#Digital copyright and AI training

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I came across this post on my tumblr feed from a digital painting artist I follow, and it just reminded me on how difficult it is already to be a professional artist in today’s world. On top of that there’s the issue of AI artwork being created and sold by a surplus of non-artists everywhere now. These people are also harping on actual visual artists, who have real talent and skill, accusing their art to be AI generated. I bet you my right hand that they’re just trying to create a legit reason to sell other artist’s artwork to make “illegal” profit off them. So freak’n Aggravating!!! 🤬

Sorry, it just ridiculously irks me! Being a visual artist, myself, I can totally understand and relate to the situation. Professional artists who trained in the arts or even self-taught talents, shouldn’t be dealing with this kind of harassment. AI Art technology is been greatly abused all over the world, and it should not be tolerated. 😠🎨

Okay so for the last month or so, I’ve gotten 6 dm’s mostly from tumblr accusing me of using ai, asking for prompts for my style, etc. And a random 1 star review on my online store saying my prints are ai.

Guys.

If you do literally 10 seconds of research you’d get your answer.

I post process images/videos on the regular. I plop unfinished things on patreon and ko-fi on the regular. There’s like books and whatever else out there that I drew that’ve existed way before august 2022.

Heck I’m doing real physical paintings now with a partial reason being to show that a person is making these things.

I know these are just low effort drive-by’s but it’s starting to get annoying. Please just, idk, Google a persons name or scroll for like 5 more seconds and you’ll be able to figure it out.

#ai artwork#ai art#ai generated#ai imagery#anti-abuse#anti-harassment#art#artwork#real artists#trained artists#professional artists#copyrighted#legal protection#social media#scammers#hackers#selling ai art#Illegal#visual artist#digital artists#copyright#protect artists#frustrating#people’s greed#easy cash#stop this now

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Denas Grybauskas, Chief Governance and Strategy Officer at Oxylabs – Interview Series

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/denas-grybauskas-chief-governance-and-strategy-officer-at-oxylabs-interview-series/

Denas Grybauskas, Chief Governance and Strategy Officer at Oxylabs – Interview Series

Denas Grybauskas is the Chief Governance and Strategy Officer at Oxylabs, a global leader in web intelligence collection and premium proxy solutions.

Founded in 2015, Oxylabs provides one of the largest ethically sourced proxy networks in the world—spanning over 177 million IPs across 195 countries—along with advanced tools like Web Unblocker, Web Scraper API, and OxyCopilot, an AI-powered scraping assistant that converts natural language into structured data queries.

You’ve had an impressive legal and governance journey across Lithuania’s legal tech space. What personally motivated you to tackle one of AI’s most polarising challenges—ethics and copyright—in your role at Oxylabs?

Oxylabs have always been the flagbearer for responsible innovation in the industry. We were the first to advocate for ethical proxy sourcing and web scraping industry standards. Now, with AI moving so fast, we must make sure that innovation is balanced with responsibility.

We saw this as a huge problem facing the AI industry, and we could also see the solution. By providing these datasets, we’re enabling AI companies and creators to be on the same page regarding fair AI development, which is beneficial for everyone involved. We knew how important it was to keep creators’ rights at the forefront but also provide content for the development of future AI systems, so we created these datasets as something that can meet the demands of today’s market.

The UK is in the midst of a heated copyright battle, with strong voices on both sides. How do you interpret the current state of the debate between AI innovation and creator rights?

While it’s important that the UK government favours productive technological innovation as a priority, it’s vital that creators should feel enhanced and protected by AI, not stolen from. The legal framework currently under debate must find a sweet spot between fostering innovation and, at the same time, protecting the creators, and I hope in the coming weeks we see them find a way to strike a balance.

Oxylabs has just launched the world’s first ethical YouTube datasets, which requires creator consent for AI training. How exactly does this consent process work—and how scalable is it for other industries like music or publishing?

All of the millions of original videos in the datasets have the explicit consent of the creators to be used for AI training, connecting creators and innovators ethically. All datasets offered by Oxylabs include videos, transcripts, and rich metadata. While such data has many potential use cases, Oxylabs refined and prepared it specifically for AI training, which is the use that the content creators have knowingly agreed to.

Many tech leaders argue that requiring explicit opt-in from all creators could “kill” the AI industry. What’s your response to that claim, and how does Oxylabs’ approach prove otherwise?

Requiring that, for every usage of material for AI training, there be a previous explicit opt-in presents significant operational challenges and would come at a significant cost to AI innovation. Instead of protecting creators’ rights, it could unintentionally incentivize companies to shift development activities to jurisdictions with less rigorous enforcement or differing copyright regimes. However, this does not mean that there can be no middle ground where AI development is encouraged while copyright is respected. On the contrary, what we need are workable mechanisms that simplify the relationship between AI companies and creators.

These datasets offer one approach to moving forward. The opt-out model, according to which content can be used unless the copyright owner explicitly opts out, is another. The third way would be facilitating deal-making between publishers, creators, and AI companies through technological solutions, such as online platforms.

Ultimately, any solution must operate within the bounds of applicable copyright and data protection laws. At Oxylabs, we believe AI innovation must be pursued responsibly, and our goal is to contribute to lawful, practical frameworks that respect creators while enabling progress.

What were the biggest hurdles your team had to overcome to make consent-based datasets viable?

The path for us was opened by YouTube, enabling content creators to easily and conveniently license their work for AI training. After that, our work was mostly technical, involving gathering data, cleaning and structuring it to prepare the datasets, and building the entire technical setup for companies to access the data they needed. But this is something that we’ve been doing for years, in one way or another. Of course, each case presents its own set of challenges, especially when you’re dealing with something as huge and complex as multimodal data. But we had both the knowledge and the technical capacity to do this. Given this, once YouTube authors got the chance to give consent, the rest was only a matter of putting our time and resources into it.

Beyond YouTube content, do you envision a future where other major content types—such as music, writing, or digital art—can also be systematically licensed for use as training data?

For a while now, we have been pointing out the need for a systematic approach to consent-giving and content-licensing in order to enable AI innovation while balancing it with creator rights. Only when there is a convenient and cooperative way for both sides to achieve their goals will there be mutual benefit.

This is just the beginning. We believe that providing datasets like ours across a range of industries can provide a solution that finally brings the copyright debate to an amicable close.

Does the importance of offerings like Oxylabs’ ethical datasets vary depending on different AI governance approaches in the EU, the UK, and other jurisdictions?

On the one hand, the availability of explicit-consent-based datasets levels the field for AI companies based in jurisdictions where governments lean toward stricter regulation. The primary concern of these companies is that, rather than supporting creators, strict rules for obtaining consent will only give an unfair advantage to AI developers in other jurisdictions. The problem is not that these companies don’t care about consent but rather that without a convenient way to obtain it, they are doomed to lag behind.

On the other hand, we believe that if granting consent and accessing data licensed for AI training is simplified, there is no reason why this approach should not become the preferred way globally. Our datasets built on licensed YouTube content are a step toward this simplification.

With growing public distrust toward how AI is trained, how do you think transparency and consent can become competitive advantages for tech companies?

Although transparency is often seen as a hindrance to competitive edge, it’s also our greatest weapon to fight mistrust. The more transparency AI companies can provide, the more evidence there is for ethical and beneficial AI training, thereby rebuilding trust in the AI industry. And in turn, creators seeing that they and the society can get value from AI innovation will have more reason to give consent in the future.

Oxylabs is often associated with data scraping and web intelligence. How does this new ethical initiative fit into the broader vision of the company?

The release of ethically sourced YouTube datasets continues our mission at Oxylabs to establish and promote ethical industry practices. As part of this, we co-founded the Ethical Web Data Collection Initiative (EWDCI) and introduced an industry-first transparent tier framework for proxy sourcing. We also launched Project 4β as part of our mission to enable researchers and academics to maximise their research impact and enhance the understanding of critical public web data.

Looking ahead, do you think governments should mandate consent-by-default for training data, or should it remain a voluntary industry-led initiative?

In a free market economy, it is generally best to let the market correct itself. By allowing innovation to develop in response to market needs, we continually reinvent and renew our prosperity. Heavy-handed legislation is never a good first choice and should only be resorted to when all other avenues to ensure justice while allowing innovation have been exhausted.

It doesn’t look like we have already reached that point in AI training. YouTube’s licensing options for creators and our datasets demonstrate that this ecosystem is actively seeking ways to adapt to new realities. Thus, while clear regulation is, of course, needed to ensure that everyone acts within their rights, governments might want to tread lightly. Rather than requiring expressed consent in every case, they might want to examine the ways industries can develop mechanisms for resolving the current tensions and take their cues from that when legislating to encourage innovation rather than hinder it.

What advice would you offer to startups and AI developers who want to prioritise ethical data use without stalling innovation?

One way startups can help facilitate ethical data use is by developing technological solutions that simplify the process of obtaining consent and deriving value for creators. As options to acquire transparently sourced data emerge, AI companies need not compromise on speed; therefore, I advise them to keep their eyes open for such offerings.

Thank you for the great interview, readers who wish to learn more should visit Oxylabs.

#Advice#ai#AI development#ai governance#AI industry#AI innovation#AI systems#ai training#AI-powered#API#approach#Art#Building#Companies#compromise#content#content creators#copyright#course#creators#data#data collection#data protection#data scraping#data use#datasets#deal#developers#development#Digital Art

0 notes

Note

On that recent Disney Vs Midjourney court thing wrt AI, how strong do you think their case is in a purely legal sense, what do you think MJ's best defenses are, how likely is Disney to win, and how bad would the outcome be if they do win?

Oh sure, ask an easy one.

In a purely legal sense, this case is very questionable.

Scraping as fair use has already been established when it comes to text in legal cases, and infringement is based on publication, not inspiration. There's also the question of if Midjourney would be responsible for their users' creations under safe harbor provisions, or even basic understanding of what an art tool is. Adobe isn't responsible for the many, many illegal images its software is used to make, after all.

The best defense, I would say, is the fair use nature of dataset training and the very nature of transformative work, which is protected, requires the work-to-be-transformed is involved. Disney's basic approach of 'your AI knows who our characters are, so that proves you stole from us' would render fair use impossible.

I don't think its likely for Disney to win, but the problem with civil action is proof isn't needed, just convincing. Bad civil cases happen all the time, and produce case law. Which is what Disney is trying to do here.

If Disney wins, they'll have pulled off a coup of regulatory capture, basically ensuring that large media corporations can replace their staff with robots but that small creators will be limited to underpowered models to compete with them.

Worse, everything that is a 'smoking gun' when it comes to copyright infringement on Midjourney? That's fan art. All that "look how many copyrighted characters they're using-" applies to the frontpage of Deviantart or any given person's Tumblr feed more than to the featured page of Midjourney.

Every single website with user-generated content it chock full of copyright infringement because of fan art and fanfic, and fair use arguments are far harder to pull out for fan-works. The law won't distinguish between a human with a digital art package and a human with an AI art package, and any win Disney makes against MJ is a win against Artstation, Deviantart, Rule34.xxx, AO3, and basically everyone else.

"We get a slice of your cheese if enough of your users post our mouse" is not a rule you want in law.

And the rules won't be enforced by a court 9/10 times. Even if your individual work is plainly fair use, it's not going to matter to whatever image-based version of youtube's copyreich bots gets applied to Artstation and RedBubble to keep the site owners safe.

Even if you're right, you won't have the money to fight.

Heck, Adobe already spies on what you make to report you to the feds if you're doing a naughty, imagine it's internal watchdogs throwing up warnings when it detects you drawing Princess Jasmine and Ariel making out. That may sound nuts, but it's entirely viable.

And that's just one level of possible nightmare. If the judgement is broad enough, it could provide a legal pretext for pursuing copyright lawsuits over style and inspiration. Given how consolidated IP is, this means you're going to have several large cabals that can crush any new work that seems threatening, as there's bound to be something they can draw a connection to.

If you want to see how utterly stupid inspiration=theft is, check out when Harlan Ellison sued James Cameron over Terminator because Cameron was dumb enough to say he was inspired by Demon with a Glass Hand and Soldier from the Outer Limits.

Harlan was wrong on the merits, wrong ethically, and the case shouldn't have been entertained in the first place, but like I said, civil law isn't about facts. Cameron was honest about how two episodes of a show he saw as a kid gave him this completely different idea (the similarities are 'robot that looks like a guy with hand reveal' and 'time traveling soldier goes into a gun store and tries to buy future guns'), and he got unjustly sued for it.

If you ever wonder why writers only talk about their inspirations that are dead, that's why. Anything that strengthens the "what goes in" rather than the "what goes out" approach to IP is good for corps, bad for culture.

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a product demo last week, OpenAI showcased a synthetic but expressive voice for ChatGPT called “Sky” that reminded many viewers of the flirty AI girlfriend Samantha played by Scarlett Johansson in the 2013 film Her. One of those viewers was Johansson herself, who promptly hired legal counsel and sent letters to OpenAI demanding an explanation, according to a statement released later. In response, the company on Sunday halted use of Sky and published a blog post insisting that it “is not an imitation of Scarlett Johansson but belongs to a different professional actress using her own natural speaking voice.”

Johansson’s statement, released Monday, said she was “shocked, angered, and in disbelief” by OpenAI’s demo using a voice she called “so eerily similar to mine that my closest friends and news outlets could not tell the difference.” Johansson revealed that she had turned down a request last year from the company’s CEO, Sam Altman, to voice ChatGPT and that he had reached out again two days before last week’s demo in an attempt to change her mind.

It’s unclear if Johansson plans to take additional legal action against OpenAI. Her counsel on the dispute with OpenAI is John Berlinski, a partner at Los Angeles law firm Bird Marella, who represented her in a lawsuit against Disney claiming breach of contract, settled in 2021. (OpenAI’s outside counsel working on this matter is Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati partner David Kramer, who is based in Silicon Valley and has defended Google and YouTube on copyright infringement cases.) If Johansson does pursue a claim against OpenAI, some intellectual property experts suspect it could focus on “right of publicity” laws, which protect people from having their name or likeness used without authorization.

James Grimmelmann, a professor of digital and internet law at Cornell University, believes Johansson could have a good case. “You can't imitate someone else's distinctive voice to sell stuff,” he says. OpenAI declined to comment for this story, but yesterday released a statement from Altman claiming Sky “was never intended to resemble” the star, adding, “We are sorry to Ms. Johansson that we didn’t communicate better.”

Johansson’s dispute with OpenAI drew notice in part because the company is embroiled in a number of lawsuits brought by artists and writers. They allege that the company breached copyright by using creative work to train AI models without first obtaining permission. But copyright law would be unlikely to play a role for Johansson, as one cannot copyright a voice. “It would be right of publicity,” says Brian L. Frye, a professor at the University of Kentucky’s College of Law focusing on intellectual property. “She’d have no other claims.”

Several lawyers WIRED spoke with said a case Bette Midler brought against Ford Motor Company and its advertising agency Young & Rubicam in the late 1980s provides a legal precedent. After turning down the ad agency’s offers to perform one of her songs in a car commercial, Midler sued when the company hired one of her backup singers to impersonate her sound. “Ford was basically trying to profit from using her voice,” says Jennifer E. Rothman, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, who wrote a 2018 book called The Right of Publicity: Privacy Reimagined for a Public World. “Even though they didn't literally use her voice, they were instructing someone to sing in a confusingly similar manner to Midler.”

It doesn’t matter whether a person’s actual voice is used in an imitation or not, Rothman says, only whether that audio confuses listeners. In the legal system, there is a big difference between imitation and simply recording something “in the style” of someone else. “No one owns a style,” she says.

Other legal experts don’t see what OpenAI did as a clear-cut impersonation. “I think that any potential ‘right of publicity’ claim from Scarlett Johansson against OpenAI would be fairly weak given the only superficial similarity between the ‘Sky’ actress' voice and Johansson, under the relevant case law,” Colorado law professor Harry Surden wrote on X on Tuesday. Frye, too, has doubts. “OpenAI didn’t say or even imply it was offering the real Scarlett Johansson, only a simulation. If it used her name or image to advertise its product, that would be a right-of-publicity problem. But merely cloning the sound of her voice probably isn’t,” he says.

But that doesn’t mean OpenAI is necessarily in the clear. “Juries are unpredictable,” Surden added.

Frye is also uncertain how any case might play out, because he says right of publicity is a fairly “esoteric” area of law. There are no federal right-of-publicity laws in the United States, only a patchwork of state statutes. “It’s a mess,” he says, although Johansson could bring a suit in California, which has fairly robust right-of-publicity laws.

OpenAI’s chances of defending a right-of-publicity suit could be weakened by a one-word post on X—“her”—from Sam Altman on the day of last week’s demo. It was widely interpreted as a reference to Her and Johansson’s performance. “It feels like AI from the movies,” Altman wrote in a blog post that day.

To Grimmelmann at Cornell, those references weaken any potential defense OpenAI might mount claiming the situation is all a big coincidence. “They intentionally invited the public to make the identification between Sky and Samantha. That's not a good look,” Grimmelmann says. “I wonder whether a lawyer reviewed Altman's ‘her’ tweet.” Combined with Johansson’s revelations that the company had indeed attempted to get her to provide a voice for its chatbots—twice over—OpenAI’s insistence that Sky is not meant to resemble Samantha is difficult for some to believe.

“It was a boneheaded move,” says David Herlihy, a copyright lawyer and music industry professor at Northeastern University. “A miscalculation.”

Other lawyers see OpenAI’s behavior as so manifestly goofy they suspect the whole scandal might be a deliberate stunt—that OpenAI judged that it could trigger controversy by going forward with a sound-alike after Johansson declined to participate but that the attention it would receive from seemed to outweigh any consequences. “What’s the point? I say it’s publicity,” says Purvi Patel Albers, a partner at the law firm Haynes Boone who often takes intellectual property cases. “The only compelling reason—maybe I’m giving them too much credit—is that everyone’s talking about them now, aren’t they?”

457 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twinkump Linkdump

I'm on a 20+ city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me in SAN DIEGO at MYSTERIOUS GALAXY next MONDAY (Mar 24), and in CHICAGO with PETER SAGAL on Apr 2. More tour dates here.

I have an excellent excuse for this week's linkdump: I'm in Germany, but I'm supposed to be in LA, and I'm not, because London Heathrow shut down due to a power-station fire, which meant I spent all day yesterday running around like a headless chicken, trying to get home in time for my gig in San Diego on Monday (don't worry, I sorted it):

https://www.mystgalaxy.com/32425Doctorow

Therefore, this is 30th linkdump, in which I collect the assorted links that didn't make it into this week's newsletters. Here are the other 29:

https://pluralistic.net/tag/linkdump/

I always like to start and end these 'dumps with some good news, which isn't easy in these absolutely terrifying times. But there is some good news: Wil Wheaton has announced his new podcast, a successor of sorts to the LeVar Burton Reads podcast. It's called "It's Storytime" and it features Wil reading his favorite stories handpicked from science fiction magazines, including On Spec, the magazine that bought my very first published story (I was 16, it ran in their special youth issue, it wasn't very good, but boy did it mean a lot to me):

https://wilwheaton.net/podcast/

Here's some more good news: a court has found (again!) that works created by AI are not eligible for copyright. This is the very best possible outcome for people worried about creators' rights in the age of AI, because if our bosses can't copyright the botshit that comes out of the "AI" systems trained on our work, then they will pay us:

https://www.yahoo.com/news/us-appeals-court-rejects-copyrights-171203999.html

Our bosses hate paying us, but they hate the idea of not being able to stop people from copying their entertainment products so! much! more! It's that simple:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/20/everything-made-by-an-ai-is-in-the-public-domain/

This outcome is so much better than the idea that AI training isn't fair use – an idea that threatens the existence of search engines, archiving, computational linguistics, and other clearly beneficial activities. Worse than that, though: if we create a new copyright that allows creators to prevent others from scraping and analyzing their works, our bosses will immediately alter their non-negotiable boilerplate contracts to demand that we assign them this right. That will allow them to warehouse huge troves of copyrighted material that they will sell to AI companies who will train models designed to put us on the breadline (see above, re: our bosses hate paying us):

https://pluralistic.net/2024/03/13/hey-look-over-there/#lets-you-and-he-fight

The rights of archivists grow more urgent by the day, as the Trump regime lays waste to billions of dollars worth of government materials that were produced at public expense, deleting decades of scientific, scholarly, historical and technical materials. This is the kind of thing you might expect the National Archive or the Library of Congress to take care of, but they're being chucked into the meat-grinder as well.

To make things even worse, Trump and Musk have laid waste to the Institute of Museum and Library Services, a tiny, vital agency that provides funding to libraries, archives and museums across the country. Evan Robb writes about all the ways the IMLS supports the public in his state of Washington:

Technology support. Last-mile broadband connection, network support, hardware, etc. Assistance with the confusing e-rate program for reduced Internet pricing for libraries.

Coordinated group purchase of e-books, e-audiobooks, scholarly research databases, etc.

Library services for the blind and print-disabled.

Libraries in state prisons, juvenile detention centers, and psychiatric institutions.

Digitization of, and access to, historical resources (e.g., newspapers, government records, documents, photos, film, audio, etc.).

Literacy programming and support for youth services at libraries.

The entire IMLS budget over the next 10 years rounds to zero when compared to the US federal budget – and yet, by gutting it, DOGE is amputating significant parts of the country's systems that promote literacy; critical thinking; and universal access to networks, media and ideas. Put it that way, and it's not hard to see why they hate it so.

Trying to figure out what Trump is up to is (deliberately) confusing, because Trump and Musk are pursuing a chaotic agenda that is designed to keep their foes off-balance:

https://www.wired.com/story/elon-musk-donald-trump-chaos/

But as Hamilton Nolan writes, there's a way to cut through the chaos and make sense of it all. The problem is that there are a handful of billionaires who have so much money that when they choose chaos, we all have to live with it:

The significant thing about the way that Elon Musk is presently dismantling our government is not the existence of his own political delusions, or his own self-interested quest to privatize public functions, or his own misreading of economics; it is the fact that he is able to do it. And he is able to do it because he has several hundred billion dollars. If he did not have several hundred billion dollars he would just be another idiot with bad opinions. Because he has several hundred billion dollars his bad opinions are now our collective lived experience.

https://www.hamiltonnolan.com/p/the-underlying-problem

We actually have a body of law designed to prevent this from happening. It's called "antitrust" and 40 years ago, Jimmy Carter decided to follow the advice of some of history's dumbest economists who said that fighting monopolies made the economy "inefficient." Every president since, up to – but not including – Biden, did even more to encourage monopolization and the immense riches it creates for a tiny number of greedy bastards.

But Biden changed that. Thanks to the "Unity Taskforce" that divided up the presidential appointments between the Democrats' corporate wing and the Warren/Sanders wing, Biden appointed some of the most committed, effective trustbusters we'd seen for generations:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/18/administrative-competence/#i-know-stuff

After Trump's election, there was some room for hope that Trump's FTC would continue to pursue at least some of the anti-monopoly work of the Biden years. After all, there's a sizable faction within the MAGA movement that hates (some) monopolies:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/01/24/enforcement-priorities/#enemies-lists

But last week, Trump claimed to have illegally fired the two Democratic commissioners on the FTC: Alvaro Bedoya and Rebecca Slaughter. I stan both of these commissioners, hard. When they were at the height of their powers in the Biden years, I had the incredible, disorienting experience of getting out of bed, checking the headlines, and feeling very good about what the government had just done.

Trump isn't legally allowed to fire Bedoya and Slaughter. Perhaps he's just picking this fight as part of his chaos agenda (see above). But there are some other pretty good theories about what this is setting up. In his BIG newsletter, Matt Stoller proposes that Trump is using this case as a wedge, trying to set a precedent that would let him fire Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell:

https://www.thebignewsletter.com/p/why-trump-tried-to-fire-federal-trade

But perhaps there's more to it. Stoller just had Commissioner Bedoya on Organized Money, the podcast he co-hosts with David Dayen, and Bedoya pointed out that if Trump can fire Democratic commissioners, he can also fire Republican commissioners. That means that if he cuts a shady deal with, say, Jeff Bezos, he can order the FTC to drop its case against Amazon and fire the Republicans on the commission if they don't frog when he jumps:

https://www.organizedmoney.fm/p/trumps-showdown-at-the-ftc-with-commissioner

(By the way, Organized Money is a fantastic podcast, notwithstanding the fact that they put me on the show last week:)

https://audio.buzzsprout.com/6f5ly01qcx6ijokbvoamr794ht81

The future that our plutocrat overlords are grasping for is indeed a terrible one. You can see its shape in the fantasies of "liberatarian exit" – the seasteads, free states, and other assorted attempts to build anarcho-capitalist lawless lands where you can sell yourself into slavery, or just sell your kidneys. The best nonfiction book on libertarian exit is Raymond Criab's 2022 "Adventure Capitalism," a brilliant, darkly hilarious and chilling history of every time a group of people have tried to found a nation based on elevating selfishness to a virtue:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/14/this-way-to-the-egress/#terra-nullius

If Craib's book is the best nonfiction volume on the subject of libertarian exit, then Naomi Kritzer's super 2023 novel Liberty's Daughter is the best novel about life in a libertopia – a young adult novel about a girl growing up in the hell that would be life with a Heinlein-type dad:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/11/21/podkaynes-dad-was-a-dick/#age-of-consent

But now this canon has a third volume, a piece of design fiction from Atelier Van Lieshout called "Slave City," which specs out an arcology populated with 200,000 inhabitants whose "very rational, efficient and profitable" arrangements produce €7b/year in profit:

https://www.archdaily.com/30114/slave-city-atelier-van-lieshout

This economic miracle is created by the residents' "voluntary" opt-in to a day consisting of 7h in an office, 7h toiling in the fields, 7h of sleep, and 3h for "leisure" (e.g. hanging out at "The Mall," a 24/7, 26-storey " boundless consumer paradise"). Slaves who wish to better themselves can attend either Female Slave University or Male Slave University (no gender controversy in Slave City!), which run 24/7, with 7 hours of study, 7 hours of upkeep and maintenance on the facility, 7h of sleep, and, of course, 3h of "leisure."

The field of design fiction is a weird and fertile one. In his traditional closing keynote for this year's SXSW Interactive festival, Bruce Sterling opens with a little potted history of the field since it was coined by Julian Bleeker:

https://bruces.medium.com/how-to-rebuild-an-imaginary-future-2025-0b14e511e7b6

Then Bruce moves on to his own latest design fiction project, an automated poetry machine called the Versificatore first described by Primo Levi in an odd piece of science fiction written for a newspaper. The Versificatore was then adapted to the screen in 1971, for an episode of an Italian sf TV show based on Levi's fiction:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tva-D_8b8-E

And now Sterling has built a Versificatore. The keynote is a sterlingian delight – as all of his SXSW closers are. It's a hymn to the value of "imaginary futures" and an instruction manual for recovering them. It could not be more timely.

Sterling's imaginary futures would be a good upbeat note to end this 'dump with, but I've got a real future that's just as inspiring to close us out with: the EU has found Apple guilty of monopolizing the interfaces to its devices and have ordered the company to open them up for interoperability, so that other manufacturers – European manufacturers! – can make fully interoperable gadgets that are first-class citizens of Apple's "ecosystem":

https://www.reuters.com/technology/apple-ordered-by-eu-antitrust-regulators-open-up-rivals-2025-03-19/

It's a good reminder that as America crumbles, there are still places left in the world with competent governments that want to help the people they represent thrive and prosper. As the Prophet Gibson tells us, "the future is here, it's just not evenly distributed." Let's hope that the EU is living in America's future, and not the other way around.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/03/22/omnium-gatherum/#storytime

Image: TDelCoro https://www.flickr.com/photos/tomasdelcoro/48116604516/

CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

#pluralistic#bruce sterling#design fiction#sxsw#Atelier Van Lieshout#libertopia#libertarian exit#wil wheaton#sf#science fiction#podcasts#linkdump#linkdumps#apple#eu#antitrust#interop#interoperabilty#ai#copyright#law#glam#Institute of Museum and Library Services#libraries#museums#ftc#matt stoller#david dayen#alvaro bedoya#rebecca slaughter

86 notes

·

View notes

Note

re all the AI talk, I've got a few works published on Smashwords (owned by Draft to Digital). Last year, they emailed out a questionaire to all their authors, even the tiny nobodies like me, asking if we'd want to license our works for AI training and if so how much would we want to be paid and what types of AI models would we want to license to.

A few weeks later, the next email said they wouldn't be going forward with such a licensing system because the authors didn't want it.

When I filled it out, I said I could be chill with it for an absurdly high price, and only for training models that would not produce prose fiction (in other words, not models that would compete with me and other Smashwords authors).

I suspect that the majority of selfpub authors who filled it out either said "absolutely not under any circumstances" or "Sure, for like ten thousand bucks per short story", and, well, an AI training dataset needs a mountain of data, they're not going to pay that much for a tiny drop so it isn't worth offering it.

Of course, AI companies aren't scrupulous enough to want to pay in the first place, and there's nothing stopping them from buying my work on Smashwords and hucking it into their pile, copyright notice and all, but it did get me thinking about how datasets are compiled and what sorts of licensing agreements would be involved in compiling one ethically.

And I appreciate that Smashwords/Draft to Digital cared enough to ask and then listen when we all said no.

--

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

A federal judge has sided with Anthropic in a major copyright ruling, declaring that artificial intelligence developers can train models using published books without authors’ consent. The decision, filed Monday in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, sets a precedent that training AI systems on copyrighted works constitutes fair use. Though it doesn’t guarantee other courts will follow, Judge William Alsup’s ruling makes the case the first of dozens of ongoing copyright lawsuits to give an answer about fair use in the context of generative AI. It’s a question that has been raised by creatives across various industries for years since generative AI tools exploded into the mainstream, allowing users to easily produce art from models trained on copyrighted work — often without the human creators’ knowledge or permission. AI companies have been hit with a slew of copyright lawsuits from media companies, music labels and authors since 2023. Artists have signed multiple open letters urging government officials and AI developers to constrain the unauthorized use of copyrighted works. In recent years, companies have also increasingly reached licensing deals with AI developers to dictate terms of use for their artists’ works. Alsup ruled on a lawsuit filed in August by three authors — Andrea Bartz, Charles Graeber and Kirk Wallace Johnson — who claimed that Anthropic ignored copyright protections when it pirated millions of books and digitized purchased books to feed into its large language models, which helped train them to generate humanlike text responses. “The copies used to train specific LLMs were justified as a fair use,” Alsup wrote in the ruling. “Every factor but the nature of the copyrighted work favors this result. The technology at issue was among the most transformative many of us will see in our lifetimes.”

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok. It's pretty clear you are more welcoming of AI, and it does have enough merits to not be given a knee jerk reaction outright.

And how the current anti-ai stealing programs could be misused.

But isn't so much of the models built on stolen art? That is one of the big thing keeping me from freely enjoying it.

The stolen art is a thing that needs to be addressed.

Though i agree that the ways that such addressing are being done in are not ideal. Counterproductive even.

I could make a quip here and be like "stolen art??? But the art is all still there, and it looks fine to me!" And that would be a salient point about the silliness of digital theft as a concept, but I know that wouldn't actually address your point because what you're actually talking about is art appropriation by generative AI models.

But the thing is that generative AI models don't really do that, either. They train on publicly posted images and derive a sort of metadata - more specifically, they build a feature space mapping out different visual concepts together with text that refers to them. This is then used at the generative stage in order to produce new images based on the denoising predictions of that abstract feature model. No output is created that hasn't gone through that multi-stage level of abstraction from the training data, and none of the original training images are directly used at all.

Due to various flaws in the process, you can sometimes get a model to output images extremely similar to particular training images, and it is also possible to get a model to pastiche a particular artist's work or style, but this is something that humans can also do and is a problem with the individual image that has been created, rather than the process in general.

Training an AI model is pretty clearly fair use, because you're not even really re-using the training images - you're deriving metadata that describes them, and using them to build new images. This is far more comparable to the process by which human artists learn concepts than the weird sort of "theft collage" that people seem to be convinced is going on. In many cases, the much larger training corpus of generative AI models means that an output will be far more abstracted from any identifiable source data (source data in fact is usually not identifiable) than a human being drawing from a reference, something we all agree is perfectly fine!

The only difference is that the AI process is happening in a computer with tangible data, and is therefore quantifiable. This seems to convince people that it is in some way more ontologically derivative than any other artistic process, because computers are assumed to be copying whereas the human brain can impart its own mystical juju of originality.

I'm a materialist and think this is very silly. The valid concerns around AI are to do with how society is unprepared for increased automation, but that's an entirely different conversation from the art theft one, and the latter actively distracts from the former. The complete refusal from some people to even engage with AI's existence out of disgust also makes it harder to solve the real problem around its implementation.

This sucks, because for a lot of people it's not really about copyright or intellectual property anyway. It's about that automation threat, and a sort of human condition anxiety about being supplanted and replaced by automation. That's a whole mess of emotions and genuine labour concerns that we need to work through and break down and resolve, but reactionary egg-throwing at all things related to machine learning is counterproductive to that, as is reading out legal mantras paraphrasing megacorps looking to expand copyright law to over shit like "art style".

I've spoken about this more elsewhere if you look at my blog's AI tag.

159 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Saw the anon ask about Ai, and I am curious too!

I completely understand not using Ai and calling it art, or submitting works without permission from the OP, but I am curious why people are against Ai like C.Ai in the case it’s used for entertainment

I’ve seen posts that claim it’s “anti-human”, or “anti-social enabling”, but I feel like it’s not?? Considering the fact that people who are anti-social are antisocial with or without Ai.

I can understand the claims of “anti-human” if ai is being improperly used to steal work though; but I feel it’s unfair to make that a general claim?

I also understand that Ai (specifically C.Ai) uses public works to grow its recognition patterns and learn “how” to write, but most responses are individualized for whatever chat/topic it responds to, so I don’t quite understand how it’s being considered (by most) as stolen work??

Genuinely curious and would love your take because I respect/love your work(s)!

Side note, I have a personal rule that I think most who support Ai should also have: I never have and never will feed Ai any work without OP consent.

With that being said, do you think that if most Ai supporters had the same rule, that Ai would still be a big deal? 🤔

Back in the mid-00s, I helped train a language model in the hopes it would one day achieve true AI-levels of learning. It involved a volunteer website where we taught the model ourselves, and I don't know what happened to the organization, but that was my first introduction to language models.

Voluntarily training a language model one-on-one 20 years ago is a far cry from the mass-theft machines of today that churn out forest-destruction levels of mediocrity.

C.AI, as far as I understand it, is a generative language model, and therefore cannot be separated from the ethical issues of other generative AI models (vast resource use, art theft, racist and sexist bias, privacy issues, etc.).

C.AI and other AIs that give the user individualized responses are trained on materials that, most likely, they haven't obtained with permission and consent from the original creators. That is why it's considered stolen. Not because it takes the original work and gives it to someone else, but because it bases its patterns of repetition from written works that were fed into it.

AI art cannot be copyrighted, because it does not belong to the model or the user. That alone should tell you how the US federal courts view generative AI in terms of original works.

I'm sure there are many more well-informed people than me who you can find talking about AI, but Kyle Hill is one of my favorite science educators, and I recommend his videos (as well as others below):

Generative AI - We Aren't Ready

Dead Internet Theory

Digital Tar Pits - How to Fight Back Against AI

AI Is Dangerous, but Not for the Reasons You Think - TED Talk

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

As if I couldn't already hate these dudes enough:

On Monday, court documents revealed that AI company Anthropic spent millions of dollars physically scanning print books to build Claude, an AI assistant similar to ChatGPT. In the process, the company cut millions of print books from their bindings, scanned them into digital files, and threw away the originals solely for the purpose of training AI—details buried in a copyright ruling on fair use whose broader fair use implications we reported yesterday. [...] While destructive scanning is a common practice among smaller-scale operations, Anthropic's approach was somewhat unusual due to its massive scale. For Anthropic, the faster speed and lower cost of the destructive process appear to have trumped any need for preserving the physical books themselves. [...] Buying used physical books sidestepped licensing entirely while providing the high-quality, professionally edited text that AI models need, and destructive scanning was simply the fastest way to digitize millions of volumes. The company spent "many millions of dollars" on this buying and scanning operation, often purchasing used books in bulk. Next, they stripped books from bindings, cut pages to workable dimensions, scanned them as stacks of pages into PDFs with machine-readable text including covers, then discarded all the paper originals. The court documents don't indicate that any rare books were destroyed in this process—Anthropic purchased its books in bulk from major retailers—but archivists long ago established other ways to extract information from paper. For example, The Internet Archive pioneered non-destructive book scanning methods that preserve physical volumes while creating digital copies. And earlier this month, OpenAI and Microsoft announced they're working with Harvard's libraries to train AI models on nearly 1 million public domain books dating back to the 15th century—fully digitized but preserved to live another day.

Do you think any of these Silicon Valley pieces of shit actually care about anything? Do they actually have beliefs? They're out here trying to make a machine act more like a human and I'm not sure they've figured out how to do that for themselves, or if they're even capable of it. Nuke silicon valley.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Latest AO3 scrape into AI database

Please read this if you're an AO3 user with public, not archive-locked works. This is information on the latest known instance of someone taking AO3 works to build datasets on which to train AI and the ongoing process to get them removed. I don't really make posts adressing people, but I am furious about my work being used and I know some of my mutuals don't have their fics archive-locked so I hope I can at least get the information to some people.

Earlier this month (April) a, to my understanding, rp fanworks website named PaperDemon.com got word that a user of an AI dataset website, HuggingFace, had scraped its contents, as well as those of a bunch of other websites among which AO3 is included, where they can be freely downloaded to train generative AI models. For AO3 specifically, the user themselves reports that all public works with IDs ranging from 1 to 63,200,000 have been scraped.

As of April 25 and per the updating Paper Demon publication, 2 of 8 affected sites have gotten their content removed and the rest have achieved temporary disabling (supposedly data is visible but not downloadable) pending a counter-notice from the scraper, who appears to be set on the aim of dismissing the request as unfounded. Furthermore, the AO3 dataset has already been downloaded 2,244 times in the last month. On earlier updates of the PD post they mentioned that the scraper agreed to remove, on an individual basis, the content of those who file a Copyright infringement report. So far there are about 150 reports against the AO3 dataset. The scraper also uploaded them to another website, but appears to have removed at least the PD ones, as well as to his personal website which the PD post doesn't even link for safety reasons. The platform HuggingFace has also been made aware of the situation (that's what got us the temporary disabling)

I have personally filed a Copyright infringement report using the helpful guide put together by the PD team and have emailed the scraper on the address listed there providing the title and URL of my work and requesting for it to be removed from the dataset.

I have one concern regarding the PD guide, though (disclaimer: this is coming from someone with a very limited knowledge on computers & digital information and my understanding of the majority of concepts is from 3h of internet searches + ms help page + messing around in my laptop) They rightly recommend to not publish the work URLs in the report and instead instruct to collect them in a spreadsheet in .cvs filetype. This, however, has a problem of personally-identifying metadata being stored "alongside" the file itself and it can be accessed. The MS Excel Inspector tool allows the removal of this type of data, but apparently only when it's shared through the MS account? For Google sheets there is a different problem, which is that you can't just make your spreadsheet in .csv filetype, you need to download it and the reupload it (if there is a way, it's not easily accessible; i looked at like 4 step-by-step guides and they all said to download) which again adds properties to the file that may contain personal information.

I was very sleep deprived and very close to giving up, because I do not wish to provide a person that's massively stealing content any information linked to my identity, but then I thought I could just send the info on the email body itself. It's not the best solution but I think it's better than the alternative.

I am beyond mad that this happened and will archive-lock my affected work as soon as I receive a response (or after enough days of silence, I guess, but I hope my report won't be ignored). Unfortunately I can't file a DMCA take-down notice, because it requires personal information which might be shared with the infringer if they file a counter-notice, but I have hope that, if everyone whose works were scraped files Copyright infringement reports, AO3's DMCA won't be dismissed.

I encourage anyone who has read this to also file a report to get their work(s) removed asap and, if anyone is more informed or knowledgeable on the topic, to please share any useful info you have. I might also email AO3 to inquire about the DMCA status later because the PD publication is understandably only really tracking theirs.

#i don't feel comfortable tagging anyone in this but i might come into my mutuals' inboxes to tell you if i know your fics aren't locked#i don't want to be annoying about this but i can't imagine anyone will be happy their work got stolen and fed to genAI#mine is just one piece of fanart but i am still disgusted by this#tagging my two main fandoms so it can hopefully be seen#aftg#all for the game#txf#the x files#ao3#archive of our own

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The US Copyright Office is currently asking for input on generative AI systems ...

... to help assess whether legislative or regulatory steps in this area are warranted. Here is what I wrote to them, and what I want as a creative professional: AI systems undermine the value of human creative thinking and work, and harbor a danger for us creative people that should not be underestimated. There is a risk of a transfer of economic advantage to a few AI companies, to the detriment of hundreds of thousands of creatives. It is the creative people with their works who create the data and marketing basis for the AI companies, from which the AI systems feed. AI systems cannot produce text, images or music without suitable training material, and the quality of that training material has a direct influence on the quality of the results. In order to supply the systems with the necessary data, the developers of those AI systems are currently using the works of creative people - without consent or even asking, and without remuneration. In addition, creative professionals are denied a financial participation in the exploitation of the AI results created on the basis of the material. My demand as a creative professional is this: The works and achievements of creative professionals must also be protected in digital space. The technical possibility of being able to read works via text and data mining must not legitimize any unlicensed use! The remuneration for the use of works is the economic basis on which creative people work. AI companies are clearly pursuing economic interests with their operation. The associated use of the work for commercial purposes must be properly licensed, and compensated appropriately. We need transparent training data as an access requirement for AI providers! In order to obtain market approval, AI providers must be able to transparently present this permission from the authors. The burden of proof and documentation of the data used - in the sense of applicable copyright law - lies with the user and not with the author. AI systems may only be trained from comprehensible, copyright-compliant sources.

____________________________

You can send your own comment to the Copyright Office here: https://www.regulations.gov/document/COLC-2023-0006-0001

My position is based on the Illustratoren Organisation's (Germany) recently published stance on AI generators: https://illustratoren-organisation.de/2023/04/04/ki-aber-fair-positionspapier-der-kreativwirtschaft-zum-einsatz-von-ki/

172 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you like AI art?

The simple and biggest answer is that it lets people create and experience art that would not otherwise exist. And in particular, it lets me give life to the images in my head without needing to destroy my wrists in the process. Even without anything else, that would be enough.

For a more specific answer - the way I see it, there are two main ways of approaching AI art. The artist can aim for the expectations of other art forms, or they can lean into ones specific to AI. I think both of these approaches have significant merit, and much more flexibility than most people realize. I've seen many incredible examples of each approach, and I share them whenever I can.

As someone who tends to feel like a crude imitation of a human, I have deep investment in the idea that mimicking actions expected of a human is just as meaningful as doing them "normally". And, for that matter, the idea that not acting "normally" is not a flaw in the first place. So I wholeheartedly reject the idea that either of these things could be held against AI, and I find that idea incompatible with accepting me as a person.

Some people accuse image generators of creating collages, but that could not be further from the truth. AI models record patterns, not actual pieces of images. And I certainly can't agree with the idea that collages lack artistic merit in the first place. My blog banner is a collection of pre-existing images, my image edits are modifications to existing images, and I've been working on an AMV that combines clips of an existing show with the audio of an existing song. All of these involve using copyrighted material without permission from the copyright holders, and I reject the idea that I should need that permission, just as I reject the idea that training an AI model on copyrighted material should require permission.

I also write. Writing does not involve creating an image directly, but it involves creating text that others might depict in their mind as an image. And writing an image prompt means creating text that an AI can depict digitally as an image. Just as writing stories is an artistic action, writing prompts is also an artistic action.

But there is so much more to image generation than writing prompts. Image generators can offer countless other controls, and the quality of AI art depends on its creator's skill in using them. AI art is a skilled pursuit, and while it does not require manual drawing, making good AI art requires assessing the generator's outputs and identifying ways to iterate on them.

AI art sometimes gets characterized as being under the thumb of big tech companies, but that is also false. Stable Diffusion is an open-source image generator you can run on your own computer, and I've personally done so. It's free, it's got countless independent add-ons to change the workings or to use different models, it doesn't require using anyone else's servers. It's great. And by having it locally, I can see for myself that the models are nowhere near big enough to actually contain the images they're trained on, and that the power consumption is no more than using the internet or playing a video game.

AI art offers an ocean of possibilities, both on its own and in conjunction with other art forms, and we've barely scratched the surface. I'm excited to see how much more we can do with it and to be as much a part of that as I can, and I think everyone should take a few minutes to try it out for themselves.

That is why I like AI art.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

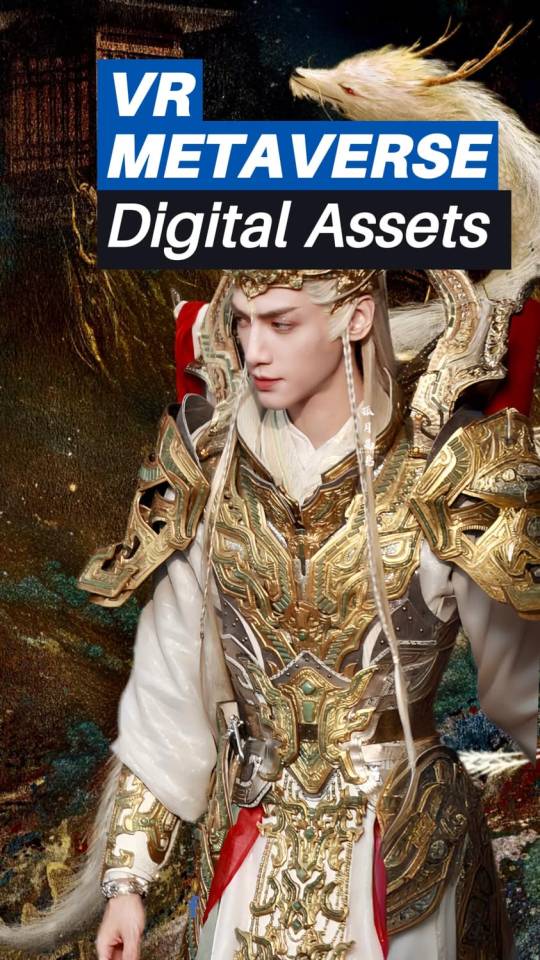

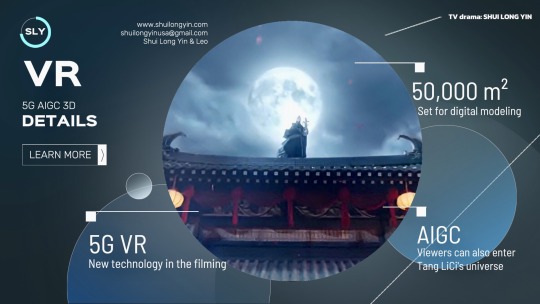

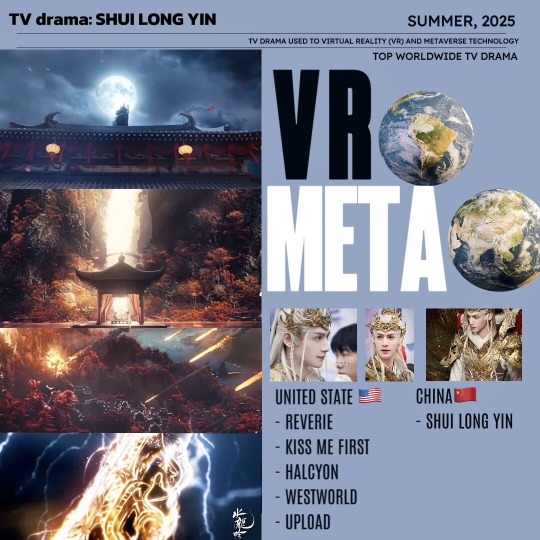

Shui Long Yin VR Metaverse: Technologies and Digital Assets, and the melon about it being released in Summer 2025

What is the metaverse?

The Shui Long Yin metaverse is a parallel world closely resembling the real world, built through the use of digital modelling and technologies such as VR and AR, and designed to exist permanently.

This virtual realm integrates cutting-edge advancements, including blockchain, augmented reality, 5G, big data, artificial intelligence, and 3D engines.

When you acquire a ticket to this world, you gain a digital asset, allowing you to become an immersive citizen within the Shui Long Yin Metaverse.

Every item within Shui Long Yin can be experienced through Augmented Reality using VR devices, providing a seamless blend of the physical and digital realms. These digital assets are permanent, and in some cases, overseas users may trade or transfer their tickets to enter the Shui Long Yin world.

What is VR and AR?

Virtual Reality (VR) is a technology that enables users to interact within a computer-simulated environment.

Augmented Reality (AR), on the other hand, combines elements of VR by merging the real world with computer-generated simulations. A well-known example of AR is the popular game Pokémon Go, where virtual objects are integrated into real-world surroundings.

Tang LiCi's universe

The Shui Long Yin film crew has digitally modeled the core art assets, 50 000 square meters.

What technologies does China Mobile & Migu bring to the table?

China Mobile served as the lead organizer for the 2023 World VR Industry Conference. Its subsidiary, Migu, has also been dedicated to advancing projects in this area.

Shui Long Yin is their first priority this summer 2025.

5G+AI: VR world in Metaverse

AIGC AR 3D: Using AI technology in graphics computer, with the best trained AI system in China.

Video ringtones as a globally pioneering service introduced by China Mobile.

Shui Long Yin from Screen to Metaverse to Real Life: Epic Battles and Intricate Plotlines

The United States and China are world pioneers in the development of TV drama integration VR Metaverse. Notably, Shui Long Yin is the sixth TV drama map worldwide to be merged into the Metaverse.

How can we enjoy these technologies?

-- First we need 5G -- According to a report by the Global Mobile Suppliers Association (GSA), by June 2022:

》There are 70 countries around the world had active 5G networks, you can fully experience all the technology featured in Shui Long Yin.

Example: South Korea, China, and the United States have been at the forefront. Follow after are Japan, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia, Taiwan, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Viet Nam...

》No worries—even in countries without 5G, you can still watch the drama and enjoy AIGC and 3D technology through the streaming platforms Migu Video and Mango.

•Mango available on IOS and Android, Harmony OS

•Migu (Mobile HD) soon availabe on IOS and Android, Harmony OS

-- Second, we need VR devices --

In country where VR is already commonplace, such as the United States, owning a VR device is considered entirely normal. Users can select devices that best suit their preferred forms of home entertainment.

European countries have also become fairly familiar with VR technology.

However, it is still relatively new to many parts of Asia. When choosing a VR device, it’s important to select one that is most compatible with your intended activities, whether that’s gaming, watching movies, or working.

It's no surprise to us that the drama Shui Long Yin will be released in the summer 2025, but it will also be coinciding with offline tourism to Long Yin Town in Chengdu, online VR Metaverse travel, and 3D experiences on the new streaming platforms Migu and Mango. Stay tuned!

Tv drama: SHUI LONG YIN Shui Long Yin & Leo All music and image are copyrighted and belong to the respective owners, included the official film crew SHUILONGYIN.

#shui long yin#tang lici#水龙吟#唐俪辞#luo yunxi#luo yun xi#leo luo#罗云熙#cdrama#chinese drama#long yin town#long yin town vr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

saw someone describe people who don’t want their art or writing used for AI training as “roleplaying as temporarily embarrassed IP holders” and blamed them for the publishing industry’s recent push against libraries. which, aside from being wrong, is also funny.

why do people think artists only just now started taking themselves seriously? i remember seeing guides for digital artists online on how to deal with copyright infringements by big companies in like 2009. before it was robots, it was hot topic. and there have been artists and craftspeople for far longer than there were corporations. it’s weird to me that people don’t seem to understand that there are individual artists who do interact with the economy and legal system much like other business owners do.

as a person who originally was fixin to go into the music industry, i do understand the issues with the way big companies take advantage of IP law, and as an internet resident i’ve seen much of the same used against artists and writers online, so obviously i think putting energy towards the soul-grinding machinery of our broken society is a deal with the devil. but it is bizarre that people will gladly swallow the rhetoric that it’s somehow the fault of artists complaining about their work being used against them (an understandable frustration) that big companies are continuing to do the same exact thing they were doing anyway before the AI zeitgeist.

i don’t know the intentions or mindset of the person i’m vagueing, hence why i’m vagueing, but it’s always odd to me when people are like “gah you delusional creatives, thinking your small business is just as important to society as REAL creative businesses like Disney! also it’s YOUR fault, small artist, that BIG EVIL CORPORATION is doing some bullshit, because they’re using the same legal system to do it!”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

While the startup has won its “fair use” argument, it potentially faces billions of dollars in damages for allegedly pirating over 7 million books to build a digital library.

Anthropic has scored a major victory in an ongoing legal battle over artificial intelligence models and copyright, one that may reverberate across the dozens of other AI copyright lawsuits winding through the legal system in the United States. A court has determined that it was legal for Anthropic to train its AI tools on copyrighted works, arguing that the behavior is shielded by the “fair use” doctrine, which allows for unauthorized use of copyrighted materials under certain conditions.

3 notes

·

View notes