#linguistic prescriptivism

Text

Maybe I'm just a weirdo with Opinions™ about linguistic prescriptivism but like, I really, REALLY hate autocorrect for how it nags at people to talk a certain way in online spaces, or tells them that their language isn't "legitimate" enough to pass without a glaring red underline

#this is about google telling me that neurodivergent isn't a word but it applies to lots of other contexts#linguistics#linguistic prescriptivism#let people talk how they want to talk

227 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fjslksjdfj I got that you're femme on pure vibes alone, not any specific thing. Though, I guess you'd be more futch than anything?

I was going to ask "ooh tell me more, what vibes??" but I have instead been staring at the word "futch" for several minutes while making increasingly sad noises. Who invented that word, and who hurt them

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

People are always complaining about shifts in grammar feeling wrong to them, but when I was a kid it was still considered an error in formal English to apply the possessive pronoun to inanimate objects – i.e., you couldn't say "any die whose value is X", you had to say "a die the value of which is X" – and people pulling the stick out of their collective ass over that one is literally the best thing that ever happened to me.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

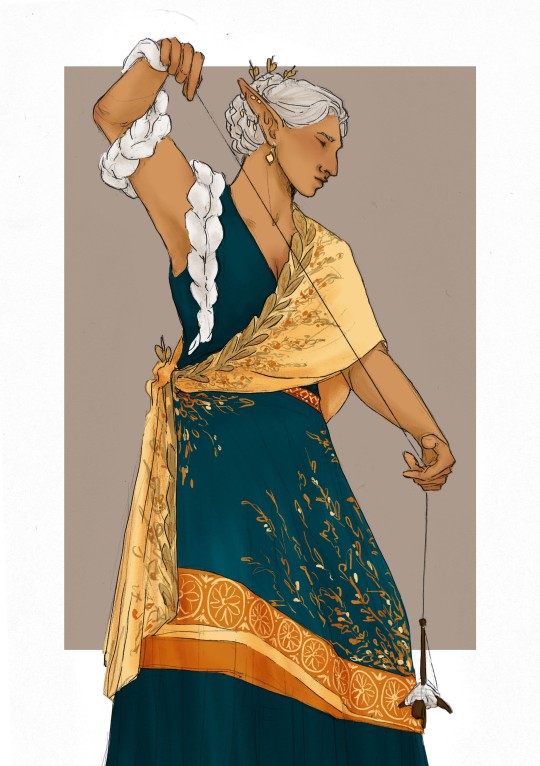

turkish spindle gang make some noise (imagine having to wind your singles off your spindle before you can start plying, couldn't be us)

#miriel therinde#tolkien fanart#silmarillion fanart#massive self-report here this is actually how i spin. distaff arm fully over the head and all.#subcreation#aggressive linguistic prescriptivism#(that's the fiber arts tag þerindë or bust motherfuckers)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Linguistic Prescriptivists: You can't say that! That's not grammatically corre—

Me: I have altered the language. Save your prayers, I will absolutely be altering it further.

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

But by the end of my five years [as a copy editor], I felt intellectually and psychologically worn down by the labor I logged on my biweekly timesheets. Whatever roller-rink of neurons helped me spot aberrations from convention had grown practiced and strong, and it was difficult to read any unconventional sentence without reflexively rearranging it into a more conventional form.

Something had shrunken and withered in me, for having directed so much of my attention away from the substance of the stories I read and into their surface. Few people in our office, let alone outside its walls, would notice the variation in line spacing, the fact that Jesus’ was lacking its last, hard “s,” or whatever other reason we were sending the proofs to be printed again—and if they did, who the fuck cared? [....]

I can’t help wondering, though, whether there wasn’t something insidious in the way we worked—some poison in our many rounds of minute changes, in our strained and often tense conversations about ligatures and line breaks, in our exertions of supposedly benign, even benevolent, power; if those polite conversations constituted a covert, foot-dragging protest against change, an insistence on the quiet conservatism of the liberal old guard, and if they were a distraction from the conversations that might have brought meaningful literary or linguistic change about. In fact, I sense myself enacting the same foot-dragging here.

It’s fun—it’s dangerously pleasing—to linger in the minutiae of my bygone copyediting days, even if, by the time I left that job to teach college writing full-time, I was convinced that “correcting” “errors” of convention most readers would never notice was the least meaningful work a person could possibly do. I’m writing this, however, to ask whether copyediting as it’s been practiced is worse than meaningless: if, in fact, it does harm.

*

Do we really need copyediting? I don’t mean the basic clean-up that reverses typos, reinstates skipped words, and otherwise ensures that spelling and punctuation marks are as an author intends. Such copyediting makes an unintentionally “messy” manuscript easier to read, sure.

But the argument that texts ought to read “easily” slips too readily into justification for insisting a text working outside dominant Englishes better reflect the English of a dominant-culture reader—the kind of reader who might mirror the majority of those at the helm of the publishing industry, but not the kind of reader who reflects a potential readership (or writership) at large.

A few years before leaving copyediting, I began teaching a scholarly article I still read with students today, Lee A. Tonouchi’s “Da State of Pidgin Address.” Written in Hawai’ian Creole English, or Pidgin, it asks whether what “dey say” is true: “dat da perception is dat da standard english talker is going automatically be perceive fo’ be mo’ intelligent than da Pidgin talker regardless wot dey talking, jus from HOW dey talking.” The article leaves many students questioning the assumptions they began reading it with: its effect is immediate, personal, and profound.

In another article I pair it with, “Should Writers Use They Own English,” Vershawn Ashanti Young answers Tonouchi’s implicit question, writing, “don’t nobody’s language, dialect, or style make them ‘vulnerable to prejudice.’ It’s ATTITUDES.” Racial difference and linguistic difference, Young reminds us, are intertwined, and “Black English dont make it own-self oppressed.”

It’s clear that copyediting as it’s typically practiced is a white supremacist project, that is, not only for the particular linguistic forms it favors and upholds, which belong to the cultures of whiteness and power, but for how it excludes or erases the voices and styles of those who don’t or won’t perform this culture. Beginning with an elementary school teacher’s red pen, and continuing with agents, publishers, and university faculty who on principle turn away work that arrives on their desk in unconventionally grammatical or imperfectly punctuated form, voices that don’t mimic dominance are muffled when they get to the page and also before they get there—as schools, publishers, and their henchmen entrench the idea that those writing outside convention are not writing “well,” and therefore ought not set their voices to paper at all. [...]

Like other emissaries of the powerful (see, e.g., the actual police), copy editors often wield what power they do have unpredictably, teetering between generous attention and brute, insistent force. You saw this in the way our tiny department got worked up over the stubbornness of an editor or author who had dug in their heels: their resistance was a threat, sometimes to our suspiciously moral-feeling attachment to “correctness,” sometimes to our aesthetics, and sometimes to our sense of ourselves. [...]

There’s a flip side, if it’s not already obvious, to the peculiar “respect” I received in that dusty closet office at twenty-two. A 2020 article in the Columbia Journalism Review refers casually to “fusspot grammarians and addled copy editors”; I’m not the only one who imagines the classic copy editor as uncreative, neurotic, and cold.

I want to say they’re the publishing professionals most likely, in the cultural imagination, to be female, but that doesn’t feel quite right: agents and full-on editors are female in busty, sexy ways, while copy editors are brittle, unsexed. Their labor nevertheless shares with other typically female labors a concern with the small and the surface, those aspects of experience many of us are conditioned to dismiss.

I’m willing to bet, too, that self-professed “grammar snobs” rarely come from power themselves—that there is a note of aspirational literariness in claiming the identity as such. [...]

It makes me wonder if, in renouncing my job when I left it—in calling copyediting the world’s least meaningful work—I might have been reenacting some of the literary scene’s most entrenched big-dick values: its insistence on story over surface (what John Gardner called the “fictional dream”), on anti-intellectualism but also the elitist cloak of it-can-never-be-taught. The grammar snob’s aspiration and my professor’s condescension bring to mind the same truism: that real power never needs to follow its own rules. [...]

Copyediting shares with poetry a romantic attention to detail, to the punctuation mark and the ordering of words. To treat someone else’s language with that fine a degree of attention can be an act of love. Could there be another way to practice copyediting—less attached to precedent, less perseverating, and more eagerly transgressive; a practice that, to distinguish itself from the quietly violent tradition from which it arises, might not be called “copyediting” at all; a practice that would not only “permit” but amplify the potential for linguistic invention and preservation in any written work?

--- Against Copyediting: Is It Time to Abolish the Department of Corrections? Helen Betya Rubinstein on Having Power Over More Than Just Commas

#linguistics#literature#copyediting#copyeditor#prescriptivism#grammar snobbery#editing#writing#publishing

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey cuties!

i noticed @headspace-hotel expressing surprise at how elementary and high school teachers are banning aave from schools under the pretense of "preventing gang activity", something that has bothered me for over a decade. personally, I have also heard teachers refer to it as "gibberish" or "incorrect" and uh ???? especially when the same students who used these words followed all of the "rules" in essays and presentations and even interactions with the teachers, only switching dialects with friends.

i was wondering, do any of you have experience with

1) an (english) dialect being erased or banned in an american school

2) an (english) dialect being erased/banned in an (english-speaking non-american) school

3) a (non-english) dialect/language being erased/banned in a (non-english-speaking) school or

4) a (non-english) dialect/language being erased/banned in an (english-speaking or american) school

this includes calques, loanwords, creoles, pidgins, etc.

ofc i do not mean curse words, which schools pretty universally ban.

some examples i have heard are aave, malayalam, and various indigenous languages from the americas.

these do not have to be your dialect or language, they can be any you have noticed. i do not speak aave, and am asian/white, but i have just noticed it in my schools until late high school.

please rb for sample size, cats and robots!!

do reblog or reply with experiences if you have em, i would like to hear, and will rb yours if you want!

this includes if you have no experience with this, why do you think you haven't?

if this happened to you, that is truly awful and i truly hope that that person or administration or government gets fired 🤭

love y'all! 💚

(side note: why would anybody ban "y'all" it is the most useful piece of nonacademic language ever istg)

#linguistics#language erasure#prescriptivism#poll#my post#dialect is a crucial part of culture#to remove it is to seek to kill the culture.#dialect#language#please rb for sample size cats and robots

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

i biggest question to people who say there is a correct way to speak english

why do you care

why do you care so much

dont pull the its wrong or its not how its always been done

do you speak how shakespeare spoke?

do you speak like anglo-saxons?

if you don't youre speaking wrong

do you see how stupid you sound?

language is fluid and is in constant change

the next time you get mad about someone say don't instead of doesn't or aks instead of ask

ask yourself

why do i care so much

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

#fuck prescriptivism!!!!!!!!!#prescriptivism#descriptivism#langblr#language#meme#linguistics#my posting#described#id in alt text

367 notes

·

View notes

Text

getting sad thinking about the dialects I would have known/spoken had it not been for the devaluation of “non-standard” variations of a language

#another reason why prescriptivism is the devil#it’s just. both my grandparents on my dad’s side speak/spoke dialects but they didn’t really pass them on to my dad bc it would have#hindered him in school. but bc he knows so little of them he doesn’t really feel connected to them either and didn’t pass the bits he does#know on to me either#also bc my mum is a prescriptivist with a capital letter and thinks dialects aren’t ‘good dutch’#which. girl. you literally didn’t learn your ancestors’ (for lack of better word) dialect either#oh also. I didn’t learn the dialect of the city I was born in either bc we moved away before I could#elli rambles#it just. makes me sad#all this linguistic diversity harmed by standardisation and the idea that the only purpose of a language is to communicate with as many#people as possible. while it’s such an important part of culture too#etc etc sorry I’m rambling#languageposting#why is this getting notes

608 notes

·

View notes

Text

"use commas" this "learn how to spell" that. you fools. the very core of linguistics is the change that you so despise on account of lacking any sort of knowledge or foresight. you imbeciles. we the linguists laugh at your little commas and dots that you throw around in your playpen. you think it matters? you think any of this matters? the only thing you should even slightly care about is if you can understand or interpret the core of the message. you hold up the punctuation system as you do the values of the past, thinking it sacred, much like a false idol. you will never be free if you dont stop policing the victimless crimes we've made up. you will never ascend.

#linguistics#language#mepost#every time someone fixes a spelling issue that isn't necessarily relevant a linguist loses their wings#we call your behavior prescriptivism and laugh at you behind your back by the way#this isn't to say let's not teach kids the official spelling rules#i just mean if someone's shitposting it's unnecessary#shitpost#i'm rambling#love u all#are you still here reading this#check out my other posts and make me feel loved#hey have you guys ever heard that song 'would?' by alice in chains?#it sounds like it's a 2000's videogame soundtrack dont you think?#i just think it's neat#oh god are they problematic#i should've googled this#well i guess let me know if they are#hey does anyone wanna be friends?#it gets lonely out here in the tags#i mean message me?#i cant promise you the best skills in the art of conversation#but i am known to hold one or two in my time#the conversations i mean#anyways thats all

397 notes

·

View notes

Note

heyyy im pretty sure the term "purity culture" is specifically used to refer to the kind of abuse that takes place in christian cults or christian circles with cult-like practices idk if you should be using it to refer to like. fandom drama.

Thanks for the feedback! (I think this is about the '#fandom purity culture' tag I use sometimes.)

This is something I've given a lot of thought about, and I don't expect—details below the cut—to change that part of my tagging system for the remainder of 2022 at least.

I'm not a linguistic prescriptivist, and haven't been for a while. Different terms take on different meanings in different ‘speech communities’, and even those drift over time with usage. (Which sometimes irks me as much as this particular use irks anon but that's language for you.)

And... the definition in the ask? That definition is not universal (and I mean that even restricting to Tumblr users; the top results for ‘purity culture Christian’ show that much).

I'm aware, as anon mentions, that some (culturally Christian?) speech communities exclusively use ‘purity culture’ to refer to a certain kind of abuse from Christian cults and similar organisations. Meanwhile, in the IRL queer/leftist circles (and a number of the online circles) I frequent, ‘purity culture’ refers more broadly to a subsuming phenomenon—of which abuse in culturally Christian cults is a part, but which also extends to e.g. groups that interrogate power dynamics and kyriarchy—of emotional abuse and behavioural control through manipulation of guilt and ‘scrupulosity’ (1, 2). The tag I've been using uses ‘fandom’ as a modifier to make it clear I'm talking about a specific variant.

If my continued use of this tagging scheme is a risk to your mental health, even a small one, I'd suggest you block that tag, or block this blog (😥).

#asks#anon#fandom purity culture#linguistic drift#linguistic prescriptivism#ref#won't go into details on specific things that led me to converge on these views#as i don't want to perpetuate people having to out themselves to satisfy their interlocutors#but anon you can reach me over DM if that helps#audit trail

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

All linguists are just here to menace prescriptivists, actually

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes words have meanings, words have meanings that naturally change over time. Some words have specific meanings that it's important to preserve for social, cultural and/or scientific reasons, but words don't get to have the same exact meanings forever just by virtue of being words. Humans have nature.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

seemingly cool fiber arts person i followed a little bit ago just put radfem shit on the dash, anyway the blanket statement that the only contributions of men to textile production are capitalist/exploitative and the only contributions of women are household-centric/victimized is patently untrue. while less of a documented presence, women in medieval europe [1] absolutely participated in weaver's guilds and commercial cloth production [2], and men have been participating in household knitting in all parts of europe for as long as knitting has been a thing there [3]. like i'm not trying to say women haven't been deeply excluded from economic opportunities in the textile trade for centuries but you cannot be making sweeping statements like that about everyone in every part of the world through all of history and expect them to be true. do, like, a basic level of research and have a basic understanding of nuance, i beg of you [4]

footnotes/sources/etc under the cut, sources are a bit basic because i just grabbed whatever was nearest to hand but they should suffice to prove my point:

[1] i'm only referring to western europe here because that's the only region i feel comfortable talking about in any detail without embarrassing myself. systems of medieval cloth production in european guilds are not gonna look anything like the systems of hundreds of servants employed to do textile production for a household in china. don't make categorical statements about everyone everywhere all at once, you will end up with egg on your face.

[2] quotes from "when did weaving become a male profession," ingvild øye, danish journal of archaeology, p.45 in particular.

england: "in norwich, a certain elizabeth baret was enrolled as freeman of the city in 1445/6 because she was a worsted weaver, and in 1511, a riot occurred when the weavers here complained that women were taking over their work" + "another ordinance from bristol [in 1461] forbade master weavers to engage wives, daughters, and maids who wove on their own looms as weavers but made an exception for wives already active before this act"

germany: "in bremen, several professional male weavers are recorded in the early fourteenth century, but evidently alongside female weavers, who are documented even later, in 1440" -> the whole "even later" thing is because the original article is disputing the idea that men as weavers/clothiers in medieval europe entirely replaced women over time. also: "in 1432-36, a female weaver, mette weuersk, is referred to as a member of the gertrud's guild in flensburg, presently germany"

scandanavia: "the guild of weavers that was established in copenhagen in 1500 also accepted female weavers as independent members and the rules were recorded in the guild's statutes"

[3] quotes from folk socks: the history and techniques of handknitted footwear by nancy bush, interweave press, 2011, don't roast me it was literally within arm's reach and i didn't feel like looking up more stuff

uk/yorkshire dales: "...handknitting had been a daily employment for three centuries [leading up to 1900]. practiced by women, children, and men, the craft added much to the economy of the dales people." (p.21)

uk/wales: re the knitting night (noson weu/noswaith weu) as a social custom practiced in the 18th/19th c.: "all the ladies would work on their knitting; some of the men would knit garters" (p.22)

uk/channel islands: "by the early seventeenth century, so many of the islands' men, women, and children had taken up the trade of knitting that laws were necessary to keep them from knitting during harvest" (p.24) -> this one is deeply funny to me, in addition to proving my point

uk/aberdeen: "the knitters, known as shankers, were usually women, but sometimes included old men and boys" (p.26)

denmark: "with iron and brass needles, they made stockings called stunthoser, stomper, or stockings without feet, as well as stockings with feet. the men knit the legs and the women and girls made the heels" (p.32)

iceland & faroe islands: "people of all ages and both sexes knit at home not only for their own use but for exportation of their goods as well" (p.35)

[4] actually? no. i'm not begging for shit from radfems. fuck all'a'y'all.

#fuck it maintagging because i'm genuinely deeply annoyed about this#eta: un-maintagging bc after a couple days' reflection - i stand by the substance of what i said but i don't stand by my tone or attitude#shoot-from-the-hip reactionary anger is seldom effective and more to the point it's not a response of grace or love & i should do it less#aggressive linguistic prescriptivism#<- personal fiber arts category tag#<- that tag can stay tho i think this is an internal use only kinda post

187 notes

·

View notes