#boundaries of the soul

Text

Psyche in the World

In analysis sometimes there comes a precious moment when the analysand feels the power of a strong insight newly received and thanks the analyst most profusely for the gift. When this occurs in my practice I say to the analysand, “Please remember that what happens in this room is not nearly so important as what happens when you walk out of here. That is what really counts.” All the self-examination that we do is valuable only as an introduction to our real selves as we live in the world. I firmly believe that none of us can be, or should be, so self-involved that the external world pales in importance in comparison with the inner world.

Yet depth psychology, which includes Jungian analysis, psychoanalysis and all their derivations, has been criticized as being solipsistic—and not without reason. Solipsism is nicely defined by Louis A. Sass in his book The Paradoxes of Delusion as “the doctrine in which the whole of reality, including the external world and other persons, is but a representation appearing to a single, individual self.” Sass quotes Wittgenstein as saying that solipsism is an example of a philosophical disease born not of ignorance or carelessness but of abstraction, self-consciousness and disengagement from practical and social activity. This is a serious charge. For most people, most of the time, this is a distinctly undesirable habit of thought. But for others the kind of isolation that provokes this description may be as necessary for the psyche in deep distress as is an intensive care unit for a physical body in a life-threatening situation. During my own analytical training I lived in Zurich for four years without holding a job or having any other major responsibilities. I was intensely focused on my own analysis and on courses at the Jung Institute that only encouraged in[1]tense introversion. For me it was necessary to “disengage from practical and social activity” because at that time these had acquired such a negative tone for me and had been so firmly established in my own mind that there was little hope for a compromise between analysis and a “normal life.” It was necessary for me to establish entirely different patterns of habit and direction if I was to undergo the inner transformation that would free me to live a more balanced and productive life.

I happened to be among the few fortunate people who could afford the luxury of taking a psychological “vacation” from the everyday world for a time and enter into unexplored realms of the psyche’s activity. This luxury was bought at the price of selling my home and other assets to raise the necessary funds for an extended stay in Zurich. I believe that I was temperamentally suited for this particular path, having been deeply interested in the twists and turns of the psyche’s labyrinthine ways since my early teens, but this extremely inward path is not something I would recommend for everyone. It is very strong medicine. In my own practice I usually encourage analysands to try to keep a balance between their inner processes and their lives in the world. I have come to be acutely aware that it is necessary for a person to have a relationship with the world that is compatible with the relationship between the different aspects of the individual psyche. I cannot forget the words of I Corinthians 13:2: “And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge... and have not love—I am nothing.”

There is some valid basis for the criticism that has been leveled against the isolation and self-absorption that intensive psychotherapy sometimes fosters. James Hillman, a Jungian analyst who has given up, or retired from, the practice of Jungian analysis, puts it succinctly in the title of his book, We've Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World's Getting Worse. While I can appreciate his frustration, I must counter with the remark that this is not necessarily indicative of a cause-and-effect relationship; after all, we’ve had more than a hundred years of Western medicine, and the mortality rate in our population is still one hundred percent. And I am not so sure, in response to Hillman, that the world is getting worse. After all, the human race has come to its present condition as a result of its behavior over many thousands of years, and one hundred years is scarcely enough to cure its ills.

Psychotherapy, despite the relatively short period it has been on the scene and despite its limitations, has played an important role in some remarkable changes in human behavior, and its potential for the next century is most promising. However, before this promise can be fulfilled, the means for delivering psychotherapy will have to be adapted to meet the social, economic and political realities of the next decades.

The first century of depth psychology, of Jung, Freud and their followers, was a time in which it was seen as necessary for purposes of psychological health to disengage from the collective. Depth psychology was developing much as an individual person develops during the first half of life. Then the ego, or sense of identity, is just taking form and has to find its stance independent of what surrounds it. So depth psychology has had to make its way, to become known, and to earn respect as a special way of working with the psyche. Perhaps the next century will see a change similar to that which typically occurs during the second half of an individual’s life when the person's values have become broader, when it is not enough for a person to do what is necessary for the individual but which takes into consideration the context in which the individual lives. It is not only the analytic way that must survive then, but what we have learned from analysis can be seen as a source of strength, insight and wisdom that can be injected into society to do its work. In the process analysis may even lose its own identity as a form of psychotherapy, but if the principles it embodies can continue to grow, develop and be fruitful, there is no real loss.

It is not only individuals who are today depressed, unfulfilled, or living without purpose or direction; much of this mood is abroad in the world. Unless consciousness changes, the world cannot change. For the most part, the uses of depth psychotherapy have been limited to a small proportion of the population, people with the economic means, the time, the temperament and the inclination to commit to a long-term project which temporarily may have an emotionally unsettling effect on them. For those who have undergone the process and stayed with it until some salutary results have been achieved, it has had a seminal effect. Most of these individuals have become empowered to live in the world in a different way than before—with greater insight, understanding and compassion for others, and with a perspective on life that goes beyond the satisfaction of their individual needs and desires. By and large, they are people who make valuable contributions to society. Their times of introspection and inner work have helped and continue to help make it possible for them to participate more fully, not less, in the affairs of the world. Change must begin with the individual, but can we any longer afford to heal the ills of the world person by person?

The individuation process, as Jung described it, was the product of a particular time in the history of the analytic process. Jung first defined individuation in 1913, in the initial version of his book on psychological types. He described individuation as “a person’s becoming himself, whole, indivisible and distinct from other people or from collective psychology (although also in relation to these).”! Jung emphasized the attributes of the process as follows: “(1) the goal of the process is the development of the personality; (2) it presupposes and includes collective relationships, i.e., it does not occur in a state of isolation; (3) individuation involves a degree of opposition to social norms which have no absolute validity: The more a man’s life is shaped by the collective norm, the greater is his individual immorality.”

This third point is just the issue with the world that analytical psychology must face today. Jung distrusted “the collective.” He regarded collective norms and collective morality as contrary to the interests of the soul or psyche and believed that it was necessary in the process of psychological development for the individual to stand against “the collective.” Writing just before the onset of World War I, with Switzerland as a neutral country keeping silent while preparations were being made on all sides for the imminent conflict, one could imagine his predicament. In those times, and for many years thereafter, most people—unless they were highly placed in official circles or else working people who were primarily concerned with the burdens of keeping bread on the table and caring for their families—were members of the collective, and were, as we would say today, “politically correct.” They spoke in terms that were agreeable to the ruling classes, and they did not try to overthrow governments. So to advocate standing against the collective was to require a show of courage and conviction. One would have to be singularly devoted to one’s own path to go against the conventional view.

During Jung’s lifetime, analytical psychology was highly suspicious of all kinds of groups. The idea that groups of people reduced everyone down to the lowest common denominator prevailed in Jungian circles. Instead of submitting to the collective, psychological work was to be done in the privileged container of the consulting room between therapist and patient in strict confidentiality. There was no place in Jung’s psychology for marital counseling, family counseling or group therapy. It was not until the 1970s that there could even be a discussion of working on dreams in a group at the Jung Institute in Zurich. This attitude has changed over the years in response to the changing spirit of the times. I know, because I was the first Jungian analyst to give a course on working with dreams in groups there. When I proposed the course a decade or more after Jung’s death, there was a heated debate in the Curatorium (the governing body) as to whether this should be permitted. The “experiment” was tried, with some reluctance on the part of the faculty, but met with an enthusiastic response from the students.

Over the past several decades people have become increasingly liberated from the dictates of the collective. To begin with, the collective no longer exists in the sense of the word as Jung used it. Most countries in the Western world today, and the United States perhaps more than others, have undergone population explosions due as much to immigration as to an increase in births. The result has been a burgeoning diversity in the population with respect to ethnicity, religion, race, sexual orientation, education and socioeconomic status. In the sixties, when we used to speak of “the counterculture,” the image of radical young people who used psychedelics, lived in communes and never trusted anyone over thirty was conjured up. Today we can hardly speak of a counterculture, for our culture is so fragmented now that the majority of the people belong to the “minorities.” And even among the so-called majority there are many political factions, each with enough power to challenge other political factions. The point of this is that there no longer exists anything like what Jung thought of as the collective. Consequently, there no longer exists a counterculture. We are all here together, we members of the motley crew of this spaceship Earth.

A major task of government, including that of the United States, in this last decade of the century seems to be to provide certain umbrella protections and services for its people. This sort of government is subject to and influenced by so many different interest groups, with all the checks and balances that implies, that it cannot be monolithic. Government today is and must be flexible and responsive to its people.

One imperative in the cultivation of this wide area is in the field of health care. The United States is the latest among the developed countries of the Western world to introduce a system which would guarantee basic health care to all its citizens. Mental health care must surely be included as a part of this program. This brings up the question, how is “mental health care” to be defined? Workers in the mental health field know that, in a program designed to provide universal health coverage, choices will have to be made as to who receives care and what kind. Surely the most seriously disturbed patients, people who would endanger themselves or others, will be the first to be included in the plan, followed by those who absolutely cannot manage to live outside of a protected environment. Next will come those whose functioning is sufficiently impaired to make it difficult for them to work or to attend school or to live with others or independently. Mental illness based on organicity and the treatment of addictions will surely be included. Treatment of the criminally insane must be a part of the package of covered services.

Near the end of the list will be short-term outpatient psychotherapy. This suggests that treatment will be available mostly to solve immediate problems or crisis situations. All mental health services will be “managed,” that is, they will be subject to the approval of officials who have never seen the patient and whose decisions are largely based on protocols and economic considerations. Under such a program many people will receive affordable care that would not otherwise be available to them. But there will remain many people whose needs do not fall within the scope of the basic health care that is proposed or provided.

Long-term depth psychotherapy or analysis for people who are not seriously disturbed or dysfunctional may very well be considered to be outside the limits of the health care system. Analytic work does not focus primarily on immediate problems, but seeks to use the presenting symptoms as keys to understanding whole persons in the fullness of their beings. It does not simply try to remove or cover up the symptoms, but rather to discover their meaning and their message. The analytic process does not attempt to restore the individual to the former state that existed before the circumstance or condition that brought about the request for therapy. Rather, it seeks a more radical re-formation of the personality by integrating the different aspects of the psyche into a more harmonious whole. Body, mind and spirit are the realm of the analytic process. As with the remodeling of a building, it is usually necessary to go through a “demolition” phase before progress can be seen. In depth psychotherapy things may appear to get worse before they get better. The goal is not merely a restoration to “health,” but a sense of wellness that surpasses anything that existed in this individual before. This comes about as the result of what Jung called a new Weltanschauung or “world view,” which develops in the course of the analytic process.

The question must surely arise as to whether this kind of long-term depth psychotherapy, including analysis, can be considered “basic health care.” How does a health care system define those of us who give this kind of care? How do we define ourselves? At this writing, it is not yet clear what the health care system will cover finally in the area of mental health but the likelihood is that other types of treatment will be given priority over depth psychology for some time to come. The practice of Jung’s psychology may have to redefine itself if it is to survive in this climate.

Jung's psychology, and all psychology that seeks to probe the depth and meaning of human experience, make a contribution not only to the well-being of individuals, but to how they view the world and how they will influence it. There will always be those who seek the level of understanding toward which depth psychology strives. It has been said that this kind of work is elitist, available only to those who have the financial and educational resources to be able to enter fully into it. This is only partly true. Many people have sacrificed time and money and other activities they valued, to be able to do analytic work even if they did not have health care coverage for this. Yet many who have not been able to do this have an inner commitment to follow the path that leads toward greater consciousness in whatever way is possible for them.

I remember hearing my colleague Clarissa Pinkola Estés, author of Women Who Run With the Wolves, saying that she is a confirmed storyteller who supports her habit by doing Jungian analysis for a living. Perhaps some of us Jungian analysts will have to turn the tables and support our habit of practicing analysis with doing some other types of psychotherapy for a living. We can add many therapeutic skills to our repertoire that will serve purposes similar to the classical analysis, but will be more accessible to more people. I have discovered a few ways to do this over the years, and I would not be surprised to learn that many of my colleagues have done similar kinds of work, using the insights they have gleaned from ana[1]lytic practice and applying them in other contexts. Often the adage “Necessity is the mother of invention” proves its worth.

My first opportunity to utilize this principle came about when I returned to Chicago from Zurich after finishing my analytic training. Since it would take time to build an analytic practice in a community where there had been no Jungian analyst before, it was necessary for me to take a paying job. The only position I could find that even remotely matched my qualifications was in a school for emotionally disturbed preschool children. To be honest, the job description called for a social worker, but I persuaded the director to change the title to psychologist. I imagined I would be doing in-depth work individually with the parents but this proved to be far from the case. I was told in no uncertain terms that this was a “family agency, and I would be obliged to work with the entire family, although I might later see one or another member of the family individually if that seemed appropriate. Having been trained to help the individual differentiate from the matrix of home and family and find his or her unique path, it went against everything I knew to see people in the context in which they lived. I expected people to come to my office, one at a time, and engage in dialogue with me. Can you imagine my feeling when I was told that I had to make a home visit on each case, spending time with the whole family, observing their interactions? Remember, this occurred in 1965, when family therapy was very new and few people had even heard of it. Because it was for me a matter of survival, I made that first home visit. What happened totally amazed me! Even if I had not spoken a word, to see before me the home with its decor that expressed the taste and interests of those who lived in it, the way the children’s toys were scattered about, showing how strict or permissive the household was, the way the parents spoke to their children and vice versa, the relationship between the husband and the wife, the effort to make a good impression upon me or the lack of it, the ability on the part of everyone to deal with the unexpected—all this was sending messages to me that I never in a thousand years would have perceived from the analyst’s chair in my office. I began to see that there were other ways. And still, with this first family, I discovered in the father a deep desire to understand his own nature, that included and went beyond his interest in developing a more harmonious relationship within the family. So, when I did have occasion later to work individually with the father, our interaction had more of the character of an ana[1]lytic session. This did not interfere with my work with the mother or with the identified patient, who was the child in the school. I also learned there to do child therapy using small dolls and other figures to help children dramatize their own experiences with significant others in their lives. One result of this was that I later studied family therapy and learned how to use its methods to enhance the understanding I had of the structure of the psyche. Today, I have more choices as to how I will work with a person or family than I would have had otherwise.

Over the years my therapeutic tools have grown more numerous and varied as I have taught and given workshops in humanistic and transpersonal psychology using many approaches and techniques applicable to individuals and groups. I have found that certain principles learned from Jung’s psychology are applicable to other methods of psychological work. I will mention just a few of these. The first principle is the importance of insight into the projection mechanism, whereby we project aspects of our own unconscious qualities onto others and behave as if the others who receive the projection are really what we imagine them to be. Analysis gives us the tools to recognize those projected aspects of ourselves and to reclaim them. This is particularly helpful, for example, for people who see themselves as being driven by someone to do something. This makes them feel helpless. In reality they drive themselves, but don’t see it until they recognize that the slave driver is not outside so much as within, where it is subject to being transformed. Another principle has to do with taking personal responsibility—not for everything that happens to us, surely, but for the way we respond to events and circumstances. A third principle is the necessity of becoming aware of how we may be facilitating another person’s negative behavior without realizing it. This is a principle that has been emphasized in the vast literature on co-dependence. The corollary to this, of course, is, how can we use consciousness to facilitate another person's positive behavior?

Still another principle has to do with avoiding the “victim” or scapegoat role. One thing I learned to accept early in my analysis is that the person who gets abused is the one who allows herself to be abused. This may seem like an overstatement, but it is probably true more often than not. And the last principle that I will note here, although there are many others that could be included, is the importance of ceasing to be re[1]active to external situations and to take instead a pro-active role in which the authentic person that you are is taking charge of your actions.

Let me cite an example of how some of these principles can be taken into the world and utilized outside of the analytic setting. Janet, an analysand of mine, had gone through certain experiences in her childhood and early adolescence that led her to feel victimized. These had been a source of ongoing pain for her. Being pro-active, she decided to do some research on how other women, similarly abused, had managed to recover sufficiently to lead successful and productive lives despite their early traumatic experiences. She assembled a small group of women and met weekly with them in a setting where they could tell their stories and share with one another their experiences of coping with their distress. In the course of these meetings the women developed a practical program for overcoming the “victim mentality.” Janet then went on to teach the tested methods to other women.

Our society is replete with opportunities for the insights gained from depth psychology to be applied to social problems. The challenge to depth psychology is to find more ways to widen the area of its influence so that it permeates not only the field of health care, but also education, family life, the workplace, the economy, foreign policy and the ecology of nations. All these areas have a stake in achieving productive change, inasmuch as all are interrelated and interdependent parts of a whole. This is a large order. Long-term goals are easy to put aside when there are so many urgent needs crying for attention. To be sure, society needs people to put out the fires, but it also needs people to scan the entire terrain and see where the trouble spots are and how each one is related to or dependent upon another. The question that properly comes up next is, where do we find the resources to bring about the hoped-for change in consciousness? Who are the people who can help?

Let me suggest that we do not first call upon the people who have been the driving forces in the contemporary culture. We have already heard the voices of the arbiters of cultural consciousness. What we have heard far less are the voices of what we could call the cultural unconscious—or the less vocal parts of society. These people watch and listen, they observe and reflect. They know far more than most people give them credit for. It is time to ask them what they see, what they need and what they can contribute. We might begin by asking the ordinary person who is just struggling to get along in the world.

Immediately after the earthquake that rocked Los Angeles in January 1994, well-meaning social agencies prepared large buildings, schools, armories and the like to house the people who had been left homeless when the quake suddenly destroyed their homes at four thirty-one one Monday morning. Most of these people refused to go into the strong buildings, but insisted on sleeping out in the open. They were afraid that the buildings would collapse on them, and no amount of reasoning could reassure them otherwise. The relief workers listened to the people who knew what they needed, and set up canvas tents where they could feel safe in the open air with the ground underneath them and only a canvas shell between themselves and the sky. We learned from them that it is not useful to ignore the sensitivities of people.

Another resource is the elders of the community. Most younger people do not realize that elders, those who have cultivated their inner lives, are different from younger people in that they have less invested in their personal concerns. Having experienced losses of every kind in their lives, they realize that personally they have not much more left to lose and that the little that they have will also be gone before too long. They are interested not in sowing for a future harvest for themselves, but in making the most of what remains to them in time, in energy, in wisdom. They have seen eras of good fortune and eras of ill fortune come and go, and they know that everything changes, so they are not easily upset by the events of the moment. They may sometimes counsel just to wait, it will be different soon. They have watched history unfold, and they can foretell with uncanny sureness when the lesson we have not learned from history will present itself again in a slightly different form. The elders who have continued to enjoy a lively interest in the world around them have much to teach younger people.

Another resource: indigenous peoples. Almost everywhere in the days before colonial powers set forth into so-called primitive lands, including the land that has come to be the United States, people accepted life and death and the sometime violence of nature as quite natural. They did not attempt to exert control over nature. They lived as an integral part of their environment, drawing what they needed from it and no more, without trying to store up life's bounty for the future. Lands were not privately owned. The indigenous people did not exploit or deplete the land, but developed a reciprocal relationship with the environment. They taught their children what they needed to know to live in their world. They perceived the world as a spiritual existence embodied in the garments of nature—every tree and stone contained a spirit that was akin to the divine spirit. And so, guided by the spirit within, which we might call the voice of the unconscious, they trusted the ways of the world and shared its bounty with one another. Their respect has been for their ancestors and their concern is for the generations that will follow them. We can learn from these people, not by imitating their superficial representations, but by allowing them to be heard and listening closely to them while they tell us what they know.

Another resource is the immigrants who have recently arrived. Americans tend to forget that we are, by and large, the children and grandchildren of immigrants—the people who built this country with their own sweat and aspiration. A small boy in school was told by his teacher, “Now we are going to study native Americans.” “Native Americans?” he cried out with some indignation. “Aren't I a native American? I was born here!” Yes, almost all natives of our land are the sons and daughters of those who came here as strangers. And others continue to come to our shores. It is the great variety of languages and customs and information that the strangers have brought that has grown into the eclectic mix of people we call Americans. Each ancestral tradition has taught its children something which they have carried to their new homeland. These are treasures and should be so regarded. Their very multiplicity underscores the psychological reality that we can and must retain our unique characteristics while blending harmoniously with the whole society.

Then there are the wisdom teachers, for example, the Tibetan masters. Forced out of their own country where they were isolated from the rest of the world, they fled, carrying with them the knowledge of things mysterious that are un[1]known here. Had it not been for their uprooting and their exile, we would not have access to their traditions concerning life and death, birth and rebirth. They give freely of their wisdom to those who will listen. There is much to be learned from these people, but even a little can be surprisingly enriching. The Dalai Lama once said, “My religion is very simple. Kindness.” What a profound teaching!

The gay and lesbian community is another resource from which we can learn. I have asked myself, why is it that there are so many creative people in the arts among these men and women, far disproportionate to their numbers? My speculation has suggested at least two possible reasons. These are people who have distanced themselves from the straight and unyielding mores of a more conservative society, with all its sexual constraints and fears, to experience the reality of their own natures. In order to do this, they have had to defy convention. Their willingness to stand against the prejudices of people with closed minds was then extended beyond the realm of sexual preferences to preferences in the arts and in other areas where individuality was valued above conformity. Another contributing factor may be that many gay and lesbian people do not have families to support, and consequently they may have more freedom to pursue the careers and avocations of their choice. They can teach us much about creativity and its costs. Politically, these people have called our attention to the important principle of equal rights for all, something everyone professes to believe in but tends to forget from time to time. They can also teach us much about love and loss and pain, and how members of a community can support one another in the most difficult of times.

We might listen, too, to the many families who are deserting the cities with all their pressures and choosing life in small towns or rural settings. These are people who want to live in more natural surroundings. What are they seeking that life in our high-powered cities no longer offers them? What are they learning and what can they teach the rest of us?

Big businesses that want to improve their functioning are listening more and more to people in the rank and file of their organizations. It is the people whose hands are on the machinery who understand what is going on, what needs to be done to improve things, and how to go about making changes. “Management by walking around” is a good principle, because how can you know what to do unless you know what is being done? The efficiency of the hierarchical structures that characterized business organizations in the past is being seriously questioned now. Businesses are asking, how can we make the most of our human resources? Consultants with an understanding of depth psychology are being called in to “diagnose” the ills of the business and to help in developing “treatment plans.”

There is one more frontier I want to mention in which the insights of psychology have been moving out of the consulting room and into the world. This is the area of illness and health. It is generally accepted today that almost all physical or organic diseases have psychological components. Physical and psychological problems are not separate entities, but are closely interrelated, for our emotional state affects the body and vice versa. Each person is a complex of body, mind and spirit (though the third aspect is not yet so widely recognized as a universal aspect of the human condition). The psyche, which is composed of mind and spirit, exerts a profound influence on the course of physical illness. We can will ourselves to die or we can surprise our doctors by the degree to which our own psychological practices can bring about “spontaneous” self-healing. This potential has been well known for many centuries by those engaged in healing professions. It has only been since the so-called scientific revolution—which began after the schism between faith and reason brought about by the seventeenth-century Enlightenment—that medical science turned away from the less rational means of healing and sought cures based on scientific methods of research and treatment. This development resulted in tremendous advances in knowledge about the body and in the technology and techniques of medical treatment. However, for quite some time, modern medicine’s obsession with the treatment of the disease left little time or energy for attention to the treatment of the patient. The patient, too often, was “the appendicitis in Room 304.” Meanwhile, the care of the person—by which I mean the suffering human soul—was left to those who ministered specifically to the individual’s own experience of disease, among them the priest, minister, rabbi, shaman, medicine man, herb doctor, faith healer and psychotherapist. These were people skilled in the mysterious arts that have to do with the invisible aspects of the human being as they interact with the invisible in the world: love and pain, purpose and meaning—the list could go on and on.

More recently, members of the medical profession have come to realize the importance of attending to these less tangible aspects of sickness and health. It is widely recognized in medical circles now that the patient’s attitude has much to do with the progress of the illness and the efficacy of the treatment. Clergy do pastoral counseling and are members of the hospital staff. Psychologists work in close cooperation with physicians. Biological medicine has made great advances in the use of psychoactive drugs. Most psychiatrists and other physicians recognize that these medications, while often helpful in themselves, can serve mental patients more effectively when combined with psychotherapy that seeks to support the emotional experience of the patient, to uncover the root causes of the distress and to help the individual come to terms with these. On the other hand, today’s psychologists recognize the value of psychoactive medications in helping some patients become more accessible to psychotherapy than they would be without them.

Prevention of illness and the quest for optimal wellness (or peak performance) are related areas in which some of Jung’s insights can be helpful. Jung’s psychology is, above all, optimistic. It is not so much oriented backward toward the cause of dysfunction as it is oriented forward, toward what the psyche can be when it is fully developed. It asks questions like, Who am I? What am I meant to be? What is my potential? The implication is that all that we can be is already present in us in potential, waiting to be awakened, like Sleeping Beauty awaiting her prince. It is the task of those who have been working in the field of developing a wider consciousness to point out the path through the maze of brambles that is life; but it is the individual who must walk that path with courage, taking responsibility for his or her own journey. So the pursuit of wellness requires both knowledge and practice. The knowledge is both within the psyche in terms of a sense of what is right for us as individuals, and out in the world where we can learn from the experience of others. The practice lies in right living, in nutrition and exercise and self-understanding and a refusal to pursue a path that leads away from wholeness. For wholeness, health and healing all come from the same root—and essentially they are all one.

—June Singer en "Boundaries of the Soul"

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cross has trouble getting to sleep alone in his room and goes looking for a distraction, but ends up finding a solution for both of them

#UTDR#UTMV#Cross Sans#Killer Sans#Kross ship#(Kinda. It's up to interpretation)#Long post#I'm so sorry I didn't mean for it to be THIS much#I started this like a week ago -A-#Lies down and lets out a long howl it's finisheeeeeed#I could have just drawn them spooning and written the rest but noooo I love to do things the hard way#Anyway I think they should be bed buddies#The company helps Cross relax enough to sleep and the touch helps knock Killer out#Cross has to be big spoon because otherwise Killer's soul gets squished and it's too uncomfortable to sleep#Also I realised Cross and Nightmare are the only two in the castle who didn't have knock knock jokes in their backstory#I like to imagine Nightmare has had similar confusing interactions with at least one of them#Cross probably spends the rest of the day panicked that he overstepped a boundary or the others will make fun of him#Not realising that Dust and Horror have fallen asleep together many times#Or that Killer hasn't slept properly in weeks and he's in heaven#I'm NOT drawing a follow up so just imagine Killer coming to Cross's room the next night and finding every excuse to stay#Because he wants it to happen again but he has no idea how to ask (and also Cross seems kinda awkward about it)#Absolutely terrified that I spent my whole week off working on this and it might be not that great so I hope at least one person likes this

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

#self awareness#self understanding#inner healing#inspiration#mindfulness#motivation#wisdom#omnism#omnist#soul path#aesthetic#art#images#marisareneebailey#self care#self worth#self respect#let go#guilt#saying no#boundaries#wellbeing#mental health#therapy#spiritual#self empowerment#healing journey#recovery#self acceptance#self love

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

It might seem crazy but I'm in love with these creatures ♡

#dark romance#dark academia#dark aesthetic#gothic#horror#ghost#dead souls#love has no boundaries#inferno#evil#angel#angelcore#love#goth aesthetic#spooky#tumblr 2014#im just a girl#so freaking hot

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

I played hauntii over the long weekend, I had it wishlished for a long while, and I don’t know if I want to recommend it or not to be honest. It’s so simple and pretty, the music is a delight, it’s somber (it is about ghosts) and if u like sky:cotl u will probably like it. The art and animation of the game is amazing, I kinda want to eat it. It’s mostly about wandering around and solving puzzles with combat here and there with interesting mechanics I won’t spoil. Any fighting is very simple but it’s unreasonably brutal. Any hit is a full heart and once u respawn u are given 2 hearts and absolutely no way to get health back. This art style makes depth perception a struggle so u would think they’d compensate by making hits land gentler and health easier to gain back. But no. This is an indie game that came out a couple of days ago so it’s quite bugged. I’d say give it a go in a couple of months and please be aware that there is black and white flashing during some scenes and the screen flashes red when u lose health

#whyyyy is it so brutal I don’t understand#even dark souls games are not this cruel#sheesh#one of my favourite things about this game is how they establish boundaries - invisible walls#with the dark and how much time u can spend in it

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

two horses attempting to smooch despite the barriers keeping them apart in their stalls this is a testament to the beauty of love and how it permeates all life not just us humans

#this is also me with our TWO HUNDRED FIFTY FOLLOWERS we are kept apart by internet boundaries but we are together in the stable of the soul#horse#horses#horse pics#reaction pics#reaction image#reaction images#joy#love#submission#neighhhh

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

#divine feminine#feminine#virgo rising#self love#spiritual awakening#spiritualgrowth#dark night of the soul#healing#inner child#inner work#inner peace#meditation#sacred feminine journey#soul journey#feminine journey#the sacred feminine#self protection#boundaries#standards#high standards#high priestess#journaling#self reflection#transformation#evolution#transcendence#spiritual enlightment#transition#growth#soul growth

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

No is a complete sentence.

#boundaries

#histhoughtslately#htl#life quotes#life path#no#boundaries#love#mental health#healthy lifestyle#spilled thought#spilled writing#self care#lit#literature#writing#inspirational quotes#motivational quotes#soul connection#heal#healing journey#healing heart#self healing#higher self

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I’m the anon who posted a little while ago to ao3shenanigans about receiving hurtful concrit on a fic. I just noticed your reblog there, and wanted to say thanks for the solidarity. Because I’m a chronic people-pleaser I actually thanked the commenter for making an attempt to help me (kinda wish I hadn’t), but if/when this happens again I will remember your advice about boundaries. Take care!

Oh, I'm so glad you reached out!! I wasn't sure if I was overstepping 😅 But omg I understand the people pleasing thing—I thanked my hurtful commenter, too!!! At least once, I replied something like "thanks for sticking with the fic despite disliking xyz" 🤦🏻 Definitely wish I'd just set the boundary from the start.

Hope you're doing well and writing what and how you want 💛

#thank you for feeding the ask box#ao3 comments#fandom etiquette#god and that comment followed a mega chapter that i'd poured my soul into#just stab me in the heart why don't you#please commenters just focus on the positive!!#writers are already grappling with insecurities and doubts#no need to pile on more#and writers please set boundaries with readers when necessary#for your sake and everyone else's#nip that behavior in the bud

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The red book

[…].Rather, he saw that each person’s consciousness emerges like an island from the great sea in which all find their base, with the rim of wet sand encircling each island corresponding to the “personal unconscious.” But it is the collective unconscious—that sea—that is the birthplace of all consciousness, and from there the old ideas arise anew, and their connections with contemporary situations are initiated.

[…]

At times during this period, Jung was so overcome with emotion that he feared that he might be in danger of losing his psychic balance altogether. Writing down the material helped him to keep it under control, since once it was objectified he could then turn his mind to other things, secure in the knowledge that the unconscious material was safe from loss or distortion. During this strained and difficult period of his life he never withdrew from his routine of active work and related[1]ness to his family. Life with his wife and children proved to be a stabilizing influence, as also was his psychiatric practice. He forced himself to move back and forth from the conscious position with its distinct, if temporal, demands—to the unconscious one. Gradually he attained a capacity for granting each position its important role in his life and, when it was necessary, to allow the interpenetration of the one by the other.

[…]. He had the courage to state that psychotherapy cannot be defined altogether as a science. In making a science of her, he said, “the individual imagines that he has caught the psyche and holds her in the hollow of his hand. He is even making a science of her in the absurd supposition that the intellect, which is but a part and a function of the psyche, is sufficient to comprehend the much greater whole.”

The word “science” comes from the Latin scientia, which means knowledge, and therefore is identified with consciousness and with the intellectual effort to draw into consciousness as much knowledge as possible. But, with our psychological concept of the unconscious, and with all the evidence that has emerged to justify its reality, it is necessary to recognize that there is a very large area of human experience with which science cannot deal. It has to do with all that is neither finite nor measurable, with all that is neither distinct nor—potentially, at least—explicable. It is that which is not accessible to logic or to the “word.” It begins at the outermost edge of knowledge. Despite the continuing expansion or even explosion of information, there will forever be limits beyond which the devices of science cannot lead a man.

It becomes a matter of seeing the “created world” in terms of a “creating principle.” This is difficult when we conceive of ourselves as being among “the created” and hence being unable to comprehend that which was before we existed and which will continue after the ego-consciousness with which we identify ourselves no longer exists in the form in which we know it. We cannot, however much we strive, incorporate all of the unconscious into consciousness, because the first is illimitable and the second, limited. What is the way then, if there is a way, to gain some understanding of unconscious processes? It seemed to Jung, as it has to others who have set aside the ego to participate directly in the mystery, that if we cannot assimilate the whole of the unconscious, then the risk of entering into the unfathomable sphere of the unconscious must be taken.

It is not that Jung deliberately sought to dissolve the more or less permeable barrier between consciousness and the unconscious. It was, in effect, something that happened to him— sometimes in dreams, and sometimes in even more curious ways. Under the aegis of Philemon as guiding spirit, Jung submitted himself to the experience that was happening to him. He accepted the engagement as full participant; his ego remained to one side in a non-interfering role, a helper to the extent that observation and objectivity were required to record the phenomena that occurred. And what did occur shocked Jung profoundly. He realized that what he felt and saw resembled the hallucinations of his psychotic patients, with the difference only that he was able to move into that macabre half world at will and again out of it when external necessity demanded that he do so. This required a strong ego, and an equally strong determination to step away from it in the direction of that superordinate focus of the total personality, the self.

However, we must remember that it was with no such clearly formulated goal that Jung in those days took up the challenge of the mysterious. This was uncharted territory. He was experiencing and working out his fantasies as they came to him. Alternately, he was living a normal family life and carrying on his therapeutic work with patients, which gave him a sense of active productivity.

Meanwhile, the shape of his inner experience was becoming more definite, more demanding. One day he found himself besieged from within by a great restlessness. He felt that the entire atmosphere around him was highly charged, as one sometimes senses it before an electrical storm. The tension in the air seemed even to affect the other members of the house[1]hold; his children said and did odd things, which were most uncharacteristic of them. He himself was in a strange state, a mood of apprehension, as though he moved through the midst of a houseful of spirits. He had the sense of being surrounded by the clamor of voices—from without, from within—and there was no surcease for him until he took up his pen and began to write.

Then, during the course of three nights, there flowed out of him a mystifying and heretical document. It began: “The dead came back from Jerusalem, where they found not what they sought.” Written in an archaic and stilted style, the manuscript was signed with the pseudonym of Basilides, a famous gnostic teacher of the second century after Christ. Basilides had belonged to that group of early Christians which was declared heretical by the Church because of its pretensions to mystic and esoteric insights and its emphasis on direct knowledge rather than faith. It was as though the orthodox Christian doctrine had been examined and found too perfect, and therefore incomplete, since the answers were given in that doctrine, but many of the questions were missing. Jung raised crucial questions in his Seven Sermons of the Dead. The blackness of the nether sky was dredged up and the paradoxes of faith and disbelief were laid side by side. Traces of the dark matter of the Sermons may be found throughout the works of Jung which followed, especially those which deal with religion and its infernal counterpoint, alchemy. All through these later writings it is as if Jung were struggling with the issues raised in the dialogues with the “Dead,” who are the spokesmen for that dark realm beyond human understanding; but it is in Jung’s last great work, Mysterium Coniunctionis, on which he worked for ten years and completed only in his eightieth year, that the meaning of the Sermons finally finds its definition. Jung said that the voices of the Dead were the voices of the Unanswered, Unresolved and Unredeemed. Their true names became known to Jung only at the end of his life.

The words flow between the Dead, who are the questioners, and the archetypal wisdom which has its expression in the individual, who regards it as revelation. The Sermons deny that God spoke two thousand years ago and has been silent ever since, as is commonly supposed by many who call themselves religious. Paul, whose letters are sometimes referred to as “gnostic,” supported this view in his Epistle to the Hebrews (1:1), “God who at sundry times and in divers manner spake in time past unto the fathers by thy prophets, hath in these last days spoken unto us by his Son .. .” Revelation occurs in every generation. When Jung spoke of a new way of understanding the hidden truths of the unconscious, his words were shaped by the same archetypes that in the past inspired the prophets and are operative in the present in the unconscious of modern man. Perhaps this is why he was able to say of the Sermons: “These conversations with the dead formed a kind of prelude to what I had to communicate to the world about the unconscious: a kind of pattern of order and interpretation of all its general contents.”

I will not attempt here to interpret or explain the Sermons. They must stand as they are, and whoever can find meaning in them is free to do so; whoever cannot may pass over them. They belong to Jung’s “initial experiences” from which derived all of his work, all of his creative activity. A few excerpts will offer some feeling for the “otherness” which Jung experienced at that time, and which was for him so germinal. The first Sermon, as he carefully lettered it in antique script in his Red Book, begins:

The dead came back from Jerusalem where they found not what they sought. They prayed me let them in and besought my word, and thus I began my teaching.

Hearken: I begin with nothingness. Nothingness is the same as fullness. In infinity full is no better than empty. Nothingness is both empty and full. As well might ye say anything else of nothingness, as for instance, white it is, or black, or again, it is, not, or it is. A thing that is infinite and eternal hath no qualities, since it hath all qualities.

This nothingness or fullness we name the pleroma.

All that I can say of the pleroma is that it goes beyond our capacity to conceive of it, for it is of another order than human consciousness. It is that infinite which can never be grasped, not even in imagination. But since we, as people, are not infinite, we are distinguished from the pleroma. The first Sermon continues:

Creatura is not in the pleroma, but in itself. The pleroma is, both beginning and end of created beings. It pervadeth them, as the light of the sun everywhere pervadeth the air. Although the pleroma pervadeth altogether, yet hath created body no share thereof, just as a wholly transparent body becometh neither light nor dark through the light which pervadeth it. We are, however, the pleroma itself, for we are a part of the eternal and the infinite. But we have no share thereof, as we are from the pleroma infinitely removed; not spiritually or temporally, but essentially, since we are distinguished from the pleroma in our essence as creatura, which is confined within time and space.

The quality of human life, according to this teaching, lies in the degree to which each person distinguishes herself or himself from the totality of the unconscious. The wresting of consciousness, of self-awareness, from the tendency to become submerged in the mass, is one of the most important tasks of the individuated person. This is the implication of a later passage from the Sermons:

What is the harm, ye ask, in not distinguishing oneself?

If we do not distinguish, we get beyond our own nature, away from creatura. We fall into indistinctiveness . . . We fall into the pleroma itself and cease to be creatures. We are given over to dissolution in the nothingness. This is the death of the creature. Therefore we die in such measure as we do not dis[1]tinguish. Hence the natural striving of the creature goeth to[1]wards distinctiveness, fighteth against primeval, perilous sameness. This is called the principium individuationis. This principle is the essence of the creature.

In the pleroma all opposites are said to be balanced and therefore they cancel each other out; there is no tension in the unconscious. Only in man’s consciousness do these separations exist:

The Effective and the Ineffective.

Fullness and Emptiness.

Living and Dead.

Difference and Sameness.

Light and Darkness.

The Hot and the Cold.

Force and Matter.

Time and Space.

Good and Evil.

Beauty and Ugliness.

The One and the Many...

These qualities are distinct and separate in us one from the other; therefore they are not balanced and void, but are effective. Thus are we the victims of the pairs of opposites. The pleroma is rent in us.

Dualism and monism are both products of consciousness. When consciousness begins to differentiate from the unconscious, its first step is to divide into dichotomies. It proceeds through all possible pairs until it arrives at the concept of the One and the Many. This implies a recognition that even the discriminating function of consciousness acknowledges that all opposites are contained within a whole, and that this whole contains both consciousness and that which is not conscious. Here lies the germ of the concept marking the necessity of ever looking to the unconscious for that compensating factor which can enable us to bring balance into the one-sided attitude of consciousness. Always, in the analytic process, we search the dreams, the fantasies, and the products of active imagination, for the elements that will balance: the shadow for persona-masked ego, the anima for the aggressively competitive man, the animus for the self-effacing woman, the old wise man for the puer aeternus, the deeply founded earthmother for the impulsive young woman. We need to recognize the importance of not confusing ourselves with our qualities. I am not good or bad, wise or foolish—I am my “own being” and, being a whole person, I am capable of all manner of actions, good and bad wise and foolish. The traditional Christian ideal of attempting to live out only the so-called higher values and eschewing the lower is proclaimed disastrous in this gnostic “heresy.” The traditional Christian ideal is antithetical to the very nature of consciousness or awareness:

When we strive after the good or the beautiful, we thereby forget our own nature, which is distinctiveness, and we are delivered over to the qualities of the; pleroma, which are pairs of opposites. We labour to attain to the good and the beautiful, yet at the same time we also lay hold of the evil and the ugly, since in the pleroma these are one with the good and the beautiful. When, however, we remain true to our own nature, which is distinctiveness, we distinguish ourselves from the good and the beautiful, and therefore, at the same time, from the evil and ugly. And thus we fall not into the pleroma, namely, into nothingness and dissolution.

Buried in these abstruse expressions is the very crux of Jung’s approach to religion. He is deeply religious in the sense of pursuing his life task under the overwhelming awareness of the magnitude of an infinite God, yet he knows and accepts his limitations as a human being. This makes him reluctant to say with certainty anything about this “Numinosum,” this totally “Other.” In a filmed interview Jung was asked, “Do you believe in God?” He replied with an enigmatic smile, “I know. I don't need to believe. I know.” Wherever the film has been shown an urgent debate inevitably follows as to what he meant by that statement. It seems to me that believing means to have a firm conviction about something that may or may not be debatable. It is an act of faith, that is, it requires some effort. Perhaps there is even the implication that faith is required because that which is believed in seems so preposterous. On the other hand, it is not necessary to acquire a conviction about something if you have experienced it. I do not believe I have just eaten dinner. If I have had the experience, I know it. And so with recognizing the difference between religious belief and religious experience. Whoever has experienced the divine presence has passed beyond the requirement of faith, and also of reason. Reasoning is a process of approximating truth. It leads to knowledge. But knowing is a direct recognition of truth, and it leads to wisdom. Thinking is a process of differentiation and discrimination. In our thoughts we make separations and enlist categories where in a wider view of reality they do not exist. The rainbow spectrum is not composed of six or seven colors; it is our thinking that determines how many colors there are and where red leaves off and orange begins. We need to make our differentiations in the finite world in order to deal expediently with the fragmented aspects of our temporal lives.

The Sermons remind us that our temporal lives, seen from the standpoint of eternity, may be illusory—as illusory as eternity seems when you are trying to catch a bus on a Monday morning. Either seems false when seen from the standpoint of the other. Addressed to the Dead, the words that follow are part of the dialogue with the unconscious, the pleroma, whose existence is not dependent on thinking or believing.

Ye must not forget that the pleroma hath no qualities. We create them through thinking. If, therefore, ye strive after difference or sameness, or any qualities whatsoever, ye pursue thoughts which flow to you out of the pleroma; thoughts, namely, concerning non-existing qualities of the pleroma. In as much as ye run after these thoughts, ye fall again into the pleroma, and reach difference and sameness at the same time. Not your thinking, but your being, is distinctiveness. Therefore, not after difference, as ye think it, must ye strive; but after your own being. At bottom, therefore, there is only one striving, namely, the striving after your own being. If ye had this striving ye would not need to know anything about the pleroma and its qualities, and yet would come to your right goal by virtue of your own being.

The passage propounds Jung’s insight about the fruitlessness of pursuing philosophizing and theorizing for its own sake. Perhaps it suggests why he never systematized his own theory of psychotherapy, why he never prescribed techniques or methods to be followed. Nor did he stress the categorization of patients into disease entities based on differences or samenesses, except perhaps as a convenience for purposes of describing appearances, or for communicating with other therapists. The distinctiveness of individual men or women is not in what has happened to them, in this view, nor is it in what has been thought about them. It is in their own being, their essence. This is why a man or woman as therapist has only one “tool” with which to work, and that is the person of the therapist. What happens in therapy depends not so much upon what the therapist does, as upon who the therapist is.

The last sentence of the first Sermon provides the key to that hidden chamber which is at once the goal of individuation, and the abiding place of the religious spirit which can guide us from within our own depths:

Since, however, thought estrangeth from being, that knowledge must I teach you wherewith ye may be able to hold your thought in leash.

Suddenly we know who the Dead are. We are the dead. We are psychologically dead if we live only in the world of consciousness, of science, of thought which “estrangeth from being.” Being is being alive to the potency of the creative principle, translucent to the lightness and the darkness of the pleroma, porous to the flux of the collective unconscious. The message does not decry “thought,” only a certain kind of thought, that which “estrangeth from being.” Thought—logical deductive reasoning, objective scientific discrimination— must not be permitted to become the only vehicle through which we may approach the problematic of nature. Science, and most of all the “science of human behavior,” must not be allowed to get away with saying “attitudes are not important, what is important is only the way in which we behave.” For if our behavior is to be enucleated from our attitudes we must be hopelessly split in two, and the psyche, which is largely spirit, must surely die within us.

That knowledge . . . wherewith ye may be able to hold your thought in leash must, I believe, refer to knowledge which comes from those functions other than thinking. It consists of the knowledge that comes from sensation, from intuition, and from feeling. The knowledge which comes from sensation is the immediate and direct perception which arrives via the senses and has its reality independently of anything that we may think about it. The knowledge which comes from intuition is that which precedes thinking and also which suggests where thinking may go; it is the star which determines the adjustment of the telescope, the hunch which leads to the hypothesis. And finally, the knowledge which comes from feeling is the indisputable evaluative judgment; the thing happens to me in a certain way and incorporates my response to it; I may be drawn toward it or I may recoil from it, I love or I hate, I laugh or I weep, all irrespective of any intervening process of thinking about it.

It is not enough, as some of the currently popular anti-intellectual approaches to psychotherapy would have it, merely to lay aside the intellectual function. The commonly heard cries, “I don’t care what you think about it, I want to know how you feel about it,” are shallow and pointless; they miss the kernel while clinging to the husk. Jo hold your thought in leash, that seems to me the key, for all the knowledge so hard-won in the laboratory and in the field is valuable only in proportion to the way it is directed to the service of consciousness as it addresses itself to the unconscious, to the service of the created as it addresses itself to the creative principle, to the service of human needs as we address ourselves to God.

Jung’s approach to religion is twofold, yet it is not dualistic. First, there is the approach of one person to God and, second, there is the approach of the scientist-psychologist to people’s idea-of-God. The latter is subsumed under the for[1]mer. Jung’s own religious nature pervades all of his writing about religion; even when he writes as a psychotherapist he does not forget that he is a limited human being standing in the shade of the mystery he can never understand.

Nor is he alone in this. Margaret Mead has written, “We need a religious system with science at its very core, in which the traditional opposition between science and religion . . . can again be resolved, but in terms of the future instead of the past ... Such a synthesis . . . would use the recognition that when man permitted himself to become alienated from part of himself, elevating rationality and often narrow purpose above those ancient intuitive properties of the mind that bind him to his biological past, he was in effect cutting himself off from the rest of the natural world.”

[…]

What Jung is attempting to understand and elucidate is, as the student quite correctly supposed, a psychology of religion. Jung puts the religious experience of the individual, which comes about often spontaneously and independently, into place with the religious systems that have been evolved and institutionalized in nearly every society throughout history.

In psychotherapy, the religious dimension of human experience often appears after the analytic process has proceeded to some depth. Initially, people come for help with some more or less specific problem. They may admit to a vague uneasiness that what is ailing may be a matter of personal issues, and that the “symptoms” or “problems” they face could be outcroppings of a deeper reality—the shape of which they do not comprehend. When, in analysis, they come face to face with the figurative representation of the self, they are often stunned and shocked by the recognition that the non-personal power, of which they have only the fuzziest conception, lives and manifests itself in them. Oh, yes, they have heard about this, and read about it, and have heard it preached from intricately carved pulpits, but now it is all different. It is the image in their own dreams, the voice in their own ears, the shivering in the night as the terror of all terrors bears down upon them, and the knowing that it is within them—arising there, finding its voice there, and being received there.

It is not in the least astonishing, [Jung tells us] that numinous experiences should occur in the course of psychological treatment, and that they. may even be expected with some regularity, for they also occur very frequently in exceptional psychic states that are not treated, and may even cause them. They do not belong exclusively to the domain of psychopathology but can be observed in normal people as well. Naturally, modern ignorance of and prejudice against intimate psychic experiences dismiss them as psychic anomalies and put them in psychiatric pigeonholes without making the least attempt to understand them. But that neither gets rid of the fact of the occurrence nor explains it.

[…]

Nor is there any more hope that the God-concept advanced by the various religions is any more demonstrable than that expressed by the individual as “my own idea.” The various expressions that have been given voice about the nature of transcendental reality are so many and diverse that there is no way of knowing absolutely who is right, even if there were a single, simple answer to the question. Therefore, as Jung saw it, the denominational religions long ago recognized that there was no way to defend the exclusivity of their “truth” so, instead, they took the offensive position and pro[1]claimed that their religion was the only true one, and the basis for this, they claimed, was that the truth had been directly revealed by God. “Every theologian speaks simply of ‘God,’ by which he intends it to be understood that his ‘god’ is the God. But one speaks of the paradoxical God of the Old Testament, another of the incarnate God of Love, a third of the God who has a heavenly bride, and so on, and each criticizes the other but never himself.”

[…]

A basic principle of Jung’s approach to religion is that the spiritual element is an organic part of the psyche. It is the source of the search for meaning, and it is that element which lifts us above our concern for merely keeping our species alive by feeding our hunger and protecting ourselves from attack and copulating to preserve the race. We could live well enough on the basis of the instincts alone; the naked ape does not need books or churches. The spiritual element which urges us on the quest for the unknown and the unknowable is the organic part of the psyche, and it is this which is responsible for both science and religion. The spiritual element is expressed in symbols, for symbols are the language of the unconscious. Through consideration of the symbol, much that is problematic or only vaguely understood can become real and vitally effective in our lives.

The symbol attracts, and therefore leads individuals on the way of becoming what they are capable of becoming. That goal is wholeness, which is integration of the parts of the personality into a functioning totality. Here consciousness and the unconscious are united around the symbols of the self. The ways in which the self manifests are numerous beyond any attempt to name or describe them. I choose the mandala symbol as a starting point because its circular characteristics suggest the qualities of the self (the pleroma that hath no qualities). It is “smaller than small and bigger than big.” In principle, the circle must have a center, but that point which we mark as a center is, of necessity, larger than the true center. However much we decrease the central point, the true center is at the center of that, and hence, smaller yet. The circumference is that line around the center which is at all points equidistant from it. But, since we do not know the length of the radius, it may be said of any circle we may imagine, that our mandala is larger than that. The mandala, then, as a symbol of the self, has the qualities of the circle, center and circumference, yet like the self of which it is an image, it has not these qualities.

Is it any wonder then, that the man who was not a man should be chosen as a symbol of the self and worshiped throughout the Christian world? Is it at all strange, when considered symbolically, that the belief arose that an infinite spirit which pervades the universe should have concentrated the omnipotence of his being into a speck so infinitesimal that it could enter the womb of a woman and be born as a divine child?

In his major writings on “Christ as a Symbol of the Self” Jung has stated it explicitly:

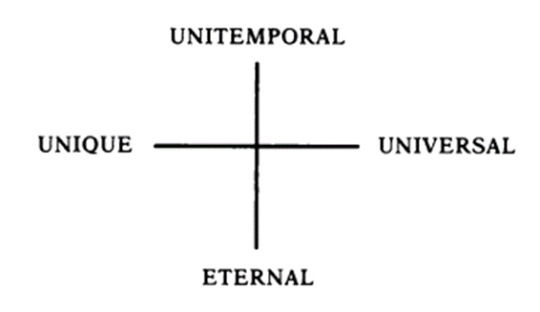

In the world of Christian ideas Christ undoubtedly represents the self. As the apotheosis of individuality, the self has the attributes of uniqueness and of occurring once only in time. But since the psychological self is a transcendent concept, expressing the totality of conscious and unconscious contents, it can only be described in antinomial terms; that is, the above attributes must be supplemented by their opposites if the transcendental situation is to be characterized correctly. We can do this most simply in the form of a quaternion of opposites:

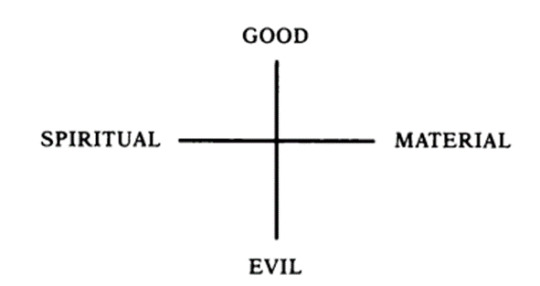

This formula expresses not only the psychological self but also the dogmatic figure of Christ. As an historical personage Christ is unitemporal and unique; as God, universal and eternal... . Now if theology describes Christ as simply “good” and “spiritual,” something “evil” and “material” . . . is bound to arise on the other side . . . The resultant quaternion of opposites is united on the psychological plane by the fact that the self is not deemed exclusively “good” and “spiritual”; consequently its shadow turns out to be much less black. A further result is that the opposites of “good” and “spiritual” need no longer be separated from the whole:

[…]

The pre-form of this insight appeared in the first of the Seven Sermons of the Dead where it is said, “the striving of the creature goeth toward distinctiveness, fighteth against prime[1]val, perilous sameness. This is called the principium individua[1]tionis.”” We are caught in the struggle between the opposites; the stone is fixed and incorruptible. The individuation process is an opus contra naturam,; it is a struggle against the natural, haphazard way of living in which we simply respond first to the demands made upon us by the circumstances of our envi[1]ronment and then to those of inner necessity, paying the most attention to the side that is most insistent at any given time. Individuation leads through the confrontation of the opposites until a gradual integration of the personality comes about, a oneness with oneself, with one’s world, and with the divine presence as it makes itself known to us.

The beginning of the alchemical process parallels the leg[1]ends of creation, the consolidation of a world out of formless chaos. In alchemy the opus starts out with a massa confusa, a teeming, disordered conglomeration of what is called prima materia. It goes through a series of transformations, all described in the most abstruse language, in a lore that predated Christianity and extended forward into the seventeenth century. We seldom get much of an idea of how the work was actually done, what materials were used and what results were achieved. Jung says, “The alchemist is quite aware that he writes obscurely. He admits that he veils his meaning on purpose, but nowhere,—so far as I know—does he say that he cannot write in any other way. He makes a virtue of necessity by maintaining either that mystification is forced on him for one reason or another, or that he really wants to make the truth as plain as possible, but that he cannot proclaim aloud just what the prima materia or the lapis is.” This is in a tradition of refusing to make easily available material that has been acquired only with great difficulty, on the grounds that the quest is at least as important as the goal, or that the importance of the goal rests on the energy and commitment that has been involved in the quest.

Jung cites one of the oldest alchemical tests, written in Arabic style: “This stone is below thee, as to obedience; above thee, as to dominion; therefore from thee, as to knowledge; about thee, as to equals.” He comments on the passage:

[It] is somewhat obscure. Nevertheless, it can be elicited that the stone stands in an undoubted psychic relationship to man: the adept can expect obedience from it, but on the other hand the stone exercises dominion over him. Since the stone is a matter of “knowledge” or “science,” it springs from man. But it is outside him, in his surroundings, among his “equals,” i.e., those of like mind. This description fits the paradoxical situation of the self, as its symbolism shows. It is the smallest of the small, easily overlooked and pushed aside. Indeed, it is in need of help and must be perceived, protected, and as it were built up by the conscious mind, just as if it did not exist at all and were called into being only through man’s care and devotion. As against this, we know from experience that it had long been there and is older than the ego, and that it is actually the spiritus rector (guiding, or controlling spirit) of our fate.

[…]

Ever since Alan Watts exchanged his starched clerical collar for a Japanese silk kimono and found wisdom in insecurity —if not for life everlasting, then long enough to influence a younger generation—Americans have been turned on to the mysterious East. A rediscovery of ancient truth has led many of these people into fads and fantasies inspired by the pilgrims from the Orient, and a smaller number to the serious study of Hinduism, Taoism and Zen Buddhism. In their reading, they often discover that Jung had taken a similar path many years before, and had learned a great deal about Eastern religions and philosophy both through study and through his travels in India. If they have read his essays on Eastern religion in Psychology and Religion they have some feeling for the great respect Jung held for much of the sacred teaching of the Orient. Also, they will have some understanding of his views on the potential effects of certain traditional Eastern ways of thinking upon the Western mind. All too frequently, however, Jung’s writings have been misunderstood or only partially understood. His interest in Eastern religious thought and certain practices associated with it—like his interest in séances, in alchemy, or in astrology—have been incorrectly construed as a wholehearted and literal endorsement for use by Westerners today.