#Written Language

Text

Random Stuff #12: What is Simplified Chinese?

For people like me who grew up speaking and using Chinese in day to day life, the vast majority of us have at least a basic understanding of what Simplified Chinese is, but it wasn’t until some days ago when an English speaker asked me “what is Simplified Chinese?” that I realized not many people here understand what Simplified Chinese is. So, I’ve gathered some misconceptions I’ve encountered both in real life and online, and I will try to answer them in a concise but factual manner.

But first, let us talk basics. There are three things we must cover first before going into this topic. The first is the fact that both Simplified Chinese (简体中文) and Traditional Chinese (繁體中文) used today are modern standardized systems of written Chinese, as in both were compiled within the past 100 years or so (modern Simplified from 1935-1936, then again from 1956 and on; modern Traditional starting from 1973), and the two currently widely used versions of both systems were officially standardized in the past 50 years (modern Simplified current version standardized in 2013; modern Traditional current version standardized in 1982). However, since simplified characters already exist in history (called 简化字/簡化字 or 俗体字/俗體字/”informal characters”), and “Traditional Chinese” can be taken to mean “written Chinese used in history”, in this post I will use “modern Simplified/Traditional Chinese” or “modern Simplified/Traditional” when referring to the currently used modern standardized systems.

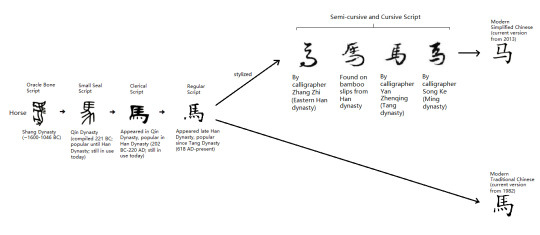

Second is the evolution of written Chinese. Usually when this is taught, instructors use examples of how certain characters evolved over time, for example one might encounter a linear diagram like this in Chinese class:

(Original picture from Mandarinpedia)

However, this diagram only gives a very general idea of how characters evolved from more picture-like logograms to the more abstract symbols we call characters today, and does not reflect the complexity of this evolution at all. To get into these details we will need to talk about Chinese calligraphy. In terms of the evolution of written Chinese, Chinese calligraphy--all those scripts like oracle bone script (甲骨文), bronze/Jinwen script (金文), Seal/Zhuan script (篆书/篆書), Clerical/Li script (隶书/隸書), Regular/Kai script (楷书/楷書), etc--they aren’t just calligraphy fonts, but actually change the way characters are written, and are representative of the commonly used forms of written Chinese at different points in Chinese history, as in the appearance of a certain script on a historical artifact can actually be used to estimate how old the artifact is. Below is a (very) rough timeline of when each script appeared and when they are most popular:

Oracle bone script/Jiaguwen (甲骨文): Shang dynasty (~1600 BC-1046 BC)

Bronze/Jinwen script (金文; includes Large Seal script/大篆): Western Zhou dynasty (~1046 BC-771 BC)

Seal/Zhuan script (篆书/篆書; sometimes called Small Seal script/小篆 or Qin script/秦篆): compiled in Qin dynasty by chancellor Li Si/李斯 around 221 BC, was the official script in Qin dynasty (221 BC-207 AD); popularity went down after Qin dynasty but was still in use for ceremonial purposes like official seals (the archaic meaning of 篆 is “official seal”, hence the English name); still in use today in very specific areas like seal stamps, calligraphy, logos, and art.

Clerical/Li script (隶书/隸書): appeared in Qin dynasty, became the main script used in Han dynasty (202 BC-220 AD); popularity went down after Han dynasty but was still in use; still in use today in specific areas like calligraphy, inscriptions/signatures on traditional Chinese paintings, logos, and other art.

Regular/Kai script (楷书/楷書): appeared in late Han dynasty, became the main script used in Tang dynasty and has been popular ever since (618 AD-present).

(Note: there are other calligraphy scripts like Semi-Cursive script/行书/行書 and Cursive script/草书/草書 that were never mainstream yet were also significant, especially in the case of modern Simplified Chinese, but I will mention them later so this won’t become too confusing)

So if we plug the information from the very rough timeline above into the linear diagram, it becomes this:

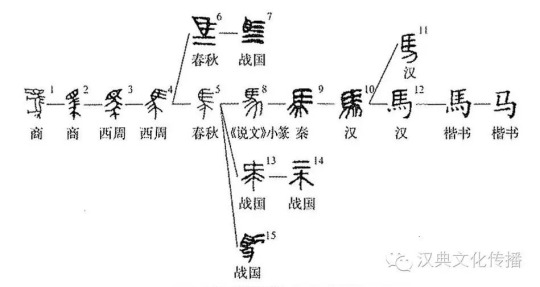

But wait! There’s even more! Because there is a thing called variant Chinese characters/异体字/異體字, which basically means that there have been multiple ways in which a character can be written (“one character, many forms”/一字多形), and these can come about as a result of homophones, personal preference of historically significant people, historical trends, mistakes in the past that stuck around, or the result of stylized scripts like Cursive script/草书/草書, which simplifies and connects strokes in a liberal manner. The reason Cursive script is important here is because of the logographic nature of written Chinese, meaning the simplifying or connecting of strokes actually changes how the character is written. Because of this, 马 and 馬 were forms that have already existed before modern Simplified and modern Traditional were compiled. A diagram that takes variations and evolution into account should look something like this:

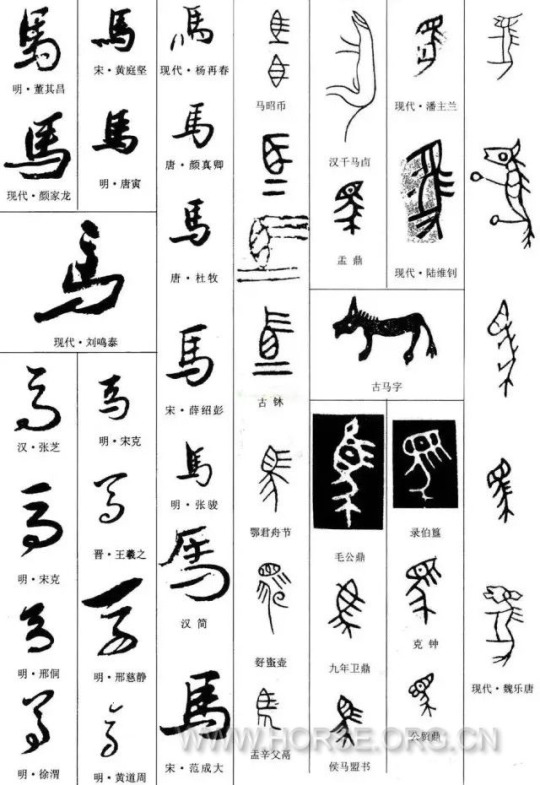

And since the above diagram did not take Cursive script into account, here’s another picture of a myriad of scripts/fonts (not in chronological order) that includes 馬 in Cursive script (mostly on bottom left):

Now you may have an idea of where modern Simplified and Traditional Chinese came from: they are both compiled from existing variants. Since both modern Simplified and modern Traditional are supposed to be standardizations of written Chinese, they each set a single variant for each character as the “standard”. Modern Traditional Chinese kept the more historically mainstream 馬, and modern Simplified Chinese substituted it with the simpler variant 马. Taking all of this into account but still keeping it concise for our topic here, our linear diagram from the beginning should be modified to look like this:

And that’s just an example of a single character. This evolution diagram can differ depending on the character too, due to there being other rules for simplifying characters. This is why standardizing written Chinese is an immense amount of work, but once standardized, the written language will be streamlined and much easier to use in communication.

Finally, we are ready to clear some misconceptions.

---------------------------------------------------

About Common Misconceptions Regarding Modern Simplified Chinese:

“Simplified Chinese replaced all Traditional Chinese characters”. Untrue. Modern Simplified Chinese only standardized 2274 of the most used Chinese characters and 14 radicals with simpler variants. That’s really all there is to it. For reference there are a total of about 60,000 Chinese characters, and about 3,500 of these are deemed to be often-used characters; so only ~3.7% of all Chinese characters and ~65% of often-used Chinese characters are simplified in modern Simplified Chinese. Play around with any online tool that can switch between modern Simplified and modern Traditional, and you will find that many characters stayed the same.

“Simplified Chinese is the opposite of Traditional Chinese”. Untrue. Modern Simplified Chinese is just a simplified and standardized system of written Chinese. Modern Simplified Chinese and modern Traditional Chinese are not “opposites” of each other at all, just different standardized systems serving different purposes. Modern Simplified was compiled with ease of use in mind, since Traditional characters can be time-consuming to write, for example imagine writing 聲 (sound) when you can just write 声 instead. Also back when Simplified was being introduced to the public, a huge part of the population was illiterate, especially farmers, poor people, and women, so Simplified Chinese was a great way to quickly educate them on reading and writing, and to improve efficiency in all aspects of life. Knowing how to read and write is key to education, and education is a must if people's lives were to be improved at all.

“Simplified Chinese is Mandarin”. Untrue. Mandarin is a spoken dialect that came from Beijing dialect, and both modern Simplified and modern Traditional Chinese are modern standardized systems of written Chinese. One concerns the written language and the other concerns a spoken dialect.

"Simplified Chinese was invented by the Communist Party". Untrue. As mentioned before, most characters used in modern Simplified Chinese are already present in ancient texts, artifacts, and inscriptions as variants. Apparently the only character simplified by PRC was 簾 (blinds/curtain), which became 帘 in modern Simplified Chinese. History wise, Republic of China was the first to start compiling Simplified Chinese in 1935 and introducing it to the public, but this was called off after 4 months. PRC modified and built on the original plan, and introduced it to the public again starting from 1956.

"Simplified Chinese is to Traditional Chinese as Newspeak is to English in 1984". Completely untrue. Modern Simplified Chinese is just a simplified way to write commonly used Chinese characters and does not alter the meaning of the characters. There are some Traditional characters that are combined as one simplified character in modern Simplified, but the meanings are not lost or altered. For example, 發 fā (development) and 髪 fà (hair) are combined as 发 in modern Simplified, resulting in 发 having 2 different pronunciations (both fā and fà), and each of these pronunciations carrying their original meaning. The meaning of neither 發 nor 髪 was lost, 发 will just have a longer dictionary entry.

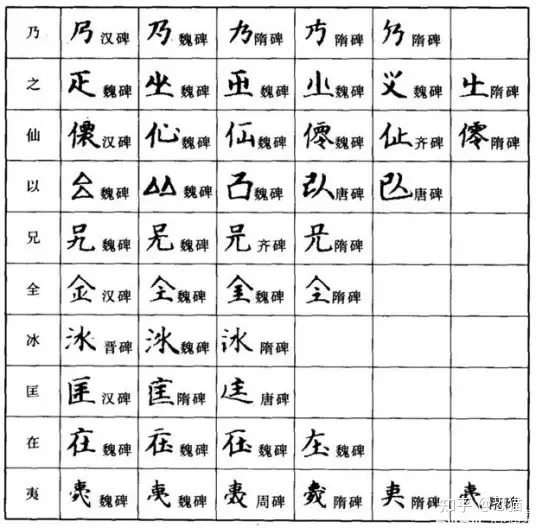

"Simplified Chinese is a huge change from Traditional Chinese". Only partly true in that it is a change, but it is a change justified by the evolution of written Chinese throughout history. The origin of most modern Simplified Chinese characters come straight from history itself, since many characters had alternative ways in which they were written (sometimes for convenience), for example these characters below. Each row contains different forms of a single character (smaller characters indicate what time period these variants are from; ex: 汉碑 means the variant is from a Han dynasty inscription).

In reality, written Chinese has always been standardizing itself. Less-used variants become forgotten over time, sometimes only rediscovered through archaeology. Besides, effective written communication does partly rely on standardization of the written language (imagine everyone writing in the various variants...how horrible would that be?). Modern Simplified just took this one step farther and made some characters easier to write.

“Traditional Chinese is no longer used in Mainland China”. Untrue. Modern Simplified is the commonly used form in Mainland China, but Traditional is still used in a variety of places, such as on store signs/brand logos, particularly for stores/brand that are old. For example the old Beijing brand 天福号 below (est. 1738). On their logo, 天福号 is written as 天福號 from right to left, which is the traditional way of writing horizontally.

Traditional Chinese is also used in the logos for many universities in China:

Another way in which Traditional Chinese is commonly used in mainland China are personal seal stamps. Often times when people carve seal stamps for personal use (for example showing ownership on artwork they created or collected), they would put their name/courtesy name/nickname on the seal stamps in Zhuan/篆 calligraphy font, and Zhuan font use Traditional Chinese. Of course, the ways in which Traditional Chinese is still used in mainland China isn’t restricted to these two examples here. There are other places where Traditional Chinese is still used, such as traditional paintings/国画, calligraphy/书法, and many many more.

“People who grew up reading Simplified Chinese cannot read Traditional Chinese”. Depends on who you are asking. I grew up learning only modern Simplified, and I can read Traditional/modern Traditional Chinese just fine without having to actually learn it from anyone. Most people who grew up with Simplified Chinese should be able to read at least some Traditional without help. There are some people who say they can’t read Traditional without taking the time to learn it, but I doubt they’ve really tried, to be very honest.

---------------------------------------------------

And that’s it for the misconceptions!

My personal philosophy regarding modern Simplified Chinese and modern Traditional Chinese can be summed up as 识繁写简, or basically “know how to read Traditional and know how to write Simplified”. In a way, knowing how to read Traditional is a bit like knowing how to read cursive: a lot of history could be lost if we completely stopped using/learning about Traditional Chinese, but to meet the fast pace that modern life demands, I think modern Simplified Chinese is the more convenient choice for writing for day-to-day purposes. Since quite a few posts on this blog concern history, you will find that I usually use both Traditional Chinese and Simplified Chinese for historical things, since modern Traditional Chinese is closest to what people used in the past, and modern Simplified Chinese is more often used now. If it appears that I didn’t put modern Simplified and modern Traditional side by side, that usually means either the characters stayed the same and there’s no need for me to type the same thing out again, or the topic does not call for both to be shown.

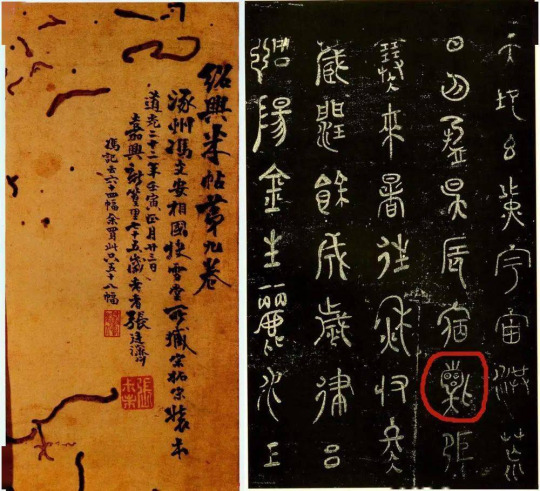

Finally, the fun part. Here’s a Seal/Zhuan script calligraphy work by Mi Fu/米芾 (1051-1107):

Does something look familiar there?

#simplified chinese#chinese language#language#written language#traditional chinese#chinese calligraphy#chinese history#random stuff#what is simplified chinese

991 notes

·

View notes

Text

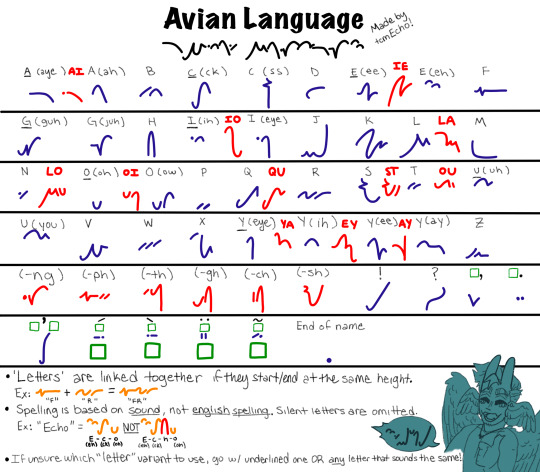

Lookit that! Worldbuilding (of the language flavor) for LLSMP!

If you use this for anything, make sure to credit me :]

#echos ramblings#echo’s sketchbook#loreloverssmp#avian oc#avian language#custom language#worldbuilding#written language#fantasy language

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I was going through one of my notebook when I found a little draft of an alphabet I made for an alien conlang I am working on and I wanted to share it with you all ! 😊

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

#just curious#audhd things#neurodiversity#adhd autistic#audhd#autistic community#adhd community#audhd brain#audhd creature#neurodivergence#language#written language#language poll#language is fun#language is weird#language is beautiful#words are weird#adhd diagnosis#autism diagnosis#neurodivergent community#autistic adhd#comorbidities#comorbid conditions#random polls#tumblr polls#silly poll#tumblr poll#stupid polls#autistic poll#adhd poll

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voices and Pages: Navigating the Pros and Cons of Oral and Written Communication

In the vast tapestry of human communication, two fundamental threads have woven intricate patterns throughout our history: the spoken word and the written script. Both modes of expression, oral and written, bear their unique strengths and weaknesses, shaping the ways we share information, preserve culture, and advance as societies.

Oral Communication: The Power of Spoken Words

Advantages:

1. Immediate Impact: The spoken word carries an immediacy that written language often lacks. In face-to-face interactions, nuances of tone, pitch, and rhythm enrich the message, fostering a deeper connection between speaker and listener.

2. Dynamic Adaptation: Orality allows for real-time adjustments. A speaker can gauge the audience's reactions and tailor their message accordingly, ensuring comprehension and engagement.

3. Cultural Tradition: Many cultures have passed down their histories, myths, and wisdom through oral traditions. Storytelling, poetry, and oral epics are integral to preserving the essence of diverse cultural narratives.

Disadvantages:

1. Ephemeral Nature: Spoken words are transient, existing only in the moment. Once uttered, they often fade into the recesses of memory, unless intentionally recorded or passed down through generations.

2. Limited Reach: Oral communication has geographic limitations. It primarily serves immediate, local audiences, making it challenging to convey complex information across vast distances without distortion.

3. Subject to Interpretation: The absence of a fixed script can lead to misinterpretations. The same oral narrative might be recounted differently by different individuals, introducing variations and potential inaccuracies.

Written Communication: Unveiling the Power of the Written Word

Advantages:

1. Permanent Record: Written language creates a lasting record. From ancient scrolls to digital archives, written communication preserves knowledge, allowing it to transcend time and be shared widely.

2. Precision and Clarity: The written word allows for precise expression. Authors can carefully craft their messages, providing clarity and reducing the likelihood of misinterpretation.

3. Global Reach: With the advent of written languages and translation technologies, written communication can traverse continents, enabling the dissemination of information on a global scale.

Disadvantages:

1. Lack of Immediacy: Unlike oral communication, written messages lack immediacy. Responses are not instantaneous, potentially impeding dynamic, real-time exchanges.

2. Fixed Expression: Once written, a text is static. It remains unchanged unless intentionally edited. This lack of adaptability can be a drawback in situations that demand flexibility.

3. Potential for Misinterpretation: Despite efforts to be precise, written communication is susceptible to misinterpretation. Readers bring their own perspectives and experiences, influencing how they understand written words.

In the ongoing evolution of communication, the interplay between oral and written forms continues to shape our understanding of the world. Whether spoken in the heat of the moment or etched onto pages for posterity, each mode carries its significance, contributing to the rich tapestry of human expression.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#politics#Oral Communication#Written Language#Linguistics#Communication Styles#Literary Arts#Information Transmission#Technological Impact#Cultural Narratives#Societal Development#Media Evolution#psychology#ontology

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

It starts with a conversation about Shakespeare that triggers an old lesson about how humans only used spoken language for a long time before pictographs, hieroglyphics, and written language as we now know it. So in all that time you couldn't just write things down...

You had to remember them.

You had to accurately memorize them.

It turns out our ancestors memorized insane amounts of information through the spoken word. They had to develop that ability in order to pass acquired knowledge between communities and generations.

Memory was their only storage device. An organic storage device.

Once I got thinking on language... I remembered another lesson about the translation of languages and how sometimes one language maps multiple words onto one word in the target language. For example, eight words in ancient Greek onto the one English word, love. As in

I love my wife.

I love hamburgers.

Yeah. Awkward.

Another imperfect memory later and now we're being taught that the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 lasted hours. Crowds gathered at these debates to listen, to engage with them also for hours. As in an hour-long opening statement by one candidate, an hour and a half-long response by the other candidate, and a half-hour rebuttal by the first candidate. The debates attracted crowds of up to 20,000 people including reporters and stenographers who covered the hours upon hours of debate.

Hours?

Yeah. Hours.

Woof.

I point these things out because they’re what made me wonder how different our historic predecessors must have been. After all, they could commit so much acquired knowledge to memory. Their brains were trained on the written word and the way in which the written word forms our understandings of the world. The resulting abilities ushered in deeper human understandings as well as sustained attention to the constructions of reasoned arguments.

I wonder how different these people might be who understood the world around them this way. I wonder how different their predecessors were whose tradition was spoken, whose knowledge was sustained and perpetuated through brute force memory.

How different were they, these people whose abilities are so far removed from our own?

I used to wonder if those abilities made our historical predecessors more capable than us in some way. After all, their oral and written traditions demanded much from them. Definitely their time. Definitely their mental bandwidth.

They exercised their intellects in ways we don't. Because we don't have to. The ways in which we now communicate and perpetuate knowledge bear lighter demands.

Which brings me back to Shakespeare.

Recently I heard a conversation with a professor challenging him to justify reading Shakespeare as a high school or college requirement when we can now understand Shakespeare through ChatGPT. We can generate fifty-word summaries and two hundred-word analyses of Shakespeare with AI and thus know and answer all there is about Shakespeare and his writing.

So why read him?

Seriously. Why?

That's just the tip of the argument, of course. Follow it all the way: Why should we be required to read anything? Novels. Short stories. Essays. What actual purpose does reading even serve when ChatGPT can boil it all down in seconds.

Is there a benefit of deeper knowledge on any subject whether it's a book, a short story, or an essay? And what do we get in exchange for our efforts to achieve such deeper understanding and knowledge. Does that effort, does that understanding, transform us in any objectively measurable way? And if not, does that understanding transform us in some perhaps more fundamental way.

Does it change us? Swap out our abilities like people who communicate primarily through 140 characters whose abilities replaced the abilities of people raised on radio then television whose abilities replaced the abilities of people raised on the written word whose abilities replaced the abilities of people raised on the spoken word.

What’s the actual prize for putting in the time and effort to read what someone else has committed to paper or screen? To deep dive into another human being's mind?

Because the oral tradition required it.

Because the written tradition demanded it.

And now?

Well? Is it or is it not simply good enough to just know what we need to know on demand?

Is access to knowledge the same thing as a deep understanding of that knowledge? And is there a difference that actually, you know, makes a difference?

Is the quality of our understanding really something to strive for anymore? Or is the tradition of study simply a mindless one that's made obsolete by knowledge on demand?

Ultimately, is there some advantage to a more muscular brain? One that’s gotta work harder, be more engaged in order to process the spoken and written word, on ideas and concepts and hypotheses and arguments on its way to understanding?

And.

Are we replacing that specific way of mental processing with something that makes our brains more muscular? More light weight? Or something in-between.

Is it that our mental abilities are now better tallied by the weight (such as it is) of our current mental musculature plus whatever exterior processes augment it like computers and smartphones and AI?

So we shouldn't sweat what we were formerly capable of and can't do now?

Is our resulting intellectual prowess, however it adds up, sufficient for successfully and sustainably navigating our stormy Present that’s seized in a constant state of rapid and relentlessly whirling transformation?

Or is it essentially a product of that change.

And.

Are we fine-tuned for this age of human existence…

Or are we not.

😕

#shakespeare#spoken language#written language#memory#memorize#information#knowledge#storage device#attention#processing#focus#reason#argument#intellect#intelligence#debate#writing#speaking#brains#minds#ability#understanding#abilities#bandwidth#chatgpt#AI#communication#deep knowledge#change#transformation

1 note

·

View note

Text

Are some scripts less prone to the effects of dyslexia than others?

0 notes

Text

First character- says "ah"

0 notes

Text

what happens when you change your web standards to be only english-speaker inclusive

#twitter#elon musk#twitter x#whatever shit name it has now lmao#english#as a note#twitter aint the only page doing this#there are games even that aint letting words that have -nig- inside of them be written as part of an algorithm that checks them out#-nga- and -ngr- also#and spanish and indonesian use those words a lot inside of words and/or can mean sth different in their languages (in indonesian case)#etc etc#wait i forgot if it was thai or indo#oh fuck#oh well

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Getting real tired of reading stories where the author thinks posh people never ever use contractions.

Even the British royal family use contractions. PLEASE USE CONTRACTIONS.

1 note

·

View note

Text

THE QUESTION

"Does writing down what I think and saying what I think activate different parts of the brain and neuropathways? I feel I have an easier time writing than I do speaking, so I wonder. Thank you for your time and knowledge!" - Minski

THE ANSWER

Hi Minski,

Last week I was at the Society for Neuroscience conference (think: 31,000 neuroscientists in the San Diego Convention Center), and I decided the best (read: funnest) way for me to tackle your question was to crowdsource.

So, late on night, at a bar filled with neuroscientists, I posed your question to 3 other Stanford Neuroscience PhD students. Here’s what we came up with, in our informal brainstorming session.

One graduate student remembered a series experiments involving split brain patients (whose corpus callosum, the part of the brain that connects the left and right hemispheres, is severed). So in these experiments, the researchers presented a picture to a patient in such a way that the image filled only ½ of the patients visual field. The idea here is that the visual image would only be captured by one eye, and therefore predominantly only be encoded by one side of the brain (this is a feature of how the human visual system is wired). So the image is presented to only one side of the brain, and then the patients are asked to pick a second object that was associated with the original picture, from a larger sample of objects. So people would pick the object associated with the original picture. And depending on which side of the brain was processing the original image, when the researchers asked the people why they picked the second object, they couldn’t tell the researchers why. But if the researchers then asked the people to write down their reason, the people were able to do that just fine.

Another example comes from the laboratory of Dr. Michael Gazzaniga. His patient, V.J. had her corpus callosum severed as a treatment for intractable epilepsy. After her surgery, V.J. was no longer able to write, but was able to speak and understand spoken language without any problem. So the idea here is that speech and writing are lateralized functions in the brain. Indeed, experiment conducted with the help of V.J. and other split brain patients have lead to the understanding that spoken languages are stored/encoded on the left side of the brain, whereas writing is controlled by the right side of the brain. For a more in-depth discussion of V.J. and the lateralization of speaking/writing, I highly recommend a 1996 article published in the New York Times, “Workings of Split Brain Challenge Notions of How Language Evolved”, written by Sandra Blakeslee.

With our discussion now focused on lateralization of behaviors, another graduate student mentioned a book by Stanislas Dehaene, called Reading in the Brain. This book talks about a lot of ideas, but the basic premise is that there are a lot of visual pathways that words/concepts can go through, that are completely independent from the pathways that those same word/concepts go through when you are hearing them. But at some point, there is a convergence of those various pathways - at some level, there is part of your brain that deals with semantics, where the representation of the written word ‘manatee’, meets the representation of the spoken sound ‘manatee’, and presumably the representation of the image below. So there is a region of your brain that is going to be encoding language, but there seem to be different neural pathways for accessing that general region (visual, verbal, aural). Our discussion reiterated the observation that some people display selective aphasia; for these folks, if you put a picture of a cat in front of them, and ask ‘What is that?’, you’ll get a response of ‘It’s, an animal. Not dog.’ But they won’t be able to say ‘cat’. And if you ask these people to write down that the picture is, they’ll be perfectly able to write the word ‘cat’.

So with these extraordinary examples, our conclusion was that it is not at all unreasonable to think that a person could be better at written language than verbal language, and at expressing their comprehension of language better through writing as opposed to speaking. And indeed this point has been highlighted in non-neuroscience based studies of the most effective ways to teach children: whether teachers should talk to the students or should draw on the board.

1 note

·

View note

Text

outside matters; consonant interruptions; vowels, hieroglyphics

Always excepting moral training, the one thing on this earth most needed by the deaf-mute is the power to comprehend and use written language with facility. That this, as a rule, is the one thing he does not get is our fault — our most grevious fault. We waste useless hours puttering over consonant combinations and vowel sounds, although we know in our hearts that majority of our pupils (semi-mutes are not referred to) will never speak plainly enough to “be understanded of the people,” or we lean comfortably back in our chairs and tell long stories in signs regardless of the fact that the world out into which these children are going knows and cares nothing for signs.

ex Sarah H. Porter, “Language,” American Annals of the Deaf 37: 3 (June 1892): 219-227 (222) : link

University of Virginia copy, via hathitrust

more —

...They must learn to grasp the general meaning — to catch the drift of a sentence or a page without knowing the signification of every separate word. There are countless ways of working towards this end. Leave sentences about outside matters in which they are interested (ten to one your dullest boy reads and understands in the daily papers those base-ball reports which are to you as Chinese hieroglyphics on your your black-board for days at a time. Descend upon them with a slate full of neighborhood news. Make unexpected jokes; no matter if they are bad, your audience will not be critical. Break off short sometimes in the middle of a lesson to introduce some entirely foreign subject. Such an interruption may ruin that particular recitation, but it will make their minds more alert and receptive, will train them to more nimble mental action...

226 : link

Sarah Harvey) Porter (1856-1922), manualist teacher of the deaf

brief bio in finding aid, her papers at Gallaudet : link

also authored —

“Society and the Orally Restored Deaf-Mute” American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb 28:3 (July 1883): 186-192 link (hathitrust)

“The Supression of Signs by Force,” American Annals of the Deaf 39:3 (June 1894): 169-178 : link (hathitrust

link (google books)

“The Education of the Will,” American Annals of the Deaf 42:1 (January 1897) : 16-28 : link (hathitrust)

“The Life and Times of Ann Royall, 1796-1854,” in Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., vol 10 (1907) : 1-37 : link

The Life and Times of Anne Royall (Cedar Rapids, 1909) : link (hathitrust, Yale copy)

from which —

“As a chronicler, Anne Royall possesses points valuable to the historian and student. She was a comprehensive observer. Nothing objective ever escaped her forest-trained eye. She was honest. She had a man’s liking for accurate information about the manner in which things were done and made. Whenever possible, she verified statements. She always went to headquarters for information. She delighted in the multiplication of buildings as the country grew. She loved to gather statistics. Hence her descriptions of places are trustworthy.”

p 239-240 : link

Anne (Newport) Royall (1769-1854)

wikipedia : link

where references include

Cynthia Earman, “An Uncommon Scold” (text of a presentation at the Library of Congress, January 2000) : link

#1892#Sarah H. Porter#written language#education of the deaf#the suppression of signs by force#forest-trained eye#Anne Royall

0 notes

Text

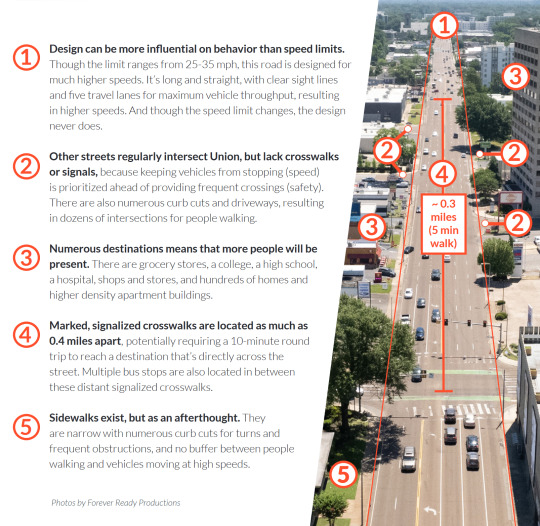

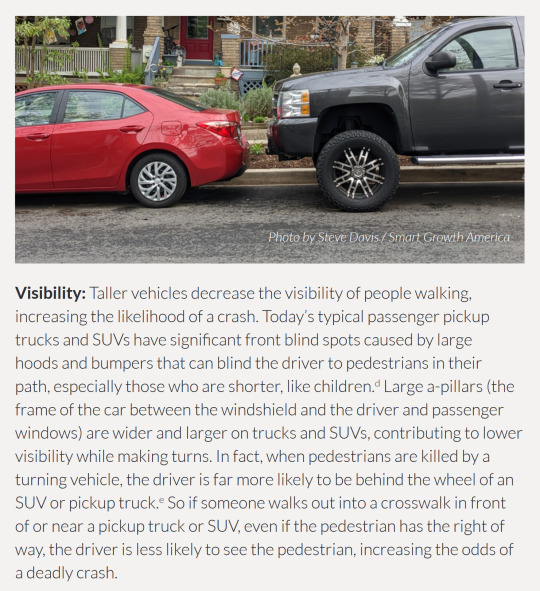

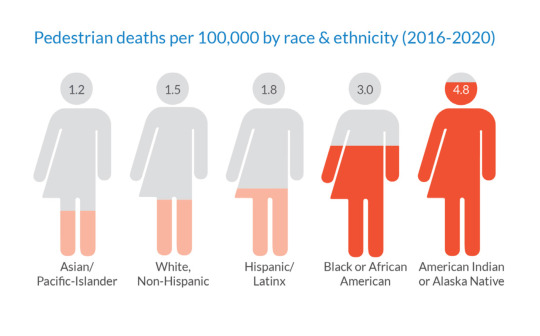

America's Roads: Dangerous by Design

#the link leads to the pdf that i got all these pics + graphics from#very interesting and informative and written in very clear and easy to understand language#please read please reblog this is something im passionate about#mine#pedestrian safety#car centric infrastructure#walkable cities#urbanism#public transportation#urban design

2K notes

·

View notes