#All justice is restorative and genuinely rehabilitative

Text

Moving to The City is ridiculously easy, it's just like "What are your intentions? It's fine if you just want to have a nice place to live, we get that a lot. Do you have any particular work you enjoy or are interested in trying? No, no we don't need you to do work if you can't or don't want to, we just want to make sure you have the basic supplies to do that work if you'd like to. If you change your mind you can always contact the officials to get you set up with new supplies. Any specific accommodations you need for your home or for life in general? Yeah we can do that. Welcome home."

#Like you'll be encouraged to pick up a skill of some kind just because the various officials feel that it's important enrichment#But no turning away because you can't do stuff. Disability friendly city.#Like if you just wanna paint at home for fun you'll get very basic supplies delivered regularly#You'd only have to work for money if you want like super nice paints brushes and canvases#The entire economic system there is based on the idea that all folk thrive when their needs are met#And that you'll get more skilled craftsfolk if everyone has a chance to try anything#Also anything that would be considered crime has everyone evaluating what need might be unmet and caused it#All justice is restorative and genuinely rehabilitative

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying to parse my thoughts on Izzy's death and why I had a different reaction to it than I thought I would. To summarize: I thought I wouldn't like it, but also that they wouldn't do it; the opposite happened– they did it but I'm ok with it.

I'm also feeling like talking through some mourning for an amazing character, so follow along if that's you, too 😌

(I should probably clarify the following thoughts are coming from someone who deeply enjoyed this season.)

I first wondered what would be of Izzy around the end of season 1. I expected him to have a heel-face turn – which I object to calling a redemption arc and I'll get into why, because the distinction ties into his death imo. A lot of antagonistic characters' changes of heart end directly in death, but I thought they'd subvert that trope. And they... did, actually, despite Izzy dying. Not an option I had imagined.

What the show avoided is the logic, the set of tropes attached to the deaths of this kind of character. These deaths usually come as a consequence of the character's changed ethics or "redemption". My being against that scenario came from the diverging natures of traditional redemption arcs and OFMD's rhetoric.

A traditional redemption arc functions by a kind of catholic logic, if you will: the villain can become one of the good guys by balancing out his "sins"/bad deeds with enough good deeds to tip a moral scale. This often involves a purifying suffering, which acts as an agent to expiate one's faults. To the viewer, this suffering can serve to activate our empathy and make the character more sympathetic. It can also legitimize his quest: our trust in the character's good intentions comes from seeing that the character is ready to make sacrifices to become better and he isn't deterred by the hardships of doing the right thing.

The death occurring at the end of a traditional redemption arc acts as the ultimate sacrifice and/or purification. A number of ideas might be at play behind it, depending on each story: only in death can the soul become fully pure, or a final sacrifice is "needed" to demonstrate the change once and for all, or change was only possible up to a point after which there is no viable/acceptable future – the character deserves moral points for changing, but not so many that he also deserves a full life, or past crimes make him more expendable, etc.

But these are all ideas that aren't evoked in any of the crew's journey in OFMD. For starters, the show isn't interested in "catholic" redemption; its focus is on reintegration/rehabilitation into the community. Rather than appealing to the more traditional (in Western media) and more christian principle of "purification of the soul through mortification of the body", it plays with notions of restorative justice.

We see it especially this season with Ed and Izzy. Ed's arc is a whole little lab for it. We have the community being made to decide whether he can stay or should leave; catbell!Ed is made to apologize to the people affected – which he initially does abysmally, with what fandom has dubbed his "CEO's/YouTube apology". Later, he's given the opportunity to have a more honest and genuine conversation with Fang where he learns about how he hurt him. He's made to repair some of the material damage his behavior caused. Some members feel repaid by the idea that they did to him the same he did to them (Fang) while others don't (Lucius), and the show touches on what this means for each/legitimizes both feelings. Arguably, Ed using his treasure to throw Calypso's birthday party – a much needed refrain and moment of social (re-)connection within the community – is an additional form of reparation. While Stede's belief in Ed has a clear role in helping Ed change for the better, Izzy's s2 journey focuses even more intensely on the role of social support within an individual's constructive (re-)integration into their community. The show is condensed by choice of format, but the beats are all there.

With that kind of rhetoric set up, I'd never be able to accept Izzy dying in a way that feels like a punishment for his past crimes, nor in a way that should "confirm" his positive change/"purify" him for good. And he doesn't! By the time he dies, we know full well he's deeply changed, it's already established to completion. How it happens has nothing to do with proving himself – he's randomly shot in battle. It's never questioned that the time he got to live surrounded by affection mattered. The speech he gives Ed is only possible because he's changed, accessing a completely different perspective on piracy/life than before, like we see when he talks to Ricky earlier. The reason the whole crew is paying respect and crying is because he became "the new unicorn", a treasured member with a defined role. But his death itself is the show going back to the initial symbolism of Izzy as ultimate pirate. The narrative function of his death is underscoring that the age of piracy has come to an end. It's nothing to do with his change. It's posited as the "natural conclusion" (again, by symbolic function) of a character that represented piracy through-and-through, not the "natural conclusion" of a process of becoming better.

And for me, that difference changes everything. I can see and accept the logic behind it, even as I mourn Izzy as a character. It makes the grief feel like a catharsis I experience within the context of the story I'm watching, rather than a grief I feel from a show "betraying" me.

It's also a difference that completely changes how Izzy's death relates to his queerness. Izzy's change is intertwined with being able to express queer affection openly. Becoming "a unicorn" is this extremely queer imagery already – a magical rainbow creature. His role becomes akin to a mother to the crew (the mother hen!Izzy many headcanoned last season, tapping into his potential), a position that isn't extraneous to older queens, including our honored real-life mean-old-queer men. Last season he threatened another queer man for showing too much delicacy, effeminacy, vulnerability. Now, his change is a process that culminates in him singing a tender love song among the crew in drag. He's given the privilege of playing the soundtrack to our protagonists making love for the first time, which ties him symbolically to the event in a way it does no other crew member. Suffice it to say that insinuating his process of change should end in death would have been disastrous, as far as I'm concerned. Antithetical to the show's supporting ideology.

But that's not how it went. Grief occupies a big role in the queer community, but it's so rare that we get to experience it cathartically. In real life, we often have to contend with the ways queerphobia causes us trauma or even shortens our lives, or the lives of our friends. In fictional narratives, a lot of characters that get to express queerness unabashedly still die for the transgression. They're still usually the only queer character with relevant screen time or at all, at best one of two that formed a tragic couple.

We almost never have the opportunity to just mourn some motherfucker who died because they meant something else as well that was central to their character. To mourn and know we're mourning someone who wasn't ever punished for being queer-as-in-fuck-you and going all out. To mourn and not feel like it's another message of queer doom, because for once the character is surrounded by an entire crew of other queer characters that go on to live and be happy. To know the story is saying something about life, not about being queer. To know this kind of crafting was deliberate, too, because the creator has talked about working to avoid those tropes. I struggle to remember another time I had the opportunity to grieve for a queer character like they're a human being, without the implication that it's queerness itself that's a death sentence.

And honestly? It feels good. It feels like a form of catharsis I do not dislike. That I'm maybe kinda glad for. OFMD is and stays a magical world. Beyond that, in a show full of queers, one of them dies after getting some extraordinarily meaningful happiness, and it's peaceful, and I get to just be sad for the fucker without the gutting of being reminded that if you're gay, better not shoot too high. It feels like a completely different emotion that no other show, for now, would give me, but OFMD. To me, it's yet another thing it's pulled off.

As it's been known to do.

225 notes

·

View notes

Note

i dont know who a writer would be who could handle it (more ignorance on my part than lack of good writers though there is that too) but i’m curious what you think a real, earned redemption could look like for jtodd and if you would even want it.

i definitely think there’s a path, esp because so much of bruce’s philosophy relies on a genuine and earnest commitment to rehabilitation and restorative justice, but i also think (and maybe i’m wrong if anyone has comics recs lmk) but i don’t think i’ve seen a comic with the hard work of reaching out and healing/moving on from the past from both bruce + co and jason

i really love his character but especially now i don’t think dc knows what it wants to do with him so he’s in this perpetual limbo where he’s always on the edges of the batfam, a fringe black sheep member but a member nonetheless, still entangled with them

personally i would love either way but i wish dc would either separate him and let him do his own thing that’s not just punisher lite or really actually go through the process of making amends and fully integrating with the crew, learning to love and trust again and all that

omg this really got away from me so apologies for just word vomiting in your asks but yeah im curious dc puts you in charge of j todd’s next big character arc, what would you do with him

i don’t think that’s ignorance — dc is not known for hiring writers who can include and explore complex themes in their comics lol

personally i think the easiest way to trigger a redemption arc for jason would be take him away from the batfamily and force him to interact with other villains, specifically amanda waller and the suicide squad. task force z came kinda close to this, but didn’t push the concept far enough imo. jason’s interactions with black mask were some of the best parts of utrh — i want to see his ideology be questioned by people who do the exact same things as him, and are fully aware that they’re selfish and destructive.

the truth is that while jason is acting out and murdering people, he’s still bound to bruce. he is autonomously making decisions, but fundamentally he is choosing to stay. he’s choosing to be tethered. he’s choosing to care. seeing the indentured recruits of the suicide squad would be confronting to him.

i don’t think the happy family fanon dynamic will ever be possible without ruining every included character simultaneously, but that’s okay. that’s not what jason truly wants anyway.

specifically, i don’t think he’ll ever be able to work with bruce, which is why i find the jason + dick dynamic so interesting. you’re right — bruce’s fundamental mission is about restorative justice, and he would continue to reach out. dick, however, is a realist, and is extremely protective and territorial of the people in his care (tim, damian, the titans, etc) all of whom jason has hurt. jason has been shown on page to respect dick and his position, and simultaneously think he’s pathetic because he refuses to lose control.

for me ideally, he’d be someone on the very outskirts. i feel like dick and babs would be his point of contact — dick because he’s keeping an eye on jason, and babs because she has way less hangups about working with killers. otherwise? i think he’s lost the chance to properly bond with anyone who knew before he died. that’s the risk he took when he decided to become the red hood. that’s the tragedy.

but to be perfectly honest, the most restorative thing jason could do would be to leave the game entirely, and relearn how to live.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just thought of something after seeing the injustice that is the Bionicle ending, and TW for themes of racism, amd just a heads-up that this is essentially me trying to do a justice and more pulling muscles while reaching, so bear with me:

So, during a period of recovery, the Matoran and Toa just take time to relax, to sit still, be calm, and not talk to anyone

It goes as well as you think because they end up being plagued with nightmares and they aren't sure how to deal with it

The Toa are especially taking it hard because what Teridax did to them has not gone away, or at least hasn't gone away fast enough, like it's steadily getting better. Whenua is still blind. Nokama still can't talk. Matau's state is deeper because he's feeling what Vakama feels. Onewa is still not all there. Nuju still can't understand anyone. Vakama is still in pain from what he's been through

It doesn't help that the Agori and Matoran don't really like each other, and that puts a strain on getting everyone rehabilitated, though the Glatorians are more open toward the Toa

To say the least, there's a lot of breaking up fights, a lot of arguing, and just hostility that leads numerous of the people to try and ignore each other and be ready to throw hands

Add to that the Vorox, the Baterra, the Bone Hunters, and Skrall, and people are just exhausted and close to just laying in bed forever and accepting that they might not live to see tomorrow

I will say that the Toa Nuva are active, and try to stay active, but this is more them working so they're not focusing on the events of the Destiny War or the Rein of Shadows, and it doesn't help that they'repossibly realizing that the way to end a fight is to end your opponent and they are trying to keep things peaceful, so there's that. The Toa Metru, namely, Nuju, Nokama, Vakama, and Matau, eventually join, wanting to get back into helping around even if no one cares

Onewa and Whenua are told to stay back, the Toa Mahri guarding them and making sure they're safe. Whenua is frustrated because he can still fight, sight loss be damned, but Onewa would rather wander for a second, his mind recovering enough to take in where he is. He's intrigued by the plant life, the animals, the people that don't see him, even a little scarabax that's missing his friend, so he joins Onewa

Also joining Onewa is Kiina, who's at first very vocal about seeing him alone, but slows her role when she sees she genuinely scares the hell out of him. She also points out that the scarabax belonged to a friend of hers, and she's glad to see Click(the scarabax) make a new friend

There's awkward silence, but Onewa walks toward a mountain, Kiina following so he doesn't get hurt. She finds him staring at the blank face of the mountain and she admits that it's literally just a mountain, that it's not something anyone wants to mess with because of rockslides

Onewa still stares at it and Kiina helps him back to where the Matoran and Toa made camp, the Toa Metru relieved to see their friend is alright. Kiina learns Onewa used to be a carver, an architect even, so maybe he was looking for something to work on. She tells everyone to stay safe and give them space, though Onewa and Click start messing with each other because they're bored

With the other Toa, they have little success in speedrunning a melding that Takanuva saw, but have bigger problems with the Vorox, the Marendar, and Baterra. While they're resting, Vakama goes to take care of it on his own, but he's followed by Jaller and Takanuva, who he lets tag along, just in case. All three are caught anyway by Tahu and have to be led back to where the others are because Vakama is/was the leader of the Matoran and really could be useful in keeping things civil. Takanuva, having his memory fully restored, could prove to be helpful by explaining more of what he knows and remembers to get the Agori to not hate him, and Jaller is still kind of a rookie and needs to stay safe

It's a tough pill to swallow for all three of the friends, only now they have time to actually breathe and get it out of their systems, which Jaller does because he's still processing that all three knew each other. When asked, Vakama reiterates he told the Matoran about Metru Nui as legends because that was easier than saying, "we used to be friends, and I gave up my power to get you out of what would have been an endless sleep that would have killed you. I lead you now." Jaller isn't concerned about the Metru Nui stuff, but is upset about Vakama not telling anyone about the events of Time Trap, and the time loop he put himself through

Vakama admits that he'd already put his friends in danger once, having gotten them mutated and almost killed, and didn't want them to suffer like that again because of him, not with the Matoran and their lives on the line

Jaller falls silent and Takanuva has said nothing this entire time, only watching the camp instead. Vakama asks if he's alright and Takanuva says he's fine, not wanting to hear what anyone has to say right now because he would rather make sure the Matorn and Agori get along. Jaller steps closer and sees that Takanuva is VERY not fine at all, as in he's distraught and trying not to break down in front of his friends

WEELL, no time because they hear clamoring and race out to see what they think is Whenua dragging Nokama away by the foot, but there's an issue: Whenua, who is still blind and wears a blid fold, is not wearing that blindfold and his eyes are different(I know the Baterra is supposed to be undetectable, but I imagine they don't have a full understanding of the Toa and their "Tells" for who's who)

Nokama breaks away and runs, trying to tell Vakama, Jaller, and Takanuva to not draw their weapons as they, naturally, draw their weapons. Luckily, though, with the Baterra distracted by three new disguises and targets, it's taken down by Gresh, who uses a mix of elemental powers and maybe hand to hand combat to get the job done. They're all shaken and stirred, but Vakama asks Nokama why they shouldn't draw their weapons, Nokama revealing that it's what got he nearly killed in the first place. Gresh isn't sure where they were or how they cane to be, but there's a cave Kiina goes to that has the history and science of Spherus Magna written on the walls, so that's an option they have

Nokama would like to go there, as she can possibly translate what's written, but Gresh politely asks that the Toa stay behind; they'll be easier to pick off if they're separated

Nokama does not, asking to talk to Kiina and see the cave, which Gresh ultimately agrees to. They rest up for the night, Vakama keeping watch, even though Jaller points out that he's making himself lose sleep again, and who devides to speak with Vakama but Raanu, who admits he's seen a lot of weird things in his time, but he wasn't expecting to see the Matoran and Toa again. Vakama's confused, but Raanu admits Vakama probably wouldn't remember; he would have already possibly been inside of the Great Spirit Robot by then

Vakama admits such and, being tured and not feeling his best, asks Raanu if he's here to tell the Toa and Matoran to get lost. Raanu is aghast and states he's actually here for some good old intel, to get to know the new inhabitants of the planet that's just been put back together again, and seeing as how they're all stuck in one place with no other planet to go to, better to stick together and get to know more about each other

Vakama agrees and asks where Raanu would like him to start, which Raanu decides on Vakama himeslf; he's led the Matoran for so long, weary leaders tend to recognize each other. Vakama admits he isn't much of a leader, and Raanu calls that another reason they could get along, because Ackar leads the Agori more than Raanu does. The two sit and spot a Matoran having a disagreement with an Agori before they part ways, and Vakama sighs that no matter what happens, there's always another fight to win, only now it's multiple at once. Raanu agrees and calls it the natural cycle of things; if life was peaceful, it'd be too easy

After some silence, Vakama starts to explain his life and being in Ta-Metru, though he does explain more about stuff beyond that

At a distance, a group of Matoran seeing the two talking and are on edge because Raanu could be setting Vakama up to be tricked, but also say that because the Agori have not been very welcoming

To be fair, the Matoran have been irritatable towards the Agori because of everything they've been through, with Rahkshi, Bohrak, and Vahki and being stuck inside of a giant robot that was bent on making them all suffer.

So, what the conflict between the Matoran and Agori is, is one side being wary from all they've experienced and being on edge because they don't want to deal something else they wants to kill them again, for the fifth or seventh time. The other side is also wary, having dealt with Bone hunters and Skrall, and they have some foggy memory of the Matoran and, last they remembered, the Matoran weren't sentient, so they're freaked the hell out

Either way, there is still conflict, but it's equally lowered and raised at seeing Vakama and Raanu talk and at seeing the Toa with the Glatorians

#bionicle#ramblings#long post#toa metru#toa nuva#toa mahri#vakama#jaller#takua#takanuva#matau#nokama#onewa#whenua#nuju#ackar#raanu#kiina#gresh#glatorian#tw racewar#the agori and matoran don't get along well at this point

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Cozy Glow got stoned

I'm told to use tumblr to let out my fandom rants so here it goes.

All you folk who keep saying Cozy Glow didn't deserve it don't understand Equestrian justice. You're used to the justice system we use in the real world which is focused on deterrence and retribution. Since Cozy Glow is young you think she should get a pass on the retribution side, which is how we deal with juveniles in the real world.

That's not how this shit works in Equestria okay? They're primarily focused on a restorative justice model, but before that can happen there's two questions that they ask; is there a possibility that they want to change (because you can't make someone change against their will) and how much of a threat are they?

Why does Trixie get away with what she did with the alicorn amulet? Because without the amulet she isn't a threat. Why do Flim and Flam keep getting away with their cons? Because their threat of harm is so minor. They aren't forced into some sort of rehabilitative program because they don't need keeping an eye on and the best rehabilitation (as far as Equestria is concerned) is genuine natural forming friendship.

Starlight is given her chance because she won. The only reason the proper timeline is restored is because Twilight talked her down. Starlight realized she was the villain and wanted to change. An eye was kept on her because she was a potential high level threat.

Cozy Glow is given the oppurtunity to explain herself by Twilight and she doubles down. She just wants power and doesn't care what you think of her. She is a threat not because of phenomenal cosmic power but because her special talent is manipulation. Seperate Trixie from the Alicorn Amulet and she's not a threat, but Cozy Glow is always a threat because she has the capacity to create the situations she needs. Which isn't to say she'll always succeed without fail of course, but anyone who tries to rehabilitate her with friendship runs the risk of actually just being a pawn in her scheming for something else. So she gets sent to Tartarus. And then she tries to take over the world with others and gets turned to stone.

You might still disagree with her deserving it, and that's okay. You don't share the same model of justice that the Equestrians do. But at the very least don't argue that it doesn't make any sense. It's in line with how they always handle ne'er-do-wells.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ftr I do think you can deal with abusers and rapists without a carceral system, but it's foolish to act like you can just leave them to mill about the SAME community as past victims. That's not how restorative justice works. Restorative justice is supposed to make sure the victim receives justice above all else, which means safety from their abuser. If the abuser has to leave town, I mean...sucks, but hey, give them the needed supplies and send 'em off. If anything they should be able to be sent to a community where they are closely watched and rehabilitated. shrug

but I genuinely think that accessibility is an EVEN BIGGER PROBLEM for anarchist communities, and they REALLY need to examine that more, because they are woefully unprepared for actually creating full-scale townships and communities that are actually accessible to people of different physical abilities. regardless of if you THINK your commune is on top of disability, if we're truly going to move past capitalism and ensure that kind of life for EVERYONE, do you REALLY THINK that without very dedicated paperwork and boards and people in charge of inspection, that random every-day people building a town are going to get ALL the accessibility requirements right? Do YOU personally know the regulations and grading for wheelchair ramps? How many places can you think of in your current state-run town, where the ADA already DOES inspect things regularly, that are still inaccessible? How does this get fixed on a large scale?

Believing that there is an option to simply not have a state seems to me like it overlooks large-scale regulatory needs, such as the need for accessible bathrooms, wheelchair ramps, etc. And then there's the can of worms of who will oversee people who are completely incapable of working or even moving, who may not have caretakers! What do you expect for an anarchist community to do about those people? What are you going to do about everyone who is in a fucking coma or something? Be realistic about how disabled people are, and how large the severely disabled population is. We need an organized group overseeing stuff. C'mon.

#tomi talks#now see what I am for#is for a constantly rotating board wherein multiple community members get to participate and are represented#blah blah blah this isn't about Tomi's personal utopia plans#but like. yeah lmao every time anarchists go off abt stuff#I think to myself....and what abt ADA regulations?

1 note

·

View note

Text

on internet leftism, public shaming, and how to grow as a person

at the moment of writing this, social media is hotly debating a tweet and the track record of a leftist streamer called badbunny. i'm not tuned into any of that enough to comment on who she is or if her platform is harmful. but i do wanna take this opportunity to talk about something that has been weighing on my mind for a while now.

this text was forming as i read lindsay ellis' statement leaving youtube, as natalie wynn went through her fifth or so twitter "cancellation", as sia talked about her relapse and suicidality following the backlash to music, and as pretty much every day a niche microcelebrity or normal person with the bad fortune to go viral got eaten alive on social media for their bad takes ranging anywhere from questionable media opinions to genuine antisemitism. i want to be clear that i think all of these people said and did things that deserve various amounts of criticism. this text is not to defend anyone. it's a look at group dynamics within leftist praxis.

preamble: because nothing is ever fully original, i wanna give a quick shoutout to the podcast you're wrong about, specifically the episodes "public shaming" and "cancel culture", for kickstarting a good chunk of my thought process here.

i don't use the term "cancel culture" to describe the phenomenon i'm discussing because i find it exceedingly vapid and unhelpful. the right and the left use it to mean entirely different things, none of which are well described as "cancelling".

i think the progressive/leftist online sphere is creating a more and more toxic environment by expecting perfection from people. having a big platform is a responsibility and it can be very harmful to even have so much as a bad take. but to paraphrase this video by alex peter: we don't hold people accountable, accountability has to come from within. the only thing we do is punish people. and as an abolitionist i don't think we as leftists should believe in punishment, but in rehabilitation.

yes, public shaming and deplatforming serve an important function to a) reinforce the ethics of our in-group and b) take away power from those who abuse it to harm others (since as we know the justice system does not come for the rich and powerful). but in most cases on the internet, that is not what we're doing. we're not serving a social safety measure, we're getting off on being in the in-group and doling out punishment. hell, maybe we're even getting our 15 minutes of fame out of it by commenting on a trending topic. or maybe we feel compelled if not outright forced by in-group/out-group dynamics to clarify our position on this topic, on every topic, always. but how does any of that serve the betterment of them as a person, or our society as a whole?

i want you to think of all the things you have said in your life that would cause backlash if you were in the public eye. more than that, i want you to think about the people who don't like you, who think really badly of you, and imagine that they were leading the public discourse about you (credit to rayne fisher-quann for this imagery). none of us would look good, even if we've grown and changed and made amends. i don't wanna live in a world where that is our normal. i believe that as leftists we need to move towards a restorative approach, fueled by empathy.

i believe and have personally witnessed that humans fundamentally have the ability to change and become better. but nobody can grow in an environment that puts them under constant attack. if you're busy defending yourself, you just purely psychologically cannot critically examine your behaviour and beliefs because you're in survival mode, sometimes literally. that's why we constantly see creators (and artists, celebrities, twitter's bad person of the day) doubling down on and defending their bad takes and talking about their mental health instead of apologizing. it's not fucking helpful.

there's a time and a place for public shaming, and there's a time and a place to stop and let the person actually process what happened. and you don't have to personally forgive them if they change their ways, or like them afterwards — there's plenty of creators i don't like purely because they said too much dumb shit or have politics i can't agree with or just give off bad vibes and i'm a hater. but that's a completely different issue. criticism is always valuable, but if i want our community and society to progress in any meaningful way, i need to ask myself if calling someone out serves a purpose or is just contributing to a pile-on, if i'm approaching them with goodwill and empathy or just dunking on them. if i want them to learn and change for the better, then i need to afford them the space necessary to grow. we can't build a community on punishment and fear of repercussion. our foundation must be one where we recognize each other's humanity and engage in good faith as peers.

#ugh video essay when am i right folks? i can be so insightful at two in the morning#breadtube#ethics#politics#restorative justice#activism#opinion piece

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello,

I just found your page and after reading some of your mha posts had a couple things I wanted to ask if that's ok.

1. Since you feel Hawks is not justified because he could have chosen options other than killing Twice, do you think he would have been had he genuinely been made to choose between killing him and saving others? I.e. do you think it's just this killing in particular that was not justified and thus murder, or do you think heroes killing can never be justified, even if in self-defense or defense of others? If we take the "Heroes save people" maxim to its limits, it might be reasonable to argue for a deontological approach to ethics rather than a utilitarian one, so that killing one to save others is not justified because you actively break your code (as opposed to risking not being able to save others, which would be considered a lesser moral wrong under this mindset).

2. This might very well be a stupid question, but if we consider that heroes shouldn't treat others as an it and put them down for the "sake of society", do you feel this ought to extend to AFO too? I really don't mean to use this as a gotcha moment or anything like it, but I feel like if MHA is trying to move away from a punitive justice system in favour of a rehabilitative/restorative one, we ought to consider where people like AFO fall into this system as well. AFO is seemingly entirely unlike any of the other villains in the show, but if we judge that he deserves a different fate for this it also feels like playing into the "Some people just can't be saved" notion that's been perpetuated by hero society. It is of course entirely possible, if not likely, that he'll fall in battle, or that Shigaraki himself will kill him eventually, but I feel like that skirts the issue rather than answer it. As someone who does not seem to show any remorse, desire or even ability to be saved, and in fact feels rather inhuman, what should a reformed society even do with him? Even if we could convincingly argue him to be fundamentally different and thus deserving of punishment, it is much easier for us readers who have more information to make this call, rather than in-universe characters whose judgement will inevitably be based on something less than the full truth. So even if AFO's case in particular was easily answered, it would set a precedent for cases that may appear similar, but in truth be less clear cut. Basically, I believe you feel the villain league deserves another chance because they were victims of their circumstances, and thus not necessarily beyond salvation, because they never knew normality to begin with, but what about those who were not victims, those who by their nature have insurmountable trouble fitting into a peaceful society? Perhaps it's just my mistaken assumption that such people exist and I'm reading AFO wrong, or perhaps it's the opposite and I'm giving people like AFO undue consideration, or perhaps my assumption that AFO ought to be treated as a person rather than a carocature, a symbol, is flawed to begin with, but I just really don't think a manga that wants to argue that villains are people too should go "but here's THIS vile piece of shit, let's kill him!". Am I making sense here?

3. On another note, what do you think of Endeavor's recent speech and general recent development? I've seen some people who were upset by his "Would it fix everything if we showed you our tears" line, but rather than him being dismissive or callous I just see it as him awkwardly saying that he doesn't think anything other than actions can help him atone for what he did. He's still got a lot to work through, but him recognizing that he's got something to atone for and freely talking about what he did to his family is, as I find, certainly a huge step in the right direction.

WHOO hey! Sorry for taking a while to respond. You gave me some really well thought-out questions and I wanted to return the favor with well thought-out answers. Also I was heckin busy yesterday when you sent this. So, here we go:

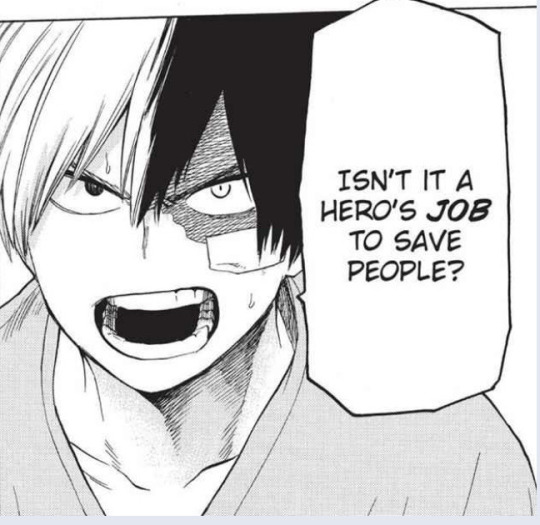

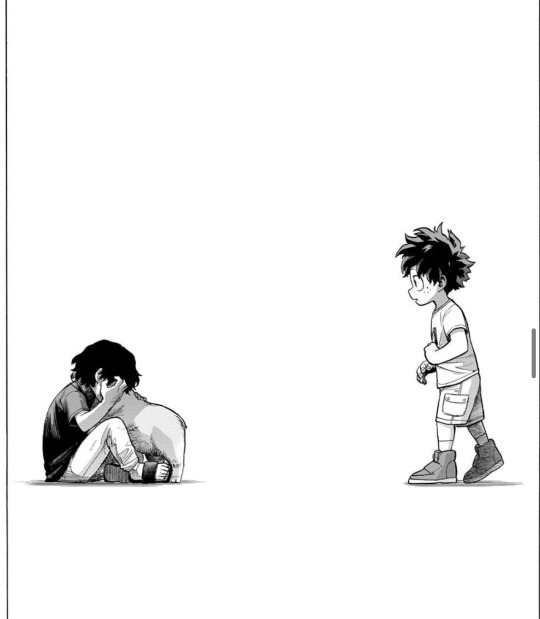

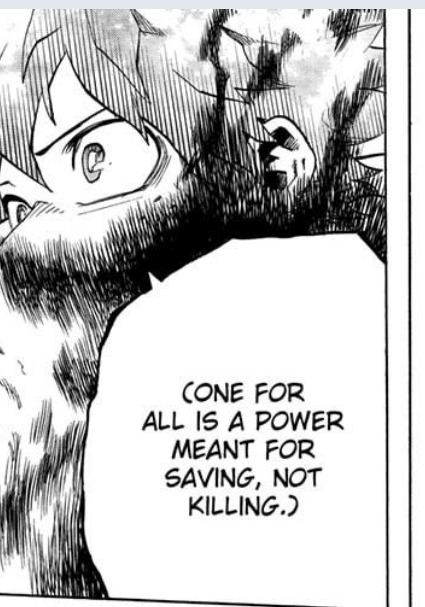

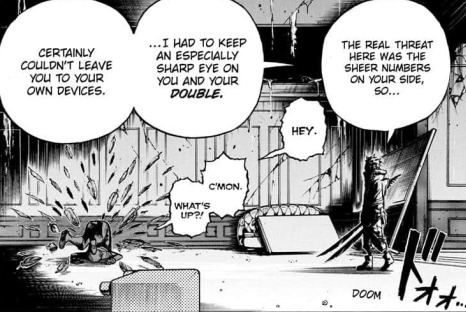

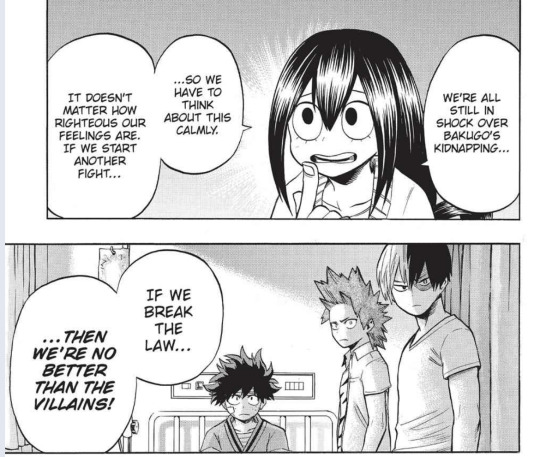

To answer this question about Hawks, I first need to clarify what it means to be a hero in the eyes of the story that is BNHA:

This honestly doesn’t even make a dent in the amount of panels in BNHA that reiterate time and time again that heroes SAVE people, but I don’t feel like I should have to spend too much time looking for them, these I used above should suffice. The one with baby Midoriya and baby Tenko doesn’t even have any words in the panel, and it’s still powerful enough to get the message across. And make me cry.

Almost every story has its own “heroes” in it. And every story’s definition of a hero is different. In Marvel and DC superhero comics and movies, the heroes usually end up killing the villains, yes? I can’t say I’m familiar with these stories because they aren’t interesting to me in the slightest, but from the ones I HAVE seen, the final boss at the end dies. But all of the heroes get to keep their title of “hero”. That’s not really the standard we have in BNHA.

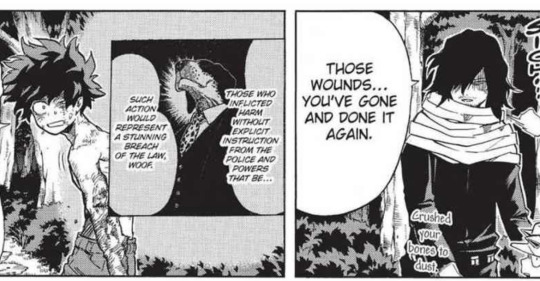

“Do you think it's just this killing in particular that was not justified and thus murder, or do you think heroes killing can never be justified, even if in self-defense or defense of others?”

So this is a fair point and I feel that the best way to answer this is by asking what you consider self defense? Say Hawks is at home mad chillin and not prepared for a fight in the slightest, and somebody breaks into his house and starts trying to hurt/kill him. He’s unprepared and at this point just trying to keep himself alive. If he ends up killing the guy, is he wrong? In my opinion, no. In real life this happens to people, and they aren’t considered murderers, as they shouldn’t be. To me, self defense is a situation where:

It’s either you or me. It’s one or the other.

I think it’s fair to say what happened with Hawks and Twice was absolutely NOT self defense. I’m not going to go into detail about how deciding to kill Twice was absolutely 100% premeditated, because there’s a wonderful post by someone else that already explains that in great detail here. But I’ll end this thought by saying that Hawks was not committing an act of self defense.

Nothing about this says “self-defense” to me.

“If we take the "Heroes save people" maxim to its limits, it might be reasonable to argue for a deontological approach to ethics rather than a utilitarian one, so that killing one to save others is not justified because you actively break your code (as opposed to risking not being able to save others, which would be considered a lesser moral wrong under this mindset).”

To make it simple for some people to understand these terms:

“Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that determines right from wrong by focusing on OUTCOMES.“ In a nutshell, utilitarian ethics means you make a decision based on how it will affect everything else.

“In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology is the normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules, rather than based on the consequences of the action.” In a nutshell, deontological ethics means you make a decision based on whether it follows rules or not.

So this is a complicated question, and my answer to this is....both? Throughout BNHA we’ve had this dilemma over and over again:

Break the rules and save the day? Or follow the rules and possibly suffer the consequences? Well, BNHA just says “Yes” lol. Do both. Break the rules and save the day. Make a decision based on the consequences of said decision, but also try to follow the rules as best as you can. Even in reality, people do this to get through life. You really can’t live life under a strict utilitarian approach or a strict deontological approach. If Midoriya hadn’t persisted against his classmates and the law to go save Bakugo, he WOULD have gotten kidnapped AGAIN. They were actively trying to take him with them. If Midoriya didn’t break the rules to save Kota, Kota would have straight up DIED. Muscular was actively trying to kill Kota, not to mention Kota had zero ways of defending himself. But here’s where I don’t think this is a fair comparison:

Hawks claims his killing of Twice was to save others. I don’t completely disagree with this logic, if the situation was more dire and dangerous for Hawks. The league was taking peoples’ lives. Somebody had to do something. The problem is that Twice was RUNNING AWAY when Hawks killed him. Twice wasn’t fighting Hawks back, he wasn’t endangering Hawks himself. Hawks stabbed him in the back. AND Hawks had Dabi to worry about, who was actively trying to attack Hawks. But Hawks chose to murder Twice instead of fending off Dabi. And if you refer back to the post I linked above about how it was a premeditated decision to kill Twice, you’ll see that Hawks had the capability of knocking Twice unconscious. He should have done this from the get go. And honestly? There are other heroes who could have captured Twice. There SHOULD have been other heroes to capture Twice. If Hawks was the only hope for the heroes in that war then jeez, the heroes suck at their jobs.

So TLDR for this question: Hawks’s circumstances were not drastic enough for him to be justified in killing Twice. As I said above, self-defense is one thing, where yes I could understand how if a life is lost while defending oneself is probably inevitable in some cases. But this wasn’t self defense. Twice was running away. Hawks should also be able to rely on his hero comrades to help him out.

Instead Hawks chose to be law-enforcement, judge, and executioner all in one moment.

I hope this answers your question? I tried my best. If I misunderstood or missed a talking point, feel free to shoot me a message or another ask.

Next question:

Believe me. I have thought about this! What about AFO? He’s human too isn’t he? You have a point. Should the restorative justice system extend to AFO? I would say yes. If I’m going to stick to my guns that the villains deserve restorative justice and not punitive justice, I should be fair and say it should extend to all villains.

The problem is not in the idea of exploring saving AFO, it’s just that there simply isn’t enough time to explore this in the story. If Horikoshi had said “I’m not going anywhere guys! We’re in this for the long haul!” I’d say it’s possible to explore that route. We don’t know anything about AFO except from what we’ve seen on screen, and what we’ve been told by All Might and the other OFA holders. Which still isn’t much to go on. You’re not giving AFO undue consideration. It’s definitely a deserved consideration. There are people in the story (and the real world) who may not be victimized in any way and end up being villains. Do they deserve a chance? I’d say yes. It’s in my nature as a social worker irl to give people the benefit of the doubt and give them a chance to learn. You’re right that in the end, the league being saved and the characters not considering what could have led AFO to villainy is just “skirting around the problem.” And honestly, that’s probably what we’re going to get. I wouldn’t be surprised for the thought to pass in Midoriya’s head. After saving somebody like Shigaraki, who everybody in the story (and many readers) considered to be “too far gone”, I wouldn’t be surprised at all if Midoriya entertained the thought for a brief moment. “What could have saved AFO from himself?” So honestly I don’t have an answer to this question that qualifies both sides. I can’t say that AFO is “too far gone” without undermining that fact that I never believed Shigaraki was “too far gone”, simply because we don’t get to decide what “too far gone” is. All I can say is that in the eyes of the story, there are far too many differences between AFO’s circumstances and Shigaraki’s circumstances to compare the two, and say they deserve the same type of sympathy from us readers.

Truly I have no sympathy for AFO, because the story doesn’t ask for it. The story wants sympathy for Shigaraki, Toga, Touya, Spinner, and even a tiiiiiny bit for Overhaul. It asks for NONE for AFO.

Another post I’ll link here that isn’t by me but by another awesome meta blogger (@hamliet) is this.

In a nutshell it says:

It’s not that AFO can’t be saved, it’s that he won’t. That’s the best answer I can give to that question honestly.

As for the third question:

That press conference was just...eh. I mean yeah, Endeavor not denying the allegations was good. Not that he really could anyway. It sucks for the rest of his family though. But at the same time Touya deserved his revenge, even though it was at the expense of his siblings and mother. It sucks, it’s a double edged sword because somebody is hurting no matter what was gonna happen. Endeavor was an asshole to that lady but I don’t really care too much. I’m really torn on what I think is going on inside Enji’s head because the Todofam is either extremely dense, or Horikoshi is writing their dialogue extremely vague on purpose to keep reader’s on the edge of their seats regarding what they want to do about Touya. I really don’t know. I’m not thrilled with the way the Todofam plot is being written right now, even though I’m 100% sure Touya is going to get his happy ending. But right now anything to do with the Todofam that isn’t Shoto and Touya just bothers me. I don’t think Enji really understands yet what he has to do for Touya. Yes he recognizes that he has to atone, but he’s not recognizing HOW he has to atone. Right now he’s still stuck in that “I have to be a hero to absolve my crimes against my family” headspace and I don’t think he’s going to get out of that headspace until he comes face to face with his son and realizes that he can’t just fight villains and go home to a happy family that he terrorized for 20 years. He’s going to have to let his family go, let them decide when to let him back in, if they ever do (I think they will just because of the way the story is being written.) As a reader, Enji is just a character that I cannot vibe with, no matter what happens. I definitely appreciate his role in the story. His role is vital to Touya’s saving and redemption. Touya is in my top 3 favorite characters from this series and I’m emotionally invested. So while I appreciated Enji’s role in the story, I don’t like his character or anything to do with him, at least until it comes time to help save his son. Also the trio of Hawks, Best Jeanist, and Enji just gives me major back the blue vibes and I just can’t read their chapters and be in a good mood lol.

Thank you for the ask! I hope I answered everything! This was fun to answer!

#bnha#bnha asks#ask haleigh#i guess that's what i'll call my ask tag lmao#boku no hero academia#bnha 306#mha 306#my hero academia#todofam#todoroki shoto#todoroki touya#todoroki enji#bnha endeavor#hawks#best jeanist#tomura shigaraki#shigaraki tomura#tenko shimura#shimura tenko#afo#all for one

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Standards of Feminist Conduct

Violence against women is a permanent feature of all capitalist societies, including US capitalist society. It is one of the most abhorrent aspects of patriarchy, the evil institution of women’s oppression. Patriarchy in the US has its own specific characteristics that are particular to capitalism, such as the widespread commodification of women. The term “commodification” refers to the transformation of women by the capitalists into objects for sale, a process in which ordinary men also participate.

Violence against women also shows up within self-proclaimed revolutionary organizations and revolutionary movements in the US. This includes rape, sexual assault, sexual harassment, unwanted sexual pressure, other forms of physical and verbal abuse, and other forms of violation of consent. Recently, two major Trotskyist organizations, one in Britain [1] and one in the US [2], were rightly subjected to public exposure and condemnation for the liberalism (meaning the unprincipled lack of struggle) of their members in failing to oppose rape culture.

Another communist organization in the US was also exposed less than a year ago for sheltering a rapist member, disciplining him by merely having him write an essay for “self-criticism.” [3] At the height of the Occupy movement, there were accounts of sexual assault at protest camps in New York, Cleveland, Dallas, Baltimore, Lawrence, Portland, New Hampshire, and Glasgow. [4] It is also well known that rape culture is widespread among anarchist collectives and the broader anarchist milieu. [5] For every revolutionary organization and trend, the same question of women’s emancipation is on the table: which side are you on?

This is one of the most important political questions that must be resolved today for the revolutionary movement to move forward. In certain specific circumstances, it is the single most important political question. The fact that there is increasing debate on this question and growing disorder within the ranks of organizations is a good thing that must be encouraged to develop further. There needs to be more of it: more debate, more disorder, more turmoil, and more people raising their voices. Some have pointed out the causal link between the British Trotskyists’ class reductionist line and male chauvinist practice.

Others have highlighted the weak organizational forms of anarchists and their employment of “accountability processes” guided by “restorative justice” frameworks that very often turn out to be shams for the women involved. [6] However, this is too simple of an understanding of the problem if left at this level. In reality, violence against women within revolutionary organizations and revolutionary movements is a phenomenon with a wide expanse. It is not narrowly rooted in any specific trend.

No ideology or -ism will make an organization immune from this problem. There will be groups and individuals claiming all sorts of political positions who at the same time always relegate women’s emancipation to a secondary and unimportant place, or combine feminist discourse with male chauvinist conduct. Therefore, the most important question here is how an organization addresses the problem of violence against women when it arises in practice, as chances are it will at some point within its ranks. Certain guiding principles can be derived from the positive aspects of the Leninist-Comintern historical experience and from the comprehensive whole of today’s ideology of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.

Maoism must be emphasized here, because of its breakthroughs in developing the trend of proletarian feminism and on the organizational question. Proletarian feminism is a trend of women’s emancipation generated in practice out of the Maoist-led People’s Wars and revolutionary mass movements around the world. [7] The Maoist party concept is also something fundamentally new in its nature and methods of work. [8] The guiding principles outlined here should determine the formulation of organizational policies in the US on anti-women violence. Without the correct policies based on the correct principles, revolutionary organizations in the US will never be able to organize increasing numbers of women as militants and leaders, as they have so far failed to do in the way that history demands of us.The domination of the NGO opportunists and their petty-bourgeois identity politics will remain uncontested. The masses of proletarian women will be left to follow the leadership of different non-proletarian trends, without the weapon of independent class politics.

1. Revolutionary organizations, if they are genuine, must automatically expel any member who engages in anti-women violence and abuse. Organizations that fail to do this cannot be taken seriously and must be publicly exposed for their liberalism in failing to oppose male chauvinism. The “restorative justice” framework and the “accountability process” used by anarchists and other activists more often than not merely reproduce in practice the dynamics of patriarchy.

For Marxist-Leninists, “rectification” and “criticism / self-criticism,” without a policy of expulsion, often becomes the same liberal process with a different name. In contrast, zero tolerance for male chauvinist violence and abuse must be the principle, meaning automatic expulsion and, depending on the circumstances, public exposure. This is the only way to forge organizations that are developing the actuality of women’s emancipation, not just talking about it as an appealing idea.

2. During investigations by an organization in the US into incidents of anti-women violence and abuse, the word of the victim alleging that violence and abuse has been committed against them must be given more weight than the word of the accused. If there is a factual dispute, the guiding principle must be to adopt policies and enact decisions based principally on the victim’s account of events. Victims of domestic violence often have their reality denied or manipulated consistently by their abusers.

This must be taken into account when investigating the facts and when coming to a decision about the accused. The revolutionary organization in the US, which is not a court of justice with a court’s material powers of investigation and presumptions, cannot allow the accused to simply deny the victim’s account in part or wholesale, call into question the victim’s motives, and mobilize their social network to pressure the victim and the organization.

Revolutionary organizations in the US are not states making decisions on punishment and rehabilitation, which would operate according to different standards. They are voluntary associations that must make a call – generally based on limited and conflicting verbal or written accounts – on how to respond to an incident, taking into consideration the need to advance the struggle for women’s emancipation, to develop women as militants and leaders, and to protect the organization’s work and reputation.

3. Rectification of individuals who have engaged in anti-women violence must be encouraged, but can take place only after their expulsion from the ranks of an organization, as a condition of re-admission at a future time. Certain acts, such as rape or sexual assault, must result in a lifetime ban without question. For organizations struggling in the imperialist countries, the Communist Party USA’s expulsion, subsequent mass public trial in 1931, and eventual rectification of Yokinen, a Finnish CPUSA member who denied several African Americans entry to a dance at the Finnish Workers Club in Harlem, remains the best example in the US of what a successful rectification process looks like in practice, in this case for white chauvinist conduct. [9]

Rectification in this regard does not mean uttering some words in an organizational meeting, writing an apology essay, engaging in mediation, participating in accountability circles or victim impact panels, or getting counseling and treatment. Are white chauvinists supposed to be counseled and treated as well? Rectification means conducting self-criticism widely before the masses, submitting the fullest account of one’s conduct and history to public scrutiny, and following through on a course of political activity of struggle against women’s oppression, which must include ongoing transformation of the individual person, similar to what Yokinen successfully carried out under the leadership of the CPUSA.

Recognizing that there is no organization in the US today with the necessary base, prestige among the masses, and scale to conduct such a process means that in the current objective and subjective conditions, successful rectification of individuals for male chauvinism should generally be pursued, but will inevitably continue to be the exception rather than the rule. The most important thing is to struggle against the small-group dynamics that are a soil for male chauvinism and prevent the organization of women. Violence against women will not end without the organization of women.

4. The ideological and political line of a revolutionary organization might be outlined in its documents, but ultimately becomes a material force among the masses only through the conduct and actions of its members. This is one of the new contributions of the Maoist party concept, which emphasizes the importance of revolutionary attitudes among the cadres. Revolutionary organizations must instill in members the need to practice the constant remolding of their thinking and actions to create the actuality of women’s emancipation.

5. Putting the proletarian feminist line in command requires a continuous engagement in criticism and self-criticism, or CSC. CSC in this particular instance involves studying the concept and history of patriarchy, discussing its manifestations in thinking, conduct, and actions through facilitated group settings, and coming to collective decisions on how to fight it. At the same time, CSC that takes place without an existing policy of expulsion for male chauvinist violence and abuse ends up being a toothless ritual that paralyzes rather than strengthens organization. The party building movement of the last phase, the 1960s and the 1970s, largely failed the masses of toiling women in this country.

Those who imagine that a communist organization with proletarian feminist politics at its core can be built or that a revolutionary proletarian feminist movement can be developed today from the ground up – without first confronting the pressing issue of male chauvinism in the existing organizations and circles, including determining the proper guiding principles and policies to do this – are thoroughly deluding themselves. This view amounts to the liquidation of the struggle for women’s emancipation and a kind of economism that refuses to address the real political question at hand of the involvement of women in organizations. We welcome dialogue with feminist-oriented collectives and individuals who are working on this issue in practice and interested in mutual learning through the discussion of organizational principles and policies.

Center for Marxist Leninist-Maoist Studies 16/8/2013

Endnotes

1. Shiv Malik and Nick Cohen, “Socialist Workers Party leadership under fire over rape kangaroo court,” guardian.co.uk, March 9, 2013. (http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/mar/09/socialist-workers-party-rape-kangaroo-court).

2. “Rape, Sexual Assault, and the U.S. Socialist Organization Solidarity.” (http://www.thenorthstar.info/?p=9350).

3. For more information, see the blog Necessary Means: Confronting patriarchal violence. (http://necessarymeansfight.blogspot.com/).

4. “Occupy Wall Street: How About We Occupy Rape Culture?” (http://persephonemagazine.com/2011/11/04/occupy-wall-street-how-about-we-occupy-rape-culture/).

5. See, for example, Betrayal: A critical analysis of rape culture in anarchist subcultures, Words to Fire Press (“It would seem that throughout the anarchist milieu, wherever you turn, there is a community being ravaged by rape, by sexual assault, and by abuse.”).

6. Ibid. (“[T]internal workings of the accountability process itself have the potential to be hijacked and used against a survivor. … In some cases [perpetrators] are allowed to make demands of the survivor or else place criteria on their own participation. Perpetrators, or their apologists, all too commonly respond to being called out by making defensive ‘callouts’ of their own. As discussed earlier, they will accuse the survivor of any wrongdoing they can think of, or else make some up when actual misdeeds are not forthcoming. Rather than recognize these pathetic attempts at slander as the manipulative transgressions they are, the false supporters usually join the perpetrator in absurd calls for ‘accountability’ from the survivor. From this newfound position of righteousness, and with the complicity of the false supporters, the perpetrator is free to alter the very character of the accountability process.

What began as a callout becomes more like a negotiation, as a perpetrator’s cooperation becomes contingent on the survivor addressing their concerns. Perhaps some of these concerns might even be valid, but of course what’s important is not their validity but their role in undermining the survivor’s struggle. The survivor must now earn not only the accountability they get from the perpetrator, but also the support they get from the community. Those survivors who are unwilling or unable to jump through all the hoops will be written off. In a final perversion of the accountability process, the survivor will be the one blamed for its failure, the one who was unwilling to ‘work things out’. By this point the so-called ‘Restorative Justice’ framework has been so distorted that it succeeds only in ‘restoring’ the power dynamics of a Rape Culture which had been otherwise compromised by the survivors’ struggle.”).

7. See, for example, Avanti, “Philosophical Trends in the Feminist Movement.”

8. See, for example, Ajith, “The Maoist Party.”

9. Harry Haywood, “The Struggle for the Leninist Position on the Negro Question in the United States,” The Communist, September 1933, available at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/haywood/1933/09/x01.htm.

#proletarian feminism#marxism#maoism#marxism-leninism-maoism#abuse#male chauvinism#violence#communism

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

An easy thing to do in order to decrease America’s massive prison population would be to just reduce the length of sentences. But I can already tell how controversial that would be. My perception is that the overwhelming public idea of what prison is For is either to exact vengeance on someone for the damage they did or to get a dangerous person “off the streets” for as long as the law will allow. It’s very difficult for anyone in America to think of prisons as places where people are rehabilitated because anyone who knows the slightest thing about how prisons work probably feel like a lot of things about prison actively work against people who are trying to make themselves better.

I don’t know. It is a common thing to frame vengeance as justice and I don’t agree with that. Justice is punishing the guilty and that’s it? Justice is locking people up? Justice in America is so rarely about helping the people who were hurt, and even when it is it’s almost exclusively in a monetary way.

Say someone steals something. Say they are caught and convicted and they have to give it back. Fine. Then say they are sentenced to a prison term. Why? No really, why? To think about what they did? To make them a better person? Is prison really the best way to do that? Do we have to rip people out of their communities in order to ask them to genuinely reflect on how their actions might be hurting others? Can’t we find a better way to do that than by doing something to them that will profoundly fuck up their life for much longer than just the prison term itself?

Who is helped by this? Who is healed? Is the community really made better by this? Is the community really safer now? Is it safer in the long run?

What happens when that person gets out of prison? Don’t many released prisoners find that their criminal record and indeed even just the gap in their employment history make it harder to get a job? Might this drive this person to a place of economic desperation? Might they be driven to steal again out of sheer need?

We all need to ask ourselves these questions and really reflect on them. We all need to research concepts of restorative justice practices and compare those to the current system. We need to really reflect on that too.

And then, if we decide that the best way going forward is to stop sentencing people to prison or at least, to start out with, to stop setting prison terms for most crimes that had prison terms before...we have a terrible uphill battle against some of the most powerful people in the country, who are sometimes among the most powerful people in the world. And we have to be ready for that.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Series Review Pt. 3/3

Part One

Part Two

All right, last one!

One of the things about adults is that most become increasingly less flexible the older they get. They learn to function in a certain way to get certain results and work themselves into a pattern that inhibits their ability to be creative or dynamic which is compounded the less they are challenged. This isn’t opinion - this has been a scientifically and statistically verified fact. Different levels of physical and emotional development fundamentally changes the way human beings process stimuli and conflict, and factors like physical injuries and trauma affect the ability of one to process and resolve stressful situations. This doesn’t mean adults can’t change the way they think or do things, but it’s much harder for them to mentally and emotionally break out of their preconceived notions unprompted whereas younger adults still largely maintain the ability to criticize and adjust changes in perspective and creatively adapt to new information.

The kids we see in HeroAca are in a particularly unique situation in regards to coming from a background of ideals (“If I work hard, I’ll see the fruits of my labor”) and coming to grips with the inherently unfair nature of the world (“Even the greatest hero can’t save everyone”). Combined with the early exposure they’ve had to the injustices in their society and their general disposition to maximize the positive impact they have on others the “next generation of heroes” is in a unique situation to completely overhaul the current system literally as they enter it by bringing in new ideals and embracing their diversity in thought and background to directly challenge failings in the old system as well as bring awareness to those who exist outside it. With an added sense of camaraderie and teamwork over rivalry they have the ability to foster more “human” conversations with the aim of improving the world as opposed to being purely focused on “business” when in uniform the way their predecessors were.

This isn’t to say that the grown heroes of the series have to be completely done away with, just that they have not had a generation so able to challenge them to action in the way their juniors do now. In fact, it’s a running theme in the series that the next generation of heroes either teach or save their mentors in unexpected ways and with varying degrees of intensity as they work through adversity together.

Red Riot has not only saved Fatgum in a literal sense in the battle with the Shie Hassaikai, but Fatgum explicitly states he underestimated the ability and resolve of the young hero. He also holds faith in his older mentee, Sun Eater, whom he regards as a hero unrivaled in ability in the current climate if he only could overcome his own self-doubt. Sir Nighteye’s confidence in Lemillion is evident from the start and to his dying breath believes the key to his ability to save is not rooted in the strength of his quirk but by his ability to make others smile. Nighteye’s previous disdain of Deku is eventually turned into awe and inspiration when he’s able to do what was previously thought to be impossible and theoretically change destiny itself. All Might’s faith in Deku has also been immediately obvious, but seeing that his symbolic value with the next generation as a hero hasn’t depreciated with his declining ability has given him the resolve to fight for his own survival again. Bakugo in particular has received a new, special place in his heart as a capable hero who together with Deku represents his two separate but related core values in a hero - winning and saving - but with greater potential then All Might was able to achieve alone. Shinsou has served as a personal means for Eraserhead to move past the trauma of violently losing his childhood friend and begin to truly encourage the next generation to accept the risk inherent in this line of work instead of letting his fears inhibit his ability to teach and mentor them. Shouto has been a catalyst for Endeavor to seek to restore to his family what he took away from them and to recognize that he can never fully restore or erase the trauma he inflicted on them nor does he have any right to ask to be included in their lives any further. Even straightforward, straight-laced Tsukoyomi has inspired Hawks to take a second look at what it means to raise up the next generation of heroes outside of his own troubled past with it to the point he now actively encourages and genuinely believes in them as a whole to possess the power to make changes he couldn't.

These conversations have largely not happened with the criminal side of the field as any opportunity for the children to touch the hearts of villains have been marred by the inherent life-or-death struggle of each encounter. Each side is literally too busy fighting for survival/victory to truly have some of these meaningful conversations, but the seeds they’ve planted in the hearts of their mentors as well as the rare heart-to-heart interactions they’ve had with villains have proven they have power; and that’s going to be the deciding factor in this literal war at the end of the manga - that is, this missing piece is going to be an opportunity for the heroes to save the hearts of the villains.

The key to this next generation “saving” an army of villains will be dependent on their ability to advocate for rehabilitation and reintegration into society - both for villains to accept the help and for broader society being willing to forgive them. Hawks has already started with his personal offer to help Twice, but it will be interesting to see how others are able to input offers for reform in the heat of battle and in light of their individual circumstances.

An example I hope we’ll get to see is an interaction between Dabi, Endeavor, and Shouto (assuming, of course, that Dabi is a Todoroki). Shouto would be the main deciding factor in the altercation as he has undergone the same kind of abuse and personal tragedy at the hand of Endeavor as Dabi has; but the outcome was completely different and he therefore may be able to speak to Dabi in a way that Endeavor definitely cannot. Shouto made the personal choice to not let his hatred for his father consume him and instead channeled the resources available to him to become a hero capable of saving others because he determined in and of himself to do so, rather than becoming a person obsessed with personal vengeance or merely operating as his father’s vicarious victory. It’s important to remember that Shouto has looked to the ideals of heroism (mainly through his admiration of All Might) as a good thing from a young age, but those ideals were overshadowed in the face of the constant abuse in his home and he became more and more cynical over time. As he began to accept that he was not bound by the burden of his upbringing and was capable of moving past the trauma to determine his own future despite it, he was not only able to change his entire outlook on his future for his own sake; but Shouto even began to cause Endeavor to reexamine the ethics and consequences of his actions even without the forgiveness of his family simply by operating as the kind of hero Shouto wanted to be for himself instead of the hero Endeavor tried to force upon him.

In this light, Dabi’s personal vendetta is clarified to not be the pursuit of justice but a mere act of vengeance with understandable motivation but ultimately evil justification that has not only failed to constructively address the issue of neglect and abuse in his own home, let alone of hero families as a whole, but has caused undeserved collateral death and grief in the process. Whether this revelation will “save” Dabi is unknown as Shouto and Natsuo also still hold deep contempt for their father; but both of them have begun to move past the events of their childhood (if only in very small steps) and have begun to self-determine their relationship with their father individually, while Dabi is still operating out of pure spite. Interestingly, what we may end up seeing in this situation is a schism resulting in a fight similar to the final showdown between Zuko and Azula in Avatar: the Last Airbender. (And on that note, I don’t know how I didn’t notice the additional parallels between the families sooner between the scar, paternal abuse resulting in an estranged mother, and sibling with blue fire. I called Todoroki Frosty Fire Prince Zuko in the past as a joke, but this feels so obvious now; I’ve clearly been sleeping.) One more wild card thrown in will be if Hawks is present for this interaction and seeing his reaction to it as he will fight Dabi and has a similar story to both him and Shouto.

Where kids like Bakugo and Deku will be most relevant or impactful is not quite clear at the moment, though a clash with Shigaraki feels imminent. We do know at least that each are counted as capable heroes in their own rights with the distinction that Bakugo is a hero who wins fights and Deku is a hero who saves people so their role might look like something along the lines of Bakugo ending a battle and Deku ending the underlying conflict. There seems to be an insinuation that these two things rarely can be done at the same time, and that first the physical threat must be addressed before a sit-down and exchange can be made to talk about the motivations and underlying causes of the fight. Much like with the final fight with Overhaul, Eri was not considered to be completely saved until after she was removed from her situation and then allowed to heal - and even that process is ongoing.

If the heroes are able to refute the viewpoints of the villains at the end of the day and are able to truly move the public on their behalf, those who chose to cooperate will likely be given the chance to start over while those who continue to fight out of spite will be at best detained and at worst killed in the struggle. What this might look like, I’m not sure, as some have hefty crimes to answer for and may not have the opportunity to truly reintegrate. Any country/society/culture with as many people committing as severe crimes as these would have difficulty embracing change that would welcome these people back, let alone the specific context of Japan that brutally punishes criminals and so often permanently damages their reputations and social standing - sometimes for what many would consider only “minor” crimes. Nevertheless, it doesn’t mean that there isn’t hope for even the worst of them with a proper change of heart; and the fact that the Meta Liberation Army was as widespread a cultural phenomena as it was offers the idea that enough people are open to the ideas of the radical shifts necessary to address these concerns which increases the chance to make reforms peacefully.

As a focus point, consider Shigaraki. He’s the most important villain to reach not only as the head of this massive villain organization but as a dire victim of the current system’s shortcomings. His own biggest quarrel with hero society as it stands is that it makes people overconfident and apathetic because there's always a hero just around the corner - let them handle this person in need. While Shigaraki is not advocating for individual moral responsibility, a new societal emphasis on it could resolve most of the issues he has with hero society. A big enough cultural shift could also address instances of criminal activity on a case by case basis - a new focus that hurt people lashing out isn't acceptable behavior, but perhaps some other response than immediate punishment should be considered; as well as reconsider the role of the current justice system in the progressive intensity over a person’s criminal history to mitigate these problems before they manifest.

Right now what's holding up Shigaraki's power over others (outside of the terror he inspires) is the support of others predicated on a lie - and this goes both for the League and the PLF. If that lie is exposed, Shigaraki could wind up high, dry, and unsupported - vulnerable - depending on how individuals take the revelation. He does seem to genuinely care for the core members of the League, and their loyalty to him is undeniably profound and far reaching. Despite his nihilism, at the end of the day he’s still a deeply wounded and angry individual looking in extremes for some solace in the injustice of a world that rejected him. There are many ways this can go depending on who faces who in the final showdowns to come; but for that we'll have to wait and see.

If someone as far gone as Shigaraki can be saved then there's a bright future out there for everyone if they are willing to reach out together and grab it.

This review has left out many aspects of the story I reviewed as important but not necessary for this article, and at some 5k words that's probably for the best. Too much speculation at the moment doesn't feel very productive outside of how general themes and plotlines will tie up at the end, but I'll have to save some of those specifics for some other time. Thank you for sticking out with me this far, and thank you again to @baezetsu and @dorito9708 for helping me review and edit all this information!

9 notes

·

View notes

Note