#wuthering heights is one of the most complex well written books

Text

april reading meme!

BOOKS

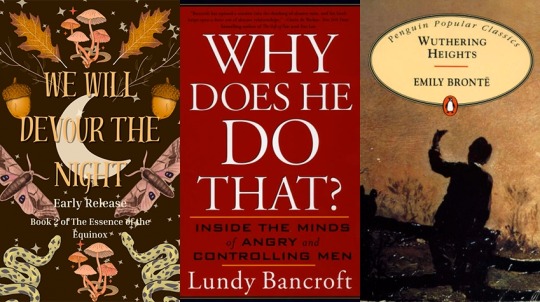

We Will Devour The Night by Camilla Andrew. The version I read is available in the author's ko-fi (aninkwellofnectar), and the final version will come during fall of this year. I've talked about this saga before (The Essence of the Equinox), and I still recommend it to those of us who like complex characters (especially female characters), gothic horror, and lush prose. This is a sequel, and I like it even more than the first instalment. It gets deeper into the darkness of the world and it's an amazing read. The third and final part has started been posted on ko-fi as well, for anyone interested.

Why Does He Do That? Inside The Minds of Angry and Controlling Men by Lundy Bancroft. I wish I could make everyone read this book. It wouldn't fix everything, because it runs against a lot of people's deep-seated belief systems, but maybe it would make SOME of them start second-guessing those beliefs... Anyway. A MUST read in terms of abuse and intimate partner violence.

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë. I read the book for the first time about 15 years ago, and only reread it now. I loved it even more than the first time. The atmosphere, the revenge tale, the love story between Catherine and Heathcliff, all the ways these families' lives affect the others, how you have to parse through Nelly's account of events... I still wish I could hit Lockwood in the head with a stick lol. Just once. Not even too hard! But hit him in the head, I would xD

COMICS

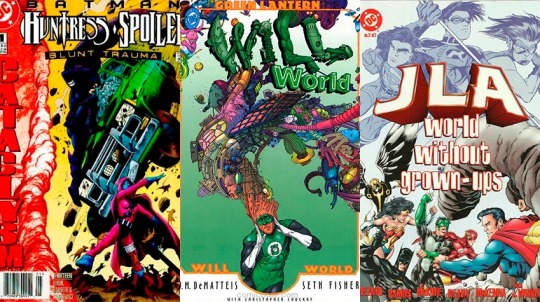

Batman: Huntress/Spoiler - Blunt Trauma. One of those "it could've been so good if it was good" comics. It would've had to NOT been written by Dixon, of course. His ideas about these two characters are palpable here. He's met real women and girls, I know this, but he's completely failed to take anything from these meetings into account to understand them as people. And boy, does it show in his writing.

Green Lantern: Willworld. I've had this comic in my list for aeons and I moved it up when I found out its author would be writing Jason's upcoming ADITF "what if" story starting July. I really liked this one, and how it showcased Hal's character. It's not a guarantee I'll like his Robin Lives run, because comic writers have biases and blind spots and huge gaps in their knowlege regarding certain characters, but "he seems to be a good writer" is already a huuuuge leg up compared to most modern Jason content lol.

JLA: World Without Grown-ups. This was interesting because I've watched the Young Justice (cartoon) version of this premise, which is VERY different, from the villains to their goals to the handling of the crisis (since the cartoon had an established teen team), down to the emotional beats (the Zataras). They're too different to be compared, tbh. This one was quite fun though, and it made me feel very fond of Bart. Also Tim's parasocial relationship with Jason's memorial made an appearance LOL.

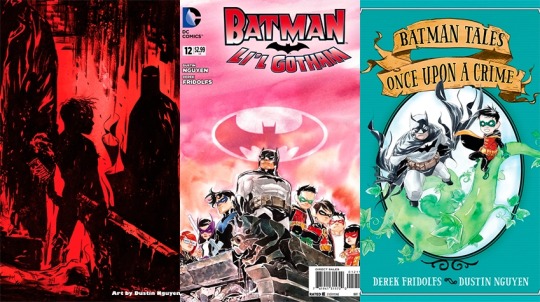

Colin Wilke's appearances. I am MOURNING this kid. He has like 9 appearances (and a couple of them are barely a few pages) but each one is gold. Bring him back. Make HIM Damian's best friend. Integrate him in the storyline!! His character and his dynamic with Damian had so so much potential. I am definitely going to include him in my fics.

Batman: Li'l Gotham. (plus the two stories introducing it in Batman Annual #27 and 'Tec Annual #11). A couple of things conspired (including me finding out there's a version of Colin in this lol) and I ended up reading it while I was sick. It's mostly fun fluff (as opposed to just corny fluff) and a quick read without much meat in it, but a few things nudged the inspiration muscle and Dustin Nguyen's art is adorable.

Batman Tales: Once Upon a Crime. I liked this one more than the above! It follows in that universe (a Gotham where everything is smaller and cuter lol), mixing it with some fairy tale vibes. Pinocchio!Damian is A Concept. Although my favourite story was "The Snow Queen", with Mister Freeze. The art goes into a whole other level in all of these, but especially that one.

Batman: The Chalice. Bruce Wayne receives the Holy Grail. I read this one in my list of Talia appearances and hers is the part that interested me: Ra's wants the Grail to make her immortal, like him, and Talia tells him that she has no desire to live forever. Her words are "Having lived my life in your company, the prospect of eernal life is not the attraction for me it might be for another." There are A LOT of things you can read into that sentence, and one of them, to me, is the idea that death to Talia would be an escape from Ra's, which is... interesting. Sidenote: this one was written by Dixon, who once in a while gets his wired crossed and is not wholly terrible with female characters xD

Ghost/Batgirl. I hadn't heard of Ghost before but I'm kinda curious after reading this mini run. I found a lot of the concepts it worked on (resurrection, mind control, etc.) quite interesting, although I ended up feeling the execution didn't delve too deeply into them. It's an story I might want to reread and pick apart at some point, though.

JLA: Tower of Babel. Yeah, THAT arc lol (also part of my Talia-reading). I also read JLA Secret Files and Origins #3 (in May, though), which shows Talia's whole thoughts on it as she steals the plans + some of the consequences the whole thing has for the other bats whose teammates no longer trust them (Dick, Tim, Barbara) + the wording of Bruce's contingency plans (which btw includes acceptance of lethal methods against Clark lol)... he certainly got off easy after this añsdlkfjasdf. Honestly, imo, the most selfish, cowardly thing he did was walking out before the JLA could tell him they'd voted him out. I know he and the comics probably won't frame it like that afterwards, but that's how it felt to me. The very least he could've done is face his teammates.

#reading meme#books#comics#dc comics#my thoughts#dc thoughts#id in alt text#captioned#the essence of the equinox#why does he do that#wuthering heights#batman: li'l gotham#colin wilkes#jla: tower of babel

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Happy sts

Is there an author or work that you think was particularly influencial on your style, works or viewpoints on writing?

hello hello! thank you for the question <3

honestly i'd say there's 3 main authors that influenced me as well as one specific genre that's influenced my actual prose style in general.

the three i would say would be (1) rick riordan (2) cornelia funke and (3) f scott fitzgerald

rick riordan and cornelia funke inspired me in terms of story structure, topics, and general depths of character and creating dialogue. i used to be much stronger with dialogue versus prose (though i've always been a bit descriptive), but the way that i looked at prose changed entirely when i first read the great gatsby in 11th grade. i Love that book. the way it's written is absolutely sublime and i really latched onto how things were described and sought to emulate it in my own writing.

the introduction i had to wuthering heights (despite all of its yikes) and the gothic genre/shakespeare in general really helped me refine the prose style that i have. which most on writeblr will always hear me describe as "flowery" because its just. extremely descriptive and i really love it. my general crusade in reading old books in the past year, and leaning more into this prose and into my love of history generally, has helped me develop complex and interesting stories that are chock full of the kind of prose that i adore and i've managed to create something of my own i think. a modern-flowery, because i can't think of another way to describe it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I read in October

Hoo boy, I sure did forget to post this earlier, didn't I!

Honestly I've been so busy so far this month that I just didn't even think of it. Also, this month is sort of evaporating. Before you ask, no I have written nothing at all for the not-NaNo that I was planning to attempt. But I did come up with another great idea for something that I'll probably start and not finish, so you can't say I've done nothing!

Anyway, on to the list:

Unfortunate Elements of My Anatomy, Hailey Piper ⭐���⭐️⭐️⭐️

Ghost Bird, Lisa Fuller ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Hound of the Baskervilles, Arthur Conan Doyle ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Forest of Stolen Girls, June Hur ⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Liar's Dice, Jeannie Lin ⭐️

Straya, Anthony O'Connor ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Toxic, Dan Kaszeta (nf) ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Illuminae, Amie Kaufman & Jay Kristoff ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Penhallow, Georgette Heyer ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Myth of the Self Made Man, Ruben Reyes Jr (ss) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Call, Christian White & Summer De Roche ⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Death of the Necromancer, Martha Wells ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Cretins, Thomas Ha (ss) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

Kill Your Brother, Jack Heath ⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley (nf) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

Valley of Terror, Zhou Haohui, tr. Bonnie Huie ⭐️⭐️

The Curse of the Burdens, John Wyndham ⭐️⭐️

Amazons, Adrienne Mayor (nf) ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Kraken Wakes, John Wyndham ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Dead Mountain, Donnie Eichar (nf) ⭐️⭐️

Family Business, Jonathan Sims ⭐️⭐️⭐️

Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

In the House of Aryaman A Lonely Signal Burns, Elizabeth Bear ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

A Blessing of Unicorns, Elizabeth Bear ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

METAtropolis Anthology ⭐️⭐️⭐️

Plan for Chaos, John Wyndham ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

A Fatal Thing Happened On the Way to the Forum, Emma Southon (nf) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Outward Urge, John Wyndham ⭐️⭐️

King Solomon's Mines, H. Rider Haggard DNF

The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle tr. David Ross (nf) ⭐️⭐️⭐️

This was a bit of a mixed bunch!

At the end of September I went to a writer's conference, where Lisa Fuller and Amie Kaufman were guests of honour. I was a bit annoyed at myself because I had bought Ghost Bird the week before, not realising that she was on the program, so I had the book the whole time but hadn't yet read it! Oh well, better late than never.

Ghost Bird was a solid spooky read, dealing with family history and tensions, small town disturbances, and the violent inheritances of colonialism and racism in Australia. I originally bought it because it was on a list of books to read if you enjoyed Catching Teller Crow by Ambelin Kwaymullina and Ezekiel Kwaymullina, which I did.

Illuminae was one that I had heard @slushrottweiler mention several times, but I'd never gotten around to it (YA, not my most favourite! Epistolary, not my most favourite!). But after the conference I figured I'd check it out, and I'm glad I did. While I wouldn't say that it's my favourite thing ever, it was a solid scifi story, with an interesting form and style, and I'll probably check out the sequels eventually.

Straya by Anthony O'Connor was the other book on this list that I picked up after the conference. Kind of a goofy action romp through post-apocalyptic Sydney, I was expecting to be a kind of brain-off funtime read (and it is! Don't get me wrong!) but it also had a lot of very clever little twists and turns that kept it really engaging. Also a refreshing take on the 'love interest' character, being that she's asexual, and when the protagonist confesses his feelings for her she says well... that's sweet and all, but I don't do that. Can we still be friends? And then they are still friends! A lot of the goofyness of this book is held up by a backbone of sincerity which is really nice, too. In all, a fun read.

Also revisited some faves this month, re-read Penhallow for my book club, and I have to say, it is one of those books which just gets more complex with each rereading. It's up there with Rebecca as some of my most books of all time.

There's one big fat DNF on the list this month, King Solomon's Mine, which through a combination of Victorian era racism, and very poor audio quality was pretty much unlistenable, and I don't think I'll be bothered trying to find a better recording.

And that's that!

nf= non fiction

ss= short story

stars awarded at my whim

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you please recommend some of your favourite romance novels that are well-written and have more complex plots? Thank you! ❤️

Of course! I'm giving you recommendations as if you've never heard of any of these in your life so forgive the basic Jane Austen mentions, I simply believe it's always necessary to recommend Jane Austen. Also, some of these are straight up romance and some of them just have well-written romance subplots that take a backseat to the overall story. Some of these are adult, some of these are YA, some of these are classics, some of these are contemporary, some of these are fantasy—hell, some of these are less a romance in the sense that there's a wonderful relationship and there's a happily ever after and more a deconstruction of human relationships and the complex romantic feelings that come from that. Pick which ones stick out most to you and research what most fits the vibe you want to read!

my personal recommendations.

persuasion by jane austen. (all of jane austen's books as well, but this is my favorite novel of all time)

atonement by ian mcewan.

wuthering heights by emily brontë.

book lovers by emily henry. (my favorite modern romance novel ever!)

deathless by catherynne m. valente.

the invisible life of addie larue by v.e. schwab.

the seven husbands of evelyn hugo by taylor jenkins reid.

the princess bride by william goldman.

the heart principle by helen hoang.

act your age, eve brown by talia hibbert.

jane eyre by charlotte brontë.

between shades of gray by ruta sepetys.

love, rosie by cecelia ahern.

seven days in june by tia williams.

conversations with friends by sally rooney.

the price of salt, or carol by patricia highsmith.

fingersmith by sarah waters.

tipping the velvet by sarah waters.

the time traveler's wife by audrey niffenegger.

carmilla by j. sheridan le fanu.

recommendations from friends that i haven't read yet.

the hundred lives of juliet by evelyn skye.

one true loves by taylor jenkins reid.

brooklyn by colm tóibín.

if you could see the sun by ann liang.

happy place by emily henry.

our wives under the sea by julia armfield.

funny you should ask by elissa sussman.

even though i knew the end by c.l. polk.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Thanks for the book recommendation.I love Greek Mythology.And great meta by the way.Jane Eyre is one of my favourites.I think I had read the meta back in the day.You know when s7 first started and val's character was introduced, I thought they were paralleling her with Bertha Mason since she was locked up in the prison world and Bertha in the attic.But then..well never mind.And there are some Hamlet-Ophelia/Stefan-Caroline parallels in s7 as well although not sure how intentional they were.Another thing was Defan's choice of women (Dopplegangers) having similarities with their mother.Oedipus Complex?

Anyway, I noticed this show did some cool book references over the seasons.In s1, it was Wuthering Heights,in s3 it was Moby Dick.I think Stefan had mentioned Fitzergerald's Great Gatsby being one his favourites in s1.

You're welcome Anon! If you like Greek mythology I highly recommend her books I also read The Song of Achilles which was one of the most beautifully written books I ever read, it made me cry so much. Yeah that meta was great, the account deactivated but I remember the user and she had some really great insight and posts during S6-8. God this just reminds me again of the wastedness of S7 because Dries was driven by spite rather than creativity because the way Stefan/Lily/Damon was set up in S6 looked so interesting and then it was completely neglected in S7. In 7x07 Damon even says "what is this Hamlet community theater" when Julian linked himself to Lily and then fights a duel with Enzo.

I think Dries did all that on purpose because if Lily was utilized to her ability she would have been similar to Katherine and how she was manipulating both brothers. Since Katherine was Dries' fave and she couldn't play with her anymore she held a grudge against Lily and I felt tried to make Val the new Katherine which didn't work at all. Lily was manipulative like Katherine and she knew how to play each brother differently but like Katherine she loved Stefan more. I wonder if Julie wanted to make Lily=Katherine and Sarah Salvatore=Elena in tone for that season but maybe when they changed everything for Candice's pregnancy and Sarah got dropped. Because like you said Lily and Sarah both looked like the doppelgangers with their long dark hair and doe eyes, especially Sarah when I rewatched S6 I was like wow she looks exactly like S1!Elena. Then Dries' made Val the center of the bros vs. heretics and she wasn't as strong of a character to do that with (plus she didn't care about Damon). Then the miscarriage revenge plot overtook everything that could have been done with Lily until they killed her an episode early, no I'm not bitter or anything.

Yeah they used to do that a lot with books, I think the Wuthering Heights mention was completely intentional since it's gothic romanticism and that's the tone of the show especially in S1. Plus the Catherine/Cathy vs. Katherine/Elena vibes, I'd say Damon is more Heathcliff than Stefan though. I think Moby Dick was brought up because of Stefan and everything he did to get revenge on Klaus and despite his obsession he never kills Klaus. Then there's the fact that he lets Elena drown which is kinda similar to Ahab getting dragged to the bottom of the ocean by Moby Dick. The Gatsby one is really interesting too because I don't think that was intentional foreshadowing (it was just establishing Stefan was a bookworm) but the 1920s flashbacks with Klefan and Stebekah had total Great Gatsby vibes. I would even say that Stefan was Gatsby because Klaus was intrigued (in love) with Stefan and how he taught him his favorite tricks. Rebekah would be Daisy and Klaus as Nick, I mean look at how obsessed those two were in trying to bring Ripper Stefan back in the day, it was like the obsession Daisy and Nick had over Gatsby.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why I love Wuthering Heights.

it's 2am and i read a review of WH by a person who so clearly missed the entire point, so here this is.

The thing that i absolutely love about this book is how flawed the characters are. You won't find a romantic hero who's perfect or a heroine you stan. Here are characters who are human beings and face the tragedy of being humans.

This is a book that is not afraid to show you the tragedy of human flaws, of generational trauma, of love.

The true beauty of Wuthering Heights lies in the demise.

I think the Oscar Wilde quote completely fits here "The books that the world call immoral are the books that show the world it's own shame."

So many people are bothered by the cycle of abuse depicted in this classic, saying it makes them uncomfortable. If you want vanilla, perfect boy falls for perfect girl and the only trouble they face is their parents, you will miss the entire plot of this book, and of human beings. Thankyou.

#wuthering heights is one of the most complex well written books#you clearly missed the point if you stopped reading just because you found the characters to be 'unlikeable'#wuthering heights#heathcliff#emily bronte#catherine earnshaw#cathy earnshaw#catherine#heathcliff and cathy#gothic tragedy#classic lit#classic literature#literaure#lit#literature#bronte sisters

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

Nihal for the character ask?

Favorite thing about them: As a person, what I like best about her is the kindness and concern she shows to the sick Beşir, even if she doesn't really care as deeply as she should. On a meta level, I like the sheer complexity and emotional depth of her character, so unexpected for a 12-to-15-year-old girl in a turn-of-the-20th-century novel written by a man. In a more conventional book, she would just be a sweet, innocent foil to her adulterous stepmother Bihter, but she's most definitely not. On the one hand, she's spoiled, bitter, often irrational, manipulative, and much too possessive. But on the other hand, we can sympathize with her pain at being "abandoned" by her loved ones, especially because her father's remarriage comes at the same time as (and is partly motivated by) her transition from a child to a young woman in society, with the expectation of soon leaving her home to marry some stranger. Add to these her assorted other qualities, like her cleverness and her moments of genuine kindness, and she arguably has the richest characterization in the entire book.

Least favorite thing about them: Well, if she were a real person, I'd dislike her spiteful, vindictive tendencies, but that's part of what makes her interesting. As a character... I'm tempted to agree with @ariel-seagull-wings about disliking the idea that her rivalry with Bihter was inevitable, that stepmothers and stepdaughters are always rivals. But since (unless I'm forgetting something) it's only Mademoiselle de Courton who says this, I'll argue that we the readers don't need to take that view, per se.

Three things I have in common with them:

*I'm uncomfortable with change.

*I'm sometimes afraid of abandonment.

*I like Classical music.

Three things I don't have in common with them:

*I don't have a stepmother.

*I've always been strong and healthy.

*I don't play the piano.

Favorite line: "Father, when a child becomes a young girl she finally becomes a bride, doesn’t she? Do you know? I have made a decision, a decision that can’t be changed: Little Nihal won’t become a bride. You know you used to ask me when I was little: You used to say, Nihal, who will you marry. I, doubtless with a a serious conviction, used to say: You. Don’t panic, now I am not of that opinion, but I will stay by your side, do you understand, father? Always together with you…”

brOTP: Bülent (when she's not acting like he betrayed her just by innocently calling Bihter "mother") and Mademoiselle de Courton.

In crossover-land, I might also like her to meet either of the two Catherines from Wuthering Heights – she shares traits with both, combining an upbringing more like Catherine Linton's with the selfishness, pathology, need for adoration, and (eventual) emotion-aggravated sickliness of Catherine Earnshaw, and dealing with the hard transition from girlhood to womanhood too. I don't know if they could ever be friends or if they'd hate each other, though.

OTP: None; she's not psychologically ready for romance and might never be.

nOTP: Behlül, or her father.

Random headcanon: Her illness is some form of epilepsy (her fainting spells are actually seizures), and she's on the autism spectrum too. After all, about 10% to 12% of people with ASD are also epileptic, and it would explain a lot about her personality: black and white thinking, dislike of change, not wanting to leave the safety of childhood, etc.

Unpopular opinion: If it's unpopular to think of her as a unique, complex, morally gray character, and not just an ingénue foil to Bihter, then that's my unpopular opinion. Although I think anyone who thinks she's a stock ingénue must either only know a bad adaptation, not the book, or else lack basic reading comprehension!

Song I associate with them: None at the moment.

Favorite picture of them: These pictures from @faintingheroine of Itır Esen in the 1975 TV version.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

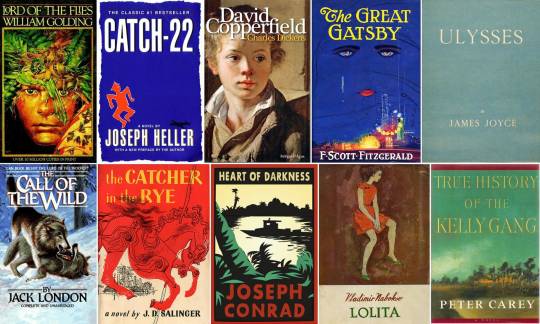

The 100 best novels written in English: the full list

After two years of careful consideration, Robert McCrum has reached a verdict on his selection of the 100 greatest novels written in English. Take a look at his list.

1. The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan (1678)

A story of a man in search of truth told with the simple clarity and beauty of Bunyan’s prose make this the ultimate English classic.

2. Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe (1719)

By the end of the 19th century, no book in English literary history had enjoyed more editions, spin-offs and translations. Crusoe’s world-famous novel is a complex literary confection, and it’s irresistible.

3. Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726)

A satirical masterpiece that’s never been out of print, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels comes third in our list of the best novels written in English

4. Clarissa by Samuel Richardson (1748)

Clarissa is a tragic heroine, pressured by her unscrupulous nouveau-riche family to marry a wealthy man she detests, in the book that Samuel Johnson described as “the first book in the world for the knowledge it displays of the human heart.”

5. Tom Jones by Henry Fielding (1749)

Tom Jones is a classic English novel that captures the spirit of its age and whose famous characters have come to represent Augustan society in all its loquacious, turbulent, comic variety.

6. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne (1759)

Laurence Sterne’s vivid novel caused delight and consternation when it first appeared and has lost little of its original bite.

7. Emma by Jane Austen (1816)

Jane Austen’s Emma is her masterpiece, mixing the sparkle of her early books with a deep sensibility.

8. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818)

Mary Shelley’s first novel has been hailed as a masterpiece of horror and the macabre.

9. Nightmare Abbey by Thomas Love Peacock (1818)

The great pleasure of Nightmare Abbey, which was inspired by Thomas Love Peacock’s friendship with Shelley, lies in the delight the author takes in poking fun at the romantic movement.

10. The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket by Edgar Allan Poe (1838)

Edgar Allan Poe’s only novel – a classic adventure story with supernatural elements – has fascinated and influenced generations of writers.

11. Sybil by Benjamin Disraeli (1845)

The future prime minister displayed flashes of brilliance that equalled the greatest Victorian novelists.

12. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847)

Charlotte Brontë’s erotic, gothic masterpiece became the sensation of Victorian England. Its great breakthrough was its intimate dialogue with the reader.

13. Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (1847)

Emily Brontë’s windswept masterpiece is notable not just for its wild beauty but for its daring reinvention of the novel form itself.

14. Vanity Fair by William Thackeray (1848)

William Thackeray’s masterpiece, set in Regency England, is a bravura performance by a writer at the top of his game.

15. David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (1850)

David Copperfield marked the point at which Dickens became the great entertainer and also laid the foundations for his later, darker masterpieces.

16. The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850)

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s astounding book is full of intense symbolism and as haunting as anything by Edgar Allan Poe.

17. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851)

Wise, funny and gripping, Melville’s epic work continues to cast a long shadow over American literature.

18. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865)

Lewis Carroll’s brilliant nonsense tale is one of the most influential and best loved in the English canon.

19. The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (1868)

Wilkie Collins’s masterpiece, hailed by many as the greatest English detective novel, is a brilliant marriage of the sensational and the realistic.

20. Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868-9)

Louisa May Alcott’s highly original tale aimed at a young female market has iconic status in America and never been out of print.

21. Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871-2)

This cathedral of words stands today as perhaps the greatest of the great Victorian fictions.

22. The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope (1875)

Inspired by the author’s fury at the corrupt state of England, and dismissed by critics at the time, The Way We Live Now is recognised as Trollope’s masterpiece.

23. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1884/5)

Mark Twain’s tale of a rebel boy and a runaway slave seeking liberation upon the waters of the Mississippi remains a defining classic of American literature.

24. Kidnapped by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

A thrilling adventure story, gripping history and fascinating study of the Scottish character, Kidnapped has lost none of its power.

25. Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K Jerome (1889)

Jerome K Jerome’s accidental classic about messing about on the Thames remains a comic gem.

26. The Sign of Four by Arthur Conan Doyle (1890)

Sherlock Holmes’s second outing sees Conan Doyle’s brilliant sleuth – and his bluff sidekick Watson – come into their own.

27. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1891)

Wilde’s brilliantly allusive moral tale of youth, beauty and corruption was greeted with howls of protest on publication.

28. New Grub Street by George Gissing (1891)

George Gissing’s portrayal of the hard facts of a literary life remains as relevant today as it was in the late 19th century.

29. Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy (1895)

Hardy exposed his deepest feelings in this bleak, angry novel and, stung by the hostile response, he never wrote another.

30. The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane (1895)

Stephen Crane’s account of a young man’s passage to manhood through soldiery is a blueprint for the great American war novel.

31. Dracula by Bram Stoker (1897)

Bram Stoker’s classic vampire story was very much of its time but still resonates more than a century later.

32. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

Joseph Conrad’s masterpiece about a life-changing journey in search of Mr Kurtz has the simplicity of great myth.

33. Sister Carrie by Theodore Dreiser (1900)

Theodore Dreiser was no stylist, but there’s a terrific momentum to his unflinching novel about a country girl’s American dream.

34. Kim by Rudyard Kipling (1901)

In Kipling’s classic boy’s own spy story, an orphan in British India must make a choice between east and west.

35. The Call of the Wild by Jack London (1903)

Jack London’s vivid adventures of a pet dog that goes back to nature reveal an extraordinary style and consummate storytelling.

36. The Golden Bowl by Henry James (1904)

American literature contains nothing else quite like Henry James’s amazing, labyrinthine and claustrophobic novel.

37. Hadrian the Seventh by Frederick Rolfe (1904)

This entertaining if contrived story of a hack writer and priest who becomes pope sheds vivid light on its eccentric author – described by DH Lawrence as a “man-demon”.

38. The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (1908)

The evergreen tale from the riverbank and a powerful contribution to the mythology of Edwardian England.

39. The History of Mr Polly by HG Wells (1910)

The choice is great, but Wells’s ironic portrait of a man very like himself is the novel that stands out.

40. Zuleika Dobson by Max Beerbohm (1911)

The passage of time has conferred a dark power upon Beerbohm’s ostensibly light and witty Edwardian satire.

41. The Good Soldier by Ford Madox Ford (1915)

Ford’s masterpiece is a searing study of moral dissolution behind the facade of an English gentleman – and its stylistic influence lingers to this day.

42. The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan (1915)

John Buchan’s espionage thriller, with its sparse, contemporary prose, is hard to put down.

43. The Rainbow by DH Lawrence (1915)

The Rainbow is perhaps DH Lawrence’s finest work, showing him for the radical, protean, thoroughly modern writer he was.

44. Of Human Bondage by W Somerset Maugham (1915)

Somerset Maugham’s semi-autobiographical novel shows the author’s savage honesty and gift for storytelling at their best.

45. The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (1920)

The story of a blighted New York marriage stands as a fierce indictment of a society estranged from culture.

46. Ulysses by James Joyce (1922)

This portrait of a day in the lives of three Dubliners remains a towering work, in its word play surpassing even Shakespeare.

47. Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis (1922)

What it lacks in structure and guile, this enthralling take on 20s America makes up for in vivid satire and characterisation.

48. A Passage to India by EM Forster (1924)

EM Forster’s most successful work is eerily prescient on the subject of empire.

49. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes by Anita Loos (1925)

A guilty pleasure it may be, but it is impossible to overlook the enduring influence of a tale that helped to define the jazz age.

50. Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf (1925)

Woolf’s great novel makes a day of party preparations the canvas for themes of lost love, life choices and mental illness.

51. The Great Gatsby by F Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

Fitzgerald’s jazz age masterpiece has become a tantalising metaphor for the eternal mystery of art.

52. Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1926)

A young woman escapes convention by becoming a witch in this original satire about England after the first world war.

53. The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway (1926)

Hemingway’s first and best novel makes an escape to 1920s Spain to explore courage, cowardice and manly authenticity.

54. The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett (1929)

Dashiell Hammett’s crime thriller and its hard-boiled hero Sam Spade influenced everyone from Chandler to Le Carré.

55. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (1930)

The influence of William Faulkner’s immersive tale of raw Mississippi rural life can be felt to this day.

56. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932)

Aldous Huxley’s vision of a future human race controlled by global capitalism is every bit as prescient as Orwell’s more famous dystopia.

57. Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons (1932)

The book for which Gibbons is best remembered was a satire of late-Victorian pastoral fiction but went on to influence many subsequent generations.

58. Nineteen Nineteen by John Dos Passos (1932)

The middle volume of John Dos Passos’s USA trilogy is revolutionary in its intent, techniques and lasting impact.

59. Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller (1934)

The US novelist’s debut revelled in a Paris underworld of seedy sex and changed the course of the novel – though not without a fight with the censors.

60. Scoop by Evelyn Waugh (1938)

Evelyn Waugh’s Fleet Street satire remains sharp, pertinent and memorable.

61. Murphy by Samuel Beckett (1938)

Samuel Beckett’s first published novel is an absurdist masterpiece, a showcase for his uniquely comic voice.

62. The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler (1939)

Raymond Chandler’s hardboiled debut brings to life the seedy LA underworld – and Philip Marlowe, the archetypal fictional detective.

63. Party Going by Henry Green (1939)

Set on the eve of war, this neglected modernist masterpiece centres on a group of bright young revellers delayed by fog.

64. At Swim-Two-Birds by Flann O’Brien (1939)

Labyrinthine and multilayered, Flann O’Brien’s humorous debut is both a reflection on, and an exemplar of, the Irish novel.

65. The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck (1939)

One of the greatest of great American novels, this study of a family torn apart by poverty and desperation in the Great Depression shocked US society.

66. Joy in the Morning by PG Wodehouse (1946)

PG Wodehouse’s elegiac Jeeves novel, written during his disastrous years in wartime Germany, remains his masterpiece.

67. All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren (1946)

A compelling story of personal and political corruption, set in the 1930s in the American south.

68. Under the Volcano by Malcolm Lowry (1947)

Malcolm Lowry’s masterpiece about the last hours of an alcoholic ex-diplomat in Mexico is set to the drumbeat of coming conflict.

69. The Heat of the Day by Elizabeth Bowen (1948)

Elizabeth Bowen’s 1948 novel perfectly captures the atmosphere of London during the blitz while providing brilliant insights into the human heart.

70. Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell (1949)

George Orwell’s dystopian classic cost its author dear but is arguably the best-known novel in English of the 20th century.

71. The End of the Affair by Graham Greene (1951)

Graham Greene’s moving tale of adultery and its aftermath ties together several vital strands in his work.

72. The Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger (1951)

JD Salinger’s study of teenage rebellion remains one of the most controversial and best-loved American novels of the 20th century.

73. The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow (1953)

In the long-running hunt to identify the great American novel, Saul Bellow’s picaresque third book frequently hits the mark.

74. Lord of the Flies by William Golding (1954)

Dismissed at first as “rubbish & dull”, Golding’s brilliantly observed dystopian desert island tale has since become a classic.

75. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (1955)

Nabokov’s tragicomic tour de force crosses the boundaries of good taste with glee.

76. On the Road by Jack Kerouac (1957)

The creative history of Kerouac’s beat-generation classic, fuelled by pea soup and benzedrine, has become as famous as the novel itself.

77. Voss by Patrick White (1957)

A love story set against the disappearance of an explorer in the outback, Voss paved the way for a generation of Australian writers to shrug off the colonial past.

78. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee (1960)

Her second novel finally arrived this summer, but Harper Lee’s first did enough alone to secure her lasting fame, and remains a truly popular classic.

79. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark (1960)

Short and bittersweet, Muriel Spark’s tale of the downfall of a Scottish schoolmistress is a masterpiece of narrative fiction.

80. Catch-22 by Joseph Heller (1961)

This acerbic anti-war novel was slow to fire the public imagination, but is rightly regarded as a groundbreaking critique of military madness.

81. The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing (1962)

Hailed as one of the key texts of the women’s movement of the 1960s, this study of a divorced single mother’s search for personal and political identity remains a defiant, ambitious tour de force.

82. A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962)

Anthony Burgess’s dystopian classic still continues to startle and provoke, refusing to be outshone by Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant film adaptation.

83. A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood (1964)

Christopher Isherwood’s story of a gay Englishman struggling with bereavement in LA is a work of compressed brilliance.

84. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote (1966)

Truman Capote’s non-fiction novel, a true story of bloody murder in rural Kansas, opens a window on the dark underbelly of postwar America.

85. The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1966)

Sylvia Plath’s painfully graphic roman à clef, in which a woman struggles with her identity in the face of social pressure, is a key text of Anglo-American feminism.

86. Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth (1969)

This wickedly funny novel about a young Jewish American’s obsession with masturbation caused outrage on publication, but remains his most dazzling work.

87. Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor (1971)

Elizabeth Taylor’s exquisitely drawn character study of eccentricity in old age is a sharp and witty portrait of genteel postwar English life facing the changes taking shape in the 60s.

88. Rabbit Redux by John Updike (1971)

Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, Updike’s lovably mediocre alter ego, is one of America’s great literary protoganists, up there with Huck Finn and Jay Gatsby.

89. Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison (1977)

The novel with which the Nobel prize-winning author established her name is a kaleidoscopic evocation of the African-American experience in the 20th century.

90. A Bend in the River by VS Naipaul (1979)

VS Naipaul’s hellish vision of an African nation’s path to independence saw him accused of racism, but remains his masterpiece.

91. Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie (1981)

The personal and the historical merge in Salman Rushdie’s dazzling, game-changing Indian English novel of a young man born at the very moment of Indian independence.

92. Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson (1981)

Marilynne Robinson’s tale of orphaned sisters and their oddball aunt in a remote Idaho town is admired by everyone from Barack Obama to Bret Easton Ellis.

93. Money: A Suicide Note by Martin Amis (1984)

Martin Amis’s era-defining ode to excess unleashed one of literature’s greatest modern monsters in self-destructive antihero John Self.

94. An Artist of the Floating World by Kazuo Ishiguro (1986)

Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel about a retired artist in postwar Japan, reflecting on his career during the country’s dark years, is a tour de force of unreliable narration.

95. The Beginning of Spring by Penelope Fitzgerald (1988)

Fitzgerald’s story, set in Russia just before the Bolshevik revolution, is her masterpiece: a brilliant miniature whose peculiar magic almost defies analysis.

96. Breathing Lessons by Anne Tyler (1988)

Anne Tyler’s portrayal of a middle-aged, mid-American marriage displays her narrative clarity, comic timing and ear for American speech to perfection.

97. Amongst Women by John McGahern (1990)

This modern Irish masterpiece is both a study of the faultlines of Irish patriarchy and an elegy for a lost world.

98. Underworld by Don DeLillo (1997)

A writer of “frightening perception”, Don DeLillo guides the reader in an epic journey through America’s history and popular culture.

99. Disgrace by JM Coetzee (1999)

In his Booker-winning masterpiece, Coetzee’s intensely human vision infuses a fictional world that both invites and confounds political interpretation.

100. True History of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey (2000)

Peter Carey rounds off our list of literary milestones with a Booker prize-winning tour-de-force examining the life and times of Australia’s infamous antihero, Ned Kelly.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Doll Factory

Author: Elizabeth Macneal

First published: 2019

Pages: 336

Rating: ★★★★★

How long did it take: 3 days

I felt that this book, while perhaps not exceptional, was very well put together. It was paced just right and the sense of growing dread escalates in a way which kept me glued to the page. Truly well written historical fiction.

Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife

Author: Bart D. Ehrman

First published: 2020

Pages: 352

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 2 days

I am rather conflicted about this book. Firstly, as a Christian bordering on agnosticism (I have never been a part of any church and my family is completely atheistic), I felt both somehow comforted by Ehrman´s deductions and somewhat resentful at the same time. Not because he very convincingly talks about the changing of religious perspectives (I am a historian myself so that information was only natural), but because he is clearly working with the notion of non-existence of God, not really treating it as a possibility. That, however, is my own personal issue. Objectively speaking, this is a very good book. Though academic in tone, it reads quite easily and is obviously well researched. The title, however, is misleading. Like many others, I had expected this to be a study of VARIOUS theories of afterlives, but 80% of the book is focused on early Christianity only. Not that isn´t fascinating, but for people hoping to learn something about other religions and cultures and their post-mortem ideas, it can only represent a big disappointment. So - know what you are getting, have an open mind and you might find this book a worthy addition to your personal library.

Wuthering Heights The Graphic Novel

Author: Emily Brontë, John M. Burns

First published: 2011

Pages: 160

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 1 day

I don´t think there is much to review. I love the original book. I enjoyed its re-imagining here.

The Vanishing

Author: Sophia Tobin

First published: 2017

Pages: 390

Rating: ★★☆☆☆

How long did it take: 3 days

This was sort of OK I guess??? The beginning was promising, but I lost interest in the latter half, which also became somewhat convoluted. Not very memorable, though Sophia Tobin´s writing style is fine. I would not mind trying another book by her in the future.

The Mercies

Author: Kiran Millwood Hargrave

First published: 2020

Pages: 352

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 7 days

Stunningly-written and deeply moving, this book has really only one weakness. It somewhat drags in the middle. But the atmosphere is alive and palpable and the emotions pure and real. There are many other books dealing with the topic of witch-trials, but few manage to be as powerful as well as respectfully restrained. Hargrave as an author knows how to keep the balance and her book beautiful.

The Wizard of Oz and Other Wonderful Books of Oz: The Emerald City of Oz and Glinda of Oz

Author: Frank L. Baum

First published: 1900, 1910, 1920

Pages: 432

Rating: ★★★☆☆

How long did it take: 5 days

This book is not commonly known in my country and so I have only read it for the first time now when I am over thirty. It definitely has its charm, especially the first volume, which holds some beautiful truths one wishes to teach the children (or adults). The Emerald City of Oz and Glinda of Oz are both mostly just a flight of fancy with no actual conflict. In fact, the danger to any of the characters is so nonexistent it begs the question of "why should I care". Not bad, but perhaps I would have loved it more if I was 5, not 33. Mea culpa.

Vasilisa the Wise and Other Tales of Brave Young Women

Author: Kate Forsyth

First published: 2017

Pages: 103

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 1 day

Very sweet retelling of several classic fairytales in which the girl saves herself (even if she needs some help by others, and the others are never the prince).

S.

Author: J.J. Abrams, Doug Dorst

First published: 2013

Pages: 456

Rating: ★★★★★

How long did it take: 19 days

This book felt like an acid trip with Umberto Eco or something in a similar vein to me. I was rather terrified that the whole thing would be completely dependant on the unusual format, but to my delight, the format merely enhances and enriches the actual novel, which in itself is dark, confusing, moving, terrifying, philosophical and weirdly fascinating. I am sure a lot has escaped my attention or flew over my head, but I welcome it because it gives me more reason to return to the book in the future.

It was not all flawless though. My biggest gripe, as an actual Czech person, is that even though so much effort and thought went into the creation of this book, the author decided that Google translate will do just fine - and no surprise - it did not. There are not many instances of the Czech language being used, but when it is... it is all wrong. The Czech language is quite difficult and complex and Google translate does not know how to deal with it most of the time. Just one example: In the book, Eric writes OPICE TANCE on the wall and says it is Czech for "MONKEY DANCES". Yeah. Yeah, it is. IF THE WORD "DANCES" IS TAKEN AS A NOUN IN PLURAL. The correct translation would be "OPICE TANČÍ" and trust me it IS a big big difference. (Do not get me started on the vintage newspaper article....)

You definitely need a lot of brainpower and focus when reading, this is not an easy book to follow. You also need to accept that not all questions are answered. I am glad I read it though. I found it an interesting experience.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

Author: J.R.R. Tolkien

First published: 1954

Pages: 407

Rating: ★★★★★

How long did it take: 3 days

What can I say? Yet again I had goosebumps and tears in my eyes. Few, very few books have the power of this one.

Mexican Gothic

Author: Silvia Moreno-Garcia

First published: 2020

Pages: 301

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 12 days

I don´t have much to say but I was a bit bored at the beginning, but it turned out to be a pretty wild ride.

Aristokratka u královského dvora

Author: Evžen Boček

First published: 2020

Pages: 184

Rating: ★★★☆☆

How long did it take: 1 day

Miluji celou tuto sérii, bohužel tento díl mi, ač stále zábavný, přišel prozatím nejslabší... Měla jsem pocit, že první polovina knihy opustila můj oblíbený, laskavý humor teenagerky, která se musí potýkat s výstřední rodinou a situací, a sklouzává spíše trochu k upřímné krutosti... Doufám, že další pokračování se vrátí ke své laskavosti.

The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family and Defiance During the Blitz

Author: Erik Larson

First published: 2020

Pages: 608

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 2 days

An excellent and above all readable account of a chapter in the WW2 history. Larson explains well why Churchill was the best man for that dark hour and why he is still viewed as a hero in Europe (his questionable and even abhorrent views and actions in the context of the British Empire and people of other races notwithstanding), as the person who stood up to Hitler and pretty much kept the fires of defiance burning. There is definitely not enough "family" in this "family saga", but given the sheer amount of material and information presented to the reader, I suppose the author struck an acceptable balance between the politics and the private matters.

Conjure Women

Author: Afia Atakora

First published: 2020

Pages: 416

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 8 days

The beginning of this book seemed tiring, and at risk of sounding insensitive, not interesting, since it seemed to tackle the same things that have already been tackled. But then there appeared strands of stories and of secrets, and suddenly I just needed to know everything. The whole story then appears as an artful mosaic. The last chapter felt unnecessary though and I did not understand its meaning if it was supposed to have any.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

...

I sometimes hear people complain that classic literature is the realm of dead white men. And it’s certainly true that men have tended to dominate the canon of literature taught in schools. But women have been writing great books for centuries. In fact, you could probably spend a lifetime just reading great classics by women and never run out of reading material.

This list is just a sampling of great books written by women of the past. For the purposes of this list, I’ve defined classics as books that are more than 50 years old. The list of classics by women focuses on novels, but there are some plays, poems, and works of nonfiction as well. And I’ve tried to include some well-known favorites, as well as more obscure books. Whatever your reading preferences, you’re bound to find something to enjoy here. So step back in time and listen to the voices of women who came before us.

The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon (990s-1000s). “Moving elegantly across a wide range of themes including nature, society, and her own flirtations, Sei Shōnagon provides a witty and intimate window on a woman’s life at court in classical Japan.”

The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (Before 1021). “Genji, the Shining Prince, is the son of an emperor. He is a passionate character whose tempestuous nature, family circumstances, love affairs, alliances, and shifting political fortunes form the core of this magnificent epic.”

Oroonoko by Aphra Behn (1688). “When Prince Oroonoko’s passion for the virtuous Imoinda arouses the jealousy of his grandfather, the lovers are cast into slavery and transported from Africa to the colony of Surinam.”

Phillis Wheatley, Complete Writings by Phillis Wheatley (1760s-1770s). “This volume collects both Wheatley’s letters and her poetry: hymns, elegies, translations, philosophical poems, tales, and epyllions.”

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft (1790). “Arguably the earliest written work of feminist philosophy, Wollstonecraft produced a female manifesto in the time of the American and French Revolutions.”

The Romance of the Forest by Ann Radcliffe (1791). “A beautiful, orphaned heiress, a dashing hero, a dissolute, aristocratic villain, and a ruined abbey deep in a great forest are combined by the author in a tale of suspense where danger lurks behind every secret trap-door.”

Camilla by Fanny Burney (1796). “Camilla deals with the matrimonial concerns of a group of young people … The path of true love, however, is strewn with intrigue, contretemps and misunderstanding.”

Belinda by Maria Edgeworth (1801). “Contending with the perils and the varied cast of characters of the marriage market, Belinda strides resolutely toward independence. … Edgeworth tackles issues of gender and race in a manner at once comic and thought-provoking. ”

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818). “Driven by ambition and an insatiable thirst for scientific knowledge, Victor Frankenstein … fashions what he believes to be the ideal man from a grotesque collection of spare parts, breathing life into it through a series of ghastly experiments.”

Persuasion by Jane Austen (1818). “Eight years ago, Anne Elliot fell in love with poor but ambitious naval officer Captain Frederick Wentworth … now, on the verge of spinsterhood, Anne re-encounters Frederick Wentworth as he courts her spirited young neighbour, Louisa Musgrove.”

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847). “Having grown up an orphan in the home of her cruel aunt and at a harsh charity school, Jane Eyre becomes an independent and spirited survivor …. But when she finds love with her sardonic employer, Rochester, the discovery of his terrible secret forces her to make a choice. “

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (1847). “One of the great novels of the nineteenth century, Emily Brontë’s haunting tale of passion and greed remains unsurpassed in its depiction of destructive love.”

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë (1848). “A powerful and sometimes violent novel of expectation, love, oppression, sin, religion and betrayal. It portrays the disintegration of the marriage of Helen Huntingdon … and her dissolute, alcoholic husband.”

The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts (mid-19th century). “Tells the story of Hannah Crafts, a young slave working on a wealthy North Carolina plantation, who runs away in a bid for freedom up North.”

Sonnets from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1850). “Recognized for their Victorian tradition and discipline, these are some of the most passionate and memorable love poems in the English language.”

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1852). “Selling more than 300,000 copies the first year it was published, Stowe’s powerful abolitionist novel fueled the fire of the human rights debate.”

North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell (1854). “As relevant now as when it was first published, Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South skillfully weaves a compelling love story into a clash between the pursuit of profit and humanitarian ideals.”

Our Nig by Harriet E. Wilson (1859). “In the story of Frado, a spirited black girl who is abused and overworked as the indentured servant to a New England family, Harriet E. Wilson tells a heartbreaking story about the resilience of the human spirit.”

The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot (1860). “Strong-willed, compassionate, and intensely loyal, Maggie seeks personal happiness and inner peace but risks rejection and ostracism in her close-knit community.”

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs (1861). “The remarkable odyssey of Harriet Jacobs (1813–1897) whose dauntless spirit and faith carried her from a life of servitude and degradation in North Carolina to liberty and reunion with her children in the North.”

The Curse of Caste, or The Slave Bride by Julia C. Collins (1865). “Focuses on the lives of a beautiful mixed-race mother and daughter whose opportunities for fulfillment through love and marriage are threatened by slavery and caste prejudice.”

Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House by Elizabeth Keckley (1868). “Traces Elizabeth Keckley’s life from her enslavement in Virginia and North Carolina to her time as seamstress to Mary Todd Lincoln in the White House during Abraham Lincoln’s administration.”

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868). “The four March sisters couldn’t be more different. But with their father away at war, and their mother working to support the family, they have to rely on one another.”

A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains by Isabella Lucy Bird (1879). “In 1873, wearing Hawaiian riding dress, [Bird] rode her horse through the American Wild West, a terrain only newly opened to pioneer settlement.”

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson by Emily Dickinson (1890). “Though generally overlooked during her lifetime, Emily Dickinson’s poetry has achieved acclaim due to her experiments in prosody, her tragic vision and the range of her emotional and intellectual explorations.”

The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1892). “The story depicts the effect of under-stimulation on the narrator’s mental health and her descent into psychosis. With nothing to stimulate her, she becomes obsessed by the pattern and color of the wallpaper.”

Iola Leroy by Frances E.W. Harper (1892). “The daughter of a wealthy Mississippi planter, Iola Leroy led a life of comfort and privilege, never guessing at her mixed-race ancestry — until her father died and a treacherous relative sold her into slavery.”

The Grasmere and Alfoxden Journals by Dorothy Wordsworth (1897). “Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals are a unique record of her life with her brother William, at the time when he was at the height of his poetic powers.”

The Awakening by Kate Chopin (1899). “Chopin’s daring portrayal of a woman trapped in a stifling marriage, who seeks and finds passionate physical love outside the straitened confines of her domestic situation.”

The Light of Truth: Writings of an Anti-Lynching Crusader by Ida B. Wells (late 19th century). “This volume covers the entire scope of Wells’s remarkable career, collecting her early writings, articles exposing the horrors of lynching, essays from her travels abroad, and her later journalism.”

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1902). “Transformed from princess to pauper, [Sarah Crewe] must swap dancing lessons and luxury for hard work and a room in the attic.”

The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy (1905). “The French Revolution, driven to excess by its own triumph, has turned into a reign of terror. … Thus the stage is set for one of the most enthralling novels of historical adventure ever written.”

A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter (1909). “The story is one of Elnora’s struggles to overcome her poverty; to win the love of her mother, who blames Elnora for her husband’s death; and to find a romantic love of her own.”

Mrs Spring Fragrance: A Collection of Chinese-American Short Stories by Sui Sin Far (1910s). “In these deceptively simple fables of family life, Sui Sin Far offers revealing views of life in Seattle and San Francisco at the turn of the twentieth century.”

American Indian Stories, Legends, and Other Writings by Zitkala-Sa (1910). “Tapping her troubled personal history, Zitkala-Sa created stories that illuminate the tragedy and complexity of the American Indian experience.”

The Custom of the Country by Edith Wharton (1913). Undine Spragg’s “rise to the top of New York’s high society from the nouveau riche provides a provocative commentary on the upwardly mobile and the aspirations that eventually cause their ruin.”

Oh Pioneers by Willa Cather (1913). “Evoking the harsh grandeur of the prairie, this landmark of American fiction unfurls a saga of love, greed, murder, failed dreams, and hard-won triumph.”

Suffragette: My Own Story by Emmeline Pankhurst (1914). “With insight and great wit, Emmeline’s autobiography chronicles the beginnings of her interest in feminism through to her militant and controversial fight for women’s right to vote.”

The Enchanted April by Elizabeth von Arnim (1922). Four women who “are alike only in their dissatisfaction with their everyday lives … find each other—and the castle of their dreams—through a classified ad in a London newspaper one rainy February afternoon.”

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1924). “Evangeline Knapp is the perfect, compulsive housekeeper, while her husband, Lester, is a poet and a dreamer. Suddenly, through a nearly fata accident, their roles are reversed.”

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf (1925). “Direct and vivid in her account of Clarissa Dalloway’s preparations for a party, Virginia Woolf explores the hidden springs of thought and action in one day of a woman’s life.”

The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928). “First published in 1928, this timeless portrayal of lesbian love is now a classic. The thinly disguised story of Hall’s own life, it was banned outright upon publication and almost ruined her literary career.”

Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928). “Written in 1929 at the height of the Harlem Renaissance by one of the movement’s most important and prolific authors, Plum Bun is the story of Angela Murray, a young black girl who discovers she can pass for white.”

Passing by Nella Larsen (1929). “Clare Kendry leads a dangerous life. Fair, elegant, and ambitious, she is married to a white man unaware of her African American heritage, and has severed all ties to her past.”

Grand Hotel by Vicki Baum (1929). “A grand hotel in the center of 1920s Berlin serves as a microcosm of the modern world in Vicki Baum’s celebrated novel, a Weimar-era best seller that retains all its verve and luster today.”

Thus Were Their Faces: Selected Stories by Silvina Ocampo (1930s-1970s). “Tales of doubles and impostors, angels and demons, a marble statue of a winged horse that speaks, a beautiful seer who writes the autobiography of her own death, a lapdog who records the dreams of an old woman, a suicidal romance, and much else that is incredible, mad, sublime, and delicious.”

Strong Poison by Dorothy L. Sayers (1930). “Sayers introduces Harriet Vane, a mystery writer who is accused of poisoning her fiancé and must now join forces with Lord Peter Wimsey to escape a murder conviction and the hangman’s noose.”

All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West (1931). “When Lady Slane was young, she nurtured a secret, burning ambition: to become an artist. She became, instead, the dutiful wife of a great statesman, and mother to six children. In her widowhood she finally defies her family.”

Invitation to the Waltz by Rosamond Lehmann (1932). Olivia Curtis “anticipates her first dance, the greatest yet most terrifying event of her restricted social life, with tremulous uncertainty and excitement.”

Frost in May by Antonia White (1933). “Nanda Gray, the daughter of a Catholic convert, is nine when she is sent to the Convent of Five Wounds. Quick-witted, resilient, and eager to please, she adapts to this cloistered world, learning rigid conformity and subjection to authority.”

Miss Buncle’s Book by D.E. Stevenson (1934). “Times are harsh, and Barbara’s bank account has seen better days. Maybe she could sell a novel … if she knew any stories. Stumped for ideas, Barbara draws inspiration from her fellow residents of Silverstream.”

The Wine of Solitude by Irene Nemirovsky (1935). “Beginning in a fictionalized Kiev, The Wine of Solitude follows the Karol family through the Great War and the Russian Revolution, as the young Hélène grows from a dreamy, unhappy child into a strongwilled young woman.”

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell (1936). “Gone With the Wind explores the depth of human passions with an intensity as bold as its setting in the red hills of Georgia. A superb piece of storytelling, it vividly depicts the drama of the Civil War and Reconstruction.”

After Midnight by Irmgard Keun (1937). “German author Irmgard Keun had only recently fled Nazi Germany with her lover Joseph Roth when she wrote this slim, exquisite, and devastating book. It captures the unbearable tension, contradictions, and hysteria of pre-war Germany like no other novel.”

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (1937). “One of the most important and enduring books of the twentieth century, Their Eyes Were Watching God brings to life a Southern love story with the wit and pathos found only in the writing of Zora Neale Hurston.”

Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day by Winifred Watson (1938). “Miss Pettigrew is a governess sent by an employment agency to the wrong address, where she encounters a glamorous night-club singer, Miss LaFosse.”

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen (1938). “The orphaned Portia is stranded in the sophisticated and politely treacherous world of her wealthy half-brother’s home in London. There she encounters the attractive, carefree cad Eddie.

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie (1939). “Ten strangers are lured to an isolated island mansion off the Devon coast by a mysterious U. N. Owen … By the end of the night one of the guests is dead.”

Mariana by Monica Dickens (1940). “We see Mary at school in Kensington and on holiday in Somerset; her attempt at drama school; her year in Paris learning dressmaking and getting engaged to the wrong man; her time as a secretary and companion; and her romance with Sam.”

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers (1940). “Wonderfully attuned to the spiritual isolation that underlies the human condition, and with a deft sense for racial tensions in the South, McCullers spins a haunting, unforgettable story that gives voice to the rejected, the forgotten, and the mistreated.”

The Man Who Loved Children by Christina Stead (1940). “Sam and Henny Pollit have too many children, too little money, and too much loathing for each other. As Sam uses the children’s adoration to feed his own voracious ego, Henny watches in bleak despair.”

The Bird in the Tree by Elizabeth Goudge (1940). “The Bird in the Tree takes place in England in 1938, and follows a close-knit family whose tranquil existence is suddenly threatened by a forbidden love.”

Anne Frank: A Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank (1942-1944). “Discovered in the attic in which she spent the last years of her life, Anne Frank’s remarkable diary has since become a world classic—a powerful reminder of the horrors of war and an eloquent testament to the human spirit.”

The Robber Bridegroom by Eudora Welty (1942). “Legendary figures of Mississippi’s past—flatboatman Mike Fink and the dreaded Harp brothers—mingle with characters from Eudora Welty’s own imagination in an exuberant fantasy set along the Natchez Trace.”

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith (1943). “The story of young, sensitive, and idealistic Francie Nolan and her bittersweet formative years in the slums of Williamsburg has enchanted and inspired millions of readers for more than sixty years.”

Nada by Carmen LeFloret (1944). “One of the most important literary works of post-Civil War Spain, Nada is the semi-autobiographical story of an orphaned young woman who leaves her small town to attend university in war-ravaged Barcelona.

The Pursuit of Love by Nancy Mitford (1945). “The Pursuit of Love follows the travails of Linda, the most beautiful and wayward Radlett daughter, who falls first for a stuffy Tory politician, then an ardent Communist, and finally a French duke named Fabrice.”

One Fine Day by Mollie Panter-Downes (1947). “This subtle, finely wrought novel presents a memorable portrait of the aftermath of war, its effect upon a marriage, and the gradual but significant change in the nature of English middle-class life.”

Family Roundabout by Richmal Crompton (1948). “We see that families can both entrap and sustain; that parents and children must respect each other; and that happiness necessitates jumping or being pushed off the family roundabout.”

The Living Is Easy by Dorothy West (1948). “Cleo Judson—daughter of southern sharecroppers and wife of ‘Black Banana King’ Bart Judson … seeks to recreate her original family by urging her sisters and their children to live with her, while rearing her daughter to be a member of Boston’s black elite.”

Half a Lifelong Romance by Eileen Chang (1948). “Shen Shijun, a young engineer, has fallen in love with his colleague, the beautiful Gu Manzhen. … But dark circumstances—a lustful brother-in-law, a treacherous sister, a family secret—force the two young lovers apart. “

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith (1948). “Tells the story of seventeen-year-old Cassandra and her family, who live in not-so-genteel poverty in a ramshackle old English castle. Here she strives, over six turbulent months, to hone her writing skills.”

Pinjar: The Skeleton and Other Stories by Amrita Pritam (1950). “Two of the most moving novels by one of India’s greatest women writers. The Skeleton …is memorable for its lyrical style and depth in her writing. … The Man is a compelling account of a young man born under strange circumstances and abandoned at the altar of God.”

My Cousin Rachel by Daphne du Maurier (1951). “While in Italy, Ambrose fell in love with Rachel, a beautiful English and Italian woman. But the final, brief letters Ambrose wrote hint that his love had turned to paranoia and fear. Now Rachel has arrived at Philip’s newly inherited estate.”

The Daughter of Time by Josephine Tey (1951). “Inspector Alan Grant of Scotland Yard, recuperating from a broken leg, becomes fascinated with a contemporary portrait of Richard III that bears no resemblance to the Wicked Uncle of history.”

Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (1952). “As Mildred gets embroiled in the lives of her new neighbors … the novel presents a series of snapshots of human life as actually, and pluckily, lived in a vanishing world of manners and repressed desires.”

Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks (1953). “In a novel that captures the essence of Black life, Brooks recognizes the beauty and strength that lies within each of us.”

Someone at a Distance by Dorothy Whipple (1953). “Ellen was that unfashionable creature, a happy housewife struck by disaster when the husband, in a moment of weak, mid-life vanity, runs off with a French girl.”

Nisei Daughter by Monica Sone (1953). “With charm, humor, and deep understanding, Monica Sone tells what it was like to grow up Japanese American on Seattle’s waterfront in the 1930s and to be subjected to ‘relocation’ during World War II.”

Cotillion by Georgette Heyer (1953). “Country-bred, spirited Kitty Charings is on the brink of inheriting a fortune from her eccentric guardian – provided that she marries one of his grand nephews.”

Nectar in a Sieve by Kamala Markandaya (1954). “This beautiful and eloquent story tells of a simple peasant woman in a primitive village in India whose whole life is a gallant and persistent battle to care for those she loves.”

The Talented Mr Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (1955). “Since his debut in 1955, Tom Ripley has evolved into the ultimate bad boy sociopath. Here, in this first Ripley novel, we are introduced to suave Tom Ripley, a young striver, newly arrived in the heady world of Manhattan.”

A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories by Flannery O’Connor (1955). “These stories show O’Connor’s unique, grotesque view of life— infused with religious symbolism, haunted by apocalyptic possibility, sustained by the tragic comedy of human behavior, confronted by the necessity of salvation.”

Collected Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1956). “Millay remains among the most celebrated poets of the early twentieth century for her uniquely lyrical explorations of love, individuality, and artistic expression.”

The Fountain Overflows by Rebecca West (1957). “An unvarnished but affectionate picture of an extraordinary family, in which a remarkable stylist and powerful intelligence surveys the elusive boundaries of childhood and adulthood, freedom and dependency, the ordinary and the occult.”

Angel by Elizabeth Taylor (1957). “In Angel’s imagination, she is the mistress of the house, a realm of lavish opulence, of evening gowns and peacocks. Then she begins to write popular novels, and this fantasy becomes her life.”

The King Must Die by Mary Renault (1958). “In this ambitious, ingenious narrative, celebrated historical novelist Mary Renault takes legendary hero Theseus and spins his myth into a fast-paced and exciting story.”

A Raisin the the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry (1959). “Set on Chicago’s South Side, the plot [of this play] revolves around the divergent dreams and conflicts within three generations of the Younger family.”

The Vet’s Daughter by Barbara Comyns (1959). “Harrowing and haunting, like an unexpected cross between Flannery O’Connor and Stephen King, The Vet’s Daughter is a story of outraged innocence that culminates in a scene of appalling triumph.”

The Colossus and Other Poems by Sylvia Plath (1960). “Graceful in their craftsmanship, wonderfully original in their imagery, and presenting layer after layer of meaning, the forty poems in The Colossus are early artifacts of genius that still possess the power to move, delight, and shock.”

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee (1960). “The unforgettable novel of a childhood in a sleepy Southern town and the crisis of conscience that rocked it, To Kill A Mockingbird became both an instant bestseller and a critical success when it was first published.”

The Householder by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (1960). “This witty and perceptive novel is about Prem, a young teacher in New Delhi who has just become a householder and is finding his responsibilities perplexing.”

The Ivy Tree by Mary Stewart (1961). “This remarkably atmospheric novel is one of bestselling-author Mary Stewart’s richest, most tantalizing, and most surprising efforts, proving her a rare master of the genre.”

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark (1961). Miss Jean Brodie “is passionate in the application of her unorthodox teaching methods, in her attraction to the married art master, Teddy Lloyd, in her affair with the bachelor music master, Gordon Lowther, and—most important—in her dedication to ‘her girls,’ the students she selects to be her crème de la crème.”

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson (1962). “Merricat Blackwood lives on the family estate with her sister Constance and her uncle Julian. Not long ago there were seven Blackwoods—until a fatal dose of arsenic found its way into the sugar bowl one terrible night.”

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle (1962). “Meg, Charles Wallace, and Calvin O’Keefe (athlete, student, and one of the most popular boys in high school)… are in search of Meg’s father, a scientist who disappeared while engaged in secret work for the government on the tesseract problem.”

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing (1962). “Doris Lessing’s best-known and most influential novel, The Golden Notebook retains its extraordinary power and relevance decades after its initial publication.”

The Group by Mary McCarthy (1963). “Written with a trenchant, sardonic edge, The Group is a dazzlingly outspoken novel and a captivating look at the social history of America between two world wars.”

Efuru by Flora Nwapa (1966). “The work, a rich exploration of Nigerian village life and values, offers a realistic picture of gender issues in a patriarchal society as well as the struggles of a nation exploited by colonialism.”

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys (1966). “Antoinette Cosway, a sensual and protected young woman … is sold into marriage to the prideful Mr. Rochester. Rhys portrays Cosway amidst a society so driven by hatred, so skewed in its sexual relations, that it can literally drive a woman out of her mind.”

#must-read#female authors#classic literature#literature written by women#literary classic#literary classics written by women

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

2018 Readlist

FAQ

Why do you read so many old books?

Because most of them belong to the public domain, and are thus freely available online. Also it is fun to see how much the past influences and creates the foundation for the present. And how much or how little has changed, and what this says about humanity.

Orwell - Animal Farm (1945)

A satire on the Russian Revolution and the failure of communism. Among other things, Animal Farm underlines the importance of learning to read properly and think for oneself, in a way that tickles with dark humor.

Orwell - 1984 (1949)

Similar to Animal Farm, 1984 is an even more systematic and total examination of a society where all history and information is tightly controlled and constantly being rewritten. Being published after WW2, 1984 trades some of Animal Farm’s humor for more serious and tragic imagery of concentration camps. In a sense, 1984 is an exploration of the possibility of mind control or brainwashing through societal-level propaganda.

Huxley - Brave New World (1932)