#Policing in america

Text

Police State - Ten Secrets The Police Don’t Want You To Know! “How To Survive Police Encounters!”

click the title link to Download FREE FROM THE BLACK TRUEBRARY

Police State - Ten Secrets The Police Don’t Want You To Know! “How To Survive Police Encounters!”

click the title link to Download FREE FROM THE BLACK TRUEBRARY

Former Decorated Police Officer, Vietnam Veteran, and current Civil Rights Instructor, Terry Ingram, reveals Ten secrets the Police don't want you to know. Terry's 40 years of experience on both sides of the fence give him a singularly unique perspective on "How to Survive Police Encounters" in this day and age. A must read for anyone trying to cope in the current Police State and more.

Finally, the truth is revealed about what really goes on inside the mind of a Police Officer. Forget about the main stream mottos like "serve and protect"; "community service"; and other boilerplate mantras spoon fed to the public by Law Enforcement Public Relation Pundits.

Take it from a 12 year Decorated Police veteran in Robbery Homicide, Vice, Intelligence, Narcotics, K-9 and routine Uniformed Patrol. The Policeman is definitely no longer your friend. He is your adversary. Just like the salesman who hones his skills to close the deal, the Police Officer is a very practiced and dangerous antagonist to anyone who stands in the way of the Police State.

Many Police Officers initially go into their chosen field with good and decent intentions. However, after intense paramilitary indoctrination they are soon turned to the dark side (Away from the Constitution and Bill of Rights and toward the Police State). This is not an overstatement; those that won’t be turned find themselves back on the street. Most Police Departments have a 1 year probationary period where the Officer is not protected by a “civil service contract”. During that year, even the best of them are broken or discarded.

“The New Breed”, that’s what they called us when I attended the very “first Police Academy” in South Florida, back in early 1974. The idea was to militarize the New Breed by creating a “Boot Camp” of sorts. Believe me when I say that they have come a long way down the slippery slope since my day. I pass by the Police Academy in Davie, Florida rather frequently and see them [Police Inductees I call them] marching, standing at attention, assuming the prone position and giving the instructor 50 pushups on demand. It sickens me.

This book is a must read for anyone confronting any type of “Police Encounter” in today’s Police State. It is imperative that you learn your rights, because that’s the only way you’re going to stop them. Whether in your car, home or out in the community, they are always there watching and waiting for you to make the slightest mistake. They are the sharks in the water and you are the bloody bait.

We have indeed entered a new regime…

youtube

click the title link to Download FREE FROM THE BLACK TRUEBRARY

#Police State - Ten Secrets The Police Don’t Want You To Know! “How To Survive Police Encounters!”#Police Violence#Black Lives Matter#Policing in america#police killing people#THE BLACK TRUEBRARY#Youtube

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#abolish the police#police brutality#tweet#rip twitter#anarchy#twitter post#anti capitalism#leftism#communism#socialism#fuck cops#fuck the police#police violence#homelessness#homeless#poverty#financial assistance#support#financial aid#usa news#usa politics#united states#geopolitics#united states of america#americans#america

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

guys please consider policeman gojo—he sits in a parking lot he knows you'll drive by when he's off duty/on break and just waits until your car drives past him. he recognizes it immediately—and then the sirens go off, and a cop car is tailing you, and you sigh and pull over as you think to yourself here we go again. it's the most annoyingly irritating white-haired man to EVER exist strolling up to your car, grinning at you as you say "can i help you officer?"

and he sighs dramatically and says, "i"m afraid i'm gonna have to charge you with theft," as you roll your eyes.

you just indulge him as you dryly ask, "and what did i steal?"

"well," he starts, just barely containing his giggles, "you've stolen my heart."

you look at him wholly unimpressed—but then the corners of your lips tug into a smile against your will before you shake your head and snort, muttering a quiet, "come here, you idiot," before letting him bend down and kiss you sweetly.

he grins and winks as he says, "next time i'll have'ta handcuff you, y'know," before he pecks your lips one more time and murmurs, "see you at home."

it'll happen again tomorrow. and the day after that. and the next day after that—but you just keep stealing his heart, and he just keeps letting you get away with it.

#usually i hate the police bc i live in america so obviously they want me dead#but gojo is the exception#as always#shorts.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Black couple living in Dallas say their 2-week-old daughter was taken from them because they decided to have a home birth with a midwife.

Home-births and midwifery services are increasingly sought out by Black pregnant people and families over traditional hospital settings amid a mounting maternal mortality crisis exacerbated by systemic medical racism. Black pregnant people are three to four times more likely than white pregnant people to die from pregnancy-related causes, per the CDC.

When Black pregnant people and families can’t feel safe seeking pregnancy and birth-related services from the hospital, and can’t feel safe choosing home births and home care options that draw police attention.

#horrific#stop kidnapping Black kids#Texas is the worst#CPS#black twitter#america was never great#twitter#police state#protect black children

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

#Blm#crime#news#police brutality#police state#true crime#usa#america#cops#united states#black lives matter#politics#republicans#democrats#sad

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosalie Tialavea, Leafa's oldest sister, recounted how the police entered the apartment with their guns drawn, without asking any questions about Leafa's age or who lived there, despite Leafa's mother being present and several minors, including infants, being in the home.

"They told us to get in the room and get out of their way," Tialavea recalled. "I asked them if I could talk to my youngest because we all know how she is, and how she is not a social person. I asked them and they said no."

Tialavea described Leafa as an "overthinker" who sometimes had emotional breakdowns. On the night of the incident, she was sitting on the balcony with a blanket over her head. The family believed they could talk her out of holding the knife and tried to intervene, but the police insisted they stay out of the way.

According to the family, Leafa's English was not very strong, and when the police ordered her to drop the knife she was holding downward by her side, they said it didn't take much for the officers to shoot.

"She made one movement, a little tiny movement," Tialavea said. "They shot her three times... They saw her go down on the second shot and they had to fire another one."

Easter Leafa was a 16 year old girl who was supposed to start the school year before the police took that from her.

587 notes

·

View notes

Text

tw: homophobic slurs

Obviously, I do not agree with the usage of homophobic slurs. It’s not cool. It doesn’t matter if it’s being directed at cops or Republicans or any group that I dislike. If someone uses slurs against an enemy of theirs, then they have probably used it against the group that it’s meant to disparage.

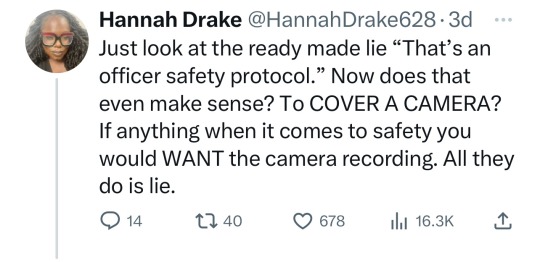

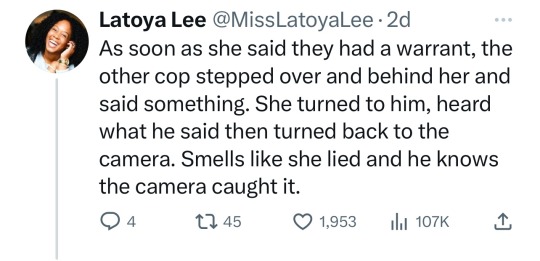

I just wanted to post this because of A) how perfectly she handled the police - you don’t necessarily have to curse, but never ever ever let them enter your home without a warrant B) to show how the police routinely lie about having search warrants + doing sketchy shit for their alleged “safety,” and C) because I truly believe this was a white person, and that + being recorded are literally thee only reasons they stayed polite and didn’t goon squad rush her ass.

White people generally get away with being crass and disrespectful to police officers. Sandra Bland, on the other hand, got murdered for being “too uppity.”

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

On May 4, 1970, during an anti-war protest opposing the war in Vietnam, sprung from the expansion into Cambodia, four students were killed, and nine were harmed by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University campus. The students were unarmed. Not one of the shooters went to jail. A national moment that sparked even more anti-war protests and general condemnation for the american state.

Anti-war protests and support have historically been villanised. Under the Vietnam War, opposers were called commies. Under the 'war against terror', opposers were called terrorist sympathisers. When the US went into Iraq, opposers were called traitors. All were known as pushing anti-America sentiment—being unpatriotic—just as we hear being slung around today: opposers are terrorist-supporters, antisemitic and nazis. Creating rhetoric demonising demonstrators is favourable for the state's image and affairs, "they are the mad ones, so PLEASE stop criticising our war, our invasion, and our genocide". Patterned hindsight is why we must not forget that this is a historical tactic, which will only work if we forget. Hold them accountable for this genocide; in the future, they will try to soften their current actions out of embarrassment. It won't work.

The around 300 Kent State University students' demands lay as an echo over those we hear yelled from campuses all over the US this week. Student protests and organising have always been important measures in combating government actions and to all who are attending these protests: the world is seeing you; your demands are echoing through nation borders. I am proud of my fellow students and have, myself, been inspired to look into actions I can partake in at my own university. Thank you. Be safe. Free Palestine.

#kent state university#kent state#police brutality#campus protests#university protests#vietnam war#free palestine#palestine#politics#usa#fuck america#gaza strip

416 notes

·

View notes

Text

Late one night several years ago, I got out of my car on a dark midtown Atlanta street when a man standing fifteen feet away pointed a gun at me and threatened to “blow my head off.” I’d been parked outside my new apartment in a racially mixed but mostly white neighborhood that I didn’t consider a high-crime area. As the man repeated the threat, I suppressed my first instinct to run and fearfully raised my hands in helpless submission. I begged the man not to shoot me, repeating over and over again, “It’s all right, it’s okay.”

The man was a uniformed police officer. As a criminal defense attorney, I knew that my survival required careful, strategic thinking. I had to stay calm. I’d just returned home from my law office in a car filled with legal papers, but I knew the officer holding the gun had not stopped me because he thought I was a young professional. Since I was a young, bearded black man dressed casually in jeans, most people would not assume I was a lawyer with a Harvard Law School degree. To the officer threatening to shoot me I looked like someone dangerous and guilty.

I had been sitting in my beat-up Honda Civic for over a quarter of an hour listening to music that could not be heard outside the vehicle. There was a Sly and the Family Stone retrospective playing on a local radio station that had so engaged me I couldn’t turn the radio off. It had been a long day at work. A neighbor must have been alarmed by the sight of a black man sitting in his car and called the police. My getting out of my car to explain to the police officer that this was my home and nothing criminal was taking place prompted him to pull his weapon.

Having drawn his weapon, the officer and his partner justified their threat of lethal force by dramatizing their fears and suspicions about me. They threw me on the back of my car, searched it illegally, and kept me on the street for fifteen humiliating minutes while neighbors gathered to view the dangerous criminal in their midst. When no crime was discovered and nothing incriminating turned up in a computerized background check on me, I was told by the two officers to consider myself lucky. While this was said as a taunt, they were right: I was lucky.

People of color in the United States, particularly young black men, are often assumed to be guilty and dangerous. In too many situations, black men are considered offenders incapable of being victims themselves. As a consequence of this country’s failure to address effectively its legacy of racial inequality, this presumption of guilt and the history that created it have significantly shaped every institution in American society, especially our criminal justice system.

At the Civil War’s end, black autonomy expanded but white supremacy remained deeply rooted. States began to look to the criminal justice system to construct policies and strategies to maintain the subordination of African-Americans. Convict leasing, the practice of “selling” the labor of state and local prisoners to private interests for state profit, used the criminal justice system to take away their political rights. State legislatures passed the Black Codes, which created new criminal offenses such as “vagrancy” and “loitering” and led to the mass arrest of black people. Then, relying on language in the Thirteenth Amendment that prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude “except as punishment for crime,” lawmakers authorized white-controlled governments to exploit the labor of African-Americans in private lease contracts or on state-owned farms.1 The legal scholar Jennifer Rae Taylor has observed:

While a black prisoner was a rarity during the slavery era (when slave masters were individually empowered to administer “discipline” to their human property), the solution to the free black population had become criminalization. In turn, the most common fate facing black convicts was to be sold into forced labor for the profit of the state.

Beginning as early as 1866 in states like Texas, Mississippi, and Georgia, convict leasing spread throughout the South and continued through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Leased black convicts faced deplorable, unsafe working conditions and brutal violence when they attempted to resist or escape bondage. An 1887 report by the Hinds County, Mississippi, grand jury recorded that six months after 204 convicts were leased to a man named McDonald, twenty were dead, nineteen had escaped, and twenty-three had been returned to the penitentiary disabled, ill, and near death. The penitentiary hospital was filled with sick and dying black men whose bodies bore “marks of the most inhuman and brutal treatment…so poor and emaciated that their bones almost come through the skin.”2

The explicit use of race to codify different kinds of offenses and punishments was challenged as unconstitutional, and criminal statutes were modified to avoid direct racial references, but the enforcement of the law didn’t change. Black people were routinely charged with a wide range of “offenses,” some of which whites were never charged with. African-Americans endured these challenges and humiliations and continued to rise up from slavery by seeking education and working hard under difficult conditions, but their refusal to act like slaves seemed only to provoke and agitate their white neighbors. This tension led to an era of lynching and violence that traumatized black people for decades.

Between the Civil War and World War II, thousands of African-Americans were lynched in the United States. Lynchings were brutal public murders that were tolerated by state and federal officials. These racially motivated acts, meant to bypass legal institutions in order to intimidate entire populations, became a form of terrorism. Lynching had a profound effect on race relations in the United States and defined the geographic, political, social, and economic conditions of African-Americans in ways that are still evident today.

Of the hundreds of black people lynched after being accused of rape and murder, very few were legally convicted of a crime, and many were demonstrably innocent. In 1918, for example, after a white woman was raped in Lewiston, North Carolina, a black suspect named Peter Bazemore was lynched by a mob before an investigation revealed that the real perpetrator had been a white man wearing blackface makeup.3 Hundreds more black people were lynched based on accusations of far less serious crimes, like arson, robbery, nonsexual assault, and vagrancy, many of which would not have been punishable by death even if the defendants had been convicted in a court of law. In addition, African-Americans were frequently lynched for not conforming to social customs or racial expectations, such as speaking to white people with less respect or formality than observers believed due.4

Many African-Americans were lynched not because they had been accused of committing a crime or social infraction, but simply because they were black and present when the preferred party could not be located. In 1901, Ballie Crutchfield’s brother allegedly found a lost wallet containing $120 and kept the money. He was arrested and about to be lynched by a mob in Smith County, Tennessee, when, at the last moment, he was able to break free and escape. Thwarted in their attempt to kill him, the mob turned their attention to his sister and lynched her instead, though she was not even alleged to have been involved in the theft.

New research continues to reveal the extent of lynching in America. The extraordinary documentation compiled by Professor Monroe Work (1866–1945) at Tuskegee University has been an invaluable historical resource for scholars, as has the joint work of sociologists Stewart Tolnay and E.M. Beck. These two sources are widely viewed as the most comprehensive collections of data on the subject in America. They have uncovered over three thousand instances of lynching between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and 1950 in the twelve states that had the most lynchings: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

Recently, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery, Alabama—of which I am the founder and executive director—spent five years and hundreds of hours reviewing this research and other documentation, including local newspapers, historical archives, court records, interviews, and reports in African-American newspapers. Our research documented more than four thousand racial terror lynchings between 1877 and 1950 in those twelve states, eight hundred more than had been previously reported. We distinguished “racial terror lynchings” from hangings or mob violence that followed some sort of criminal trial or were committed against nonminorities. However heinous, this second category of killings was a crude form of punishment. By contrast, racial terror lynchings were directed specifically at black people, with little bearing on an actual crime; the aim was to maintain white supremacy and political and economic racial subordination.

We also distinguished terror lynchings from other racial violence and hate crimes that were prosecuted as criminal acts, although prosecution for hate crimes committed against black people was rare before World War II. The lynchings we documented were acts of terrorism because they were murders carried out with impunity—sometimes in broad daylight, as Sherrilyn Ifill explains in her important book on the subject, On the Courthouse Lawn (2007)—whose perpetrators were never held accountable. These killings were not examples of “frontier justice,” because they generally took place in communities where there was a functioning criminal justice system that was deemed too good for African-Americans. Some “public spectacle lynchings” were even attended by the entire local white population and conducted as celebratory acts of racial control and domination.

Records show that racial terror lynchings from Reconstruction until World War II had six particularly common motivations: (1) a wildly distorted fear of interracial sex; (2) as a response to casual social transgressions; (3) after allegations of serious violent crime; (4) as public spectacle, which could be precipitated by any of the allegations named above; (5) as terroristic violence against the African-American population as a whole; and (6) as retribution for sharecroppers, ministers, and other community leaders who resisted mistreatment—the last becoming common between 1915 and 1945.

Our research confirmed that many victims of terror lynchings were murdered without being accused of any crime; they were killed for minor social transgressions or for asserting basic rights. Our conversations with survivors of lynchings also confirmed how directly lynching and racial terror motivated the forced migration of millions of black Americans out of the South. Thousands of people fled north for fear that a social misstep in an encounter with a white person might provoke a mob to show up and take their lives. Parents and spouses suffered what they characterized as “near-lynchings” and sent their loved ones away in frantic, desperate acts of protection.

The decline of lynching in America coincided with the increased use of capital punishment often following accelerated, unreliable legal processes in state courts. By the end of the 1930s, court-ordered executions outpaced lynchings in the former slave states for the first time. Two thirds of those executed that decade were black, and the trend continued: as African-Americans fell to just 22 percent of the southern population between 1910 and 1950, they constituted 75 percent of those executed.

Probably the most famous attempted “legal lynching” is the case of the “Scottsboro Boys,” nine young African-Americans charged with raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. During the trial, white mobs outside the courtroom demanded the teens’ executions. Represented by incompetent lawyers, the nine were convicted by all-white, all-male juries within two days, and all but the youngest were sentenced to death. When the NAACP and others launched a national movement to challenge the cursory proceedings, the legal scholar Stephen Bright has written, “the [white] people of Scottsboro did not understand the reaction. After all, they did not lynch the accused; they gave them a trial.”5 In reality, many defendants of the era learned that the prospect of being executed rather than lynched did little to introduce fairness into the outcome.

Though northern states had abolished public executions by 1850, some in the South maintained the practice until 1938. The spectacles were more often intended to deter mob lynchings than crimes. Following Will Mack’s execution by public hanging in Brandon, Mississippi, in 1909, the Brandon News reasoned:

Public hangings are wrong, but under the circumstances, the quiet acquiescence of the people to submit to a legal trial, and their good behavior throughout, left no alternative to the board of supervisors but to grant the almost universal demand for a public execution.

Even in southern states that had outlawed public hangings much earlier, mobs often successfully demanded them.

In Sumterville, Florida, in 1902, a black man named Henry Wilson was convicted of murder in a trial that lasted just two hours and forty minutes. To mollify the mob of armed whites that filled the courtroom, the judge promised a death sentence that would be carried out by public hanging—despite state law prohibiting public executions. Even so, when the execution was set for a later date, the enraged mob threatened, “We’ll hang him before sundown, governor or no governor.” In response, Florida officials moved up the date, authorized Wilson to be hanged before the jeering mob, and congratulated themselves on having “avoided” a lynching.

‘The migration gained in momentum’; painting by Jacob Lawrence from his Migration series, 1940–1941. Credit: Museum of Modern Art, New York/© 2017 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund (LDF) began what would become a multidecade litigation strategy to challenge the American death penalty—which was used most actively in the South—as racially biased and unconstitutional. It won in Furman v. Georgia in 1972, when the Supreme Court struck down Georgia’s death penalty statute, holding that capital punishment still too closely resembled “self-help, vigilante justice, and lynch law” and “if any basis can be discerned for the selection of these few to be sentenced to die, it is the constitutionally impermissible basis of race.”

Southern opponents of the decision immediately decried it and set to writing new laws authorizing the death penalty. Following Furman, Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland accused the Court of “legislating” and “destroying our system of government,” while Georgia’s white supremacist lieutenant governor, Lester Maddox, called the decision “a license for anarchy, rape, and murder.” In December 1972, Florida became the first state after Furman to enact a new death penalty statute, and within two years, thirty-five states had followed suit. Proponents of Georgia’s new death penalty bill unapologetically borrowed the rhetoric of lynching, insisting, as Maddox put it:

There should be more hangings. Put more nooses on the gallows. We’ve got to make it safe on the street again…. It wouldn’t be too bad to hang some on the court house square, and let those who would plunder and destroy see.

State representative Guy Hill of Atlanta proposed a bill that would require death by hanging to take place “at or near the courthouse in the county in which the crime was committed.” Georgia state representative James H. “Sloppy” Floyd remarked, “If people commit these crimes, they ought to burn.” In 1976, in Gregg v. Georgia, the Supreme Court upheld Georgia’s new statute and thus reinstated the American death penalty, capitulating to the claim that legal executions were needed to prevent vigilante mob violence.

The new death penalty statutes continued to result in racial imbalance, and constitutional challenges persisted. In the 1987 case of McCleskey v. Kemp, the Supreme Court considered statistical evidence demonstrating that Georgia officials were more than four times as likely to impose a death sentence for the killing of a white person than a black person. Accepting the data as accurate, the Court conceded that racial disparities in sentencing “are an inevitable part of our criminal justice system” and upheld Warren McCleskey’s death sentence because he had failed to identify “a constitutionally significant risk of racial bias” in his case.

Today, large racial disparities continue in capital sentencing. African-Americans make up less than 13 percent of the national population, but nearly 42 percent of those currently on death row and 34 percent of those executed since 1976. In 96 percent of states where researchers have examined the relationship between race and the death penalty, results reveal a pattern of discrimination based on the race of the victim, the race of the defendant, or both. Meanwhile, in capital trials today the accused is often the only person of color in the courtroom and illegal racial discrimination in jury selection continues to be widespread. In Houston County, Alabama, prosecutors have excluded 80 percent of qualified African-Americans from serving as jurors in death penalty cases.

More than eight in ten American lynchings between 1889 and 1918 occurred in the South, and more than eight in ten of the more than 1,400 legal executions carried out in this country since 1976 have been in the South, where the legacy of the nation’s embrace of slavery lingers. Today death sentences are disproportionately meted out to African-Americans accused of crimes against white victims; efforts to combat racial bias and create federal protection against it in death penalty cases remain thwarted by the familiar rhetoric of states’ rights. Regional data demonstrate that the modern American death penalty has its origins in racial terror and is, in the words of Bright, the legal scholar, “a direct descendant of lynching.”

In the face of this national ignominy, there is still an astonishing failure to acknowledge, discuss, or address the history of lynching. Many of the communities where lynchings took place have gone to great lengths to erect markers and memorials to the Civil War, to the Confederacy, and to events and incidents in which local power was violently reclaimed by white people. These communities celebrate and honor the architects of racial subordination and political leaders known for their defense of white supremacy. But in these same communities there are very few, if any, significant monuments or memorials that address the history and legacy of the struggle for racial equality and of lynching in particular. Many people who live in these places today have no awareness that race relations in their histories included terror and lynching. As Ifill has argued, the absence of memorials to lynching has deepened the injury to African-Americans and left the rest of the nation ignorant of this central part of our history.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, arguably the signal legal achievement of the civil rights movement, contained provisions designed to eliminate discrimination in voting, education, and employment, but did not address racial bias in criminal justice. Though it was the most insidious engine of the subordination of black people throughout the era of racial terror and its aftermath, the criminal justice system remains the institution in American life least affected by the civil rights movement. Mass incarceration in America today stands as a continuation of past abuses, still limiting opportunities for our nation’s most vulnerable citizens.

We can’t change our past, but we can acknowledge it and better shape our future. The United States is not the only country with a violent history of oppression. Many nations have been burdened by legacies of racial domination, foreign occupation, or tribal conflict resulting in pervasive human rights abuses or genocide. The commitment to truth and reconciliation in South Africa was critical to that nation’s recovery. Rwanda has embraced transitional justice to heal and move forward. Today in Germany, besides a number of large memorials to the Holocaust, visitors encounter markers and stones at the homes of Jewish families who were taken to the concentration camps. But in America, we barely acknowledge the history and legacy of slavery, we have done nothing to recognize the era of lynching, and only in the last few years have a few monuments to the Confederacy been removed in the South.

The crucial question concerning capital punishment is not whether people deserve to die for the crimes they commit but rather whether we deserve to kill. Given the racial disparities that still exist in this country, we should eliminate the death penalty and expressly identify our history of lynching as a basis for its abolition. Confronting implicit bias in police departments should be seen as essential in twenty-first-century policing.

What threatened to kill me on the streets of Atlanta when I was a young attorney wasn’t just a misguided police officer with a gun, it was the force of America’s history of racial injustice and the presumption of guilt it created. In America, no child should be born with a presumption of guilt, burdened with expectations of failure and dangerousness because of the color of her or his skin or a parent’s poverty. Black people in this nation should be afforded the same protection, safety, and opportunity to thrive as anyone else. But that won’t happen until we look squarely at our history and commit to engaging the past that continues to haunt us.

Bryan Stevenson is the Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative and the author of “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.” This essay is drawn from the collection “Policing the Black Man: Arrest, Prosecution, and Imprisonment,” edited and with an introduction by Angela J. Davis, which will be published in July by Pantheon.

#Bryan Stevenson#Black Lives Matter#Just Mercy#Policing in america#atlanta#Black Men#Black Women#Black History Matters#white supremacy#white lies#racial profiling#2023#13th amendment#Black Enslavement in america#The Civil Rights Act of 1964#white lies that kill Black Bodies#systemic racism#jim crow#jim crow laws#Black Codes#Lynching in america#Badges of Slavery

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madlad

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

#fbi#politics#us politics#secret service#department of justice#democrats are corrupt#democrats will destroy america#biden crime family#police#politicians

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

2,977 civilians died tragically in 9/11, 343 being firefighters.

Since then it has been “Never forget.” for over 20 years, the US attacked and destabilized an innocent country, and white ppl have further pushed the narrative that Muslims and Middle Easterners are all “evil terrorists”.

Now, in less than 6 months the OFFICIAL death toll in Gaza exceeds 30,000, half being CHILDREN. At least 200 doctors have died and many were TARGETED by IOF soldiers. I have seen children dismembered, maimed, sniped, run over, crushed, starved, scalped, exploded, burned, and strung up on the side of a building.

I have seen men, women, and children desperately digging through the rubble to find their mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, children, friends, lovers etc.

I have seen brave doctors run outside to save injured civilians while at extremely high risk of being shot by snipers.

I have seen a father carrying BAGS full of his children’s remains.

I have seen a young girl, no more than 9, with a leg, an arm, and a hand blown off while her scalp hangs from her skull.

I have seen doctors speak out against the cruelty and ethnic cleansing while surrounded by the bodies of those they tried to save.

I have seen hundreds of pictures of NICU babies who were going to die soon because the hospital was about to run out of electricity.

I have read the first hand story of a father who traded one of his children for one of his brother’s children so that if one group dies at least one of their children would make it.

I have read posts from lgbt+ KIDS talking about how they regret not kissing their crush because they just watched them DIE.

I have seen the public posts of IDF and IOF soldiers where they show off the underwear and lingerie they looted from the drawers of the Gazans they are massacring.

I have listened to the screams of mothers after hearing their child is dead.

I have watched a teen boy’s gaze harden into something cold and empty after his entire family died in front of him, leaving him completely alone.

I have seen an IOF soldier throw a father and his baby into a giant wood burning oven just for fun.

I have seen many children with shell-shock, shaking because their minds and bodies can’t comprehend the horrors they have experienced.

I have seen tanks run over women actively giving birth on the roads of Gaza.

I have watched oldest siblings, no more than 11, take on the responsibility of keeping their younger siblings safe. I cannot comprehend how incredibly stressful that must be.

A little 6yo girl was trapped for 2 weeks in a car surrounded by the dead bodies of her family as they rotted.

This is all done with American tax dollars while companies like McDonalds give free food to Israeli soldiers. We are quite literally paying for this. 20% of your work and hard earned money is paying for the genocide of innocent people in Palestine.

This is NOT a political issue. This is a human rights issue.

Pro-Palestine is Pro-Humanity.

#free palestine 🇵🇸#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#free gaza#gaza#gaza strip#gaza genocide#free palestine#protest#israhell#fuck israel#fuck the police#fuck biden#fuck billionaires#fuck america#vote third party#taxes#human rights#palestinian genocide#genocide#ethnic cleansing#9/11#middle east#islamophobia#anti zionisim#zionsim is terrorism

588 notes

·

View notes

Text

Repost with your own answer.

#Trump#asassination attempt#Biden#Department of Justice#Democrats#FBI#CIA#Ukraine#Palm /Beach County#Florida#local police#state police#repost#president trump#trump 2024#donald trump#america#america first#americans first#state politics#Trump International#ryan wesley routh#Routh

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

💥❤️💥

#DJT#justice#justice league#freedom fighters#veterans#truthers#california#America#law enforcement#police#freedom#us politics#fight for justice#standup#speak up#truth#please share#wwg1wga#MAGA

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

The difference between Democrats and Republicans:

Gus Walz, at age 17, saw his Dad, Tim Walz, up on stage, ready to accept his party's nomination for vice president. Gus was so overwhelmed with emotions that he gave his father a standing ovation as he wept. Gus made no attempt to hide or hinder his great joy, pride and love he has for his father.

Democrats celebrated Gus' reaction as a wonderful expression of the close-knit family values in the Walz household. Republicans, however, chose to publicly mock and ridicule the teenager, who is a special needs kid.

Kyle Rittenhouse, at age 17, heard about a Black Lives Matter protest regarding a police shooting in Wisconsin and drove all the way from his home in Illinois with a military-style semi-automatic rifle (the kind often used in mass shootings) to confront the protesters.

As he was threatening people with his assault rifle, brave BLM protesters tried to disarm the gunman. Kyle Rittenhouse killed two unarmed men that night, and by claiming self-defense —he got away with it.

Now, Rittenhouse is a celebrated speaker at Republican events, describing him as a "hero to millions." They give him standing ovations while chanting his name.

To review: Republicans tried to humiliate a teenager with disabilities because he openly expressed the love he has for his family. But, they praise another teenager for shooting to death two unarmed people who would be alive today if Kyle had just left his f*cking assault rifle at home.

The deranged, upside-down "values" of Trump's Republican Party are not just weird, not just perverse —they're dangerous.

#Gus Walz#kyle rittenhouse#republicans#politics#government#us politics#America#USA#vote#voting#democracy#beauty-funny-trippy#democrats#news#aesthetic#donald trump#trump#black lives matter#BLM#black tumblr#marjorie taylor greene#MTG#Tim Walz#dnc#gun control#gun violence#assault weapons ban#police#January 6

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

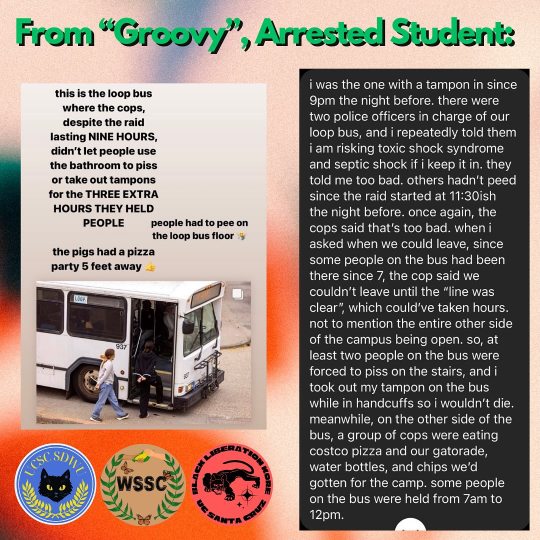

hi y'all. i know i don't make a lot of original posts here. however, on may 31st, i watched as my friends and peers were brutalized at the hands of cops from departments across california.

edit 6/12/24: students for justice in palestine at uc santa cruz has published a press release. it is easily the best way to understand what happened that night. please take a few minutes to read it.

uc santa cruz police made a statewide call for mutual aid in order to disband the gaza solidarity encampment located at the main entrance of the campus - initially established at the quarry in the center of campus on may 1, it moved to the entrance on may 20 in solidarity with the UAW strike. on tuesday, may 28, protesters barricaded the main entrance, cutting off the primary way of getting on campus; though the western entrance to UCSC was left unblocked (except for a few hours on tuesday), the main entrance remained obstructed until the raid began late on thursday night. this road blockage is what admin cited as the reason for the raid, along with "campus safety" and "academic freedom".

it's important to note that prior to blocking the road, students had been encamped for 28 days, and had been holding peaceful, law-abiding rallies since october. nothing worked. months of following the guidelines that admin had set, and of course student voices were dismissed and ignored by chancellor cynthia larive and cpevc lori kletzer (the latter of whom, by the way, showed up at 6 am "walking her dog" and smiled while watching her students get suffocated and beaten). the escalation would never have happened if student demands had been met at the very beginning.

hundreds of cops in riot gear from as far out as uc davis showed up to abuse students. over 115 arrests were made, including 3 ucsc professors, transported off by buses that were fifteen years past their intended end-of-use date and had also been servicing the campus prior. is this "campus safety"? is this "academic freedom"?

from just before midnight until approximately 9am on friday, cops kettled, suffocated, shoved, yanked, beat, and bruised students. one got a battery charge for writhing and bumping a cop after another slammed him in the head with a baton. another had a bag placed over their head, leading to suffocation, vomiting, and loss of consciousness. at least two protesters were confirmed to go to the ER that morning; many more have had to seek medical attention for lasting injuries.

arrestees were given a 14-day campus ban, including those who live on-campus (functionally evicting them & preventing access to their belongings), not to mention subjected to horrifyingly inhumane conditions:

you can find more information on various instagram accounts such as ucscsjp, ucscdivest, fjpucsc, ucsc_encampment, & jawsucsc. there's plenty of other organizations and people posting about this, too. please, don't let ucsc brush this under the rug. demand amnesty for the arrestees and protesters. contact any ucsc admin you can find. the uc has been utilizing police brutality to repress student voices across their institution, with ucla and uc irvine also being victims of this violence. do not let them get away with it.

free palestine, from the river to the sea. if seeing this violence sickens you, remember that this is not even a fraction of what the people of palestine have been enduring for decades. we will not let the university silence us, no matter what.

#palestine#ucsc#free gaza#the protester hit in the head with a baton is not okay btw. their concussion is severe and the injuries he sustained#might have permanent effects.#and remember: this is what is happening in biden's america.#this is not a hypothetical. this will not be “worse under trump”.#biden does not give a fuck!! israel has crossed his “red line” multiple times and he has done FUCK ALL#this is far from the only incident of police brutality under his administration and he has done FUCK ALL#he is not “the lesser of two evils” he is the exact same side of the exact same fucking coin#also if my usage of the phrase “from the river to the sea” is stopping you from reblogging this then your solidarity means nothing

249 notes

·

View notes