#child forensic interview structure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Comprehensive Guide to Become a Certified Child Forensic Interviewer

Child forensic interviewing is a specialized field aimed at eliciting accurate and reliable information from children who may have been victims or witnesses of crime. Acquiring forensic interviewer certification involves learning specific skills, knowledge, and training to conduct these sensitive interviews effectively. In this guide, we will delve into the intricacies of child forensic interviewing and provide a roadmap for those aspiring to become certified in this vital profession.

What is a Child Forensic Interview?

Child forensic interviewing is a structured process designed to obtain information from children about their experiences in a non-leading, developmentally appropriate, and legally defensible manner. These interviews are conducted by trained forensic child interview specialists who possess expertise in child development, communication techniques, and forensic procedures. The primary goal is to gather accurate information while minimizing the risk of suggestibility or provocation.

Can a Forensic Interviewer Tell If a Child is Lying?

Determining the truthfulness of a child's statement during a forensic interview is a complex task. While there are no foolproof methods to ascertain absolute truthfulness, certified forensic interviewers rely on a combination of verbal and non-verbal cues, along with adherence to established protocols, to assess the credibility of a child's disclosure. It is essential to approach each interview with objectivity, empathy, and an understanding of factors that may influence a child's behavior and responses.

Is Child Forensic Interview Training Available Online?

Yes, there are reputable organizations and institutions providing child forensic interview training online. These programs offer comprehensive coursework covering topics such as child development, trauma-informed interviewing techniques, legal considerations, and ethical standards. It is crucial to select training programs accredited by recognized professional organizations, such as the National Association Of Certified Child Forensic Interviewers (NACCFI), and to supplement online learning with hands-on practice and mentorship opportunities.

What Exam Shall I Take to Become a Certified Child Forensic Interviewer?

The certification process for Child Forensic Interviewers varies depending on the accrediting body and jurisdiction. However, one recognized ethically certified forensic interviewer exam/test is offered by the National Association of Certified Child Forensic Interviewers (NACCFI). Candidates must complete a specified number of training hours, demonstrate proficiency in forensic interviewing skills, and pass a rigorous examination assessing their knowledge and competence to become a certified child forensic interviewer.

Learn More About Child Forensic Interview Structure

A thorough understanding of the structure and principles underlying child forensic interviews is essential for aspiring certified forensic interviewers. Familiarize yourself with best practices for rapport-building, question formulation, memory retrieval techniques, and cultural considerations. Stay updated on advancements in child forensic interview structure or model and legal standards to ensure adherence to the highest professional credibility.

#Child Forensic Interview#certified forensic interviewers#child forensic interview training online#NACCFI#certified forensic interviewer exam/test#child forensic interview structure

0 notes

Text

Understanding Forensic Psych Evaluation: Purpose, Process, and Importance

A forensic psych evaluation plays a crucial role in legal proceedings, helping courts make informed decisions about individuals involved in criminal or civil cases. This type of psychological assessment evaluates mental health, cognitive abilities, and behavioral patterns to determine an individual’s competency, criminal responsibility, or suitability for specific legal matters.

This article explores the purpose, process, and significance of a forensic psych evaluation in legal settings.

What Is a Forensic Psych Evaluation?

A forensic psych evaluation is a structured assessment conducted by a qualified mental health professional, often a forensic psychologist. It is used in both criminal and civil cases to assess an individual's mental state, competency, and psychological profile.

Unlike clinical evaluations, which focus on diagnosis and treatment, forensic evaluations are specifically designed to answer legal questions. They may determine whether an individual is fit to stand trial, whether they were mentally competent during an offense, or whether they pose a risk to themselves or others.

Key Purposes of a Forensic Psych Evaluation

A forensic psych evaluation serves several legal and psychological purposes:

Competency to Stand Trial – Determines if an individual understands court proceedings and can actively participate in their defense.

Criminal Responsibility (Insanity Defense) – Assesses whether a person was mentally sound at the time of an alleged crime.

Risk Assessment – Evaluates the likelihood of reoffending or posing a danger to society.

Child Custody and Parental Fitness – Determines a parent’s mental and emotional capacity to care for a child.

Personal Injury and Disability Claims – Assesses psychological harm resulting from trauma or accidents.

Employment and Fitness for Duty – Determines if an individual is mentally fit for high-stress occupations, such as law enforcement or military service.

The Process of a Forensic Psych Evaluation

The evaluation process involves multiple steps to ensure a thorough and objective assessment:

1. Referral and Case Review

The process begins when a legal authority requests the evaluation. The forensic psychologist reviews case files, medical records, and any other relevant documents to understand the background of the case.

2. Clinical Interviews

A structured or semi-structured interview is conducted with the individual being evaluated. The psychologist may also interview family members, law enforcement officers, or other relevant parties.

3. Psychological Testing

Standardized psychological tests, such as personality assessments, cognitive evaluations, and malingering tests, help determine mental state and behavioral tendencies.

4. Collateral Information Gathering

Additional information is collected from records, such as school or employment history, criminal records, and past medical reports.

5. Analysis and Interpretation

The forensic psychologist analyzes the collected data to form an expert opinion regarding the individual's psychological state in relation to the legal questions posed.

6. Report Writing and Court Testimony

A detailed report is prepared outlining findings, conclusions, and expert recommendations. In many cases, the psychologist may be required to testify in court as an expert witness.

Ethical Considerations in Forensic Psych Evaluations

Forensic psychologists must adhere to ethical guidelines to maintain the integrity of the evaluation:

Objectivity and Impartiality – Avoiding personal biases and ensuring neutral reporting.

Confidentiality and Legal Obligations – Understanding that forensic evaluations are not entirely confidential since they are used in court proceedings.

Informed Consent – Ensuring that individuals undergoing evaluation understand the purpose and limitations of the assessment.

Conclusion

A forensic psych evaluation is an essential tool in legal cases, providing objective psychological insights that aid in decision-making. Whether determining competency to stand trial, assessing criminal responsibility, or evaluating parental fitness, these assessments play a vital role in ensuring justice and fair legal outcomes. The structured, ethical approach of forensic psychologists helps courts make well-informed decisions that balance legal and mental health considerations.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of the mind and behaviour. Its subjects consist of both the behaviours of humans and nonhumans, including conscious and unconscious phenomena, along with mental processes like thoughts, feelings, and motives.

So why do you think, behave and feel the way you do? How does this affect your memory, the way in which you communicate and your ability to complete tasks?

Psychology attempts to get to the bottom and answer questions like these.

Psychology is everywhere, it is constantly artwork all around you in your everyday life.

TYPES OF PSYCHOLOGY

Clinical Psychology

Clinical Psychology refers to the study and evaluation of a wide range of both mental and physical health conditions. This includes addiction, anxiety, depression, learning difficulties and relationship issues in which they use a number of different methods like psychometric tests, interviews and direct observation.

Coaching Psychology

Coaching psychology is the scientific study of behaviour, emotion and cognition, it is used as a way to deepen our understanding of individuals as well as groups performance, achievement and wellbeing in order to enhance practice within coaching.

Counselling Psychology

Counselling psychology incorporates a variety of life issues, this may include bereavement, domestic violence, sexual abuse, traumas, and relationship issues. Working with a persons unique subjective psychological experience to therefore empower their recovery and reduce distress.

Educational and Child Psychology

Educational and Child Psychology focuses on how children and the youth experience life, relevant to their school life along with home environment and how these different factors within these environments interact with each other.

Forensic Psychology

Forensic Psychology looks at people who have throughput there life been effected by court of other legal systems like family court for example. It also involves exploring and understanding offending behaviour and potential opportunities for recovery and rehabilitation regarding these sercumstances.

Health Psychology

Health Psychology relates to studying the psychological processes of underlying health problems, illness and health care. It applies these findings towards the promotion and maintenance of health, the analysis and improvement of the health care system, the prevention of illness and disability as well as the deepening of outcomes for those who are ill or disabled.

Neuropsychology

Neuropsychology researches into the structural function or relationships within the living brain, how it develops throughout our life and the potential outcomes of rehabilitation after a brain injury or other neurological disease.

Occupational Psychology

Occupational Psychology incorporates the performance of people at work and how these people along with smaller groups and larger organisations function and behave in their work environment. The aim of this is to improve workplace efficiency and also improve job satisfaction of workers.

Sport & Exercise Psychology

Sport and Exercise Psychology is mainly related to the application of psychology to sport / exercise to increase participation and motivation levels for the general public. It also studies the factors of which influence, performance and behaviour of athletes during training and competitions.

Psychology is a fairly new kind of science, where most advances have occurred in the past 150 years. Although, its origins can be traced beck to Ancient Greece.

Philosophers used to discuss a number of topics which are now studied by modern psychologists, this included memory, free will vs. determinism, nature vs. nurture, attraction, etc.

Psychology in general covers many many areas and is a vast and multifaceted field. As time has gone on and our understanding of the human mind has developed, many specialised branches of psychology have emerged like clinical psychology, social psychology, and developmental psychology, which are all more recent fields.

THE BEGINNINGS OF PSYCHOLOGY

In the initial days of psychology, there were two primary theoretical perspectives looking at how the brain functions, these are structuralism and functionalism.

Structuralism

Structuralism was pioneered by Willhelm Wundt from 1832 through to 1920. It focuses on breaking down mental processes into more basic elements.

It relied on trained introspection, a research methods in which subjects relayed what was taking place in there minds when performing specific tasks.

However, upon further research introspection proved to be an unreliable method due to the fact there was too much individual variation in the experiences.

Disregarding the failure of introspection Willhelm Wundt is still a highly important figure in the history of psychology due to the fact he opened the first ever laboratory solely dedicated to psychology in 1879. This was considered to be the beginning of modern experimental psychology.

Functionalism

From 1842 through to 1910 American psychologist William James created an approach in psychology which was named functionalism, that disagreed with the tellings of structuralism.

William James argued that the mind is forever changing and there is no point at looking for the structure of conscious experience. But instead he stated that the focus should be put on how and why an organism does something.

He suggested that psychologist should instead look for the subliminal causes of behaviour along with the mental processes involved. This new emphasis on the consequences and causes of behaviour has ultimately influenced contemporary psychology as a whole.

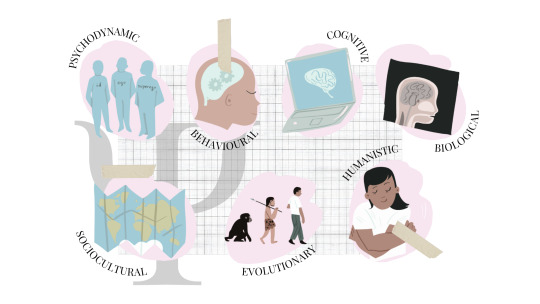

THE PERSPECTIVES OF PSYCHOLOGY

Structuralism and functionalism have over the years been replaced by a number of dominant and influential approaches to psychology. Each aligned by a shared set of assumption for why we are the way we are.

Behavioural Perspective

This was created around the 1910s to the 1920s following John Broads Watson's work. This perspective brings light to observable behaviours and the environments role in this

Psychodynamic Perspective

Developed in the early 1900 psychodynamic perspective , emphasised the unconscious mind along with early life experiences.

Human Perspective

This emerged in the 1950s /60s as a carry on from behaviourism and psychoanalysis. It considers the basic human needs of a person along with how important these needs are to the overall happiness of a person.

Cognitive Perspective

Cognitive Perspective became popular in the 1950s and 1960s. It focuses how the internal thought and feelings or a person effects their behaviour.

Biological Perspective

In the later part of the 20th century biological perspective became dominant, it states that all thought feelings and behaviours all have a biological cause.

Evolutionary Perspective

Charles Darwins evolutionary theory dates back to the 19th century, but its involvement in psychology only began in the 1980s to 1990s. It involves the study of behaviour, thought, and feeling as viewed through the lens of evolutionary biology.

Sociocultural Perspective

Sociocultural perspective became popular in the later half of of the 20th century. It focuses on the influence of social interactions, cultural practices and environmental contexts within individual behaviour and cognitive processes.

Ecological Systems Perspective

Introduced in the 1970s, this perspective looks at examining the multi-layered influences of a persons development.

THE GOALS OF PSYCHOLOGY

There are 4 prominent goals of psychology, these are to describe, explain, predict and change the behavior and mental processes of others.

To Describe

Describing a cognition or a behaviour, is the first step of psychology. This allows for researchers to develop general laws of human behaviour.

To Explain

After researchers have described the foundations of behavioural laws, the next aspect is to explain both how and why this action takes place. With this psychologists will provide theories in which explain these behaviours.

To Predict

Psychology amongst other things aim to predict future behaviour of a person or group by finding empirical research. If a prediction is not confirmed or proven, then the explanation it is reliant on may need to be reassessed.

To Change

After psychology has described, explained and made predictions about behaviour it now allows for the changing or controlling of a behaviour to be attempted.

McLeod, S. (2024). What Is Psychology?. [Online]. Simply Psychology. Last Updated: 3 September 2024. Available at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/whatispsychology.html [Accessed 5 February 2025].

Kindersley, D. (2011). The Psychology Book. Great Britain: Darling Kindersley Limited. pp.0-339.

https://www.bps.org.uk/what-psychology#:~:text=Psychology%20%2D%20the%20study%20of%20the,to%20address%20real%2Dworld%20issues.

The British Psychological Society. (2018). What is psychology?. [Online]. The British Psychological Society. Available at: https://www.bps.org.uk/what-psychology#:~:text=Psychology%20%2D%20the%20study%20of%20the,to%20addres [Accessed 5 February 2025].

0 notes

Text

different types of therapies

accelerated experimental dynamic psychotherapy

acceptance and commitment therapy

Adlerian therapy

animal-assisted therapy

applied behavior analysis

art therapy

attachment-based therapy

bibliotherapy

biofeedback

brain stimulation therapy

Christian Counseling

coaching

cognitive behavioral therapy

cognitive processing therapy

cognitive stimulation therapy

compassion-focused therapy

culturally sensitive therapy

dance therapy

dialectical behavior therapy

eclectic therapy

emotionally focused therapy

equine-assisted therapy

existential therapy

experimental therapy

exposure and response prevention

expressive arts therapy

eye movement desensitzation therapy

family systems therapy

feminist therapy

forensic therapy

gestalt therapy

human givens therapy

hymanistic therapy

hypnotherapy

imago relationship therapy

integrative therapy

internal family systems therapy

interpersonal psychotherapy

jungian therapy

marriage and family therapy

mentalization-based therapy

motivational interviewing

multicultural therapy

music therapy

narrative therapy

neuro-linguistic programming therapy

neurofeedback

parent-child interaction therapy

person-centered therapy

play therapy

positive psychology

prolonged exposure therapy

psychoanalytic therapy

psychodynamic therapyy

psychological testing and evaluation

rational emotive behavior therapy

reality therapy

relational therapy

sandplay therapy

schema therapy

social recovery therapy

solution-focused brief therapy

somatic therapy

strength-based therapy

structural family therapy

the Gottman method

therapeutic intervention

transpersonal therapy

trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy

#therapy#mental health#generalized anxiety disorder#anxiety disorder#mental health support#agoraphobia#coping#depression help#mental heath support#mentalheathawareness#mental health struggles#burnout#stress#perfectionism

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!!! Lifting from that first meeting starters list- “I’ve seen some weird shit, but you’re something else" with Ferid (lmao)? No worries if the prompt is too uninspiring but I would love to see you write this!!! Thank you!!!

It was actually very inspiring and I’m so happy that I can write something about my beloved problematic fav and for you! Thank you so much for sending this, I hope you’ll enjoy it 💕It took me like 5434578 years and now I think it could make a hella good, multiple chapter fanfiction.

→ Word count: 2,994

London, 16 November 1888

Heavy fog was lingering between narrow buildings creating an overwhelming atmosphere of coldness and dread. Empty, dark windows seemed to stare at the passers by who were foolish enough to wander through this part of the city in such a late hour, where nothing but darkness remained, delicately diffused by the light of the moon, now hanging high on the sky in a partly bitten shape of the sickle. It was almost eleven o’clock at night, no wonder then that the only sound in the area was the creaking of crows, the sound of water flowing down the drain, the whistling wind and your footsteps on the pavement, still wet from the recent downpour.

You were mentally scolding yourself for not declining the last cup of tea from Mrs. Jones and not coming back home earlier, when the weather was more pleasant and the area less dangerous. Still, you didn’t want to give any bad impression, both for her and her son, whom you have finally managed to have an interview with after many weeks of trying and impatiently waiting for his letter. Henry Jones was, after all, one of the best forensic doctors and one of the few who was willing to answer your questions, right now, however, you were staring to doubt whether staying in his mansion for so long was a good idea. You didn’t have any other alternative for a way back home, except for walking on your feet on this eerie night. You couldn’t lie that, despite the unfortunate circumstances, it was a truly wonderful night, the ones where you could almost hear the unreal whispering in the shadows.

You heard a carriage driving in the distance and you decided to turn left, preferring to keep the track on the wider, better illuminated streets instead of those narrow ones, where the danger seemed to be ready for an attack behind every corner. You didn’t want to die, especially not now, when you had your notebook with the written interview you were working so hard on, it would be truly unfair for it all to go to waste simply because of not being careful enough. However, the cold shiver was still running down your spine, reminding you about your poor choices and the possibility of negative results it could bring to your life soon. Eventually, you decided to focus on the road and the surroundings, relying on your senses and instincts which should allow you to notice the presence of someone else before any tragedy happened. The crows were circling your form on the sky above like an evil omen and with every step further, it was harder to control the trembling of your arms.

Walking to the other side of the street to avoid some drunkard laying there, you held the notebook more firmly and speed up a little, now realizing that it was not so far away from your home. All you had to do, was to cross the next road and you would see the tiny garden in front of your house, the mere think of climbing to the bed bringing the smile to your lips. Just when you were about to reach the crossroad, there was something unusual which you noticed with the corner of your eye while passing nearby the narrow street hidden in the shadows between two tenement houses. The wave of shock shaked through your body and forced you to stop in the middle of the step, your imagination now creating the very dreadful images of what could it be in real, while after slowly turning your head to the side, you realized that it was no joke your mind would be playing on you.

You really did saw a wave of a perfectly white coat.

At first, you thought that it was a pair of lovers in an adoring embrace in such a grotesque scenery of the dirty street, where the outfit of a man who’s back was facing you was the purest object your gaze could find. The longer you looked, however, the more your eyes saw and it didn’t took you long to realize that the head resting on the shoulder of the noble was unnaturaly pale, gray even, when there was no more life shining in their dead eyes. The other one, dressed as the nobility, was holding them tightly against the wall, his face hidden in the crook of their neck; coat swinging with the soft whispers of the wind and long, almost silver hair tied up with the black ribbon at his nape.

The aristocrat seemed to notice your presence despite staying back to you and with a swift movement straightened his back and slowly turned to you, his paperlike skin painted with the crimson blood smeared over his lips and sharp fangs. He let go of his victim, allowing them to fall on the pavement with a loud thud, like an used toy which was no longer needed and despite the horror and ridiculousness of this whole situation, you couldn’t stop staring at his inhuman, red eyes where thin, vertical pupils dilated a little at your sight.

The vampire, the man in front of you was undoubtedly a vampire and it was the only reasonable thought that your shocked mind could comprehend in that moment. Still, staying in the middle of the street in front of this bloodthirsty monster in the middle of the night didn’t seem like the safest idea in the slighest, but your legs were too heavy to carry your body somewhere else. You could only stare and admire his features, the ones which would easily lure both men and women, seducing them with the fleeting promise of the sweet kiss, only to leave them lifeless at his feet.

“Well then,” he mused, his voice low and calm, amused even. “I wasn’t expecting an audience.”

Mesmerized, you observed as he took a handkerchief out of the pocket and wiped the blood off his lips. Despite your mind screaming at you that you should ran as fast as you can, you still weren’t able to move and were simply looking at his nonchalant movements as if he didn’t just kill a human in front of your bare eyes by drinking the blood out of his body.

“Not much of a talker, are you?” he chuckled and peeked at the right as if he was hearing something your mortal senses couldn’t catch in the night air. “Nevertheless, it was nice seeing you. I hope you enjoyed the show, good luck explaining it to the others!”

With a laugh on the lips, the vampire turned around and wandered off leaving you absolutely speechless. Cold wind blew in your face, reminding you that indeed, you were still alive, cheeks burning from the emotions and feeling as if you had just witnessed a truly bizarre dream.

London, 17 November 1888

The tea in front of you was getting colder with every passing minute as you couldn’t bring yourself to take a sip of it, too lost in your own thoughts. Memories of the previous evening were running through your head with the speed of light, every single one of them giving you more questions left without answers, bothering you and your common sense.

Did it all truly happened? Did you really witness that? Was that man—the vampire—real or just a part of your vivid imagination? Even if he was, how was it possible, after all? Those creatures were supposed to exist only in fairytales you heard as a child, not in your everyday life. What about all of the others then? Werewolves? Mermaids? Were they here, too, living among mortals without their knowledge? Or maybe you were just insane?

The whole situation was driving you mad, just as the unbearable suspense.

Finally, you took a sip of now cool tea and reached for the newspaper, looking at the obituaries, looking for any signs of the man that you saw dying yesterday. Unfortunately, nothing could be found and with a heavy feeling in the stomach, you wondered whether his body was found at all. Or maybe they were just a peasant, not worth having any notice in the local newspaper?

“Damn it,” you muttered under breath and stood up from the table, heading to your humble office, determinated to finally finish your article.

If you would only focus on your job, you would surely start forgetting about it. It seemed like much safer option for you, too, especially since digging into such a delicate subject could end up badly for you, possibly even worse than for this unfortunate person who was the vampire’s victim.

London, 29 November 1888

You could swear that you saw him with the corner of your eye while wandering through the street with the basket full of groceries. He was there, facing you and smiling as if your mere presence was amusing him, still, it didn’t take him longer than a blink to disappear into the crowd, leaving nothing but a cold chill down your spine.

It couldn’t be a dream, he wasn’t part of your imagination although he, indeed, appeared in your dreams from time to time, mostly saying something inconherent but always dressed all in white—such a contrast to the darkness he was surrounding himself with. In your dreams, the vampire seemed so real you could almost touch him, feel the soft structure of his pearly white skin under your fingers and yet, no matter how many times you tried to do it, he still managed to fade away in the last second. Your mind was playing terrible tricks with you, that was for sure, but the memory of that night seemed to be engraved in your head, haunting you for the rest of your life if you only didn’t find the truth.

The unspoken words floating through your mind were interrupting your work which eventually wasn’t completely unnoticed.

“Is everything alright?” The question asked so suddenly made you jump slightly, coming back to reality as you looked at your friend and remembered that you were meeting with him to give him your latest article to publish in the newspaper.

Ungrateful job, publishing your works with a different surname, but you enjoyed seeing them printed on the paper, the pride not leaving you since you first managed to hold it with your hands.

“Yes, it’s alright,” you forced a smile. “I’m just tired, this one took a lot more energy than I thought.”

“I’m sure it will be great,” he smiled at you. “The letters we are receiving are mostly praising your work.”

“Well, that’s a compliment then.”

“Are you sure you’re alright? If you need to talk, you know where to find me.”

For the mere second you wondered how would he react of you told him about what you saw—about the vampire on the hunt—but immediately decided to not speak about it. Not only he wouldn’t believe you but he could also grow concern about your mental health. You could almost hear the words the vampire said just before leaving you be, letting you live, and they echoed in your mind for a long time after.

Good luck explaining it to the others.

“I’m fine. Thank you for the concern.”

London, 5 December 1888

The letter you received was unexpected. Obviously, you were aware of the engagement of your cousin but you didn’t think the whole ceremony of marriage would happen so soon. Still, you were reading an invitation again and again, fingers tracing the ink letters as your sight loomed over them, words repeated in your head.

It was supposed to be a wonderful evening, full of joy, lights and flowers and you couldn’t be more happy for her. Such a splendid way to start the new year, with the love of the life by the side, ready to pace through the future together.

Right now, however, you had to focus on finishing the new article, the one you still weren’t sure whether you wanted to publish or not. It seemed like a risky idea but you couldn’t help yourself, thinking about how could it be the only opportunity to keep the demons away.

It wasn’t going to get signed with your surname, after all.

Warwick, 20 December 1888

The manour your cousin was going to start living in was gorgeous, decorated mostly in bottle green and dark blue—her now husband’s favourite colours. You could endlessly walk through the halls, admiring detailed paintings, marble sculptures and other decorations which were giving the whole interior a truly exquisite taste. The library was just as impressive as the rest of the house, containg so many titles that even the best London’s bookstores could only envy such a collection. The air was soaked with the smell of warm wax, sweet perfumes, cold, winter air and the delicious aroma coming from the kitchen floor below, all of that spiced with the melody played downstairs by an orchestra invited to the ball.

It was supposed to be a magnificent evening and it truly was—first, the wedding and now the party.

You walked into the parlour and realized that there was only few people there, sitting on the comfortable couch and armchairs next to the fireplace and chatting, prehaps taking a breath before coming down to the ball. It was quiet there, indeed, a perfect place to relax a little and have a small conversation with a glass of champagne in the hand.

Encouraged, you headed to the nearest free place and sat in an armchair, immediately feeling as if its soft structure was going to swallow you whole. Letting out a long exhale, you looked at the impressive painting of your cousin and her husband hanging above the fireplace, smiling slightly to yourself at this utopic image. You were genuinely wishing them the best and since he seemed to be a good man, it shouldn’t be too hard to fulfill.

“Good evening.”

Hearing a voice coming from the couch next to you, you turned to look in the face of whoever desired to interrupt your thoughts, just to freeze in place as your eyes met the bloody red ones, vertical pupils observing you with a predatory precision.

“Oh, don’t you remember me, little lamb?” Theatrical sadness appeared on the handsome face of the vampire as he leaned down, resting his chin on the hand, only to be changed in an amused one within a mere second. “I think you do! If you didn’t you wouldn’t write such an article to the newspaper, would you?”

Your throat suddenly grew completely dry and you had to swallow to remind yourself that you were, indeed, able to speak. Plus, you were both surrounded by people, in the middle of the party, moreover, so he wouldn’t dare to hurt you now.

Or would he?

“Still not much of a talker, hm? Alright then, allow me to introduce myself first. My name is Lord Ferid Bathory.”

You nodded slightly, now matching his name with the image from your memory and dreams. Hesitantly, you answered, sharing your name with him only to receive a chuckle.

“I know your name, silly! I know that you didn’t use it under an article, also.”

“Did you read that?” you asked quietly, brows furrowing.

Of course, the main idea of the article was to draw his attention and somehow bring it back to you—just so you could stop all this nonsense and finally find peace, either in an embrace of death or having a conversation with him. Still, you wished more for the latter and you weren’t disappointed now, simply surprised that it worked.

Your friend wasn’t the happiest after reading the article you prepared, explaining to you that subjects about supernatural beings may not be greatly welcomed in the society who is building cages above the graves of their beloved ones just in case they could raise from the dead. Still, you insisted, argumenting that it was nothing but a hint, an advice on how to act in case of an attack. Wandering alone in the night was the first position on the list about how to protect yourself from the evil spirits.

“Of course I did,” he smiled and you could swear that you saw the tips of his fangs for a single moment. “It was hilarious, if you ask me, but I have to disappoint you, my little lamb, wooden stake does no harm to us.”

“It doesn’t…?”

“It doesn’t.”

“Well then…” You adjusted the position on the armchair so you would face him directly. “What does?”

He laughed genuinely happy, drawing attention of people in the parlour for a second.

“That would be too easy if I just told you.”

“Why didn’t you kill me back then?” The question escaped your lips before you could think about it twice and with the words spoken, you felt an unexistent heaviness leave your shoulders, just now noticing how it was present there since the day you saw the vampire on the street.

But Ferid simply shrugged.

“I don’t know. I wasn’t hungry anymore, as you probably noticed. I wasn’t in the mood for playing around. I simply didn’t want to.”

“Are you implying that I’m alive only because of your caprice?”

“I’m not implying.” The spark of malice appeared in his eyes. “I’m simply telling the truth.”

There was a silence between you two as the air grew heavy, yet somehow not noticed by anyone else. Once again, you felt as if you were in a dream, the dreadful and exciting one, crossing the paths of fantasy and reality when the vampire, the real vampire was sitting next to you and casually talking with you. It was completely ridiculous and absurd.

“I’ve seen some weird shit, but you’re something else,” you finally commented, making him giggle at your choice of words, taking a strand of white hair behind the ear.

“And that’s exactly why I like you, little lamb.”

#ferid bathory#ferid x reader#ferid#owari no seraph#seraph of the end#ons#ferid scenario#ferid imagine#ferid bathory scenario#ferid bathory imagine

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Adlerian Therapy, Animal-Assisted Therapy, Applied Behavior Analysis, Art Therapy, Attachment-Based Therapy, Bibliotherapy, Biofeedback, Brain Stimulation Therapy, Christian Counseling, Coaching, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Cognitive Processing Therapy, Cognitive Stimulation Therapy, Compassion-Focused Therapy, Culturally Sensitive Therapy, Dance Therapy, Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Eclectic Therapy, EMDR, Emotionally Focused Therapy, Equine-Assisted Therapy, Existential Therapy, Experiential Therapy, Exposure and Response Prevention, Expressive Arts Therapy, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy, Family Systems Therapy, Feminist Therapy, Forensic Therapy, Gestalt Therapy, Human Givens Therapy, Humanistic Therapy, Hypnotherapy, Imago Relationship Therapy, Integrative Therapy, Internal Family Systems Therapy, Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Jungian Therapy, Marriage and Family Therapy, Mentalization-Based Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, Motivational Interviewing, Multicultural Therapy, Music Therapy, Narrative Therapy, Neuro-Linguistic Programming Therapy, Neurofeedback, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), Person-Centered Therapy, Play Therapy, Positive Psychology, Prolonged Exposure Therapy, Psychoanalytic Therapy, Psychodynamic Therapy, Psychological Testing and Evaluation, Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, Reality Therapy, Relational Therapy, Sandplay Therapy, Schema Therapy, Social Recovery Therapy, Solution-Focused Brief Therapy, Somatic Therapy, Strength-Based Therapy, Structural Family Therapy, The Gottman Method, Therapeutic Intervention, Transpersonal Therapy, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy

SANITY BY COMBAT FUCK YES

0 notes

Text

Psychology and Law, Ch 5: Eyewitnesses to Crimes & Accidents, pt. 5

Children as Witnesses

Sometimes a child is the only witness to a crime, or its only victim. A number of questions arise in cases where children are witnesses. Can they remember the precise details of these incidents? Can suggestive interviewing techniques distort their reports? Do repeated interviews increase errors? Is it appropriate for children to testify in a courtroom? Society's desire to prosecute and punish offenders may require that children testify about their victimization, but defendants should not be convicted on the basis of inaccurate testimony.

To test children's eyewitness capabilities, researchers create situations that closely match real-life events. In these studies, children typically interact with an unknown adult (the "target") for some period of time in a school classroom or a doctor's office. They are later questioned about what they experienced and what the target person looked like, and they may attempt to make an identification from a lineup.

Two general findings emerge from these studies. First, children ages five and older can make reasonably reliable identifications from lineups (Pozzulo, Dempsey, Crescini & Lemieux, 2009). Second, children are generally less accurate than adults when making an identification from a lineup in which the suspect is absent. In these situations, children tend to select someone from the lineup, thereby making a false-positive error (Fitzgerald & Price, 2015). Such mistakes are troubling to the police because they thwart the ongoing investigation.

Psychologists have attempted to devise identification procedures for children that maintain identification accuracy when the suspect is in the lineup but reduce false-positive choices when the suspect is absent. Presenting lineup members in a face-off procedure that breaks the task into a series of binary decisions, rather than showing all lineup members together, decreased guessing and the incidence of false identifications from target-absent lineups (Price & Fitzgerald, 2016).

Children as Victims of Maltreatment

The most likely reason that a child becomes involved with the legal system is that he or she has been maltreated. Here the issue is not who committed the crime; rather, it is what happened to the child.

Most CSA cases rest solely on the words of the victim because these cases typically lack any physical evidence. Yet anyone who has spent time with young children knows that their descriptions of situations can sometimes mix fact and fiction. There are concerns about whether preschoolers and even older children can be trusted to provide accurate details and to disclose experiences of abuse. There are also concerns about the accuracy of memory on the part of adolescents and adults who previously experienced maltreatment.

Investigative Interviews

One feature of CSA cases is crucial to the accuracy of child witnesses: the nature of the investigative interview. Some interviewers now use a structured questioning protocol that first builds rapport between interviewer and child, and then encourages children to provide details in their own words ("Tell me everything that happened from the beginning to the end as best you can remember"). The protocol discourages the use of suggestive questions (questions that assume information not disclosed by the child or suggest the expected answer, such as "He touched you, didn't he?").

In research studies, investigative interviewers trained in this protocol have questioned preschool-aged children who were suspected victims of child abuse. Five-year-olds were able to provide forensically important information in response to open-ended questions, and even three-year-olds were able to share information when invited to elaborate on an earlier response (Hershkowitz, Lamb, Orbach, Katz & Horowitz, 2012). These findings suggest that central details (the "gist") of victimization experiences can be remembered well when they are elicited by non-suggestive questioning.

After a child has recounted an experience in his or her own words and in response to open-ended questions, investigators may ask specific questions about the event. For example, if a child said that she was touched, a follow-up question might be "Where were you touched?" Although children tend to provide more detail in response to specific questions than to open-ended questions, the use of specific questions comes at a cost: Children are less accurate in answering specific questions.

This difficulty is not restricted to very young children. After seeing a stranger in their classroom handing out candy the previous week, two groups of children (four- to five-year-olds and seven- to-eight-year-olds) were asked specific, misleading questions. Older children were just as likely as younger children to assent to these suggestions (Finnila, Mahlberga, Santtilaa, Sandnabbaa & Niemib, 2003), though suggestibility typically declines with age (e.g. Paz-Alonso & Goodman, 2016). Children are less accurate in answering specific questions than more general queries because specific questions demand precise memories of events that the child may never have encoded or may have forgotten (Poole, Brubacher & Dickinson, 2015). Additionally, the child may answer a question that she or he does not fully understand in order to appear to be cooperative (Waterman, Blades & Spencer, 2001). Finally, the more specific the question, the more likely it is that the interviewer will accidentally include information that the child has not stated. Specific questions can easily become suggestive.

A sizeable number of children experience multiple incidents of sexual abuse, and although the central features of the experiences may be constant, peripheral details may change. But before prosecutors can file multiple charges, they must provide evidence that reflects the critical details of each separate incident. In other words, the child has to "particularize" their report by providing precise details about each specific allegation. Can a child do this?

Studies that examine children's recall of repeated events typically expose them to a series of similar incidents with certain constant features and some details that vary across episodes. Although source monitoring (identifying the source of a memory) improves with age (Quas & Schaaf, 2002), children often recall information from one event as having occurred in another (Brubacher, Glisic, Roberts & Powell, 2011). In fact, exposure to recurring events is a double-edged sword: Repeated events enhance memory for aspects of the incident that are held constant but impair the ability to recall details that vary with each recurrence (Dickinson, Poole & Laimon, 2005).

If they experience multiple incidents of maltreatment, children may be subjected to repeated interviews. One line of research has shown negative effects of repeated interviews on children's memory and suggestibility. In these studies, experimenters describe to children true and false events (e.g. in one famous study, children were told that their hand had been caught in a mousetrap), imply that the children experienced all of them, and tell the children that their parents or friends said the events had occurred. After repeated questioning, approximately 1/3 to 1/2 of preschool-aged children provided additional details of the false events (e.g. Bruck, Ceci & Hembrooke, 2002). A separate line of research has documented beneficial effects of repeated interviews, however. These studies found that children exposed to repeated interviews were not prone to errors. In fact, their memory improved with repeated interviews (e.g. Waterhouse, Ridley, Bull, La Rooy & Wilcock, 2016).

What accounts for these conflicting findings? One hint comes from a study that varied the number of interviews and the nature of the questions asked (Quas et al., 2007). In this study, children played alone in a lab setting and were questioned either once or three times about what happened while they played. The questions were either biased (implying that the child played with a man) or unbiased. Children interviewed only once by the biased interviewer were most likely to claim they played with a man, and children interviewed on multiple occasions (regardless of the type of question asked) were less likely to do so. This suggests that biased interview questions can lead to false reports in a single interview (Goodman & Quas, 2008).

Stated in another way, "When and how children are interviewed is at least as important for their accuracy as is how many times they are interviewed" (Goodman & Quas, 2008, p. 386). It also suggests that forensic interviewers must question children in developmentally appropriate ways, using evidence-based techniques, and more than once if possible. Unfortunately, widespread training has had only limited impact on the quality of interviews (Lamb, 2016).

A robust finding in cognitive psychology, termed the reminiscence effect, can explain why multiple interviews might be useful. When people attempt to remember pictures or events they viewed previously, they often report (reminisce) new information on each recall attempt, suggesting that recollection may be incomplete on the first telling but unrecalled information can be produced in later interviews. Reminiscence effects are facilitated by the use of open-ended questions that allow interviewees to provide information in their own words.

Repeated interviewing is necessary when an alleged victim is too distressed to provide useful information initially, when victims fail to disclose abuse that is subsequently documented by medical examinations or suspects' confessions, or when new evidence comes to light (La Rooy, Katz, Malloy & Lamb, 2010).

Disclosure of Child Maltreatment

Children are often reluctant to disclose abusive experiences and may even deny them when asked. One study involved interviews of approximately 4,300 high school students, 45% of whom reported experiences of unwanted sexual abuse. Of these, only 65% of girls and 23% of boys had disclosed that abuse (Priebe & Svedin, 2008). Not surprisingly, disclosure of extra-familial abuse is more likely than disclosure of abuse within the family (London, Bruck, Wright & Ceci, 2008). These data suggest that large numbers of children fail to disclose maltreatment when they are young and, therefore, that reported cases of CSA are the tip of a large iceberg (Ceci, Kulkofsky, Klemfuss, Sweeney & Bruck, 2007). Disclosure is facilitated by supportive relationships and by other people's willingness to detect and report the abuse (Jones, Stalker & Franklin, 2017).

Some studies have focused on what individuals remember about being maltreated. In fact, children can remember significant details of abuse experiences and, if asked directly, can describe them quite accurately. One team of developmental psychologists contacted approximately 200 adolescents and young adults who, during the 1980s, had been involved in a study of the effects of criminal prosecutions on victims of CSA (Alexander et al., 2005). Participants had been 3-17 years old at the time of the original data collection. All of them had been sexually abused.

Upon renewing contact years later, psychologists provided a list of traumatic events (including CSA) and asked respondents to indicate which events happened to them and, among those events, which was the most traumatic. Respondents who designated CSA as their most traumatic experience were remarkably accurate in reporting details of their experiences. These data suggest that memory for emotional, even traumatic, victimization experiences can be retained quite well even decades after the events occurred.

Still, a subgroup of abuse victims either forgets the abuse or remembers it poorly. Why do some maltreated people have full access to memories of those experiences and others have none? Processes that people use to regulate their emotions- in particular, their coping strategies -may be implicated (Harris et al., 2016). People who cope with maltreatment by trying to suppress, inhibit, or ignore their thoughts about it may weaken or even eliminate memories of those experiences over time. As a result, they may have memory deficits for these traumatic events.

The Child Witness in the Courtroom

Though most child maltreatment cases end in admissions of guilt or plea bargains, tens of thousands of children, often preschoolers, must testify in abuse trials each year. In one study, although only 18% of all CSA cases involved children five years old or younger, 41% of the cases that went to trial involved children of this age (Gray, 1993). Two questions arise: What is the effect on the child of having to discuss these issues in court and how do jurors weigh the testimony of a child witness?

Talking about victimization in a public setting may increase the trauma for many children. Sexual abuse victims are especially fearful of confronting the alleged offender in criminal court (Hobbs et al., 2014). Professor Gail Goodman and her colleagues examined the short- and long-term outcomes for children who testified in CSA cases, initially interviewing a group of 218 CSA victims when their cases were referred for prosecution (Goodman et al., 1992) and reinterviewing many of them 12 years later (Quas et al., 2005).

The experience of testifying was quite traumatic for some children. They had nightmares, vomited on the day of their appearance in court, and were relieved that the defendant had not tried to kill them (Goodman et al., 1992). Twelve years later, when compared to a group of individuals with no CSA history, CSA victims who had been involved in criminal cases showed some long-term negative consequences. Most affected psychologically were those who were young when the case started, testified repeatedly, and opted not to testify when the perpetrator received a light sentence.

How do jurors perceive child witnesses? Do they tend to doubt the truthfulness of children's testimony, reasoning that children of ten make things up and leave things out? Or do they tend to believe children in this setting? In mock jury studies, child eyewitnesses are generally viewed as less credible than adult eyewitnesses (e.g. Pozzulo & Dempsey, 2009). But something quite different happens in CSA cases. Here, younger victims are viewed as more credible than adolescents because they are deemed more trustworthy and honest.

In fact, laypeople believe that the "ideal" witness in a child sexual abuse case would be an 8-year-old and the least ideal would be a 12-year-old (Nunez, Kehn & Wright, 2011). Jurors can recognize the effect of suggestive questioning; mock jurors who read a transcript of a highly suggestive forensic interview tended to discount the child's testimony (Castelli, Goodman & Ghetti, 2005).

Procedural Modifications When Children Are Witnesses

Judges allow various courtroom modifications to protect children from the potential stress of testifying. One innovation is the placement of a screen in front of the defendant so the child witness cannot see them while testifying. This arrangement was used in the trial of John Avery Coy, who was convicted of sexually assaulting two 13-year-old girls. Coy appealed his conviction on the grounds that the screen deprived him of the opportunity to confront the girls face-to-face, a reference to the confrontation clause of the Sixth Amendment that guarantees defendants the right to confront their accusers.

The right to confrontation is based on the assumption that the witness will find it more difficult to lie in the presence of the defendant. In a 1988 decision, the Supreme Court agreed with Coy, saying that his right to confront his accusers face-to-face was not outweighed "by the necessity of protecting the victims of sexual abuse" (Coy v. Iowa, 1988).

But just two years later, in the case of Maryland v. Craig (1990), the Court upheld a law permitting a child to give testimony in a different part of the courthouse and have the testimony transmitted to the courtroom via close-circuit TV (CCTV). The law applied to cases where the child was likely to suffer significant emotional distress by being in the presence of the defendant. Craig thus modified the rule of the Coy case.

Proponents of CCTV claim that in addition to reducing the trauma experienced by a child, this technology will also provide more complete and accurate reports. Opponents claim that the use of CCTV violates the defendant's right to face-to-face confrontation of witnesses. Several studies have assessed the veracity of children who testify in and out of courtrooms and whether observers perceive differences in their credibility. A common finding is that children give more detailed statements when allowed to testify on CCTV (Goodman et al., 1998). Children also feel less nervous when allowed to testify outside of the courtroom (Landstrom & Granhag, 2010).

On this basis, one might argue for its use in every case in which a child feels anxious about testifying. But things aren't quite so simple. Children who testify via CCTV or in pre-recorded videos are viewed less positively than children who testify in open court (Antrobus, McKimmie & Newcombe, 2016). It seems that jurors want to see children in person in order to assess the truthfulness of their reports. Clearly, the impact of CCTV on jurors' decisions in CSA cases is complex. Perhaps it should be reserved for cases in which the prospect of testifying is so terrifying to children that they would otherwise become inept witnesses, or would not testify at all.

Judges make other accommodations when children must testify. In cases involving CSA, physical abuse, or adult domestic violence, a support person (typically a parent, guardian, or victim assistant, is almost always present with the child to decrease stress and ideally to increase accuracy and completeness. The effect may not be what the victim intended, however, as mock jurors deem child victims less accurate and trustworthy when a support person is present (McAuliff, Lapin & Michel, 2015). A growing and controversial trend is to allow children to nuzzle with trained therapy dogs during testimony (Galberson, 2011).

Finally, we should note that although testifying has the potential to inflict further trauma on the child, it can be a therapeutic experience for some children (Quas & Goodman, 2012). It can engender a sense of control over events, and if the defendant is convicted, provide some satisfaction to the child.

#psychology and law#my notes#study blog#tw: child abuse#cw: child abuse#tw: kidnapping#cw: kidnapping#tw: violent crime#cw: violent crime#tw: CSA#cw: CSA

0 notes

Text

poison ivy & stinging nettles 15

On Ao3

Pairing: Sherlock/OFC

Rated: M

Warnings: eventual violence, torture, swears, adult themes (no explicit smut)

Chapter 14 - Chapter 16

Chapter 15- Ophelia

~~~

I missed normal. At least, normal for Baker Street. Solving crimes, going to work, and not having to worry about being shot or murdered.

It's nice, and with Amelia around, it keeps things at least a little interesting. Sherlock is on better behavior, though that didn't stop him from shooting a hole in the kitchen and earning an earful from both Mrs. Hudson and Mia the other night.

I've been doing better. The wound is pretty much healed up, and I've been able to accompany Sherlock to crime scenes again- much to Amelia's relief.

Apparently, she'd been getting sick at the sight of the bodies. Not the best habit to have when working alongside a murder consultant.

~~~

I will burn the heart out of you.

Sherlock couldn’t shake the words out of his head, his thoughts lost deep in his mind palace.

It was incredibly inconvenient, given that he was presently standing over the body of a local priest and couldn’t recall the name of the parish the man served.

“Cathedral of Our Lady the Blessed?” John voiced, peering up from his mobile.

That’s right. He knew that.

The mental image of the large church sprang into his mind.

“Right,” Sherlock stood up, straightening his jacket. “We should interview the sisters.”

“We’ll get the body to Molly,” Lestrade promised, the remainder of the forensic detectives wrapping up the small scene.

There hadn’t been much to observe. The body hadn’t had any marks of trauma or bruising. No bullet or stab wounds, no blood. No signs of poisoning. If Sherlock was less thorough, he would have chalked the whole thing up to a random heart attack.

But it was the surroundings that made the death that much more suspicious.

The priest had been found on the stage of an empty gentleman’s club. The building had been set for demolition, and during a last check of the property, a construction worker stumbled across him and called it in.

“Probably some rival showing off the priests lack moral fiber…” Sherlock mumbled under his breath.

“What?” John flagged down a taxi.

“I bet it’s someone at the parish who thought little of the priest,” Sherlock cleared his throat.

“A bit obvious then, don’t you think?” John chuckled, giving the address to the driver. “Leaving him in an old strip club?”

“Certainly not the most clever,” Sherlock agreed, sliding in next to him.

…burn the heart…

“We’re here,” John nudged Sherlock’s arm.

Sherlock blinked out the window, disoriented by the sudden arrival. The parish was at least a thirty-minute taxi ride away from the scene of the crime. He quickly paid the driver and followed John to the entrance of the large building.

It was ornate, old, and the grounds were incredibly well kept, given the age of the property.

“Hello,” a nun greeted with a smile, bowing her head to the pair. “Inspector Lestrade said you would be coming.”

“Thank you, Sister…?” John replied politely.

“Angeline,” she smiled again. So many smiles. It was irritating. “I’m relieved you two were able to make it to us so quickly.”

“It’s a shame about Father Matthews,” John hummed. Sherlock could feel the doctor watching him out of the corner of his eye while the detective poked around the gardens.

“He was a good man,” Angeline sighed. “A true child of Christ in all his work.”

“Did he have anyone who would have wanted him dead?” Sherlock questioned bluntly, scanning the Queen Anne’s lace over.

“Sherlock,” John warned. “I apologize Sister…”

“No, no,” Angeline waved off John’s concern, looking to Sherlock. “He came to us with a troubled past. Addiction, adulterous behaviors… he was looking for redemption and we provided it. He’s served our parish for a decade now.”

“And someone must have disagreed with bringing in such an unworthy man,” Sherlock surmised, folding his arms behind his back.

“Most did,” she confessed in a low voice. “Though another brother, Father Colin, was especially vocal about it.”

Sherlock nodded, continuing their way around the parish while Angeline pointed out particular areas of interest, eventually guiding them to the late Father’s personal quarters.

“Have a look around,” she unlocked the door, standing aside while the men began digging through the room.

Nothing of too much interest. Some dried flowers, some notebooks, bibles…

He took a few pictures for good measure, though nothing seemed to pique his interest.

…heart out of you.

They were back in the garden. John was saying something to Angeline and making her giggle while Sherlock was knelt down next to… parsnips?

The plot was partially dug up, some flowers and carrots discarded on the soil, a spade stuck into the dirt.

He took a picture of a flower he vaguely recognized as Queen Anne’s lace and sent it to Amelia to double-check. It was almost identical in structure, with a large bundle of small white flowers at the end of each stem.

“Sherlock?” John stepped over, looking concerned. “Are you okay?”

Sherlock tilted the plant closer to his face, studying each tiny bulb.

“This isn’t Queen Anne’s Lace,” he stated decidedly. As if on cue, his phone chirped to life with a message from their resident florist.

Hemlock. Don’t touch it. Don’t breathe it.

Sherlock pulled away, quickly wiping his hands on his pants.

“John, we’re going to need to make a stop,” he murmured, handing John his phone.

John skimmed over the message, eyes widening.

“Yes, right,” he cleared his throat. “Thank you. We’ll be back.”

~~~

“It’s an easy mistake,” Amelia poured Sherlock a fresh cup of tea. His head was pounding, his hands still burned from the Hemlock's stem. “They’re eerily similar. Not to mention, the ends look a lot like common vegetables. Accidental exposure happens more often than you’d think, to some of the most practiced professionals.”

“Have you ever mistaken it?” he grumbled, pulling his mug to his face, his hand shaking slightly.

“I- well, no,” she frowned apologetically. “I did accidentally poison a roommate once. Unintentionally. He’d been going through some of my samples and came across some dried hemlock. Thought it was marijuana.”

“How on earth?” John stared up at her in disbelief.

“He wasn’t very bright,” she hummed in thought. “Ended up dropping out shortly after.”

“That’s incredibly reassuring, Amelia,” Sherlock muttered.

“Maybe next time, you text me the picture before you start messing with it?” she tutted under her breath. He could feel her eyes linger on him. Worry. Concern. Masked by a snarky comment.

“I think we now know how the priest died,” John shrugged, sitting in his chair. “Poisoning.”

“Is Molly a full toxicology report?” Amelia perked up, chatting with John about the potential postmortem effects of a Hemlock poisoning. “An intentional poisoning wouldn’t necessarily have any outward signs. Maybe vomiting? But if he didn’t touch it, there wouldn’t be any irritation on the skin.”

She gestured to Sherlock’s hands. He responded with a scowl, earning a snicker from his friend.

I will burn the heart out of you.

~~~

“Now I know the poison wasn’t strong enough to hallucinate me again,” Amelia’s voice teased through Sherlock’s subconscious. His mind was dark. The only sign of life the familiar New Yorker accent. “Are you dreaming about me?”

His eyes opened to a brightly lit field of wildflowers. The sun was shining above him, a handful of willow trees visible in the distance.

Next to him, Amelia was sitting cross-legged in a small patch of grass, a pile of flowers being careful strung into a flower crown in her lap.

“Isn’t this nice?” she asked him, grabbing his hand and pulling him next to her. Sherlock was struck by the way the sun hit her hair, pulling the reds out in a fiery blur. She leaned over, gently setting the flower crown on his head.

“We should go to the countryside,” she mused, leaning back, closing her eyes, and letting the sun warm her skin. “Or maybe visit my mom’s summer house back home.”

“What is all of this?” Sherlock finally found his voice, gesturing around them.

“It’s a dream, silly,” she snorted, falling back against the plush grass. She rolled her head toward him, a long sigh relaxing her shoulders. “Peaceful, isn’t it? There shouldn’t be any Hemlock here, don’t worry.”

It was like a scene out of one of those cheesy Jane Austen BBC movies. The clouds moved lazily across the sky and Amelia continued stringing flower together, holding each one up and listing its name and informal meaning.

“Be mine?” she held up a red carnation, sitting up and smiling sheepishly over the crimson flower.

“Excuse me?” Sherlock was certain he’d misheard her.

“That’s what it means, dork,” she tucked the flower behind his ear with a flourish. “Love, compassion, romance, be mine…”

His hands touched the silk-like petals, pulling the flower free and twirling it between his fingers.

“Is this supposed to be a subtle message?” he teased, giving the bloom a dramatic sniff.

“Oh Sherlock, I don’t need to be subtle,” her voice morphed, lowering in tone, an Irish lilt catching the ends of her words. He looked up, the meadow was burning around them, but when he went to reach for Amelia’s hand, it was gone.

“Asphodel grew in the underworld,” Moriarty’s voice announced from over his shoulder. “In a purgatory of sorts, between life and death, the worthy dead and the unworthy.

Asphodel’s filled the field, the smoke sweeping over the landscape, creating a grey haze amongst the white flowers.

“Are you worthy?” he taunted, following Sherlock as the detective scrambled to his feet and started toward the willow trees. “Deadly nightshade.. Belladonna, one of the most toxic plants on earth… Hemlock… well, you know all about that now, don’t you?”

The plants sprung up around his feet.

“I told you I was going to burn the heart out of you,” Moriarty continued, strolling through the deadly plants. “I didn’t think it’d be so easy. Pathetic, Sherlock.”

Sherlock ran and ran. Something in his chest told him to keep heading toward the willow trees, but no matter how quickly he sprinted, they stayed the same distance away.

“Better get out now, Sherlock,” Moriarty cackled, plucking Belladonna and tucking it in his hair. “Get out while you can.”

Sherlock jolted awake with a start, his heart thrumming against his ribs. It took a moment for his eyes to adjust to the darkness in his room, the moon still shining outside his window.

Only a dream. He ran a hand down his face, taking a deep breath.

An image of Amelia with flowers woven through her auburn curls flashed through his mind's eye. Laughing, the sky blue and bright behind her. Peaceful.

I will burn the heart out of you.

~~~

“Amelia, what’s your middle name?” Sherlock asked a few days later. Amelia was in the kitchen attempting her hand at some homemade chocolate chip cookies.

“You don’t know?” John lowered his newspaper, peeking up at the detective in surprise. “I know something you don’t?”

Sherlock looked to John incredulously, pausing to ensure he’d read his friend’s reaction correctly.

“How do you know?” he demanded, looking between him and Amelia for an answer.

“He helped me fill out the paperwork for long term residence,” Amelia shrugged, opening the oven to check on her baked goods. “It isn’t a big deal, I figured you already knew.”

“No, don’t tell him,” John called out.

“He’s just going to dig up my social security card or something,” Amelia replied frankly, hand on her hip. “I’d rather him not disturb my filing system. I finally organized it last night.”

She wasn’t wrong, Sherlock mentally relented. He already had a plan for how he intended to go about finding it, starting with Mrs. Hudson and the original rental application. It wasn’t cheating if he accidentally saw it on the paperwork.

“Then what is it?” Sherlock pressed, earning a long sigh from John.

Amelia laughed at John’s reaction. Fishing through the cabinets, she pulled out a pair of oven mitts, focusing completely on the task at hand.

She pulled out the cookie sheet, the scent of the cookies floating through the apartment.

Sherlock reached for one but was swatted away by a spatula wielded by the American.

“They need to cool,” she snapped. “And they’re for John. You know, our dear, injured friend?”

“What’s your middle name?” he tried again, sidestepping her and approaching the tray from behind.

“Ophelia,” she answered, spinning and swatting his hand again. He waited for her to look away, deciding to distract her for the time being.

“Amelia… Ophelia…?” Sherlock paused, pulling his hand away from the tray when she sent him a pointed glare.

“Yes,” came her calm response.

She explained that her mother had been on a Hamlet kick around the time of her birth, and her father had apparently thought the combination of names had been a stroke of genius.

“I guess I can’t say much,” he reasoned, grabbing one of the cookies and retreating before Amelia could swat at him. He downed the hot cookie in a single bite, his mouth hanging open. “Ah, hot… hot..”

“I told you to wait!” she scolded, shaking her head.

“He has no self-control,” John sighed.

“Amelia Ophelia purposely made them too hot,” Sherlock complained, dropping into his seat.

“There we go,” Amelia rolled her eyes, disappearing back into the kitchen to put the cookies on a plate for John. “Shall I start calling you William?”

Sherlock made a noise of disgust.

“I can’t believe you’d be so cruel, Amelia Ophelia,” he relented, stealing another cookie from John’s plate. “Telling John your full name and not me.”

“Well, William Sherlock Scott Holmes,” she pulled off her apron and stood in the doorway between rooms, arms crossed. “I had just assumed you’d done a thorough background check.”

“I would never violate the privacy of a friend,” he lied.

Both Amelia and John snorted in response.

“You’re the one who so rudely pick-pocketed me and stole my identity,” he continued, taking a large bite out of the cookie. He pointed it in her direction. “I would never.”

“Why the sudden interest?” she asked, grabbing a tray of clean cups and a freshly poured tea kettle, setting it between the men.

“I just wanted to know,” he shrugged indifferently. That wasn’t a lie.

“Amelia Ophelia Holmes,” John hummed mockingly, sending his friend a knowing look. “Sounds like a storybook character.”

Amelia rolled her eyes, fixing herself a mug of tea.

“He’d take my name,” she stated firmly. “William Sherlock Scott Brenner.”

“I hate it,” Sherlock sat up. “You’re taking Holmes.”

“Amelia Holmes,” she tried, pulling a face of disgust. “Amelia Holmes-Brenner.”

“Mia Holmes has a nice ring,” John supplied, earning a low groan from his friends.

“John Hamish Holmes sounds even better,” she stole a cookie from his plate when he glared at her in offense, giggling as she took a bite.

“Sherlock Watson,” Sherlock tried, shrugging. “Not terrible.”

“Amelia Watson,” John shot back, guarding the remainder of his cookies from the pair.

“Amelia Ophelia Watson,” Sherlock corrected sharply. “A very important distinction.”

“William Watson,” Amelia perked up. “I think that’s my favorite so far.”

“It isn’t fair when you use alliteration,” Sherlock protested. “And I don’t go by William.”

“Why not? It’s definitely fitting for a distinguished English gentleman such are yourself.”

“Stop it or I’m referring to you as Mrs. Holmes in front of Mycroft and leaving you to fend for yourself,” he threatened.

“He’d probably think you married me against my will,” Amelia shot back, smirking. “Obviously to steal my fortune like some dastardly Victorian-era villain. We should get you an evil little mustache.”

“Oh, and he can wear the deer hat,” John agreed quickly.

“Like Spock when they went into the parallel universe?” Amelia lit up, shoot ideas back and forth with John until Sherlock stood up.

“I’m not growing a mustache,” he declared.

“It’s okay, we know you can’t,” Amelia nodded solemnly.

“I can, I just choose to be clean-shaven,” he protested, starting for the kitchen. "It's more professional."

“Ok Sherlock,” she flashed that pleasant smile. That dumb smile she did when she didn’t want to be rude.

“I’m telling the truth,” he paused and reached over John’s shoulder for the final cookie.

“I’ve never seen it,” John shot back.

“The truth comes out,” Amelia pointed to the doctor. “Don’t be embarrassed Sherlock, I can’t grow one either.”

“I’m due to meet Molly,” Sherlock grabbed his jacket, throwing it over his shoulders with a huff.

“Don’t forget your scarf,” Amelia called. “Don’t want your poor face getting frostbite. Lack of protection and all…”

“Remind me why I let you move in?”

Chapter 16

#sherlock#sherlock original female character#sherlock bbc#sherlock fanfiction#sherlock/OFC#sherlock/oc#john watson#watson#fanfiction#fanfic#writing#sherlock/reader#reader#OFC#OC

0 notes

Text

Criminal homework help

In the discussion for this unit, you explored the documentary Child of Rage, with an emphasis on finding best practices and the importance of forensic protocols in structuring interviews. In this activity, your task is to find 5 examples of real-life cases reflecting interviews using poor forensic practice. In finding these examples, place an emphasis on cases involving children, adults, and the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

What Are The Five Phases Used In Child Forensic Interviewing?

Forensic interviewing, characterized by its structured and systematic approach, plays a pivotal role in legal and law enforcement investigations. This methodical process, encompassing various forensic interview models and protocols, ensures the extraction of accurate and reliable information from individuals involved in a case.

1. Introduction and Rapport Building:

The forensic interview structure begins with the crucial phase of introduction and rapport building. Interviewers adeptly introduce themselves, articulating the purpose of the interview and following established forensic interview protocols. This phase lays the groundwork for trust and rapport with the interviewee, a foundational element in both general forensic interview structure and specialized child forensic interview structures.

2. Background Information:

Within the broader forensic interview model, the second phase involves the meticulous gathering of essential background details. Interviewers follow forensic interview protocols to collect comprehensive information about the interviewee's personal life and relationships, ensuring a holistic understanding of the case. This phase is particularly crucial in both general and child forensic interview structures.

3. Open-Ended Narrative:

At the heart of the forensic interview structure lies the open-ended narrative phase. Here, interviewers adhere to established forensic interview models, allowing the interviewee to recount events in a chronological and unstructured manner. This phase is critical not only in the general forensic interview structure but also in specialized child forensic interview structures, ensuring the preservation of the interviewee's perspective.

4. Focused and Probing Questions:

Transitioning within the forensic interview model, the fourth phase involves the use of focused and probing questions. Interviewers, guided by forensic interview protocols, ask specific questions to refine information. This phase is instrumental in enhancing accuracy, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of events in both general and child forensic interview structures.

5. Closure and Summary:

The closure and summary phase, integral to the forensic interview structure, is conducted with professionalism and adherence to established protocols. Interviewers recap key points and address remaining questions, preparing the interviewee for potential follow-up actions. This phase serves as a considerate conclusion, emphasizing the professionalism inherent in forensic interview models.