#deranged alignment charts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

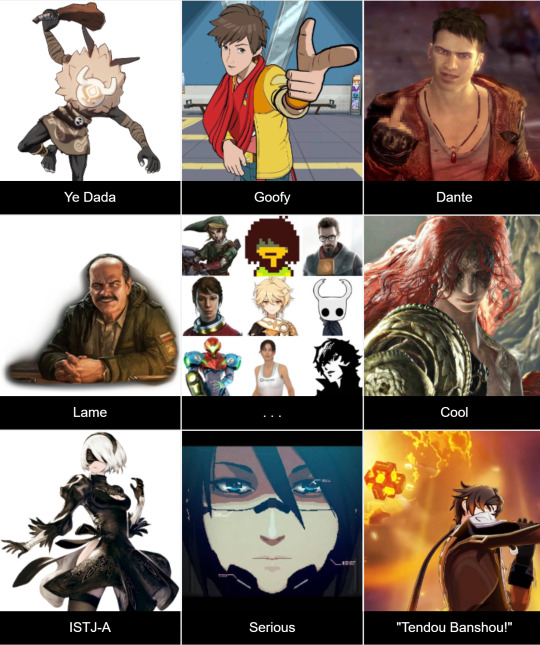

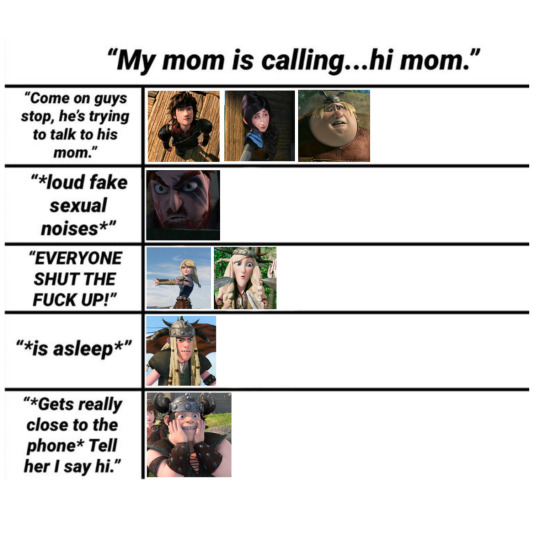

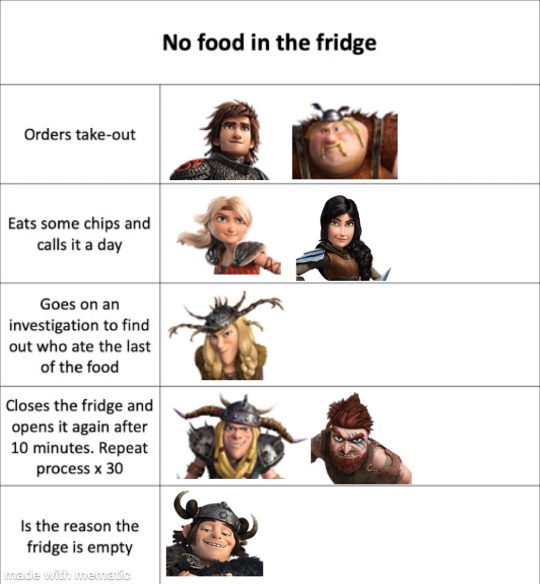

i don’t remember the last time i’ve made one of these bad boys

it’s been too long 😔

#httyd#how to train your dragon#httyd fandom#httyd rtte#race to the edge#httyd race to the edge#httyd franchise#hiccup horrendous haddock lll#astrid hofferson#tuffnut thorston#ruffnut thorston#ruff and tuff#snotlout jorgenson#fishlegs ingerman#heather the unhinged#dagur the deranged#httyd meme#httyd alignment chart#alignment chart#httyd memes

310 notes

·

View notes

Text

finally getting around to HHhH and feeling simultaneously sort of charmed and genuinely confronted by this reading experience……..mister binet what are you cooking

#a very funny text to put in conversation with band of brothers#ginning up some kind of deranged rpf alignment chart#hhhh on the top left containing as much real person and as little fiction as possible#band of brothers real person neutral fiction purist etc etc

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BUNGOU STRAY DOGS ALIGNMENT CHART DEBATE - ROUND 2

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

MY NAOYA AGENDA IN GENERAL

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just want to let you know that your tortured poets dept. Kuroko edits have forever altered my brain chemistry. The Prophecy??!!! I look in people’s WINDOWS???? So Long, London……you just get me I feel

ttpd is so Kuroko Tetsuya-coded I’m not even joking. Like I’m deranged and can associate nearly any song with fictional characters (especially t swift’s) but my god when ttpd came out, I wasn’t even that deep in my knb brainrot but the album activated my Kuroko Tetsuya angst ugh. 🩵

One day I will make my silly little Taylor album/Kuroko character alignment chart, but again ttpd is such a good album for him. Captures his poetic melancholy and sass perfectly.

#MWAH thank you for the delicious message#I’m so glad you like the edits 🩵🩵#makes me wanna make more……..#wannabespeaks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

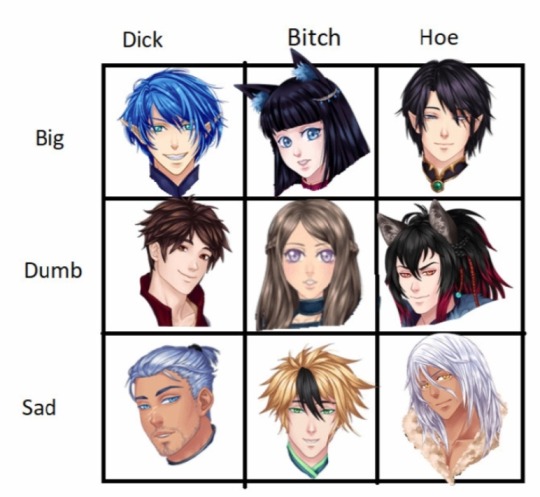

#eldarya#lance eldarya#unhinged#valkyon#eldarya erika#eldarya leiftan#nevra#eldarya nevra#ezarel#eldarya ezarel#eldarya mathieu#mathieu eldarya#eldarya miiko#deranged alignment charts

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

#httyd#httyd alignment chart#allignment chart#astrid hofferson#astrid#hiccup#hiccup haddock#fishlegs#fishlegs ingerman#snotlout#ruffnut thorston#ruffnut#tuffnut#tuffnut thorston#heather#dagur#dagur the deranged#viggo grimborn#httyd viggo#incorrect httyd quotes#alvin

931 notes

·

View notes

Text

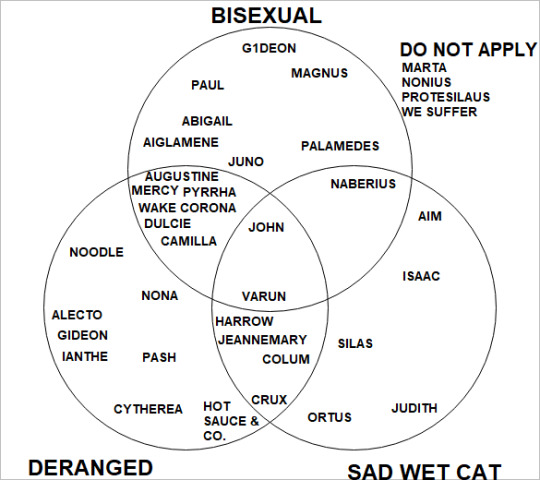

consulted only my beautiful mind for this venn diagram (criteria credit to @copepods)

(marta, nonius, & we suffer are lesbians and too sensible and cool to apply, and pro was too sensible to be involved in any of this in the first place)

#my post#fuck off lou#tlt#the locked tomb#alignment chart#character alignment chart#bisexual v. deranged v. sad wet cat#harrowhark nonagesimus#gideon nav#ianthe tridentarius#alecto tlt#nona tlt#john gaius#pyrrha dve#commander wake#augustine the first#mercymorn the first#cytherea the first#camilla hect#palamedes sextus#this is personal opinion but i also think it's funny

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

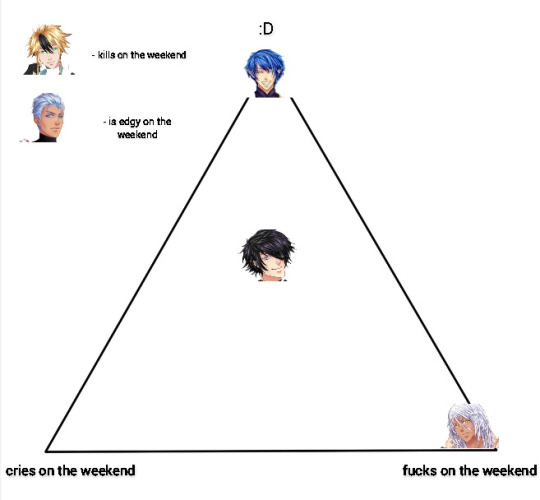

I don’t feel like I have to explain

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

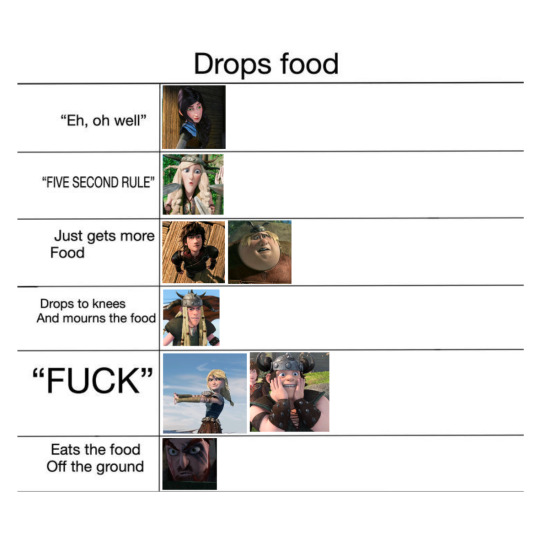

ehehehe

click so you can read em

#httyd#how to train your dragon#httyd rtte#httyd movies#httyd fandom#race to the edge#snotlout jorgenson#hiccup haddock#astrid hofferson#dagur and heather#heather the unhinged#fishlegs ingerman#dagur the deranged#ruffnut thorston#tuffnut thorston#httyd race to the edge#rtte#hiccup#httyd meme#alignment chart

621 notes

·

View notes

Note

i think it might be worth rerunning a couple of the alignment polls in light of recent plot twists. specifically fukuchi gave me the idea bc his poll had a great majority toward deranged back in june but now i believe strong arguments could be made for all three categories

While this is understandable, there are two reasons we won't be doing that.

If we were to rerun every character that received development in Season 5, we'd end up rerunning half the polls. Little peak behind the curtain here, we're currently rerunning 11 polls due to ties in the original polling, and it took us an hour to prep all that, and we have to be here, as the polls launch, to make sure that nothing goes wrong and so that we can update the directory as the polls come out, which is another hour of work. While a lot of this is self imposed, a lot of this also assures quality, which overachieving Smore Mod here would not run this account without.

Smore Mod here is also heavily biased, and the partner I started this account with hasn't messaged me in half a year for seemingly no reason, so we have no checks and balances system. Smore Mod still agrees with the Deranged ruling on Fukuchi because Smore Mod still greatly hates Fukuchi, even knowing what we do in a post Season 5 era. And thus we will not be rerunning his poll.

Apologies if this is not the answer you wanted, but we also do intend to not abandon this account again, so if you have ideas for other alignment charts, or generally, anything to do with BSD that could be made into a poll, we'd be glad to hear suggestions, and there's a high chance we'd run those polls in the future.

3 notes

·

View notes

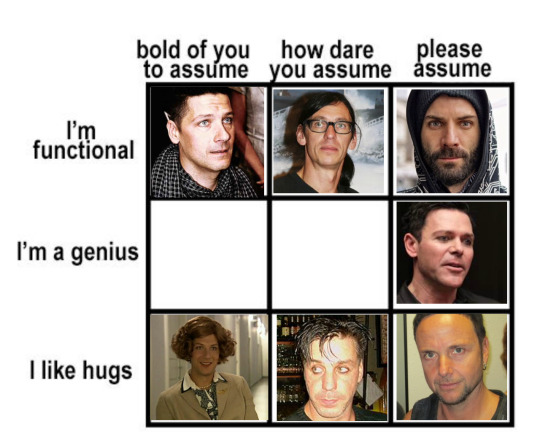

Photo

#rammstein#rammstein meme#shitpost#rammstein alignment charts that don't include frau schneider are invalid#christoph schneider#frau schneider#till lindemann#richard kruspe#rzk#paul landers#flake lorenz#oliver riedel#just imagine frau schneider with that exact facial expression saying Bold of you to assume I like hugs#that deranged-looking smile#what a menace <3

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Josh Allen Dates in His League

It’s not a competition. But I win the title of biggest Hailee Steinfeld fan. I even vaguely know why she's famous. The voice of Gwen Stacy is now Buffalo’s First Lady as if nerds weren’t already envious of our de facto executive. Like Jerry Seinfeld when Elaine’s dating Keith Hernandez, I’m jealous of everybody.

I made sure to spell her name correctly to flaunt my dedication. Copying and pasting was a worthwhile investment this past weekend that taught me through repetition. As an expert on her career, I’ve known how to type her name correctly without checking for a few days now. If I got it wrong, I would have to pretend it was a joke about ignorance of her oeuvre. Simultaneously, I now don’t care for our quarterback’s ex whatshername, a free agent who can date a Patriot.

Hailee is an actress and singer, according to information I totally didn’t just glean from her Wikipedia. My expertise on all things Buffalo Bills extends to learning why she’s famous. An actress and pop star dates a fellow double threat.

A transaction can alter perception. Buffalonians suddenly prefer the True Grit remake to the original, which is a matter of taste and not that the city’s most beloved dreamboat is courting one of its stars. I also now have an opinion about the Pitch Perfect movie series, which may seem weird but is not much different than thinking Dalton Kincaid is just the sort of player I want to cheer for right as he’s drafted.

Life can change in a moment. Take how her ubiquitously incessant hit Starving used to infiltrate my brain and play on a loop as a cruel joke from an uncaring universe that didn’t care how my thoughts weren’t something I wanted to think. But I now welcome encountering her emblematically classic tune that puts anything Verdi wrote to shame. What was earlier in the month an incessant torment that offered a preview of eternal damnation has become a chance to experience transcendent musical genius repeatedly.

In particular, the once-curious line expressing fondness by informing the singer's partner that she “Don’t need no butterflies when you give me the whole damn zoo” is now worthy of Westerberg. Like trying to look past Terrell Owens’s myriad transgressions, we seek the upside of new allies.

Learning about who Josh Allen dates is my new offseason hobby. Taking a very not creepy interest in his time away from work is just another way of showing appreciation. We swear it’s dedicated and not deranged.

Caring about the doings of admired athletes shows thoroughness. That's why I found myself interested in what bank Stefon Diggs thought was best for me. Caring about a certain update just because a particular person is involved applies to celebrity endorsements of corporations or relationships.

Steinfeld could become even more beloved in her adopted homeland if she affects play in one direction. A glamorous pairing is ideally part of a fully happy life. Allen doesn’t seem like the type who finds focus in anguish like a miserable single writer who uses personal desolation to mine material and a grudge. Fellow AFC East quarterback Aaron Rodgers has gone through a handful of romantic affiliations involving ladies with popular Instagram accounts, which could be a trend worth following.

Star power should only be the main attraction when it’s on the field. But it's nice to recognize fellow backers from somewhere other than Wegmans. Monitoring which humans we know are sitting in suites is the result, not the goal. The urge to align with success applies to allurement just like it does athletics. It’s a good problem to determine who’s hopped on the bandwagon.

Following sports is already bizarre. Zealots care more than anything about who moves a ball forward better. Worrying intently about ligaments of people we may never meet has come to feel normal. Wondering about partners is the next natural step in its way.

I blame the calendar for my Tiger Beat tendencies. Charting wooing is a byproduct of just how much time fans must fill between play. But even a 40-game NFL season would still feature some days between them. Thinking about where players are taking flames to dinner creates a break from thinking about the next touchdown’s form.

Post this on Page Six. Allen is turning football columns into gossip forums. Someone with multiple talents is dating Steinfeld. It’s a sign of just how much attention he draws that Hailee groupies who might not be able to explain a zone blitz know she’s going out with some football guy.

Questions about the upcoming season revolve around play-calling direction. I wonder when will we found out Hailee’s favorite pizza parlor. The answer could endear her even further to Erie County’s residents and enthusiasts. A quarterback succeeding in multiple ways enjoys time with a new beau in between playing cornerback at OTAs. Welcoming her as family is how we can make her feel at home. Does she like football?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#eldarya erika#eldarya#lance eldarya#unhinged#eldarya leiftan#leiftan#nevra#deranged alignment charts

75 notes

·

View notes

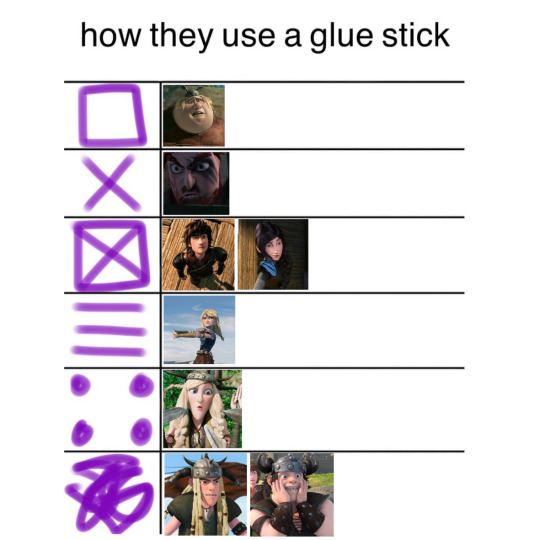

Text

#lol sorry I have so many of these in my camera roll#httyd#httyd alignment chart#hiccup#hiccup haddock#astrid hofferson#astrid#tuffnut#tuffnut thorston#ruffnut#ruffnut thorston#dagur#dagur the deranged#heather#fishlegs#fishlegs ingerman#snotlout#rtte#incorrect httyd quotes

641 notes

·

View notes