#militant history

Text

Marina Ginesta, a 17-year-old communist militant during the Spanish Civil War. Hotel Colón in Barcelona, Spain. 1936

Source

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ribu's anti-imperialist feminist discourse would later manifest in its solidarity protests against kisaeng tourism. This sex tourism involved Japanese businessmen traveling to South Korea to partake in the sexual services of young South Korean women who worked at clubs called kisaengs. Ribu's protests against kisaeng tourism represented how the liberation of sex combined with ribu's anti-imperialism and enabled new kinds of transnational feminist solidarity based on a concept of women's sexual exploitation and sexual oppression. From ribu's perspective, this form of tourism represented the reformation of Japanese economic imperialism in Asia. They were not against sex work by Japanese women, but opposed to the continued sexual exploitation of Korean women as a resurgence of the gendered violence of imperialism: Ribu activists hence connected imperialism and sexual oppression of colonized women to the continuing sexual exploitation of Korean women in the 1970s. In this way, they were able to expand the leftist critique of imperialism and, at the same time, point to the fault lines and inadequacies of the left.

In her critique of the left, Tanaka points to its failure to have a theory of the sexes.

Even in movements that are aiming towards human liberation, by not having a theory of struggle that includes the relation between the sexes. the struggle becomes thoroughly masculinist and male-centered (dansei-chushin shugi].

According to ribu activists, this male-centered condition infected not only the theory of the revolution and delimited its horizon, but it created a gendered concept of revolution that privileged masculinist hierarchies within the culture of the left. Ribu activists decried the hypocrisy of the left and what it deemed to be the all-too-frequent egotistical posturing of the "radical men" who "eloquently talked about solidarity, the inter national proletariat and unified will," but did not really consider women part of human liberation. Ribu activists rebelled against Marxist dogma and rejected these gendered hierarchies that valued knowledge of the proper revolutionary theory over lived experience and relationships. Moreover, ribu activists criticized what they experienced as masculinist forms of militancy that privileged participation in street battles with the riot police as the ultimate sign of an authentic revolutionary. While being trained to use weapons, activists like Mori Setsuko questioned whether engaging in such bodily violence was the way to make revolution. Ribu's rejection and criticism of a hierarchy that privileged violent confrontation forewarned of the impending self-destruction within the New Left.

...

News of URA [United Red Army] lynchings, released in 1972, devastated the reputation of the New Left in Japan, and many across the left condemned these actions. This case of internalized violence within the left marked its demise. Although ribu activists were likewise horrified by such violence expressed against comrades, many ribu activists responded in a profoundly radical manner that I have theorized elsewhere as "critical solidarity." Ribu activists had already refused to lionize the tactics of violence; hence, they in no way supported the violent internal actions of the URA. However, rather than simply condemning the URA leaders and comrades as monsters and nonhumans [hi-ningen), they sought to comprehend the root of the problem. They recognized that every person possesses a capacity for violence, but that society prohibits women from expressing their violent potential. In response to the state's gendered criminalization of Nagata as an insurgent and violent woman, ribu activists practiced what I describe as feminist critical solidarity specifically for the women of the URA. Ribu activists went in support to the court hearings and wrote about their experience and critical observations of how URA members were being treated. By visiting the URA women at the detention centers, consequently, ribu activists came under police surveillance. Ribu activists enacted solidarity in ways that were tot politically pragmatic but instead philosophically motivated. Their response involved a capacity for radical self-recognition in the loathsome actions of the other. Activists wrote extensively about Nagata - for example, Tanaka described Nagata in her book Inochi no onna-tachi e [To Women with Spirit] as a kind of "ordinary" woman whom she could have admired, except for the tragedy of the lynching incidents. In 1973, Tanaka wrote a pamphlet titled "Your Short Cut Suits You, Nagata!" in response to the state's gendered criminalization of the URA's female leader, the deliberate publication of such humanizing discourse evinces ribu's efforts to express solidarity with the women who were arguably the most vilified females of their time. Hence, ribu engaged in actions that supported these criminalized others even when the URA'S misguided pursuit of revolution resulted in the unnecessary deaths of their own comrades. Through ribu's critical solidarity with the URA, they modeled the imperative of imperfect radical alliances, opening up a philosophically motivated relationality with abject subjects and a new horizon of counter-hegemonic alliances against the dominant logic of heteropatriarchal capitalist imperialism.

While the harsh criticism of the left was warranted and urgently needed given the deep sedimentation of pervasive forms of sexist practice, it should be noted that, at the outset of the movement, there were various ways in which ribu's intimate relationship with other leftist formations characterized its emergence. At ribu's first public protest, which was part of the October 21 anti-war day, some women carried bamboo poles and wooden staves as they marched in the street, jostling with the police." Ribu did not advocate pacifism; its newspapers regularly printed articles on topics such as "How to Punch a Man." During ribu protests from 1970-2, some ribu activists-as noted, with Yonezu and Mori - still wore helmets that were markers of one's political sect and a common student movement practice."

- Setsu Shigematsu, “'68 and the Japanese Women’s Liberation Movement,” in Gavin Walker, ed., The Red Years: Theory, Politics and Aesthetics in the Japanese ‘68. London and New York: Verso, 2020. p. 89-90, 91-92

#setsu shigematsu#ribu#revolutionary feminism#feminist history#patriarchal violence#heteropatriarchy#social justice#history of social justice#militant action#far left#new left#1968#japanese 68#japanese history#left history#academic quote#reading 2023#critical solidarity#united red army#anti-imperialism#sex tourism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

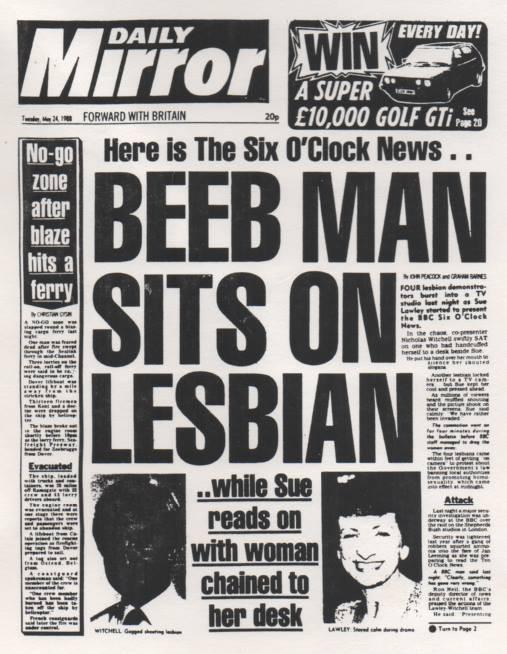

Militant Lesbian Invasion!

Militant lesbians, protesting Clause 28, invade the BBC newsroom

23rd May 1988

Gay men attempting to gain admission to protest at various times were, of course, roughly expelled/blocked.

Sue Lawley struggled on with the news, whilst Nicholas Witchell sat on one of the protesters.

Sue said: "... I do apologise if you're hearing quite a lot of noise in the studio at the moment. I'm afraid that, um, we have been rather invaded by some people who we hope to be removing shortly."

#militant lesbians#sue lawley#nicholas witchell#bbc news#protest#demonstration#section 28#clause 28#outrage#queer nation#act up#activism#activists#queer history#book ban#book bans#homophobia#queer#lgbqti#lgbt#lgbtq#trans#gay#lesbian#1980s#80s#1988

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing Red: Federal Campaigns Against Black Militancy, 1919-1925

Seeing Red: Federal Campaigns Against Black Militancy, 1919-1925

A gripping, painstakingly documented account of a neglected chapter in the history of American political intelligence.

"Kornweibel is an adept storyteller who admits he is drawn to the role of the historian-as-detective....What emerges is a fascinating tale of secret federal agents, many of them blacks, who were willing to take advantage of the color of their skin to spy upon others of their race.

And it is a tale of sometimes desperate and frequently angry government officials, including J. Edgar Hoover, who were willing to go to great lengths to try to stop what they perceived as threats to continued white supremacy." ―Patrick S. Washburn, Journalism History

#Seeing Red: Federal Campaigns Against Black Militancy#1919-1925#Black Militancy in the 1920's#Black Lives Matter#Black History#THE BLACK TRUEBRARY

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

But with your help,

#not all presbyterian ministers were telling their congregations they had to become militant republicans#and start piking things in the eighteenth century but with your help we can change that in the twenty first ☝️#reading#irish history#jory.txt

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#antisemitism#free palestine#free gaza#palestine#islamophobia#islam#islamic history#militant islam#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I ask this every month or two but what have you been reading lately?

•True West: Sam Shepard's Life, Work, and Times (BOOK | AUDIO | KINDLE) by Robert Greenfield

•The Oswalds: An Untold Account of Marina and Lee (BOOK | AUDIO | KINDLE) by Paul R. Gregory

•Wahhabism: The History of a Militant Islamic Movement (BOOK | KINDLE) by Cole M. Bunzel

•The Madman in the White House: Sigmund Freud, Ambassador Bullitt, and the Lost Psychobiography of Woodrow Wilson (BOOK | KINDLE) by Patrick Weil

This is a really interesting new book about one of the more unique Presidential biographies ever written. William C. Bullitt was a longtime American diplomat and former supporter of Woodrow Wilson who blamed the failure of American ratification of the Treaty of Versailles following World War I on the worrisome personality changes he witnessed in President Wilson after Wilson suffered a stroke and serious health issues in the final years of his Presidency. Bullitt was close to Sigmund Freud and he teamed with Freud to write a psychological biography about Wilson several years after Wilson's death. The book they wrote (Thomas Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study) was very controversial and wasn't even published until nearly 30 years after Freud himself died. It's a really fascinating story and Weil's book -- as well as the original book by Bullitt and Freud -- reveal the potential dangers behind Presidential disability.

•The World: A Family History of Humanity (BOOK | AUDIO | KINDLE) by Simon Sebag Montefiore

•Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge from Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic (BOOK | AUDIO | KINDLE) by Simon Winchester

I try to read every book that Simon Winchester writes. It seems like he's written books about basically every subject under the sun, and I can't think of a single one that I didn't find interesting.

•The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said: Son of an African General, Slave of the Ottomans, Free Man Under the Tsars, Hero of the Union Army (BOOK | KINDLE) by Dean Calbreath

The subtitle of this book alone makes it pretty clear that this is one hell of a story about a man who lived quite a life.

#Books#Book Suggestions#Book Recommendations#Reading List#Simon Winchester#Knowing What We Know#Simon Sebag Montefiore#The World: A Family History of Humanity#The Madman in the White House#Patrick Weil#Wahhabism: The History of a Militant Islamic Movement#Cole M. Bunzel#The Oswalds#Paul R. Gregory#True West: Sam Shepard's Life Work and Times#Robert Greenfield#Sam Shepard#Crown#Diversion Books#Princeton University Press#Knopf#Harvard University Press#Harper#The Sergeant: The Incredible Life of Nicholas Said#Dean Calbreath#Pegasus Books

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

we need to put margaret thatchers son back in the desert. put him in another rally car and send him out he will get lost on his own again i know he will. make sure hes there longer than a week. i refuse to believe a tory can survive the deadliest rally in the world twice.

#dakars history is fucking batshit the founder died in a helicopter crash people have been killed by stray bombs and militants#because they keep holding it in like. active warzones/where mass political strife and uprisings are occuring#and then on top of that you have Margaret thatchers shitty little son getting lost FOR A WEEK. BECAUSE HE WANTED TO DO THIS AS A HOBBY#AND PEOPLE WERE LIKE ''please do not the public money on finding your shit son'' and Thatcher had to publically state no she wont use#tax dollars to find her fucking cringe ass son who got himself lost half the world over and its not enough#that she was internationally embarrassed put HIM and his awful twin sister who did that insensitive Falklands war doco in a rally car#and send them out

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In many, though by no means all, respects, men have judged women's militancy by their own standards and have therefore missed the point as they are so prone to do. They have seen women's militancy as a contest of force in which women could never hope to win, and have therefore argued (despite abundant contrary evidence), that the women grew tired of the tactics when there was no prospect of success. But militant tactics were never intended to produce an outcome of 'might is right'; they were intended to expose men as the enemy and to make it clear what men were capable of doing to those whom they claimed to protect. And in this they were spectacularly successful. Women did not tire of these methods (as the number of volunteers for 'dangerous duty' reveals); on the contrary the harsher the methods employed by men (such as raiding WSPU premises, charging the Pethick-Lawrences and Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst with conspiracy, preventing the publication of Votes for Women, imprisoning hundreds of women - Mary Leigh and Gladys Evans for five years - forcibly feeding women), the more women were prepared to be militant.

Actually, one could argue that the changes in tactics that Christabel made constituted a decrease in militancy - if one were concerned with human values. Originally the plan was for women to be caught, to be arrested and imprisoned, but after ‘Black Friday’, when so many women were viciously and sexually mauled and assaulted by the police, and when mothers began to say that their daughters might break windows but were not to go on any more demonstrations, the plan was changed to an attack on property (beginning with government property), and the idea was that women would try to avoid being caught.

‘It is only simple justice that women demand’, stated Christabel in her pamphlet Broken Windows. ‘They have worked for their political enfranchisement as men never worked for it, by a constitutional agitation carried on on a far greater scale than any franchise agitation in the past. For fifty years they have been striving, and have met with nothing but trickery and betrayal at the hands of politicians. Cabinet Ministers have taunted them with their reluctance to use the violent methods that were being used by men before they won the extension of the franchise in 1829, in 1832 and in 1867. They have used women's dislike of violence as a reason for withholding from them the rights of citizenship . . . . The message of the broken pane is that women are determined that the lives of their sisters shall no longer be broken, and that in future those who have to obey the law shall have a voice in saying what the law shall be. Repression cannot break the spirit of liberty.'

Christabel Pankhurst's analysis of male power (and how to expose it) was often uncannily accurate, so much so that Frederick Pethick-Lawrence described her as the most brilliant political theorist and tactician - ever! She found it relatively easy to set the stage for men to demonstrate that they valued their finances more than they valued women, and when women recognised this many of them became even more angry - and set out to break more windows, dig up more golf greens, and in their worst acts of all, commit arson. To which the government and the judiciary responded with an even greater show of force against women. Such force was not always displayed against men. Christabel was also quite accurate when she stated that the male government treated male militancy very differently. Many more, and more violent, deeds, in which there was often loss of life, were committed by men in the name of Ireland, and the government bent, rather than try to break the men. Most of the prominent suffragettes acknowledged that it was not the militancy itself which men were so indignant about - it was the fact that it was undertaken by women. This was a threat to the whole social order in a way that militancy from men was not.

-Dale Spender, Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them

#dale spender#womens suffrage#womens history#militancy#male hypocrisy#british history#christabel pankhurst

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"leftists don't fall for/into right wing hate campaigns for other groups as much as they do for antisemitism" is a really funny way of broadcasting which groups you pay attention to. Anyway we all do remember V*ush and his sycophants constantly claiming "land back is a call for ethnostates" and baiting WOC to intentionally misrepresent their politics on race up to and including claiming they want white genocide, right.

Acting like somehow people on the left are often progressive about every other thing but are antisemites is absurd. It happens, but its not common. An antisemite is often also a racist, a xenophobe, religiously intolerant overall, etc. There are plenty of racist, xenophobic, shithead leftists. Anyone who's actually a leftist would know there's constant tumbling online with shithead leftists and they never have just one shithead opinion.

#cipher talk#V*ush is also an antisemite but his hate campaigns to my knowledge focus on people of color#Antisemitism is more like a sickening bonus he pulls out in these debates#Also! This sort of shit in my experience is more common than isolated 'leftist antisemitism' among actual leftists#The people following V*ush's lead consider themselves leftists#Some examples of 'leftist Antisemitism' people pull really feel like they saw an antisemite express one progressive opinion and screamed#'ITS THE DAMN LEFT AGAIN'#I promise you. A lotta people doing that are not leftists#It annoys me because there are actual common tropes of leftist antisemitism I experience but it feels like people only bring up the idea#When talking about Zionism#Actual things I've experienced have like. Nothing or little to do with that. It's more 'a lot of shit c*ntrapoints has done' and militant#Or utoptian atheism (the latter being something I've had other marginalized religious people tell me was making them uncomfortable but that#They didn't feel comfortable speaking up about in leftist spaces)#Or like. People who didn't grow up in the West saying offensive shit because they know what a Nazi is but never got a proper education#About Jewish history- generally they aren't trying to be offensive. They literally do not know better. It doesn't make it okay#But it's not the same as the other shit#Or in some cases they're like. A hypocrite who believes in anti colonialism but only for themselves#Such as that one guy who saw me speaking about Coptic issues and the importance of leftists to not cede ground to Zionists by letting them#Coopt ideas from MENA indigenous groups and said 'shut up Jew'. He didn't know I was Jewish. He was making an unfavorable comparison to#Shame me into silence#Admittedly it was funny and I still think it's funny because jeez man. At least say a slur! But it was antisemitic regardless of the fact#That I found it to stupid to be upset by#It's also notable there that like. The guy was not primarily mad because of Judaism. He was angry because of a Copt existing and talking#The Copt happened to be my freak ass and Coincidentally was what I am

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Domestically, ribu was born through the contradictions of the radical political formations of the '68 era, including the anti-Vietnam War, New Left, and student movements. Many ribu activists had experienced the radicalism of the student movements and sectarian struggles of the New Left. As defectors from existing leftist movements, ribu activists were conversant and in critical dialogue with the ongoing struggles such as those of the Sanrizuka, Shibokusa, Zainichi, and Buraku liberation activists, the politics of occupied Okinawa, and other movements including immigration, labor rights, and pollution. Following other radical movements of Japan's '68, horizontal relationality was privileged in reaction to the rigid hierarchies of the established left and many New Left sects. The movement involved a decentralized network of autonomous ribu groups that organized across the nation, from Hokkaido to Ayashi; with no formal leader, its leading activists were Japanese women in their twenties and early thirties.

Ribu's birth was traumatic and exhilarating. Having experienced a spectrum of sexist treatment and sexualized violence while organizing with leftist men, from verbal abuse to sexual assault and rape, ribu activists revolted against the myriad ways that sexism and misogyny were endemic across leftist culture. Women typically supported male leadership through domestic labor, by cleaning, cooking, and other housekeeping duties. There were instances when young women activists were referred to as public toilets [benjos] and assaulted and raped by leftist male activists. In some cases, the rape of the women of rival leftist sects became part of the New Left's tactics of uchi geba [internal violence or conflict]. In 1968, Oguma Eiji describes such incidents of sexual violence. Ribu activists spoke, wrote, and testified about their experiences of sexism, assault, and rape at the hands of leftist male activists. Given such forms of sexual violence that were hidden, too often, in the shadows of Japan's 1968, how did ribu women respond?

Never before in the records of Japanese history had ink sprayed such rage-filled declarations of revolt against Japanese heteropatriarchy and sexist men. The slogans of the movement, like the "liberation of sex and the "liberation from the toilet" [benjo kara no kaiho], unleashed an unprecedented flurry of militant feminist denunciations. With minikomi (alternative media] titles such as Onna no hangyaku [Woman's Mutiny] and art evoking images of vaginas with spikes, ribu activists raised a political banner that had never been so explicit and bold in its declaration of sexual oppression and sexual discrimination.

Ribu activists reacted to the counterculture movement of the 1960s and the sexual revolution. Some of its earliest activists, such as Yonezu Tomoko, criticized the "free love" espoused by male activists even while they emphasized the importance of politicizing sex. Along with her student comrade Mori Setsuko, Yonezu named their cell "Thought Group SEX," and painted "SEX" on their helmets the first time they disrupted a campus event at Tama Arts University in Tokyo. Sex and sexuality emerged as key concepts in ribu's manifestos for human liberation. The politicization of sex was a revolt against the sexism in mainstream society and the Japanese left. Heralding the importance of liberating sex also distinguished ribu from former Japanese women's liberation movements, Tanaka Mitsu, a leading activist and theorist of the movement, harshly criticized previous women's movements, saying that the "hysterical unattractiveness" of those "scrawny women" was due to their having to become like men. The brazen and contemptuous tone of their manifestos was a stark departure from past political speech about women's liberation.

This emphasis on sexual liberation evinced ribu's affinity with US radical feminist movements that also exploded in 1970." Ribu activists recognized their shared conditions when they heard news of women's liberation movements emerging in the United States. Information about these movements flowed into Japan via news and alternative media, as documented by Masami Saitō. Japan's largest newspapers, the Yomiuri and Asahi Shimbun, printed photos of thousands of women protesters in the streets of New York City for the August 26, 1970, Women's Strike. Anti-war posters with defaced US flags decorated the walls of ribu communes and organizing centers." Activists from the United States and Europe visited ribu centers." This cross-border exchange among activists also characterized the internationalist spirit of '68 and a common desire for liberation.

Like so many others around the world, ribu activists were also inspired by the Black Power movement and attempted to follow its lead. This passage from a ribu pamphlet evinces how ribu activists were emboldened by Black Power struggles - as were radical feminists in the United States - and drew new lines of departure and separation from the leftist men with whom they had been organizing.

By calling white cops "pigs," Blacks struggling in America began to constitute their own identity by confirming their distance from white- centered society in their daily lives. This being the beginning of the process to constitute their subjectivity, whom then should women be calling the pigs?... First, we have to strike these so-called male revolutionaries whose consciousness is desensitized to their own form of existence. We have to realize that if we don't strike our most familiar and direct oppressors, we can never "overthrow Japanese imperialism"... Those men who possess such facile thoughts as, "Since we are fighting side by side, we are of the same-mind," are the pigs among us."

For leftist women to be calling leftist male revolutionaries pigs constituted a kind of declaration of war against sexism in their midst and their newfound enemy-sexist leftist men. When women of the left began to identify this intimate enemy, this moment of dis-identification with Japanese leftist men constituted a decisive epistemic break. Their conflict with sexist male comrades forced these women to recognize that they had to redefine their relationship to the revolution from the specificity of their own subject position."

- Setsu Shigematsu, "'68 and the Japanese Women's Liberation Movement," in Gavin Walker, ed., The Red Years: Theory, Politics and Aesthetics in the Japanese ‘68. London and New York: Verso, 2020. p. 79-82

#setsu shigematsu#ribu#revolutionary feminism#feminist history#patriarchal violence#heteropatriarchy#social justice#history of social justice#militant action#far left#new left#1968#japanese 68#japanese history#left history#academic quote#reading 2023

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'all ever just see a post that is shaped like a hornet's nest with a giant sign reading KICK ME, and oh god, you want to kick it SO BAD but you know it would be a bad idea? But you still want to?

Since that is me right now. Oy.

#hilary for ts#for clarity: this is about the post going around#that is rightfully dogging on the washington post for its terrible headline about the cuba gay marriage vote#wherein the tumblrina leftists have rushed in to defend communist cuba#and paint fidel castro as some principled defender of LGBT rights#and i.... i just can't#the brainworms y'all#THE BRAINWORMS#me banging pots and pans: WHY ARE YOU ALL SO FUCKING STUPID#i could write an entire post about anti-homosexual policies in 60s cuba under castro and the militant homophobia of the USSR#with which cuba was closely allied#anyway yet again the Tumblr History is gonna end me#this has been a post

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beeb Man Sits On Lesbian … while Sue reads on with a woman chained to her desk

Daily Mirror, 24 May 1988

#section 28#militant lesbian#queer history#lgbqti#queer#demonstration#protest#lesbian#activism#activists#margaret thatcher#daily mirror#headlines#news clipping#sue lawley#nicholas witchell#homophobia#bbc#bbc news#1980s#80s#1988

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fun fact! The Irish Civil war ended on 24th of May 1923! Meaning tomorrow is the 100 year anniversary 🎉

1798 🤝 Irish Civil War: Something Happened On The 24th Of May

#the 100th anniversary of 1798 was marked by a committee putting out fun propaganda pamphlets and um protestant militants defacing graves#irish history#asks#anon#jory.txt

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading about philip josephs and the early anarchist movement in aotearoa and i am Fascinated by the existence of nihilism as a political stance

#it basically stood in opposition to reformism#the idea is ''gradual change is pointless and will never actually change anything; the current order needs to be completely uprooted''#the movement originated in late 1800s latvia i think?? it was a more militant wing of a widespread jewish anarchists union#im curious if. sorry to disco elysium all over real politics but. i believe theres an innocence of nihilism introduced in the 70s#i wonder if the politics of nihilism in elysium are inspired by/based on irl nihilist socialism at all#i wouldnt be surprised tbh the elysium authors seem pretty familiar with anarcho-communist theory and history#or sorry not necessarily a more militant wing of the bund but a more radical one idk if the nihilists actually Did anything#and the bund were a marxist union not an anarchist one they just radicalized people who then became notable anarchists#anyway. wild

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cersei makes such bad decisions like babe please

#asoiaf reread#cersei lannister#girly's out here restoring the Faith Militant like pick up a history book please#I love her and all her bad decisions tho

2 notes

·

View notes