Text

Here is my medieval lesbian nun essay for those interested!

Her Noble Beloved: Lesbian Eroticism and Faith in Medieval Convent Life

For almost as long as nuns have existed, the existence of lesbian nuns has been a topic of endless speculation, derision, titillation and fascination, and yet very little is known about the actual lived experiences of the nuns who engaged in such relationships. Because of the fact that women have been mostly ignored throughout history both in their own times and by historians, and the fact that homosexuality has been both loosely defined and hidden throughout most of Christian history, it is difficult to put together an understanding of who the lesbian nuns of the Middle Ages were, what their lives were like, or what defines a woman as lesbian at all. In more recent years, there have been several sources collected uncovering a hidden history of medieval nuns who could be understood as lesbians, either through engagement in homosexual acts, envolvement in passionate close friendships and/or creation of homoerotic literature and poetry.

However, even though there is now a general agreement that lesbian nuns have existed and even some information on how they lived their lives, there is still a common misconception that lesbian sexuality in convents existed despite or even in contradiction to the faiths of the nuns involved. This is assumed because throughout its existence the Catholic Church has condemned homosexuality. However when looking at the records left behind by nuns themselves, it becomes clear that they did not see their lives in that way. I will argue that not only did many nuns view their lesbianism as an important and positive part of their faith and relationship with Christ, but that understanding lesbian nuns is integral to understanding the role of nuns and convent life in the history of Christianity overall.

In order to develop a fruitful understanding of the ways in which lesbianism has played a role in the history of convent life, it is first necessary to define the term “lesbian” as it is being used in this paper. “Lesbian” in the modern sense refers to a particular social and political category and identifier for women who engage solely in romantic and sexual relationships with other women. This definition has emerged mostly in the past 150 years, and is not applicable for understanding the lives of women in the Middle Ages. There was no such thing in medieval Europe as an identity for homosexuals, rather there were only people who engaged in homosexual acts. The few records of female homosexual sex acts in the era are all from records of legal proceedings and criminal persecutions, and those acts were grossly misunderstood. If it is difficult to uncover histories of male homosexuals, it is even harder to create lesbian histories because, as Judith M. Bennett simply explains, “Women wrote less; their writings survived less often… and they were less likely than men to come to the attention of civic or religious authorities.”

Furthermore, since the historical understanding of homosexuality at the time has been defined solely on the basis of sex acts, it ignores “the evidence… of intense emotional and homoerotic relations between medieval nuns.” Bennett explains. Both the modern and historical definitions of female homosexuality are not appropriate for understanding a history of lesbian women in the historical contexts they existed in. Because of this, I am using part of Bennett’s definition of “lesbian-like” as “women whose lives might have particularly offered opportunities for same sex love.” This is how the term “lesbian” should be understood as it applies to the women discussed in this paper.

Some medieval convents were places of learning and scholarship, where nuns were not only literate and well read but produced works of theology, poetry and literature. In some of the works that were produced in these convents, there can be found poetry and prose which celebrates amorousness and homoerotic love between women. Hadewijch, a thirteenth century Flemish Beguine (woman who lived in monastic poverty without taking official vows), wrote often on the theme of Minne, or love, the same word often used in secular romantic poetry of the time. In Hadewijch’s writing, the Minne she expresses towards her fellow Beguines is inextricably linked with her love of Christ. As Professor E. Ann Matter explains, “these writings stress that only through the imperfect experience of earthly love can union with the heavenly lover be glimpsed.” In Hadewijch’s “Letter 25,” the section addressed to a fellow Beguine named Sara is a clear example of the important relationship between lesbian love and love for Christ in the monastic lives of women.

“Greet Sara also on my behalf, whether I am anything to her or nothing.

Could I be fully all that in my love I wish to be for her, I would gladly do so; and

I will do so fully, however she may treat me. She has largely forgotten my

affliction, but I do not wish to blame or reproach her, seeing that Love [Minne]

leaves her at rest, and does not reproach her, although Love ought ever anew to

urge her to be busy with her noble Beloved. Now that she has other occupations

and can look on quietly and tolerate my heart’s affliction, she lets me suffer. She

is well aware, however, that she should be a comfort to me, both in this life of

exile and in the other life in bliss. There she will indeed be my comfort, although

she now leaves me in the lurch.”

The intensity of Hadewijch’s love for Sara is apparent in this writing, and as Matter puts it, “whether or not their relationship was explicitly sexual, it seems a possible interpretation that Hadewijch and Sara were ‘Particular Friends.’” Notably, it is through this love that Hadewijch urges Sara towards the “noble Beloved,” Christ. The lesbian affections present are far from a contradiction of Hadewijch’s faith, rather they are an integral part of it.

In other works produced by nuns, the passionate love expressed between women extends into the territory of the erotic. In one poem written by an unknown author in the twelfth century in a Bavarian women’s monastery, the female poet addresses another woman in the style of finamour- courtly love- with the poet acting as the lover and the subject the beloved.

“To G.; her singular rose

From A. the bonds of precious love.

What is my strength, that I may bear it,

That I should have patience in your absence?

Is my strength the strength of stones,

That I should await your return?

I, who grieve ceaselessly day and night

Like someone who has lost a hand or a foot?

Everything pleasant and delightful

Without you seems like mud underfoot

I shed tears as I used to smile,

And my heart is never glad.

When I recall the kisses you gave me,

And how with tender word you caressed my little breasts,

I want to die

Because I cannot see you.

What can I, so wretched, do?

Where can I, so miserable, turn?

If only my body could be entrusted to the earth

Until your longed-for return

Or if passage could be granted to me as it was to Habakkuk

So that I might come there just once

To gaze on my beloved’s face-

Then I should not care if it were the hour of death itself.”

This poem is quite remarkable for its seeming overt lesbian sexuality, to the point that John Boswell has called it “perhaps the most outstanding example of medieval lesbian literature.” However, although the content of the piece itself is exceptional, it is fairly conventional in terms of structure and themes. It is composed of rhymed couplets and, Matter explains, tonally echoes the spirituality of medieval readings of the Song of Songs. Even as the piece pushes the boundaries with its eroticism, it harkens back to and celebrates a deeply rooted Christian faith in its language and style. Additionally, Matter notes that the piece fits within “the sophisticated and venerable tradition of spiritual friendship.” And its theme of “longing for the absent beloved” situates it among the many works of verse on the topic of courtly love, a concept also explored by Hadewijch in her writing.

While Hadewijch expressed affection and intimacy for her monastic sisters, and the anonymous poet above composed erotic love verses, one later nun’s lesbian affair made her an exceptional and outrageous figure- and an invaluable reference point for understanding the complexity of lesbian nuns’ relationships with their faith, Christ, and the Church.

Benedetta Carlini was an exceptional woman even before the sex scandal which she is known for. She became a nun in a fairly common way, being brought to a convent at the age of nine by her parents. She was from a well-off family as evidenced by her literacy, and managed to become Abess of the Convent of the Mother of God before the age of 30. She is best known, however, for her sexual relationship with fellow nun Bartolomea Crivelli which was documented in Ecclesiastical records from 1619-23. While this places her in a slightly later time period than the other women discussed in this paper, it is still important to consider her case as it is the most well documented case of a sexual relationship between nuns in the Medieval or Early Modern period, and furthermore much of the detail is taken directly from the testimony of Bartolomea, albeit recorded by a male scribe. While it is important to note that the truth of the relationship may be obscured by the women’s attempts to minimize their actions as well as the misunderstandings and misgivings of the authorities creating documentation, it is still a remarkable record of the life of a lesbian nun and how her faith was deeply interwoven with her sexuality.

One document describes the sex acts of Benedetta and Bartolomea in detail. However, Judith C. Brown notes, “because [the authors] lacked an imaginative schema to incorporate the sexual behaviors described, they had a rather difficult time assimilating the account.” She further explains that as the sex acts are described, the handwriting of the document itself deteriorates and words are crossed out, rewritten, or completely illegible.

“For two continuous years, two or three times a week, in the evening after disrobing and going to bed and waiting for her companion, who serves her, to disrobe also, she would force her into the bed, and kiss her as if she were a man she would stir herself on top of her so much that both of them corrupted themselves because she held her by force sometimes for one, sometimes for two, sometimes for three hours. And [she did these things] during the most solemn hours, especially in the morning, at dawn. Pretending that she had some need, she would call her, taking her by force she sinned with her as was said above. Benedetta, in order to have greater pleasure, put her face between the other's breasts and kissed them, and wanted always to be thus on her. And six or eight times, when the other nun did not want to sleep with her in order to avoid sin, Benedetta went to find her in her bed and, climbing on top, sinned with her by force. Also at that time, during the day, pretending to be sick and showing that she had some need, she grabbed her companion's hand by force, and putting it under herself, she would have her put her finger in her genitals, and holding it there she stirred herself so much that she corrupted herself. And she would kiss her and also by force would put her own hand under her companion and her finger into her genitals and corrupt her. And when the latter would flee, she would do the same with her own hands. Many times she locked her companion in the study and making her sit down in front of her, by force she put her hands under her and corrupted her; she wanted her companion to do the same to her and while she was doing this she would kiss her. She always appeared to be in a trance while doing this.”

The prurient detail of the document is astonishing considering the sexual taboos of the time, however what follows is even more fascinating as the Benedetta’s role in the affair takes on a fascinating mystical and religious element.

“Her Angel, Splendidiello, did these things appearing as a boy of eight or nine years of age. This Angel Splendidiello, through the mouth and hands of Benedetta, taught her companion to read and write, making her be near her on her knees and kissing her and putting her hands on her breasts…

This Splendidiello called her his beloved; he asked her to swear to be his beloved always and promised that after Benedetta's death he would always be with her and would make himself visible. He said I want you to promise me not to confess these things that we do together, I assure you that there is no sin in it; and while we did these things he said many times: give yourself to me with all your heart and soul and then let me do as I wish...

He made the sign of the cross all over his companion’s body after having committed with her many dishonest acts; [he also said] many words that she couldn't understand and when she asked him why he was doing this, he said that he did this for her own good. Jesus spoke to her companion [through Benedetta] three times, twice before doing these dishonest things. The first time he said he wanted her to be his bride and he was content that she give him her hand, and she did this thinking it was Jesus. The second time it was in the choir at 40 hours, holding her hands together and telling her that he forgave her all her sins. The third time it was after she was disturbed by these affairs and he told her that there was no sin involved whatsoever and that Benedetta while doing these things had no awareness of them. All these things her companion confessed with very great shame.”

The role of Benedetta’s apparent spiritual visions in her lesbian affair raises numerous questions, the answers to which can only be speculated on. One of the most obvious considerations is the possibility that Benedetta did not in fact believe in what she was saying, and simply lied to excuse her behavior and prevent Bartolomea from going to the authorities. I believe this can be refuted on the grounds that Benedetta reported many other miraculous experiences during her life which had no association with her affair. In fact, it was during an investigation into claims that she had been visited by Christ and male angels and received stigmata that the affair was discovered in the first place.

It is entirely possible that Benedetta really believed in some or all of the experiences she claimed to have. There were many cases in the time period of nuns claiming to have visions from Christ or angels, and even precedent for those visions being in an eroticized context as in the experiences of the 12th century Hildegard de Bingen, a fellow abbess who was venerated after her death and recently canonized as a saint. While on the surface Benedetta’s claims of being possessed by Jesus during lesbian sex acts may seem outrageous, they can be better understood within the culture of the “heavenly bridegroom” which positioned Christ as a husband figure to nuns. As seen in the above writing of Hadewijch, there is precedent for situations in which the Christ as husband figure worked to sublimate lesbian desires between nuns. While Benedetta’s case is certainly an extreme version of that dynamic, it is not necessarily as idiosyncratic as it seems at first glance.

Ultimately, it is clear that rather than lesbianism contradicting their faiths, many medieval lesbian nuns actually used faith as an integral part of their lesbian affections and relationships. Be it a scorned lover urging her sister beloved to follow the noble Beloved, a monastic woman using biblical style and allusions in her erotic poetry, or a nun enacting lesbian sex acts as part of purported visions from Christ, faith played an essential part in the experience of many medieval lesbian nuns. In order to build a clearer and better rounded understanding of these women and their lives, we must unlearn the assumptions we have based on homophobic and heteronormative histories, and begin to meet these women as they understood themselves and their faith on their own terms.

Works Cited

Bennett, Judith M. “‘Lesbian-Like’ and the Social History of Lesbianisms.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 9, no. 1/2 (2000): 1–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3704629.

Brown, Judith C. “Lesbian Sexuality in Renaissance Italy: The Case of Sister Benedetta Carlini.” Signs 9, no. 4 (1984): 751–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173632.

Matter, E. Ann. “My Sister, My Spouse: Woman-Identified Women in Medieval Christianity.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 2, no. 2 (1986): 81–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25002043.

#my writing#lesbian#dykeposting#wlw#sapphic#lesbian history#lgbt history#women's history#renaissance#medieval#christianity#history of christianity#essay

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about Purgatory... (1)

Now that Hazbin Hotel is out, it is time to make some thematic posts. And what better way to begin than... the famed Purgatory.

In Hazbin Hotel, Charlie's project - and the titular hotel - is clearly meant to be what has been historically and religiously designated as "purgatory", this famed "third realm" between Heaven and Hell that apparently doesn't exist in the Hellaverse, where there is only a Heaven-Hell duality. The idea of Purgatory has been used a lot by recent media for various effects - from Supernatural's quite unique take on it, to the most recent The Good Place, passing by the viral webtoon Adventures of God.

But let's talk a bit about what Purgatory truly was, and truly has been. For this post I'll mostly rely on the writings of Christine Duthoit, for a dossier she created documenting the afterlifes in the Middle-Ages ; for her Purgatory section she notably took a lot of info from Jacques Le Goff's own study of Purgatory (Le Goff being one of our big medieval experts in France).

So... it is important to remember that the realm of Purgatory (I'm going to place caps to make clear I'm talking about the afterlife-realm) is not something that originally existed in the Christian religion. You had Heaven and Hell, but no real "Purgatory" - it was a medieval invention, in front of the Christians' own anguish when confronted to the idea of an endless damnation. More generally, the Purgatory was needed to try to explain how a God of endless love, mercy and understanding could have a realm such as Hell entirely dedicated to infinite misery and torments until the end of time. The solution to this paradox was the existence of a third issue, a third realm where people that were not bad enough to deserve infinite torture could earn a "second chance" and purify themselves of their sins to reach Heaven: the Purgatory (from the verbs and terms refering to a "purge", or the "purging" of something - in this case, to purge one's sins and evils).

However, just because the Purgatory was "invented" in the Middle-Ages doesn't mean that it doesn't have older roots. Indeed, inspired by the old concept of the Bosom of Abraham (talked about in the Ancient Testament, and then referred to by Jesus in the New Testament), the early Christians believed in a concept called the "refrigerium". The refrigerium, the "freshening" or "refreshening" of the deceased, actually had a dual meaning. At the same time, the refrigerium designated a supposed place, a "fresh" and pleasant realms where the souls awaited for the Last Judgement ; and it also designated the practice and habit of "refreshing" the memory of the dead - for example organizing ritual feasts and commemorative reunions in order to not forget the deceased. This dual belief reflected the remnants of the Roman religion in early Christianity: indeed, the Roman Empire did not actually have any precise or defined belief in any "afterlife" (despite what Latin poets might let you think). The Roman religion, being a religion of ritual rather than of belief, did not care much about any realm beyond death, but rather focused on a series of rituals to honor the memory of the dead (such as the family having meals on their graves regularly) or appease the unresting souls (the famous ghost-hunting rituals against the larvae and the lemurs). This tradition of the ritualistic "memory-keeping" of the dead stayed within early Christianity.

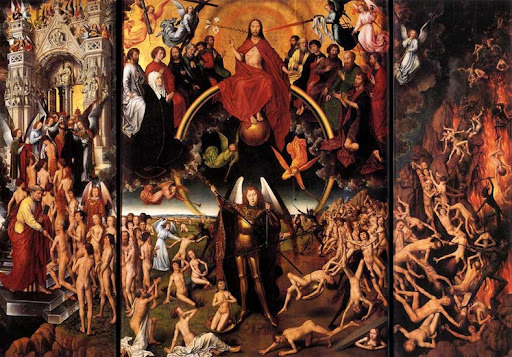

The belief in Purgatory also stems from and is heavily tied to the belief in the Last Judgement and the Resurrection - key features of the Christian religion, the idea that at the end of time God will organize a Final Judgement, the famed Judgement Day, upon all of humanity, after resurrecting all the deceased that ever were. I'm not going to lose myself too much in this complex topic - but the belief of Purgatory also comes from theologians constantly wondering and pondering what happens to the souls between death and Judgement Day, and how the Last Judgement can be "prepared".

As early as the second century, the Greek Fathers of the Church (Clement of Alexandria, or Origen) started talkeing about a "purifying fire" for the souls, but they did not develop much the idea. The Latin Church Fathers, meanwhile (Gregory the Great, Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome) talked about a "second chance" offered after death to those that did not commit very grave or heavy sins, and that consisted in purification trials. But the details were still murky and confused: nobody agreed on what those purifications were, on how long the process took, or on where they took place. But they all agreed on a common point: the idea that the prayers of the living had the power to ease the suffering and the trials of the souls of the dead. Saint Augustine, that is often considered the "father of Purgatory", started the idea that this "purifying fire" in the afterlife could only work on venial sins, and that it was located somewhere between "the death of the Christian and the resurrection of their body" ; the idea was continued by Gregory the Great, whose text Moralia in Job heavily influenced the Purgatory ideas. For those of you not versed in Christian terminology, sins are divided between venial sins and mortal sins (not to be confused with the "deadly sins"). Venial sins are minor, not-so-bad sins, that can be easily forgiven or erased by things such as sincere remorse, penitence and confession ; mortal sins, meanwhile, are grave and serious sins that cannot be fully erased and will lead your soul to Hell.

Between the 7th and the 12th centuries, the religious doctrine and official canon of the Church stayed at a dead end. Theologians, authors and other religious debaters did not dare go further into the whole "Purgatory" debate - they stayed by what the Fathers had said before them, and the debates stayed debates with no real conclusions. However, if the official teachings did not evolve, this era saw a boom in terms of popular imagination. Starting from the monasteries, there was a true wave of imagination and imageries that fed onto the many "pagan remnants" that were everywhere in the societies and beliefs of the Middle-Ages: you had the remnants of the Greco-Roman beliefs, especially the Plato philosophy, and you had all the leftovers of the Celtic and Germanic mythologies, mixed with all the apocalyptic imagery that was VERY popular at the time... And all this mixed together started shaping the Purgatory as we know it today.

For example, in the 8th century or so, in his Ecclesiastical History, Bede collected a story called "Drythelm's vision" (book V, chapter 12). The titular man, Drythelm, had what we would call today a Near-Death-Experience - he entered into a death-like state, then suddenly returned to life. Once "awake", he told of how he had been guided by a shinng person dressed in white to fantastical landscapes East of the world. At first, Drythelm saw a deep valley: one side was burning, the other covered by both a snowstorm and hailstorm, and a ceaseless wind pushed human souls from the burning fire to the freezing ice constantly. Drythelm thought he was in Hell, but his guide rather told him it was not Hell, but a place where the souls of those that were late in confessing their sins or trying to repair their crimes were "examined and punished" - but since before their death they ended up confessing their evils and making penitence, they all earned the right to join Heaven upon Judgement Day. After this sight, Drythelm goes over a high wall, and sees a green, flowery meadow, filled with lovely scents and bright light, where white-dressed people chat with each other. Drythelm thinks he is in Heaven, but the guide once again says no: rather, this place is the realm where the souls of those not perfect enough for Heaven are sent, but they too will earn their right to the "Celestial Kingdom" upon Judgement Day. As such, Drythelm vision doesn't offer a "third realm" between Heaven and Hell, but rather a binary system of temporary places, one of torment and one of waiting.

[I will make a pause here to explain something: The reason why Heaven seems so hard to reach in early Christian texts is actually quite simple. Heaven was not originally made for human souls. Maybe I'll explain this in more details when I'll make posts covering the evolution of Heaven but simply put: originally Heaven was supposed to be the realm of God and angels, and that's it. It was an inhuman realm for inhuman beings. Then, the Church did accept the idea that human souls could go to Heaven: but it was only Saints. Aka, not just any good human souls, but exceptional humans that had risen above their regular condition to become themselves part-divine. The idea that all good souls can go to Heaven is actually a "late" development in the concept of Heaven ; hence why in these early texts we have a lot of talks about how even good human souls are still not "perfect" enough to reach Heaven.]

Now, Drythelm was not a man of the Church - he was your regular guy, so to speak. As such, it is interesting to compare this vision to another "afterlife vision", called the "Wetti Vision", collected by Walafrid Strabon in the 9th century: Wetti being a monk, the vision is much more "religious". The monk Wetti claimed that one day, as he was sick and laying in his room, he saw Satan appear before him, in the shape of a black and ugly Churchman, surrounded by demon and torture-tools. However a group of monks came in to force the demons to flee, and a purple-clad angel suddenly appeared to comfort the sick monk. Awakening, Wetti asked for other monks of his monastery to pray for him, and he read some of the Dialogues of Gregory the Great, before going to sleep again. The angel returned, but this time clad in white, and took Wetti away on a pleasant road, towards high mountains made of marble and surrounded by a river - a river in which people are tormented and tortured, especially bad priests and the women they seduced. The angel then shows Wetti a version of Purgatory - here a twisted and crooked castle on the mountains, made of wood and stone, and where both monks and non-Churchmen have "purgative" torments inflicted upon them - Wetti notably sees here Charlemagne, punished for his sexual life. This text is very interesting because it clearly split Purgatory and Hell - explaining that the torments of Hell are endless and eternal, while those of Purgatory (the mountainous realm) are temporary.

Another vision that was influential is called the "Vision of Charles the Fat", which has in common with the Vision of Wetti to show historical figures of great rulers being tormented in the afterlife, showing even the "greats of this world" cannot escape a moral punishment. The Vision of Charles the Fat notably inspired Dante's own Divine Comedy - but we'll put the details for another time.

So, we have a boom of visions of the afterlife, and of records of strange dreams and NDE visits of "in-between" places that are neither Heaven no Hell. The theologians have to catch up, and to put an end to these endless discussions around unclear and vague doctrines full of holes. Two main questions are brought up: on one side, the "categorization of the souls", on the other, the "geography of the afterlife". To be clear: theologians wonder who can be redeemed, how they can be redeemed, and if Purgatory is truly separate from Hell. Saint Augustine had established a division of souls in four categories: 1) the all-good 2) the all-evil 3) the not-all-good (or "mostly-good") 4) the not-all-evil (or the "mostly evil"). However, theologians couldn't possibly make this four-part classification fit with the trinity that was arising of Heaven-Hell-Purgatory.

A commentator named the "Ambrosiaster" (or "Pseudo-Ambrose) had a HUGE impact on the medieval theologians of the 12th and 13th centuries, because in his study of the first epistle of saint Paul to the Corinthians, he clearly defined three fates after death. All the saints and the justs go to Heaven. All the infidels, all the atheists, all the impious ad apostates go to the "endless Gehenna". But the sinners that "had faith" will undergo trials before reaching Heaven. Under this light, the theologians of the 12th century decided to gather in one category the "not-all-good" and "not-all-evil" souls - those not good enough to go to Heaven and those not bad enough to go to Hell. They became one group known as the "mediocriter", the mediocre souls, and yet despite going to a same place (Purgatory) they had were prepared for a different fate.

The true foundational texts of the Purgatory date from between 1170 and 1200 - and the afterlife thoughts and theories they offer are actually a reflection of the social, political and judiciary evolutions of the time. Indeed, what happens during this era? The Pope's authority becomes much stronger and his power more direct. The feodal system starts crumbling down, replaced by great States. The bourgeoisie starts appearing as a third group between the peasants and the nobility ; the same way that a "third order" appears between churchmen and the secular people. The apocalyptic texts, which had been very influential until now, become secondary sources, while the Song of Songs is pushed forward. As such, the 12th century invites people to discover a restructured world and society, and to think about making justice evolve. People of the era were not satisfied anymore but the Heaven-Hell couple, thought as too simple and too binary. The idea of personal responsability eclipsed the "sins of the community", and it was around this era that judiciary concepts such as "parole", "conditional liberty" and "emission of sentence" were created. Theologians drew a line between the vices (the natural flaws and the evil pulsions within one's soul) and the sins (crimes and evil actions, but that could be done not out of evil intentions, but out of ignorance). It was also around this era that the division between the mortal sins (criminalia capitalia) and the venial sins (parva, quotidiana, minuta) was heavily stressed out - the new afterlife had to reflect the idea that some sins could be forgiven, others not.

In France, two intellectual communities truly theorized the Purgatory between the 12th and 13th centuries. On one side, you had the intellectual Parisian community - especially Notre-Dame, which was as much a cathedral as a school, before its "scholar" functions was moved to the University and the teachers of Franciscan and Dominican orders. Jacques Le Goff did identify the birth of modern Purgatory with the event known as the "scolastic spring", represented by the three Pierres : Pierre le Chantre, Pierre le Mangeur, Pierre Lombard. Pierre le Mangeur (Peter the Eater) was notably one of the first men in France to use the term "purgatorium". The second intellectual domain to build Purgatory was the Cistercian order, whose influence was so great many people consider saint Bernard to have "created" Purgatory - and it is known that the Cistercian order had many ties to the Parisian intellectuals.

To return to the three Pierres, Pierre Lombard in his Sentences explained there were three categories of souls, identical to the one we saw before: one group is of the entirely good and virtuous souls, another is the evil souls, and the third group gathers those that are almost entirely good, and those that are almost entirely bad. Pierre le Chantre rather explicitely describe three afterlife realms, a Heaven-Hell-Purgatory system (and he explicitely uses "purgatorium" to designate the third realm). If we move on to the 13th century, we find many more men talking about Purgatory: the great theologians that were Guillaume of Auverge, Bonaventure, Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas... But while they speak about it, they do not really focus much or think much of it. Albert the Great, for example, considers Purgatory to be a place located near Hell, and where venial sins can be redeemed. He considers Purgatory a "passage-area", through which souls are led and guided by demons that are unable to harm them. Unlike Hell, which is a place of punishment where souls are tortured by both freezing cold and burning heat, Purgatory is a place of purging and purification leading to heavenly bliss - and this can only be done by fire, but a benevolent and non-harmful fire.

It was around the same time that the concept of "Limbo" appeared, as a place where the souls of unbaptized children went - and with the rise of Purgatory and Limbo, the old concepts of the Bosom of Abraham and of the refrigerium were completely erased and buried. The Purgatory became the embodiment of the "Suffering Church" Innocent III created. [To be clear: Sant Augustine established a division between Celestial Church and the Peregrine Church. This duality evolved in the 12th century into the Militant Church and the Triumphing Church, but the concept stayed the same. There is one side of the Church found on Earth, made by all the living agents of God, and the men and women of the Church, and the active Christians ; and another that is in Heaven, and is made of all the saints, and all the blessed ones living with God and His angels, and all the deceased Christians in the celestial realm. From Innocent III onward, the Christians located in Purgatory became the "third" side of the Church - the Suffering Church, or Penitent Church.]

In conclusion: all the great religious authorities, theologians and Christianity scholars agreed on the existence of Purgatory as a third place and spread the belief in it. But they still left its location and its details blurry, untold or open for imagination - placing the Purgatory as more of a secondary detail or general background in the great Christanity cosmogony. For them, recognizing that it exists was already enough: no need to waste too much time thinking about it, all you need to know is that it is there.

But despite the theologians and scholars' silence about Purgatory, the people became VERY interest with the idea of Purgatory, if not completely enamored with it. The idea of a "third realm", of a "second chance" became a HUGE thing - and as such, many, many secular or non-religious works started heavily expanding the "Purgatory lore".

Given this post is a bit too long, I'll stop here - to offer more next time...

#hazbin hotel#purgatory#christian beliefs#christianity#christian mythology#history of christianity#hell#heaven#afterlife#realms of the afterlife#christian afterlife

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#medieval#history#books#history of science#history of magic#history of christianity#counter reformation

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sympathy for the Grinch

I've not celebrated Christmas with another person since 2006 (? -ish?). And with each passing year, I miss it less and less.

And the more I learn about the origins of Christmas traditions, the more I see how much antisemitism is baked into the formation of Christianity as a separate religion, and that tarnishes the tinsel, so to speak.

I'm still here for celebrating for celebration's sake. But I cannot completely separate the cultural iconography of Christmas with Christian theology, and that makes it less fun.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#christianity#things Christians lied about#satan#Lucifer#religion#interesting#history of Christianity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First and Second Crusades

The First and Second Crusades from an Anonymous Syriac Chronicle

The First and Second Crusades are significant events in the history of Christianity, as well as in the history of the Middle East. This paper will provide an in-depth analysis of the First and Second Crusades from an anonymous Syriac chronicle. The source for this analysis is a 1933 edition of the Journal of the Asiatic Society, which was edited by A.S. Tritton and H.A.R. Gibb.

The First Crusade began in 1095 when Pope Urban II called on Christians to take up arms against the Muslims in the Holy Land. The goal of the crusade was to retake Jerusalem, which had been under Muslim control since 638. The success of the First Crusade was largely due to the leadership of Godfrey of Bouillon, who led the Christian forces to victory in 1099.

The Second Crusade was launched in 1147 and was intended to recapture Edessa, which had been lost to the Muslims in 1144. Unlike the First Crusade, the Second Crusade was unsuccessful and ended in failure. The anonymous Syriac chronicle provides insight into the motivations behind the crusades, as well as the reactions of the people of the Middle East to the arrival of the Christian forces.

The anonymous Syriac chronicle paints a vivid picture of the First and Second Crusades. It describes the motivations of the Christian forces, as well as their tactics and strategies. It also provides insight into the reaction of the people of the Middle East to the arrival of the Christian forces. According to the chronicle, the people of the Middle East were initially fearful of the Christian forces, but eventually came to accept them.

The anonymous Syriac chronicle also provides insight into the religious differences between the Christian and Muslim forces. It describes how the two sides viewed each other and how they interacted with each other during the course of the crusades. For example, it notes that the Muslims were often surprised by the Christians’ willingness to fight and die for their faith.

Finally, the anonymous Syriac chronicle provides insight into the long-term effects of the First and Second Crusades. It notes that the crusades had a lasting impact on the region, both politically and culturally. It also suggests that the crusades helped to create a more unified sense of identity among the people of the Middle East, as they came to see themselves as part of a larger community.

To summarize, the anonymous Syriac chronicle provides an invaluable source of information on the First and Second Crusades. It offers insight into the motivations of the Christian forces, the reactions of the people of the Middle East, the religious differences between the two sides, and the long-term effects of the crusades. This source is an important piece of evidence for anyone attempting to gain a better understanding of the First and Second Crusades.

Works Cited

Tritton, A.S., and H.A.R. Gibb. “The First and Second Crusades from an Anonymous Syriac Chronicle (1933).” Journal of the Asiatic Society, vol. 65, pp. 69–101 and 274–305, 1933.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I understand why a lot of fantasy settings with Ambiguously Catholic organised religions go the old "the Church officially forbids magic while practising it in secret in order to monopolise its power" route, but it's almost a shame because the reality of the situation was much funnier.

Like, yes, a lot of Catholic clergy during the Middle Ages did practice magic in secret, but they weren't keeping it secret as some sort of sinister top-down conspiracy to deny magic to the Common People: they were mostly keeping it secret from their own superiors. It wasn't one of those "well, it's okay when we do it" deals: the Church very much did not want its local priests doing wizard shit. We have official records of local priests being disciplined for getting caught doing wizard shit. And the preponderance of evidence is that most of them would take their lumps, promise to stop doing wizard shit, then go right back to doing wizard shit.

It turns out that if you give a bunch of dudes education, literacy, and a lot of time on their hands, some non-zero percentage of them are going to decide to be wizards, no matter how hard you try to stop them from being wizards.

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lessons from Lewis's "Learning in War-Time"

I recently re-encountered C.S. Lewis’s sermon on learning in war time, which he delivered to undergraduates at Oxford in the autumn of 1939. From my notes, it seems I first read this essay some ten years ago, so I figured it would be worth a re-read. The following are some reflections from my read through. Any quest for knowledge is necessarily partial. We will never reach the end of knowing in…

#C.S. Lewis#Christianity and Culture#Crisis#Critical Thinking#Education#Essays#History of Christianity#Learning#Lessons#Reflections#War

0 notes

Text

Christianity: How Its Teachings Shaped Culture, Politics, and History

Introduction Religion has been an integral part of human history, influencing societies since the earliest cave paintings, which show signs of spiritual awareness. Among the world’s major religions, Christianity has had a profound impact on culture, politics, and government throughout history. In today’s United States, religion continues to play a divisive role in politics, with the media often…

#Catholicism#Christian history#Christianity#church power#conservative Christians#Crusades#history of Christianity#Jesus and politics#Jesus’ teachings#Orthodoxy#politics#progressive liberals#religion in the USA#religious division

0 notes

Text

tiddles the church cat

#christian cats#christian blog#graveyard#gravestone#cemetery#cat history#cat art#headstone#grave#church aesthetic#church#cathedral#church cat

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

The nazis that you see in movies are as much a historical fantasy as vikings with horned helmets and samurai cutting people in half.

The nazis were not some vague evil that wanted to hurt people for the sake of hurting them. They had specific goals which furthered a far right agenda, and they wanted to do harm to very specific groups, (largely slavs, jews, Romani, queer people, communists/leftists, and disabled people.)

The nazis didn't use soldiers in creepy gas masks as their main imagery that they sold to the german people, they used blond haired blue eyed families. Nor did they stand up on podiums saying that would wage an endless and brutal war, they gave speeches about protecting white Christian society from degenerates just like how conservatives do today.

Nazis weren't atheists or pagans. They were deeply Christian and Christianity was part of their ideology just like it is for modern conservatives. They spoke at lengths about defending their Christian nation from godless leftism. The ones who hated the catholic church hated it for protestant reasons. Nazi occultism was fringe within the party and never expected to become mainstream, and those occultists were still Christian, none of them ever claimed to be Satanists or Asatru.

Nazis were also not queer or disabled. They killed those groups, before they had a chance to kill almost anyone else actually. Despite the amount of disabled nazis or queer/queer coded nazis you'll see in movies and on TV, in reality they were very cishet and very able bodied. There was one high ranking nazi early on who was gay and the other nazis killed him for that. Saying the nazis were gay or disabled makes about as much sense as saying they were Jewish.

The nazis weren't mentally ill. As previously mentioned they hated disabled people, and this unquestionably included anyone neurodivergent. When the surviving nazi war criminals were given psychological tests after the war, they were shown to be some of the most neurotypical people out there.

The nazis weren't socialists. Full stop. They hated socialists. They got elected on hating socialists. They killed socialists. Hating all forms of lefitsm was a big part of their ideology, and especially a big part of how they sold themselves.

The nazis were not the supervillians you see on screen, not because they didn't do horrible things in real life, they most certainly did, but because they weren't that vague apolitical evil that exists for white American action heros to fight. They did horrible things because they had a right wing authoritarian political ideology, an ideology that is fundamentally the same as what most of the modern right wing believes.

#196#my thougts#leftist#leftism#jewish#jumblr#actually mentally ill#mental illness#neurodivergent#actually neurodivergent#world war 2#world war ii#history#queer#gay#queer history#pagan#athiest#athiesm#disability rights#communist#communism#socialist#socialism#anti conservative#anti christianity#christanity#christianity#mad pride#madpunk

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lets talk about Purgatory... (2)

Last time, we talked about how the belief in the existence of a Purgatory, as a third realm between heaven and hell, slowly came into existence and was ultimately accepted by the Church - but it stayed a vague, undefined realm with very little canonical or official statements about it. And we were about to see how what actually TRULY helped Purgatory grow and develop itself was popular imagination, non-religious texts and other forms of art...

As a reminder, I am still following so far for these posts an article that was written by Christine Duthoit about the beliefs in the afterlife during the Middle-Ages.

So, as we said, the fact that theologians were very vague, uncertain and brief whenever they spoke of Purgatory was a true obstacle for many artists of the time who wishe to depict this realm, and it didn't help that in the many afterlife visions they had to take inspiration from, Purgatory and Hell were clearly confused with each other, or looking extremely similar. Take the vision of Charles the Fat, in the ninth century (I briefly referenced it in the previous post). In this vision, Charles was guided by a being dressed in white, and holding a sort of shining ball emitting a strong ray of light. The guide took Charles into what is described as a "maze of hellish torments": he saw great and deep valleys of fire filled with wells in which were burning sulfur, lead, wax, soot and pitch. And in this place, souls were tortured inside boiling rivers and boling swamps ; as well as within "furnaces of pitch and sulfur, filled with great dragons, scorpions and snakes of many different species". Is it Purgatory or Hell? Hard to say. Saint Augustine was also considered to have been one of the main Christian voices behind the "infernalization" of Purgatory. And, just like with Hell, the dominating element of Purgatory is fire: descriptions are filled with fire-rings, fire-circles, fire lakes, seas of fires, walls of fire, burning valleys, hot coals, mountains of flames... However, unlike the fire of Hell which is only suffering and pain, the fire of Purgatory is meant to be purifying: it notably makes one look younger, and offers a form of immortality. This association of Purgatory with fire explains why many thought the volcanic regions were gateways to Purgatory - the Etna in Sicily, or the islands Lipari, were believed to host Purgatory. And of course, there is "Saint Patrick's well" in Ireland...

In the 12th century, four "visions of the afterlife" dominated the European beliefs and culture. Three of them are only evoked in the article but not described in details: the vison of the mother of Guibert of Nogent ; the vision of Tnugdal ; the vision of Alberic of Settefrati... As for the fourth, it is the one collected in the medieval best-seller that was The Purgatory of saint Patrick, written between 1190 and 1210. In this tale, a Cistercian monk of England named Gilbert is sent alongside a knight named Owein to build a monastery in Ireland. The story describes how the future saint Patrick, who was in the middle of Christianizing Ireland, was showed by Jesus a well... Not just any well. A round, dark and deep well located in the Red Lake (Donegal), on Station Island ; and Jesus told saint Patrick that any Christian that would spend a day and a night in this hole would be purged of all their sins - and they would also be able to see the suffering of the wicked and the joy of the virtuous. Saint Patrick had a church built nearby, and a great wall erected around the well, trusting the key of the door's wall to an abbot (mentions of this geography are found in the maps of Topography of Ireland by Giraud the Welsh). Owein, the knight, decides to go down the well, despite him having quite a handful of sins weighing his souls, and despite the warning of the churchmen that guard the well. As soon as he gets down into the hole, he is harassed by numerous demons, and forced to walk in a mix of pure darkness and red lights, filled with tormented screams and fetid smells. The red lights come from the flames of a pace that looks like Hell - and is inhabited by dragons, snakes and toads that constantly torment the souls there. Owein sees people being crucified with red-hot nails, being tied up to fiery wheels, being roasted or hanged by iron-hooks, he even sees people being plunged in huge vats of molten metal... Owein manages to face all the horrors and trials of what he beleves is Hell, by constantly invoking the name of Jesus to protect him. He ends up arriving in what seems to be Earthly Paradise, and is there welcomed by two archbishops... Who reveal to him it wasn't Hell at the bottom of the well. But Purgatory, explicitely referred to as the "third realm" of the afterlife, and where the souls of the sinners complete their repentance and purification. Once the souls of Purgatory are done with their torments, they will reach the Earthly Paradise, and then finally move on to the celestial Heaven. The knight returns to the top of the well, and upon reaching back the world of the living is glad to learn he has been purified of all of his sins.

This story became MASSIVELY popular in medieval Europe - notably because it confirmed what many people wanted to believe into, the idea that the justs and good people had a chance to completely and utterly purify themselves before reaching Heaven. By extension, it meant there were indeed various types and categories of sins, and that not all crimes were as bad - with some sins being forgivable and not preventing one's reach of Heaven...

Another key feature to understand the "creation" of Purgatory in the Christian world is the idea that the dead and the living are somehow tied to each other.

The article begins by the "communion of the saints". This belief did not originate in any actual council or official Church decision - rather, in France, it spontaneously appeared at the end of the 4th century among the Christian communities. The saints weren't just protecting and watching over the living anymore ; now, they formed a bridge and a link between the living and the dead. Most importantly, the sufferings and pains of the dead in the afterlife could be eased or shortened by the prayers of the living - through the saint, that received the prayer, and then influenced the fate of the deceased. (In France we call those interventions for the dead caused by the living's prayers "suffrages").

The apparition of the idea that the prayers of the living influenced the afterlife was part of a wider movement in Christianity that focused more and more about the dead. Take the apparition of All Hallows Day, or All Saints Day. It was created in 610 by Boniface IV, and it was originally the day of the martys - and solely the martyrs. But then it became the day to celebrate all of the saints, martyrs or not martyrs - and Gregory the IV insisted on this day being celebrated by all Christians, showing the importance it grew. In parallel, we know that as early as Gregory the Great's time, masses and religious celebrations included a "Mementa", a part to remember the dead. This expanded into the monks creating "Libri Vitae", to register all the livings and the dead that were named during a mass ; and soon necrologies and obituaries were formed, lists and registers of the deads, their names, the day they died, and their "obit", the anniversary of their deaths. And between 1024 and 1033, a Day of the Dead was created to honor and commemorate all the dead Christians... And it was placed on the second day of November, that is to say the day following All Hallows Day/All Saints Day, further strengthening the bond between the Saints and the Afterlife.

As new conceptions of sin and penitence appeared, as the confession became one of the most important rituals in the life of the Christians, stories and testimonies of deceased coming back to visit the living (usually souls from Purgatory) started multiplying. You had dead people visiting their family to demand their prayers and their memory in the afterlife ; you had dead churchmen or churchwomen informing the people of their order of what happened to them in the afterlife ; mystics and saints kept being visited by ghosts and revenants left and rights. This was a good bulk of the story of hauntings in the Middle-Ages. A greater focus was put on the idea that a Christian had to absolutely purify themselves when alive to avoid the torments of the afterlife - notably through contrition, confession and penitence. The pope Innocent III had a very cynical take on the mental beliefs and evolutions of his time, pointing out that the living only cared for the dead, because they themselves were future dead. Aka, this obsession with Purgatory and ghosts and praying for the dead was simply the other side of the coin of the fear of mortality, and the terror of the trials awaiting beyond.

In the middle of the 13th century, when it came to Churchmen that took care of the fidels and shared their daily life, the Cistercians were replaced by the Mendicant orders, the "begging monks", who were especially popular/influental in urban areas. One of the specific traits was a heavy use of "exempla" during their preach: the "exemplum" is, as the name indicates, an example, the illustration of an affirmation or claim, taking the shape of a small story. It ranges from the parable to the fable, passing by actual ancestors of what we know today as "fairytales". And it is within these exempla that the legend of Purgatory ended up being built (a good example of the results of this "exampla-fashion" is the Golden Legend, La Légende Dorée of Jacques of Voragine).

A man the article speaks heavily about is the Dominican named Thomas of Cantimpré. He was a general-preacher for a monastical province that covered a part of Germany, a part of Belgium and a part of France. After spending thirty years preaching and teaching Christianity, he collected an enormous amount of exempla in his "Livre des abeilles", The Book of bees - and this collection testifies the strong anguish and terror Christians felt at the time when it came to death and the afterlife. They also record how comforting and beloved the idea of the "suffrages", of the power of the living over the fate of the dead, was. Thomas of Cantimpré notably classified six types of "suffrages" that could ease the pain or shorten the torment of the souls in Purgatory: tears (crying for the dead), the wakes (watching over the deceased), fasting (respecting a funeral fast), alms (aka giving money to someone who will think about/pray for the dead), the "sacrifice of the mass" (aka having a funeral mass for the dead), and giving back money (aka, either paying the debts of the deceased, either restituting goods or wealth that the dead stole). This belief was certainly influenced by how Thomas of Cantimpré wrote an official biography of saint Lutgarde of Tongres, a cistercienne nun who devoted her entire life to the souls of the Purgatory, constantly praying and fasting for them.

The article offers a selection of the Purgatory-exempla that Thomas of Cantimpré wrote down.

A) A very sick man prays God so he can be set free from his ill body by death. An angel appears and offers him a choice: either be sick for a whole year and go directly to Heaven, or die now and spend three days in Purgatory. The sick man says he prefers dying now and suffering Purgatory: he dies and finds himself in the middle of cruel torments. After one year of torture, the angel comes back to him and asks him "Do you think you made the right choice?". As the soul of the dead complains about his situation, the angel reveals to him this one year... was actually one day in Purgatory. The dead man eventually agrees to take the other option - he is sent back into his sick body, and suffers his illness for one more year before going to Heaven.

B) A wealthy and powerful duke decides to convert himself to Christianity. He stops spending too much, he is very charitable to the poors of his domain, he has chapels built to celebrate masses "in honor of the souls suffering in Purgatory". The devil, angry at this, causes a rebellion and uprising among the duke's vassals. They accuse their lord of believing imaginary stories, of spending his money in a "dishonorable" way, and to not care about the noble serving under him anymore, giving all his wealth to the dead rather than the livng. This becomes a civil war, but the battle is ultimately won by the duke because he is helped by a celestial army coming down from Heaven - and made by all the souls that could escape Purgatory thanks to the duke's alms and masses.

The "officialization" of Purgatory only appears with the second Council of Lyon, organized in 1274: it is then that the Purgatory became an official belief of the Christian Church. The Purgatory is seen as an extension or substitution to the earthly penitence of the living. It is stated that the duration of a stay in Purgatory depends from person to person - but that it does not have to cover all of the span between someone's death and the resurrection at the end of times (aka, a Purgatory soul can reach Heaven before Judgement Day). Starting from this Council onward, theologians started making complex and fascinating calculations in order to determine how long exactly a soul has to stay in Purgatory, depending on the quantity and gravity of the person's sins.

And with any religous process that involves the metaphysical equivalent of math tests... cheating arrived. In the form of "indulgences". For those of you not familiar with this, the system of indulgences within the Christian Church (Catholic branch) is, as the name says, a system of "pardons" and "leniences" - it is when a Catholic religious authority deserves a form of "pardon" for the sins of a specific person. At first it was another way for living Christians to purify themselves before their death - and it quickly became one of the most famous corruptions of the Church, denounced as much by Protestants as by poets such as Dante. Sinners just had to "buy" an indulgence by giving enough money to a religious authority, and they were cleansed of their crimes in the eyes of the Church - even if they made no effort to redeem themselves, underwent no penitence or did not express any regret. But by the hubilee of the Church in 1300, the Pope Boniface VIII extended the indulgences to the souls of Purgatory - which by the time had become a full part of the Christian art and Christian rituals.

And when Protestantism arose, the Catholic Church held tightly onto the belief in Purgatory: in the 16th century, the Council of Trente confirmed once more that Purgatory was part of their canon and dogma, to better differentiate Catholics from Protestants.

Fascinatingly however, it was not the first time Purgatory served a political purpose... Long before Protestanism appeared, Purgatory had been used as a tool against all those seen as dissidents groups within the Church - aka, heretics. In France, the two most famous heresies of the Middle-Ages firmly rejected Purgatory as a whole. One was the one we called the "vaudois", part of the Vaudois movement (also called Valdeism or Valdism). They held the belief that faith was a gift from God, and that by extension only the Christ could intercede. As in, only prayers to the Christ had any power to change the fate of people or could be able to reach God - by extension, they considered that the saints were powerless, and the indulgences worth nothing. Recognizing only two sacraments as "real", the Baptism and the Eucharist, they considered Purgatory to be a pure fiction, a made-up fairytale with no real existence: for them, there is only Heaven or Hell.

The other group were, of course, the Cathars, who believed that material world was inherently evil and that humans were fallen angels trapped in bodies of flesh. They only recognized one sacrament, the "consolamentum", the only ritual that can grant salvation by setting free the divine part of the human: the spirit returned to God, leaving behind its material body and the evil within it. This ritual, called a "baptism of spirit and fire" was a cross between the "last rites" for the dead (as it was the final ritual ensuring salvation after death), and an ordination, as it was the only ritual needed to become fully and "truly" Christian. Hence why the Cathars called themselves the Perfects, the Good Men or the Good Women (they also heavily used the Gospel of John, which fitted the most their beliefs). As a result of all this - for them death, like with the vaudois, could only lead to Hell (being trapped in the material world) or Heaven (becoming a pure spirit with God) - no in-between was possible.

A third group deemed as heretical by the Church that also rejected Purgatory were the Brothers and Sisters of the Free-Spirit, the Libre-Esprit movement, who preached and swore only by poverty. For them, it was poverty that set a man free of his sins and "resurrected the Christ within him". Long story short: as long as you were poor, you could listen to your every desires and follow your every whims without fearing a sin. This was the teaching of the "free-spirit": you could obtain paradise by simply living on earth, as long as you were poor, since poverty annihilated all sins. In their own words, a poor whore was worth more than a pious and just rich man - and in turn, this allowed them to declare all Churchmen were damned (denouncing how the Church had become one the wealthiest institutions of the Middle-Ages).

This is all I can take from the article - and unfortunately it is quite limited, since the text is about Purgatory in the Middle-Ages, and so it does not expand to modern days... But I hope it was interesting eough as a quick overview! If I find more sources, I'll continue this series.

#purgatory#christianity#christian mythology#christian afterlife#history of christianity#heresies#heresy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tapestry of History, 14 – The Rise of the West, 9 – Enlightenment, 1

Though the Enlightenment, as a diverse intellectual and social movement, has no definite end, the devolution of the French Revolution into the Terror in the 1790s, corresponding, as it roughly does, with the end of the eighteenth century and the rise of opposed movements, such as Romanticism, can serve as a convenient marker of the end of the Enlightenment, conceived as an historical…

#Colonialism#Enlightenment#Enlightenment Thinkers#History of Christianity#History of the West#Philosophes#Scientific Revolution

0 notes

Text

When Christianity Became the Empire: A Reflection on Faith, Power, and Deception

Throughout history, the story of Christianity has been one of profound transformation. From its humble beginnings as a faith centered on the teachings of Jesus—a man who preached love, forgiveness, and non-violence—Christianity evolved into a powerful institution, closely tied to the machinery of empire. This evolution raises important questions about the nature of faith, power, and the dangers…

#biblical warnings#Christ’s message#Christian deception#Christian ethics#Christian history#Christian pacifism#Christian theology#christianity#church and state#church history#Constantine#early Christians#faith and power#false prophets#history of Christianity#Jesus teachings#non-violence in Christianity#Roman Empire#spiritual reflection#state religion

0 notes

Video

youtube

History of Christianity || The Ancient Church || Documentary

0 notes

Text

So I’ve been enjoying the Disney vs. DeSantis memes as much as anyone, but like. I do feel like a lot of people who had normal childhoods are missing some context to all this.

I was raised in the Bible Belt in a fairly fundie environment. My parents were reasonably cool about some things, compared to the rest of my family, but they certainly had their issues. But they did let me watch Disney movies, which turned out to be a point of major contention between them and my other relatives.

See, I think some people think this weird fight between Disney and fundies is new. It is very not new. I know that Disney’s attempts at inclusion in their media have been the source of a lot of mockery, but what a lot of people don’t understand is that as far as actual company policy goes, Disney has actually been an industry leader for queer rights. They’ve had policies assuring equal healthcare and partner benefits for queer employees since the early 90s.

I’m not sure how many people reading this right now remember the early 90s, but that was very much not industry standard. It was a big deal when Disney announced that non-married queer partners would be getting the same benefits as the married heterosexual ones.

Like — it went further than just saying that any unmarried partners would be eligible for spousal benefits. It straight-up said that non-same-sex partners would still need to be married to receive spousal benefits, but because same-sex partners couldn’t do that, proof that they lived together as an established couple would be enough.

In other words, it put long-term same-sex partners on a higher level than opposite-sex partners who just weren’t married yet. It put them on the exact same level as heterosexual married partners.

They weren’t the first company ever to do this, but they were super early. And they were certainly the first mainstream “family-friendly” company to do it.

Conservatives lost their damn minds.

Protests, boycotts, sermons, the whole nine yards. I can’t tell you how many books about the evils of Disney my grandmother tried to get my parents to read when I was a kid.

When we later moved to Florida, I realized just how many queer people work at Disney — because historically speaking, it’s been a company that has guaranteed them safety, non-discrimination, and equal rights. That’s when I became aware of their unofficial “Gay Days” and how Christians would show up from all over the country to protest them every year. Apparently my grandmother had been upset about these days for years, but my parents had just kind of ignored her.

Out of curiosity, I ended up reading one of the books my grandmother kept leaving at our house. And friends — it’s amazing how similar that (terrible, poorly written) rhetoric was to what people are saying these days. Disney hires gay pedophiles who want to abuse your children. Disney is trying to normalize Satanism in our beautiful, Christian America.

Just tons of conspiracy theories in there that ranged from “a few bad things happened that weren’t actually Disney’s fault, but they did happen” to “Pocahontas is an evil movie, not because it distorts history and misrepresents indigenous life, but because it might teach children respect for nature. Which, as we all know, would cause them all to become Wiccans who believe in climate change.”

Like — please, take it from someone who knows. This weird fight between fundies and Disney is not new. This is not Disney’s first (gay) rodeo. These people have always believed that Disney is full of evil gays who are trying to groom and sexually abuse children.

The main difference now is that these beliefs are becoming mainstream. It’s not just conservative pastors who are talking about this. It’s not just church groups showing up to boycott Gay Day. Disney is starting to (reluctantly) say the quiet part out loud, and so are the Republicans. Disney is publicly supporting queer rights and announcing company-supported queer events and the Republican Party is publicly calling them pedophiles and enacting politically driven revenge.

This is important, because while this fight has always been important in the history of queer rights, it is now being magnified. The precedent that a fight like this could set is staggering. For better or for worse, we live in a corporation-driven country. I don’t like it any more than you do, and I’m not about to defend most of Disney’s business practices. But we do live in a nation where rights are largely tied to corporate approval, and the fact that we might be entering an age where even the most powerful corporations in the country are being banned from speaking out in favor of rights for marginalized people… that’s genuinely scary.

Like… I’ll just ask you this. Where do you think we’d be now, in 2023, if Disney had been prevented from promising its employees equal benefits in 1994? That was almost thirty years ago, and look how far things have come. When I looked up news articles for this post from that era, even then journalists, activists, and fundie church leaders were all talking about how a company of Disney’s prominence throwing their weight behind this movement could lead to the normalization of equal protections in this country.

The idea of it scared and thrilled people in equal parts even then. It still scares and thrills them now.

I keep seeing people say “I need them both to lose!” and I get it, I do. Disney has for sure done a lot of shit over the years. But I am begging you as a queer exvangelical to understand that no. You need Disney to win. You need Disney to wipe the fucking floor with these people.

Right now, this isn’t just a fight between a giant corporation and Ron DeSantis. This is a fight about the right of corporations to support marginalized groups. It’s a fight that ensures that companies like Disney still can offer benefits that a discriminatory government does not provide. It ensures that businesses much smaller than Disney can support activism.

Hell, it ensures that you can support activism.

The fight between weird Christian conspiracy theorists and Disney is not new, because the fight to prevent any tiny victory for marginalized groups is not new. The fight against the normalization of othered groups is not new.

That’s what they’re most afraid of. That each incremental victory will start to make marginalized groups feel safer, that each incremental victory will start to turn the tide of public opinion, that each incremental victory will eventually lead to sweeping law reform.

They’re afraid that they won’t be able to legally discriminate against us anymore.

So guys! Please. This fight, while hilarious, is also so fucking important. I am begging you to understand how old this fight is. These people always play the long game. They did it with Roe and they’re doing it with Disney.

We have! To keep! Pushing back!

#disney#ron desantis#gay rights#lgbt#queer#lgbt history#queer history#homophobia#florida#us politics#religious fundamentalism#christianity#long post#god that should cover all the pertinent tags and content warnings phew

52K notes

·

View notes