#Haitian Occupation

Text

In 1995 US troops returned for a second occupation of Haiti:

The second US occupation of Haiti was a shorter one, restoring an overthrown Haitian government and relying on many of the same arrogant assumptions that underlaid the first. This is one of many reminders that Bill Clinton's Presidency was anything but a pacific time where very little happened, first, and that US power has and continues to be freely deployed in its oldest imperialistic tradition besides its march to the Pacific.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#american history#haitian history#military history#second us occupation of haiti

0 notes

Text

How can a person make up for seven decades of misrepresentation and willful distortion in the time allotted to a sound bite? How can you explain that the Israeli occupation doesn’t have to resort to explosions—or even bullets and machine-guns—to kill? That occupation and apartheid structure and saturate the everyday life of every Palestinian? That the results are literally murderous even when no shots are fired? Cancer patients in Gaza are cut off from life-saving treatments. Babies whose mothers are denied passage by Israeli troops are born in the mud by the side of the road at Israeli military checkpoints. Between 2000 and 2004, at the peak of the Israeli roadblock-and-checkpoint regime in the West Bank (which has been reimposed with a vengeance), sixty-one Palestinian women gave birth this way; thirty-six of those babies died as a result.That never constituted news in the Western world. Those weren’t losses to be mourned. They were, at most, statistics.

What we are not allowed to say, as Palestinians speaking to the Western media, is that all life is equally valuable. That no event takes place in a vacuum. That history didn’t start on October 7, 2023, and if you place what’s happening in the wider historical context of colonialism and anticolonial resistance, what’s most remarkable is that anyone in 2023 should be still surprised that conditions of absolute violence, domination, suffocation, and control produce appalling violence in turn. During the Haitian revolution in the early 19th century, former slaves massacred white settler men, women, and children. During Nat Turner’s revolt in 1831, insurgent slaves massacred white men, women, and children. During the Indian uprising of 1857, Indian rebels massacred English men, women, and children. During the Mau Mau uprising of the 1950s, Kenyan rebels massacred settler men, women, and children. At Oran in 1962, Algerian revolutionaries massacred French men, women, and children. Why should anyone expect Palestinians—or anyone else—to be different? To point these things out is not to justify them; it is to understand them. Every single one of these massacres was the result of decades or centuries of colonial violence and oppression, a structure of violence Frantz Fanon explained decades ago in The Wretched of the Earth.

What we are not allowed to say, in other words, is that if you want the violence to stop, you must stop the conditions that produced it. You must stop the hideous system of racial segregation, dispossession, occupation, and apartheid that has disfigured and tormented Palestine since 1948, consequent upon the violent project to transform a land that has always been home to many cultures, faiths, and languages into a state with a monolithic identity that requires the marginalization or outright removal of anyone who doesn’t fit. And that while what’s happening in Gaza today is a consequence of decades of settler-colonial violence and must be placed in the broader history of that violence to be understood, it has taken us to places to which the entire history of colonialism has never taken us before.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A symbol of resistance

Charlemagne Péralte

Charlemagne Péralte was a Haitian resistance leader shot by U.S. forces during the 1915 occupation.

After Péralte's death, U.S. troops displayed his body posed in a way that resembled a crucifixion – tied upright with a Haitian flag draped over him. This photo was intended to intimidate the Haitian population.

However, it backfired. The image resonated with Haitians, making Péralte a martyr and a symbol of resistance. There's even a famous Haitian painting called "The Crucifixion of Charlemagne Péralte for Freedom."

#resistance#Charlemagne Peralte#Ayiti#Hayti#Haiti#U.S. Occupation#martyr#Hero#The Crucifixion of Charlemagne Peralte#african diaspora#History#EvilisWinning#black liberation#1915

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

When white media write about rape, they use the passive voice. Haitian women were not raped or trafficked or forced into prostitution, the occupational forces were 'fathers' of their children. Then they left them all behind.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 28 July 1915, the United States invaded Haiti, crushing opposition and setting up a dictatorship which governed the country for the next 19 years. US Secretary of State Robert Lansing claimed the invasion was necessary to end "anarchy, savagery and oppression" in Haiti, and claimed that "the African race are devoid of any capacity for political organisation." The government had been lobbied for some time by US banking interests to occupy Haiti to assert US financial dominance as opposed to dominance by the financial institutions of the French former colonial power. In the years of occupation, the US forcibly dissolved parliament, killed thousands of people – and posed for photographs with their corpses – as well as siphoning wealth from the country. They also tied people up with ropes and forced them to work for no pay, killing people who attempted to flee. US authorities installed a puppet leader, Louis Borno, who admired fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, and had him take out a loan from the National City Bank, the forerunner of Citigroup. Around a quarter of Haiti's revenues then went towards paying for this loan. The measures left Haitian farmers "close to starvation level", according to the United Nations. While formal US colonial occupation ended in 1934, US retained neocolonial financial control of the country through the remaining debt until 1947. Reflecting on his role in the events, US Major General Smedley Butler stated that he "helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues," and described himself as a "racketeer for capitalism." More information, sources and map: https://stories.workingclasshistory.com/article/10016/us-invasion-of-haiti https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=668997001940185&set=a.602588028581083&type=3

497 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have seen very little discussion on this website about the situation in Haiti and figured maybe I’d try to start the conversation?

For those who aren’t aware, Haiti is the only country that led a successful slave rebellion which led to the establishment of an independent country, and a day hasn’t passed where they haven’t been punished for it. The country never had a chance to flourish as the west made sure to suck it economically dry and then dip when nothing was left.

This has left the country horrifically unstable in every way possible. However, the last few years, it has been on the brink of collapse due to absolutely no political leadership and as of now, Haiti has completely collapsed. The country is mostly run by gangs all competing for power. There is no where for refugees to escape. The west has completely abandoned any meaningful intervention and it has mostly been South American, Middle Eastern, and African countries who only seem interested in trying to bring peace. But since 2024 has begun, it is a terrifying place to be full of completely innocent people being screwed over by the west for standing up for themselves.

Of course, this is heavily over simplified and I have no personal connection to Haiti. So under the cut, I’m adding much more accurate and insightful information, as well as fundraisers, books, petitions, and Haitian run businesses and social media accounts. As someone who is studying history, it doesn’t take long to realize most nations struggling today have been victimized for wanting autonomy and freedom. From Palestine to Sudan, to DRC to Ukraine, there is so much preventable tragedy. As someone from a country who has historically inflicted these conditions on a lot of these nations, it’s frustrating to feel powerless to the injustice. I truly find the only thing that puts my mind at peace is education and spreading awareness. Don’t let their suffering be in vain.

*please correct me if any of this information is inaccurate*

Basic information:

Wikipedia

HAITI: A Brief History of a Complex Nation

Britannica: History of Haiti

How Haiti Was Forced To Pay Reparations For Freedom

[video] A Super Quick History of Haiti

The Root of Haiti's Misery: Reparations to Enslavers

Timeline: Haiti’s History and Current Crisis, Explained

[video] Why Haiti is in a Constant State of Emergency

A Brief History Of Haiti

The Haitian Revolution and the Hole in French High-School History

[video] How the World Destroyed Haiti

A Timeline of Haiti

Haiti: a history of intervention, occupation and resistance

[video] Fighting for Haiti

How Toussaint L’ouverture Rose from Slavery to Lead the Haitian Revolution

The Disappearing Land : Haiti, History, and the Hemisphere

History of Haiti

A History of United States Policy Towards Haiti

What is the history of foreign interventions in Haiti?

Haitian history and culture: A selection of online resources

Books:

The Black Jacobins: Toussaint l'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution

The Haitian Revolution

Silencing the Past

Fault Lines: Views across Haiti's Divide

Awakening the Ashes: An Intellectual History of the Haitian Revolution

Haiti: The Tumultuous History

Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People 1492-1971

The Haitians: A Decolonial History

Why the Cocks Fight: Dominicans, Haitians, and the Struggle for Hispaniola

Outrage for Outrage: A History of Colonialism in Haiti and Its Legacy

Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution

Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture

The Black Republic: African Americans and the Fate of Haiti

The Farming of Bones

The Rainy Season: Haiti Since Duvalier

The Uses of Haiti

The Butterfly’s Way: Voices from the Haitian Dyaspora in the United States

Charities:

*rating of 80+ on charitynavigator*

Hands Helping Haiti

Heartline Haiti

Hope for Haiti

Haiti Outreach

US Foundation for the Children of Haiti

Hands Together for Haitians

Haiti Empowered

Mission of Hope Haiti International

Haitian Health Foundation

Haiti Partners

Haiti Cardiac Alliance

New Life for Haiti

Locally Haiti

Clean Water for Haiti

Meds & Food for Kids

Haitian Roots

Project Medishare for Haiti

Friends of the Children of Haiti

Childrens Nutrition Program of Haiti

Fundraisers

Haiti Crisis Relief Fund

Haiti Emergency Fundraiser

Urgent Need to Complete Our Haitian Adoptions

Desperate Plea to Help Haitian Family

Haiti Food Emergency

Help a Deaf Haitian restore his life in Maryland

Help a friend get her sister & 3 kids out of Haiti

Daniel Jean - Haitian friend relocate to the US

Help Support My Family in Haiti

Support Young Haitian Artists!

Haitian Artists Need Your Help

PLEASE HELP and PRAY for OUR FAMILY IN HAITI

Help My Mother and Brother from HAITI PLEASE

Urgent Help for Marc Henry and his family in Haiti

Help Michaël in Humanitarian and Political Crisis in Haïti

Lycender Chery & Family

Trapped in Port au Prince, Haiti

Help Rosemica have surgery for her tumor!

Help My Family escape from ruthless gangs

Haitian Orphanage School: Classique Mixte du Rivag

Help Support a Hard Working Mother of Two

Haiti Emergency Relief of artist community

Help Save Gabe's Life and get him from Haiti to US

Aid for Haitian Artist Mario and his Granddaughter

Haitian-Owned Businesses

Kreyol Essence

LS Cream Liqueur

Creole Me Up

Caribbrew

Tisaksuk

Fanm Djanm

Makaya Chocolate

Kòmsi Like

Créations Dorées

Aeva Beauty

Levie's Essential Care

Bel Ti Boujique

It’s Seasoned™

Cremas Absalon

Kreyol Pale Creole Konprann

VagEsteem

Bijou Lakay

V.BELLAN

AYITI Gallery

#reblog if you want I think this is so interesting and important though#rae’s rambles#Haiti#haiti crisis#free haiti#signal boost#Sudan#Palestine#free palestine#free congo#free gaza#fundraiser#gofundme#information#politics#Congo#dr congo#ceasefire#fundraising#mutual aid#history#infographic#learning#art#artists on tumblr#all eyes on rafah#all eyes on palestine#all eyes on gaza#education#lol

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

imperialism and science reading list

edited: by popular demand, now with much longer list of books

Of course Katherine McKittrick and Kathryn Yusoff.

People like Achille Mbembe, Pratik Chakrabarti, Rohan Deb Roy, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, and Elizabeth Povinelli have written some “classics” and they track the history/historiography of US/European scientific institutions and their origins in extraction, plantations, race/slavery, etc.

Two articles I’d recommend as a summary/primer:

Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. May 2016.

Kathryn Yusoff. “The Inhumanities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020.

Then probably:

Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. “Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times.” Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives. 2023.

Sharae Deckard. “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden.” 2010. (Chornological overview of development of knowledge/institutions in relationship with race, slavery, profit as European empires encountered new lands and peoples.)

Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017, (Interesting case study. US corporations were building fruit plantations in Latin America and rubber plantations in West Africa during the 1920s. Medical doctors, researchers, and academics made a strong alliance these corporations to advance their careers and solidify their institutions. By 1914, the director of Harvard’s Department of Tropical Medicine was also simultaneously the director of the Laboratories of the Hospitals of the United Fruit Company, which infamously and brutally occupied Central America. This same Harvard doctor was also a shareholder in rubber plantations, and had a close personal relationship with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which occupied West Africa.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties.” 2008. (Case study of how British wealth and industrial development built on botany. Examines Joseph Banks; Kew Gardens; breadfruit; British fear of labor revolts; and the simultaneous colonizing of the Caribbean and the South Pacific.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” 2014. (Indigenous knowledge systems; “nuclear colonialism”; US empire in the Pacific; space/satellites; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.)

Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal #115, February 2021. (”Pest control”; termites; mosquitoes; fear of malaria and other diseases during German colonization of Africa and US occupations of Panama and the wider Caribbean; origins of some US institutions and the evolution of these institutions into colonial, nationalist, and then NGO forms over twentieth century.)

Some of the earlier generalist classic books that explicitly looked at science as a weapon of empires:

Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World; Delbourgo’s and Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World; the anthology Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World; Canzares-Esquerra’s Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World.

One of the quintessential case studies of science in the service of empire is the British pursuit of quinine and the inoculation of their soldiers and colonial administrators to safeguard against malaria in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia at the height of their power. But there are so many other exemplary cases: Britain trying to domesticate and transplant breadfruit from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to feed laborers to prevent slave uprisings during the age of the Haitian Revolution. British colonial administrators smuggling knowledge of tea cultivation out of China in order to set up tea plantations in Assam. Eugenics, race science, biological essentialism, etc. in the early twentieth century. With my interests, my little corner of exposure/experience has to do mostly with conceptions of space/place; interspecies/multispecies relationships; borderlands and frontiers; Caribbean; Latin America; islands. So, a lot of these recs are focused there. But someone else would have better recs, especially depending on your interests. For example, Chakrabarti writes about history of medicine/healthcare. Paravisini-Gebert about extinction and Caribbean relationship to animals/landscape. Deb Roy focuses on insects and colonial administration in South Asia. Some scholars focus on the historiography and chronological trajectory of “modernity” or “botany” or “universities/academia,”, while some focus on Early Modern Spain or Victorian Britain or twentieth-century United States by region. With so much to cover, that’s why I’d recommend the articles above, since they’re kinda like overviews.Generally I read more from articles, essays, and anthologies, rather than full-length books.

Some other nice articles:

(On my blog, I’ve got excerpts from all of these articles/essays, if you want to search for or read them.)

Katherine McKittrick. “Dear April: The Aesthetics of Black Miscellanea.” Antipode. First published September 2021.

Katherine McKittrick. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe. 2013.

Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” A chapter in: Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. 2004.

Kathleen Susan Murphy. “A Slaving Surgeon’s Collection: The Pursuit of Natural History through the British Slave Trade to Spanish America.” 2019. And also: “The Slave Trade and Natural Science.” In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History. 2016.

Timothy J. Yamamura. “Fictions of Science, American Orientalism, and the Alien/Asian of Percival Lowell.” 2017.

Elizabeth Bentley. “Between Extinction and Dispossession: A Rhetorical Historiography of the Last Palestinian Crocodile (1870-1935).” 2021.

Pratik Chakrabarti. “Gondwana and the Politics of Deep Past.” Past & Present 242:1. 2019.

Jonathan Saha. “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017.

Zoe Chadwick. “Perilous plants, botanical monsters, and (reverse) imperialism in fin-de-siecle literature.” The Victorianist: BAVS Postgraduates. 2017.

Dante Furioso: “Sanitary Imperialism.” Jeremy Lee Wolin: “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.” Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” Andrew Herscher and Ana Maria Leon. “At the Border of Decolonization.” All from e-flux.

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. 2 October 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “Introduction: Nonhuman Empires.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (1). May 2015.

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017).

Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner. “Monster as Medium: Experiments in Perception in Early Modern Science and Film.” e-flux. March 2021.

Lesley Green. “The Changing of the Gods of Reason: Cecil John Rhodes, Karoo Fracking, and the Decolonizing of the Anthropocene.” e-flux Journal Issue #65. May 2015.

Martin Mahony. “The Enemy is Nature: Military Machines and Technological Bricolage in Britain’s ‘Great Agricultural Experiment.’“ Environment and Society Portal, Arcadia. Spring 2021.

Anna Boswell. “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” 2018. And; “Climates of Change: A Tuatara’s-Eye View.”2020. And: “Settler Sanctuaries and the Stoat-Free State." 2017.

Katherine Arnold. “Hydnora Africana: The ‘Hieroglyphic Key’ to Plant Parasitism.” Journal of the History of Ideas - JHI Blog - Dispatches from the Archives. 21 July 2021.

Helen F. Wilson. “Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes.” Environment and Planning. July 2019.

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Kirsten Greer. “Zoogeography and imperial defence: Tracing the contours of the Neactic region in the temperate North Atlantic, 1838-1880s.” Geoforum Volume 65. October 2015. And: “Geopolitics and the Avian Imperial Archive: The Zoogeography of Region-Making in the Nineteenth-Century British Mediterranean.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2013,

Marco Chivalan Carrillo and Silvia Posocco. “Against Extraction in Guatemala: Multispecies Strategies in Vampiric Times.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. April 2020.

Laura Rademaker. “60,000 years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

Paulo Tavares. “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazon’s Deep History.” Architecture in the Anthropocene. Edited by Etienne Turpin. 2013.

Kathryn Yusoff. “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time.” Social Text. 2019. And: “The Anthropocene and Geographies of Geopower.” Handbook on the Geographies of Power. 2018. And: “Climates of sight: Mistaken visbilities, mirages and ‘seeing beyond’ in Antarctica.” In: High Places: Cultural Geographies of Mountains, Ice and Science. 2008. And:“Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene.” 2017. And: “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” 2017.

Mara Dicenta. “The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego.” Arcadia. Spring 2020.

And then here are some books:

Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Helen Tilley, 2011); Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Londa Schiebinger, 2004)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten A. Greer); The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge (Arndt Brendecke, 2016); Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2014)

Anglo-European Science and the Rhetoric of Empire: Malaria, Opium, and British Rule in India, 1756-1895 (Paul Winther); Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands (Andrew Stuhl)

Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (Britt Rusert, 2017); Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (Jonathan Saha)

The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa (Bernhard Gissibl, 2019); Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century (Edited by Adriana Craciun and Mary Terrall, 2019)

Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500-1850 (Cameron B. Strang); The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022); Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Allison Bigelow, 2020); The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods); American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Megan Raby, 2017); Producing Mayaland: Colonial Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism (Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, 2023)

Domingos Alvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (James Sweet, 2011); A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Anya Zilberstein, 2016); Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines (Sarah Steinbock-Pratt, 2019); Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea, 1800-1970 (Edited by Anderson, Rozwadowski, et al, 2016)

Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Maile Arvin); Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (Janet Dorothy Larkin, 2018); A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (Michael A. Verney, 2022); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013)

Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Daniela Cleichmar, 2012); Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India (Arnab Dey, 2022); Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopoeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Edited by Crawford and Gabriel, 2019)

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment (Hi’ilei Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart, 2022); In Asian Waters: Oceanic Worlds from Yemen to Yokkohama (Eric Tagliacozzo); Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017); Turning Land into Capital: Development and Dispossession in the Mekong Region (Edited by Hirsch, et al, 2022); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski); Colonial Fantasies, Imperial Realities: Race Science and the Making of Polishness on the Fringes of the German Empire, 1840-1920 (Lenny A. Urena Valerio); Against the Map: The Politics of Geography in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Adam Sills, 2021)

Under Osman’s Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail, 2017); Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Jim Endersby); Proving Grounds: Militarized Landscapes, Weapons Testing, and the Environmental Impact of U.S. Bases (Edited by Edwin Martini, 2015)

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Multiple authors, 2007); Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Peter Redfield); Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Andrew Togert, 2015); Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of ‘Green’ Capitalism (Hannah Holleman, 2016); Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and the Reordering of Biodiversity Governance (Katja Grotzner Neves, 2019)

Botanical Entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England (Anna K. Sagal, 2022); The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Harriet Ritvo); Rubber and the Making of Vietnam: An Ecological History, 1897-1975 (Michitake Aso); A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Kathryn Yusoff, 2018); Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt (Jessica Barnes, 2023); No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers); Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1768-1941 (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017); Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia (Douglas C. Harris, 2001); Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep Time (Edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Jakelin Troy); Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Joyce Chaplin, 2001)

American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 (Jeremy Zallen); Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Erik Linstrum, 2016); Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Water (James Pettifer and Mirancda Vickers, 2021); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti); Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea (David Fedman)

Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Julie Cruikshank); The Fishmeal Revolution: The Industrialization of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem (Kristin A. Wintersteen, 2021); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); An Imperial Disaster: The Bengal Cyclone of 1876 (Benjamin Kingsbury, 2018); Geographies of City Science: Urban Life and Origin Debates in Late Victorian Dublin (Tanya O’Sullivan, 2019)

American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (John Krige, 2006); Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Ann Laura Stoler, 2002); Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire (Faisal H. Husain, 2021);

The Sanitation of Brazil: Nation, State, and Public Health, 1889-1930 (Gilberto Hochman, 2016); The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia (James Hevia); Japan’s Empire of Birds: Aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and Transwar Ornithology (Annika A. Culver, 2022)

Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation (Jose E. Martinez, 2021); Sound Relations: Native Ways of Doing Music History in Alaska (Jessica Bissette Perea, 2021); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Andrew Zimmerman, 2001)

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Multiple authors, 2016); The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (Katherine Johnston, 2022); Seeking the American Tropics: South Florida’s Early Naturalists (James A. Kushlan, 2020); The Postwar Origins of the Global Environment: How the United Nations Built Spaceship Earth (Perrin Selcer, 2018)

The Colonial Life of Pharmaceuticals: Medicines and Modernity in Vietnam (Laurence Monnais); Quinoa: Food Politics and Agrarian Life in the Andean Highlands (Linda J. Seligmann, 2023) ; Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, 2017); Spawning Modern Fish: Transnational Comparison in the Making of Japanese Salmon (Heather Ann Swanson, 2022); Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Mark Bassin, 2000); The Usufructuary Ethos: Power, Politics, and Environment in the Long Eighteenth Century (Erin Drew, 2022)

Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures (Anita Mannur, 2022); On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, 1830-1890 (Philip Gooding, 2022); All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation Through Species Acclimitization, from Colonial Australia to the World (Pete Minard, 2019)

Practical Matter: Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687-1851 (Margaret Jacob and Larry Stewart); Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Setller Colonialism (Jarrod Hore, 2022); Timber and Forestry in Qing China: Sustaining the Market (Meng Zhang, 2021); The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (David A. Chang);

Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (Christine Keiner); Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire (Mauro Jose Caraccioli); Two Years below the Horn: Operation Tabarin, Field Science, and Antarctic Sovereignty, 1944-1946 (Andrew Taylor, 2017); Mapping Water in Dominica: Enslavement and Environment under Colonialism (Mark W. Hauser, 2021)

To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire (Jason Smith, 2018); Fir and Empire: The Transformation of Forests in Early Modern China (Ian Matthew Miller, 2020); Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500-1950 (Sandra Swart and Greg Bankoff, 2007)

Science on the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya (Lachlan Fleetwood, 2022); Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i (John Ryan Fisher, 2017); Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

An Ecology of Knowledges: Fear, Love, and Technoscience in Guatemalan Forest Conservation (Micha Rahder, 2020); Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Debjani Bhattacharyya, 2018); Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka); Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity (Ann Elias, 2019); Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (Angela Thompsell, 2015)

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Haiti's 220th anniversary

Two hundred and twenty years ago, former slaves and free people of color accomplished the seemingly impossible: defeating one of the most formidable European armies of the day and establishing a new state where bondage, as it existed before 1791, would be forever abolished.

For those who have followed this blog since 2013, you know that I (admin A) have rarely allowed myself any sentimentality when discussing Haitian history. I have tried to present a nuanced portrait of Haiti’s past by addressing the weight of the many isms that have plagued its history (colonialism, racism, neoliberalism…) and by taking a critical look at the role of Haitian leaders throughout all these episodes.

Two hundred and twenty years after the unthinkable, Haiti finds itself without a president, grappling with what seems to be a permanent problem of armed gangs, little security, renewed multifaceted tensions with its Dominican neighbour, and on the brink of a new UN occupation through a Kenyan mission. The young woman who started this blog a decade ago would have said that there are little reasons for us as Haitians to celebrate—not because of a difficulty appreciating the great shoulders on which we stand, but because, at twenty-two years old, I didn’t believe in what I felt was useless romanticism binding us to a distorted past while also blinding us to the reality of the disastrous present.

Today, it’s not so much that I find much to rejoice in given the current state of affairs. It’s that I realize, what is the point of all this if there is no hope? Why this blog, why study the history of Haiti at all, why care about the country? For those of us with family there, why not temporarily send money in the hope of helping them relocate here, there, and anywhere except Haiti? Why not congratulate the complete erosion of Haitian sovereignty, as post-1986 Haiti, and especially Haiti of the last two decades, has shown so vividly the complete utter failure of its foreign-backed governing class?

I don’t know what hope is supposed to look like in this situation. Hope for what? Hope for a change under what conditions, under whose authority? On what would this hope be grounded? Perhaps, despite the best efforts of my twenty-two-year-old self, I am becoming as naive and sentimental as the people I silently criticized then...

Perhaps, however, I recognize that Haiti does matter. Even the most cynical among us would admit that there is something profoundly radical in breaking the bonds of slavery, in affirming that people of African descent could not be stripped of their humanity, that there is something poetic in saying “no” in the face of impressive odds. Newly independent Haiti did not live up to some of the promises of its complicated Revolution. The 1825 French imposition of an indemnity severely affected freshly formed Haiti (beyond the 19th century), but it does not excuse the incompetence of Haitian governments, then and now. Haiti could, may have, and I certainly hope, will change, will remember what 1804 ought to have meant.

Perhaps, especially for the people who currently live in Haiti, particularly the women of all ages who face the constant threats of sexual violence, Haiti has a responsibility to itself, to its unprecedented idealism, to all of us.

Given all these reasons, I find it necessary to maintain a guarded optimism, acknowledging that ideas hold significance and possess the potential to materialize into reality.

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love Masisi (Pierre Alexandre)

Gender: Non binary (they/them) (she/her in drag)

Sexuality: Queer

DOB: 9 July 1977

Ethnicity: Afro Haitian

Nationality: American

Occupation: Drag artist, reality star

#Love Masisi#Pierre Alexandre#qpoc#queerness#lgbtq#non binary#queer#1977#black#haitian#poc#afro carribean#caribbean#hispanic#drag artist#reality star

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

The US occupation of Haiti from 1915-34 raises a key point in how US military structure at the time worked:

While the Army spent WWI fighting in Europe, the Marine Corps began its path to WW2 with the occupations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, where the WW2 'Old Breed' learned their trade in actual combat operations against Haitian and Dominican resistance. This was the other side of Black history in the era of the World Wars, and the first shadows of what would recur during the Cold War. The US occupation of Haiti would last until 1934, one of multiple such occupations by US power.....and in no case did US imperialism at Haiti's expense actually improve things for Haitians.

The equal reality is that where the Army was sent to fight other conventional forces, the US military treated the Marine Corps as a colonial force in the Americas, with the Army playing its own major colonial role in the Philippines, not least for what would ultimately prove the entirely valid fear of how Japan would react as its own desire to assert itself in East Asia grew. This is the hidden underbelly of just how and why the WWII Marine Corps was so good at conducting opposed amphibious operations and where they honed the skill that went into this.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#military history#american history#haitian history#us occupation of haiti 1915-34#us marine corps

0 notes

Text

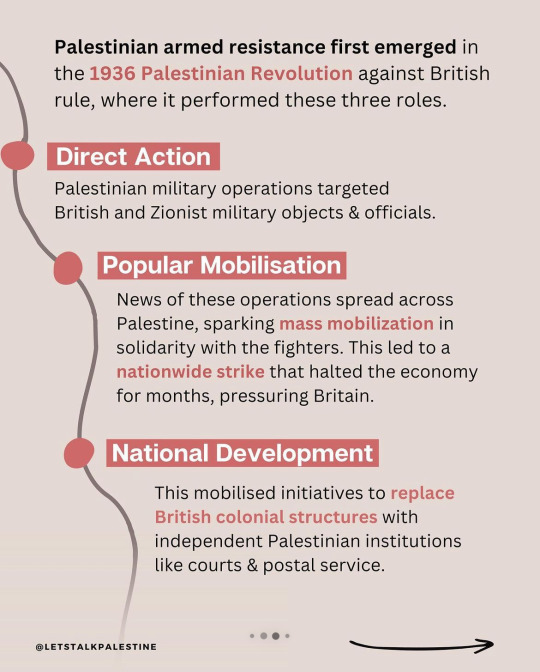

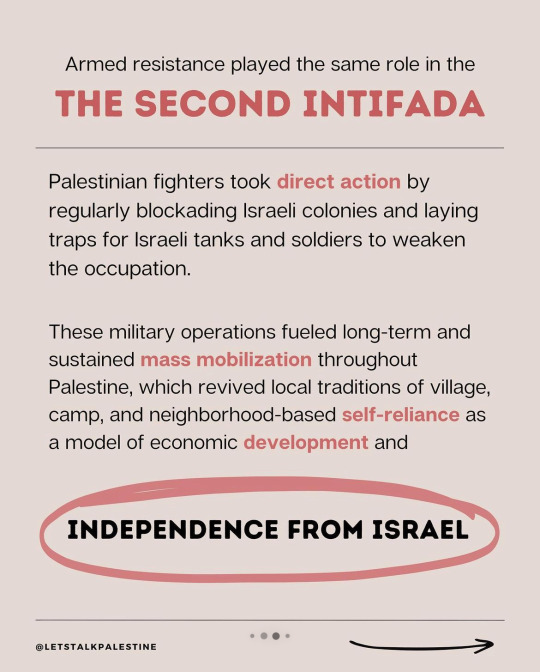

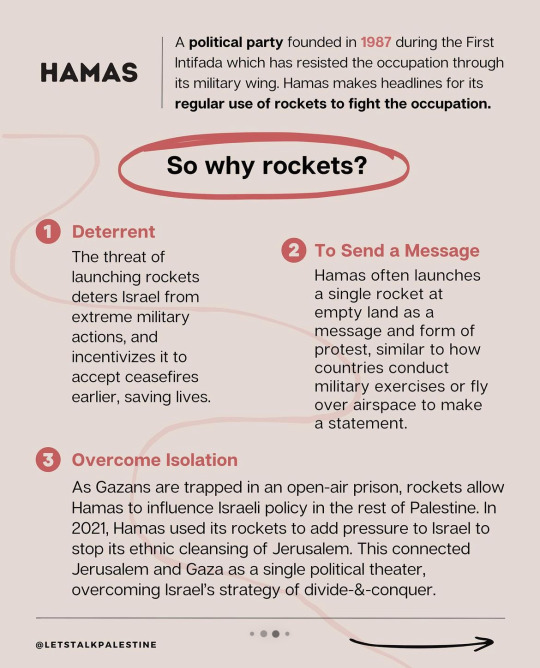

image description by @swosheep

ID 1: all images are screenshots from an Instagram post by letstalkpalestine. They have a light beige background. The first image is a title, reading: "Lets talk armed resistance". The subtitle reads: "Analysing why and how Palestinians resist militarily".

ID 2: The second image begins with an illustration of a pair of fists breaking free from shackles. Below the illustration, the body text reads: "In the face of colonization and violent ethnic cleansing, Palestinians are forced to engage in an armed struggle in order to defend themselves and liberate their land." Palestinian armed resistance has a long history, first deployed against the British occupation. Today, it's a tool used to pursue different political goals as part of the long-term objective of national liberation."

ID 3: The third image is titled: "What is armed resistance?" The body text reads: "Since the dawn of time, oppressed groups have used armed resistance as a legitimate way to free themselves from colonial powers. When a group is occupied by a violent power, which seeks to dominate, exploit, or harm them, resistance is not just a right, but a communal duty." The words 'communal duty' are very large and circled in orange. The bottom portion of the image looks like a piece of lined paper. It reads: "Examples of armed resistance for liberation: Haitian Revolution [Haitian flag], Algerian Independence Struggle [Algerian flag], Zapatista Movement [Zapatista flag], African National Congress [African National Congress flag]."

ID 4: The fourth image is titled: "Israel's military is one of the most powerful in the world". The body text reads: "Freeing Palestine by defeating Israel's military isn't feasible. This is why armed resistance is a political tool used for mid-term tactical political goals as part of a bigger long-term struggle." A subtitle reads: "The three elements of armed resistance according to Palestinian intellectual Basil al-Araj:". The elements are listed left to right and have illustrations below them. They are: "Direct Action", with an illustration of a raised fist. "Popular Mobilization", with an illustration of four people with arrows pointing at them. "Development", with an illustration of a graph going up.

ID 5: The fifth image is split into three sections. The first section is titled: "Direct action", in orange, and has an illustration of a raised fist, also orange. The text beside it is black and says: "Includes both violent and non-violent actions such as military operations, protests, boycotts, and strikes. The purpose of direct action is to slowly weaken the occupation and spread political awareness." The second section is titled "Popular Mobilization", in orange, and has an illustration of four people with arrows pointing at them, also orange. The text beside it is black and says: "An organized populace raising awareness and collectively uniting around a specific demand or vision. Organized masses build upon direct action through large-scale protests." The final section is titled "Development", in orange, and has an illustration of a graph going upwards, also orange. The text beside it is black and says: "The process of building independent institutions and economic sufficiency free from external influence to empower the community."

ID 6: The sixth image has no title. The body text reads: "Palestinian armed resistance first emerged in the 1936 Palestinian Revolution against British rule, where it performed these three roles." Below, there is a stylized bullet list with three points, which have titles written in white text on an orange background. The first point is titled "Direct Action", and reads: "Palestinian military operations targeted British and Zionist military objects and officials." The second point is titled "Popular Mobilisation", and reads: "News of these operations spread across Palestine, sparking mass mobilization in solidarity with the fighters. This led to a nationwide strike that halted the economy for months, pressuring Britain." The third point is titled "National Development", and reads: This mobilised initiatives to replace British colonial structures with independent Palestinian institutions like courts and postal services.

ID 7: The seventh image is titled: "Armed resistance played the same role in The Second Intifada.". The body text reads: "Palestinian fighters took direct action by regularly blockading Israeli colonies and laying traps for Israeli tanks and soldiers to weaken the occupation. These military operations fueled long-term and sustained mass mobilization throughout Palestine, which revived local traditions of village, camp, and neighborhood-based self-reliance as a model of economic development and independence from Israel." The words 'independence from Israel' are in large bold text, circled in orange.

ID 8: The eight image is titled: "Hamas". Text to the right of the title reads: "A political party founded in 1987 during the First Intifada which has resisted the occupation through its military wing. Hamas makes headlines for its regular use of rockets to fight the occupation." A subtitle, circled in orange, reads: "So why rockets?" Below the subtitle there is a numbered list, which reads: "1. Deterrent. The threat of launching rockets deters Israel from extreme military actions, and incentivizes it to accept ceasefires earlier, saving lives. 2. To Send a Message. Hamas often launches a single rocket at empty land as a message and form of protest, similar to how countries conduct military exercises or fly over airspace to make a statement. 3. Overcome Isolation. As Gazans are trapped in an open-air prison, rockets allow Hamas to influence Israeli policy in the rest of Palestine. IN 2021, Hamas used its rockets to add pressure to Israel to stop its ethnic cleansing of Jerusalem. This connected Jerusalem and Gaza as a single political theater, overcoming Israel's strategy of divide-and-conquer."

ID 9: the ninth image is titled: "The Lion's Den", and subtitled: "A new youth-led resistance group in the West Bank city of Nablus." The body text reads: "Their short-term goals are to defend the city from Israeli raids, disrupt settlements, and weaken Israeli control by targeting surrounding checkpoints. Their long-term goal is to create mass consciousness among Palestinians to create a 'generation of numbers', after which a 'generation of liberation' will come. They lead mass mobilizations, such as strikes and protests, to create this consciousness. Their popularity has challenged the corrupt Palestinian Authority, presenting a new model of leadership: decentralised and youth-led, uniting members of all parties and factions."

ID 10: the tenth image is titled "Moral right". The body text reads: "Colonized people have the right to defend themselves, their children, and their communities in the face of an army which kills them regularly." A quote by @/mohammedelkurd reads: "Those resisting, those born and raised in violence, do not require the approval of Ivy League students or corporate television anchors who routinely turn a blind eye to the decades of debilitating, systematic, and material violence of the Israeli regime." The quote is placed within orange quote marks and is in large bolded italics for emphasis. The body text continues: "Peace is not the absence of violence. Peace needs justice, dignity, and liberation. Armed resistance is a tactical tool to create a future where people no longer need to defend themselves. Only then is true peace possible." The final sentence is written in large orange text.

#palestine#israel#resources#bipoc#reaux speaks#resistance#genocide#colonialism#anti zionism#ethnic cleansing#community#revolution#instagram#free palestine

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday, Jacques Roumain! (June 4, 1907)

One of the most prominent and acclaimed writers in Haitian history, Jacques Roumain was born in Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti, to wealthy parents; his grandfather had briefly been President of Haiti from 1912 to 1913. Roumain was active in the struggle against the United States' 1915-1934 occupation of Haiti, and in 1934 became a founder of the Communist Party of Haiti. His political activities led to persecution, and he was frequently arrested before finally being exiled from his homeland. He spent his years in exile associating with the budding pan-African movement, becoming a friend to figures such as Langston Hughes, who would later translate his work into English. Roumain was allowed to return to Haiti after a change in government in the 1940s, and became a diplomat in service of the Haitian state. However, he died soon after at the young age of 37, leaving behind a remarkable body of work.

"We're this country, and it wouldn't be a thing without us, nothing at all. Who does the planting? Who does the watering? Who does the harvesting? Coffee, cotton, rice, sugar cane, caco, corn, bananas, vegetables, and all the fruits, who's going to grow them if we don't? Yet with all that, we're poor, that's true. We're out of luck, that's true. We're miserable, that's true. But do you know why, brother? Because of our ignorance. We don't know yet what a force we are, what a single force - all the peasants, all the Negroes of the plain and hill, all united. Some day, when we get wise to that, we'll rise up from one end of the country to the other. Then we'll call a General Assembly of the Masters of the Dew, a great big coumbite of farmers and we'll clear out poverty and plant a new life."

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This book presents a brilliant analysis of the neoliberal policies imposed on Haiti by international institutions. Dupuy skillfully connects decades of extractive foreign interventions in Haiti, from the US occupation to the aftermath of Jovenel Moïse’s assassination. Haiti since 1804 points the way toward a future in which Haitians might finally regain sovereignty over their own economy and government."

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

"

Haiti’s government declared a state of emergency and nighttime curfew late Sunday in an effort to regain control of the streets after a huge popular uprising over the weekend saw armed fighters storm the country’s two biggest prisons.

The 72-hour state of emergency took effect immediately. The government said it would set out to find the escapees from prison. “The police were ordered to use all legal means at their disposal to enforce the curfew and apprehend all offenders,” said a statement from Finance Minister Patrick Boivert, acting prime minister.

Prime Minister Ariel Henry traveled abroad last week to try to salvage international bourgeois support for bringing in a US-backed security force to pacify the country in its conflict with increasingly militant organizations countrywide."

...

"But the siege Saturday night of the National Penitentiary came as a shock even to Haitians accustomed to living under the constant pressure due to colonial misrule. Almost all of the estimated 4,000 inmates fled in the jailbreak, leaving the usually criminally overcrowded facility empty Sunday with no prison guards in sight and plastic sandals, clothing and furniture strewn across the concrete patio. Three bodies with gunshot wounds lay at the prison entrance."

...

"Among the few dozen who chose to stay in the prison are 18 former Colombian soldiers accused of working as mercenaries in the July 2021 assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse. Amid the clashes Saturday night, several of the Colombians shared a video pleading for their lives.

'Please, please help us,” one of the men, Francisco Uribe, said in the message widely shared on social media. “They are massacring people indiscriminately inside the cells.' "

....

"A second Port-au-Prince prison containing about 1,400 inmates was also overrun. Gunmen also occupied the nation’s top soccer stadium in a highly symbolic display of defiance Internet service for many residents was down as Haiti’s top mobile network said a fiber-optic cable connection was slashed during the rebellion."

..

"The rebellion is significant since the president, who is US-backed and unelected, has been organizing an international occupation force to impose its will on the country. There has been no notable progress on social issues, economic issues, or reparations for US and French destruction of the country.

The violence must be understood in this context."

#ftp#fire to the prisons#fuck the poilce#acab#free them all#prison abolition#anticapitalism#anarchism#antifascism#haiti#free haiti

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This series has repeatedly made reference to obscure events in the Dominican Republic from 1961 to 1966 which culminated in an American military invasion. They are relatively unknown and appear murky to outsiders. They united the CIA, the non-violent section of the civil rights movement, and a group of labour movement figures with links to Norman Thomas' post-Eugene Debs Socialist Party of America, the Democratic Socialist Party of today, and the Neoconservative movement that planned the Iraq War of 2003. The next two (maybe three) parts of the series will hopefully elucidate some of these events for readers. The previous part, Part 5, can be read here.

1965 was the fifth time America invaded the Dominican Republic. The fourth was in 1916, initiating an occupation that went on until 1924. America also controlled the nation's foreign trade from 1904 to 1947, collecting 50% of its revenue by heavily taxing its people on imports in order to pay off European powers with Citibank getting a commission to do the counting. These events bookended the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, 1930 to 1961. This resulted in a weak state unable to defend itself or the foreign corporations who wanted to invest in it.

Trujillo's government was a revolution of sorts because he directly took his methods from the mafia to govern. He'd spent years as a plantation overseer by day and gang leader by night, then joined the American-trained Dominican police and became an army officer. He learned how to use violence and manipulation to get what he wanted as well as how to pleas foreigners. In one case, he'd been sent by the occupiers to deal with a guerilla army in the interior. He was so successful that the American troops covered the reports of rapes and tortures he committed while doing so. As one of his trainers said, "He thinks just like a marine!" When the Americans withdrew, he retreated to a former castle that served as a military base, building up power until he could take advantage of a crisis and overthrow the government. Once in power, he set to creating state capacity for his rule by shaking down local industries one by one, collecting revenue and inserting loyalists into their leadership while allowing them the benefits of state backing through investment and coordination. He was so successful that he was the longest serving leader in the Caribbean's history at the time of his death.

Trujillo used a similar system of creating win-win situations to persuade American diplomats and investors to support him. He went on a charm offensive, building a tourism sector internally and using his one-time son-in-law, playboy Porfirio Rubirosa, as an ambassador and press officer. Rubirosa was not only wildly charismatic, he was also reported by Truman Capote to have an eleven inch penis. After divorcing Trujillo's daughter, he married two French actresses and the two richest women in the world back to back, making bank on his divorce settlements. Like much of the Dominican Republic's elite, he lived a charmed life, racing/crashing Ferraris and airplanes (including a B-25 bomber) internationally. Both he and his former father-in-law lived part of the year in lavish apartments in New York City, racing Ferraris and buying out brothels. Some of the money came from Dominican visas that Rubirosa sold to German Jews fleeing the Holocaust and Spaniards fleeing Franco. Trujillo had retreated there to convince the world that he had changed his ways after spearheading the massacre of tens of thousands of Haitians in his country in 1937. In the shadows he worked to mastermind a comeback, making it seem like his people organically wanted him again in the 1942 show elections. He won 100% of the vote.

By 1947, the Cold War was on. Most people forget that this was a process initiated by a strong and muscular liberalism that had just defeated fascism and felt it could do the same to communism. Liberal intelligentsia in American government had undertaken a decade-long march through the institutions and created a new setup for the global economy with the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, the United Nations, and Bretton Woods. It seemed to many in the Third World that America had turned over a new leaf and was ready to support democracy abroad. For the entrenched right wing forces in Latin America, however, it seemed like business as usual. Just as he had declared war on the Nazis, Trujillo now worked to find a communist menace to kill to serve American interests. He used his agents to create a fake Marxist-Leninist party as opposition to run against him in the 1947 election. After picking up 92% of the vote, he used their supposed allegiance to Moscow to crack down on them, winning himself plaudits in Congress.

For many in Latin America, this was the last straw. In Cuba, 1200 men came together in what was termed the Caribbean Legion. Mostly exiles from Latin American dictatorships and sympathizers, they were ready to kill and die for liberalism. Some had fought in the Spanish Civil War and escaped death at the hands of the Franco regime when Trujillo had chosen to accept refugees from Europe as part of his developmental push, only to find their political allegiance was to socialism above all. They were backed by the elected leader of Cuba, Ramon Grau, who saw them as a way to topple a nearby enemy. They also pulled support from the president of Guatemala, Juan Jose Arevalo, who like his successor Jacobo Arbenz was an anti-communist liberal. Among the membership was Carlos Prio, the next president of Cuba, Juan Bosch, the most famous anti-Trujillo Dominican, Romulo Betancourt, a future president of Venezuela, Jose Figueres, the next president of Costa Rica, and a law student/basketball player at Havana University named Fidel Castro.

Figueres was a strange figure, perhaps the most fascinating of the Cold War. A plantation owner, he described himself as a "farmer-socialist". He invested his money in improving the living conditions of his workers, certain that it would make them more productive. He came to power with the help of the Legion in a very odd way, in a civil war that belongs with those pictures of Wikipedia where both sides are in odd alliances, with the right wing Nicaraguan dictatorship backing the Catholic Church and the Communist Party against Figueres' oligarch allies, supported by both America and the Guatemalan government it would later overthrow. Figueres immediately defenestrated those allies and took power for himself despite his talk of democracy, abolishing the army, nationalizing all banks, guaranteeing public education, giving citizenship to black migrants, giving women the vote, instituting social welfare, and banning the Communist Party. He helped establish the School of the Americas where the American military taught torture techniques and broke off relations with every American-backed dictator in the region. At one point, he was the subject of the only shooting war fought between different branches of the American government, when his State Department friends gave him planes to fight ones provided to Nicaragua by the CIA.

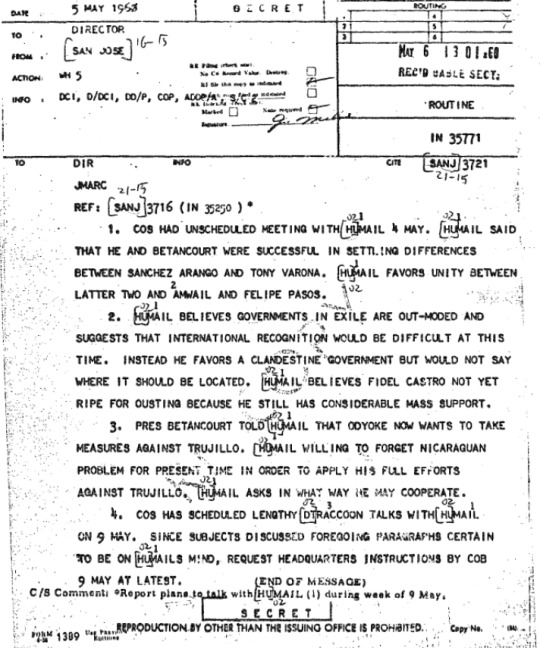

The Caribbean Legion would not have any other successes because it faced a classic problem of liberals during the Cold War: its membership was supportive of social reform, and that made the American government suspect they were secretly communists in disguise. The Legion had wanted to overthrow Trujillo, but the Americans convinced Grau to arrest them and confiscate their weapons. Castro managed to escape by jumping off the ship they were captured on and swimming to shore. Even as doors closed for the Legion, however, others opened. Ironically, it was another section of the American government that would save them. Their patron Figueres' liberal anti-communism had its fans in the CIA, which as an organization staffed largely by liberal WASPs from northeastern Ivy League universities felt that the combination would be sufficient to compete with the Soviets for hegemony among the Latin American peasantry. Figueres ended up on the CIA's payroll directly, codename HUMAIL. A lighter hand would be used for the Legion's membership, however.

26 notes

·

View notes