#Ludwig von 88

Text

ACIDE SEDATIF 4/5 [APR 1987]

French zine with articles about Garçons Bouchers / Pigalle / Los Carayos, Cabaret Voltaire, Ludwig von 88, Trodskids, Test Dept., Exploited, Swans, Die Kreuzen, GG Allin, Psychic TV, The Cramps, Sewer Zombies, Coil, Nightmare Culture, Reseau d'Ombres, Scream, Unity, Golgomax, and Fatal Impact.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

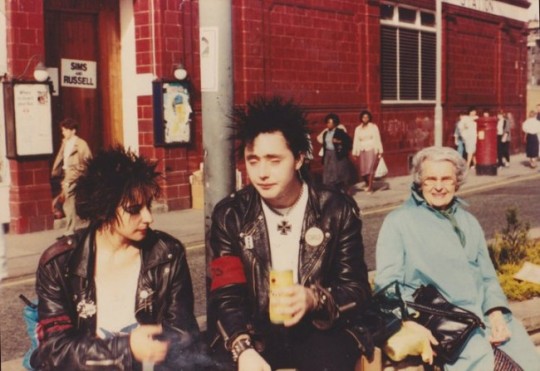

old portraits of 1980s french punk culture

while the movement may have originated in the uk and the us, the french punk scene emerged with a distinct flair and a powerful voice of its own. in the heart of this captivating subculture were iconic bands like bérurier noir, les cadavres, and ludwig von 88, whose raw and unapologetic music resonated with a generation yearning for change. the lyrics were fueled by social unrest, political disillusionment, and a profound desire to challenge the status quo. though decades have passed since the zenith of french punk, its legacy endures in the hearts of those who lived through it and in the passion of those who discovered it later.

#punk rock#nostalgia#80s#music#80s nostalgia#france#french rock#alternative#subcultures#alt subculture#punk#punk scene#punk culture#punk subculture#this is my first post so please be nice to me

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

I.1.1 Is socialism impossible?

In 1920, the right-wing economist Ludwig von Mises declared socialism to be impossible. A leading member of the “Austrian” school of economics, he argued this on the grounds that without private ownership of the means of production, there cannot be a competitive market for production goods and without a market for production goods, it is impossible to determine their values. Without knowing their values, economic rationality is impossible and so a socialist economy would simply be chaos: “the absurd output of a senseless apparatus.” For Mises, socialism meant central planning with the economy “subject to the control of a supreme authority.” [“Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth”, pp. 87–130, Collectivist Economic Planning, F.A von Hayek (ed.), p. 104 and p. 106] While applying his “economic calculation argument” to Marxist ideas of a future socialist society, his argument, it is claimed, is applicable to all schools of socialist thought, including libertarian ones. It is on the basis of his arguments that many right-wingers claim that libertarian (or any other kind of) socialism is impossible in principle.

Yet as David Schweickart observes ”[i]t has long been recognised that Mises’s argument is logically defective. Even without a market in production goods, their monetary values can be determined.” [Against Capitalism, p. 88] In other words, economic calculation based on prices is perfectly possible in a libertarian socialist system. After all, to build a workplace requires so many tonnes of steel, so many bricks, so many hours of work and so on. If we assume a mutualist society, then the prices of these goods can be easily found as the co-operatives in question would be offer their services on the market. These commodities would be the inputs for the construction of production goods and so the latter’s monetary values can be found.

Ironically enough, Mises did mention the idea of such a mutualist system in his initial essay. “Exchange relations between production-goods can only be established on the basis of private ownership of the means of production” he asserted. “When the ‘coal syndicate’ provides the ‘iron syndicate’ with coal, no price can be formed, except when both syndicates are the owners of the means of production employed in their business. This would not be socialisation but workers’ capitalism and syndicalism.” [Op. Cit., p. 112] However, his argument is flawed for numerous reasons.

First, and most obvious, socialisation (as we discuss in section I.3.3) simply means free access to the means of life. As long as those who join a workplace have the same rights and liberties as existing members then there is socialisation. A market system of co-operatives, in other words, is not capitalist as there is no wage labour involved as a new workers become full members of the syndicate, with the same rights and freedoms as existing members. Thus there are no hierarchical relationships between owners and wage slaves (even if these owners also happen to work there). As all workers’ control the means of production they use, it is not capitalism.

Second, nor is such a system usually called, as Mises suggests, “syndicalism” but rather mutualism and he obviously considered its most famous advocate, Proudhon and his “fantastic dreams” of a mutual bank, as a socialist. [Op. Cit., p. 88] Significantly, Mises subsequently admitted that it was “misleading” to call syndicalism workers’ capitalism, although “the workers are the owners of the means of production” it was “not genuine socialism, that is, centralised socialism”, as it “must withdraw productive goods from the market. Individual citizens must not dispose of the shares in the means of production which are allotted to them.” Syndicalism, i.e., having those who do the work control of it, was “the ideal of plundering hordes”! [Socialism, p. 274fn, p. 270, p. 273 and p. 275]

His followers, likewise, concluded that “syndicalism” was not capitalism with Hayek stating that there were “many types of socialism” including “communism, syndicalism, guild socialism”. Significantly, he indicated that Mises argument was aimed at systems based on the “central direction of all economic activity” and so “earlier systems of more decentralised socialism, like guild-socialism or syndicalism, need not concern us here since it seems now to be fairly generally admitted that they provide no mechanism whatever for a rational direction of economic activity.” [“The Nature and History of the Problem”, pp. 1–40, Collectivist Economic Planning, F.A von Hayek (ed.),p. 17, p. 36 and p. 19] Sadly he failed to indicate who “generally admitted” such a conclusion. More recently, Murray Rothbard urged the state to impose private shares onto the workers in the former Stalinist regimes of Eastern Europe as ownership was “not to be granted to collectives or co-operatives or workers or peasants holistically, which would only bring back the ills of socialism in a decentralised and chaotic syndicalist form.” [The Logic of Action II, p. 210]

Third, syndicalism usually refers to a strategy (revolutionary unionism) used to achieve (libertarian) socialism rather than the goal itself (as Mises himself noted in a tirade against unions, “Syndicalism is nothing else but the French word for trade unionism” [Socialism, p. 480]). It could be argued that such a mutualist system could be an aim for some syndicalists, although most were and still are in favour of libertarian communism (a simple fact apparently unknown to Mises). Indeed, Mises ignorance of syndicalist thought is striking, asserting that the “market is a consumers’ democracy. The syndicalists want to transform it into a producers’ democracy.” [Human Action, p. 809] Most syndicalists, however, aim to abolish the market and all aim for workers’ control of production to complement (not replace) consumer choice. Syndicalists, like other anarchists, do not aim for workers’ control of consumption as Mises asserts. Given that Mises asserts that the market, in which one person can have a thousand votes and another one, is a “democracy” his ignorance of syndicalist ideas is perhaps only one aspect of a general ignorance of reality.

More importantly, the whole premise of his critique of mutualism is flawed. “Exchange relations in productive goods” he asserted, “can only be established on the basis of private property in the means of production. If the Coal Syndicate delivers coal to the Iron Syndicate a price can be fixed only if both syndicates own the means of production in industry.” [Socialism, p. 132] This may come as a surprise to the many companies whose different workplaces sell each other their products! In other words, capitalism itself shows that workplaces owned by the same body (in this case, a large company) can exchange goods via the market. That Mises makes such a statement indicates well the firm basis of his argument in reality. Thus a socialist society can have extensive autonomy for its co-operatives, just as a large capitalist firm can:

“the entrepreneur is in a position to separate the calculation of each part of his total enterprise in such a way that he can determine the role it plays within his whole enterprise. Thus he can look at each section as if it were a separate entity and can appraise it according to the share it contributes to the success of the total enterprise. Within this system of business calculation each section of a firm represents an integral entity, a hypothetical independent business, as it were. It is assumed that this section ‘owns’ a definite part of the whole capital employed in the enterprise, that it buys from other sections and sells to them, that it has its own expenses and its own revenues, that its dealings result either in a profit or in a loss which is imputed to its own conduct of affairs as distinguished from the result of the other sections. Thus the entrepreneur can assign to each section’s management a great deal of independence … Every manager and submanager is responsible for the working of his section or subsection. It is to his credit if the accounts show a profit, and it is to his disadvantage if they show a loss. His own interests impel him toward the utmost care and exertion in the conduct of his section’s affairs.” [Human Action, pp. 301–2]

So much, then, for the notion that common ownership makes it impossible for market socialism to work. After all, the libertarian community can just as easily separate the calculation of each part of its enterprise in such a way as to determine the role each co-operative plays in its economy. It can look at each section as if it were a separate entity and appraise it according to the share it contributes as it is assumed that each section “owns” (i.e., has use rights over) its definite part. It can then buy from, and sell to, other co-operatives and a profit or loss can be imputed to evaluate the independent action of each co-operative and so their own interests impel the co-operative workers toward the utmost care and exertion in the conduct of their co-operative’s affairs.

So to refute Mises, we need only repeat what he himself argued about large corporations! Thus there can be extensive autonomy for workplaces under socialism and this does not in any way contradict the fact that “all the means of production are the property of the community.” [“Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth”, Op. Cit., p. 89] Socialisation, in other words, does not imply central planning but rather free access and free association. In summary, then, Mises confused property rights with use rights, possession with property, and failed to see now a mutualist system of socialised co-operatives exchanging products can be a viable alternative to the current exploitative and oppressive economic regime.

Such a mutualist economy also strikes at the heart of Mises’ claims that socialism was “impossible.” Given that he accepted that there may be markets, and hence market prices, for consumer goods in a socialist economy his claims of the impossibility of socialism seems unfounded. For Mises, the problem for socialism was that “because no production-good will ever become the object of exchange, it will be impossible to determine its monetary value.” [Op. Cit., p. 92] The flaw in his argument is clear. Taking, for example, coal, we find that it is both a means of production and of consumption. If a market in consumer goods is possible for a socialist system, then competitive prices for production goods is also possible as syndicates producing production-goods would also sell the product of their labour to other syndicates or communes. As Mises admitted when discussing one scheme of guild socialism, “associations and sub-associations maintain a mutual exchange-relationship; they receive and give as if they were owners. Thus a market and market-prices are formed.” Thus, when deciding upon a new workplace, railway or house, the designers in question do have access to competitive prices with which to make their decisions. Nor does Mises’ argument work against communal ownership in such a system as the commune would be buying products from syndicates in the same way as one part of a company can buy products from another part of the same company under capitalism. That goods produced by self-managed syndicates have market-prices does not imply capitalism for, as they abolish wage labour and are based on free-access (socialisation), it is a form of socialism (as socialists define it, Mises’ protestations that “this is incompatible with socialism” not-with-standing!). [Socialism, p. 518]

Murray Rothbard suggested that a self-managed system would fail, and a system “composed exclusively of self-managed enterprises is impossible, and would lead … to calculative chaos and complete breakdown.” When “each firm is owned jointly by all factor-owners” then “there is no separation at all between workers, landowners, capitalists, and entrepreneurs. There would be no way, then, of separating the wage incomes received from the interest or rent incomes or profits received. And now we finally arrive at the real reason why the economy cannot consist completely of such firms (called ‘producers’ co-operatives’). For, without an external market for wage rates, rents, and interest, there would be no rational way for entrepreneurs to allocate factors in accordance with the wishes of the consumers. No one would know where he could allocate his land or his labour to provide the maximum monetary gains. No entrepreneur would know how to arrange factors in their most value-productive combination to earn greatest profit. There could be no efficiency in production because the requisite knowledge would be lacking.” [quoted by David L. Prychitko, Markets, Planning and Democracy, p. 135 and p. 136]

It is hard to take this argument seriously. Consider, for example, a pre-capitalist society of farmers and artisans. Both groups of people own their own means of production (the land and the tools they use). The farmers grow crops for the artisans who, in turn, provide the farmers with the tools they use. According to Rothbard, the farmers would have no idea what to grow nor would the artisans know which tools to buy to meet the demand of the farmers nor which to use to reduce their working time. Presumably, both the farmers and artisans would stay awake at night worrying what to produce, wishing they had a landlord and boss to tell them how best to use their labour and resources.

Let us add the landlord class to this society. Now the landlord can tell the farmer what to grow as their rent income indicates how to allocate the land to its most productive use. Except, of course, it is still the farmers who decide what to produce. Knowing that they will need to pay rent (for access to the land) they will decide to devote their (rented) land to the most profitable use in order to both pay the rent and have enough to live on. Why they do not seek the most profitable use without the need for rent is not explored by Rothbard. Much the same can be said of artisans subject to a boss, for the worker can evaluate whether an investment in a specific new tool will result in more income or reduced time labouring or whether a new product will likely meet the needs of consumers. Moving from a pre-capitalist society to a post-capitalist one, it is clear that a system of self-managed co-operatives can make the same decisions without requiring economic masters. This is unsurprising, given that Mises’ asserted that the boss “of course exercises power over the workers” but that the “lord of production is the consumer.” [Socialism, p. 443] In which case, the boss need not be an intermediary between the real “lord” and those who do the production!

All in all, Rothbard confirms Kropotkin’s comments that economics (“that pseudo-science of the bourgeoisie”) “does not cease to give praise in every way to the benefits of individual property” yet “the economists do not conclude, ‘The land to him who cultivates it.’ On the contrary, they hasten to deduce from the situation, ‘The land to the lord who will get it cultivated by wage earners!’” [Words of a Rebel, pp. 209–10] In addition, Rothbard implicitly places “efficiency” above liberty, preferring dubious “efficiency” gains to the actual gains in freedom which the abolition of workplace autocracy would create. Given a choice between liberty and “efficiency”, the genuine anarchist would prefer liberty. Luckily, though, workplace liberty increases efficiency so Rothbard’s decision is a wrong one. It should also be noted that Rothbard’s position (as is usually the case) is directly opposite that of Proudhon, who considered it “inevitable” that in a free society “the two functions of wage-labourer on the one hand, and of proprietor-capitalist-contractor on the other, become equal and inseparable in the person of every workingman”. This was the “first principle of the new economy, a principle full of hope and of consolation for the labourer without capital, but a principle full of terror for the parasite and for the tools of parasitism, who see reduced to naught their celebrated formula: Capital, labour, talent!” [Proudhon’s Solution of the Social Problem, p. 165 and p. 85]

And it does seem a strange co-incidence that someone born into a capitalist economy, ideologically supporting it with a passion and seeking to justify its class system just happens to deduce from a given set of axioms that landlords and capitalists happen to play a vital role in the economy! It would not take too much time to determine if someone in a society without landlords or capitalists would also logically deduce from the same axioms the pressing economic necessity for such classes. Nor would it take long to ponder why Greek philosophers, like Aristotle, concluded that slavery was natural. And it does seem strange that centuries of coercion, authority, statism, classes and hierarchies all had absolutely no impact on how society evolved, as the end product of real history (the capitalist economy) just happens to be the same as Rothbard’s deductions from a few assumptions predict. Little wonder, then, that “Austrian” economics seems more like rationalisations for some ideologically desired result than a serious economic analysis.

Even some dissident “Austrian” economists recognise the weakness of Rothbard’s position. Thus “Rothbard clearly misunderstands the general principle behind producer co-operatives and self-management in general.” In reality, ”[a]s a democratic method of enterprise organisation, workers’ self-management is, in principle, fully compatible with a market system” and so “a market economy comprised of self-managed enterprises is consistent with Austrian School theory … It is fundamentally a market-based system … that doesn’t seem to face the epistemological hurdles … that prohibit rational economic calculation” under state socialism. Sadly, socialism is still equated with central planning, for such a system “is certainly not socialism. Nor, however, is it capitalism in the conventional sense of the term.” In fact, it is not capitalism at all and if we assume that free access to resources such as workplaces and credit, then it most definitely is socialism (“Legal ownership is not the chief issue in defining workers’ self-management — management is. Worker-managers, though not necessarily the legal owners of all the factors of production collected within the firm, are free to experiment and establish enterprise policy as they see fit.”). [David L. Prychitko, Op. Cit., p. 136, p. 135, pp. 4–5, p. 4 and p. 135] This suggests that non-labour factors can be purchased from other co-operatives, credit provided by mutual banks (credit co-operatives) at cost and so forth. As such, a mutualist system is perfectly feasible.

Thus economic calculation based on competitive market prices is possible under a socialist system. Indeed, we see examples of this even under capitalism. For example, the Mondragon co-operative complex in the Basque Country indicate that a libertarian socialist economy can exist and flourish. Perhaps it will be suggested that an economy needs stock markets to price companies, as Mises did. Thus investment is “not a matter for the mangers of joint stock companies, it is essentially a matter of the capitalists” in the “stock exchanges”. Investment, he asserted, was “not a matter of wages” of managers but of “the capitalist who buys and sell stocks and shares, who make loans and recover them, who make deposits in the banks.” [Socialism, p. 139]

It would be churlish to note that the members of co-operatives under capitalism, like most working class people, are more than able to make deposits in banks and arrange loans. In a mutualist economy, workers will not loose this ability just because the banks are themselves co-operatives. Similarly, it would be equally churlish but essential to note that the stock market is hardly the means by which capital is actually raised within capitalism. As David Engler points out, ”[s]upporters of the system … claim that stock exchanges mobilise funds for business. Do they? When people buy and sell shares, ‘no investment goes into company treasuries … Shares simply change hands for cash in endless repetition.’ Company treasuries get funds only from new equity issues. These accounted for an average of a mere 0.5 per cent of shares trading in the US during the 1980s.” [Apostles of Greed, pp. 157–158] This is echoed by David Ellerman:

“In spite of the stock market’s large symbolic value, it is notorious that it has relatively little to do with the production of goods and services in the economy (the gambling industry aside). The overwhelming bulk of stock transactions are in second-hand shares so that the capital paid for shares usually goes to other stock traders, not to productive enterprises issuing new shares.” [The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm, p. 199]

This suggests that the “efficient allocation of capital in production does not require a stock market (witness the small business sector [under capitalism]).” “Socialist firms,” he notes, “are routinely attacked as being inherently inefficient because they have no equity shares exposed to market valuation. If this argument had any merit, it would imply that the whole sector of unquoted closely-held small and medium-sized firms in the West was ‘inherently inefficient’ — a conclusion that must be viewed with some scepticism. Indeed, in the comparison to large corporations with publicly-traded shares, the closely-held firms are probably more efficient users of capital.” [Op. Cit., p. 200 and p. 199]

In terms of the impact of the stock market on the economy there is good reason to think that this hinders economic efficiency by generating a perverse set of incentives and misleading information flows and so their abolition would actually aid production and productive efficiency).

Taking the first issue, the existence of a stock market has serious (negative) effects on investment. As Doug Henwood notes, there “are serious communication problems between managers and shareholders.” This is because ”[e]ven if participants are aware of an upward bias to earnings estimates [of companies], and even if they correct for it, managers would still have an incentive to try to fool the market. If you tell the truth, your accurate estimate will be marked down by a sceptical market. So, it’s entirely rational for managers to boost profits in the short term, either through accounting gimmickry or by making only investments with quick paybacks.” So, managers “facing a market [the stock market] that is famous for its preference for quick profits today rather than patient long-term growth have little choice but to do its bidding. Otherwise, their stock will be marked down, and the firm ripe for take-over.” While ”[f]irms and economies can’t get richer by starving themselves” stock market investors “can get richer when the companies they own go hungry — at least in the short term. As for the long term, well, that’s someone else’s problem the week after next.” [Wall Street, p. 171]

Ironically, this situation has a parallel with Stalinist central planning. Under that system the managers of State workplaces had an incentive to lie about their capacity to the planning bureaucracy. The planner would, in turn, assume higher capacity, so harming honest managers and encouraging them to lie. This, of course, had a seriously bad impact on the economy. Unsurprisingly, the similar effects caused by capital markets on economies subject to them are as bad as well as downplaying long term issues and investment. In addition, it should be noted that stock-markets regularly experiences bubbles and subsequent bursts. Stock markets may reflect the collective judgements of investors, but it says little about the quality of those judgements. What use are stock prices if they simply reflect herd mentality, the delusions of people ignorant of the real economy or who fail to see a bubble? Particularly when the real-world impact when such bubbles burst can be devastating to those uninvolved with the stock market?

In summary, then, firms are “over-whelmingly self-financing — that is, most of their investment expenditures are funded through profits (about 90%, on longer-term averages)” The stock markets provide “only a sliver of investment funds.” There are, of course, some “periods like the 1990s, during which the stock market serves as a conduit for shovelling huge amounts of cash into speculative venues, most of which have evaporated … Much, maybe most, of what was financed in the 1990s didn’t deserve the money.” Such booms do not last forever and are “no advertisement for the efficiency of our capital markets.” [Henwood, After the New Economy, p. 187 and p. 188]

Thus there is substantial reason to question the suggestion that a stock market is necessary for the efficient allocation of capital. There is no need for capital markets in a system based on mutual banks and networks of co-operatives. As Henwood concludes, “the signals emitted by the stock market are either irrelevant or harmful to real economic activity, and that the stock market itself counts little or nothing as a source of finance. Shareholders … have no useful role.” [Wall Street, p. 292]

Then there is also the ironic nature of Rothbard’s assertion that self-management would ensure there “could be no efficiency in production because the requisite knowledge would be lacking.” This is because capitalist firms are hierarchies, based on top-down central planning, and this hinders the free flow of knowledge and information. As with Stalinism, within the capitalist firm information passes up the organisational hierarchy and becomes increasingly simplified and important local knowledge and details lost (when not deliberately falsified to ensure continual employment by suppressing bad news). The top-management takes decisions based on highly aggregated data, the quality of which is hard to know. The management, then, suffers from information and knowledge deficiencies while the workers below lack sufficient autonomy to act to correct inefficiencies as well as incentive to communicate accurate information and act to improve the production process. As Cornelius Castoriadis correctly noted:

“Bureaucratic planning is nothing but the extension to the economy as a whole of the methods created and applied by capitalism in the ‘rational’ direction of large production units. If we consider the most profound feature of the economy, the concrete situation in which people are placed, we see that bureaucratic planning is the most highly perfected realisation of the spirit of capitalism; it pushes to the limit its most significant tendencies. Just as in the management of a large capitalist production unit, this type of planning is carried out by a separate stratum of managers … Its essence, like that of capitalist production, lies in an effort to reduce the direct producers to the role of pure and simple executants of received orders, orders formulated by a particular stratum that pursues its own interests. This stratum cannot run things well, just as the management apparatus … [in capitalist] factories cannot run things well. The myth of capitalism’s productive efficiency at the level of the individual factory, a myth shared by bourgeois and Stalinist ideologues alike, cannot stand up to the most elemental examination of the facts, and any industrial worker could draw up a devastating indictment against capitalist ‘rationalisation’ judged on its own terms.

“First of all, the managerial bureaucracy does not know what it is supposed to be managing. The reality of production escapes it, for this reality is nothing but the activity of the producers, and the producers do not inform the managers … about what is really taking place. Quite often they organise themselves in such a way that the managers won’t be informed (in order to avoid increased exploitation, because they feel antagonistic, or quite simply because they have no interest: It isn’t their business).

“In the second place, the way in which production is organised is set up entirely against the workers. They always are being asked, one way or another, to do more work without getting paid for it. Management’s orders, therefore, inevitably meet with fierce resistance on the part of those who have to carry them out.” [Political and Social Writings, vol. 2, pp. 62–3]

This is “the same objection as that Hayek raises against the possibility of a planned economy. Indeed, the epistemological problems that Hayek raised against centralised planned economies have been echoed within the socialist tradition as a problem within the capitalist firm.” There is “a real conflict within the firm that parallels that which Hayek makes about any centralised economy.” [John O’Neill, The Market, p. 142] This is because workers have knowledge about their work and workplace that their bosses lack and a self-managed co-operative workplace would motivate workers to use such information to improve the firm’s performance. In a capitalist workplace, as in a Stalinist economy, the workers have no incentive to communicate this information as “improvements in the organisation and methods of production initiated by workers essentially profit capital, which often then seizes hold of them and turns them against the workers. The workers know it and consequently they restrict their participation in production … They restrict their output; they keep their ideas to themselves . .. They organise among themselves to carry out their work, all the while keeping up a facade of respect for the official way they are supposed to organise their work.” [Castoriadis, Op. Cit., pp. 181–2] An obvious example would be concerns that management would seek to monopolise the workers’ knowledge in order to accumulate more profits, better control the workforce or replace them (using the higher productivity as an excuse). Thus self-management rather than hierarchy enhances the flow and use of information in complex organisations and so improves efficiency.

This conclusion, it should be stressed, is not idle speculation and that Mises was utterly wrong in his assertions related to self-management. People, he stated, “err” in thinking that profit-sharing “would spur the worker on to a more zealous fulfilment of his duties” (indeed, it “must lead straight to Syndicalism”) and it was “nonsensical to give ‘labour’ … a share in management. The realisation of such a postulate would result in syndicalism.” [Socialism, p. 268, p. 269 and p. 305] Yet, as we note in section I.3.2, the empirical evidence is overwhelmingly against Mises (which suggests why “Austrians” are so dismissive of empirical evidence, as it exposes flaws in the great chains of deductive reasoning they so love). In fact, workers’ participation in management and profit sharing enhance productivity. In one sense, though, Mises is right, in that capitalist firms will tend not to encourage participation or even profit sharing as it shows to workers the awkward fact that while the bosses may need them, they do not need the bosses. As discussed in section J.5.12, bosses are fearful that such schemes will lead to “syndicalism” and so quickly stop them in order to remain in power — in spite (or, more accurately, because) of the efficiency and productivity gains they result in.

“Both capitalism and state socialism,” summarises Ellerman, “suffer from the motivational inefficiency of the employment relation.” Op. Cit., pp. 210–1] Mutualism would be more efficient as well as freer for, once the stock market and workplace hierarchies are removed, serious blocks and distortions to information flow will be eliminated.

Unfortunately, the state socialists who replied to Mises in the 1920s and 1930s did not have such a libertarian economy in mind. In response to Mises initial challenge, a number of economists pointed out that Pareto’s disciple, Enrico Barone, had already, 13 years earlier, demonstrated the theoretical possibility of a “market-simulated socialism.” However, the principal attack on Mises’s argument came from Fred Taylor and Oscar Lange (for a collection of their main papers, see On the Economic Theory of Socialism). In light of their work, Hayek shifted the question from theoretical impossibility to whether the theoretical solution could be approximated in practice. Which raises an interesting question, for if (state) socialism is “impossible” (as Mises assured us) then what did collapse in Eastern Europe? If the “Austrians” claim it was “socialism” then they are in the somewhat awkward position that something they assure us is “impossible” existed for decades. Moreover, it should be noted that both sides of the argument accepted the idea of central planning of some kind or another. This means that most of the arguments of Mises and Hayek did not apply to libertarian socialism, which rejects central planning along with every other form of centralisation.

Nor was the response by Taylor and Lange particularly convincing in the first place. This was because it was based far more on neo-classical capitalist economic theory than on an appreciation of reality. In place of the Walrasian “Auctioneer” (the “god in the machine” of general equilibrium theory which ensures that all markets clear) Taylor and Lange presented the “Central Planning Board” whose job it was to adjust prices so that all markets cleared. Neo-classical economists who are inclined to accept Walrasian theory as an adequate account of a working capitalist economy will be forced to accept the validity of their model of “socialism.” Little wonder Taylor and Lange were considered, at the time, the victors in the “socialist calculation” debate by most of the economics profession (with the collapse of the Soviet Union, this decision has been revised somewhat — although we must point out that Taylor and Lange’s model was not the same as the Soviet system, a fact conveniently ignored by commentators).

Unfortunately, given that Walrasian theory has little bearing to reality, we must also come to the conclusion that the Taylor-Lange “solution” has about the same relevance (even ignoring its non-libertarian aspects, such as its basis in state-ownership, its centralisation, its lack of workers’ self-management and so on). Many people consider Taylor and Lange as fore-runners of “market socialism.” This is incorrect — rather than being market socialists, they are in fact “neo-classical” socialists, building a “socialist” system which mimics capitalist economic theory rather than its reality. Replacing Walrus’s mythical creation of the “Auctioneer” with a planning board does not really get to the heart of the problem! Nor does their vision of “socialism” have much appeal — a re-production of capitalism with a planning board and a more equal distribution of money income. Anarchists reject such “socialism” as little more than a nicer version of capitalism, if that.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has been fashionable to assert that “Mises was right” and that socialism is impossible (of course, during the cold war such claims were ignored as the Soviet threat had to boosted and used as a means of social control and to justify state aid to capitalist industry). Nothing could be further from the truth as these countries were not socialist at all and did not even approximate the (libertarian) socialist idea (the only true form of socialism). The Stalinist countries had authoritarian “command economies” with bureaucratic central planning, and so their failure cannot be taken as proof that a decentralised, libertarian socialism cannot work. Nor can Mises’ and Hayek’s arguments against Taylor and Lange be used against a libertarian mutualist or collectivist system as such a system is decentralised and dynamic (unlike the “neo-classical” socialist model). Libertarian socialism of this kind did, in fact, work remarkably well during the Spanish Revolution in the face of amazing difficulties, with increased productivity and output in many workplaces as well as increased equality and liberty (see section I.8).

Thus the “calculation argument” does not prove that socialism is impossible. Mises was wrong in asserting that “a socialist system with a market and market prices is as self-contradictory as is the notion of a triangular square.” [Human Action, p. 706] This is because capitalism is not defined by markets as such but rather by wage labour, a situation where working class people do not have free access to the means of production and so have to sell their labour (and so liberty) to those who do. If quoting Engels is not too out of place, the “object of production — to produce commodities — does not import to the instrument the character of capital” as the “production of commodities is one of the preconditions for the existence of capital .. . as long as the producer sells only what he himself produces, he is not a capitalist; he becomes so only from the moment he makes use of his instrument to exploit the wage labour of others.” [Collected Works, Vol. 47, pp. 179–80] In this, as noted in section C.2.1, Engels was merely echoing Marx (who, in turn, was simply repeating Proudhon’s distinction between property and possession). As mutualism eliminates wage labour by self-management and free access to the means of production, its use of markets and prices (both of which pre-date capitalism) does not mean it is not socialist (and as we note in section G.1.1 Marx, Engels, Bakunin and Kropotkin, like Mises, acknowledged Proudhon as being a socialist). This focus on the market, as David Schweickart suggests, is no accident:

“The identification of capitalism with the market is a pernicious error of both conservative defenders of laissez-faire [capitalism] and most left opponents … If one looks at the works of the major apologists for capitalism … one finds the focus of the apology always on the virtues of the market and on the vices of central planning. Rhetorically this is an effective strategy, for it is much easier to defend the market than to defend the other two defining institutions of capitalism. Proponents of capitalism know well that it is better to keep attention toward the market and away from wage labour or private ownership of the means of production.” [“Market Socialism: A Defense”, pp. 7–22, Market Socialism: the debate among socialists, Bertell Ollman (ed.), p. 11]

The theoretical work of such socialists as David Schweickart (see his books Against Capitalism and After Capitalism) present an extensive discussion of a dynamic, decentralised market socialist system which has obvious similarities with mutualism — a link which some Leninists recognise and stress in order to discredit market socialism via guilt-by-association (Proudhon “the anarchist and inveterate foe of Karl Marx … put forward a conception of society, which is probably the first detailed exposition of a ‘socialist market.’” [Hillel Ticktin, “The Problem is Market Socialism”, pp. 55–80, Op. Cit., p. 56]). So far, most models of market socialism have not been fully libertarian, but instead involve the idea of workers’ control within a framework of state ownership of capital (Engler in Apostles of Greed is an exception to this, supporting community ownership). Ironically, while these Leninists reject the idea of market socialism as contradictory and, basically, not socialist they usually acknowledge that the transition to Marxist-communism under their workers’ state would utilise the market.

So, as anarchist Robert Graham points out, “Market socialism is but one of the ideas defended by Proudhon which is both timely and controversial … Proudhon’s market socialism is indissolubly linked with his notions of industrial democracy and workers’ self-management.” [“Introduction”, P-J Proudhon, General Idea of the Revolution, p. xxxii] As we discuss in section I.3.5 Proudhon’s system of agro-industrial federations can be seen as a non-statist way of protecting self-management, liberty and equality in the face of market forces (Proudhon, unlike individualist anarchists, was well aware of the negative aspects of markets and the way market forces can disrupt society). Dissident economist Geoffrey M. Hodgson is right to suggest that Proudhon’s system, in which “each co-operative association would be able to enter into contractual relations with others”, could be “described as an early form of ‘market socialism’”. In fact, “instead of Lange-type models, the term ‘market socialism’ is more appropriately to such systems. Market socialism, in this more appropriate and meaningful sense, involves producer co-operatives that are owned by the workers within them. Such co-operatives sell their products on markets, with genuine exchanges of property rights” (somewhat annoyingly, Hodgson incorrectly asserts that “Proudhon described himself as an anarchist, not a socialist” when, in reality, the French anarchist repeatedly referred to himself and his mutualist system as socialist). [Economics and Utopia, p. 20, p. 37 and p. 20]

Thus it is possible for a socialist economy to allocate resources using markets. By suppressing capital markets and workplace hierarchies, a mutualist system will improve upon capitalism by removing an important source of perverse incentives which hinder efficient use of resources as well as long term investment and social responsibility in addition to reducing inequalities and increasing freedom. As David Ellerman once noted, many “still look at the world in bipolar terms: capitalism or (state) socialism.” Yet there “are two broad traditions of socialism: state socialism and self-management socialism. State socialism is based on government ownership of major industry, while self-management socialism envisions firms being worker self-managed and not owned or managed by the government.” [Op. Cit., p. 147] Mutualism is a version of the second vision and anarchists reject the cosy agreement between mainstream Marxists and their ideological opponents on the propertarian right that only state socialism is “real” socialism.

Finally, it should be noted that most anarchists are not mutualists but rather aim for (libertarian) communism, the abolition of money. Many do see a mutualist-like system as an inevitable stage in a social revolution, the transitional form imposed by the objective conditions facing a transformation of a society marked by thousands of years of oppression and exploitation (collectivist-anarchism contains elements of both mutualism and communism, with most of its supporters seeing it as a transitional system). This is discussed in section I.2.2, while section I.1.3 indicates why most anarchists reject even non-capitalist markets. So does Mises’s argument mean that a socialism that abolishes the market (such as libertarian communism) is impossible? Given that the vast majority of anarchists seek a libertarian communist society, this is an important question. We address it in the next section.

#anarchist society#practical#practical anarchism#practical anarchy#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Donald trump should have seen it coming. He arrived on May 25th at the Libertarian Party’s national convention in Washington, DC, hoping to expand his support, but the crowd mostly responded with boos. Attendees lacked enthusiasm for a protectionist who added $8.4trn to America’s national debt. They also spent the weekend squabbling among themselves. After losing presidential races for more than half a century, the Libertarian Party is facing an identity crisis.

(…)

The most intense divisions are about strategy. The hardline Mises Caucus (named after Ludwig von Mises, a pro-market Austrian economist) has dominated the party’s leadership since 2022 and adopted populist rhetoric. The group was responsible for inviting Mr Trump, as well as Robert F. Kennedy junior, an independent candidate, to speak at the convention. The debate about whether to invite the outside candidates at times seemed more heated than the Libertarians’ own presidential-nomination fight. On May 24th, the convention’s first day, one attendee yelled into the microphone, “I would like to propose that we go tell Donald Trump to go fuck himself!” The crowd cheered.

“I would rather us focus on the Libertarian candidates,” said Jim Fulner, from the Radical Caucus. “I’m fearful that come later this summer, when I’m working the county fair, someone will say, ‘Oh, Libertarians, you guys are the Donald Trump people.’” Nick Apostolopoulos, from California, welcomed the attention Mr Trump’s speech brought—and said his presence proved “this party matters, and that they have to try and appeal to this voting bloc.”

Few believed that Mr Trump won much support. He promised to appoint a Libertarian to his cabinet and commute the sentence of Ross Ulbricht, who is serving life in prison after founding the dark-web equivalent of Amazon for illegal drugs. The crowd responded positively to Mr Trump’s nod to a Libertarian cause célèbre, but booed after he asked them to choose him as the Libertarian Party’s presidential nominee. Mr Trump hit back, “If you want to lose, don’t do that. Keep getting your 3% every four years.”

Mr Kennedy was more disciplined, tailoring his speech to the crowd by highlighting his opposition to covid lockdowns. Even so he received a cool reception. Libertarians want a candidate who will promise to abolish, not reform, government agencies.

The reality is that Libertarians are more interested in positions than personalities. The exception may be the broad admiration for Ron Paul, a retired Republican congressman whom many cite as their lodestar. But at 88 Mr Paul has achieved the difficult feat of being considered too old to plausibly run for president.

(…)

But the party is far from unified. Given the choice between Mr Oliver and “none of the above”, more than a third of the delegates preferred no one. It remains uncertain whether the party’s candidate will appear on the ballot in all 50 states, as several previous nominees have. If the Libertarian candidate has any influence on the presidential election this year, it will be as a spoiler in a close-run swing state.

Mr Oliver’s victory marked a rare defeat for the Mises Caucus. But the re-election of Angela McArdle, a Mises Caucus member, as the national party chairperson is perhaps more important to the future of the movement. Ms McArdle faced criticism for her decision to invite outside candidates to speak. Controversy over the Mises Caucus had led several state delegations to split, and much of the convention’s floor time was eaten up over fights about whom to recognise. The rise of the Mises wing of the party has led more pragmatically minded members to largely give up on the project of advancing libertarian ideas by building a political party.

The party struggles on big stages, such as in presidential, gubernatorial or Senate contests. Yet it occasionally wins municipal elections, leaving some to wonder whether national activism is pointless or even counter-productive. Why would Libertarians invest time in a hopeless race for president when they could direct their energy to fighting a local sales tax or antiquated laws restricting alcohol sales?

(…)

The party faithful believe that national and local activism are not mutually exclusive. Elijah Gizzarelli won fewer than 3,000 votes when he ran for governor of Rhode Island as a Libertarian two years ago, but he argues that the party has a long record of success—so long as the definition of success expands beyond winning elections. He says the party succeeds by shifting the “Overton window”, or the spectrum of political ideas that are generally considered acceptable.”

#libertarian#libertarianism#liberty#mises#caucus#party#president#election#trump#robert kennedy jr#austrian economics#ayn rand#objectivism#become ungovernable#ron paul#overton window

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mies van der Rohe - Wohnungsbau Afrikanische Straße Berlin Wedding 1926-27

Architekt: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Nutzung: Wohnanlage mit 88 Wohnungen

Entwurf: 1925

Bauzeit: 1926-27

Ausführung: Bauhütte Berlin GmbH (Baufirma)

Bauherr: Heimstättengesellschaft "Primus" GmbH

Fotos Zustand Juni 2023

Mies van der Rohes einziger sozialer Wohnungsbau in Berlin

Diese Wohnanlage mit ihren kubisch, blockhaften Häusern mit Flachdach geht in Mies’ Werk leider etwas unter, ist aber um so wichtiger, als dass er sich hier mit einer der zentralsten Fragen der 20er Jahre das letzten Jahrhunderts (und eigentlich auch einer der wichtigsten Fragen unserer Zeit), dem bezahlbaren Wohnraum, auseinandergesetzt hat.

Die Wohnanlage besteht aus 88 Wohnungen mit ein bis drei Zimmerwohnungen mit geräumigen Wohnküchen.

Städtebauliche Besonderheit

Mies belässt es nicht bei reinen Zeilenbauten sondern ergänzt die langen Zeilen an der Afrikansichen Straße mit kurzen, um (fast) 90 Grad versetzten zusätzlichen Blöcken, die die Seitenstraßen begleiten. Somit entstehen angedeutete Blockstrukturen, welche Mies subtile Arte der städtebaulichen Einbindung seiner Bauten bezeugen.

Die komplette Wohnanlage wurde etwas von der Afrikanischen Straße zurückversetzt geplant, um eine schmale vorgelagerte Grünzone auszubilden. Ursprünglich war der Grünstreifen mit Säulenpappeln bepflanzt, was der Anlage etwas die Härte nahm und eine formal elegante Übergangszone zwischen Straße und Gebäude ausbildete.

idealisierter Grundriss

#mies van der rohe#berlin#bauhaus#architektur#architecture#city planning#urbanism#wedding#modern architecture

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making progress!

Trouser's writings :

- On the left pocket, a skull with three eyes shaped like Breton hermines + plus three spot ("mort aux vaches" = acab) and written around the pocket "hippobroma longiflora", the white flower I tried to paint. One of its verbacular name is "mort aux vaches". The yellow flower are ranunculus sceleratus.

- Under it "Nazi punks fuck off"

- Bands names : Ludwig von 88, The Hu, Tagada Jones

- On the calf : "less rapes more thefts"

- The other pocket is the Ramoneurs de Menhirs punk band's logo, under it A Tribe Called Red

- Under it, an unofficial Breton anarchist/antifa flag

- Barbie. In pink and with glitters with a (failed) attempt at a metal font

- Under it band name Les Sales Majestés

- I plan to add more but I'm waiting for it to dry out first

Jacket's new writings :

- On the left side, the anarchafeminist flag

- Still "antivaxx = eugenism"

- On the right side, an attempt to make a tit with an hermine instead of the areola (I do love hermines, in case you haven't noticed. You can't be a proper asshole if you don't put it everywhere)

- Under it a red hand with MMIW written under

- Under it "I 💜 abortions" (how muvh time before I'm called something misogynistic in the streets, you think?)

- Right arm, a bloodied uterus giving the fly (a radfem symbol to signal to other radfems), the blood comes out as a reversed hermine. Under it is written "Stop menstrual poverty" (plus the end of menstruel, "elle", meaning "she", underlined). Call it cryptofem starting gear.

- Under it two purple female symbol intertwined

+ Various red spots reminding blood

I intend to add way more stuff. I just don't have the courage to tackle it tonight, especially since there are some complex paintings I plan. Also, bonus thay happened as I wrote all this :

Like, ily baby, but I really hope it dried before you decided to nap there 😭😭😭😭

1 note

·

View note

Text

Le Moloco d'Audincourt annonce sa première partie des concerts de la saison 2024-2025

Le Moloco d'Audincourt annonce sa première partie des concerts pour la saison 2024-2025 :

Nocturne Étudiante 2024 – le Ven. 11 Oct. au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 21h00

Tarifs : Sur place : 13€ / Prévente : 10€ / Gratuit carte Avantages Jeunes (dans la limite des places disponibles sur présentation de la carte) / Abonnés Moloco-Poudrière : 7€ / Enfants -10 ans : 5€

Comme chaque année, le Moloco accueille la Nocturne Étudiante du Pays de Montbéliard. Après un parcours de découverte des lieux culturels de la Cité des Princes, les étudiants pourront se rendre à Audincourt à partir de 21h, jusqu'à 2h du matin, pour une soirée majoritairement rap.

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

8RUKI : mots après mots, phrases après phrases, il continue de prendre sa place dans le monde du rap français : celle d’un artiste aussi inclassable que fidèle à ses sens. Du rap à la plug, du boom-bap à la trap, des sonorités afros aux mélodies chantées, la musique de ce natif de la région parisienne ne cesse d’aller explorer les genres, sans se soucier des barrières ou des étiquettes qu’on pourrait coller à sa musique.

SLIMKA : véritable phénomène sur scène, il revient avec une nouvelle tournée (sans playback) à travers la France. Le Boryngo est prêt à envoûter les foules !

ZONMAI : artiste française de 22 ans, elle ne s’interdit rien et déploie toujours son imaginaire coûte que coûte. Sa musique n’est pas seulement le fruit de son amour pour le rap et ses dérivés, mais aussi celui d’une imagination singulière, faussement naïve.

RSKO (French Rap) – Ven. 12 Oct. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h30

Sur place : 25€ / Prévente : 22€ / Sur place (tarif réduit) : 22€ / Prévente (tarif réduit) : 20€ / Abonnés Moloco-Poudrière : 18€ / Enfants -10 ans : 5€

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

Après une première partie de tournée et un concert à La Cigale complet en 24 heures, RSKO rajoute de nouvelles dates à sa tournée qui se prolonge cet automne et se clôturera en beauté le 19 novembre à L’Olympia à Paris.

Véritable succès, son premier album « LMBD » est désormais disque d’or et a fait exploser sa côte de popularité. À mi-chemin du disque d’or et écoulé à 25.000 exemplaires, son deuxième album « MEM( )RY » paru le 3 novembre 2023 a définitivement toutes les qualités pour succéder dignement au premier. À découvrir sur scène de toute urgence !

AYO (Soul Folk) – Ven. 18 Oct. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h30

Plein tarif : 25€ / Tarif réduit (étudiants, demandeurs d’emploi, bénéficiaires du RSA, carte Avantages Jeunes, etc.) : 22€ / Abonnés Moloco-Poudrière : 18€ / Enfants -10 ans : 5€

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

Chanteuse, compositrice et interprète, Ayo est une artiste rare dont la voix suave et puissante vous transporte dès les premières notes. Née d’un père nigérian et d’une mère allemande, elle puise ses racines dans la soul, le folk et le reggae pour créer une musique unique et vibrante.

Révélée en 2006 par son album « Joyful » (plus d’un million d’exemplaires vendus), Ayo s’est imposée comme une figure incontournable de la scène musicale. Son talent brut et sa sincérité touchent en plein cœur un public toujours plus large.

Depuis, Ayo a enchaîné les succès avec des albums tels que « Gravity at Last » (2008), « Billie-Eve » (2011), « Ticket to the World » (2013) et « Royal » (2020). Chacun de ses opus est une invitation à un voyage musical intense, où les émotions se mêlent aux mélodies envoûtantes.

Ayo, c’est une voix qui vous envoûte, des mélodies qui vous caressent l’âme et des textes qui vous parlent droit au cœur. Elle est de ces artistes dont la grâce vous laisse sans voix.

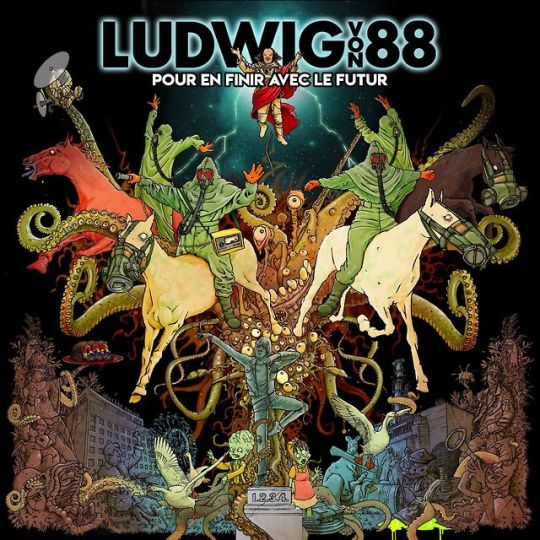

Ludwig von 88 (Punk Rock) – Ven. 08 Nov. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h30

Sur place : 23€ / Prévente : 20€ / Sur place (tarif réduit) : 20€ / Prévente (tarif réduit) : 18€ / Abonnés Moloco-Poudrière : 15€ / Enfants -10 ans : 5€

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

40 ans après leur naissance, les Ludwig von 88 atteignent le nirvana de la création ! Venez les découvrir si vous aimez LES SHERIFF, LES WAMPAS, LES RAMONEURS DE MENHIR, etc.

Pour célébrer cette apothéose, alors qu’ils seront emportés vers les cieux musicaux du paradis des punks, accompagnés par les muses désaccordées et une ribambelle d’angelots bourrés, ils vous offriront de multiples surprises...

En première partie, Alvilda, ou l’éloge de la simplicité : juste quatre musiciennes qui se font plaisir, influencées par le garage 60’s autant que par le punk rock, on rangera ça dans power pop et on dégustera bien frais. Des chansons-tubes de 2 minutes trente (maxi), perles pop anguleuses et énergiques montées en collier de filles des âges farouches. Et puis il y a ce bonheur de jouer ensemble aussi évident que contagieux, balancé à la face d’un monde morose et déprimant. Sourire contre sourire, échange de bons procédés, à bas les poseurs, vive la fraîcheur.

ISAAC DELUSION (Pop) – Sam. 09 Nov. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h30

Sur place : 23€ / Prévente : 20€ / Sur place (tarif réduit) : 20€ / Prévente (tarif réduit) : 18€ / Abonnés Moloco-Poudrière : 15€ / Enfants -10 ans : 5€

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

En une dizaine d’années, Isaac Delusion a sorti plusieurs albums acclamés, « Isaac Delusion » (2014), « Rust & Gold » (2017) et « Uplifters » (2020). Chacun de ces opus révèle une évolution musicale constante, témoignant de l’exploration et de l’expérimentation du groupe dans de nouvelles directions sonores. Avec des titres phares comme « She Pretends », « Midnight Sun » ou « Isabella », le groupe a su séduire un large public. La pop, musique intemporelle par excellence, a toujours eu de nombreux fans et le public du groupe lui reste fidèle depuis ses débuts.

La pop anglo-saxonne, elle, a ses codes, indémodables. Des codes qu’Isaac Delusion maîtrise à la perfection et complète d’une touche personnelle très forte, mise en lumière par l’empreinte vocale immédiatement reconnaissable de Loïc, chanteur/compositeur du groupe. Ce dernier reconnaît par ailleurs être inspiré par des artistes comme Phoenix, James Blake, Sufjan Stevens ou encore par la folk angélique de Angelo De Augustine, mais c’est plus une question de sensibilité partagée que de références.

SOVIET SUPREM (Punk Rap) – Ven. 15 Nov. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h30

Sur place : 20€ / Prévente : 18€ / Sur place (tarif réduit) : 18€ / Prévente (tarif réduit) : 16€ / Abonnés Moloco-Poudrière : 15€ / Enfants -10 ans : 5€

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

Depuis 10 ans, SOVIET SUPREM soulève les foules, à l’endroit, à l’envers et toujours de la gauche vers la gauche. Les deux gènes-héros fédèrent un public de la crèche à l’ehpad. Après avoir révisité la sono mondiale au travers de l’oeil de Moscou et pris le contre-pied de la world music anglosaxone (“L’internationale“ 1er album) puis s’être tourné vers l’électro-minimal teinté de chœurs de l’armée rouge (“Marx Attack“ 2ème album 2018), Soviet a pris le train de l’orient extrême et est de retour avec un 3ème opus résolument rap et tourné vers l’Asie. Ni affilié à l’empire (rap commercial) ni au milieu (rap de gangster) Sylvester Stalying et John Leyang vont faire beaucoup mieux et conquérir l’empire du milieu ! Une partie de Ping Pong en diphtongue, une joute endiablée avec Xian Chi Zong, rappeur chinois exilé, un bon wok pimenté pour déglacer le wokisme… Découvrez comment nos 2 héros passent de Poutine à Xi Jin Ping, comment ils caillassent de Maïdan à Taïwan.

Zamdane (Rap français) – Sam. 30 Nov. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h00

Prévente : 20€ Abonné / 22€ Réduit / 24€ Tarif plein

Sur place : 20€ Abonné / 23€ Réduit / 26€ Tarif plein

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

Zamdane a trouvé sa couleur, et son rythme. Le natif de Marrakech, installé à Marseille depuis 2016, défend depuis deux ans un premier album acclamé, « Couleur de ma peine », dans lequel il pose ce qu’il a sur le cœur sans ne jamais rien retenir. C’est cette honnêteté qui lui a permis de tisser un lien si fort avec son public, en atteste les 90 millions de streams accumulés par l’artiste en 2023 plus d’un an après la sortie du projet, à l’aube de la sortie de son nouvel album prévu pour début 2024.

Productif, Zamdane ne livre depuis « Couleur de ma peine » que des morceaux qui l’amènent encore plus loin, qui mettent en avant sa musique teintée d’une mélancolie qu’il sublime. Il raconte Marseille, le Maroc, et tout ce qu’il y a entre les deux. Teasé depuis un an, notamment lors de sa première grosse date parisienne à guichet fermée – les 1400 places de la Cigale, remplies en trois petites heures – puis devant les 9000 personnes rassemblées à Marseille pour son concert caritatif en faveur de l’association SOS Méditerranée, l’album « SOLSAD » s’annonce comme le projet de la consécration.

Sylvain Duthu (Chanson Slam) – Jeu. 05 Déc. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h30

Une production Le Bruit Qui Pense

Tarif unique : 25€

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

Connu comme chanteur du groupe Boulevard des Airs depuis 20 ans, + 500 000 albums vendus et une tournée des zéniths, Sylvain Duthu se lance en solo avec un nouvel album prévu en septembre 2024. Il y a quelques semaines, il dévoilait « Prologue » premier extrait puissant, intime qui mélange chanson et slam. Avec « Les jours qui restent » nouveau single sorti le 25 mars, Sylvain Duthu confirme la promesse d’un album sincère et résolument moderne. Ces deux clips tournés au Pays Basque montre l’attachement de l’artiste à cette région où il s’est installé depuis quelques années. C’est pourquoi, dès l’automne, il sera en tournée dans toute la France dont un soir dans sa ville de cœur, Biarritz, le 13 novembre à l’Atabal et le 19 novembre à la Cigale à Paris.

Popa Chubby (Blues Rock) – Ven. 06 Déc. 2024 au Moloco (Audincourt) – Ouverture des portes : 20h30

Sur place : 30€ / Prévente : 27€ / Sur place (tarif réduit) : 27€ / Prévente (tarif réduit) : 25€ / Abonnés Moloco-Poudrière : 22€ / Enfants -10 ans : 5€

Présentation de(s) artiste(s) :

Popa Chubby hard rock le blues depuis plus de 30 ans !

Ce musicien hors normes nous présentera son nouvel opus, Emotional Gangster (2022), qui « prêche la bonne parole d’un blues rock inflammable » (Rolling Stone), ainsi que ses plus grands tubes.

Comme une rencontre au sommet entre The Stooges et Buddy Guy, Motörhead et Muddy Waters ou Jimi Hendrix et Robert Johnson. Leader incontesté du New York City Blues, Popa Chubby écume depuis plus de vingt ans les salles de concerts du monde armé de sa Stratocaster de 66.

Crue, électrique, écorchée, sa musique résolument blues rock se démarque par une alchimie d’éléments empruntés au jazz, à la country, au funk, a la soul et même au gangsta rap. Personnage et guitariste hors normes, c’est un artiste engagé qui ne laisse personne indifférent.

Après avoir rempli l’Olympia en 2021 et en 2024, il poursuit sa tournée pour présenter son tout dernier album en live.

infos > www.lemoloco.com

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Oh wow I didn't realise! Wow. Well. That's kind of a lot.

[I feel the need to clarify: Ludwig von 88 are a french punk band and despite what the name might suggest, they are not nazis. They got their name after the founder's aunt whose name was Yvonne (nicknamed 'Vonne'), who was a Beethoven fan and who died at the age of 88. They're a ridiculous band with nonsensical silly songs about crêpes and french road racing cyclist Louison Bobet, who use costumes and pyrotechnics on stage. Not nazis. My dad used to sing some of their tunes to me when I was little, that's the whole reason I went and saw them live.]

I know a handful of people who follow bands/artists around on tour and attend every gig and that's kinda intimidating. I used to feel so small next to them. That certainly puts things in perspective. Sure, I can't afford 12 gigs a year, but 30 concerts at 27 is really nothing to be ashamed of. On the contrary, I'm so privileged.

Maybe one day I'll make a post that's just anecdotes from each of these concerts. Seeing this list had me reminiscing and there sure is a ton of memories to cherish there. ❤️

#I don't remember seeing youssou n'dour so I'm not 100% sure of the time & place#my only clue was a letter from my dad asking how the gig went#I don't think it was actually in the summer but nothing on setlist.fm fits#I just know I saw him when I was about 5-6#anyway I still need to see the the and david byrne and st vincent and cosmo sheldrake#I was supposed to see cosmo sheldrake next month but can you believe I sacrificed this to see yard act again?#no regrets though I'll catch him later I'm sure#I need to see the streets too but that's gonna be difficult to arrange#and last but not least: depeche mode provided I can afford them 💀

0 notes

Text

Ludwig Leo, Hans Scharoun und Sergius Ruegenberg | Aufsatz in der Publikation „Costruiamo una città“

Hans Scharoun und die von ihm maßgeblich geprägte Form des organischen Bauens waren wichtige Referenzpunkte für Ludwig Leo. Seine Architektur kann aber nicht nur in ihrer äußeren Form als „expressiv“ beschrieben werden. Weitaus wichtiger ist, dass Leos konzeptioneller Ansatz im Umgang mit Grundrissen und Innenräumen Aspekte des spezifischen Entwurfsdenkens des organischen Bauens aufgreift.

Der Aufsatz von Gregor Harbusch entstand im Zusammenhang mit einem Symposium an der UIAV in Venedig im September 2021.

Gregor Harbusch, From Scharoun via Ruegenberg to Leo. Some thoughts on expressive forms and organic conceptions in Ludwig Leo’s architecture, in: Costruiamo una città. Architettura espressionista tedesca nel secondo dopoguerra, hrsg. von Giacomo Calandra di Roccolino, Luca Monica und Gundula Rakowitz, Clean Edizioni, Neapel 2023.

160 Seiten, 15 Euro

ISBN 978-88-8497-876-9

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Buttrick, celebrated pianist and former director of music at MIT, dies at 88

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/john-buttrick-celebrated-pianist-and-former-director-of-music-at-mit-dies-at-88/

John Buttrick, celebrated pianist and former director of music at MIT, dies at 88

John LaBoiteaux Buttrick, a former professor in MIT’s Music and Theater Arts Section and prize-winning pianist, died in late November, 2023, in Zurich, Switzerland. He was 88.

Buttrick joined the humanities faculty at MIT in 1966, where he lectured and taught as a professor of humanities and music. He served as the head of MIT’s music section from 1967 to 1976. He taught introduction to music subjects as part of the humanities requirement and was, according to colleague and MIT professor Marcus Thompson, “very popular.”

Buttrick was born Dec. 15, 1934. He grew up in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, and Nantucket, Massachusetts. He spent a year at Haverford College before later earning a BS in 1957 and an MS in 1959 from the Juilliard School of Music. He completed additional graduate work at Brandeis University. During his personal and professional career, he studied piano with Isidor Philipp, Rudolf Serkin, and Beveridge Webster.

One of Buttrick’s first professional outings was as a participant in the Marlboro Music Festival.

Beginning in 1961 he toured major European cities performing in recitals and as a soloist with symphony orchestras. Critics from news organizations in Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Zurich lauded his “technical and musical prowess and his communicative gift.” He also toured with orchestras and groups across the United States and Europe for most of his life.

During his tenure at MIT, Buttrick performed numerous solo recitals in Kresge Auditorium, favoring Beethoven. He was also a soloist with the MIT Symphony Orchestra on a national tour to several major American cities. The tour was hosted by the MIT Alumni Association and conducted by Professor Emeritus David Epstein.

An article in Time magazine reported that, under Buttrick’s leadership, MIT saw its music faculty more than double to 13 and oversaw the increasing popularity of its music courses; two-thirds of the 1973 sophomore class enrolled in them. The Institute’s student orchestra, under Buttrick’s direction, regularly sold out the Kresge Auditorium.

Buttrick, alongside MIT students, was also featured in a weekly radio program, “After Dinner,” which was broadcast on station WGBH in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The program featured “informal, four-handed playing of pieces by Mozart and Schubert.”

He was frequently featured in chamber music presentations on MIT’s campus accompanied by other prominent artists like French flutist and Marlboro School of Music co-founder Louis Moyse, son of the famous flutist Marcel Moyse.

Buttrick was passionate about his musical forebears, particularly Beethoven. The liner notes Buttrick wrote for his 1983 album — “Ludwig von Beethoven: Klaviersonate Nr. 30 E-Dur, Op. 109 – Klaviersonate Nr. 31 As-Dur, Op. 110” — released in Switzerland on the label Jecklin Musikhaus, described Beethoven’s sounds as “melodic shapes and figurations” and “rounder and more undulant.”

Buttrick recorded several other albums of music by Franz Schubert, Ferruccio Busoni, Joseph Haydn, Max Reger, Richard Strauss, Johannes Brahms, L.van Beethoven, César Franck, and Frédéric Chopin. His favorite composers were Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, and Chopin.

Buttrick believed in music’s power to heal people. A former student of Joseph Pilates, Buttrick healed after suffering significant injuries to his hand, arm, and shoulder. Later, he came to practice movement therapy, helping clients avoid surgery using alternative therapies.

While living in America, he was active on Nantucket and a member of the Congregational Church, where many passersby could hear him practicing the piano any given weekday.

In 1985, John relocated to Zurich, where he continued to teach, perform, and engage in the arts. While in Zurich, he met and later married Irene Buttrick. He officially took leave of his MIT position in 1988.

Buttrick is survived by his children, Miriam, David, Simon, and Michael; five grandchildren; ex-wife and caregiver Irene; brothers Daniel Drake and Hoyt Drake; and numerous beloved nieces and nephews.

#2023#America#arm#Article#artists#Arts#berlin#Born#career#Children#cities#classical#college#courses#direction#double#Europe#Faculty#Featured#hand#Humanities#injuries#leadership#life#max#mit#MIT students#movement#Music#Music and theater arts

0 notes

Text

Indie 5-0: 5 Qs with Sound Strider

Sound Strider is no ordinary artist; he's a sonic explorer traversing the globe, leaving his creative mark in the most extraordinary places.

Humbly taking 2023 by storm, Sound Strider took on quite a few diverse roles – from traveling to Spain to DJ in a castle, to exploring the prestigious exhibits at La Biennale di Venezia in Venice, to fully immersing himself in Burning Man, and lots more.

His music compound, La Briche, nestled in the heart of France, serves as a creative sanctuary where various projects come to life. However, his global ventures don't stop there. Sound Strider curated, created, and hosted the Music, Magic, Medicine event in Germany this past summer, bringing together a tapestry of sounds and experiences that transcend the ordinary.

Sound Strider isn't just an artist; he's a visionary, host, musician, and entrepreneur. His journey is an odyssey through the uncharted territories of music and mystery, consistently pushing boundaries and creating a legacy that resonates globally. The world may not always see the unsung heroics, but Sound Strider's impact is felt across continents, making him a true maestro of sonic exploration.

Sound Strider just released his latest single, Psychedelic Ritual, and we are super happy to catch up with him for Indie 5.0 - please enjoy!

Can you tell us about your journey as an artist and how your diverse musical influences have shaped the unique sound of Sound Strider?

I started out learning drums as a kid. My dad was a classical musician so he hooked me up with an orchestral percussionist who taught me the fundamentals of rhythm and I also spent some time studying under a jazz drummer who introduced me to the african american greats Art Blakey and Bernard Purdie who remain key influences today. I played in a few different bands through my teenage years mostly punk and jazz and although I had been to a few rave parties it wasn't until around 2004 that I got heavily into electronic music. I started out with a pirate copy of Fruity Loops and learned how to DJ on vinyl quickly getting involved in the NuSkool Breaks scene in Sydney. Not long after I went to my first Earthcore and immediately fell in love with Doof culture; a uniquely Australian take on the global psytrance phenomenon where I started playing parties with a unique blend of breaks and psy. The next big change came in 2008 when I decided to move to the French countryside to turn a decaying agro-industrial ruin into a recording studio and artists hub. Not long after arriving I fell in with the French free party crowd which was a much harder and more brutal version of the australian doof, maintaining a strong emphasis on psychedelics and connection with nature but with much higher BPMs, straighter grooves and more aggressive textures having evolved out of Punk and specifically the seminal french punk bands Ludwig von 88 and Berurier Noir who used drum machines instead of actual drummers. This twisting path through different landscapes of underground electronica is I think what gives Sound Strider its unique flavour and probably why people seem to have a lot of trouble finding a genre that fits my work.

Your passion for travel and immersion in foreign cultures is well-known. How have these experiences impacted your music, and could you share a memorable cultural encounter that inspired your work?

Probably the most impactful encounter has been my connection to Santiago de Cuba where my sister was living and working as a dancer for over a decade. I visited regularly over the years and became quite intimate with the musical culture surrounding Santeria, a syncretic Afro-Cuban religion based on Yoruba mythologies and rhythms. This was my first time encountering a musical culture which was also a powerful spiritual technology. I witnessed possessions, healings and other phenomena which definitively broke my belief in western materialism and turned me on to the immense transformative power of music and the nascent potential of the psychedelic rave movement as a vehicle for re-establishing communication with the living cosmos.

As the owner of La Briche, how has this venture influenced your music production process and collaborations with other artists? Are there any exciting projects currently underway at La Briche that you'd like to mention?

The residential studio, at least in its most recent incarnation which dates to around 2019 has been something of a double edged sword. On one hand it has introduced me to dozens of fantastic musicians, given me an excuse to buy all sorts of wonderful gear (nothing quite like the sound of a real hammond/rhodes) and given me a huge space to experiment with techniques that go far beyond the laptop and monitor approach that most electronic musicians today are using. On the other hand I have found my creative energies being sapped by the fact that I am constantly working to help other people bring their creative visions to life. I think its no coincidence that my last EP was released in 2018 just before the studio business got underway. That said I am managing to balance my time better now and the production process has definitely evolved. I am using a lot more live instrumentation and really learning how to use the space as an instrument as opposed to doing everything 'in the box'. As for exciting projects in the pipeline we are looking to host our first mini festival onsite in May 2024, I'm also currently working on preproduction for a grand 'live in pompeii' style filmed performance of a musical project called Metabards which I started many years ago that takes its inspiration from greek mythology.

Your interest in alternative spiritual practices and the occult adds a unique dimension to your art. How do these elements connect with your music, and what messages or experiences are you aiming to convey to your listeners through this aspect of your work?