#Systematic Sampling

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

0 notes

Text

look computational psychiatry is a concept with a certain amount of cursed energy trailing behind it, but I'm really getting my ass chapped about a fundamental flaw in large scale data analysis that I've been complaining about for years. Here's what's bugging me:

When you're trying to understand a system as complex as behavioral tendencies, you cannot substitute large amounts of "low quality" data (data correlating more weakly with a trait of interest, say, or data that only measures one of several potential interacting factors that combine to create outcomes) for "high quality" data that inquiries more deeply about the system.

The reason for that is this: when we're trying to analyze data as scientists, we leave things we're not directly interrogating as randomized as possible on the assumption that either there is no main effect of those things on our data, or that balancing and randomizing those things will drown out whatever those effects are.

But the problem is this: sometimes there are not only strong effects in the data you haven't considered, but also they correlate: either with one of the main effects you do know about, or simply with one another.

This means that there is structure in your data. And you can't see it, which means that you can't account for it. Which means whatever your findings are, they won't generalize the moment you switch to a new population structured differently. Worse, you are incredibly vulnerable to sampling bias because the moment your sample fails to reflect the structure of the population you're up shit creek without a paddle. Twin studies are notoriously prone to this because white and middle to upper class twins are vastly more likely to be identified and recruited for them, because those are the people who respond to study queries and are easy to get hold of. GWAS data, also extremely prone to this issue. Anything you train machine learning datasets like ChatGPT on, where you're compiling unbelievably big datasets to try to "train out" the noise.

These approaches presuppose that sampling depth is enough to "drown out" any other conflicting main effects or interactions. What it actually typically does is obscure the impact of meaningful causative agents (hidden behind conflicting correlation factors you can't control for) and overstate the value of whatever significant main effects do manage to survive and fall out, even if they explain a pitiably small proportion of the variation in the population.

It's a natural response to the wondrous power afforded by modern advances in computing, but it's not a great way to understand a complex natural world.

#sciblr#big data#complaints#this is a small meeting with a lot of clinical focus which is making me even more irritated natch#see also similar complaints when samples are systematically filtered

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cluster Sampling: Types, Advantages, Limitations, and Examples

Explore the various types, advantages, limitations, and real-world examples of cluster sampling in our informative blog. Learn how this sampling method can help researchers gather data efficiently and effectively for insightful analysis.

#Cluster sampling#Sampling techniques#Cluster sampling definition#Cluster sampling steps#Types of cluster sampling#Advantages of cluster sampling#Limitations of cluster sampling#Cluster sampling comparison#Cluster sampling examples#Cluster sampling applications#Cluster sampling process#Cluster sampling methodology#Cluster sampling in research#Cluster sampling in surveys#Cluster sampling in statistics#Cluster sampling design#Cluster sampling procedure#Cluster sampling considerations#Cluster sampling analysis#Cluster sampling benefits#Cluster sampling challenges#Cluster sampling vs other methods#Cluster sampling vs stratified sampling#Cluster sampling vs random sampling#Cluster sampling vs systematic sampling#Cluster sampling vs convenience sampling#Cluster sampling vs multistage sampling#Cluster sampling vs quota sampling#Cluster sampling vs snowball sampling#Cluster sampling steps explained

0 notes

Text

i cut my public health teeth on this, he said. this will be within my wheelhouse, he said. i might as well challenge myself a little, in the spirit of fairness, he said.

#icarus moment#carving into this bullet i'm holding the names of everyone who decided what we really needed#was another paper lumping geriatric trans pts into a fruit salad systematic review of other geriatric queers#i love the rest of you beyond belief but for once i would like someone to think that maybe. maybe. there are some intracommunity issues#that are making geriatric trans outcomes even worse than other queer outcomes. and we should just to a trans study this time.#maybe there's a reason we disappear off your radar screen as we age - and maybe part of it is hostility from our own community#a second special bullet for the team that - in their case study sample - decided a 48:2 cisgay to trans ratio of interviewees was acceptabl#for a *LGBTQI* study. like buddy you got the LG. where's everybody else?

1 note

·

View note

Text

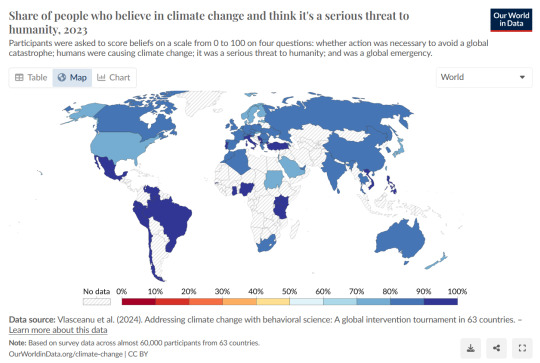

"People across the world, and the political spectrum, underestimate levels of support for climate action.

This “perception gap” matters. Governments will change policy if they think they have strong public backing. Companies need to know that consumers want to see low-carbon products and changes in business practices. We’re all more likely to make changes if we think others will do the same.

If governments, companies, innovators, and our neighbors know that most people are worried about the climate and want to see change, they’ll be more willing to drive it.

On the flip side, if we systematically underestimate widespread support, we’ll keep quiet for fear of “rocking the boat”.

This matters not only within each country but also in how we cooperate internationally. No country can solve climate change on its own. If we think that people in other countries don’t care and won’t act, we’re more likely to sit back as we consider our efforts hopeless.

Support for climate action is high across the world

The majority of people in every country in the world worry about climate change and support policies to tackle it. We can see this in the survey data shown on the map.

Surveys can produce unreliable — even conflicting — results depending on the population sample, what questions are asked, and the framing, so I’ve looked at several reputable sources to see how they compare. While the figures vary a bit depending on the specific question asked, the results are pretty consistent.

In a recent paper published in Science Advances, Madalina Vlasceanu and colleagues surveyed 59,000 people across 63 countries.1 “Belief” in climate change was 86%. Here, “belief” was measured based on answers to questions about whether action was necessary to avoid a global catastrophe, whether humans were causing climate change, whether it was a serious threat to humanity, and whether it was a global emergency.

People think climate change is a serious threat, and humans are the cause. Concern was high across countries: even in the country with the lowest agreement, 73% agreed...

The majority also supported climate policies, with an average global score of 72%. “Policy support” was measured as the average across nine interventions, including carbon taxes on fossil fuels, expanding public transport, more renewable energy, more electric car chargers, taxes on airlines, and protecting forests. In the country with the lowest support, there was still a majority (59%) who supported these policies.

These scores are high considering the wide range of policies suggested.

Another recent paper published in Nature Climate Change found similarly high support for political change. Peter Andre et al. (2024) surveyed almost 130,000 individuals across 125 countries.2

89% wanted to see more political action. 86% think people in their country “should try to fight global warming” (explore the data). And 69% said they would be willing to contribute at least 1% of their income to tackle climate change...

Support for political action was strong across the world, as shown on the map below.

To ensure these results weren’t outliers, I looked at several other studies in the United States and the United Kingdom.

70% to 83% of Americans answered “yes” to a range of surveys focused on whether humans were causing climate change, whether it was a concern, and a threat to humanity. In the UK, the share who agreed was between 73% and 90%. I’ve left details of these surveys in the footnote.3

The fact is that the majority of people “believe” in climate change and think it’s a problem is consistent across studies."

-via Our World in Data, March 25, 2024

#climate change#climate action#climate hope#climate crisis#politics#global politics#environment#environmental news#good news#hope

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

For the past six years or so, this graph has been making its rounds on social media, always reappearing at conveniently timed moments…

The insinuation is loud and clear: parallels abound between 18th-century France and 21st-century USA. Cue the alarm bells—revolution is imminent! The 10% should panic, and ordinary folk should stock up on non-perishables and, of course, toilet paper, because it wouldn’t be a proper crisis without that particular frenzy. You know the drill.

Well, unfortunately, I have zero interest in commenting on the political implications or the parallels this graph is trying to make with today’s world. I have precisely zero interest in discussing modern-day politics here. And I also have zero interest in addressing the bottom graph.

This is not going to be one of those "the [insert random group of people] à la lanterne” (1) kind of posts. If you’re here for that, I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed.

What I am interested in is something much less click-worthy but far more useful: how historical data gets used and abused and why the illusion of historical parallels can be so seductive—and so misleading. It’s not glamorous, I’ll admit, but digging into this stuff teaches us a lot more than mindless rage.

So, let’s get into it. Step by step, we’ll examine the top graph, unpick its assumptions, and see whether its alarmist undertones hold any historical weight.

Step 1: Actually Look at the Picture and Use Your Brain

When I saw this graph, my first thought was, “That’s odd.” Not because it’s hard to believe the top 10% in 18th-century France controlled 60% of the wealth—that could very well be true. But because, in 15 years of studying the French Revolution, I’ve never encountered reliable data on wealth distribution from that period.

Why? Because to the best of my knowledge, no one was systematically tracking income or wealth across the population in the 18th century. There were no comprehensive records, no centralised statistics, and certainly no detailed breakdowns of who owned what across different classes. Graphs like this imply data, and data means either someone tracked it or someone made assumptions to reconstruct it. That’s not inherently bad, but it did get my spider senses tingling.

Then there’s the timeframe: 1760–1790. Thirty years is a long time— especially when discussing a period that included wars, failed financial policies, growing debt, and shifting social dynamics. Wealth distribution wouldn’t have stayed static during that time. Nobles who were at the top in 1760 could be destitute by 1790, while merchants starting out in 1760 could be climbing into the upper tiers by the end of the period. Economic mobility wasn’t common, but over three decades, it wasn’t unheard of either.

All of this raises questions about how this graph was created. Where’s the data coming from? How was it measured? And can we really trust it to represent such a complex period?

Step 2: Check the Fine Print

Since the graph seemed questionable, the obvious next step was to ask: Where does this thing come from? Luckily, the source is clearly cited at the bottom: “The Income Inequality of France in Historical Perspective” by Christian Morrisson and Wayne Snyder, published in the European Review of Economic History, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2000).

Great! A proper academic source. But, before diving into the article, there’s a crucial detail tucked into the fine print:

“Data for the bottom 40% in France is extrapolated given a single data point.”

What does that mean?

Extrapolation is a statistical method used to estimate unknown values by extending patterns or trends from a small sample of data. In this case, the graph’s creator used one single piece of data—one solitary data point—about the wealth of the bottom 40% of the French population. They then scaled or applied that one value to represent the entire group across the 30-year period (1760–1790).

Put simply, this means someone found one record—maybe a tax ledger, an income statement, or some financial data—pertaining to one specific year, region, or subset of the bottom 40%, and decided it was representative of the entire demographic for three decades.

Let’s be honest: you don’t need a degree in statistics to know that’s problematic. Using a single data point to make sweeping generalisations about a large, diverse population (let alone across an era of wars, famines, and economic shifts) is a massive leap. In fact, it’s about as reliable as guessing how the internet feels about a topic from a single tweet.

This immediately tells me that whatever numbers they claim for the bottom 40% of the population are, at best, speculative. At worst? Utterly meaningless.

It also raises another question: What kind of serious journal would let something like this slide? So, time to pull up the actual article and see what’s going on.

Step 3: Check the Sources

As I mentioned earlier, the source for this graph is conveniently listed at the bottom of the image. Three clicks later, I had downloaded the actual article: “The Income Inequality of France in Historical Perspective” by Morrisson and Snyder.

The first thing I noticed while skimming through the article? The graph itself is nowhere to be found in the publication.

This is important. It means the person who created the graph didn’t just lift it straight from the article—they derived it from the data in the publication. Now, that’s not necessarily a problem; secondary analysis of published data is common. But here’s the kicker: there’s no explanation in the screenshot of the graph about which dataset or calculations were used to make it. We’re left to guess.

So, to figure this out, I guess I’ll have to dive into the article itself, trying to identify where they might have pulled the numbers from. Translation: I signed myself up to read 20+ pages of economic history. Thrilling stuff.

But hey, someone has to do it. The things I endure to fight disinformation...

Step 4: Actually Assess the Sources Critically

It doesn’t take long, once you start reading the article, to realise that regardless of what the graph is based on, it’s bound to be somewhat unreliable. Right from the first paragraph, the authors of the paper point out the core issue with calculating income for 18th-century French households: THERE IS NO DATA.

The article is refreshingly honest about this. It states multiple times that there were no reliable income distribution estimates in France before World War II. To fill this gap, Morrisson and Snyder used a variety of proxy sources like the Capitation Tax Records (2), historical socio-professional tables, and Isnard’s income distribution estimates (3).

After reading the whole paper, I can say their methodology is intriguing and very reasonable. They’ve pieced together what they could by using available evidence, and their process is quite well thought-out. I won’t rehash their entire argument here, but if you’re curious, I’d genuinely recommend giving it a read.

Most importantly, the authors are painfully aware of the limitations of their approach. They make it very clear that their estimates are a form of educated guesswork—evidence-based, yes, but still guesswork. At no point do they overstate their findings or present their conclusions as definitive

As such, instead of concluding with a single, definitive version of the income distribution, they offer multiple possible scenarios.

It’s not as flashy as a bold, tidy graph, is it? But it’s far more honest—and far more reflective of the complexities involved in reconstructing historical economic data.

Step 5: Run the numbers

Now that we’ve established the authors of the paper don’t actually propose a definitive income distribution, the question remains: where did the creators of the graph get their data? More specifically, which of the proposed distributions did they use?

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to locate the original article or post containing the graph. Admittedly, I haven’t tried very hard, but the first few pages of Google results just link back to Twitter, Reddit, Facebook, and Tumblr posts. In short, all I have to go on is this screenshot.

I’ll give the graph creators the benefit of the doubt and assume that, in the full article, they explain where they sourced their data. I really hope they do—because they absolutely should.

That being said, based on the information in Morrisson and Snyder’s paper, I’d make an educated guess that the data came from Table 6 or Table 10, as these are the sections where the authors attempt to provide income distribution estimates.

Now, which dataset does the graph use? Spoiler: None of them.

How can we tell? Since I don’t have access to the raw data or the article where this graph might have been originally posted, I resorted to a rather unscientific method: I used a graphical design program to divide each bar of the chart into 2.5% increments and measure the approximate percentage for each income group.

Here’s what I found:

Now, take a moment to spot the issue. Do you see it?

The problem is glaring: NONE of the datasets from the paper fit the graph. Granted, my measurements are just estimates, so there might be some rounding errors. But the discrepancies are impossible to ignore, particularly for the bottom 40% and the top 10%.

In Morrisson and Snyder’s paper, the lowest estimate for the bottom 40% (1st and 2nd quintiles) is 10%. Even if we use the most conservative proxy, the Capitation Tax estimate, it’s 9%. But the graph claims the bottom 40% held only 6%.

For the top 10% (10th decile), the highest estimate in the paper is 53%. Yet the graph inflates this to 60%.

Step 6: For fun, I made my own bar charts

Because I enjoy this sort of thing (yes, this is what I consider fun—I’m a very fun person), I decided to use the data from the paper to create my own bar charts. Here’s what came out:

What do you notice?

While the results don’t exactly scream “healthy economy,” they look much less dramatic than the graph we started with. The creators of the graph have clearly exaggerated the disparities, making inequality seem worse.

Step 7: Understand the context before drawing conclusions

Numbers, by themselves, mean nothing. Absolutely nothing.

I could tell you right now that 47% of people admit to arguing with inanimate objects when they don’t work, with printers being the most common offender, and you’d probably believe it. Why? Because it sounds plausible—printers are frustrating, I’ve used a percentage, and I’ve phrased it in a way that sounds “academic.”

You likely wouldn’t even pause to consider that I’m claiming 3.8 billion people argue with inanimate objects. And let’s be real: 3.8 billion is such an incomprehensibly large number that our brains tend to gloss over it.

If, instead, I said, “Half of your friends probably argue with their printers,” you might stop and think, “Wait, that seems a bit unlikely.” (For the record, I completely made that up—I have no clue how many people yell at their stoves or complain to their toasters.)

The point? Numbers mean nothing unless we put them into context.

The original paper does this well by contextualising its estimates, primarily through the calculation of the Gini coefficient (4).

The authors estimate France’s Gini coefficient in the late 18th century to be 0.59, indicating significant income inequality. However, they compare this figure to other regions and periods to provide a clearer picture:

Amsterdam (1742): Much higher inequality, with a Gini of 0.69.

Britain (1759): Lower inequality, with a Gini of 0.52, which rose to 0.59 by 1801.

Prussia (mid-19th century): Far less inequality, with a Gini of 0.34–0.36.

This comparison shows that income inequality wasn’t unique to France. Other regions experienced similar or even higher levels of inequality without spontaneously erupting into revolution.

Accounting for Variations

The authors also recalculated the Gini coefficient to account for potential variations. They assumed that the income of the top quintile (the wealthiest 20%) could vary by ±10%. Here’s what they found:

If the top quintile earned 10% more, the Gini coefficient rose to 0.66, placing France significantly above other European countries of the time.

If the top quintile earned 10% less, the Gini dropped to 0.55, bringing France closer to Britain’s level.

Ultimately, the authors admit there’s uncertainty about the exact level of inequality in France. Their best guess is that it was comparable to other countries or somewhat worse.

Step 8: Drawing Some Conclusions

Saying that most people in the 18th century were poor and miserable—perhaps the French more so than others—isn’t exactly a compelling statement if your goal is to gather clicks or make a dramatic political point.

It’s incredibly tempting to look at the past and find exactly what we want to see in it. History often acts as a mirror, reflecting our own expectations unless we challenge ourselves to think critically. Whether you call it wishful thinking or confirmation bias, it’s easy to project the future onto the past.

Looking at the initial graph, I understand why someone might fall into this trap. Simple, tidy narratives are appealing to everyone. But if you’ve studied history, you’ll know that such narratives are a myth. Human nature may not have changed in thousands of years, but the contexts we inhabit are so vastly different that direct parallels are meaningless.

So, is revolution imminent? Well, that’s up to you—not some random graph on the internet.

Notes

(1) A la lanterne was a revolutionary cry during the French Revolution, symbolising mob justice where individuals were sometimes hanged from lampposts as a form of public execution

(2) The capitation tax was a fixed head tax implemented in France during the Ancien Régime. It was levied on individuals, with the amount owed determined by their social and professional status. Unlike a proportional income tax, it was based on pre-assigned categories rather than actual earnings, meaning nobles, clergy, and commoners paid different rates regardless of their actual wealth or income.

(3) Jean-Baptiste Isnard was an 18th-century economist. These estimates attempted to describe the theoretical distribution of income among different social classes in pre-revolutionary France. Isnard’s work aimed to categorise income across groups like nobles, clergy, and commoners, providing a broad picture of economic disparity during the period.

(4) The Gini coefficient (or Gini index) is a widely used statistical measure of inequality within a population, specifically in terms of income or wealth distribution. It ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates perfect equality (everyone has the same income or wealth), and 1 represents maximum inequality (one person or household holds all the wealth).

#frev#french revolution#history#disinformation#income inequality#critical thinking#amateurvoltaire's essay ramblings#don't believe everything you see online#even if you really really want to

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

you probably shouldn’t livestream mass, systematic slaughter and extermination of children. people will get really irrationally mad about that. there’s something about seeing dead children that seems to be somewhat harmful to the average persons mental health. just fyi. i know there aren’t a lot of studies on this and these are just unfounded assumptions. but i’ve talked to a lot of people and none of them seem very excited when they talk about seeing dead children. i get that im not talking to the “target audience” for these dead kids, but the sample size is pretty significant.

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things You May Not Know: Angeal & Genesis Edition

The reason there are Angeal copies is that Hollander took the samples when Angeal was having his breakdown.

Genesis' injury happened months before he left Shinra. It is only when Hollander is investigating the injury that he finds out about the copy phenomenon and tells Genesis anything so there was a period of time where Genesis wasn't healing and no one knew why.

Upon Angeal and Genesis meeting in Wutai after Genesis deserts, Genesis tries to explain Project G. Angeal, likely thinking Genesis is suffering from some kind of side effect from his condition or some weird treatment that produced copies via Hollander, tries to convince Genesis to come back to Shinra to fix it. He only goes with Genesis because he doesn't think he can convince him in time and thinks it will all be cleared up if they go to Banora and he can get Genesis to come back once they clear up that none of that happened.

Genesis and Angeal are older than Sephiroth but not by much. Project G notes were used and added to for Sephiroth's creation.

Project G was considered a failure when Genesis and Angeal were babies and 'frozen'. Shortly after this, Angeal's mother Gillian tried to run with Angeal but they were caught and sent to Banora, a place with Shinra trustees. They were still under surveillance and reports written on them, but they were not actively utilised and joined Shinra as teenagers after seeing Sephiroth's hero routine.

The difference in them is down to the type of Jenova cells they received. Sephiroth was injected with pure J-cells early in Lucrecia's pregnancy. Genesis was injected with modified J-cells developed through Gillian injecting herself with pure J-cells and Angeal inherited those same modified J-cells (known as G-cells) as Gillian's biological son.

Genesis had already asked Gillian for help before telling Angeal anything and been refused. Hollander insists they need her help - what they need is not her cells but rather her knowledge and information which she won't give - which implies Gillian had more knowledge of the project than he did and may explain why G stands for Gillian. Whether or not she could have saved him is something SE says is something they'd like to keep secret for now.

Other than the trustees, Genesis's parents and Gillian, no one else in Banora knew that the place was essentially a free range Jenova project. There was a large population employed by Shinra. Even though they were considered failures in comparison to Sephiroth, they were still expected to develop some kind of extraordinary abilities and this is why they were kept under surveillance and why Genesis's foster parents send reports.

Shinra did offer Gillian hush money but she wanted them to have nothing to do with her or Angeal. Even though they lived in poverty, she stuck stubbornly to this. This is one of the reasons why her reactions in Angeal's dream in Ever Crisis are suspect and likely not what actually happened any more than Sephiroth's dreams of Lucrecia do.

It is said that of Project G, Genesis and Angeal were the only survivors which implies there were other attempts with G-cells.

Genesis's foster parents eventually grew attached to him and began to lie on their reports. What they were lying about is unclear given they were supposed to be looking for extraordinary abilities but it is said they were willing to betray Shinra by that point to 'protect' him.

Genesis may have had some private training thanks to Shinra before he entered the SOLDIER program but not the kind of systematic training that Sephiroth had. Angeal does not because his mother was so heavily against him having anything to do Shinra.

Whether Gillian and Hollander were married is something they do not want to reveal yet.

There is something unique in Genesis's genetic structure despite the kids from G being seen as failures. Samples of this were taken and the Deepground labs were set up under Midgar, eventually resulting in Rosso, Weiss and Nero and giving those cells to the later Tsviets.

#lore dumping#genesis rhapsodos#angeal hewley#ff7#information comes from the ultimania q&a largely if you're curious#but i'm always losing it so i'm shoving it here

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

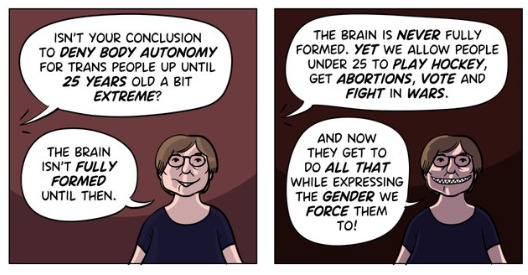

By: Andy L.

Published: Apr 14, 2024

It has now been just little under a week since the publication of the long anticipated NHS independent review of gender identity services for children and young people, the Cass Review.

The review recommends sweeping changes to child services in the NHS, not least the abandonment of what is known as the “affirmation model” and the associated use of puberty blockers and, later, cross-sex hormones. The evidence base could not support the use of such drastic treatments, and this approach was failing to address the complexities of health problems in such children.

Many trans advocacy groups appear to be cautiously welcoming these recommendations. However, there are many who are not and have quickly tried to condemn the review. Within almost hours, “press releases“, tweets and commentaries tried to rubbish the report and included statements that were simply not true. An angry letter from many “academics”, including Andrew Wakefield, has been published. These myths have been subsequently spreading like wildfire.

Here I wish to tackle some of those myths and misrepresentations.

-

Myth 1: 98% of all studies in this area were ignored

Fact

A comprehensive search was performed for all studies addressing the clinical questions under investigation, and over 100 were discovered. All these studies were evaluated for their quality and risk of bias. Only 2% of the studies met the criteria for the highest quality rating, but all high and medium quality (50%+) studies were further analysed to synthesise overall conclusions.

Explanation

The Cass Review aimed to base its recommendations on the comprehensive body of evidence available. While individual studies may demonstrate positive outcomes for the use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones in children, the quality of these studies may vary. Therefore, the review sought to assess not only the findings of each study but also the reliability of those findings.

Studies exhibit variability in quality. Quality impacts the reliability of any conclusions that can be drawn. Some may have small sample sizes, while others may involve cohorts that differ from the target patient population. For instance, if a study primarily involves men in their 30s, their experiences may differ significantly from those of teenage girls, who constitute the a primary patient group of interest. Numerous factors can contribute to poor study quality.

Bias is also a big factor. Many people view claims of a biased study as meaning the researchers had ideological or predetermined goals and so might misrepresent their work. That may be true. But that is not what bias means when we evaluate medical trials.

In this case we are interested in statistical bias. This is where the numbers can mislead us in some way. For example, if your study started with lots of patients but many dropped out then statistical bias may creep in as your drop-outs might be the ones with the worst experiences. Your study patients are not on average like all the possible patients.

If then we want to look at a lot papers to find out if a treatment works, we want to be sure that we pay much more attention to those papers that look like they may have less risk of bias or quality issues. The poor quality papers may have positive results that are due to poor study design or execution and not because the treatment works.

The Cass Review team commissioned researchers at York University to search for all relevant papers on childhood use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for treating “gender dysphoria”. The researchers then graded each paper by established methods to determine quality, and then disregarded all low quality papers to help ensure they did not mislead.

The Review states,

The systematic review on interventions to suppress puberty (Taylor et al: Puberty suppression) provides an update to the NICE review (2020a). It identified 50 studies looking at different aspects of gender-related, psychosocial, physiological and cognitive outcomes of puberty suppression. Quality was assessed on a standardised scale. There was one high quality study, 25 moderate quality studies and 24 low quality studies. The low quality studies were excluded from the synthesis of results.

As can be seen, the conclusions that were based on the synthesis of studies only rejected 24 out of 50 studies – less than half. The myth has arisen that the synthesis only included the one high quality study. That is simply untrue.

There were two such literature reviews: the other was for cross-sex hormones. This study found 19 out of 53 studies were low quality and so were not used in synthesis. Only one study was classed as high quality – the rest medium quality and so were used in the analysis.

12 cohort, 9 cross-sectional and 32 pre–post studies were included (n=53). One cohort study was high-quality. Other studies were moderate (n=33) and low-quality (n=19). Synthesis of high and moderate-quality studies showed consistent evidence demonstrating induction of puberty, although with varying feminising/masculinising effects. There was limited evidence regarding gender dysphoria, body satisfaction, psychosocial and cognitive outcomes, and fertility.

Again, it is myth that 98% of studies were discarded. The truth is that over a hundred studies were read and appraised. About half of them were graded to be of too poor quality to reliably include in a synthesis of all the evidence. if you include low quality evidence, your over-all conclusions can be at risk from results that are very unreliable. As they say – GIGO – Garbage In Garbage Out.

Nonetheless, despite analysing the higher quality studies, there was no clear evidence that emerged that puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones were safe and effective. The BMJ editorial summed this up perfectly,

One emerging criticism of the Cass review is that it set the methodological bar too high for research to be included in its analysis and discarded too many studies on the basis of quality. In fact, the reality is different: studies in gender medicine fall woefully short in terms of methodological rigour; the methodological bar for gender medicine studies was set too low, generating research findings that are therefore hard to interpret. The methodological quality of research matters because a drug efficacy study in humans with an inappropriate or no control group is a potential breach of research ethics. Offering treatments without an adequate understanding of benefits and harms is unethical. All of this matters even more when the treatments are not trivial; puberty blockers and hormone therapies are major, life altering interventions. Yet this inconclusive and unacceptable evidence base was used to inform influential clinical guidelines, such as those of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), which themselves were cascaded into the development of subsequent guidelines internationally.

-

Myth 2: Cass recommended no Trans Healthcare for Under 25s

Fact

The Cass Review does not contain any recommendation or suggestion advocating for the withholding of transgender healthcare until the age of 25, nor does it propose a prohibition on individuals transitioning.

Explanation

This myth appears to be a misreading of one of the recommendations.

The Cass Review expressed concerns regarding the necessity for children to transition to adult service provision at the age of 18, a critical phase in their development and potential treatment. Children were deemed particularly vulnerable during this period, facing potential discontinuity of care as they transitioned to other clinics and care providers. Furthermore, the transition made follow-up of patients more challenging.

Cass then says,

Taking account of all the above issues, a follow-through service continuing up to age 25 would remove the need for transition at this vulnerable time and benefit both this younger population and the adult population. This will have the added benefit in the longer-term of also increasing the capacity of adult provision across the country as more gender services are established.

Cass want to set up continuity of service provision by ensure they remain within the same clinical setting and with the same care providers until they are 25. This says nothing about withdrawing any form of treatment that may be appropriate in the adult care pathway. Cass is explicit in saying her report is making no recommendations as to what that care should look like for over 18s.

It looks the myth has arisen from a bizarre misreading of the phrase “remove the need for transition”. Activists appear to think this means that there should be no “gender transition” whereas it is obvious this is referring to “care transition���.

-

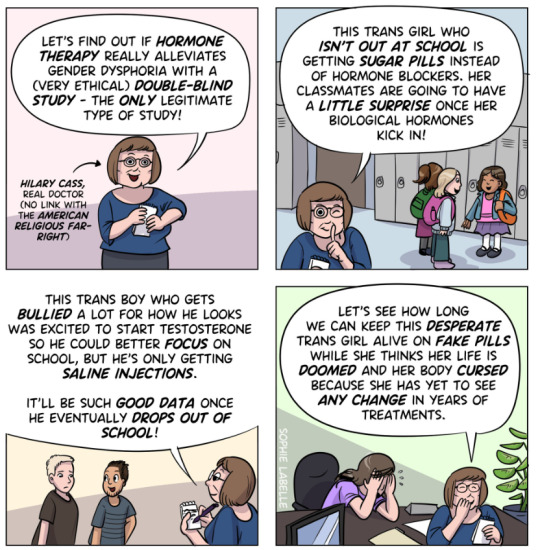

Myth 3: Cass is demanding only Double Blind Randomised Controlled Trials be used as evidence in “Trans Healthcare”

Fact

While it is acknowledged that conducting double-blind randomized controlled trials (DBRCT) for puberty blockers in children would present significant ethical and practical challenges, the Cass Review does not advocate solely for the use of DBRCT trials in making treatment recommendations, nor does it mandate that future trials adhere strictly to such protocols. Rather, the review extensively discusses the necessity for appropriate trial designs that are both ethical and practical, emphasizing the importance of maintaining high methodological quality.

Explanation

Cass goes into great detail explaining the nature of clinical evidence and how that can vary in quality depending on the trial design and how it is implemented and analysed. She sets out why Double Blind Randomised Controlled Trials are the ‘gold standard’ as they minimise the risks of confounding factors misleading you and helping to understand cause and effect, for example. (See Explanatory Box 1 in the Report).

Doctors rely on evidence to guide treatment decisions, which can be discussed with patients to facilitate informed choices considering the known benefits and risks of proposed treatments.

Evidence can range from a doctor’s personal experience to more formal sources. For instance, a doctor may draw on their own extensive experience treating patients, known as ‘Expert Opinion.’ While valuable, this method isn’t foolproof, as historical inaccuracies in medical beliefs have shown.

Consulting other doctors’ experiences, especially if documented in published case reports, can offer additional insight. However, these reports have limitations, such as their inability to establish causality between treatment and outcome. For example, if a patient with a bad back improves after swimming, it’s uncertain whether swimming directly caused the improvement or if the back would have healed naturally.

Further up the hierarchy of clinical evidence are papers that examine cohorts of patients, typically involving multiple case studies with statistical analysis. While offering better evidence, they still have potential biases and limitations.

This illustrates the ‘pyramid of clinical evidence,’ which categorises different types of evidence based on their quality and reliability in informing treatment decisions

The above diagram is published in the Cass Review as part of Explanatory Box 1.

We can see from the report and papers that Cass did not insist that only randomised controlled trials were used to assess the evidence. The York team that conducted the analyses chose a method to asses the quality of studies called the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. This is a method best suited for non RCT trials. Cass has selected an assessment method best suited for the nature of the available evidence rather than taken a dogmatic approach on the need for DBRCTs. The results of this method were discussed about countering Myth 1.

Explainer on the Newcastle Ottawa Scale

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) is a tool designed to assess the quality of non-randomized studies, particularly observational studies such as cohort and case-control studies. It provides a structured method for evaluating the risk of bias in these types of studies and has become widely used in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

The NOS consists of a set of criteria grouped into three main categories: selection of study groups, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest. Each category contains several items, and each item is scored based on predefined criteria. The total score indicates the overall quality of the study, with higher scores indicating lower risk of bias.

This scale is best applied when conducting systematic reviews or meta-analyses that include non-randomized studies. By using the NOS, researchers can objectively assess the quality of each study included in their review, allowing them to weigh the evidence appropriately and draw more reliable conclusions.

One of the strengths of the NOS is its flexibility and simplicity. It provides a standardized framework for evaluating study quality, yet it can be adapted to different study designs and research questions. Additionally, the NOS emphasizes key methodological aspects that are crucial for reducing bias in observational studies, such as appropriate selection of study participants and controlling for confounding factors.

Another advantage of the NOS is its widespread use and acceptance in the research community. Many systematic reviews and meta-analyses rely on the NOS to assess the quality of included studies, making it easier for researchers to compare and interpret findings across different studies.

As for future studies, Cass makes no demand only DBRCTs are conducted. What is highlighted is at the very least that service providers build a research capacity to fill in the evidence gaps.

The national infrastructure should be put in place to manage data collection and audit and this should be used to drive continuous quality improvement and research in an active learning environment.

-

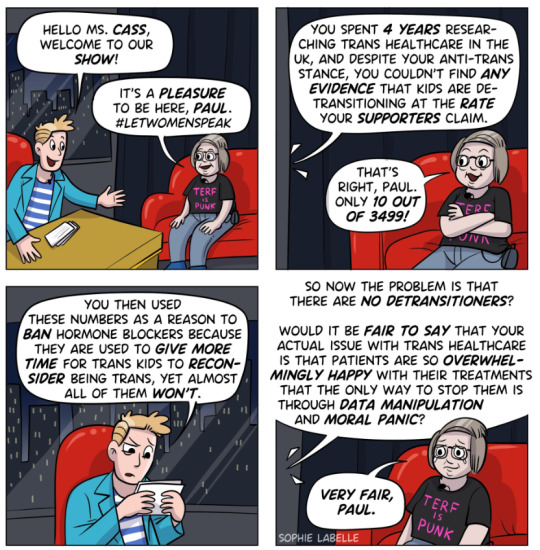

Myth 4: There were less than 10 detransitioners out of 3499 patients in the Cass study.

Fact

Cass was unable to determine the detransition rate. Although the GIDS audit study recorded fewer than 10 detransitioners, clinics declined to provide information to the review that would have enabled linking a child’s treatment to their adult outcome. The low recorded rates must be due in part to insufficient data availability.

Explanation

Cass says, “The percentage of people treated with hormones who subsequently detransition remains unknown due to the lack of long-term follow-up studies, although there is suggestion that numbers are increasing.”

The reported number are going to be low for a number of reasons, as Cass describes:

Estimates of the percentage of individuals who embark on a medical pathway and subsequently have regrets or detransition are hard to determine from GDC clinic data alone. There are several reasons for this:

Damningly, Cass describes the attempt by the review to establish “data linkage’ between records at the childhood gender clinics and adult services to look at longer term detransition and the clinics refused to cooperate with the Independent Review. The report notes the “…attempts to improve the evidence base have been thwarted by a lack of cooperation from the adult gender services”.

We know from other analyses of the data on detransitioning that the quality of data is exceptionally poor and the actual rates of detransition and regret are unknown. This is especially worrying when older data, such as reported in WPATH 7, suggest natural rates of decrease in dysphoria without treatment are very high.

Gender dysphoria during childhood does not inevitably continue into adulthood. Rather, in follow-up studies of prepubertal children (mainly boys) who were referred to clinics for assessment of gender dysphoria, the dysphoria persisted into adulthood for only 6–23% of children.

This suggests that active affirmative treatment may be locking in a trans identity into the majority of children who would otherwise desist with trans ideation and live unmedicated lives.

I shall add more myths as they become spread.

==

It's not so much "myths and misconceptions" as deliberate misinformation. Genderists are scrambling to prop up their faith-based beliefs the same way homeopaths do. Both are fraudulent.

#Andy L.#Cass Review#Cass Report#Dr. Hilary Cass#Hilary Cass#misinformation#myths#misconceptions#detrans#detransition#gender affirming healthcare#gender affirming care#gender affirmation#affirmation model#medical corruption#medical malpractice#medical scandal#systematic review#religion is a mental illness

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research Discovers Ancient Egyptian Mummies Smell Nice

At first whiff, it sounds repulsive: sniff the essence of an ancient corpse.

But researchers who indulged their curiosity in the name of science found that well-preserved Egyptian mummies actually smell pretty good.

“In films and books, terrible things happen to those who smell mummified bodies,” said Cecilia Bembibre, director of research at University College London’s Institute for Sustainable Heritage. “We were surprised at the pleasantness of them.”

“Woody,” “spicy” and “sweet” were the leading descriptions from what sounded more like a wine tasting than a mummy sniffing exercise. Floral notes were also detected, which could be from pine and juniper resins used in embalming.

The study published Thursday in the Journal of the American Chemical Society used both chemical analysis and a panel of human sniffers to evaluate the odors from nine mummies as old as 5,000 years that had been either in storage or on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The researchers wanted to systematically study the smell of mummies because it has long been a subject of fascination for the public and researchers alike, said Bembibre, one of the report’s authors. Archeologists, historians, conservators and even fiction writers have devoted pages of their work to the subject — for good reason.

Scent was an important consideration in the mummification process that used oils, waxes and balms to preserve the body and its spirit for the afterlife. The practice was largely reserved for pharaohs and nobility and pleasant smells were associated with purity and deities while bad odors were signs of corruption and decay.

Without sampling the mummies themselves, which would be invasive, researchers from UCL and the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia were able to measure whether aromas were coming from the archaeological item, pesticides or other products used to conserve the remains, or from deterioration due to mold, bacteria or microorganisms.

“We were quite worried that we might find notes or hints of decaying bodies, which wasn’t the case,” said Matija Strlič, a chemistry professor at the University of Ljubljana. “We were specifically worried that there might be indications of microbial degradation, but that was not the case, which means that the environment in this museum, is actually quite good in terms of preservation.”

Using technical instruments to measure and quantify air molecules emitted from sarcophagi to determine the state of preservation without touching the mummies was like the Holy Grail, Strlič said.

“It tells us potentially what social class a mummy was from and and therefore reveals a lot of information about the mummified body that is relevant not just to conservators, but to curators and archeologists as well,” he said. “We believe that this approach is potentially of huge interest to other types of museum collections.”

Barbara Huber, a postdoctoral researcher at Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Germany who was not involved in the study, said the findings provide crucial data on compounds that could preserve or degrade mummified remains. The information could be used to better protect the ancient bodies for future generations.

“However, the research also underscores a key challenge: the smells detected today are not necessarily those from the time of mummification,” Huber said. “Over thousands of years, evaporation, oxidation, and even storage conditions have significantly altered the original scent profile.”

Huber authored a study two years ago that analyzed residue from a jar that had contained mummified organs of a noblewoman to identify embalming ingredients, their origins and what they revealed about trade routes. She then worked with a perfumer to create an interpretation of the embalming scent, known as “Scent of Eternity,” for an exhibition at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark.

Researchers of the current study hope to do something similar, using their findings to develop “smellscapes” to artificially recreate the scents they detected and enhance the experience for future museumgoers.

“Museums have been called white cubes, where you are prompted to read, to see, to approach everything from a distance with your eyes,” Bembibre said. “Observing the mummified bodies through a glass case reduces the experience because we don’t get to smell them. We don’t get to know about the mummification process in an experiential way, which is one of the ways that we understand and engage with the world.”

#Research Discovers Ancient Egyptian Mummies Smell Nice#Egyptian Museum in Cairo#ancient tombs#ancient graves#grave goods#ancient artifacts#archeology#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian hieroglyphs#egyptian art#ancient art

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

FANFIC PROMPT chase says he knows cameron likes flowers. how . why. etc

GREAT PROMPT I FINALLY GOT SOMETHING FINISHED FOR THE FIRST TIME IN LIKE A MONTH:

It’s a rare day that all three of them get posted to break-in duty—by the time a patient gets to House, they’re sick enough to need at least one of the fellows to monitor them round-the-clock, especially since House has a mutual grudge against all the nurses—but as far as cases go, this one is open and shut; it’s clearly an allergic reaction, since the symptoms have almost completely disappeared since they admitted her to hospital (Laurel, 25, tinnitus, tooth pain and tightness in the chest), so the question is really just to what since the standard allergy panels have come back clear. Besides which, Laurel’s house is really more of a mansion—they kind of need the extra manpower. Chase suspects that that’s what has Foreman muttering so darkly under his breath while he picks the lock on the front door. But truth be told, he isn’t paying much attention. He’s watching Cameron, who’s ankle-deep in the flowerbeds and systematically pruning one of each flower and decanting them into neatly-labelled sample bags.

It is summer—July, no less—and, with a heatwave to boot, it’s too hot to wear proper office attire, especially when the air-conditioning keeps breaking. Back at PPTH, House has abandoned the pretence of throwing a button-up over his usual array of band t-shirts (although Chase quietly suspects that this also has something to do with Stacy’s continued presence), and Cuddy has issued a memo allowing doctors to eschew their lab coats while doing rounds. Chase has opted for his baggiest jeans and a polo he hasn’t worn since he was last in Melbourne; even Foreman is tie-less, sleeves rolled up, though he’s of course still wearing slacks and a button-up. And Cameron—Cameron’s wearing a dress for the first time Chase can remember outside the annual oncology benefit, with enough top buttons left open for the sweat gleaming on her collarbone to be visible. She keeps grumbling while tightening her ponytail, like she can force her hair to stop sticking to the back of her neck through sheer willpower. Chase is doing what he thinks is a pretty admirable job of trying not to stare. The key word being trying.

“Got it,” Foreman says loudly, which jumps Chase back to attention; the movement makes Foreman shoot him a fairly peeved look. “Are you going to help Cameron, or are you going to make her sit in the sun all afternoon?”

Out of pure spite, Chase thinks about refusing—because who is Foreman to tell him what to do when he hasn’t even been on House’s team for a full year yet, because he notices that Foreman isn’t exactly running to go hang out in the dirt with Cameron and mess up his perfectly-shined dress shoes—but Cameron glances up at the sound of her name, looking equal parts annoyed at the implication she needs help and also hopeful. And Chase would much rather hang out with Cameron than listen to Foreman snipe at him, even if it close to 100 degrees outside (37°C, a slightly childish and more homesick voice in his head pipes up), so. He settles for rolling his eyes at Foreman, and trudging over to Cameron with what he hopes is an entirely-repressed grimace, instead.

“It’s like the Gardens of Babylon over here,” Chase remarks, reaching into his messenger bag to pull out a pair of gloves. The thought of the latex sweating against his skin is cringe-inducing, but so is the thought of House sending them back here tomorrow should they pollute the samples, so it has to be done. “How much do you think her gardener makes?”

“Probably not enough,” Cameron replies wryly, snipping off the head of a rose and holding it up to the light. It’s pretty enough, Chase supposes—the week of endless sun somehow hasn’t wilted any of its satiny, cream-coloured petals—but Cameron’s looking at it with a slightly awed expression, like she’s forgotten what she’s supposed to be doing. “I wish I had a garden,” she adds now, her voice dreamy. “But I kill basically every plant I touch, so maybe it’s for the best.”

“You like flowers?” Chase asks, a touch dubiously. There’s a zinnia within reach; he leans over to uproot it, and Cameron makes a slightly horrified squeak in the back of her throat. “I don’t have the shears, I can’t—“

“Here,” she says, practically thrusting them into his hand, her lips pursed in distaste. “Don’t just destroy it.”

“If she’s allergic to any of these, she’ll have to get rid of them all anyway,” Chase mutters, but does as he’s told. Louder, he adds, “So you do like flowers.”

He’s not really sure why he’s surprised. It’s a truism: women like flowers. Every woman Chase has dated liked them, anyway, even that banker—although he’s quick to stop grouping Cameron alongside the women he’s had sex with, because that is not a safe line of thought. Chase supposes that what he’s really surprised by is her willingness to admit it. Or not deny it—for Cameron, that’s essentially the same thing. Cameron gets weird about being into girly things, Chase reflects, passing her back the shears so she can gently behead a geranium; it’s why she never wears skirts, and put up all the office Christmas decorations in secret, and gets so funny whenever a patient compliments her hair or jewellery or make-up. It took her about six months to admit to him that her favourite colour is pink. It’s not like she’s embarrassed, Chase thinks. It’s just—

“I used to do flower arranging, before I met my husband,” Cameron says, so suddenly that Chase is glad she’s the one holding the shears instead of him, because it’s enough to make him flinch. She very carefully does not look at him as she continues, “I mean, I wasn’t very good at it. They ran a workshop as some kind of—stress relief thing during finals season when I was a freshman, and my roommate asked me to go with her. It’s more of a science than an art. It was fun.”

“Used to?” Chase presses, even though he thinks he already knows her answer as to why she stopped. Cameron lifts one shoulder and lets it fall in a limp imitation of a shrug.

“I did the flowers for my wedding,” she says. “I told everyone it was because it was cheaper that way, but really I just wanted to have control over something since my in-laws were paying for everything and it was, you know, really about him. Couldn’t look at any of it the same after he died.” Cameron peels off her gloves with a grimace, and sets about drying her damp hands on her skirt; this close, Chase can see how pale they are, how there really is zero indication that she was ever married at all. Everyone always talks about surgeons’ hands—it’s at least half of the reason why Chase did a surgery residency, he thinks guiltily—but Cameron’s are so small and fine-boned that he can’t help but think maybe everyone’s got the wrong end of the stick. “But I still like flowers. I just prefer them to be pre-arranged now,” Cameron finishes, glancing at him over her shoulder with a slightly puzzled wrinkle of her nose—caught out, Chase thinks, and pointedly rummages in his bag to pass her a fresh set of gloves so that she can’t see the guilt that is undoubtedly scribbled all over his face. “Oh, thanks.”

“No problem,” Chase says, a little gruff, and wonders if maybe he should’ve just stuck it out with Foreman after all. “Hey, you’re the immunologist. Do you think it’s a floral allergy?”

Cameron’s mouth quirks up at the corners; forgiven for staring, then, and forgiven for the abrupt subject change, too. “No,” she admits, “but it’s nice to be outside, don’t you think? The weather probably won’t last much longer.”

Chase, forever unimpressed by the sun thanks to the whole Australian thing, says, “S’alright.”

Cameron laughs, like she knows what he’s thinking. As she is often wont to do at his expense, and he finds he never really minds it as much as he tries to. “You can go in, if you want,” she offers, “I’m sure Laurel’s AC is working. The place is big enough you’ll probably lose Foreman forever.”

“God, I hope so,” Chase says without thinking; Cameron’s top lip quivers slightly, the way it always does when she thinks he’s being overly mean but can’t help but find it funny, and she’s developing two new freckles on the bridge of her nose, and instead of her usual lavender hand cream she smells like sunscreen and the base metal of sweat. Her whole face shines. “I can stay here,” Chase adds. “I like flowers, too.”

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 or so years in the future, doof and perry talk in a pool, at 3am, about the past. for about 5k words. that's it

[ on ao3 here ]

~

Even in dead of night, sounds rattle up the tower’s old iron skeleton to the top. The noise of the residents below, their talking and thumping and TV, warps through metal pipes and chutes into a muffled mechanical soundscape. The aging building’s life functions, thrumming from underfoot, as the fan wheels gently in the air above their bed.

Perry wakes in the room to Heinz’s absence.

Alone like this, he’s left with the many necessities of Heinz’s sleeping arrangement. The carefully selected quilt with the chunky stitching, the snuggly texture. Systematic obliteration of the wrong lights, the wrong sounds. All the particularities that Perry loves. And there are remnants: the old teddy retired to a decorative chair in the corner. The grind guard she doesn’t wear so much now, some little weight has lifted.

Perry squints at the Big Ben miniature on the bedside table to confirm the late hour, and gets up.

He finds her out on the balcony, crosslegged at the side of the pool. The moon’s out of view, but it lights the clouds up like seedpod puffs, and they mirror on the water, underlit by turquoise pool lights. The air is hot.

Perry goes over and places a hand on her bare knee, makes an asking sound.

“Just the usual, Perry,” Heinz says in reply. “I had a stupid dream.” She slides a foot out into the water, where it glows, white in blue. Perry sits at her side. “You were out of character.”

“You’re always uncharacteristically mean in my dreams,” she continues, half smiling. “And you talk. You talk way too often, I think that’s the worst part. In like whatever stupid voice my subconscious thinks you should have. Which changes. I think you sounded French one time, which makes no sense.”

The light is enough for Perry to sign by. What’d I say?

“Oh you know,” she says, her tone compressing. “You regretted this.”

Perry sits with that, with her, pressed against her leg. It’s not an accusation, Perry knows well enough by now, not one made in earnest. They both have to live with Heinz’s self-ravaging mind. He rubs her hand with his.

Hard to know what to regret. He’s put a lot of work in, building this life for himself. Like his boys used to build those miraculous one-day contraptions in the summertime, or Heinz would make reality-cracking machines fueled on coffee and malice, so Perry had built something of his own, more common and slow, but something he was happy with. This partnership with Heinz, this thick-knit network of people he’s living for.

It’s a struggle to even remember the days when he’d been workshopping its contruction. Hard to blueprint a machine, harder to blueprint a life lived in flux, tripwired with secrets and obligations. He used to sweat through nightmares, trying to see the shape of his future, seeing only how easily it could be lost.

Her sitting next to him on smooth cement, 3 AM, poolwater ringing her calf, the bright night sky. He can’t express to Heinz how he never imagined having this much.

So he gets up, with a parting squeeze of her hand, and backdives into the pool, a lazy arc piercing silent and smooth. Might as well give her something to watch. He skims along the bottom, where the LEDs cast sixfold yellow shadows, overlapping like insect wings as he goes.

A few minutes of trawling the circumference, twisting, shooting through the duck-shaped floaty ring, rocketing off the sides with strong pushes of his feet. He weaves and skips between water and air in sinoid leaps. He’s learned to oscillate his body like a seal for these jumps — it’s proved useful sampling the broader animal kingdom for swimming techniques. They keep him limber, in this low-gravity environment his body was made for.

He pops up to check on Heinz, who’s looking. “No no no, keep it up, Perry the Platypus,” she grins at him. “You’re like my Windows screensaver right now. It’s soothing. I dunno if it’s putting me to sleep though, if that’s what you were going for.”

Perry floats over to where she’s sitting. She’s stirring both legs through the water. They’re pencil-skinny and they spirograph ripples that lap into Perry’s neck.

“Y’know what I thought when I found out this place had a pool?” she asks him.

“Well — I thought I’d be doing so much water aerobics. I definitely didn’t think I’d have someone semiaquatic in my life. But that didn’t pan out, the aerobics. So later I thought I’d put in some electric eels or piranhas, for you when you’d visit. Keep it zesty. But I always thought of it right when the aquarium was closed. And you know, after that first spark of excitement has passed, an idea like that just ends up being on your list. So it never happened. You got lucky.”

Perry rests with an arm around her calf, underwater. She’s wearing one of her long hotweather nightshirts, millennial neon geometries advertising a dance camp that Vanessa once attended. It has glow in the dark squigglies. So many little things to keep Vanessa around, her never-worn hand-me-ups.

Perry darkens the shirt fabric in his wet fist, and tugs it toward him. Heinz laughs. “You are not getting me in there,” she says, pushing a foot at him. “I came out here to brood, not swim.”

Perry doesn’t accept it. He pulls her in successfully, and she drops off the edge into the pool without much fuss, splashing him. “This is of my own volition,” she says. “You don’t get to boss me around in the middle of the night. You don’t own me.”

Yes he does. Perry swims a ring around her waist, framing her. The light’s playing off her grey hair, staining it teal. In this view you could mistake them for a matching set. He likes that.

“That is literally still on a list somewhere,” Heinz adds, “the piranhas. In one of my old notebooks.”

They’re piled in storage now, the plans and the blueprints, though she keeps a few sitting around from the later years. A while back they cobbled together a scrapbook of the better schemes, Heinz’s more impressive drawings, fonder memories. Perry got the B.O.A.T. schematic professionally framed, one birthday. Heinz had rolled her eyes at it and hung it in the foyer.

“I feel weird looking at those,” Heinz says. “It’s like oh yeah, that idea was living in my head for years. Thought for sure that one was gonna put one over on Roger, as soon as I got around to it.”

Years, multiple? Really?

“Oh yeah,” says Heinz, as Perry blinks up in question. “You know how I procrastinate, Perry the Platypus. But it was mainly the big plans that I kept putting off, over and over. The ones that required a real surge of hatred, to kick my scheming into gear. Ambitious stuff, you know,” she says, tilting her head. “Mind control, intimidation — stuff that works. Not like the stuff I’d do with you, most days.”

She lilts an arm out, snaring Perry’s hand. He lets her pull him through the water in a curve.

“The bad ideas were more fun — I think I was just trying to give you a laugh, at a certain point. Not that you ever did. The chicken replaceinator, the beam that made people’s ties comically long. I did not think turning everyone’s shoes into heelys would actually win me dominion of the tristate area, Perry, if I’m being honest.

“All those big diabolical plans, they kept me up at night. But I put them off, ‘cause it was more fun getting sugar high with you and bouncing off the walls. Making up an entire song and dance number for the satisfaction of watching you try not to tap your foot to it. Every year it was: oh, just a few more months with Perry. Next year I’ll get serious, for sure.

“And, you know. I can’t regret any of it,” Heinz says. “Because it worked. I got you to dance with me, spend time with me. I didn’t think that was my goal at first — but you know, in retrospect, what else could possibly stack up?

“. . . But I didn’t get to know that, that my time was well spent, until later. Because you can’t really know if you’ll regret something when it’s happening. Like all those bad relationships, all those times I went into debt. You have to wait until you can look back on it all in a decade or two and go: oh yeah, that was a wash.”

Heinz pulls Perry out in a slow-motion twirl, bopping at the water’s surface. She gives him a considering look as their hands detach.

“That’s why I think about you. Because you haven’t been around as long. It takes time to figure out regret. And you don’t have the luxury,” she says with a tight smile, “of regretting a decade. You didn’t fuck up the 90s. You didn’t even have the opportunity.”

Perry can tell she’s got some spleen to vent. Potentially a whole rainbow of humors. He sets up on a paddleboard shaped like a ducky foot — perches zen-legged in its center, balancing what little weight he has. He comes up past her chin now.

“Do you know how many times I’ve invented time travel, Perry the Platypus?” Heinz asks.

“Well, once. When I was in my twenties. For a generous definition of ‘invent’ — we all learned the Onassian principles in college physics. It’s not too hard to plug in the missing variables — sort of an open secret, in the evil science world, how to manipulate time. We’d all dabble, here and there. You overstep and there’s consequences, of course. By the time you met me I was using it for trifles and whimsies. Hyperspecific stuff, that’s less of a risk.”

She fidgets shapes through the water with her hands.

“You remember me, like — summoning the Roman army. That sort of thing.”

Perry remembers it going wrong, yeah, and him sending Heinz back 800 years, in a perfunctory brush-off of that day’s scheme. He remembers finding Heinz back at DEI the next morning, in a sour mood, with a tirade prepared on the difficulties of refining metal ores in 13th century Mongolia. Heinz had lived there a month. Her age was now out of whack with the present date, and she had said something incomprehensible about it, like:

You’ve made me a Leo, Perry the Platypus. A Leo. That’s . . . well I’ve always felt like I should be one, deep down, so thank you. But it explains why horoscope advice has never worked out for me, which in hindsight is just plain embarrassing.

Perry doesn’t recall there being a scheme that day. Even with the freedom to bubble out extra time, Heinz hadn’t bothered prepping more than a long complaining story for Perry — adequate payback for the thwart, he supposed.

“But the first time I got it working,” Heinz continues. “I did some stuff I never even told you about.” She glances up at Perry. “I didn’t even make a plan, I just went back first thing. To Gimmelshtump. Wasn’t even dressed for the weather. And I saw myself there, walking around the outskirts of town. Carrying old breadloaves and rags, and whatever else — I had to be a packrat, back then.

“And I wasn’t even that far removed, at the time, from that kid. But he had a whole system worked out to survive. If you plunked me down in his haferlschuhs now I’d just collapse where he stood, in a matter of hours. Or I’d go crawling back to the ocelots — which wouldn’t end well, I don’t think they’d recognize me.”

Perry’s rather agog. What a length of time to hold this information inside. He realizes he’s perched unstably forward, off the foam board.

What did you do?

Heinz makes a dismissive noise. “What could I do? Nothing. Could I have stayed? Been a parent to that kid? I guess. At least until causality cried foul and wiped me out. But who wants to be a parent at 23?

“And it seems selfish, right, wanting to keep what I made myself into, at his expense. He had to suffer so I could sit warm and cozy in the 80s, failing out of American college because I was too smart for it, schtupping my way through town, selling bratwurst. But I am selfish, Perry the Platypus.” Heinz sets a hard look on him. “All I did was confirm to myself that it was real, all those awful things that happened to that kid. I wasn’t making it up. And I never went back.”

Perry stares at her — he’s sitting pensive on the board, cross-legged, and pushes himself an inch closer with his tail ruddered in the water.

I would’ve stayed, Perry responds, for that kid.

Heinz gives him a quizzical smile. “Would you? That’s easy to say. Would you live out the rest of your days helping him put his rumpkinhosen on the right way? Explaining puberty, that it’s not really the devil growing out of his body, like Mother says? Stealing him acne cream?”

Heinz’s face angles in a mean way.

“Are you gonna convince that kid his parents will never love him? Because that’s all that was keeping me there, apart from Roger. The dumb, burning hope that they might, eventually.”

Ok, so it’s a terrible idea. Perry nods anyway, to be contrary, cheek squished upon his fist.

You’d run away with any cute animal you met, he signs. And I’d kick their asses.

This repairs the mood somewhat, makes Heinz giggle in surprise.

“Oh would you?” she says behind long fingers, eyes sparkling. “Because I’d kind of like to see that. Grizzled platypus with a mysterious score to settle shows up, terrorizes my childhood home. Makes my parents beg for mercy.”

Perry nods. I’d treat you like a princess. Heinz can’t see that he’s blushing. She laughs, louder than before.

“Oh that’s cute, Perry. The Vanessa treatment! Wow. I would’ve turned out different, that’s for sure.” She’s trailing her fingertips across the pool tiles. “But going back in time, taking care of each other . . . let’s not, okay Perry the Platypus? Let’s not and say we would.”

But you did, Perry signs, because once he’s chimed into conversation with Heinz it’s hard to stop himself. Even when he realizes, too late, that he shouldn’t have said anything.

He drops his shaking hands to his lap. Heinz cocks her head with the same pretty smile, now thinner. “You’re gonna bring that up? When we learned how they got you? That . . . that was a mistake,” she says. “We were just getting to be friends, back then. It was exciting. I didn’t have my head on straight. ... And that would’ve been a different situation, in continuity terms, that was . . . ”

She opens and closes her mouth. Perry sees her stare fall to the water, thumb still tracing the putty grooves between the tiles.

“. . . I never really explained to you the technical nitty-gritty, the physics of it. There’s time-space transplantation, moving a body in its current state back or forward through time — that’s what I did going to Drusselstein. But there’s other ways to slide around.

“See, Roger was getting into golf — just excruciating, trying to spend any time with him, it was always ‘Pencil in a timeslot with Melanie and we’ll hit the back nine,’ or whatever.

“I found a way to fast-forward him, that I never got to use. Premature inator-destruction. It happens to the best of us. Usually to me, whenever you got too eager.”

Perry’s propped on his fist, contemplative. I wouldn’t know anything about that.

“See I think you would,” Heinz says, narrowing her eyes. “I’m pretty sure you were my caddie. In fact I’ve gleaned that most, if not all, of the platypuses I encountered in my evil heyday were you. That little guy had your eyes, and he looked unusually hot in golf shorts.”

Perry blinks, mouth trained in a line.

“C’mon, Perry the Platypus,” she wheedles. “It’s not nice leaving a girl in limbo, for so many years. This’ll keep weighing on me.”

Okay fine, Perry signs, shrugging. I was the hot caddie.

“I knew it!” She grabs the foam board and shoves it hard, sending Perry backwards with a splash. “You are such a jerk gaslighting me all the time! Steven.”

Perry shakes water off his bill and punches forward into her, though the effect is more of a cuddle. She tangles him in her arms.

“So that means you know,” she says, scrunching fingers into his chest, “why I wanted to speed through that. And if you can isolate a body, move it forward and back, you can isolate a mind, or a consciousness.

“That was the technique I used, for when . . . you know, when I did the.” She falters. “Really, really bad idea.”

Except you didn’t, Perry signs up at her.

“Yeah, but like. I think about it. How I almost did. How I could’ve screwed everything up. For both of us.”

Perry remembers it more through her recollection than anything. The day she’d cracked into the OWCA admin portal and Perry had let her. The day she found the timestamped geolocation from which Perry had been acquired. He remembers Heinz’s outrage, mourning Perry’s fate at OWCA’s hands, and the wave of giddy revelation that had quickly taken over at the chance to go back, intercede, take Perry for herself instead.

From where Perry had stood Heinz hadn’t vanished, hadn’t even blipped. He just knew that one instant he was rocketing a punch toward someone diabolically driven and the next, post-inator, was socking his fists into the braced forearms of a downed Heinz, cowed under Perry on the lab floor. And Heinz’s eyes had been so haunted, looking up at him from behind those arms, that Perry knew something had passed.

It was years before she’d tell him the full story. How she’d run out of the house as her 41-year-old self, to track Perry down. The bluegreen and red at the riverside. How Perry’s mother had died on the shore, bleeding out of bite wounds, accepting Heinz’s touch as she cooled under frantic hands. The last look she’d given Heinz. The wariness of the OWCA-trained animal control agents who’d found Heinz sitting there, keeping vigil. How Perry had nestled in the palm of her hand, impossibly little, and ate up what milk of his mother Heinz brought to his bill, fingertip to mouth.

He can’t remember any of it, of course, how could he. But he would always carry close to heart the knowledge that Heinz had inserted herself, in this small and careful way. Had been the first human touch he’d felt.

But it made Heinz cry, retelling it. So Perry never brings it up.

He holds the back of her hand, as she winds a thumb through his fur.

“It would’ve been so easy to change what you were to me, and ruin the weird thing we had with each other — even back then, when it didn’t seem like as much. I didn’t know at the time, y’know, that you’d want to stick around this long.”

Perry gives her a sad smile.

“Time travel’s the worst, it’s like an automatic culpability machine,” Heinz says. “It’s a terrible idea to go backward: everything becomes your choice. Any pain in the past is now stamped with your approval, you don’t have the right to complain anymore. Choosing to leave you with Monogram, choosing to abandon myself in Gimmelshtump. It’s so easy to change everything, with a few key edits.

“And greed always makes me want both. I wanna give that lonely little kid a charmed life, and I want to keep the one I have. I want to get to raise you into my perfect little companion,” she says, cuffing the back of his neck. “And I want to get to fuck you, too.”