#Peter Allas

Text

Quando parlo con conoscenti, alle cene, a lavoro, agli aperitivi e in generale in tutte quelle occasioni sociali in cui si parla del più e del meno, magari dell'ultimo caso di cronaca o delle imprescindibili opinioni che il fenomeno della serata sente il bisogno di sciorinare circa un argomento qualunque, ebbene quando parlo con queste persone, in questi contesti, e magari salta fuori l'argomento nudità, esibizionismo, bdsm e magari queste persone esprimono indignate il proprio disappunto, io, tra una risata divertita e uno sguardo malizioso, mi ricordo di quello che diceva quel tale io vivo di ciò che gli altri ignorano di me.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

playlist 02.28.24

Chaser Planned Obsolescence (Decoherence Records)

Free Human Zoo The Mysterious Island / No Wind Tonight / Freedom Now! (Bandcamp)

The Smile Wall of Eyes (XL)

Hypochristmutreefuzz Hypopotomonstrosesquipodaliophobia (Bandcamp)

Idles Tangk (Partisan)

William Susman Collision Point (Belarca)

Anemic Cinema Iconoclasts (Ramble Records)

Decibel After Julia (Tall Poppies)

Austin Wulliman The News from Utopia (Bright Shiny Things)

Trupa Trupa B Flat A (Lovitt Records)

Univers Zero Lueur (Sub Rosa)

USA Nails Character Stop / No Pleasure / Shame Spiral / Sonic Moist (Bandcamp)

Annahita Abbasi Intertwined Distances / Situation I / Situation VIII (YouTube)

Peter Michael Hamel Nadia (Wergo)

Alla Es Tiempo (Crammed)

Donato Dozzy Magda (Spazio Disponibile)

Jasmine Morris Astrophilia (Non-classical)

#Chaser#Free Human Zoo#playlist#The Smile#Hypochristmutreefuzz#Idles#William Susman#Anemic Cinema#Decibel#Austin Wulliman#TrupaTrupa#Univers Zero#USA Nails#Annahita Abbasi#Peter Michael Hamel#Alla Es#Donato Dozzy#Jasmine Morris

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

all of peter outerbridge's scenes in "close to you"

#peter outerbridge#close to you#he improvised alla that and it was beautiful#peter outerbridge the man that you are

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#alla nazimova#salome#charles bryant#art film#black and white#classic#silent#film#silent film#poster#movie poster#movie posters#natcha rambova#charles van enger#movie#peter m winters#nazimova production

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

al things considered — when i post my masterpiece #1291

first posted in facebook march 19, 2024

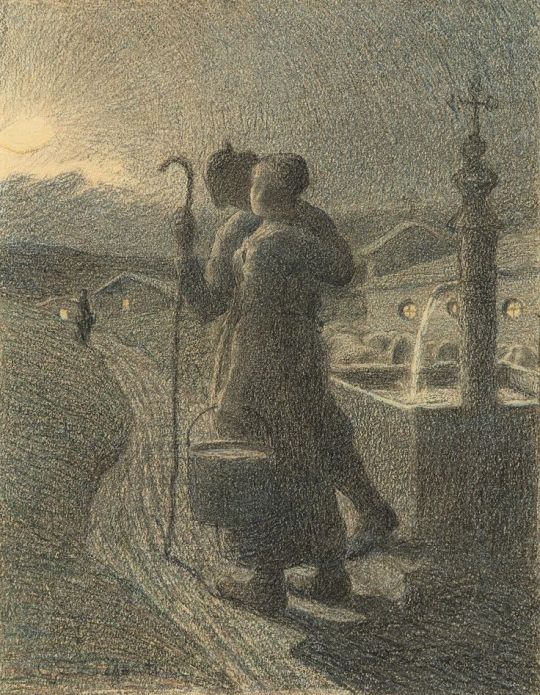

giovanni segantini -- "un bacio alla fontana" [i.e., a kiss at the fountain] (no date)

"elisabeth stood beside me in front of a large painting by segantini and she was totally engrossed in contemplation" … herman hesse

"i live in rome where people sit by fountains and kiss. the sound of water is the sound of love rushing between them" … simon van booy

"the fountains mingle with the river,

and the rivers with the ocean;

the winds of heaven mix forever,

with a sweet emotion;

nothing in the world is single;

all things by a law divine

in one another's being mingle:—

why not i with thine?

see! the mountains kiss high heaven,

and the waves clasp one another;

no sister flower would be forgiven

if it disdained its brother;

and the sunlight clasps the earth,

and the moonbeams kiss the sea:—

what are all these kissings worth,

if thou kiss not me?" … percy bysshe shelley

"take these unsightly flowers, these violets, as a symbol of my great love, when a spring comes in which i fail to send you such violets, you will no longer find me among the living" … giovanni segantini

"she lit a burner on the stove and offered me a beer

'i thought you'd never say hello,' she said

'you looked so bashful, dear'

then she opened up a book of paintings and handed it to me

drawn by an italian painter from the 19th century" … al janik

#giovanni segantini#un bacio alla fontana#a kiss at the fountain#elisabeth#herman hesse#peter camenzind#simon van booy#kiss#rome#love#percy bysshe shelley#kissings#if thou kiss not me#flowers#among the living#italian#al things considered

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Real footage of me after telling my friends the characters that are literally us in JRWI [she doesn’t listen to JRWI and has no idea who the fuck I’m talking about]

#it also always ends up being the queers for some reason..#that or sometimes on rare occasions the sibling relationships#mostly the gays tho..#here’s the list btw :33#Br’aad and Taxi#William and Vynce#Soda and Emizel#Peter and Rumi#Chip and Jay#Arthur and Deacon#there’s more but yea😭#im the first one in alla those btw#UPDATE SHES LISTENING TO PRIME DEFENDERS GUYS#IM SCREEEAMING

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tempo fa, per un evento di scrittura chiamato COWT, ma comunemente noto come "le 6 settimane dell'ansietta" ho pubblicato una storia dove Pietro Parcheggiatore (Peter Parker per gli anglosassoni) doveva comprare delle mascherine daa maggica Roma, anche se era Covidde non c'ha preferenze de squadre de calcio, ndo coje coje.

Ma perché vi sto dicendo questo? Perché @innominecarbohydrates ha realizzato per me questo disegno BELLISSIMO proprio dedicato a quella storia, per l'iniziativa B.I.BI.T.A. indetta da @landedifandom e VI PREGO AMMIRATELO È BELLISSIMO 🥲🥲🥲🥲 è stato un regalo stupendo, per una storia che ha il sapore di quel COWT (Il primo a cui abbiamo partecipato entrambe) e quindi ha un valore inestimabile sia visivamente che sentimentalmente!

Grazie ancora per averlo realizzato per me 🥲💛

Miry

#un regalo bellissimo 🥲#quanto amore da dare alla ciuri per eccellenza 🥲💛#spider man#spiderman#peter parker#pietro parcheggiatore#roma#Avengers#zia may#zia Margherita#marvel#tony stark#ironman#art by op#ciuri#cowt#landedifandom#bibita

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

La ci darem la mano is one of my fav songs from my fav opera and the met is doing a new production and they showed a clip on youtube and

youtube

Is that a fucking gun?? Don Giovanni is packing in more than one meaning of the word

#im gonna get fucking blocked by the met on YouTube cause i totally just swore in their comments#anyway peter mattei is amazing i adore his version of the come to the window aria#the deh vieni alla finestro song#anyway i am looking disrespectfully#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 aprile … ricordiamo …

15 aprile … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2023: Mario Fratti, drammaturgo italiano. La sua produzione conta oltre 100 opere, tradotte in 20 lingue e rappresentate in 600 teatri di tutto il mondo. Dopo la laurea in Lingue e Letterature Straniere conseguita all’Università Ca’ Foscari a Venezia, Fratti avviò alla fine degli anni cinquanta una ricca produzione drammatica. È del 1959 il suo primo dramma Il nastro, vincitore del premio RAI.…

View On WordPress

#15 aprile#Antonio De Curtis#Antonio Griffo Focas Flavio Angelo Ducas Comneno Porfirogenito Gagliardi De Curtis di Bisanzio#Brian Dennehy#Brian Manion Dennehy#Bruce Myers#Divina#Elizabeth Ann Sheridan#Estelle Taylor#Giovanna Fontana#Greta Garbo#Greta Lovisa Gustafsson#Harald Haubenstock#Harry Meyen#Ida Estelle Taylor#il principe della risata#Liz Sheridan#María Ester Beomonte#Maria Denis#Mario Fratti#Nicholas Peter Conte#Raimondo Vianello#Riccardo Billi#Richard Conte#Ricordiamo#stile alla Garbo#Tim McIntire#Timothy John McIntire#Totò#Wallace Beery

0 notes

Text

bittersweet ~ a yandere!John Wick x fem!reader sunshine/grump coffee shop AU... Part 12 all chapters

- Lunch is a lovely affair in a quaint little trattoria that has been making world class dishes since the turn of the previous century. It seems like every inch of this city is steeped in history. The prices on the menu would blow your whole daily budget on one meal. But the scampi alla Veneziana is out of this world, and you force yourself to eat slowly, and not just inhale the perfectly prepared shrimp and noodles with a delicate lemon olive oil dressing.

John's friend, Julius, is a kind and utterly elegant older man who accepts your presence at the table with kingly grace. They speak in a mixture of Italian and English, the latter you think is for your benefit. John very generously includes you in the conversation, telling Signor Castellari that you are an artist, talking you up to what you feel is an exaggerated degree. Julius asks to see your work, and you let him flip through your new sketch book. Your drawings are a mixture of studies and whimsical travelogue, and it feels like you’re baring a piece of your soul, but he’s so gracious you feel you can’t say no.

There is more than one sketch of Mr. Wick in those pages you did from memory with an aching heart, but the old man is kind enough not to call you out on it, or even draw John’s attention to it. You think if he did, you would simply crawl under the table and die of embarrassment.

He exclaims over an ink and watercolor pencil plein air you did in Rome of a sunset over St. Peters with the Sant’Angelo bridge in the foreground, saying it reminds him of a special day when he was a much younger man. You offer to let him keep it, and he seems truly delighted.

You watch with some surprise as John produces what looks like a razor-sharp knife from seemingly nowhere to carefully cut the page from your book. Julius accepts it like a precious treasure, and you are flattered to your toes.

Then John and Julius chat about older books, and Julius produces a very old looking volume, handing it over for the younger man’s perusal. As he runs his hands over the leather cover John’s eyes shine with an almost childish delight—its utterly adorable.

While they are gushing over the antique tome two intimidating men in dark suits approach the table, fixing John with a hard look. One of them has a gnarly scar bisecting his brow. They say something that sounds none too friendly. You catch the name d’Antonio—but John waves them off with a glare, insisting, “Sono ritrirato.”

You’re pretty sure that means I’m retired.

Julius watches the exchange with a sadness in his eyes you don’t understand.

Finally after some grumbling the tough men go away. John watches them with eyes sharp as a hawk’s, and something in the back of your brain titters a little warning. But you’re having too lovely of a time with Signor Castellari, so you ignore it.

When you part ways Julius kisses your cheeks and takes your hands in his. “Be good to him, bella,” he says with a glance to John. “No one I know deserves happiness more than him.”

You don't want to contradict him about your actual relationship with John, so you just nod.

Later you ask, “Did you tell him we're...”

“No, but even if I told him we weren't, he wouldn't have believed me. Sorry. I hope that didn't make you uncomfortable...”

“It's fine,” you say, not offended in the least.

It’s more than fine.

It's incredibly flattering, really, that he thought the two of you could be a match. You're fairly sure you look like an unsophisticated street urchin next to Mr. John Wick.

“Where would you like to go now?” John asks with a little smile, as though he knows you've been hopelessly turned around for the past two days. You’ve managed to find the big landmarks, like the Piazza San Marco and the Doge’s Palace. It’s the smaller sights that have escaped you.

“Let’s go for a walk,” you suggest, wanting to see the city, and knowing you will finally get to do it unmolested with the forbidding figure of John towering at your side.

You are standing on a bridge, watching gondolas go by, when he asks you, “If I told you I have a reservation at Casa Nova, would you have dinner with me?”

You press your lips nervously. Lunch is one thing, you know, and dinner something else entirely. Two people alone together in an intimate setting, sharing a meal over candlelight with good wine...the thought sends a thrill to the tips of your fingers that’s so intense it’s almost painful.

“I don't have anything to wear to a place like that,” you admit. You read about it in a Condé Nast magazine on the plane, and you’re pretty sure it has at least one Michelin star. “I'm backpacking. My dresses are literally all rolled up in a bundle.”

He chuckles at that, a low sound that tugs at your abdomen. He leans a little closer on the railing, and not for the first time this day you just wish he would kiss you.

“What if...I took you shopping?”

You raise an eyebrow to that. “Are you trying to be my sugar daddy, Mr. Wick?” You mean it as a joke, but suddenly there is something electric in the air between you. John's initial embarrassment sharpens to something almost…predatory.

It catches your breath in your throat.

“Do you want a sugar daddy, y/n?”

You laugh it off nervously, your heart skittering about in your chest.

“Very funny.”

You have a feeling he wasn’t joking at all.

However, like a gentleman he lets you have the out, but doesn't drop the shopping offer.

“Let's go to the Calle Larga,” he says, and out of pure curiosity you agree.

John's idea of shopping is taking you to Gucci.

The impeccable store is filled with beautifully crafted but honestly kind of boring goods, arbitrarily priced at a thousand dollars or more a piece. John fits in perfectly with the smartly dressed clientele, but you? You feel so incredibly out of place amidst the filthy rich people in the shop, and when you look at the price tag on the only dress you vaguely like you think you might break out in hives.

“John...”

You don't recognize it just yet, but you call him John when you're agitated, and Mr. Wick when you're feeling playful.

He senses the desperation in that one word, and he takes you by the hand, leading you outside.

“I'm sorry...” you say, because you feel stupid, and not posh enough by half to pull off any of the clothes in that high-end boutique. You are a bonafide gremlin, compared to the unearthly creatures in there. You do not belong, and maybe you’re a coward, but a part of you wishes John would just let you go back to your own plans for the evening. A long solo walk, a cheap slice of pizza, inevitably get lost in the maze of streets and canals, draw a little or read some of your book, before returning to your hard, lumpy hostel bed alone, where you can’t make a fool of yourself.

“Don't be,” he says with an amused little smile that makes your tide of panic recede a little. “I like it that you know this stuff is bullshit,” he soothes you.

“I just...it’s so out of my wheel house.” You could have paid nearly four months rent for what that dress had cost.

He nods. “It takes some getting used to,” he admits. “I certainly wasn't born into this.”

You wonder if he’ll ever tell you about his earlier life, but sense this isn’t the time or place to press him.

“I just don't want you to spend your hard-earned money on stupid things for me.”

“I’m not saying I didn’t work hard for my money…” he offers with a wan little smile. “But it would make me happy to spend it on you. If it would make you happy.”

You look at him for a long time. He meets your gaze, not flinching. There’s something different about him here. He’s more…open with you, perhaps? It takes some getting used to. He’d never outright admitted his interest in you before, always circling around it, and you wonder what’s changed.

Maybe not even John Wick is immune to the romantic atmosphere of il bel paese.

“Why are you being so good to me?”

“I like you, y/n. If you haven't noticed.” The corner of his mouth quirks at that.

It makes you sigh.

“I like you too, Mr. Wick.”

He makes a small sound in the back of his throat.

“You can call me John.”

“But do you want me to call you John?” you tease.

He moves a fraction closer, looming over you, and for a heart stopping moment you think maybe now he might finally kiss you?

“Depends,” he admits, his voice gone a little rough, but he doesn't elaborate further.

You feel as though you have a live electric wire sparking under your skin.

He steps back a little, and again you feel the loss of him like an ache over your heart. You continue to stroll down the street. You are not entirely sure how your hand ends up in his, only that it is there, and you are content.

None of the high fashion shops really interest you, until you pass by the window of Dolce and Gabbana, and your feet involuntarily slow as you take in the maximalist riot of glitz and color on the mannequin. You've always admired their wildly bedazzled designs, flaming hearts and candy colored jewels with copious gold embroidered trim. Maybe you’re just a crow-brained peasant who’s impressed by shiny things, but they look so fun.

John smiles a little, as though he’s finally answered some question to himself about you. “Aha,” he says teasingly, and you sigh, restraining yourself from pressing your nose to the window like a child outside a candy store.

“Can we just…look?”

You are trying to be reasonable.

“We can.”

As it turns out, you want one of everything in the store.

It's all so over the top, the designs are so artistic and ridiculous and unabashedly joyful, from bejeweled purses to crown-adorned headphones, loud floral dresses and majolica printed silk scarves, and you fight not to betray which pieces catch your eye because you're afraid John might buy them all.

He is drinking in your enjoyment, looking utterly pleased.

Even just the store itself is utterly breathtaking inside, crystal chandeliers, inlaid marble floors and stone pillars. Gilded crown moulding and inlaid wood trim. You could just sit and look at this place like it’s a museum, you reckon.

John is not looking at the building though. He watches you browse with eyes that miss nothing, and it makes you squirm a little. You feel so seen. You’re not sure you like it, like you’ve been caught in the act of enjoying something that you know is absurd.

You feel absolutely silly.

“Try something on,” he urges you. To be practical, you decide to try on a black lace dress. Just in case you might like it. And a pair of black platform wedges printed with crimson red roses…because you can actually walk in them, so it makes sense, you know...

When you exit the dressing room John's gaze darkens, his pupils blown wide with desire, and once again you sense that predatory edge in him. If you had any sense you might have been scared, or at least cautious—but all it does is give you the most exquisite chills, an aching sense of anticipation, and an excess of moisture pooled between your thighs.

“That one,” he confirms, and for the way he looks at you, like you are a bunny in the woods he'd like to eat up whole, the outrageous price of the ensemble seems like a bargain.

#john wick#john wick x reader#john wick x y/n#john wick x you#keanu reeves x reader#john wick fic#keanu reeves#bittersweet john wick imagine#john wick imagine#i couldn't find julius's last name?#anyone kno?#yandere john wick

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

a list of some spring movies/series 🌷

spring is here!! and so is your friendly neighbourhood little organisation freak of a goblin to give you a list of some spring movies and series.

as always, just close your eyes and point somewhere on this little list, or even put the numbers in a generator and go with whatever the result is ♡

summer | autumn | winter

🐝 ‧₊˚ ⋅ movies ⋅˚₊‧

mary poppins (1964)

the sound of music (1965)

aristocats (1970)

alla vi barn i bullerbyn (1986)

my neighbour totoro (1988)

kiki's delivery service (1989)

a league of their own (1992)

the secret garden (1993)

pride and prejudice (1995/2005)

whisper of the heart (1995)

clueless (1995)

my best friend’s wedding (1997)

parent trap (1998)

10 things i hate about you (1999)

notting hill (1999)

she's all that (1999)

but i’m a cheerleader (1999)

bring it on (2000)

miss congeniality (2000)

spiritied away (2001)

the wedding planner (2001)

legally blonde (2001)

princess diaries (2001 + 2004)

spy kids (2001-2003)

maid in manhatten (2002)

bend it like beckham (2002)

tuck everlasting (2002)

school of rock (2003)

how to lose a guy in 10 days (2003)

something’s gotta give (2003)

13 going on 30 (2004)

finding neverland (2004)

howl’s moving castle (2004)

saving face (2004)

the notebook (2004)

imagine me and you (2005)

nanny mcphee (2005)

penelope (2006)

miss potter (2006)

step up (2006)

she’s the man (2006)

bridge to terabithia (2007)

enchanted (2007)

atonement (2007)

stardust (2007)

ps i love you (2007)

wild child (2008)

made of honour (2008)

ondine (2009)

bride wars (2009)

valentine’s day (2010)

tangled (2010)

leap year (2010)

easy a (2010)

from up on poppy hill (2011)

jane eyre (2011)

crazy, stupid, love (2011)

what to expect when you’re expecting (2012)

remember sunday (2013)

saving mr banks (2013)

about time (2013)

now you see me (2013 + 2016)

love, rosie (2014)

testament of youth (2014)

kingsman (2014-)

paddington (2014 + 2017)

far from the madding crowd (2015)

burnt (2015)

brooklyn (2015)

cinderella (2015)

the man from u.n.c.l.e. (2015)

lady chatterley's lover (2015/2022)

creed franchise (2015-2023)

me before you (2016)

mother’s day (2016)

this beautiful fantastic (2016)

the light between oceans (2016)

paterson (2016)

how to be single (2016)

hidden figures (2016)

gifted (2017)

dunkirk (2017)

ocean’s eight (2018)

life itself (2018)

peter rabbit (2018)

christopher robin (2018)

tomb raider (2018)

set it up (2018)

crazy rich asians (2018)

spider-verse movies (2018-)

1917 (2019)

the art of racing in the rain (2019)

can you keep a secret? (2019)

booksmart (2019)

someone great (2019)

endings, beginnings (2019)

emma (2020)

enola holms (2020-)

the last letter from your lover (2021)

the world to come (2021)

🌼 ‧₊˚ ⋅ series ⋅˚₊‧

little house on the prairie (1974-1983)

moomin valley (1990-1992)

greys anatomy (2005-)

gossip girl (2007-2012)

skins (2007-2013)

the great british bake off (2010-)

new girl (2011-2018)

brooklyn nine-nine (2013-2021)

the fosters (2013-2018)

the 100 (2014-2020)

jane the virgin (2014-2019)

outlander (2014-)

grace and frankie (2015-2022)

poldark (2015-2019)

critical role (2015-)

howards end (2017)

girlboss (2017)

she's gotta have it (2017-2019)

the bold type (2017-2021)

mr. sunshine (2018)

queer eye (2018-)

crash landing into you (2019)

the witcher (2019-)

dickinson (2019-2021)

sex education (2019-2023)

bridgerton (2020-)

ted lasso (2020-2023)

nevertheless (2021)

abbott elementary (2021-)

flatshare (2022)

#lea speaks#• comfort if you need it •#movies#comfort movies#movie recommendation#studyblr#cottagecore#dark academia#cozycore#cosycore#hygge#naturecore#tv show recommendations#spring#spring aesthetic#spring movies#springcore#cottage core

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuumin suomalainen vintagenäyttelijä

äänestys on nyt valmis alkamaan! äänestyksessä on mukana yhteensä 66 näyttelijää, eli äänestyspareja on 33. kaikki parit on arvottu sattumanvaraisesti onnenpyörän avulla

kierroksen 1 voittajien parit järjestyvät niin, että parittomat saavat vastaansa parittomat ja parilliset parilliset (eli parin 1 voittaja saa vastaansa parin 3 voittajan ja parin 2 voittaja parin 4 voittajan jne).

(lisäys!! koska voittajia tulee olemaan 33, parhaiten pärjännyt häviäjä kohtaa parin 33 voittajan)

(minähän en tajunnut tätä vasta äänestyksen alettua, en toki)

propagandaa omasta suosikista saa ja on suotavaa postata, mutta älkää postatko mitään negatiivista heidän kilpailijoistaan

allekirjoittanut äänestää myös, mutta reiluuden takaamiseksi en kerro, miten äänestän

vaikka äänestyksessä puhutaan kuumimmasta näyttelijästä, äänestää saa millä tahansa perusteella. perusteita ovat ulkonäön lisäksi mm. näyttelijäntaidot, tunnettuus, sekä meemiarvo. ja tottahan kauneus on katsojan silmässä!

ja muistakaa reblogata, jotta tämä äänestys leviää mahdollisimman paljon ja ääniä ropisee!

äänestysparit ovat seuraavan readmoren alla

laura malmivaara vs tuija halonen

aino mantsas vs pentti siimes

seela sella vs matti ranin

tapani kalliomäki vs eila roine

matti pellonpää vs pirkko hämäl��inen

eeva-kaarina volanen vs pirkko mannola

juha veijonen vs heikki kinnunen

olavi virta vs taneli mäkelä

martti suosalo vs minna haapkylä

elina salo vs åke lindman

ansa ikonen vs tauno palo

jussi jurkka vs vieno kekkonen

anneli sauli vs markku toikka

kati outinen vs matleena kuusniemi

irina björklund vs pirkka-pekka petelius

mato valtonen vs samuli edelmann

timo kahilainen vs teuvo tulio

ville virtanen vs heikki hela

helge herala vs kunto ojansivu

heidi krohn vs siiri angerkoski

regina linnanheimo vs jasper pääkkönen

lena meriläinen vs tommi korpela

leo jokela vs peter franzén

tapio hämäläinen vs helena kara

silja sillanpää vs martti katajisto

elina pohjanpää vs joel rinne

ester toivonen vs mirja mane

kalevi kahra vs sakke järvenpää

leif wager vs olavi pajunen

heikki silvennoinen vs vesa-matti loiri

turo kartto vs sirkka lehto

kaisu leppänen vs kristiina halkola

ria kataja vs tiina lymi

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

BETTER CALL SAUL by Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould (2015-2022) // ALL THAT JAZZ, dir. Bob Fosse (1979)

#concerto alla rustica is playing in the background

#it's showtime folks!#better call saul#bcs#bcsedit#all that jazz#filmedit#tvedit#jimmy mcgill#saul goodman#vince gilligan#peter gould#bob fosse#bcs 1.02#bcs 6.10#bcs 6.13#cinematv#moviegifs#tvgifs#dailyflicks#tvfilmsource#poetic cinema#my gifs#my edit

860 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midnight Pals: $8

Stephen King: submitted for the approval of the

Elon Musk: [emerging from bushes] eyyyyy stephano king!

Musk: you still no paya $8 for X?

King: no elon i'm

King: wait

King: $8 for what?

Musk: eyyyyy iss x now!

Musk: cuz x itta do everything!

Musk: it da everything app!

King: what do you mean it'll "do everything?"

Musk: eyyyy you know

Musk: it do

Musk: it do

Musk: it do-a alla da things capiche???

Musk: now you alla post onna da x capiche?

King:

Musk:

King:

Musk: [grappling with King] gimmie da $8!

King: [struggling] no! never! i'm never paying for twitter!

Musk: [struggling] itsa notta twitter! IT'SA X!!!

King: criminy elon why are you so obsessed with the letter x?

Musk: eyyyy itta all start 24 years ago

Musk: 24 years ago dissa very night

Musk: in desa very woods...

[24 years ago]

Young Musk: eyyyy i maka da X dot com! I no paya da taxes! eyyy!!

Peter Thiel: [rising from coffin like count orlock] once again, elon, there is nothing you can possess which i cannot take away

Young Musk: mama mia!!

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opera on YouTube, Part 2

Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro)

Glyndebourne Festival Opera, 1973 (Knut Skram, Ileana Cotrubas, Kiri Te Kanawa, Benjamin Luxon; conducted by John Pritchard; English subtitles)

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle studio film, 1976 (Hermann Prey, Mirella Freni, Kiri Te Kanawa, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; conducted by Karl Böhm; English subtitles) – Acts I and II, Acts III and IV

Tokyo National Theatre, 1980 (Hermann Prey, Lucia Popp, Gundula Janowitz, Bernd Weikl; conducted by Karl Böhm; Japanese subtitles)

Théâtre du Châtelet, 1993 (Bryn Terfel, Alison Hagley, Hillevi Martinpelto, Rodney Gilfry; conducted by John Eliot Gardiner; Italian subtitles)

Glyndebourne Festival Opera, 1994 (Gerald Finley, Alison Hagley, Renée Fleming, Andreas Schmidt; conducted by Bernard Haitink; English subtitles)

Zürich Opera House, 1996 (Carlos Chaussón, Isabel Rey, Eva Mei, Rodney Gilfry; conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt; English subtitles)

Berlin State Opera, 2005 (Lauri Vasar, Anna Prohaska, Dorothea Röschmann, Ildebrando d'Arcangelo; conducted by Gustavo Dudamel; French subtitles)

Salzburg Festival, 2006 (Ildebrando d'Arcangelo, Anna Netrebko, Dorothea Röschmann, Bo Skovhus; conducted by Nikolas Harnoncourt; English subtitles) – Acts I and II, Acts III and IV

Teatro all Scala, 2006 (Ildebrando d'Arcangelo, Diana Damrau, Marcella Orasatti Talamanca, Pietro Spagnoli; conducted by Gérard Korsten; English and Italian subtitles)

Salzburg Festival, 2015 (Adam Plachetka, Martina Janková, Anett Fritsch, Luca Pisaroni; conducted by Dan Ettinger; no subtitles)

Tosca

Carmine Gallone studio film, 1956 (Franca Duval dubbed by Maria Caniglia, Franco Corelli, Afro Poli dubbed by Giangiacomo Guelfi; conducted by Oliviero de Fabritiis; no subtitles)

Gianfranco de Bosio film, 1976 (Raina Kabaivanska, Plácido Domingo, Sherrill Milnes; conducted by Bruno Bartoletti; English subtitles)

Metropolitan Opera, 1978 (Shirley Verrett, Luciano Pavarotti, Cornell MacNeil; conducted by James Conlon; no subtitles)

Arena di Verona, 1984 (Eva Marton, Jaume Aragall, Ingvar Wixell; conducted by Daniel Oren; no subtitles)

Teatro Real de Madrid, 2004 (Daniela Dessí, Fabio Armiliato, Ruggero Raimondi; conducted by Maurizio Benini; English subtitles)

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 2011 (Angela Gheorghiu, Jonas Kaufmann, Bryn Terfel; conducted by Antonio Pappano; English subtitles)

Finnish National Opera, 2018 (Ausrinė Stundytė, Andrea Carè, Tuomas Pursio; conducted by Patrick Fournillier; English subtitles)

Teatro alla Scala 2019 (Anna Netrebko, Francesco Meli, Luca Salsi; conducted by Riccardo Chailly; Hungarian subtitles)

Vienna State Opera, 2019 (Sondra Radvanovsky, Piotr Beczala, Thomas Hampson; conducted by Marco Armiliato; English subtitles)

Ópera de las Palmas, 2024 (Erika Grimaldi, Piotr Beczala, George Gagnidze; conducted by Ramón Tebar; no subtitles)

Don Giovanni

Salzburg Festival, 1954 (Cesare Siepi, Otto Edelmann, Elisabeth Grümmer, Lisa della Casa; conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler; English subtitles)

Giacomo Vaccari studio film, 1960 (Mario Petri, Sesto Bruscantini, Teresa Stich-Randall, Leyla Gencer; conducted by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli; no subtitles)

Salzburg Festival, 1987 (Samuel Ramey, Ferruccio Furlanetto, Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Julia Varady; conducted by Herbert von Karajan; no subtitles)

Teatro alla Scala, 1987 (Thomas Allen, Claudio Desderi, Edita Gruberova, Ann Murray; conducted by Riccardo Muti; English subtitles)

Peter Sellars studio film, 1990 (Eugene Perry, Herbert Perry, Dominique Labelle, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson; conducted by Craig Smith; English subtitles)

Teatro Comunale di Ferrara, 1997 (Simon Keenlyside, Bryn Terfel, Carmela Remigio, Anna Caterina Antonacci; conducted by Claudio Abbado; no subtitles) – Act I, Act II

Zürich Opera, 2000 (Rodney Gilfry, László Polgár, Isabel Rey, Cecilia Bartoli; conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt; English subtitles)

Festival Aix-en-Provence, 2002 (Peter Mattei, Gilles Cachemaille, Alexandra Deshorties, Mirielle Delunsch; conducted by Daniel Harding; no subtitles)

Teatro Real de Madrid, 2006 (Carlos Álvarez, Lorenzo Regazzo, Maria Bayo, Sonia Ganassi; conducted by Victor Pablo Pérez; English subtitles)

Festival Aix-en-Provence, 2017 (Philippe Sly, Nahuel de Pierro, Eleonora Burratto, Isabel Leonard; conducted by Jérémie Rohrer; English subtitles)

Madama Butterfly

Mario Lanfranchi studio film, 1956 (Anna Moffo, Renato Cioni; conducted by Oliviero de Fabritiis; no subtitles)

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle studio film, 1974 (Mirella Freni, Plácido Domingo; conducted by Herbert von Karajan; English subtitles)

New York City Opera, 1982 (Judith Haddon, Jerry Hadley; conducted by Christopher Keene; English subtitles)

Frédéric Mitterand film, 1995 (Ying Huang, Richard Troxell; conducted by James Conlon; English subtitles)

Arena di Verona, 2004 (Fiorenza Cedolins, Marcello Giordani; conducted by Daniel Oren; Spanish subtitles)

Sferisterio Opera Festival, 2009 (Raffaela Angeletti, Massimiliano Pisapia; conducted by Daniele Callegari; no subtitles)

Vienna State Opera, 2017 (Maria José Siri, Murat Karahan; conducted by Jonathan Darlington; no subtitles)

Wichita Grand Opera, 2017 (Yunnie Park, Kirk Dougherty; conducted by Martin Mazik; English subtitles)

Teatro San Carlo, 2019 (Evgenia Muraveva, Saimir Pirgu; conducted by Gabriele Ferro; no subtitles)

Rennes Opera House, 2022 (Karah Son, Angelo Villari; conducted by Rudolf Piehlmayer; French subtitles)

#opera#complete performances#youtube#le nozze di figaro#the marriage of figaro#tosca#don giovanni#madama butterfly#madame butterfly#wolfgang amadeus mozart#giacomo puccini

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

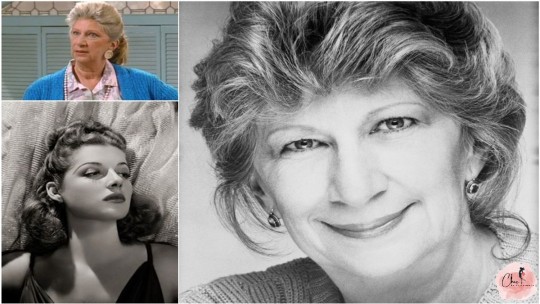

Cosplay the Classics: Nazimova in Salomé (1922)—Part 1

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

The Importance of Being Peter: Nazimova’s Take on Wilde

With over two decades of professional acting experience behind her (six on the “shadow stage” of silent cinema), Alla Nazimova went independent. She was one of the highest paid stars in Hollywood at the start of 1922 when her contract with Metro ended. Almost exclusively using her own savings, Nazimova founded a new production company and immediately got to work on two films that reflected both a deep understanding of her own fan base and a faith in the American filmgoer’s appreciation for art.

Discourse around these films and their productions that have emerged in the century since their release are often peppered with over-simplifications or a lack of perspective. Focus is understandably placed on Salomé, as her first project, A Doll’s House (1922), has not survived. In part one of this series, I plan to contextualize Nazimova’s decision to commit Wilde’s drama to celluloid and examine the details of the adaptation. Then, in part two, I will cover how Salomé (and A Doll’s House) fits into the industry trends and the emergent studio system in the early 1920s.

While the full essay and more photos are available below the jump, you may find it easier to read (formatting-wise) on the wordpress site. Either way, I hope you enjoy the read!

Wilde’s Salomé: The Basics

Salomé was a one-act drama written by Oscar Wilde. In a creative challenge to himself, Salomé was one of Wilde’s first plays and he chose to write in French, which he did not have as complete a mastery of as of English. Wilde was directly inspired by the Flaubert story “Herodias,” which was, in turn, inspired by the short story which appears twice in the New Testament. The play was later translated into English and published with illustrations by artist Aubrey Beardsley. Wilde’s play was the basis of the opera of the same name by Richard Strauss. While both the opera and the play had been staged numerous times across Europe and in New York before Nazimova’s adaptation, Strauss’ opera was the main reference point for the story in the popular imagination of the time. The success of Strauss’ opera led to the popularization of the Dance of the Seven Veils and the accepted interpretation of the character as a classic femme fatale.

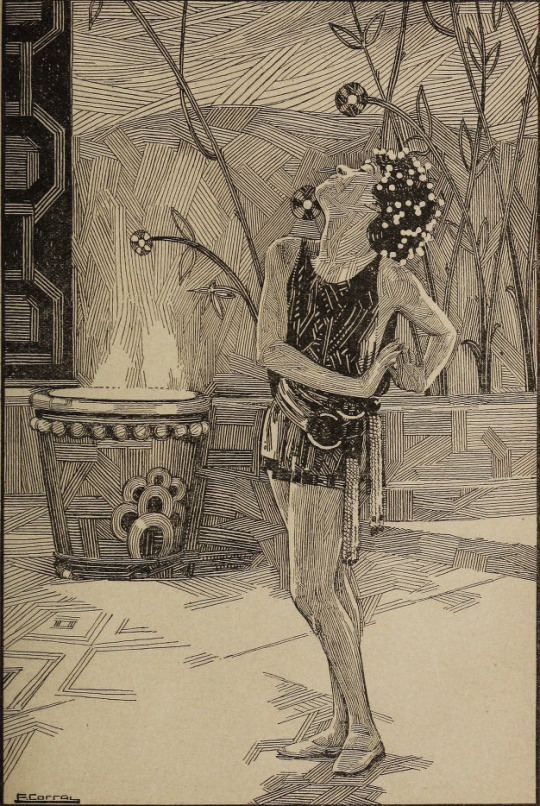

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

Nazimova’s Salomé: The Basics

When Nazimova announced her production of Salomé, she did so assured that she and Natacha Rambova, her art director, had a unique and creatively compelling interpretation of the story to warrant adaptation. Nazimova was not only the star and producer of Salomé, she adapted it from its source herself under her pen name Peter M. Winters. (Cheekily, contemporary interviews and profiles joke that “Peter” is one of her common nicknames.) Charles Bryant, credited as director, was as much the director of the film as he was Nazimova’s husband, which is to say, he is not known to have contributed much at all. It’s now accepted fact that Bryant acted as a professional beard (Bryant and Nazimova were also never legally married). The choice to credit Bryant was to offset the heat Nazimova was getting in the press at the time for “taking on too much.” Having Bryant’s name in the credits was a protective measure. Charles Van Enger was a talented, up-and-coming cinematographer who had been recommended to Nazimova following the inadequate cinematography of her Metro films.

Rambova was in charge of the art direction, set designs, costumes, and makeup. Nazimova and Rambova had become close artistic collaborators after Nazimova hired Rambova to design the fantasy sequence for her film Billions (1920, presumed lost). [You can learn more about Rambova’s career here.] Both women valued their work above all else. Both were convinced that film could be art. Both had the gumption to believe that they could make a lasting mark on cinema’s recognition as a legitimate medium of artistic expression.* (Spoiler: even though Salomé was not an unqualified box-office success, they were right.)

Photo of the Salomé crew from Exhibitors Herald, 29 April 1922. Original caption: Nazimova ordered this picture taken that she might be reminded of the real pleasure encountered in every stage of the production of “Salome.” Top, left to right: Monroe Bennett, laboratory; Charles Bryant, director; Mildred Early, secretary; John DePalma, assistant director. Second row: Sam Zimbalist, cutter; Natacha Rambova, art director; Charles J. Van Enger, cameraman; the star; R. W. McFarland, manager. Front row: Neal Jack, electrician; Paul Ivano, cameraman; Lewis Wilson, cameraman.

Nazimova’s independence was at least partly spurred on by feeling creatively bereft from her work at Metro. In a 1926 interview with Adela Rogers St. Johns, Nazimova said:

“You asked me why I made ‘Salome.’ Well—’Salome’ was a purgative. […] It seems impossible now that I should ever have been asked to play such parts as ‘The Heart of a Child’ and ‘Billions.’ But I was. And instead of saying, ‘No. I will not play such trash. I will not play roles so wholely [sic] unsuited to me in every way,’ I went on and played them because of my contract, and they ruined me.

“WORSE than that, they [made] me sick with myself. So I did ‘Salome’ as a purgative. I wanted something so different, so fanciful, so artistic, that it would take the taste out of my mouth. ‘Salome’ was my protest against cheap realism. Maybe it was a mistake. But—I had to do it. It was not a mistake for me, myself.”

Given that Nazimova now had full creative freedom, outside of the confines of the Hollywood film factory, why were A Doll’s House and Salomé the first works she gravitated towards?

Initially, Nazimova had conceived of a “repertoire” concept for her productions: one shorter production (A Doll’s House) and one feature-length production (Salomé), which could be distributed and exhibited together. Once production was underway for ADH, Nazimova instead chose to make it a feature. The reasons for this decision that I found in contemporary sources are purely creative, but I don’t think it’s too much of a presumption that this may have been a financial choice, as profits from ADH (which unfortunately wouldn’t materialize—more on that in part two!) could have been cycled into Salomé’s production.

Ibsen was not popular source material for the silent screen, but Nazimova’s name and career was forever tied to the playwright as she is considered the actress who brought Ibsen to the US. (Minnie Maddern Fiske starred in a production of Hedda Gabbler in the US before Nazimova, however it failed to raise the profile of the writer.) Nazimova’s stage productions of Ibsen’s work proved that there was an audience for it in the US—both in New York and on tour. Superficially, ADH might seem like a risky proposition, but Nazimova had good reason to believe it had both artistic and box office potential. (Again, I’ll delve into why it might not have found its audience in part two.)

Nazimova as Nora in A Doll’s House

Though ADH is now lost, we know from surviving materials that Nazimova understood that by 1922 The New Woman archetype was already becoming passé to the post-war/post-pandemic generation of young women. Nazimova endeavored to translate the play in a way that would resonate with 1920s American womanhood. (How well she succeeded is lost to time unless we are lucky enough to recover a copy of the film.) Likewise, Nazimova approached her adaptation of Salomé with a keen eye for the concerns of modern independent women.

——— ——— ———

*Incidentally, both women also had a personal connection to Wilde. Nazimova was a close friend and colleague of Elizabeth Marbury, who worked as Wilde’s agent. Rambova spent summers at her aunt’s (Elsie de Wolfe) villa in France where she lived with her longtime partner, Marbury.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

The Adolescence of Salome

In the decade following the end of the First World War, there was a great cultural shift for women in America, who experienced and pursued greater independence in society—particularly young and/or unmarried women. This quality was emblematized in the Flappers and the Jazz Babies, but even women who didn’t participate in these subcultures lived lifestyles removed from “home and family” ideals of the past. The lifestyle change was mirrored aesthetically. As Frederick Lewis Allen describes in Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s:

“These changes in fashion—the short skirt, the boyish form, the straight, long-waisted dresses, the frank use of paint—were signs of a real change in the American feminine ideal (as well, perhaps, as in men’s idea of what was the feminine ideal). […] the quest of slenderness, the flattening of the breasts, the vogue of short skirts (even when short skirts still suggested the appearance of a little girl), the juvenile effect of the long waist,—all were signs that, consciously or unconsciously, the women of this decade worshiped not merely youth, but unripened youth […] Youth was their pattern, but not youthful innocence: the adolescent whom they imitated was a hard-boiled adolescent, who thought not in terms of romantic love, but in terms of sex, and who made herself desirable not by that sly art that conceals art, but frankly and openly.”*

Allen’s summary of youthful womanhood in the 1920s resounds so clearly in the character design and performance of Nazimova’s Salomé, it’s apparent that she and Rambova were thoroughly informed by contemporary trends around young/independent women. Belén Ruiz Garrido puts it succinctly in her great essay on the film “Besare tu boca, Iokanaan. Arte y experiencia cinematografica en Salomé de Alla Nazimova:”

“Las concomitancias con la flapper o la it girl de los felices años veinte son evidentes. Se muestra mimosa, pero su seducción es como un juego de niña. / The similarities with the flapper or the it girl of the roaring twenties are obvious. She performs affection, but her seduction is like child’s play.” (translation mine)

Nazimova was also fully conscious that her fanbase was predominantly female and that she held significant appeal for younger women. From the moment she signed her first American theatrical contract with Lee Shubert, Nazimova’s status as a queer idol was already being established.

“The women… were enthusiastic about [Nazimova]… [At the hotel, the] ladies’ entrance was always crowded with women waiting for her to return from the theatre. It is much better that she should be exclusive and meet no one if possible. They regard her as a mystery. And there are other damned good reasons besides this one.” – citation: A. H. Canby to Lee Shubert, December 29, 1908**

While women, particularly middle-class women, were emerging as a prominent consumer group in the US, Nazimova’s popularity peaked on stage and on screen. Arriving in Hollywood, Nazimova also continued her trend of surrounding herself socially and professionally with other queer women. Profiles and interviews of Nazimova in the Hollywood press often contained coded language about her queerness as a wink and nudge, usually but not always accompanied by mention of her “husband” Charles Bryant.

This well-developed understanding of her primary fanbase led her to break from popular presentations of the character as an embodiment of monstrous feminine sensuality. Instead, Nazimova chose to present the character as an adolescent. While Nazimova was the first to put this read on the character on film, Marcella Craft chose an adolescent interpretation in a production Strauss’ opera in Munich and Hedwig Reicher was a teenager when she assayed the role and played it accordingly (also in Germany). (Maybe not insignificantly, Reicher was also working in Hollywood at the time of Salomé’s production.)***

This is the American pop culture landscape we’re talking about here, so of course women’s independence was rapidly codified for capitalization. Young women were moralized at for not conforming to traditional gender roles while simultaneously being framed as sexually desirable in order to sell consumer goods (including motion pictures!). The American way. It’s hard to not see social commentary in Nazimova’s reworking of this icon of wanton femininity for a new generation.

This isn’t to suggest that Nazimova’s Salomé glorifies the character, but rather that making Salomé a teen adds layers of complexity to the production. Considering it in conversation with her predecessors, Salomé isn’t even named in the New Testament stories. Flaubert built out the character with 19th century concerns in mind (though his story is more about Herod & Herodias) and Wilde shifted even more focus to Salomé. Nazimova continued that trend with her version of Salomé—an impetuous child too young and ill-equipped to constructively deal with the horrible environment she was brought up in. (Might that resonate with a generation of young people disillusioned by a World War and a pandemic?)

As Nazimova/Peter wrote in the opening intertitles to the film:

“It is at this point that the drama opens, revealing Salome who yet remains an uncontaminated blossom in a wilderness of evil.

“Though still innocent, Salome is a true daughter of her day, heiress to its passions and its cruelties. She kills the thing she loves; she loves the thing she kills, yet in her soul there shines the glimmer of the Light and she sets forth gladly into the Unknown to solve the puzzle of her own words——”

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

As Salomé was an experiment in pantomime for screen acting, it’s worthwhile to look at how Nazimova embodies this image of youth in her performance. In the first scenes, Salomé’s facial expressions are pouty and her movements like a bored child’s. Her wig emphasizes every movement she makes with a flurry of pearls and creates a neotenous silhouette for the character. When denied access to Jokanaan, her facial expressions are imperious, but the imperiousness of a spoiled child. She swings on the bars imprisoning Jokanaan as if they are a jungle gym. As she “charms” Narraboth, her expressions and body language shift toward a scheming energy with barely concealed artifice, displaying a distinct lack of sophistication—like she’s trying to angle a second serving of ice cream not exacting a favor of a servant that could cost his life.

Perhaps most crucially, Salomé’s adolescence emphasizes the inappropriateness of men’s gaze upon her. Wilde’s drama is built around rhythmic repetition in the dialogue—a key repetition being the act of looking. Though the play is only one act, some form of “regarder” in relation to Salomé is repeated nineteen times—most often in some form of “don’t look at her” or “you shouldn’t look at her that way.” As Salomé is a silent film, to repeat this in intertitles nineteen times in intertitles would be absurd. Throughout the film, frequent close ups are strategically employed to visually recreate the rhythmic emphasis on gazing. (The purpose of this device seems to have been lost on one reviewer for Exhibitors Herald who said in his review: ”too many close ups.”) Additionally, the motif is foregrounded by front-loading the mentions of looking. As soon as the opening narration ends, we’re introduced to Herod behaving lecherously toward Salomé and Herodias telling him not to look at her. The perversity of Herod is amplified here because Salomé is not only his niece and his step-daughter, but also a child. This scene is followed by Narraboth and the page having a similar interaction, albeit with a different tone.

As Nazimova put it herself in a profile in Close-Up magazine:

“The men about her are obnoxious; they cannot even look upon her decently. She loathes them all. Even the Syrian [Narraboth] whose approach is of all the most respectful and decorous, is of his times and his love is tempered with the alloy of lust.”

In the film, Salomé’s rage against Herod is justified, and her rage against Jokanaan is a raw confusion of emotions—she doesn’t have the capacity to act constructively. When the first unfortunate man commits suicide over her, she barely takes notice, establishing Salome’s blasé attitude toward death. When the second man takes his life this time directly in front of her, Salomé only notices after almost tripping on his body. Her response is giving the body an annoyed kick for tripping her! The key phrase of the drama is “The mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.” Salomé is surrounded by death, enveloped by it, but love (of any kind) is unknown to her until Jokanaan. So, when her love of Jokanaan is rebuked, she reverts to the only response that has been nurtured into her: death.

Nazimova’s Salomé is a perfect surviving example of a quality of her acting described in an uncredited review of Nazimova’s theatrical work:

“If the actress you’re seeing knows what she’s saying but you don’t, it’s Mrs. [Minnie Maddern] Fiske. But if the actress doesn’t know what she is saying and you do, it’s Alla Nazimova.”****

We as viewers understand what Salomé is going through, but she is being psychologically buffeted by fate and circumstance without ever comprehending the nature of it. The tumultuous feelings brought on by Salomé’s first brush with the spiritual (rather than the sexual), launches her into an accelerated ripening of her cruelty. This is masterfully communicated by Nazimova through facial expression and body language and accentuated by Rambova’s costuming.

As Herman Weinberg put it in his essay “The Function of the Actor:”

“The true film crystalizes action for us. ‘To see eternity in a grain of sand,’ the poet said. ‘To see a life cycle in an hour and a half’ is the modern screen parallel.”

Because of the emotional scale of Nazimova’s performance in Salomé, it has been variously described as “bizarre” or “grotesque”—though not always said derogatorily. That’s on point, as Nazimova’s performance is only one expression of her protest against realism in the film.

——— ——— ———

*If you’re interested in the 1920s at all, I highly recommend Allen’s book. The section this quote is from has a detailed survey of changes in American women’s lifestyles throughout the 1920s.

**as quoted in “Alla Nazimova: ‘The Witch of Makeup’” by Robert A. Schanke

***Gavin Lambert’s biography of Nazimova intimates that she referenced the 1917 Tairov production of Wilde’s Salomé, which she reportedly had a detailed description of. Reading about the production for myself in Mark Slonim’s Russian Theatre: from the Empire to the Soviets, I’m not sure what precisely she would have drawn from this production. It doesn’t seem to have much in common with the ‘22 film at all. That said, in a 1923 interview with Malcolm H. Oettinger in Picture-Play Magazine, Nazimova admits that in preparing for the film, she compiled a large scrapbook of previous productions and artistic interpretations of the story and character. Unfortunately, though Lambert clearly did voluminous research for his biography, his presentation and interpretation leaves a lot to be desired. Most of the things I tried to verify or try to find more information on from the book proved to be misrepresentations or were factually incorrect. So, I’m avoiding quoting Lambert without verification, unless what I’m citing is directly taken from a primary source; like a quote from Nazimova’s correspondence.

****quotation is from an uncredited clipping held by the Nazimova archive in Columbus, Georgia as quoted in Gavin Lambert’s biography

Illustration of Nazimova as Salomé by F. Corral from The Story World, March 1923

Nazimova and Rambova’s Modernist Phantasy

The assurance that Rambova and Nazimova felt that they had something new to bring to Salomé was obviously not solely founded in a character interpretation updated for the screen and for the decade. The two crafted a singular work born of pastiche in a manner that genuinely had not been done before in the American film industry. It’s often repeated that Salomé is America’s first art film. This may have its origin in promotional materials* made for the initial release of the film. Before the film’s official release, Bryant, Nazimova, and Paul Ivano (assistant camera & Nazimova’s on-again-off-again lover) arranged preview screenings and a few reviews from those screenings mention in some form that Salomé was a direct retort to the notion that art cannot be made with a camera.

What constituted the Nazimova/Rambova strategy to elevate film to the status of art? Both women had around six years of experience working in film (twelve collectively), but both came from a live performance background—theatrical acting and ballet respectively. Salomé is a film based on a stage play (though not strictly based on any one production of that play). Salomé inherits its symbology (first and foremost the moon) from its source material, but the filmmakers found creative ways of communicating and remixing symbols for the camera. The art design is inspired by Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for a printed edition of the play, though Rambova pulled more broadly from art-nouveau to devise designs that are in no way unoriginal.

As for the much discussed Dance of the Seven Veils, in my opinion, Nazimova’s execution is inspired by the dance described in Flaubert’s “Herodias” rather than a previous live performance.

“Again the dancer paused; then, like a flash, she threw herself upon the palms of her hands, while her feet rose straight up into the air. In this bizarre pose she moved about upon the floor like a gigantic beetle; then stood motionless.

“The nape of her neck formed a right angle with her vertebrae. The full silken skirts of pale hues that enveloped her limbs when she stood erect, now fell to her shoulders and surrounded her face like a rainbow. Her lips were tinted a deep crimson, her arched eyebrows were black as jet, her glowing eyes had an almost terrible radiance; and the tiny drops of perspiration on her forehead looked like dew upon white marble.”

Clearly, I’m not implying that what’s described above is exactly what we see on screen. My thought instead is that Nazimova may have drawn inspiration for the dance to be provocative in an uncanny way instead of provocative in a conventionally sensuous way. What we do see on screen is a distinct lack of practiced sensuality and an element of menace. The former comes both from Salomé’s youthfulness and from the logic that, as Salomé has already gotten Herod to give her his word in front of dignitaries, there’s no need for seduction. The latter is brought on by the expression of Salomé’s fractured emotional state and feelings about Herod. In execution, the use of close-ups again serves a major purpose. Intercutting close-up reactions from those gathered at the court provides a crescendo to the motif of looking, which is then pivotally reversed in the kiss scene. Cutting to close-ups of Salomé’s face accents the ecstatic and maniacal quality of the dance. Together this variation of shots creates an effect that could only work on film.

Salomé has a significant appreciation for its non-cinematic antecedents, but filtered through the prism of Nazimova’s and Rambova’s own creative strengths and sensibilities—a melding of theater and graphic art into something not only fresh but also totally cinematic.

It speaks to their filmmaking skill that all of these ideas and influences do in fact come together as a cohesive yet wholly unconventional film. Some critics of Salomé (both contemporary and modern) will cite vague notions of theatricality, or state that the film is only a series of tableaux, or that the limited sets don’t depart enough from a stage presentation. Art is in the eye of the beholder, but I think whether those specific elements preclude Salomé from being cinematic is a matter of perspective.

The oversized, stylized nature of Salomé’ssets might at first register as theatrical, but those same sets also serve to amp up the anti-real nature of the film. It’s uncharitable to Rambova to suggest that this artificiality was not a conscious artistic decision. If you have seen the sequences she designed with Mitchell Leisen for De Mille’s Forbidden Fruit (1921) then you have seen her demonstrated understanding of how designs register on camera. The gorgeously executed lighting effects in Salomé that are employed to to sublimate tone shifts could feasibly be recreated in a theatrical setting, here, filtered through the camera of Van Enger, register as thoroughly cinematic.

To once again quote “The Function of the Actor” by Weinberg:

“In nine movies out of ten (most particularly those emanating from the film factories of Hollywood), the actors stand around and talk to each other, relieved only by periodic bursts of someone going in or out of a doorway. (Sixty percent of the action in the average Hollywood movie consists of people going in and out of doors.) […]

“The actor going through a doorway may be a necessary device on the stage, to get him on and off. But Pudovkin has made a neat distinction between the realities of stage and screen: ‘The film assembles the elements of reality to build from them a new reality proper to itself; and the laws of time and space that, in sets and footage of the stage are fixed and fast, are in the film entirely altered.’ On the stage, that is, an event seems to occur in the same length of time it would occupy in life. On the screen, however, the camera records only the significant parts of the event, and so the filmic time is shorter than the real time of the event.”

Weinberg cites Pudovkin in an amusing but illustrative way here. People may throw “overly theatrical” or “stagey” casually, but more often than not the distinction between theatrical/cinematic comes down to how space and time is traversed. Even if the base material, a narrative drama for example, is shared between stage and screen, there should be a thoughtful construction of geography and chronology. Could Salomé have played more creatively with space? Perhaps. But, for a film made in early 1922, its creative geography isn’t all that uninventive. The majority of the action in Salomé takes place exclusively on one set, so it does rely a lot on the types of comings and goings that Weinberg identifies with theatre. That said, there are some comings and goings that forcefully pull the audience away from the feeling of stagey-ness. The most consequential occurs in the scene with the first suicide, which I previously mentioned in the context of developing Salomé‘s character and environment. The man runs to the ledge of the courtyard, beholds the moon, and leaps. Cut to a wide, back-lit shot of the figure plunging to nowhere, establishing that the city above the clouds depicted in the art titles and opening credits is the actual physical location that film is taking place in. It’s a genuinely startling moment in the film and Salomé’s most evocative use of creative geography.

The majority of legitimate critical appraisal at the time of Salomé’s release recognize it as an achievement in film art, even highlighting artsiness as a potential selling point. As art cinemas started popping up in the US, Salomé stayed in circulation. Appreciation grew. Legends emerged around its production. And, now one hundred years later, it’s safe to say that Salomé has earned and kept its place as a fixture of the history of film art. As we are lucky enough to have the complete film to watch, assess, reassess, and debate its qualities as a work of cinematic art, I’m positive that conversation on Salomé will continue.

So, if Salomé was appreciated in its time, why did it ruin and bankrupt Nazimova? What was going on in the American film industry at the time? Find out in part two!

“If we have made something fine, something lasting, it is enough. The commercial end of it does not interest me at all. I hate it. This I do know: we must live, and I must live well. I have suffered—enough. Never again shall I suffer. But most of all am I concerned in creating something that will lift us all above this petty level of earthly things. My work is my god. I want to build what I know is fine, what I feel calling for expression. I must be true to my ideals—”

— Nazimova on Salomé quoted in “The Complete Artiste” by Malcolm Oettinger

——— ——— ———

*As of the time of writing, I haven’t been able to track down a complete copy for the campaign book for the film, so I’m relying on fragments, quotes, and second-hand references to its content.

——— ——— ———

Read Part Two Here

——— ——— ———

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

——— ——— ———

Bibliography/Further Reading

(This isn’t an exhaustive list, but covers what’s most relevant to the essay above!)

Salomé by Oscar Wilde [French/English]

“Herodias” by Gustave Flaubert [English]

Cosplay the Classics: Natacha Rambova

Lost, but Not Forgotten: A Doll’s House (1922)

“Temperament? Certainly, says Nazimova” by Adela Rogers St. Johns in Photoplay, October 1926

“Newspaper Opinions” in The Film Daily, 3 January 1923

“Splendid Production Values But No Kick in Nazimova’s “Salome” in The Film Daily, 7 January 1923

“SALOME” in The Story World, March 1923

“SALOME’ —Class AA” from Screen Opinions, 15 February 1923

“The Complete Artiste” by Malcolm H. Oettinger in Picture-Play Magazine, April 1923

“Famous Salomes” by Willard H. Wright in Motion Picture Classic, October 1922

“Nazimova’s ‘Salome’” by Walter Anthony in Closeup, 5 January 1923

“Alla Nazimova: ‘The Witch of Makeup’” by Robert A. Schanke in Passing Performances: Queer Readings of Leading Players in American Theater History

“Besare tu boca, Iokanaan. Arte y experiencia cinematografica en Salome de Alla Nazimova” by Belén Ruiz Garrido (Wish I had read this at the beginning of my research and writing instead of near the end as it touches upon a few of the same points as my essay! Highly recommended!)

“The Function of the Actor” by Herman Weinberg

“‘Out Salomeing Salome’: Dance, The New Woman, and Fan Magazine Orientalism” by Gaylyn Studlar in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film

Nazimova: A Biography by Gavin Lambert (Note: I do not recommend this without caveat even though it’s the only monograph biography of Nazimova. Lambert did a commendable amount of research but his presentation of that research is ruined by misrepresentations, factual errors, and a general tendency to make unfounded assumptions about Nazimova’s motivations and personal feelings.)

Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s by Frederick Lewis Allen

Russian Theatre: from the Empire to the Soviets by Mark Slonim

#1920s#1922#1923#Nazimova#alla nazimova#natacha rambova#cosplay#fan art#Salome#Oscar Wilde#film history#independent film#silent cinema#classic cinema#film#american film#queer cinema#women filmmakers#queer#cosplay the classics#queer film#cinema#women directors#classic film#classic movies#silent film#my gifs#silent movies#silent era#history

33 notes

·

View notes