#architectural journalism

Photo

An exhibition/pavilion review:

Ringing Hollow: A Review of Black Chapel, the 2022 Serpentine Pavilion

Calvin Po

It’s perhaps an unfortunate coincidence that on my way to this year’s Serpentine Pavilion, Black Chapel, designed by Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates, I had a rather more spiritual experience when I passed by a group of street preachers on the square next to Speaker's Corner. With their Union Jack bunting draped all around their assembly, placards with JESUS IS LORD, large banners of the English flag adorned a patriotic lion and names of the all the London boroughs proudly proclaiming LONDON SHALL BE SAVED. Puncturing through even my atheistic, bemused scepticism, the blaring music and odd bursts of song had a patriotic, messianic energy that was electric. By the time I got to the Chapel I came to see, it had simply been upstaged.

Pavilions have often mattered more for the reason they are built, than the actual functions they house. From completing the composition of a Picturesque landscape, to Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion itself becoming a manifesto, the purpose of pavilions often exists beyond the building itself. In the case of the Serpentine Pavilion, it is more about the annual cycle of patronage by the London cultural elite as they pat the “emerging architect” of the year on the back. So I was intrigued when Gates claimed a loftier, more sacred ambition of creating a ‘Chapel’, a “sanctuary for reflection, refuge and conviviality”, for “contemplation and convening”, on top of the usual purpose as a place to sit and buy an expensive coffee.

The pavilion’s imposing 10.7m high cylindrical form, clad in all-black timber has an immediate presence as I approach. Gates claims the form references inspirations as eclectic as “Musgum mud huts of Cameroon, the Kasubi Tombs of Kampala, Uganda [...] the sacred forms of Hungarian round churches and the ring shouts, voodoo circles and roda de capoeira witnessed in the sacred practices of the African diaspora.” Perhaps the subtlety of these references is lost on me, but the Pavilion mostly evokes an industrial structure, like a water tank or gasometer, especially with its external ridges of timber battens and internal ribs of timber and metal composite trusses. Yet despite the grand gesture of an open oculus in the roof, letting light into the inky, voluminous interior, it fails to move me in that transcendental way that even a modest place of worship can.

Is it perhaps the quality of the execution? Serpentine Pavilions are often put together on hasty timescales, with six months from conception to completion. Little details give this away: boards of the decking and cladding not quite lining up, the black-stained timber a bargain basement imitation of yakisugi (Japanese technique of timber charring). Perhaps this can be forgiven of a non-permanent structure: in a nod to sustainability credentials, this year the designers have taken care to ensure the structure is demountable, down to the reusable, precast concrete foundations. But seeing that the Pavilions are almost always auctioned off to recoup the costs and relocated to the grounds of private collectors and galleries, this seems more a convenient commercial expediency, than an environmental one. Perhaps it is difficult to be spiritually moved by a structure that is sold and delivered like a commodity, with little rootedness in its physical and congregational geographies.

Or could it be the atmosphere, a lack of drama? One of Gate’s flourishes, such as his seven silvery ‘Tar Paintings’ that are suspended in the inside walls of the space like abstract icons, are a nod to his father’s trade as a roofer, and Rothko’s chapel in Houston. Yet these self-referential gestures seem lost on the throngs of sun-seeking Londoners taking brief shelter from the heat and wilted grass, with hardly anyone giving them a second glance. Most seemed more interested in the shade than symbolism. For a project that also emphasises “the sonic and the silent”, the acoustic atmosphere of the space I found wanting, perhaps because of the sound that leaks out of the two full-height openings that puncture straight through the volume: its acoustic experience had neither the reverberant, sanctified silence once expects from a chapel, nor the sonic presence that the street preachers managed to carve out of a busy corner of a London with just their vocal chords. Instead, all I heard was the low chatter of visitors going about their own business. The Pavilion is being programmed with “sonic interventions” (read: music performances), and the jury is out on whether or not the Pavilion can serve as a suitable venue for sounds with a more explicit, ceremonial intentionality.

But perhaps the coup de grâce was the decision to relocate a bell from St Laurence, a now-demolished Catholic Church from Chicago’s South Side. Sited next to the entrance, it is to be “used to call, signal and announce performances and activations at the Pavilion throughout the summer.” Gates explains this decision as a way to highlight the “erasure of spaces of convening and spiritual communion in urban communities.” But now mounted on a minimal, rusty steel frame like an objet d’art, I can’t help but feel a cruel irony that a consecrated object that once used to convene a lost community is now used as a performative affectation for the amusement of London’s arts and cultural gentry. This perhaps exemplifies a deeper ethical issue at the heart of the Pavilion’s concept: narratives of collective worship, cherry-picked from across communities and cultures, are sanitised, secularised and aestheticised in a contemporary art wrapper for the tastes of the largely godless culture crowd. The curator’s spiels of a creating “hallowed chamber”, if anything ring hollow.

As I leave Hyde Park, I pass by again the assembly of street preachers, who have now moved on to delivering a sermon. Gates said of his Pavilion, “it is intended to be humble.” Yet I can’t help but but feel how much more these preachers have achieved, with so much less.

#writing#journalism#architecture#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#exhibition#exhibition review

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

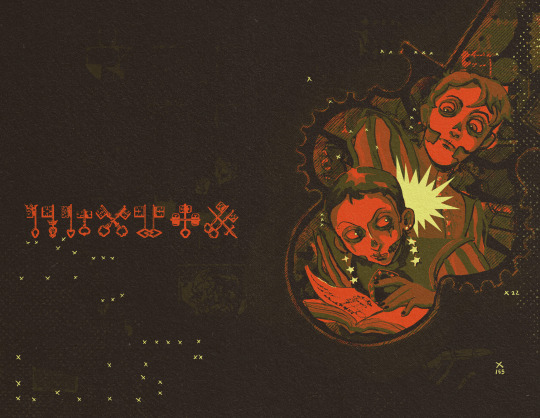

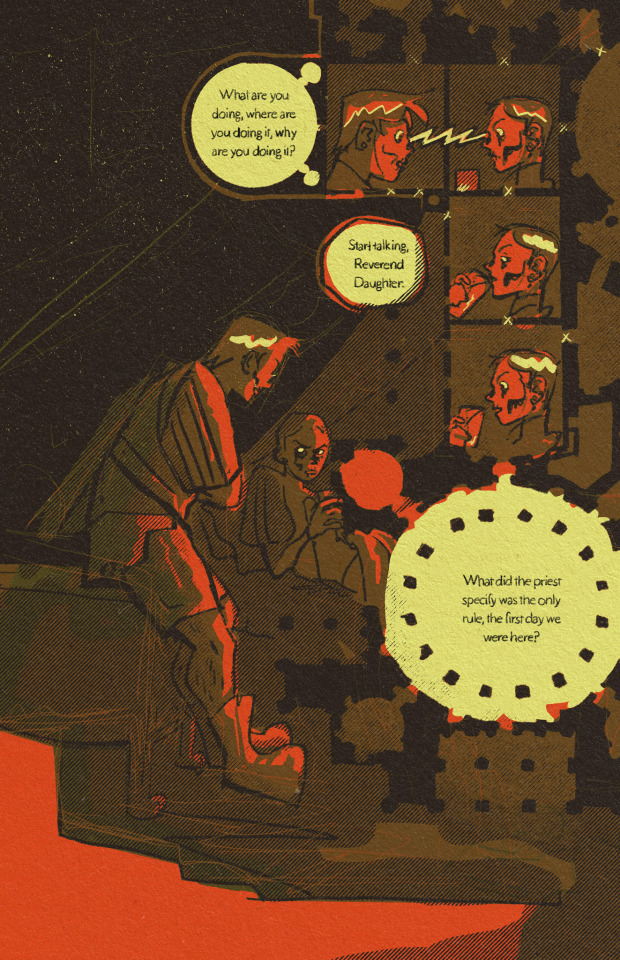

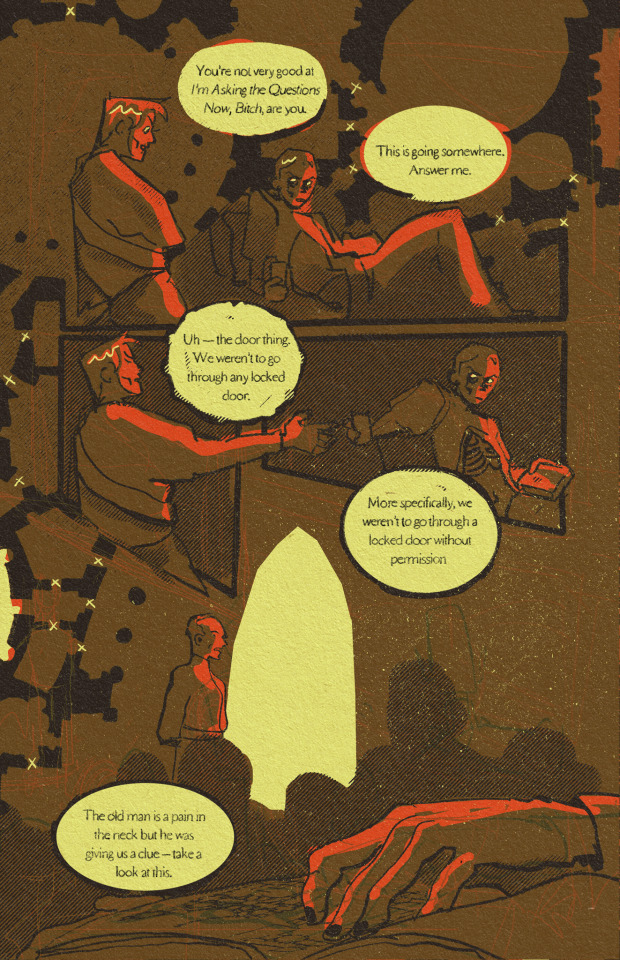

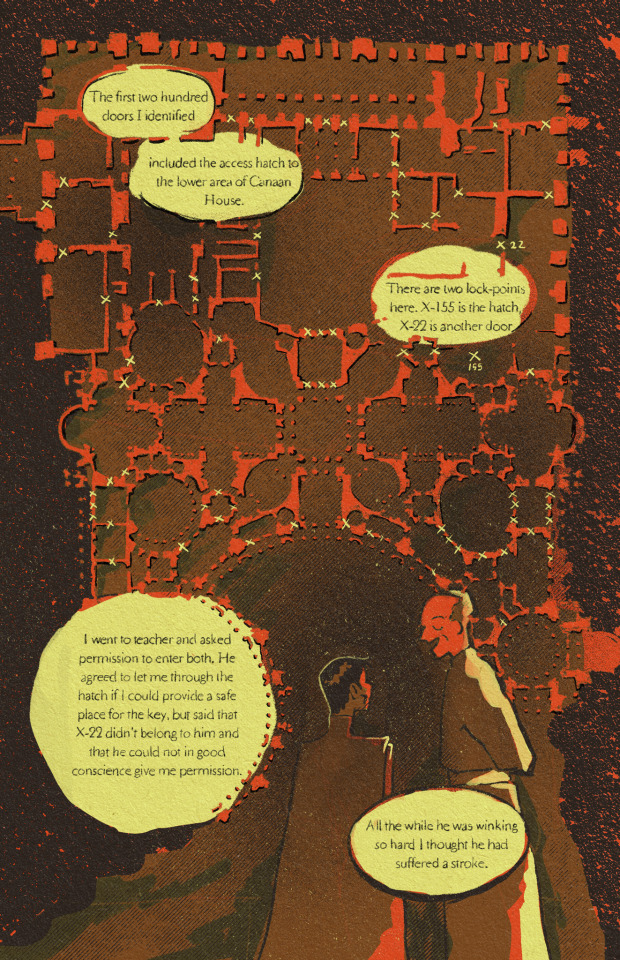

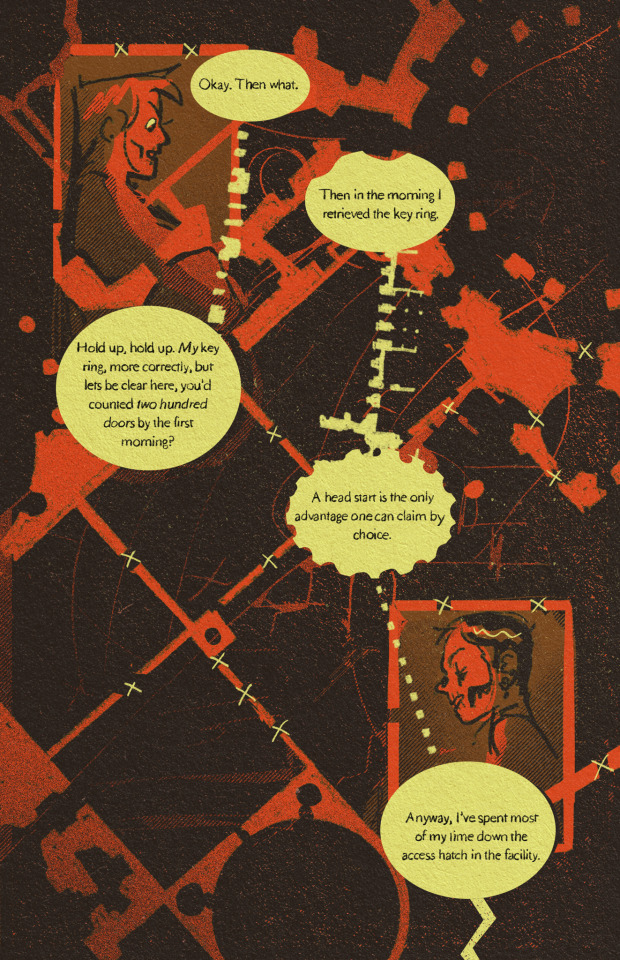

This place is a message... and part of a system of messages... pay attention to it!

#have linked 2 this song before and i will link 2 it again. because HELLO. canaan house thesis statement 2 me.#rlly obsessed w this scene i think i’m just fascinated w the idea of harrows journals…… her drawings of canaan…what else is in there#anyway this was mostly an excuse for me to play around w using architectural drawings as a sort of compositional element/framing device.#did it work? who’s to say. the most important part is that i had fun except. i didn’t even do that.#text is slightly edited for length etc…. + i cut off the scene where i did because well…. makes me insane. lol#don’t pay too much attention 2 the architectural parts they don’t make sense#because i cobbled them together from the plans of like 3 different buildings.#anyway enjoy. or don’t. i’m not ur boss.#the locked tomb#tlt#gideon the ninth#gideon nav#harrowhark nonagesimus#harrow the ninth#okay that’s it

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

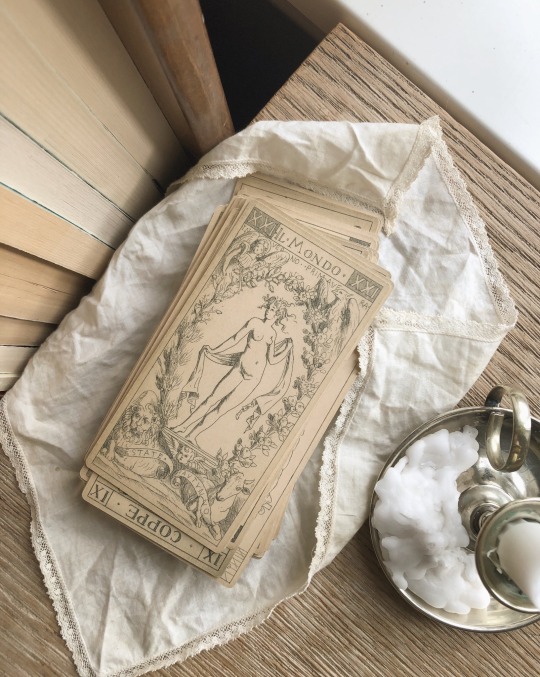

Unveiling the Next Chapter: A Symphony of Contemporary Art and Architecture in New Yonder Journal

765 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Atlantis by Arquitectonica

Miami, Florida; 1979

#70s#design#architecture#Miami#Florida#The Atlantis#Arquitectonica#L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui Journal

385 notes

·

View notes

Text

november mood 🕯️🦢

#journal#mine#light academia#vintage#dark academia#cottagecore#academia#academia aesthetic#vintage aesthetic#antiques#architecture#moodboard#pinterest

887 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe I'm back, maybe not. .-.

#hristinasview#mine#studyblr#aesthetic#bullet journal#architecture#art#home & lifestyle#museums#student#bujo#bujoinspo#studyspo#study motivation#diary#meal#chicken#slavic#aestethic#aesthetics#study snacks#snack#healthy#student life#lifestyle#calligraphy#handwriting#balcani#motivation#study

451 notes

·

View notes

Text

springtime.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

why is this full time gamer a better artist than me, a professional illustrator......

#for real why is he so good at drawing buildings...#buildings r my specialty too#to be fair i do traditional work and i actually specialise in scientific/botanical illustration but.#mumbo jumbo#mumbo#mumbo for mayor#more like mumbo for president#of the hermitcraft architectural drawing society at least#hermitcraft#also bdubs and pearl are incredible illustrators... plus grian does ceramics and joe and cleo's bullet journaling stuff is awesome#why are they all so stupidly talented#hermitcraft 10#exploding them with my mind

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library

Washington, DC

July 30, 2022

#mine#originial photographers#architecture#miesvanderrohe#international style#mlk#martin luther king jr#traveljournal#travelphotography#art#design#journaling#creators on tumblr#culture#books libraries#travel#booklover#library#history#science#coffee#study#work aesthetic#aesthetic

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Nilgiris

#phone photography#nature lovers#lensblr#india#nature#nature photography#beautiful places#aesthetic#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#architecture#house#naturecore#nature blog#natureblr#original photography#my photography#photography blog#photography#nilgiris#mountain life#mountains#mountain landscape#landscape#hills#beautiful#travel journal#travel#explore#tea plantation

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

⚠️ BIVE STIMBOARD

1 2 3 • 4 5 6 • 7 8 9

#aaauuuuu#icon thrown together by me ^x^#mod ouppy#regretevator bive#regretevator#roblox#stim#stimboard#brown stim#black stim#grey stim#gray stim#video game stim#teeth stim#fang stim#detective stim#paper stim#journal stim#stationery stim#elevator stim#architecture stim#abandoned stim#horror stim#paranoia stim#book stim

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

For the Architectural Review

Bass Coast Farmhouse in Victoria, Australia by John Wardle Architects

Calvin Po

For the architectural profession, building on the unceded lands of Indigenous people is a conflicting proposition, yet one that is almost inevitable for architects in Australia. Bass Coast Farmhouse, by John Wardle Architects, is one such project, built on former farmland among coastal heath reserves off the Bass Strait in Victoria. As they do with all their projects, the architects acknowledge the Traditional Owners, in this case the Boonwurrung people of the Kulin Nation.

Between the role of the architect, duty to their client, and wider questions of postcolonial ethics, these tensions permeate the house’s character and its distinctive relationship to the land. The Kulin Nation’s Tanderrum ceremony extends to outsiders a welcome to Country conditional on honouring the land and its intertwined relationships with its people: ‘The land ... is our mother. These cliffs are like our cathedrals, this is our church.’ On this sacral land, the architect’s exploration of ‘the nature of building on terra firma’ is not just an architectural fantasy, but a reflection of this quandary, and rejection of colonial myths of terra nullius – the land is not a blank slate.

From ecological footprint to the architectonics, this sensitivity is omnipresent. The house is entirely off-grid and the construction is largely prefabricated to minimise onsite waste and disturbance. The house sits gingerly on the ridge of a dune, making only the necessary contact with the ground. It is then cantilevered as the dune falls beneath the house. The cantilever, with its barn-like void and its suspended walkway, evokes an archaeological shelter, spanning over and shielding artefacts, and framing them for display. To enter the house, a set of stairs descends from this walkway as if down into geological strata of times past.

As for what is being sheltered – the dune and a scattering of stones – they too become imbued with new significance. After centuries of European colonisation, few traces of Boonwurrung heritage remain. It is the land itself, and the Boonwurrung people’s intergenerational custodianship of it, which is left to be protected. A critical part of the project is repairing parts of the site degraded by modern agricultural extraction, with a specialist advising on a massive replanting project for carefully restoring indigenous grass, shrub, and tree species. In contrast with the landscape, the house’s timber cladding (already silvering in the antipodean sun) and the corrugated galvanised steel roof seem to acknowledge its fleeting presence, relative to the long histories of the Kulin Nation.

The house is the antithesis of being ‘monarch of all [it] surveys’, to quote William Cowper’s poem on Alexander Selkirk, the British castaway in the Pacific. The Anglocentric ideals of Capability Brown’s Picturesque landscapes, where the earth itself is reshaped for the pleasure of the house’s gaze, are rejected. All the outward-facing windows, including the living room’s picture window, can be shuttered at a moment’s notice. For a house surrounded by expanses of nature and the coast, it is surprisingly introspective, with its primary aspect oriented around the central courtyard. The house is also extensive for a single-storey family home, with beds and bunks in polished, timber-panelled rooms, accommodating over a dozen people. But rather than bearing down on the terrain or asserting its panoramic dominion, the house seems to recognise that the views and the land are on loan, not owned.

John Wardle Architects, with its recently inaugurated Reconciliation Action Plan, joins others in Australia in re-evaluating their relationship with First Nations. But in the end, the impact a private house can have on reconciliation is limited. As Carolyn Briggs, a senior Boonwurrung elder, once reflected, ‘I’m always trying to find markers that inform me that we still have a part in this place. ... I think it would be amazing if you can start to read the land and wonder about the history of the people who lived and died before we were here. Hopefully one day you’ll know it. But we can’t see that now in the built environment.’

Link to original article here.

#writing#journalism#architectural writing#architectural criticism#critique#architectural journalism#New Architecture Writers#building#building study#building review#architecture#Architectural Review#John Wardle Architects

1 note

·

View note

Text

jan 13, 2024 — it’s about to get REAL cold, so it’s time to prepare for warm jackets, warm meals, and warm tea. the quarter is picking up so i’ll have to find time to write some essays in between all the snow fun

#college#studyblr#dark academia#university#academia#architecture#books#light academia#photography#photos#study#journal#diary

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

from ‘Lettres de Guerre’ series

max kuiper – 13 nov 2023

#art#photography#collage#war#violence#history#journalism#building#architecture#ruine#woman#women#face#visual art#silkscreen#print#photocopy

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Тёплые лучи мягко ложатся на каменные стены домов, напоминая им и людям вокруг, что счастье это просто. Я учусь видеть красоту в чём-то простом и, казалось бы, заурядном. Ведь искусственно созданная красота, эстетика не позволяют порой пораскинуть мозгами и попытаться найти то, что зацепит взгляд или тронет душу. Обычно дают всё готовенькое. Красивые углы, правильно подобранный цвет. Смотря так на красивый дизайн, эстетично построенное здание с множеством разноцветных стёкол, я начинаю чувствовать себя избалованным ребёнком. Этому ребёнку ничего не нужно, кроме готовенького, прямо указывающее на красоту. Однако точно такая же, а порой и лучше, красота окружает каждого из нас. Кроется она то в листочке, то в ясном небе, а то и в простом солнечном луче, что как дорожка ложится на холодную поверхность, словно освещая путь.

Красота бывает разной. Специально «выструганная» и естественная. Однако цель у красоты одна — дарить наслаждение и радость, в каком-то роде даже удовлетворение. Порой не стоит ходить в специализированные места, чтобы найти красоту. Достаточно просто посмотреть на вещи под другим углом.

#notes#organized#study#photographers on tumblr#painting#photography#study aesthetic#study motivation#canon rebel#landscape#art#artists on tumblr#architecture#beautiful photos#original photographers#photoblog#photographer#оригинальные#русский блог#мой блог#эстетика#aesthetic#закат#здание#дневник#journal#beauty

21 notes

·

View notes