#India ancient texts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

UNESCO recognizes India’s ancient texts, highlighting their global cultural value. Discover the significance of this honor and what it means for India's literary heritage.

#UNESCO#India ancient texts#Indian heritage#UNESCO recognition#Vedas#Upanishads#Indian manuscripts#cultural heritage#Indian history#global recognition#TheJuniorAge#KidsNewspaper#Newspaper For Children#KidsNewspaperIndia

0 notes

Text

Time calculation in The Ling Mahapuran

Old Indian scriptures and literature are little explored. Majority of the people who follow Hinduism barely get in to the depth of it. Apart from religious values, it contains very rich information which help up to get an idea about the advancement of the civilization back then. If you open up any of the book and start reading, at the first glance it would appear a religious text. As you continue…

#ancient hindu scriptures#Ancient Knowledge System#Brahma#Exploring Hindu Puranas#Gurukul Education System#Hindu Cosmology#Hindu Science and Astronomy#Hindu Scriptural Insights#Hindu Time Calculation#Hindusim#Indian Literature#Indian Religious Texts#Indian Scriptures#Indus valley civilization#Puranas#Purans#Sacred Hindu Texts#Spiritual Dimensions in Hinduism#Spiritual Wisdom#The Ling Mahapuran#Time calculation in Hindusim#Vedas and Puranas#Vedic India#Vedic Knowledge of Time#Vedic Science#Vedic Teachings#Vedic times#Vishnu#Yuga

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

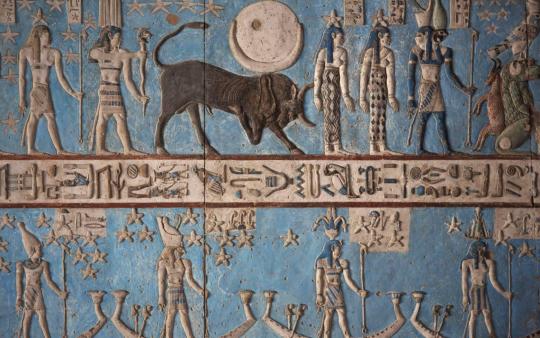

The Ancient History of Astrology: Early Civilizations and The Stars

Astrology, an ancient practice that has captivated civilizations for centuries, holds a rich history deeply intertwined with the development of human civilization. From the earliest recorded civilizations to the present day, astrology has played a signifi

Astrology, an ancient practice that has captivated civilizations for centuries, holds a rich history deeply intertwined with the development of human civilization. From the earliest recorded civilizations to the present day, astrology has played a significant role in shaping our understanding of the cosmos and our place within it. In this blog post, we will delve into some of astrology’s earliest…

View On WordPress

#ancient astrology#ancient babylon#ancient china#ancient civilizations#ancient cultures#ancient egypt#ancient empires#ancient history#ancient india#ancient mesopotamia#ancient rome#ancient sumeria#ancient tablets#ancient texts#ancient wisdom#astral#Astrologer#astrology around the world#astrology chart#astrology in ancient history#astrology in early civilizations#astrology in human history#Astrology Reading#auras#babylonian#Babylonian astrology#Blog#cave paintings#cave paintings of astrology#chakras

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varna Religion

The term Varna (Sanskrit: वर्ण) refers to a traditional social classification system rooted in the religious and philosophical texts of ancient India, particularly those affiliated with Vedic Hinduism. Often translated as “class” or “color,” the Varna system outlines a four-fold division of society based on duties, responsibilities, and ritual status. This system forms one of the central frameworks of Dharma—the cosmic law and moral order—in Hindu thought and has deeply influenced the religious, social, and cultural life of the Indian subcontinent over millennia.

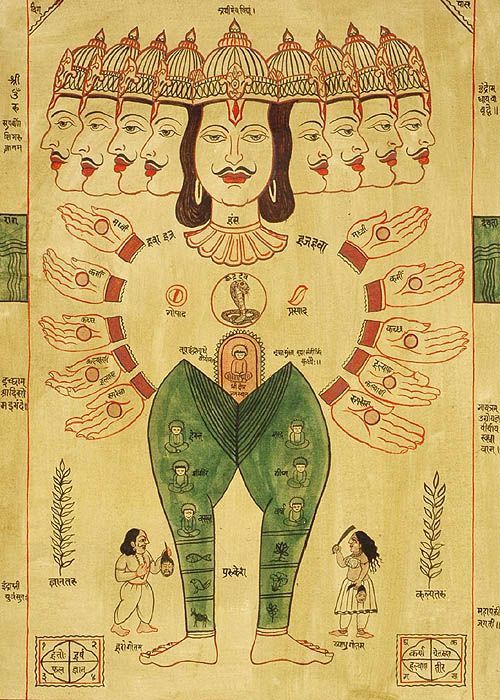

The Varna system is first articulated in the Rigveda, the oldest of the four canonical Vedas, composed circa 1500–1200 BCE. The most famous reference is found in the Purusha Sukta (Rigveda 10.90), a hymn describing the cosmic sacrifice of the primordial being Purusha, from whose body the four Varnas are said to have originated:

Brahmins (priests and scholars) came from Purusha’s mouth,

Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers) from his arms,

Vaishyas (merchants and agriculturists) from his thighs,

Shudras (servants and laborers) from his feet.

This mythological origin reflects the religious conception of a divinely sanctioned social order, where each Varna has a specific role to play in maintaining cosmic balance.

The Brahmins, emerging from the head of Purusha, are portrayed in Vedic texts as the custodians of sacred knowledge (Veda) and the conductors of yajña (ritual sacrifice). Their primary religious function was to serve as intermediaries between the human and divine realms, maintaining the universe through precise ritual performance and recitation of mantras. Brahmins were traditionally forbidden from engaging in commercial or martial activities and were expected to lead lives of celibacy, study (svādhyāya), teaching (adhyāpana), and spiritual detachment.

The concept of Dharma, central to Hindu religious ethics, is integrally tied to Varna. Each Varna is assigned a Svadharma (one's own duty), which delineates the appropriate moral, occupational, and ritual behavior for members of that class. Classical texts such as the Manusmriti (ca. 2nd century BCE – 3rd century CE) and the Bhagavad Gita (circa 200 BCE – 200 CE) elaborate this framework:

Brahmana Dharma: study and teaching of the Vedas, performing sacrifices, giving and receiving alms.

Kshatriya Dharma: governance, warfare, protection of society, justice.

Vaishya Dharma: agriculture, cattle-rearing, trade, and economic activity.

Shudra Dharma: service to the other three Varnas, manual labor, and crafts.

The Bhagavad Gita, in particular, emphasizes the importance of performing one’s own Dharma over adopting that of another, even if the latter seems superior. It frames Varna as stemming from a person’s Guna (qualities) and Karma (actions), thus suggesting a more fluid and metaphysical origin rather than merely hereditary status.

Throughout Indian religious history, the Varna system has been religiously justified through various theological arguments. Classical Hindu theologians such as Adi Shankaracharya (8th century CE) accepted the Varna system as part of Vyavaharika Satya (conventional reality), important for societal functioning, though ultimately sublated in Paramarthika Satya (ultimate reality) through realization of the Atman (Self) and Brahman (Absolute).

Dvaita and Vishishtadvaita schools also recognized Varna as a social necessity grounded in religious ideals. While these theistic traditions emphasized devotion (bhakti) and sometimes challenged ritual elitism, they rarely rejected Varna outright. The Bhakti movement (ca. 7th–17th centuries) offered a partial counterbalance by emphasizing personal devotion over ritual hierarchy, yet even many Bhakti saints operated within or tacitly acknowledged the Varna schema.

A critical religious dimension of the Varna system is its connection to the doctrines of karma and samsara (rebirth). According to Hindu eschatology, the Varna into which one is born is believed to result from accumulated karma from past lives. This framework reinforced both moral responsibility and social stratification, as it positioned Varna not as arbitrary birth, but as an outcome of cosmic justice.

This theological underpinning made social mobility within a lifetime rare, though not theoretically impossible. Scriptural injunctions, including passages in the Mahabharata, do suggest that individuals could shift Varnas based on conduct, knowledge, or spiritual realization—though such transitions were exceptional.

The Dharmaśāstra literature, especially texts like Manusmriti, Yājñavalkya Smriti, and Narada Smriti, extensively codify rules and duties for each Varna, governing aspects such as marriage, diet, clothing, purification rituals, inheritance, and punishment. These codes form the sacral legal tradition of Hindu society, often referred to as Varnashrama Dharma (the duties associated with one's Varna and stage of life).

The Ashrama system (student, householder, forest-dweller, renunciate) is meant to apply across all Varnas but is elaborated in more detail for Brahmins and Kshatriyas. The interplay of Varna and Ashrama structures an ideal Hindu life along religious, ethical, and social dimensions.

While the Varna system is deeply embedded in Hindu religious texts, it has not gone unchallenged within Indian religious traditions. The Śramaṇa movements—notably Buddhism and Jainism—emerged in the 6th century BCE as explicit critiques of Brahmanical orthodoxy and the Varna system. The Buddha rejected the notion that spiritual potential was linked to birth, asserting instead that ethical conduct and meditative insight determined spiritual worth.

Jain philosophy likewise emphasized personal asceticism, nonviolence (ahimsa), and karma without reference to Varna. Despite this, both religions often accommodated existing social norms for pragmatic reasons, and Jain lay communities often retained some form of Varna-like structure.

Scholars distinguish between Varna (the theoretical fourfold classification) and Jati (endogamous, occupation-based subgroups), which constitute the complex and localized caste system of India. While Varna is scriptural and pan-Indian, Jatis are historically developed, regionally varied, and far more numerous (numbering in the thousands).

Religiously, Jati identity has often been retroactively justified through the Varna framework, though in practice, there is not always a direct one-to-one mapping between the two. For example, many Jatis claim higher Varna status than others assign them, leading to hierarchical contestation and fluidity.

During the British colonial period, Orientalist scholars and colonial administrators interpreted the Varna system through a racial and hierarchical lens, often equating it with Western notions of caste and using it to justify colonial rule. These interpretations influenced legal, census, and educational policies that ossified caste identities in ways not always congruent with religious tradition.

In postcolonial India, reform movements such as those led by Swami Vivekananda, Mahatma Gandhi, and B.R. Ambedkar engaged deeply with the Varna system’s religious claims. Gandhi saw Varna as a spiritual division of labor, not hierarchy, and tried to restore its religious ideals in a non-oppressive form. Ambedkar, by contrast, rejected the Varna system outright as religiously sanctioned inequality, eventually converting to Buddhism and initiating a mass conversion movement.

In modern Hinduism, the religious role of the Varna system is contested and diminished. While traditionalists may continue to invoke it as a divine social order, many Hindus today view Varna as an outdated or symbolic concept, irrelevant to personal spirituality. Nonetheless, ritual roles (e.g., priesthood in certain temples) still often reflect Varna assumptions, particularly with the preference for Brahmin priests in Vedic rites.

Movements such as Arya Samaj, ISKCON, and various Dalit spiritual traditions reinterpret or reject Varna in light of universal spiritual access and egalitarian ideals. Yet in orthodox circles, Varna-based classifications retain residual authority, especially regarding marriage alliances, ritual eligibility, and temple administration.

The religious conception of Varna in Hinduism is a multifaceted and enduring phenomenon, deeply interwoven with Indian metaphysics, ethics, and ritual life. While its social implications have changed drastically over time, Varna continues to occupy a complex space in the religious imagination: simultaneously revered, reinterpreted, and resisted. As both a religious cosmology and a social ideal, the Varna system reflects the broader Indian quest to reconcile divine order with human diversity.

#hinduism#indian philosophy#vedic religion#varna system#ancient india#dharma#rigveda#manusmriti#bhagavad gita#hindu philosophy#indian history#religious studies#hindu theology#social stratification#spirituality#eastern philosophy#religious aesthetics#sacred texts#varnashrama dharma#karma and dharma#brahmin traditions#hindu ritual#indology#caste system#hindu culture#sanatana dharma#historical religion#hindu metaphysics#spiritual history#philosophy of religion

0 notes

Text

Sanatana Dharma and Secularism: A Journey Through Ancient Philosophy, Inclusivity, and Modern Relevance

Introduction: The Intersection of Sanatana Dharma and Secularism Sanatana Dharma, often referred to as “the eternal way,” and secularism, a principle advocating the separation of religion from governmental institutions, appear distinct in their origins and applications. However, they share a deep-seated respect for diversity, pluralism, and the freedom of belief. Both Sanatana Dharma and Indian…

#ancient texts#ancient wisdom#Compassion#Cultural Diversity#ethical governance#Inclusivity#Indian leaders#Indian philosophy#Modern Challenges#modern relevance#peace and cooperation#Peaceful Coexistence#Religious Harmony#respect for diversity#Sanatana Dharma#Secularism#secularism in India

0 notes

Photo

The Indus Valley Civilization was a cultural and political entity which flourished in the northern region of the Indian subcontinent between c. 7000 - c. 600 BCE. Its modern name derives from its location in the valley of the Indus River, but it is also commonly referred to as the Indus-Sarasvati Civilization and the Harrapan Civilization. These latter designations come from the Sarasvati River mentioned in Vedic sources, which flowed adjacent to the Indus River, and the ancient city of Harappa in the region, the first one found in the modern era. None of these names derive from any ancient texts because, although scholars generally believe the people of this civilization developed a writing system (known as Indus Script or Harappan Script) it has not yet been deciphered. All three designations are modern constructs, and nothing is definitively known of the origin, development, decline, and fall of the civilization. Even so, modern archaeology has established a probable chronology and periodization: Pre-Harappan – c. 7000 - c. 5500 BCE Early Harappan – c. 5500 - 2800 BCE Mature Harappan – c. 2800 - c. 1900 BCE Late Harappan – c. 1900 - c. 1500 BCE Post Harappan – c. 1500 - c. 600 BCE The Indus Valley Civilization is now often compared with the far more famous cultures of Egypt and Mesopotamia, but this is a fairly recent development. The discovery of Harappa in 1829 CE was the first indication that any such civilization existed in India, and by that time, Egyptian hieroglyphics had been deciphered, Egyptian and Mesopotamian sites excavated, and cuneiform would soon be translated by the scholar George Smith (l. 1840-1876 CE). Archaeological excavations of the Indus Valley Civilization, therefore, had a significantly late start comparatively, and it is now thought that many of the accomplishments and “firsts” attributed to Egypt and Mesopotamia may actually belong to the people of the Indus Valley Civilization. The two best-known excavated cities of this culture are Harappa and Mohenjo-daro (located in modern-day Pakistan), both of which are thought to have once had populations of between 40,000-50,000 people, which is stunning when one realizes that most ancient cities had on average 10,000 people living in them. The total population of the civilization is thought to have been upward of 5 million, and its territory stretched over 900 miles (1,500 km) along the banks of the Indus River and then in all directions outward. Indus Valley Civilization sites have been found near the border of Nepal, in Afghanistan, on the coasts of India, and around Delhi, to name only a few locations. Between c. 1900 - c. 1500 BCE, the civilization began to decline for unknown reasons. In the early 20th century CE, this was thought to have been caused by an invasion of light-skinned peoples from the north known as Aryans who conquered a dark-skinned people defined by Western scholars as Dravidians. This claim, known as the Aryan Invasion Theory, has been discredited. The Aryans – whose ethnicity is associated with the Iranian Persians – are now believed to have migrated to the region peacefully and blended their culture with that of the indigenous people while the term Dravidian is understood now to refer to anyone, of any ethnicity, who speaks one of the Dravidian languages. Why the Indus Valley Civilization declined and fell is unknown, but scholars believe it may have had to do with climate change, the drying up of the Sarasvati River, an alteration in the path of the monsoon which watered crops, overpopulation of the cities, a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia, or a combination of any of the above. In the present day, excavations continue at many of the sites found thus far and some future find may provide more information on the history and decline of the culture.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

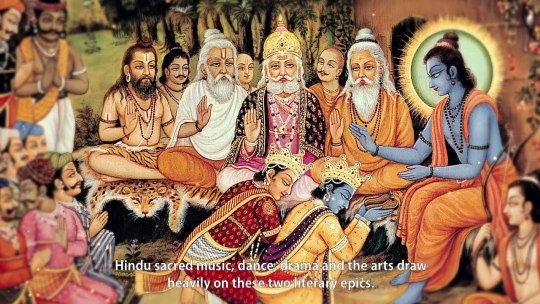

South Asian and Hindu Influences in ATLA (Part 2)

disclaimer: i was raised culturally and religiously hindu, and though i've tried to do my research for this post and pair it with my own cultural knowledge, i'm not an expert on hinduism by any means. should i mess up, please let me know.

please also be aware that many of the concepts discussed in this post overlap heavily with religions such as buddhism and jainism, which might have different interpretations and representations. as i'm not from those religions or cultures, i don't want to speak on them, but if anyone with that knowledge wishes to add on, please feel free.

Part 1

In the previous post, I discussed some of the things ATLA got right in its depictions of desi and hindu cultures. unfortunately, they also got plenty of things wrong - often in ways that leaned towards racist caricatures - so let's break them down, starting with...

Guru Pathik

both the word "guru" and name "pathik" come from sanskrit. pathik means "traveler" or "he who knows the way" while guru is a term for a guide or mentor, similar to a teacher.

gurus were responsible for the very first education systems in ancient india, setting up institutions called gurukuls. students, referred to as disciples, would often spend years living with and learning from their gurus in these gurukuls, studying vedic and buddhist texts, philosophy, music and even martial arts.

however, their learning was not limited merely to academic study, as gurus were also responsible for guiding the spiritual evolution of their disciples. it was common for disciples to meditate, practice yoga, fast for days or weeks, and complete mundane household chores every day in order to instill them with self-discipline and help them achieve enlightenment and spiritual awareness. the relationship between a guru and his disciple was considered a sacred, holy bond, far exceeding that of a mere teacher and student.

aang's training with guru pathik mirrors some of these elements. similar to real gurus, pathik takes on the role of aang's spiritual mentor. he guides aang in unblocking his chakras and mastering the avatar state through meditation, fasting, and self-reflection - all of which are practices that would have likely been encouraged in disciples by their gurus.

pathik's design also takes inspiration from sadhus, holy men who renounced their worldly ties to follow a path of spiritual discipline. the guru's simple, nondescript clothing and hair are reflective of the ascetic lifestyle sadhus are expected to lead, giving up material belongings and desires in order to achieve spiritual enlightenment and, ultimately, liberation from the reincarnation cycle.

unfortunately, this is where the respectful references end because everything else about guru pathik was insensitive at best and stereotypical at worst.

it is extremely distasteful that the guru speaks with an overexaggerated indian accent, even though the iranian-indian actor who plays him has a naturally british accent. why not just hire an actual indian voice actor if the intention was to make pathik sound authentic? besides, i doubt authenticity was the sole intention, given that the purposeful distortion of indian accents was a common racist trope played for comedy in early 2000s children's media (see: phineas and ferb, diary of a wimpy kid, jessie... the list goes on).

furthermore, while pathik is presented a wise and respected figure within this episode, his next (and last) appearance in the show is entirely the opposite.

in the episode nightmares and daydreams, pathik appears in aang's nightmare with six hands, holding what appears to be a veena (a classical indian music instrument). this references the iconography of the hindu deity Saraswati, the goddess of wisdom and knowledge. the embodiment of divine enlightenment, learning, insight and truth, Saraswati is a member of the Tridevi (the female version of the Trimurti), one of the most respected and revered goddesses in the Hindu pantheon... and her likeness is used for a cheap laugh on a character who's already treated as a caricature.

that's bad enough on its own, but when you consider that guru pathik is the only explicitly south asian coded character in the entire show, it's downright insulting. for a show that took so many of its foundational concepts from south asia and hinduism and yet provided almost no desi representation in return, this is just rubbing salt in the wound.

Chakras

"chakra", meaning "circle" or "wheel of life" in sanskrit, refers to sources of energy found in the human body. chakra points are aligned along the spine, with energy flowing from the lowest to the highest point. the energy pooled at the lowest chakra is called kundalini, and the aim is to release this energy to the highest chakra in order to achieve spiritual enlightenment and consciousness.

the number of chakras varies in different religions, with buddhism referencing five chakras while hinduism has seven. atla draws from the latter influence, so let's take a look at the seven chakras:

Muladhara (the Root Chakra). located at the base of the spine, this chakra deals with our basest instincts and is linked to the element of earth.

Swadhisthana (the Sacral Chakra). located just below the navel, this chakra deals with emotional intensity and pleasure and is linked to the element of water.

Manipura (the Solar Plexus Chakra). located in the stomach, this chakra deals with willpower and self-acceptance and is linked to the element of fire.

Anahata (the Heart Chakra). located in the heart, this chakra deals with love, compassion and forgiveness and is linked to the element of air. in the show, this chakra is blocked by aang's grief over the loss of the air nomads, which is a nice elemental allusion.

Vishudda (the Throat Chakra). located at the base of the throat, this chakra deals with communication and honesty and is linked to the fifth classical element of space. the show calls this the Sound Chakra, though i'm unsure where they got that from.

Ajna (the Third Eye Chakra). located in the centre of the forehead, this chakra deals with spirituality and insight and is also linked to the element of space. the show calls it the Light Chakra, which is fairly close.

Sahasrara (the Crown Chakra). located at the very top of the head, this chakra deals with pure cosmic consciousness and is also linked to the element of space. it makes perfect sense that this would be the final chakra aang has to unblock in order to connect with the avatar spirit, since the crown chakra is meant to be the point of communion with one's deepest, truest self.

the show follows these associations and descriptions almost verbatim, and does a good job linking the individual chakras to their associated struggles in aang's arc.

Cosmic Energy

the idea of chakras is associated with the concept of shakti, which refers to the life-giving energy that flows throughout the universe and within every individual.

the idea of shakti is a fundamentally unifying one, stating that all living beings are connected to one another and the universe through the cosmic energy that flows through us all. this philosophy is referenced both in the swamp episode and in guru pathik telling aang that the greatest illusion in the world is that of separation - after all, how can there be any real separation when every life is sustained by the same force?

this is also why aang needing to let go of katara did not, as he mistakenly assumed, mean he had to stop loving her. rather, the point of shedding earthly attachment is to allow one to become more attuned to shakti, both within oneself and others. ironically, in letting go of katara and allowing himself to commune with the divine energy of the universe instead, aang would have been more connected to her - not less.

The Avatar State

according to hinduism, there are five classical elements known as pancha bhuta that form the foundations of all creation: air, water, earth, fire, and space/atmosphere.

obviously, atla borrows this concept in making a world entirely based on the four classical elements. but looking at how the avatar spirit is portrayed as a giant version of aang suspended in mid-air, far above the earth, it's possible that this could reference the fifth liminal element of space as well.

admittedly this might be a bit of a reach, but personally i find it a neat piece of worldbuilding that could further explain the power of the avatar. compared to anyone else who might be able to master only one element, mastering all five means having control of every building block of the world. this would allow the avatar to be far more attuned to the spiritual energy within the universe - and themselves - as a result, setting in motion the endless cycle of death and rebirth that would connect their soul even across lifetimes.

#atla#atla cultural influences#hinduism in atla#welp i thought this would be the last part but i ended up having more to talk about than i thought#so i'll save the book 3 inspirations for the next post#including my absolute favourite combustion man#and by favourite i mean kill it with fire why did you ever think this was okay to do writers

534 notes

·

View notes

Note

Feel like dropping the rant about how "pre-written records = prehistory" is not a good way of conceptualizing history? It's not my area at all so I'm fascinated.

Hah absolutely

It’s a mix of semantics, and word connotations, and the way history gets presented, and tbh legacies of racism.

So. Part of it comes from the distinctions between the academic field and practice of history, and the academic field and practice of archaeology. The practice of history means analyzing the past through written texts and records; the practice of archaeology means analyzing the past through the material remains left behind. This is fine. It refers to the way you approach information about the past and what tools and theories you use to do so. I have no problem with this part!

Of course, it starts to get more complicated when you also have classicists (who study ancient Greek and Roman history primarily through texts but also incorporate some aspects of archaeology) and Assyriologists (ditto but for Mesopotamia), which have their roots in old-school European practices of formal education. There’s also historical archaeology, which is primarily archaeology but incorporates written records of the time and place for a fuller picture, or uses archaeology to complicate or fill gaps in the records. Historical archaeology is a practice that can be applied to any place and time with historical records, but primarily it refers to archaeology of the Americas post-European colonialism.

These refer to the ways we study the past. Where I start to disagree is when these terms get applied to the past itself.

Historians study history through written texts, so there is often a delineation where history = the presence of written texts, and prehistory = before that. And I have problems with that delineation of time.

For one thing, the connotations of the terms. History, in common use, is important, it’s everything that built the world we live in and led to where we are now. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. While prehistory conjures images of dinosaurs, or cavemen. It implies that the things that happened in it aren’t as important as the things that happened once history proper started. It also feels very, very old—it feels weird to call, say, the Inca empire prehistoric, when the Inca Empire is younger than Oxford University and the first Inca emperor was crowned in Peru after the Norman Invasion of England in 1066—something nobody calls prehistoric.

Because that brings up a more objective issue with splitting time into “history” and “prehistory”: writing was invented at different times in different places, and used to different extents. Writing was first invented in Mesopotamia in the Early Bronze Age, about 5,000 years ago. It was probably independently invented in Egypt shortly afterward, and was independently invented in China 3400 years ago, and in Central America about 2500 years ago. Writing spread across Asia, India, North Africa, Europe, and Mexico/Guatemala; it was not used in North America, South America, southern Africa, Australia, most parts of Polynesia, Micronesia, Australia, or New Zealand at all until European contact. According to the written records definition, this means history starts in very different times in these different places. Not only does this unbalance what we think of as “history” a lot, it ends up discounting or minimizing these people’s own ways of reckoning history, making their history start when Europeans arrived.

This is an incredibly dismissive way to consider whole continents’ worth of people and cultures! It turns them into a “people without history,” and implies that whatever they were doing before Europeans (or Chinese, Indians, or North Africans depending on the region, but mostly Europeans) doesn’t really matter to what happened since. If anything happened at all in that “time before history”; a common perspective of both early colonists and modern pop-history in places like the American West or Australia is that the people there have been living the exact same way for thousands of years, unchanging since the Stone Age. Only upon contact with Europeans did anything change and “history” start. This is hugely dismissive of these people’s autonomy and their past. (You’ll notice it’s a lot of people who suffer from racism who are denied the title of “history”!) It’s also just not true.

I’m an archaeologist who studies the US Southwest/Mexican Northwest region; I focus on Arizona and New Mexico in the 1000s–1400s AD. And one of the things that opened my mind so much in studying the US southwest was just how much things changed from decade to decade and century to century in the past, the same way they did anywhere else in history at this time. There was no written history in this part of the world, but what we do have is very precise tree-ring dates. Using tree rings, we can date when this or that building was built down to the precise year. And because it’s a desert, things preserve well for a long time, so we have lots of ancient tree-ring dates. Because of this, we can see how art styles, architectural styles, settlement patterns, family organization, farming practices, religion, politics, and cultural interactions changed over the past four thousand years. And we can see that they did change, and sometimes they changed slowly and sometimes they changed rapidly. People did things. They had new ideas, they formed new political organizations and adopted new religions, they came together and broke apart, they developed new art styles and new technologies, elite lineages controlled the social order until their power fractured, people moved into new places and adapted their old practices to what they found there, or developed new ones… and because of tree-rings and desert preservation, archaeologists can see it in ways we can’t in cooler and wetter environments. This is history. This is people doing things, shaping the physical and social landscape for the centuries that followed.

And of course, Pueblo and Diné and Apache and O’odham people of the Southwest have their own oral histories that overlap with these archaeological studies. This is true in many, many places that did not traditionally use writing. They can’t be discounted just because they weren’t written down.

So to me, history = writing and prehistory = before writing is a false dichotomy that’s unhelpful at best and racist at worst. To me, history starts when people become socially organized enough that they care about what happened before, what happened where, and why it’s important, and what it means. Every culture has history, whether they wrote it down or not. Studying it may not always be suited to the skillset of historians, but that doesn’t mean it’s not history.

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

I see so many hindutva wadis arguing that caste system is a foreign concept and hinduism only had the varna system. As if the varna system was fair? Also isn't caste derived from the varna system? Like brahmins and Kshatriyas became upper castes, vaishyas became obc and shudra were dalits?

I had the impression that the caste system was the documentation of people who already belonged to the varna system. Do correct me if I'm wrong.

It's a little more complicated than that. Currently, we live under the jaati(or jāti) system broadly speaking. When people talk about the caste system in modern India, it is this system superimposed on the varna system that they are referring to. Functionally, the caste system now is a hybrid of the two systems.

The Varna system and the Jaati System are both systems of social hierarchy.

As everyone is already aware, under the varna system, the society is divided into four categories(i.e. brahmins, kshatriyas, vaishyas and shudras) which are hierarchical in nature and mentioned in the various ancient religious texts. Crucially important to this system is the existence of a fifth category, the untouchables(I assume you're already aware of the practice of untouchability) and the outsiders(often termed as "mlechhas", which is now a derogatory xenophobic{and casteist!} slur coming back into popular use thanks to the resurgence of regressive ideas under hindutva politics). These are important to mention because the marginalization of these people was based on them being an out-group i.e. not part of the varna system. People claim the varnas were mutable based on a handful of examples in said texts but I would like to point out that those examples are said to be exceptions rather than the rule.

The Jaati System would be more familiar to you in terms of lived experience. Under this system, society is divided into socio-ethnic endogamous groups or communities and each of the groups have different socio-economic standing in society. The practice of endogamy(marriage limited to within a social group) is important to this system as there is emphasis on one's birth. This is why people say that intermarriage is the most significant step towards dismantling the entire system, but I digress. Prior to the colonization of India, these groups worked on a purely social basis of privilege and exclusion. Villages and cities were(and still are!) segregated based on these jatis. One's occupation was defined by their birth as long as they lived in their specific society.

I would like to emphasize that this system existed and thrived even before the colonisers ever came knocking on the subcontinent's doors. We can find mentions of the system in the historical accounts of both people of the subcontinent and travellers from outside. A study of people's DNA by some scholars claims that the endogamous groups can be traced back to as far as the Gupta Empire(mid 3rd century to mid 6th century CE).

The assertion that the caste system is a purely colonial fabrication is absurd. People point to the term "caste" as being of foreign origin but the term "jaati" already existed and was in use. "Caste" is just another way of referring to jaatis.

Now on to some legitimacy hidden in the nonsensical claims, in the 1901 census of the subcontinent, the British bureaucracy fit the various jatis under the broad classification of the four varnas. It was not a clean fit, leaving many in an awkward position of having been classified wrongly. This is their fault. Not the construction of the system but rather the wrongful categorisation of it.

Officially, there are over 3,000 castes and 25,000 sub-castes in India. Take these numbers with a grain of salt because there are many unregistered castes and sub-castes to this day fighting their own battles of legal recognition.

The castes do not cleanly map onto the varnas. There are many castes who are in the upper strata of the hierarchy in one region and the lower strata in different regions. The system is incredibly nuanced and complex and our current legal systems have not caught up to the sophistication required to deal with it because of the people in power's adamant insistence of ignoring the system simply because they profit off of the oppression of others.

I don't want to add to the miscategorization but I feel like I should correct you on the fact that broadly speaking shudras are classified more under OBCs. (Please keep in mind that this not a clear category and there can be some castes who are said to be shudra who can be other categories as well.) There's much to be said about that because there's no distinction made between the land owner castes and the landless castes. And no, the creamy layer is not a good marker either.

There are some castes(1,108 of them to be exact) who were listed as scheduled castes(SC) in the Constitution of India for affirmative action. This was done to socially reform the country and help those in the marginalized sections of society to gain social mobility. The hope was to remove caste discrimination. As we know, it wasn't successful because caste discrimination still exists and caste based violence is on the rise again.

The term dalit is a contemporary word for the untouchable castes who were and are subjected to despicable discrimination in society.

The reason that I say that we now function under a hybrid of the two systems is that the superimposition of the varna system over the jaati system has been accepted and in many cases, embraced by the people now. You will find many a "upper caste" people proudly flaunting their Brahmin or kshatriya identities. The varna system is now interlinked with the jaati or the caste system whether we like it or not.

The system is complicated and fucked. We should get rid of it, guys. And with your help, you can make that dream a reality.

-Mod S

#caste system#anti caste#history mention#india#desiblr#hindublr#indian history#indpol#not an incorrect quote#long post#i know but things had to be said#incorrect mahabharata quotes#asks#ask reply#mod replies#i'm tired#mod s is always tired#mod: s

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Culture

There are many definitions of culture and it is used in different ways by different people.

Culture - may be defined as patterns of learned and shared behavior that are cumulative and transmitted across generations.

Patterns

There are systematic and predictable ways of behavior or thinking across members of a culture.

Emerge from adapting, sharing, and storing cultural information.

Can be both similar and different across cultures.

Example: In both Canada and India it is considered polite to bring a small gift to a host’s home. In Canada, it is more common to bring a bottle of wine and for the gift to be opened right away. In India, by contrast, it is more common to bring sweets, and often the gift is set aside to be opened later.

Sharing

Culture is the product of people sharing with one another.

Humans cooperate and share knowledge and skills with other members of their networks.

The ways they share, and the content of what they share, helps make up culture.

Example: Older adults remember a time when long-distance friendships were maintained through letters that arrived in the mail every few months. Contemporary youth culture accomplishes the same goal through the use of instant text messages on smartphones.

Learned

Behaviors, values, norms are acquired through a process known as enculturation that begins with parents and caregivers, because they are the primary influence on young children.

Caregivers teach kids, both directly and by example, about how to behave and how the world works.

They encourage children to be polite, reminding them, for instance, to say “Thank you.” They teach kids how to dress in a way that is appropriate for the culture.

Culture teaches us what behaviors and emotions are appropriate or expected in different situations.

Example: In some societies, it is considered appropriate to conceal anger. Instead of expressing their feelings outright, people purse their lips, furrow their brows, and say little. In other cultures, however, it is appropriate to express anger. In these places, people are more likely to bare their teeth, furrow their brows, point or gesture, and yell (Matsumoto, Yoo, & Chung, 2010).

Learned: Rituals

Members of a culture also engage in rituals which are used to teach people what is important.

Example 1: Young people who are interested in becoming Buddhist monks often have to endure rituals that help them shed feelings of specialness or superiority—feelings that run counter to Buddhist doctrine. To do this, they might be required to wash their teacher’s feet, scrub toilets, or perform other menial tasks.

Example 2: Similarly, many Jewish adolescents go through the process of bar and bat mitzvah. This is a ceremonial reading from scripture that requires the study of Hebrew and, when completed, signals that the youth is ready for full participation in public worship.

These examples help to illustrate the concept of enculturation.

Cumulative

Cultural knowledge is information that is “stored” and then the learning grows across generations.

We understand more about the world today than we did 200 years ago, but that doesn’t mean the culture from long ago has been erased.

Example: Members of the Haida culture, a First Nations people in British Columbia, Canada are able to profit from both ancient and modern experiences. They might employ traditional fishing practices and wisdom stories while also using modern technologies and services.

Transmission

Passing of new knowledge and traditions of culture from one generation to the next, as well as across other cultures is cultural transmission.

In everyday life, the most common way cultural norms are transmitted is within each individuals’ home life.

Each family has its own, distinct culture under the big picture of each given society and/or nation.

With every family, there are traditions that are kept alive.

The way each family acts and communicates with others and an overall view of life are passed down.

Parents teach their kids every day how to behave and act by their actions alone.

Outside of the family, culture can be transmitted at various social institutions like places of worship, schools, even shopping centers are places where enculturation happens and is transmitted.

Understanding culture as a learned pattern of thoughts and behaviors is interesting for several reasons:

It highlights the ways groups can come into conflict with one another. Members of different cultures simply learn different ways of behaving. Teenagers today interact with technologies, like a smartphone, using a different set of rules than people who are in their 40s, 50s, or 60s. Older adults might find texting in the middle of a face-to-face conversation rude while younger people often do not. These differences can sometimes become politicized and a source of tension between groups. One example of this is Muslim women who wear a hijab, or headscarf. Non-Muslims do not follow this practice, so occasional misunderstandings arise about the appropriateness of the tradition.

Understanding that culture is learned is important because it means that people can adopt an appreciation of patterns of behavior that are different than their own.

Understanding that culture is learned can be helpful in developing self-awareness. For instance, people from the United States might not even be aware of the fact that their attitudes about public nudity are influenced by their cultural learning. While women often go topless on beaches in Europe and women living a traditional tribal existence in places like the South Pacific also go topless, it is illegal for women in some of the United States to do so. These cultural norms for modesty that are reflected in government laws and policies also enter the discourse on social issues such as the appropriateness of breastfeeding in public. Understanding that your preferences are, in many cases, the products of cultural learning might empower you to revise them if doing so will lead to a better life for you or others.

Humans use culture to adapt and transform the world they live in and you should think of the word culture as a conceptual tool rather than as a uniform, static definition.

Culture changes through interactions with individuals, media, and technology, just to name a few.

Culture generally changes for one of 2 reasons:

Selective transmission or

to meet changing needs.

This means that when a village or culture is met with new challenges, for example, a loss of a food source, they must change the way they live.

It could also include forced relocation from ancestral domains due to external or internal forces.

Example: In the United States, tens of thousands Native Americans were forced to migrate from their ancestral lands to reservations established by the United States government so it could acquire lands rich with natural resources. The forced migration resulted in death, disease and many cultural changes for the Native Americans as they adjusted to new ecology and way of life.

Source ⚜ More: On Psychology ⚜ Writing Notes & References

#writing notes#culture#psychology#writeblr#writing reference#dark academia#spilled ink#literature#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#poetry#poets on tumblr#creative writing#writing resources

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wisdom of Ancient Indian Education: The 8 Limbs of Yoga and Beyond

Since times before the antiquities, Indian education system has been very robust. One of the core objective was to shape the individual and the society with highest virtues. How an individual should be is mentioned in various scriptures like Ved, Puran, Upanishad and others. In present times, one may consider these texts as purely religious scriptures. It is a common belief of most of the people,…

View On WordPress

#Ancient Civilizations#ancient hindu scriptures#Ancient India#ancient indian science#Ancient Knowledge#Ancient Knowledge System#Ancient texts#cultural heritage#Culture#Exploring Hindu Puranas#Hindu civilization#Hindu Scriptural Insights#Hindusim#India&039;s heritage#Indian education system#Indian Religious Texts#Lost Indian Knowledge#qualityoflife#Rediscovering Indian culture#Sacred Hindu Texts#Spiritual Wisdom#Yam&Niyam#yoga#yogaphilosophy

0 notes

Text

EXTERNAL INFLUENCES IN DUNGEON MESHI: INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

(SPOILERS FOR DUNGEON MESHI BELOW)

We know that Ryoko Kui spent considerable time at the beginning of working on Dungeon Meshi doing research and planning the series. Kui constantly references real world culture, history and mythology, but she also occasionally references real-world philosophy.

The story of Dungeon Meshi is full of philosophical questions about the joy and privilege of being alive, the inevitability of death and loss, the importance of taking care of yourself and your loved ones, and the purpose and true nature of desire. Kui explores these issues through the plot, the characters, and even the fundamental building blocks that make up her fictional fantasy world. Though it’s impossible to say without Kui making a statement on the issue, I believe Dungeon Meshi reflects many elements of ancient Indian philosophy and religion.

It’s possible that Kui just finds these ideas interesting to write about, but doesn’t have any personal affiliation with either religion, however I would not be at all surprised if I learned that Kui is a Buddhist, or has personal experience with Buddhism, since it’s one of the major religions in Japan.

I could write many essays trying to explain these extremely complex concepts, and I know that my understanding of them is imperfect, but I’ll do my best to explain them in as simple a way as possible to illustrate how these ideas may have influenced Kui’s work.

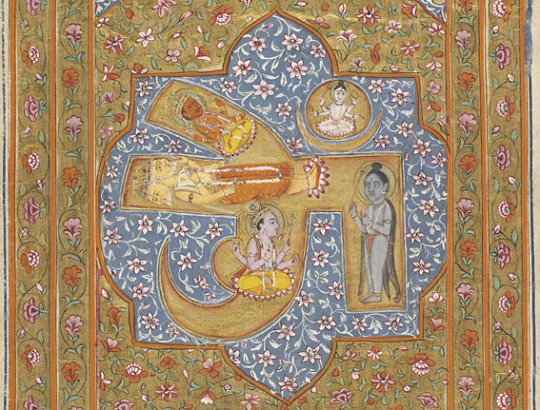

HINDUISM

Hinduism is the third-largest religion in the world and originates in India. The term Hinduism is a huge umbrella that encompasses many diverse systems of thought, but they have some shared theological elements, and share many ancient texts and myths.

According to Classical Hindu belief, there are four core goals in human life, and they are the pursuit of dharma, artha, kama, and moksha.

Dharma is the natural order of the universe, and also one’s obligation to carry out their part in it. It is the pursuit and execution of one’s inherent nature and true calling, playing one’s role in the cosmic order.

Artha is the resources needed for an individual’s material well-being. A central premise of Hindu philosophy is that every person should live a joyous, pleasurable and fulfilling life, where every person's needs are acknowledged and fulfilled. A person's needs can only be fulfilled when sufficient means are available.

Kama is sensory, emotional, and aesthetic pleasure. Often misinterpreted to only mean “sexual desire”, kama is any kind of enjoyment derived from one or more of the five senses, including things like having sex, eating, listening to music, or admiring a painting. The pursuit of kama is considered an essential part of healthy human life, as long as it is in balance with the pursuit of the three other goals.

Moksha is peace, release, nirvana, and ultimate enlightenment. Moksha is freedom from ignorance through self-knowledge and true understanding of the universe, and the end of the inevitable suffering caused by the struggle of being alive. When one has reached true enlightenment, has nothing more to learn or understand about the universe, and has let go of all earthly desires, they have attained moksha, and they will not be reborn again. In Hinduism’s ancient texts, moksha is seen as achievable through the same techniques used to practice dharma, for example self-reflection and self-control. Moksha is sometimes described as self-discipline that is so perfect that it becomes unconscious behavior.

The core conflict of Hinduism is the eternal struggle between the material and immaterial world. It is often said that all of the material world is “an illusion,” and what this means is that all good and bad things will inevitably end, because the material world is finite. On the one hand, this is sad, because everything good in life will one day cease to exist, but on the other hand, this is reassuring, because all of the bad things will eventually end as well, and if one can accept this, they will be at peace.

The central debate of Hinduism is, which is more important: Satisfying your needs as a living thing, having a good life as a productive member of society, serving yourself, your family, and the world by participating in it the way nature intended? Or is it rejecting desire and attachment, discovering the true nature of existence, realizing the impermanence of material things, and that one can only escape the suffering that comes from the struggle of life by accepting that death and loss are inevitable?

There is no set answer to this question, and most believers of Hinduism tend to strike a balance between the two extremes simply because that’s what happens when a person leads a normal, average life, however there are also those who believe that pursuing extremes will lead to ultimate enlightenment and final release as well.

BUDDHISM

Buddhism is an Indian religion and philosophical tradition that originated in the 5th century BCE, based on teachings attributed to religious teacher the Buddha. It is the world's fourth-largest religion and though it began in India, it has spread throughout all of Asia and has played a major role in Asian culture and spirituality, eventually spreading to the West beginning in the 20th century.

Buddhism is partially derived from the same worldview and philosophical belief system as Hinduism, and the main difference is that the Buddha taught that there is a “middle way” that all people should strive to attain, and that the excesses of asceticism (total self-denial) or hedonism (total self-indulgence) practiced by some Hindus could not lead a person to moksha/enlightenment/release from suffering.

Buddhism teaches that the primary source of suffering in life is caused by misperception or ignorance of two truths; nothing is permanent, and there is no individual self.

Buddhists believe that dukkha (suffering) is an innate characteristic of life, and it is manifested in trying to “have” or “keep” things, due to fear of loss and suffering. Dukkha is caused by desire. Dukkha can be ended by ceasing to feel desire through achieving enlightenment and understanding that everything is a temporary illusion.

There are many, many other differences between Hinduism and Buddhism, but these elements are the ones that I think are most relevant to Kui’s work.

Extreme hedonism involves seeking sensual pleasure without any limits. This could just be indulging in what people would consider “normal” pleasures, like food, sex, drugs and the arts, but it can also involve doing things which are considered socially repugnant, either literally or by taking part in symbolic rituals that represent these acts. Some examples are holding religious meetings in forbidden places, consuming forbidden substances (including human flesh), using human bones as tools, or engaging in sex with partners who are considered socially unacceptable (unclean, wrong gender, too young, too old, related to the practitioner). Again, these acts may be done literally or symbolically.

Extreme ascetic practices involve anything that torments the physical body, and some examples are meditation without breathing, the total suppression of bodily movement, refusing to lay down, tearing out the hair, going naked, wearing rough and painful clothing, laying on a mat of thorns, or starving oneself.

HOW THIS CONNECTS TO DUNGEON MESHI

Kui’s most emphasized message in Dungeon Meshi is that being alive is a fleeting, temporary experience that once lost, cannot truly be regained, and is therefore precious in its rarity. Kui also tells us that to be alive means to desire things, that one cannot exist without the other, that desire is essential for life. This reflects the four core goals of human life in Hinduism and Buddhism, but also could be a criticism of some aspects of these philosophies.

I think Kui’s story shows the logical functionality of the four core goals: only characters who properly take care of themselves, and who accept the risk of suffering are able to thrive and experience joy. I think Kui agrees with the Buddhist stance that neither extreme hedonism nor extreme self-denial can lead to enlightenment and ultimate bliss… But I also think that Kui may be saying that ultimate bliss is an illusion, and that the greatest bliss can only be found while a person is still alive, experiencing both loss and desire as a living being.

Kui tells us living things should strive to remain alive, no matter how difficult living may be sometimes, because taking part in life is inherently valuable. All joy and happiness comes from being alive and sharing that precious, limited life with the people around you, and knowing that happiness is finite and must be savored.

Dungeon Meshi tells us souls exist, but never tells us where they go or what happens after death. I think this is very intentional, because Kui doesn’t want readers to think that the characters can just give up and be happy in their next life, or in an afterlife.

There is resurrection in Dungeon Meshi, but thematically there are really no true “second chances.” Although in-universe society views revival as an unambiguous good and moral imperative, Kui repeatedly reminds us of its unnatural and dangerous nature. Although reviving Falin is a central goal of the story, it is only when Laios and Marcille are able to let go of her that the revival finally works… And after the manga’s ending, Kui tells us Falin leaves Laios and Marcille behind to travel the world alone, which essentially makes her dead to them anyway, since she is absent from their lives.

At the same time, Kui tells us that trying to prevent death, or avoid all suffering and loss is a foolish quest that will never end in happiness, because loss and suffering are inevitable and must someday be endured as part of the cycle of life. Happiness cannot exist without suffering, just like the joy of eating requires the existence of hunger, and even starvation.

Kui equates eating with desire itself, using it as a metaphor to describe anything a living creature might want, Kui also views the literal act of eating as the deepest, most fundamental desire of a living thing, the desire that all other desires are built on top of. If a living thing doesn’t eat, it will not have the energy necessary to engage with any other part of life. Toshiro, Mithrun, and Kabru are all examples of this in the story: They don’t take care of themselves and they actively avoid eating, and as a result they suffer from weakness, and struggle to realize their other desires.

Kui suggests that the key difference between being alive or dead is whether or not someone experiences desire. If you are alive, even if you feel empty and cannot identify your desires like Mithrun, you still have desires because you would be dead without them. The living body desires to breathe, to eat, to sleep, even if a person has become numb, or rejected those desires either to punish themselves, or out of a lack of self-love.

Sometimes, we have to do things which are painful and unpleasant, in order to enjoy the good things that make us happy. I believe Kui is telling us that giving up, falling into despair, and refusing to participate in life is not a viable solution either.

The demon only learns to experience desire by entering into and existing in the material, finite world. This experience intoxicates the demon, and it becomes addicted to feeling both the suffering of desire, and the satisfaction of having it fulfilled. This unnatural situation is what endangers the Dungeon Meshi world, and it’s only by purging the demon of this ability to desire that the world can be saved. The demon is like a corrupted Buddha that must give up its desires in order to return to the peaceful existence it had before it was corrupted.

The demon curses Laios to never achieve his greatest desires at the end of the manga, which manifests in several ways, such as losing his monstrous form, Falin choosing to leave after she’s revived, and being unable to get close to monsters because they are afraid of him. In some ways you could compare Laios to a Bodhisattva, a person who tries to aid others in finding nirvana/moksha, even if it prolongs their own suffering and prevents them from finding personal release. Laios gives the demon peace, but Laios himself will never be able to satisfy his desires, and must eventually come to accept his loss and move on with his life.

(This is an excerpt from Chapter 3 of my Real World Cultural and Linguistic influences in Dungeon Meshi essay.)

#dungeon meshi#delicious in dungeon#the winged lion#dungeon meshi spoilers#laios touden#mithrun of the house of kerensil#analysis#The Essay#After all the conversation about Mithrun I felt it was really important to drop this excerpt today

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Flags inspiration theory I have found, compiled

Note: some links are used multiple times, from sources with multiple theories. I pretty much linked everything I could find.

Albatross

Charles Baudelaire: mentioned here, here, here, here, and here. He wrote “L’albatros,” had imagery of guts in his writing, was a party person, wrote about alcohol, was a poet and major influence on Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, and travelled to India (kukri knives are Nepalese in origin, but they are used elsewhere, including by the modern Indian Army. There is a very tangential possible connection).

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: mentioned here, and someone I know IRL is convinced of it. In The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the albatross is a good omen for a ship (a boon to transit, + could connect to evading the helicopter and the time Albatross forced Chuuya to swim home) who is brutally killed, haunting the narrative.

Jules Verne: mentioned here. Albatross' management of vehicles goes with Around the World in Eighty Days, and the quicksand ability, if his, could reference Journey to the Center of the Earth. Verne being in 55 Minutes makes this seem less likely, though not out of the question given the unlikelihood of Albatross' legal name or author basis being specified.

Doc

Michael Crichton: mentioned here, here, here, and here. He wrote Jurassic Park, which includes dinosaurs (possibly connecting to his ability), the disastrous consequences of dubiously ethical genetic experiments (connecting to Stormbringer overall), and general themes of irresponsibly playing G-d. He had an M.D. from Harvard, making him, like Doc, a real doctor who studied in North America. Doc's religious views tying into the archangel Michael's significance in apocalyptic religious texts is possible if tangential.

Edward Elmer Smith/E.E. "Doc" Smith: mentioned here. A sci-fi author known as Doc who was also a chemist. (He was described as blond, athletic, and gallant by Heinlein, which could be an intentional irony if Doc is based on him).

Iceman

Eugene O’Neill: mentioned here, here, and here. He wrote The Iceman Cometh, a play with a lot of parallels to the Flags and Stormbringer, and looked like Iceman.

Richard Kuklinski: mentioned here, here, and here. A convicted murderer known as the Iceman who claimed to have been a mafia hitman and to have killed 100-200 people (actually killed at least 5 but probably not more than 15). There is a book about him called The Ice Man: Confessions of a Mafia Contract Killer (though he didn't write it).

Aoyama Jirō: mentioned here. An art critic known for keen insight and a member of IRL Nakahara Chuuya's friend group.

Kawakami Tetsutaro: mentioned here. He introduced IRL Nakahara Chuuya to Saburō Moroi, and they were close friends until Nakahara's death.

Lippmann

Walter Lippmann: mentioned here, here, here, here, here, here, and probably elsewhere. Named Lippmann, he wrote Public Opinion, and his career in journalism, propaganda and negotiation work, and close ties to people in power fit with Lippmann being the face of the Mafia. The way he frequently held back until he got to a controversial issue which he decided he had to speak out about at the end of his career and him authoring a book which opens by talking about delays in information transfer could both correspond to an ability which will (allegedly) go off when he's killed and show the world the perpetrator.

Hasegawa Yasuko: mentioned here. She was an actress who IRL Nakahara Chuuya was once in love with and remained friends with.

Piano Man

Moroi Saburō: mentioned here and here. He brought together a music group which turned into a friend group which included IRL Nakahara Chuuya and adapted some of Nakahara's poems to music, as well as writing a lot of other music for the piano and other instruments.

D.H. Lawrence: mentioned here. He wrote "Piano," a famous poem where listening to a piano brings back memories of a lost childhood.

Billy Joel: mentioned here, here (sort of?), and in at least one other post I can't relocate, usually or always as a joke. He wrote and performed the song "Piano Man," which is about people hanging out at a bar.

#I bet there are more theories and I'll reblog this with them if I find them#bsd flags#bsd the flags#bsd albatross#bsd doc#bsd iceman#bsd lippmann#bsd pianoman#bsd theories#long post#I could be wrong about many details here because I've only read things by half these writers#counting Billy Joel#and am not an expert on any of them#Chuuya is not included in this post because he has a confirmed inspiration#I'm sure someone has an alt author inspiration theory for him#(like the theory that Sigma is the actual Dostoevsky)#but I'm also sure it's wrong#The Flags are ordered alphabetically and the theories are ordered by how likely I think they are#In some cases multiple theories could be correct#like if Piano Man led the group because of Saburō but he was also inspired by someone who wrote about counterfeiting or guillotines

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nearly ten days after the Pahalgam attack, watching the various responses to said attack...part of me is shocked, and another confused. Yet another thinks that something like this is inevitable.

Too many people reacted to what is undoubtedly a terrorist attack by channelling their rage and grief into persecuting innocent people because the terrorists asked those they killed to recite the kalma, undoubtedly being Islamic in their origin.

Yes, they were Muslim. Does that mean there should be violence against innocent Kashmiri students because 'Hindu khatre mein hain"? No. Do you know why? Because a large part of why such Islamic organisations sway local sympathies towards them is by the catchphrase "Islamiyat khatre mein hain." Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Why wouldn't it? We've heard an alternate religion version of it over TV channels and so-called "news" and "leaders of the free world" screaming Hindu khatre mein hain, khatre mein hain, after all.

So many of us believe it, too.

Why, some of us may ask, shouldn't we believe so? We are Hindus, and we aren't safe even in our own land, our own country. Perhaps we should look deeper into the 'why' of it. So much of violence against us is by ourselves, for daring to be different. Lynching, beating, far more for far too less. So what if someone eats meat? They aren't stopping you from living your life. Why should you put an end to theirs?

But, then, as people who hold power today ask, what about the invaders who invaded India 1000 years ago, 1200 years ago? People whose descendants divide the country today, covet its assets for themselves? Including Kashmir, the jewel of India?

To that is my answer: If that is what you believe, then we should all leave this land. Most of us, at least. None of us are indigenous to the land we live in, except perhaps the tribes in Sentinel island. Other than that, all of us, except for the populations that are tribal/adivasis, probably migrated from somewhere else, simply some time longer ago than 1200 years.

But then, argue some, what about religious texts that speak to tens and thousands of years of ancestry? The Mahabharata, the Itihasas, the Puranas?

In that case, well, might I remind you that Sanskrit is not the single sole classical language that speaks of thousands of years of history? There is the matter of at least one other culture and language that exists alongside. The Sangam literature too speaks of thousands of years. Three whole Sangams, might I mention.

Almost every single ancient culture claims grandiose descent. We do not know how much credence should be given to any of these claims, but, if we are giving credence to one claim, why leave the others behind? Give equal credence, why don't you?

Coming back to 1200 years of "slave mentality" and "coveting territory" I will be paraphrasing words written nearly a 100 years ago by a man who identified as Kashmiri, if not perhaps Hindu, though he rather did admire the title Pandit. He very famously preferred to be known for his scientific temper, possibly a reason why today's rulers loathe this man.

He said, and I paraphrase, that those rulers are not considered foreign rule because there was marital intermixing of races and blood relations, because whatever money was made was spent inside India, because it did not go to another country (Ghori and Ghazni aside, the temple was rebuilt within 50 years, though the 'collective trauma' was first heard of in the British parliament sometime in the 19th century)

People have a beautiful tendency to syncretise, to meld with each other, to form cultures of harmony. Look at each state of India, the cultural plurality (that a homogenous overarching 'desi' identity cannot and will not encapsulate, but this discussion is for another post) especially Kashmir. There is amazing cultural syncretism in their literature, art, architecture, even notions of Kashmiri identity.

There is a unity in diversity. When is this threatened? When a section of the population felt trampled on by the 'high-handed' handling of things (in their own words) by the 'elected' powers (there is widespread allegation of electoral rigging over the years in Kashmir)

In the '80's and '90's it comes in the form of 'Islamiyat khatre mein hain' because at that point, they felt they weren't given the opportunities they should by the Indian Government. There was liberal support from external organisations, and insurgency flourished. The Kashmiri Hindu exodus takes place in these decades, and there is an element of "Hindu khatre mein hain" which is fanned by the government. The following two to three passages are from a report by Human Rights Watch in 1992, during said exodus.

A number of Hindu refugees from Kashmir have subsequently denounced the government for encouraging them to leave under false pretenses. In a letter to the editor of Alsafa in October 1990, some 20 Pandit refugees alleged that: There can be no dispute about the fact the Kashmiri Pandit community was made a scapegoat by Jagmohan, some self-styled leaders of our community and other vested interests ... [T]he plan was to make the K.P.'s [Kashmiri Pandits] migrate from the valley so that the mass uprising against occupation forces could be painted as a communal flare up.... Some self-styled leaders of the Pandit community... begged the Pandits to migrate from the valley. We were told that our migration was very vital for preserving and protecting 'Dharm' [religious integrity] and the unity and the integrity of India. We were told that our migration would pave the way for realizing the dream of Akhand Bharat [undivided India].... We were made to believe that our migration was very important for Hinduism and for keeping India together.... We were fooled and we were more than willing to become fools.205

At the same time, it is clear that many Hindus were made the targets of threats and acts of violence by militant organizations and that this wave of killing and harassment motivated many to leave the valley. Such threats and violence constitute violations of the laws of war, and Asia Watch was able to document many specific cases. • On September 20, 1989, O.N. Sharma, a 47-year-old travel agent from Srinagar found a letter written in Urdu in his mailbox, signed by the JKLF. Sharma told Asia Watch that the letter was addressed to him by name and it referred to him as an "Indian dog." The letter told Sharma to leave the valley by September 27, or he and his family would be killed. At the time, Sharma was living with his wife, two children and his mother.

Again paraphrasing words written very soon after Indian independence. "Minority communities should feel secure in their rights as Indian citizens and that is the part of the majority to ensure. Communalism in all forms is the greatest danger to Indian sovereignty as a whole."

Even today, Kashmiri rights are not ensured. The Indian Army and militant/terrorist bodies have both behaved horribly with Kashmiri women over the years with multiple documented cases of rape still pending action (Human Rights Watch has multiple reports on such cases) and so...such boiling over feels inevitable, on some counts.

The Kashmiri people deserve a voice in their own fate.

@scribblesbyavi bhaiyya, you may like to read this.

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

can I ask about what the drama around "palace of illusions" is about and why it's bad?

Hey! Sure thing. Lemme list my problems with the book :-

1) The author presents Karna as some tragic hero compelled to be in the company of Duryodhana who clearly committed multiple murder attempts, went on to sexually harrass his sister-in-law and troubled another woman during the Ghosha yatra. Karna was NOT an outcaste. He was a Suta— meaning one with a Brahmin mother and a Kshatriya father. Adhiratha, Karna's adoptive father, was a wealthy man as he was Bhishma's charioteer. Keep in mind that charioteers used to play important roles in warriors' lives - as advisers, close friends and well-wishers. Krishna was the charioteer of Arjuna. Karna had all the opportunities the Pandavas didnt. He had parents who loved him, while the Pandavas were left halfly orphaned with the death of Pandu and Madri. Veda Vyasa describes Karna as "the trunk of the tree of adharma".

2) The Karna Draupadi ship is bullshit because Karna called the latter a whore during the disrobing sequence as well as presented the idea of "there should be no clothes on servants." Yes, Karna was the one who suggested her public sexual assault. She had blood stains on her garment and was dragged into the court of nefarious men by her hair. People who blame her for the assault inflicted on her are sick and need serious psychological help. You cannot defend attempted rape as one with working braincells.

3) So, shipping a victim with her abuser is not fun y'all. This is not some mentally unstable wattpad dark romance. It's itihāsa. The true history of Bhāratavarsha. Let's draw the line. She was an ekavastraa (meaning a woman in a single cloth, as she was menstruating) during the attempt at disrobing, and the man who called for it shouldn't be hailed. Karna also lied to Parashurama of his caste due to which he got cursed, had an unhealthy obsession with Arjuna and because he wanted to kill him for competition, Drona did not provide him with the knowledge of celestial weapons.

4) It is an ignominy against Lady Draupadi to ship her with anyone apart from her husbands because clearly, the Mahabharata says that she's Indra's wife Shachi while the Pandavas are the cursed five Indras of different kalpas. It is . . . not nice to ship one's wife with another man. It is creepy. Draupadi is one of the panchakanya, one of the five pious women whose names if chanted with sincerity wash off one's sins. She expresses her pride over her husbands multiple times in the text because all of them cherish her to no end. Yudhishthira does not hesitate on the fact that Draupadi is the five brothers' fortune, calls her ‘Kalyani’. Bhima kills Keechaka for her, threatening the revealing of their identities. Arjuna becomes Brihannala and spends most of the time near her during the incognito. In the book, however, the Pandavas do not give a damn about her. Yikes.

5) The book says that Draupadi faced prejudice because of her dark skin. I call bullshit again because Madreya Nakula, Partha Arjuna, Krishnatmika Devi Rukmini according to the Harivamsha, Devi Shri Jambavati (who is said to have a blue lotus like complexion), and lastly Shri Rama and Shri Krishna themselves are dark according to our scriptures. And, none of them faced discrimination because of it. Kanha is in fact called "Bhuvansundar" - the most beautiful one on the earth while Draupadi herself is hailed as one of the most beautiful women canonically.

6) Draupadi was never attracted to Karna. Neither did she pine for him, as the author portrays. Sheesh. Please please, we do whatever with human characters. But with divine ones, you have to be careful with the message you get across. This book is saying that ancient india was casteist and colorist, literally the times when the son of a fisherwoman, Veda Vyasa became a Brahmin and the said fisherwoman went on to become a queen mother of one of the most influential dynasties back then. Krishna was raised a cowherd, though a prince. He went on to become the most erudite diplomat and established Dvaraka, which was en engineering marvel as it was constructed on reclaimed land.

7) According to the author . . . Draupadi felt something more than just friendship for Krishna too. Heavens, I can't do this. Let's normalise a man and a woman being just friends now, shall we? Krishna is Mahavishnu, he's not supposed to invoke romantic feelings in Draupadi who is Shachi, Indra's wife. Indra and Upendra (Vishnu) are brothers, since Vāmanadeva was born of Mata Aditi's womb, who is Indra's mother and of all the Adityas' too.

#draupadi#Mahabharata#pandavas#karna#the palace of illusions#chitra banerjee divakaruni#reblogging my own post with edits because i missed multiple points in the last version#do not sympathise with abusers ffs

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

"O Indra! Give us the highest of riches, the skill and knowledge for action. Give us well-being and the vigor of vitality to our limbs. Protect us against injury. May we become sweet of speech and may our days be days that are full of light." ~Rigveda 2.22.6

Lord Indra ॐ Talon Abraxas Lord Indra in Buddhism: Unveiling the Divine Role in Buddhist Cosmology Historical Context of Indra in Buddhism Origins and Evolution of Indra Lord Indra Lord, originally a prominent Vedic deity, was assimilated into Buddhist lore during the religion's formative years. This period was characterized by the fusion of various religious and cultural elements in ancient India, leading to a syncretic representation of Indra in Buddhist texts. Influence Across Asia As Buddhism expanded across Asia, Indra's depiction varied, adapting local influences and gaining distinct attributes in regions like Tibet, China, Japan, and Southeast Asia.