#nobel prize of mathematics

Link

Michel Talagrand, a distinguished mathematician, has been awarded the prestigious Abel Prize for his groundbreaking contributions to the study of randomness. This accolade underscores his remarkable achievements and their profound impact on various scientific disciplines.

The Abel Prize, established in 2001 by the Norwegian government, is one of the most esteemed awards in mathematics. Named after the renowned Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel, it recognizes outstanding contributions to the field and is often referred to as the Nobel Prize of Mathematics.

0 notes

Text

In 1952, these two men, James Watson and Francis Crick, claimed to have discovered the double helical structure of DNA. In 1962, they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine.

Unbeknownst to most at the time, they stole their work from female chemist, Rosalind Franklin. These two men are disgusting misogynists. Science teachers of Tumblr, I beg you to stop posting photos of the men who actively suppressed a woman who made one of the greatest scientific discoveries of all time.

#james watson#francis crock#rosalind franklin#nobel prize#dna#science#scienceblr#medicine#chemistry#chem#math#mathematics#1960s

615 notes

·

View notes

Text

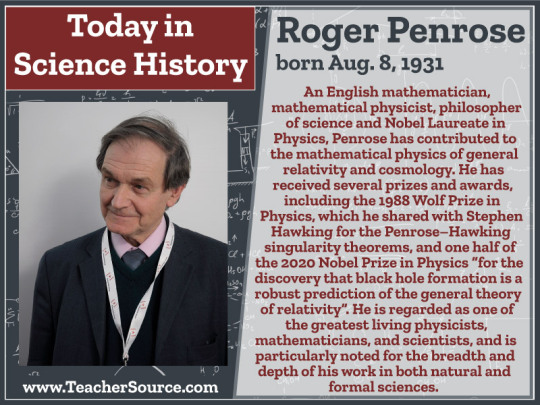

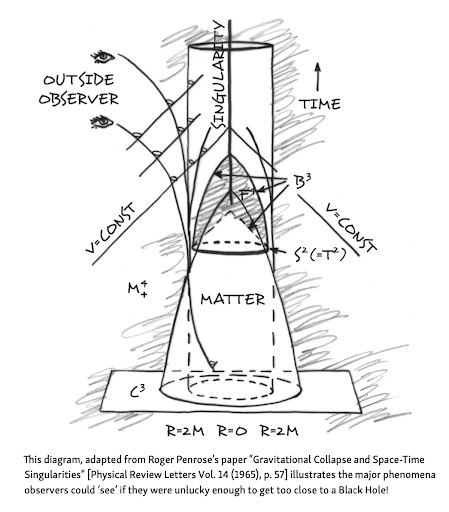

Roger Penrose was born on August 8, 1931. A British mathematician, mathematical physicist, philosopher of science and Nobel Laureate in Physics. Penrose has contributed to the mathematical physics of general relativity and cosmology. He has received several prizes and awards, including the 1988 Wolf Prize in Physics, which he shared with Stephen Hawking for the Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems, and one half of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics "for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity". He is regarded as one of the greatest living physicists, mathematicians, and scientists, and is particularly noted for the breadth and depth of his work in both natural and formal sciences.

#roger penrose#mathematicians#mathematics#general relativity#cosmology#singularity#nobel prize#nobel prize winners#science#science history#science birthdays#on this day#on this day in science history

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

•Andrea M. Ghez•

#It looks fuzzy but im hoping that’s just the app being silly#steminist#physics#science#stem#mathematics#maths#sub-at-omicsteminist#nobel prize#black holes#astonomy#space#women in stem#women in science#women’s history

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Beautiful Mind (2001, Ron Howard)

18/06/2024

#a beautiful mind#film#2001#ron howard#mathematics#nobel prize#John Forbes Nash Jr#russell crowe#1947#princeton university#antisocial personality disorder#Formula#Doctor of Philosophy#game theory#adam smith#research#massachusetts institute of technology#Boston#cold war#the pentagon#Number#moscow#cryptography#Geographic coordinate system#united states#secret service#United States Department of Defense#classified information#russians#Suitcase nuclear device

0 notes

Text

#him#we#us#them#native terrestrial#physics#biology#chemistry#mathematics#literature#economics#nobel prize#Switzerland

0 notes

Text

Einstein Unleashed!

#Einstein#sticker#genius#iconic#detailed#inspiration#science#physicist#intellect#imagination#creativity#relativity#theory#E=mc²#academia#mathematics#physics#Nobel Prize#curiosity#revolution#mind-blowing#awe-inspiring#deep thinking#innovation#influential#thought-provoking#wisdom#renowned#legendary#abstract thinking

0 notes

Text

1 Nobel Prize in Chemistry - The Development of Multiscale Models for Complex Chemical Systems

2 Nobel Prize in Chemistry - Quasiperiodic Crystals

3 Nobel Prize in Chemistry - Decoding the Structure and The Function of The Ribosome

4 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences - Repeated Games

5 Nobel Prize in Chemistry – Ubiquitin, Deciding the Fate of Defective Proteins in Living Cells

6 Nobel Prize in Economics - Human Judgment and Decision-Making Under Uncertainty

7 Fields Medal Award in Mathematics

8 Turing Award - Machine Reasoning Under Uncertainty

9 Turing Award - Nondeterministic Decision-Making

10 Turing Award - The Development of Interactive Zero-Knowledge Proofs

11 Turing Award - Developing New Tools for Systems Verification

12 Vine Seeds Discovered from The Byzantine Period

13 The World’s Most Ancient Hebrew Inscription

14 Ancient Golden Treasure Found at Foot of Temple Mount

15 Sniffphone - Mobile Disease Diagnostics

16 Discovering the Gene Responsible for Fingerprints Formation

17 Pillcam - For Diagnosing and Monitoring Diseases in The Digestive System

18 Technological Application of The Molecular Recognition and Assembly Mechanisms Behind Degenerative Disorders

19 Exelon – A Drug for The Treatment of Dementia

20 Azilect - Drug for Parkinson’s Disease

21 Nano Ghosts - A “Magic Bullet” For Fighting Cancer

22 Doxil (Caelyx) For Cancer Treatment

23 The Genetics of Hearing

24 Copaxone - Drug for The Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis

25 Preserving the Dead Sea Scrolls

26 Developing the Biotechnologies of Valuable Products from Red Marine Microalgae

27 A New Method for Recruiting Immune Cells to Fight Cancer

28 Study of Bacterial Mechanisms for Coping with Temperature Change

29 Steering with The Bats 30 Transmitting Voice Conversations Via the Internet

31 Rewalk – An Exoskeleton That Enables Paraplegics to Walk Again

32 Intelligent Computer Systems

33 Muon Detectors in The World's Largest Scientific Experiment

34 Renaissance Robot for Spine and Brain Surgery

35 Mobileye Accident Prevention System

36 Firewall for Computer Network Security

37 Waze – Outsmarting Traffic, Together

38 Diskonkey - USB Flash Drive

39 Venμs Environmental Research Satellite

40 Iron Dome – Rocket and Mortar Air Defense System

41 Gridon - Preventing Power Outages in High Voltage Grids

42 The First Israeli Nanosatellite

43 Intel's New Generation Processors

44 Electroink - The World’s First Electronic Ink for Commercial Printing

45 Development of A Commercial Membrane for Desalination

46 Developing Modern Wine from Vines of The Bible

47 New Varieties of Seedless Grapes

48 Long-Keeping Regular and Cherry Tomatoes

49 Adapting Citrus Cultivation to Desert Conditions

50 Rhopalaea Idoneta - A New Ascidian Species from The Gulf of Eilat

51 Life in The Dead Sea - Various Fungi Discovered in The Brine

52 Drip Technology - The Irrigation Method That Revolutionized Agriculture

53 Repair of Heart Tissues from Algae

54 Proof of The Existence of Imaginary Particles, Which Could Be Used in Quantum Computers

55 Flying in Peace with The Birds

56 Self-Organization of Bacteria Colonies Sheds Light on The Behaviour of Cancer Cells

57 The First Israeli Astronaut, Colonel Ilan Ramon

58 Dr. Chaim Weizmann - Scientist and Statesman, The First President of Israel, One of The Founders of The Modern Field of Biotechnology

59 Aaron Aaronsohn Botanist, Agronomist, Entrepreneur, Zionist Leader, and Head of The Nili Underground Organization

60 Albert Einstein - Founding Father of The Theory of Relativity, Co-Founder of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem

61 Maimonides - Doctor and Philosopher

Source

@TheMossadIL

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

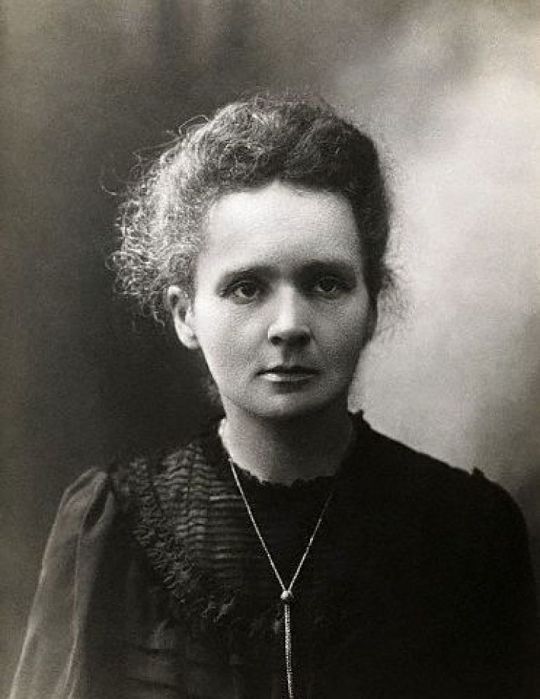

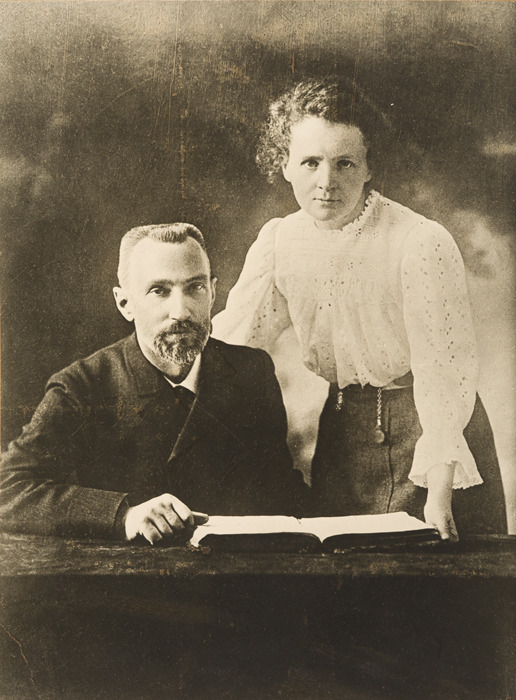

Maria Skłodowska-Curie. That's it, that's the post.

As per my poll, here's a post on MSC!

This post began as a bit of a messy thing. I wanted to write about MSC because she was a brilliant Polish woman who became one of the most important scientists of modern chemistry and physics and I, as a Polish woman and a science major, admire her greatly. But the whole thing was vague and lacked direction. I received some kindly advice though and decided to focus on this: what was Maria like? Everybody knows she had an exceptional mind, that she had close ties with Paris, that she discovered radium and polonium, that she received the Nobel prize twice… But did you know she was said to have “serious, gray eyes” or that her initial plan was to spend her life working as a teacher or that she loved her homeland deeply? Underneath her doubtlessly exceptional achievements she was a person, and I’d love to take a look at that.

Maria Skłodowska ("skwo-DOV-ska") was born on 7 November 1867 in Warsaw under Russian occupation. Her father was a mathematics and physics teacher, so it may seem natural that little Maria took an interest in science, but as a child she was a phenomenal student in general, no matter the subject; she read a lot of books, and she learnt to read very early. She was considered very gifted.

Her family wasn’t rich by any means. Maria’s father – a Polish man, a school teacher under the tzar’s merciless reign – knew very well he couldn’t afford to give all his children the education he wanted for them, not to mention neither Maria nor her older sister Bronia were allowed to attend university in occupied Poland. Making their dreams come true – studying at the Sorbonne – depended on the money they didn’t have.

At 17 Maria made a decision: she was going to work as a teacher while Bronia pursued medicine in Paris with the help of the money earned by Maria. After Bronia’s graduation they would switch: Bronia was going to work as a doctor while Maria attended university.

It was by no means an easy task. During the following years Maria had to withstand not only immensely hard work and a longing for learning, but also unfair employers, lack of respect, and heartbreak. But she persisted. She was 24 when finally she was able to pack up and take the train to Paris.

[source]

Soon after taking up her studies at the Sorbonne did Maria realize how far behind the other students she was: they were able to pursue an official education in a free country, something she’d never gotten to experience before. She had been an excellent student back in Poland, a fluent French speaker, but now it turned out her knowledge was lacking. Obviously, this couldn’t discourage her. Bronia’s husband Kazimierz wrote in a letter to her father that Maria would spend entire days at her university, only coming home in the evening. She worked admirably hard to catch up. And she was happy: at long last she could study science and mathematics in depth, the way she had longed to do for so many years.

Of course, money never stopped being an issue. Even with her father’s and sister’s help, she was still poor. She definitely wasn’t eating enough. In winter, she was cold. Other than that, she mostly gave up on her colleagues, refused to waste her time on “insignificant” things: that is, everything but studying, unfolding the secrets of chemistry and physics, practicing her laboratory skills. She was living and breathing science.

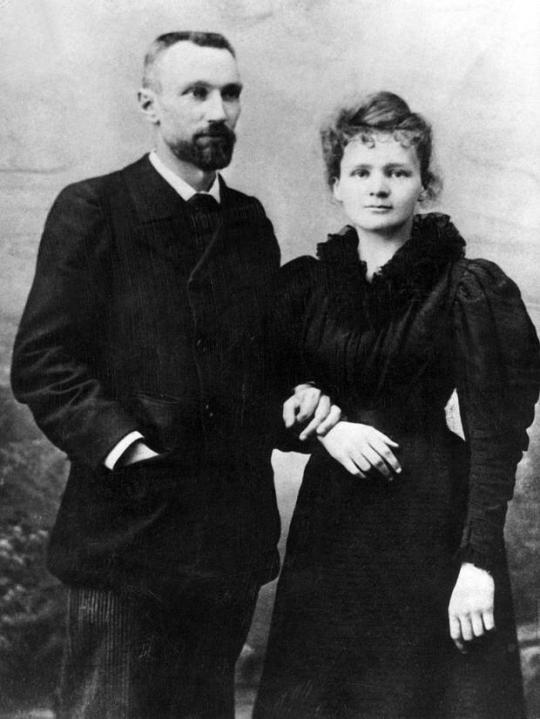

[left / right]

Pierre Curie was older, an exceptional physicist, charming and calm, still unmarried at 35 – he wouldn’t love a woman who couldn’t be first and foremost his intellectual partner. But Maria wasn’t looking for love and she certainly wasn’t looking for a marriage. She had a degree in physics, was on her way to get a degree in mathematics as well, all the while working on the magnetism of steel. And indeed, when they met through a professor who thought Pierre might be of help to young Maria, it was mostly curiosity, mutual respect, and primarily a great scientific interest that bloomed between them and brought them closer together.

Maria didn’t give in easily. All along her plan had been to earn her degrees and return to Warsaw, to her elderly father, and remain working as a teacher for the rest of her life. But there’s no doubt that when she eventually agreed to marry Pierre, it was out of genuine, deep love. They had a sincere, precious connection, both emotional and intellectual.

Did you know Maria and Pierre loved to travel the countryside on their bikes? They did. It’s how they spent most of their time together after their wedding. And not for a moment did they forget about their shared passion for science – they discussed it even during their travels. They lived together and they worked together. Their first child Irène – future Nobel prize winner as well! – was born in September 1897, Ève – their younger daughter – seven years later.

Pierre’s family adored Maria, Maria’s family loved Pierre. The two of them would frequently visit Pierre’s parents and they continued their biking trips, but other than that their life was utterly devoted to science. I know, it sounds like I’m exaggerating, but it’s true. Along with the fact they always had very little money, work was all they had.

Radium appeared in Maria’s life when she was working on her doctorate. Her laboratory was cold, damp, and badly equipped, but it seems to me Maria’s determination was inexhaustible. She began by studying uranium, but she soon figured out she had to include other elements in her research as well in order to solve the mystery at hand. It was only after a year of this work that Maria realized she might have discovered an element previously unknown.

Pierre was interested in Maria’s research before, but – save from the occasional advice as an older and more experienced scientist – he mostly left her to do her own thing while he focused on his crystals. At this point however, he was so intrigued he abandoned his research to work with Maria on her project. In 1898 (two years into Maria’s PhD work!) they published a paper together – in it they announced the discovery of a new element: polonium, named after Maria’s beloved homeland. Later that year, they did the same for radium. They coined the term “radioactivity”.

Maria kept a meticulous journal, not only for her laboratory work. She was carefully tracking their spending as well as Irène’s development, the way she learnt to walk and speak and play with their cat.

And so, her life continued: filthy, hard work in the infamous shed, a ton of an ore for less than a gram of product (!), countless papers published with her dearest husband, watching their daughter grow, earning her doctorate degree; then, in 1903, her first Nobel prize (along with her husband and Henri Becquerel).

The Nobel prize brought Maria and Pierre fame – and it was a tragedy. For them, at least. Modest and humble as they were, they couldn’t stand the journalists almost storming their garden, going as far as “describing [their] black and white cat [in the newspapers]” as Pierre said in a letter to a friend. I allowed myself to translate a piece of a letter that Maria sent to her brother in 1904 amid the post-Nobel craze, as it’s both sad and hilarious:

“I wish you health [for your name-day], well-being for all of your family, and for you never to experience the sort of correspondence and assault that we are now subjected to.

Ever since that accursed Nobel prize we’ve been unable to do anything, and I’m beginning to ask myself if the money we received will be of any consolation, as, after all, the people who sell me meat, coal, sugar, etc. are richer than me yet they do not experience such sorrows.

[…] and yesterday some American wrote to me, asking for permission to name a race horse after me.”

Maria’s life took a truly sharp turn when Pierre died in an accident in 1906. Despite the tragedy that irreparably crushed her heart, she never ceased her work. She became a professor, organized classes for her and her friends’ kids, ran the Radium Institute, continued her research, received her second Nobel prize. During World War I it was her mobile X-ray machines that saved countless lives: she was active and involved, operating the machines with her older daughter and teaching others how to do it.

[left / right]

She lived long enough to see her dear, beloved Poland become an independent country once more. To the very end she remained humble and uninterested in fame, hardworking and dedicated entirely to science.

I based this post mostly on Madame Curie by her daughter Ève which I highly recommend!

#in the end i kept it long as you can see#but i think its consistent :)#mine#op#chemistry#chemblr#physics

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

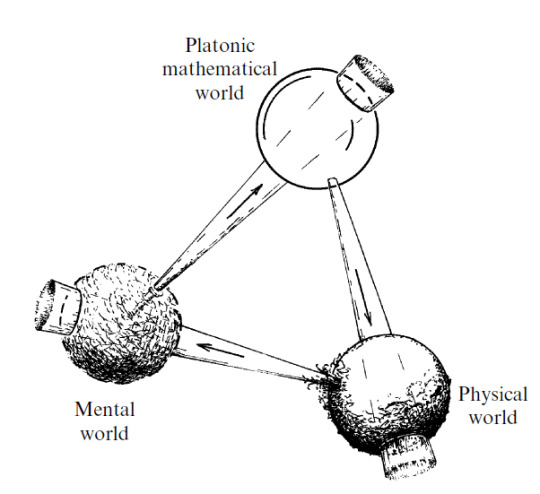

Sir Roger Penrose

To me, the world of perfect forms is primary (as was Plato’s own belief) — its existence being almost a logical necessity — and both the other two worlds are its shadows.

Sir Roger Penrose, born on August 8, 1931, in Colchester, Essex, England, is a luminary in the realm of mathematical physics. His journey began with a Ph.D. in algebraic geometry from the University of Cambridge in 1957, and his career has spanned numerous prestigious posts at universities in both England and the United States. His work in the 1960s on the fundamental features of black holes, celestial bodies of such immense gravity that nothing, not even light, can escape, earned him the 2020 Nobel Prize for Physics.

Penrose’s work on black holes, in collaboration with Stephen Hawking, led to the ground-breaking discovery that all matter within a black hole collapses to a singularity, a point in space where mass is compressed to infinite density and zero volume. This revelation illuminated our understanding of these enigmatic cosmic entities.

His work did not stop at the theoretical; he also developed a method of mapping the regions of space-time surrounding a black hole, known as a Penrose diagram. This tool allows us to visualize the effects of gravitation upon an entity approaching a black hole, providing a window into the heart of these celestial mysteries.

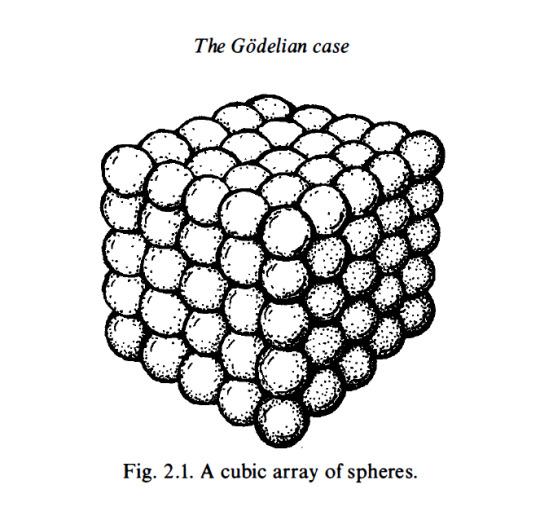

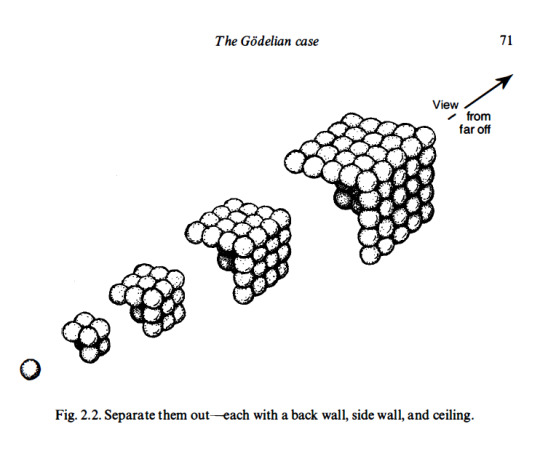

Within Penrose’s chapter, “The Godelian Case” (from “The Road to Reality”) the profound implications of Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems are examined in relation to the connection between mathematics and geometry. Specifically, Penrose’s attention centers on the model depicted in Figure 2.1, which portrays a cubic array of spheres. Through this visual representation, Penrose explores the intricate relationship between geometry and mathematical understanding.

By introducing the model of a cubic array of spheres, Penrose highlights the fundamental role of spatial arrangements in mathematical cognition. This geometrical structure serves as a metaphorical embodiment of mathematical concepts, illustrating how spatial configurations can stimulate cognitive processes and facilitate intuitive comprehension of mathematical truths. The intricate interplay between the arrangement of spheres within the model and the underlying principles of mathematics encourages contemplation on the deep-rooted connections between geometry, spatial reasoning, and abstract mathematical thought.

Penrose’s utilization of the cubic array of spheres underscores his broader philosophical framework, which challenges reductionist accounts of human cognition that rely solely on formal systems or computational models. Through this geometrical representation, he advocates for a more holistic understanding of mathematical insight, one that recognizes the essential role of geometric intuition in shaping human understanding.

By looking at the intricate connection between mathematics and geometry, Penrose prompts a re-evaluation of the mechanistic view of cognition, emphasizing the need to incorporate spatial reasoning and intuitive geometrical understanding into comprehensive models of human thought.

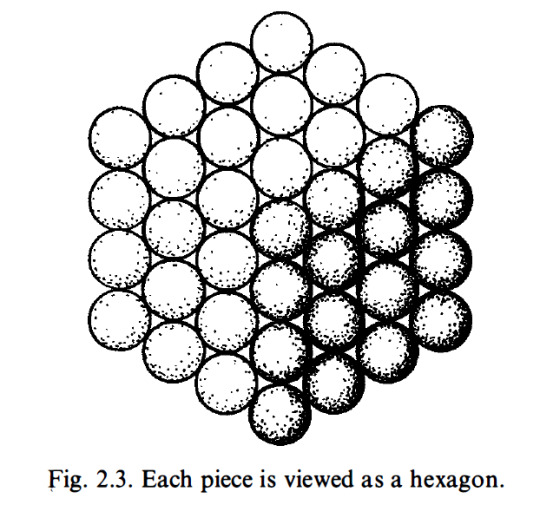

(E) Find a sum of successive hexagonal numbers, starting from 1 , that is not a cube.

I am going to try to convince you that this computation will indeed continue for ever without stopping. First of all, a cube is called a cube because it is a number that can be represented as a cubic array of points as depicted in Fig. 2. 1 . I want you to try to think of such an array as built up successively, starting at one corner and then adding a succession of three-faced arrangements each consisting of a back wall, side wall, and ceiling, as depicted in Fig. 2.2.

Now view this three-faced arrangement from a long way out, along the direction of the corner common to all three faces. What do we see? A hexagon as in Fig. 2.3. The marks that constitute these hexagons, successively increasing in size, when taken together, correspond to the marks that constitute the entire cube.

This, then, establishes the fact that adding together successive hexagonal numbers, starting with 1 , will always give a cube. Accordingly, we have indeed ascertained that (E) will never stop.

Penrose’s work is characterized by a profound appreciation for geometry. His father, a biologist with a passion for mathematics, introduced him to the beauty of geometric shapes and patterns at a young age. This early exposure to geometry shaped Penrose’s unique approach to scientific problems, leading him to develop new mathematical notations and diagrams that have become indispensable tools in the field. His creation of the Penrose tiling, a method of covering a plane with a set of shapes without using a repeating pattern, is a testament to his innovative thinking and his deep understanding of geometric principles.

His fascination with geometry extended beyond the realm of mathematics and into the world of art. He was deeply influenced by the work of Dutch artist M.C. Escher, whose intricate drawings of impossible structures and infinite patterns captivated Penrose’s imagination. This encounter with Escher’s art led Penrose to explore the interplay between geometry and art, culminating in his own contributions to the field of mathematical art. His work in this area, like his scientific research, is characterized by a deep appreciation for the beauty and complexity of geometric forms.

In geometric cognition, Penrose’s work has the potential to make significant contributions. His unique perspective on the role of geometry in understanding the physical world, the mind, and even art, offers a fresh approach to this emerging field. His belief in the power of geometric thinking, as evidenced by his own ground-breaking work, suggests that a geometric approach to cognition could yield valuable insights into the nature of thought and consciousness.

Objective mathematical notions must be thought of as timeless entities and are not to be regarded as being conjured into existence at the moment that they are first humanly perceived.

I argue that the phenomenon of consciousness cannot be accommodated within the framework of present-day physical theory.

His Orch OR theory posits that consciousness arises from quantum computations within the brain’s neurons. This bold hypothesis, bridging the gap between the physical and the mental, has sparked intense debate and research in the scientific community.

Penrose’s work on twistor theory, a geometric framework that seeks to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity, is a testament to his belief in the primacy of geometric structures. This theory, which represents particles and fields in a way that emphasizes their geometric and topological properties, can be seen as a metaphor for his views on cognition. Just as twistor theory seeks to represent complex physical phenomena in terms of simpler geometric structures, Penrose suggests that human cognition may also be understood in terms of fundamental geometric and topological structures.

This perspective has significant implications for the field of cognitive geometry, which studies how humans and other animals understand and navigate the geometric properties of their environment. If Penrose’s ideas are correct, our ability to understand and manipulate geometric structures may be a fundamental aspect of consciousness, rooted in the quantum geometry of the brain itself.

The final conclusion of all this is rather alarming. For it suggests that we must seek a non-computable physical theory that reaches beyond every computable level of oracle machines (and perhaps beyond).

— Roger Penrose, Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness

#geometrymatters#roger penrose#geometric cognition#cognitive geometry#consciousness#science#research#math#geometry

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brotherhood, Pt. 10

Teyla and Ford exchange glances, awaiting for a sign from Sheppard telling them to go ahead with their plan. But Sheppard has a sudden flash of insight, figuring out what the puzzle is. Sheppard, who originally figured out that the tablets contain an Ancient numbering system, realizes that the puzzle is a "magic square,"* the concept of which is familiar to anyone practicing recreational mathematics, which Sheppard seems to do. And while solving the puzzle was not central to their plan, he's still excited over having figured it out:

Sheppard: I got it!

McKay: What?

Sheppard: The Brotherhood of 15.

McKay: What about it?

Sheppard: The numbers one to nine can be put in a three-by-three grid so they add up to 15 in every direction.

McKay is impressed with this, to say the least. Before Sheppard's excited outburst, his eyes kept shifting between him and the puzzle like his mind was still working on it, working on saving Sheppard, but at the same time he was committing Sheppard's countenance to memory. But as soon as Sheppard breaks the silence, McKay steps forward. It's not a conscious decision. He had stepped back because Sheppard asked him to but it's not where he wanted to be. It's not where he belongs. His place is next to Sheppard. He doesn't even really care why Sheppard exclaimed, it gave him an excuse to do what he wanted to do anyway. To get back near him.

The angle and framing of this scene is interesting, too. We are looking at Sheppard from McKay's viewpoint and the most prominent feature of the shot is Sheppard's bare neck. There is a long stretch of naked neck placed right in front of McKay's face and you can see the muscles moving, tendons stretching. There is really no need to frame the shot like this, to make one of his erogenous zones the central point of focus. It is undeniably erotic and this is really not the time to be caught up on that, not for us and certainly not for McKay.

While McKay may have the reputation of a person that does not like to share credit or give praise for other people's accomplishments, this certainly does not apply to Sheppard (as already seen in Hot Zone, S01E13). He is genuinely so happy for Sheppard that he got it right. He also seems to solve the puzzle fairly quickly (recognizing it as a magic square and solving the magic square are two different things). But as impressed as he is that Sheppard seems to have recognized the puzzle, he's even more impressed over his explanation as to how:

McKay: Oh, you're right. How'd you know that?

Sheppard: It was on a Mensa test.

McKay: You're a member of Mensa?

People have written before about how genuinely intelligent people don't care about Mensa and how Sheppard takes pride in his intelligence but in a very different way to McKay. I mean, sure. McKay does not need Mensa to prove his intelligence, he has more than one degree, is an actual world-class published Academic, we're even made to believe he might be a Nobel prize candidate material. Obviously he does not need a membership in Mensa to prove anyone that he is intelligent. But as a social club? For someone that more than likely has been isolated from his peers because of his intelligence from a very young age, having a social environment where it's not a handicap might appeal to him. And from how he describes his involvement with Mensa on the show, it is precisely as a social club that he views it. It's like his high school chess club, only for adults. And it means something to him. And it's not that Sheppard is Mensa-material that excites him but the possibility that they might partake in this together. It's a part of his world, and he wants to share his entire world with Sheppard.

Now, USAF fighter pilots do undergo an aptitude test and their average IQ is much higher than that of the population in general. Would-be officers also take a qualifying test. Sheppard seems to have tested even higher than this higher-than-average average. It's possible that his taking of the Mensa test has nothing to do with the military (as the military employs its own aptitude tests), it could just be something he has done for fun or in some other context. Further, test pilots undergo a whole battery of cognitive aptitude tests. But it's also interesting that there is a required aeromedical evaluation of a pilot's cognitive functioning when "when there is concern regarding a pilot candidate’s cognitive disposition related to medical and/or psychological illness/injury," such as depression or anxiety. He may have had to undergo tests between Afghanistan and the Antarctic, and hence may have an entirely different association with regards to intelligence testing than your regular person, and certainly different from that of McKay.

But what's really curious is that McKay later expresses actual surprise that Sheppard had not told him this which, for one, informs us about the fact that Sheppard has told McKay a lot of things for him to believe that he knows most things about him by this time. Further, it implies that there may have been a reason that he had not chosen to share this with him... yet. Over the seasons we are hinted that McKay does know things about Sheppard that must be both private and painful but it seems that this is too early days for him to have learned everything everything about Sheppard. And finally, it shows us how keen McKay is to learn new things about Sheppard.

We see Gen. O'Neill habitually actively play dumber than he is as a means of gaining the upper hand by making other people reveal theirs. While in some ways they are alike, Sheppard does not do precisely this. Sheppard knows that he's not dumb and probably does at least somewhat pride himself on his intelligence, even if formal accolades seem to be meaningless to him. And, given what we later learn of his family background, he would have been expected to achieve certain things in life (Sheppard says that his father's idea of rebellion was "going to Stanford instead of Harvard") but when a family has accumulated a certain level of wealth and prestige, accolades do become more of a garnish than actual achievements. For the upper echelons of society, showing off wealth, status, and ability is crass and suitably downplaying where you are better equipped than your current company is expected.

Sheppard likely has been "the smartest man in the room" in most of the rooms he has been in over the course of his life which would give him a certain sense of superiority, even arrogance (and he does tell McKay later, in Harmony S04E14, that people often dislike things in others that they dislike in themselves and McKay's perceived arrogance is clearly the side of him that is most difficult for Sheppard to stomach). But he eschews authority figures which, ultimately, derives from his difficult relationship with his father and that has resulted in him putting on a kind of a slacker performance, an attempt at proving to the world at large and especially himself that he is nothing like his father (and, while we're on the topic of disliking things in others that you dislike in yourself, here he is, the highest military commander of an entire people, required to order people around). And slackers, they rebel against teachers and at least pretend to do poorly in school. Slackers don't care how they are viewed by others (except where they so obviously do). So, while he is smart, he has also had to project nonchalance for seeming smart and especially toward formal education. Befriending Rodney McKay was not an easy thing for him. It forced him to take a long, hard look at himself.

Now, while in universe Rodney McKay is one of the smartest people alive, there are areas where Sheppard is better than he is. Intelligence is not one thing, it's not just aptitude in theoretical or applied physics. McKay can do many things that he could never do, but there are likewise many things (spatial awareness, observing flight trajectories) Sheppard can do that he never could that aren't necessarily the result of their different educations but of different natural aptitudes. It is isolating to be smarter than one's peers, it is isolating to understand things that other people don't seem to understand, to experience more depth, to suffer the human condition more acutely. This, they have both experienced. And meeting someone that challenges you when you have never really been challenged is not easy--not for either of them. Because of his position, his degrees, his formal education, simply through what his job is on the expedition as the leader of the science team, both Sheppard and McKay think that McKay is more intelligent than Sheppard. And as being intelligent has played a different role in the construction of their respective identities, they have different feelings about this state of affairs.

Sheppard begrudges this and projects his own arrogance on McKay (and, granted, McKay can be arrogant, although mostly he is just self-aware and doesn't bother beating around the bush for the sake of efficiency; when he met Carter he was correct in that he did have a much better theoretical understanding of the mechanics of the stargate) where McKay is really and truly happy that he can meet Sheppard as something of an equal. He enjoys his work and feeling smart probably got him through high school but he has no need of being smart, that in and of itself is meaningless to him all the way up until (The Shrine, S05E06) he believes that losing this aspect of himself means he can no longer be the man John Sheppard loves (and he is wrong in that, too; we see McKay nearly killed by both extreme ends of the intelligence spectrum and John Sheppard loves him through both experiences). If his intelligence got between himself and Sheppard, he would gladly give it up (unless he needed it to save the man, that's even more important--and he so frequently does need it for that purpose). And finding out that Sheppard actually can meet him at least roughly on his level? He fucking loves that. It makes him feel even closer to him. He has entirely and completely forgotten where they even are, he's so overjoyed about this:

McKay: You're a member of Mensa?

Sheppard: No, but I took the test.

McKay: When?

Sheppard: You want to talk about this now, Rodney?

Rodney McKay did, in fact, want to talk about this now. They have again returned to this bubble where only the two of them exist. They were, briefly, forced to exit this bubble what with the life-threatening situation and an absolute monster of a man holding them hostage but they keep returning to this bubble, again and again, like it's their natural habitat, their equilibrium. They belong together and can only be separated momentarily before the rubber band stretching between them pulls them back to each other.

Like I mentioned, recognizing the puzzle as a magic square and solving the puzzle are two different things and it's worth highlighting that they solve the puzzle together, and they solve it really fast. They are working seamlessly as one, like we have seen them do before and as we'll see them do again.

This is also some of the happiest we have seen Sheppard, and it's certainly not for being relieved at the thought that they might be saved now that they solved the puzzle since he was about to signal the others to get ready to set off the flash bangs. He is simply happy to have just solved a math puzzle together with McKay, that's like, two of his favourite things. It's only Kolya's gleeful interjection that snaps him back to the sticky situation they are currently in.

But notice how Sheppard does not need to use words to get McKay to step back, this time. Previously, he did not look at McKay as he asked him to step back. Now, he gives him but a brief look and McKay gets the message. McKay can read it off of his face. It's not telepathy. There is nothing mystical about it, weird though Sheppard may have called it in the previous episode. He has simply spent enough time looking at John Sheppard's face that it is an open book to him. And knowing this, Sheppard was trying to give him but brief glimpses of his thoughts lest Kolya become the wiser.

Sheppard prepares to lay his hands on the hand-prints.

Continued in Pt. 11

-* Just as an aside, the third order magic square in the episode is also a child-bearing charm in Medieval Arabic alchemy which the writers proooobably did not have in mind, but given the references we have had to children all season long, it's interesting to see Sheppard and McKay work on it together.

#stargate atlantis#sga meta#sga#john sheppard#sheppard is bi#rodney mckay#rodney is gay#ep. the brotherhood#ep. the shrine#ep. outcast#ep. harmony

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 Nobel Prize in Chemistry - The Development of Multiscale Models for Complex Chemical Systems

2 Nobel Prize in Chemistry - Quasiperiodic Crystals

3 Nobel Prize in Chemistry - Decoding the Structure and The Function of The Ribosome

4 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences - Repeated Games

5 Nobel Prize in Chemistry – Ubiquitin, Deciding the Fate of Defective Proteins in Living Cells

6 Nobel Prize in Economics - Human Judgment and Decision-Making Under Uncertainty

7 Fields Medal Award in Mathematics

8 Turing Award - Machine Reasoning Under Uncertainty

9 Turing Award - Nondeterministic Decision-Making

10 Turing Award - The Development of Interactive Zero-Knowledge Proofs

11 Turing Award - Developing New Tools for Systems Verification

12 Vine Seeds Discovered from The Byzantine Period

13 The World’s Most Ancient Hebrew Inscription

14 Ancient Golden Treasure Found at Foot of Temple Mount

15 Sniffphone - Mobile Disease Diagnostics

16 Discovering the Gene Responsible for Fingerprints Formation

17 Pillcam - For Diagnosing and Monitoring Diseases in The Digestive System

18 Technological Application of The Molecular Recognition and Assembly Mechanisms Behind Degenerative Disorders

19 Exelon – A Drug for The Treatment of Dementia

20 Azilect - Drug for Parkinson’s Disease

21 Nano Ghosts - A “Magic Bullet” For Fighting Cancer

22 Doxil (Caelyx) For Cancer Treatment

23 The Genetics of Hearing

24 Copaxone - Drug for The Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis

25 Preserving the Dead Sea Scrolls

26 Developing the Biotechnologies of Valuable Products from Red Marine Microalgae

27 A New Method for Recruiting Immune Cells to Fight Cancer

28 Study of Bacterial Mechanisms for Coping with Temperature Change

29 Steering with The Bats

30 Transmitting Voice Conversations Via the Internet

31 Rewalk – An Exoskeleton That Enables Paraplegics to Walk Again

32 Intelligent Computer Systems

33 Muon Detectors in The World's Largest Scientific Experiment

34 Renaissance Robot for Spine and Brain Surgery

35 Mobileye Accident Prevention System

36 Firewall for Computer Network Security

37 Waze – Outsmarting Traffic, Together

38 Diskonkey - USB Flash Drive

39 Venμs Environmental Research Satellite

40 Iron Dome – Rocket and Mortar Air Defense System

41 Gridon - Preventing Power Outages in High Voltage Grids

42 The First Israeli Nanosatellite

43 Intel's New Generation Processors

44 Electroink - The World’s First Electronic Ink for Commercial Printing

45 Development of A Commercial Membrane for Desalination

46 Developing Modern Wine from Vines of The Bible

47 New Varieties of Seedless Grapes

48 Long-Keeping Regular and Cherry Tomatoes

49 Adapting Citrus Cultivation to Desert Conditions

50 Rhopalaea Idoneta - A New Ascidian Species from The Gulf of Eilat

51 Life in The Dead Sea - Various Fungi Discovered in The Brine

52 Drip Technology - The Irrigation Method That Revolutionized Agriculture

Repair of Heart Tissues from Algae

54 Proof of The Existence of Imaginary Particles, Which Could Be Used in Quantum Computers

55 Flying in Peace with The Birds

56 Self-Organization of Bacteria Colonies Sheds Light on The Behaviour of Cancer Cells

57 The First Israeli Astronaut, Colonel Ilan Ramon

58 Dr. Chaim Weizmann - Scientist and Statesman, The First President of Israel, One of The Founders of The Modern Field of Biotechnology

59 Aaron Aaronsohn Botanist, Agronomist, Entrepreneur, Zionist Leader, and Head of The Nili Underground Organization

60 Albert Einstein - Founding Father of The Theory of Relativity, Co-Founder of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem

61 Maimonides - Doctor and Philosopher

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1968, the American scholar Jerome M. Gilison described Soviet elections as a “psychological curiosity”—a ritualized, performative affirmation of the regime rather than a real vote in any sense of the word. These staged elections with their nearly unanimous official results, Gilison wrote, served to isolate non-conformists and weld the people to their regime.

Last Sunday, Russia completed the circle and returned to Soviet practice. State election officials reported that 87 percent of Russians had cast their vote for Vladimir Putin in national elections, giving the Russian president a fifth term in office. Not only were many of the reported election numbers mathematically impossible, but there was also no longer much of a choice: All prominent opposition figures had been either murdered, imprisoned, or exiled. Like in Soviet times, the election also welded Russians to their regime by serving as a referendum on Putin’s war against Ukraine. All in all, last weekend’s Soviet-style election sealed Putin’s transformation of post-Communist Russia into a repressive society with many of the features of Soviet totalitarianism.

Russia’s return to Soviet practice goes far beyond elections. A recent study by exiled Russian journalists from Proekt Media used data to determine that Russia is more politically repressive today than the Soviet Union under all leaders since Joseph Stalin. During the last six years, the study reports, the Putin regime has indicted 5,613 Russians on explicitly political charges—including “discrediting the army,” “disseminating misinformation,” “justification of terrorism,” and other purported crimes, which have been widely used to punish criticism of Russia’s war on Ukraine and justification of Ukraine’s defense of its territory. This number is significantly greater than in any other six-year period of Soviet rule after 1956—all the more glaring given that Russia’s population is only half that of the Soviet Union before its collapse.

In addition to repressive criminal charges and sentences, over the last six years more than 105,000 people have been tried on administrative charges, which carry heavy fines and compulsory labor for up to 30 days without appeal. Many of these individuals were punished for taking part in unsanctioned marches or political activity, including anti-war protests. Others were charged with violations of COVID pandemic regulations. Such administrative punishments are administered and implemented rapidly, without time for an appeal.

On March 4, 2022, a little over a week after the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, Russia’s puppet parliament rapidly adopted amendments to the Russian Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Code that established criminal and administrative punishments for the vague transgressions of “discrediting” the Russian military or disseminating “false information” about it. This widely expanded the repressive powers of the state to criminally prosecute political beliefs and activity. Prosecutions have surged since the new laws were passed, likely leading to a dramatic increase in the number of political prisoners in the coming years. In particular, punishments for “discrediting the army” or “justification of terrorism”—which includes voicing support for Ukraine’s right to defend itself—have resulted in hundreds of sentences meted out each year since the war began. The most recent such case: On Feb. 27, the 70-year-old co-chairman of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights group Memorial, Oleg Orlov, was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for “discrediting” the Russian military.

As the Proekt report ominously concludes, “[I]n terms of repression, Putin has long ago surpassed almost all Soviet general secretaries, except for one—Joseph Stalin.” While this conclusion is in itself significant, it is only the tip of the iceberg of the totalitarian state Putin has gradually and systematically rebuilt.

As in the Soviet years, there is no independent media in Russia today. The last of these news organizations were banned or fled the country after Putin’s all-out war on Ukraine, including Proekt, Meduza, Ekho Moskvy, Nobel Prize-winning Novaya Gazeta, and TV Dozhd. In their place, strictly regime-aligned newspapers, social media, and television and radio stations emit a steady drumbeat of militaristic propaganda, promote Russian imperialist grandeur, and celebrate Putin as the country’s infallible commander in chief. In another reprise of totalitarian practice, lists of banned books have been dramatically expanded and thousands of titles have been removed from the shelves of Russian libraries and bookstores. Bans have been extended to numerous Wikipedia pages, social media channels, and websites.

Human rights activists and independent civic leaders have been jailed, physically attacked, intimidated into silence, or driven into exile. Civic organizations that show independence from the state are banned as “undesirable” and subjected to fines and prosecution if they continue to operate. The most recent such organizations include the Andrei Sakharov Foundation, Memorial, the legendary Moscow Helsinki Group, and the EU-Russia Civil Society Forum. In their place, the state finances a vast array of pro-regime and pro-war groups, with significant state resources supporting youth groups that promote the cult of Putin and educate children in martial values to prepare them for military service. Then there are the numerous murders of opposition leaders, journalists, and activists at home and abroad. Through these various means, almost all critical Russian voices have been silenced.

Private and family life is also increasingly coming under the scope of government regulation and persecution. The web of repression particularly affects the LGBT community, putting large numbers of Russians in direct peril. A court ruling in 2023 declared the “international LGBT movement” extremist and banned the rainbow flag as a forbidden symbol, which was quickly followed by raids and arrests. Homosexuality has been reclassified as an illness, and Russian gay rights organizations have shut down their operations for fear of prosecution. Legislation aimed at reinforcing “traditional values”—including the right of husbands to discipline their wives—has led to the reduction in sentences and the decriminalization of some forms of domestic violence.

Many of the techniques of totalitarian control now operating throughout Russia were first incubated in territories where the Kremlin spread war and conflict. Chechnya was the first testing ground for widespread repression, including massive numbers of victims subjected to imprisonment, execution, disappearance, torture, and rape. Coupled with the merciless targeting of civilians in Russia’s two wars in Chechnya, these practices normalized wanton criminal behavior within Russian state security structures. Out of this crucible of fear and intimidation, Putin has shaped a culture and means of governing that were further elaborated in other places Russia invaded and eventually came to Russia itself.

In Russian-occupied Crimea and eastern Ukraine since 2014, there has been a widespread campaign of surveillance, summary executions, arrests, torture, and intimidation—all entirely consistent with Soviet practice toward conquered populations. More recently, this includes the old practice of forced political recantations: A Telegram channel ominously called Crimean SMERSH (a portmanteau of the Russian words for “death to spies,” coined by Stalin himself) has posted dozens of videos of frightened Ukrainians recanting their Ukrainian identity or the display of Ukrainian symbols. Made in conjunction with police operations, these videos appear to be coordinated with state security services.

In the parts of Ukraine newly occupied since 2022, human rights groups have widely documented human rights abuses and potential war crimes. These include the abduction of children, imprisonment of Ukrainians in a system of filtration camps that recall the Soviet gulags, and the systematic use of rape and torture to break the will of Ukrainians. Castrations of Ukrainian men have also been employed.

As Russia’s violence in Ukraine has expanded, so, too, has the acceptance of these abominations throughout the state and in much of society. As during the Stalin era, the cult of cruelty and the culture of fear are now the legal and moral standards. The climate of fear initially employed to assert order in occupied regions is now being applied to Russia itself. In this context, the murder of Alexei Navalny ahead of the presidential election was an important message from Putin to the Russian people: There is no longer any alternative to the war and repressive political order he has imposed, of which Navalny’s elimination is a part.

All the techniques and means of repression bespeak a criminal regime that now closely resembles the totalitarian rule of Stalin, whom Putin now fully embraces. After Putin first came to power in 1999, he often praised Stalin as a great war leader while disapproving of his cruelty and brutality. But as Putin pivoted toward war and repression, Russia has systematically promoted a more positive image of Stalin. High school textbooks not only celebrate his legacy but also whitewash his terror regime. There has been a proliferation of new Stalin monuments, with more than 100 throughout the country today. On state-controlled media, Russian propagandists consistently hammer away on the theme of Stalin’s greatness and underscore similarities between his wartime leadership and Putin’s. Discussion of Stalinist terror has disappeared, as has the memorialization of his millions of victims. Whereas only one in five Russians had a positive view of Stalin in the 1990s, polls conducted over the last five years show that number has risen to between 60 percent and 70 percent. In normalizing Stalin, Putin is not glossing over the tyrant’s crimes; rather, he is deliberately normalizing Stalin as a justification for his own war-making and repression.

Putin now resembles Stalin more closely than any other Soviet or Russian leader. Unlike Nikita Khrushchev, Leonid Brezhnev, Konstantin Chernenko, and Yuri Andropov—not to mention Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin—Putin has unquestioned power that is not shared or limited in any way by parliament, courts, or a Politburo. State propaganda has created a Stalin-like personality cult that lionizes Putin’s absolute power, genius as a leader, and role as a brilliant wartime generalissimo. It projects him as the fearsome and all-powerful head of a militarized nation aiming, like Stalin, to defeat a “Nazi” regime in Ukraine and reassert hegemony over Eastern and Central Europe. Just as Stalin made effective use of the Russian Orthodox Church to support Russia’s effort during World War II, Putin has effectively used Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill as a critical ally and cheerleader of Russia’s brutal war in Ukraine. And just like Stalin, Putin has made invading neighboring countries and annexing territory a central focus of the Kremlin’s foreign policy.

Putin’s descent into tyranny has been accompanied by his gradual isolation from the rest of society. Like the latter-day Stalin, Putin began living an isolated life as a bachelor even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Like the later Stalin, Putin lacks a stable family life and is believed to have replaced it with a string of mistresses, some of whom are reported to have borne him children for whom he remains a remote figure. Like Stalin, he stays up late into the early-morning hours, and like the Soviet dictator, Putin has assembled around him a small coterie of trusted intimates, mostly men in their 60s and 70s, with whom he has maintained friendships for decades, including businessmen Yury Kovalchuk and Igor Sechin, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, and security chief Nikolai Patrushev. This coterie resembles Stalin’s small network of cronies: security chief Lavrentiy Beria, military leader Kliment Voroshilov, and Communist Party official Georgy Malenkov. To others in leadership positions, Putin is a distant, absolute leader who openly humiliates seemingly powerful officials, such as spy chief Sergey Naryshkin, when the latter seemed to hesitate in his support during Putin’s declaration of war on Ukraine.

Through near-total control of domestic civic life and media, his widening campaign of repression and terror, relentless state propaganda promoting his personality cult, and his vast geopolitical ambitions, Putin is consciously mimicking the Stalin playbook, especially the parts of that playbook dealing with World War II. Even if Putin has no love for Soviet Communist ideology, he has transformed Russia and its people in ways that are no less fundamental than Stalin’s efforts to shape a new Soviet man.

Putin’s massive victory in a Soviet-style election last weekend represents the ratification by the Russian people of his brutal war, militarization of Russian society, and establishment of a totalitarian dictatorship. It is a good moment to acknowledge that Russia’s descent into tyranny, mobilization of society onto a war footing, spread of hatred for the West, and indoctrination of the population in imperialist tropes represent far more than a threat to Ukraine. Russia’s transformation into a neo-Stalinist, neo-imperialist power represents a rising threat to the United States, its European allies, and other states on Russia’s periphery. By recognizing how deeply Russia has changed and how significantly Putin is borrowing from Stalin’s playbook, we can better understand that meeting the modern-day Russian threat will require as much consistency and as deep a commitment as when the West faced down Stalin’s Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to identify a braindead take without dissecting it and engaging directly with it: see that it starts with "(x group of people) always..." then dismiss it. But since we're doing skepticism for fun, let's dissect anyway.

Atheism is a label based on someone's position on one very specific subject. Atheists don't believe gods exist. Within that label there are all kinds of subcategories that a person might fall into, but if all you know is that someone is an atheist, then all you know is that they don't believe in god.

I'd like to know how this person thinks they can extrapolate based on that one piece of information what sort of cognitive processes that person (or an entire group of people, in this case) uses to arrive at any given conclusion.

Logic is not math, so I don't understand the parenthetical addition there. Math relies on the laws of logic, but the two can't be considered the same. And I've seen plenty of atheists utterly fail at applying logic in many spectacularly stupid ways, just as I see with many believers. Nor do I, being a skeptic first and an atheist second, think that logic is necessarily the only path to truth. But it is a damn good one and if applied correctly I don't see how it could ever fail you, unlike faith, which has no explanatory power at all. If you think you can defeat the laws of logic I'm excited to see you win your Nobel prize!

Any physicists reading? I'd like to understand what this person means by "the interrelationship between pure energy and our material world." My very basic layman's understanding of energy is that it is the measurement of the potential to do work. And although immaterial itself, its effects on or within the material are pretty clearly understood through logical processes that guide mathematics and the scientific method. I'm not sure what disadvantage I've got by not appealing to some ethereal, intangible plane to imply some deeper meaning. Please help me see where I'm wrong there!

And lastly, I'm not really all that prideful, nor do I even come close to thinking I've "gotten it all figured out" by any stretch of the imagination. What I love about my epistemology now, as opposed to when I used to accept beliefs without sufficient evidence, is that discovering I'm wrong about something is EXCITING! I learn new information and my worldview changes as a result, rather than stagnating in the rigidity of thought-stopping ideologies that put all of the inner workings of the universe in the hands of a magical, unseen wizard.

#skepticism#religion#faith#atheism#belief#logic#physics#energy#epistemology#ex christian#physicists#physicists please reply

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr Michael Mosley

Popular celebrity medic who offered health advice to millions through his TV and radio roles, most notably on fasting

Dr Michael Mosley, who has died aged 67 on the Greek island of Symi, explored health and fitness issues of interest to big audiences. He was a versatile communicator, whether as a television diet guru, newspaper columnist or podcaster.

He became a household name for diet books promoting calorie reduction and fasting, including The Fast Diet (2013), written with the journalist Mimi Spencer. His work gained in popularity from his self-experimentation, which included swallowing tapeworms, magic mushrooms, internal cameras and – most famously – fasting to cure his own type 2 diabetes, diagnosed in 2012. He became a well known TV and radio celebrity medic, regularly appearing on The One Show for the BBC and This Morning for ITV. On BBC Radio 4’s Just One Thing podcast he offered health tips to the nation, from the benefits of daily spoonfuls of olive oil to the usefulness of the plank position.

Yet his own medical career was brief. Mosley, who studied philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) at New College, Oxford, trained in medicine at the Royal Free hospital, north London, after two years of working as a banker. He wanted to become a psychiatrist, saying that he found people more interesting than finance, but was disappointed to find that “there were severe limitations to what you could do”, he told the British Medical Journal in 2004.

He opted instead to exert influence through the medium of television, joining the BBC training scheme as an assistant producer in 1985, and going on to produce documentaries based mostly in science, mathematics and history.

His most glorious moment arguably came with the Horizon programme Ulcer Wars, which he made in 1994 about the work of Barry Marshall of the University of Western Australia, who was convinced that the bacteria he had identified called Helicobacter pylori was responsible for most gastric cancers and ulcers.

The story appealed to Mosley and inspired his own self-experimentation: Marshall had drunk a solution of H pylori from a beaker in the 1980s and his stomach had been colonised by the bacteria, which disappeared when he took antibiotics.

Marshall was right and later, with his colleague Robin Warren, won a Nobel prize. Mosley received more than 20,000 letters from people cured of their ulcer pain by antibiotics. The film brought him awards. “I probably did, in a funny way, more good with that one programme than if I had stayed in medicine for 30 years,” said Mosley in the BMJ.

In 2002, Mosley was nominated for an Emmy as executive producer on the documentary featuring John Cleese, The Human Face. In 2013, he began to host the series Trust Me, I’m a Doctor for the BBC. His most recent TV series were for Channel 4: Who Made Britain Fat? (2022) and Secrets of Your Big Shop (2024).

The Fast Diet book, which launched the 5:2 diet, also came out of a Horizon documentary. Eat, Fast and Live Longer (2012) was inspired by Mosley’s own diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, which is linked to excess weight. The disease ran in the family. His father, Bill, had died of the complications at the age of 74. Mosley came across the American neuroscientist Mark Mattson’s work on intermittent fasting, and adopted the pattern he advocated of normal eating for five days and consumption of just 500-600 calories on the other two.

He claimed to have lost 20lbs and reversed his own type 2 diabetes. Mattson appeared in the documentary, which is credited with popularising the 5:2 diet. In 2021, Mosley published The Fast 800 Keto, which combines fasting with a ketogenic diet, high in fat and low in carbohydrates, but in its later stages allows carbohydrates back in.

Mosley’s diet work was controversial because of its focus on calorie reduction to lose weight. In 2021, the eating disorder charity Beat said of his Channel 4 series Lose a Stone in 21 Days that “the programme caused enough stress and anxiety to our beneficiaries that we extended our helpline hours to support anyone affected and received 51% more contact during that time”.

He said he had suffered from chronic insomnia from his late 30s. That became the subject of another BBC documentary and also a book published in 2019, called Fast Asleep.

Born in Calcutta (Kolkata), India, Michael was the son of a banker, Bill Mosley, and his wife, Joan. At the age of seven he was sent to boarding school in Britain. Mosley said in an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald that his mother was heartbroken to send him away to school, but that his father worked in Hong Kong and the Philippines, wanted Michael and his other son, John, to become bankers as he had, and that sending children to boarding school back in Britain was part of the culture of that time.

His maternal grandfather was an Anglican bishop. Mosley said he came from a long line of missionaries, but “the closest I get to religion is incorporating fasting in my diet”.

Mosley met Clare Bailey at the Royal Free hospital medical school, now part of UCL medical school, and they married in 1987. Bailey, who became a GP, was an active partner in Mosley’s dietary work and wrote recipe books for people embarking on the Fast 800 diet as well as newspaper columns in her own right. She told interviewers that she did not fast, because she had never needed to lose weight, and that she would hide chocolate from Mosley, who had a sweet tooth.

She survives him, along with their three sons, Alex, Jack and Daniel, and a daughter, Kate.

🔔 Michael Mosley, doctor, writer and broadcaster, born 22 March 1957; found dead 9 June 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

15 notes

·

View notes