#African wealth

Text

The Ones Who Claimed Africa's Whole Gold Inventory

At any point might you at some point comprehend that Elon, musk, Jeff, Bezos or Bernard Arnold are only walking around the domain of the rich? In no way, shape or form these refined men have shot themselves to an unbelievable status, standing side by side with the titans of abundance all through the chronicles of history. Presently, how about we set out on a fascinating excursion to investigate and reveal the tales of the genuine heavyweights. Who've made a permanent imprint on the abundance scene across hundreds of years, John d Rockefeller. While diving into the records of history's most affluent people, we unavoidably experience faces that become the stuff of dreams for scheme, scholars around the world, john d Rockefeller is exactly one such figure.

#Africa#gold#wealth#history#colonization#European conquest#resource exploitation#African riches#gold mining#imperialism#economic exploitation#African history#colonization of Africa#African resources#gold reserves#African wealth#European settlers#African colonization#European imperialism#gold production#African economy#European powers#African nations#colonialism#African civilizations#African gold trade#European dominance#African exploitation#African heritage

0 notes

Photo

Rema rocking Kenzo boots in the Rolls-Royce Cullinan

#Rema#HEIS#Afrobeats#Fashion#High Fashion#Kenzo#Kenzo Paris#Luxury#Luxury Fashion#Drip#Drip Check#melanin#black excellence#African#African Artist#Rolls Royce#Ciullinan#Wealth

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Effeminate & Ebony Equestrian

#old money aesthetic#old money#stealth wealth#equestrian#black gay men#gay#african american#lgbt#black gay magic#blackboyjoy#gay pride#lgbt pride#my collage#black pride#polo ralph lauren#polo#horses#cottage aesthetic#aesthetic#black academia#classic academia#Academia

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

KWAME TURE EXPOSED THE PETTY BOURGEOISIE

All-African People's Revolutionary Party organiser Kwame Ture delivered a fiery speech many years ago in Chicago, USA, exposing the treachery and corruption of the African petty bourgeoisie. He denounced wealthy Africans for indulging in luxury and wealth, while most of the people endured poverty, disease and oppression. He added the petty bourgeoisie collaborated with the colonial and imperial powers that had exploited and oppressed Africa for centuries.

Ture also criticized wealthy Africans in the United States for being opportunistic and reactionary, because they have exploited the struggle of the African masses to gain power. Ture said they cooperated with the racist and capitalist system that had enslaved and oppressed Africans for centuries. He said the people must rise up without pity and without mercy to crush these 'reactionary pigs,' a term used for those who have resisted liberation via revolution. The revolutionary said this was unavoidable and justified, as part of the global struggle against imperialism and capitalism.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aarinola-The centre of wealth-Yoruba

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#africans#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#aarinola#yoruba#wealth#centre of weath#yoruba name#yoruba culture

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

May the new year bring you health, wealth, and knowledge of self.

#happy new year#blackgirlmagic#black women#black art#love poetry#2023#nyeparty#health#wealth#knowledge#stardom#goddess#black goddess#liminal spaces#outer space#awakening#awakethesoul#meditation#african tradition#africa#fireworks#peace and love

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jason Statham x Rosie Huntington-Whiteley at

Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque

#architecture#islamic#sheikh zayed grand mosque#jewish-christian-moslem love#appreciation#religion#friendships#success#co-operation#wealth#photography#actors#sheikhs#arabian#hebrew#eurasian-african#middle eastern

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spectator: The fact that collapses the case for slavery reparations

The case for slavery reparations seems to be growing louder every day. This week, indigenous representatives from 12 Commonwealth countries called on King Charles to begin the process of paying reparations. The King has personally expressed sorrow for the suffering of slaves and Buckingham Palace has said that it is taking the issue of reparations ‘profoundly seriously’. Earlier this year, a former BBC journalist committed to sending £100,000 in aid to the Caribbean to atone for her own family’s historical links to the slave trade.

The voluntary role that many Africans played in the transatlantic slave trade is ignored

The central thesis of slavery reparations is that white majority countries owe money to ethnic minorities as their ancestors may have enslaved others or benefited from a slave-system economy.

There is a problem with this though: ultimately, the great evil of slavery was practised by all inhabited continents and all races. And there will be almost no one alive today in the world who doesn’t have an ancestral link to the slave trade. This fact collapses the modern-day reparations argument.

Take the Afro-Omani slave trader Tippu Tip, who in 1895 was reported to have seven plantations and own 10,000 slaves. He was one of the largest slavers in all of East Africa.

Most popular

The sad truth about Phillip Schofield

Long before the transatlantic slave trade began, slavery was commonplace in many parts of the globe. As Al-Tabari, the Muslim scholar, showed in the mid-ninth century, the Basra port at al-Ahwaz alone had about 15,000 enslaved workers. Even in New Zealand, Maori chiefs enslaved prisoners of war – occasionally going as far as eating them in tribal feasts. The further you go back in history the longer the list of slavers grows, including everyone from the Ancient Egyptians to the Shang dynasty in China.

Given that many of the nations now calling for reparations also enslaved and sold others, the reparations argument when brought to its logical conclusion would have to demand that descendants of African slavers owe reparations to those who may have been the victims of slavery.

This argument could even be applied to the white descendants of the victims of the Barbary slave trade. Though undoubtedly far smaller than the transatlantic slave trade, the Barbary trade still saw over one million Europeans captured by North African pirates in slave raids between the 16th and 18th centuries.

So why is this devastating blow to the reparations argument often ignored? Politically, it seems that although we generally accept that slavery was universal in ancient history, we often pretend that only European powers practised slavery from the 16th century onwards, when this is clearly not the case. Meanwhile, the voluntary role that many Africans played in the transatlantic slave trade is also ignored.

Generally the European powers, with the exception of Portugal, lacked the resources to delve deep into the African continent for slaves. They were instead met at the coast by willing traders looking to make a profit by selling their fellow man. Though it is undoubtedly true that the rise of the transatlantic trade encouraged the growth of African slavers, this does not excuse those who took part in the trade.

Nor did slavery end in Africa when European colonialists were removed from the continent. When the Portuguese were forced off the East African Coast in 1699 by the Imam of the Omani Empire, he himself owned about 1,700 slaves.

The same is true for colonies outside Africa. In the early 1820s, Brazil broke away from the Portuguese Empire. Despite its later anti-slavery treaties with the UK, Brazil would continue importing about 750,000 slaves between 1831-1850. In 1844 it refused to renew the Anglo-Brazilian anti-slave trade agreement. Brazil’s slave trade only effectively stopped after 1850 when the UK formed a naval blockade in its coastal waters.

During the age of abolition led by Britain, the King of Dahomey (a West African Kingdom in modern day Benin) reportedly protested to a British officer that:

‘The slave trade has been the ruling principle of my people. It is the source of their glory and wealth. Their songs celebrate their victories and the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery.’

Some independent African nations and empires continued to allow slavery well after abolitionism in Europe. This was especially true in the eastern side of Africa where it was more difficult for the British to influence local politics and for the Royal Navy to enforce abolition.

From the 1860s onwards, Bemba chiefs in North-Eastern Zambia traded ivory and slaves for guns. As the supply of elephants for ivory depleted, the chiefs moved to selling even more slaves. In Barotseland, the monarch Lewanika was considered king of the Barotses, a South African ethnic group. From the beginning of his reign in 1878 until the region became a British protectorate, oral sources claim that up to a third of his subjects were slaves.

There is no question that the Euro-American trade in slaves – which began with Portugal and later included other colonial powers like France and Britain – was huge in size. This evil should never be forgotten.

But neither should we forget that people from all parts of the world, races and religions took part in what was one of the most horrid systems in human history.

In many parts of the world today, slavery is still rife. Rather than trying to create division by blaming people for the sins of their ancestors, we should instead come together to try and solve the problems we face today.

#The fact that collapses the case for slavery reparations#Reparations#African enslaved#enslaved Africans#British wealth born from the labor of Enslaved Africans

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A linguistics blog I follow put this post on my dash and it made me 😑 at it. Like. On the one hand while I get what they’re trying to say here and if it weren’t for the fact that they literally were one of the biggest actors in colonialism I might’ve been like yeah on a linguistic level every language has value. But again, because of the fact that they literally were one of the biggest actors in colonialism I really dgaf. You can handle being made fun of. You literally caused Apartheid!! Hello!!!

#i don’t give a fuck 😭 oh boo hoo people don’t love our language#return the stolen wealth 😭 and get your ‘African’ whites too bc they’re so fucking annoying

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rema seen decked out in diamonds at his NYC Rave

#Rema#HEIS#Album#Release#Party#Jewelry#Diamonds#Chain#Necklace#Cuban Links#Watch#Rolex#audemars piguet#hublot#Richard mille#photography#club photography#nightlife#afrobeats#africa#african art#rich#money#wealth

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

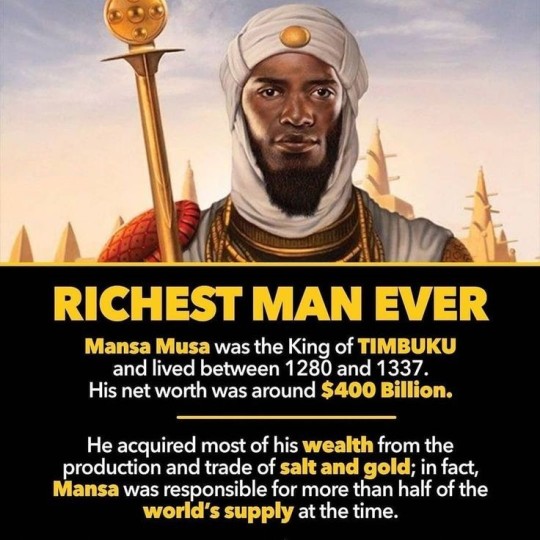

The only billionaire that was right

#if it needs to be said I am making a joke about how he redistributed his wealth to a comical extent#shitpost#history#billionares shouldnt exist#history buff#african history#Mansa Musa

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Boating Boys

Don’t we all love summers on a maritime vehicle!

#my collage#gay#african american#black gay men#black gay magic#blackboyjoy#gay pride#lgbt pride#black pride#lgbt#maritime#boating#yachtlife#old money#boat boys#boatlife#yacht#luxury yacht#moodboard#quiet luxury#stealth wealth#european summer#italian summer

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The slave trade and the British economy

Today, we view the history of slavery in terms of its horrific human impact but in the 18th and 19th Century financial considerations dominated the interests of those involved in the slave trade. Enslaved people were seen as property and their experience as human beings was not considered.

The British economy was transformed by the Atlantic slave trade. In 1700, 80 per cent of British trade went to Europe from ports on the east and south coasts.

By 1800, 60 per cent of British trade went to Africa and America, sailing from the three main west coast ports - Glasgow, Liverpool and Bristol.

Ports such as London, Bristol and Liverpool prospered as a direct result of involvement in the slave trade. Other ports, such as Glasgow, profited from the tobacco trade. Thousands of jobs were created in Britain supplying goods and services to slave traders.

In a period that saw Britain industrialise, profits could be made by exporting manufactured British goods to Africa and then further profits accrued from imported products made using enslaved labour, such as sugar, which became very fashionable with the British people.

The slave trade was important in the development of the wider economy - financial, commercial, legal and insurance institutions all emerged to support the activities of the slave trade. Some merchants became bankers and many new businesses were financed by profits made from slave trading.

The slave trade played an important role in providing British industry with access to raw materials. This contributed to the increased production of manufactured goods.

Slave trade and the British economy

British profits were made from exporting manufactured goods to Africa and importing products of enslaved labour such as sugar. Ports such as Glasgow, Bristol and Liverpool prospered as a result of the slave trade.

The importance of tropical crops

The climate and land in the West Indies were suited to the growing of luxury crops such as sugar, coffee, tobacco and cotton. The most important of these was sugar. 70 per cent of enslaved people worked producing sugar.

Sugar and tobacco grew very popular in the 18th century, and Britain made large profits from trade in these fashionable products.

As a result there was a dramatic change in the pattern of exports. Exports of manufactured goods to the Atlantic economy increased massively during the 1700s.

British exports in 1700 and 1800:17001800Europe82%21%North America (a)6%32%West Indies (b)5%25%Africa (c)2%4%Atlantic economy (a + b + c)13% (6 + 5 + 2)61% (32 + 25 + 4)

In 1700, 80 per cent of British trade went to Europe from ports on the east and south coasts.

By 1800, 60 per cent of British trade went to Africa and America, often sailing from the three main west coast ports of Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow. British exports in 1800 were four times higher than in 1700.

Were these changes due to the slave trade?

The Atlantic ports grew in part because so many of the slave ships sailed from these ports. But they grew as much from their general involvement with the Atlantic economy as from trading in enslaved people.

This provokes a ‘what if’ question. What if there had been no enslaved Africans in the Caribbean?

It is safe to guess that the trade would still have taken place. Trade regulations made sure that exports to the colonies came from Britain. But without the Atlantic slave trade it would have taken many, many years for a workforce to be established in the colonies. The growth of exports to the colonies would have been much, much slower.

The role of the trade in navigation

The slave trade contributed to the growth of the both the Royal Navy and the United Kingdom's merchant navy.

The Royal Navy grew during the period of conflict for control of the colonies. Once Britain had grown to dominate the Caribbean, the Navy was still needed to protect these colonies and British shipping.

The Atlantic economy in 1700s

The growth of trade in enslaved people, in plantation crops and in exports to American and Caribbean colonies led to a growth in shipping.

Overseas trade was carried out within the rules of the Navigation Acts. These stated that all commodity trade should take place in British ships, manned by British seamen, trading between British ports and those within the Empire.

Additional laws were introduced that gave British shipping companies an advantage over foreign competitors:

the Molasses Act of 1733 banned the import of foreign sugar to North America

the Direct Export Act of 1739, allowed British planters to ship goods directly to Europe

A network of trading links between Europe, Africa and the Americas developed. The most well-known part was the triangular trade route:

goods such as guns and brandy were taken from Britain to Africa to exchange for enslaved people

enslaved people were transported on the 'Middle Passage' across the Atlantic to sell in the West Indies and North America

cargoes of sugar, tobacco and other commodities were transported to Britain for sale

The slave trade was an important training ground for British seamen, providing experienced crews for the merchant marine and the Royal Navy.

However, the high death rate, particularly from disease, meant that the slave trade could also be considered a graveyard for seamen.

Manufacturing

Economic growth and the industrial revolution

Many historians describe the industrial revolution as a process rather than as an event. The part that exports played can be shown as a virtuous circle:

Cotton

From 1750 onwards a new industry emerged in Britain - the production of cotton cloth. Wool production had previously been Britain's major industry, but cotton had one key advantage - machinery could process cotton fibres better than wool.

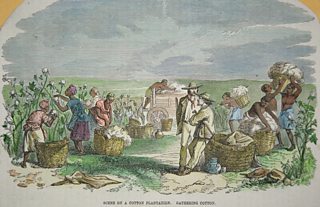

Slaves picking cotton

As a result it was in cotton production that the industrial revolution began, particularly in and around Manchester. The cotton used was mostly imported from slave plantations. Slavery provided the raw material for industrial change and growth.

The growth of the Atlantic economy was an integral part of the growth of exports - for example manufactured cotton cloth was exported to Africa.

Key features of the industrial revolution included:

Products were made in factories instead of at home

Workers used machines instead of working by hand

The machines were driven by water or steam power

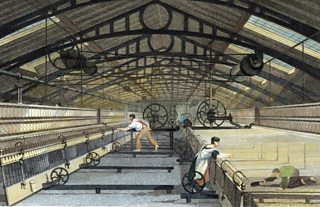

One worker could produce much more each day: eg a cotton spinner could spin 200 times as much in 1800 compared to 1700

Cotton became Britain's greatest export industry

Cotton being spun in a factory

The procurement of raw materials and trading patterns

The slave trade was important in providing British industries with raw materials. These were turned into manufactured goods in Britain and then sold for large profits in Europe and in the colonies.

Plantation-grown goods such as rum, tobacco, coffee, sugar, molasses and cotton were bought from the profits of selling enslaved African people to the plantation owners and sold for a profit in Britain and Europe.

The most obvious and dramatic effects of the Atlantic slave trade were changes to the Atlantic coast ports of Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow.

Growth of ports

Port Glasgow, 18th century

In 1700 Liverpool and Bristol were small towns. Glasgow’s population was around 12 000. This figure quadrupled in 100 years. These three ports had become important cities by 1800, largely as a result of trade in enslaved people or plantation-grown products:

Liverpool grew wealthy from plantation-grown cotton

Bristol’s wealth was partly based on sugar produced using enslaved people for labour

Glasgow became the United Kingdom's main tobacco port

Shipping

The shipping industry grew enormously. Most of the British slaving ships were fitted in these ports. There was as much work involved in building, fitting and repairing the ships as in sailing them. Liverpool became a major shipbuilding city as a result of the slave trade.

Trade with the Caribbean employed half of Britain’s long distance ships. Many ship owners involved in the slave trade were also plantation owners. Often profits were spent by merchants around the ports.

Impact of profits

Many plantation owners, especially in Scotland, built large town or country houses. Some endowed schools and other public buildings with money from plantation slavery. For example, in Bristol, the merchant Edward Colston, who made huge profits from the Triangular Trade, donated an estimated £100,000 to the city, including the foundation of a boys’ school named after him.

Industrial development

Industrial economy

There was a growth in manufacturing industries that supplied slave traders. Demand grew for goods such as guns, alcohol, pots, pans and textiles that were exchanged for captured Africans on the Outward Passage.

Profits from the slave trade were invested in the development of British industries. Canals and railways too were built as a result of investment of profits from the slave trade.

Wealth generated by the slave trade meant that domestic taxes could be kept low which further stimulated investment. However, by the end of the 18th century the slave trade had become less important in economic terms. It has been argued that only a small percentage of the profits from the slave trade were directly invested as capital in the industrial revolution.

There were other factors that contributed to industrial development in the UK:

Technological change brought new, cheaper, quicker and more efficient processes and manufacturing

The development of water and steam powered the Industrial Revolution. This powered the new machines for both spinning and weaving and led to the rapid spread of factories

Transport changes in the form of the canals and railways allowed heavy goods to be carried easily and cheaply

Increased production of coal and iron powered factories provided the fuel and materials for more manufacturing

Agricultural economy

Britain gradually changed between 1700 and 1850 from being mainly an agricultural economy, where people lived in the countryside, to mainly an industrial economy where people lived in cities. Changes in agriculture included:

enclosure

mechanisation

crop rotation

selective breeding

These changes helped create a food surplus. In turn this could feed an expanding population. This produced a labour force in the towns for use in factories and created a financial surplus for investment in industry and infrastructure.

Wealth of ports and merchants

Bristol

In the early 18th century Bristol dominated the British end of the slave trade. Bristol merchants established strong trade links with West Africa. The boom for Bristol was created through this slave trading success. Industries such as sugar-refining grew as a result of the slave trade.

Liverpool

Liverpool also grew into a powerful city, directly through the shipping of enslaved people. By the end of the 18th century Liverpool controlled over 60 per cent of the entire British slave trade. Liverpool's cotton and linen mills and other subsidiary industries such as rope-making created thousands of jobs supplying goods to slave traders. By the 1780s, Liverpool had become the largest slave ship building site in Britain.

Glasgow

London in the 18th century

Other ports such as Glasgow profited from the slave trade. In Glasgow the tobacco trade contributed hugely to the profits and development of the city. The 'tobacco lords' as the merchants of Glasgow became known, made a lot of money dealing in tobacco, not from dealing in enslaved people directly.

London

London was already trading in enslaved African people before 1700. It continued to be Britain's main port for slave ships, but merchants found other ways to make money. The Atlantic trade, including the slave trade, provided the impetus to develop merchant banking.

Growth of merchant banking

A satirical engraving on upper class wealth in the British Stock Exchange

Merchants made their money from buying goods at low prices and selling them at high prices. But they didn't receive this profit until after the voyage and after the goods had been sold. A voyage could take six months or longer.

In the meantime, merchants had to finance the voyage, paying for the ship and sailors. They also carried the risk that the ship might be lost at sea. It was also up to the merchant to find outlets to sell the goods.

Specialist skills developed around each part of the process of trading. Financial, commercial, legal and insurance institutions emerged to support the activities of the slave traders:

David and Alexander Barclay set up Barclays Bank

Sir Francis Baring started Barings Bank

London became a centre for marine insurance. Lloyds of London, founded in 1688, is still the world's leading insurance marketplace.

Atlantic slave trade profits also went to anyone who was wealthy enough to buy shares in the newly invented joint stock companies.

The South Sea Trading Company was set up in 1711, and it invested in the slave trade and in plantations. Its shares were very popular and rose rapidly in value. This led to the first "boom and bust" in Britain, the South Sea Bubble of 1720. The profits from the South Sea Trading Company were spread throughout the upper classes.

Wealth created by British slave traders

It is debatable how much the wealth created contributed to the British economy.

The slave trade offered an opportunity to get rich quick and many traders grew wealthy from its profits. But it was also a risky business with many investors making losses.

Merchants

Some merchants used their wealth to invest in British industries, banks and in new businesses. But other merchants and plantation owners invested elsewhere.

Much of the profits of slavery were spent on individual acquisition and dissipated in conspicuous consumption, for example merchants bought landed estates or had large town houses built as status symbols.

As regards funding the industrial revolution, profits from slavery roughly equated to the amount invested in new industries. Profits from the Atlantic economy were a recognisable contribution to the total profits of British businessmen. But it cannot be said that without these particular funds, investment in the industrial revolution would not have taken place.

Was Britain economically better off as a result of the slave trade?

Yes

Those that argue 'yes' point to houses, buildings and parks financed by the slave trade, and to the building of an empire.

No

Those that argue 'no' argue that only a narrow group of people profited. They claim that the estimates of those who support the 'yes' argument are exaggerated. They also point to the large costs of building and running an empire, including fighting wars related to its expansion and defence. These were paid for, in part by the taxpayer.

#The slave trade and the British economy#england#british colonialism#slave trade in britain#english slave trade#british monarchy and slavery#slave wealth#empire building on the blood of slavery of Africans

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

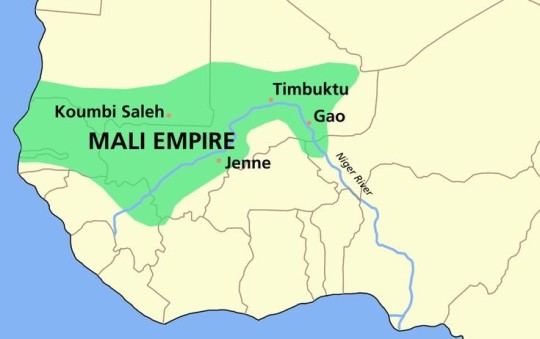

New Vocal Article. Africa’s Most Flamboyant Emperor: “King of Kings” Mansa Musa of the Mali Empire

“You’ve heard about the extraordinary wealth of Bill Gates, J.P. Morgan, and the sultan of Brunei, but have you heard of Mansa Musa, one of the richest men who ever lived?” - Cynthia Crossen

To find out more about the richest man who ever lived, Emperor Mansa Musa from medieval West Africa, click here: https://rb.gy/ueof7

1 note

·

View note