#Fair Use

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fandom and Fair Use: Spotlight on Recent Fair Use Discussions

In recognition of Fair Use Week, we want to spotlight some recent Fair Use discussions, including a defense of Jimmy Kimmel by OTW’s Rebecca Tushnet, tattoo fan art, and the copyrightability of AI-generated works. Read more at: https://otw-news.org/5avxxu78

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Publishers accused the nonprofit of infringing copyrights in 127 books from authors like Malcolm Gladwell, C.S. Lewis, Toni Morrison, J.D. Salinger and Elie Wiesel, by making the books freely available through its Free Digital Library.

The archive, which hosts more than 3.2 million copies of copyrighted books on its website, contended that the library was transformative because it made lending more convenient and served the public interest by promoting "access to knowledge.""

source 1

source 2

source 3

#destiel meme news#destiel meme#news#united states#us news#world news#internet archive#copyright#copyright law#copyright infringement#bookblr#protect access to knowledge#wayback machine#learning is a right#hachette v internet archive#hachette book group#penguin random house#harpercollins#wiley#open library#national emergency library#fair use#controlled digital lending

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Penguin Random House, AI, and writers’ rights

NEXT WEDNESDAY (October 23) at 7PM, I'll be in DECATUR, GEORGIA, presenting my novel THE BEZZLE at EAGLE EYE BOOKS.

My friend Teresa Nielsen Hayden is a wellspring of wise sayings, like "you're not responsible for what you do in other people's dreams," and my all time favorite, from the Napster era: "Just because you're on their side, it doesn't mean they're on your side."

The record labels hated Napster, and so did many musicians, and when those musicians sided with their labels in the legal and public relations campaigns against file-sharing, they lent both legal and public legitimacy to the labels' cause, which ultimately prevailed.

But the labels weren't on musicians' side. The demise of Napster and with it, the idea of a blanket-license system for internet music distribution (similar to the systems for radio, live performance, and canned music at venues and shops) firmly established that new services must obtain permission from the labels in order to operate.

That era is very good for the labels. The three-label cartel – Universal, Warner and Sony – was in a position to dictate terms like Spotify, who handed over billions of dollars worth of stock, and let the Big Three co-design the royalty scheme that Spotify would operate under.

If you know anything about Spotify payments, it's probably this: they are extremely unfavorable to artists. This is true – but that doesn't mean it's unfavorable to the Big Three labels. The Big Three get guaranteed monthly payments (much of which is booked as "unattributable royalties" that the labels can disperse or keep as they see fit), along with free inclusion on key playlists and other valuable services. What's more, the ultra-low payouts to artists increase the value of the labels' stock in Spotify, since the less Spotify has to pay for music, the better it looks to investors.

The Big Three – who own 70% of all music ever recorded, thanks to an orgy of mergers – make up the shortfall from these low per-stream rates with guaranteed payments and promo.

But the indy labels and musicians that account for the remaining 30% are out in the cold. They are locked into the same fractional-penny-per-stream royalty scheme as the Big Three, but they don't get gigantic monthly cash guarantees, and they have to pay the playlist placement the Big Three get for free.

Just because you're on their side, it doesn't mean they're on your side:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

In a very important, material sense, creative workers – writers, filmmakers, photographers, illustrators, painters and musicians – are not on the same side as the labels, agencies, studios and publishers that bring our work to market. Those companies are not charities; they are driven to maximize profits and an important way to do that is to reduce costs, including and especially the cost of paying us for our work.

It's easy to miss this fact because the workers at these giant entertainment companies are our class allies. The same impulse to constrain payments to writers is in play when entertainment companies think about how much they pay editors, assistants, publicists, and the mail-room staff. These are the people that creative workers deal with on a day to day basis, and they are on our side, by and large, and it's easy to conflate these people with their employers.

This class war need not be the central fact of creative workers' relationship with our publishers, labels, studios, etc. When there are lots of these entertainment companies, they compete with one another for our work (and for the labor of the workers who bring that work to market), which increases our share of the profit our work produces.

But we live in an era of extreme market concentration in every sector, including entertainment, where we deal with five publishers, four studios, three labels, two ad-tech companies and a single company that controls all the ebooks and audiobooks. That concentration makes it much harder for artists to bargain effectively with entertainments companies, and that means that it's possible -likely, even – for entertainment companies to gain market advantages that aren't shared with creative workers. In other words, when your field is dominated by a cartel, you may be on on their side, but they're almost certainly not on your side.

This week, Penguin Random House, the largest publisher in the history of the human race, made headlines when it changed the copyright notice in its books to ban AI training:

https://www.thebookseller.com/news/penguin-random-house-underscores-copyright-protection-in-ai-rebuff

The copyright page now includes this phrase:

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems.

Many writers are celebrating this move as a victory for creative workers' rights over AI companies, who have raised hundreds of billions of dollars in part by promising our bosses that they can fire us and replace us with algorithms.

But these writers are assuming that just because they're on Penguin Random House's side, PRH is on their side. They're assuming that if PRH fights against AI companies training bots on their work for free, that this means PRH won't allow bots to be trained on their work at all.

This is a pretty naive take. What's far more likely is that PRH will use whatever legal rights it has to insist that AI companies pay it for the right to train chatbots on the books we write. It is vanishingly unlikely that PRH will share that license money with the writers whose books are then shoveled into the bot's training-hopper. It's also extremely likely that PRH will try to use the output of chatbots to erode our wages, or fire us altogether and replace our work with AI slop.

This is speculation on my part, but it's informed speculation. Note that PRH did not announce that it would allow authors to assert the contractual right to block their work from being used to train a chatbot, or that it was offering authors a share of any training license fees, or a share of the income from anything produced by bots that are trained on our work.

Indeed, as publishing boiled itself down from the thirty-some mid-sized publishers that flourished when I was a baby writer into the Big Five that dominate the field today, their contracts have gotten notably, materially worse for writers:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/06/19/reasonable-agreement/

This is completely unsurprising. In any auction, the more serious bidders there are, the higher the final price will be. When there were thirty potential bidders for our work, we got a better deal on average than we do now, when there are at most five bidders.

Though this is self-evident, Penguin Random House insists that it's not true. Back when PRH was trying to buy Simon & Schuster (thereby reducing the Big Five publishers to the Big Four), they insisted that they would continue to bid against themselves, with editors at Simon & Schuster (a division of PRH) bidding against editors at Penguin (a division of PRH) and Random House (a division of PRH).

This is obvious nonsense, as Stephen King said when he testified against the merger (which was subsequently blocked by the court): "You might as well say you’re going to have a husband and wife bidding against each other for the same house. It would be sort of very gentlemanly and sort of, 'After you' and 'After you'":

https://apnews.com/article/stephen-king-government-and-politics-b3ab31d8d8369e7feed7ce454153a03c

Penguin Random House didn't become the largest publisher in history by publishing better books or doing better marketing. They attained their scale by buying out their rivals. The company is actually a kind of colony organism made up of dozens of once-independent publishers. Every one of those acquisitions reduced the bargaining power of writers, even writers who don't write for PRH, because the disappearance of a credible bidder for our work into the PRH corporate portfolio reduces the potential bidders for our work no matter who we're selling it to.

I predict that PRH will not allow its writers to add a clause to their contracts forbidding PRH from using their work to train an AI. That prediction is based on my direct experience with two of the other Big Five publishers, where I know for a fact that they point-blank refused to do this, and told the writer that any insistence on including this contract would lead to the offer being rescinded.

The Big Five have remarkably similar contracting terms. Or rather, unremarkably similar contracts, since concentrated industries tend to converge in their operational behavior. The Big Five are similar enough that it's generally understood that a writer who sues one of the Big Five publishers will likely find themselves blackballed at the rest.

My own agent gave me this advice when one of the Big Five stole more than $10,000 from me – canceled a project that I was part of because another person involved with it pulled out, and then took five figures out of the killfee specified in my contract, just because they could. My agent told me that even though I would certainly win that lawsuit, it would come at the cost of my career, since it would put me in bad odor with all of the Big Five.

The writers who are cheering on Penguin Random House's new copyright notice are operating under the mistaken belief that this will make it less likely that our bosses will buy an AI in hopes of replacing us with it:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/09/ai-monkeys-paw/#bullied-schoolkids

That's not true. Giving Penguin Random House the right to demand license fees for AI training will do nothing to reduce the likelihood that Penguin Random House will choose to buy an AI in hopes of eroding our wages or firing us.

But something else will! The US Copyright Office has issued a series of rulings, upheld by the courts, asserting that nothing made by an AI can be copyrighted. By statute and international treaty, copyright is a right reserved for works of human creativity (that's why the "monkey selfie" can't be copyrighted):

https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/20/everything-made-by-an-ai-is-in-the-public-domain/

All other things being equal, entertainment companies would prefer to pay creative workers as little as possible (or nothing at all) for our work. But as strong as their preference for reducing payments to artists is, they are far more committed to being able to control who can copy, sell and distribute the works they release.

In other words, when confronted with a choice of "We don't have to pay artists anymore" and "Anyone can sell or give away our products and we won't get a dime from it," entertainment companies will pay artists all day long.

Remember that dope everyone laughed at because he scammed his way into winning an art contest with some AI slop then got angry because people were copying "his" picture? That guy's insistence that his slop should be entitled to copyright is far more dangerous than the original scam of pretending that he painted the slop in the first place:

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2024/10/artist-appeals-copyright-denial-for-prize-winning-ai-generated-work/

If PRH was intervening in these Copyright Office AI copyrightability cases to say AI works can't be copyrighted, that would be an instance where we were on their side and they were on our side. The day they submit an amicus brief or rulemaking comment supporting no-copyright-for-AI, I'll sing their praises to the heavens.

But this change to PRH's copyright notice won't improve writers' bank-balances. Giving writers the ability to control AI training isn't going to stop PRH and other giant entertainment companies from training AIs with our work. They'll just say, "If you don't sign away the right to train an AI with your work, we won't publish you."

The biggest predictor of how much money an artist sees from the exploitation of their work isn't how many exclusive rights we have, it's how much bargaining power we have. When you bargain against five publishers, four studios or three labels, any new rights you get from Congress or the courts is simply transferred to them the next time you negotiate a contract.

As Rebecca Giblin and I write in our 2022 book Chokepoint Capitalism:

Giving a creative worker more copyright is like giving your bullied schoolkid more lunch money. No matter how much you give them, the bullies will take it all. Give your kid enough lunch money and the bullies will be able to bribe the principle to look the other way. Keep giving that kid lunch money and the bullies will be able to launch a global appeal demanding more lunch money for hungry kids!

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

As creative workers' fortunes have declined through the neoliberal era of mergers and consolidation, we've allowed ourselves to be distracted with campaigns to get us more copyright, rather than more bargaining power.

There are copyright policies that get us more bargaining power. Banning AI works from getting copyright gives us more bargaining power. After all, just because AI can't do our job, it doesn't follow that AI salesmen can't convince our bosses to fire us and replace us with incompetent AI:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/11/robots-stole-my-jerb/#computer-says-no

Then there's "copyright termination." Under the 1976 Copyright Act, creative workers can take back the copyright to their works after 35 years, even if they sign a contract giving up the copyright for its full term:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/09/26/take-it-back/

Creative workers from George Clinton to Stephen King to Stan Lee have converted this right to money – unlike, say, longer terms of copyright, which are simply transferred to entertainment companies through non-negotiable contractual clauses. Rather than joining our publishers in fighting for longer terms of copyright, we could be demanding shorter terms for copyright termination, say, the right to take back a popular book or song or movie or illustration after 14 years (as was the case in the original US copyright system), and resell it for more money as a risk-free, proven success.

Until then, remember, just because you're on their side, it doesn't mean they're on your side. They don't want to prevent AI slop from reducing your wages, they just want to make sure it's their AI slop puts you on the breadline.

Tor Books as just published two new, free LITTLE BROTHER stories: VIGILANT, about creepy surveillance in distance education; and SPILL, about oil pipelines and indigenous landback.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/10/19/gander-sauce/#just-because-youre-on-their-side-it-doesnt-mean-theyre-on-your-side

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#publishing#penguin random house#prh#monopolies#chokepoint capitalism#fair use#AI#training#labor#artificial intelligence#scraping#book scanning#internet archive#reasonable agreements

731 notes

·

View notes

Text

Although U.S. copyright law allows "Weird Al" Yankovic to parody songs without permission, he chooses to ask artists first to keep good relationships. This means he sometimes skips parodies if the artist says no, like when Paul McCartney declined a parody of "Live and Let Die" because of his vegetarian views.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember when I told you Disney wasn't going to "save you" from AI?

Megacorps like Disney have mountains of exclusive data they "own" that they can use to create their own internal, proprietary, AI systems. They have every sketch, development photo, unused concept art piece, cut scene, note, doodle, rotoscope/animation reference footage, every storyboard, merch design document, you name it.

And that's on top of every single frame of every movie and TV show. Every panel of every comic.

That's why Disney supports the efforts to clamp down on AI for copyright reasons, because they own all the copyrights. They want that power in their hands. They do not want you to be able to use a cheap or free utility to compete with them. Along the way, they'll burn the entire concept of fair use to the ground and snatch the right to copyright styles. Adobe has confessed this intention, straight to congress.

When the lawyers come, you won't be accused of stealing from say, artist Stephen Silver. You'll be accused of stealing the style of Disney's Kim Possible(TM).

But don't listen to me. Listen to the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, you know how I said there was nothing ethical about Adobe's approach to AI? Well whaddya know?

Adobe wants your team lead to contact their customer service to not have your private documents scraped!

This isn't the first of Adobe's always-online subscription-based products (which should not have been allowed in the first place) to have sneaky little scraping permissions auto-set to on and hidden away, but this is the first one (I'm aware of) where you have to contact customer service to turn it off for a whole team.

Now, I'm on record for saying I see scraping as fair use, and it is. But there's an aspect of that that is very essential to it being fair use: The material must be A) public facing and B) fixed published work.

All public facing published work is subject to transformative work and academic study, the use of mechanical apparatus to improve/accelerate that process does not change that principle. Its the difference between looking through someone's public instagram posts and reading through their drafts folder and DMs.

But that's not the kind of work that Adobe's interested in. See, they already have access to that work just like everyone else. But the in-progress work that Creative Cloud gives them access to, and the private work that's never published that's stored there isn't in LIAON. They want that advantage.

And that's valuable data. For an example: having a ton of snapshots of images in the process of being completed would be very handy for making an AI that takes incomplete work/sketches and 'finishes' it. That's on top of just being general dataset grist.

But that work is, definitionally, not published. There's no avenue to a fair use argument for scraping it, so they have to ask. And because they know it will be an unpopular ask, they make it a quiet op-out.

This was sinister enough when it was Photoshop, but PDF is mainly used for official documents and forms. That's tax documents, medical records, college applications, insurance documents, business records, legal documents. And because this is a server-side scrape, even if you opt-out, you have no guarantee that anyone you're sending those documents to has done so.

So, in case you weren't keeping score, corps like Adobe, Disney, Universal, Nintendo, etc all have the resources to make generative AI systems entirely with work they 'own' or can otherwise claim rights to, and no copyright argument can stop them because they own the copyrights.

They just don't want you to have access to it as a small creator to compete with them, and if they can expand copyright to cover styles and destroy fanworks they will. Here's a pic Adobe trying to do just that:

If you want to know more about fair use and why it applies in this circumstance, I recommend the Electronic Frontier Foundation over the Copyright Alliance.

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pitfalls of Pictures

As polar fandom works its way into ever more serious circles, from social sharing to published works, I thought I might share what I've learned about copyright and using pictures you find online.

Copyright belongs to the person who made the image. This means the artist or photographer in most cases. The photographer is the one who opened the shutter, not the owner of the camera.

Copyright, in most places and cases, lasts for the life of the creator +70 years.

Many Heroic Age polar images are therefore out of copyright. BUT WAIT. That's the photo. If you find it online, it's been digitised by someone. The copyright of the digitised image legally belongs to whichever person, or institution, digitised the image. Therefore the same Ponting photo can be copyright SPRI, Getty, RGS, or Anne Strathie, who scanned it off an original print she bought on eBay. Print: uncopyrighted. Scanned image: copyrighted. Even though the picture is the same, they are discrete things.

A lot of polar photos have been digitised by educational institutions or regional/national archives. They have to balance their mission to drive engagement with the necessity of licencing fees to fund their work. Everyone has a different way of doing this, so it's worth your while to learn the policies of wherever you found the photo.

For the most part (BUT NOT ALWAYS!) so long as you're not making any money on the image or using it to further your career (i.e. just fangirling) you're probably OK. People generally only bother to rally the expensive lawyers when there's cash involved. However it is always worthwhile to check, because there is nuance.

Posting an image which has not previously been public onto a public website (e.g. Tumblr) legally counts as publishing it. If you've been given permission to access it and/or make your own digital copy, that does not necessarily mean you can share it online. There may be different rules around publishing it vs having it, even for free.

Example: In 2014 I photographed all the negatives of Meares' Siberian photos at the BC Archives. I wanted a proper scan of a few of them, for an article I was co-writing at the time. I was allowed to take as many pictures as I liked with my own camera for personal use, and was charged a small fee for the scans. However, if I were going to publish any of them, I would have to fill out paperwork with the BC Archives and pay another, much larger fee. In 2023, I learned that the BC Archives had changed their policy: one needed only to credit the Archives for the photo, with their specified text. I finally got to write my post about Scott's ponies and throw in the photos for free. So keep up to date on usage permissions, too!

Downloading an image and sharing it amongst your friends, via email or messaging or some other closed network, without posting it on a public platform, is not the same as publishing it. But your friends need to be clear that they can't publish it either.

Going into the code of a photo site to find the high-res version of an image? Technically no one can stop you.

Publicly posting that high-res image, which the image holder has buried in code so that people can't distribute it? Not OK.

Printing off merch with that image and selling it as a side hustle? WOW VERY NO.

There is another slightly hazy area called 'transformative works' in which you can take a copyrighted image and change it enough to count as a new image. I don't know if there are any hard and fast rules on this – and they probably vary by jurisdiction – but as a rule of thumb, you're generally OK if no one in their right mind would mistake your image for the original.

I don't think any of us want to raise the ire of the heritage bodies which feed our passion for this stuff, so please make sure to stay on their good side! Photo archives take space and refrigeration and expert curators, which are all very expensive, and this is generally paid for by licensing the photos they keep. (The photo library at SPRI, for example, is the only part of the institution which makes any profit.) So please play nice!

I am far from being an authority on this, just sharing what I've learned over my 15+ years of working with polar photos on and offline. Please research your specific cases, and add anything to this post which you think may be relevant!

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I recall some time ago you made a video of different techniques that can be used to avoid being flagged by YouTube's copyright detection system, do you still have that video? If not, can you offer other general tips? Thanks.

That was a thread on Twitter dot com (which I don't use anymore) but here's the quick version:

Copyright detection algorithms for video/audio basically hold up the original next to yours and judge how similar they are. So making your fair-use transformative work more and more different is the name of the game.

To this end there are a lot of techniques you can use:

- Leaving no more than 3 seconds of footage unedited (the most important technique)

- Edge cropping

- Letterboxing/adding a frame

- Decreasing contrast/saturation

- Adding noise

- Layering other semi-transparent sources

- Adjusting the color

- Mirroring the footage

- Changing the speed/pitch

- Warping the video

- Using filters

- Adding audio layers

- Intermittently inverting the audio waveform

- Separating voice and music

- Making the video move around

But the real trick is to combine combine combine! No single one of these is enough on its own. I make no guarantees about the effectiveness of this approach but it has served me fairly reliably for the last few years. Algorithms are getting more sophisticated with time but you can always get around them. Remember that a human person can still manually issue a takedown, so make sure what you post is something you can say is adequately transformative with confidence.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

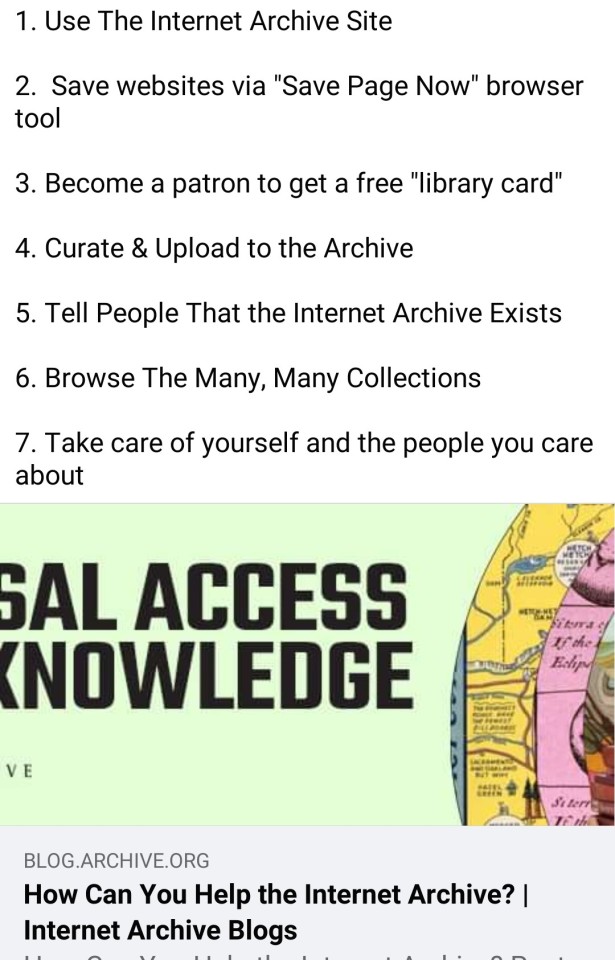

The Internet Archive is under attack by corporations seeking to wrest more and more of our fair use rights, our public spaces and our communities from the public good. The Archive was recently forced into a settlement for scanning and digitizing legally purchased books. They are now facing a $325 million lawsuit for accepting donations of old 78 RPM historical music records that were digitized by volunteers. The goal is not only to stop the distribution of these works, but to create new legal precedents that make it illegal to preserve or archive for any reason. This will have a significant impact on our culture, our communities, and our future

Here is how you can help them

1. Use The Internet Archive Site

2. Save websites via "Save Page Now" browser tool

3. Become a patron to get a free "library card"

4. Curate & Upload to the Archive

5. Tell People That the Internet Archive Exists

6. Browse The Many, Many Collections

7. Take care of yourself and the people you care about

(Link will take you to a blog article that goes into these suggestions in detail)

#the internet archive#internet archive#fair use#copyright abuse#capitalism#digital archiving#digitization#digital preservation#archiving#fandom history#our culture#our voices#our past#our present#our future#libraries

511 notes

·

View notes

Text

Negativland – Fair Use: The Story Of The Letter U And The Numeral 2 Book and CD

From a description from the Bleak Bliss blog

“In 1991, Negativland’s infamous U2 single was sued out of existence for trademark infringement, fraud, and copyright infringement for poking fun at the Irish mega-group’s anthem “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For.” In 1992, Negativland’s magazine-plus-CD "The Letter U and the Numeral 2" was sued out of existence for trying to tell the story of the first lawsuit. In 1995 Negativland released "Fair Use: The Story of the Letter U and the Numeral 2," a 270-page book-with-CD to tell the story of both lawsuits and the fight for the right to make new art out of corporately owned culture.

The overwhelming (and very funny) "Fair Use" takes you deep inside Negativland’s legal, ethical, and artistic odyssey in an unusual examination of the ironic absurdities that ensue when corporate commerce, contemporary art and pre-electronic law collide over one 13-minute recording (and to hear the actual single itself, go here: I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For - 1991 A Capella Mix (7:15) I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For - Special Edit Radio Mix (5:46) (Links inactive see below)

The book presents the progression of documents, events and results chronologically, contains the suppressed magazine in its entirety, and goes on to add much more that has happened since, to illuminate this modern saga of criminal music. Also included is a (at the time) definitive appendix of legal and artistic references on the fair use issue, including important court decisions, and a foreword written by the son of the American U-2 spy plane pilot shot down over the Soviet Union in 1960.

Packaged inside the book is a full-length CD containing a new 45-minute collage piece by Negativland, “Dead Dog Records”- which is both about artistic appropriation and an extensive example of it- plus a 26-minute “review” of the U.S. Copyright Act by Crosley Bendix, Director of Stylistic Premonitions for the Universal Media Netweb.”

For the book Fair Use doscumenting the legal battle between SST and Negativland you can get it from my Google Drive HERE

For rhe accompanying CD you can get that from my Google Drive HERE

And here is the thing that started it all you can get it Here

#negativland#u2#fair use#plunderphonics#noise#experimental#collage#abstract#sound collage#sst records

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

(copied from Zachary Berger on bluesky)

Hey US-based artists, our government is preparing an executive order on AI & asking for public comment. Let's get some letters in (AI corps sure are)! You must submit by 11:59 EST tonight!! I made a sample letter with submission instructions. Copy mine & augment, or write your own! bit.ly/429UIIw

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wards against the algorithm: "Fair-use golden trio"

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mickey art by @foxestacado; Magic Kingdom photo by @heidi8.

I took my first Copyright Law class in 1993; just after the term concluded, certain motion pictures had their copyrights restored because of NAFTA, but the copyright terms for things like the Marx Bros' Animal Crackers, and yes, the original Mickey Mouse cartoons including Steamboat Willie and Plane Crazy were supposed to expire by the early 2000s, free for use by anyone, for any purpose (other than trademark infringement).

As we all know, they did not; the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act stretched the term from 75 years to 95 years after first publication, keeping the public domain closed for 20 years -- but those 95 years expire at midnight on January 1, 2024 for Steamboat Willie -- as well as Virginia Woolf's Orlando, the picture book Millions of Cats, a few of my favorite songs from Burt Kalmar & Harry Ruby, and the first sound recording of "Yes! We Have No Bananas!"

What does this mean for creativity? It's unpredictable! Will there be more productions of Threepenny Opera? Stage musical versions of Animal Crackers -- or Marx Bros VR? More tiktoks and YouTube videos set to songs our great grandparents enjoyed, now that the sea shanty trend is over? Will there be horror movie versions of early Mickey cartoons, the way some indie filmmakers did a horror movie version of Winnie the Pooh when the first Milne book went into the public domain a few years ago? Will there be a sequel to that horror film featuring Tigger now that His Bounciness is entering the public domain? Will I do a video setting Mickey to "Mack the Knife"? Perhaps!

But I and everyone else needs to remember that Disney still holds trademark rights in Mickey Mouse -- the original version and the evolutions since -- so it'll be important to include a disclaimer or notice that any follow-on work based on things in the public domain is not owned, created or distributed by Disney or the other relevant brand-owner.

What will I be doing to mark the occasion? I'm planning on celebrating the public domain moment *at* Walt Disney World; I need to feel it in my soul; I expect fireworks, and absolutely no recognition from anyone other than me (and possibly my family who tolerate my ridiculousness on this) about the momentousness of the moment. I may livestream it.

I've been waiting for this moment for thirty years, and I can't believe I finally get to celebrate it this week! Creativity is magic, and it'll be fascinating to see what happens next!

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Copyright takedowns are a cautionary tale that few are heeding

On July 14, I'm giving the closing keynote for the fifteenth HACKERS ON PLANET EARTH, in QUEENS, NY. Happy Bastille Day! On July 20, I'm appearing in CHICAGO at Exile in Bookville.

We're living through one of those moments when millions of people become suddenly and overwhelmingly interested in fair use, one of the subtlest and worst-understood aspects of copyright law. It's not a subject you can master by skimming a Wikipedia article!

I've been talking about fair use with laypeople for more than 20 years. I've met so many people who possess the unshakable, serene confidence of the truly wrong, like the people who think fair use means you can take x words from a book, or y seconds from a song and it will always be fair, while anything more will never be.

Or the people who think that if you violate any of the four factors, your use can't be fair – or the people who think that if you fail all of the four factors, you must be infringing (people, the Supreme Court is calling and they want to tell you about the Betamax!).

You might think that you can never quote a song lyric in a book without infringing copyright, or that you must clear every musical sample. You might be rock solid certain that scraping the web to train an AI is infringing. If you hold those beliefs, you do not understand the "fact intensive" nature of fair use.

But you can learn! It's actually a really cool and interesting and gnarly subject, and it's a favorite of copyright scholars, who have really fascinating disagreements and discussions about the subject. These discussions often key off of the controversies of the moment, but inevitably they implicate earlier fights about everything from the piano roll to 2 Live Crew to antiracist retellings of Gone With the Wind.

One of the most interesting discussions of fair use you can ask for took place in 2019, when the NYU Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy held a symposium called "Proving IP." One of the panels featured dueling musicologists debating the merits of the Blurred Lines case. That case marked a turning point in music copyright, with the Marvin Gaye estate successfully suing Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for copying the "vibe" of Gaye's "Got to Give it Up."

Naturally, this discussion featured clips from both songs as the experts – joined by some of America's top copyright scholars – delved into the legal reasoning and future consequences of the case. It would be literally impossible to discuss this case without those clips.

And that's where the problems start: as soon as the symposium was uploaded to Youtube, it was flagged and removed by Content ID, Google's $100,000,000 copyright enforcement system. This initial takedown was fully automated, which is how Content ID works: rightsholders upload audio to claim it, and then Content ID removes other videos where that audio appears (rightsholders can also specify that videos with matching clips be demonetized, or that the ad revenue from those videos be diverted to the rightsholders).

But Content ID has a safety valve: an uploader whose video has been incorrectly flagged can challenge the takedown. The case is then punted to the rightsholder, who has to manually renew or drop their claim. In the case of this symposium, the rightsholder was Universal Music Group, the largest record company in the world. UMG's personnel reviewed the video and did not drop the claim.

99.99% of the time, that's where the story would end, for many reasons. First of all, most people don't understand fair use well enough to contest the judgment of a cosmically vast, unimaginably rich monopolist who wants to censor their video. Just as importantly, though, is that Content ID is a Byzantine system that is nearly as complex as fair use, but it's an entirely private affair, created and adjudicated by another galactic-scale monopolist (Google).

Google's copyright enforcement system is a cod-legal regime with all the downsides of the law, and a few wrinkles of its own (for example, it's a system without lawyers – just corporate experts doing battle with laypeople). And a single mis-step can result in your video being deleted or your account being permanently deleted, along with every video you've ever posted. For people who make their living on audiovisual content, losing your Youtube account is an extinction-level event:

https://www.eff.org/wp/unfiltered-how-youtubes-content-id-discourages-fair-use-and-dictates-what-we-see-online

So for the average Youtuber, Content ID is a kind of Kafka-as-a-Service system that is always avoided and never investigated. But the Engelbert Center isn't your average Youtuber: they boast some of the country's top copyright experts, specializing in exactly the questions Youtube's Content ID is supposed to be adjudicating.

So naturally, they challenged the takedown – only to have UMG double down. This is par for the course with UMG: they are infamous for refusing to consider fair use in takedown requests. Their stance is so unreasonable that a court actually found them guilty of violating the DMCA's provision against fraudulent takedowns:

https://www.eff.org/cases/lenz-v-universal

But the DMCA's takedown system is part of the real law, while Content ID is a fake law, created and overseen by a tech monopolist, not a court. So the fate of the Blurred Lines discussion turned on the Engelberg Center's ability to navigate both the law and the n-dimensional topology of Content ID's takedown flowchart.

It took more than a year, but eventually, Engelberg prevailed.

Until they didn't.

If Content ID was a person, it would be baby, specifically, a baby under 18 months old – that is, before the development of "object permanence." Until our 18th month (or so), we lack the ability to reason about things we can't see – this the period when small babies find peek-a-boo amazing. Object permanence is the ability to understand things that aren't in your immediate field of vision.

Content ID has no object permanence. Despite the fact that the Engelberg Blurred Lines panel was the most involved fair use question the system was ever called upon to parse, it managed to repeatedly forget that it had decided that the panel could stay up. Over and over since that initial determination, Content ID has taken down the video of the panel, forcing Engelberg to go through the whole process again.

But that's just for starters, because Youtube isn't the only place where a copyright enforcement bot is making billions of unsupervised, unaccountable decisions about what audiovisual material you're allowed to access.

Spotify is yet another monopolist, with a justifiable reputation for being extremely hostile to artists' interests, thanks in large part to the role that UMG and the other major record labels played in designing its business rules:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

Spotify has spent hundreds of millions of dollars trying to capture the podcasting market, in the hopes of converting one of the last truly open digital publishing systems into a product under its control:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/27/enshittification-resistance/#ummauerter-garten-nein

Thankfully, that campaign has failed – but millions of people have (unwisely) ditched their open podcatchers in favor of Spotify's pre-enshittified app, so everyone with a podcast now must target Spotify for distribution if they hope to reach those captive users.

Guess who has a podcast? The Engelberg Center.

Naturally, Engelberg's podcast includes the audio of that Blurred Lines panel, and that audio includes samples from both "Blurred Lines" and "Got To Give It Up."

So – naturally – UMG keeps taking down the podcast.

Spotify has its own answer to Content ID, and incredibly, it's even worse and harder to navigate than Google's pretend legal system. As Engelberg describes in its latest post, UMG and Spotify have colluded to ensure that this now-classic discussion of fair use will never be able to take advantage of fair use itself:

https://www.nyuengelberg.org/news/how-explaining-copyright-broke-the-spotify-copyright-system/

Remember, this is the best case scenario for arguing about fair use with a monopolist like UMG, Google, or Spotify. As Engelberg puts it:

The Engelberg Center had an extraordinarily high level of interest in pursuing this issue, and legal confidence in our position that would have cost an average podcaster tens of thousands of dollars to develop. That cannot be what is required to challenge the removal of a podcast episode.

Automated takedown systems are the tech industry's answer to the "notice-and-takedown" system that was invented to broker a peace between copyright law and the internet, starting with the US's 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act. The DMCA implements (and exceeds) a pair of 1996 UN treaties, the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the Performances and Phonograms Treaty, and most countries in the world have some version of notice-and-takedown.

Big corporate rightsholders claim that notice-and-takedown is a gift to the tech sector, one that allows tech companies to get away with copyright infringement. They want a "strict liability" regime, where any platform that allows a user to post something infringing is liable for that infringement, to the tune of $150,000 in statutory damages.

Of course, there's no way for a platform to know a priori whether something a user posts infringes on someone's copyright. There is no registry of everything that is copyrighted, and of course, fair use means that there are lots of ways to legally reproduce someone's work without their permission (or even when they object). Even if every person who ever has trained or ever will train as a copyright lawyer worked 24/7 for just one online platform to evaluate every tweet, video, audio clip and image for copyright infringement, they wouldn't be able to touch even 1% of what gets posted to that platform.

The "compromise" that the entertainment industry wants is automated takedown – a system like Content ID, where rightsholders register their copyrights and platforms block anything that matches the registry. This "filternet" proposal became law in the EU in 2019 with Article 17 of the Digital Single Market Directive:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2018/09/today-europe-lost-internet-now-we-fight-back

This was the most controversial directive in EU history, and – as experts warned at the time – there is no way to implement it without violating the GDPR, Europe's privacy law, so now it's stuck in limbo:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/05/eus-copyright-directive-still-about-filters-eus-top-court-limits-its-use

As critics pointed out during the EU debate, there are so many problems with filternets. For one thing, these copyright filters are very expensive: remember that Google has spent $100m on Content ID alone, and that only does a fraction of what filternet advocates demand. Building the filternet would cost so much that only the biggest tech monopolists could afford it, which is to say, filternets are a legal requirement to keep the tech monopolists in business and prevent smaller, better platforms from ever coming into existence.

Filternets are also incapable of telling the difference between similar files. This is especially problematic for classical musicians, who routinely find their work blocked or demonetized by Sony Music, which claims performances of all the most important classical music compositions:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/08/copyfraud/#beethoven-just-wrote-music

Content ID can't tell the difference between your performance of "The Goldberg Variations" and Glenn Gould's. For classical musicians, the best case scenario is to have their online wages stolen by Sony, who fraudulently claim copyright to their recordings. The worst case scenario is that their video is blocked, their channel deleted, and their names blacklisted from ever opening another account on one of the monopoly platforms.

But when it comes to free expression, the role that notice-and-takedown and filternets play in the creative industries is really a sideshow. In creating a system of no-evidence-required takedowns, with no real consequences for fraudulent takedowns, these systems are huge gift to the world's worst criminals. For example, "reputation management" companies help convicted rapists, murderers, and even war criminals purge the internet of true accounts of their crimes by claiming copyright over them:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/23/reputation-laundry/#dark-ops

Remember how during the covid lockdowns, scumbags marketed junk devices by claiming that they'd protect you from the virus? Their products remained online, while the detailed scientific articles warning people about the fraud were speedily removed through false copyright claims:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/10/18/labor-shortage-discourse-time/#copyfraud

Copyfraud – making false copyright claims – is an extremely safe crime to commit, and it's not just quack covid remedy peddlers and war criminals who avail themselves of it. Tech giants like Adobe do not hesitate to abuse the takedown system, even when that means exposing millions of people to spyware:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/10/13/theres-an-app-for-that/#gnash

Dirty cops play loud, copyrighted music during confrontations with the public, in the hopes that this will trigger copyright filters on services like Youtube and Instagram and block videos of their misbehavior:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/10/duke-sucks/#bhpd

But even if you solved all these problems with filternets and takedown, this system would still choke on fair use and other copyright exceptions. These are "fact intensive" questions that the world's top experts struggle with (as anyone who watches the Blurred Lines panel can see). There's no way we can get software to accurately determine when a use is or isn't fair.

That's a question that the entertainment industry itself is increasingly conflicted about. The Blurred Lines judgment opened the floodgates to a new kind of copyright troll – grifters who sued the record labels and their biggest stars for taking the "vibe" of songs that no one ever heard of. Musicians like Ed Sheeran have been sued for millions of dollars over these alleged infringements. These suits caused the record industry to (ahem) change its tune on fair use, insisting that fair use should be broadly interpreted to protect people who made things that were similar to existing works. The labels understood that if "vibe rights" became accepted law, they'd end up in the kind of hell that the rest of us enter when we try to post things online – where anything they produce can trigger takedowns, long legal battles, and millions in liability:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/04/08/oh-why/#two-notes-and-running

But the music industry remains deeply conflicted over fair use. Take the curious case of Katy Perry's song "Dark Horse," which attracted a multimillion-dollar suit from an obscure Christian rapper who claimed that a brief phrase in "Dark Horse" was impermissibly similar to his song "A Joyful Noise."

Perry and her publisher, Warner Chappell, lost the suit and were ordered to pay $2.8m. While they subsequently won an appeal, this definitely put the cold grue up Warner Chappell's back. They could see a long future of similar suits launched by treasure hunters hoping for a quick settlement.

But here's where it gets unbelievably weird and darkly funny. A Youtuber named Adam Neely made a wildly successful viral video about the suit, taking Perry's side and defending her song. As part of that video, Neely included a few seconds' worth of "A Joyful Noise," the song that Perry was accused of copying.

In court, Warner Chappell had argued that "A Joyful Noise" was not similar to Perry's "Dark Horse." But when Warner had Google remove Neely's video, they claimed that the sample from "Joyful Noise" was actually taken from "Dark Horse." Incredibly, they maintained this position through multiple appeals through the Content ID system:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/03/05/warner-chappell-copyfraud/#warnerchappell

In other words, they maintained that the song that they'd told the court was totally dissimilar to their own was so indistinguishable from their own song that they couldn't tell the difference!

Now, this question of vibes, similarity and fair use has only gotten more intense since the takedown of Neely's video. Just this week, the RIAA sued several AI companies, claiming that the songs the AI shits out are infringingly similar to tracks in their catalog:

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/record-labels-sue-music-generators-suno-and-udio-1235042056/

Even before "Blurred Lines," this was a difficult fair use question to answer, with lots of chewy nuances. Just ask George Harrison:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Sweet_Lord

But as the Engelberg panel's cohort of dueling musicologists and renowned copyright experts proved, this question only gets harder as time goes by. If you listen to that panel (if you can listen to that panel), you'll be hard pressed to come away with any certainty about the questions in this latest lawsuit.

The notice-and-takedown system is what's known as an "intermediary liability" rule. Platforms are "intermediaries" in that they connect end users with each other and with businesses. Ebay and Etsy and Amazon connect buyers and sellers; Facebook and Google and Tiktok connect performers, advertisers and publishers with audiences and so on.

For copyright, notice-and-takedown gives platforms a "safe harbor." A platform doesn't have to remove material after an allegation of infringement, but if they don't, they're jointly liable for any future judgment. In other words, Youtube isn't required to take down the Engelberg Blurred Lines panel, but if UMG sues Engelberg and wins a judgment, Google will also have to pay out.

During the adoption of the 1996 WIPO treaties and the 1998 US DMCA, this safe harbor rule was characterized as a balance between the rights of the public to publish online and the interest of rightsholders whose material might be infringed upon. The idea was that things that were likely to be infringing would be immediately removed once the platform received a notification, but that platforms would ignore spurious or obviously fraudulent takedowns.

That's not how it worked out. Whether it's Sony Music claiming to own your performance of "Fur Elise" or a war criminal claiming authorship over a newspaper story about his crimes, platforms nuke first and ask questions never. Why not? If they ignore a takedown and get it wrong, they suffer dire consequences ($150,000 per claim). But if they take action on a dodgy claim, there are no consequences. Of course they're just going to delete anything they're asked to delete.

This is how platforms always handle liability, and that's a lesson that we really should have internalized by now. After all, the DMCA is the second-most famous intermediary liability system for the internet – the most (in)famous is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

This is a 27-word law that says that platforms are not liable for civil damages arising from their users' speech. Now, this is a US law, and in the US, there aren't many civil damages from speech to begin with. The First Amendment makes it very hard to get a libel judgment, and even when these judgments are secured, damages are typically limited to "actual damages" – generally a low sum. Most of the worst online speech is actually not illegal: hate speech, misinformation and disinformation are all covered by the First Amendment.

Notwithstanding the First Amendment, there are categories of speech that US law criminalizes: actual threats of violence, criminal harassment, and committing certain kinds of legal, medical, election or financial fraud. These are all exempted from Section 230, which only provides immunity for civil suits, not criminal acts.

What Section 230 really protects platforms from is being named to unwinnable nuisance suits by unscrupulous parties who are betting that the platforms would rather remove legal speech that they object to than go to court. A generation of copyfraudsters have proved that this is a very safe bet:

https://www.techdirt.com/2020/06/23/hello-youve-been-referred-here-because-youre-wrong-about-section-230-communications-decency-act/

In other words, if you made a #MeToo accusation, or if you were a gig worker using an online forum to organize a union, or if you were blowing the whistle on your employer's toxic waste leaks, or if you were any other under-resourced person being bullied by a wealthy, powerful person or organization, that organization could shut you up by threatening to sue the platform that hosted your speech. The platform would immediately cave. But those same rich and powerful people would have access to the lawyers and back-channels that would prevent you from doing the same to them – that's why Sony can get your Brahms recital taken down, but you can't turn around and do the same to them.

This is true of every intermediary liability system, and it's been true since the earliest days of the internet, and it keeps getting proven to be true. Six years ago, Trump signed SESTA/FOSTA, a law that allowed platforms to be held civilly liable by survivors of sex trafficking. At the time, advocates claimed that this would only affect "sexual slavery" and would not impact consensual sex-work.

But from the start, and ever since, SESTA/FOSTA has primarily targeted consensual sex-work, to the immediate, lasting, and profound detriment of sex workers:

https://hackinghustling.org/what-is-sesta-fosta/

SESTA/FOSTA killed the "bad date" forums where sex workers circulated the details of violent and unstable clients, killed the online booking sites that allowed sex workers to screen their clients, and killed the payment processors that let sex workers avoid holding unsafe amounts of cash:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/09/fight-overturn-fosta-unconstitutional-internet-censorship-law-continues

SESTA/FOSTA made voluntary sex work more dangerous – and also made life harder for law enforcement efforts to target sex trafficking:

https://hackinghustling.org/erased-the-impact-of-fosta-sesta-2020/

Despite half a decade of SESTA/FOSTA, despite 15 years of filternets, despite a quarter century of notice-and-takedown, people continue to insist that getting rid of safe harbors will punish Big Tech and make life better for everyday internet users.

As of now, it seems likely that Section 230 will be dead by then end of 2025, even if there is nothing in place to replace it:

https://energycommerce.house.gov/posts/bipartisan-energy-and-commerce-leaders-announce-legislative-hearing-on-sunsetting-section-230

This isn't the win that some people think it is. By making platforms responsible for screening the content their users post, we create a system that only the largest tech monopolies can survive, and only then by removing or blocking anything that threatens or displeases the wealthy and powerful.

Filternets are not precision-guided takedown machines; they're indiscriminate cluster-bombs that destroy anything in the vicinity of illegal speech – including (and especially) the best-informed, most informative discussions of how these systems go wrong, and how that blocks the complaints of the powerless, the marginalized, and the abused.

Support me this summer on the Clarion Write-A-Thon and help raise money for the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/27/nuke-first/#ask-questions-never

Image: EFF https://www.eff.org/files/banner_library/yt-fu-1b.png

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#vibe rights#230#section 230#cda 230#communications decency act#communications decency act 230#cda230#filternet#copyfight#fair use#notice and takedown#censorship#reputation management#copyfraud#sesta#fosta#sesta fosta#spotify#youtube#contentid#monopoly#free speech#intermediary liability

677 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three days with the true believers who won’t let Bigfoot die

Yet another article about how crazy Bigfoot people are and can you believe what they believe. There are so many of this type of writing it is hard to keep track of them all.

From the article:

This story began with an unusually small flyer. If you’ve ever passed a village noticeboard littered with advertisements for local events, group meetings and tiny festivals, and wondered who attends these kinds of things, the answer is: my friend Peter. I admire this about him. It means that his life is full of unexpected encounters with interesting people in and around Eugene, Oregon, where he lives.

The flyer, which Peter spotted at a tourist office in the spring, was just three inches square and advertised an event being held over a long weekend in July in the town of Oakridge, a 45-minute drive south-east of Eugene, called Sasquatch Summer Fest. He took a picture and sent it to me.

I’d been looking for an excuse to visit him for a while, and this event struck me as weird in a fun way, but also surprising. Like everyone, I’ve heard of Bigfoot. Chewbacca-looking guy, very tall, lives in the forests of North America, not real. More of a mascot for the Pacific Northwest than anything else, or an old, tired joke. But what intrigued me most about this tiny flyer, and its associated website, was that it seemed serious. The main events of the weekend — in fact it appeared the only events of the weekend — would be talks by Bigfoot experts, discussing their research and screening their documentaries. It had the air of a conference, rather than a festival.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nintendo: We don't believe in fair use! Copyright is sacrosanct! Screw your fangame/emulator/youtube channel!

Also Nintendo:

King Kong, who's that?

#donkey kong#king kong#nintendo#copyright#fair use#copyleft#calling 'em as a I see 'em#kicking the ladder out from under themselves

131 notes

·

View notes