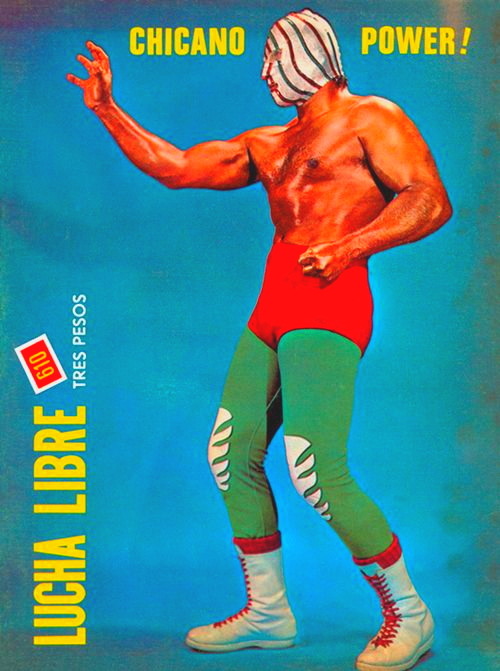

#chicano power

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

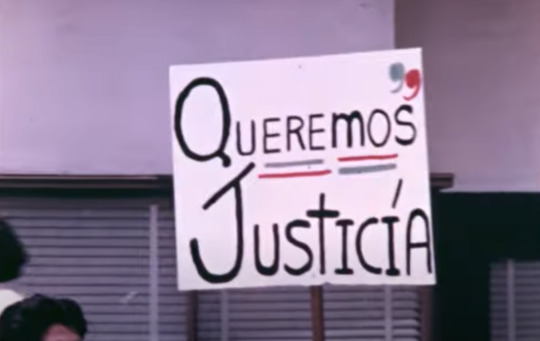

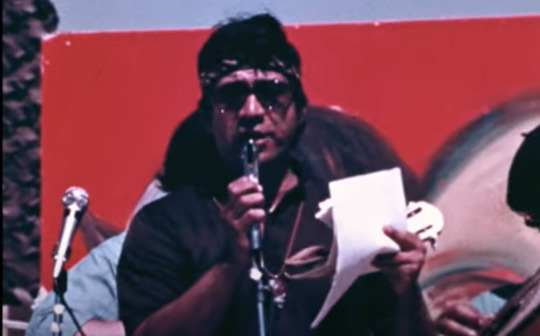

1970.

The Chicano Power Movement.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black & brown lives matter#black lives still matter#blm#brown berets#la raza#black panther party#chicano#blacklovebrownpride#people power

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

introductory excerpts on the rainbow coalition:

The Rainbow Coalition was an antiracist, anticlass[1] multicultural movement founded April 4, 1969 in Chicago, Illinois by Fred Hampton of the Black Panther Party, along with William "Preacherman" Fesperman of the Young Patriots Organization and José Cha Cha Jiménez, founder of the Young Lords. It was the first of several 20th century black-led organizations to use the "rainbow coalition" concept.[2]

...

The Rainbow Coalition soon included various radical socialist community groups like the Lincoln Park Poor People's Coalition,[3] later, the coalition was joined nationwide by the Students for a Democratic Society ("SDS"), the Brown Berets, the American Indian Movement and the Red Guard Party. In April 1969, Hampton called several press conferences to announce that this "Rainbow Coalition" had formed. Some of the things the coalition engaged in joint action against were poverty, corruption, racism, police brutality, and substandard housing.[4] The participating groups supported each other at protests, strikes, and demonstrations where they had a common cause.[5][6]

The coalition later included many other local groups like Rising Up Angry, and Mothers and Others. The Coalition also brokered treaties to end crime and gang violence. Hampton, Jimenez and their colleagues believed that the Richard J. Daley Democratic Party machine in Chicago used gang wars to consolidate their own political positions by gaining funding for law enforcement and dramatizing crime rather than underlying social issues.[citation needed][7]

The coalition eventually collapsed under duress from constant harassment by local and federal law enforcement, including the murder of Hampton.[6]

...

The phrase "rainbow coalition" was co-opted over the years by Reverend Jesse Jackson, who eventually appropriated the name in forming his own, more moderate coalition, Rainbow/PUSH. Some scholars, including Peniel Joseph, assert that the original rainbow coalition concept was a prerequisite for the multicultural coalition that Barack Obama built his political career upon.[11]

The Rainbow Coalition youth—made up of Panthers, Young Lords, and Young Patriots—also launched free breakfast programs that were supported by donations from community businesses and ran free daycare centers for neighborhood children. Several operations were upheld by the women of the Black Panthers and women’s focus groups like the Young Lordettes and Mothers and Others (MAO). The federal government institutionalized the School Breakfast Program in 1975.

“We’re gonna fight fire with water. We’re gonna fight racism not with racism, but with solidarity. We’re not gonna fight capitalism with Black capitalism, but with socialism… We’re gonna fight with all of us people getting together and having an international proletariat revolution,” Hampton was recorded saying.

...

In public appearances, the Rainbow Coalition was backed by community residents and Black and brown street gangs—but they also had the support of unions, Independent Precinct Organizations, college students and activists who supported the movement through Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Rising Up Angry, and countless other organizations. Their allies included Concerned Citizens of Lincoln Park, the West Town Concerned Citizens Coalition, the Northside Cooperative Ministry, Neighborhood Commons Organization, and Voice of the People.

“It was really based on common action,” said Mike Klonsky, a former Chicago leader of SDS (who, like Hampton and Cha-Cha, had a reward out for his arrest). “If there was a protest or a demonstration, the word would get out and we would all come to it and support each other. If somebody was arrested, we would all raise bail. If somebody was killed or shot by the police, we would all respond together.”

...

In December of 1969, the FBI conducted an overnight raid on Hampton’s apartment with intelligence provided by an infiltrator. He had just been named spokesperson of the national Black Panther Party. A barrage of police bullets struck him in his sleep as he lay beside his pregnant fiance, Akua Njeri, who survived. Another occupant, Black Panther security chief Mark Clark, was also killed.

Distraught members of the Coalition unofficially disbanded, and a handful of the leadership went underground after Hampton’s assassination, fearing for their own safety. Thousands of people lined up to witness the open crime scene, while lawyers from the People’s Law Office disputed the later-disproved official police account, which had falsely claimed a heavy firefight on both sides. Having assassinated its most vocal leader, the Feds had effectively crushed the 1960s’ most promising push for united, cohesive social resistance in Chicago.

#reaux speaks#history#rainbow coalition#bipoc#resources#socialism#community#black power#black panther party#young lords#anti capitalism#chicano#indigenous#communism#wikipedia

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kid Congo Powers being beautiful.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I used to think that movie was a comedy, but now I know..it’s a tragedy.

#the Chicano experience involves loving Austin Powers#i don’t make the rules#this fool on hulu#this fool#this fool hulu#chris estrada#frankie quinones

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK, I'll bite - what's the deal with the United Farm Workers? What were their strengths and weaknesses compared to other labor unions?

It is not an easy thing to talk about the UFW, in part because it wasn't just a union. At the height of its influence in the 1960s and 1970s, it was also a civil rights movement that was directly inspired by the SCLC campaigns of Martin Luther King and owed its success as much to mass marches, hunger strikes, media attention, and the mass mobilization of the public in support of boycotts that stretched across the United States and as far as Europe as it did to traditional strikes and picket lines.

It was also a social movement that blended powerful strains of Catholic faith traditions with Chicano/Latino nationalism inspired by the black power movement, that reshaped the identity of millions away from asimilation into white society and towards a fierce identification with indigeneity, and challenged the racist social hierarchy of rural California.

It was also a political movement that transformed Latino voting behavior, established political coalitions with the Kennedys, Jerry Brown, and the state legislature, that pushed through legislation and ran statewide initiative campaigns, and that would eventually launch the careers of generations of Latino politicians who would rise to the very top of California politics.

However, it was also a movement that ultimately failed in its mission to remake the brutal lives of California farmworkers, which currently has only 7,000 members when it once had more than 80,000, and which today often merely trades on the memory of its celebrated founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez rather than doing any organizing work.

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

The Origins of the UFW:

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

In the 1950s, both Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez were community organizers working for a group called the Community Service Organization (an affiliate of Saul Alinsky's Industrial Areas Foundation) that sought to aid farmworkers living in poverty. Huerta and Chavez were trained in a novel strategy of grassroots, door-to-door organizing aimed not at getting workers to sign union cards, but to agree to host a house meeting where co-workers could gather privately to discuss their problems at work free from the surveillance of their bosses. This would prove to be very useful in organizing the fields, because unlike the traditional union model where organizers relied on the NRLB's rulings to directly access the factory floors, Central California farms were remote places where white farm owners and their white overseers would fire shotguns at brown "trespassers" (union-friendly workers, organizers, picketers).

In 1962, Chavez and Huerta quit CSO to found the National Farm Workers Association, which was really more of a worker center offering support services (chiefly, health care) to independent groups of largely Mexican farmworkers. In 1965, they received a request to provide support to workers dealing with a strike against grape growers in Delano, California.

In Delano, Chavez and Huerta met Larry Itliong of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which was a more traditional labor union of migrant Filipino farmworkers who had begun the strike over sub-minimum wages. Itliong wanted Chavez and Huerta to organize Mexican farmworkers who had been brought in as potential strikebreakers and get them to honor the picket line.

The result of their collaboration was the formation of the United Farm Workers as a union of the AFL-CIO. The UFW would very much be marked by a combination of (and sometimes conflict between) AWOC's traditional union tactics - strikes, pickets, card drives, employer-based campaigns, and collective bargaining for union contracts - and NFWA's social movement strategy of marches, boycotts, hunger strikes, media campaigns, mobilization of liberal politicians, and legislative campaigns.

1965 to 1970: the Rise of the UFW:

While the strike starts with 2,000 Filipino workers and 1,200 Mexican families targeting Delano area growers, it quickly expanded to target more growers and bring more workers to the picket lines, eventually culminating in 10,000 workers striking against the whole of the table grape growers of California across the length and breadth of California.

Throughout 1966, the UFW faced extensive violence from the growers, from shotguns used as "warning shots" to hand-to-hand violence, to driving cars into pickets, to turning pesticide-spraying machines onto picketers. Local police responded to the violence by effectively siding with the growers, and would arrest UFW picketers for the crime of calling the police.

Chavez strongly emphasized a non-violent response to the growers' tactics - to the point of engaging in a Gandhian hunger strike against his own strikers in 1968 to quell discussions about retaliatory violence - but also began to employ a series of civil rights tactics that sought to break what had effectively become a stalemate on the picket line by side-stepping the picket lines altogether and attacking the growers on new fronts.

First, he sought the assistance of outside groups and individuals who would be sympathetic to the plight of the farmworker and could help bring media attention to the strike - UAW President Walter Reuther and Senator Robert Kennedy both visited Delano to express their solidarity, with Kennedy in particular holding hearings that shined a light on the issue of violence and police violations of the civil rights of UFW picketers.

Second, Chavez hit on the tactic of using boycotts as a way of exerting economic pressure on particular growers and leveraging the solidarity of other unions and consumers - the boycotts began when Chavez enlisted Dolores Huerta to follow a shipment of grapes from Schenley Industries (the first grower to be boycotted) to the Port of Oakland. There, Huerta reached out to the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and persuaded them to honor the boycott and refuse to handle non-union grapes. Schenley's grapes started to rot on the docks, cutting them off from the market, and between the effects of union solidarity and growing consumer participation in the UFW's boycotts, the growers started to come under real economic pressure as their revenue dropped despite a record harvest.

Throughout the rest of the Delano grape strike, Dolores Huerta would be the main organizer of the national and internal boycotts, travelling across the country (and eventually all the way to the UK) to mobilize unions and faith groups to form boycott committees and boycott houses in major cities that in turn could educate and mobilize ordinary consumers through a campaign of leafleting and picketing at grocery stores.

Third, the UFW organized the first of its marches, a 300-mile trek from Delano to the state capital of Sacramento aimed at drawing national attention to the grape strike and attempting to enlist the state government to pass labor legislation that would give farmworkers the right to organize. Carefully organized by Cesar Chavez to draw on Mexican faith traditions, the march would be labelled a "pilgrimage," and would be timed to begin during Lent and culminate during Easter. In addition to American flags and the UFW banner, the march would be led by "pilgrims" carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadelupe.

While this strategy was ultimately effective in its goal of influencing the broader Latino community in California to see the UFW as not just a union but a vehicle for the broader aspirations of the whole Latino community for equality and social justice, what became known in Chicano circles as La Causa, the emphasis on Mexican symbolism and Chicano identity contributed to a growing tension with the Filipino half of the UFW, who felt that they were being sidelined in a strike they had started.

Nevertheless, by the time that the UFW's pilgrimage arrived at Sacramento, news broke that they had won their first breakthrough in the strike as Schenley Industries (which had been suffering through a four-month national boycott of its products) agreed to sign the first UFW union contract, delivering a much-needed victory.

As the strike dragged on, growers were not passively standing by - in addition to doubling down on the violence by hiring strikebreakers to assault pro-UFW farmworkers, growers turned to the Teamsters Union as a way of pre-empting the UFW, either by pre-emptively signing contracts with the Teamsters or effectively backing the Teamsters in union elections.

Part of the darker legacy of the Teamsters is that, going all the back to the 1930s, they have a nasty habit of raiding other unions, and especially during their mobbed-up days would work with the bosses to sign sweetheart deals that allowed the Teamsters to siphon dues money from workers (who had not consented to be represented by the Teamsters, remember) while providing nothing in the way of wage increases or improved working conditions, usually in exchange for bribes and/or protection money from the employers. Moreover, the Teamsters had no compunction about using violence to intimidate rank-and-file workers and rival unions in order to defend their "paper locals" or win a union election. This would become even more of an issue later on, but it started up as early as 1966.

Moreover, the growers attempted to adapt to the UFW's boycott tactics by sharing labels, such that a boycotted company would sell their products under the guise of being from a different, non-boycotted company. This forced the UFW to change its boycott tactics in turn, so that instead of targeting individual growers for boycott, they now asked unions and consumers alike to boycott all table grapes from the state of California.

By 1970, however, the growing strength of the national grape boycott forced no fewer than 26 Delano grape growers to the bargaining table to sign the UFW's contracts. Practically overnight, the UFW grew from a membership of 10,000 strikers (none of whom had contracts, remember) to nearly 70,000 union members covered by collective bargaining agreements.

1970 to 1978: The UFW Confronts Internal and External Crises

Up until now, I've been telling the kind of simple narrative of gradual but inevitable social progress that U.S history textbooks like, the Hollywood story of an oppressed minority that wins a David and Goliath struggle against a violent, racist oligarchy through the kind of non-violent methods that make white allies feel comfortable and uplifted. (It's not an accident that the bulk of the 2014 film Cesar Chavez starring Michael Peña covers the Delano Grape Strike.)

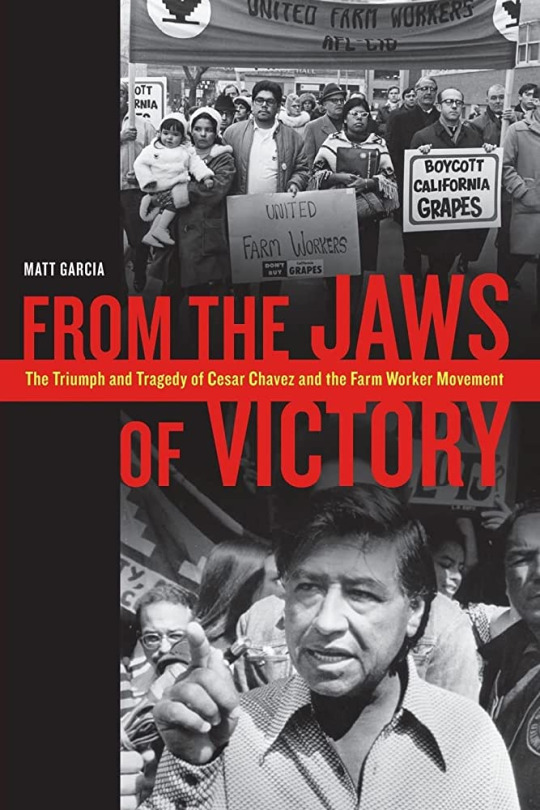

It's also the period in which the UFW's strengths as an organization that came out of the community organizing/civil rights movement were most on display. In the eight years that followed, however, the union would start to experience a series of crises that would demonstrate some of the weaknesses of that same institutional legacy. As Matt Garcia describes in From the Jaws of Victory, in the wake of his historic victory in 1970, Cesar Chavez began to inflict a series of self-inflicted injuries on the UFW that crippled the functioning of the union, divided leadership and rank-and-file alike, and ultimately distracted from the union's external crises at a time when the UFW could not afford to be distracted.

That's not to say that this period was one of unbroken decline - as we'll discuss, the UFW would win many victories in this period - but the union's forward momentum was halted and it would spend much of the 1970s trying to get back to where it was at the very start of the decade.

To begin with, we should discuss the internal contradictions of the UFW: one of the major features of the UFW's new contracts was that they replaced the shape-up with the hiring hall. This gave the union an enormous amount of power in terms of hiring, firing and management of employees, but the quid-pro-quo of this system is that it puts a significant administrative burden on the union. Not only do you have to have to set up policies that fairly decide who gets work and when, but you then have to even-handedly enforce those policies on a day-to-day basis in often fraught circumstances - and all of this is skilled white-collar labor.

This ran into a major bone of contention within the movement. When the locus of the grape strike had shifted from the fields to the urban boycotts, this had made a new constituency within the union - white college-educated hippies who could do statistical research, operate boycott houses, and handle media campaigns. These hippies had done yeoman's work for the union and wanted to keep on doing that work, but they also needed to earn enough money to pay the rent and look after their growing families, and in general shift from being temporary volunteers to being professional union staffers.

This ran head-long into a buzzsaw of racial and cultural tension. Similar to the conflicts over the role of white volunteers in CORE/SNCC during the Civil Rights Movement, there were a lot of UFW leaders and members who had come out of the grassroots efforts in the field who felt that the white college kids were making a play for control over the UFW. This was especially driven by Cesar Chavez' religiously-inflected ideas of Catholic sacrifice and self-denial, embodied politically as the idea that a salary of $5 a week (roughly $30 a week in today's money) was a sign of the purity of one's "missionary work." This worked itself out in a series of internicene purges whereby vital college-educated staff were fired for various crimes of ideological disunity.

This all would have been survivable if Chavez had shown any interest in actually making the union and its hiring halls work. However, almost from the moment of victory in 1970, Chavez showed almost no interest in running the union as a union - instead, he thought that the most important thing was relocating the UFW's headquarters to a commune in La Paz, or creating the Poor People's Union as a way to organize poor whites in the San Joaquin Valley, or leaving the union altogether to become a Catholic priest, or joining up with the Synanon cult to run criticism sessions in La Paz. In the mean-time, a lot of the UFW's victories were withering on the vine as workers in the fields got fed up with hiring halls that couldn't do their basic job of making sure they got sufficient work at the right wages.

Externally, all of this was happening during the second major round of labor conflicts out in the fields. As before, the UFW faced serious conflicts with the Teamsters, first in the so-called "Salad Bowl Strike" that lasted from 1970-1971 and was at the time the largest and most violent agricultural strike in U.S history - only then to be eclipsed in 1973 with the second grape strike. Just as with the Salinas strike, the grape growers in 1973 shifted to a strategy of signing sweetheart deals with the Teamsters - and using Teamster muscle to fight off the UFW's new grape strike and boycott. UFW pickets were shot at and killed in drive-byes by Teamster trucks, who then escalated into firebombing pickets and UFW buildings alike.

After a year of violence, reduced support from the rank-and-file, and declining resources, Chavez and the UFW felt that their backs were up against a wall - and had to adjust their tactics accordingly. With the election of Jerry Brown as governor in 1974, the UFW pivoted to a strategy of pressuring the state government to enact a California Agricultural Labor Relations Act that would give agricultural workers the right to organize, and with that all the labor protections normally enjoyed by industrial workers under the Federal National Labor Relations Act - at the cost of giving up the freedom to boycott and conduct secondary strikes which they had had as outsiders to the system.

This led to the semi-miraculous Modesto March, itself a repeat of the Delano-to-Sacramento march from the 1960s. Starting as just a couple hundred marchers in San Francisco, the March swelled to as many as 15,000-strong by the time that it reached its objective at Modesto. This caused a sudden sea-change in the grape strike, bringing the growers and the Teamsters back to the table, and getting Jerry Brown and the state legislature to back passage of California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

This proved to be the high-water mark for the UFW, which swelled to a peak of 80,000 members. The problem was that the old problems within the UFW did not go away - victory in 1975 didn't stop Chavez and his Chicano constituency feuding with more distinctively Mexican groups within the movement over undocumented immigration, nor feuding with Filipino constituencies over a meeting with Ferdinand Marcos, and nor escalating these internal conflicts into a series of leadership purges.

Conclusion: Decline and Fall

At the same time, the new alliance with the Agricultural Labor Relations Board proved to be a difficult one for the UFW. While establishment of the agency proved to be a major boon for the UFW, which won most of the free elections under CALRA (all the while continuing to neglect the critical hiring hall issue), the state legislature badly underfunded ALRB, forcing the agency to temporarily shut down. The UFW responded by sponsoring Prop 14 in the 1976 elections to try to empower ALRB, and then got very badly beaten in that election cycle - and then, when Republican George Deukmejian was elected in 1983, the ALRB was largely defunded and unable to achieve its original elective goals.

In the wake of Deukmejian, the UFW went into terminal decline. Most of its best organizers had left or been purged in internal struggles, their contracts failed to succeed over the long run due to the hiring hall problem, and the union basically stopped organizing new members after 1986.

#history#u.s history#labor history#ufw#united farm workers#cesar chavez#dolores huerta#trade unions#social history#social movements#unions

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

The class structure of capitalism encourages men who wield power in the economic and political realm to become routine agents of sexual exploitation. The present rape epidemic occurs at a time when the capitalist class is furiously reasserting its authority in face of global and internal challenges. Both racism and sexism, central to its domestic strategy of increased economic exploitation, are receiving unprecedented encouragement. It is not a mere coincidence that as the incidence of rape has arisen, the position of women workers has visibly worsened. So severe are women's economic losses that their wages in relationship to men are lower than they were a decade ago. The proliferation of sexual violence is the brutal face of a generalized intensification of the sexism which necessarily accompanies this economic assault.

Following a pattern established by racism, the attack on women mirrors the deteriorating situation of workers of color and the rising influence of racism in the judicial system, the educational institutions and in the government's posture of studied neglect toward Black people and other people of color. The most dramatic sign of the dangerous resurgence of racism is the new visibility of the Ku Klux Klan and the related epidemic of violent assaults on Blacks, Chicanos, Puerto Ricans and Native Americans. The present rape epidemic bears an extraordinary likeness to this violence kindled by racism.

Given the complexity of the social context of rape today, any attempt to treat it as an isolated phenomenon is bound to founder. An effective strategy against rape must aim for more than the eradication of rape—or even of sexism—alone. The struggle against racism must be an ongoing theme of the anti-rape movement, which must not only defend women of color, but the many victims of the racist manipulation of the rape charge as well. The crisis dimensions of sexual violence constitute one of the facets of a deep and ongoing crisis of capitalism. As the violent face of sexism, the threat of rape will continue to exist as long as the overall oppression of women remains an essential crutch for for capitalism. The anti-rape movement and its important current activities—ranging from emotional and legal aid to self-defense and educational campaigns—must be situated in a strategic context which envisages the ultimate defeat of monopoly capitalism.

—Angela Davis, Women, Race & Class (1981), p 200-201

#god I wish the feminism that exploded in past decades was based on angela davis she was right about so many things#angela davis#misogyny#racism#antiblackness#misogynoir

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chicano park day

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big City Greens Plants Season 4 Premiere For September 23 on Disney Channel + Guest Cast List

Bingo Bango! Disney Branded Television has set primetime premieres for Big City Greens Season 4 slated to debut Saturday September 23 at 8:00PM EST only on Disney Channel and streaming October 25 only on Disney+.

The episodes airing on September 23 – 'Truck Stopped / Jingled' – have "Tilly and Cricket wrestle with indecision at a truck stop between Big City and the country" in the former, while the latter sees Tilly becoming a Big City jingle writer and rising through the ranks. In addition to premiering on Disney Channel, episodes will also be added to Disney Plus on October 25, 2023.

Guest Stars on Season 4 include musican Michael Bolton as Rick Razzle on Jingled where Tilly wants to become a Big City jingle writer and rising through the ranks. Other guest stars for Season Four include June Diane Raphael (Marvel "Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur"), Tom Green ("The Tom Green Show"),NHL player Brad Marchand,Margo Martindale (Sony Pictures "Cocaine Bear"),podcaster Justin McElroy, Tim Meadows (ABC Network "The Goldbergs"), Dean Norris (AMC "Breaking Bad", "Better Call Saul"), Comedian Ms. Pat, Amy Seradis (Netflix "Bojack Horseman", Lucasfilm "The Mandalorian") and comedian Trevor Wallace.

Since it's debut on 2018, Big City Greens has been one of Disney Television Animation recent hits with multiple shorts, a NHL game -themed broadcast special in collaboration with ESPN and a animated feature film based on the series is on production slated for a 2024 release, the series spawned a new legacy of Disney TVA creators like Natasha Kline with chicano lead-driven animated comedy series "Primos" slated for 2024 and more animated shows on development for Disney Channel by Big City Greens Alumnis. (Cheyenne Curtis,Monica Ray, Amy Hudkins,Raj Bruggemann and Houghton Brothers mentor C.H Greenblatt) who will be getting series orders in the coming months.

The new season will include the show's 100th episode, which is a major landmark for any animated series, but especially for a Disney Channel series with few ever making it quite that far.

"Season four is pure insanity," says Chris Houghton, Big City Greens co-creator and executive producer. "Tilly becomes a commercial jingle-writer, Cricket tries stand-up comedy, Bill loses his mind like six times, and Gramma dabbles in minimalism. The fact that we have such a fun arena to play in when it comes to these characters is not lost on us or our crew. Even though we’ve told so many stories with these characters, this season feels fresher than ever."

"There are some very funny and silly episodes in this season," adds Shane, "like 'Handshaken' where country folks act like western gunslingers, but assert their power through firm handshakes. There are also a few emotional episodes that reach out and give your heart a good squeeze – 'Family Tree' is one that makes me tear up every time I watch a cut of it. And biggest of all, Chip Whistler is back! This season may have more action, adventure, and thrills than any previous season! And here's a couple rapid-fire teases you’ll see in season four: Gloria hires a new café employee, Vasquez goes to therapy, and the kids meet a long lost family member."

Additionaly Big City Greens will continue with new shorts trought the Disney TVA multi-platform division trought Chibi Tiny Tales, Broken Karaoke,Theme Song Takeover, How NOT To Draw & Random Rings.

Big City Greens characters will continue to host on the Disney Television Animation's crossover compilation series "Chibiverse" as it's second season is slated to debut Saturday September 23.

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

did you ever finish your South Texas thriller story? I remember seeing something about it on twitter a while ago and was just thinking about it!!! would love to read it!

AHHHH that story!!! This just sent me running to dig it out of my files and I'm reading through it and laughing so hard. It's unfinished ! I wrote about 3 chapters while I was querying ABM for traditional publishers all the way back in 2022 ! When I decided to self-publish, I became really busy with ABM and put that book on the back burner and now it's basically dead! I'll explain why in a sec.

For anyone curious, this was the pitch!

The book was about a 19 yr old, undocumented construction worker (named Maximiliano) who is working on the backyard of an Anglo-American/White family who just moved into town. Inside, there's a blonde boy his age (Vincent) who (after revealing that he learned every detail of Maximiliano's life) offers him money in exchange for his help murdering his billionaire father. Maximiliano needs the money and is worried about Vincent getting him deported if he rejects, so he agrees. (They are also weirdly attracted to each other). The fun part of the book is that the murder itself is easy, and the majority of the story follows the bizarre consequences of killing a Very powerful man.

The book was also incredibly funny and included me getting to write in goofy Chicano colloquialisms (not pictured here but there's also a use of no quema cuh, which... iykyk):

I stopped working on the book when I realized how niche it was (it's about queer latines of mixed legal status along the US-Mex border) and I doubted I'd be able to sell it to a publisher, which I still cared about at the time. I can see the story lived on, in a way, through my story Midnight Invitation, which is also about class and race and colonialism/imperialism, and a very troubled relationship between a racialized worker/white landowner.

That said, I'm skimming this story and think about how crazy and fun it is. I don't know if I could return to it now that I've written Midnight Invitation, but I'm really sad I felt I had to abandon it.

At least now I'm comfy writing whatever I want.

#i still have the moodboard for this!! agh#i was also scared of being so overtly political back then I think#which was tied to my fear of tradpublishing#but ah well#im really sad i killed this story#maybe ill bring it back to life somehow....#mine#ask#writing

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's to a fresh intro! I'm Verne (they/them), practically a queer elder in my 30s and too many of my stories are me simply wanting to write a scene, developing a bit of a world around it, then losing interest entirely. I’m still trying to figure out how to break that curse, but in the meantime, I’m just going to chase inspiration and post odds and ends here. I used to be an avid role-player, and my small cast of OCs from those days provide the greatest and easiest inspiration - particularly in the setting of the Fallout Universe. I do my best to write for a reader who is unfamiliar with the series, though.

Interests:

Post-apocalyptic

Near-future dystopias

Scifi/Fantasy (urban) and magical realism

History/AltHistory (especially lesser-known and marginalized stories)

Horror, dark, violent, and mature themes

Queer everything. I can't write heteros to save my life and I'm not all that sorry about it.

Sexy melodrama and smut with too much plot

Fanfiction (I could read/write Fallout stuff all day)

________________________________________________

Noteworthy WIPs:

Bad Blood - A Fallout Nuka-World fanfic (tag: #ntzsche Nuka-World)

I hope to eventually write this comprehensively enough to post on AO3 but for now, I work on this story to practice becoming a better writer. Incomplete Prequel: Sanctuary.

Lafayette, the son of a 'retired' raider, left his abusive father to find his place in the world and was taken in by an eclectic trauma-bonded found family that inspires him to be a better person and shows him love he is certain he doesn't deserve. When his father comes across them in a raid, Lafayette joins him in order to save the settlement and his little brother. Lafayette finds that being with his dad again, and playing the son he always wanted him to be, isn't nearly as difficult as he thought it would be. He struggles to maintain the person he wants to be with the person he suspects he is, all while a cast of scheming raiders, wastelanders, and slaves vie for power in a raider city built within the rusted remains of an amusement park.

Salem's Child - (tag: #ntzsche Salem)

A background on one of the lesser Bad Blood characters that I got carried away with.

Andrew Rook doesn't look like his parents. He looks like someone they are desperate to forget. The witchy remains of post-apocalyptic Salem, Massachusetts provide some solace from his rough home life. In a fading settlement run by incompetent adults who would rather blame the population of feral black cats for their problems than try to resolve them, Andrew and his two best friends build a world in their imagination that shields them from the wretchedness of the wasteland and the people they have to rely on to survive.

Navarro (working title) - (tag: #ntzsche Zavala)

Multi-generational short stories. Inspired heavily by Fallout universe, but reads as a stand-alone. Temporarily on hold pending a sensitivity beta reader for a few of the stories.

María Zavala, an aging curandera, happily sacrifices her place in a vault to her pregnant chicano daughter and faces the nuclear apocalypse alone. When radiation blesses her with immortality, she survives long enough for her great-grandchild to come home to her, and the family finds a way to flourish against great odds. Under their immortal matriarch, her descendants become the foundation for a town that is a bastion in an otherwise inhospitable world.

The Crash - (tag: #ntzsche Crash)

A real-world AU.

Gabe always knew his functional alcoholic roomie would get into a terrible car wreck someday, but he never thought he would be dumb enough to be in the car with him. When the consequences of the wreck threaten to destroy Dave's life, Gabe finds himself doing everything he can to hold those pieces together. The love he harbors for his straight, polyamorous best friend runs deeper than either of them are ready to face, but Dave's injury makes it that much harder to hide.

________________________________________________

Miscellaneous

Master list of writing posts, mostly backstories, one-shots, and excerpts (tag: #ntzsche misc).

Every You and Every Me - Cosmic horror flash-fiction

Misc Fallout Fiction

Typically taking place before the events of Bad Blood, roughly in chronological order:

Smiling Jack - Backstory for Dizz

Vault 112 - Backstory for Dave and Gabe

If Dave Had Died - What-if scenario from prior to Sanctuary

Sanctuary - How Lafayette became a part of his new family, direct prequel to Bad Blood

The Boston Library - One-shot writing prompt containing Lafayette and Luvell, after Sanctuary

OC Intro - most of my recurrent OCs have their own tags.

(some links forthcoming)

#writeblr#writeblr intro#my writing#fallout fic#creative writing#writing#ao3#queer writers#lgbtq writer#wip#wip exerpt#current wip

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

introductory excerpts on COINTELPRO

it came to my awareness that some folks don't know what COINTELPRO is still, so imma drop some excerpts from the wikipedia page. ofc there are a billion other resources you can check out, especially firsthand accounts, but this is always a good place to start! link attached below:

[Note that the embedded link above's photo has the following caption: "COINTELPRO memo proposing a plan to expose the pregnancy of actress Jean Seberg, a financial supporter of the Black Panther Party, hoping to "possibly cause her embarrassment or tarnish her image with the general public". Covert campaigns to publicly discredit activists and destroy their interpersonal relationships were a common tactic used by COINTELPRO agents."]

The Introduction:

COINTELPRO (syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program; 1956–1971) was a series of covert and illegal[1][2] projects actively conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting domestic American political organizations.[3][4] FBI records show COINTELPRO resources targeted groups and individuals the FBI[5] deemed subversive,[6] including feminist organizations,[7][8] the Communist Party USA,[9] anti–Vietnam War organizers, activists of the civil rights and Black power movements (e.g. Martin Luther King Jr., the Nation of Islam, and the Black Panther Party), environmentalist and animal rights organizations, the American Indian Movement (AIM), Chicano and Mexican-American groups like the Brown Berets and the United Farm Workers, independence movements (including Puerto Rican independence groups such as the Young Lords and the Puerto Rican Socialist Party), a variety of organizations that were part of the broader New Left, and white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan[10][11] and the far-right group National States' Rights Party.[12]

Methods COINTELPRO Utilized

According to attorney Brian Glick in his book War at Home, the FBI used five main methods during COINTELPRO:

Infiltration: Agents and informers did not merely spy on political activists. Their main purpose was to discredit, disrupt and negatively redirect action. Their very presence served to undermine trust and scare off potential supporters. The FBI and police exploited this fear to smear genuine activists as agents.

Psychological warfare: The FBI and police used a myriad of "dirty tricks" to undermine movements. They planted false media stories and published bogus leaflets and other publications in the name of targeted groups. They forged correspondence, sent anonymous letters, and made anonymous telephone calls. They spread misinformation about meetings and events, set up pseudo movement groups run by government agents, and manipulated or strong-armed parents, employers, landlords, school officials, and others to cause trouble for activists. They used bad-jacketing to create suspicion about targeted activists, sometimes with lethal consequences.[74]

Harassment via the legal system: The FBI and police abused the legal system to harass dissidents and make them appear to be criminals. Officers of the law gave perjured testimony and presented fabricated evidence as a pretext for false arrests and wrongful imprisonment. They discriminatorily enforced tax laws and other government regulations and used conspicuous surveillance, "investigative" interviews, and grand jury subpoenas in an effort to intimidate activists and silence their supporters.[73][75]

Illegal force: The FBI conspired with local police departments to threaten dissidents; to conduct illegal break-ins in order to search dissident homes; and to commit vandalism, assaults, beatings and assassinations.[73] The objective was to frighten or eliminate dissidents and disrupt their movements.

Undermine public opinion: One of the primary ways the FBI targeted organizations was by challenging their reputations in the community and denying them a platform to gain legitimacy. Hoover specifically designed programs to block leaders from "spreading their philosophy publicly or through the communications media". Furthermore, the organization created and controlled negative media meant to undermine black power organizations. For instance, they oversaw the creation of "documentaries" skillfully edited to paint the Black Panther Party as aggressive, and false newspapers that spread misinformation about party members. The ability of the FBI to create distrust within and between revolutionary organizations tainted their public image and weakened chances at unity and public support.[49]

The FBI specifically developed tactics intended to heighten tension and hostility between various factions in the black power movement, for example between the Black Panthers and the US Organization. For instance, the FBI sent a fake letter to the US Organization exposing a supposed Black Panther plot to murder the head of the US Organization, Ron Karenga. They then intensified this by spreading falsely attributed cartoons in the black communities pitting the Black Panther Party against the US Organization.[49] This resulted in numerous deaths, among which were San Diego Black Panther Party members John Huggins, Bunchy Carter and Sylvester Bell.[73] Another example of the FBI's anonymous letter writing campaign is how they turned the Blackstone Rangers head, Jeff Fort, against former ally Fred Hampton, by stating that Hampton had a hit on Fort.[49] They also were instrumental in developing the rift between Black Panther Party leaders Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton, as executed through false letters inciting the two leaders of the Black Panther Party.[49]

...

In order to eliminate black militant leaders whom they considered dangerous, the FBI is believed to have worked with local police departments to target specific individuals,[78] accuse them of crimes they did not commit, suppress exculpatory evidence and falsely incarcerate them. Elmer "Geronimo" Pratt, a Black Panther Party leader, was incarcerated for 27 years before a California Superior Court vacated his murder conviction, ultimately freeing him. Appearing before the court, an FBI agent testified that he believed Pratt had been framed, because both the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department knew he had not been in the area at the time the murder occurred.[79][80]

...

In 1969 the FBI special agent in San Francisco wrote Hoover that his investigation of the Black Panther Party had concluded that in his city, at least, the Panthers were primarily engaged in feeding breakfast to children. Hoover fired back a memo implying the agent's career goals would be directly affected by his supplying evidence to support Hoover's view that the Black Panther Party was "a violence-prone organization seeking to overthrow the Government by revolutionary means".[84]

Hoover supported using false claims to attack his political enemies. In one memo he wrote: "Purpose of counterintelligence action is to disrupt the Black Panther Party and it is immaterial whether facts exist to substantiate the charge."[85]

Intended Effects of COINTELPRO

The intended effect of the FBI's COINTELPRO was to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, or otherwise neutralize" groups that the FBI officials believed were "subversive"[58] by instructing FBI field operatives to:[59]

1. Create a negative public image for target groups (for example through surveilling activists and then releasing negative personal information to the public)

2. Break down internal organization by creating conflicts (for example, by having agents exacerbate racial tensions, or send anonymous letters to try to create conflicts)

3. Create dissension between groups (for example, by spreading rumors that other groups were stealing money)

4. Restrict access to public resources (for example, by pressuring non-profit organizations to cut off funding or material support)

5. Restrict the ability to organize protest (for example, through agents promoting violence against police during planning and at protests)

6. Restrict the ability of individuals to participate in group activities (for example, by character assassinations, false arrests, surveillance)

When did they start?

Centralized operations under COINTELPRO officially began in August 1956 with a program designed to "increase factionalism, cause disruption and win defections" inside the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Tactics included anonymous phone calls, Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits, and the creation of documents that would divide the American communist organization internally.[9] An October 1956 memo from Hoover reclassified the FBI's ongoing surveillance of black leaders, including it within COINTELPRO, with the justification that the movement was infiltrated by communists.[31] In 1956, Hoover sent an open letter denouncing Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a civil rights leader, surgeon, and wealthy entrepreneur in Mississippi who had criticized FBI inaction in solving recent murders of George W. Lee, Emmett Till, and other African Americans in the South.[32] When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an African-American civil rights organization, was founded in 1957, the FBI began to monitor and target the group almost immediately, focusing particularly on Bayard Rustin, Stanley Levison, and eventually Martin Luther King Jr.[33]

How did the news get out about COINTELPRO?

The program was secret until March 8, 1971, when the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI burgled an FBI field office in Media, Pennsylvania, took several dossiers, and exposed the program by passing this material to news agencies.[1][54] The boxing match known as the Fight of the Century between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier in March 1971 provided cover for the activist group to successfully pull off the burglary. Muhammad Ali was a COINTELPRO target because he had joined the Nation of Islam and the anti-war movement.[55]

Many news organizations initially refused to immediately publish the information, with the notable exception of The Washington Post. After affirming the reliability of the documents, it published them on the front page (in defiance of the Attorney General's request), prompting other organizations to follow suit. Within the year, Director J. Edgar Hoover declared that the centralized COINTELPRO was over, and that all future counterintelligence operations would be handled case by case.[56][57]

#reaux speaks#black panther party#fbi corruption#cointelpro#counterinsurgency#revolution#martin luther king jr#black power#intersectional feminism#indigenous#young lords#history#wikipedia#communism#socialism#j edgar hoover#mccarthyism

91 notes

·

View notes

Photo

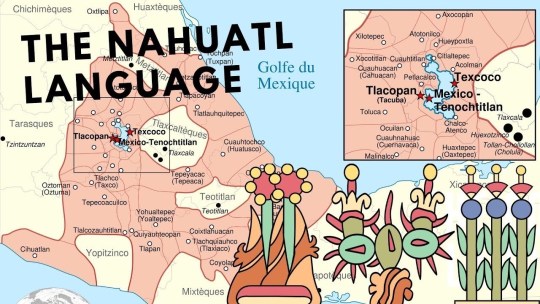

Chicano or Chicana is a chosen identity for many Mexican Americans in the United States.

Chicano was a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was first reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco subculture. By the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed to express political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of Indigenous descent (with many using the Nahuatl language).

Chicano developed its own meaning separate from Mexican American identity. Chicano Movement leaders expressed solidarity with the African political struggle and collaborated with the Black Power movement. Chicano youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into whiteness and embraced their own identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance.

Prominent journalist Rubén Salazar defined a Chicano as "a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself

In Mexico's Indigenous regions, Indigenous people refer to members of the non-indigenous majority as mexicanos, referring to the modern nation of Mexico. Among themselves, the speaker identifies by their pueblo (village or tribal) identity, such as Mayan, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huastec, or any of the other hundreds of indigenous groups. A newly emigrated Nahuatl speaker in an urban center might have referred to his cultural relatives in this country, different from himself, as mexicanos, shortened to Chicanos or Xicanos.

#mixtec#huatec#mayan#zapotec#chicanos#xicanos#mexican#mexico#nahuatl#kemetic dreams#asian#asian american

139 notes

·

View notes