#Adultification

Text

Adultification of all HotD Girls and the infantilization of Rhaenyra.

Two scenes in HotD really bug me with how the characters acknowledge Rhaenyra as a child when she’s 18, but then go on to marry and impregnate girls younger than 18.

Viserys call Rhaenyra, “just a girl” when Daemon takes her to the brothel. He doesn’t use the world woman, he uses girl, denoting Rhaenyra as not an adult at this point in her life. By Visery’s logic, he married a child. Alicent was only 14/15 when he married her and only 17 when she become a mother twice over.

Daemon also cause Rhaenyra, “just a child” when she’s says he abandoned her after her wedding. Daemon then goes on to flirt with a 15/16 year old Laena at the wedding and marrying her soon after.

The adultification of Laena is much worse than characters in text acknowledging people older than her as kids. Laena is played by two actresses that are about ten years older than Laena’s canon age. This also isn’t just a case of adults playing teens, the show has set Rhaenyra and Alicent as the standard for what a 14 through 18/19 year old and 28 through 34 year olds looks like. Laena’s actresses are older than Rhaenyra and Alicent’s Actors and Actresses. This is a classic example of black girlhood being earesed in text and out of. Laena goes from a clear 12 year old who is very visually much younger than Rhaenyra and Alicent to being a near adult woman who looks about the same age, if not older than the other girls. Laena is also styled in much more mature clothing than we see any other character in. Even Alicent’s “sex dresses” are much more reserved than Laena’s gold dress.

We also have the same thing happening to Laena’s daughters, Baela and Rhaena. In text they should be 16 or younger but their actresses are older than Jace’s actor. The only upside is that the two are not visually sexualized and aged up as teen Laena was.

In conclusion, HotD in text shows the absurdity of Viserys and Daemon viewing Rhaenyra as a child while pressing girls younger than she was at the time. The show tries to erase the clear adultification of Laena. The show engages in a lot of anti black stereotypes and I am not looking forward to how they’ll treat Nettles.

Disclaimer: I am not a WOC or a POC, if anything I wrote is wrong please correct me. My goal is to learn and advocate for better representation in media for all gender, races, ethnicities, and sexual orientation.

Blogs I recommend you follow if you want to read more about how HotD fails women and people of color: @bohemian-nights @venusintheblindspots-blog @mejcinta @sunnysideaeggs

#house of the dragon#hotd#hotd discussion#HotD analysis#HotD racism#hotd critical#adultification#Adiltification of black girls#laena velaryon#Alicent Hightower#Rhaenyra Targaryen#anti viserys i targaryen#anti daemon targaryen#Baela Targaryen#rhaena targaryen

353 notes

·

View notes

Text

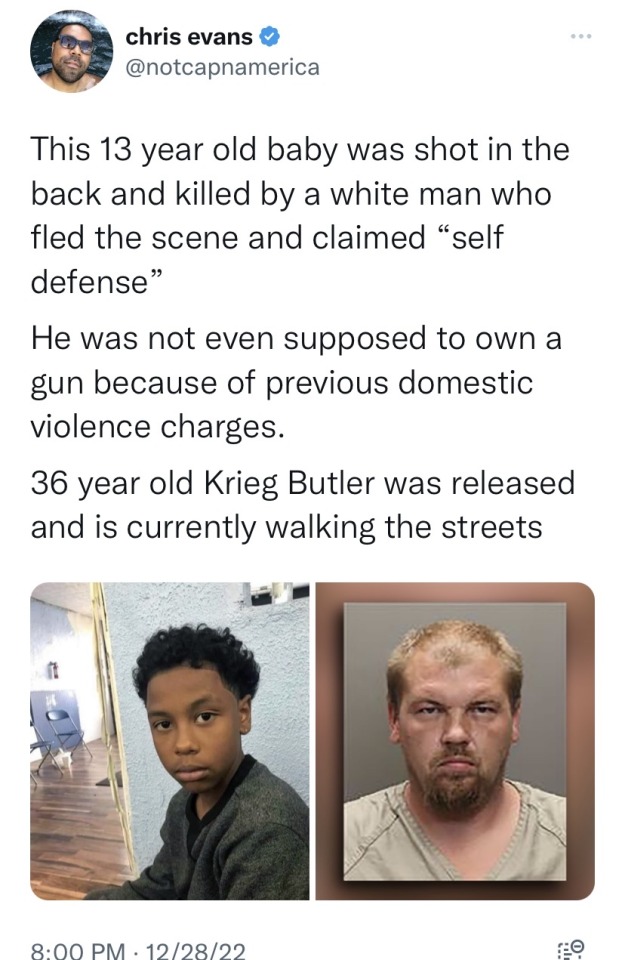

youtube

#sinzae Reed#justice for sinzae Reed#preview commentary#protect black children#say their names#adultification#adultification of black children#social media commentary#extended version on FanBase#full commentary on YouTube

865 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm gonna get this off of my chest and then probably be done with this discourse but it's basically just what I feel and some shit about the adultification of black males and black people in general, my rant is below the cut

I have cousins and a younger brother who are teens and look similar to Hobie ie being darker skinned and tall, my younger brother even has some of Hobie's characteristics which I have seen shine when he's with his friend, moments that are similar to the when Hobie dapped Pav up and called him "Big Steppa !" which is why I don't see his characteristics as "adult" or get "adult vibes" because my brother and many of his friends who are black teens look like and have similar characteristic to Hobie's, My brother who has darker skin, hair although not in wicks, is wild and similar to Hobie's because he grows it long and blows it out and it takes similar shape, is tall, has a deep as voice that actually startles people when they hear it, has had a major dislike towards authority figures like cops and people in charge in general and would do absolutely anything to protect his friends.

I've seen many black teens, mostly friends and family in Hobie Brown although they aren't punk like he is, kids I've literally watched grow up

And I bet if Miles didn't have his age explicitly stated and they didn't show him going to school, people would try to claim that he's older than he actually is

And although this might be unethical to rope in horrifying situations that actually happen with a stupid discourse about a fictional character in a superhero movie but it reminds me about how black people in general are always labeled as "adults" when something bad happens with them because as soon as we hit a growth spurt and start to look threatening, we're no longer kids to them. It's suddenly "Black man arrested by police" and that "man" is a 16 year old or "Black woman shot and killed" and that "woman" was only 17 and still in school, hell I've seen articles with label these black kids as "men" and "women" when they were only 12 or 13.

That's all I've gotta say on the matter. And if you see Hobie as over 18 ? Fine, whatever, I don't care as long as you're not constantly commenting on people's ship art or posts or on the posts of those who use his confirmed comic age as their interpretation, harassing people with "he's a grown man !!!!" with no proof to back up your claims except for and edited clip that was taken out of context some dickweed on TikTok posted

And the adultification is even affecting a black female character too because people are claiming that those who ship Margo and Miles are pro shippers and claiming that Margo is an adult woman

And don't get me started on the people who just desperately want Hobie to be a grown man so they can justify sexualizing him and thirsting over him because that is a whole different form of adultification of black men that I am way too tired to get into

But I hope this is the last thing I'm gonna say on this stupid ass discourse

#spiderman across the spiderverse#spider man across the spider verse#spider man: across the spider verse#across the spiderverse#atsv#spider man atsv#hobie brown#miles morales#margo kess#antiblackness#fandom racism#racism#fandom critical#fandom discourse#rant#adultification

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

At age 17, Donnell Drinks was one of many young men in Philadelphia who went to prison for life without parole. Today, the city has resentenced more of those prisoners than any other jurisdiction.

Published Aug. 15, 2023Updated Aug. 18, 2023

Donnell Drinks woke up one morning to banging on his door in the projects of North Philadelphia. It was the late 1980s, and Mr. Drinks, who was 15 and the oldest of three boys, had nodded off after taking his youngest brother to school. He should have been at school himself, but he had stopped going earlier that year. It wasn’t a truant officer at his door, though — no one had ever come knocking about that. Instead, sheriff’s deputies were waiting outside. They were there to evict his family.

The officers told him to get out, not bothering to ask if there was an adult around, which there wasn’t. Mr. Drinks’s dad had abandoned the family a decade earlier, and his mom was in the throes of crack cocaine addiction. For years, Mr. Drinks had been raising his younger brothers, and he had just become a father himself. He’d dropped out of school to support his family by selling drugs, a transition that felt so natural he hardly remembered how it happened.

Groggy and panicked, Mr. Drinks scanned the apartment for essentials, stuffed a shopping cart with clothes for his brothers and wheeled the cart up the road to his grandmother’s overcrowded rowhouse. The officers never asked where he was going.

“There was not one adult that said, Hold a minute. We need to call somebody,” Mr. Drinks said. “Not one adult said, That’s a child.”

At the time, Black teenage boys like Mr. Drinks were being treated less as children in need of help and more as if they were threats to society itself. Crime was rising nationwide, particularly in Philadelphia, where, in 1990, the city recorded 500 murders in a year for the first time. It was a terrifying period, especially for people living in poorer neighborhoods where the violence was worst. But the rhetoric, perpetuated by public officials and overheated headlines, suggested that a new morally depraved generation of teenagers — particularly Black teenagers — were to blame. This idea gave rise to the “superpredator” era and a raft of laws cracking down on juveniles that followed.

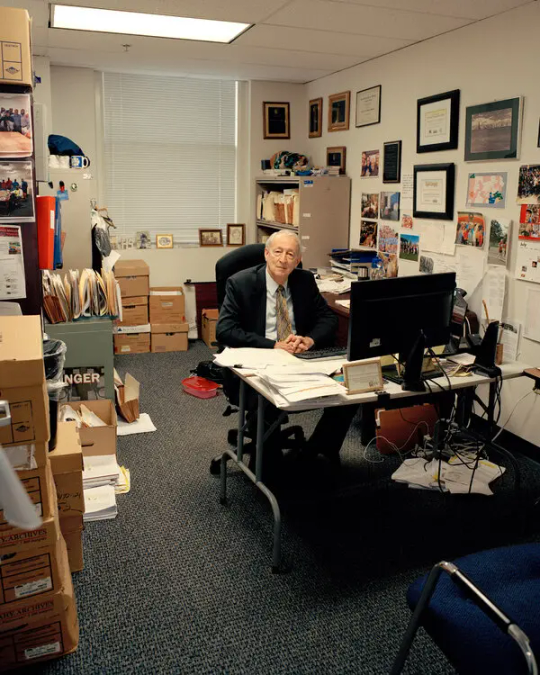

Mr. Drinks, now 50 years old, is a small man with a stocky frame and a warm, gaptoothed smile. He keeps his salt-and-pepper beard meticulously fluffed. An animated storyteller who is quick with a metaphor and a motivational quote, he becomes guarded when describing his upbringing — not just because it’s painful, but because he doesn’t want anyone to think he’s trying to justify what happened next. “This is context,” he said, “not excuses.”

In February 1991, when he was 17, Mr. Drinks and his 22-year-old girlfriend, who was a police officer, tried to rob a man named Darryl Huntley. They staked out Mr. Huntley’s house and forced him and his fiancée inside at gunpoint. That violent act led to others. Mr. Drinks stabbed Mr. Huntley, fatally, and was shot himself. Mr. Drinks was arrested while he was in the hospital recovering from his injuries.

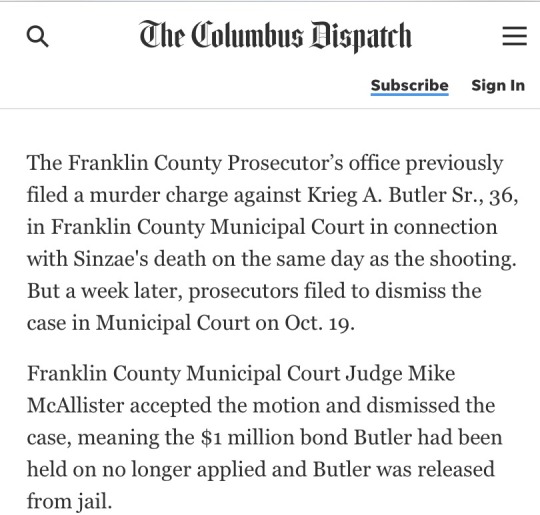

By the time Mr. Drinks was brought to trial for Mr. Huntley’s murder, Philadelphia had a new district attorney: Lynne Abraham, a former judge who went on to hold the office for nearly two decades. Pennsylvania law already made life sentences mandatory for first- and second-degree murder convictions, but Ms. Abraham responded to the era’s surge in violent crime by aggressively pursuing the death penalty, an approach that once earned her the moniker the “deadliest D.A.”

She also called for tougher punishments for juveniles. In 1994, she pushed for legislative changes to give prosecutors more power to charge juveniles as adults. “You don’t get any bonus for being under a certain age,” she told The Philadelphia Inquirer at the time. The next year, the state passed a law that required prosecutors to treat children 15 and older as adults when they were charged with certain crimes.

Though Philadelphia had already sentenced many young people to life without parole, under Ms. Abraham’s watch — and with the city’s murder rate remaining high throughout the ‘90s — the number getting that sentence in Philadelphia rose quickly. For some, it may have been a deal worth taking to avoid the death penalty.

Mr. Drinks was tried as an adult and initially sentenced to death. In 1993, his sentence was reduced to life without parole. (His then-girlfriend, who received the same sentence, remains in prison.)

He most likely would have died in prison, but while Mr. Drinks was behind bars, a national effort began to rethink the culpability of young people in the eyes of the law. In the 2005 case Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court struck down the death penalty for minors, leaning heavily on new scientific research that showed — “as any parent knows,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote — that young people are not like adults. They are more impulsive, reckless and susceptible to persuasion.

The court did not question that minors should pay for committing heinous crimes, but in banning the most severe punishment, it affirmed the possibility “that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.” Real change, Justice Kennedy suggested, was possible.

Mr. Drinks had been in prison for more than a decade when the Roper decision came out. Then one day, a Philadelphia lawyer named Bradley Bridge traveled to the upstate Pennsylvania prison where Mr. Drinks was locked up, and explained to him and the other men who had been given life sentences as boys what the ruling could mean for them.

Striking down the death penalty for minors was only the beginning, Mr. Bridge said. Soon, he predicted, the court would apply the same logic to outlaw mandatory life sentences for juveniles too, potentially giving Mr. Drinks and others serving such sentences a shot at freedom — and giving the city of Philadelphia a chance to rewrite its legacy.

A long list of friends

Mr. Bridge had been delivering his speech inside prisons throughout Pennsylvania for months before Mr. Drinks heard him speak. Mr. Bridge worked for the Defender Association of Philadelphia and had spent nearly three decades representing prisoners who were appealing their sentences. When the Roper ruling came down, he was involved in the case of a teenager facing a mandatory sentence of life without parole. He understood immediately the opportunity that the Supreme Court’s ruling presented not just for his client, but for scores of prisoners.

For Mr. Bridge, it meant pursuing a novel legal theory that might help dismantle what he viewed as a particularly unjust part of the justice system. “Children are children, and they make mistakes,” Mr. Bridge said. “But they grow and change.”

Mr. Bridge began the enormous undertaking of compiling a list of all the prisoners in Pennsylvania who were sentenced to life as minors. No one in the state had ever kept track of this group, who came to be called “juvenile lifers” in the courts and “child lifers” by some of the inmates themselves.

He expected the list to be long. He didn’t expect it to eventually include more than 500 names, nearly one-fifth of the more than 2,800 child lifers in the country. More than 300 of them had come through Philadelphia’s system, making a city with less than 1 percent of the country’s population responsible for more than 10 percent of all children sentenced to life in prison without parole in the United States. No other city compared. Even more glaring: More than 80 percent of Philadelphia’s child lifers were Black. Nationally, that figure was roughly 60 percent.

Racism “undoubtedly occurred in every phase of the criminal justice system,” Mr. Bridge said. “This created an opportunity to try to fix things that had been broken.”

After the Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for minors, Bradley Bridge started encouraging inmates sentenced to life as children to prepare for the possibility that the court would eventually revisit the constitutionality of their sentences, too.

His partner in this work was Marsha Levick, who had co-founded the Juvenile Law Center in 1975 as an idealistic young graduate of Temple University’s law school and gone on to become one of the nation’s foremost experts on juvenile sentencing.

Mr. Bridge and Ms. Levick began traveling the state, arranging meetings with the people on Mr. Bridge’s list and adding names as they went. Mr. Bridge’s first stop was Graterford, a maximum-security facility outside of Philadelphia that, at the time, held more child lifers than any prison in the state. Dozens of men crowded into Graterford’s chapel to hear what Mr. Bridge had to say.

“People wanted to know what was coming down the pike,” remembered Kempis “Ghani” Songster, who was in the room that day. “Is this a ray of light flickering on?”

At age 15, Mr. Songster stabbed another teenager to death in a crack house. Both were runaways working for the same gang. He was given a life sentence for his crime, but it wasn’t until that meeting in 2006, nearly two decades after he went to prison as a scrawny kid who couldn’t grow a beard, that he realized how many other lifers at Graterford had also arrived as teenagers.

“It was like, Whoa, he’s been here since he was a kid, too?” Mr. Songster said. “A lot of us who were child lifers didn’t really know that we were in a distinct class.”

There had never been a reason to talk about age. The courts had treated them as adults, and if anything, being marked as a child in a violent adult prison would only have made them more vulnerable. Now, there was power in the identity.

The child lifers inside Graterford began organizing. They quickly formed a committee called Juvenile Lifers for Justice, which met weekly to discuss the evolving law and science around adolescent development. They drafted pamphlets, circulated newsletters to other prisons and their family members, and kept one another motivated around their common cause.

These conversations also started to change how some of the men thought about why they had committed such serious crimes.

Mr. Songster said he never felt “entitled” to be free. “I can’t wash the blood off my hands that’s on my hands,” he said. But the emerging research, which showed brains aren’t fully developed until people get into their 20s, gave him new understanding. “It made me curious about myself,” Mr. Songster said of the research. “I knew I was a good person, but I couldn’t reconcile the person that I became and I know I am with the person that committed that horrible act.”

The child lifers were also reaching out beyond the prison walls. They invited politicians to visit Graterford and partnered with nonprofit organizations to distribute supplies to local schools.

“We were always trying to break that wall down so people could see we’re humans,” said Don Jones, who was also sentenced as a minor and was the president of Graterford’s N.A.A.C.P. chapter during this period.

Mr. Bridge and Ms. Levick became frequent fixtures at the prison. At each of these visits, Ms. Levick was struck by how the men — imprisoned at such a young age and last in line for any prison edification programs because of their status as lifers — had mastered the nuances of the law and were orchestrating a statewide grass-roots movement from inside prison. “Their desire to come home was real,” Ms. Levick said. “It was palpable, and it made you want to do more.”

“We were always trying to break that wall down so people could see we’re humans,” said Don Jones, who was locked up at Graterford and has since been released.

Mr. Drinks had spent 10 years at Graterford, but after he was transferred upstate, newsletters coming out of Graterford and messages passed along from old friends became his lifeline. Without a lawyer of his own, he kept his case alive by adapting draft legal petitions circulated by Mr. Bridge. And he documented his accomplishments in prison — articles he’d written, certificates he’d earned, thank-you notes from the nonprofits he’d raised money for — until he had three manila envelopes’ worth of records illustrating all the ways he’d grown.

Still, he never quite let himself believe that Mr. Bridge’s prediction would pan out. He wanted to be prepared, but he was also prepared to be let down.

“It’s like throwing water out of a boat that’s sinking,” Mr. Drinks said. “You’ve got to do it anyway, because if you don’t, the water’s going to get you.”

Throughout this period, lawyers around the country, including Ms. Levick and Mr. Bridge, were bringing new cases, trying to apply the rationale in the Roper ruling to other kinds of sentences for juveniles. At the national level, a key leader in this work was Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit.

Mr. Stevenson saw a connection between the superpredator era and the overwhelming number of young Black boys who had been locked away for life.

“You had these criminologists going around saying that some children aren’t children. Some kids look like kids, but they’re really, quote, superpredators,” he said. “That narrative was so prevalent, so persuasive, that you see states all over the country lowering the minimum age for trying children as adults.”

In 2008, the Equal Justice Initiative found 73 children who had been given sentences of life without parole when they were 13 and 14 years old. And all of the people who received those sentences for crimes other than homicide were children of color.

“It just said something about the way in which race was a proxy for a presumption of dangerousness, this presumption of irredeemability,” Mr. Stevenson said.

Then came a series of breakthroughs. In 2010, the Supreme Court abolished sentences of life without parole for minors charged with crimes other than murder. Two years after that, Mr. Stevenson appeared before the court on behalf of two young men who were sentenced to life without parole when they were 14. In its decision in Miller v. Alabama, the Supreme Court struck down all mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles. Four years later, in a case called Montgomery v. Louisiana, for which Ms. Levick served as co-counsel, the court made that decision retroactive, fulfilling the prediction Mr. Bridge made in the Graterford chapel a decade before, and giving more than 2,800 child lifers across the country the right to have their sentences revisited.

Mr. Drinks remembers the first time he got a look at Mr. Bridge’s list. It was filled with the names of people he’d known for years, but had never known were child lifers. There was Abd’Allah Lateef, the soft-spoken guy he’d always admired at Graterford, even when he griped about Mr. Drinks’s loud music. There was Luis “Suave” Gonzalez, a big talker whom Mr. Drinks had encouraged to lead one of Graterford’s Latin American cultural exchange groups. And there was Don Jones, a friend so close, Mr. Drinks said, “my brothers call him brother.”

“That was my tear-shed moment,” Mr. Drinks said. “I knew I was on the list, but going down the list and seeing genuine friends?” Now, they might all have a shot at freedom — a shot, but not a guarantee.

A block in North Philadelphia. Donnell Drinks sold drugs in the area as a teenager and was convicted of homicide at age 17 in a robbery gone wrong.

‘The election changed everything’

The Supreme Court’s rulings in Millerand Montgomery marked an important rethinking of culpability when it comes to children who commit the most serious crimes. But the practical implications of the rulings were limited: the court hadn’t abolished all life without parole sentences for children — only ones where state laws made the sentences mandatory.And while child lifers now had a chance to make a case for their release, prosecutors could still seek new life sentences. In other states with high numbers of child lifers, including Michigan and Louisiana, as well as some parts of Pennsylvania, that’s just what they did.

In Philadelphia, however, all of the list-gathering and planning that had been taking place for more than a decade began to pay off. Most of the state’s child lifers had been prosecuted in the city, and it was up to its district attorney’s office and court system to move hundreds of people through the resentencing process. “Philadelphia was bad, and everybody recognized it was bad,” Mr. Bridge said.

Ms. Levick added, “In a way, the whole world was watching.”

Philadelphia soon began resentencing and releasing child lifers, starting with those who’d been in prison the longest. But while R. Seth Williams, Philadelphia’s district attorney, initially committed not to resentence anyone to life without parole, he stuck to strict new state sentencing guidelines, which meant that Mr. Drinks and others who had been swept up in the ’90s, would most likely spend many more years in prison.

Marsha Levick, an expert on juvenile sentencing, visited inmates. “Their desire to come home was real,” Ms. Levick said. “It was palpable, and it made you want to do more.”

Mr. Williams viewed this approach as the only way to honor the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Pennsylvania government’s consensus and the rights of the victims. “People often only look at the factors for the defendant. I understand. But they often forget there was a victim,” Mr. Williams said. “Someone was murdered. We just can’t just sweep that under the rug.”

Then came a twist that no one predicted. In March 2017, a little over a year after the Montgomery decision, Mr. Williams was indicted on charges including bribery and extortion and later sentenced to five years in prison. Almost as surprising was who was elected to be his successor: a sharp-elbowed former public defender and criminal defense attorney named Larry Krasner.

Whatever Ms. Abraham, the former district attorney, had been to the city in the 1990s, Mr. Krasner swore to be the opposite. (Ms. Abraham did not respond to requests for comment.) He had run against the death penalty and mass incarceration, and vowed to decriminalize marijuana and end cash bail. One of his first moves after taking office in January 2018 was to fire 31 prosecutors in a purge that became known as the Snow Day Massacre.

When it came to juvenile lifers, Mr. Krasner was more open than his predecessor to considering how people had changed in the decades since committing their crimes. Chesley Lightsey is a former assistant district attorney who worked on Mr. Drinks’s case and others under both administrations. “It took time for me to wrap my head around it: ‘Okay, now we can have much more of a conversation about this,’” she said about the change when Krasner was elected. “It was just a different perspective.”

Under Mr. Krasner, prosecutors paid special attention to reports drafted by mitigation specialists. Those specialists, who are essentially professional storytellers for defendants, interviewed juvenile lifers, their families and anyone else who could offer context. They asked questions about how the inmates had been raised, the trauma and pain that had influenced their actions, what they had done with their time in prison and what they planned to do upon release.

By the time Mr. Krasner took office in January 2018, Mr. Drinks had spent hours spilling his soul to a lawyer and mitigator named Rachel Miller. Over the course of countless calls and several in-person visits, Ms. Miller wove the story of Mr. Drinks’s life into a memo, complete with a two-inch stack of documents highlighting his accomplishments.

The memo covers the most painful moments of Mr. Drinks’s childhood: being abandoned by his father, his mother’s struggle with addiction, getting evicted. It describes how Mr. Drinks would skip school to collect the family’s food stamps before his mother could pawn them for drugs and how, when his mother turned violent, he would take the brunt of her beatings in an attempt to spare his brothers.

But the memo also tells the story of a grown man who spent his time behind bars trying to atone for the crime that put him there. Among the stack of documents is a community college transcript filled with A’s and B’s, an agenda for a workshop he organized with victims’ rights advocates and a photo of him beaming behind a giant check made out to Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. Perhaps most meaningful to Mr. Drinks were the letters he received from other incarcerated men who were members of a youth group he founded attesting to all the ways the group, and Mr. Drinks, had saved them. “I did not know the child that committed the crime he is in here for,” read one of the letters, “but the man I do know is not that same person.”

Before Mr. Krasner’s election, Mr. Drinks was offered a deal of 35 years to life, which would have made him eligible for parole in 2026. Shortly after Mr. Krasner took over in 2018, Mr. Drinks got a new offer: time served.

“The election changed everything,” Mr. Drinks said, referring to Mr. Krasner’s victory.

“I’m always conscious of the emotion, the hurt, the disappointment, the disdain, all those negative emotions that my actions led to,” Mr. Drinks said of the murder he committed. “I’ve got to live the rest of my life counteracting that.”

Mr. Drinks’s case was not unique. Researchers at Montclair State University have found that, under Mr. Krasner, prosecutors began offering child lifers new sentences that were, on average, 11 years shorter than the ones offered to those same people under Mr. Williams. Crucially, the researchers found that child lifers’ release had a negligible effect on public safety. Seven years after they started coming home, the rearrest rate for Philadelphia’s child lifers hovers around 5 percent. That’s small compared with the national rate, where 40 percent of people with past murder convictions are rearrested within the first five years, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. As of early this year, only three of the city’s child lifers who were rearrested have been convicted (for marijuana possession, contempt and robbery in the third degree), according to the Montclair State researchers.

For Mr. Krasner, these numbers reveal as a lie the idea that some people are so incapable of change that they should never be offered a shot at it. “It was always wrong to believe that people are either saints or they’re sinners,” Mr. Krasner said.

At his resentencing hearing in April 2018, Mr. Drinks read aloud from a letter before a gallery filled with friends and family, as well as the loved ones of Mr. Huntley, his victim. He apologized to Mr. Huntley’s family and said he knew he had no right to ask anyone in the room for forgiveness, and so he didn’t. But he did promise to spend the rest of his life making amends.

Mr. Huntley’s family members also made statements to the court. In a handwritten letter, Mr. Huntley’s sister described her brother as a loving and giving person. She explained how his murder had crushed her family, derailed her own education and deprived her children of ever knowing their uncle. “My mother still is deeply hurt and our family find it difficult to celebrate Valentine’s Day,” she wrote, “because these horrible, horrible actions took place that evening leading into his death.” She told the court that she did not want to see Mr. Drinks released.

Mr. Huntley’s sister did not respond to an interview request, but Suzanne Estrella, who runs the Office of Victim Advocate in Pennsylvania, said that many victims’ families “flat-out just do not” agree with the resentencings. But she said there were also many families that understood and accepted them. “You have survivors who have lost loved ones and survivors who have loved ones who are incarcerated,” Ms. Estrella said. “So you see all those perspectives coming to the table at the same time.”

As painful as it was, Mr. Drinks said he appreciated Mr. Huntley’s family’s honesty. “I felt it, and I understood it,” he said. “I’m always conscious of the emotion, the hurt, the disappointment, the disdain, all those negative emotions that my actions led to. I’ve got to live the rest of my life counteracting that.”

Three months after the hearing, having won the approval of the parole board, Mr. Drinks met his brothers as he walked out of prison for the first time in nearly three decades. Mr. Drinks remembers his sense of disbelief and being a little carsick as they drove the four hours back to Philadelphia, where he would move in with his brother Damon. The whole way home, he couldn’t shake the feeling that someone was following close behind. “I didn’t want to look back,” he said, “so I kept looking ahead.”

Donnell Drinks married Shekia Drinks two years ago. But he hasn’t been able to get the approval needed to move out of his brother’s home and in with his wife.

A return to the 1990s?

Of the more than 300 child lifers who became eligible for resentencing in Philadelphia in 2016, all but about a dozen have been resentenced, and more than 220 have been released, the majority of them on lifetime parole. That’s nearly a quarter of the roughly 1,000 total child lifers who have been released across the country. These numbers make Philadelphia, once an outlier in imprisoning minors for life, now an outlier in letting them go. By 2020, the city had resentenced more child lifers than Michigan and Louisiana combined.

What set the city apart, said Mr. Stevenson, of the Equal Justice Initiative, was not just the buy-in from local officials and public defenders, but also the community of child lifers who became their own best argument for release.

“It was the way they organized, the way they cared for one another, the way they modeled a kind of readiness to contribute to society,” Mr. Stevenson said. “These young people had been told they were going to die in prison. Some of them just never accepted that.”

Since the Supreme Court decisions, more than half of all states have outlawed life without parole sentences for children altogether, reducing the number of child lifers left in the country to fewer than 600, according to the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a national nonprofit. Mr. Stevenson’s organization is now working to raise the minimum age at which children can be tried as adults in 11 states, including Pennsylvania, where there is no age floor. Other states are considering abolishing mandatory life without parole sentences for people under 21.

While life without the possibility of parole sentences for juveniles are now rare, they are not unheard of. The now solidly conservative Supreme Court has issued a ruling that could lower the bar for judges to apply the sentence to children in states where it is still allowed. A prosecutor in Oakland County, Mich., is seeking life without parole for a mass shooter who was 15 when he killed four students at his high school in 2021. A judge will have to weigh the horror of his crime against the possibility that, over time, he could change.

The United States is still the only country in the world that gives courts the discretion to send children to prison without the chance of proving themselves later in life at a parole hearing. And the tough-on-crime rhetoric of the 1990s is making a comeback, thanks to a spike in violent crime that began at the outset of the pandemic. In Philadelphia alone, the murder rate has surpassed the record set in 1990 two years in a row, with young people emerging as both victims and perpetrators.

Mr. Drinks and Mr. Jones started an anti-violence group in Philadelphia and sometimes walk the streets handing out pamphlets.

Just as they did in prison, child lifers have come together to create a buffer against an outside world that often feels hostile and unwelcoming.

Though this uptick in crime is showing signs of decline, it has prompted a nationwide backlash against progressive prosecutors, including Mr. Krasner, whose comparatively lenient approach has become a lightning rod in local politics. Mr. Krasner was recently the subject of an impeachment effort by Pennsylvania Republicans, and even some Democrats raced to condemn his record during the city’s mayoral primary in May.

Those who were released have become some of the loudest voices for building upon the fragile gains they fought for while on the inside. Their fight now is about abolishing life without parole for everyone, getting young people out of adult prisons and addressing the underlying causes of the violence plaguing Philadelphia and other major cities.

“If you would have dealt with a lot of my issues,” Mr. Drinks said, “they probably would not have escalated to crime.”

It’s not that Mr. Drinks and his fellow activists believe juveniles convicted of murder should not be held accountable. “When we talk to legislators, we don’t say: Throw the doors open, and everybody’s coming home,” Mr. Drinks said. “Our conversation is always that everybody deserves an opportunity to show they’re worthy of coming home.”

Today, Mr. Drinks coordinates a network of former child lifers through the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. In any given week, he might be found with two cellphones in hand, flying to Alabama to urge progressive prosecutors to stay the course, organizing retreats for formerly incarcerated men and women, or canvassing city streets through an anti-violence nonprofit he co-founded with Mr. Jones, his friend from Graterford.

Mr. Drinks and other child lifers know that they embody for the public what all the research said about a young person’s capacity for change, and they are keenly aware that their example could help secure other people’s freedom. But they are also wary of being used to suggest that the system works, or allowing it to conceal just how difficult their re-entry into the outside world has been.

While several of Philadelphia’s child lifers have gone on to become an Ivy League lecturer or nonprofit executive, many more are working minimum-wage jobs or are unable to find work. Some are in bad health. Four have died. Nearly all of them are on lifetime parole, with the possibility of being sent back to prison forever looming.

Mr. Drinks credits his brothers, Damon and Kareem, for making his homecoming easier. Throughout Mr. Drinks’s incarceration, the three brothers had remained as close as the prison system would allow, keeping up visits even when he was transferred far away. Often, Damon Drinks would bring along Mr. Drinks’s son, who was just 3 when his father was arrested, and is now a grown man with a family of his own. It is thanks to his brothers, Mr. Drinks says, that he was able to maintain a relationship with his son at all.

Mr. Drinks, in Fairmount Park, said his brothers visited him while he was in prison and have helped him readjust to life on the outside.

Damon and Kareem Drinks’s support continued once their big brother was released. They took him shopping, kept him housed and partnered with him to start a local printing company not far from the city courthouse. Mr. Drinks has not had to struggle to survive, but that doesn’t mean he has not struggled. Five years after he left prison, the terms of his parole still prohibit him from leaving the county of Philadelphia without permission. He got married two years ago, but he has yet to get the approval needed to move out of his brother’s home and in with his wife. And he lives with the constant fear that one act of violence by any of the state’s other child lifers could spell the end of his own tenuous freedom.

This fear is part of what keeps Mr. Drinks connected to the men who were once boys with him on the inside. Just as they did in prison, child lifers have come together to create a buffer against an outside world that often feels hostile and unwelcoming. These bonds are as much a product of their shared experiences as they are a defense against their shared vulnerabilities.

“We’re each other’s co-defendants,” Mr. Drinks said. “We see people want to stray, it’s like, No, come on. We’re going to get to this finish line together.”

Mr. Drinks hugs Michael “Smokey” Wilson, another former child lifer.

#How People Sentenced to Life in Prison Made Their Case for Release#prison#american injustice system.#penal injustice#sentencing disparities#adultification#Black Lives Matter

65 notes

·

View notes

Photo

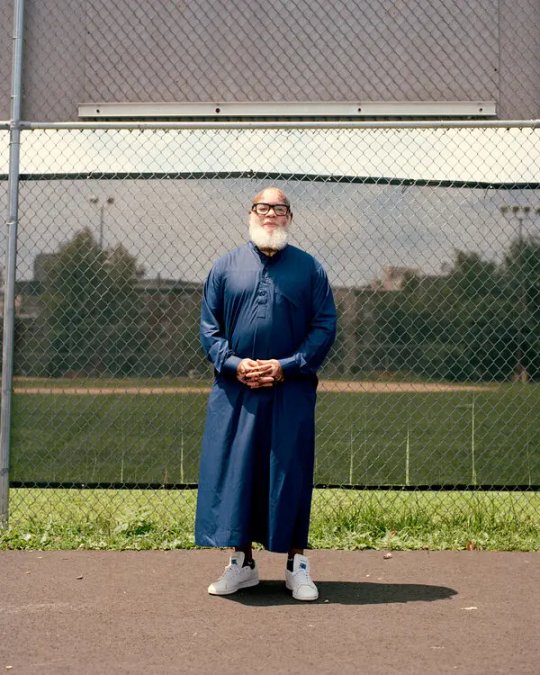

Have you heard of “adultification bias?” The term refers to the reality that, in the United States, Black youth are often treated as adults, enduring heightened surveillance, punishment, and violence. For Black girls, living at the intersection of race and gender oppression makes them particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse.

In “Consecration to Mary,” shown here, Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter (@isisthasaviour) intervenes in an egregious act of adultification, inserting herself as a protective presence into a historical artifact. Shielding a young Black girl from predatory gazes, Baxter indicts both the photographer Thomas Eakins and the legacies of photography, which have been historically weaponized in the oppression of Black people. Presenting a selection of opened and closed daguerreotype cases, Baxter leaves visible three photographs. In two, the artist shifts the critical narrative to the lived experience of the subject in Eakins’ 1882 images. The third photograph—a school-age portrait of the artist herself—links Baxter’s own experiences with these histories of societal abuse. As part of the exhibition Ain’t I a Woman, this photo series complicates our understanding of the prison system by showing that the root causes of incarceration are inextricably tied to the systematic oppression in our public and personal histories.

Experience this multipart photographic work as well as Baxter’s rap documentary Ain’t I a Woman, up through August 13.

🔗 https://bit.ly/AintIAWomanBkM

📷 Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter, Consecration to Mary, 2021. Giclée print on metallic paper in a tintype frame. © Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter → Installation view, Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter: “Ain’t I a Woman,” on view January 20 - August 13, 2023, 2023. Brooklyn Museum (Danny Perez).

#Brooklyn Museum#brooklyn#museum#art#photography#Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter#Ain't I a Woman#rap#documentary#New York City#philadelphia#mass incarceration#adultification#thomas eakins

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Eshu, what do you mean when you talk about ATLA fandom's adultification of girls of color?"

The post I responded to is a textbook example of the adultification of girls of color. You can't get a more perfect example.

Azula, aged 14 on the show and 15 in the comics, is "a grown woman."

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a looooong history that weaves colonial violence and the adultification of brown children into a tapestry of apartheid (and white supremacy)

#our world#ecosystem of white supremacy#padawan historian#free palestine#free us all#let gaza free you#Israel is an apartheid state#ceasefire#adultification

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fact that as you're leaving the police station in ep 5 there's a radio broadcast referring to Daniel as a "teenager" is one of many, many reasons that nobody should feel a smidgen of guilt over the Blood Brothers ending.

#the way this game deals with how america violently ages up children of color fucks up me so bad#like sean gets a shit ton of it every single episode but daniel hasn't been spared since the beginning#their childhood is being stripped away no matter what they do they should at least be able to stay together#lis verse#life is strange 2#blood brothers#daniel diaz#sean diaz#ep 5 wolves#monsters talks life is strange#adultification#adultification in media

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It seems the mother of a Mississippi boy arrested for peeing in public is putting her foot down in the case against him. The boy was recently handed a probation sentence but after viewing the terms and conditions, but his mother said she isn’t signing off on anything.

Latonya Eason’s son Quantavious was apprehended by a Senatobia police officer in August after the boy was seen urinating near his mother’s car in a parking lot, police said. Eason said she was handling business inside an attorney’s office and left her son in the car during the meeting. But after not being able to locate a restroom, she said he resorted to urinating outside.

Tate County Youth Court Judge Rusty Harlow sentenced the 10-year-old to three months of probation and ordered him to complete a two-page book report on the late Kobe Bryant, per NBC’s report. Why? No idea.

Additionally, Quantavious has an 8 p.m. curfew as if a 10-year-old has places to be after that time. He was also prohibited from the use of weapons and ordered to submit drug tests at the probation officer’s discretion, according to family attorney Carlos Moore.

“It’s just a regular probation. I thought it was something informed for a juvenile. But it’s the same terms an adult criminal would have,” Moore said via NBC.

Read more from NBC News:

Latonya Eason, the mother of Quantavious Eason, had initially planned on signing the agreement to avoid the risk of prosecutors upgrading her son’s charge, as they threatened, but she changed her mind after reading the full agreement Tuesday, attorney Carlos Moore said.

The prosecution threatened to upgrade the charge of “child in need of supervision” to a more serious charge of disorderly conduct if the Quantavious’ family took the case to trial, Moore said.

After advising Quantavious’ mother not to sign the probation agreement, Moore filed a motion requesting the Tate County Youth Court either dismiss the case or set a trial. A hearing on that motion has been scheduled for Jan. 16.

Senatobia Police Chief Richard Chandler said the officer involved in the boy’s arrest violated their training on how to deal with children. Eason previously noted that she was denied the ability to drive her son to the station because the cops insisted on putting him in the patrol car.

However, per NBC, Chandler said those officer in question are “no longer employed” and suggested other officers would be disciplined. Eason ialso announced plans to file a lawsuit alleging the incident was racially motivated.

#A Black Mother Read the Conditions of Her 10-Year-Old Son's Probation. This is How She Responded#mississippi#senatobia#police misconduct#adultification#Black children

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

also, I am really fucking sick of (white) people infantilizing this school shooter. meanwhile they say black & brown kids are "grown" for less. this is mostly on Threads, but I saw a white woman say a black girl (6 or 7) was too "grown" for being scared of bugs outside. people adultifying black boys for giving water on the side of the road. adultifying Congolese, Haitian, & Palestinian children.

also these people saying that he shouldn't be charged as an adult for killing 4 people. again, black & brown children and even protestors are locked up for less. this whole thing pisses me off bc it could've been prevented a long time ago.

#my thoughts#ranting#gun violence#gun culture#gun control#apalachee high school#adultification#adultification of black children

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

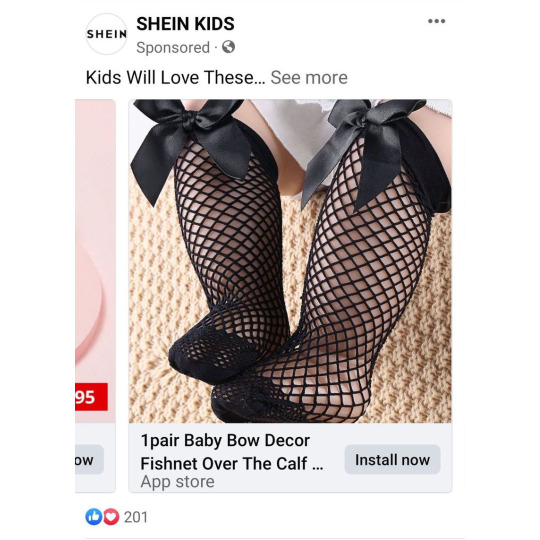

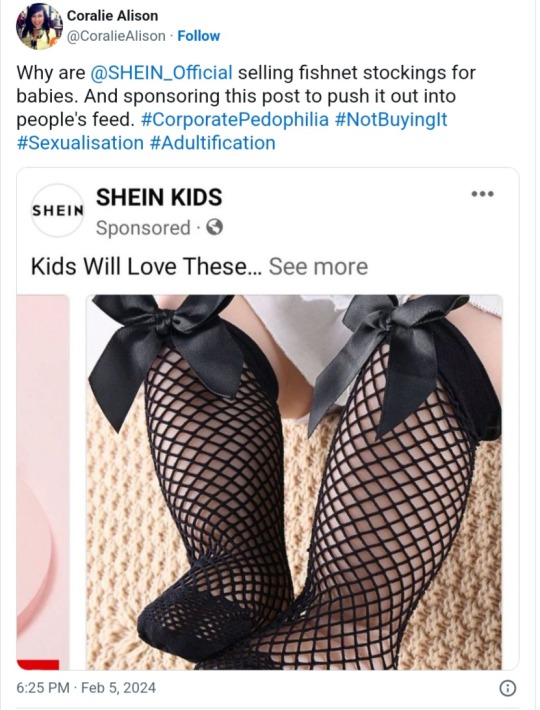

Its not just about fast fashion

Posted by Coralie Alison 24718sc on February 09, 2024

Earlier this week a supporter sent us a screenshot of a sponsored post on Facebook where giant e-commerce platform SHEIN was pushing thigh-high fishnet stockings for infants. "This is a massive red flag for me" she said.

We discussed it as a team and our Movement Director, Melinda Tankard Reist said "This major online e-commerce platform thinks it’s ok to sexualise even babies by flogging thigh-high black fishnet stockings. Shein has linked babies with an item of clothing commonly associated with the sex trade. We have documented other examples of Shien’s exploitation and adultification of children including padded bras and see-through costumes. The company must be called out for pedo whistling."

So we decided to share the image on Facebook, Instagram, X(Twitter) and LinkedIn calling on all our supporters to contact SHEIN and demand they remove the item from their site.

Clearly this campaign struck a chord with many as we had hundreds of comments on our social media platforms.

"I have grave concerns about the mind of the person who thought these a good idea - I think they need help of some sort."

"What the actual! That’s disgusting"

"Appalling"

"Yuck!! 🤮 This is all kinds of wrong. Actually makes me feel physically sick."

"Words fail at this sickness"

"SHEIN this is not a good look….."

"Shame on you SHEIN"

"SHEIN this is disgusting. I will be spreading this info to everyone I know so that your company is boycotted."

"I wrote a book about pornification of reality and this is the worst thing I've ever seen."

"This is not the first time. SHEIN have a history of sexualising girls. We must call this out!"

This also came at the same time that SHEIN was also under fire publicly for other items that adultified children.

Not only are the fishnet stockings inappropriate for its ties to the sex trade but they would also be incredibly impractical for a baby. The sponsored ad says “Kids will love these” - yeah two huge bows on your knees when you’re learning to crawl. Slippery feet when you’re trying to stand and take first steps. Let kids be kids!

We then inboxed Peter Pernot-Day on LinkedIn who is head of Corporate Strategy and bought the issue to his attention. The beauty of social media is that we can contact people in senior management.

When we checked the website link later that day the item could not be found.

This is the power of using your voice. Together we rallied our community to collectively speak out and say "This is not okay!" Kids need the adults in their lives to protect them, to advocate for them and to take action when something in our society is going to harm them. If you're not already a part of our campaign movement please sign up today to be notified about future campaigns. (It's free and we promise we will never spam you.)

It is great that the item has now been removed but why do we need to have these campaigns in the first place? Kids deserve better than SHEIN’s sexualisation and adultification.

But our campaign against SHEIN doesn’t end here. Unfortunately the corporate sells a range of highly sexualised and adultified items. We’ll say more on this soon.

See also:

SHEIN fetishises ‘school girls’ for profit

SHEIN flogs see-through g-strings for toddler girls

SHEIN’s ‘highly sexualised’ image found in breach of ad code of ethics

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1 of whumptober!

This fic was cross-posted on Ao3 here

Just One Day

Safety Net | Swooning | "How many fingers am I holding up?"

Fandom: My Hero Academia

Words: 1,040

Warnings: sickness, overexertion, self-hatred, human experiments, broken promises, adultification of a minor, child abuse

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Hey, uhhh…3?” someone asked.

I turned. “Oh, hey 7. What’s up?”

“9 sent me to see you. Whatcha doing?”

“Fixing the home remedy for tonight’s batch of allergic reactions. Our stupid ‘caretakers’ decided that fish sticks would be a brilliant choice of dinner despite at least 170 of the nearly 300 of us being allergic to fish or the oil the use to fry shit.”

“Really?”

I scoffed, “I know right? You’d think they’d realize what a bad idea that is.”

“No,” she said, “I mean you know how to combat allergic reactions?”

I looked at her confused. “Yeah, I’ve been the one making the remedies for everyone since being chosen as an experiment… did you really not know this?”

“I mean, I knew someone was making them, but I figured it would be one of the adults, not… you… do you even have allergies?”

“No, but that doesn’t really matter?”

She was stunned. “3. You’re 11. Are you trying to tell me that ontop of caring for literally every person in this facility, teaching everyone Japanese, making sure we’re all safe and that fights dont break out, keeping us educated as possible, ensuring we all make it to sleep at night and tending to the other kids teens and sometimes adults that have issues sleeping, you’ve also been the person keeping track of allergies and making the drinks infused with whatever it is that keep allergies from being life threatening?”

“Uhhhh, yeah? Why is that so confusing to you?”

“3! You’re 11 for crying out loud! Are you trying to tell me you’ve been single-handedly taking care of everyone in every aspect imaginable SINCE YOU WERE NINE?!?!?!”

“7. Calm down.”

“I will NOT! You’re a fucking fifth grader taking care of nearly 300 people on your own!”

“And I’ve been doing that job just fine for 2 years.”

“3-”

“Sayovai.”

“No, I dont wanna hear it, what the actual fuck 3?-”

“Sayovai.”

“You cant be serious, I mean-”

“SAYOVAI! YEHLISA UMOYA!”

She finally paused.

“I am fine. You are fine. I am doing what I have to so we can all survive here, I’m our safety net. Ngicela ungithembe nje, kulungile?”

She took a deep breath and nodded. “Fine. So long as you promise awuzicindezeli… you can promise me that, akunjalo?”

I laughed a bit. “Yebo, ngiyathembisa.”

“Good.”

----《 ¤ 》----

I tried to keep my promise.

----《 ¤ 》----

“3, you doing good?” Max asked me.

“Huh? Oh, yeah, I think, just a mild sickness…”

He paused. “Go back to your room.”

“What?”

“Go back to your room. If you’re sick right now, you have to go rest.”

I protested, “I’m fine Max! It’s just a mild sickness of some sort…”

“OV, if you could see yourself right now, you’d know damn well this isn’t ‘mild sickness’.”

I scoffed.

“You’re barely walking right now.”

“Liar.”

“I’m not lying, I-! Actually, you know what, stay right fucking there, I’m getting 9.”

“Okay, but I’m telling you, it’s not that bad.”

I waited for a while.

They finally returned but… Was I on the floor now? When had that happened?

There was some noise, it was faint. Like someone was calling to me. I saw what looked like a hand in front of me. I made some sort of noise, trying to respond. I felt like I should be panicking, but I had too little energy.

Next thing I knew, I was off the ground. Was someone carrying me? Everything was blurry. I could barely keep my eyes open.

Then it was soft.

Incredibly soft. I recognized the feeling of a bed.

I melted into the dark surrounding me. Eventually my hearing cleared. And I was able to open my eyes again.

“3? 3 are you awake?” I heard.

“Mmmmmm…”

“Hey, hey! Dont fall asleep again! Look at me,” it sounded like Relena.

I opened my eyes and weakly pushed myself up. This whole situation was so vague in my memory… I feel like I have something to do…

“Hey, 3, look at me. How many fingers am I holding up?”

I concentrated as best I could. “Mmmm…. Four?” I guessed.

She sighed and put her hand down, “No OV… Just rest, I’ll take care of today. You’re too out of it to do anything right now.”

That jogged my mind a bit. There’s… a lot of us… in the building… I’m meant to be taking care of us… I’m meant to be taking care of us!

I instantly started to get out of bed and was just as instantly pushed back into in. “No 3! You stay here!”

“I’m meant to… be taking care of… the others right now!” I slurred.

“No! I’m taking care of the others today! You’re sick!”

My vision started getting blurry again and I could feel a tightening in my throat. “But I-"

“But nothing! Rest!”

I felt something warm go down my cheek. “I’m supposed to- I’m our safety net! If I’m not there and something really bad happens-”

“We’ll take care of it! There’s more people than just you here, 3. If things really go wrong, we’ll figure it out.”

I was starting to have some trouble breathing. Crying. That’s what’s happening. I’m sobbing.

“But- the, the others-”

“Vee, I can take over for a day. It’s one day. You’re usually our safety net. Let us be yours.”

She lifted my mask and wiped away my tears. “We’ll be fine. Just take a break. You’ve already done way too much for your age. Just one day, okay?”

I nodded as best I could. I ended up crying myself back to sleep. Even after waking up again, this time alone in my room, I couldn’t shake the feeling I’d somehow failed everyone.

It should’ve been fine. I should’ve been able to handle it. It’s my job to take care of the others. Today shouldn’t have been any different.

“Hey, 3, you awake in here?” someone called from the doorway after a while, pulling me from my thoughts.

“Hm? Oh, yeah, what is it Agno?”

“Dinnertime. C’mon, join us. We missed you today.”

“Yeah, I’ll be there in a bit, just gimmie a moment.”

You shouldn’t have missed me today. Because I should’ve been there. I should’ve been there.

#whumptober2023#no.1#safety net#swooning#how many fingers am i holding up#my hero academia#sickness#sickfic#self hatred#overexertion#adultification#broken promises#child experimentation#human experimentation#experimentation#child abuse#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writing#writers#creative writing#my writing#whump writer#whump writing#whump scene#emotional whump#whump community#whumpee#whump#oc: ov

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the world braced for the verdict of the Chauvin trial, in Columbus, Ohio, there was another fatal shooting of 16-year-old Black girl named Ma’Khia Bryant. Many who watched the graphic and gut-wrenching bodycam video have decried the officer who deemed it necessary to use lethal force to defuse a physical altercation involving the Black teenager.

When juxtaposing what feels like a never-ending pattern of police brutality against Black people with the treatment of white perpetrators, there is an obvious disparity that highlights the pervasive nature of systemic racism. White gunmen who commit heinous crimes are often treated differently, with police being able to apprehend white suspects and bring them safely into custody.

Three recent examples of this: 21-year-old Dylann Roof, who was safely arrested after entering Emanuel African Methodist Church in Charleston, South Carolina and killing nine people in 2015. What’s even more disturbing is reports that police brought Roof Burger King following his arrest. In 2020, during protests of the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a 17-year-old gunman, Kyle Rittenhouse, used an AR-15 assault rifle to kill two people and injured a third. Law enforcement apparently offered Rittenhouse and a group of militia members water at some point before the shooting took place.

In March 2021, after a gunman shot and killed eight people, with six of them being Asian, Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office Director of Communications remarked that the shooter was having a “really bad day.” These comments drew public outrage at the humanization of the mass shooter. Black youth aren’t given the opportunity to be humanized, with a number of tragic stories illustrating this.

Over a decade ago, 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley Jones was fatally shot by Detroit police who were looking for a murder suspect. In 2012, the world was gripped by the killing of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was shot by neighborhood watch captain George Zimmerman, who thought Martin looked suspicious. In 2014, a Black youth named Tamir Rice was shot by police. Rice, who was only 12 years old, was thought to be 20 years old. In 2015, a video of McKinney, Texas police officer Eric Casebolt went viral. Casebolt was filmed yelling at Black teenagers and threw one teenage girl to the ground while kneeling on her back. The video sparked rightful outrage at the excessive force used on the young girl.

Examining patterns of police treatment towards Black youth highlights a prominent issue: the adultification bias, which is the phenomenon where adults perceive Black youth as being older than they actually are. When the adultification bias was examined, one study found that Black girls as young as five years old were perceived as being less needing of protection and nurturing, compared to their white counterparts.

Research indicates that Black boys are perceived as older and less innocent when compared to their white counterparts. “Black boys can be seen as responsible for their actions at an age when white boys still benefit from the assumption that children are essentially innocent,” shared Phillip Atiba Goff, Ph.D., who authored a study examining this phenomenon in more detail. Black girls are treated disparately compared to their white counterparts and are more likely to be seen as older, while having to navigate the combined effects of racism and sexism.

The adultification bias contributes to the continued harm and abuse that Black youth face, not just at the hands of law enforcement, but also in the education system. When Black women and girls are mistreated, harmed and abused, it is less likely to be reported on. The Say Her Name campaign co-founded by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw was designed to bring greater awareness to this issue.

Disrupting the adultification bias must first begin with awareness that this problem even exists. Despite the wealth of evidence detailing the ways it manifests, greater understanding is necessary. Training about the adultification bias should be mandatory, especially for folks working with and around Black youth populations. Understanding the ways that the adultification bias manifests as well as how to mitigate this type of bias is imperative.

Although research indicates that those who are marginalized are likely to internalize some of the biases and stereotypes about their own identity group, it is likely that having more Black people working with Black youth populations would lessen the occurrence of the adultification bias. One can assume that having experience and exposure to Black youth may increase one’s understanding, and limit the adultification bias from taking place. Resources must be allocated to support education about the adultification bias and how it can be interrupted. Lastly, rather than resorting to punitive measures when dealing with Black youth, we must encourage the learning of de-escalation and conflict resolution strategies.

#How The Adultification Bias Contributes To Black Trauma#adultification of Black Children#adultification#Black Children Matter

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

neverland ain’t for us

the end takes you back to your cousins house,

unstitches your scarred knees smooth.

everyone’s still alive and the tv is furry with static

playing news you’re yet to understand as music floods the room.

adults double over when you sing along to old tunes

they claim you shouldn’t know,

their laughter swallowed by bass booming from

speakers older than you.

under barbecue smoke in the garden

you weave between legs, so young now you turn god,

building technicolour realms with your words.

the other kids jump in without question,

adding their creations in an unspoken exchange:

you climb into my head

and i’ll climb into yours.

balancing paper plates and chilled malt on the stairs,

you devise a plan to sleep over,

send the younger siblings for good measure.

then beg for change and spoil your appetite with a cone

because everyone’s still alive and summer lasts forever.

don’t make a sound when the big kids let you in their room,

tuck yourself into the corner of the bunk bed, woozy from sugar

as they freestyle over grime beats and talk about things

you’re too giddy to decipher.

one day, none of you will speak until the funeral and

soon you’ll learn about what happened

at a bus stop on well hall road in ‘93.

technicolour will fade as your scars do,

and the music will dim enough for you to hear

the reporter say another black kid

your reflection, your cousin, mum says she knows the family

has run out of summers.

you’ll hide in baggy clothes when you realise the weight of your shade

and discover how streetlights turn spot on kids like you,

never really kids to begin with,

who find truth at the end.

heaven is the old house,

it’s warm here.

everyone’s still alive and i know how to save us

— quick, before the sun leaves.

climb into my head

and i’ll climb into yours.

s.o.

#poetry#poem#original poem#writing#black poets on tumblr#black poetry#childhood#nostalgia#black culture#adultification#sharloola

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

People acting like Bailey Bass/Claudia looks like she’s in her 20s or something is crazy to me. It’s gotta be adultification, there’s no other explanation

#claudia#claudia du pointe du lac#interview with the vampire#bailey bass#adultification#blackgirlthoughts

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA: Azula is an adolescent from an abusive home and a culture that normalizes extreme violence even toward children.

This, more than most factors, shapes most of her destructive behavior. Seeing one's own mental health struggles in her character and identifying with her through that is one thing, but it's increasingly uncomfortable to see fandom pathologize almost every aspect of a teenaged Asian girl's personality and behavior, as though she's a DSM-V checklist rather than a child shaped by a toxic environment.

Edit: F'real, given her circumstances, why is it always, "Azula must be crazy" and not, "This is what happens to a child in that toxic environment"?

#azula#azula is not her breakdown#azula is not a white girl#pathologizing#adultification#azula is a girl of color

44 notes

·

View notes