Text

God, this Prosecraft thing.

Is it, buddy? Are you sure? How, exactly, am I supposed to use any of that in my day-to-day writing? Why is this useful?

(Not even addressing the quality of this information, which is fairly dubious)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The real targets of the AI backlash that swept Prosecraft away are the generative AI companies that are currently the toast of Silicon Valley, as well as the corporations planning to use those generative AI tools to replace human creative work."

Personally I'm disgusted by the attempt to "both-sides" Prosecraft's theft--the article flatly states (and Smith has admitted) that the "database" was built from stolen ebooks, literally taken from ebook theft sites.

That said, the article's still useful, I suppose.

0 notes

Text

the feeling when you’ve started writing a new story, having downloaded a shiny new toy (i.e. writing software), but the next day, your laptop is acting out, the software keeps on synchronising instead of working properly, so you can do hardly anything, because half of what you’ve done is in the stuff the software didn’t export. yay.

(p.s. if anyone uses shaxpir, does this sort of thing happen often, or is it just somehow incompatible with me?)

0 notes

Text

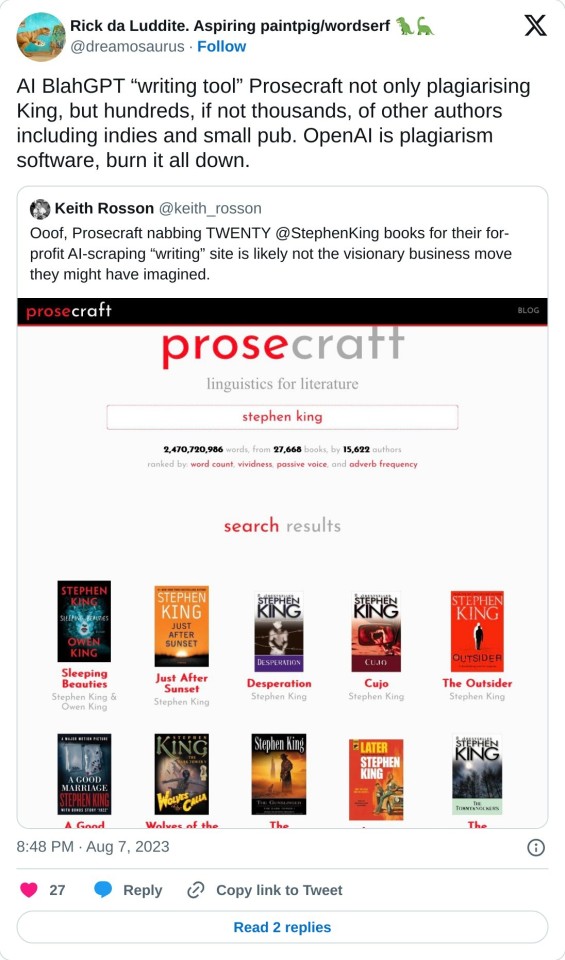

The website Prosecraft has been nabbing popular and indie creators work for generative ai

The website has been deleted

But not the data

It's still being used for shaxpir software where they still get money

Thread

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hari Kunzru wasn’t looking for a fight. On August 7, the Brooklyn-based writer sat on the subway, scrolling through social media. He noticed several authors grumbling about a linguistic analysis site called Prosecraft. It provided breakdowns of writing and narrative styles for more than 25,000 titles, offering linguistic statistics like adverb count and ranking word choices according to how “vivid” or “passive” they appeared. Kunzru pulled up the Prosecraft website and checked to see whether any of his work appeared. Yep. There it was. White Tears, 2017. According to Prosecraft, in the 61st percentile for “vividness.”

Kunzru was irked enough to add his own voice to the rising Prosecraft protest. He wasn’t mad about the analysis itself. But he strongly suspected that the founder, Benji Smith, had obtained his catalog without paying for it. “It seemed very clear to me that he couldn’t have assembled this database in any legal way,” he says. (And Kunzru is no stranger to thinking about these issues; in addition to his successful career as a novelist, he has a past life as a WIRED writer.)

“This company Prosecraft appears to have stolen a lot of books, trained an AI, and are now offering a service based on that data,” Kunzru tweeted. “I did not consent to this use of my work.”

His message went viral. So did a plea from horror writer Zachary Rosenberg, who addressed Benji Smith directly, demanding that his work be removed from the site. Like Kunzru, he’d heard about Prosecraft and found himself upset when he discovered his work analyzed on it. “It felt rather violating,” Rosenberg says.

Hundreds of other authors chimed in. Some had harsh words for Smith: “Entitled techbro.” “Soulless troll.” “Scavenger.” “Shitstain.” “Bloody hemorrhoid.”

Others pondered legal action. The Author’s Guild was inundated with requests for assistance. “The emails just kept coming in,” says Mary Rasenberger, its CEO. “People reacted really strongly.” Prosecraft received hundreds of cease-and-desist letters within 24 hours.

By the end of the day, Prosecraft was kaput. (Smith deleted everything and apologized.) But the intense reaction it provoked is telling: The great AI backlash is in full swing.

Prosecraft’s founder didn’t see the controversy coming.

On Monday, Benji Smith had recently returned to his home in a small town just outside of Portland, Oregon.

He’d spent the weekend at a gratitude meditation conference, and he was excited to return to work. Until this past May, Smith had held a full-time job as a software engineer, but he’d quit to focus on his startup, a desktop word processor aimed at literary types, called Shaxpir. (Yes, pronounced “Shakespeare.”) Shaxpir doesn’t make much money—not enough to cover its cloud expenses yet, Smith says, less than $10,000 annually—but he’d been feeling optimistic about it.

Prosecraft, which Smith launched in 2017, was a side hustle within a side hustle. As a stand-alone website it offered linguistic analysis on novels for free. Smith also used the Prosecraft database for tools within the paid version of Shaxpir, so it did have a commercial purpose.

Although he was anointed the ur-tech bro of the week, Smith doesn’t have much VC slickness. He’s a walking Portlandia stereotype, with piercings and bird tattoos and stubble; he talks effusively about the art of storytelling, like he’s auditioning for the role of a superfan of The Moth. A self-described theater kid, Smith dabbled in playwriting before getting his first tech gig at a computational linguistics company.

The idea for Prosecraft, he says, came from his habit of counting the words in books he admired while he was working on a memoir about surviving the 2012 Costa Concordia shipwreck. (“Eat Pray Love is 110,000 words,” he says.) He thought other authors might find this type of analysis helpful, and he developed some algorithms using his computational linguistics training. He created a submissions process so writers could add their own work to his database; he hoped it would someday make up the bulk of his library. (All in all, around a hundred authors submitted to Prosecraft over the years.) It did not occur to Smith that Prosecraft would end up enraging many of the very people he wanted to impress.

Prosecraft did not train off any large language models. It was not a generative AI product at all, but something much simpler. More than anything else, it resembled the kind of tool an especially devoted and slightly corny computational linguistics graduate student might whip up as an A+ final project. But it appears to share something crucial with most of the AI projects making headlines these days: It trained on a massive set of data scraped from the internet without regard to possible copyright infringement issues.

Smith saw this as a grimy means to a justifiable end. He doesn’t defend his behavior now—“I understand why everyone is upset”—but wants to explain how he defended it to himself at the time. “What I believed would happen in the long run is that, if I could show people this thing, that people would say, ‘Wow, that's so cool and it's never been done before. And it's so fun and useful and interesting.’ And then people would submit their manuscripts willfully and generously, and publishers would want to have their books on Prosecraft,” he says. “But there was no way to convey what this thing could be without building it first. So I went about getting the data the only way that I knew how—which was, it's all there on the internet.”

Smith didn’t buy the books he analyzed. He got most of them from book-pirating websites. It’s something he alluded to in the apology note he posted when he took Prosecraft down, and it’s something he’ll admit if you ask, although he seems bewildered about how mad people are about it. (“Would people be less angry with me if I bought a copy of each of these books?” Smith wonders out loud as we talk over Zoom. “Yes,” I say.) The practice of using shadow libraries to conduct scholarly work has been debated for years, with projects like Sci-Hub and Libgen disseminating academic papers and books to the applause of many researchers who believe, as the old adage goes, that information wants to be free.

Many of the authors who chastised Smith, like Kunzru, disapprove primarily of this pirated database. Or, more specifically, they hate the idea of trying to make money off work derived from a pirated library as opposed to simply conducting research. “I’m not against all data scraping,” Devin Madson says. “I know a lot of academics in digital humanities, and they do scrape a lot of data.” Madson was one of the first people to contact Smith to complain about Prosecraft last week. What rubbed her the wrong way was the attempt to profit from the analytical tools developed with scraped data. (Madson also more broadly disapproves of AI writing tools, including Grammarly, for, as she sees it, encouraging the homogenization of literary style.)

Not every author opposed Prosecraft, despite how it appeared on social media. MJ Javani was delighted when he saw that Prosecraft had a page about his first novel. “As a matter of fact, I dare say, I may have paid for this analysis if it had not been provided for free by Prosecraft,” he says. He does not agree with the decision to take the site down. “I think it was a great idea,” Daniela Zamudio, a writer who submitted her work, says.

Even supporters have caveats about that pirated library, though. Zamudio, for instance, understands why people are upset about the piracy but hopes the site will come back using a submissions-based database.

The moral case against Prosecraft is clear-cut: The books were pirated. Authors who oppose book pirating have a straightforward argument against Smith’s project.

But did Smith deserve all that blowback? “I think he needed to be called out,” Kunzru says. “He maybe didn't fully understand the sensitivity right now, you know, in the context of the WGA strike and the focus on large language models and various other forms of machine learning.”

Others aren’t so sure. Publishing industry analyst Thad McIlroy doesn’t approve of data scraping, either. “Pirate libraries are not a good thing,” he says. But he sees the backlash against Prosecraft as majorly misguided. His term? “Shrieking hysteria.”

And some copyright experts have watched the furor with their jaws near the ground. While the argument against piracy is simple to follow, they are skeptical that Prosecraft could’ve been taken to court successfully.

Matthew Sag, a law professor at Emory University, thinks Smith could’ve mounted a successful defense of his project by invoking fair use, a doctrine allowing use of copyrighted materials without permission under certain circumstances, like parody or writing a book review. Fair use is a common defense against claims of copyright infringement within the US, and it’s been embraced by tech companies. It’s a “murky and ill-defined” area of the law, says intellectual property lawyer Bhamati Viswanathan, who wrote a book on copyright and creative arts. Which makes questions of what does or does not constitute fair use equally murky and ill-defined, even if it’s derived from pirated sources.

Sag, along with several other experts I spoke with, pointed to the Google Books and HathiTrust cases as precedent—two examples of the courts ruling in favor of projects that uploaded snippets of books online without obtaining the copyright holders’ permission, determining that they constituted fair use. “I think that the reasons that people are upset really don't have anything to do with this poor guy,” says Sag. “I think it has to do with everything else that’s going on.”

Earlier this summer, a number of celebrities joined a high-profile class action against OpenAI, a suit that alleges that the generative AI company trained its large language model on shadow libraries. Sarah Silverman, one of the plaintiffs, alleges OpenAI scraped her memoir Bedwetter in this way. While the emotional appeal behind the lawsuit is considerable, its legal merits are a matter of debate within the copyright community. It’s not widely viewed as a slam dunk by any means. It’s not even clear a court will find that the source of the books is relevant to the fair-use question, in the same way that you couldn’t sue a writer for copying your plot on the grounds that they shoplifted a copy of your book.

Rasenberger strongly supports enforcing copyright protections for authors. “If we don't start putting guardrails up, then we will diminish the entire publishing ecosystem,” she says. Rasenberger cites the recent US Supreme Court decision on whether some of Andy Warhol’s artwork infringed on copyright as evidence that the legal system may be reining in its interpretation of fair use. Still, she sees the legal question as unsettled. “What feels fair to an author isn't always going to align with the current fair-use law,” Rasenberger says.

“Prosecraft is a little guy who got swept up in a much bigger thing—he’s collateral damage,” says Bill Rosenblatt, a technologist who studies copyright.

Rosenblatt is fascinated by how far public opinion on copyright and data has shifted since the days of Napster. “Twenty years ago, Big Tech positioned this as ‘it's us against the big evil book publishers, movie studios, record labels,’” Rosenblatt says. Now the dynamic is strikingly different—the tech companies are the Goliaths of business, with artists, musicians, and writers attempting to rein them in. While Prosecraft might’ve been viewed more sympathetically in an earlier era, today it is seen as ideologically aligned with Big Tech, no matter how small it actually is.

Smith offered the same service for five years without issue—but at a moment when writers and artists are deeply wary of artificial intelligence, Prosecraft suddenly looked suspicious in this new context. An AI company only in the loosest sense of the term, Prosecraft wasn’t so much low-hanging fruit as it was a random cucumber on the ground near the fruit tree. Was there something rotten about it? Yes, sure. But describing it as collateral damage isn’t inaccurate. The real targets of the AI backlash that swept Prosecraft away are the generative AI companies that are currently the toast of Silicon Valley, as well as the corporations planning to use those generative AI tools to replace human creative work.

A year from now, it’s unlikely people will remember this particular social-media-fueled controversy. Smith acquiesced to his critics quickly, and a little-used, small-potatoes analytics tool is now defunct. But this incident is illustrative of a larger cultural turn against the unauthorized use of creative work in training models. In this specific case, writers scored an easy victory against one dude in Oregon with a shaky grasp on the concept of passive voice.

I suspect the reason so many prominent voices celebrated so loudly is because the larger ongoing fights will be much longer, and much harder to win. The Hollywood writer’s strike, with the Writers Guild of America demanding that studios negotiate over the use of AI, is the longest strike of its kind since 1988. The OpenAI lawsuit is another attempt to wrest back control; as mentioned, it is likely to be a far harder fight to win considering fair-use precedence.

In the meantime, writers are also moving to create their own individual guardrails for how generative AI can use their work. Kunzru, for example, recently negotiated a publishing contract and asked to add a clause specifying that his work not be used to train large language models. His publisher cooperated.

Kunzru is far from the only author interested in gaining control over how LLMs train on his work. Many writers negotiating contracts are asking to include AI clauses. Some aren’t having the smoothest experiences. “There's been a huge amount of pushback against AI clauses in contracts,” Madson says.

Literary agent Anne Tibbets has seen a surge in interest from writers in recent months, with many clients in contract negotiations asking to include an AI clause. Some publishers tend to be slow to respond, debating the most appropriate language.

Others aren’t interested in any form of compromise for this potential new revenue stream: “There are some publishers who are flat-out refusing to include language at all,” Tibbets says. Meanwhile, agencies are already hiring consultants specifically to guide their AI policies—a sign that they are well-aware that this conflict isn’t going away.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prosencraft & Quilldenstern are Dead

Curiosity had me digging into the whole Prosecraft/Shaxpir drama that's been going around twitter.

I can see some wiggle room with what the bro was trying to do (or said he was doing) with Prosecraft, but the whole concept still sounds like dubious BS. Picking out the "most vivid" and "most passive" paragraph of an entire novel?? How would you decide that? How can you even state as a fact that one paragraph is more "vivid" than another? Like, just looking at what the program itself promises to do, it sounds like crap. It honestly reminds me of that site (sites?) that let you enter a paragraph of text and "analyzed" it to tell you which famous author you most sounded like. Except the answers were randomly generated. You could enter a passage from, say, Kurt Vonnegut, and get a different result each time (none of them Vonnegut). This sounds like the same kind of scam.

Then of course, you have the whole extremely illegal harvesting of books from the internet. And that some of the paragraph samples include massive spoilers for the book. And all the rest that has authors furious for very good reasons. I hope the lawyers destroy him. "Freely available on the internet" doesn't mean legally available, bro.

As for the Shaxpir AI thingy, I found a LOT of complaints predating the latest drama. The program sounds like shit. It routinely loses data and drafts, with no way of recovering what you'd written. It also got a lot of things wrong and seems like it's just a sketchier, less reliable version of Scrivener. One person who'd used both programs said they lost a lot of their stuff in Scrivener, but lost even more with Shaxpir. So again, based on the bare bones of what it's supposed to do, it doesn't really do its job.

The concerns about harvested materials being used to "refine" the program are valid, IMO, and just because Shaxpir sucks at is job doesn't mean it's acceptable to let it get away with anything illegal.

Anyway, no sympathy for the latest techbro suffering the consequences of his actions, but he also gives off CMOT Dibbler vibes rather than someone actually competent at their job. But I guess that goes for most of the techbros out there. LOL!

Also, definite points off for not calling it Prosencraft, when he was pairing it with Shaxpir.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Authors are losing their patience with AI, part 349235

On Monday morning, numerous writers woke up to learn that their books had been uploaded and scanned into a massive dataset without their consent. A project of cloud word processor Shaxpir, Prosecraft compiled over 27,000 books, comparing, ranking and analyzing them based on the “vividness” of their language. Many authors — including Young Adult powerhouse Maureen Johnson and “Little Fires…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Went through 15 different writing programs and finally finally finally landed on.... Google docs....

Because a place where you do writing should be in the first place a good word processor. I feel annoyed.

Shaxpir is also good but doesn't work on Linux nor has a mobile version or browser version accessible by phone...

#im annoyed and disappointed and no longer feel bolstered by the tech#fucking google docs....#just wish that word plugin worked like it should!!!#agghfhfhf#then id try to install it with wine...#no longer bolstered by tech#though it works well enough...#my stuff#personal#lying in bed and why should i do anything wt all

0 notes

Note

if u don't mind answering (totally cool, just ignore this), how did u go about formatting and putting together your chapbook?? like in terms of software and design etc. that's something I've been wondering about recently and I'd love to know because I have no clue!!

i just used word and a book formatting template, then i changed the fonts & graphics to what i needed. however, i used reedsy for the formatting of ugly happy and i also use shaxpir sometimes which both are free for formatting and typesetting and i highly recommend!

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Paaaaan (picture me whining like my 9-year-old), you mentioned writing in small bits and pieces. How do you deal with continuity and flow of your writing. I'm slowly working my way through a second draft, and I'm seeing (and I know I'm missing) lots of places where I seem to have written a sentence, walked away, and forgotten what I wrote in that, then written a second one that's too similar. Any advice?

On the preparation side of it, the more detailed my outline is, the easier I find it to stay on target. For something short like a one-shot, it might be as simple as a list of goals. For something longer, I might summarize the story in paragraph form and use that to stay focused. Note cards. Beat sheet. Lately I've been using an app called Shaxpir that let's you easily reorder pages (it's a fancy notebook basically), and I'll title the page with the goal of the scene.

Then while I'm writing, I have playlists that I listen to, but this might be weird for some people. Every WIP doesn't have its own, but I have one for the major genres or series (e.g., Gods of War has a playlist, Die for This Kingdom has a playlist, the WWII stuff has a playlist). Having a consistent "auditory vibe" helps me to at least keep my narrative voice more coherent.

Honestly, though, for the most part I just fix it in post. I hop in and out of my documents frequently enough that rereading the current paragraph is usually sufficient to jog my memory.

After I get the first draft down (often piecemeal), I let it simmer for a day before I reread it. The first pass is looking for major flow, big holes, that sort of thing. I make patches to the plot and narration here. I also identify places I need to add some meat, and trim the fat from others.

I have DEFINITELY come across sentences that made absolute no damn sense. I just delete them. Third and fourth passes are polishing and refining.

I think it really just comes with practice. Writing with a coauthor made me more comfortable with this. So @iihappydaysii and I write back and forth on a story, and part of our editing process is making sure that it sounds like one voice (it helps that we take turns editing too).

So maybe the advice there is treat your draft like you weren't the only person who wrote it? Use comments and track changes to edit, then go back and accept or cancel those edits, so you can see what you've changed in multiple ways. Focusing on a markup also can keep you from getting that highway hypnosis while you're editing.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My most favorite writing software

I know I haven't posted any original content in a while, mental health issues suck. But. I've decided to make a list of my top three favorite writing software in case anyone's looking for something new to try.

Please reblog with your own faves!

ZenWriter - $18 desktop version/$3 a month browser version

Man, I absolutely love ZenWriter! I do all my first drafts in it because it's a perfect distraction-free (except my brain is still distracting me) software. It has so many different features; you can change everything from the background to the sound your keyboard makes, but at the same time it's not overwhelming.

10/10

WPS office - a freemium Microsoft office alternative (the free version is more than enough for me, though)

You can use it for anything you use Microsoft office for. I mostly use WPS word for second drafts or early revisions, but I also keep all drafts in it because it's easier that way.

8.5/10

Shaxpir - a freemium Scrivener alternative (kinda)

Now, I've run into a big issue with this one. It was working perfectly until my laptop malfunctioned one day, and after that, it just wouldn't start. I've tried to reinstall it, but it just doesn't work on this laptop anymore.

However, I still recommend it because I actually liked it a lot. Scrivener is too complicated and overwhelming to me, Shaxpir has a big variety of similar features, but it doesn't overwhelm you. And it's easy to navigate.

5/10

#writeblr#writing#writers of tumblr#writers#writerscommunity#writing software#editing#drafting#writing tips#writing advice#writing apps

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any recommendations on good affordable writing apps? (affordable meaning under 20 dollars if possible). I’ve had my eye on Storyist for a while but it’s 60 dollars for the Mac which scares me off since I’m not quite sure if it’ll be the right fit for me. Anyway, any recommendations you have I would love to hear :) hope you’re doing well!

Hey! It’s so nice to hear from you. Scrivener ($45 and I’ve never heard bad things about it). I haven’t used the following programs personally, but they were recommended by DCBB participants and are free:

yWriter6 by Spacejock Software - Writing software for Windows. Android and iOS versions available.

Shaxpir - Writing software for Windows and Mac. Pro version available.

There’s always Google Docs, which is great for Chromebook users (like me!). And while this isn’t writing software, I like myWriteClub for keeping track of word counts and global sprinting.

If anyone has other writing software recommendations, please weigh in!

#replies#wanderingcas#writing software#writing stuff#I work on mac and a chromebook#to clarify#storyist is mac-only software

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post published on https://tangledtech.com/amazon-kdp/software-for-authors-best-free-writing-tools/

Software for Authors: 3 Best Free Writing Tools

Software for Authors: Best Free Writing Tools – It’s not easy to write a book. It’s just as hard keeping your motivation up as each day passes. There are countless things that might stop you from ever finishing your novel. However, having access to the right software can help you to stay organized and focused, and get you to the homestretch. Here are 3 of the best free writing tools that I’m sure you’ll enjoy using. Best Free Writing Tools 1. Shaxpir Shaxpir is an elegant-looking writing tool that helps you keep your story organized through notes, images and word…

0 notes

Text

I'ma try shaxpir writing program. Has anyone tried that one?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

smart quotes are the WORST i am SO MAD this STUPID WRITING PROGRAM CAN’T TURN THEM OFF ARGH

what should i get? any suggestions? shaxpir is just not that great, tbh

0 notes