#syrian refugee

Photo

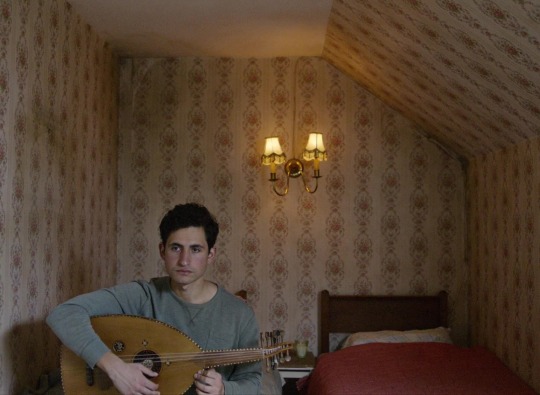

Limbo (Ben Sharrock - 2020)

#Limbo#Ben Sharrock#Afghanistan#racism#syrian refugee#comedy-drama film#Amir El-Masry#Vikash Bhai#Ola Orebiyi#European cinema#Kais Nashef#Syrian music#Middle East#Sidse Babett Knudsen#Scotland#refugees#asylum seekers#Arabic music instruments#Scottish islands#British movies#separation from family#sadnessoud#syrian refugees#youth#friendship#friends#politeness#nostalgia#censorship#list

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woman Attacked on Escalator in Berlin, Deutschland just because

youtube

0 notes

Text

#far-right activist tommy robinson aka stephen yaxley-lennon#breach of a court order#defamatory lies#refugees#syrian refugee#contempt of court charges#uk high court#racism#xenophobia#far-right riots#united kingdom

0 notes

Text

اجتماع بين منظمات سورية ومسؤولين أتراك بشأن حملة الترحيل.. ماذا نتج عنه؟

اجتماع بين منظمات سورية ومسؤولين أتراك بشأن حملة الترحيل.. ماذا نتج عنه؟

ملخص

عقدت ولاية إسطنبول اجتماعاً لبحث قضايا الهجرة غير الشرعية وترحيل السوريين وتأثيرها على الأشخاص ذوي الوضع القانوني.

تم التأكيد على استمرار حملة مكافحة الهجرة غير النظامية ولكن بتحسينات لعدم التأثير على الأشخاص ذوي الوضع النظامي.

ستتخذ إجراءات قانونية ضد أي موظف يستخدم العنف دون مبررات قوية وحاسمة.

لن يكون هناك حاجة لإصدار محاضر شرطة للسوريين الذين فقدوا هوية الحماية المؤقتة للحصول على هوية…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Truly a disgraceful world we live in when a foreign criminal can stab children in a park. The suspect came from Syria, with refugee status in Sweden, yet abandoned his wife and children; he entered a park in Annecy, France, and deliberately targeted children with a knife. All four are in hospital. The attacker was a Christian, said to be invoking Jesus Christ during his despicable attacks.

It's time for Western nations to think carefully about who is awarded refugee status in Europe. This is not the first time that such an attack has been committed by a foreigner who abuses the asylum system, and if our leaders do not get to grips with mass immigration, it will not be the last.

Praying that all four children make a full recovery!

0 notes

Photo

Syrian refugees in Europe

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tim Ganser at The UnPopulist:

Since the end of World War II, Germans had by and large steadfastly resisted voting for far-right populists. That norm was shattered in the last decade by the success of the political party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which seemed to gain more traction as it radicalized into a full-blown, hard right populist party.

A year into its existence, spurred by widespread discontent with German fiscal policy, the AfD won seven seats in European Parliament. In 2017, after undergoing a hard-right turn, it won 94 seats in the German federal elections, good for third place overall. For the past year, the AfD has consistently ranked second in Politico’s poll aggregator tracking the public’s voting intentions.

In this Sunday’s European Parliament elections, roughly 1 in 6 German voters is expected to cast a ballot for the AfD, whose members have trivialized the Holocaust, encouraged their followers to chant Nazi slogans, and participated in a secret conference where they fantasized about forced deportations of naturalized citizens they derisively call “Passport Germans.” Worse still, the AfD is predicted to be the strongest party, with up to a third of the vote share, in the three elections for state parliament in Saxony and Thuringia on Sept. 1 and in Brandenburg on Sept. 22. And in generic polls for a hypothetical federal election, the AfD fares even better than it did in any previous election. How did Germany get to this point?

The AfD’s Origin Story

The AfD was founded in early 2013 by a group of conservatives, led by the economics professor, Bernd Lucke, greatly disillusioned with then-Chancellor Angela Merkel’s fiscal policy. In their view, the European debt crisis had revealed deep instability within the eurozone project as smaller nations found themselves unable to cope with the economic demands of membership, and they believed Merkel’s focus on saving the euro was coming at the expense of German economic interests. This was, however, the opposite of a populist complaint—in fact, the AfD was initially referred to as a “Professorenpartei” (a professor’s party) because of the party’s early support from various economics professors who were more interested in fiscal policy than catering to popular will. In its earliest days, the AfD could best be characterized as a cranky but respectable party of fiscal hardliners. Its anti-establishment posture stemmed entirely from its belief in the necessity of austerity. Even its name could be construed less as nationalistic and more an answer to the dictum coined by Merkel—“alternativlose Politik” (policy for which there is no alternative)—to defend her bailouts during the eurozone crisis.

Although the AfD had launched an abstract economic critique of Merkel’s policies that could be hard to parse for non-experts, its contrarian stance resonated with a significant portion of Germans. Right out of the gate, the AfD obtained the highest vote share of any new party since 1953, nearly clearing the 5% threshold for inclusion in the Bundestag, Germany’s Parliament, in its first electoral go round. Its success was also measurable in terms of membership, passing the 10,000 mark almost immediately after its formation.

The rapid increase in membership, however, helped lay the groundwork for its turn toward right-wing populism. Perhaps due to pure negligence—or a combination of calculation and ambition—the party’s founders did little to stop right-wing populists from swelling its rolls. And as the German economy emerged through the European debt crisis in good financial shape, fiscal conservatism naturally faded from the public’s consciousness. However, a new European crisis having to do with migrants came to dominate the popular imagination. The AfD hardliners seized on the growing anti-migrant opinion, positioning the AfD as its champion, thereby cementing the party’s turn towards culture war issues like immigration and national identity.

Starting in late 2014, organized right-wing protesters took to the streets to loudly rail against Germany’s decision to admit Muslim migrants, many fleeing the Syrian civil war. The AfD right wing’s desire to become the political home of nativism led to a rift within the party that culminated in founder Bernd Lucke’s being ousted as leader in 2015, and his replacement with hardliner Frauke Petry. Lucke left the party entirely, citing its right-wing shift, following in the footsteps of what other party leaders had already done and more would do in the coming year.

Up until this point, the AfD unwittingly helped the cause of right-wing populism. If the reactionary far-right had tried to start a party from scratch, it would have likely failed. The AfD, after all, was created within a respectable mold, trading on the credentials of its earliest founders and leaders. But with saner voices now pushed out, right-wing populists had the party with public respectability and an established name all to themselves. And they deliberately turned it into a Trojan horse for reactionary leaders who wanted to “fight the system from within.

[...]

A New Normal in Germany

As right-wing populist positions have become part of the political discourse, Germany is now in the exact same position as some of its European neighbors with established hardline populist parties. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni ascended to the premiership in October 2022 as the head of her neo-fascist Fratelli d’Italia party, which is poised to perform well in the upcoming European Parliament elections. In France, the Marine Le Pen-led far-right Rassemblement National (RN) is set to bag a third of votes in those elections, roughly double what President Macron’s governing coalition is expected to obtain.

What makes the situation in Germany especially worrisome is that, unlike in France and Italy, far-right parties had failed to garner any meaningful vote share in nationwide elections until just seven years ago; indeed, until the 2017 federal election, there had never been a right-wing populist party that had received more than six percent of the national vote in Germany. The nation’s special vigilance toward far right ethnonationalism in light of its history of Nazi atrocities was expected to spare Germany the resurgence of far-right populism. But it actually led to complacency among mainstream parties. By 2017, the AfD—already in its right-wing populist phase—received nearly 13% of the vote in the federal election to become the third-strongest parliamentary entity. And by then it had also made inroads in all state parliaments as well as the European Parliament. The norm against it was officially gone.

To be sure, the AfD is not on track to take over German politics. It currently has the fifth most seats among all German parties in the Bundestag, fourth most seats among German parties in the European Parliament, and is a distant eighth in party membership. Nor is it currently a threat to dominate European politics—late last month, the AfD was ousted from the Marine Le Pen-led Identity and Democracy (ID) party coalition, the most right-wing group in the European Parliament. Le Pen, herself a far-right radical, explained the AfD’s expulsion by describing the party as “clearly controlled by radical groups.” But none of the above offer good grounds for thinking the AfD will be relegated to the fringes of German or European politics.

After the election, the AfD could rejoin ID, or it could form a new, even more radical right-wing presence within the European Parliament. Some fear that the AfD could potentially join forces with Bulgaria’s ultranationalist Vazrazhdane. Its leader, Kostadin Kostadinov, said that AfD’s expulsion from ID could create an opening to form “a real conservative and sovereigntist group in the European Parliament.” Also, ID’s removal of the AfD wasn’t due to its stated policy platform being out of step with Europe’s right-wing populist project. Rather, it was because the AfD’s leading candidate, Maximillian Krah, was implicated in a corruption and spying scandal involving China and Russia, and because he said he would not automatically construe a member of the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) to be a criminal. Absent these entirely preventable missteps, the AfD would be in good standing with right-wing populist partners in Europe.

Seeing far-right Nazi-esque Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) rise in prominence in Germany is a sad sight.

#Germany#Right Wing Populism#Far Right#AfD#Alternative für Deutschland#European Debt Crisis#Eurozone Debt Crisis#Bernd Lucke#Frauke Petry#Syrian Refugee Crisis#Björn Höcke

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

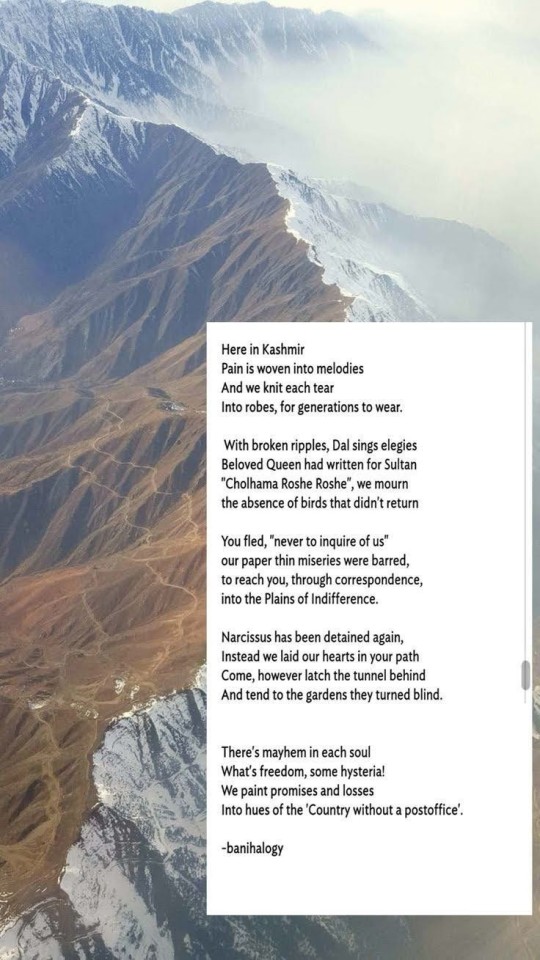

Sorry people, there are no tags regarding kashmir so, I used others.

#kashmir#islamdaily#free gaza#free palestine#all eyes on sudan#all eyes on rafah#all eyes on palestine#all eyes on gaza#keep eyes on sudan#sudan genocide#free sudan#sudan#sudan crisis#syrian civil war#free syria#syrian refugees#syria#save rafah#free rafah#rafah#rafah under attack#palestinian genocide#palestinian lives matter#palestine genocide#muslim lives matter

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think about this a lot

#immigration#refugee#iranian#immigrant parents#west asia#mena#swana#north african#middle eastern#armenian#Palestinian#Lebanese#latinx#Persian#Syrian#Afghan#Iraqi#Kurdish#Assyrian

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

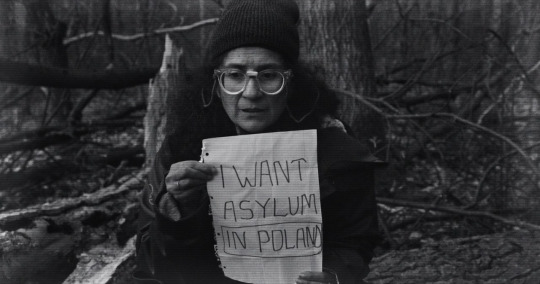

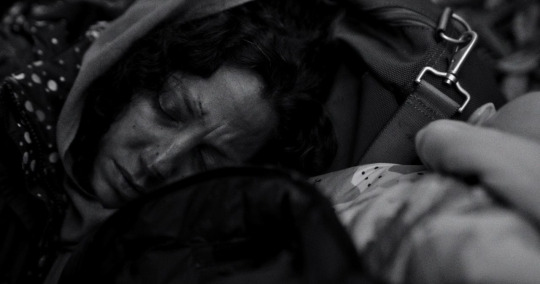

The Green Border (Agnieszka Holland, 2023)

#zielona granica#agnieszka holland#the green border#refugees#female filmmakers#female film directors#female directors#female directed films#women in film#female screenwriters#poland#syrian refugees

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video footage shows Hezbollah resistance forces targeting Israeli military sites in the occupied Syrian Golan and northern occupied Palestine.

#Hezbollah #Palestine #GolanHeights

#Hezbollah#palestine#golan heights#GolanHeights#videos#video#free palestine#freepalastine🇵🇸#سوريا syria#free syria#syrian civil war#syrian refugees#syria#free gaza#gaza genocide#gaza strip#gazaunderattack#gaza#all eyes on rafah#free rafah#save rafah#rafah under attack#rafah#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#signal boost#urgent#emergency#mutual aid#help#free palestine#palestine#free gaza#freepalastine🇵🇸#gazaunderattack#afghanistan#afghanistan earthquake#afghan refugees#free syria#syria#syrian civil war#free ukraine#ukraine#ukrainian refugees#refugees#displaced persons#displacement

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Entitled Thrill of a Syrian Refugee kicking a white woman down train station stairs in Manhattan | New York Post

youtube

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Okay seriously this is fucking bullshit.

The poor buggers are fleeing a warzone!

Deporting them isn’t gonna help!

#dougie rambles#news#vent post#middle east#levant#syria#lebanon#syrian civil war#refugees#bullshit#fuck Assad#fucking hell

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Old Oak (Ken Loach, 2023)

#The Old Oak#Ken Loach#Paul Laverty#UK#County Durham#England#United Kingdom#Syrian refugees#mining community#2020s cinema#European movies#Dave Turner#Ebla Mari#Claire Rodgerson#Murton#Horden#Easington#English people#precarity#proletariat#working class#capitalism#drama film#friends#friendship#solidarity#Gaza#genocide#Palestine#Margaret Thatcher

13 notes

·

View notes