#because even though they have literally the vast majority of the world as their playground

Text

Perpetually annoyed by the attitude straight women have about gay men and the gay men who encourage it 😒

#it’s the F*g Hag phenomenon yall#and it’s a sickness#I say this as a gay woman so don’t come for me#they like to latch onto lgbt culture and spaces and make it part of their own personality#because even though they have literally the vast majority of the world as their playground#lord forbid there be a tiny minority space they’re not allowed to be a part of#whether it’s shipping or celebrity stanning or using their irl gay friends as part of their aesthetic#it’s just so ingrained in them#the using gay men as accessories the commodifying the exploiting the leeching the boundary issues the passive homophobia#mind you they all have one of 3 attitudes toward queer women#either they’re grossed out and uncomfortable around us#or they just don’t ever acknowledge us and pretend like we don’t exist#OR they try to add us in there at the last minute to get a few more woke points without ever obsessing over us the way they do queer men#cause we just don’t fit that little slot they’re looking to fill#they’re so fucking obsessed with gay guys it’s not ever funny#but only as long as they gay guys play the role of their token bestie and act femme and like watching stage race with them#because media has taught us that that’s a gay man’s only role#I hate it here#rant over#it’s just… y’all this is EVERYWHERE#it’s so much more common these days than just run of the mill homophobia#(and yes I 100% meant to imply that this weird fetishising thing is ALSO a form of homophobia)#and yes Ik straight men have a toxic ass attitude toward gay women but that’s a whole other post#sigh#gay men#straight women#lgbt#stop fetishizing gay men#gay bestie#lgbt discourse

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sig’s Anthem Review

Verdict

BioWare’s Anthem is a genuinely fun and engaging experience that sabotages itself with myriad design, balance, and technical oversights and issues. It is a delicious cake that has been prematurely removed from the developmental oven - full of potential but unfit for general consumption in this wobbly state. Anthem is not a messianic addition to the limited pantheon of looter shooters because it has somehow failed to learn from the well-publicized mistakes of its predecessors.

Am I having fun playing Anthem? Absolutely. Does it deserve the industry’s lukewarm scores? Absolutely. But this is something of a special case. The live service model giveth and taketh away; we receive flexibility in exchange for certainty. Is Anthem going to be the same game six months from now? Its core DNA will always be the same, but we’ve already begun to see swift improvements that bode well for the future.

Will my opinion matter to you? It depends. When I first got into looter shooters I was shocked at how much the genre clicked with me. They are a wonderful playground for theory crafters, min/maxers, and mathletes like myself who find incomparable joy in optimizing builds both conventional and experimental by pushing the limits of obtainable resources ad infinitum. The end game grind is long and at times challenging as you make the jump to Grandmaster 1+ difficulty in search of top-tier loot to perfect your build. This is what looter shooters are all about.

If you don’t like the sound of that, you’ll probably drop Anthem right after finishing its campaign. But if you do like the sound of that, you might find yourself playing this game for years.

TL;DR: This game is serious fun, but is also in need of some serious Game & UI Design 101.

I wrote a lot more about individual aspects of the game beneath the read more, if you’re interested. I’ve decided not to give the game a score, I’m just here to discuss it after playing through the campaign and spending a few days grinding elder game activities. There are no spoilers here.

Gameplay

The Javelins are delightful. I’ve played all four of them extensively and despite identifying as a Colossus main I cannot definitively attach myself to one class of Javelin because they’re all so uniquely fun to play and master. Best of all, they’re miraculously balanced. I’ve been able to hold my own with every Javelin in Grandmaster 1+. Of course, some Javelins are harder to get the hang of than others. Storms don’t face the steep learning curve Interceptors do, but placed in the hands of someone who knows what they’re doing, both are equally as destructive on the battlefield.

I love the combo system. It is viscerally satisfying to trigger a combo, hearing that sound effect ring, and seeing your enemy’s health bar melt. Gunplay finally gets fun and interesting when you start obtaining Masterworks, and from there, it’s like playing a whole new game.

Mission objectives are fairly bland and repetitive, but the gameplay is so fun I don’t even mind. Collect this, find that, go here, whatever. I get to fly around and blow up enemies while doing it, and that’s what matters. Objectives could be better, certainly. Interesting objectives are vital in game design because they disguise the core repetitive gameplay loop as something fresh, but the loop on its own stays fresh long enough to break even, I feel.

The best part is build flexibility. Want to be a sniper build cutting boss health bars in half with one shot? I’ve seen it. Want to be a near-immortal Colossus wrecking ball who heals every time you mow down an enemy? You can. There are so many possibilities here. Every day I come across a new crazy idea someone’s come up with. This is an excellent game for build crafters.

But... why in the world are there so few cosmetic choices? A single armor set for each Javelin outside the Vanity store? A core component of looter shooters has always been endgame fashion, and on this front, BioWare barely delivers and only evades the worst criticism by providing quality Javelin customization in the way of coloring, materials, and keeping power level and aesthetics divorced. We’re being drip-fed through the Vanity store, and while I like the Vanity store’s model, there should have been more things permanently available for purchase through the Forge. Everyone looks the same out there! Where’s the variety?

Story, Characters, World

Anyone expecting a looter shooter like Anthem to feature a Mass Effect or Dragon Age -sized epic is out of their mind, but that doesn’t mean we have to judge the storytelling in a vacuum. This is BioWare after all. Even a campaign that flows more like a short story - as is the case with Anthem - should aspire to the quality of previous games from the studio. Unfortunately, it does not, but it comes close by merit of narrative ambience: the characters, the world’s lore, and their execution.

(For a long time I’ve had a theory that world building is what made the original Mass Effect great, not its critical storyline, which was basically a Star Trek movie at best. Fans fell in love because there were interesting people to talk to, complicated politics to grasp, and moral decisions to make along the way.)

While the main storyline of Anthem is lackluster and makes one roll their eyes at certain moments or bad lines, the world is immediately intriguing. Within Fort Tarsis, sophisticated technology is readily available while society simultaneously feels antiquated, echoing a temporal purgatory consistent with the Anthem’s ability to alter space-time. Outside the fort, massive pieces of ancient machinery are embedded within dense jungles in a way that suggests the mechanical predates nature itself. The theme of sound is everywhere. Silencing relics, cyphers hearing the Anthem, delivering echoes to giant subwoofers… It’s a fun world, it really is.

As for the characters… they might be some of the best from BioWare. They feel like real people. Rarely are they caricatures of one defining trait, but people with complex motives and emotions. Some conversations were boring, but the vast majority of the time I found myself racing off to talk to NPCs as soon as I saw yellow speech bubbles on the map after a mission. And don’t even get me started on the performances. They are golden.

The biggest issue with the story is that it’s not well integrated with missions. At times it feels like you’re playing two separate games: Fort Tarsis Walking/Talking Simulator and Anthem Looter Shooter. And the sole threads keeping these halves stitched together during missions - radio chatter - takes a back seat if you’re playing with randoms who rush ahead and cause dialogue to skip, or with friends who won’t shut the hell up so you can listen or read subtitles without distraction. I found it ironic that I soloed most of the critical story missions in a game that heavily encourages team play.

Technical Aspects: UI & Design

This is where Anthem has some major problems. God, this category alone is probably what gained the ire of most reviewers. The UI is terrible and confusing. There are extra menu tabs where they aren’t needed. The placement of Settings is for some inane reason not located under the Options button (PS4). Excuse me? It’s so difficult to navigate and find what you’re looking for. It’s ridiculously unintuitive.

Weapon inscriptions (stat bonuses) are vague and I’ve even seen double negatives once or twice. They come off as though no one bothered to proofread or edit anything for clarity. Just a bad job here all around. And to make matters worse, there is no character stat sheet to help us demystify any of the bizarre stat descriptions. We are currently using goddamn spreadsheets like animals. Just awful.

The list goes on. No waypoints in Freeplay. Countless crashes, rubber banding, audio cutouts, player characters being invisible in vital cutscenes, tethering warnings completely obscuring the flight overheat meter… Fucking yikes. Wading through this swamp of bugs and poor design has been grueling to say the least.

And now for the loot issues. Dead inscriptions on gear; and by dead I mean dead, as in “this pistol does +25% shotgun damage” dead (this has been recently patched but I still cannot believe this sort of thing made it to release). The entire concept of the Luck stat (chance to drop higher quality loot) resulting in Luck builds who drop like flies in combat and become a burden for the rest of the team. Diminishing returns in Grandmaster 2 and 3; it takes so long to clear missions on these difficulties without significant loot improvement, making GM2 and GM3 pointless when you could be grinding GM1 missions twice as fast.

At level 30, any loot quality below Epic is literal trash. Delete Commons, Uncommons, and most Rares as soon as you get them because they’re virtually useless. I have hundreds of Common and Uncommon embers and nothing to do with them. Why can’t we convert 5 embers into 1 of the next higher tier? Other looters have already done things like this to make progression omnipresent. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel here, BioWare. It’s already been done for you.

When you get a good roll on loot, the satisfaction is immense. But when you don’t, and you won’t 95% of the time, you’ll feel like you’ve wasted hours with nothing to show for it. We shouldn’t be spending so much time hunting for useful things, we should be trying to perfect what’s already useful.

It’s just baffling to think that Anthem had the luxury of watching the messy release of several other looter shooters during Anthem’s development, yet proceed to make the same mistakes, and some even worse.

Nothing needs to be said about visuals. They are stunning, even from my perspective on a base PS4.

Sound design is the only other redeeming subcategory here. Sound design is amazing, like the OST. Traditional instrumentals meet alien synth seamlessly. Sarah Schachner is a seriously talented composer.

I’m just relieved to see the development team hauling ass to make adjustments. They’ve really been on top of it - the speed and transparency of fixes has been top-notch. They’re even working on free DLC already! A new region, more performances from the actors... I’m excited and hopeful for the future.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vampires

Most people today are familiar with the basic concept of a Vampire, but over the years a lot of the lore has become convoluted and confused due both to the vast array of different types of vampire and the media’s portrayal of them.

So a few things to keep in mind before I get into the details:

First, despite what the recent media tells you, there isn’t an inkling of humanity left in Vampires; once they become what they are, humans become food and tools. I will admit that some of the older ones, the ones who choose to contain their appetites, can operate in a grey area of the world, but they are still to be treated the same way you should a wild predator.

Second, and I cannot stress this enough, Vampires shouldn’t be “poked” any more than a grizzly bear should be, not unless it’s your plan to become their next meal.

Lastly, and I can’t believe I even have to say this, Vampires do not sparkle; I almost decked the last person to ask me that.

No one around really knows when or where exactly the first cases of Vampirism began, but by the 1340s with the rise of the black plague, they had become widespread across Europe, making them the perfect scapegoats for the spreading disease. When humans face something they fear, they turn to fantasy, trying to find a way to control something they don’t fully understand; this combined with an inadequate understanding of how a body decomposes let to a series of “Vampire scares” through the centuries coinciding with plague outbreaks. As a body decomposes, the skin shrinks, pulling the gums and other edges back creating the illusion that the teeth and nails have grown, add to this the fact purge fluid created by the internal organs breaking down will sometimes leak from the nose and mouth and it’s not a huge stretch for people of the time to assume the person had risen from the grave to feed on someone. With present day knowledge, such beliefs are almost comedic, but these were much darker times.

Because Vampires have been around for so long they, or rather the Vampire virus, have had the chance to mutate and adapt to different environments across Europe much in the same way any other animal would, a common example being birds on the Galapagos Islands, and just as each culture has their own variation of the Vampire, they each developed their own ways to prevent the Vampire’s rise. Of course, as most of the populations across Europe didn’t fully understand just what a Vampire is, these methods are generally far fetched and ineffective.

In Italy, home to the Strega, plague victims were often buried with bricks in their mouths in an attempt to prevent them from rising again. Germany, where the Nachzehrer generally remained in their graves to chew on their burial shrouds (according to the stories, though actually not quite accurate), they were accused of attacking their surviving relatives through “occult processes” by a Protestant theologian in his tract “On the Chewing Dead” published in 1679. Whether his accusations were founded or not, it led to the exhumation of numerous bodies so that the family could stuff the corpse’s mouth with soil, adding a stone or coin for good measure in an attempt to starve and kill the assumed threat. Though ineffective when it came to warding off attacks by the Nachzehrer, the process did disrupt quite a few trapped spirits causing a sharp rise in poltergeist level activity in the area for a good decade or two after. In the 18th and 19th centuries, a common “anti-vampire” tactic was to remove and burn the heart of the accused vampire, who thankfully was already dead, and mix the ashes into a potion for the afflicted to drink. I doubt it tasted at all okay, but the upside to this practice was that, barring the accidental addition of something that is, in fact, poisonous, the potion likely wasn’t going to kill anyone.

Bram Stoker learned of the story from a friend and scholar and was inspired to pen Dracula, one of the greatest works of fiction involving vampires ever written using a combination of details from the original story and old Irish myths of Vampires and the rest, as they say, is history.

Much of the modern practices when it comes to effectively handling Vampires come from Romania, home to the infamous Vlad Tepes, or Vlad Dracula. Before Vlad Tepes came along though, Romania was home to one of the most brutal and dangerous species of Vampires: the Strigoi. The Strigoi were a big enough threat that Romanian hunters had spent years developing rituals to protect against the Strigoi, but it wasn’t until Vlad Tepes came along that they actually found a way to kill a Vampire. Vlad Tepes ruled Wallachia three times between 1448 and his death and he is highly thought of despite his penchant for putting criminals on stakes, but towards the end of his known life, he contracted the Vampire virus and so began his reign of terror. For centuries, Vlad Tepes hunted the people he had once ruled until Georg Andreas Helwing, a clergyman, physician, and the true life counterpart to Bram Stoker’s Van Helsing, traveled to Romania with the notes from his research on werewolves and vampires, including an anti-vampire technique practiced in Masuria (a region in Prussia that is now a part of Poland) that involved decapitating the corpse’s head and driving a wooden stake through their heart. After a meeting with Helwing, a small band of hunters decided to test the method on Dracula himself, successfully decapitating and staking him to become the first hunters to kill a Vampire. So miraculous was the feat that Dracula’s severed head was paraded through the streets on the end of a pike to show the world that Vampires were not, in fact, immortal as previously thought.

Even though there are a wide variety of different species that all classify as “Vampire”, not all of them drink blood. In broad terms, Vampires feed on the life force of living creatures either via a psychological link or by literally going out and hunting down their prey depending on which species of Vampire they are. Romanian Strigoi and Italian Strega, for example, are both more active feeders while the German Nachzehrer and the first vampires of the colonies are more passive, preferring instead to remain in their nests to feed.

Despite their differences, all Vampires come from the same place; Vampirism is a virus. When someone contracts the virus via the swapping of genetic material like when a Vampire bites someone, it will attack and rewrite the victim’s DNA. This is why Vampires rarely, if ever, feed directly from an open wound, most of them are territorial and prefer not to share their meals or territory with more than a handful of close “family” members and so will not risk turning a stray human. The virus, once in the human’s body, will have an incubation period of one or two months while it prepares the body for the final change, during which time the victim will become hypersensitive to sunlight along with anything that could generally be used to detoxify or purify a person’s system, like garlic, water, cilantro, and certain holy items. After the incubation period, the victim’s body will enter a sort of limbo state during which all body function will appear to cease, though it’d be more accurate to say the body had become like a cocoon for a man eating butterfly. While in this state of limbo, the victim’s body will take on physical changes, for example, the subconscious limits placed on the bodies muscles will be deactivated, essentially granting “superhuman” speed and strength, the canines will become more like a snake’s fangs, hinged and razor sharp, the eye structure will change to better suit nocturnal habits, and most importantly a majority of the bodily systems will shut down entirely. When a vampire feeds, the blood or life force they consume now goes directly into their cardiovascular system. After they wake up a fully fledged Vampire, the person can no longer process any “food” outside of blood and their previous aversion to garlic, holy water, cilantro, etc. will no longer have any effect, though they will continue to avoid sunlight whenever possible.

When a person first contracts Vampirism, they will have to be purged of the virus before entering the limbo state, meaning the often painful consumption of everything a soon to be Vampire can’t handle. If done correctly, the victim will eventually become feverish before passing out to spend the next few days sweating the rest of the virus from their system. Once a Vampire has become a fully fledged Vampire, there is no going back and the person will have achieved a form of false immortality, although as we know now, they can be killed by decapitating the head or driving an aspen wood stake through their heart. Another method, if the opportunity arises, is to simply burn them away using a magnifying glass and the sun just like burning ants in the playground. A Vampire’s body becomes more and more like paper the older they get, with some of the more ancient vampires bearing almost translucent skin, making them highly flammable; all that’s needed is a little heat and there’d be nothing left but ash. Due to this incredibly dry skin, a dead Vampire will be incinerated the second the sunlight touches it’s corpse, making cleaning up after a hunt quick and easy.

#vampire#om&n#beasts#beast#monster#hunter#monsters#blood#strigoi#dracula#of monsters and nothing#of monsters & nothing#reyna#wildes#journal#hunting journal#hunt#virus#strega#plague#the chewing dead#undead#immortal#writer#write#writing#fiction#bram stoker#vlad#tepes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

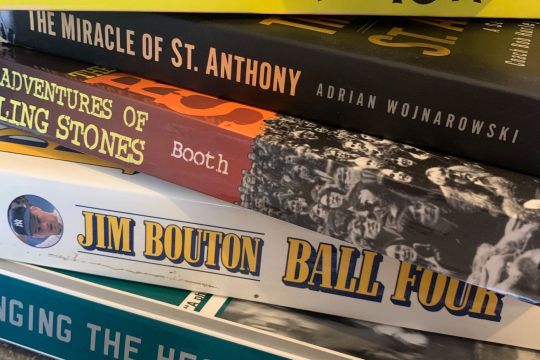

24 great books for quarantined sports fans

From ‘Ball Four’ to ‘Out of Sight’, here are a few books you can come back to over and over again

I love my books. They have traveled with me across the country and back again, prominently displayed in cheap bookcases throughout dozens of apartments around the Northeast. Currently, they are stretched out behind me in my home office where they will stay until the time comes to move off the grid. They will follow me there, as well.

I have read all of them at least once and several of them dozens of times. During periods of my life when I was without human companionship they were literally my only friends. That’s not said for sympathy. The life of a newspaper sportswriter in the 90s and early 2000s involved shitty hours and weekends, which pretty much negated any hopes of having a social life.

Through it all, my books were there for me. They demanded nothing but my time and gave me hours of entertainment.

I’m not particularly proud of my collection. There is very little literature to be found and only a handful of what one might refer to as great works. It mainly comprises sports books, rock star biographies, and a nearly complete set of Elmore Leonard novels.

Most of them are several decades old because I had to stop buying books at some point when I began to run out of room. I’m not linking to them because you can hopefully find an independent bookstore near you that would be thrilled for the business. Do them and humanity a favor.

Here are some of my favorites.

BASKETBALL

The Breaks of the Game: David Halberstam

This is the monster of all sports books, the one against which every basketball book is competing with in one way or another. If you know nothing of the NBA pre-LeBron James, this is where you should start. It’s a window into what feels like another universe, when pro basketball was a cult sport struggling for survival.

Loose Balls: Terry Pluto

I wrote about this one at length and won’t belabor the points I made back before the world came to a screeching halt. If you can’t get into the stories contained within these pages, I frankly don’t want to know you.

The Macrophenomenal Pro Basketball Almanac: The FreeDarko collective

It’s an exaggeration to say every person who heard the first Velvet Underground album went out and formed a band, just as it is to suggest that every writer who consumed FreeDarko wound up writing about basketball on the internet. But almost everyone who did was influenced by them.

The Miracle of St. Anthony: Adrian Wojnarowski

Long before he was the great and powerful Woj, the author spent an entire season with Bob Hurley’s St. Anthony Friars. It’s a masterful bit of storytelling that for my money is the absolute best of the surprisingly robust sub-genre of books about high school basketball.

Other contenders include The Last Shot by Darcy Frey, Fall River Dreams by Bill Reynolds and In These Girls, Hope is a Muscle by Madeleine Blais.

The Jordan Rules: Sam Smith

Judging from the early reactions to the gigantic Bulls documentary, it’s quite clear a lot of you should get familiar with the source material. Smith’s book was shocking upon its release because it dared show Michael Jordan as he really was, without the buffed out Nike shine. It holds up, clearly.

Halbertsam’s Playing for Keeps picks up the story in 1998 and provided much of the narrative structure of the first two episodes.

Heaven is a Playground: Rick Telander

An all-time classic set on the courts of mid-1970s Harlem during a long, hot summer. There are a lot of books that tried to get at the soul of basketball, but this is the standard bearer. I’d really like to know whatever became of Sgt. Rock.

Others in this vein include The City Game by Pete Axthelm, Pacific Rims by Rafe Bartholomew and Big Game, Small World by Alexander Wolff.

Second Wind: Bill Russell

The best athlete autobiography of all time.

BASEBALL

Lords of the Realm: John Heylar

The inside story of how baseball owners conspired for almost a century to suppress salaries while refusing to integrate. It’s shocking how buffoonish management acted during the glory days of the national pastime. Required reading.

Marvin Miller’s A Whole New Ballgame is a worthy companion piece, as is Bill Veeck’s delightful, Veeck as in Wreck.

Ball Four: Jim Bouton

Scandalous upon its release in 1970, Ball Four contains the best line ever written in any sport book: “You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”

I read Ball Four for the first time in fifth grade and immediately taught my classmates the words to “Proud to be an Astro”:

Now, Harry Walker is the one who manages this crew

He doesn’t like it when we drink and fight and smoke and screw

But when we win our game each day,

Then what the fuck can Harry say?

It makes a fellow proud to be an Astro

Seasons in Hell: Mike Shropshire

There is nothing more soul-crushing than spending an entire season with a bad team. Shropshire covers three hilariously inept campaigns with the Texas Rangers, who as then-manager Whitey Herzog noted: “Defensively, these guys are really sub-standard, but with our pitching it really doesn’t matter.”

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning: Jonathan Mahler

An underrated late addition to the pantheon that tells the story of the 1977 Yankees amid the backdrop of a city gone to hell.

You will notice there are few books in my collection about modern baseball. There’s a reason for that. The vast majority of them are peans to the wonders of middle management and therefore boring as hell.

FOOTBALL

Playing For Keeps: Chris Mortsensen

The incredibly bizarre — and largely forgotten — story of how the mob tried to gain influence in pro football via a pair of shady agents named Norby Walters and Lloyd Bloom. Good luck finding it.

Bringing the Heat: Mark Bowden

You may recognize Bowden from such masterworks as Black Hawk Down and Killing Pablo. You probably don’t remember that he spent a year with the Eagles after the death of Jerome Brown. As honest and unflinching a look at pro football as you will ever find.

North Dallas Forty: Peter Gent

The only piece of sports fiction on my list is not so fictional at all. Gent’s thinly-veiled account of his own life as a receiver for Tom Landry’s Cowboys is shocking and brutal and sad and poignant. I make time to read it every year.

I used to have more football books, back when I cared about the sport.

MEDIA

Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail: Hunter S. Thompson

The Vegas one is more popular and Hell’s Angels is a stronger work of reportage, but for a dose of pure Gonzo insanity, this is the book I come back to more often than not.

The Boys on the Bus: Timothy Crouse

The companion piece to Thompson’s lurid account, Crouse plays it straight and lays bare the bullshit facade of campaign reporting. Almost 50 years later, we have still learned nothing.

The Franchise: Michael McCambridge

Details the glory days of Sports Illustrated, reading it now feels like an obituary. It was fun once, this business of writing about sports.

MUSIC

Heads, a Biography of Psychedelic America: Jesse Jarnow

My favorite book of the last few years, Jarnow takes us on a bizarre trip through the byzantine world of psychedelic drug networks connecting it through the career of the Grateful Dead and into modern-day Silicon Valley. I’m waiting for the followup on Dealer McDope.

Not music, but as a companion piece, Nicholas Schou’s Orange Sunshine tells the even-crazier tale of The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, who took over the LSD trade and invented hash smuggling by stuffing surfboards with primo Afghani hash and shipping them back to California.

The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones: Stanley Booth

Reported while on tour with the Stones at the height of their powers circa Let it Bleed, Booth took 15 years to write the damn thing. By then the Stones were already an anachronism. It’s all there, though. Sex, drugs, more drugs, and unbelievable access to the biggest rock ‘n roll band in the world.

This Wheel’s on Fire: Levon Helm with Stephen Davis

In which Brother Levon disembowels Robbie Robertson and exposes the lie at the heart of The Band. Robbie took the songwriting credit and all the money.

Satan is Real: Charlie Louvin

Astonishingly good read that is best consumed with Charlie and his brother Ira playing low in the background.

Mainlines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader

Lester is an acquired taste and not all of his ramblings hold up. I will always love him for despising Jim Morrison and completely nailing what made Black Sabbath important. Spoiler: They were moralists like William S. Burroughs.

Please Kill Me: Legs McNeil and Gillian Welch

The definitive oral history of punk rock, an essential document of a scene that launched a thousand mediocre bands and the Ramones, who ruled.

Shakey: Jimmy McDonough

A tour-de-force biography of Neil Young that loses steam toward the end when McDonough makes himself the subject. The stuff about Neil’s bizarre 80s period and his relationship with his son is heartbreaking.

Our Band Could Be Your Life: Michael Azerrad

Pretty much everything you need to know about bands like Mudhoney, Black Flag and Mission of Burma who wove together the musical underground through a patchwork collection of local scenes back when something like that was still possible.

ELMORE LEONARD

You can’t go wrong with anything Leonard writes, but Out of Sight is as good a place to start as any.

0 notes

Link

‘It Seems That I Know How the Universe Originated’

The theoretical physicist Andrei Linde may have the world’s most expansive conception of what infinity looks like.

Alan Lightman February 8, 2021

In Jorge Luis Borges’s story “The Book of Sand,” a mysterious Bible peddler knocks on the narrator’s door and offers to sell him a sacred book he came by in a small village in India. The book shows the wear of many hands. The stranger says that the illiterate peasant who gave it to him called it The Book of Sand, “because neither sand nor this book has a beginning or an end.” Opening the volume, the narrator finds that its pages are rumpled and badly set, with an unpredictable Arabic numeral in the upper corner of each page. The stranger suggests that the narrator try to find the first page. It is impossible. No matter how close to the beginning he explores, several pages always remain between the cover and his hand: “It was as though they grew from the very book.” The stranger then asks the narrator to find the end of the book. Again, he fails. “This can’t be,” says the narrator. “It can’t be, but it is,” says the Bible peddler. “The number of pages in this book is literally infinite. No page is the first page; no page is the last.” The stranger pauses and reflects. “If space is infinite, we are anywhere, at any point in space. If time is infinite, we are at any point in time.”

Sign up for The Atlantic’s daily newsletter.

Each weekday evening, get an overview of the day’s biggest news, along with fascinating ideas, images, and voices.

Email Address (required)

Thanks for signing up!

Thoughts of the infinite have mesmerized and confounded human beings through the millennia. For mathematicians, infinity is an intellectual playground, where an endless string of fractions can add up to 1. For astronomers, the question is whether outer space goes on and on and on. And if it does, as most cosmologists now believe, unsettling consequences abound. For one, there should be an infinite number of copies of each of us somewhere out there in the cosmos. Because even a situation of minuscule probability—like the creation of a particular individual’s exact arrangement of atoms—when multiplied by an infinite number of trials, repeats itself an infinite number of times. Infinity multiplied by any number (except 0) equals infinity.

Recommended Reading

The Universe Is as Spooky as Einstein Thought

Natalie Wolchover and Quanta

The Multiverse Idea Is Rotting Culture

Sam Kriss

A sphere of small particles expands and contracts against a black background.

The Big Bang May Have Been One of Many

Natalie Wolchover

Measurements of infinity are impossible, or at least impossible according to the usual notions of size. If you cut infinity in half, each half is still infinite. In an imaginary scenario known as “Hilbert’s grand hotel,” if a weary traveler arrives at a fully occupied hotel of infinite size, no problem. You simply move the guest in room 1 into room 2, the guest in room 2 into room 3, and so on ad infinitum. In the process, you’ve accommodated all the previous guests and freed up room 1 for the new arrival. There’s always room at the infinity hotel.

The cover of Alan Lightman's forthcoming book, Probable Impossibilities

This post was excerpted from Lightman’s forthcoming book.

We can play games with infinity, but we cannot visualize it. By contrast, we can visualize flying horses. We’ve seen horses, and we’ve seen birds, so we can mentally implant wings on a horse and send it aloft. Not so with infinity. Its “unvisualizability” is part of its mystique.

One of the first recorded conceptions of infinity seems to have occurred around 600 B.C., when the Greek philosopher Anaximander used the word apeiron, meaning “unbounded,” or “limitless.” For Anaximander, the Earth and the heavens and all material things were caused by the infinite, although infinity itself was not a material substance. About the same time, the Chinese employed the word wuji, meaning “boundless,” and wuqiong, meaning “endless,” and believed that the infinite was very close to nothingness. In Chinese thought, being and nonbeing, like yin and yang, are in harmony with each other—thus the kinship of infinity and nothingness. A few centuries later, Aristotle argued that infinity does not actually exist, though he conceded something he called “potential infinity.” The whole numbers are an example. For any number, you can always create a bigger number by adding 1 to it. This process can continue as long as your stamina holds out, but you can never get to infinity.

Read: We need a new word for infinite spaces

Indeed, one of the many intriguing properties of infinity is that you can’t get there from here. Infinity is not simply more and more of the finite. It seems to be of a completely different nature, although pieces of it may appear finite, such as large numbers or large volumes of space. Infinity is a thing unto itself. Everything we see and experience has limits, boundaries, tangibilities. Not so with infinity. For similar reasons, St. Augustine, Baruch Spinoza, and other theological thinkers have associated infinity with God: the unlimited power of God, the unlimited knowledge of God, the unboundedness of God. “God is everywhere, and in all things, inasmuch as He is boundless and infinite,” said Thomas Aquinas. Beyond the religious sphere of the immaterial world, physicists believe that there might be infinite things in the material world as well. But this belief can never be proved. You can’t get there from here. Most of us have our first glimmerings of infinity as children, when we look up at the night sky for the first time. Or when we go to sea, out of sight of land, and gaze upon the ocean extending on and on until it meets the horizon. But these are only glimmerings, like counting to a few thousand in Aristotle’s potential infinity. We’re overwhelmed. But we haven’t even come close.

The concept of infinity remains controversial and paradoxical today, galvanizing international conferences and heated scholarly disputes. Can physical forces ever be infinite in strength? Can space be dissected into smaller and smaller pieces indefinitely, an infinity of the small? At the other end, can physical space extend beyond galaxy after galaxy without limit? Is there an infinity between the infinity of the whole numbers and the infinity of all numbers? In May 2013, a panel of scientists and mathematicians gathered in New York City to discuss the profound conundrums surrounding infinity. William Hugh Woodin, a mathematician at the University of California at Berkeley, put it this way: “It’s kind of like mathematics lives on a stable island—we’ve built a solid foundation. Then, there’s the wild land out there. That’s infinity.”

The person on planet Earth who may have come up with the most expansive conception of spatial infinity is the theoretical physicist Andrei Linde, a professor at Stanford University. Linde works only with pencil and paper. Now 72 years old, he was born and grew up in Moscow and received his Ph.D. in physics there from the Lebedev Physical Institute. Both of his parents were physicists. He married a physicist, Renata Kallosh (also a professor at Stanford). In 1990, Linde and Kallosh moved to the United States and took up their current academic positions.

In the 1980s, Linde proposed a radical theory of the origin of the universe.

His theory, a revision of the MIT physicist Alan Guth’s 1981 theory, itself a revision of the 1927 Big Bang model, is called “eternal chaotic inflation.” The theory posits that in its infancy, our universe went through a period of highly rapid expansion, much faster than in the standard Big Bang model. In a tiny fraction of a second, a region of space smaller than an atom “inflated” to a size large enough to encompass all the matter and energy we can see today. That much of the inflation theory was articulated in Guth’s paper. Linde’s theory goes further. It proposes that our universe is necessarily one of a vast number of universes, each of which is constantly and randomly spawning new universes in an unending chain of cosmic creation, extending into the future for eternity. Some of those universes, and perhaps our own, should be infinite in extent. In our particular universe, the period of highly rapid expansion would have been completed and done with when our universe was 0.000000000000000000000000000000001 seconds old.

Read: The best explanation for everything in the universe

One could easily dismiss such speculations as science fiction. But the fantastic speculations of scientists have often found a grip on reality. Two hundred years ago, who would have thought we would be able to decipher the microscopic chemical code that creates living organisms and to alter that code as if rearranging a deck of cards? Or build tiny boxes that could communicate pictures and voices through space? Linde’s speculations are backed up by serious equations, and a number of important predictions of what I will call the “Guth-Linde inflation theory” have been confirmed by experiment. In the scientific community, Linde is widely regarded as a physicist of the first rank. He has won most of the major prizes in physics except for the Nobel.

Linde does not have a small opinion of himself. When I met him the first time, in 1987, a few years after his most important work on the inflation theory, he told me about his discovery with these words:

I easily understood what Guth was trying to do. But I did not understand how [inflation] could be done, since we have seen that the inhomogeneities [in Guth’s original theory] were large [contradicting observations]. I just had the feeling that it was impossible for God not to use such a good possibility to simplify His work, the creation of the universe … I was simultaneously discussing similar matters with [Valery] Rubakov [by telephone] … I was sitting in my bathroom, since all my children and my wife were already sleeping at the time … After the whole picture had crystallized, I was very excited. I came to my wife and I woke her up and I said: “It seems that I know how the universe originated.”

I visited Linde recently at his home in Stanford, California, to get an update on his theory and its place in our view of the world. Linde and his wife live in a lush neighborhood of winding streets, tropical gardens, and houses set up on hills. He was casually dressed in a black fleece sweater over a black T-shirt, black pants, and sandals with black socks—all in dramatic contrast with his snow-white hair. His English is good but retains a thick Russian accent. We sat at his kitchen table.

First, I asked Linde if he believes that spatial infinity truly exists. (Theoretical physicists and mathematicians are infamous for building hypothetical universes of 17 dimensions and other such surrealities.) “Do you think dinosaurs truly existed?” he replied, and paused. “Everything works as if spatial infinity exists.” Linde is careful with language. He distinguishes between reality, which we can never know, and our models and inferences about reality. He has always had a strong interest in philosophy. He remembers having debates with high-school classmates about science versus art.

I asked him how he thought about infinity, whether he attempted to visualize it. “No matter how far you go, you can go farther,” he said. Then he made an analogy to a garden: “But there’s no fence.”

Anaximander’s conception of infinity was abstract and could not reasonably be associated with physical space. In fact, the early Greek philosophers pictured the cosmos as limited in size, with an outer boundary, although they did not claim to know the actual distances.

The first person to postulate in concrete terms a spatially infinite universe seems to have been a 16th-century English mathematician and astronomer named Thomas Digges. In 1576, Digges published a new edition of his late father’s almanac, A Prognostication Everlasting. In an appendix, Digges abolished the outer sphere of the stars. At the center of his diagram is the face of the sun, with spiky rays issuing forth. Then the “orbes” of the planets. And beyond this region and extending to the edge of the page are the stars, scattered here and there through infinite space.

Digges agreed with Copernicus and Aristotle about one thing: The cosmos on the whole was at rest—a magnificent and immortal cathedral. It had existed forever and would exist forever, from the infinite past to the infinite future. This conception sat quietly for another 300 years. Even Albert Einstein’s 1917 cosmological model, based on his new theory of gravity, proposed a static and eternal universe.

Then came the Big Bang. In 1927, a Belgian priest and physicist named Georges Lemaître suggested that the previously observed outward motion of galaxies meant the universe was expanding. The cosmos was not, in fact, static. Einstein pronounced the idea “abominable.” However, two years later, Lemaître’s suggestion was confirmed by the American astronomer Edwin Hubble, who found that the speed at which other galaxies are flying away from us is proportional to their distance, as if all the galaxies were dots painted on an expanding balloon. From the viewpoint of any dot, it appears that all the other dots are moving away. No dot is the center.

Read: Why Earth’s history appears so miraculous

If you let the air out of the balloon—going backward in time—all the dots rush toward each other until you reach a moment in the past when all the dots are on top of each other. That moment is the “beginning” of the universe, the so-called Big Bang, t = 0. By measuring the rate at which the universe is expanding today, we can estimate when the universe “began”—about 14 billion years ago. Since that moment, the universe has been expanding, thinning out, and cooling. It is important to note that the balloon analogy is only an analogy. In particular, unlike a balloon, the universe could be infinite in extent. What astronomers mean when they say the universe is expanding is that the distance between any two galaxies is increasing with time.

The Big Bang model is more than an idea. It is a detailed set of equations describing how the universe has evolved since t = 0, specifying in quantitative detail such things as the average density and temperature of the universe at each point in time. The model has been supported by several pieces of evidence. For one, the age of the universe as calculated by its rate of expansion approximately agrees with the age of the oldest stars, calculated by our understanding of stellar astrophysics. For another, the Big Bang model predicts that there should be a flood of radio waves coming from all directions in outer space and produced when the universe was about 300,000 years old. That predicted flood of radio waves, called “cosmic background radiation,” was discovered in 1965. There are other confirmed predictions as well, such as the observed proportions of the lightest chemical elements. The Big Bang theory does not say whether space and time existed before the cosmic balloon began expanding. That profound question would be left to Linde and others.

Linde would have heard about the Big Bang model as a physics university student in Moscow in the late 1960s, if not earlier. However, he was trained not as a cosmologist but as a particle physicist, as was Alan Guth. Particle physicists study nature at the smallest sizes, while cosmologists study it at the largest. The two branches of physics seemingly had little to do with each other. But in the early 1970s, Linde became interested in certain phenomena that occur at extremely high temperatures, far beyond what can be created in the laboratory, temperatures that could have existed only in the fantastically hot conditions of the infant universe. Describing one of his theories at the time, a prelude to his work on inflation, Linde said, “At the first glance, this theory seemed to be too exotic. We developed it in 1972, but for two years nobody believed us. People were laughing.” But in 1974, some American physicists confirmed the main conclusions.

This response to Linde’s early work—first doubts, and then often acceptance—seems to have been a pattern in his career. In our conversation, we talked about the manner in which scientific theories, and especially maverick theories, are confronted by the scientific community. Linde described what he calls a strong “sociological” effect: the biases and prejudices of scientists, their institutional stature, and the inherent caution of the scientific enterprise. Linde himself is not a cautious person. His colleagues describe him as someone who shoots from the hip with lots of ideas, some right and some wrong. He is a person of extreme self-confidence, a showman in his popular lectures and articles.

By the early 1970s, some physicists were worrying about problems with the Big Bang model, despite its successes. One lasting concern, for example, was that the cosmic radio waves are highly uniform in temperature, no matter what direction we’re looking in.

There are two possible explanations for this: Either the universe began in an extremely uniform condition, with all parts at the same temperature, or any initial non-uniformities were smoothed out in time, much as hot and cold water in a bathtub will come to the same temperature by exchanging heat. However, heat exchange takes time. According to the Big Bang model, the different parts of the universe we see today would not have had enough time to exchange heat during the first 300,000 years of the universe, when the cosmic radio waves were created. Thus, the second explanation doesn’t work. On the other hand, physicists consider the first explanation unpalatable because it sweeps the problem under the rug: “It is what it is because it was what it was.” In general, physicists detest such arguments.

The Guth-Linde inflation theory solves the puzzle of the cosmic radio waves, as well as other problems with the Big Bang model. During the period when the infant universe was expanding at blinding speed, a very tiny patch of space, tiny enough that all its parts could have homogenized, would have quickly inflated to encompass today’s entire observable universe. No matter what the initial conditions, inflation would have produced a universe of uniform temperature.

Most important, the inflation theory explains why such inflation would occur and includes equations for the various energies and forces involved. The key ingredient of the theory, and the cause of the extremely rapid expansion of the infant cosmos, is a kind of energy called a “scalar field.” Most energy fields, like gravity, are invisible, yet they can exert forces. Some scalar fields produce a repulsive gravitational force: They push things apart rather than pull things together.

The Guth-Linde theory was developed over a period of several years, from 1979 to 1986, beginning with work by Alexei Starobinsky in Moscow. During that period, problems arose and were fixed, and physicists proposed various versions of the theory.

One of Linde’s ideas is that in the early universe, scalar field energy should be constantly created at various magnitudes due to quantum effects. A strange aspect of quantum physics is that energy and matter can suddenly appear out of nothing for short periods of time. If you could examine space with a strong enough microscope, you would find that it is constantly fluctuating, seething with ghost-like particles and energies that randomly appear and disappear. Quantum phenomena are normally apparent only in the tiny world of the atom, but near t = 0 the entire observable universe was smaller than an atom. If at a certain point in the infant universe sufficient scalar field energy had materialized, its repulsive gravitational effect would have caused space to expand so rapidly that an entire universe would have been created. Since such quantum fluctuations would have been going on at random places and times—this is the “chaos” in Linde’s eternal chaotic inflation theory—new universes would have been constantly forming.

Indeed, Linde’s theory requires that we redefine what we mean by universe.

Some physicists now take the word to mean a region of space that will be quarantined into the infinite future, that may have been in contact with other parts of the cosmos in the past but can never communicate with the rest of the cosmos again. Because of the mind-bending way in which gravity alters the geometry of space in Einstein’s theory, there could conceivably be multiple universes, each infinite in extent. Physicists predict that the new universes created by quantum fluctuations have a wide range of properties: Some might be infinite in extent, others finite; some might have the right conditions to make stars and planets and life; others might be lifeless and unformed deserts of subatomic particles and energy; some might even have different dimensions than our own universe. In this vision, universes endlessly spawn new universes, each with its own Big Bang beginning. Our t = 0 would not be the beginning of space and time in the larger cosmos, only in our particular universe.

Read: How to measure all the starlight in the universe

In some of his papers, Linde represents his eternal chaotic inflation model as a thick hedge of branching bulbs, each bulb a separate universe, connected to ancestor bulbs and descendant bulbs by thin tubes. The entire hedge might be called the “cosmos.” Sometimes, it’s called the “multiverse.” It is startling to look at Linde’s picture and realize that each bulb represents an entire universe, some containing stars and planets, cities, office buildings, trees, ants or ant-like creatures, sunsets. Unfathomable—yet a human mind has fathomed this thick hedge of the imagination. “It can’t be, but it is,” says the Bible peddler in “The Book of Sand.”

One cannot resist comparing Linde’s “map of the universes” to the Babylonian “Map of the World,” one of the oldest-known maps drawn by human beings, found on a clay tablet in present-day Iraq and now housed in the British Museum. In this ancient map of the known world (ca. 600 B.C.), the city of Babylon is perched on the Euphrates River. Pictured and named (in Akkadian) are a few other cities, including Urartu, Susa, Assyria, and Habban; a mountain; and a circular ocean (labeled “bitter river”) enveloping the inhabited cities.* Finally, spikes radiating out from the circular ocean represent some unnamed and unknown outer regions. Could one compare these unnamed spikes to the unnamed bulbs in Linde’s map? Both lie far beyond the realm of physical exploration. Both require leaps of the imagination. Yet Linde’s bulbs follow as logical consequences of certain mathematical equations. As Linde would acknowledge, those equations are also works of the human imagination, models of reality instead of reality itself. Linde’s ideas are at once visionary and grounded in logical thinking. Although mathematically proficient in the manner of all theoretical physicists, Linde described himself to me as more intuitive than technical, a Steve Jobs more than a Steve Wozniak.

The Babylonian Map of the World is a static picture. By contrast, Linde’s map of the universes suggests evolution and change, movement. The various universes spawn each other in time.

I do not feel unlimited looking at Linde’s map. Instead, I feel small and insignificant, like the Bible peddler, who says that if space is infinite, we are nowhere in space, nowhere in time. How can anything we do be of consequence when we are nowhere in space, nowhere in time, when our brief lives are lived out on one small planet, itself one of zillions of planets in a universe that might be infinite in size, and our entire universe simply one bulb in Linde’s thick hedge of universes? On the other hand, there might be something majestic in being a part, even a tiny part, of this unfathomable chain of being, this infinitude of existence. We pass away, our sun will burn out, our universe might become a dark and lifeless void a hundred billion years from now—but, according to Linde, other universes are constantly being born, some surely with life, renewing something precious that cannot be named.

It is unlikely that we will ever know if Linde’s infinity of universes exists. But the rest of the Guth-Linde inflation theory is being actively tested today. One of the most important tests, Linde explained to me, is a search for something called “B-mode polarization,” a slight twisting pattern in the vibrations of the cosmic radio waves predicted by the inflation theory.

Refined measurements of the B-mode polarization are now being conducted by the POLARBEAR experiment in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile and by the BICEP experiment at the South Pole, among others. These experiments are international collaborations, including more than a dozen institutions in the United States, England, Wales, France, Japan, and Canada. Thousands of scientists worldwide, both theorists and experimentalists, are actively working to test the inflation theory and to probe its consequences. Almost all cosmologists today accept it as the best working hypothesis we have to describe the first moments of our universe. The theory must be considered a triumph of the human mind.

Yet Andrei Linde does not appear to be a man completely at peace with his place in the world. Something eludes him. When he talks about the history of the inflation theory, he seems still to be defending his ideas against naysayers and rival theorists, still competing with Guth and others for priority of discovery, still infused with a powerful desire for vindication. In my conversations with him and in his review articles and autobiographical statements, he portrays himself as someone who heroically developed a new view of the cosmos, struggled against doubters, corrected other people’s mistakes and misunderstandings, and was often misunderstood himself. One story he enjoys telling is about a lecture that Stephen Hawking gave at the Sternberg Astronomical Institute in Moscow in October 1981. Linde was asked to translate for the Russian audience. At that time, various physicists, including Hawking, were trying to patch up a serious problem (too much inhomogeneity) in Guth’s original inflation theory. Linde had devised his own inflation theory, a revision of Guth’s, but it was not yet published. During the lecture, Hawking would mumble a few seemingly incoherent words, one of his graduate students familiar with his speech would translate into understandable English, and then Linde would translate into Russian. With this painfully slow process under way, Hawking announced that Linde had a good idea, but it was wrong. For the next half hour, he proceeded to explain why it was wrong. All the while, Linde had to translate. At the end of the lecture, Linde told the audience, “I have translated, but I disagree.” He then went with Hawking to another room of the building, closed the door, and explained to him more details of his new theory. According to Linde, Hawking had to admit that he was right after all. Linde recalled that Hawking “was sitting there about one hour and a half and saying to me the same words: ‘But you did not tell this before. But you did not tell this before.’”

Perhaps Linde’s ego and bravado were essential for the conception of his phantasmagoric cosmology. Other scientists with equal brainpower but more cautious dispositions have not ventured nearly so far in their theories of the world. The equations are the equations, but they must be imagined and interpreted in the human mind, a particular human mind, a complex universe itself, endlessly variable in its quirks and possibilities. Then again, any scientist who works on the origin of our universe—and hundreds do worldwide—must possess a certain amount of chutzpah.

“At the beginning, I was like a young kid, making discoveries,” Linde told me.

Now I feel a deep responsibility. There are hundreds of people working on the theory of inflation and lots [of expensive] experiments to test it. You feel yourself a bit heavy with responsibility … I would hate to die just being a physicist. I enjoy photography. That allows me to feel another part of my brain. There is something beyond physics that is not measurable … Photography is my art. You need to have a first priority and then a second priority. When I was 60, someone gave me a camera. With a camera, you can produce beauty. I can produce things that are better than what I see in museums. You see, I am now talking like an arrogant American. I am producing images that make my heart sing—both my photographs and the computer graphics illustrating inflation. I am among the first to see the beauty in it. Without the part of my mind beyond physics, I would be unable to create the computer graphics of cosmology.

Linde went to his computer and eagerly showed me his Flickr website, where he has posted hundreds of his photographs. “Sit down,” he said, and offered me a seat near the screen. One of his photographs, titled “Alcazar Dreams,” depicts a subterranean pool beneath the Patio del Crucero in Seville, Spain. A series of stone arches, glowing in eerie orange light, bend over the elongated pool, one after another after another out to a distant vanishing point. Another image, titled “Hide Thy Face,” is an extreme close-up of the interior of an orchid. Around the outside edges unfolds a diaphanous blue halo. At the middle of the flower is a two-chambered yellow heart covered with red speckles, with white-and-red-striped arms emerging from it, and further out pale green and yellow petals. Altogether, an intricate jewel, a tiny splash in infinity.

This article was excerpted from Lightman’s forthcoming book, Probable Impossibilities.

* This article previously misstated the language in which the Babylonian "Map of the World" was written and the material from which it was made.

👇 📚 👇

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/02/to-infinity-and-beyond/617965/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

0 notes

Text

So, you wanna know how a Plane is created and what the whole thing about the Great Society is? Big deal.

There’s not much to say about the “Highers’” (the tridimensional name they gave themselves. You can feel the superiority complex emanating from that word) society and culture, aside from the fact that they’re practically sorted into casts, depending on how powerful they are. It’s kinda tricky to figure from a human’s scale, but a reliable measurement standard can be erected by comparing how much power they can give to the Planes they create. The Great Society links this figurative “power” to a Level (Lv) which defines the Creator. The higher the level, the most respected and influential the guy is within the Society.

The “level” depends mostly on the Higher’s “experience” with their powers and all, but it also depends on their species— some Highers are naturally born more or less powerful than other species of Highers. That’s why there are casts to begin with. Because they’re “naturally” born unequal in power and all that.

Kinda also why they consider it to be normal to be “naturally smarter” and superior to any being made of less than twelve dimensions. Heh.

Along with the Level comes another concept that will be quite important for you to understand here— the ability for Highers to “manifest.”

To explain “Manifesting” with a more or less accurate metaphor, let’s say you’ve got that MMO network where you can create and manage your own city or planet or whatever, then confront it with your pals’ own creations. Let’s say that, even better, you actually get to visit your own creation’s realm by creating your own avatar persona! You can move the little avatar thingy around and about in your world and it looks just like the other NPCs you have— aside from the fact that you still have your Superpowers as the Player and Creator of that little place.

Well. “Manifesting” is basically the Highers’ avatar. They’re literally mindless puppets made of the exact same stuff as the Thirdlings living in their Plane (“Thirdling” being yet another derogatory word the Great Society came up with in order to designate tridimensional beings, ‘cause they’re so much smarter than everyone else), which the Highers can move around and about inside their Planes. Since they can’t physically reach a Plane made of less than twelve dimensions, “manifesting” is the only way for a Higher to physically interact with a Plane’s content, whether it be their own or another Higher’s.

Notice that having the possibility to “manifest” also means that the Higher has the potential of near-omnipotence within the entire Plane they’re manifesting in. That is to say, even if they’re not inside a Plane they created themselves, Highers manifesting inside a Plane can make just about whatever miracles they want happen, no matter how impossible they seem. Creating things out of thin air or rearranging molecules within seconds is their favorite trick.

Well, of course there are still rules; manifesting inside your neighbor’s Plane and wreaking havoc inside just for fun is a severe crime, and you REALLY don’t want to know what the Great Society’s courtrooms and penalties are like.

Another rule you might need to know about is the Non-Interference Policy. It’s purely juridical stuff, and quite a lame decision, since it basically forbids Highers from manifesting in Planes that aren’t part of the Union and which they aren’t related to. Communication with Thirdlings who don’t pertain to the Union or the Higher’s creation is strictly prohibited. And last but not least, inviting Thirdlings into a higher plane of existence — namely, Great Society soil, what you guys also love to call “the Void” for some reason — is potentially punishable by death penalty.

It’s not even ‘cause getting a Thirdling in the Void would kill them or anything! ... Well, there's none of the regular matter you know in there, so technically it can be deadly to human beings since there's no oxygen in there, but other than that, you could totally wander through it with your usual oxygen cylinder and no special combination at all. The Void doesn't contain regular matter, but it's full of magic: so it's completely different from deep space.

So really it’s just forbidden ‘cause these guys are paranoid. Seriously. Well it’s TOO LATE FOR THAT, DUMMIES!

As a side note, the avatar they create isn’t their actual body of course; and though every Higher is supposed to have a default form for it, they can alter its shape or size or appearance however they want; just as a continuity to their reality-bending powers on the Plane overall. Most avatars created remain just that— virtual avatars for the Highers. However, some dumber Highers decide that it’s funnier when the blending within their Plane is complete, so they decide to actually implant their consciousness inside these avatars every once in a while. Only “benefits” this gives is that they get a tridimensional perspective over things and still keep their “omnipotence”, so— yeah, basically pointless to most of them.

The explanation as to how exactly manifesting works is pretty simple, but I’ll leave that for another time. That’s soul-related stuff after all.

Moving on to the Planes themselves, now! Long story short, there are two types of Planes: the ones whose Creator is known within the Great Society — which make the vast majority of the multiverse; and the (currently 48) Onos.

#1: Regular Planes

These Planes can be of all different shapes or types, but they all share the same origin: they are initially created by someone from the Great Society, namely a “Higher” like they like to call themselves. They are for the vast majority tridimensional, but there’s no strict rule upon that and there can be some bidimensional or quadridimensional Planes at times; it’s mostly a question of power and convenience. Highers can look practically omnipotent to a human’s scale, but their resources actually are limited! And the Great Society also has set up a ridiculous amount of laws and regulations over how to create and treat your Plane(s), so it explains why most Planes are tridimensional and actually have so much in common when you look at their laws of physics. I mean, what’s the point of creating a universe if you can’t share it with the others, right?

And that’s the main point of these Planes. Highers can create them for various reasons, but most of them just see their creations as sorts of personal playgrounds— kinda like how you create and manage your own city in some dumb videogame, you could say. But when it really gets fun? That’s when you have your personal Plane interact with your pals’ Planes too! That’s how the Great Society created this network system between Planes— “the Union.” You could see it as some sort of real-life giant-scale MMO RPG. Not all Planes take part in the Union, but a really significant part of them does; it all depends on whether the Plane’s Creator is interested or not.

Oh, and, well— almost forgot! Of course the Plane’s actual inhabitants have NO IDEA that their lives are just a source of amusement for beings living in a higher plane of existence. Ha.

Some members of the Great Society are even debating over the Planes’ rights and questioning whether the tiny creatures living inside are actually real and alive or if they’re just virtual toys. Surely the Onos made them even more confused than before! The debate’s been up for Timesecs and never seemed to ever reach a conclusion towards either side. For now, every Plane and its inhabitants have rights as properties. Pets, at best.

There’s an actual regulation about this, to be fair. In order not to compromise the Union’s unique experience and the “Thirdlings’” life and mental health, it is strictly forbidden for any Higher to reveal their actual nature to any of the Union’s residents— nor are they allowed to show off their full power to any of them. If any “Thirdling” gets a little too smart and happens to question a Higher about their local omnipotence within the realms of their Plane, the Higher is expected to avoid the question or resort to excuses— when they are unwilling to use their powers to just brainwash the little guy into forgetting all their worries, that is (needless to say, that’s the option most of them choose). The most common excuse that runs between Highers is that explaining the concept or revealing a certain truth to them would “make [their] head explode.” This became practically memetic by now.

Anyway, back on topic: these Planes have a unique Creator, who can create one or more Planes for their own reasons. They can be of all shapes and made of various numbers of dimensions, though most of them are tridimensional. Magic is the prominent element of their composition, while what you know as regular matter is there just for helping keep things together and making structures a little stabler, although many of the Union's Planes hardly contain any at all. After all, you could say that Highers are sorta "allergic" to regular matter, heh. But I'm coming to that part.

#2: The Onos

As stated before, the main particularities of the Onos is that their potential Creator is completely unknown (to the extent that even some of the most ignorant Highers question the mere existence of these Planes, judging their concept vastly surreal), and that contrary to all the Planes created by Highers— these ones are practically anti-magic, in that they are made in the vast majority of what you'd call "regular matter." Said regular matter has a strange habit of basically disintegrating magic by turning its particles into radiating energy (aka, light), so it takes pretty peculiar circumstances to have an Ono adapt so that it will gradually allow magic to merely exist within its boundaries.

Also, each time something from the Outside tampers with an Ono— it splits. If a multiversal traveler tries to reach an Ono without the proper material (namely a quantum stabilizer, more on that later), the Ono will split into two new Planes: one Ono in which the traveler reached their destination, and another one in which the traveler didn’t. It also works if the traveler comes from the Ono and then tries to leave its boundaries.

Back with the Ono’s potential “Creator”— one thing is for sure, if that guy exists, then he’s the most powerful being to exist in the entire multiverse, because the creatures living inside have among the most powerful souls that have ever been seen. The Highers' still have much more powerful ones of course, but that's just because they're dodecadimensional!

Really, Onos are what you could call a subject of fear for the Great Society, because that's something that's developing on their territory, and that's about the only thing they have hardly any control over— what with these Planes' composition that makes it impossible for Highers to manifest in them. Some Highers have been able to tamper a little with these from the outside (aka force a split), but that’s about it. They’re completely unable to alter an Ono directly. All they can do is watch what happens inside, or at best communicate to some extent with the people inside via electronical messages or radio transmissions.

So yeah. Onos are the homeplane for the human species— a species that was unknown to the Highers until then, and a species they didn’t care much about until they found out how powerful their souls are compared to the other Thirdlings’. To give you an idea, even the most powerful Soul the Great Society’s Supreme Leader could potentially create within a Plane given his Level? It’d be more than 1,500 times weaker than an original human Soul.

By now, the most common theory among Highers is that Ono-Gen just somehow created itself through some sort of big fluke. With a literal “Big Bang”, like you also call it.

But that’s probably because they’re way too proud to even imagine the possibility of beings existing in an even higher plane of existence than their own, heh. Just one being like that is way enough for them to turn their minds upside down trying to stop it! HA! Dummies.

0 notes