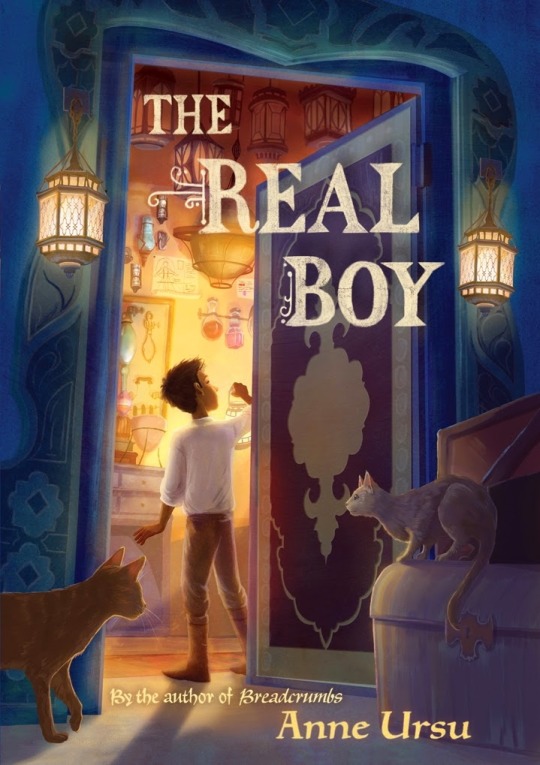

#The Real Boy by Anne Ursu

Text

the real boy by anne ursu is fucking fantastic finally someone is daring to ask ‘what if pinocchio was so so autistic’

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Real Boy by Anne Ursu

Genre/category: Disability/Difference, National Book Award Nominee, Fantasy, Novel

Targeted Age: 3rd to 6th graders

Quick plot synopsis: Oscar works as a hand in the shop of the last magician in Aletheia. He’s happiest in his small room, working with herbs behind the scenes, but one day he’s forced to run the shop all alone. Aletheia is changing— a monster is in the forest, children are getting sick, and Oscar must make sacrifices to save the world as he knows it.

Why I chose The Real Boy: The Real Boy is listed on Disability in Kidlit’s Honor Roll. Oscar, while never explicitly referred to as autistic, has clear signs of autism. Ursu’s novel is told from Oscar’s perspective and is an accurate representation of an autistic character. Additionally, The Real Boy was a National Book Award Nominee. Illustrations and setting map by Erin McGuire appear on a few pages, each accompanying the scenes they depict.

Evaluation:

Oscar is the definitive focus of The Real Boy. The novel is told entirely from his third person perspective. The reader experiences the magic and conflict of the world through his interactions and interpretations of them. By focusing on Oscar’s perspective, his differences are portrayed in the way he experiences them. This avoids the sense of othering present in many other books with autistic characters. The only indication that Oscar is “odd” comes from the reactions other characters have to him. Oscar’s behavior is normal to him, and through the third person limited perspective, it’s normalized to the reader as well. Rather than treating him like a specimen, The Real Boy treats Oscar as a fully realized human being, a real boy.

Ursu’s primary characters in The Real Boy are well-rounded and dynamic. Over the course of the story, Oscar is changed by his ever-evolving situation. He develops a strong friendship with the healer’s apprentice, Callie, who also grows over the course of the novel. The pair assist each other with things they need to survive— Callie helps Oscar interact with his shop’s customers and Oscar helps Callie learn about herbs and remedies. One thing I appreciated about The Real Boy is that the plot does not focus on “curing” Oscar of autism. His character growth is not aimed at changing autism, but rather at his developing friendships and desire to protect others. His autism is part of his character, but not all of it.

The Real Boy has very quick pacing of events for Oscar, but I felt that the pacing of the mystery was somewhat slow. At times, it seems like poor Oscar can’t catch a break. Tragedy strikes the magician’s shop more than once, leaving him all alone to deal with belligerent customers. He hardly has any time to recover from some of these obstacles. But, he always has his beloved cats and friend Callie to rely on. For the mystery of the attacks on the Barrow village and the sickness of the City children, not much progress is made toward the solution until the latter half of the book. However, when Oscar and Callie find their solution and life starts to return to balance, the relief in the story is palpable. Perhaps the constant turmoil Oscar faced makes the ending of the novel even sweeter.

Do I recommend it?: Yes! The Real Boy is a loving portrayal of an autistic boy in a fantasy setting. Readers of all ages will love to read about his adventures and dealings with magic.

Citations:

Duyvis, C. (2015, April 13). Review: The Real Boy by Anne Ursu. Disability in Kidlit. https://disabilityinkidlit.com/2015/04/13/review-the-real-boy-by-anne-ursu/

Ursu, A. (2013). The Real Boy (E. McGuire, Illus.). Walden Pond Press.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2019 reads: The Real Boy

The Real Boy by Anne Ursu. Walden Pond Press, 2013, 348 pages.

Oscar is a boy who struggles to communicate with other people, and prefers to stick to his small, contained world at the back of his magician caretaker’s shop, but a series of strange incidents takes him out of his comfort zone and has him questioning everything he knows. A really interesting take on Pinocchio with an environmentalist theme.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think are the top five YA and MG books to study for craft (fiction not non-fiction)?

Being that I am not a writer, I don't STUDY books... I just read them!

So I asked some of my brilliant clients who also TEACH writing to ask THEM this question and I got the following responses:

Jo Knowles says: "Usually when I suggest books to a student, it's after they tell me about the kind of book they hope to write, and I've seen their writing and have had time to think about "what's missing" from it, at least for me. Usually that's emotion. Or connection. Often their characters just don't feel "real" yet. So I end up usually recommending books that moved me deeply, or inspired me in some way, hoping it does the same for them. I give a huge range and try to make it as diverse as I can.

I AM THE MESSENGER is always on that list. Mainly because it can be looked at for so many of those perfect things, AND because it's almost a collection of short stories, as the MC tries to address each family/person he's meant to help in some way. They are all so moving and real to me. I also love recommending TENDER MORSELS because it deals with trauma in such a profound way, and can show students how powerful this sort of "fantasy" (I really hesitate to call it that), can be. But it really depends on the genre they are writing in. If realistic, that's one thing, if sci fi, another. So I don't know that I would have a top five. But for students writing memoir or biofiction, I usually recommend THE WATSONS GO TO BIRMINGHAM and BROWN GIRL DREAMING and FUN HOME and STITCHES. If something with fantasy, I would definitely include THE GRAVEYARD BOOK and TITHE. And if historical, anything by MT Anderson and also Christopher Paul Curtis. There are just so many more! But I really wouldn't just give a random list because one size doesn't fit all and I'd want to get to know the person, what their likes and dislikes are, and what they are aiming for themselves before I'd make a recommendation."

Martha Brockenbrough says: "Yes! What Jo says. I don’t rank books by best of, because that’s a lot of energy over something uselessly subjective. Instead, I think about the aspects of craft that matter most when it comes to determining excellence:

character

plot

setting

structure

point of view

voice

theme

To be excellent, a book really ought to be doing all of these things at a masterful level. But there’s probably one or two of those areas that will shine.

So, I love the characters and voice of Jaclyn Moriarty’s Ashbury/Brookfield series. She does multiple POV and even crosses genres with these books.

Holly Black is absolutely KILLER for plot, and the Curseworkers series are superb. The intersection of plot/POV is extraordinary in Elizabeth Wein’s Code Name Verity.

For structure, LONG WAY DOWN is a book about an elevator ride and it is an elevator ride. He of course is one of the finest writers ever, as well. But I do love a structure that underscore the theme.

In every category, Rita Williams Garcia’s A SITTING IN ST JAMES is an absolute work of art.

But I do think Jo’s insight—find a book that does what you want your book to do—is key when you’re trying to write a certain kind of book. Any excellent book can show you remarkable craft, and one key to recognizing it is to note a spot in the book that makes you feel a particular emotion. When you feel something, then you analyze every word and preceding scene to understand what techniques evoked that important emotion.

That’s why we read. To feel something. How do authors do this? Well, that is a very long story..."

Linda Urban says: "Agree with Martha and Jo. My recommendations for mentor texts are usually specific to my students' needs or challenges -- what book makes you feel like you know the character in the same way that you want readers to feel they know YOUR character? What book moves time the way you want your book to move time? What plot twist surprised you in the way you want your plot to suprise readers?

That said, I have go-to books where I think the craft is stellar and also easy to discern. I use the first chapter of Jason Reynold's GHOST a lot for students who want to figure out how to establish character and stakes in from the get-go. I love SEE YOU AT HARRY'S for emotional whollop and unexpected plot twists (that are still within the realm of realism). I like Anne Ursu's THE REAL BOY for omniscient narrator . . . etc. etc. etc.

The point is, read a lot -- read books that feel like they do what you most want to do, like they'd be great neighbors on a bookshelf (even if they are for different age readers or different genres or forms) and learn from them."

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

On The Grinning Man and the De-Politicization of L'Homme Qui Rit (a Spontaneous Essay)

Since I watched The Grinning Man I’ve been meaning to write a post comparing it to The Man Who Laughs but I have a lot of opinions and analysis I wanted to do so I have been putting it off for ages. So here goes! If I were to make a post where I explain everything the musical changes it would definitely go over the word limit, so I’ll mostly stick to the thematic. Let me know if that’s a post you’d like to see, though!

Ultimately, The Grinning Man isn’t really an adaptation of the Man Who Laughs. It keeps some of the major plot beats (a disfigured young man with a mysterious past raised by a man and his wolf to perform to make a living alongside the blind girl he rescued from the snow, restored to his aristocratic past by chance after their show is seen by Lord David and Duchess Josiana, and the interference of the scheming Barkilphedro…. well, that’s just about it). The problem I had with the show, however, wasn’t the plot points not syncing up, it was the thematic inconsistency with the book. By replacing the book’s antagonistic act—the existence of a privileged ruling class—with the actions of one or two individuals from the lower class, transforming the societal tragedy into a revenge plot, and reducing the pain of dehumanization and abuse to the pain of a physical wound, The Grinning Man is a sanitized, thematically weak failure to adapt The Man Who Laughs.

I think the main change is related to the reason I posit the book never made it in the English-speaking world. The musical was made in England, the setting of the book which was so critical of its monarchy, it’s aristocracy, and the failings of its society in ways that really haven’t been remedied so far. It might be a bit of a jump to assume this is connected, but I have evidence. They refer to it as a place somewhat like our own, but change King James to King Clarence, and Queen Anne to Angelica. Obviously, the events of the book are fictional, and it was a weird move for Hugo to implicate real historical figures as responsible for the torture of a child, but it clearly served a purpose in his political criticism that the creative team made a choice to erase. They didn’t just change the names, though, they replaced the responsibility completely. In the book, Gwynplaine’s disfigurement—I will be referring to him as Gwynplaine because I think the musical calling him Grinpayne was an incredibly stupid and cruel choice—was done to him very deliberately, with malice aforethought, at the order of the king. The king represents the oppression of the privileged, and having the fault be all Barkilphédro loses a lot thematically. The antagonism of the rich is replaced by the cruelty of an upwardly mobile poor man (Barkilphédro), and the complicity of another poor man.

The other “villain” of the original story is the way that Gwynplaine is treated. I think for 1869, this was a very ahead-of-its-time approach to disability, which almost resembles the contemporary understanding of the Social Model of disability. (Sidenote: I can’t argue on Déa’s behalf. Hugo really dropped the ball with her. I’m going to take a moment to shout out the musical for the strength and agency they gave Déa.) The way the public treats Gwynplaine was kind of absent from the show. I thought it was a very interesting and potentially good choice to have the audience enter the role of Gwynplaine’s audience (the first they see of him is onstage, performing as the Grinning Man) rather than the role of the reader (where we first see him as a child, fleeing a storm). If done right, this could have explored the story’s theme of our tendency to place our empathy on hold in order to be distracted and feel good, eventually returning to critique the audience’s complicity in Gwynplaine’s treatment. However, since Grinpayne’s suffering is primarily based in the angst caused by his missing past and the physical pain of his wound (long-healed into a network of scars in the book) [a quick side-note: I think it was refreshing to see chronic pain appear in media, you almost never see that, but I wish it wasn’t in place of the depth of the original story], the audience does not have to confront their role in his pain. They hardly play one. Instead, it is Barkilphédro, the singular villain, who is responsible for Grinpayne’s suffering. Absolving the audience and the systems of power which put us comfortably in our seats to watch the show of pain and misery by relegating responsibility to one character, the audience gets to go home feeling good.

If you want to stretch, the villain of the Grinning Man could be two people and not one. It doesn’t really matter, since it still comes back to individual fault, not even the individual fault of a person of high status, but one or two poor people. Musical!Ursus is an infinitely shittier person than his literary counterpart. In the book, Gwynplaine is still forced to perform spectacles that show off his appearance, but they’re a lot less personal and a lot less retraumatizing. In the musical, they randomly decided that not only would the role of the rich in the suffering of the poor be minimized, but also it would be poor people that hurt Grinpayne the most. Musical!Ursus idly allows a boy to be mutilated and then takes him in and forces him to perform a sanitized version of his own trauma while trying to convince him that he just needs to move on. In the book, he is much kinder. Their show, Chaos Vanquished, also allows him to show off as an acrobat and a singer, along with Déa, whose blindness isn’t exploited for the show at all. He performs because he needs to for them all to survive. He lives a complex life like real people do, of misery and joy. He’s not obsessed with “descanting on his own deformity” (dark shoutout to William Shakespeare for that little…infuriating line from Richard III), but rather thoughtfully aware of what it means. He deeply feels the reality of how he is seen and treated. Gwynplaine understands that he was hurt by the people who discarded him for looking different and for being poor, and he fucking goes off about it in the Parliament Confrontation scene (more to come on this). It is not a lesson he has to learn but a lesson he has to teach.

Grinpayne, on the other hand, spends his days in agony over his inability to recall who disfigured him, and his burning need to seek revenge. To me, this feels more than a little reminiscent of the trope of the Search for a Cure which is so pervasive in media portrayals of disability, in which disabled characters are able to think of nothing but how terribly wrong their lives went upon becoming disabled and plan out how they might rectify this. Grinpayne wants to avenge his mutilation. Gwynplaine wants to fix society. Sure, he decides to take the high road and not do this, and his learning is a valuable part of the musical’s story, but I think there’s something so awesome about how the book shows a disabled man who understands his life better than any abled mentor-philosophers who try to tell him how to feel. Nor is Gwynplaine fixed by Déa or vice versa, they merely find solace and strength in each other’s company and solidarity. The musical uses a lot of language about love making their bodies whole which feels off-base to me.

I must also note how deeply subversive the book was for making him actually happy: despite the pain he feels, he is able to enjoy his life in the company and solidarity he finds with Déa and takes pride in his ability to provide for her. The assumption that he should want to change his lot in life is not only directly addressed, but also stated outright as a failure of the audience: “You may think that had the offer been made to him to remove his deformity he would have grasped at it. Yet he would have refused it emphatically…Without his rictus… Déa would perhaps not have had bread every day”

He has a found family that he loves and that loves him. I thought having him come from a loving ~Noble~ family that meant more to him than Ursus did rather than having Ursus, a poor old man, be the most he had of a family in all his memory and having Déa end up being Ursus’ biological daughter really undercut the found family aspect of the book in a disappointing way.

Most important to me was the fundamental change that came from the removal of the Parliament Confrontation scene, on both the themes of the show and the character of Gwynplaine. When Gwyn’s heritage is revealed and his peerage is restored to him, he gets the opportunity to confront society’s problems in the House of Parliament. When Gwynplaine arrives in the House of Parliament, the Peers of England are voting on what inordinate sum to allow as income to the husband of the Queen. The Peers expect any patriotic member of their ranks to blithely agree to this vote: in essence, it is a courtesy. Having grown up in extreme poverty, Gwynplaine is outraged by the pettiness of this vote and votes no. The Peers, shocked by this transgression, allow him to take the stand and explain himself. In this scene, Gwynplaine brilliantly and profoundly confronts the evils of society. He shows the Peers their own shame, recounting how in his darkest times a “pauper nourished him” while a “king mutilated him.” Even though he says nothing remotely funny, he is received with howling laughter. This scene does a really good job framing disability as a problem of a corrupt, compassionless society rather than something wrong with the disabled individual (again, see the Social Model of disability, which is obviously flawed, but does a good job recognizing society that denies access, understanding and compassion—the kind not built on pity—as a central problem faced by disabled communities). It is the central moment of Hugo’s story thematically, which calls out the injustices in a system and forces the reader to reckon with it.

It is so radical and interesting and full that Gwynplaine is as brilliant and aware as he is. He sees himself as a part of a system of cruelty and seeks justice for it. He is an empathic, sharp-minded person who seeks to make things better not just for himself and his family, but for all who suffer as he did at the hands of Kings. Grinpayne’s rallying cry is “I will find and kill the man who crucified my face.” He later gets wise to the nature of life and abandons this, but in that he never actually gets to control his own relationship to his life. When I took a class about disability in the media one of the things that seemed to stand out to me most is that disabled people should be treated as the experts on their own experiences, which Gwynplaine is. Again, for a book written in 1869 that is radical. Grinpayne is soothed into understanding by the memory of his (rich) mother’s kindness.

I’ll give one more point of credit. I loved that there was a happy ending. But maybe that’s just me. The cast was stellar, and the puppetry was magnificent. I wanted to like the show so badly, but I just couldn’t get behind what it did to the story I loved.

#the grinning man#the man who laughs#tgm musical#l'homme qui rit#victor hugo#gwynplaine's parliament rambles#long post /

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illustration by Erin McGuire for the book "The Real Boy" by Anne Ursu

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On being a “crybaby”

@art-felt // unknown // The River by AURORA // Patricia Highsmith, Carol // @scarletrougelipstick // Eyeball from Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent of Christ from the Cross // 'The Real Boy’ by Anne Ursu // @venuskissed // Åsa Larsson, Sun Storm // Spirited Away by Studio Ghibli

Feel free to add your own parts or sumbit them!

#web weaving#crying#parallels#comparasion#compilation#feelings#poetry#literature#typography#yall im a crybaby#this is more rushed than id like but i rlly had an urge to make it#my textrinum#theme: crying#btw i love aurora aksnes with all my heart

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Star Wars: The Clone Wars – Stories of Light and Dark, coming August 25, promises to be a beautiful tribute to the just-completed animated series. The anthology will collect 11 stories by 11 authors — Lou Anders, Preeti Chhibber, Zoraida Córdova, Jason Fry, Rebecca Roanhorse, Greg Van Eekhout, Tom Angleberger, E. Anne Convery, Sarah Beth Durst, Yoon Ha Lee, and Anne Ursu — including 10 retellings of memorable episodes and arcs and one original Nightsisters-based story. So if you loved the tales of Ahsoka, Maul, and clanker-busting clones, Star Wars: The Clone Wars – Stories of Light and Dark will give you the chance to experience them again in a whole new way. Like Captain Rex on a recon mission, StarWars.com reached out to each author to learn why they love The Clone Wars, and which stories they’re telling.

Lou Anders (“Dooku Captured” and “The Gungan General,” based on the episodes of the same name): I love The Clone Wars for expanding the story of Anakin’s fall from grace. Skywalker really shines in the series, and we see what he truly was, and what he could have been, and by giving him so many opportunities to excel in the early season, his ultimate fate is that much more tragic. I also love the series for gifting us my all-time favorite Star Wars character, and one of my favorite characters from any universe — Hondo Ohnaka!

My chapter is a retelling of the first season story arc that plays out across the episodes “Dooku Captured” and “The Gungan General.” I wanted to explore this storyline because I find Count Dooku a fascinating character. Sometimes pure, mustache-twirling, mwa-ha-ha evil can actually be boring to write, but a villain who feels they are justified, either because of perceived slights or intellectual superiority or the failure of their rivals or birthright are much more interesting, and Dooku is a bit of all of this. For research, I obviously watched tons of Clone Wars. But I also read up on everything about Dooku I could find, and I listened to Christopher Lee and Corey Burton’s interpretation of the character over and over, trying to internalize their speech patterns. Dooku is so gorgeously supercilious. It was just a blast to get in his head and see the world from his perspective. (And the fact that the storyline gave me another chance to write for my beloved Hondo Ohnaka was an added bonus!)

Tom Angleberger (“Bane’s Story,” based on the episodes “Deception,” “Friends and Enemies,” “The Box,” and “Crisis on Naboo”): There’s a lot to love in The Clone Wars, but I think it’s Ahsoka’s arc that really stands out the most. Ventress’s arc does, too, and the way that these arcs cross at the just the right moment is really great Star Wars!

My chapter is based on the “Crisis on Naboo” story arc. It’s basically a Space Western. The baddest bounty hunter of them all, Cad Bane, is hired to kidnap the Chancellor. What he doesn’t know is that almost everyone is lying to him, especially a fellow bounty hunter who is really Obi-Wan in disguise. In the TV version, we see it all from Obi-Wan’s point of view, so we know that Bane is getting played. In this retelling, we see it all from Bane’s point of view and, boy, is he going to be mad! To prepare I watched both The Clone Wars AND old spaghetti Westerns starring Bane’s inspiration: Lee Van Cleef.

Preeti Chhibber (“Hostage Crisis,” based on the episode of the same name): I love the story that the prequels tell, but because of the nature of what they were trying to do — tell a decade and a half worth of story in three films — we’re missing major moments in what the war really means to the galaxy at large, and in the Skywalker saga itself. The Clone Wars tells us that part of the narrative, it gives us the shape of what entire populations of people had to go through because of this war manufactured by the ultimate evil. And within that scope gives us the hope and love and beautiful tragedy we associate with Star Wars on a larger scale. (Also, Ahsoka Tano — The Clone Wars gave us Ahsoka Tano and for that I will be ever grateful.)

I’m writing Anakin’s story during “Hostage Crisis” — an episode in the first season of The Clone Wars. I decided to write the story entirely from Anakin’s perspective, which meant being inside his head before the fall, but where we are starting to see more of the warning signs. And then there’s also the romance of this episode! Anakin’s love for Padmé is real and all-consuming and, as we eventually find out, unhealthy. So, this is a romantic episode, but one that shows us Anakin is ruled by his heart. And that that’s a dangerous thing for a Jedi. In order to best wrap my own head around what was going on, I watched the episode itself several times, and read the script, and then I watched the chronological episodes of Anakin’s run-ins with Cad Bane, so I could get a real feel for where he was with his understanding of Bane’s character.

E. Anne Convery (“Bug,” based on the episode “Massacre”): I love it because I think it’s a story that manages, while still being a satisfying adventure, to not glorify war. It does this mainly by following through on the arcs of wonderful, terrifying, funny, fallible, and diverse characters. From the personal to the political, The Clone Warsredefines the ways, big and small, that we can be heroes.

My chapter is the “original” tale, though it still touches on The Clone Wars Season Four episode “Massacre,” with brief appearances by Mother Talzin and Old Daka. If I had to boil it down, I’d say that it’s a story about mothers and daughters. Honestly, it felt a little like cheating, because writing new characters meant I got to be creative in the Star Wars universe somewhat unencumbered by what’s come before. I did, however, have several long text chats with Sam Witwer because I was interested in Talzin’s motivations. We talked about stuff like her capacity (or lack thereof) for love. I think I came away thinking she was more a creature driven by issues of power, control, and the desire for revenge, whereas Sam was a little kinder to her. I mean, he is her “son,” so you can’t really blame him for wanting to think better of her! I always love a story within a story, and I was interested in the space where the high mythology of Star Wars and the home-spun mythology of fairy tales could intersect. I drew on my own background in mythology, psychology, and the language of fairy tales, plus I did my Star Wars research. Re-watching the Nightsisters episodes was just plain fun.

Zoraida Córdova (“The Lost Nightsister,” based on the episode “Bounty”): The Clone Wars deepens the characters we already love. It gives us the opportunity to explore the galaxy over a longer period of time and see the fight between the light and the dark side. Star Wars is about family, love, and hope. It’s also incredibly funny and that’s something that The Clone Wars does spectacularly. We also get to spend more time with characters we only see for a little bit in the movies like Boba Fett, Bossk, Darth Maul!

My chapter follows Ventress after she’s experienced a brutal defeat. Spoiler alert: she’s witnessed the death of her sisters. Now she’s on Tatooine and in a rut. She gets mixed up with a bounty hunter crew led by Boba Fett. Ventress’s story is about how she goes from being lost to remembering how badass she is. I watched several episodes with her in it, but I watched “Bounty” about 50 times.

Sarah Beth Durst (“Almost a Jedi,” based on the episode “A Necessary Bond”): I spent a large chunk of my childhood pretending I was training to become a Jedi Knight, even though I’d never seen a girl with a lightsaber before. And then The Clone Wars came along and gave me Ahsoka with not one but TWO lightsabers, as well as a role in the story that broadened and deepened the tale of Anakin’s fall and the fall of the Jedi. So I jumped at the chance to write about her for this anthology.

In my story, I wrote about Ahsoka Tano from the point of view of Katooni, one of the Jedi younglings who Ahsoka escorts on a quest to assemble their first lightsabers, and it was one of the most fun writing experiences I’ve ever had! I watched the episode, “A Necessary Bond,” over and over, frame by frame, studying the characters and trying to imagine the world, the events, and Ahsoka herself through Katooni’s eyes. The episode shows you the story; I wanted to show you what it feels like to be inside the story.

Greg van Eekhout (“Kenobi’s Shadow,” based on the episode “The Lawless”): What I most love about Clone Wars is how we really get to know the characters deeply and see them grow and change.

I enjoyed writing a couple of short scenes between Obi-Wan and Anakin that weren’t in the episode. I wanted to highlight their closeness as friends and show that Anakin’s not the only Jedi who struggles with the dark side. There’s a crucial moment in my story when Obi-Wan is close to giving into his anger and has to make a choice: Strike out in violence or rise above it. It’s always fun to push characters to extremes and see how they react.

Jason Fry (“Sharing the Same Face,” based on the episode “Ambush”): I love The Clone Wars because it made already beloved characters even richer and deepened the fascinating lore around the Jedi and the Force.

I chose Yoda and the clones because the moment where Yoda rejects the idea that they’re all identical was one of the first moments in the show where I sat upright and said to myself, “Something amazing is happening here.” You get the entire tragedy of the Clone Wars right in that one quick exchange — the unwise bargain the Jedi have struck, Yoda’s compassion for the soldiers and insistence that they have worth, the clones’ gratitude for that, and how that gratitude is undercut by their powerlessness to avoid the fate that’s been literally hard-wired into them. Plus, though I’ve written a lot of Star Wars tales, I’d never had the chance to get inside Yoda’s head. That had been on my bucket list!

Yoon Ha Lee (“The Shadow of Umbara,” based on the episodes “Darkness on Umbara,” “The General,” “Plan of Dissent,” and “Carnage of Krell”): I remember the first time I watched the “Umbara arc” — I was shocked that a war story this emotionally devastating was aired on a kids’ show. But then, kids deserve heartfelt, emotionally devastating stories, too. It was a pleasure to revisit the episodes and figure out how to retell them from Rex’s viewpoint in a compact way. I have so much respect for the original episodes’ writer, Matt Michnovetz — I felt like a butcher myself taking apart the work like this!

Rebecca Roanhorse (“Dark Vengeance,” based on the episode “Brothers”): I always love a backstory and Clone Wars was the backstory that then became a rich and exciting story all its own. The writing and character development is outstanding and really sucks you into the world.

I chose to write the two chapters that reintroduce Darth Maul to the world. We find him broken and mentally unstable, not knowing his own name but obsessed with revenge against Obi-Wan and we get to see him rebuild himself into a cruel, calculating, and brilliant villain. It was so much fun to write and I hope readers enjoy it.

Anne Ursu (“Pursuit of Peace,” based on the episode “Heroes on Both Sides”): The Clone Wars creates a space for terrific character development. The attention paid to the relationships between Anakin and Obi-Wan, and Anakin and Ahsoka make for really wonderful and resonant stories, and give so much depth to the whole universe.

I was at first a little scared to write Padmé, as her character felt pretty two dimensional to me. But the more I watched her episodes in Clone Wars, the more dimension she took on. She’s such an interesting character — she’s both idealistic and realistic, so when corruption runs rampant in the Senate she doesn’t get disillusioned, she just fights harder. She has an ability to deal with nuance in a way that is rare in the Republic — and it means she’s not afraid to bend a few laws to make things right. In this chapter, the Senate is about to deregulate the banks in order to fund more troops, and Padmé decides to take matters into her own hand and sneak into Separatist territory in order to start peace negotiations. Of course, neither Dooku nor the corrupt clans of the Republic are going to allow for this to happen, so the threats to the peace process, the Republic, and Padmé’s life only grow. This arc is the perfect distillation of Padmé’s character, and it made getting into her head for it fairly simple. But I did watch all the Padmé Clone Wars episodes and read E.K. Johnston’s book about her, as well as Thrawn: Alliances, in which she has a major storyline. I really loved writing her.

Star Wars: The Clone Wars – Stories of Light and Dark arrives August 25 and is available for pre-order now.

#obi wan kenobi#anakin skywalker#padme amidala#asajj ventress#ahsoka tano#katooni#yoda#captain rex#darth maul#novels#news#long post

351 notes

·

View notes

Note

RORY. 5 9 11 YOUR HONOR I LOVE HIM.

What is your favorite thing to do in your free time?

[insert sexual joke here] "These days I don't find myself doing much. I've recently started working out more, just to pass the time~"

Are you a spiritual person? If yes, what do you practice?

"Not really, no. I'm open to it, It's just not the first (or fifth) thing on my mind."

What is your favorite type of media (TV, movie, books, etc)? Name some specific favorites (which shows, movies, books, etc do you like)!

"I like books... Specific? oh,, It's a little stupid but my favorite book is The Real Boy by Anne Ursu... Yes, I know it's a children's book~ Don't tease me I'll cry (said jokingly)!"

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Books suggestions for ages 12-13+, that are not of dubious content?

I don’t know if your definition of dubious is the same as mine but here are some books I consider appropriate for middle school kids:

First, some classics, which are maybe a bit obvious but bear repeating:

The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Chronicles of Narnia, by C.S. Lewis

The Sword in the Stone, by T.H. White

My Side of the Mountain, by Jean Craighead George

The Giver, by Lois Lowry (and its sequels)

The Shadow Children series, by Margaret Peterson Haddix

Holes, by Louis Sachar

Johnny Tremain, by Esther Forbes

Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain

Little House on the Prairie, by Laura Ingalls Wilder

A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L’Engle

And then some that are maybe less commonly recommended but which I like:

The Real Boy, by Anne Ursu

Crossbows and Crucifixes, by Henry Garnett

The Wingfeather Saga, by Andrew Peterson

Show Me a Sign, by Ann Clare LeZotte

So B. It, by Sarah Weeks

The Door in the Wall, by Marguerite de Angeli

The Shakespeare Stealer, by Gary Blackwood

Where the Lilies Bloom, by Vera and Bill Cleaver

A Night Divided, by Jennifer A. Nielsen

The Locket’s Secret, by K. Kelley Heyne

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Ursu's The Troubled Girls of Dragomir Academy is brilliant!

Anne Ursu's The Troubled Girls of Dragomir Academy is brilliant! @WaldenPondPress @anneursu

The Troubled Girls of Dragomir Academy, by Anne Ursu, (Oct. 2021, Walden Pond Press), $17.99, ISBN: 9780062275127

Ages 9-13

Anne Ursu is an undisputed champion of kidlit fantasy. I’ve devoured The Real Boy and Breadcrumbs and am in awe of how she creates these incredible worlds with characters that are so realistic, so well-written, that looking up and realizing I’m still in my living room, dog…

View On WordPress

#Anne Ursu#fantasy#HarperCollins Children&039;s#magic#siblings#The Troubled Girls of Dragomir Academy#Walden Pond Press

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

yes. pick one. this is me bullying you into picking just one book as your favourite this year.

“oh huh an inbox notif, I wonder what’s--ASKSHFHL BLUE”

you’re getting categories, that’s the best I can do, okay, I didn’t read as much as you did this year but I did read a bunch and I am VERY indecisive

book that most fundamentally shifted how I think about and interact with my environment: Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

book I most wish I had been able to read as a kid: The Real Boy by Anne Ursu

book I've thought about the most since reading it: Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

book that felt most like it was written to directly target my interests: Iseul's Lexicon by Yoon Ha Lee (which is technically a novella contained in Conservation of Shadows but shhh) (you would like this one I think!! it has language and spies and magic and it’s largely about linguistic imperialism)

favorite poetry collection: The Gospel of Breaking by Jillian Christmas

special mention because I just finished it so I’m still processing it and I don’t know what category it gets but I loved it so I really want to mention it: Elatsoe by Darcie Little Badger

special mention to my favorite short story, "The Homunculi’s Guide to Resurrecting Your Loved One From Their Electronic Ghosts" by Kara Lee, which tenderly and with great care eviscerated me

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I last read...

‘The real boy’ by Anne Ursu

what I wanted: this was on some kind of list here on tumblr and sounded interesting

what I got: an imaginative, if tangled tale

what I thought: The characters and setting have left a very vivid impression and a feeling of both cozy and dangerous magic and the adventure it leads to. However, the story got more and more convoluted and kind of seemed to have lost its read thread after a while. Maybe it was trying to do too many things or maybe where it wanted to end up was introduced too late, but whatever it was I found that I was taken out of the story at times. Nevertheless, this story is imaginative and curious and I rate it 3 out of 5 may bells to sue in a concoction.

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

God bless this book

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I saw your autistic headcanon for Howl in the Diana Wynne Jones tag, and figured that if you don't already know about it, I should mention that Cat Chant from the Chrestomanci Chronicles has been confirmed autistic by DWJ herself. In case you want more autistic DWJ characters. (Not instead of Howl, but in addition to Howl.)

On the one hand I’m very happy to hear that (and I suppose that means I’m now legally required to give Charmed Life a second chance after dropping it the first time) and it’s very cool that she confirmed that, because Cat is a wonderful character and I really do love him!

On the other hand

I’ve read that you’ve said Cat Chant [a recurring central character in the Chrestomanci books] is slightly autistic. Can you talk a little about that?

Well, you know he has very great difficulty telling people things. It’s a mild form of autism. He’s not completely turned in on himself, but he is rather. This is how autism seems to be. I mean the worst cases. The child is almost unapproachable by other people. But in the case of Cat, he is [mildly autistic]. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be so much under the thumb of his elder sister. I mean, it does make you victim material, very much, to be sort of semi-autistic. Always, when I’m thinking and writing about Cat, I know that he’s not going to tell people anything properly…. It’s a sort of social activity that’s beyond him. Such people can learn of course, and do. But when you’re a child it’s an extreme difficulty.

source

*deep, beleaguered sigh*

I suppose I’ve gotten spoiled by Anne Ursu’s The Real Boy and how wonderfully it handled autism and Word of God confirmation of an autistic character (aka the mc was always intended to be autistic and Ursu did her research and is generally really good and respectful about it, but due to the fantasy setting the word ‘autism’ isn’t used in the book), but it really is a bummer to see yet another author bumble their way through an autism confirmation with ableist language and ideas about what autism is. It could be worse, I definitely got some autism vibes from Cat, and it’s nice to have it confirmed even in a clumsy way, but still. The implication that the only reason Cat got manipulated by his sister was that he’s autistic, and in general the language of “semi-autistic” and the entire section describing the “worst cases” don’t make me very confident that Diana Wynne Jones actually knew anything about autism prior to writing Cat, or even after writing Cat, honestly.

But still, it’s always nice to have canon autistic characters, even if they’re handled in a clumsy way, so thank you for letting me know!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay but, real talk, why the FUCK is The Real Boy from Anne Ursu so underrated?? I mean it has:

- An autistic protagonist who has very real and relatable struggles, an actual personality and a will of his own that drives the plot (yes I know that is not a high bar to reach but most books with autistic characters are miles beneath it). (Disability in Kidlit basically summed up my entire opinion about the autism-related parts of the book perfectly, go check out their review.) (Actually I might write something on it myself because I am so fucking happy that this book managed to avoid all the damanging tropes bless)

- AMAZING worldbuilding, like hot damn.

- A unique take on magic that answers many basic questions a lot of books forget to answer, like:

* Where does it come from?

* What are the consequences of using it?

* Should there be ethical limitations on the use of magic, even if that use doesn’t directly hurt others?

- A lot of good commentary on human greed and how it affects the world around us.

- GREAT dialogue between all characters, but especially between our two mains.

- A successful shift in tone around half way through, when the book suddenly starts getting darker, but it still manages to keep the spirit of the beginning and it’s well-executed and gripping, which is seriously hard to do, so major props there.

- An interesting resolution to the problem the characters face, even if it’s somewhat impractical.

tl;dr: The Real Boy by Anne Ursu is, despite its horrendous title and some minor plot problems, an amazing book that people should be talking about.

#The Real Boy Anne Ursu#That's the tag I'm gonna use I think#seriously though guys this book was longlisted for the National Book Award#and not even one fanart that I could find#get yourselves together

2 notes

·

View notes