#and general introduction of the text itself

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

heart to heart — spoiler

pairing — surgeon! na jaemin x intern! y/n

genre — smut, fluff, angst, age gap (10 years, jaemin is older)

word count — 2.9k

authors note — this is quite a generous and lengthy spoiler, fans of ‘love me back’ and ‘back to you’ will appreciate this one a lot. if you’re not familiar with the other two stories in the ‘love and games universe’ then my only advice would be… become familiar LOL, anyways enjoy my loves <3 don’t say i never gave you anything 🫶

Hayoung’s eyes glitter with mischievous delight as she leans closer, voice dropping to a conspiratorial whisper. She’s always been the resident sleuth, devouring every headline, every whisper in the intern’s lounge, cataloguing names and dates like precious specimens in a private menagerie. For her, uncovering the hidden ties that bind people is as satisfying as stitching new stories into a patchwork quilt. Tonight, she’s your guide through an exclusive gallery of Jaemin’s inner circle, each figure more beguiling than the last.

You draw in a shaky breath and edge nearer to the one‐way glass. Hayoung raises a slender finger toward the towering silhouette at the room’s center, a man whose presence feels as inevitable as gravity itself. His broad shoulders fill the crisp lines of his navy blazer, the fabric stretched ever so slightly across a sculpted chest, each inhale subtly flexing muscle beneath starched cotton. His trousers fall in a perfect, confidence-infused drape, hinting at powerful thighs honed by hours on hardwood courts. A tumble of dark curls grazes the nape of his neck, and when he turns, the faint arc of a smirk reveals a jaw so sharply carved it could slice through the hum of conversation. Even from here you catch the swirl of his cologne, something smoky, dark wood warmed by sunlight and feel the air shift around him. In that moment, Lee Jeno is less a man in a room and more a gravitational force: utterly magnetic, a living testament to strength and elegance entwined.

“That’s Lee Jeno, he doesn’t need an introduction. Everyone knows him, the most influential NBA player of his time.” She murmurs, voice hushed as if narrating a masterpiece. “See how he stands, shoulders squared like the corner of a backboard, every line of his tailored suit whispering discipline and power? He’s an NBA legend, record-breaker, triple-double maestro, the kind of athlete whose name is etched into every stat sheet and every fan’s heart. But more than that, he’s been Jaemin’s north star since they were toddlers dreaming of the same impossible things. He was the first to learn of Haeun’s little heartbeat, sneaking into the NICU at dawn to cradle the tiniest secret in his enormous hands. Off the court, he’s quietly philanthropic, rumor has it he quietly funds scholarships for underprivileged kids in his hometown, though he’d never brag. The media paints him as unflappable, the perfect poster boy for athletic excellence, but those who know him well call him fiercely loyal, the kind of man who shows up whether you’ve invited him or not.”

She lets that settle, then nods toward the woman at his side. “And that,” she continues, “is his fiancée, a vision of composure in couture. They met in college, drifted apart, then discovered that some bonds refuse to break. Their love story is whispered about in fashion circles and sports columns alike: soulful reunions, secret late-night text threads, wedding bells set to ring in just a few weeks. It’s the sort of romance you’d write a novel about—timeless, improbable, and entirely, irrepressibly theirs.”

Hayoung tells you that beyond the fairytale love story, she is every bit her own force of nature: the celebrated face of APEX, a powerhouse executive whose razor-sharp intellect and unflinching moral compass have steered global design initiatives and social impact campaigns for over a decade. In boardrooms she commands deference, in studio ateliers she inspires apprentices, and in every exhibition she curates she challenges viewers to see beauty as a catalyst for change. Each year, she and Jeno co-host the hospital’s signature gala, an evening of crystal chandeliers and whispered promises, where proceeds underwrite life-saving surgeries for families who simply can’t shoulder the cost. Hayoung recalls one gala night to you in particular. When little Haeun, clutching Bunny in one hand and a crayon-scrawled invitation in the other, was lifted onto the stage to present a check; the room hushed as the child’s earnest smile lit every heart, and tears of joy stained even the driest cheeks. It was a moment that crystallized their shared mission, to tether privilege to purpose, and to kindle hope in every young life they touch. Each December, they dispatch carefully curated gifts to every child in the ward—small treasures that, come Christmas morning, become lifelong keepsakes.

“Ryujin and Shotaro’s story is kind of a real-life fairy tale,” Hayoung begins, voice warm. “They met during college, he was mastering a contemporary routine, she was perfecting a lyrical piece and sparks flew over perfect pirouettes. Together they opened a tiny dance school in a repurposed loft, teaching six students and dreaming of bigger things. Now? Twelve studios later, they’ve trained hundreds of young dancers, from hopeful amateurs to budding professionals, and their outreach programs have given every child, no matter their background, a chance to feel the magic of movement. They’re always giggling when they talk about how their after-class water breaks turned into marathon brainstorming sessions. ‘What if we could heal with dance?’ and how every new studio opening felt like adding another heartbeat to the city’s rhythm.”

“And that dream brought them here,” she continues, tipping her voice conspiratorially. “Ryujin and Shotaro now co-design the hospital’s pediatric dance-therapy wing, turning sterile hallways into places where little feet learn strength and resilience. They’ve taught Haeun to pirouette past her fears, remember that time she insisted on ‘just one more spin’ even after her echo scan?—and they’ve choreographed holiday performances where she’s always the star. Their partnership isn’t just about fundraising or fancy recitals; it’s about showing every child that joy and healing can bloom side by side, and proving that sometimes the purest medicine comes in the form of music, movement, and a whole lot of love.”

“You see that hot guy by the window? That’s Lee Donghyuck, he’s a sports anchor whose name you can’t scroll past without wanting to know more. He’s the guy who turned a sideline gesture into a signature catchphrase, but off-camera he’s even more impressive: he spearheaded last year’s ‘Heart Run,’ a charity marathon that raised millions for the pediatric ward, and personally negotiated with sponsors so every dollar went straight to families in need. He’s brokered equipment donations, hosted fundraising luncheons in that very lounge, and somehow still remembers every child’s name who’s ever cross-checked him for an autograph. And don’t think he lets Haeun escape his radar. last month he rolled out a mini basketball hoop next to her play corner, just her size, and taught her how to drain a ‘baby three-pointer’ with a flourish. She squealed so loud you could hear it through the corridor, and he bent down afterward, ruffled her curls, and whispered, ‘You’re my MVP, princess.’ Even now she’s peeking at him, cheeks lighting up every time he offers a thumbs-up from across the room. With Donghyuck, it’s never just television bravado, it’s genuine joy in every high-five and every fundraiser he champions, a constant reminder that heroes come in many uniforms.”

She shifts her gaze to another figure: graceful, magnetic. “And finally, that’s Jang Karina. She doesn’t need any introduction, she’s a fashion powerhouse, her silhouette feels sculpted by intention. Karina began as a runway model whose charisma captivated editors and buyers alike; today she presides over a global design empire, her eponymous label celebrated for its architectural lines and daring palettes, while her beauty brand, praised for its clean formulas and bold pigments, has soared into the multimillion-dollar stratosphere. She pioneers mentorship programs for young designers, spearheads sustainable textile initiatives in collaboration with leading research labs, and curates charity auctions that funnel life-saving funds to children’s hospitals around the world. Every accolade she collects, Vogue cover shoots, Council of Fashion Designers awards, front-row appearances at the Met Gala, has been earned by a woman who learned to temper brilliance with empathy, who moved beyond the runway’s glare into the quiet confidence of a leader whose influence stretches from boardrooms to breaking bread with those she protects.”

“Karina and Dr. Na have a tenderness, a shared history written in soft confidences and midnight phone calls. They met during college before either dreamed of a spotlight, she, a striver fresh from design school; he, a busy surgical resident moonlighting to pay his rent. He didn’t like her in college, but they ran into each other in New York and started fucking intensely. Their first real date was over steaming bowls of bibimbap in a corner café, trading fears and ambitions until the staff nudged them out at closing time. Then life intervened—back-to-back seasons for her, grueling on-call marathons for him—and they drifted apart, each chasing dreams they’d once whispered to each other. They’re not really romantic but I’m sure they still fuck, I could bet on it, that’s how confident I am that I’m correct. They’re co-architects of Haeun’s world. She’s the first to arrive with balloons and homemade cookies on scan days, the one whose laugh draws Haeun from any shyness. Karina helps Dr. Na with Haeun a lot.”

Begrudgingly, you learn that they were lovers once, in that brief, incandescent season before parenthood reshaped his every horizon; the memory of their closeness still simmers behind Karina’s steady gaze. Now she arrives at the hospital not as a distant star but as a second mother to Haeun, smoothing stray curls with the gentlest touch and laughing through bedtime stories whispered in the playroom’s lamplight. When she bends to offer Haeun her lap, the little girl curls in as naturally as into her father’s arms, murmuring “Mama Rina” with the surety of a heart that instinctively knows where comfort lives. In every pivot of her poised stride and every warm look she casts at Dr. Na, you sense the unspoken vow: that this chosen family, wrought from loss and love, will hold its orbit against any darkness that dares encroach.

Her tone softens, eyes drifting back through the glass as if she can already see their silhouettes in the corridor. “They’re legends in their own right. Jeno, with championships and record-breaking buzzer-beaters that make arenas tremble; Karina, whose gowns have rewritten the language of fashion and whose makeup line is in every beauty editor’s kit; Ryujin and Shotaro, whose dance therapy programs have coaxed laughter and movement from children who’d forgotten how to feel joy; Donghyuck, whose voice carries stories of triumph on screens that millions tune in to each night. But none of that matters here. What binds them isn’t fame or fortune, it’s this hospital. This place saved Haeun when her own mother tried to end her life before she even drew a single breath, when she was left to die alone on the rooftop. Doctors patched her broken heart; nurses soothed her frightened sobs; researchers here keep rewriting the rules of what sick children can endure. Every gala Karina co-hosts, every scholarship Jeno underwrites, every dance-floor fund Shotaro and Ryujin open, all of it funnels back into this ward. They fund free surgeries for babies born blue-liped, they underwrite outreach clinics in forgotten towns, they sponsor scholarship nurses who stay to care for children no matter the cost. They do it all because of Haeun. Because she survived the darkness, they learned what true rescue means, and found a way to pay her back in light.”

Your heart twists in your chest as you watch Karina cradle Haeun at the edge of the room, tiny arms fluttering around Karina’s neck like fledgling wings seeking warmth. Karina’s hair tumbles over her shoulders in waves of midnight silk, each strand catching the light of the conference wing’s golden glow. Her posture is an unspoken manifesto of poise: spine straight as a ballet barre, shoulders soft but unyielding, gaze warm enough to melt the iciest boardroom. Haeun’s laughter resonates like a chime, and Karina responds with a low, musical hum, her fingers tracing idle patterns in Haeun’s curls. You step back, scrubs suddenly heavy on your skin, as though you’ve walked into a painting you were never meant to touch. The distance between you and this effortless grace stretches taut, and you wonder how you—ten years her junior, still mastering knotting sutures and bedside manner—could ever bridge the gap. You feel like a child intruding on a world you can’t touch: awkward in your youth, your intern’s scrubs swallowed by the hush of designer silks and tailored blazers.

Your cheeks burn when you realize how small you feel here: stripped of your usual confidence, every inch of your skin prickles with self-consciousness. You recall the times you braided Haeun’s hair, the soft “thank you, my wuv” she pressed against your palm, and you ache to belong in that gentle space again. But here, in the orbit of Karina’s radiance, you are merely a shadow, an earnest trainee whose greatest accolade is a passing nod from Dr. Na. While Karina, in the privacy of their past, has lost herself on his cock a million times, a fiery intimacy you ache to claim as your own. You tighten your grip on the edge of your clipboard, fingernails biting into the paper, and force your gaze back to the room. Yet even as you try to anchor yourself, your eyes betray you, drifting back to Karina’s measured smile, the easy way she curls a lock of Haeun’s hair behind her ear, the quiet assurance that you can never duplicate.

It’s not merely Karina’s beauty that stings, it’s her history, her accomplishments writ large in the world Jaemin inhabits. You think of the single-family flats you shared with overwhelmed roommates, long shifts of charting before dawn, the perpetual undercurrent of imposter syndrome that thrums beneath your every success. Karina, by contrast, has carved an empire from thread and vision, her name sewn onto the seats of fashion capitals from Paris to Tokyo. She is the creative force behind runway shows that have shaped decades of style; the philanthropist whose gala soirées have raised millions for pediatric research; the mentor whose apprentices now stand on stage in their own right. And here she is, bending gentle and unguarded over Haeun—an innocent whose life Karina helped to celebrate, whose future she pledged to support long before you ever learned your first surgical knot.

You flush all the way to your fingertips as you recall Hayoung’s hushed confession about Karina and Dr. Na’s secret trysts—how Karina’s satin lips once pressed against his throat in the moonlight, how she gasped his name as his fingers tangled in her platinum-blonde waves. Your pulse hammers when you imagine those heated nights, Karina draped over him like silk, whispering his name between breathless moans. You bite your lip, thighs trembling, picturing yourself in her place—skin slick, lips parted, arching beneath his touch as he buries himself deep inside you. Every polished step in these hospital halls suddenly feels charged with forbidden promise: could those same strong hands guide your body, curl you into whispered ecstasy until you’re nothing but warm, quivering mush in his arms? The thought sends a delicious shiver down your spine, and you press a hand to your chest, breathing unevenly, desperate for even a flicker of that raw, unfiltered passion Karina once claimed as her birthright.

Karina’s presence is almost mythic: hair that falls in glossy waves around a face sculpted by years of confidence, eyes that have both softened at a child’s smile and hardened at the cruelties of fashion backstage. She embodies refinement and resolve—each step a whisper of silk, each laugh a note of genuine warmth. Haeun clings to her as though born knowing Karina’s arms are safe harbors: tiny fingers threading through Karina’s familiarity, curls brushing Karina’s velvet collar. You watch that bond and ache—you’re not certain you could learn the art of such effortless love, not sure you could anchor Haeun’s heart as deeply, as naturally, as one who has guided her through every high-profile gala and quiet bedtime story alike. In that moment, you feel the full weight of your inexperience, the impossibility of matching a grace so honed, so intrinsic. The envy blossoms bitterly in your chest, and you wonder if you will ever find your own place in Haeun’s world beyond the shadow of these legends.

You turn your gaze inward, the harsh white of hospital walls receding as memory and desire entwine into a single, bitter bloom. You recall the early mornings when you and Haeun would share cereal in the NICU hallway, your voice the only anchor to her frightened world. You remember the fear that distilled your every thought when her tiny chest stuttered for breath, and the primal desire to be the guardian of her heart. Yet here, in the glow of polished floors and the gentle murmur of celebrities-turned-family, you feel neither hero nor protector. only an outsider whose worth is measured in clinical competence, not in the kind of love that sees without pretense. The ache in your ribs intensifies, a reminder that motherhood, in its many forms, is not won by credentials or passion alone but by the quiet alchemy of trust, time, and intimacy. You realize that Karina has woven herself into Haeun’s life with every shared story, every whispered promise, every dance lesson sponsored and every stolen cuddle. And you, still learning the rhythms of both scalpels and lullabies, are left yearning for a place in the soft tapestry they have created. You close your eyes for a moment, drawing a shaky breath, and resolve to carve out your own kind of sanctuary, a space in Haeun’s world defined by your devotion, your sleepless nights, your relentless hope that even the most fragile hearts can find new wings.

taglist — @yukisroom97 @fancypeacepersona @jaeminnanaaa17 @shiningnono @junrenjun @honeybeehorizon @neotannies @noorabora @oppabochim @chenlesfeetpic @kynessa @awktwurtle @euphormiia @hi00000234527 @yvvnii @sunwoosberrie @ppeachyttae @dee-zennie @ballsackzz101 @neonaby @kukkurookkoo @antifrggile @dedandelion @fymine @zoesruby @yoonohswife @jessga @markerloi @ryuhannaworld @yasminetrappy @sunghoonsgfreal @jaemjeno @lovetaroandtaemin @yunhoswrldddd @dowoonwoodealer @enhalovie @jenzyoit @sunseteternal @dewyspace @markiesfatbooty @raysofpolaris @sunseteternal @oppabochim @markerloi @xiuriii

#nct dream#nct smut#nct#nct u#nct x reader#nct hard thoughts#na jaemin#jaemin#nct jaemin#nct na jaemin#nct dream jaemin#nct dream smut#nct jaemin smut#jaemin na#jaemin smut#jaemin x reader#jaemin fluff#jaemin imagines#jaemin angst#na jaemin x reader#na jaemin smut#na jaemin imagines#na jaemin scenarios#na jaemin fluff#nct hard hours#nct scenarios#jaemin x you#jaemin fic#jaemin hard hours#fic — heart to heart

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mithrun's desire as an SA analogue

TW discussion of SA and detailed breakdown of aesthetics evoking SA. The way I discuss this is vivid in a way that may be triggering, though there is no discussion of actual sexual assault. Just survivor's responses to it.

People relate to Mithrun and see his condition as an analogue for a few different things, like brain injury or depression. And I think all of them are there. But I also see Mithrun's story as an SA analogue, and Ryoko Kui intentionally evokes those aesthetics. I think it's a part of Mithrun's character that a lot of people miss, but I very much consider it text. This is partially inspired by @heird99's post on what makes this scene so disturbing; so check out their post, too :)

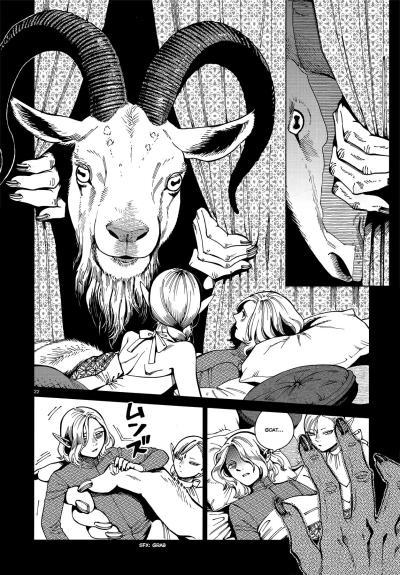

So to start off with, the demon invades Mithrun's bed, specifically. There's even a canopy around it, which specifically evokes this idea of personal intrusion; the barrier is being pulled apart without consent or warning. The way the hand reaches towards Mithrun's body from outside of the panel division makes it almost look like the goat stroking over his body. It's an especially creepy visual detail; similarly, the goat's right hand parts into the side of the panel as well. It's literally like it's tearing the page apart; but gently. So gently.

Mithrun is in bed. It is his bed that the demon is intruding on. He's in a position of intimacy. The woman behind him is a facsimile of his "beloved" that he left behind; the woman who, in reality, chose Mithrun's brother. He is in bed with his fantasy lover, who is leaning over him. While this scene isn't explicitly sexual, it is intimate. And it is being invaded. The goat lifts Mithrun gently, who is confused, but not yet struggling.

The erotics of consumption and violence in Ryoko Kui's work(remember that the word 'erotic' can have many different meanings, please) are a... notable part of some of her illustrations. I would say she blurs the lines between all forms of desire: personal, sexual, gustatory and carnal, in her illustrations in order to emphasize the pure desire she wants to work with and evoke to serve her themes. Kui deploys sexual imagery in a lot of places in Dungeon Meshi, and this is one of them.

In this case, horrifically. The goat's assault begins with drooling, licking, and nuzzling. The goat could be enjoying and "playing with" its food. But it can also be interpreted as it "preparing" Mithrun with its tongue as it begins to literally breach Mithrun's body. The goat also invades directly through his clothing; that adds another level of disturbing to me. There's nothing Mithrun can do in this moment of violation. Mithrun is fighting, but he is fighting weakly, trying to grip on and push away when he has no ability or option to. All he can do is beg the goat to stop. And it doesn't care. This all evokes sexual assault.

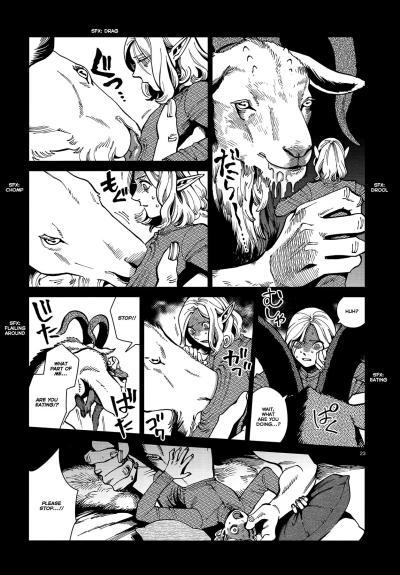

The sixth panel demonstrates a somewhat sexual position, with Mithrun's thighs spread around the goat's hunched over body. In the next, the goat pulls and holds apart Mithrun's thighs as he nuzzles into him. The way the clothing bunches up looks a bit as if it has been pushed up. It has pinned Mithrun down onto the bed, into Mithrun's soft furs and pillows. It takes a place made to be supernaturally warm and comfortable, and violates it. It's utterly and intimately horrifying. To me, this sequence of positions directly evokes a rape scene. I think Kui did this very explicitly. These references to sexual invasion are part of what makes this scene so disturbing; albeit, to many viewers, subconsciously.

This is also the moment the goat takes Mithrun's eye. Other than this, the goat seems exceptionally strong, but also... gentle. It holds Mithrun's body tightly, but moves it around slowly. It doesn't need to hurt Mithrun physically. But in that moment, it takes Mithrun's eye. Blood seeps from a wound while an orifice that should not be pierced is penetrated. This moment, the ooze of blood in one place specifically, also evokes rape. That single bit of physical gore is a very powerful bit of imagery to me.

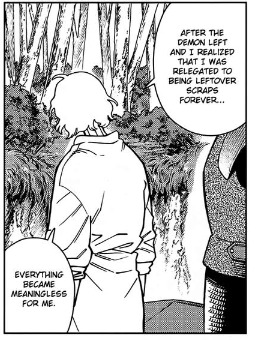

Finally; it is Mithrun's desire that is eaten. After his assault, Mithrun can find no pleasure in things that he once did. He is fully disassociated from his emotions. This is a common response to trauma, especially in the case of SA. It's not uncommon for people to never, or take a long time to, enjoy sex in the same way again; or at all. They might feel like their rapist has robbed them of a desire and pleasure they once had. I think this makes Mithrun's lack of desire a partial analogue for the trauma of sexual assault.

Mithrun's desire for revenge was, supposedly, all that remained. Anger at his assaulter, anger at every being that was like it; though, perhaps not anger. Devotion, in a way. To his cause. I don't know. But the immediate desire to seek revenge is another response to SA. But on to Mithrun's true feelings on the matter.

This is... So incredibly tragic. Mithrun feels used up. Like his best parts have been taken away. Like he's being... tossed aside. This certainly parallels the way assault victims can feel after being left by an abuser. Or the way assault victims feel they might be "ruined" forever for other partners. These are common sentiments for survivors to carry, and need to overcome. In the text, it's almost like Mithrun feels the only being who can desire him is a demon who might "finish devouring" him. That that's his only use. It's worth noting that Mithrun trusted the demon. Mithrun's world was built by the demon, and Mithrun, in that way, was cared for by the demon. I think this reinforces Mithrun's place as a victim.

There's also something to be said about Mithrun as a victim of his own possessive romantic and sexual desire. The mirror shows him his beloved just dining with his brother, and it infuriates him. He doesn't know if the vision is real, nor if she has really chosen his brother as a romantic partner. The goat then creates a whole fantasy world where she loves him. As Mithrun's dungeon deteriorates, she is the only person that continues to exist. Mithrun continues to have control over her. And that is the strongest desire the demon is eating, isn't it? There's something interesting there, but I don't know what to say about it.

In conclusion, I think Mithrun's story is an explicit analogue for sexual assault-- though, certainly, among other things! The way the scene plays out and is composed explicitly references sexual violation and invasion of the body. His condition mirrors common trauma responses to sexual violence. And, at the end, he finally realizes he can recover.

Let's end on a happy Mithrun, after taking the first step on his journey to recovery :) You aren't vegetable scraps Mithrun. But even if you were-- every single thing in this world has value. Even vegetable scraps.

#Mithrun#mithrun dungeon meshi#dungeon meshi#ren rambles#dungeon meshi meta#tag later#I refuse to post at prime time look at my dunmeshi meta boy#tw sa#sa tw#this is literally 1200 words slash 6 pages if I added citations and a proper essay format as well as an introduction to Mithrun's character#and general introduction of the text itself#this could literally be an academic paper#lmao#ren meta#rb this plsss i want ppl to read my essay

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

WLW - Women-Loving Wizard(esse)s? Lesbian love spells from Roman Egypt

I said there will be no dedicated femslash february-adjacent post this year, and in the end that turned out to be nominally true. That’s only because this article, which I didn’t plan too far ahead, is a few weeks late due to unforeseen irl compilations. In my previous, also unplanned, article I’ve included a brief introduction to the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri, and discussed some unusual attestations of Hecate in them - perhaps some of the most fun material to research not directly related to anything I usually write about I’ve had the pleasure to go through in a long while. This text corpus is a gift that keeps on giving in general, but perhaps the single most welcome surprise was learning that there are at least two - possibly three - examples of lesbian love spells in it. While I considered waiting for pride month to cover them, I ultimately decided to publish an article about them much sooner (I have a different, highly esoteric pride month special in the pipeline already though, worry not).

Without further ado, let’s take a look at these unique wlw (women-loving wizard) testimonies and their historical context. Which supernatural entities were, at least for these women, apparent lesbian allies? Why does one of the lesbian spells contain an elaborate poetic passage pairing Osiris with Persephone? Why Lucian of Samosata might be the key to determining if 2 or 3 lesbian love spells are available to researchers? Answers to all of these questions - and more - await under the cut!

Before you proceed, I feel obliged to warn you that the article discusses historical homophobia, so if that might bother you, you’ll have to skip one of the sections. Furthermore, some of the images, as well as parts of the text itself, are not safe for work.

Part 1: the spells

Through the article I will refer to the discussed texts as “lesbian spells”. This is merely intended as a convenient label, not a definite statement - we can’t be 100% sure of the orientation of everyone involved, obviously. On top of that, none of the spells give us any hints about the terms the women involved in their composition used to describe themselves. Needless to say, the fact that the discussed spells even exist is nothing short of a miracle. The corpus of magical papyri and other related objects like inscribed tablets and gems is relatively small, and covers a short period of time - for the most part just the first four centuries CE. On top of that not all of them are specifically love spells. For comparison, while there is a sizable corpus of Mesopotamian love incantations spanning over two millennia, not even a single lesbian one has been identified among them so far (Frans A. M. Wiggermann, Sexuality A. In Mesopotamia in RlA vol. 12, p. 414).

They also represent one of the only indisputable examples of ancient texts in whose composition women who at the very least desired relationships with other women were involved (Bernardette J. Brooten, Love Between Women. Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism, p. 105). How active that involvement was might be difficult to ascertain, though.

Spell 1: angel or corpse daimon? The first spell of the discussed variety I’ve stumbled upon lacks a distinct title, but it’s included in the basic modern edition of many of the magical papyri, The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells edited by Hand Dieter Betz, as PGM XXXII. 1-19 ( p. 266):

It was discovered in Hawara, an archeological site in the Fayum Oasis, and most likely dates to the second century CE (Love Between…, p. 77). At the time of its initial publication, some doubts were expressed about whether it’s really a love spell by authors such as Richard Wünsch - as you can imagine, for at least implicitly homophobic reasons - but it’s been the consensus view for a long while that it's explicitly lesbian. I left the brief comment included in the standard modern edition on the screencap above to highlight this. It needs to be stressed here that the opposition to this now mainstream interpretation was a minority opinion in the first decades of the 20th century already, and was conclusively rejected as early as in the 1930s (Arthur S. Hunt notably contributed to this) and basically never entertained by any authors since (Love Between…, p. 80-81). Sadly, there is not much to say about the dramatis personae of the spell. Herais’ name is Greek, but her mother’s, Thermoutharin, is Egyptian; both Helen and Sarapias are Greek names, but the latter is theophoric and invokes, as you can probably guess, Serapis. This sort of combination is fairly standard for Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, and it’s not possible to determine if one or both of the women involved were Greeks who settled in Egypt, Egyptians who adopted Greek names, or if they came from mixed families (Love Between…, p. 79).

While it’s likely Herais simply commissioned the spell from a specialist (Love Between…, p. 109), it’s worth noting that in the most recent commentary on it I was able to find, Heta Björklund argues that she was a magician herself (Invocations and Offerings as Structural Elements in the Love Spells in Papyri Graecae Magicae, p. 38). She also assumes some of the heterosexual love spells were the work of female magicians. Sadly, in the relatively short period of time I dedicated to preparations for this article I failed to find any study which would make it possible to establish whether this is a proposal with more widespread support. Female conjurers are certainly not uncommon in works of fiction, though, so even if the magical papyri were mostly written by men until proven otherwise I see no strong reason to doubt that we’re really dealing with a wlw (women-loving wizard).

The vocabulary employed in Herais’ spell is identical as in the heterosexual love spells. However, since examples aimed at both men and women are known, and do not significantly differ in that regard, the fact most of them were written by men seeking to secure the love of women doesn’t necessarily imply Herais necessarily took a masculine role herself just because she adhered to the same convention regarding magical formulas (Love Between…, p. 105).

An interesting aspect of the spell are its theological implications. At least from Herais’ perspective, Anubis, Hermes and “the rest down below” - in other words, a host of other unspecified deities residing in the underworld, not to mention the entity invoked to help her - not only would have no objections to her orientation, but would actively aid her in securing the love of the target of her affection (Love Between…, p. 80).

Invoking deities is basically a standard in love spells, regardless of the orientation of the people involved. Three distinct categories of them can be identified: Aphrodite and her entourage (ex. Eros and Peitho); heavenly deities (like Helios and Selene) and, perhaps unexpectedly, underworld deities (Hecate, Hermes, Persephone and others) - and, by extension, ghosts. From the first century CE onward it was actually the last group which appears most commonly in love spells. This likely reflects their association with magic and fate (Invocations and Offerings…, p. 45-46).

While there’s no point in dwelling upon the references to Anubis and Hermes, which are self-explanatory, there is some disagreement about the nature of Evangelos, who Herais basically asks to act as a supernatural wingman for her. Björklund argues that he should be interpreted as an angel or divine messenger (Invocations and Offerings…, p. 38). This is not implausible at first glance. Angels are invoked in multiple other spells from the magical papyri as helpers. For example, PGM VII 862-918 focuses on a request to Selene to send one of her angels presiding over a specific hour of the night (Leda Jean Ciraolo, Supernatural Assistants in the Greek Magical Papyri, p. 283; as a side note, there's a chance I will discuss early angels - especially the oddities like PGM angels - in a separate future article).

However, another view is that Evangelos was a “corpse daimon” (nekudaimon) - this would offer a good parallel with other love spells. What was a corpse daimon, though? Simply put, the restless, but not necessarily malevolent, spirit of a person who died prematurely (Love Between…, p. 80). In Egypt this idea intersected with other views on the origin of ghosts - for example that they could be people who died so long ago nobody made tomb offerings to them (Ljuba Merlina Bortolani, Magical Hymns from Roman Egypt. A Study of Greek and Egyptians Traditions of Divinity, p. 224). It’s possible that in some cases, perhaps including Herais’, papyri with spells have been deposited in, or at least read above, the graves of people who died in circumstances which made them eligible to become corpse daimons, in order to secure their help (Love Between…, p. 80). There is also evidence that food could be left for them in appropriate places instead, as attested for example in the “love spell of attraction in the presence of heroes or gladiators or those who died violently” (ωγὴ ἐπὶ ἡρώων ἢ μονομάχων ἢ βιαίων; PGM IV 1390-1495). This was a practice derived from a common type of offering to Hecate and her ghost entourage (Magical Hymns…, p. 223). It’s worth noting a daimon didn’t necessarily have to be human - the “cat spell for all purposes" (ἡ πρᾶξις τοῦ αἰλούρου περὶ πάσης πράξεως; PGM III 1-164), described as equally effective whether employed as a love spell, enmity spell or… a way to alter the results of chariot races (a relatively common goal in the magical papyri). instructs how to enlist the help of a “cat daimon” (τὸν δαίμονα τοῦ αἰλούρου). In this case the magician has to first “create” this entity by offering a cat as sacrifice, though, instead of invoking a preexisting daimon (Invocations and Offerings…, p. 32).

Spell 2: Osiris, Persephone and inflamed liver

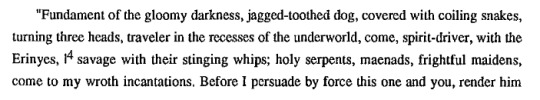

While the spell discussed above seems to be brought up online the most often in discussions of references to lesbian and gay love in antiquity, the second known example is much more elaborate. Its standard translation was published in 1990 in the first volume of Robert W. Daniel’s and Franco Maltomini’s Supplementum Magicum, intended as a supplement to the already mentioned compendium of translated magical papyri (p. 137-139):

The text is inscribed on a tablet discovered in Hermopolis, and dates to the third or fourth century CE (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 132). It’s possible it was commissioned from a magician, rather than written by Sophia herself. Both her name and Gorgonia’s are not declined, which might indicate that a magician simply inserted them into blank spaces in a preexisting formulary offered to clients (Love Between…, p. 88-89). It’s nonetheless quite interesting as a work of literature, even if it was just a stock formulary sold over and over again. Some sections deliberately use poetic forms. Furthermore, some of the long compound words in them are entirely without parallel. It’s possible that this was a conscious source meant to create a peculiar overwhelming atmosphere, suitable for invoking ghosts and underworld deities (Love Between…, p. 88). While Herais’ spell is brief and vague and doesn’t really reveal much about her desires, beyond establishing that the object of her affection was a woman and that she believed supernatural entities would plausibly approve of pursuing her, Sophia’s commissioned(?) one seems to involve a pretty detailed fantasy. Of course, an argument can be made that it doesn’t necessarily specifically reflect her individual desires, but rather the widespread perception of bath houses as places suitable for flirtation and related ventures (Love Between…, p. 89). Still, while obviously we’ll never be able to know, it’s interesting to wonder if she perhaps had to choose from a larger repertoire of love spells offered by a magician (or perhaps even by multiple magicians) and went with the formula which matched her expectations to the greatest degree. Interestingly, the idea of a love spell being more effective in bath houses recurs in multiple magical papyri. The view that they can be haunted was fairly widespread, which made them a favored location for casting spells of all sorts, to be fair. The request for the “corpse daimon” to masquerade as a bath attendant to help with accomplishing a specific goal is unparalleled, though (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 132-133).

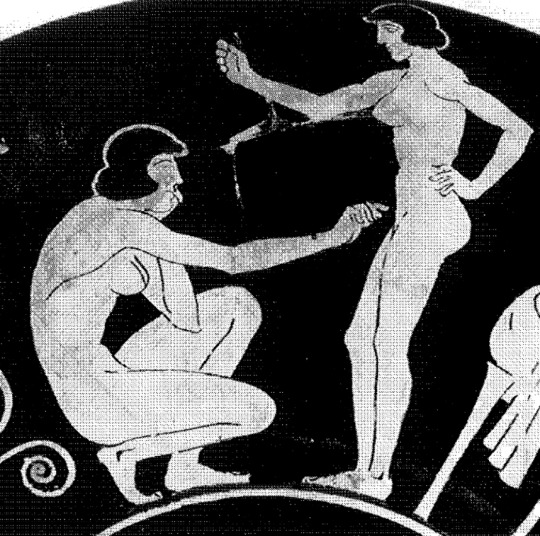

A combinative "Isis-Persephone" (or vice versa) from the late second century CE (Wikimedia Commons) As far as other appeals to supernatural entities go, it might be surprising to see Osiris mentioned in association with Persephone, Cerberus, the Erinyes and various elements of topography of the Greek underworld. It is presumed that this passage depends on the identification between him (as well as Serapis) and Hades, which is fairly well documented in Ptolemaic sources (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 146). However, it’s also worth pointing out that Persephone could serve as the interpretatio graeca of Isis, though it was by no means exclusive, and the latter could in various contexts or time periods be linked with Demeter, Cybele, Selene, Hecate, Aphrodite and others instead (Magical Hymns…, p. 9-10)

The unnamed “messenger” of Osiris is presumed to be Hermes, invoked not under his proper name but under a standard Homeric epithet. Referring to him as a “boy” most likely reflects the convention of depicting him as a child, which is attested through Hellenistic and Roman periods (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 146-147).

In addition to invoking a nameless corpse daimon and a number of deities, the spell uses a lot of voces magicae - magical formulas with no apparent meaning, sometimes the result of religious terms or even theonyms from langues other than Greek and Egyptian . Perhaps the most interesting inclusion among these is “Ereschigal”. This is obviously a derivative of Mesopotamian Ereshkigal, though as I outlined in my previous article, we’re essentially dealing with a ship of Thesus in this case; and if we are to take this as a reference to a specific deity rather than a hocus pocus formula, it’s best to think of it as an unusual epithet of Hecate as opposed to a conscious reference to a deity from a theological system otherwise basically entirely absent from Greco-Egyptian magic. The other interesting cameos are Azael and Beliam, a misspelling or variant form of Belial (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 144).

One last detail which requires some explanation is the reference to inflaming the liver, in addition to heart and soul. This is not a magical curiosity, but rather a reflection of a belief widespread all across the Roman Empire in the first centuries CE: the liver was believed to be the organ responsible for passions of various types. Invoking it alongside the heart in spells is well documented (Love Between…, p. 90).

Spell 3: the pronoun controversy

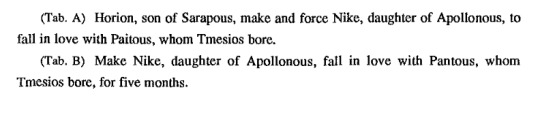

There might be a third lesbian spell. It is inscribed on two lead tablets from Panoplis, most likely from the second century CE (Love Between…, p. 90-91). The provenance was possible to establish based on the presence of the name Tmesios, “midwife”, which in Egyptian was written with the same determinative as the names of gods. It is most likely an euphemistic reference to Heqet, the goddess of midwifery, who was a very popular deity of Panoplis (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 116-117). The most recent edition I’m aware of is included in the Supplementum Magicum, vol. 1 (p. 116):

The text is undeniably a standard love spell. It even features an appeal to a corpse daimon - a certain Horion, son of Saropus - like the two discussed above (Love Between…, p. 91). The fact he is invoked by name is unusual - most corpse daimons are left anonymous (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 115). A further unique detail is the inclusion of a small drawing of a mummy - generally assumed to be Horion:

The supposed corpse daimon, via Supplementum Magicum vol. 1, p. 116; reproduced here for educational purposes only. An alternate proposal is that this is a symbolic representation of Nike being affected by the spell, as there are no other depictions of corpse daimons, and such entities are consistently described as mobile, which to be fair indeed doesn’t fit a mummy particularly well (Christopher A. Faraone, Four Missing Persons, a Misunderstood Mummy, and Further Adventures in Greek Magical Texts, p. 151-152). Still, unless further evidence emerges, there’s no reason not to stick to the consensus view.

Next to the mummy drawing, the other mystery is the reference to a period of five months. Why exactly would Nike be under the effect of the spell for that period of time remains uncertain (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 117). It might be a nod to the notion of “trial marriage”, which also lasted for five months. After this period, the parties involved would determine whether they want to formalize the relationship with a written contract or part ways instead (Love Between…, p. 107). However, by far the main topic of debate regarding the spell is the gender of Pantous/Paitous. While Nike bears an undeniably feminine name, the other name is not spelled consistently even on the tablets themselves, and has no other attestations. This also holds true for Gorgonia from spell #2, but in her case there’s no ambiguity - the name is undeniably feminine. However, -ous can be a suffix of both feminine and masculine names; while pa- occurs in Egyptian names as a masculine prefix. To make things more complicated, in both cases the relative pronoun referring to Pantous/Paitous is feminine - but it has been suggested that this is a typo due to presence of an incision on the tablet which might indicate the scribe made a typo wanted to actually write the masculine form. The gender of this person is thus difficult to determine (Love Between…, p. 93-94).

The assumption that we’re dealing with a double typo, according to the authors of the most recent translation, is supported by similar typos in other magical papyri, where the context makes it easier to ascertain the gender of the parties involved (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 117). Bernadette J. Brooten argues this is an overabundance of caution, though, since the spell under discussion is the only example where every single pronoun would have to be a typo. Furthermore, there are no other errors in the text (Love Between…, p. 95).

Brooten also offers an interesting solution to the uncertainty stemming from Pantous/Paitous’ name itself: even if it is masculine after all, its bearer might have been a woman who took on a masculine persona in some contexts, complete with a masculine name, or perhaps a nickname. She offers a precedent for this interpretation: the character Megilla/Megillos from Lucian of Samosata’s Dialogues of the Courtesans (Love Between…, p. 96). Since exploring this topic fully goes beyond the scope of the spells themselves, I will explore it in more detail in a separate section.

Part 2: WLWizards in context

From Plato to Lucian

In the fifth of Lucian’s dialogues a certain Leaina discusses recent events in her life with a friend. She is, as you can probably tell from the title of the whole work, a courtesan. At some point in the not-so-distant past she encountered a person who she refers to as Megilla, but who, as she stresses, at one point used the name Megillos in private. The character is AFAB, but for all intents and purposes presents masculinely - “like the most manly of athletes”, to be precise, as they describe it (Love Between…, p. 52). They engage in typically masculine pursuits, like holding symposiums, cut their hair short like young men (but wear a wig in public to hide that) and bring up that another character, Demonassa, is their wife in order to stress own masculinity (Andreas Fountoulakis, Silencing Female Intimacies: Sexual Practices, Silence and Cultural Assumptions in Lucian, Dial. Meretr. 5, p. 119-120). From a modern POV, it might appear that Megillos is a partially closeted trans man whose name is the masculine form of his deadname, but while this would be an obvious angle for a retelling to take, in reality the character is an example of a Greco-Roman stereotype of a woman attracted to women. Lucian refers to Megilla/Megillos as a hetairistria. He states that this rare term refers to women who pursue relationships with other women, and explains that this basically makes them like men (Love Between…, p. 23).

It’s important to stress we have no real evidence that this word - or any other ancient labels of similar sort - were actually used by any women to describe themselves (Love Between…, p. 7). Lucian most likely decided to use it as a nod to Plato (Love Between…, p. 53). The plural form, hetairistriai, is used to refer to women attracted to women in his Symposium (Love Between…, p. 41). It was most likely etymologically related to hetaira, in this context to be understood as something like “companion” (though it could also refer to a courtesan - as it does in the original title of Lucian’s work). It’s fairly rare in later sources, though dictionaries from the early centuries CE confirm it was understood as a synonym of tribas (plural: tribades), which was more or less the default term for women attracted to women in Greek, and later on as a loanword in Latin as well. An anonymous medieval Byzantine commentary on Clement of Alexandria, a second century CE Christian writer (more on him later) provides a second synonym, lesbia, which constitutes the oldest attested example of explicitly using this term to refer to a woman attracted to women, rather than to an inhabitant of Lesbos, though the context is not exactly identical with its modern application as a self-designation, obviously (Love Between…, p. 4-5). In Symposium the existence of hetairistriai is presented neutrally, as a fact of life - the reference to them is a part of the well known narrative about primordial beings consisting of two people each. Plato apparently later changed his mind, though, and in Laws, his final work, he condemns them as acting against nature (Love Between…, p. 41). It has been argued that the negative attitude might have been widespread in the classical period, though for slightly different reasons - it is possible that relationships between women would be seen as a transgression against the dominant hierarchy of power, on which the notions of polis and oikos rested (Silencing Female…, p. 113). As far as I can tell this is speculative, though.

While Plato’s rhetoric about nature finds many parallels in later sources - up to the present conservative discourse of all stripes worldwide (though obviously it is not necessarily the effect of reading Plato) - other arguments could be mustered to justify opposition to relationships between women as well. In one of his epigrams the third century BCE poet Asclepiades decided to employ theology to that end. He declared that the relationship between two women named Bitto and Nannion was an affront to Aphrodite; a scholion accompanying this text clarifies that they were tribades (Love Between…, p. 42). Note that I don’t think the fact that all three of the lesbian spells don’t invoke Aphrodite is necessarily evidence of the women who wrote or commissioned them adhering to a similar interpretation of her character, though - especially since they are separated by a minimum of some 500 years than the aforementioned source. While obviously we can’t entirely rule out that Asclepiades’ poem reflected a sentiment which wasn’t just his personal view regarding Aphrodite, it seems much more likely to me that the fact all three spells postdate the times when underworld deities and ghosts started to successfully encroach upon her role in this genre of texts is more relevant here. "Masculinization" and related phenomena

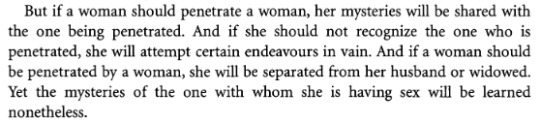

While clearly hostile, neither Plato’s nor Asclepiades’ works contain the tropes on which Lucian’s dialogue depended. What has been characterized by modern authors as “masculinization” of women attracted to other women only arose as a trend in literature after the rise of the Roman Empire, especially from the reign of Augustus onward (Love Between…, p. 42-43). This reflected the fact that Roman thinkers - as well as their Greek contemporaries - apparently struggled with grasping the idea of sex in which they couldn’t neatly delineate who is passively penetrated and who is actively penetrating. This resulted in the conclusion that surely one of the two women involved must have played the “masculine”, active role, and that sex between women must also have been penetrative. In some cases this involved confabulations about what some described in scholarship as an “some unnamed phallus-like appendage” (Love Between…, p. 6). A good example of an author wholly dedicated to this idea is the second century CE dream interpretation enthusiast Artemidoros. He evaluated sex between women as “unnatural” - a category in which he also placed oral, which he however saw as an act which by default had a man on the receiving end (Love Between…, p. 181). The sole passage in his opus magnum dealing with sex between women can be seen below (translation via Daniel E. Harris-McCoy, Artemidorus’ Oneirocritica. Text, Translation & Commentary, p. 149):

It needs to be pointed out here that earlier visual representations do not appear to be quite as fixated on this point. Evidence includes a Greek red figure vine vessel dated to 515-495 BCE or so decorated with a scene involving a woman touching another’s inner thigh and genitals; another slightly younger work of similar variety shows a kneeling woman reaching for another’s genitals, though it might depict depilation (contemporary sources indicate women plucked public hair by hand) rather than sex (Love Between…, p. 57-58). I must admit I really like the contemplative expression of the kneeling woman, which you can see on the screencap below (also available to view here):

Obviously, works of art such as the one above don’t necessarily reflect an ancient wlw point of view, and might very well be voyeuristic erotica which instead reflects what male painters presumed lesbian sex entailed. However, alongside a slightly bigger number of contemporary works possibly depicting couples in other situations they nonetheless make it possible to establish that the participants aren’t really differentiated from each other - in other words, they neither present differently, nor seem to be separated by age (Love Between…, p. 59).

Needless to say, it’s difficult to tell if either the older or the newer sources reflected actual trends in presentation among women attracted to women - with small exceptions, like the spells this article ultimately focuses on, we have next to no texts actually composed by them or for them, and the same caveat applies to visual arts. The majority of sources we are left with were, as you can probably already tell based on the sample above, written by men who at the absolute best considered them immoral (Silencing Female…, p. 112-113). For this reason, evaluating whether Lucian’s Megilla/Megillos is entirely literary fiction or merely a mocking exaggeration, and by extension whether she can be used as an argument in discussion about the identity of Pantous/Paitous from the third spell, is difficult at best.

For what it’s worth, an anonymous physiognomic treatise from the fourth century does mention that there are “women who have sex with women whose appearance is feminine, but who are more devoted to masculine women, who correspond more to a masculine type of appearance”, but further passages in this work would indicate that this might be yet another case of stereotyping rather than a nuanced account of varying presentation (Love Between…, p. 56-57). One specific aspect of Megilla/Megillos' character appears to match a single other source as well. Claudius Ptolemy, a second century astronomer and astrologer, offers a twist on the stereotype relevant to his primary interests. He states it is one of the “diseases of the soul” in his Tetrabiblos. He characterizes it as a result of a specific combination of constellations and planets (a term which in this context also encompassed the sun and the moon) at the time of an individual’s birth. Based on the specific scenario, women might become tribades - which according to Claudius Ptolemy means behaving in a masculine manner and pursuing relationships with other women secretly or openly, with the most extreme possible configuration resulting in a propensity to refer to another woman as one’s “lawful wife” (Love Between…, p. 124-126). Once again, it’s not really possible to determine if this reflects a genuine convention - though it does more or less parallel how Megilla/Megillos describes her partner. Evaluating how accurate the available sources are is made even more difficult by the fact that the “masculinization” was often paired with other literary devices meant to cast relationships between women as an “alien” or immoral phenomenon. Quite commonly they could be described as something utterly foreign or anachronistic, as opposed to a part of everyday life in contemporary Rome (Love Between…, p. 42-44). The second century writer Iamblichos, author of the lost Babyloniaka, or at the very least the popularity of his work in antiquity, arguably represents an example of this phenomenon. On the moral level, Iamblichos considered love between women “wild and lawless”, though he simultaneously had no issue writing about it, one would assume for voyeuristic purposes. His novel is only known from a summary preserved by the Byzantine patriarch Photius, but apparently enjoyed a degree of popularity earlier on. It described an affair between Berenike, a fictional daughter of an unspecified ruler of Egypt (fwiw, multiple women from the Ptolemaic dynasty bore this name), and a woman named Mesopotamia (sic), and their eventual marriage (Love Between…, p. 51). In contrast with the other, more famous Babyloniaka by Berossos, no primordial fish people or sagacious rulers with unnaturally long life spans make an appearance. A daring project to combine the two has yet to be attempted. Jewish and Christian reception

The Greco-Roman condemnations of relationships between women was also adopted in early centuries CE by Jewish and Christian writers. In the former case a notable example is the Sfira, a rabbinic theological commentary on Leviticus composed at some point before 220 CE. The passage dealing with 18:3 - “You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt (... )and you shall not do as they do in the land of Canaan” - asserts that marriages between women were a custom among Egyptians and Canaanites. This is unlikely to be a faithful ethnographic report; rather, something perceived negatively is attributed exclusively to foreigners (Love Between…, p. 64-65). As far as Christian sources go, pretty similar rhetoric can also be found in Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (Love Between…, p. 64). Another notable early Christian author to adopt similar views was Clement of Alexandria, whose condemnations combined quotations from Paul’s letter, the apocryphal Apocalypse of Peter (which he viewed as canonical), and a host of Greek and Roman philosophers, most notably Plato - as you can guess, specifically the passage from Laws which already came up earlier (Love Between…, p. 320-321). He dedicates a lot of space to condemning marriages between women, which he describes as an “unspeakable practice” amounting to women imitating men (Love Between…, p. 322). It’s a part of a longer diatribe against even the slightest hints of gender nonconformity, which also condemns, among other things, men who shave their facial hair (Love Between…, p. 323-324). There’s a lot of other smash hits in Clement’s work, including an extensive section focused on, to put it colloquially, theological considerations about cum, very creative mixed religious-zoological approach to the digestive system of hares, as well as some more “mundane” but still pretty chilling apologia for domestic abuse, which I will spare you from. For an author from Alexandria, he also seems oddly ignorant about Egyptian sources, as at one point he claims that the fact Egyptians worship animals puts them morally ahead of Greeks, because animals do not commit adultery. I am sorry to report that adultery between Egyptian gods is, as a matter of fact, directly referenced in the magical papyri, which are roughly contemporary with Clement - specifically in PGM IV 94-153 (The Greek…, p. 39):

Concluding thoughts The sources discussed above are mostly supposed to illustrate that while it’s possible to study the prevailing attitudes among the contemporaries of the “protagonists” of the spells, it’s not really easy to say what their private lives were like. We don’t know how open they were about their preferences; how they presented; what, if any, label they used to refer to themselves. We can’t even ascertain if any of them were ever actually in relationships with other women, and whether the norm for women like them - if such norms even existed - was to pursue brief trysts or commitment for life, in parallel with aims of the authors of at least some of the heterosexual love spells (Love Between…, p.105-107).

In what after almost 30 years remains, as far as I am aware, the single publication with the most extensive discussion of the spells, Bernardette J. Brooten argued that since marriages between women are mentioned in five sources roughly contemporary with them - by Lucian of Samosata, Clement of Alexandria, Claudius Ptolemy, Iamblichos, and in the Sifra - they must have been an actually observed custom in Egypt in the early centuries CE. She argues that since marriages were basically personal legal agreements, it theoretically wouldn’t be impossible for two women to pursue such a solution (Love Between…, p. 66; note the fact the Sfira also refers to marriage between women as a Canaanite custom, which no primary sources from any period corroborate, is not addressed). I don’t think her intent was malicious, but I must admit I’m skeptical if it’s possible to reconstruct much chiefly based on sources which, as you could see in the previous section of the article, are mocking at best and openly hostile at worst, and a small handful of actual first hand testimonies which due to their genre sadly provide very little information. Sadly, we ironically can tell more about how the women from the spells thought corpse daimons functioned than how they envisioned the relationships they evidently desired.

To illustrate the difficulties facing researchers, imagine trying to reconstruct what the life of the average lesbian in the English-speaking world in the 2010s would be like with your sole points of reference being a single episode of a Netflix show with a mildly offensive gender nonconforming character, a press article written by an eastern European priest ranting about “gender ideology” imported from abroad corrupting children, a fanfic written by a homophobic weeb who jacks off to lesbian porn, and a small handful of contextless blog post actually written by wlw, but not necessarily entirely focused on anything related to her identity. The results wouldn’t be great, I’d imagine. The sources mustered by Brooten ultimately aren’t far from that, I’m afraid (I leave it as an intellectual exercise for you to determine which of the satirical modern comparisons applies to which) - thus it’s difficult for me not to see her conclusions as perhaps leaning too far into the direction of wishful thinking. But, in the end, wishful thinking is not innately bad - I’d be lying if I said I don’t have a host of personal hypotheses which fall into the same category (one of these days I will explain why I think a “don’t ask, don’t tell” attitude doesn’t necessarily seem incompatible with Old Babylonian morals). Therefore, even though I’m more skeptical if the “protagonists” of the texts this article revolved around could truly pursue relationships on equal footing with other inhabitants of Roman Egypt, I can’t help but similarly hope that they found at least some semblance of happiness in the aftermath of the endeavors documented in the discarded magical formulas.

89 notes

·

View notes

Note

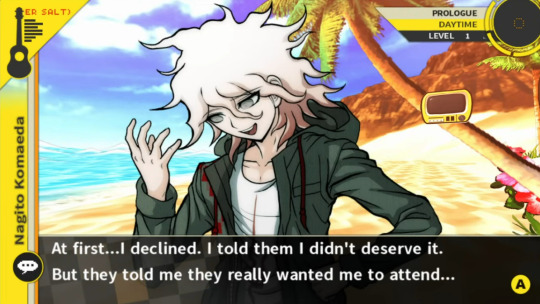

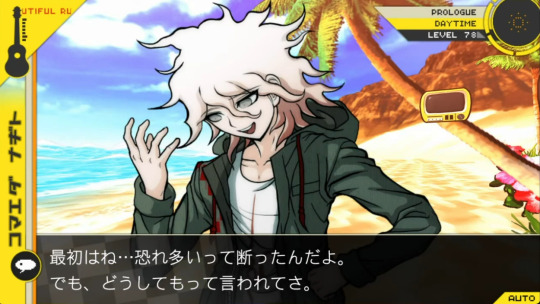

is komaeda as self deprecating in japanese as he is in english? in his introduction he’s moreso humbly denying hope’s peaks offer than saying he wasn’t worthy. so i was wondering if komaeda comes off as incredibly humble more than self deprecating. or if the translators just really went ham on the self deprecation and got rid of any nuances

Hi! Thank you for the ask and I'm sorry it took so long for me to get to it! I had actually written a reply a few days ago, but Tumblr deleted it...😭 I was too mad to re write it then and there lol. But also, I think I could have been more clear (I wrote it while still recovering from being sick), so I'll try my best this time.

Firstly, if I'm understanding right, you're wondering if Komaeda is NOT self-deprecating, but instead just humble. There's a short answer and a long answer. The short answer is no, he does just blatantly put himself down in the text. The long answer is it may not be as bad as it is at certain parts. So now, I'll explain.

Firstly, let's re-visit the prologue. I've spoken about this specific line more than once.

KOMAEDA: Um, honestly, at first...I was humbled, but I refused. But, well, they wouldn't stop insisting on it…

In this scene, yes, Komaeda isn't putting himself down...necessarily. So, the word in question being used here is 恐れ多い. This word seems to give translators trouble. Back before there was an official SDR2 translation, there was a fan-translated version on the SomethingAwful forums by user orenronen.

Generally, I consider orenronen's translation to be more faithful at times. But NISA actually was closer in this case.

恐れ多い literally translates to "extremely scared", but it's really not used in that way. Think of it like any phrase or idiom...."You can't have your cake and eat it too" isn't meant to be literal. It's just a way to say "you can't have both things at the same time".

恐れ多い is a common phrase in Japanese when declining a big offer. For example, your boss gave you the chance for a big promotion, but you declined. You would use 恐れ多い. It can be used to indicate you feel you aren't good enough for the position - this is not a weird thing to say, as being humble is a core part of Japanese culture.

However, at it's core, 恐れ多い just means "I'm very sorry, but no, thanks".

Back to that example. Your boss gives you a chance for big promotion. You would take it, but your boss needs you to move cities for it. You don't want to move. So, you say, "Oh...Thank you so much, but I must humbly decline."

In the past, I explained this phrase kind of poorly and made it sound like it's only used to say you feel you don't deserve the position...what I meant to say was that the word gives the feeling of you not feeling good enough to accept, but that doesn't mean you actually don't feel good enough. Does that make sense? It's like saying "Sorry" as a courtesy when you do something wrong, but maybe you don't actually feel sorry.

In short, this line is ambiguous. The text literally says, 恐れ多いって断ったんだよ, which means (literally) "I refused by saying "No, thanks (humbly)"." Komaeda tells us what he told HPA verbatim, but he doesn't elaborate on why he said that. Did he decline because he did feel undeserving? Maybe he actually was scared to accept, maybe because of his luck? Or did he simply have no interest, and declined without much thought? - It's left to the player to speculate on his reasons.

This is a big part of Komaeda's character, I think. As discussed, he speaks very softly - sounding unsure, or making his statements sound less forceful. The SDR2 artbook itself states that they went back and redid all of his sprite work to make his emotions appear more ambiguous. It's very apparent that not knowing what Komaeda is truly thinking or feeling is a big part of his character. Hinata himself laments about this in many FTEs with him.

I think the writers simply took advantage of the humble culture in Japanese to drive this home. Is he simply humble, or does he really mean what he says?

Now...don't get me wrong: Komaeda does go beyond being humble. He does outright insult himself in a way that is unmistakably not humble.

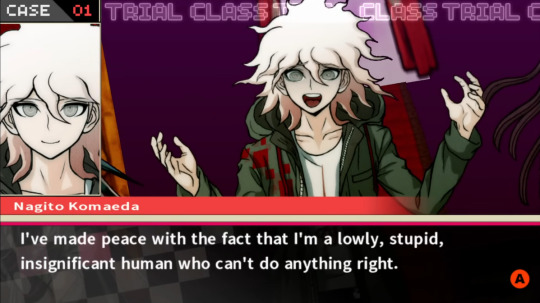

Take the chapter 1 Trial:

KOMAEDA: ボクは決定的に��低で最悪で愚かで劣悪で、何をやってもダメな人間なんだ。 KOMAEDA: I am, without a doubt, an awful, horrible, ignorant*, inferior, worthless person, and that will never change no matter what I do.

*Komaeda isn't calling himself stupid necessarily. I don't really know how to put it, but it's like...you do stupid things, but you yourself may or may not be intelligent. It's kind of like no matter how smart you get, you will always make dumb mistakes. I hope that makes sense.

This is not being humble. This is very self-deprecating stuff and things nobody would (or should) say about themselves in any sort of casual setting. This is a very shocking turning point because, up until now, Komaeda was just humble. Putting himself down lightly, saying his talent "isn't much" and that he's not as important as the Ultimates sound reasonable, sounds humble. This isn't reasonable or humble, and he says it with very strong assertion, indicated by なんだ and the end.

Also, he never says he's "made peace" with it (which I take to mean he's okay with it?) but that may have been this NISA translators' answer to the なんだ at the end, as it makes Komaeda sound like he's stating a fact. I don't agree simply because I feel like his feelings should be left ambiguous as said earlier...but I understand the mindset.

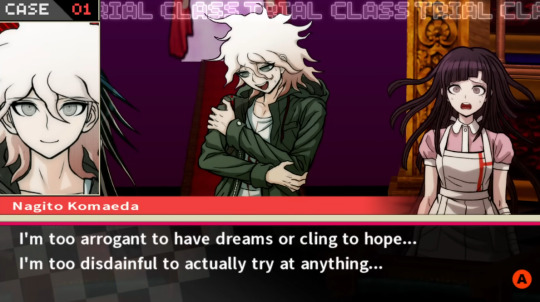

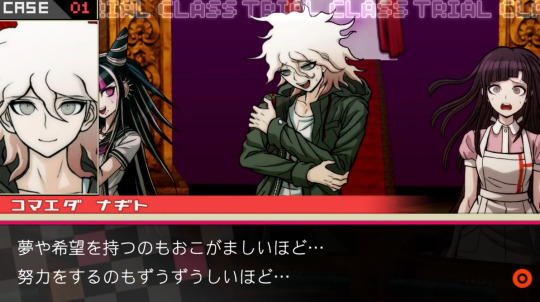

By the way, before that...the team totally mistranslated a line that had me tilting my head for five minutes trying to figure out how the two connected.

KOMAEDA: 夢や希望を持つのもおこがましいほど・・・努力をするのもずうずうしいほど・・・

I couldn't quite figure out why the NISA translation felt so off to me but the Japanese didn't, and it took me a bit of thought but I figured it out. It's because NISA got the topic of the conversation wrong.

See...Komaeda never says "I'm" in this sentence. It's normal not to say "I'm" in Japanese, though. Topics can be inferred. But then, the next line, where he talks about how he's awful, horrible, etc., he does start with "I am" (ボクは) indicating a change in topic. Meaning the topic of the sentence before it is not about him but about the subject of having dreams and hopes/trying hard.

That might sound confusing, but let me write what this line should look like:

KOMAEDA: It'd be pretentious of me to have hopes and dreams...it'd be audacious of me to try and work hard...

Basically, Komaeda is saying having hopes and dreams is too good for someone like him, and that him working hard to strive for something would be an insult to others.

This definitely makes sense for the next line, where he then says this will never change no matter what he does.

The official English gets it backwards, and now it sounds like he's too...good for these things? To me, at least.

To be fair, because of how it's written, it's easy to make that mistake. But I feel like they should have realized it makes no sense translated that way. Hm...

Anyways, as you can see, Komaeda does say things that are not merely being humble. He truly does have awful opinions of himself, or at least states them in a very pointed, factual manner.

You can argue that his humbleness is an extension of his self-deprecation...or maybe he's just both at the same time. Up to the audience to think.

Lastly, Komaeda often times says ボクなんか or ボクなんて (boku-nanka and boku-nante), which translates literally as "someone like me". It puts yourself down, like, "Someone like me can't be in such a cool club..." or something. This can be humble as much as it can be self-deprecating. It depends on the context of its usage, which I think does hit home with that ambiguous vibe.

I think that's it...I really hope this answered your question! Thank you for the patience!

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts About the Potential Underlying Hidden Tragedy of Yanqing and Jing Yuan

that isn't just the "Yanqing will have to kill Jing Yuan eventually" red flags.

A relatively longer-ish post so thank you for bearing with me if you choose to do so!

I'd already been thinking about this whole mess of thoughts for a long while now, and so have other people, but the urge to write this came from a comment I saw on a post that mentioned how Yanqing had lost to "Jing Yuan's ghosts" and overall how it contributes to the dynamic of them being mentor/mentee + father/son. While the narrative seems to be leading to "Yanqing having to strike down a Mara-stricken Jing Yuan," there's just enough weird points that stick out to the point some alternative outcomes for Yanqing and Jing Yuan's fates to play out.

And while I anticipate HSR to follow that most expected point, I feel like there's enough there that could lead to a subversion or something more likely than that, an additional twist to the knife alongside the expected point.

Jing Yuan's Flaws as a Mentor and Father-Figure:

While most of us love the family fluff, I'm pretty sure we can all acknowledge the issues in Jing Yuan's approach and decisions in regards to Yanqing. Yeah, this is a fictional space game story where it's likely they aren't going to delve into the consequences of having someone as young as Yanqing be a soldier, there seems to be something there regardless. Like the brushes with death that he has and how we see him have to worry about the Xianzhou's security as a teen due to having a higher position in a military force. This is all set up for more of a coming-of-age type narrative for him, which HSR has done amazingly so far, but there are a lot of chances for this to explore something darker.

Among official media, the one time I could even remember the term "father" being used in relation to Jing Yuan is in Yanqing's official Character Introduction graphic:

Another notable thing that we see here is how we do have moments where Yanqing expresses thoughts and questions about his own origins and birth parents. The fact that even here, he wonders if the general is hiding something from him, sets off some alarm bells in my head. But he then brushes that off because he's always been with the General and Jing Yuan accepts him for who he is (which under the theory that Yanqing originates/is connected to the Abundace adds a whole heavy layer (this will be discussed in a later section)).

Yanqing does something similar in his texts:

As Huaiyan says to Jing Yuan:

"Yanqing can understand your concerns."

Alongside Yanqing generally being a considerate and polite boy, it can possibly be said that his eagerness to share Jing Yuan's burdens not only stems from his own gratitude towards him but possibly also Jing Yuan's distance.

As in, Jing Yuan doesn't really express his feelings so blatantly, and what we can clearly tell from when Yanqing first met "Jing Yuan's ghosts," neither does he speak much about his past too on a personal level. In Jingliu's quest, Yanqing says that Jing Yuan simply told him to forget everything he saw that day.

For Jing Yuan, the loss of the quintet is a grief that feels fresh in his heart, especially with echoes of them running around him. This is in the description for "Animated Short: A Flash":

(Will also talk about this in a different section)

While Yanqing learns about his General's past in a more direct manner (aka the people involved), it's sad how avoidant Jing Yuan is at times. While he's never been a upfront person, especially in the case of solving problems, I wonder if HSR would go as far as to show the negative side of that in terms of raising and teaching Yanqing.

History Repeats Itself (Sometimes It Don't Need A Reason):

+ the Jingliu parallels

Following up on that last image, Jing Yuan, especially in A Flash, has that whole "history repeating itself" thing going on for Jing Yuan. It points to Yanqing having to take down Jing Yuan but it also comes with a lot of its own possibilities and meanings.

It's blatant that Yanqing parallels Jingliu to an unsettling degree. Anyone who personally knows Jingliu and meets Yanqing sees her in him. Jingliu probably sees herself in him as well. Beyond powers and passion for the sword, her Myriad Celestia trailer shows that her principles before getting struck with Mara were the same as his. But it took her losing her dear friends in such a cruel and brutal manner (alongside how long she'd been alive) for all of that to fall out and form the version of her we see today.

And while it seems that Yanqing is deviating from Jingliu's due to the teachings he's learning, especially with Jing Yuan's effort, I feel like there's still a chance for things to go so wrong and mess with that. Yukong's line about him strikes me as concerning:

"A sword will vibrate and beg to be unsheathed if it is unused for too long... Once unsheathed, it will either paint the battlefield in blood, or break itself in the process..."

Even though I don't think HSR will go down a route of tragedy with Yanqing, like say, he gets Mara struck somehow or killed because that's not how Hoyo's writing has fully gone for playable characters (Misha and Gallagher aside in terms of death). Even in the most despairing parts for Hoyo's games, they're usually outlined and tinged with hope in one way or another. It's just that with what's been presented, there's got to be more here than meets the eye.

Yanqing's Origins - The Breaking Point:

From what we've been given, I think the number one thing that would have the potential of shaking Yanqing's entire sense of his life and the reality he lives in is learning where he comes from. Where he actually comes from has been a strange mystery since the beginning, how Jing Yuan getting him being recorded in the military annals of all places.

As shown from the screenshots of Yanqing's texts, he doesn't know and tries to brush it off because he's happy with Jing Yuan now. The choice to have this aspect here leaves a lot to ruminate on. What is Jing Yuan hiding? And if he really is witholding information, does he ever intend to tell Yanqing? If he doesn't and Yanqing finds out, how will it play out? And even if he does mean to tell him, depending on the severity, how will Yanqing take it?

It's why the theory that Yanqing is connected to the Abundance, possibly even coming from it directly, is as harrowing as it is.

With his arc in mind, will his development be enough to sustain him when he does find out the truth? If he finds out sooner than he should, will he be able to rise above it? And what of Jing Yuan? If confronted with a situation that's outside of his control again, what will he do and how will he react?

The potential in that scenario is so fascinating to me, because we can all anticipate the absolute gut punch that Yanqing killing his master would be. It fits Hoyo's writing style of something so sad but having a hopeful end for the future type beat. But the idea of that being twisted, that expectation being flipped on its head, could be so agonizing. It's not a narrative we see too often explored, at least in my experience, so maybe that's why I'm brainrotting over it so much lol.

#honkai star rail#hsr yanqing#jing yuan#hsr theory#character analysis#yanqing losing jing yuan is one thing but jing yuan losing yanqing is another lol#i really don't think hsr would do it like that but it'd be wild if they do#at most they're gonna do something that really fundamentally changes them as people haha#new form yanqing perhaps? haha ha#mara struck or abundance form yanqing would be devastating lolol#struggling jpg thinks

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

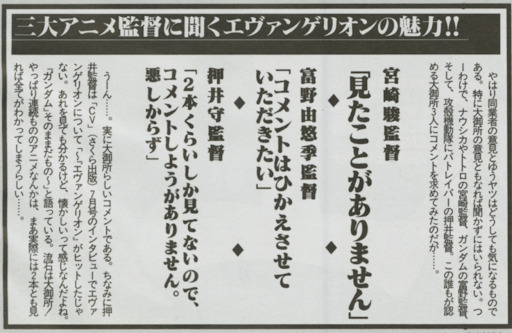

Della Beppin August 1996 Evangelion Feature - Scan & Takeaways