobsen’s older translation, which involves some gap filling - “O you Amazon, queen—from days of yore, paladin, hero, soldier”; The Free Library… p. 93).

A little bit of context is necessary here: while “heroism” might seem neutral to at least some modern readers, in ancient Mesopotamia it was seen as a masculine trait (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 392-393). It’s worth noting that eṭlūtum, which you’ve seen translated as “heroism” above can be translated in other context as “youthful masculinity” (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471). On the other hand, while zikrūtu is derived from zikāru, “male”, it might refer both straightforwardly to masculinity and more abstractly to heroism (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 397).

However, the same hymn which calls Inanna a “manly hero” refers to her with a variety of feminine titles like nugig. There’s even an Emesal gašan (“lady”) in there, you really can’t get much more feminine than that (The Free Library… p. 89). On top of that, about a half of the composition is a fairly standard Dumuzi romance routine (The Free Library… p. 90-91; more on what that entails later, for now it will suffice to say that not gender nonconformity).

This is a recurring pattern, arguably - Agušaya, where masculine traits are attributed to Inanna over and over again, still firmly refers to her as a feminine figure (“daughter”, “goddess”, “queen”, “princess”, “mistress”, “lioness” and so on; Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: an Anthology of Akkadian Literature, p. 160 and passim). In other words, the assignment of a clearly masculine sphere of activity and titles related to it doesn’t really mean Inanna is not presented as feminine in the same compositions.

How to explain this phenomenon? In Mesopotamian thought both femininity and masculinity were understood as me, ie. divinely ordained principles regulating the functioning of the cosmos. In modern terms, these labels as they were used in literary texts arguably had more to do with gender and gender roles than strictly speaking with biological sex (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 391-392). Ilona Zsolnay on this basis concludes that Inanna, while demonstrably regarded as a feminine figure, took on a masculine role in military context (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 401). This is hardly an uncommon view in scholarship (The Free Library…, p. 93; On Language…, p. 243).

In other words, it can be argued that when the lyrical voice in Agušaya declares that “there is a certain hero, she is unique” (i-ba-aš-ši iš-ta-ta qú-ra-du; Before the Muses…, p. 98) the unique quality is, essentially, that Inanna fulfills a strongly masculine coded role - that of a “hero”, understood as a youthful, aggressive masculine figure - despite being female.

It should be noted that the ideal image of a person characterized by youthful masculinity went beyond just warfare, or abstract heroic adventures, though. The Song of the Hoe indicates that willingness to perform manual work in the fields was yet another aspect of it (Ilona Zsolnay, Gender and Sexuality: Ancient Near East, p. 277). This, as far as I know, was never attributed to Inanna.

Furthermore, the sort of youthful, aggressive masculinity we’re talking about here was regarded as something fleeting and temporary for the most part (at least when it came to humans; deities are obviously a very different story), and a very different image of male gender roles emerges from texts such as Instruction of Shuruppak, which extol a peaceful, reserved demeanor and the ability to provide for one’s family as masculine virtues instead (Gender and Sexuality…, p. 277-278). It might be worth pointing out that Sumerian outright uses two different terms to designate “youthful” (namguruš) and “senior” (namabba) masculinity (Gender and Sexuality…, p. 275); the general term for masculinity, namnitah, is incredibly rare in comparison (Gender and Sexuality…, p. 276-277).

It needs to be pointed out that a further Sumerian term sometimes translated as “manliness” - šul, which occurs for example in the hymn mentioned above - might actually be gender neutral; in addition to being used to describe mortal young men and Inanna, it was also applied as an epithet to the goddess Bau, who demonstrably was not regarded as a masculine figure; she didn’t even share Inanna’s warlike character (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471). Perhaps the original nuance simply escapes us - could it be that šul was not strictly speaking masculinity, but some more abstract quality which was simply more commonly associated with men?

In any case, it’s hard to argue that Inanna really encompasses the entire concept of masculinity as the Mesopotamians understood it. At the same time, it is impossible to deny that she was portrayed as responsible for - and enthusiastically engaged in - spheres of activity which were seen as firmly masculine, and could accordingly be described with terms associated with them. Therefore, it would be more than suitable to describe her as gender nonconforming - at least when she was specifically portrayed as warlike.

Perhaps Dennis Pardee was onto something when he completely sincerely described Anat, who despite being firmly a female figure similarly engaged in masculine pursuits (not only war, but also hunting) as a “tomboy goddess” (Ritual and Cult at Ugarit, p. 274).

These observations only remain firmly correct as long as we assume that gender roles are a concept fully applicable to deities, of course - I’ll explore in more detail later whether this was necessarily true.

Royal curses and legal loopholes

A different side of Inanna as a war deity which nonetheless still has a lot to do with the topic of this article comes to the fore in curse formulas from royal inscriptions. Their contents are not quite as straightforward as imploring her to personally intervene on the battlefield. Rather, she was supposed to make the enemy unable to partake in warfare properly (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 390). Investigating how this process was imagined will shed additional light on how the Mesopotamians viewed masculinity, and especially the intersection between masculinity and military affairs.

The formulas under discussion start to appear in the second half of the second millennium BCE, with the earliest example identified in an inscription of the Middle Assyrian king Tukultī-Ninurta I (Gina Konstantopoulos, My Men Have Become Women, and My Women Men: Gender, Identity, and Cursing in Mesopotamia, p. 363). He implored the goddess to punish his enemies by turning them into women (zikrūssu sinnisāniš) - or rather, by turning their masculinity into femininity, or at the very least some sort of non-masculine quality. The first option was the conventional translation for a while, but sinništu would be used instead of the much more uncommon sinnišānu if it was that straightforward. Interpreting it as “femininity” would parallel the use of zikrūti, “masculinity”, in place of zikaru, “man”.

There are two further possible alternatives, which I find less plausible myself, but which nonetheless need to be discussed. One is that sinnišānu designated a specific class of women. Furthermore, there is also some evidence - lexical list entry from ḪAR.GUD, to be specific - that sinnisānu might have been a synonym of assinnu, a type of undeniably AMAB, but possibly gender nonconforming, cultic performer (in older literature erroneously translated as “eunuch” despite lack of evidence; the second most beloved vintage baseless translation for any cultic terms after “sacred prostitute”, an invention of Herodotus), in which case the curse would involve something like “changing his masculinity in the manner of a sinnisānu” (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 394-396). However, Zsolnay herself subsequently published a detailed study of the assinnu, The Misconstrued Role of the assinnu in Ancient Near Eastern Prophecy, which casts her earlier proposal into doubt, as the perception of the assinnu as a figure lacking conventional masculinity might be erroneous. I’ll return to this point later. For now, it will suffice to say that on grammatical grounds and due to parallels in other similar maledictions, “masculinity into femininity” seems to be the most straightforward to me in this case.

The “genderbending” tends to be mentioned alongside the destruction of one’s weapons (My Men Have…, p. 363). This is not accidental - martial prowess, “heroism” and even the ability to bear weapons were quintessential masculine qualities; a man deprived of his masculinity would inevitably be unable to possess them. The masculine coding of weaponry was so strong that an erection could be metaphorically compared to drawing a bow (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 395).

Zsolnay points out the reversal of gender in curses is also coupled with other reversals: Inanna is also supposed to “establish” (liškun) the defeat (abikti) of the target of the curses - a future king who fails to uphold his duties - which constitutes a reversal of an idiom common in royal inscriptions celebrating victory (abikti iškun). The potential monarch will also be unable to face the enemy as a result of her intervention - yet again a reversal of a mainstay of royal declarations. The majesty and heroism of a king were supposed to scare enemies, who would inevitably prostrate themselves when faced by him on the battlefield (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 396-397).

It is safe to say the goal of invoking Inanna in the discussed formulas was to render the target powerless. (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 396; My Men Have…, p. 366). Furthermore, they evoke a fear widespread in cuneiform sources, that of the loss of potency, which sometimes took forms akin to Koro syndrome or the infamous penis theft passages from Malleus Maleficarum (My Men Have…, p. 367). It is worth noting that male impotence could specifically be described as being “like a woman” (kīma sinništi/GIM SAL; Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 395).

Gina Konstantopoulos argues that references to Inanna “genderbening” others occur in a different context in a variety of literary texts, for example in the Epic of Erra, where they’re only meant to highlight the extent of her supernatural ability. She also suggests that more general references to swapping left and right sides around, for example in Enki and the World Order, are further examples, as they “echo(...) the language of birth incantations” which ritually assigned the gender role to a child (My Men Have…, p. 368). She also sees the passage from the Epic of Gilgamesh describing the fates of various individuals who crossed her path and ended up transformed into animals as a result as a more distant parallel of the curse formulas (My Men Have…, p. 369). However, it needs to be pointed out this sort of shapeshifting is almost unparalleled in Mesopotamian literature (Frans Wiggermann, Hybrid creatures A. Philological. In Mesopotamia, p. 237), and none of the few examples involve a change of gender. The fact that the "genderbending" passages generally reflect a fear of loss of agency (especially on the battlefield) or potency, and by extension of independence tied to masculine gender roles, explains why they virtually never describe the opposite scenario, a mortal woman being placed in a masculine role through supernatural means as punishment (My Men Have…, p. 370). It might be worth pointing out that a long sequence of seemingly contradictory duties involving reversals is also ascribed to Inanna in a particularly complex Old Babylonian hymn (Michael P. Streck, Nathan Wasserman, The Man is Like a Woman, the Maiden is a Young Man. A new edition of Ištar-Louvre (Tab. I-II), p. 2-3). It also contains a rare case of bestowing masculine qualities upon women: “the man is like a woman, the maiden is like a young man” (zikrum sinništeš ardatu eṭel; The Man is Like…, p. 5). However, the context is not identical to the “genderbening” curses. The text is agreed to describe a performance during a specific festival. Other passages explicitly refer to crossdressing and rituals themed around reversal (šubalkutma šipru, "behavior is turned upside down"; The Man is Like…, p. 6). Furthermore, grammatical forms of verbs do not indicate a full reversal of gender (The Man is Like…, p. 31). Overall, I agree with Timothy D. Leonard’s cautious remark that in this context only religiously motivated temporary reversal of gender roles occurs, and we cannot use the passage to make far reaching conclusions about the participants’ identity (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 298).

It’s important to bear in mind that a performance involving crossdressing won’t necessarily involve people who are otherwise gender nonconforming, and it doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the sexuality of the performer. While I typically avoid bringing up parallels from other cultures and time periods as evidence, I feel like this is illustrated quite well by the case of shirabyōshi, a type of female performer popular in Japan roughly from the second half of the Heian period to the late Kamakura period.

A 20th century depiction of a shirabyōshi (wikimedia commons)

They performed essentially in male formal wear, and with swords at their waists; their performance was outright called a “male dance” (Roberta Strippoli, Dancer, Nun, Ghost, Goddess. The Legend of Giō and Hotoke in Japanese Literature, Theater, Visual Arts, and Cultural Heritage, p. 28). Genpei jōsuiki nonetheless states that famous shirabyōshi were essentially the Japanese answer to the most famous historical Chinese beauties like Wang Zhaojun or Yang Guifei (Dancer, Nun…, p. 27-28). In other words, while the shirabyōshi crossdressed, they were simultaneously held to be paragons of femininity.

Putting crossdressing aside, it’s worth noting women taking masculine roles are additionally attested in legal context in ancient Mesopotamia, though only in an incredibly specific scenario. A man who lacked male heirs could essentially legally declare his daughter a son, so that she would be able to have the privileges as a man would with regards to inheritance. For example, in a text from Emar a certain mr. Aḫu-ṭāb formally made his daughter Alnašuwa his heir due to having no other descendants, and explained that as a result she will have to be “both male and female” (NITA ù MUNUS) - effectively both a son and a daughter - to keep the process legitimate. Once Alnašuwa got married, her newfound status as a son of her father was legally transferred to her husband, though. Evidently no supernatural powers were involved at any stage, only an uncommon, but fully legitimate, legal procedure (My Men Have…, p. 370-372). It should be noted that when male by proxy, Alnašuwa was explicitly not expected to perform any military roles - her father only placed such an exception on potential grandsons (My Men Have…, p. 370). Therefore, the temporary masculine role she was granted was arguably not the same as the sort of masculinity curses were supposed to take away, or the sort Inanna could claim for herself to a degree.

Luminous beards and genderfluid planets: the astral Inanna (and her peers)

A standard Mesopotamian depiction of the planet Venus (Dilbat) on a late Kassite boundary stone (wikimedia commons)

Male in the morning, female in the evening (or the other way round)?

While the inquiry into Inanna’s military aspect revealed a fair amount of evidence for gender nonconformity, it would be disingenuous on my part to end the article on just that. A slightly different phenomenon is documented with regards to her astral side - or perhaps with regards to the astral side of multiple deities, to be more precise.

To begin with, in Mesopotamian astrology Venus (Dilbat) was one of the two astral bodies which were described as possessing two genders, the other being Mercury (Erica Reiner, Astral Magic in Babylonia, p. 6; interestingly, it doesn’t seem any deity associated with Mercury acquired this characteristic unless you want to count a possible late case from outside Mesopotamia). The primary sources indicate that this reflected the fact Venus is both the morning star and the evening star, though there was no agreement between ancient astronomers which one of them was feminine and which masculine (Ulla Koch-Westenholz, Mesopotamian Astrology. An Introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian Celestial Divination, p. 40). We even have a case of a single astrologer, a certain Nabû-ahhe-eriba, alternating between both options in his personal letters (p. 126). It needs to be pointed out that while some interest in stars and planets might already be attested in Early Dynastic sources, its scope was evidently quite limited and astrology didn’t develop yet (Mesopotamian Astrology…, p. 32). No astrological texts predate the Old Babylonian period, and most of the early ones are preoccupied with the moon (p. 36-37), though the earliest evidence for astrological interest in Venus are roughly contemporary with them (p. 40). Astronomical observations of this planet were certainly already conducted for divinatory purposes during the reign of Ammisaduqa, and by the seventh century BCE experts were well familiar with its cycle and made predictions on this basis (p. 126).

Inanna’s association with Venus predates the dawn of astrology by well over a millennium. It likely goes back all the way up to the Uruk period - if not earlier, but that sort of speculation is moot because you can’t talk about Mesopotamian theology with no textual sources, and these are fundamentally not something available before the advent of writing. The earliest evidence are archaic administrative texts which separately record offerings for Inanna hud, “Inanna the morning” and Inanna sig, “Inanna the evening” (Inanna and Ishtar…, p. 334-335). However, it is impossible to tell if this was already reflected in any sort of ambiguity or fluidity of gender. It also needs to be noted the archaic text records two more epithets, Inanna NUN, possibly “princely Inanna” (p. 334; this is actually the single oldest one) and Inanna KUR, possibly a forerunner of later title ninkurkurra, “lady of the lands” (p. 335). Therefore, Inanna was arguably already more than just a deity associated with Venus.

It’s up for debate to which degree an astral body was seen as identical with the corresponding deity in later periods (Spencer J. Allen, The Splintered Divine. A Study of Ištar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East, p. 41-42). There is evidence that Inanna and the planet Venus could be viewed as separate, similarly to how the moon observed in the sky could be treated as distinct from the moon god Sin (p. 40). The most commonly cited piece of evidence is that astrological texts fairly consistently employ the name Dilbat to refer to the planet instead of Inanna’s name or one of the logograms used to represent it, like the numeral 15 (p. 42).

Regardless of these concerns, one specific tidbit pertaining to astrological comments on Venus is held as particularly important for possible ambiguity or fluidity of Inanna’s gender, and even lead to arguments that masculine depictions might be out there: the planet can be described as bearded (Astral Magic…, p. 6). Omens attesting this are most notably listed in the compendium Iqqur īpuš (Erica Reiner, David Pingree, Babylonian Planetary Omens vol. 3, p. 10-11). it should be noted that the planet is referred to only as Dilbat in this context (see ex. Babylonian Planetary…, p. 105 for an example). I’m only aware of two texts where this feature is transferred to the corresponding deity: the syncretic hymn to Nanaya and Ashurbanipal’s hymn to Ishtar of Nineveh. Is the beard really a beard, though? Not necessarily, as it turns out.

The passage from the hymn of Ashurbanipal has been recently discussed by Takayoshi M. Oshima and Alison Acker Gruseke (She Walks in Beauty: an Iconographic Study of the Goddess in a Nimbus, p. 62-63). They point out that ultimately there are no certain iconographic representations of bearded Ishtar. There are a few proposed ones on cylinder seals but this is a minority position relying on doubtful exegesis of every strand of hair in sight; no example has anything resembling the “classic” Mesopotamian beard. I’ll return to this problem in a bit.

In any case, the authors of the aforementioned paper argue the key to interpreting the passage is the fact that the reference to the beard (or rather beards in the plural) occurs in an enumeration of strictly astral, luminous characteristics, like being “clothed in brilliance” (namrīrī ḫalāpu). Furthermore, they identify a parallel in the Great Hymn to Shamash: the rays of the sun are described as “beards” (ziqnāt), and occur in parallel with “splendor” (šalummatu) and “lights” (namrīrū). Therefore, they assume the “beard” might be a metaphorical term for a ray of light, rather than facial hair. This would match actually attested depictions - in the first millennium BCE, especially in Assyria, images of a goddess surrounded by rays of light or a large halo of sorts are very common.

A goddess surrounded by a halo on a Neo-Assyrian seal (wikimedia commons)

Perhaps most importantly, this interpretation is also confirmed by the astronomical texts which kickstarted the discussion. The phrase ziqna zaqānu, “to have a beard”, is explained multiple times as reflection of an unusual luminosity when applied to Venus. The authors additionally argue that it is possible the use of the term “beard” was originally tied to the triangular portions of the emblems of Inanna and her twin (which indeed represent the luminosity of Venus and the sun) to explain why a plurality of “beards” is relatively common in the discussed descriptions (p. 64).

As I said before, the second example is a hymn to Nanaya. It’s easily one of my favorite works of Mesopotamian literature, and a few years ago it kickstarted my interest in its “protagonist”, but tragically most of it is completely irrelevant to this article. The gist of it is fairly simple: the entire composition is written in first person, and in each strophe Nanaya claims the prerogatives of another deity before reasserting herself: “still I am Nanaya” (Goddesses in Context…, p. 116-117). The “borrowed” attributes vary from abstract cosmic powers to breast size. The deities they are linked with range from the most major members of the pantheon (Inanna, Gula, Ishara, Bau…) through spouses of major deities (Shala, Damkina…) to obscure oddities (Manzat, the personified rainbow); there’s even one who’s otherwise entirely unknown, Šuluḫḫītum (for a full table see Erica Reiner’s A Sumero-Akkadian Hymn of Nanâ, p. 232).

As expected, the strophe relevant to the current topic is the one focused on Inanna, in which Nanaya proudly exclaims “I have a beard (ziqna zaqānu) in Babylon”, in between claiming to have “heavy breasts in Daduni” (Reiner notes this is not actually an attested attribute of Inanna, and suggests the line might be a pun on the name of the city mentioned in it, Daduni, and the word dādu) and appropriating Inanna’s family tree for herself (A Sumero-Akkadian…, p. 233).

A possible late depiction of Nanaya (wikimedia commons)

It needs to be stressed that Nanaya’s gender shows no signs of ambiguity anywhere; quite the opposite, she was the “quintessence of womanhood“ (Olga Drewnowska-Rymarz, Mesopotamian Goddess Nanāja, p. 156). I would argue the most notable case of something along the lines of gender nonconformity in a source focused on her occurs in the sole known example of a love poem starring her and her sparsely attested Old Babylonian spouse Muati.

Muati is asked to intercede with Nanaya on behalf of a petitioner (Before the Muses…, p. 160), which usually was the role performed of the wife of a major male deity (or by Ninshubur in Inanna’s case; Goddesses in Context…, p. 273). Sadly, despite recently surveying most publications mentioning Muati I haven’t found any substantial discussion of this unique passage, and I’m not aware of any parallels involving other couples where the wife was a more important deity than the husband (like Ninisina and Pabilsag).

A further issue for the beard passage is that Nanaya had no connection to Venus to speak of - she could be described as luminous, but she was only compared to the sun, the moon, and unspecified stars (Mesopotamian Goddess Nanāja, p. 153-155).

Given that the hymn most likely dates to the early first millennium BCE (Goddesses in Context…, p. 116), yet another problem for the older interpretation is that the city of Babylon at this point in time is probably the single worst place for seeking any sort of gender ambiguity when it comes to Inanna.

After the end of the Kassite period, Babylon became the epicenter of Marduk-centric theological ventures which famously culminated in the composition of Enuma Elish. What is less well known is that as a part of the same process, attempts were made to essentially fuse Bēlet-Bābili (“lady of Babylon”) - the main (but not only) local form of Inanna, regarded as distinct from Inanna of Uruk (the “default” Inanna) - with Zarpanitu (The Pantheon…, p. 75-76). Zarpanitu was effectively the definition of an indistinct spouse of another deity - there’s not much to say about her character other than that she was Marduk’s wife (Goddesses in Context…, p. 92-93). Accordingly, it is hard to imagine that the contemporary “lady of Babylon” would be portrayed as bearded.

During the reign of Nabu-shuma-ishkun in the eighth century BCE an attempt to extend the new dogma to Inanna of Uruk was made, though this was evidently considered too much for contemporary audiences. Multiple sources display varying degrees of opposition to replacement of Inanna in the Eanna by a goddess who didn’t belong there, presumably either Zarpanitu or at the very least Bēlet-Bābili after “Zarpanituification” so severe she no longer bore a sufficient resemblance to her Urukuean colleague (The Pantheon…, p. 76-77). Inanna of Uruk was restored during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, who curiously affirmed that her temple was temporarily turned into the sanctuary of an “inappropriate goddess” (The Pantheon…, p. 131). However, the Marduk-centric ventures left a lasting negative impression in Uruk nonetheless, and in the long run lead to quite extreme reactions, culminating in the establishment of an active cult of Anu for the first time, but that’s another story (I might consider covering it in detail if there’s interest).

To go back to the hymn to Nanaya one last time, it’s interesting to note that a single copy seems to substitute ziqna zaqānu for zik-ra-[...], possibly a leftover of zikrāku, “manly”. Takayoshi M. Oshima and Alison Acker Gruseke presume this is only a scribal mistake, since this heavily damaged exemplar is rife with typos in general (She Walks…, p. 63), though I’m curious if perhaps a reference to the military character of Inanna herself or Annunitum was meant. This would line up with evidence from Babylon to a certain degree, since through the first millennium BCE Annunitum was worshiped there in her own temple (Goddesses in Context…, p. 105-106). However, in the light of what is known about this unique variant, it’s best to assume that it is indeed a typo and the hymn simply refers to luminosity.

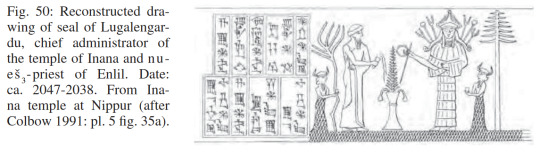

While no textual sources earlier (or later, for that matter) than the two hymns discussed above attribute a beard to Inanna (Zainab Bahrani, Women of Babylon. Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia, p. 182), the most commonly cited example of a seal with a supposedly bearded depiction is considerably earlier (Ur III, so roughly 2100 BCE, long before any references to “bearded Venus”). It comes from the Umma area judging from the name and title of its owner, a certain Lu-Igalima, a lumaḫ priest of Ninibgal (“lady of the [temple] Ibgal”, ie. Inanna’s temple in Umma). However, Julia M. Asher-Greve points out that the beard is likely to be a strand of hair, since contemporary parallels supporting this interpretation are available, for example a seal of a priest of Inanna from Nippur, Lugalengardu. Furthermore, she notes that the seal cutter was seemingly inexperienced, since the detail is all around dodgy, for example Inanna’s foot seems to be merged with the head of the lion she stands on (Goddesses in Context…, p. 208). Looking at the two images side by side, I think this is a compelling argument, since the beard doesn’t really look like, well, a typical Mesopotamian beard, while the hairdo on the Nippur seal is indeed similar:

Both images are screencaps from Goddesses in Context, p. 403; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

While I think the beard-critical arguments are sound, this is not the only possible kind of depiction of Inanna argued to reflect the fluidity of gender attributed to the planet Venus.

Paul-Alain Beaulieu notes that an inscription of Nebuchadnezzar with a dedication to Inanna of Uruk she might be called both the lamassu, ie. “protective goddess”, of Uruk and šēdu, ie. “protective genius”, of Eanna; the latter is an invariably masculine term. However, it is not entirely clear if the lamassu and šēdu invoked here are both really a partially masculine Ishtar, since there’s a degree of ambiguity involved in the concept of protective deity or deities of a temple - while there’s evidence for outright identification with the main deity of a given house of worship, they could also be separate, though closely related, and Beaulieu ultimately remains uncertain which option is more plausible here (The Pantheon…, p. 137-138). He also points out that there’s some late evidence for apotropaic figures with two faces, male and female, which were supposed to represent a šēdu+lamassu pair, but rules out the possibility that these have anything to do with Ishtar, since two faces are virtually never her attribute (The Pantheon…, p. 137). There is a single possible exception from this rule, but it’s an outlier so puzzling it’s hard to count it. A single Neo-Assyrian text from Nineveh (KAR 307) describes Ishtar of Nineveh (there is a reason why I abstain from using the name Inanna here, as you’ll see later) as four-eyed, which Beaulieu suggests might mean the deity had a male face and a female face. The same source also states that Ishtar of Nineveh is Tiamat and has “upper parts of Bel” and “lower parts of Ninlil”, though (The Pantheon…, p. 137), so it’s probably best not to think of it too much - Tiamat is demonstrably not a figure of much importance in general, let alone in the context of Inanna-centric considerations.

The same text has been interpreted differently by Wilfred G. Lambert. He concludes that it’s ultimately probably an esoteric Enuma Elish commentary and that it might have been cobbled together by a scribe from snippers of unrelated, contradictory sources (Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 245). If correct, this would disprove Beaulieu’s proposal, since the four eyes would simply reflect the description of Marduk (Bel) in EE (tablet I, line 55: “Four were his eyes, four his ears”). I lean towards Lambert’s interpretation myself; the reference to Tiamat is the strongest argument, outside EE and derived commentaries she was basically a non-entity. I’ll go back to the topic of Ishtar of Nineveh later, though - there is a slim possibility that two faces might really be meant, though this would take us further away from Inanna, all the way up to ancient Anatolia.

As a final curiosity it’s worth pointing out that while this is entirely unrelated to the discussed matter, KAR 307 is also the same text which (in)famously states Tiamat has the form of a dromedary. As odd as that sounds, it’s much easier to explain when you realize that the Akkadian term for this animal, when broken down to individual logograms, could be interpreted as “donkey of the sea” - and Tiamat’s name was derived from the ordinary Akkadian word “sea” (Babylonian Creation…, p. 246).

The Red Lady of Heaven, my king

While both the bearded and two faced Inannas are likely to be mirages, this doesn’t mean the dual gender of Venus was not reflected in the world of gods. The result was a bit more complex than the existence of a male Inanna, though.

In addition to being Inanna’s astral attribute, Venus simultaneously could be personified under the name Ninsianna. Ninsianna could be treated as a title of Inanna - this is attested for example in a hymn from the reign of Iddin-Dagan of Isin - but unless explicitly stated, should be treated as a separate deity. This is evident especially in sources from Larsa, where the two were worshiped entirely separately from each other (Goddesses in Context…, p. 92).

Ninsianna’s name can be literally translated as “red lady of heaven” (Goddesses in Context…, p. 86), though as I already explained earlier, nin is actually gender neutral - “red lord of heaven” is theoretically equally valid. And, as a matter of fact, it is necessary to employ the latter translation in some cases - an inscription of Rim-Sin I refers to Ninsianna with the firmly masculine title lugal, “king” (Wolfgang Heimpel, Ninsiana, p. 488).

It seems safe to say that in Ninsianna’s case we’re essentially dealing with a deity who truly was like Venus. Timothy D. Leonard stresses that while frequently employed in past scholarship, the labels “hermaphroditic” and “androgynous” do not describe the phenomenon accurately. What the sources actually present is a deity who switches between a male form and a female one (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 226). In other words, if we are to apply a contemporary label, it seems optimal to say Ninsianna was perceived as genderfluid.

Interestingly, though, it seems that Ninsianna’s gender varied by location as well (Goddesses in Context…, p. 92). The worship of feminine Ninsianna is attested for example in Nippur (Goddesses in Context…, p. 101) and Uruk (Goddesses in Context…, p. 126), masculine - in Sippar-Amnanum, Girsu and Ur (Ninsiana, p. 488-489). No study I went through speculated what the reasons behind this situation might have been. Was Ninsianna’s gender locally viewed as less flexible than the discussed theological texts indicate? Were specific sanctuaries dedicated only to a specific aspect of this deity - only the “morning” Ninsianna or “evening” Ninsianna? For the time being these questions must remain unanswered in most cases.

There’s a single case where the preference for feminine Ninsianna was probably influenced by an unparalleled haphazard theological innovation, though - in Isin in the early second millennium BCE the local dynasty lost control over Uruk, and as a result access to royal legitimacy granted symbolically by Inanna. To remedy that, the tutelary goddess of their capital was furnished with similar qualifications through a leap of logic relying on one hand on the close association between Inanna and Ninsianna, and on the other on the phonetic (but not etymological) similarity between the names of Ninisina and Ninsianna (Goddesses in Context…, p. 86). As far as I know, this did not influence the perception of Ninisina’s gender in any shape or form, though.