Text

#OnThisDayInGaming 🎂

Hexen for the N64 turns 24 today in North America!

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Welcome to the very first episode of the Ranger Report! As Your Gaming Dad, I think it's important to remember where you began, and with this review of Putrefaction 2: Void Walker, I didn't intend to start a brand new video series covering first person shooters, let alone open up the journey to Dadhood. But, rough as this might be, it's important to share our journeys, and to always be aware of how we started. This game is a lot of fun and I did enjoy making this video, so I hope you enjoy watching it!

#ruby ranger#ranger report#putrefaction 2#void walker#first person shooter#FPS#oleg kazakov#game review#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Review: THE WITCHER III: WILD HUNT (2015)

The Witcher III is too big.

There. I said it.

Imagine a huge meal. You’ve been thinking about it all day. Steak, baked potatoes, insert vegan options if you don’t eat meat, you know the drill. But you sit down and it’s glorious. Huge. Covers the whole table. A feast fit for a king. And now the insane task you find before yourself: eat the whole thing. No one’s gonna help you with it, it’s just you. A whole table’s worth of food. Eat all of it. That’s your task, eat all of it, or at least most of it, but don’t forget that if you get up from the table there’s still all of this delicious food just waiting for you to devour and going nowhere.

That’s playing The Witcher III.

You probably think I’m saying that in a negative way and that I don’t like the game, but I really do. I actually honestly do. I clocked in 95 hours on the main quest, side quests, and the first DLC Hearts of Stone. Before I played this one, I put in 48 hours on the first game and 35 hours on the second game. Bam, bam, bam, three games in a row, but somehow Wild Hunt is the one that felt the most of a slog. Even the first game, as tedious as it was, didn’t feel like it stretched on so long as Wild Hunt.

It has to be said that this game is a massive accomplishment for CD Projekt RED, or hell for ANY developer making a game of this type. Sheer density of worldbuilding and execution like this simply doesn’t exist in other games. Earlier this year I played Skyrim for the first time as well, and where that game felt like it was living, Wild Hunt felt like it was absolutely real. Ride in any direction and come across a village or a trader or a monster nest that somehow inevitably leads to the video game equivalent of a short story, multiply that by a hundred, populate the world with not one, not two, but three maps in-game, and pepper those alongside the main course which in itself is something like 50-70 hours, and you not only have a world that is easy to get lost in, but one that is difficult not to.

But where the first two games have a clarity of focus in their storytelling -- especially the second game Assassins of Kings -- Wild Hunt seems to wander back and forth between aggressive tension and meandering purpose; a game in which the primary staging is for Geralt of Rivia to go forth and find his surrogate daughter, Ciri, before the otherworldly Wild Hunt get to her and use her Elder Blood Powers to destroy the world, but stops to hunt monsters and help villagers and find treasure along the way. Open world games such as this have always been at odds with themselves when they attempt to tell a story in which the protagonist has a singular goal. Side quests and world traveling derail the intention of the plot. So, too, does Wild Hunt damage itself by providing such a brilliant, open world, one packed to the gills with things to do, and nearly require the player to go out and seek adventure just to level up enough to reach the level requirement for the next quest in the main storyline.

But that’s not to say that it isn’t enjoyable. Far from it: Wild Hunt has some of the most engaging, brilliantly written gaming I have ever experienced. It’s just that there is so much of it that I almost feel like I’ve gotten a little gaming PTSD as a result. Immediately after finishing the main quest, I uninstalled the game (ignoring the other DLC, Blood and Wine), installed Quake, and played through that in a couple days. I needed to run and gun. I needed a Boomer Shooter with focus. I needed to run from point A to point B. When I first started the game, I was in awe of the spectacle, of the scope, of the realization that this was the game that the devs had been wanting to make for years, but unable to because technology. And as I continued to gorge myself on the ever-expanding meal, realizing after a time just how much I was being told to consume, I began looking back at the lean, focused first two games, longing and yearning for their steady hand and dedication.

The Witcher III: Wild Hunt is a masterpiece. An achievement that few will ever come close to accomplishing, one that outshines Skyrim in nearly every aspect. But Skyrim does what Wild Hunt does not: it drops you into a world, free of charge, and says, “Go. Do whatever you want. You’re new here, and you owe no one anything.” Meanwhile, Wild Hunt says, “Look, your daughter is being chased by evil elves, your ex-girlfriend needs reconciliation, every single side character you’ve ever encountered in the other games (if they’re still alive) needs your help, and the emperor himself is watching over your shoulder. You also have monsters to hunt and treasure to find and people to help and witches to have sex with. There’s also exploration. Horse races. Fist fights. Gwent. There’s a lot. Make sure you stay on track. Your daughter needs you, like NOW. But do whatever you want.”

Eventually, scoring this game became difficult. What began as an easy ten out of ten began to sour over time, unto the point where I wanted to give it an even lower score for simply being TOO much. At what point to we reward developers for oversaturating their games to the degree of them being all-consuming? That being said, I still have to recognize the effort, the achievement, the technical accomplishment, in spite of the game itself being far, far too much for one game to ever be asked to be presented as.

Ironically, I committed myself at the beginning of the year to dive deep into the fantasy genre to test the waters and see if it was a genre I enjoyed or not. Skyrim was the game that convinced me that I did. Wild Hunt is the game that’s convinced me to take a break. Final score: 8/10

#the witcher 3#wild hunt#the witcher#assassins of kings#cd projekt red#geralt of rivia#ranger report#ruby ranger#ck burch#review

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theory: No One Is Real In Silent Hill 2

At last, for October, I present a Fan Theory nearly twenty years in the making. I’ve been thinking long and hard about this presentation, and for a moment nearly broke it up into a bunch of smaller posts. But where’s the fun in that? So below I present in its thirty-page entirety (I KNOW I’M SO SORRY) the idea that James Sunderland is the only physically “real” human in Silent Hill 2, and that everyone else is a manifestation created by the town. It’s a long, long, detailed long post, so if you’re here for it you have my thanks in advance. Go pee and get something to snack on.

Welcome to Silent Hill!

***

In the world of video games, true genre-defining experiences come few and far between. Often these benchmark releases inspire waves of imitators: some capture the spark of what made these masterpieces so memorable, most end up as cash grabs on a popular genre. Few games have inspired such imitation as the Silent Hill series. Provocative, psychological, and unafraid to tackle controversial content, the series is renowned for preying on player expectations, toying with perceptions of space and time and awareness. Many lesser games have made an attempt at reproducing the same magic, including later games in the same series.

Silent Hill 2 is singled out by fans and critics to be the best of the bunch. Hailed as one of the scariest games of all time, the story tackles the subjects of abuse (both emotional and physical), grief, and punishment. It does so in a very uniquely Silent Hill manner, in which nothing is real, and every step the player takes moves them closer to an abyss of terror. Developed by Team Silent, the group that created the first four titles in the series, Silent Hill 2 is categorized as a “survival horror” game, and the primary means of gameplay is that of tense combat with heavy emphasis on exploration and puzzle solving. Combat is by no means a “run and gun” escapade – the protagonist generally has a variety of melee weapons like a wood plank or a tire iron, and relatively few guns. Ammunition is sparse and requires constant management; the game recommends avoiding as many enemies as possible. Meanwhile, puzzles are mostly logic-based, involving riddles, the combining of objects to create a key, and choosing the proper item for the proper spot. The atmosphere is oppressively claustrophobic, even in its outdoor environments. Truly, this is an experience that is designed to make the player feel alone and isolated.

Despite this, Silent Hill 2 features a memorable cast; each character has distinct motivations and reasons for their journey to the town, but each person is also shrouded in mystery. After all, their purpose is not to tell their stories, but to enhance the journey of the protagonist. While at first it seems a given that these characters are all real – and they are presented as such – it is my belief that they are, in fact, manifestations of the town in order to provide extra torment for the protagonist, and also represent one of the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. This is a bit of a difficult pill to swallow at first glance, but the evidence is present throughout the game.

Before we dive into the reasons for this theory, let's first examine the story and setting of the game itself, in order to make sense of what is to come.

In my restless dreams, I see that town:

Silent Hill.

You promised you'd take me there again someday, but you never did.

Well, I'm alone there, now. In our “special place.”

Waiting for you.

-- Mary Shepard-Sunderland

In the opening of Silent Hill 2, James Sunderland reads these words, the beginning of a letter sent to him by his wife Mary. This is, of course, an impossible letter, as James quietly states that Mary has been dead for years, victim of a terminal illness. And yet, despite knowing this, James has come to the town of Silent Hill in order to understand how such an impossible letter could exist, and whether or not his late wife could truly be waiting for his arrival. For both the player and for James, this is an ominous way to begin the journey. Players familiar with the series will already know that the titular town conjures scenarios and creatures based on the psyche of the individuals in the town, making them see what it wants them to see. Those with, say, guilty consciences will see monsters and demons – innocents will only see an empty town. James, meanwhile, despite knowing full well that Mary is quite dead, is far too curious to understand what's going on here.

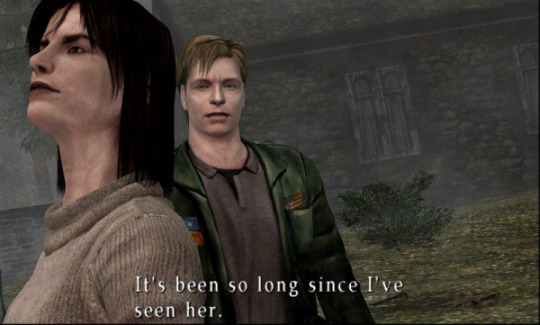

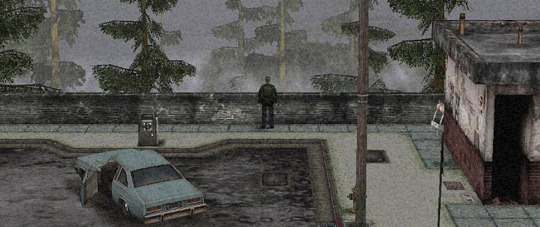

James begins his journey at a rest stop off the highway, above the town itself. This is the clearest view of the surroundings the game will give us until near the end. Forestry, tall trees, and waves of fog between them can be seen, with a large lake in the background beyond the town. Leaving the rest stop, James – and the player – is forced to walk a long path from the rest stop to the town, a full twenty minutes in-game. On all sides, the fog grows thicker, and the sounds of mysterious wildlife roaming the woods can be heard. As James enters the outskirts of Silent Hill, he cuts through a cemetery off the main road. Here he surprises Angela Orosco, who is sitting in front of a headstone, lost in thought. Immediately presented as anxious, cautious, stuttering and shy, Angela is a nineteen-year-old who claims to be searching for her mother – someone she accidentally refers to as “Mama” before correcting her choice of words to “Mother.” James tells her that he's looking for someone also, admitting that she may or may not be there. When he asks Angela if he's headed in the right direction of the town, Angela attempts to warn him off, saying that there's something wrong with the town, that he doesn't want to go there. James cuts her off, stating that he doesn't care if it's dangerous or not.

Returning to his quest, James finally enters Silent Hill. Here the fog is at its thickest, and the streets are clearly abandoned and in disrepair. James, thinking he sees someone walking through the fog in the distance, diverts course until he comes to a small construction site. A radio, blaring odd static, lies beside a dead body. James, cautiously, goes inside to pick it up, and turns around to face a strange, warped creature that looks like a shapeless human wrapped in a straitjacket made of flesh. In self-defense, James grabs a plank of wood and is forced to beat the creature to death. As he leaves, he thinks he hears Mary's voice coming from the radio, but the words can't be made out. He continues on. Now more of these creatures are walking along the streets, shuffling, shuddering, spewing acid from their gaping mouths if he gets too close. James can fight, or he can run, but out here where the enemies are multiple and fast, running is the best course of action.

James understands that his first objective is to reach Rosewater Park, where he and Mary shared an intimate moment during their vacation. But the streets have been cut off, so he decides to cut through the Wood Side Apartments. Inside it is dark, strange, and full of noises off-camera that exists solely to set James and the player on edge. In the apartment complex, he sees a key resting on the other side of some gated bars, which looks like it might be the one he needs to cross from one building to the next. As he attempts to reach through for it, an eight-year-old little girl appears out of nowhere. She kicks the key away and stomps on James's hand, laughing as she disappears into the darkness. This is the first living person James has seen in the town proper, and she has essentially made his life more difficult.

More creatures haunt the hallways of the apartment complex, including one that James sees standing on the opposite side of what look like prison bars in the middle of a hall. Tall, wearing a red triangular helmet and a flesh butcher's smock, this creature is called “Pyramid Head.” For now it merely stands opposite James, staring at him motionlessly. Later on, James will encounter Pyramid Head again, this time as it appears to be sexually assaulting another of the monsters. Hiding, James is forced to shoot at Pyramid Head with a gun he found in the apartments until it leaves on its own.

While searching through the apartment complex, James enters a room to discover Angela lying on the floor in front of a full-length mirror, holding a kitchen knife. As she gazes at the knife longingly, James tries to talk her out of whatever it is she's thinking of doing, stating that there's “always another way.” Angela's response is to compare the two of them, noting that it's easier to run away from their problems. She speaks in slow, exhausted tones, a stark difference from the stuttering hesitance of their earlier encounter. “Besides,” she concludes, still staring at the knife, “it's what we deserve.” James denies this, startled by the implication that he would consider such a way out. They continue to talk, James calmly and confidently holding Angela's attention, before they both admit to each other that neither of them have found the people they're looking for. James lets slip that he wouldn't be able to find his wife anyway since she's dead, which causes Angela to become nervous and animated again, and she gets up to leave. James says that they should go together since her warning about the town proved to be true, but she rejects the offer, claiming she'd only slow down his progress. James asks what she's going to do with the knife. Hesitating, Angela asks if James will hold on to it for her, that she's unsure what she'll do if she takes it with her. But when James reaches forward to accept the knife Angela screams and holds it out in defense. Surprised, James backs away as Angela has a near-breakdown, claiming that she's sorry and that she's “been bad.” She quickly sets down the knife and leaves the room in a flustered rush. James takes the knife, and it is worth noting that the knife cannot be used as a weapon in game, only as an item to be examined in his inventory.

James enters one of the apartments to discover Eddie, a portly twenty-something in an ill-fitting polo shirt and backwards cap, hunched over a toilet, violently throwing up. Eddie found a corpse inside of a fridge out in the living room after being chased in by some of the monsters, and a panicked Eddie became nauseous at the sight of it. In a difficult-to-stomach cutscene, Eddie continues to vomit while James talks to him. Eddie adamantly proclaims his innocence in regards to the dead body, claiming that he “didn't do it” and that he's not from Silent Hill. James, oddly, continues to converse with Eddie calmly, as though he's ignoring the man's explosive vomit. He asks if Eddie knows Pyramid Head. Confused, Eddie says he doesn't know what that is, only that he's seen some monsters that have freaked him out thus far. James infers that something brought Eddie to Silent Hill, but that whatever it is, he should try to leave town as soon as possible. Both men tell each other to be careful before James leaves Eddie to finish his business.

After several puzzles and strange occurrences, James is confronted by Pyramid Head, who is now wielding a huge knife that it has to drag behind it. Forced into a narrow room, the player must guide James back and forth, avoiding Pyramid Head's slow attacks, while shooting round after precious round into the beast. Eventually, an air raid siren can be heard in the distance; Pyramid Head descends a set of stairs that are submerged underwater, leaving James to his fate. The water drains, James follows – and the monster is gone.

Leaving the apartments, James finds the little girl who kicked him in an alley out back, perched on a high wall. Her name is Laura. She's precocious, bratty, and stubborn. James tries to get her to come with him, since there are monsters running around that could hurt her, but it seems as though Laura doesn't see the monsters. During their chat, she tells James that he “didn't love Mary,” and refuses to answer any other questions before running away into the fog.

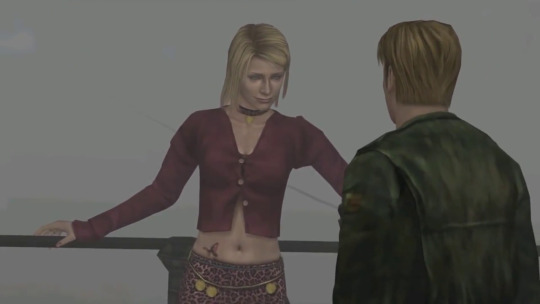

As very confused James continues through Silent Hill, he arrives at Rosewater Park, hoping that this is where he will find Mary. But instead, James finds Maria, a woman who resembles Mary so much that he notes that she could be her twin. Yet Maria quickly establishes her stark difference from Mary. First, with her clothing: where the game shows images of Mary wearing a conservative pink cardigan and long skirt, Maria wears a revealing purple top and leopard print miniskirt. Her walk is sultry, her demeanor flirtatious, and her gaze holds a mischievous “come hither” look. Even her hair shows the change: where Mary had a darker auburn hue, Maria clearly has bleached hair, her brown roots prominent, a tint of red at the tips. James, taken aback by how different this woman is from his wife, at first decides to leave her be. But Maria quickly requests to come along with, wondering aloud if he was going to just leave her alone in a town surrounded by monsters. Guiltily, James tries to avoid this, but surrenders to letting her tag along. She asks if there's another place that Mary could be, and he realizes that they had stayed at the Lakeview Hotel, on an island in the middle of Toluca Lake. Together, the two of them set off to find a way there.

As the player guides James through the town, Maria follows at a decently close pace. Not quite as fast as James, but not so slow that she can't keep up. The artificial intelligence designed for Maria allows the player to not worry if Maria is nearby or not when running from or fighting monsters. In other games, the mechanics would force the player to worry about their companions, but not so Maria; she always catches up, and no matter how far away she is when James goes through a door into a new environment, Maria is immediately waiting on the other side. This ties in to the theme of Maria needing James to take care of her in the story.

Discovering that the highway leading out of town towards the docks has sunken into the earth, James turns around to seek out alternate means of getting to the hotel. Searching through the town, he comes across the Bowl-O-Rama, and decides to go inside just in case he can find any supplies worth taking along. Maria, notably, refuses to go with, stating that she hates bowling and would prefer to remain outside for him.

Inside, James hears two voices talking to each other: Laura, and Eddie. The scene cuts away from James, and focuses instead on these two characters. This is significant in that this is the only time in the game where two people who are not James are having a conversation, and their topic is significant. Laura mocks Eddie's weight, calling him a “gutless fatso,” and asks why he's running away from the police, why he can't just apologize for what he's done. Somehow he's gotten hold of some pizza, which he gladly eats while Laura sits beside him. Eddie states that he would never be forgiven for his transgressions, and continues eating. Laura mocks him for being a coward. Again, this is tellingly the only conversation in the game that James is not a part of, nor does it exist for his benefit in the game. It's only for the player to see and understand.

After this cutscene, James enters the bowling alley and finds Eddie. He asks Eddie if he's alone, which Eddie cautiously admits that he isn't. Laura rolls a bowling ball their way to get their attention, which causes James to see her briefly as she leaves the building. James tries to get Eddie to follow, but he declines, stating that Laura already said she was fine on her own, and that she claimed “a fatso like me would only slow her down.” James, in disgust, says, “Forget you!” before chasing after Laura. Outside, Maria tells James that she saw Laura headed towards the hospital, and they shouldn't leave her alone with the town being the way it is.

James follows Laura to Brookhaven Hospital at Maria's behest, and after Maria stops to rest in one of the rooms he goes on alone. Maria, it should be noted, has claimed to be hungover, but has developed a nasty cough and is taking pills from a prescription bottle. James, pressing on, eventually discovers the little girl playing with teddy bears. Laura is at first shocked to see James, but he assures her he is friendly and isn't going to hurt her or be angry. He just wants to know how she knows Mary. Laura, it turns out, shared a hospital room and nurse with Mary – only the week before. Hearing this, James shouts that Laura is a liar, which she brusquely receives, but she claims that there's something for James from Mary in the hospital and leads him to another room. Once inside, James finds himself locked in with a group of monsters hanging from the ceiling, tricked by Laura. James is knocked unconscious and awakens in an alternate form of the hospital to find Maria.

Maria is less than pleased that he left her alone, demanding comfort as she runs into his arms. But their reunion is short lived: as they attempt to flee the hospital, Pyramid Head appears and pursues them down a narrow corridor that leads to an elevator. James makes it, but the doors shut before Maria can get inside too. She is able to reach her arm in and flails for help as Pyramid Head stabs her to death. Grief stricken at watching Maria die, the woman who looks exactly like his late wife, James sees Laura running away through the front window, he decides to push himself onward. It's telling that as he exits the hospital, the town has changed from day to night, enveloped now in darkness as well as fog. After leaving the hospital, James attempts to find a way to cross Toluca Lake to get to Lakeview Hotel on a nearby island and find the last potential “special place.” In doing so, he discovers a hidden entrance to a strange underground prison beneath the Silent Hill Historical Society. Before this, however, James finds a painting in the historical society of an executioner surrounded by bodies in cages – the executioner looks exactly like Pyramid Head.

After a terrifying descent through impossible spaces – vertical hallways, vast drops into abyss-like blackness – James emerges into the underground prison. Eddie, somehow, is there as well. However, his aloof demeanor has been replaced with a chilling lack of empathy. Sitting on the ground brandishing a revolver, Eddie flinches as James shines his flashlight on him. He proceeds to smile vacantly, stating, “Killing a person ain't no big deal. Just put the gun to their head – pow!” He mimes shooting himself in the head as he does this. Lying on the table beside Eddie is a dead body with a head wound; Eddie claims it wasn't his fault, that the person was looking at him funny. James tries to rationalize with Eddie, telling him he can't just kill someone because of how they look at him. Visibly confused, Eddie asks why not, before continuing to reminisce about a “stupid dog” who'd also had it coming. After this, Eddie chuckles nervously, claiming everything he said was all just a joke, and that he needs to get going. As Eddie opens a door to go deeper into the prison, James asks, “You're going out there alone?” Eddie replies enthusiastically, “Yeah.”

Questing through the prison, James is shocked to discover Maria sitting on a chair inside one of the cells. Confused, James tries to speak to her, but her demeanor is odd: she talks about things that only Mary would know, including a videotape the two of them made together while at Lakeview Hotel. Stunned, James asks if she's actually Maria, to which she brusquely responds, “I'm not your Mary.” She implies a sexual reward if James finds a way around to unlock the cell, but by the time he discovers this path, Maria's body is on the cell's bed, bloodied, dead once again. Struggling with this, James forces himself to move on.

Angela appears in the prison labyrinth as well. Walking through a hallway, James finds scattered newspapers all over the ground, and if examined, reveal a news story about a lumberjack named Thomas Orosco, found with his throat slit in his own house. Moving onward, James hears Angela's voice scream: “Daddy! Please! No!” Rushing through a nearby doorway, James comes across a terrifying sight. Before him is a room made of fleshy material, with a television and makeshift furniture. Lining the walls are mechanical pistons which pump constantly and out of sync with each other. Angela is on her back, desperately trying to get away from a monster. Unlike anything else seen up until now, the monster resembles a person lying on top of another person in a bed, covered by a topsheet of flesh, and a twisted mouth emerging from the front. It shuffles forward on two legs with insidious humping movement. According to the game, this monster is called the “Abstract Daddy.”

James protects Angela and kills the monster; once this is done, Angela leaps to her feet, kicking the creature over and over before picking up the television and crashing it down on the Abstract Daddy, finishing it off. James tells her she can relax, but she screams at him, telling him not to tell her what to do. She accuses him of only wanting “one thing,” and that if he does, he should just force her and beat her, “like he used to do.” As she says this last part, she points at the dead Abstract Daddy, and breaks down, crying and dry heaving. When James tries to comfort her, she pushes him away, saying he makes her sick. She calls him a liar for claiming that Mary died from her illness. Departing with a sneer, she implies that James probably wanted to be with someone else.

Eddie's final appearance comes just before the end of the prison. James enters a cold storage room to discover Eddie standing over yet another dead body, but his mood here has deepened into something far more morose and morbid. James asks if Eddie killed this man as well; Eddie starts to shout about how it was deserved, how the man always called him a fat piece of shit, among other instances of verbal abuse. “It doesn't matter whether you're smart, dumb, ugly, pretty, it's all the same once you're dead!” Eddie shouts, concluding that “a corpse can't laugh.” James asks if Eddie has gone nuts; Eddie decides that James is just like everyone else, laughing at him behind his back, and points his gun at James. The player takes over, forced to fight Eddie, and after a few minutes of action Eddie retreats deeper into the meat locker.

The next room where Eddie has retreated is dark, foggy with cold air, and full of large meat slabs hanging from the ceiling. The meats are all wearing pants with suspenders. James proceeds cautiously as Eddie taunts him from the shadows. Eddie asks James if he understands how it feels to be made fun of just for how he looks. Eddie continues, ranting about how he'd shot a dog because it taunted him, before shooting the owner – his personal bully – in the knee. He laughs about how difficult it would be for the man to play football after that. James tries to tell Eddie that he needs help if he thinks it's okay to kill people, to which Eddie scoffs, telling James that the two of them are the same. After all, he says, Silent Hill called to James as well.

Eddie pops out of the shadows, and the player takes over for another battle. This time, once enough hits are landed, James kills Eddie. Once Eddie has fallen, James rushes over to his dead body, and shows remorse, shameful that he's killed a human being. From here, James leaves the prison and finds a dock with a rowboat waiting outside. He uses it to cross Toluca Lake and get to the hotel.

Startled in the hotel lobby by a loud noise, James finds Laura at a grand piano, having just struck a loud chord to get James's attention. Here they finally have a conversation about their purpose: Laura is here to try and find Mary based on a letter that Mary left for the girl, in which Mary says she's sorry for leaving and is in a beautiful place now. Mistaking this to mean she is in Silent Hill, Laura has come here to find Mary. Also of note in the letter is that Mary tells Laura not to hate James for being “surly” and for not visiting the hospital much, claiming that James is very sweet deep down. Mary specifically says that she had hoped to adopt Laura. James, learning Laura's age and recent interaction with Mary, is forced to admit that Mary couldn't have been dead for three years, and in fact may still be alive.

Upstairs however, James discovers the room he and Mary shared, as well as their videotape. It's a home video of a sickly Mary saying how much she loves Silent Hill before succumbing to a coughing fit. The image changes to one of Mary lying in bed; James leans over her, kisses her forehead, and then smothers her to death. It's this point in the game where both James and the player are confronted with the truth. All around the hotel there have been various video and audio cues that imply the nature of James and Mary's relationship during her final days: a tense, abusive atmosphere in which Mary constantly lashed out at James in anger due to her own negative self-worth, only to adopt a pleading, loving tone after fighting. James, bitter from years of slow decay and sexual frustration, opted to end Mary's pain. Was it a selfish act, or an altruistic one? The story leaves that to the player to decide. James is shown to be in torment over his actions, the memory of which he either repressed on his own or was altered by the powers of the town.

Contemplating the truth of his repressed memories after viewing it, James is found by Laura. He confesses his actions to the girl. Laura screams at James that she hates him, wanting to know why he did it, demanding James bring Mary back, telling James he never really did care about Mary. Filled with sorrow, James can only tell Laura that he's sorry, and that the Mary she's looking for isn't here. Laura leaves without another word. James is spurred on to keep searching for Mary when he hears her voice come from the final, static-filled moments of the video tape, calling for him, saying she's waiting.

Angela's final appearance is in the Lakeview Hotel. James enters a hallway that is engulfed in flames – something odd as the previous area had not been. Angela is here, standing at the bottom of a staircase, staring up into the fire that is consuming the hotel above her. At first she confuses James for her mother, and Angela is excited to see him before realizing that who she's seeing isn't real. She apologizes and thanks him for saving her before, but wishes that he hadn't actually done so. She says that her mother had told her once that she deserved the things that had been done to her, and when James refutes that, Angela simply asks for him not to pity her. After all, she says, what is he going to do? Love her? Take care of her? James doesn't answer. “That's what I thought,” Angela replies. She then holds out her hand and demands her knife back. James, showing genuine care for her, says he won't. She accuses him of holding onto it so he can use it, but James states that he would never kill himself. Hanging her head in sadness, Angela turns and begins to walk up the staircase, fire burning up part of the stairs behind her, effectively cutting off James from following. “It's hot as hell in here,” James muses. Angela's final words are, “You see it, too? For me, it's always like this.” Then she turns and ascends into the inferno.

Leaving the hotel, James finds a room with not one, but two Pyramid Heads, each holding a long spear. Maria is suspended upside-down on a rack, begging for James to help her, but the Pyramid Heads execute her in front of him. Up til now, James has slowly found more and more evidence of the town having supernatural properties, of the myths and legends surrounding it. Realizing that his entire journey has been placed before him by the town, he admits to his need for punishment and faces down the Pyramid Heads. Knowing that their purpose is complete, both Pyramid Heads execute themselves. James then climbs to the top of the hotel to discover one of two outcomes: Mary or Maria, waiting for his arrival. And, depending on his actions during the game, his ultimate fate.

This is an exploration of the psyche unlike any in gaming. Each place he visits holds clues to what is happening both to the town and to his fragile psyche, in the form of strange creatures and the humans he meets. At the end of his quest, James discovers that he has been searching for punishment for his actions this entire time, which has been granted by the strange power of the town itself. Established in the previous game, the town of Silent Hill has the ability to warp reality around those who are drawn towards it, people who are usually tormented by something horrific in their past. How this can be so is never really explained, only hinted at, particularly with the information that the land used to be a sacred place to native tribes that used to inhabit it. Previously, it had manifested a scenario based on the pain and suffering of a powerful psychic girl who been horribly burned as part of a ritual of the town cult. In this scenario, the Silent Hill has taken James's need for punishment and provided it tenfold, but because James is unsure of exactly what he feels he deserves, it also provides multiple angles with which to torture him. Even the outcome of the game itself is open-ended; based on the player's actions during the story, one of four endings will commence with a finale befitting James's decisions. None of the endings are considered the “true” ending by the developers, leaving players to define for themselves what should – or should not – happen to James. These decisions are based solely on items and characters James interacts with. Each decision is subtle, never overt, and first playthroughs often end with James leaving the town in peace. But each finale is very specific, and I believe is represented by each of the four characters James meets in the town.

MARIA

If, during the course of the game, the player has James spent significant time with Maria – including returning to the rooms she's either sleeping in or being held in to check on her – and if the player is careful to ensure Maria takes no damage from the monsters of the town, James will get the “Maria” ending, which is one of two endings that directly relate to one of the other characters.

This is the only ending in which James actually finds Mary at the top of the hotel. Realizing that he'd rather be with Maria now, he confronts Mary. Angered that he's choosing a lesser woman, Mary transforms into a monster, forcing James to kill her in response. After he does, he returns to Rosewater Park where he first met Maria, to embrace her once more and leave town together. As they walk back to James's car, the rest of Mary's letter is read aloud: Mary details her sadness at her stay in hospice care, her sorrow for being so terrible and mean towards James, and assuring him that their relationship was something she'd cherished over the years. She assures James that he had made her happy, and for James to live for himself and do what he needs to do to live.

After the letter is read, James and Maria arrive at his car. She begins to cough, much in the same way the player has seen Mary coughing in flashbacks. Ominously, James has this to say: “You'd better get that looked at.”

Through the events of the game, it is heavily implied that Maria is a construct of the town's powers, an idealized version of what James had wished Mary had been. Despite sensing this, James still chooses her in this ending. After his initial quest to find Mary, James, it seems, did not hold enough devotion to his late wife to see it through to the end. Knowing now that she's dead and gone and that nothing can bring her back, he has resorted to bargaining. He spent so long during Mary's sickness frustrated at being unable to have his life, that with the attractive option of Maria he has once again taken an easier way out – a way that he feels he deserves to have. “What if,” he must think, “I can have the Mary I always wanted without having to deal with Mary's death?” Yet, with the final moments foreshadowing a similar fate for Maria as Mary had, it seems as though the town is not as merciful as it might appear.

What further fleshes out this idea is a bonus chapter for the game that initially only came with the XBOX version before being added to the PlayStation rerelease. Titled “Born From A Wish,” the player assumes the role of Maria before she meets up with James at Rosewater Park. During the short chapter, Maria comes to understand that she was created for a single purpose: to try and entice James into being with her. She wrestles with this notion, even going so far as to put a gun to her head as her only option of getting out. After all, what if he rejects her? Will she be forced to stay in this town forever if that's the case? Finally, Maria accepts her fate and her purpose, and she begins her walk towards the park to meet James.

With the confirmation that Maria was manifested by the town in accordance with James's unconscious desires – even going so far as to reveal that Maria's look was based on a dancer at the local club Heaven's Night – this now opens the door to the possibility that the other characters in the game have also been manifested by the town to aid in James's torment. What's different about Maria is that it is explicitly stated in the game that she was created by the town, where it is naturally assumed by the player that the other characters are in fact real, and have been called to the town for various reasons.

Now that we have some details of the plot and the understanding of how these manifestations work out of the way, let's focus on the individual details of the other characters in the game.

LAURA

In many ways, Laura is a metaphorical hook on the town's fishing pole, bating James into going deeper into the town to discover the truth behind Mary's letter.

After viewing the videotape in the hotel, Laura is not seen again unless the player achieves the “Leave” ending. There are a few key actions one must take in order to get this. First, the player must examine the letter from Mary that James has been carrying since the beginning of the game. This item stays in James's inventory during the whole game, and can be examined multiple times, as it should be to ensure this ending. It's worth noting the fact that, late in the game, examining the note again reveals a blank piece of paper; there never was a letter written by Mary asking James to come to Silent Hill. He made it up in his head. Or, perhaps it was the town's influence.

James must also keep his health meter high throughout the course of the game, consuming items to keep his health from going too low, demonstrating a desire to live. Also necessary for this ending is listening to a lengthy conversation between Mary and James – a memory – that plays as James walks through a long hallway towards the rooftop. It's mostly dialogue from Mary; she is heard yelling at James for bringing her flowers, claiming to be disgusting after the effects of the disease and the medication keeping her alive, shouting at him to go away, that it would be better for her if the doctors just killed her. Then, the turn: crying, Mary begs James to stay with her instead, to tell her that everything will be okay. The player can ignore this conversation if they run quickly through the hall before the dialogue is finished, but in order to get the “Leave” ending, they need to listen to the whole audio. After fulfilling these tasks, James has demonstrated his devotion to Mary and his remorse for killing her.

When he reaches the hotel rooftop, he discovers Maria dressed as Mary, and he confronts her, telling her he doesn't need her anymore. She transforms into a monster and James is forced to kill her. In the cinematic that follows, James finds himself in Mary's sick room. Mary tells him that she wanted the pain to end and James tells her that's why he killed her, to take away her suffering. But, he continues, he admits that she'd said she didn't want to die, and that his actions were selfish. Mary sees the sadness in his face, and tells him to move on with his life, to live and to be happy.

Mary's letter is read aloud again, this time over a shot of the cemetery outside Silent Hill. It should be noted that the same letter is read aloud over each of the endings, taking on a different meaning with each scenario. As the reading ends, we see Laura walk confidently through the cemetery, following by James, and together they walk into the distance until they are swallowed by the fog.

“Leave” is considered by many to be the closest to a definitive ending for the game. James has faced his actions, committed to atoning for his sins, and finds redemption in the innocent girl who also came to find Mary. Since they are leaving together, it's reasonable to assume that James intends to adopt Laura in the same way that Mary had intended to. Or had she? Considering the manifestations of the town, and the fact that Mary's “letter” turns out to be blank by the end of the game, it's very possible that Laura's letter was also blank, something for James to see what he – or maybe the town – wanted. Laura represents moving on, similarly to how Maria did. But with Laura, James sees a piece of his late wife in the little girl, the daughter that they'd never gotten the chance to have together. According to the developers, Laura is a real person who came to the town, hinting that she'd hitched a ride with Eddie. The official novelization of the game follows Laura for a brief segment, seeing the town through her eyes. But this shouldn't stop us from considering that Laura is a manifestation of the town. After all, Maria told James multiple times that she was “real” and had a personality and memories of her own. Laura is also presented as an eight-year-old girl who somehow left the hospital she was staying in and found her way to this abandoned town, and is running around happy-go-lucky without a care. Even if we accept that Eddie gave her a ride into town, it still doesn't explain how a child so young could possibly have reached this place by herself without any other means. And let us consider Laura's role, drawing James deeper and deeper into the town to uncover the truth of his sins. Where Maria is happy to distract James and take him away from Mary, Laura's actions throughout the story are the catalyst for him to continue. She kicks the key out of his reach at the apartments, forcing him to find a new way around and encounter Pyramid Head. When she leaves both the bowling alley and the hospital, James follows her. Inside the hospital, it is here where James is first forced to consider that perhaps Mary hasn't been dead for as long as he thought, and after this Laura locks him in a room with monsters that forces him again to confront Pyramid Head. This is culminates at the hotel, where her words push James towards the truth, and her letter implies that Mary would have wanted to adopt this young girl. Finally, she judges him after viewing the tape, saying she hates him, and that he never loved Mary. She wants Mary back, and if James finds the “Leave” ending, it turns out that he does, too – but he can't have her. Here is where he must find acceptance. This spark of redemption, this eight year old girl, will have to suffice. Except she is just as false as the rest of the manifestations of the town, a fake promise of hope and happiness. James might believe he has found redemption, but at what cost? Notably, in the ending cutscene, Laura is the one leading James as they leave the town, as she has been leading him the entire game.

ANGELA

Utilizing symbolism and a “show don't tell” quality, this next story is one that the game trusts the audience to infer, but with enough detail as to make what is unsaid unmistakable. So, in order to understand the true meaning behind the “In Water” ending, we look to examine the story and interactions with the first character James meets on his journey: Angela Orosco.

Angela's knife is a key item for receiving the “In Water” ending of the game. James must examine the knife in his inventory at least once in order to trigger the potential of the ending, more times to ensure it. James must also let his health meter run into the red, staying at a fairly consistent – and dangerous – level close to death. This shows James's lack of care whether he's alive or not, which falls in line with the suicidal implications of Angela's knife. Maintaining a good distance from Maria and listening to the audio cues from Mary in the hotel are important. There is also a diary on the roof of Brookhaven Hospital, detailing the suicidal thoughts of a former patient there, that must be read. If these conditions are met, “In Water” will happen.

On the hotel rooftop, James discovers Maria dressed as Mary. Just like with “Leave,” he tells Maria that he's done with her, causing her to transform into a monster and he kills her. Once this happens, James finds himself next to Mary's sick bed, just as with “Leave.” But the dialogue here is different: James again admits that he didn't kill Mary to only ease suffering but to get his life back, however this time Mary doesn't bother pointing out James's sadness. Instead, she simply tells him that he killed her and now he's suffering for it, and that's enough. Mary begins to violently cough before dying once more, and a grieving James picks her body up off of the bed and walks off with her.

The screen turns black. We can hear the sound of footsteps, and a car door open and shut. James speaks aloud, a monologue, saying that he finally understands why he came to this town, wondering why he was so afraid to face it. In the background, the engine kicks over, revving to high speed. James admits that without Mary, he has nothing. The car is heard speeding down the road, growing louder and louder with intensity – before it abruptly cuts to silence. “Mary,” James says, “now we can be together.”

Mary's letter is once more read aloud, but this time over an underwater scene. Light from the surface can be seen, air bubbles rise past. It appears as though James has taken Mary's body back to his car and driven into the lake. There is no sight of him leaving, no further words from him, only the somber silence of the water and implication that James, after all of his confidence that he would never kill himself, has finally gone and done just that. It is one of the darkest and most melancholy endings to a video game ever written.

Now, we must examine the ties that Angela has to “In Water,” and what presents the notion that she is a fictional manifestation of the town rather than a real person. Firstly, it should go without saying that the theme of suicide is the most obvious tie. Angela wants to kill herself rather than face the trauma of her past, and so too does James. One of the implications hammered home over and over is that Mary was verbally abusive towards James near the end of her illness, something she addresses in her letter at the end of the game. She understands what she has done to him, and that he may hate her for it. James, for his part, admits that part of him killed her because he hated her, because he wanted his life back. Angela, too, did the same thing, only for her it was an act of survival. We can easily come to the conclusion that her father was physically and sexually abusing her based on the creature design and Angela's words. The sexual nature of the room where James fights the Abstract Daddy – with the pistons pumping in and out of the fleshy walls – brings this to a head. Killing her father, much like James killing his wife, caused a break in her. Wandering through Silent Hill to find her “Mama,” a source of matronly solace, is the opposite of James searching for his own wife, a woman who never had the chance to be a mother.

Reflections and opposites are what define the relationship between James and Angela, and I believe seals the notion that she is a manifestation. James has blonde hair, Angela has dark brown; James wears a dark grey polo under a green jacket with blue jeans, Angela wears a light grey turtleneck and red pants. When James and Angela meet in the apartments, most of their conversation takes place in a reflection. As she lies on the floor in front of a full length mirror, the camera primarily focuses on her, with James captured in the reflection. One shot in particular is telling: the camera looks down from the ceiling, Angela on the right, her reflection on the left, taking up equal sides of the screen, as she gets up off of the floor to turn to James. Before this scene, it's worth noting that Pyramid Head, James's own personal punisher, had been seen carrying no weapons whatsoever. But after Angela hands over the knife to James, when we next see Pyramid Head it is possessing a blade so large it has to drag the knife behind it. It's even referred to as the “Great Knife.” Angela provided James with more fuel for his own punishment, just as Laura led him closer to the hidden truth, just as Maria tried to pull him away from it.

For most of the game, James sees the town as water damaged from the fog. He sees wet environments, dripping water. The theme of water is present throughout the course of the game, except for one glaring instance: Angela's hallway of fire. For her, the world is always aflame, burning, the heat of her trauma a constant reminder. James, on the other hand, is always surrounded by water and drowning. At the end of their stories, when each of them decide to commit suicide, Angela does so by walking upwards into the flames, and James goes downward into the water. James has spent most of the game staunchly denying any desire or ability to commit suicide, but Angela has always known; in fact, she's embraced it. They are opposites in every capacity, down to gender identity, which is particularly of note in that Angela is the only female identifying member of the cast who has no relation to Mary. When we first meet James, he is introduced to us staring at his reflection in a dirty bathroom mirror. And when James and Angela first meet? She attempts to warn him away, to not go into the town, but James's reaction is exactly the opposite. He's going to the town to find what he wants, danger or no. Somewhere, a part of him was trying to get him to turn around, to run away, and that piece manifested in Angela's words.

It should also be noted that the game's creators have confirmed that from the opening of the game Mary's body is in the back seat of James's car. Her death is incredibly recent, within the last couple of days or hours. Perhaps James brought her here with the intention of committing suicide the entire time, having succumbed to the trauma of killing her, to the intense feeling of depression that he now carries.

But even if the previous evidence of opposites and reflections in the two characters has not been enough to convince you of their relation to each other, consider this: each of the first three Silent Hill games features a portrait of the main character on the front box art. Silent Hill 2?

The face on the cover is Angela's.

EDDIE

Up until this point it has been a relatively easy task to link the previous three characters to the endings of Silent Hill 2. Showing the relation of Eddie Dombrowski to the hidden “Rebirth” ending is a little more difficult considering both his story and the events necessary to unlock this ending. And yet, there is enough compelling evidence to demonstrate how this seemingly buffoonish man is essential to understanding the final ending to Silent Hill 2.

What's interesting about Eddie's story is how similarly it follows James's. While Mary did not bully James over his looks, she did verbally abuse him over a long period of time before he finally gave into his torment and killed her. So, too, did Eddie spend years being tortured verbally by those around him, the football player in particular, just because of his weight. Over a period of time, this harsh treatment turned the mild boy into a violent man, finally giving in to his urges and killing the bully's dog before shooting the bully in the knee. This is the event that Eddie was referring to in his conversation with Laura, saying that no one would ever forgive him for what he'd done; James no doubt felt much the same way after killing Mary. James laments his actions, aghast that he has killed a person. It turns out that Eddie is not his first murder, nor is it the only one done in “self-defense.” After all, with years of abuse stacked up, James wanted his life back and to not feel hurt anymore. In self-defense of his own emotions and life, he killed Mary, convincing himself that it was to end her pain as well.

But, unlike the other three characters we've examined, James's interactions with Eddie do not directly lead to one of the game's four endings. “Rebirth” is not an ending one can even achieve on the first playthrough of the game – it is only on starting up a new game after completing the story once can the player discover the necessary items to unlock “Rebirth.” There are four: the White Crism, the Obsidian Goblet, the Book of Lost Memories, and the Book of the Crimson Ceremony. Each of these items are found in locations scattered across Silent Hill, and without all four the Rebirth ending will not occur. If all of them are in James's possession, it will not matter what he did during the course of the game, or what ending was being led up to. “Rebirth” will take over, assuming James has been pursuing this course of action all along. As usual, James will find himself on the rooftop of the hotel, confront Maria disguised as Mary, battle her, and kill her. But then the player is treated to something unusual out of these endings: there is no scene of reconciliation with Mary on her deathbed, and Mary's letter is not read aloud. Instead, once Maria has been killed, the game fades in to James rowing his boat across Toluca Lake through the fog, with what appears to be a body in the boat with him. James narrates over the visual:

Mary. Forgive me for waking you. But without you, I just can't go on.

I can't live without you, Mary.

This town, Silent Hill...

The Old Gods haven't left this place...

And they still grant power to those who venerate them...

Power to defy even death...

As James speaks, the camera slowly pulls up and away from the row boat, which becomes more and more difficult to see in the swirling mist. But as it does, it reveals that James is rowing towards a previously unknown island in the lake. It is small, covered in trees, and has a dock for tying a boat to. As James approaches, he sighs, “Ah, Mary...” before disappearing behind the island, out of view of the player, the island the last thing we see before the credits roll.

What's chilling about this ending are the implications it delivers. First, is that the powers of the town are not simply metaphoric or metaphysical, but extend beyond the veil of the natural world. The first Silent Hill dealt with the cult who lived in the town, and their obsession with the Old Gods, but Silent Hill 2 chooses to focus more on the psychological horror of the town and the effects on the mind. While each of the monsters in the second game have horrific visuals, they can all be traced back to the trauma impacting James from his time during Mary's last days. Even Pyramid Head is explained through a painting found in the Historical Society of an executioner that bears the creature's image. But here, with this ending, Silent Hill 2 at last announces the connection to the first game in the sense of the Old Gods and the dark forces that inhabit the town. James is now crossing those lines, once a victim of them in his mind, now rising to the understanding of how to manipulate those powers to his benefit...if he venerates the Old Gods.

Secondly, this ending implies that James has been on this journey more than once. We can infer this from the simple fact that the ending can only be unlocked after any one of the previous endings have been seen. There's also the disturbing evidence left behind in the shape of the various bodies James finds along his journey. Both in the streets of Silent Hill and in the apartment complex, James finds bodies that wear clothing eerily similar to his own: black shoes, blue jeans, green jacket. Only the faces are bloodied and torn apart as to be unrecognizable. We could, of course, posit that this is just the town's way of predicting James's fate in the same way that interacting with Angela does. In fact, there are multiple ways in which the town predicts James's demise. One of them is found inside Neely's Bar (or, as it's listed in the game, Bar Neely's). A message written in what looks like blood reads “There was a HOLE here. It's gone now.” Later, when James returns to the bar after leaving the hospital, the message has changed: “If you really want to see Mary, you should just DIE. But you might be heading to a different place than Mary, James.” In multiple, subtle ways, the town is directing James towards one of multiple conclusions. It creates Maria, and pushes her in front of him as a means to have back a form of the woman he's lost. It creates Laura, who would have been Mary's adopted child with blessing, and with whom Mary implies she wants James to find reason to move on. It creates Angela, whose state of mind reflects his torment, who James sees is slowly preparing to die, and takes inspiration from. But it also creates Eddie, and Eddie's answer denies all three other routes. Once Eddie's method is chosen – the route which leads to a resurrection – then the story still unfolds, but refuses any other conclusion. Because the women in the game are there to add to James's torment, to force him to face his past and come to the conclusion of how best his punishment must be meted out. But Eddie, the only other male identifying presence in the game, represents what James has been doing before the events of the game: denial.

Eddie changes his story about his past multiple times. When we first meet him, he's vomiting, cowering, appears weak and harmless and denies doing any harm to the body in the next room. Next, he's having a pity party while confessing to Laura, however slightly, that he would be unwelcome by others after what he'd done. Again, remember that this is the only conversation in the game that doesn't involve James – Laura, the icon of moving on despite the past, and Eddie, the icon of denial. Eddie's denial deepens in the prison, when he claims that “killing a person ain't no big deal,” but then jokingly assures James that he was just kidding about causing violence. But his denial only goes so far: in our final meeting, Eddie has accepted the violence he's caused, but focuses the blame on those around him who made fun of him, who “had it coming, too.” Eddie has been hurt, his anger is justifiable, but his means cannot be so. It is extremely telling that the slabs of meat hanging from their hooks are all wearing pants and suspenders. Eddie has been pushed psychologically to the point where he sees the people around him as little more than meat. He understands what other humans are capable of, and has reached the point where he refuses to sit back and take it anymore. His gun, an oversized revolver, is symbolic of his power. James, too, has been pushed to the point of retaliation, but he still denies himself the truth, just like Eddie in the beginning. James is constantly pushed further and further into the realization that he has killed Mary, that he has done wrong, and that he must come to terms with it. In three endings, he faces this wrong. In the final ending, he simply denies the wrongdoing. He's been through this before, he's justified himself, he searched through his mind and come to the conclusion that he was justified in his actions. But how can that be? Well, James has searched through the town on his quest for redemption. He has searched high and low and discovered certain things about the history of the town that he didn't understand before. Books and information on certain items of mystical power. So perhaps when he eventually reaches his conclusion as to what he feels his actions require, a second thought forms in his mind. Perhaps he makes his way all the way back to the parking lot where he left his car – and Mary's body – behind. Maybe Laura is with him, or Maria is with him, or he goes to drive into the lake. As he goes to leave, he thinks, “This doesn't feel right. This isn't what I deserve.” Because he just wants Mary. He can't go on without her. But now he understands how to get her back.

So he turns around and heads back to town, but the town wants him to feel it all over again. He has to earn his wife back. And as the town resets all the players and the pieces, it knows it will get what it really wants: a new servant, someone willing to perform rituals to the Old Gods that have not performed in far too long. And James, calm, peaceful, finally comes to terms with himself as he rows out to the island where the ritual must take place.

Because when you can resurrect someone, killing a person ain't no big deal.

***

With video games, sometimes there are multiple endings one can achieve based on their actions during their playthrough, just like in Silent Hill 2. But oftentimes, the developers will state outright which of the endings is the “true” ending so players can have a sense of satisfaction knowing how the story truly ends. However, in Silent Hill 2 every ending is canon. Developers Team Silent have stated that it's up to the players to determine which ending out of the possible four is how James Sunderland's story actually ends. There are, of course, two joke endings that the developers wisely have ensured remain in the realm of satire, leaving us to wonder and marvel at how one game can present so much ambiguity, while still remaining a concrete experience.

This we know: if all endings are canon, if it's truly up to the player, then anything goes. This essay, after all, is a fan theory. At no point have the developers ever hinted that anyone other than Maria is not real. The official novelization shows backstory for some of the characters, and even goes into their heads. Based on this, why extrapolate information to support a theory that has obviously been shown to be quite the opposite? Because – and here's the fun part – Silent Hill has always been a series about misdirection. Illusion, hallucinations of visual and audio types, and concealed intention. Disguises abound in Silent Hill, in each game. Team Silent demonstrated that Maria is absolutely not a “real” person by any means, but still thinks and feels like one and has memories because the town created her to have them. She is presented as the only person in the game who understands who James is, what he's done, and her role in the story. It stands to reason that the town could have created these other characters, but simply not given them the awareness of their role to play. And, as I have hopefully detailed well enough, the compelling evidence linking them both to the town and to James is unmistakable and undeniable. Whether or not you, the reader, choose to support this theory yourself, well, there are many endings to this tale. Just as all of them are equally correct in their canon.

But the next time you play Silent Hill 2, perhaps you'll be invited to look a little closer, pay attention a bit harder, consider ideas that you hadn't considered before. One of the most beautiful things about this abstract masterpiece is that it opens itself to observation as well as deduction, and when a game this detailed and well-thought-out is kind enough to allow for this, it is only good of us to indulge.

Thank you all so much for your time.

#silent hill#silent hill 2#team silent#konami#playstation 2#ps2#survival horror#horror gaming#consoles#theory#ruby ranger#ck burch#ranger report#james sunderland#maria#laura#eddie#angela#mary shepard-sunderland#leave ending#in water ending#maria ending#rebirth ending

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion: DC and Marvel’s Multiverses Are Crucial To The Future of Superhero Film

Alright, buckle up kids, this is going to be a long one. Get some soda and some popcorn, or some green tea and avocado toast.

Back in the long-distant year of 1989, a little film called Batman released into theaters and became the film of the Summer. Directed by Tim Burton and starring Michael Keaton and Jack Nicholson as Batman and the Joker respectively, it was a cinematic triumph that heralded a new wave of superhero films taking their source material seriously. Followed up in 1992 by Batman Returns, a sequel which increased the fantastic elements but was criticized for its darker tones, Batman’s role in movies was cemented in place by continued success. Of course, Keaton and Burton would leave to be replaced by Val Kilmer as Batman with Joel Schumacher directing for 1995′s Batman Forever, with George Clooney stepping into the cape and cowl for 1997′s Batman and Robin, a wild disaster of a film which nearly destroyed Batman’s chances in movies. But then, in 2005, Christopher Nolan brought a gritty realism to the caped crusader in Batman Begins, and continued this successful experiment with 2008′s Best Film Of The Year, The Dark Knight, and 2012′s The Dark Knight Rises (which was....fine). By this time the DCEU was beginning to get started, so a new Batman was cast for Zack Synder’s 2016 Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, and this role went to Ben Affleck. He reprised the role in David Ayer’s Suicide Squad and Joss Whedon’s Justice League, but bowed out of the opportunity to write and direct his own solo Bat-flick. So director Matt Reeves was tapped to direct a new Batman film starring a controversial choice of Robert Pattinson as Batman. With all of this, the question of the past 30-odd years is: which is your favorite Batman? Which one was the best? And how do these films fit into an increasingly convoluted canon in which a film series is rebooted every ten years or so?

What if the answer is: they’re all great and they all fit into canon?

Now, before we think too hard about that, let’s take a look at Spider-Man’s cinematic installments, which is almost more convoluted and in a more compressed amount of time. Beginning with 2002′s Spider-Man directed by Sam Raimi and starring Tobey Maguire, the amazing wall-crawler enjoyed a fantastic amount of success on the big screen, followed up by one of the best superhero films of all time, 2004′s Spider-Man 2. But Spider-Man 3 in 2007 took all of that goodwill and smashed it into the ground with a failure almost as bad as Batman and Robin a decade earlier. Plans for a Spider-Man 4 were scrapped, and eventually in 2012 director Mark Webb and star Andrew Garfield would bring a brand new Spidey to life with The Amazing Spider-Man, and The Amazing Spider-Man 2 in 2014. Both films were lively and energetic, but criticized for trying to stuff too much into their films -- especially the second one. Sony Pictures was attempting to ramp up a cinematic universe much like Marvel Films was doing at the time, but it was too much too fast. 2017 brought another reboot of the moviefilm version of Spidey, this time directed by Jon Watts and starring Tom Holland, with Spider-Man: Homecoming, this time under Marvel Film’s banner (thanks to backdoor dealing), and another cinematic triumph in 2019′s Spider-Man: Far From Home. But, unlike Batman, Spider-Man’s dealings behind the scenes are nearly as convoluted as his series. Sony Pictures owned the rights to make Spider-Man flicks for years, until Marvel managed to make a ludicrous offer after Amazing 2 failed to catch on the way producers hoped. So Spidey came to the MCU under a joint production, which is how we got Homecoming and Far From Home, but also maintained a different universe with the Amazing films, and then 2018′s Venom, and a little animated motion picture also in 2018 by the name of Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse.

Class, this is where I would like to direct your attention to the origin of the extraordinary events we are discussing today. Or is it the origin?

Into The Spider-Verse successfully proved that not only is the idea of multiple universes all connecting on screen a good idea, it’s an Oscar winning idea. Spider-Verse is hands down the best animated superhero film ever, and one of the best superhero films period. But here we must take note of certain ideas. The film provided much setup for a world where young Miles Morales begins to emerge with spider powers, but then Spider-Man is killed right in front of him before he can learn how to use them. Enter a Spider-Man from a slightly different parallel dimension, who not only turns Miles around, but find himself inspired to realign his own life. Spider-people abound through the film, all of them having equal weight and the possibility of spawning their own franchise without having to worry about impacting the canon of other universes. This is something comic books have done for literal decades, but Spider-Verse did it with such care and devotion that it won Best Animated Picture and became a mainstream smash hit. Marvel and Sony both sit up at attention; could this work with the major mainstream films they’ve been producing? So the experiment begins: we have a teaser trailer for Morbius, based on a vampiric Spider-Man villain, which features a cameo from the Vulture character first seen in Homecoming. And after dropping hints that Tom Holland’s Spider-Man could cross over with Tom Hardy’s Venom, Jamie Foxx recently posted about being cast as Electro -- a role he played in Amazing Spider-Man 2 -- for the third Tom Holland Spidey flick. Pictures went up on his Instragram seeming to confirm that not only was this the same Electro, but that all three previous Spider-Men -- Maguire, Garfield, and Holland -- would team up for the film. Multiple universes collide, a live action Spider-Verse, where everyone is crossing over with each other. Now, this lines up perfectly with Marvel’s MCU plans, as Doctor Strange has established in his film that multiple universes exist, and his announced sequel is even titled Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. It’s here. It’s happening. Every Spider-Man film is canon, they’ve all happened, and we don’t need to worry about which of them make sense or belong. They all make sense.

But just before this announcement, a month or so ago DC let slip that their plans for an upcoming Flash movie are taking cues from the Flashpoint comic books, in which Barry Allen goes back in time and accidentally creates a brand new timeline that he has to correct. Michael Keaton has even been cast as Bruce Wayne, the same Bruce Wayne that he played 30-odd years ago, a casting choice many fans have been clamoring for for years. On top of that, once word was put out that Keaton’s role would be similar to Samuel L. Jackson’s role as Nick Fury in the MCU, Ben Affleck was reported to be joining the picture as Batman also, a team-up no one saw coming. Even Christian Bale is being courted to join the universe-spanning flick, but reportedly only if director Christopher Nolan gives his blessing. Multiple Batmen teaming up together in a Flash movie to combat crime? Of course I’ve already bought tickets. Batman is the biggest box-office draw outside of The Avengers. And this concept opens up plenty of opportunities for DC, who’ve done Elseworlds stories in the comic for years. Joker with Joaquin Phoenix proved that DC films not directly tied to the DCEU can and will do well on their own; The Batman with Pattinson will no doubt further confirm that. But now Batman Returns is once again a viable film mixed into a comic book cocktail of wonder and excitement? And what’s wonderful is that this isn’t DC’s first big attempt at this. Slowly and surely, The CW’s Arrowverse TV shows -- Arrow, The Flash, Supergirl, Legends of Tomorrow -- have been doing multiverse crossovers for years, building up to 2019′s mega-event Crisis on Infinite Earths, which saw Brandon Routh reprise his role as Superman from 2006′s Superman Returns, which itself is a sequel to Christopher Reeve’s Superman and Superman II. And for one wonderful scene, TV’s Flash, Grant Gustin, got to interact with the DCEU’s Flash, Ezra Miller, confirming that these TV and film universes are indeed one big cocktail of parallel lives and dimensions that all interconnect while still being separate. Hell, we even saw Burt Ward, Robin from the 1966 Batman show, alive and well an in his own little world. Batman ‘66 is part of the wider DC Multiverse! How crazy is that? And we even got a small tease that Batman ‘89 is part of all of this as well, when we got to see reporter Alexander Knox look up to the Batsignal in the sky as Danny Elfman’s iconic score played. In one fell swoop, in as few as a casual couple of cameos, DC made all of their live-action properties canon in the multiverse, meaning no matter which version you like the best, they all work together and work from a franchising and audience standpoint. The 1978 Superman and the 1989 Batman both existed in worlds that ran sidecar to 2019′s Joker and 2011′s Green Lantern. It’s wild, unprecedented in cinematic history, and wonderful for fans of all ages.

Why is this the future of superhero flicks, though? It ought to be simple: no matter what movies come out, no matter how wild or crazy or outside “canon” they seem to be, they all can work and they all can coexist without having to confuse fans. Many people were feeling the reboot fatigue as early as 2012′s Amazing Spider-Man, and while there was a huge tone shift between Batman Returns and Batman Forever, the Bat-films were considered all part of the same line until Batman Begins started all the way over. Now we have Batman 89 and Returns in one world, Forever and Batman and Robin in another (which was already a fan theory, mind you). Sequels that don’t line up with their predecessors can just be shunted into a hidden multiverse timeline and left alone without the convoluted explanation of having to “ignore” certain sequels. Superman III & IV were ignored when Superman Returns chose to connect only to the first and second films, but now we can say that they definitely happened....just somewhere else. There is now a freedom of ideas and creation that can once again occur when making big-budget films based on superheroes. No longer do creative minds need to be restrained to the canon and timeline and overarching plots defined by studios years in advance; “creative differences” don’t need to drive frustrated directors away from characters or stories they truly love. Possibly -- just possibly -- good ideas can become the gold standard once again for comic book films, not just ten-year plans for how to get Captain America from scrawny Marine to Mjolnir-wielding badass. Remember when filmmakers decided to make Joker the same person who killed Bruce Wayne’s parents? Or when they decided to give Spider-Man the ability to shoot webs from his body instead of technology? That certainly wouldn’t fly these days; studio mandates would require adherence to previously established guidelines, or at least what has been seen in the comic. What if now we could get a three-episode limited series on HBO Max of Gotham By Gaslight? Or a big-budget adaptation of Marvel’s 1602? Simply trying to wedge old comic book storylines into existing Cinematic Universes no longer need be a thing! We could get some of the wildest interpretations of superheroes this side of Superman: Red Son. At least, that’s the hope, anyway.

When comic books can step away from canon for just a few minutes, worlds open up and expand. An entire multiverse of ideas can become a feast of entertainment for many. And when there’s already so many beautiful, well-told stories set in alternate universes as comic book precedent, so too can there be beautiful, well-told stories set in alternate universes for film. And the best part? Now they all matter. And I think that’s the future.