#sogyal rinpoche

Text

Devote the mind to confusion and we know only too well, if we’re honest, that it will become a dark master of confusion, adept in its addictions, subtle and perversely supple in its slaveries. Devote it in meditation to the task of freeing itself from illusion, and we will find that, with time, patience, discipline, and the right training, our mind will begin to unknot itself and know its essential bliss and clarity.

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

Sogyal Rinpoche

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

A veces pienso que el mayor logro de la cultura moderna es su brillante manera de vender las bondades del samsara y sus distracciones estériles. La sociedad moderna me parece una celebración de todas aquellas cosas que nos alejan de la verdad, que hacen difícil vivir para la verdad y que inducen a la gente a dudar incluso de su existencia. Y pensar que todo esto surge de una civilización que dice adorar la vida, pero que en realidad la priva de todo sentido real; que habla sin cesar de «hacer feliz» a la gente, pero que de hecho le cierra el paso a la fuente de la auténtica alegría.

El libro tibetano de la vida y de la muerte – Sogyal Rinpoche.

#Sogyal Rinpoche#El libro tibetano de la vida y de la muerte#citas#notas#escritos#frases#textos#libros#espiritualidad#espiritual#paz espiritual#paz#amor#despertar espiritual

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Light must come from inside. You cannot ask the darkness to leave; you must turn on the light.

Sogyal Rinpoche

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There are different species of laziness: Eastern and Western. The Eastern style is like the one practiced in India. It consists of hanging out all day in the sun, doing nothing, avoiding any kind of work or useful activity, drinking cups of tea, listening to Hindi film music blaring on the radio, and gossiping with friends. Western laziness is quite different. It consists of cramming our lives with compulsive activity, so there is no time at all to confront the real issues. This form of laziness lies in our failure to choose worthwhile applications for our energy.”

—Sogyal Rinpoche

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist: Josef Kote

* * * *

“Here’s an experiment. Pick up a coin. Imagine that it represents the object at which you are grasping. Hold it tightly, clutching it in your fist and extend your arm, with the palm of your hand facing the ground. Now if you let go or relax your grip, you will lose what you are clinging onto. That’s why you hold onto it.

But there is another possibility: You can let go and yet keep hold of it. With your arm still outstretched, turn your hand over so that it faces the sky. Release your hand and the coin still rests on your open palm. You let go, and the coin is still yours with all the space around it. So there is a way in which we can accept impermanence and still relish life, at one and the same time, without grasping.”

- Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

[Jim Fagiolo]

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The red book

[…].Rather, he saw that each person’s consciousness emerges like an island from the great sea in which all find their base, with the rim of wet sand encircling each island corresponding to the “personal unconscious.” But it is the collective unconscious—that sea—that is the birthplace of all consciousness, and from there the old ideas arise anew, and their connections with contemporary situations are initiated.

[…]

At times during this period, Jung was so overcome with emotion that he feared that he might be in danger of losing his psychic balance altogether. Writing down the material helped him to keep it under control, since once it was objectified he could then turn his mind to other things, secure in the knowledge that the unconscious material was safe from loss or distortion. During this strained and difficult period of his life he never withdrew from his routine of active work and related[1]ness to his family. Life with his wife and children proved to be a stabilizing influence, as also was his psychiatric practice. He forced himself to move back and forth from the conscious position with its distinct, if temporal, demands—to the unconscious one. Gradually he attained a capacity for granting each position its important role in his life and, when it was necessary, to allow the interpenetration of the one by the other.

[…]. He had the courage to state that psychotherapy cannot be defined altogether as a science. In making a science of her, he said, “the individual imagines that he has caught the psyche and holds her in the hollow of his hand. He is even making a science of her in the absurd supposition that the intellect, which is but a part and a function of the psyche, is sufficient to comprehend the much greater whole.”

The word “science” comes from the Latin scientia, which means knowledge, and therefore is identified with consciousness and with the intellectual effort to draw into consciousness as much knowledge as possible. But, with our psychological concept of the unconscious, and with all the evidence that has emerged to justify its reality, it is necessary to recognize that there is a very large area of human experience with which science cannot deal. It has to do with all that is neither finite nor measurable, with all that is neither distinct nor—potentially, at least—explicable. It is that which is not accessible to logic or to the “word.” It begins at the outermost edge of knowledge. Despite the continuing expansion or even explosion of information, there will forever be limits beyond which the devices of science cannot lead a man.

It becomes a matter of seeing the “created world” in terms of a “creating principle.” This is difficult when we conceive of ourselves as being among “the created” and hence being unable to comprehend that which was before we existed and which will continue after the ego-consciousness with which we identify ourselves no longer exists in the form in which we know it. We cannot, however much we strive, incorporate all of the unconscious into consciousness, because the first is illimitable and the second, limited. What is the way then, if there is a way, to gain some understanding of unconscious processes? It seemed to Jung, as it has to others who have set aside the ego to participate directly in the mystery, that if we cannot assimilate the whole of the unconscious, then the risk of entering into the unfathomable sphere of the unconscious must be taken.

It is not that Jung deliberately sought to dissolve the more or less permeable barrier between consciousness and the unconscious. It was, in effect, something that happened to him— sometimes in dreams, and sometimes in even more curious ways. Under the aegis of Philemon as guiding spirit, Jung submitted himself to the experience that was happening to him. He accepted the engagement as full participant; his ego remained to one side in a non-interfering role, a helper to the extent that observation and objectivity were required to record the phenomena that occurred. And what did occur shocked Jung profoundly. He realized that what he felt and saw resembled the hallucinations of his psychotic patients, with the difference only that he was able to move into that macabre half world at will and again out of it when external necessity demanded that he do so. This required a strong ego, and an equally strong determination to step away from it in the direction of that superordinate focus of the total personality, the self.

However, we must remember that it was with no such clearly formulated goal that Jung in those days took up the challenge of the mysterious. This was uncharted territory. He was experiencing and working out his fantasies as they came to him. Alternately, he was living a normal family life and carrying on his therapeutic work with patients, which gave him a sense of active productivity.

Meanwhile, the shape of his inner experience was becoming more definite, more demanding. One day he found himself besieged from within by a great restlessness. He felt that the entire atmosphere around him was highly charged, as one sometimes senses it before an electrical storm. The tension in the air seemed even to affect the other members of the house[1]hold; his children said and did odd things, which were most uncharacteristic of them. He himself was in a strange state, a mood of apprehension, as though he moved through the midst of a houseful of spirits. He had the sense of being surrounded by the clamor of voices—from without, from within—and there was no surcease for him until he took up his pen and began to write.

Then, during the course of three nights, there flowed out of him a mystifying and heretical document. It began: “The dead came back from Jerusalem, where they found not what they sought.” Written in an archaic and stilted style, the manuscript was signed with the pseudonym of Basilides, a famous gnostic teacher of the second century after Christ. Basilides had belonged to that group of early Christians which was declared heretical by the Church because of its pretensions to mystic and esoteric insights and its emphasis on direct knowledge rather than faith. It was as though the orthodox Christian doctrine had been examined and found too perfect, and therefore incomplete, since the answers were given in that doctrine, but many of the questions were missing. Jung raised crucial questions in his Seven Sermons of the Dead. The blackness of the nether sky was dredged up and the paradoxes of faith and disbelief were laid side by side. Traces of the dark matter of the Sermons may be found throughout the works of Jung which followed, especially those which deal with religion and its infernal counterpoint, alchemy. All through these later writings it is as if Jung were struggling with the issues raised in the dialogues with the “Dead,” who are the spokesmen for that dark realm beyond human understanding; but it is in Jung’s last great work, Mysterium Coniunctionis, on which he worked for ten years and completed only in his eightieth year, that the meaning of the Sermons finally finds its definition. Jung said that the voices of the Dead were the voices of the Unanswered, Unresolved and Unredeemed. Their true names became known to Jung only at the end of his life.

The words flow between the Dead, who are the questioners, and the archetypal wisdom which has its expression in the individual, who regards it as revelation. The Sermons deny that God spoke two thousand years ago and has been silent ever since, as is commonly supposed by many who call themselves religious. Paul, whose letters are sometimes referred to as “gnostic,” supported this view in his Epistle to the Hebrews (1:1), “God who at sundry times and in divers manner spake in time past unto the fathers by thy prophets, hath in these last days spoken unto us by his Son .. .” Revelation occurs in every generation. When Jung spoke of a new way of understanding the hidden truths of the unconscious, his words were shaped by the same archetypes that in the past inspired the prophets and are operative in the present in the unconscious of modern man. Perhaps this is why he was able to say of the Sermons: “These conversations with the dead formed a kind of prelude to what I had to communicate to the world about the unconscious: a kind of pattern of order and interpretation of all its general contents.”

I will not attempt here to interpret or explain the Sermons. They must stand as they are, and whoever can find meaning in them is free to do so; whoever cannot may pass over them. They belong to Jung’s “initial experiences” from which derived all of his work, all of his creative activity. A few excerpts will offer some feeling for the “otherness” which Jung experienced at that time, and which was for him so germinal. The first Sermon, as he carefully lettered it in antique script in his Red Book, begins:

The dead came back from Jerusalem where they found not what they sought. They prayed me let them in and besought my word, and thus I began my teaching.

Hearken: I begin with nothingness. Nothingness is the same as fullness. In infinity full is no better than empty. Nothingness is both empty and full. As well might ye say anything else of nothingness, as for instance, white it is, or black, or again, it is, not, or it is. A thing that is infinite and eternal hath no qualities, since it hath all qualities.

This nothingness or fullness we name the pleroma.

All that I can say of the pleroma is that it goes beyond our capacity to conceive of it, for it is of another order than human consciousness. It is that infinite which can never be grasped, not even in imagination. But since we, as people, are not infinite, we are distinguished from the pleroma. The first Sermon continues:

Creatura is not in the pleroma, but in itself. The pleroma is, both beginning and end of created beings. It pervadeth them, as the light of the sun everywhere pervadeth the air. Although the pleroma pervadeth altogether, yet hath created body no share thereof, just as a wholly transparent body becometh neither light nor dark through the light which pervadeth it. We are, however, the pleroma itself, for we are a part of the eternal and the infinite. But we have no share thereof, as we are from the pleroma infinitely removed; not spiritually or temporally, but essentially, since we are distinguished from the pleroma in our essence as creatura, which is confined within time and space.

The quality of human life, according to this teaching, lies in the degree to which each person distinguishes herself or himself from the totality of the unconscious. The wresting of consciousness, of self-awareness, from the tendency to become submerged in the mass, is one of the most important tasks of the individuated person. This is the implication of a later passage from the Sermons:

What is the harm, ye ask, in not distinguishing oneself?

If we do not distinguish, we get beyond our own nature, away from creatura. We fall into indistinctiveness . . . We fall into the pleroma itself and cease to be creatures. We are given over to dissolution in the nothingness. This is the death of the creature. Therefore we die in such measure as we do not dis[1]tinguish. Hence the natural striving of the creature goeth to[1]wards distinctiveness, fighteth against primeval, perilous sameness. This is called the principium individuationis. This principle is the essence of the creature.

In the pleroma all opposites are said to be balanced and therefore they cancel each other out; there is no tension in the unconscious. Only in man’s consciousness do these separations exist:

The Effective and the Ineffective.

Fullness and Emptiness.

Living and Dead.

Difference and Sameness.

Light and Darkness.

The Hot and the Cold.

Force and Matter.

Time and Space.

Good and Evil.

Beauty and Ugliness.

The One and the Many...

These qualities are distinct and separate in us one from the other; therefore they are not balanced and void, but are effective. Thus are we the victims of the pairs of opposites. The pleroma is rent in us.

Dualism and monism are both products of consciousness. When consciousness begins to differentiate from the unconscious, its first step is to divide into dichotomies. It proceeds through all possible pairs until it arrives at the concept of the One and the Many. This implies a recognition that even the discriminating function of consciousness acknowledges that all opposites are contained within a whole, and that this whole contains both consciousness and that which is not conscious. Here lies the germ of the concept marking the necessity of ever looking to the unconscious for that compensating factor which can enable us to bring balance into the one-sided attitude of consciousness. Always, in the analytic process, we search the dreams, the fantasies, and the products of active imagination, for the elements that will balance: the shadow for persona-masked ego, the anima for the aggressively competitive man, the animus for the self-effacing woman, the old wise man for the puer aeternus, the deeply founded earthmother for the impulsive young woman. We need to recognize the importance of not confusing ourselves with our qualities. I am not good or bad, wise or foolish—I am my “own being” and, being a whole person, I am capable of all manner of actions, good and bad wise and foolish. The traditional Christian ideal of attempting to live out only the so-called higher values and eschewing the lower is proclaimed disastrous in this gnostic “heresy.” The traditional Christian ideal is antithetical to the very nature of consciousness or awareness:

When we strive after the good or the beautiful, we thereby forget our own nature, which is distinctiveness, and we are delivered over to the qualities of the; pleroma, which are pairs of opposites. We labour to attain to the good and the beautiful, yet at the same time we also lay hold of the evil and the ugly, since in the pleroma these are one with the good and the beautiful. When, however, we remain true to our own nature, which is distinctiveness, we distinguish ourselves from the good and the beautiful, and therefore, at the same time, from the evil and ugly. And thus we fall not into the pleroma, namely, into nothingness and dissolution.

Buried in these abstruse expressions is the very crux of Jung’s approach to religion. He is deeply religious in the sense of pursuing his life task under the overwhelming awareness of the magnitude of an infinite God, yet he knows and accepts his limitations as a human being. This makes him reluctant to say with certainty anything about this “Numinosum,” this totally “Other.” In a filmed interview Jung was asked, “Do you believe in God?” He replied with an enigmatic smile, “I know. I don't need to believe. I know.” Wherever the film has been shown an urgent debate inevitably follows as to what he meant by that statement. It seems to me that believing means to have a firm conviction about something that may or may not be debatable. It is an act of faith, that is, it requires some effort. Perhaps there is even the implication that faith is required because that which is believed in seems so preposterous. On the other hand, it is not necessary to acquire a conviction about something if you have experienced it. I do not believe I have just eaten dinner. If I have had the experience, I know it. And so with recognizing the difference between religious belief and religious experience. Whoever has experienced the divine presence has passed beyond the requirement of faith, and also of reason. Reasoning is a process of approximating truth. It leads to knowledge. But knowing is a direct recognition of truth, and it leads to wisdom. Thinking is a process of differentiation and discrimination. In our thoughts we make separations and enlist categories where in a wider view of reality they do not exist. The rainbow spectrum is not composed of six or seven colors; it is our thinking that determines how many colors there are and where red leaves off and orange begins. We need to make our differentiations in the finite world in order to deal expediently with the fragmented aspects of our temporal lives.

The Sermons remind us that our temporal lives, seen from the standpoint of eternity, may be illusory—as illusory as eternity seems when you are trying to catch a bus on a Monday morning. Either seems false when seen from the standpoint of the other. Addressed to the Dead, the words that follow are part of the dialogue with the unconscious, the pleroma, whose existence is not dependent on thinking or believing.

Ye must not forget that the pleroma hath no qualities. We create them through thinking. If, therefore, ye strive after difference or sameness, or any qualities whatsoever, ye pursue thoughts which flow to you out of the pleroma; thoughts, namely, concerning non-existing qualities of the pleroma. In as much as ye run after these thoughts, ye fall again into the pleroma, and reach difference and sameness at the same time. Not your thinking, but your being, is distinctiveness. Therefore, not after difference, as ye think it, must ye strive; but after your own being. At bottom, therefore, there is only one striving, namely, the striving after your own being. If ye had this striving ye would not need to know anything about the pleroma and its qualities, and yet would come to your right goal by virtue of your own being.

The passage propounds Jung’s insight about the fruitlessness of pursuing philosophizing and theorizing for its own sake. Perhaps it suggests why he never systematized his own theory of psychotherapy, why he never prescribed techniques or methods to be followed. Nor did he stress the categorization of patients into disease entities based on differences or samenesses, except perhaps as a convenience for purposes of describing appearances, or for communicating with other therapists. The distinctiveness of individual men or women is not in what has happened to them, in this view, nor is it in what has been thought about them. It is in their own being, their essence. This is why a man or woman as therapist has only one “tool” with which to work, and that is the person of the therapist. What happens in therapy depends not so much upon what the therapist does, as upon who the therapist is.

The last sentence of the first Sermon provides the key to that hidden chamber which is at once the goal of individuation, and the abiding place of the religious spirit which can guide us from within our own depths:

Since, however, thought estrangeth from being, that knowledge must I teach you wherewith ye may be able to hold your thought in leash.

Suddenly we know who the Dead are. We are the dead. We are psychologically dead if we live only in the world of consciousness, of science, of thought which “estrangeth from being.” Being is being alive to the potency of the creative principle, translucent to the lightness and the darkness of the pleroma, porous to the flux of the collective unconscious. The message does not decry “thought,” only a certain kind of thought, that which “estrangeth from being.” Thought—logical deductive reasoning, objective scientific discrimination— must not be permitted to become the only vehicle through which we may approach the problematic of nature. Science, and most of all the “science of human behavior,” must not be allowed to get away with saying “attitudes are not important, what is important is only the way in which we behave.” For if our behavior is to be enucleated from our attitudes we must be hopelessly split in two, and the psyche, which is largely spirit, must surely die within us.

That knowledge . . . wherewith ye may be able to hold your thought in leash must, I believe, refer to knowledge which comes from those functions other than thinking. It consists of the knowledge that comes from sensation, from intuition, and from feeling. The knowledge which comes from sensation is the immediate and direct perception which arrives via the senses and has its reality independently of anything that we may think about it. The knowledge which comes from intuition is that which precedes thinking and also which suggests where thinking may go; it is the star which determines the adjustment of the telescope, the hunch which leads to the hypothesis. And finally, the knowledge which comes from feeling is the indisputable evaluative judgment; the thing happens to me in a certain way and incorporates my response to it; I may be drawn toward it or I may recoil from it, I love or I hate, I laugh or I weep, all irrespective of any intervening process of thinking about it.

It is not enough, as some of the currently popular anti-intellectual approaches to psychotherapy would have it, merely to lay aside the intellectual function. The commonly heard cries, “I don’t care what you think about it, I want to know how you feel about it,” are shallow and pointless; they miss the kernel while clinging to the husk. Jo hold your thought in leash, that seems to me the key, for all the knowledge so hard-won in the laboratory and in the field is valuable only in proportion to the way it is directed to the service of consciousness as it addresses itself to the unconscious, to the service of the created as it addresses itself to the creative principle, to the service of human needs as we address ourselves to God.

Jung’s approach to religion is twofold, yet it is not dualistic. First, there is the approach of one person to God and, second, there is the approach of the scientist-psychologist to people’s idea-of-God. The latter is subsumed under the for[1]mer. Jung’s own religious nature pervades all of his writing about religion; even when he writes as a psychotherapist he does not forget that he is a limited human being standing in the shade of the mystery he can never understand.

Nor is he alone in this. Margaret Mead has written, “We need a religious system with science at its very core, in which the traditional opposition between science and religion . . . can again be resolved, but in terms of the future instead of the past ... Such a synthesis . . . would use the recognition that when man permitted himself to become alienated from part of himself, elevating rationality and often narrow purpose above those ancient intuitive properties of the mind that bind him to his biological past, he was in effect cutting himself off from the rest of the natural world.”

[…]

What Jung is attempting to understand and elucidate is, as the student quite correctly supposed, a psychology of religion. Jung puts the religious experience of the individual, which comes about often spontaneously and independently, into place with the religious systems that have been evolved and institutionalized in nearly every society throughout history.

In psychotherapy, the religious dimension of human experience often appears after the analytic process has proceeded to some depth. Initially, people come for help with some more or less specific problem. They may admit to a vague uneasiness that what is ailing may be a matter of personal issues, and that the “symptoms” or “problems” they face could be outcroppings of a deeper reality—the shape of which they do not comprehend. When, in analysis, they come face to face with the figurative representation of the self, they are often stunned and shocked by the recognition that the non-personal power, of which they have only the fuzziest conception, lives and manifests itself in them. Oh, yes, they have heard about this, and read about it, and have heard it preached from intricately carved pulpits, but now it is all different. It is the image in their own dreams, the voice in their own ears, the shivering in the night as the terror of all terrors bears down upon them, and the knowing that it is within them—arising there, finding its voice there, and being received there.

It is not in the least astonishing, [Jung tells us] that numinous experiences should occur in the course of psychological treatment, and that they. may even be expected with some regularity, for they also occur very frequently in exceptional psychic states that are not treated, and may even cause them. They do not belong exclusively to the domain of psychopathology but can be observed in normal people as well. Naturally, modern ignorance of and prejudice against intimate psychic experiences dismiss them as psychic anomalies and put them in psychiatric pigeonholes without making the least attempt to understand them. But that neither gets rid of the fact of the occurrence nor explains it.

[…]

Nor is there any more hope that the God-concept advanced by the various religions is any more demonstrable than that expressed by the individual as “my own idea.” The various expressions that have been given voice about the nature of transcendental reality are so many and diverse that there is no way of knowing absolutely who is right, even if there were a single, simple answer to the question. Therefore, as Jung saw it, the denominational religions long ago recognized that there was no way to defend the exclusivity of their “truth” so, instead, they took the offensive position and pro[1]claimed that their religion was the only true one, and the basis for this, they claimed, was that the truth had been directly revealed by God. “Every theologian speaks simply of ‘God,’ by which he intends it to be understood that his ‘god’ is the God. But one speaks of the paradoxical God of the Old Testament, another of the incarnate God of Love, a third of the God who has a heavenly bride, and so on, and each criticizes the other but never himself.”

[…]

A basic principle of Jung’s approach to religion is that the spiritual element is an organic part of the psyche. It is the source of the search for meaning, and it is that element which lifts us above our concern for merely keeping our species alive by feeding our hunger and protecting ourselves from attack and copulating to preserve the race. We could live well enough on the basis of the instincts alone; the naked ape does not need books or churches. The spiritual element which urges us on the quest for the unknown and the unknowable is the organic part of the psyche, and it is this which is responsible for both science and religion. The spiritual element is expressed in symbols, for symbols are the language of the unconscious. Through consideration of the symbol, much that is problematic or only vaguely understood can become real and vitally effective in our lives.

The symbol attracts, and therefore leads individuals on the way of becoming what they are capable of becoming. That goal is wholeness, which is integration of the parts of the personality into a functioning totality. Here consciousness and the unconscious are united around the symbols of the self. The ways in which the self manifests are numerous beyond any attempt to name or describe them. I choose the mandala symbol as a starting point because its circular characteristics suggest the qualities of the self (the pleroma that hath no qualities). It is “smaller than small and bigger than big.” In principle, the circle must have a center, but that point which we mark as a center is, of necessity, larger than the true center. However much we decrease the central point, the true center is at the center of that, and hence, smaller yet. The circumference is that line around the center which is at all points equidistant from it. But, since we do not know the length of the radius, it may be said of any circle we may imagine, that our mandala is larger than that. The mandala, then, as a symbol of the self, has the qualities of the circle, center and circumference, yet like the self of which it is an image, it has not these qualities.

Is it any wonder then, that the man who was not a man should be chosen as a symbol of the self and worshiped throughout the Christian world? Is it at all strange, when considered symbolically, that the belief arose that an infinite spirit which pervades the universe should have concentrated the omnipotence of his being into a speck so infinitesimal that it could enter the womb of a woman and be born as a divine child?

In his major writings on “Christ as a Symbol of the Self” Jung has stated it explicitly:

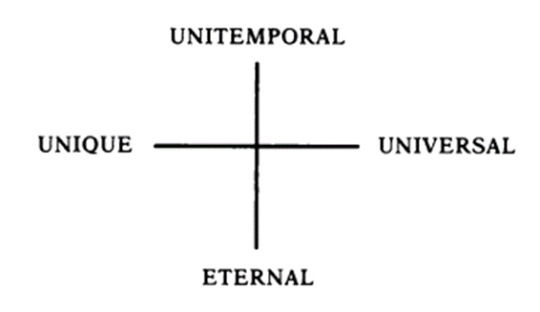

In the world of Christian ideas Christ undoubtedly represents the self. As the apotheosis of individuality, the self has the attributes of uniqueness and of occurring once only in time. But since the psychological self is a transcendent concept, expressing the totality of conscious and unconscious contents, it can only be described in antinomial terms; that is, the above attributes must be supplemented by their opposites if the transcendental situation is to be characterized correctly. We can do this most simply in the form of a quaternion of opposites:

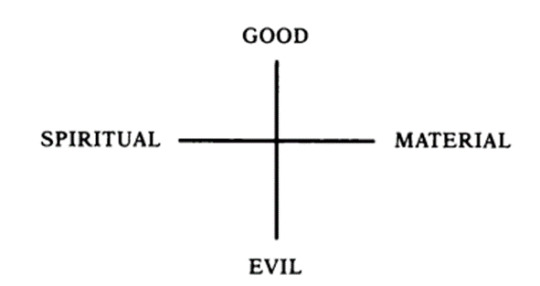

This formula expresses not only the psychological self but also the dogmatic figure of Christ. As an historical personage Christ is unitemporal and unique; as God, universal and eternal... . Now if theology describes Christ as simply “good” and “spiritual,” something “evil” and “material” . . . is bound to arise on the other side . . . The resultant quaternion of opposites is united on the psychological plane by the fact that the self is not deemed exclusively “good” and “spiritual”; consequently its shadow turns out to be much less black. A further result is that the opposites of “good” and “spiritual” need no longer be separated from the whole:

[…]

The pre-form of this insight appeared in the first of the Seven Sermons of the Dead where it is said, “the striving of the creature goeth toward distinctiveness, fighteth against prime[1]val, perilous sameness. This is called the principium individua[1]tionis.”” We are caught in the struggle between the opposites; the stone is fixed and incorruptible. The individuation process is an opus contra naturam,; it is a struggle against the natural, haphazard way of living in which we simply respond first to the demands made upon us by the circumstances of our envi[1]ronment and then to those of inner necessity, paying the most attention to the side that is most insistent at any given time. Individuation leads through the confrontation of the opposites until a gradual integration of the personality comes about, a oneness with oneself, with one’s world, and with the divine presence as it makes itself known to us.

The beginning of the alchemical process parallels the leg[1]ends of creation, the consolidation of a world out of formless chaos. In alchemy the opus starts out with a massa confusa, a teeming, disordered conglomeration of what is called prima materia. It goes through a series of transformations, all described in the most abstruse language, in a lore that predated Christianity and extended forward into the seventeenth century. We seldom get much of an idea of how the work was actually done, what materials were used and what results were achieved. Jung says, “The alchemist is quite aware that he writes obscurely. He admits that he veils his meaning on purpose, but nowhere,—so far as I know—does he say that he cannot write in any other way. He makes a virtue of necessity by maintaining either that mystification is forced on him for one reason or another, or that he really wants to make the truth as plain as possible, but that he cannot proclaim aloud just what the prima materia or the lapis is.” This is in a tradition of refusing to make easily available material that has been acquired only with great difficulty, on the grounds that the quest is at least as important as the goal, or that the importance of the goal rests on the energy and commitment that has been involved in the quest.

Jung cites one of the oldest alchemical tests, written in Arabic style: “This stone is below thee, as to obedience; above thee, as to dominion; therefore from thee, as to knowledge; about thee, as to equals.” He comments on the passage:

[It] is somewhat obscure. Nevertheless, it can be elicited that the stone stands in an undoubted psychic relationship to man: the adept can expect obedience from it, but on the other hand the stone exercises dominion over him. Since the stone is a matter of “knowledge” or “science,” it springs from man. But it is outside him, in his surroundings, among his “equals,” i.e., those of like mind. This description fits the paradoxical situation of the self, as its symbolism shows. It is the smallest of the small, easily overlooked and pushed aside. Indeed, it is in need of help and must be perceived, protected, and as it were built up by the conscious mind, just as if it did not exist at all and were called into being only through man’s care and devotion. As against this, we know from experience that it had long been there and is older than the ego, and that it is actually the spiritus rector (guiding, or controlling spirit) of our fate.

[…]

Ever since Alan Watts exchanged his starched clerical collar for a Japanese silk kimono and found wisdom in insecurity —if not for life everlasting, then long enough to influence a younger generation—Americans have been turned on to the mysterious East. A rediscovery of ancient truth has led many of these people into fads and fantasies inspired by the pilgrims from the Orient, and a smaller number to the serious study of Hinduism, Taoism and Zen Buddhism. In their reading, they often discover that Jung had taken a similar path many years before, and had learned a great deal about Eastern religions and philosophy both through study and through his travels in India. If they have read his essays on Eastern religion in Psychology and Religion they have some feeling for the great respect Jung held for much of the sacred teaching of the Orient. Also, they will have some understanding of his views on the potential effects of certain traditional Eastern ways of thinking upon the Western mind. All too frequently, however, Jung’s writings have been misunderstood or only partially understood. His interest in Eastern religious thought and certain practices associated with it—like his interest in séances, in alchemy, or in astrology—have been incorrectly construed as a wholehearted and literal endorsement for use by Westerners today.

During the period of greatest fascination with psychedelic drugs among college students and college drop-outs in the late 1960s, Tibetan mysticism was seized upon as a model or ideal to be sought within the psychedelic experience. Cecelia, whose case was discussed in Chapter 2, was one of these. The Tibetan Book of the Dead had been available to the English-speaking reader since it was compiled and edited by W. Y. Evans-Wentz in 1927. It only became a best-seller on campuses from Harvard to Berkeley when Leary, Metzner and Alpert publicized it in their efforts to provide instant illumination for American youth through LSD. Their book, The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, contains in its introductory section, “A Tribute to Carl G. Jung.” Jung is presented, quite correctly, as one who understood that the unconscious could, and in extraordinary states did, manifest itself in hallucinations such as have been called “The Magic Theatre,” and “The Retinal Circus,” where energy is transformed into strangely frightening bodily sensations, “wrathful visions” of monsters and demons, visions of the earth-mother, boundless waters, or fertile earth, broad-breasted hills, visions of great beauty in which nature flowers with an intense brilliance that is not known to ordinary consciousness. Messrs. Leary et al. suggest that The Tibetan Book of the Dead—in which these images are described in exquisite detail so that the living may recite the text (or oral tradition) to the dying or newly dead person in order to guide him on his path into the realm of Spirit—is not a book of the dead after all. It is, they assert, “a book of the dying; which is to say a book of the living; it is a book of life and how to live. The concept of actual physical death was an exoteric facade adopted to fit the prejudices’ of the Bonist tradition in Tibet . . . the manual is a detailed account of how to lose the ego; how to break out of personality into new realms of consciousness; and how to avoid the involuntary limiting processes of the ego…” In this sense, they identify “personality” with the conscious ego state, a state which in their view must be put aside in order to break into new realms of consciousness. They suggest that Jung did not appreciate the necessity for this leap into the unknown, since, in their words, “He had nothing in his conceptual framework which could make practical sense out of the ego-loss experience.”

But here these purveyors of imitation psychosis by the microgram (which occasionally, unfortunately, turns into the real thing) are the ones who miss the point, who misread Jung completely. Jung did know what it was like to come to the edge of ego-loss experience. His commitment had long been to the inner vision, but however close he came to total immersion in it, he felt that it was important, for Westerners at least, to maintain some contact with the ego position. To lose this entirely, it seemed to Jung, would be unconsciousness, madness or death. For him it was impossible to conceive of that state, described in The Tibetan Book of the Dead as the attainment of the Clear Light of the Highest Wisdom, in which one is merged with the supreme spiritual power, without the paradoxical conclusion that there is something left outside to experience the “conceiving.” That something is ego-consciousness, which of course is not present in an unconscious state, in psychosis or after death, because ego-consciousness is by definition a term which describes our awareness of our nature and identity vis-a-vis that which “we” are not.

Jung explains his own difficulty, which is perhaps the difficulty of the Westerner, to realize what the Tibetan Buddhist calls One Mind. The realization of the One Mind (according to Jung’s reading of The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation) creates “at-one-ment” or complete union, psychologically, with the non-ego. In doing so, One Mind becomes for Jung an analogue of the collective unconscious or, more properly, it is the same as the collective unconscious. Jung writes:

The statement “Nor is one’s own mind separable from other minds,” is another way of expressing the fact of “all-contamination.” Since all distinctions vanish in the unconscious condition, it is only logical that the distinction between separate minds should disappear too . . . But we are unable to imagine how such a realization [“at-one-ment”] could ever be complete in any human individual. There must always be somebody or something left over to experience the realization, to say “I know at-one-ment, I know there is no distinction.” The very fact of the realization proves its inevitable incompleteness… . Even when I say “I know myself,” an infinitesimal ego—the knowing “I’—is still distinct from “myself.” In this as it were atomic ego, which is completely ignored by the essentially non-dualist standpoint of the East, there nevertheless lies hidden the whole unabolished pluralistic universe and its unconquered reality.

When Jung says of The Tibetan Book of the Dead “it is a book that will only open itself to spiritual understanding, and this is a capacity which no man is born with, but which he can only acquire through special training and experience,” his statement rests on an incomplete understanding of the spiritual teaching of the East, and most particularly of the deeper meaning and guidance in this profound book. During Jung’s lifetime there was little opportunity for Westerners to learn directly from leading exponents of Tibetan Buddhism, hidden away as they were in their mountain fastnesses. But today, many great spiritual teachers who were expelled from their native land have come to the West, and have helped to clarify their beliefs with respect to dualism and “at-one-ment.” As an example, I quote from Sogyal Rinpoche’s The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying:

There are many aspects of the mind, but two stand out. The first is ordinary mind, called by the Tibetans sem. One. master defines it: “That which possesses discriminating awareness, that which possesses a sense of duality—which grasps or recognizes something external;—that is mind. Fundamentally it is that which can associate with an ‘other’ —with any ‘something’ that is perceived as different from the perceiver.” Sem is the discursive, dualistic thinking mind, which can only function in relation to a projected and falsely perceived external reference point…

Then there is the very nature of mind, its innermost essence, which is absolutely and always untouched by change or death. At present it is hidden within our own mind, our sem, enveloped and obscured by the mental scurry of our thoughts and emotions. Just as clouds can be shifted by a strong gust of wind to reveal the shining sun and wide-open sky, so, under special circumstances, some inspiration may uncover for us glimpses of this nature of mind...

Do not make the mistake of imagining that the nature of mind is exclusive to our mind only. It is, in fact, the nature of everything. It can never be said too often that to realize the nature of mind is to realize the nature of all things.

We need to remember that Jung, for all his metaphysical speculations, was in the first place and the last essentially a psychotherapist, and his life was devoted to discovering the means through which he could help individuals to know their lives as rich in meaning in this world, namely, the world of consciousness. This world may be immeasurably deepened and enhanced as we have seen throughout our reading of Jung, by the data of the unconscious. Of utmost importance is it that the unconscious material flow into consciousness, and furthermore, that material from consciousness flow into the unconscious, adding new elements which dissolve, transform and renew what has been present all along. But the most important thing, from the Jungian point of view is that the ego may not fall into the unconscious and become completely submerged, overwhelmed. There must always be an “I” to observe what is occurring in the encounter with the “Not-I.”

This was why he favored the method of “active imagination” for his own patients, and why this method is widely used by analytical psychologists today. Admittedly, it is a slow process, this establishing of an ongoing dialogue with the unconscious, but we accept that. Confronting the unconscious for us is not an “event,” but rather a “condition” in which we live. It is serious business, it is play; it is art and it is science. We confront the unknown at every turn, except when we lose the sense of ourselves (ego) or the sense of the other (the unconscious).

In my work with analysands, questions often come up about the relationship of active imagination to the practices of yoga and Eastern meditation. Students and analysands come to recognize that the dialogue between the ego and the unconscious, through the agency of the transcendent function in all its symbolic expressions, bears a certain resemblance to the symbolism of Tantric yoga in India and Tibet, lamaism, and Taoistic yoga in China. Yet Jung, who had studied these traditions for over half a century, beginning when they were quite unknown in the West except to a few scholars, did not advocate the adoption of these methods as a whole in the West, nor even their adaptation to our occidental modes and culture. The reason for this, as I have come to believe through study of Jung’s writing, is that a psychotherapy based upon a psychology of the unconscious, a psychotherapy which is the “cure of souls” is, indeed, the “yoga” of the West.

Jung has pointed out that an uninterrupted tradition of four thousand years has created the necessary spiritual conditions for yoga in the East. There, he says, yoga is

the perfect and appropriate method of fusing body and mind together so that they form a unity . . . a psychological disposition . . . that transcends consciousness. The Indian mentality has no difficulty in operating intelligently with a concept like prana. The West, on the contrary, with its bad habit of wanting to believe on the one hand, and its highly developed scientific and philosophical critique on the other, finds itself in a real dilemma. Either it falls into the trap of faith and swallows concepts like prana, atman, chakra, samadhi, etc., without giving them a thought, or its scientific critique repudiates them one and all as “pure mysticism.” The split in the Western mind therefore makes it impossible at the outset for the intentions of yoga to be realized in any adequate way. It becomes either a strictly religious matter, or else a kind of training... and not a trace is to be found of the unity and wholeness of nature which is characteristic of yoga. The Indian can forget neither the body nor the mind, while the European is always forgetting either the one or the other...The Indian...not only knows his own nature, but he knows also how much he himself is nature. The European, on the other hand, has a science of nature and knows astonishingly little of his own nature, the nature within him. For the Indian, it comes as a blessing to know of a method which helps him to control the supreme power of nature within and without. For the European, it is sheer poison to suppress his nature, which is warped enough as it is, and to make out of it a willing robot...

He concludes his discussion with the warning:

Western man has no need of more superiority over nature, whether outside or inside. He has both in almost devilish perfection. What he lacks is conscious recognition of his inferiority to the nature around and within him. He must learn that he may not do exactly as he wills. If he does not learn this, his own nature will destroy him.

The reasonable question at this point would be, “How do we learn this?” Perhaps I can approach it by telling about a brilliant young psychotherapist. Hannah worked in a university setting, treating student-patients. She was also attending graduate school and expected to get her degree “some day,” but had never seemed in too much of a hurry about it. When Hannah came into analysis, she was immersed in some intense relationships with close men and women friends, in the Women’s Liberation movement, and more than one demanding campus activity. She was feeling increasingly fragmented, expending herself in every direction, attempting to bring her knowledge and will to bear, first on this problem, then on that. As she felt under more and more pressure, she became increasingly assiduous about seeking out various new ways of dealing with the situations and conflicts that arose in her per[1]sonal life and her work.

One “panacea” followed another. For a while there was yoga. But only by the hour, for there was always someplace to rush off to, someone who needed her, or some obligation she had promised to fulfill. The need she felt to socialize expressed itself in a round with encounter groups. Then she would feel too extraverted, so she would try meditation for a while. The passivity she came to in meditation turned her attention to her body—there was where the problems were impressed, encapsulated, she came to believe. A course of bio-energetics would follow, giving her an opportunity to attack physically each part of the body in which the impress of the psychic pain was being experienced, and to have it pounded or stretched or pushed or pulled into submission. Other techniques, ranging from attempts to control alpha waves in the brain through bio-feedback training, all the way to the scheduled rewards of behavior modification therapy, were attempted by Hannah in the attack on her own nature. In the race to gain control over herself she had failed to learn that she could not do exactly as she willed, and consequently her own nature was destroying her.

In the course of our analytic work, I did not tell her that her own nature, if she continued to heed it so little, would destroy her. I watched with her, the experiences she brought to the analytic sessions, and the effects that these experiences were having upon her. We talked about the high hopes with which she was accustomed to approach each new method or technique. She was interested in analyzing the results of her activities, but always impatient to go on to something else, always wanting to try a new way. For a while she was nearly hysterical between her enthusiasms and disappointments. It was just at this time that Hannah announced her desire to establish and organize a “crisis center” on campus where people who were suicidal, or in some other way desperate, could come for immediate help. The whole proposition was so untimely in view of her own tenuous situation, her own near desperation, that it was not difficult for me to help her come to the realization that the first “crisis patient” would be, or indeed, already was, herself. It was then that she began to become aware of the necessity to look at the crisis within herself, to see what was disturbed there.

But looking within was not so easy. That which was within was so cluttered by all the appurtenances, the many personas she was used to putting on for various occasions, that it was difficult to find out who the “who” was behind all its guises. This involved looking at her behavior, and also at her attitudes, not as something she initiated in order to create an effect, but in a different way. Strange to say, because she had never thought of it in just that way, she had to discover that her ego was not the center of the universe! But it was far more than a new way of thinking. Thinking, in fact, scarcely entered into it. Perhaps it came to her just because necessity made her shift her perspective, and perhaps a factor was the analytic transference itself, through which she observed and experienced the therapist as one who resisted using her own ego to enforce change upon the patient. It was a slow process, the process of change, and mostly it went on under the sur[1]face, below the matters that were actually discussed in the session. Occasionally hints of it emerged in dreams; sometimes they were acknowledged, sometimes that did not seem necessary.

Then there was a vacation for Hannah, a chance to get away from external pressures and to hike in the mountains and sleep under the open sky. Returning, at the beginning of the semester, Hannah announced that she was going to spend a little more time studying, that she was going to limit her other activities to those she could carry on without feeling overburdened. During the past two years, she admitted, she had coasted through graduate school without reflecting on her activities, without seeing what she was experiencing under the wider aspect of the history of human experience. Now she wanted to learn, and to do it at a relaxed and unhurried pace.

In the next weeks I noticed a growing calm in Hannah. At last the day came when it could be expressed. She came into my study, sat down, and was silent for a few moments, and she then told me: “Something important happened to me this week. I discovered what ‘the hubris of consciousness’ means. Oh, I had read many times that the intellectual answers are not necessarily the right answers, but this is not what it is. It is on a much different level than that. It means—one can hardly say it, for if I do I will spoil it, and I don’t want to do that. The striving after awareness—as though awareness were something you could ‘get’ or ‘have,’ and then ‘use’ is pointless. You don’t seek awareness, you simply are aware, you allow yourself to be—by not cluttering up your mind. To be arrogant about consciousness, to feel you are better than someone else because you are more conscious, means that in a similar degree you are unconscious about your unconsciousness.”

Hannah had dreamed that she was in a small boat, being carried down a canal, in which there were crossroads of concrete, which would have seemed like obstacles in her way. But the boat was amphibious, and when it came to the concrete portions it could navigate them by means of retractable wheels.

She took the dream to portray her situation—she was equipped for the journey on which she was embarked, and she was being guided along, within certain limitations, in a direction the end of which she did not foresee. It was not necessary for her to make the vehicle go; all she had to do was to be there and go with it, and she would have time to spare to observe the scenery and learn what she could from everything around her. She was a part of all that, and not any longer one young woman out to save the world, or even a part of it. She was a part of it, and she did not even have to save herself. As she became able to hear with her inner ear the harmony of nature, and to see it with her inner eye, she could begin participating with it and so cease fighting against nature.

She was now experiencing the sense of “flowing along” as a bodily experience, in a body that was not separate from the psychic processes that experienced it. But she would never have known the smoothness, the ease, the utter delight of “flowing along” unless she had come to it as she did, through the confrontation with its opposite, the futile exercise of beating herself against insuperable obstacles.

Obviously, this particular way of coming to a harmonious ego-self relationship is not appropriate or even possible for everyone. People must find their own individual ways, depending on many inner and outer circumstances. Hannah's case is important, however, in that it exemplifies a certain sickness of the Western world, which seems to affect the ambitious, the energetic, the aggressive, and the people who achieve “success,” in the popular sense of the word. These are also the people who, more frequently than not, become weary, depressed, frustrated, dependent on medications, alcohol and illicit drugs to handle their moods, sexually unfulfilled, and who sometimes even admit to being “neurotic.” Unlikely as it may seem, their problem is essentially a religious one; for it has to do with that “hubris of consciousness” which prevents us from looking beyond ourselves for the solution to our problems and for the meaning that lies hidden in all that we do, and see, and are.

Fortunately for us, in the years since Jung’s death, the world has grown smaller and the intellectual intercourse between East and West has increased manyfold. The stream of human beings emigrating from Asia to the West has brought with it the treasures of Taoism and Buddhism. Taoism teaches the joy that derives from blending with the natural forces in the universe, rather than contending with them. The most beautiful metaphor for the path of the Taoist is “the watercourse way, in which one flows, like water, over and under and through every obstacle, with a yielding softness that even wears away rock, on the way to the ultimate destination, the sea. No tortuous tension here, for the one who practices this way finds harmony within and without. Buddhist teachings, on the other hand, provide a complete and specific guide for the conduct of life. The Dalai Lama has expressed the essence of this philosophy as the active practice of compassion toward everything that lives.

Let us hope that the wisdom of the East may prove good medicine for the “sickness of the Western World.”

—June Singer en "Boundaries of the Soul"

#carl jung#Margaret Mead#June Singer#individuation#christ#christianism#boundaries of the soul#the red book#the tibetan book of the dead#the tibetan book of living and dying#sogyal rinpoche#taoism#buddhism#zen

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just as the ocean has waves, or the sun has rays, so the mind's own radiance is its thoughts and emotions. The ocean has waves, yet the ocean is not particularly disturbed by them. The waves are the very nature of the ocean. Waves will rise, but where do they go? Back into the ocean. And where do the waves come from? The ocean.

In the same manner, thoughts and emotions are the radiance and expression of the very nature of the mind. They rise from the mind, but where do they dissolve? Back into the mind. Whatever rises, do not see it as a particular problem. If you do not impulsively react, if you are only patient, it will once again settle into its essential nature.

- Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

#The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying#Sogyal Rinpoche#currently re-reading#Buddhism#tibetan buddhism#meditation

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

チベットの生と死の書 ソギャル・リンポチェ

大迫正弘・三浦順子=訳

講談社

装幀=鈴木一誌、装幀写真=田淵曉

#the tibetan book of living and dying#チベットの生と死の書#sogyal rinpoche#ソギャル・リンポチェ#大迫正弘#三浦順子#hitoshi suzuki#鈴木一誌#田淵曉#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#book cover

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

you can use Wechat to scan this QR code which helps you link to 业余喜马拉雅文化研究 , you also able to press this QR code to visit our website : www.thangka.com.cn in Simple Chinese version.

1 note

·

View note

Video

How an abuse scandal devastated the Buddhist faith community, July 1, 2023

In August 2017, the Dalai Lama’s Buddhist faith community was left reeling by allegations of abuse. It was claimed that the world-famous Lama Sogyal Rinpoche had sexually abused students over many years.

According to the allegations, the Lama Sogyal Rinpoche had been sexually and physically abusing his students for decades. But how could Tibetan Buddhist authorities allow such things to happen? This documentary brings to light crimes long concealed by silence - rapes, psychological manipulation and the embezzlement of funds. Although it enjoys an excellent reputation in the West, Tibetan Buddhism has been rocked by a number of serious scandals. Through the story of Ricardo, abused from childhood and now on a personal quest for justice, this documentary gives a voice to the many victims.

The filmmakers explore the reasons why these scandals were not properly investigated and how the alleged perpetrators, protected by stoic silence, were able to evade justice. Their research takes them to Buddhist centers in France, Belgium, Britain and Spain. And to the northern Indian city of Dharamshala, headquarters of the Tibetan government in exile, which still remains stubbornly silent over these known cases of abuse. Casting all the clichés aside, this investigation takes a deeper look at Buddhist milieus that sometimes manage to dazzle people with their exotic spirituality. The documentary lifts the veil of silence and shows what goes on behind the scenes in some Buddhist faith communities.

Deutsche Welle

#Deutche Welle#religion#abuse#violence#Ricardo Mendes#Buddhism#1980s#1990s#Tibetan Buddhism#France#20th century#Ogyen Kunzang Choling#Robert Spatz#Kunzang Dorje#Sogyal Rinpoche#Château-de-Soleils#exploitation#2010s#21st century#OKC#documentary#accountability#politics#nationalism#Tibet#India#culture#history#China

0 notes

Quote

We must never forget that it is through our actions, words, and thoughts that we have a choice.

Sogyal Rinpoche

#Sogyal Rinpoche#quotes#life#love#important#tumblr#instagood#aesthetic#girl#literature#sad quotes#sad poem#zitate

0 notes

Text

How often attachment is mistaken for love. Even when the relationship is a good one, love is spoiled by attachment, with its insecurity, possessiveness, and pride; and then when love is gone, all you have left to show for it are the souvenirs of love, the scars of attachment.

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

Sogyal Rinpoche

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aforismi sulla meditazione - 1°

Aforismi sulla meditazione – 1°

Gli aforismi sulla meditazione sono spesso spigolature estemporanee e non veri e propri precetti da seguire. Ciò non toglie che sia utile soffermarsi un attimo a riflettere su ciascun messaggio per tentare di coglierne l’insegnamento più recondito. Seguono aforismi di: – Osho – Thynn Thynn – Daniel Naistadt – Hakuin – Ajhan Chah – Tishan – Sogyal Rinpoche – Sharon Salzberg – (more…)

View On WordPress

#aforismi#Ajhan Chah#Daniel Naistadt#Hakuin#illuminazione#libertà#meditare#meditazione#mente#osho#problemi#qui e ora#rifugio#Sharon Salzberg#Sogyal Rinpoche#stress#Thynn Thynn#Tishan

0 notes

Text

Queda no buraco, um hábito enraizado

Queda no buraco, um hábito enraizado

Trecho do livro “O Livro Tibetano da Vida e da Morte” de Sogyal Rinpoche, Editora Prefácio, p. 51-53.

Refletir profundamente na impermanência, tal como fez Krisha Gotami, leva-nos a compreender, no mais profundo no nosso coração, uma verdade que é expressa com muita força nestes versos de um poema do mestre contemporâneo Nyoshul Khenpo:

“A natureza de todas as coisas é ilusória e efémera. Os…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

There are different species of laziness: Eastern and Western. The Eastern style is like the one practiced in India. It consists of hanging out all day in the sun, doing nothing, avoiding any kind of work or useful activity, drinking cups of tea, listening to Hindi film music blaring on the radio, and gossiping with friends. Western laziness is quite different. It consists of cramming our lives with compulsive activity, so there is no time at all to confront the real issues. This form of laziness lies in our failure to choose worthwhile applications for our energy.

—Sogyal Rinpoche

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We often assume that simply because we understand something intellectually…we have actually realized it. This is a great delusion.”

~Sogyal Rinpoche, Tibetan lama, in The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

18 notes

·

View notes