#hellenistic philosophy

Text

Current reading is Julia E. Annas' excellent Hellenistic Philosophy of Mind, a relatively short but densely packed look at how the Stoics and Epicureans conceived of thoughts, actions, and emotions. Annas does a fine job of laying out the strengths and weaknesses of ancient theories of mind--e.g. the Stoics' emphasis on language as the vehicle of thought, which allowed them to develop a sophisticated theory of rational action in humans, but also led them to deny that nonhuman animals are capable of decision making. She's also very good on the complex relationship that Hellenistic philosophy had to science and medicine: major thinkers of the day sometimes reworked their theories to accommodate the latest scientific discoveries, but at other times spurned innovation in favor of appeals to "common sense". Overall, it's a solid introduction to a complex and intriguing subject.

#personal#current reading#tagamemnon#ancient philosophy#Hellenistic period#Hellenistic philosophy#Stoicism#Epicureanism

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

An article I wrote has finally been published, on how Augustine uses St. Monica to show Christianity's superiority as self-help.

Here's the abstract:

Moralistic Therapeutic Holiness

A Catholic Defense of Philosophy as Therapy for the Soul

Christian Smith has described the religious attitudes of American youth and many adults as Moralistic Therapeutic Deism. In this formulation the word “therapeutic” does much work, and is meant to indicate that the goal of life is to be happy, to which end religion is instrumental. Martha Nussbaum has argued that Hellenistic schools of philosophy were therapeutic and instrumental in much the same way, and that this is a possible mode of philosophy even today. Appealing to the historical investigations of Pierre Hadot and Giovanni Reale, this paper shows that Neoplatonism was an even more successful form of therapeutic philosophy, a fact which Augustine recognized and to which he responded in his therapeutic masterpiece Confessions, through his depiction of his mother as a sage. This suggests that Catholicism can be powerful when presented therapeutically, which might be a more appropriate mode for evangelism in our therapeutic age.

#st. augustine of hippo#saint monica#neoplatonism#hellenistic philosophy#martha nussbaum#moralistic therapeutic deism#acpa

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

🟣 Titus Lucretius Carus / Lucretius / Philosophy #Lucretius #Philosophy

"TO NONE IS LIFE GIVEN IN FREEHOLD; TO ALL ON LEASE."

LUCRETIUS TITUS LUCRETIUS CARUS WAS A ROMAN POET AND PHILOSOPHER.

#youtube#titus lucretius carus#lucretius#philosophy#education#inna besedina#wisdom#wisdom quotes#ethics#metaphysics#educational#philosophical quotes#quotes#self-development#self-growth#hellenistic philosophy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curiously, in the fifth Ennead we see Plotinus assert the following:

The evil that has overtaken them has its source in self-will, in the entry into the sphere of process, and in the primal differentiation with the desire for self ownership. They conceived a pleasure in this freedom and largely indulged their own motion; thus they were hurried down the wrong path, and in the end, drifting further and further, they came to lose even the thought of their origin in the Divine.

It would seem that in this sense Plotinus anticipated and even inspired the theology of Augustine, who beleived that all human souls were fallen because of an originary pride. I don't find this idea to be entirely separate from the Gnostic account of Sophia's desire to imitate God, and later Yaldabaoth's creation of the physical world, despite Plotinus' objection to Gnostics for believing that the universe is inherently corrupt. I think that has interesting implications for Plotinus, not many of which I find favourable.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hermetica: The Ancient Greek and Latin Writings which contain Religious or Philosophic Teachings ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus

#hermetica#corpus hermeticum#hermeticism#hermetic philosophy#egyptian philosophy#greek philosophy#hermes#hermes trismegistus#mercurius#thoth#ascelipius#hellenistic#late antiquity#library of alexandria#greco-roman egypt#emerald tablet#gnosis#gnosticism

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

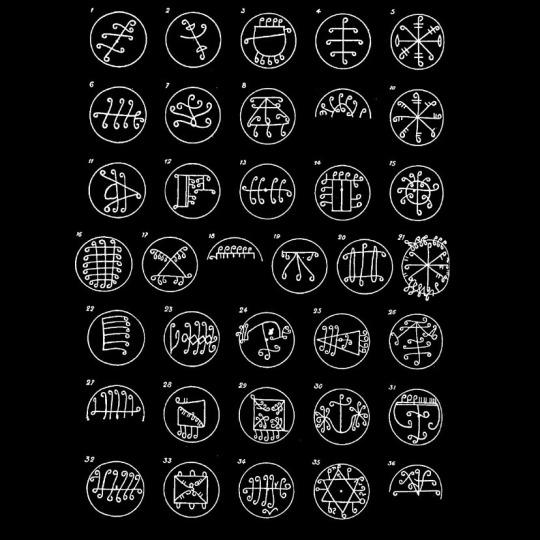

Sigils of the 36 Decans from the Catalogus Codicum Astrologorum Graecorum, a compilation of translations of Greco-Egyptian magical texts on the Decans and their uses.

The names of the Decans as given in the catalogue:

𓇼PARKHÁM

𓇼OUALÁKH

𓇼DELPHAÁ

𓇼ZAKKHÁL

𓇼KHOUNTHÁ

𓇼ANESIOÚM

𓇼PARESKHÁRTI

𓇼HIERASESÊR

𓇼ANASÁM-TETÊKH

𓇼SARKHAÁM-KOMPHES

𓇼TENOÚM-TANLÁKH

𓇼TROUKHÁP-IÁLEM, SAMPÁKH

𓇼APHÁKH-MPEÍTH, PANKHATÁP

𓇼TALANTÍS-KHARKHÁM

𓇼DEROPOÚT

𓇼MENAÍM-KHILLÁ

𓇼MPEÍ-PHOLÁKH

𓇼MARKHEM

𓇼ZÁKH-MEM

𓇼SEPTETÚL

𓇼SELOUÁKHAM

𓇼AMPÁNAN TZÉNGGIKH

𓇼LÁPH-MEÍKH

𓇼ARKHÍMOI-IELOÚPH

𓇼ANASÁM-TERIKHEM

𓇼MAKHRÁM

𓇼KHALKHÊM-IKHÉM

[Capricorn is missing]

𓇼BAZEÍNKH

𓇼KHOUNLIÁKHM

𓇼MAKHILOÚKH

𓇼KAÍN-KHÁM

𓇼POKH-MELLEPH

𓇼SUREM-OLÁKHM

#hermetismo#hermeticism#hermetic philosophy#hermetic library#hermetica#Egyptian decans#decans#decan spirits#star spirits#astrology#astrological magic#hellenistic astrology#ancient astrology#astrology witch#astrologycommunity#traditonal astrology#magicien#amulets#talismans#talismanic#sigil witch#sigil magic#sigil making#sigilcore#sigilwork#sigils#sigilyph#sigil creator#egyptian astrology

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

*sees your degree in philosophy* Ok, so Descartes was a little bitch, right? Tell me I'm not the only one who thinks that.

xD unfortunately I’m not the right person to tell you that, I actually liked Descartes from what little I *did* study him. Though I’ve seen the Descartes-hate sentiment spread around on tumblr, so I know you’re not the only one. I just have never been able to figure out why lol.

For my own sake, I know his philosophy has a lot of problems, I just view his work as a nice starting point for developing more refined ideas.

#full disclosure in my entire program I only covered Descartes ONCE and that was in intro#he never came up in any of my other classes#but that may be because I focused on Hellenistic philosophy and more contemporary issues#very rarely did I have a class that focused on a specific philosopher for any length of time

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

From what high place of honour and bliss have I fallen, so that now I go about among mortals here on earth?

Empedocles (484-424 BCE), fragment 90, anticipating Gnosticism

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I don't get all the way through my lectures, so I wrote up some notes for my students to help them study for the exam. So anyone interested gets a free history lesson today. All two of you.

<<Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BCE) was the son of Philip II, King of Macedon (382 – 336 BCE). The Macedonians were northern Hellenic Greeks whose civilization was perceived by the southern Greeks (Athenians, Peloponnesians) as borderline barbaric, although the Macedonians were as invested in Greek culture as any others. The Macedonians were able to rise to power over the southern Greeks partly as a result of the great weakening, militarily, politically, and economically, of the southern Greeks due to the Peloponnesian War.

Philip, a powerful and charismatic warlord, conquered or subdued most of the western Aegean world during his reign. His victory at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BCE) assured the submission of Athens, a southern Greek city-state Philip greatly admired. By this point, Philip’s son Alexander was participating in military campaigns, having been taught philosophy by Aristotle of Athens and having learned rigorous Spartan military techniques from his mother’s southern Greek relatives. Alexander’s natural charisma and leadership ability, combined with unusual skill and luck on the battlefield, led to him being considered by Philip and most others as the heir-apparent, despite his relatively small stature and the existence of legitimate alternatives. When Philip was assassinated in 336 BCE, Alexander moved quickly to seize power, eliminating or disempowering all rivals. For his first two years as king of Macedon, Alexander consolidated the Greek empire Philip had built and established his firm control over the army. Then, in 334, he set out to the east to initiate his father’s ambition of conquering the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire.

Alexander’s campaigns in the east lasted the remainder of his life, more than ten years. In this time, the young king conquered and ruled over an empire of unprecedented size and diversity, from the Greek city states of the west to the Ganges River civilizations of the east, and south to Egypt. Alexander’s success in battle was a result of a ruthless, clever strategy of offering every major city-state the chance of a peaceful surrender, to which he would hold his troops accountable, or, if the citizens chose to defy him, to crush their resistance without mercy. As the Plutarch source you are reading emphasizes, Alexander could be kind and gentle on the one hand and absolutely brutal on the other, without seeming to lose the loyalty of his army. Alexander led campaigns personally and was frequently in physical danger, but very rarely wounded. He was perceived as lucky and brave, and his men were fanatically loyal.

Alexander’s rule over this vast empire was achieved through the establishment of a centralized bureaucracy that relied heavily on his loyal retainers left behind in major population centers. Alexander required his men to marry into the local populations, so that city leaders would have a family tie to his rule and be more likely to oppose rebellion. Alexander himself married three times, as Macedonian custom did not forbid multiple marriage. In his personal life, Alexander was almost certainly bisexual, having been known to have male lovers who accompanied him on his campaigns for most of his adult life. However, his marriages to women were fruitful and he was reputed to admire beauty in any form.

The tremendous loyalty and love Alexander inspired can be observed in Plutarch’s story about his acquisition of his famous war horse, Boukephalos/Bucephalus (ox-head). Alexander tamed a horse no one else wanted and kept that horse with him for most of the rest of his life. When Bucephalus died, shortly before Alexander, the king threw him a funeral to rival that of royalty.

As Alexander made his triumphant way south toward Egypt, he found he didn’t always have to fight, as his reputation preceded him. Culturally, he was very open-minded and tended to enthusiastically adopt his favorite customs of the new peoples and civilizations he encountered. He won virtually every battle he fought and often endeared himself to locals who despised the Persians. This was particularly true in Egypt, where he stayed for some time and was even declared pharaoh, a living god, by the priests. In Egypt, he founded a capital city in the swamplands of the delta region of Lower Egypt and, as was typical, named the city after himself. It is still called Alexandria, and it became one of the great cities of the ancient world. Alexander is buried somewhere in it.

Alexander turned his attention to Darius III, King of Persia. Having defeated Darius’ numerically superior forces several times, forcing the king to flee, Alexander took over Mesopotamia and the entire eastern half of the Persian Empire before Darius was finally captured and killed by his own men. Alexander’s key to success in his Persian campaigns appeared to be the speed and unpredictability of his military movements. While Darius had a massive court that took days to move a few miles, Alexander required few luxuries and moved much more quickly. After Darius’ death, Alexander had himself declared Darius’ heir and king of the Persians. In this capacity, he subdued the rest of the Persian Empire all the way to the Ganges River.

There, despite Alexander’s desire to cross the vast river and conquer the mysterious civilizations of the Far East, the young king faced mutiny for the first and last time. His troops, previously so loyal, refused to participate. They feared the unknown, were tired of fighting, and longed to go home. Heartsick, Alexander agreed, but continued to campaign and led the way back west through brutal desert, losing much of his army along the way.

Alexander died shortly after returning to Mesopotamia in the city of Babylon, in the fabled palace of Nebuchadnezzar II. He was known to be sick for two weeks before his death, but rumors of poisoning persisted, despite it being very unlikely that such a long-acting poison would be effective or known. After his death at the age of 32, his leading generals quickly eliminated their rivals, including Alexander’s surviving wives and offspring, and divided up his empire among themselves into several large kingdoms.

The post-Alexander period is often called the Hellenistic Era. While “Hellenic” means “Greek,” “Hellenistic” means “influenced by Hellenic Greek culture.” Therefore, the Hellenistic world is the one created by the blending of the Greek cultures of the Aegean with the various other cultures (Persian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Semitic, etc.) of the regions Alexander conquered. The cultural center of the Hellenistic world was in Alexandria, Egypt. Egypt was ruled by descendants of Alexander’s general Ptolemy, founding a Macedonian dynasty that would reign over Egypt for the next 300 years. Although Alexander had died in Babylon, his body was eventually moved to Alexandria, Egypt, where it was reported to have been seen as late as the Roman era. It is now lost to history, as Alexandria is a sea-level city and the ancient palace complex is very difficult to excavate, given the water table.

The city of Alexandria became home to the great library, essentially an ancient university system that housed not only the most important books of the ancient world (up to 500,000 hand-written scrolls and codices), but also became a research and development facility for scientists, philosophers, and technicians of the age. Geographers accurately estimated the circumference of the world. Astronomers traced the paths of planets and mapped the stars. Physicists discovered principles and formulas that would continue to be used into the Newtonian era.

Throughout the Hellenistic world, a simplified form of Greek called koine was spoken and written as a business language, regardless of local speech. Metal currency was used as a medium of trade, which flourished throughout this enormous area, creating a highly cosmopolitan blended civilization that characterizes the Hellenistic Era.

However, any romantic attachment to the ideals of Athenian democracy was essentially pointless sentimentality. Alexander, for all of his good qualities, was a tyrant and a despot. His successors were also uncompromising monarchs, more like the Persian king Alexander had replaced than the Athenian politicians Aristotle had taught him to admire. Philosophical traditions of the Hellenistic era reflect this change in ideals about government. Philosophers seemed more interested in discovering how to cope with a world beyond their control than in perfecting a world they understood. Hellenistic philosophy in general reflects a withdrawal from political activity and a resignation to the fact that humans had little say in their own destiny.

Epicureanism was one Athenian philosophy that took this approach. Based on the teachings of Epicurus (341 – 270 BCE), Epicureanism took after Aristotelianism somewhat in that moderation was considered the key to a successful life. Epicureans believed that misery was due to excess. Therefore, pleasure should be pursued, but in a cautious and temperate way. Avoiding pain was paramount, and overindulgence in pleasure usually produced pain. Life, therefore, was an exercise in avoiding those things that cause fear or anxiety. Since fear of death can destroy a person’s happiness, Epicurus taught that it made no more sense to fear death than it did to fear the world that existed before you were born.

Stoicism was another major philosophical movement of the Hellenistic world. This school of Athenian philosophy was founded by Zeno (334 – 262 BCE), who believed in the existence of the logos (universal reason or truth) as the force that unifies all things. Since all misery stemmed from being out of balance with the logos, Stoics avoided excessive attachment and the violent emotions that came with it, practicing fortitude and self-discipline when confronted with problems. Thus they developed a reputation for being unemotional, when in truth they were simply learning to control their emotional responses to avoid losing their connection with the logos.

Skepticism was another approach to dealing with an uncertain world. We know less about this philosophy’s Hellenistic version because most of the writings of its practitioners have been lost, but the basic idea of skepticism is that nothing is certain and knowledge is not really possible. Thus, in order to achieve tranquility, one must exist in a constant state of doubt. Nothing should be taken for granted and all things should be questioned. Socrates was an early skeptic in many ways, but the Hellenistic practice of skepticism was different in that Socrates believed truth and morality existed; skeptics of the Hellenistic period were not certain of anything.

Cynicism is the most extreme of the Hellenistic philosophies. A cynic's goal was to live a virtuous life in harmony with nature, which was only possible through rejection of distracting comforts. Cynics believed all unhappiness came from attachment, because anything you are attached to can be lost. Therefore, to preempt misery, one should simply avoid all attachment and attempt to live a self-sufficient life in harmony with nature. Social customs and proprieties were limiting and meaningless. Cynics were often loners, since human company can lead to attachment, and their bizarre behavior was difficult to live with. They tended to dress, eat, and live at the extreme edge of poverty, since comforts could also lead to attachment. Practically the only pleasure Cynics allowed themselves, since it was harder to take away, was the exercise of their own minds through study and contemplation. The most famous cynic of the Alexandrian period was Diogenes, who lived in a ceramic jar and begged on the streets of Athens.

All of these Hellenistic philosophies lack the optimistic certainty that society and the individual can be perfected that characterized classical philosophy. Hellenistic thinkers were more concerned with how to survive a world they don’t control than with how to create a better world. Democracy was a distant memory; living under the rule of tyrants was the expectation of the Hellenistic world.>>

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

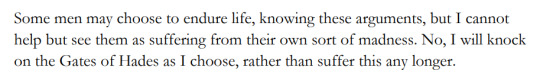

Apokarteron / Hegesias

#mood#📖#hegesias#hegesias of cyrene#greek philosophy#hellenistic literature#hellenistic#hellenism#ancient greek#hades#quote#literature#philosophy#eudaimonia#death#unalive#depressive#existential nihilism#philosophical pessimism#upload#p

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

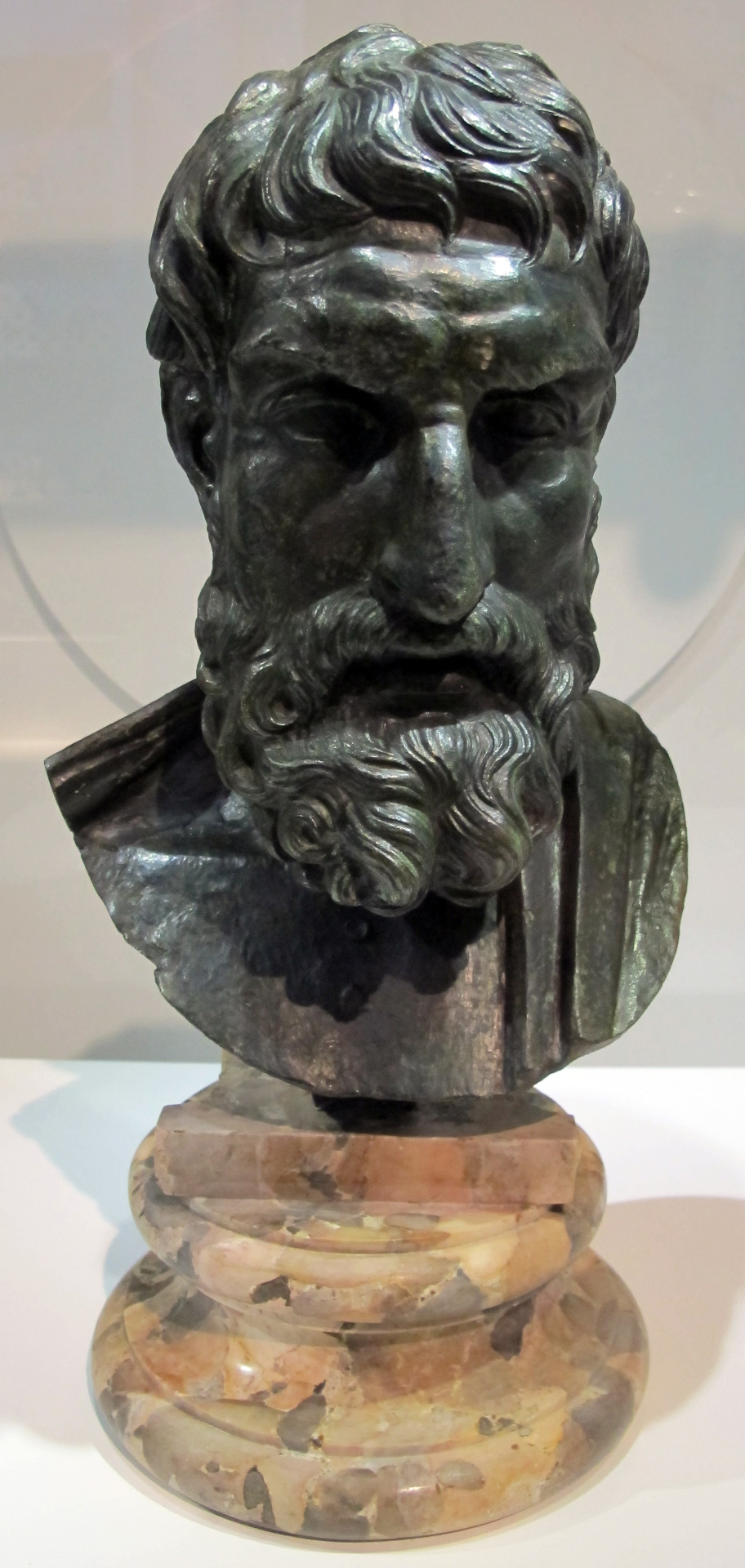

A Hymn to Epicurus

Lucretius, De Rerum Natura 3.1-13

You who first were able, out of such great darkness,

To lift a light so bright, illuminating life’s good things,

You it is I follow, o glory of the Greek people,

And in the marks you’ve pressed I now place the fashioned

Traces of my feet – not so much desirous

Of vying with you, no, but rather out of love

That I desire to imitate you; for how could a swallow compete

With swans, or what could kids, with their shaky joints,

Be able to do in a race like a horse’s mighty power?

You, father, are the discoverer of things,

You supply to us our ancestral precepts; from

Your writings, famous one, as bees in flowering glades

Taste of all things, in like fashion we ourselves devour

All your golden sayings – golden, ever worthiest

Of life that never ends.

E tenebris tantis tam clarum extollere lumen

qui primus potuisti inlustrans commoda vitae,

te sequor, o Graiae gentis decus, inque tuis nunc

ficta pedum pono pressis vestigia signis,

non ita certandi cupidus quam propter amorem

quod te imitari aveo; quid enim contendat hirundo

cycnis, aut quid nam tremulis facere artubus haedi

consimile in cursu possint et fortis equi vis?

tu, pater, es rerum inventor, tu patria nobis

suppeditas praecepta, tuisque ex, inclute, chartis,

floriferis ut apes in saltibus omnia libant,

omnia nos itidem depascimur aurea dicta,

aurea, perpetua semper dignissima vita.

Bust of Epicurus of Samos (342-270 BCE), founder of the Epicurean school of philosophy (the Garden), from the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum. Roman copy after a third century BCE Greek original. Now in the collection of the National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Photo credit: Sailko/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Latin#Latin language#lingua latina#translation#Latin translation#Ancient Rome#Roman Republic#Lucretius#Titus Lucretius Carus#ancient philosophy#Hellenistic philosophy#Epicurus#Epicureanism#De Rerum Natura#didactic poetry#dactylic hexameter#hymn

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

(ok so here's the first ""pro-christian" bc your opinion is stinky doody" vid this class placed)

(so the video describes an absolute fukn underrated Greek philosopher named Celsus, apparently he was one of the first critics of Christianity and he actually made some ....ugh...how do I put this.....rational accusations.)

(Now this guys absolutely had some incredible insight of what he constituted as religion. His concept of religion actually is anything prior to Moses)

(apparently....Celsus practically predicted some of our current criticisms towards the church.)

(in short, this man and his roasting of the Christianity is shockingly relatable???)

(could this man be....based?)

0 notes

Video

youtube

⏳ Philo of Alexandria / Philosophy / Theology #Philo #Philosophy

"TIME IS A THING POSTERIOR TO THE WORLD. THEREFORE IT WOULD BE CORRECTLY SAID THAT THE WORLD WAS NOT CREATED IN TIME, BUT THAT TIME HAD ITS EXISTENCE IN CONSEQUENCE OF THE WORLD. FOR IT IS THE MOTION OF THE HEAVEN THAT HAS DISPLAYED THE NATURE OF TIME."

PHILO OF ALEXANDRIA

PHILO OF ALEXANDRIA WAS A HELLENISTIC JEWISH PHILOSOPHER WHO LIVED IN ALEXANDRIA, IN THE ROMAN PROVINCE OF EGYPT.

#youtube#philo#philo of alexandria#philosophy#knowledge#philosophical#philosophical quotes#theology#inna besedina#logos#ancient philosophy#middle platonism#cosmology#hellenistic judaism#philosophy of religion#wisdom#wisdom quotes#education#educational

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is something worth observing in Plotinus' critique of "Gnosticism" as elaborated in his Enneads. In the last section of the ninth tractate of the second Ennead, Plotinus outlines a counter to the "Gnostic" abandonment of the body, which Plotinus evidently saw as the seat of virtue.

He applied the following curious analogy:

In other words: two people inhabit the one stately house; one of them declaims against its plan and against its Architect, but none the less maintains his residence in it; the other makes no complaint, asserts the entire competency of the Architect and waits cheerfully for the day when he may leave it, having no further need of a house: the malcontent imagines himself to be the wiser and to be the readier to leave because he has learned to repeat that the walls are of soulless stone and timber and that the place falls far short of a true home; he does not see that his only distinction is in not being able to bear with necessity assuming that his conduct, his grumbling, does not cover a secret admiration for the beauty of those same "stones." As long as we have bodies we must inhabit the dwellings prepared for us by our good sister the Soul in her vast power of labourless creation.

Then, Plotinus further trashes the "Gnostics", basically accusing them of being too corrupt to have any kinship with the cosmos, and then goes on to explain what it means to be able to possess that kinship.

Or would this school reject the word Sister? They are willing to address the lowest of men as brothers; are they capable of such raving as to disown the tie with the Sun and the powers of the Heavens and the very Soul of the Kosmos? Such kinship, it is true, is not for the vile; it may be asserted only of those that have become good and are no longer body but embodied Soul and of a quality to inhabit the body in a mode very closely resembling the indwelling. of the All-Soul in the universal frame. And this means continence, self-restraint, holding staunch against outside pleasure and against outer spectacle, allowing no hardship to disturb the mind. The All-Soul is immune from shock; there is nothing that can affect it: but we, in our passage here, must call on virtue in repelling these assaults, reduced for us from the beginning by a great conception of life, annulled by matured strength.

And then

Attaining to something of this immunity, we begin to reproduce within ourselves the Soul of the vast All and of the heavenly bodies: when we are come to the very closest resemblance, all the effort of our fervid pursuit will be towards that goal to which they also tend; their contemplative vision becomes ours, prepared as we are, first by natural disposition and afterwards by all this training, for that state which is theirs by the Principle of their Being.

What is clear from all of this is that Plotinus established an idea within his proto-Neoplatonist system of Hellenistic Platonist philosophy of the possibility of becoming-divine. It is essentially by way of a contemplative and moralistic asceticism in which the body, though affirmed as a seat of virtue and contemplation of the All, must abjure the pleasures that it is capable of experiencing for itself, in order that it may, in theory, imitate the soul of the All, and the acquire the attributes of the heavenly bodies, and thereby a divine state of existence.

It is insufferably moralistic, in a way not unlike Christian counsels to "modesty" or "temperance" or such phantasms. Nonetheless, the horizon of becoming-divine it presents is clearly not something that Christianity would tend to propose. I would assume that no Christian, not even a "Gnostic" Christian, would see themselves as trying to become a divine being or celestial body, or really anything other than a soul "saved" by God and permitted to "live" forever in Heaven after death.

I do think, though, that perhaps there's something to be said of the horizon of interpreting "transition from body to embodied soul" in terms of the way Bronze Age Collapse talked about "absolute fitness" as the divine existence as force or atmosphere, as though to become energetic, or atmospheric. That would seem radically different from Plotinus' meaning if we assume Plotinus meant this transition as a moral existence.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know you’re not a philosophy professor but I can’t get my head around Logos, whether the original Greek or later Christian interpretation of it.

Any chance you can explain it like I’m an idiot?

No this is actually my lane! You'll see why in a sec. Okay your confusion is probably the fact that there's several Greek interpretations.

Plato and Aristotle: Logos just means discourse. It's the principle of rhetoric that appeals to reason.

Plotinus: this mfer was a neoplatonist. He's sorta the bridge between Greek philosophy, gnosticism, and Hellenistic Judaism. For him, Logos is the principal of meditation. It's the strings that conects hypostases. If you think of all of reality as a sort of metaphysical ladder, with human souls at the bottom, and The One at the top, the ladder is logos.

Christianity: Logos is the pre-extant second part of the Trinity. It's the thing Christ was before he was incarnated as Christ. Christ is still considered the logos, as far as I'm aware. Don't quote me on that.

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

There was an ancient Greek philosopher named Antiochus of Ascalon who was nicknamed "The Swan" because he was convinced that living with perfect virtue "according to nature" meant achieving both mental and physical perfection, which (apparently) inspired him to incorporate long graceful, flowing bodily movements into his everyday mannerisms. Like a swan.

But Antiochus also taught philosophy to Cicero in Athens so I'd like to imagine the possibility that Mr. Impressionable Hellenist Marcus Tullius Cicero started picking up these habits subconsciously only to go back to Rome and instantly be ridiculed by everyone.

371 notes

·

View notes