#amerindian people in history

Text

LOS OTROS LIBERTADORES is an 8 episode mini-series that dramatizes the lives of the heroes who played key roles in the Peruvian War of Independence (1811 - 1828). In two episodes, we have the famous Tupac Amaru II, María Bellido, and María Parado de Bellido (Andean indigenous people in history) dipected by Andean Actors. This is groundbreaking for Andean actors, as Latin America is still racist towards its indignous people.

More stills of the drama is below:

#Andean figures in history#Andean history#Peruvian history#andean indigenous historical figures#ndn history#native south american history#native american history#amerindian people in history#peruvian independence day#peruvian independence#andinos#peruanos#indigenous peruvians#Tupac Amaru II#Micaela Bastidas#María Parado de Bellido#Magaly Solier#Christian Esquivel#Francesca Vargas#native history#native people from history#history post#ndn tumblr#andean tumblr#period drama#native to south america#native actors#support native actors#indignous actors#BIPOC actors

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#Youtube#alternative history#original history#story sharing#first peoples#native american#Amerindians

0 notes

Text

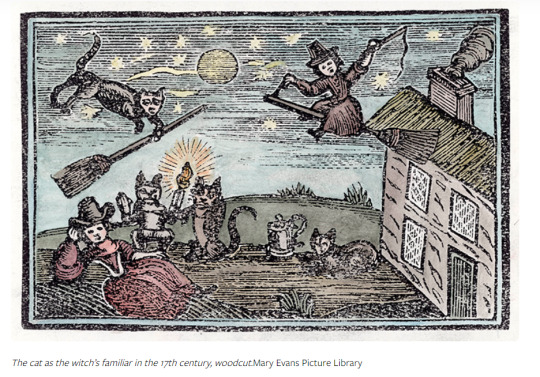

I love this. I posted a little about this before, but wanted to expand. Women's history fact of the day:

Women of the Neolithic era in particular loved keeping pets and it was common for them to trap small animals - such as cats - and adopted as pets.

In the Amazon region, where hunting and gathering and subsistence horticulture is still practiced by a handful of surviving Amerindian groups, hunters commonly capture young wild animals and take them home where they are then adopted as pets, usually – although not invariably – by women.

There's a theory that cats may have domesticated themselves by being attracted to human villages that produced grain and seeds and attracted rodents, and then the bolder cat clans survived under natural selection. Or, alternatively, women domesticated cats.

Based on these sorts of observations, it could be argued that the domestication of F.s. libyca occurred where and when it did because tamed wildcats were already an integral feature of village life as a result of people actively adopting, hand-rearing and socialising young wildcats to keep as pets

The relationship between cats and women stretch back since the stone age. They were burned with us during the witch trials (rabbits commonly too!), suffered from abuse and treated as property with us by men ambivalent to us under religions such as Christianity, were associated as us within medieval folklore and as a metaphor for female sexuality and anatomy ("pussy"), and continue to be associated with us today.

Women's independence from man is derogatorily associated with cats ("crazy cat lady"), a nod to female (and feline) separatism. It's tendency to groom itself frequently was also associated with cleanliness and domesticity, and it was frequently used in posters by anti-suffragettes symbolically to denote that women were simple and delicate, that women's suffrage was as absurd as cat suffrage. Some suffragettes took back the meaning of the cat, adopting a (black!) cat named Saxon as their official mascot.

They survived male oppression throughout history, for thousands of years, right beside us and within our arms.

#cats#cat appreciation post#cat history#women's history#women and cats#kitties#witch trials#witchcraft#human history#evolution

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

History Blog recs

One of my Very Specific interests over the last...idk 10 years, has been reading blogs about the A Song of Ice and Fire series, by historians. I'm not sure what it is about those books: the complex, multi-layered narrative, the author's claim to work creatively with real world history, the micro-arguments contained in every arc, or what, but historians have the most FASCINATING shit to say about those books.*

I've learned so much about the logistics of civilization, the intellectual history of leadership theory, the history of subsistence agriculture, the type of agriculture needed to sustain societies of a certain size, the evolution of military theory, etc from this very specific, Historians Engage With ASOIAF and its Television Adaptations genre of blog.

There is, of course, the late great Steven Attewell's @racefortheironthrone, but I recently discovered this gem: A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry by Dr. Bret C. Devereaux. I just finished his series analyzing, problematizing, and ultimately debunking George RR Martin's claim that the Dothraki "were actually fashioned as an amalgam of a number of steppe and plains cultures… Mongols and Huns, certainly, but also Alans, Sioux, Cheyenne, and various other Amerindian tribes… seasoned with a dash of pure fantasy."

In Part IV, he writes:

... declaring that the Dothraki really do reflect the real world (I cannot stress that enough) cultures of the Plains Native Americans or Eurasian Steppe Nomads is not merely a lie, but it is an irresponsible lie that can do real harm to real people in the real world. And that irresponsible lie has been accepted by Martin’s fans; he has done a grave disservice to his own fans by lying to them in this way. And of course the worst of it is that the lie – backed by the vast apparatus that is HBO prestige television – will have more reach and more enduring influence than this or any number of historical ‘debunking’ essays. It will befuddle the valiant efforts of teachers in their classrooms (and yes, I frequently encounter students hindered by bad pop-pseudo-history they believe to be true; it is often devilishly hard to get students to leave those preconceptions behind), it will plague efforts to educate the public about these cultures of their histories. And it will probably, in the long run, hurt the real descendants of nomads.

Which just. I LOVE EVERYTHING ABOUT IT. Y'all know how deeply concerned I am a. with the outsize influence the entertainment industry has on memory; and b. how little that industry gives a shit about responsible use of its own power. So like, this is my shit. I'm still exploring this blog and it is a TREASURE TROVE.

*I do not include myself in that grouping. My thoughts are like: BUT WHICH ONES ARE THE JEWS DANY IS MY UNPROBLEMATIC QWEEN/AZOR AHAI/PRINCE THAT WAS PROMISED/STALLION THAT'S GONNA MOUNT THE WORLD/ETC I CAN'T WAIT TIL SANSA SHOWS HERSELF IS DANY GONNA BURN IT ALL DOWN AND EMERGE FROM THE FLAMES LIKE THAT ELMO GIF IS ARYA GOING TO RIDE A WOLF WOW I DON'T CARE ABOUT BRAN I THINK THE RHOYNAR ARE THE JEWS WHERE IS THE GODDAMN FUCKING WINDS OF WINTER

**Also, I never watched more than 2 episodes of the show. I hated how it added in sexual violence and nudity for no reason when there was already PLENTY of that in the text, most of it with narrative purpose. But then I read the books because it was 2012 and I wanted to keep up with pop culture.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

[W]hat counted as knowledge? [...] [In] British plantation societies from the Chesapeake to the Caribbean [...] [there was a] “process by which authorship is attributed to matters of fact.” [...] Although colonial naturalists drew upon European models and ideas, the plantation societies of the Atlantic were far removed from the [...] [social] world of London gentlemen. [...] [W]hile metropolitan propaganda would seem to preclude the possibility of free and enslaved blacks, Native Americans, women, and even white colonial men as reliable testifiers, in practice European science depended upon such informants. Enslaved and free blacks and Amerindians were seen as both uniquely knowledgeable about the natural world and potentially dangerous as a result of this knowledge. Colonials [white people in the colony] therefore served as buffer zones ‘‘between the metropolitan place of knowledge ratification and the volatile site of exotic secrets.’’ [...] While colonials acknowledged the authority of their black and indigenous informants as experts about American nature, they represented such expertise as merely the raw materials out of which they fashioned new natural knowledge. [...] Colonial naturalists suggested that it required their verification and experimentation to transform the local expertise of their informants into stable, universal knowledge suitable for European audiences. By translating local knowledge into a universal register, colonials laid claim to the status of authors of new knowledge about American nature. [...]

---

The Maryland physician Richard Brooke was no stranger to the transatlantic circuits of natural history. In 1762, the physician sent the Society of Arts a sample of a tea made from the ‘‘red-root’’ shrub that, he promised, could take the place of Chinese tea while providing additional health benefits. This letter was part of a series of missives that Brooke contributed to metropolitan societies and publications describing New World nature, letters that built his transatlantic reputation as a curious gentleman. [...] Brooke claimed that the tea provided ‘‘wonderful Relief in obstinate Coughs,’’ ‘‘raise[d] the Spirits in vapourish People, and occasion[ed] better rest.’’ The physician reported that he learned of this tea from an unnamed Native American 20 years earlier, but he characterized himself as ‘‘the first and only Person who ever prepared this tea.’’ Personhood, in this case, seemed only to have applied to Europeans or Euro-Americans. By disregarding the personhood of the Native American who first shared the remedy with him, Brooke simultaneously highlighted the indigenous source of his knowledge claim and proclaimed himself as author of it. Asserting the right to name the tea as the ‘‘first’’ person to discover it, Brooke ‘‘has taken the Liberty to call it Mattapany, which is the Indian name of the Place where he was born.’’

He added that if his tea should prove popular with ‘‘the ladies in England,’’ it would give him ‘‘great Pleasure to think that Mattapany will frequently be pronounced by the prettiest lips in the Universe.’’ The term ‘‘Mattapany’’ primarily highlighted Brooke’s personal history, rather than memorializing the Native American who revealed the virtues of the root. [...]

Brooke’s letter regarding Mattapany tea is useful for thinking about authority, authorship, and vernacular knowledge in British plantation societies. Brooke did not deny the indigenous source of the natural knowledge that he reported to the Society of Arts; to the contrary, he highlighted its origins. But while the physician recognized the authority of his unnamed indigenous informant to understand the natural properties of the red-root, he did not represent the Native American as the individual who should be credited for the introduction of this new knowledge claim. Instead, Brooke placed himself in the role of author. He did so by verifying its efficacy, reporting it to the London society, and providing samples of the shrub so that the society’s members could test the tea for themselves. Brooke thereby transformed local American knowledge into a form that his European audience would have seen as acceptable, stable, and even universal. [...]

---

[T]he authority of Amerindians and blacks regarding New World nature was critical to the success of British plantation societies. Colonists relied on the expertise of Amerindians and free and enslaved blacks to tend fields, heal the sick, serve as pathfinders and guides, navigate local waterways, prepare food, and perform a host of other duties that relied on detailed local knowledge about the natural world. Knowledge of the medicinal and culinary properties of local plants, in particular, was a practical necessity. Enslaved Africans adapted their rich heritage of herbalism and healing [...]. The success of plantations relied on the appropriation of both the labor and the specialized agricultural knowledge of enslaved Africans [...]. From the rice field to the sick room, the authority of Amerindians and free and enslaved blacks to speak locally as experts about American nature was reaffirmed daily. [...]

Yet it was quite another thing to be represented as the author of new scientific knowledge before a European audience. [...] Rather than being antiauthors who left almost no trace in published accounts, black and indigenous informants’ presence in colonials’ publications and correspondence lent epistemological authority to their texts. As Parrish has argued, some claims even required indigenous or African origins in order for them to be credible. That colonial naturalists relied on a person of Amerindian or African descent is made clear in their various texts, yet the identity of the particular informant was rarely provided. [...] Historians of science have noted the importance of identity for establishing the credibility of claims in early modern natural philosophy. The Royal Society, for example, included the names of the gentlemen who witnessed an experiment, trusting that the credibility of the individual gentlemen would translate into credibility for the experiment [...]. Slaves and Indians did not, therefore, appear in naturalists’ texts as fellow claimants or as independent authors of new knowledge. Rather, they appeared as necessary components of white naturalists’ credibility -- in essence, instruments of their knowledge creation. [...]

Colonials positioned themselves as not merely the brokers or go-betweens of American natural knowledge, but as alchemists of sorts, turning the base materials of local knowledge into something more precious.

---

All text above by: Kathleen S. Murphy. “Translating the vernacular: Indigenous and African knowledge in the eighteenth-century British Atlantic.” Atlantic Studies Volume 8, Issue 1, pages 29-48. March 2011. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

(via) This paper (preprint) essentially argues that the Indo-European expansion into Europe was accompanied by zoonotic plagues which arose in the Steppe, to which the IEs were adjusted (gently, via "long-term continuous exposure") and the Early European Farmers (the neolithic inhabitants of Europe) were not. They analogize this to the plagues which afflicted the Americas after the arrival of Europeans, correlating it with "increased genetic turnover" (population replacement) in Europe.

(So, two instances of Indo-Europeans conquering a continent in the wake of apocalyptic plagues. Which isn't a lot, but it's weird that it happened twice.)

Their method is to check for microbial DNA in samples of human remains. What they demonstrate, afaict, is:

a) Zoonotic diseases first appeared around the time of the IE migrations, being first detected in samples from 6,500 BP and peaking around 5,000 BP.

b) IEs are consistently more likely to be infected with zoonotic diseases than non-IEs. (This greater incidence of infection seems to persist throughout the period.) This "suggests that the cultural practices and living conditions of the former might have been more conducive to the emergence of novel zoonotic pathogens." (14)

So they don't directly demonstrate that EEFs were ultimately hit harder by these illnesses, they just say that it would make sense for IEs to have adapted to them. As far as I can tell, this is fair; they cite a paper which claims that increased disease pressure may have resulted in adaptations to multiple sclerosis in the Steppe and another which suggests a similar trend among Amerindians after the Columbian Exchange.

Things I don't know:

In a population being ravaged by epidemics, would you would expect the infection rate to remain lower than that of a (more) immune population, or would you expect the infection rates to equalize? Would you expect to see spikes in one population and a more consistent line in the other, or some other indicator of differential impact? I suppose you'd just need comparative evidence, presumably from the Americas.

As lifestyles equalized (until you're comparing an 80% IE and a 40% IE guy who live in adjacent villages in Italy 500 BC), why would the IE effect persist? Wouldn't you expect the correlation to fall over time?

Do pastoralists we can directly observe have higher rates of zoonotic disease than animal-having agriculturalists or animal-eating hunter-gatherers? That seems to have pretty direct bearing on their lifestyle hypothesis.

Is there a similar effect in other places where IEs migrated during the Bronze Age (say, India or Iran), or other places within Eurasia where agriculturalists came into contact with Steppe peoples? They have a couple of data points in Iran and Anatolia and a bunch in SE Asia (for some reason), but everything else is in Europe and central Asia/Siberia.

There's also an odd effect where the two major genetic contributors to the IE population have different effects, Caucasus hunter-gatherer descent being associated with all the zoonotic diseases and Eastern HG being associated mostly with black plague, which is sort of odd, if these are one population with similarly disease-fostering lifestyles.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

With the ‘discovery’ of America, the idea took root that colonization was also a climatic normalization, a way of improving the continent’s climate by clearing and cultivating land. It was a promise to the colonists and a discourse of domination: a way of saying that native peoples had never really owned the New World. In the eighteenth century, acting on the climate served to rank societies and their historical trajectories hierarchically: Amerindian peoples still in the infancy of a savage climate; European peoples creating the mild climate of their continent; Oriental peoples destroying theirs. The Maghreb, India and, later, Black Africa: in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the French and British empires were built on accusing Blacks and Arabs, Islam, nomadism, and the ‘primitive’ mentality, of wrecking the climate. Colonization was conceived and presented as an attempt to restore Nature. The white man must mend the rains, make the seasons milder, push back the desert – and to that end command the natives.

— Jean-Baptiste Fressoz & Fabien Locher (translated by Gregory Elliott), Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotten History of Climate Change.

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#Jean-Baptiste Fressoz#Fabien Locher#Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotten History of Climate Change#Climate Change#book quotes#global warming#extinction rebellion#Colonization#environmentalism#activism#activist#human rights#imperialism#quote#quotes#academia#studyblr#gradblr#chaotic academia#philosophy#philosophy quotes#colonialism#America#Latin America#ecology#solarpunk#ecopunk#1492#Christopher Columbus#Indigenous Peoples

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Listen up, pal, the moon is way up in the sky. Aren’t you scared? The helplessness that comes from nature. That moonlight, think about it, that moonlight paler than a corpse’s face, so silent and far away, that moonlight witnessed the cries of the first monsters to walk the earth, surveyed the peaceful waters after the deluges and the floods, illuminated centuries of nights and went out at dawns throughout centuries…Think about it, my friend, that moonlight will be the same tranquil ghost when the last traces of your great-grandsons’ grandsons no longer exist. Prostrate yourself before it. You’ve shown up for an instant and it is forever. Don’t you suffer, pal? I…I myself can’t stand it. It hits me right here, in the center of my heart, having to die one day and, thousands of centuries later, undistinguished in the humus, eyeless for all eternity. I, I!, for all eternity… and the indifferent, triumphant moon, its pale hands outstretched over new men, new things, different beings. And I Dead!“–I took a deep breath. 'Think about it, my friend. it’s shining over the cemetery right now. The cemetery, where all lie sleeping who once were and never more shall be. There, where the slightest whisper makes the living shudder in terror and where the tranquility of the stars muffles our cries and brings terror to our eyes. There, where there are neither tears nor thoughts to express the profound misery of coming to an end.’

— Clarice Lispector, “Another Couple of Drunks” (”Mais dois bêbedos”) from the Complete Stories

There’s almost a full moon now, shining faintly behind the clouds. I read the other day that we go back two hundred thousand generations. The moon has shone for them all. A short time ago I looked up a tit from where I was standing in the yard, and paused at the thought that Dante had stared at the same moon. Cave dwellers and peoples of the savannah, hunters and gatherers, farmers and forest people. The Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Amerindians. My forebears. Myself, through all my life, three, nine, eighteen, thirty-seven years old. Every night, the moon has been there. But what the thought conjured wouldn’t come. I felt no sense of history’s depths, no sense of being surrounded by our colossal past. If the moon is an eye, it is the eye of the dead. What it says to us is you are alone, you too. You can believe one thing, or you can believe another. It makes no difference, my children. Fight the fight, live life, die death.

— Karl Ove Knausgaard, “At the Bottom of the Universe” from In the Land of the Cyclops: Essays

#clarice lispector#lispector#karl ove knausgaard#knausgaard#literature#moon#nature#quote#death#life#history

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

This one requires a lot of explanation but bear with me. There is a decent amount of evidence that suggest that Polynesian peoples made contact with Native South Americans before Columbus (and by a decent amount I mean like actual genetics stuff I don’t understand).

So, conlang idea: make a concreole for an alternate history scenario where the Polynesians established permanent settlements in South America.

#32

A constructed creole lang (concreolang, if you will) combining Polynesian language with that of Amerindians/other natives of South America.

Also sorry for the slow answers, for some reason the askbox notifications don't show for this sideblog.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research seminar: Postmemory and the archaeology of the ghost.

My subject: The Witness Blanket (2019) by Carey Newman

(English translation from French)

Carey Newman, The Witness Blanket, 2019, wood sculpture with inlay of various objects, Human Rights Museum, Winnipeg, Canada, 3.23 m x 11.96 m.

During the research seminar on postmemory and the archaeology of the ghost, I chose to work on Carey Newman's The Witness Blanket (2019). Newman's father is indigenous to the Hayalthkin'geme community. His father was separated from his family and sent to one of the rehabilitation residential schools that were located across Canada. He never told his children much about what happened to him or the violence he suffered.

I will present a short history of the residential schools, an analysis of part of Newman's work, and a conclusion. I will use testimonies from the artist's book, testimonies from other survivors, and articles about the children's living conditions.

To begin with, I need to outline the origins of schools for Aboriginal children. In 1876, Canada introduced the Indian Act. This law made it possible to control and discriminate against indigenous peoples. As Jacinthe Dion, Jennifer Hains, Amélie Ross, and Delphine Collin-Vézina explain, the Act was made up of several points: "measures linked to the colonization of Aboriginal peoples led to various traumas such as the loss of territory, confinement to reserves, drastic changes in lifestyles, the loss of traditional healing ceremonies and rituals, and the advent of residential schools to educate young people". The authors recount the period of operation of: "These institutions were set up by the Canadian government with the collaboration of religious institutions around 1880 and operated until the last school closed in 1996. According to Marie-Pierre Bousquet, Canada had: "Officially, there were one hundred and thirty-nine residential schools in Canada, at least recognized by the federal government for the purpose of paying compensation to former students […] In 1920, a new section of the Indian Act made schooling compulsory for Amerindian children aged 7 to 15". These boarding schools were camps set up to educate (according to the white colonizers) the indigenous people, or rather to destroy their identities and cultures.

The children separated from their families had to live in very harsh conditions in these institutions, leaving the after-effects described by Jean-François Roussel: "cultural and linguistic uprooting, serious damage to family ties, psychological, physical, sexual and spiritual violence". Many children died in these schools. There is no exact number, but Raymond Frogner and Dominique Fooisy-Geoffroy have drawn up a list of the victims:

"Around 150,000 children attended residential schools;

More than 4,000 confirmed deaths;

400 unmarked burial sites;

32% of deaths where names were not recorded;

23% of deaths where sex was not recorded;

49% of deaths where the cause of death was not recorded;

And, finally, several abandoned cemeteries".

All this data was used by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2008 - 2015), to ensure that the government apologised to the victims of the residential schools (the survivors and the dead), to their families and communities, and also to compensate the victims. This act was recognised as cultural genocide, defined as "the destruction of structures and practices that enable groups to live together as groups".

Carey Newman, The Witness Blanket, 2019, wood sculpture with inlay of various objects, Human Rights Museum, Winnipeg, Canada, 3.23 m x 11.96 m.

It is in this context of recognition of the crime committed by the Canadian government and the church, but also of reconciliation, that the artist Carey Newman has worked on his work: The Witness Blanket (2019) in partnership with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. The work is a sculpture. It is made from objects such as bricks, pieces of wood, and a door. They are salvaged from the rubble of residential schools, but also from donations by survivors of these schools, such as photos, letters, and personal objects from that era. All these elements are mounted and organized like a patchwork quilt on eight wooden panels. The motifs can be found in the culture of certain indigenous peoples. In the center of the room is a wooden door, also from a boarding school. Above the door is a copy of the Indian Act. To create the motif, the artist placed the objects in the same way. I decided to concentrate on three objects.

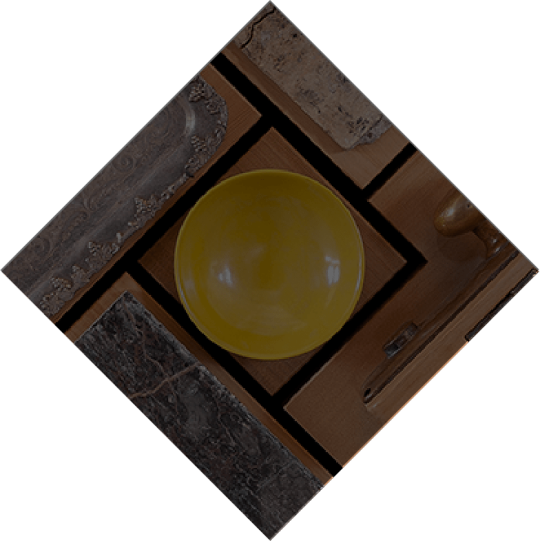

Carey Newman, The Witness Blanket, 2019, wood sculpture with inlay of various objects, Human Rights Museum, Winnipeg, Canada, 3.23 m x 11.96 m, close-up of the bowl.

In the sculpture is a yellow bowl representing the eating disorders of the father passed on to his children. This transmission is defined as post-memory, a term explained by literature professor Maria Hirsch: "The non-verbal, non-cognitive acts of memory transfer that occur within families in terms of symptoms. The painful psychosocial conditions experienced by parents in the past […] that children hear, see and feel in the present. Memory is tangible. It is embodied". With Newman's father, it was the fear of going hungry: Even today, my father's experience of eating at boarding school affects me and my family. For example, because I was taught not to waste food, it's still difficult for me not to eat everything I'm served […] When I had my own child, I realized that I was instilling in him the same harmful eating habits". The reason for this trauma of going hungry is the conditions in which these children lived. In Newman's book, there are testimonies from survivors. One of them explains what the victims ate: "the pupils were given moldy bread and cold, watered-down soup". There is also the punishment suffered by the father, which was passed on: "In boarding schools, pupils were often forced to finish everything on their plates. That's also what happened in my house when I was a child. I was told that if I didn't eat my dinner, I'd be served the same thing for breakfast". This simple story about food is passed down from generation to generation. If the generation that is the victim of this violence cannot close this chapter in its history (close, not forget), it runs the risk of passing on the same violence to the next generation. This bowl represents a trauma bequeathed to the next generation.

Carey Newman, The Witness Blanket, 2019, wood sculpture with inlay of various objects, Human Rights Museum, Winnipeg, Canada, 3.23 m x 11.96 m, close-up of the hairs.

In The Witness Blanket (2019), hair has been hung on one of the panels. This hair belongs to the artist's sisters. The reason for the presence of the girls' hair is to pay homage to their cultures. In indigenous culture, hair is very important. According to Newman, hair "represents strength and is only cut in times of mourning". Hair is an important element in indigenous culture. That's why, when children were sent to boarding schools, the heads of these institutions (priests and nuns) cut their hair with great violence. As writer and survivor, Bev Sellars explains: "Our hair was cut and we were 'deloused' with the pesticide DDT […] Although we held a towel over our face, some of the DDT fell out after we removed the towel, stinging our eyes and giving us a horrible taste". The aim was to humanize the children and create a racist stereotype of the dirty native.

Carey Newman, The Witness Blanket, 2019, wood sculpture with inlay of various objects, Human Rights Museum, Winnipeg, Canada, 3.23 m x 11.96 m, close-up of the door.

The door at the centre of the sculpture is part of the rubble of an infirmary at St. Michael's boarding school. Carey Newman chose it first and foremost for its sombre history: "because of the abuses committed in the boys' infirmary at St. Michael's […]". Although the artist does not go into detail about what might have happened in the infirmary, we can quickly imagine what might have taken place. In 2018, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation conducted a survey: "One in two Canadians is unaware of the existence of residential schools". The door in Newman's work is not closed, to represent a past that must not be forgotten. There are two handprints on the door: they are the handprints of the artist's daughter.

It's a way of including several generations in the same project, and it's also a way for these families to share their common histories. As Sarah Henzi, a professor of indigenous literature, describes it: "The legacy of the historical burden of different systems of assimilation reminds us that anger, pain, shame and racism are passed on from one generation to the next". Newman's sculpture helps to shed light on a forgotten part of history, while at the same time addressing the psychological plight of the victims and their families.

Bibliography

Books:

NEWMAN C. & HUDSON K., The Witness Blanket: Truth, Art and Reconciliation, Victoria, Orca Book Publisher, 2022.

SELLARS B., They Called Me Number One: Secrets and Survival at an Indian Residential School, Vancouver, Talonbooks, 2013.

Journals articles:

BOUSQUET M-P., « La constitution de la mémoire des pensionnats indiens au Québec », Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, N°46, 2016, p. 165-176.

DION J., HAINS J., ROSS A. & COLLIN-VÉZINA, « Pensionnats autochtones : impact intergénérationnel », Enfance et famille autochtones, N°25, 2016, p. 1-25.

HENZI S., « La grande blessure. Legs du système des pensionnats dans l’écriture et le film autochtones au Québec », Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, N°46, 2016, p. 199-211.

NICOLAOU A., « Postmemory at work in Maria Anastssiou’s Notes: Remembered and Found », Einkofi, 2023, p. 1-6.

ROGNER R. & FOISY-GEOFFROY D., « Qui sont ces enfants perdus ? Origine et conception du registre des noms des enfants autochtones décédés dans le système des pensionnats du Canada, selon le Centre national pour la vérité et conciliation », Archives, N°48, 2019, p. 149-159.

ROUSSEL J-F., « La Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada sur les pensionnats autochtones », Théologiques, N°23, 2015, p.31-58.

Podcast:

FONTAINE F., 21 décembre 2018, La reconnaissance du génocide culturel au Canada, [ émission de radio ], radiofrance, consulté le 04 avril 2023 à l’adresse suivante : https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/la-reconnaissance-du-genocide-culturel-au-canada-8280696

#artwork#literature#indigenous#indigineous people#art critique#college#art university#dissertation#french

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Almost all these [Amerindian] societies took pride in their ability to adopt children or captives – even from among those whom they considered the most benighted of their neighbours – and, through care and education, turn them into what they considered to be proper human beings. Slaves, it follows, were an anomaly: people who were neither killed nor adopted, but who hovered somewhere in between; abruptly and violently suspended in the midpoint of a process that should normally lead from prey to pet to family. As such, the captive as slave becomes trapped in the role of ‘caring for others’, a non-person whose work is largely directed towards enabling those others to become persons, warriors, princesses, ‘human beings’ of a particularly valued and special kind.

As these examples show, if we want to understand the origins of violent domination in human societies, this is precisely where we need to look. Mere acts of violence are passing; acts of violence transformed into caring relations have a tendency to endure.”

― David Graeber, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Separatist and irredentist movements in the world

French Guiana

Proposed state: French Guiana

Region: French Guiana, France

Ethnic group: French Guianese

Goal: independence/more autonomy

Date: 1991

Political parties: Decolonization and Social Emancipation Movement

Militant organizations/advocacy groups: -

Current status: active

History

16th century - first French colony

1809-1814 - Portuguese rule

1946 - French Guiana becomes an overseas department

1991 - creation of the Decolonization and Social Emancipation Movement

2010 - status referendum

The first French presence dates to the 16th century, when French Guiana was inhabited by the Arawak, Carib, Palikur, Teko, and Wayampi peoples. It was not a permanent presence until 1643, at which point the territory was developed as a slave society.

Between 1852 and 1953 it became a penal colony, where prisoners had to do forced labor. A Portuguese-British force took French Guiana in 1809 and returned it in 1814.

In 1964, a space-travel base was established, which is now part of the European space industry. The 2010 status referendum rejected the proposed increase of autonomy in favor of full integration into France.

French Guianese

About 65% of the population is of African descent, 14% is of European ancestry, 5% is of Asian descent, and 4% is Amerindian.

The official language is French, but French Guianese Creole, other creoles, and six Amerindian languages are also spoken. Christianity is practiced by 84.2% of French Guianese, of which 74.3% are Roman Catholic.

Vocabulary

autonomie - autonomy

Guyane - French Guiana

indépendance - independence

intégration - integration

Mouvement de décolonisation et d’émancipation sociale - Decolonization and Social Emancipation Movement

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've heard stuff like this before, that Hispanic is a nonsense category. But I actually think it makes sense, at least as far as anything makes sense in the US legal/cultural system of race.

First, just to state the obvious: this wasn't ever intended to be a rigorous, comprehensive, scientific system. It's just a quick and dirty way to classify people, in a way that any average person on the street can see and more-or-less agree on. You don't want to make up dozens of separate specific categories because that quickly spirals into confusion.

…

This quickly led to a situation where Latin America was a mix of white conquistadors, indigenous slaves, black slaves imported from Africa, and mixed-race offspring who had grown up there. Pretty soon the Spanish realized they needed some sort of classification system for who was going to be a slave, who was trustworthy enough to rule, and who was somewhere in-between. Eventually they came up with a rather byzantine system: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mestizo#Mestizo_as_a_colonial-era_category

• Español (fem. española), i.e. Spaniard – person of Spanish ancestry; a blanket term, subdivided into Peninsulares and Criollos

• Peninsular – a person of Spanish descent born in Spain who later settled in the Americas;

• Criollo (fem. criolla) – a person of Spanish descent born in the Americas;

• Castizo (fem. castiza) – a person with primarily Spanish and some American Indian ancestry born into a mixed family.

• Mestizo (fem. mestiza) – a person of extended mixed Spanish and American Indian ancestry;

• Indio (fem. india) – a person of pure American Indian ancestry;

• Pardo (fem. parda) – a person of mixed Spanish, Amerindian and African ancestry; sometimes a polite term for a black person;

• Mulato (fem. mulata) – a person of mixed Spanish and African ancestry;

• Zambo – a person of mixed African and American Indian ancestry;

• Negro (fem. negra) – a person of African descent, primarily former enslaved Africans and their descendants.

Which made sense for their situation, but stops making sense once you abolish slavery and royal titles and all these people start to intermix with each other. So after a few hundred years of that, you end up with modern day Hispanic people. Some are mostly white, some are mostly black, some are mostly indigenous, but a lot of them are a roughly even mix of all three, to the point where it's an obvious group of its own. You still can't exactly call it a race- it's a mix of other races, and it's hard to tell where exactly is the border between Hispanics and one of the other races. But you can't just say "mixed-race" either, for something that's been so thoroughly mixed for hundreds of years. So they made up a new word, "ethnicity", and called it a day.

Of course all this is awkward to talk about in polite society, and most Americans don't really know the history of Latin America. In Mexico they call it La Raza which makes a lot more sense, but that sounds bad in English and the term hasn't made it here yet. So they decided to classify it on language, "are you from a Spanish-speaking area?" That's... weird, since it includes white people from Spain and excludes people from Brazil or Belize. But it works well enough for the US, where most Latin-American immigrants are from Spanish-speaking areas.

It's certainly not a perfect term, and I think we're moving towards changing it with weird postmodern terms like LatinX or Chicano, but it's good enough for 99% of situations to get the idea across. It's actually a lot less confusing than African (eliding the difference between North, West-sub-Saharan, and East-Sub-Saharan African) or Asian (it's a big continent lol) or white (are Arabs white?). It's also (like all racial data in the US) mostly self-reported. But I challenge you- find a person who self reports as "Hispanic," ask the average person to draw a sketch or select a picture, and see how well it matches. Most of the time, it's pretty close.

1 note

·

View note

Text

BRAZIL - Diasporas and forced migration

The “Caixa do Divino” is the only exclusively womxn drumming and singing tradition in Brazil and exists in the context of Candomblé Houses (afro-indigenous diasporic semi-autonomous land) and Maroon Communities as part of the celebrations of Oxalá, an ancient force of nature that praise for the prophecy of The Earth having hundred years of peace through the ruling of children.

Brazil is the country that had historically the largest forced migration population from the African continent in the world during more than 400 years of enslavement operated by the Portuguese Empire and financed by colonial enterprises based in France, Spain and The Netherlands. There would be a lot to be said about the global implications of this nefarious economic strategy and the immense welfare that was taken and stolen from the colonised country. Activities such as gold and silver mining, sugar cane, cotton and coffee plantations, and animal breeding are among the activities that support this economic strategy, enforcing an intense exploiting project for the benefit of Eurocentric economies. This economic strategy is still in place in the current globalized economic context, and it had and has immense implications for the livelihood of millions of people and the environment, including the destruction of the Amazon and other forest biomes, contributing to the current alarming climate change crisis affecting the whole planet.

During the implementation of this economic strategy based on the slavering labour model, the whole of the Americas suffered the biggest known genocide in history; in 100 years of colonisation, 97% of the native population was brutally killed. In this regard, besides not being the focus of this project, we believe that it is important to highlight that the Eurocentric perspective tries to re-tell colonisation stories, removing or hiding the horrors done to the original populations in the Americas, to their territories and the global consequences it has until nowadays.

In this context, this project aims to acknowledge the complex diasporic ethnic culture or resistance and the permanence and continuity of people (s) and lands throughout this violent process, despite and beyond all the difficulties. This resistance process made Brazil one of the most prominent and welcoming places for immigrant populations. Brazil has the largest remaining indigenous protected territories in the world, the largest African-descendent population outside the African continent, the largest Japanese community outside Japan, the largest Lebanese community outside Lebanon, and huge communities of Italian, Spanish, German, Chinese, Romani and Jewish people, among many others. Nowadays, despite the process of forcing their mixing, this diversity of populations living in Brazil holds a place where anyone can become and name themselves, for the good and the bad, as Brazilian. One of these mixing strategies, not from the perspective of oppression but from the standpoint of resistance, resulted in the interchange of two main traditional structures: the Amerindian cosmology and the African diaspora.

0 notes

Text

History of the idea of race

The term "race" was first employed in the English language to categorise human beings in the late 16th century. Until the 18th century, it had a broad connotation, comparable to other classification names like type, sort, or kind. Shakespeare's period occasionally alluded to a "race of saints" or "a race of bishops." By the 18th century, race was widely utilised for categorising and ranking the peoples in the English colonies—Europeans who viewed themselves as free, conquered Amerindians, and Africans brought in as slave labor—and this usage continues to this day.

youtube

The conquered and enslaved peoples were physically distinct from western and northern Europeans, but physical differences were not the only reason for the establishment of racial classifications. The English have a long history of isolating themselves from others and regarding immigrants as strange "others." By the 17th century, their policies and practises in Ireland had created a stereotype of the Irish as "savages" incapable of being civilised. Proposals to conquer the Irish, seize their lands, and utilise them as forced labourers were mainly unsuccessful due to Irish opposition. Many Englishmen were drawn to the concept of colonising the New World at this time. Slavery has existed for ages as a notion. People who were enslaved, or "slaves," were forced to work for another. We may see the term slave used throughout the Hebrew Bible, ancient cultures such as Greece, Rome, and Egypt, and throughout history. Before the 16th century, enslavement was permitted throughout the Mediterranean and European regions for anyone deemed heathens or outside of Christian-based faiths. Being a slave in this planet was not for life or hereditary, which meant that the position of a slave did not immediately shift from parent to kid. Slaves may still earn minor earnings, congregate with others, marry, and even buy their freedom in many societies.

Peter Wade. (2023). Race. [Online]. Britannica. Last Updated: 1 September 2023. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/race-human/Race-as-a-mechanism-of-social-division [Accessed 3 September 2023].

0 notes

Text

Guyana

Guyana is a South American country located on the northeastern coast of the continent. It is the only country in South America where English is the official language, making it a unique destination for travelers. The country is bordered by Venezuela to the west, Brazil to the south, Suriname to the east, and the Atlantic Ocean to the north.

With a land area of approximately 215,000 square kilometers and a population of just over 780,000, Guyana is known for its wide range of biodiversity, natural resources, and rich cultural heritage.

Visitors to Guyana can explore its diverse landscape, including its lush rainforests, towering mountains, and winding rivers. The country is home to a number of national parks and nature reserves, offering opportunities for wildlife viewing, birdwatching, and hiking.

Beyond its natural attractions, Guyana also has a rich history and cultural heritage. From its indigenous peoples to its colonial roots, the country has a fascinating past that is well worth exploring. The capital city, Georgetown, is a hub of activity and offers visitors a glimpse into the country's vibrant culture.

Whether you are interested in exploring the great outdoors, learning about Guyana's history and culture, or simply relaxing on a tropical beach, this South American country has something to offer everyone.

Etymology

The name Guyana is believed to have originated from the indigenous Amerindian language, specifically the Arawak tribes who inhabited the region before the arrival of European settlers. The term "Guiana" referred to "land of water" or "water's edge" in Arawak, describing the plentiful rivers and lush rainforests that characterize the region.

During the 16th century, Spanish explorers referred to the area as "Guayana," a variation of the Arawak term. The Dutch later colonized the region, naming it "Nieuw Guyana" or "New Guiana." In 1831, the British seized control of the region and consolidated it with their other South American territories to form British Guiana.

After gaining independence from Britain in 1966, the country was officially named the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, reflecting its diverse population and commitment to unity. Today, the country remains a melting pot of indigenous, African, Indian, Chinese, and European influences, with a rich history and culture that reflects its unique heritage and heritage.

History

Located on the northern coast of South America, Guyana has a rich and diverse history dating back thousands of years. The first inhabitants of the region were indigenous tribes, including the Arawaks and Caribs.

During the 16th century, the Spanish were the first Europeans to explore the region that is now Guyana, but they did not attempt to settle the area. It was not until the Dutch arrived in the early 17th century that European colonization began in earnest. The Dutch established a series of trading posts along the coast and brought in slaves from Africa to work on plantations.

In the late 18th century, Britain gained control of the region from the Dutch, and in 1814, the colony of British Guiana was officially established. The British continued to use enslaved labor until its abolition in 1838. Guyana remained a British colony until 1966 when it gained independence.

Throughout its history, Guyana has been shaped by the interplay of various cultures, including Indigenous, African, Indian, Chinese and European cultures. Today, the country remains ethnically diverse, with a rich cultural heritage that is celebrated through its music, dance, festivals, and food.

Major Events in Guyana's History

Year

Event

1498

Christopher Columbus visits the region

1616

The Dutch found the colony of Essequibo

1762

The British capture the Dutch colonies of Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice

1834

Slavery is abolished in British Guiana

1928

The British Guiana Labour Party (BGLP) is founded

1966

Guyana gains independence from Britain

1980

Guyana becomes a republic

Despite its small size, Guyana has played a significant role in regional and global politics. It has been a member of the United Nations since 1966 and has also been a member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) since its establishment in 1973. Today, Guyana is known for its efforts to protect its unique ecosystems and cultural heritage, as well as for its vast reserves of natural resources such as gold, diamonds, and timber.

Guyana's history is both a fascinating and complex tapestry of different cultures, traditions, and influences that has shaped the country into what it is today.

Geology

Guyana is a country with a rich and unique geological history. One of its most prominent features is the Guiana Shield, which is a vast area of ancient rock formations that extends throughout much of South America. In Guyana, the Shield covers nearly 75% of the country's land area and provides a foundation for a diverse range of ecosystems and wildlife.

Another notable geological feature of Guyana is the Kaieteur Falls, which is one of the most powerful waterfalls in the world. The waterfall is located in the heart of Guyana's rainforest, and it drops a staggering 741 feet into a gorge below. The Kaieteur Falls is not only a breathtaking natural wonder but also an important source of hydroelectric power for the country.

Guyana also has a variety of other waterfalls, including the Orinduik Falls and the King George VI Falls. the country is home to numerous rivers, such as the Demerara River, which is the longest river in Guyana and a major transportation route for goods and people.

Mountains are another important part of Guyana's landscape. The Kanuku Mountains, for example, rise up from the forested plains in the south-central region of the country. These mountains are home to a variety of endangered species, including the giant otter, harpy eagle, and jaguar.

The Pakaraima Mountains, located in the western part of Guyana, are another important geological feature in the country. They are home to the country's highest peak, Mount Roraima, which straddles the borders of Guyana, Venezuela, and Brazil. This mountain range also contains numerous rivers and waterfalls and is an important part of the country's ecotourism industry.

In addition to its mountains and waterfalls, Guyana is also home to a variety of unique rock formations, including giant boulders that are scattered throughout the savannas of the Rupununi region. These rock formations are believed to be over two billion years old and are an important part of Guyana's geological heritage.

Guyana's unique geological features make it a fascinating destination for geologists, nature lovers, and adventure seekers. From its towering waterfalls to its ancient rock formations, this South American country is a treasure trove of natural wonders waiting to be explored.

Geography

Guyana, located on the northern coast of South America, boasts an incredibly diverse landscape. With dense rainforests, expansive savannas, and towering mountains, the country has something to offer every type of adventurer.

Starting with its rivers, Guyana is home to some of the largest and most powerful in the world. The Essequibo River, the third longest in South America, runs through the heart of the country and features incredible wildlife such as river otters and giant river turtles. the Demerara, Berbice, and Corentyne Rivers are important for transportation and fishing industries.

In terms of mountains, the Pakaraima Mountains provide a stunning backdrop for Guyana's landscape. The highest peak in the country is Mount Roraima, which stands at 9,219 feet and is part of the Triple Border, where Guyana, Venezuela, and Brazil meet. A trek up the mountain provides breathtaking views and is a popular destination for hikers.

Guyana's rainforests are a sight to behold. The country's tropical climate allows for lush vegetation to thrive, with over 80% of the country being covered in forests. The Amazon rainforest stretches into Guyana's southern regions, providing a haven for exotic wildlife such as jaguars and giant anteaters.

Guyana's geography is one of its greatest attractions. Whether you're looking for adventure in the mountains or relaxation on a peaceful river, this South American country has it all.

Ecology

Guyana's ecosystem is incredibly important, as it serves as a home to a wide range of species, some of which can only be found in this unique South American country. The country's many rivers and dense rainforests provide habitats for a diverse range of animals, from jaguars and giant otters to monkeys and spiders.

One of the most interesting species found in Guyana is the giant anteater. This impressive animal can be found in the country's savannahs, where it uses its long, sticky tongue to eat up to 30,000 ants and termites per day. The jaguar is another iconic resident of the Guyanese forests. These large cats are incredibly fast and can easily climb trees, making them an apex predator in the region.

However, Guyana is not just home to larger animals - the country is also home to an incredible array of birds, reptiles, and insects. Guyana is famous for the giant otter, which can be seen playing and swimming in the country's rivers and streams. This species is incredibly intelligent and social, living in groups of up to 20 individuals.

In addition to these larger, more charismatic species, Guyana is also home to some of the world's most important plant and insect life. The country's dense rainforests are home to a huge variety of trees, many of which are used for medicinal purposes. The Amazon Rainforest, which takes up a large portion of Guyana's landmass, is known for its incredible biodiversity, with scientists estimating that there may be up to 16,000 different tree species in the region.

Unfortunately, Guyana's ecosystem is under threat due to deforestation and climate change. Trees are being cut down at an alarming rate, which in turn is harming the many species that call Guyana home. The loss of habitat is especially concerning for endangered species such as the giant river otter and the harpy eagle.

Despite these challenges, there is hope for Guyana's ecosystem. The country has taken a leading role in the battle against climate change, with its government committing to preserving forest land and working with international organizations to support sustainable development. This includes programs to encourage ecotourism, which in turn can help support local communities and provide an economic incentive to protect Guyana's stunning natural environment.

Guyana's ecosystem is of immense value and importance, both to the country itself and to the wider world. Preserving this unique environment is vital for the species that call it home, and for the many benefits it provides to humans as well.

Biodiversity

Guyana is home to a vast array of flora and fauna, making it one of the most diverse ecosystems in the world. With dense rainforests, savannahs, wetlands, and coastal regions, Guyana is a haven for biodiversity.

It is estimated that Guyana has over 7,000 species of plants, many of which are used for medicinal purposes. The country's rainforests provide a habitat for over 800 species of birds, including the national bird, the hoatzin, and the harpy eagle. Amongst the most unique species found in the rainforests are the giant otter and the giant anteater.

Guyana is also home to a variety of primates, including the howler monkey, spider monkey, and capuchin monkey, as well as other mammals such as the jaguar, puma, and tapir. The country's waters are equally rich, with over 400 species of fish and several species of marine mammals, including manatees and dolphins.

Despite its rich biodiversity, Guyana faces several threats to its ecosystem, including deforestation, mining, and climate change. Many of the country's species are endangered, including the giant otter, the harpy eagle, and the jaguar. However, measures such as protected areas, conservation efforts, and ecotourism have been implemented to help preserve the country's biodiversity.

In recent years, Guyana has made significant strides in preserving its natural resources. The country has established several protected areas, including the Kaieteur National Park and the Kanuku Mountains Protected Area, to preserve its unique flora and fauna. ecotourism has become a major industry, providing an economic incentive for preserving the country's biodiversity.

There is no doubt that Guyana's rich biodiversity holds immense value, not just for the country but for the world as a whole. With continued conservation and preservation efforts, Guyana can continue to showcase itself as a leader in eco-tourism and environmental sustainability while maintaining its diverse and unique ecosystem.

spider monkey

Climate

Guyana has a tropical climate, with two distinct seasons: a wet season from May to July and a dry season from August to November. The average temperature in Guyana ranges from 24°C to 32°C. The country's climate has a significant impact on its environment and agriculture.

The wet season in Guyana often results in flooding, which can damage the country's infrastructure and affect agriculture. At the same time, the rainfall also helps to replenish water sources and irrigate crops. The dry season, on the other hand, can lead to droughts that can have devastating effects on agriculture.

Despite the challenges posed by the climate, Guyana has significant potential for agriculture. The country has vast fertile lands that can be used for agriculture, but the lack of proper irrigation systems and infrastructure limits the agricultural production. The government has taken steps to improve agriculture production by investing in infrastructure and promoting sustainable farming practices. Recently, there has been a push for the increase in organic farming in Guyana.

The country's climate has also spurred the development of eco-tourism, with many visitors interested in the unique flora and fauna found in Guyana's rainforests. Guyana has one of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world, and the country is home to many endangered species.

Guyana's tropical climate plays a significant role in the country's environment and agricultural sector, with both positive and negative effects. Proper infrastructure and sustainable farming practices can help to mitigate the negative effects of the climate and unlock the potential of Guyana's rich agricultural resources and diverse ecosystem.

Environmental Issues

Guyana is facing a multitude of environmental challenges that threaten its fragile ecosystem. Among these challenges are deforestation and climate change. Deforestation in Guyana is mainly driven by the mining industry, which clears large areas of forest to extract minerals such as gold and bauxite. In addition, commercial logging and agriculture also contribute to deforestation.

Deforestation has a significant impact on Guyana's environment and biodiversity. The country has one of the largest undisturbed tropical rainforests in the world, which is home to a diverse array of plant and animal species, many of which are endemic. Deforestation not only destroys their habitat but also disrupts the delicate balance of the ecosystem.

The other major environmental issue faced by Guyana is climate change. The country experiences extreme weather events such as flooding and droughts, which are becoming increasingly severe and frequent due to climate change. The agricultural sector, which plays a vital role in Guyana's economy, is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Guyana's government has recognized the importance of addressing these environmental issues and has taken steps to mitigate their impact. In 2009, the country introduced a Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS) aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions caused by deforestation and promoting sustainable development. The LCDS involves creating a mechanism for payments for ecosystem services, which provide economic incentives for forest conservation.

In addition to the LCDS, Guyana is also working to promote sustainable forestry and agricultural practices. The government is introducing measures to reduce the impact of mining on the environment, including setting aside protected areas where mining is not permitted. Guyana has also implemented legislation to regulate logging and promote sustainable forestry practices.

While these initiatives are a step in the right direction, there is a still a long way to go before Guyana's ecosystem can be considered safe. It is important that the government continues to prioritize environmental protection and work towards sustainable development. This will not only benefit the country's unique ecology but also its economy and the well-being of its people.

Politics

Guyana is a country that operates as a presidential representative democratic republic, meaning that the President acts both as the head of state and the head of government. The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term and can only serve a maximum of two terms.The National Assembly, which is made up of 65 members, is the unicameral legislative body in Guyana. Members of the National Assembly are elected by proportional representation, with the country being divided into nine regions, and each region is allocated a number of seats in the National Assembly based on its population.Guyana has been facing political turbulence following the March 2020 elections, which were closely contested between the incumbent and opposition parties. The results were delayed due to allegations of vote fraud and irregularities in the election process. The situation was tense, and violence erupted between rival political factions. However, in August of the same year, the election results were validated by the country's highest court, and Irfaan Ali of the People's Progressive Party was declared the winner and sworn in as the ninth President of Guyana.Apart from the election controversy, Guyana is facing a host of other social and economic issues, including corruption, drug trafficking, poverty, and unemployment. The political landscape is not immune to these challenges. The government has been grappling with allegations of corruption, and there have been calls for greater accountability and transparency in government operations. Furthermore, Guyana is facing environmental issues such as forest destruction and climate change, which will undoubtedly require the government's attention and action.Guyana's foreign policy is anchored on the principles of non-alignment, peaceful coexistence, and respect for international law. The country maintains diplomatic relations with more than 110 countries and is a member of several international organizations such as the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, and the Union of South American Nations.Guyana's political landscape is fraught with challenges, both old and new.

Read the full article

0 notes