#modal improvisation

Text

MINOR TOPIC-EASIER WAY TO IMPROVISE WITH MODES

Minor topic-improvising on modes mad easier for guitar

CLICK SUBSCRIBE!

minor topic-an easier way to improvise with modes of music

IMPORTANT: Please watch video above for detailed info:

Hi Guys,

Today, a quick look at another way of exploiting modes/improvisation on the guitar fingerboard.

We will be creating music via concepts/musical tools based on this minor shape.

Why do this?

Because with this 5 fret shape arpeggio we can easily…

View On WordPress

#easy method#explained#guitar approach notes#guitar target tones#how to#lesson#Minor Topic#modal guitar improv#modal improvisation#modal pentatonics#modal triad pairs#modes#modes made simple#Pat Martino#pentatonic modes#quartal guitar modes#secrest#simple guitar modes#simplifing guitar modes#string skipping modes

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

1 SYNTHESIZER +1 LOOPER = INSTANT AMBIENT LUSH MUSIC: DITTO + and COBALT...

#youtube#synth#synthesizer#cobalt 5s#modal electronics#music#jam#improvisation#ambient#relaxation#looper#ditto plus#ditto looper

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

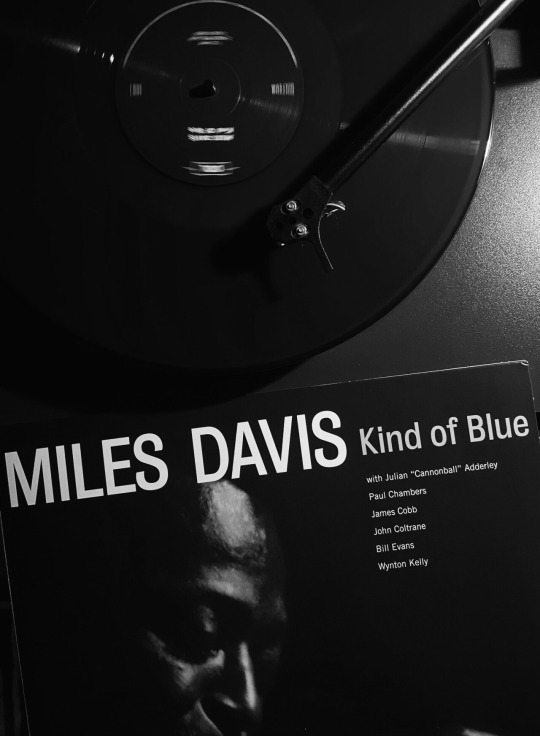

Kind of Blue is arguably Miles’ greatest hit, the one album with which he is most associated. It is still one of the most popular jazz albums of all time, outselling most contemporary recordings and prized as a harbinger of modal jazz and revered as a paradigm of improvisation over reduced harmony—creating a perfect balance of sound and space. Outside the jazz realm, it is consistently chosen by music historians and critics as one of the best albums of all time, alongside evergreen classics by The Beatles, Elvis Presley, and others.

Inspired by many ideas—mood-painting, modal structures—behind the soundtrack to Elevator to the Gallows, Kind of Blue can be seen as Miles’ signature work not only in its enduring popularity, but its attitude as well; in many ways the album’s cool and aloof effect, with its minimal, almost dismissive musical gestures, serves as a sonic reflection of Miles legendary aloofness. The title of its famous opening track—“So What”—is a perfect reflection of Miles’ insouciant, sunglasses-at-midnight way of being.

Numerous other elements specific to Kind of Blue push it to the top of the “Best Of” lists: the all-star sextet Miles had assembled to accompany him, including three players (John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Cannonball Adderley) who would themselves prove to be jazz legends, and a rhythm section (Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Cobb) that outswung any other in its day. There was the shared feeling of fresh discovery in the studio on those two days in 1959, as almost all the tracks were the first complete takes—no edits, no second tries. There was Bill Evans’ evocative essay on the album’s back cover highlighting that idea of “first-mind, best-mind”, comparing their music to the spontaneous, unerasable ink-on-rice-paper work of a Japanese calligrapher.

Miles Davis

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stupendously pyrotechnical

"It was Jimmy Page's stupendously pyrotechnical guitar that got the Zeppelin off the ground. And from his eerie plagal cadence [...] to his blinding flashes of free improvisation, Page seemed to have been listening to tapes of '40s-vintage radio shows. [...] Page launched a five-minute exploration of his near-lethal instrument as perilous and wondrous as any venture into space. Alternately bowing, slapping and picking his amplified strings with both hands, producing staggered combinations of overtone clusters, esoteric sound effects; beating the strings and fretting glissando melodies over his own percussive blasts, fretting high on the neck in widely fluctuating cycles of fifths, sevenths and modal licks and meticulously controlled five-string arpeggios - even at stages echoing the timbre of a human voice - Page literally created a short symphony for amplified strings and performed the entire work alone."

- From the Aug. 26, 1971 Houston concert review by J. Scarborough (Chronicle)

#jimmy page#pagey#led zeppelin#john bonham#bonzo#john paul jones#jonesy#robert plant#planty#60s#70s#70s rock#70s music#rock music#ourshadowstallerthanoursoul

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

You’ve probably gotten this question a ton but, do you have any tips or resources on writing a hypnosis induction for the first time? I’m writing a story involving hypnokink and I’ve only been a subject in real life.

Thank you ever so much for asking.

I'll break my advice down into segments for tailoring the best I can. The general advice I have is to listen to long form files by prominent hypnotists within the community and take notes on their styles and flows. I have often noted that one of the best way to learn hypnosis is through experience.

Of my two certification courses the second one, run by Wiseguy, included the invaluable piece of wisdom "The best hypnotic induction is the one that works."

Also check out a set of Zebu cards or download a PDF that contains their write-ups. Zebu Cards are prompts for Ericksonian phrases you can use and explanations of how and why they work. If you need a "how to cheat" sheet then Zebu Cards are an instant win unless you are working with someone literal minded who doesn't deal well with indirect induction methods.

Wiseguy actually did more work training me out of those habits than anything else. Years ago I was fairly fluent in flowery and empty sentiment.

Ericksonian/NLP techniques need not sound as forced as they are in the cards but it's a learning block.

But that's very vague and though I truly consider it the best advice it is less actionable than working out what you wish to write... with that said here is my breakdown:

Select your audience

When writing an induction script you need to know who you are writing for. Is the audience an individual, a group of people or yourself? If it's for an external audience then have you negotiated contents and worked out preferences or are you doing it cold?

How will the script be utilized? Is it to be studied and used as framework for an improvised scene in the moment, is it going to be read by the recipient, recorded? All these little thoughts will change how you handle things. Even a simple comment about the "sound of my voice" will have to switch up based on who is reading and under what context and for what outcome.

Modality

Hypnotic inductions tend to work on different modalities and individuals tend to have ones that they favor more than others. During a pre-talk in a negotiation or a cold session the hypnotist tends to test out preferred modality via susceptibility tests.

It's best when doing something where you do not know for sure what will work to mix in a number of different modalities and request feedback if that is possible for you. Some examples are visual fixations, audio fixations and kinesthetic fixations. I sometimes put emotional fixations in with kinesthetic but that is preference based.

What I mean by this is if you know how a person processes information then present them their induction in that method. For myself I am very feeling and sensing and so being asked to feel sensations of my body is better than utilizing visual imagination or audio cues.

"As you hear the sound of my voice and all distractions fade away you can listen to your breathing and notice it becoming softer and slower, the gentle beat of your heart may follow down into that gentle rhythm" is a slightly overt version of a line from an audio script.

"And you'll see that you're already starting to drift down. Can you picture it. You laying down as your slack arms sink down, are your eyelids fluttering, I wonder? It's okay if they are, because you can still watch as you sink deeper even with your eyes resting closed" for visual.

"With every moment that passes you drift more and it feels so good to just let go and relax deeper now. Feeling your lungs empty of air and noticing perhaps how relaxing that is. Do you feel relaxation as a tingling in your head or a lightness in your skin? Either way it feels so good to just drop deeper and so you can let go even more for me now." for kinesthetic.

Direct/Indirect

As you may see I usually lean more indirect than direct in my inductions. I have been taught by some incredible partners how to code switch into direct for dramatic effect. They reward me so very well with whimpers and delight, I feel I must perfect the technique for them.

A mix is always good but an induction, particularly when rapport and intent are not carrying you, should always lean in on your strong suit. Only you will know your style. Play around in the space, see what you can find.

The Induction Starts With Negotiation

This one is a bit obvious but every hypnosis session begins before the hypnotee agrees to begin. If you post a hypnotic audio on YouTube then the summary and preamble are not just there to list the contents they are there to set expectation.

Do not misunderstand and believe that mind control happens before consent. What I mean is that expectation is an active part of the induction.

This can be in carrying confidence of tone "This file will use my voice to draw you into an impossibly deep trance" is more evocative than "I want to try and do some test inductions and want anyone who listens to experience a deep trance" while having much of the same information.

Plus the first example has an indirect suggestion that ties the sound of my voice to the action of you being drawn into trance. Just like the sentence I'm typing right now is a promise that you'd fall under my spell if I were to will it so.

Tone and expectation are important tools and being able to embody the role and work towards your goal at all times is important. Don't be a jerk about it, just be confident. Knowing you will succeed and convincing someone else you can and will do it makes it so. Hypnosis tends to be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Wrap safety in

In the same vein, I would always recommend to do the old "if anything comes up that requires you to exit this scene you can and will handle it knowing the script/file/opportunity will be waiting for you" and such. Hypnosis is a bond of trust between consenting individuals and a hypnotist must do their best to protect their hypnotee while they are entrusted to them as a hypnotee must be responsible with the practice of hypnosis so a hypnotist can trust the process with them.

If it's 1-on-1 then ask for limits, try to find out what will make it a pleasant experience, make your own requests if there are areas you want to explore.

After all the last and most important tip is always going to be...

Have fun!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra - L’Inter Communal and Le Musichien, Souffle Continu Records reissues of albums from 1978 and 1983

The Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra was created in 1971 by an “old hand” of French free jazz, François Tusques. Free Jazz, was also the name of the recording made by the pianist and other like-minded Frenchmen (Michel Portal, François Jeanneau, Bernard Vitet, Beb Guérin and Charles Saudrais) in 1965. But, six years later Tusques had had his fill of free jazz.

After having wondered, together with Barney Wilen (Le Nouveau Jazz) or even solo (Piano Dazibao and Dazibao N°2), if free jazz wasn’t a bit of a dead end, Tusques formed the Inter Communal, an association under the banner of which the different communities of the country would come together and compose, quite simply. If at first the structure was made up of professional musicians from the jazz scene it would rapidly seek out talent in the lively world of the MPF (Musique Populaire Française).{French Popular Music, ndlt}

Compiled of extracts from concerts given between 1976 and 1978, L’Inter Communal is not the first album from the Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra. But it is the one which shows with the most exuberance the “social function” which inhabited free jazz and popular music at the time. All the more so as, to head up the project, the group (made up of wind instruments: Michel Marre, Jo Maka, Adolf Winkler and Jean Méreu) called upon Spanish singer Carlos Andreu. Andreu, claimed Tusques, was a griot “who created of new genre of popular song improvised with our music, based on events going on at the time”.

As with L’Inter Communal a few years earlier, Le Musichien follows on from the group of varying musicians that Tusques had conceived as a “people’s jazz workshop”. In 1981, at the then famous Paris address, 28 rue Dunois, the pianist sang with his partner Carlos Andreu an “afro-Catalan tale”. Over a slow bass line (exceptional work from Jean-Jacques Avenel) backed by percussion from Kilikus, saxophones (Sylvain Kassap and Yebga Likoba) and trombone (Ramadolf) which presented a myriad of constellations. The sky has no limits, let’s make the most of it.

The following year, at the ‘Tombées de la Nuit’ festival in Rennes, bassist Tanguy Le Doré would weave with Tusques the fabric on which would evolve an explosive “brotherhood of breath”: Bernard Vitet on trumpet, Danièle Dumas and Sylvain Kassap on saxophones, Jean-Louis Le Vallegant and Philippe Le Strat on… bombards. With hints of modal jazz inspired by Coltrane or Pharoah Sanders, the Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra is an ecumenical project which speaks to the whole world.

#Bandcamp#Intercommunal Free Dance Music Orchestra#france#70s#80s#jazz#spiritual jazz#reissue#Souffle Continu Records

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

An attempt at conveying a historically accurate rendition of Ancient Greek music based on our knowledge of it. Music by Dimitris Athanasopoulos of the One Man's Noise channel, and arrangement by Farya Faraji.

The music is based on a recording Dimitris made, improvising on reed instruments called aulos in Antiquity. Farya Faraji added the sound of a varvitos lyre, as well as drums and cymbals.

The main melody employs the chromatic genus of Ancient Greek modality. Farya Faraji added to it a drone on the lyre and aulos that repeats the tonic, something very common within horizontal, monophonic/heterophonic traditions like that of Ancient Greece.

#once again fantastic work from perhaps the only xenos who's gotten down so good our folk music so far!#And I am so happy Farya works with Greek musicians for a great result!#hellas#hellenismos#greek music#greek tradition#korinthos#corinth#Youtube

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Without proper weapons, the zedconians had to get creative with their defense. Here, a DiTCH is used to fling inter-modal containers of hazardous industrial chemicals.

Improvised combat using industrial equipment is a concept I really like.

#sketches#traditional media#zedcon#diesel#two stroke diesel#DiTCH#mech#mechanized dinosaur#mobile crane#improvised combat#my art#industrial combat

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, you seem to know music stuff! I had a question - what the actual fuck is a Dorian scale 😭 is it just a c Major scale but the tonic is now D and so everything's messed up???

Also, how would you recognise it, and why would it be used?

Thank you!!

hi! i got this ask a while ago but i was taking a little tumblr break.

the dorian scale, or more accurately, the dorian mode, is built off of the second scale degree of the major scale yes.

modes can be though of different iterations of a scale, the concept is just that you can take any scale degree of any scale, act as if that scale degree is the tonic and boom! brand new unique sound.

emotionally, dorian can be though of a slightly brighter minor. it still has the b3 and the b7, but it still has a major 6th!

and theres a bunch of other modes too, like for example built off the 4th degree of the major scale there's the lydian mode, it has a #4 and sounds brighter than major tonalities. (if used traditionally)

learning to recognize different modes is a bit trickier, like every part of musical identification; you just gotta get familiar and build up your ear. if you are looking at sheet music, it can be pretty easy to identify which section is the start of a phrase and whats the tonic and whats resolving to what. if the tonic isnt scale degree 1 of the current key signature, it's likely you've got yourself a mode!

and why it, or other modes would be used is relatively simple! they are their own sounds that grant different unique experiences. while im definitely sterotyping, lydian can be seen as bright and bubbly, phyrigian as dark and brooding, mixolydian as motionless and floaty. its all just different ways to invoke fun sounds. theres also the concept of modal jazz, which is, *extremely roughly,* the idea that every chord has it's scale that it can be thought of being representative of, and being able to use that to quickly improvise solos and write melodies. if you ever see a #4 chord, that can be thought of invoking the lydian mode, just harmonically.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening Post: John Coltrane/Eric Dolphy’s Evenings at the Village Gate

In 1961, John Coltrane was reaching a wider audience via his edited single version of the Sound of Music classic "My Favorite Things.” He was also, although it seems trite to say given the trajectory of his career, in a state of transition. Moving away from his "sheets of sound" period to exploring modality, non-western scales and polyrhythms which allowed him to improvise more deeply within the constraints of more familiar Jazz tropes.

His personal and musical relationship with Eric Dolphy was an important catalyst for the development of his sound. Dolphy was an important presence on Coltrane's other key album from 1961, Africa/Brass and here officially joins the quartet on alto, bass clarinet and flute. Evenings at the Village Gate was recorded towards the end of a month-long residency with a core band of Coltrane, Dolphy, Jones, McCoy Tyner on piano and Reggie Workman on bass. The other musician featured here, on "Africa,” is bassist Art Davis.

The recording captures the band moving towards the more incandescent sound that made Live at the Village Vanguard, recorded just a few weeks later in November 1961, such a viscerally thrilling album. The hit "My Favorite Things" and traditional English folk tune "Greensleeves" are extended into long trance-like vamps. Benny Carter's 1936 classic "When Lights Are Low" showcases Dolphy's bass clarinet and in the originals "Impressions" and particularly "Africa" the quintet hit almost ecstatic grooves. Dolphy's solos push Coltrane further into the spiritual free jazz that so divided later audiences. Dolphy's flute on "My Favorite Things" and especially his clarinet on "When Lights Are Low" are extraordinary, particularly the clarity of his upper register.

The highlight for me is the 22 minute version of "Africa" that closes the set. The two basses, bowed and plucked, Tyner's chordal work and solo, the slow build from the bass solo where the music seems to meander before Jones' explosive solo heralds the return of Dolphy and Coltrane improvising together on the theme, spiralling up the register, contrasting Coltrane's long slurries with Dolphy's staccato bursts which lead to the thunderous conclusion.

As an archivist, sudden discoveries in forgotten basement boxes never surprises and the excitement never gets old. The tapes of Evenings at the Village Gate were recently unearthed in the NY Public Library sound archive after having been lost, found and lost again. Recorded by the Village Gate's sound engineer Rich Alderson these tapes were not meant for commercial use but rather to test the room's sound and a new ribbon microphone. As Alderson says in his notes, this was the only time he made a live recording with a single mic and, yes, there have been grumblings from fans and critics about the sound quality and mix particularly the dominance of Elvin Jones' drums. For me, one the best things about this is that you hear how integral Jones is not just as a fulcrum for the other soloists but as an inventive polyrhythmic presence, playing within and around his bandmates. I know that many of the Dusted crew are Coltrane fans and would love to hear your takes on the music and whether the single mic recording affects your enjoyment in any way.

Andrew Forell

youtube

Justin Cober-Lake: There's so much to get into here, but I'll respond to your most direct question. The single-mic recording doesn't affect my enjoyment at all. I understand (sort of) the complaints, but I think they overstate the problem. More to the point, when I hear an archival release, I really want to get something new out of it. That doesn't mean I want a bad recording, but there's not too much point in digging up yet-another-nearly-the-same show (and I have nearly unlimited patience for Coltrane releases) or outtakes that give the cuts the same basic idea but just don't do it as well. I was really looking forward to hearing Coltrane and Dolphy interact, and nothing here disappoints. Having Jones so dominant just means I get to hear and think more about the role he plays in this combo. It would sound better to have the other instruments a little more to the fore, but it's not a problem (and actually Tyner's the one I wish I could hear a little better).

I think your topic suggests ideas about what these sorts of recordings — when made publicly available — are for. Is it academic material (the way we might look at a writer's journals or correspondence)? Is it to get truly new and good music out there? Is it a commercial ploy? Is it a time capsule to get us in the moment? The best curating does at least three of those with the commercial aspect a hoped-for benefit. This one probably hits all four, but I suspect the recording pushes it a little more toward that first category.

Bill Meyer: I’m playing this for the first time as I type, and I’m only to track three, so my (ahem) impressions could not be fresher.

First, I’ll say that, like Justin, I have a lot of time for Coltrane, and especially the quartet/quintet music from the Impulse years. The band’s on point, it sounds like Dolphy is sparking Coltrane, and Jones is firing up the whole band. Tyner’s low in the mix and Workman’s more felt than heard; the recording probably reflects what it was like to actually hear this band most nights, i.e. Jones and the horn(s) were overwhelming.

How essential is it? If you’re a deep student of Coltrane, there are no inessential records, and the chance to hear him with Dolphy, fairly early on, should not be passed up. But if you’re big fan, not a scholar, then you need to get The Complete 1961 Village Vanguard Recordings box and the 7-CD set, Live Trane: The European Tours, before you drop a penny on this album. And if you’re just curious, start with Impressions. This group is hardly under-documented. The sound quality, while tolerable, is compromised enough to make Evenings At The Village Gate less essential than everything I just mentioned.

I’m only just now starting to play “Africa,” so I’ll check in again after I play that.

“Africa” might be the best reason for a merely curious listener to get this album. It’s very exploratory, the bass conversation is almost casual (not a phrase I use much when discussing Coltrane), and they manage to tap into the piece’s inherent grandeur by the end.

“Africa” is a great example of this band working out what they’re doing while they’re doing it.

Andrew Forell: On Justin’s points about the function of archival releases, I’ve been going back and forth on the academic versus time capsule/good music uncovered question. There is a degree of cynicism and skepticism in these days of multidisc, anniversary box sets in arrays of tastefully colored vinyl which seemed designed for the super(liquid)fan and cater to a mix of nostalgia and fetish. Having said that specialist archival labels have done us a great service unearthing so much "lost" and under-represented music. On one hand I agree with your summation and to Bill’s point, yes this quintet has been pretty thoroughly documented and yes the Vanguard tapes would be the place to start. But purely as a fan I am more interested in live recordings than discs of out- and alternative takes. I’m thinking for example of the 1957 Monk/Coltrane at Carnegie Hall and Dolphy’s 1963 Illinois concert especially his solo rendition of “God Bless the Child," recordings that sat in archives for 48 and 36 years respectively.

youtube

By contrast, the other recent Coltrane excavation, Both Directions at Once is wonderful but I’m not listening to it as an academic exercise, taking notes and mulling over the different takes, interesting as they are. I approach Evenings as another opportunity to hear two great musicians, in a live setting, early on in their short partnership. As Justin says, this aspect doesn’t disappoint. I agree with Bill that the mix is close to what you would you hear in the room, the drums and horns to the fore. All this is a long way to a short answer. A moment in time, a band we’ll never experience in person and when all is said and done, 80 minutes of music I’d otherwise not hear.

Jonathan Shaw: As a relative newb to this music, I can't contribute cogently to discussions of this set's relative value. Most of the Coltrane I've listened to closely is from very late in his life, when he was playing wild and free--big fan of the set from Temple University in 1966 and the Live at the Village Vanguard Again! record from the same year. None of that is music I understand, but I feel it and respond to it strongly. The only Dolphy I've listened to closely is Out There. So I'll be the naif here.

I need to listen to these songs another few times before I can say anything about them as songs, but I really love the right-there-ness of the sound. I like being pushed around by the drums and squeezed between the horns (the first few minutes of "Greensleeves" are delightful in that respect). Maybe I'm lucky to come to the music with so little context. It's a thrill to hear the playing of these folks, about whom there is so much talk of collective genius. Perhaps because my ears are so raw to these sounds, I feel like that talk is being fleshed out for me.

Jim Marks: I think that this release has both academic and aesthetic (if that’s the right word) significance for Dolphy’s presence alone. I am more familiar with the original releases than the various re-releases from the period, but it’s my impression that there just isn’t that much Dolphy and Trane out there; for instance, I think Dolphy appears on just one cut of the Village Vanguard recordings (again, at least the original release). In particular, I’ve heard and loved various versions of “Favorite Things,” but this one seems unique for the six-plus-minute flute solo that opens the track. The solo is both brilliant in itself and creates a thrilling contrast with Coltrane when he comes in. This track alone is worth the price of admission for me.

Marc Medwin: I agree concerning Dolphy's importance to these performances, and while there is indeed plenty of Coltrane and Dolphy floating around (he took part in the Africa/Brass sessions that gave us both Africa and a big band version of "Greensleeves") his playing is really edgy here. Bill is right to point toward the sparks Dolphy's playing showers on the music. Yes, the flute on "My Favorite Things" is really stunning. He's all over the instrument, even more so than in those solos I've heard from the group's time in Europe.

Jon, I'd suggest that there's a strong link between the albums you mention and the Village Gate recordings we're discussing, a kind of continuum into which you're tapping when you describe the excitement generated by the playing. The musicians were as excited at the time as we are on hearing it all now! It was all new territory, the descriptors were in the process of forming, and while Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra and a small group of kindred spirits were already exploring the spaceways, they were marginalized. That may be a component of the case today, but it's tempered by a veneration unimaginable at the time. That's part of the reason Dolphy lived in apartments where the snow came through the walls. Coltrane had plenty to lose by alienating the critics, but ultimately, it did not stop his progress. These recordings mark an early stage of that halting but inexorable voyage. With the possible exception of OM, Coltrane's final work never abandoned the tonal and modal extremes at which he was grabbing in the spring and summer of 1961.

Jennifer Kelly: Like Jon, I'm not well enough versed in this stuff to put it context or even really offer an opinion. I'm enjoying it a lot, and I, also, like the roughness and liveness of the mix with the foregrounded drums. But I think mostly what I am drawn to is the idea that this show happened in 1961, the year I was born, and that these sounds were lost for decades, and now you can hear them again, not just the music but the room tone, the people applauding, the shuffling of feet etc. from people who are almost all probably dead now. It seems incredibly moving, and I am also taken by the part that the library took in this, in conserving this stuff and forgetting it had it and then rediscovering it. In this age of online everything-available-all-the-time, that seems remarkable to me, and proves that libraries are so crucial to civilization now and always, even as they're under threat.

Marc Medwin: A real time machine, isn't it? We are fortunate that we have these documents at all, and yes, the story of the tapes resurfacing is a compelling one! To your observations, audience reaction seems pretty enthusiastic to music that would eventually be dubbed anti-jazz by prominent members of the critical establishment!

Bill Meyer: I can imagine this music being more sympathetically received by audiences experiencing its intensity, whereas critics might have fretted because it represented a paradigm shift away from bebop models, so they had to decide if it was jazz or not.

It is amusing, given the knowledge we have of what Coltrane would be playing in five years, that this music is where a lot of critics drew a line in the sane and said, "this is antijazz."

Jon Shaw: Yes, Bill, that seems bonkers to me. I am particularly moved by the minutes in that 1966 set at Temple when Coltrane abandons his horn altogether and starts beating his chest and humming and grunting. Wonder what the chin-stroking jazz authorities made of that.

Given my points of reference, this set sounds so much more musically conventional. But the emotional force of the music is still immediate, viscerally present. Beautifully so.

youtube

Andrew Forell: In retrospect, all those arguments seem kind of crazy. Yesterday’s heresies become tomorrow’s orthodoxies but what we’re left with is, as Jonathan says, the visceral beauty of Coltrane’s striving for transcendence and his interplay with Dolphy’s extraordinary talent which we hear here working as a catalyst for Coltrane. As Marc and Jen note the audience is there with them..

Come Shepp, Sanders & Rashid Ali, the inquisitors’ fulminations only increased and you think what weren’t you hearing?

Marc Medwin: I was just listening to a Jaimie Branch interview where she's talking about her visual art, about throwing down a lot of material and finding the forms within it. I think that might be another throughline in Coltrane's and certainly Dolphy's work, a gradual discarding of traditional forms and poossibly structures based on what I hate to call intuition, because it diminishes the process.

Then, I was thinking again about our discussion of the critics. I see their role, or their assessment of that role, as a kind of investment without reward, and yeah, it does seem bonkers now! Bill Dixon once talked about how the writers might spend considerable time and expend commensurate energy learning to pick out "I Got Rhythm" on the piano, and they're suddenly confronted with... well, the sounds we're discussing! What would you do, or have done, in that situation? It's really easy for me, like shooting fish in the proverbial barrel, to

disparage critical efforts of the time, especially in light of the ideas and philosophies Branch and so many others are at liberty and encouraged to play and express now, but I wonder how I would have

reacted, what my biases and predilections would have involved at that pivotal moment.

Ian Mathers: The points about historical reception are really interesting, I think. There's a famous (in Canada!) bunch of Canadian painters called the Group of Seven, hugely influential on Canadian art in the 20th century and still well known today. In all the major museums, reproductions everywhere, etc. They were largely landscape painters, and while I think most of the work is beautiful, it's so culturally prominent that it runs the risk of seeming boring or staid. I literally grew up with it being around! So it was a delightful shock to read a group biography of them (Ross King's Defiant Spirits: The Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven, if anyone is hankering for some CanCon) and see from contemporary reviews that people were so shocked and appalled by the vividness of their colour palettes and other aesthetic choices that they were practically called anti-art at the time. It's not surprising to me that this music would both attract similar furore at the time and, from the vantage point of a new listener in 2022 who loves A Love Supreme and some of the other obvious works but hasn't delved particularly far into Dolphy, Coltrane live, or this era in jazz in general (that would be me), be heard and felt as great, exciting, but not exactly formally radical stuff.

I don't think I would have noticed much about the recording quality were people not talking about it. "My Favorite Things" seems to have the overall volume down a bit, but still seemed pretty clear to me (agree with the assessments above; Coltrane, Dolphy, and Jones very forward, others further back although even when less prominent I find myself 'following' Tyner's work through these tracks more often than not), and starting with "When Lights Are Low" that seems to be corrected. It actually sounds pretty great to me! Although I absolutely defer to Bill's recommendations for better starting places for serious investigations, I can also say as a casual but interested fan who tends to quail in the face of box sets and other similarly lengthy efforts this feels from my relatively ignorant vantage like a perfectly nice place to start. I like Justin's rubric for why these releases might come about (or be valuable), but if I hadn't heard any Coltrane and you just gave me this one, my unnuanced perspective would just be something like "wow, this is great!" But maybe I'm underthinking it. And having that reaction doesn't mean that others aren't right to recommend better/more edifying entry points, or that having that reaction shouldn't lead one to educate oneself.

Jonathan Shaw: Maybe it's a lucky thing for me to be so poorly versed in Coltrane's music, not just in the sense of having listened to precious little of it. I am even less familiar with the catalog of music criticism, which in jazz seems to me voluminous, archival in scale. But even with music I'm extensively engaged with — historically, critically — I try to understand it and also to feel it. I can't imagine not feeling what's exciting in this music, energizing and challenging in equal measure.

Like Marc, I don't want to recursively impugn the critical writing of folks working in very different contexts. But I don't like it when the thinking gets in the way of the music's emotional and aesthetic force, which to me feels unmistakably powerful here.

Ian Mathers: Yeah, maybe that's a good distinction to draw; I can imagine in a different time and place feeling like the music here is more radical or challenging than it sounds to us now. But I can't quite imagine not getting a visceral thrill out of it.

Marc Medwin: And doesn't this contradiction get at the essence of what we're trying to do? Those of us who've chosen to write about music are absolutely stuck grasping at the ephemeral in whatever way we're able! How do we balance the ordering of considerations and explanations in unfolding sentences with the spontaneity of action and reaction that made us pick up a pen in the first place?! We add and subtract layers of whatever that alchemical intersection of meaning and energy involves that hits so hard and compels us to write! In fact, the more time I'm spending with these snapshots of summer 1961, the more I decamp from my own philosophizing about critical relativity to sit beside Ian. The stuff is powerful and original, and the fact that so much of what we're hearing now is a direct result of those modal explorations and harmonically inventive interventions says that the dissenting voices were fundamentally, if understandably, wrong! It could be that the musician can be inclusive in a way the writer simply can't.

I'm listening to "Africa" again, which is for me the disc's biggest single revelation in that it's the only concert version we have, so far as I know. How exciting is that Jones solo, and how much does it say about his art and the group's collective art?!! He starts out in this kind

of "Latin" groove with layers of swing and syncopation over it, he

goes into a melodic/motivic thing like you'd eventually hear Ginger

Baker doing on Toad, and then eases back into the groove, all (if no

editing has occured) in about two minutes. He's got the music's

history summed up in the time it would take somebody to get through a proper hello!! Took me longer to scribble about it than for him to play it!!

Justin Cober-Lake: I'm not sure if Marc is making me want to put down or pick up a pen, but he's definitely making me want to listen to "Africa" again. (Not that I needed much encouragement.)

Andrew Forell: Africa/Brass was the first jazz album I bought. Coming from post-punk, I found it immediately the most exciting and challenging music I’d heard and it set me off on my exploration of Coltrane, Dolphy, Coleman and their contemporaries. This version of “Africa” is a highlight for me also for all the reasons Marc, Ian and Jon have talked about.

Bill Meyer: Yeah, "Africa" is quite the jam!

A thought about critical perspective — our discussion has gotten me thinking, not for the first time, about the impacts of measures upon experience, and the limits of critical thinking when I’m also an avid listener. If I’m listening for “the best” Coltrane/Dolphy, in terms of sound quality or most focused performances, this album isn’t it. But if I’m looking for excitement, this album has loads of it, and that might be enhanced by the drums-forward mix.

#listening post#dusted magazine#john coltrane#eric dolphy evenings at the village gate#jazz#reissuemmc#mccoy tyner#reggie workman#derek taylor#art davis#new york public library#andrew forell#justin cober-lake#bill meyer#africa#jonathan shaw#jim marks#mark medwin#jennifer kelly#ian mathers#Youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

But Who's Gonna Play the Melody?

Review by Matt Collar

Source: allmusic.com

Virtuoso bassists Christian McBride and Edgar Meyer offer a series of playful and artfully delivered duets on 2024's But Who's Gonna Play the Melody? While both McBride and Meyer are acclaimed in their own right and largely considered two of the best, if not the best bassists of their generation, they come to improvisational music from slightly different perspectives. A jazz star from a young age, McBride is steeped in the acoustic post-bop, R&B, and funk traditions with a strong classical technique underpinning his work. Conversely, Meyer, who teaches at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, is largely known for playing classical and progressive bluegrass music with a strong harmonic and improvisational jazz sensibility informing his work. They do, however, share a common connection: both were mentored by legendary jazz bassist Ray Brown. It was Brown who first introduced the two prior to his passing in 2002, just a few years before they first shared a concert stage at a 2007 performance in Colorado as part of the non-profit Jazz Aspen Snowmass. Recorded at Ingram Hall at Vanderbilt University's Blair School of Music, But Who's Gonna Play the Melody? finds them building upon that initial performance, tackling a mix of originals and covers. There's a warm camaraderie, balanced with just a hint of wry competition at play in these duets. There's also a deep appreciation of the blues throughout the album, as on the opening Meyer original "Green Slime," where McBride lays down a chunky, funk-like groove over which Meyer dances with zippy bowed asides before they switch roles. From there, they dive into the twangy "Barnyard Disturbance," a bluegrass-inflected number in which they trade soulful, vocal-sounding lines. Elsewhere, they offer engaging readings of standards, including the Miles Davis-associated modal jazz classic "Solar" and the ballad "Days of Wine and Roses." Interestingly, they also take turns playing piano on several tunes, as on "Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered" where Meyer offers a spare accompaniment to McBride's lyrical melody. Similarly, McBride takes to the keys for his chamber ballad "Lullaby for a Ladybug," spotlighting Meyer's languorous bowed technique. Certainly, the choice to accompany each other on piano works to highlight their distinctive bass styles. Thankfully, although they both play with big, woody tones, it's never too hard to tell them apart. Despite the wry humor implied by the album title, McBride and Meyer infuse every note of But Who's Gonna Play the Melody? with their own distinctive style, as if they were singing through their strings.

youtube

Good listening!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Coltrane and McCoy Tyner Style Quartal Guitar Line | Jazz Improvisation Lesson

View On WordPress

#explained#how to#jazz 4ths harmony#jazz guitar#jazz head#jazz improvisation#jazz music#John Coltrane#lesson#mccoy tyner#modal jazz#modern jazz#music#pentatonic jazz#pentatonic scales#quartal harmony#quartal jazz#trane jazz guitar#trane jazz lines#tune head#unison jazz riff

1 note

·

View note

Text

Billy Cobham – The Art Of Four

“With 2004’s Art of Five, the fusion drums pioneer Billy Cobham indicated that his mid-life return to his bebop roots was a hot ticket. And this album proves to be another, with a fizzing Cobham driving a pedigree postbop band featuring alto saxist Donald Harrison, short-lived pianist James Williams (on one of his last recordings) and the bass legend Ron Carter. Most of the material here is original, and the improvisation is often scorching – Williams’ jubilant sweep across bop, modalism and Cecil Taylorish abstraction in particular. Good for the Soul and Cissy Strut have a heated Art Blakey atmosphere. Harrison and Williams play solos of such fresh phrasing that they almost seem to reinvent the postbop language, and a fast The Song Is You has Harrison in biting Jackie McLean mode over fiery drumming. Carter’s Last Resort is like a sardonic Stan Tracey piece, and Williams’ Four Play is a rugged, Breckerish tour de force of fast blues. It’s four stars for the blowing quality alone.” – John Fordham/The Guardian.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

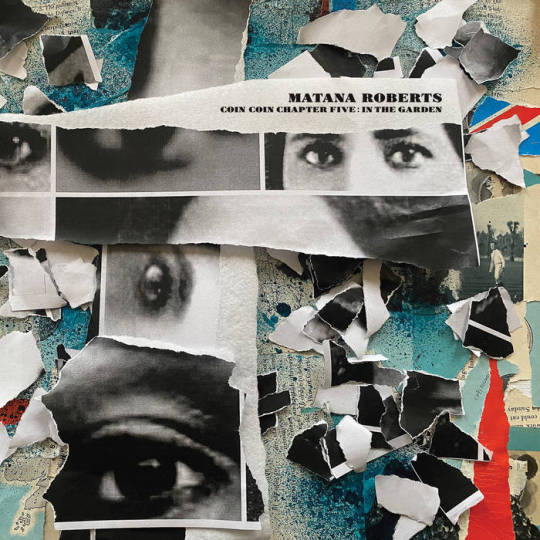

Coin Coin Chapter Five: In the garden… is the latest instalment in composer, improviser, saxophonist, bandleader and visual artist Matana Roberts’ visionary project exploring African-American history through ancestry, archive and place. Weaving together elements of jazz, avant-garde composition, folk and spoken word, Roberts tells the story of a woman in their ancestral line, who died following complications from an illegal abortion. At a time when reproductive rights are under attack, her story takes on new resonance. “I wanted to talk about this issue, but in a way where she gets some sense of liberation,” Roberts explains. By unpacking family stories and conducting extensive research in US public archives, Roberts has created a rounded portrait of a woman who is, as their lyrics put it, “electric, alive, spirited, fire and free.”

Each part of Coin Coin explores radically different musical settings, from the free jazz and post-rock eruptions of Chapter One to the solo noise collage of Chapter Three. Featuring a new ensemble steeped in jazz, improvisation, new music and avant-rock, helping to expand the project’s existing sonic palette, Chapter Five is no exception. Roberts is joined by fellow alto saxophonist Darius Jones, violinist Mazz Swift (Silkroad Ensemble, D’Angelo), bass clarinettist Stuart Bogie (TV On The Radio, Antibalas), alto clarinettist Matt Lavelle (Eye Contact, Sumari), pianist Cory Smythe (Ingrid Laubrock, Anthony Braxton), vocalist/actor Gitanjali Jain and percussionists Ryan Sawyer (Thurston Moore, Nate Wooley) and Mike Pride (Pulverize The Sound, MDC). The late, great trumpeter jaimie branch, who was due to play on the album, receives a credit for “courage”. The album is produced by TV On The Radio’s Kyp Malone, who also contributes synths.

As a composer, Roberts draws upon strategies associated with the post-war avant-garde, including John Cage and Fluxus member Benjamin Patterson’s conceptual approaches to scoring and performance. The immersive work of Maryanne Amacher, in which “sound and the body almost collaborate” is another key influence. “That is the foundation for me of the Coin Coin work,” they explain. “It’s not just the alto saxophone as an instrument placed in the jazz canon, it's the alto saxophone as an instrument that can be utilised to affect the body.”

Listeners will be struck by Roberts’ ability to mould diverse sounds into a cohesive whole. The spoken word passages are accompanied by driving modal jazz on “how prophetic”, minimalist synth loops on “enthralled not by her curious blend” and cantering folk forms on “(a)way is not an option”. These are interspersed with instrumental pieces that range from avant-garde abstraction and squalling free jazz, to solo saxophone reflections and Mississippi fife and drums blues. There’s a further evocation of American roots music in the powerful group vocal arrangement of “but I never heard a sound so long”, adapted by Roberts from the plantation lullaby “All The Pretty Horses.”

While this new chapter of Coin Coin focusses on a female-identified protagonist, others haven’t (Chapter Three being from the perspective of a male ancestor) and Roberts intends for future chapters to continue to cover the breadth of the gender spectrum, as well as their Native American heritage. “I'm proud that people say that the Coin Coin work speaks of a woman's story. But I want to make sure that it retains its inclusivity, because what we look like is not always what you see.” This reflects Roberts’ own experiences as a queer person of colour. For the remaining chapters of Coin Coin, Roberts will continue exploring identity and ancestry. “Expect it to keep heading towards a liberation of the human spirit.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sound Healing 🎶✨

Hello darlings 🥰

Today, let's immerse ourselves in the captivating realm of sound healing and discover the profound effects it can have on our well-being and spiritual growth. Sound has been used as a powerful tool for healing and transformation across cultures and throughout history. From soothing melodies to rhythmic vibrations, sound has the ability to harmonize our body, mind, and spirit. So, let's embark on a sonic journey together and explore the wonders of sound healing!

🎶 The Healing Power of Frequencies

Sound consists of different frequencies and vibrations that can impact us on a cellular level. Each part of our body, including organs, tissues, and cells, has its own vibrational frequency. Through the use of sound, we can restore balance and harmony by entraining our body to the frequencies that promote healing and well-being.

🎧 Sound Bath and Meditation

Immerse yourself in the therapeutic embrace of a sound bath or sound meditation. Relax in a comfortable position, close your eyes, and allow the soothing sounds of instruments like singing bowls, gongs, or chimes to wash over you. Let the vibrations resonate within you, releasing tension, calming the mind, and promoting a deep sense of relaxation and inner peace.

🎵 Chanting and Mantras

Tap into the power of your own voice through chanting and mantra repetition. Explore sacred chants from various spiritual traditions or create your own affirmations. The rhythmic repetition of sounds and words can help shift your energetic vibration, promote focus, and connect you to a higher state of consciousness.

🌬️ Breathwork and Vocal Toning

Explore the profound connection between sound and breath. Engage in intentional breathwork practices like pranayama, and combine it with vocal toning. As you inhale deeply, allow the sound to emerge on the exhale, using your voice to create sustained tones or harmonious melodies. This practice can help release stagnant energy, activate the chakras, and promote a sense of vitality and inner balance.

🔊 Tuning Forks and Singing Bowls

Experiment with the therapeutic vibrations of tuning forks and singing bowls. The precise frequencies produced by tuning forks can be applied to specific parts of the body, helping to restore balance and promote healing. Singing bowls, when played, emit a rich tapestry of harmonics that can induce deep relaxation and energetic alignment.

🎶 Sound and Movement

Combine sound with movement to amplify its healing effects. Engage in practices like sound yoga, where specific sounds or mantras are paired with yoga postures and breathwork. Dance and free movement can also be accompanied by intentional sound to facilitate emotional release, self-expression, and energetic flow.

🌌 Sound and Energy Healing

Explore the connection between sound and energy healing modalities like Reiki or acupuncture. Sound can enhance these practices by facilitating the flow of energy, clearing energetic blockages, and promoting balance and harmony within the subtle energy systems of the body.

🎵 Creating Soundscapes

Tap into your creativity by creating your own soundscapes. Use musical instruments, voice, or digital tools to compose or improvise sounds that resonate with your intentions and desired energetic atmosphere. Allow your intuition to guide you as you explore the vast palette of sounds available to you.

🔮 Sound as a Catalyst for Transformation

Embrace the transformative power of sound as a catalyst for personal growth and spiritual awakening. As you engage in sound healing practices, set clear intentions for your journey. Allow the vibrations to penetrate deep within, facilitating release, healing, and the expansion of consciousness.

Sound healing is a profound and accessible modality that can be integrated into your daily life, allowing you to cultivate a deeper connection with yourself, promote overall well-being, and harmonize your body, mind, and spirit.

Whether through a few minutes of intentional listening, chanting affirmations during your morning routine, or attending sound healing workshops and retreats, the transformative power of sound is always within reach, offering you a pathway to inner balance, self-discovery, and a greater sense of harmony with the world around you.

Embrace the enchanting melodies and resonant vibrations, and let the healing power of sound be a constant companion on your journey of personal growth and spiritual expansion.

____

🌞 If you enjoy my posts, please consider donating to my energies 🌞

✨🔮 Request a Tarot Reading Here 🔮✨

____

With love, from a Sappy Witch 🔮💕

Blessed be. 🕊✨

#soundhealing#healingvibrations#mind body soul#mind body spirit#mind body connection#harmony#harmony within#self discovery#wellbeingjourney#spiritualexpansion#dailypractice#holistichealing#soundtherapy#innerbalance#positivevibes#harmoniousliving#soulfuljourney#wellness#musicforthesoul#selfcare#spiritualgrowth#meditation#mindfulness#positivemindset#healingjourney#inner harmony#holisticwellness#vibrationalhealing#positiveenergy#selflove

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

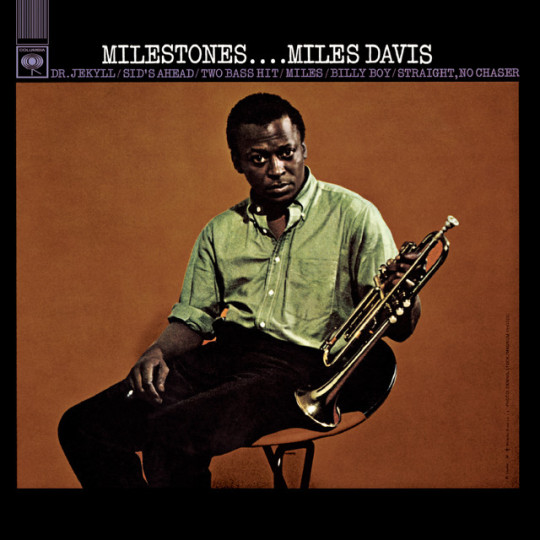

Milestones - Miles Davis (1958 Review)

One of the three Miles Davis albums I have heard, we'll get to another one of those albums much later, Milestones was a transitional album for Davis in 1958. It was still showing him in his Bebop and Hard Bop phase, but he was also showing hints of his newfound knowledge of "modal jazz", where you Improvise not over chord changes, but modes. Davis would perfect this album on his seminal album Kind of Blue a year later, but since that's not part of the "10s" Revisited series it's gonna be a while before I review that album. Though the one time I did hear the album back in 2021, it has a really good stereo mix for 1959. Anyways, the album case in point.

We start off with the opening track. Dr. Jackle, which I thought was just fairly average fast bebop. A rare moment other than the 1984 New Edition self-titled where I though that the opening track was the weakest on the whole album. But back to the song, all I can say about this song is that the double bass, played by Paul Chambers, sounds like the strings are being bowed rather than fingerpicked when played really fast. Much like on Sonny Rollins' Saxophone Colossus, the second track is a complete contrast from the previous in terms of speed, this case being the song Sid's Ahead. This is the longest song on the album at 13 minutes. Because it's at a slower speed, the improvisation is much more noticeably melodic, and I like how much minimalism the backbeat of the bass and drums are backing the horn solos before the piano, played by Red Garland, joins in during the second half of the song. The speed picks back up with track 3, Two Bass Hits, for some reason I can see the melodic intro and outro of this song somewhat fitting as background music in the scene of an 90s or very early 2000s anime. Unlike Dr. Jackle I actually enjoyed the Improvisation here a lot more, It's not as in your face and all over the place, but there are some melodic elements still there. Not a bad song for the side one closer.

Side 2 is the golden run of this album, back to back home runs. It starts off with the albums title track, Milestones(originally called Miles). What I said about the background music in an anime applies here a lot more. This song is also one of the earliest noticeable hints showing Davis's experimentation with Model Jazz that he would later perfect on albums like Kind of Blue a year later. Moving from between G Dorian or A Aoliean. The next song, Billy Boy, is a beautiful sounding song with Red Gardland fronting in the song. Just a piano, bass and drums, no horns. The album closes with Straight No Chaser, another long song at almost 11 minutes long, which is also my favorite "long song" on this album. With each member giving time to improvise in their solos, everyone sounds remarkable.

The only other similarity this album has to Saxophone Colossus, is that both albums are exactly 9 out of 10s

Listen to the album here

#music#music review#album review#album#music album#jazz#miles davis#modal jazz#1958#bebop jazz#50s jazz

3 notes

·

View notes