#paywall articles

Text

Peter Singer would sooner donate a kidney than sponsor a concert hall. So when entertainment mogul David Geffen gave $100 million in early March for the renovation of Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center in New York—it will soon be renamed David Geffen Hall—Mr. Singer questioned why people thought he was doing so much good.

Over Skype from his home in Melbourne, Australia, Mr. Singer says that he doesn’t understand “how anyone could think that giving to the renovation of a concert hall that could impact the lives of generally well-off people living in Manhattan and well-off tourists that come to New York could be the best thing that you could do with $100 million.” He notes, for example, that a donation of less than $100 could restore sight to someone who is blind. Mr. Geffen declined to comment.

In his new book, “The Most Good You Can Do,” to be released on Tuesday, Mr. Singer argues that people should give a substantial percentage—ideally a third—of their income to charities. Mr. Singer himself has given away at least 10% of his income for 40 years; that number has gradually risen to between a quarter and a third of his income. He advocates focusing donations on the developing world. Once the world’s more basic needs have been met, he says, “then help people listen to concerts in beautiful concert halls.”

It’s a controversial way to encourage philanthropy. Some critics find it uncharitable—and counterproductive—to wag a disapproving finger at any sort of charitable giving, or to rank one type above another. Supporting cultural institutions through private donations, they argue, improves the quality of life for an entire society.

I understand where this argument is coming from. Art and culture still contribute value (ex. providing communal spaces / subjects for discussion or relaxation), but this value is very difficult to quantify. But still, my intuition tells me that the $100 million dollars would contribute more toward the reduction of suffering if invested in more directly altruistic causes.

A scholar with appointments at Princeton University and the University of Melbourne, Mr. Singer, 68, considers himself a utilitarian philosopher. “To be a utilitarian is to decide what one ought to do by the principle of what will have the best consequences,” he says. “To be a utilitarian philosopher is to think about how this view can be defended and how it should be applied in a variety of contexts.”

With his recent book’s focus on philanthropy, he hopes to change how we think about what it means to be ethical. “If you ask people what it means to live ethically, it’s a ‘Thou shalt not’ statement: ‘You shouldn’t cheat’ and ‘You shouldn’t lie,’ ” he says. “But if you’re fortunate enough to be part of the more affluent billion in the world, to live ethically, you have to do something to help those who are less fortunate, who just happened to have been born in impoverished countries, and that’s part of living an ethical life.”

Mr. Singer rose to prominence with his 1975 book “Animal Liberation,” in which he argued that animals should be treated with the same respect as humans and that some animals are smarter than both children and severely impaired adults. The capacity to have conscious experiences, such as pleasure and pain, he says, is the key difference between beings that are morally significant and those that are not. He has drawn harsh criticism for his support of certain types of euthanasia and, in some circumstances, infanticide.

The author of more than a dozen books, including “Practical Ethics” (1979) and “Rethinking Life and Death” (1994), Mr. Singer has long argued that it is morally wrong for some people to live luxuriously while others starve. His new book, along with the “effective altruism” movement that he has helped to start, is an effort to put those beliefs into practice.

In the past few years, Mr. Singer began to find that students and recent graduates were more receptive to his philosophy on giving than were older adults. Millennials, he says, are the most altruistic generation he has yet to come across, which he attributes in part to technology. “It connects them all over the world, so they’re more cosmopolitan, and the barriers between people in different countries and far away have declined,” he says. “Another factor is that with the IT revolution, a different kind of person makes a lot of money and…they’re extremely well paid, and they’re wondering what to do with that money.”

Across generations, he also finds that the newly wealthy tend to be more driven by data. They want evidence that charities are sending funds to where they are most needed, an effort that Mr. Singer champions in his book.

“The normal thing to do is accumulate wealth for yourself and spend it for yourself,” he says. “But if [people] were to stop and think and say, ‘Does my welfare really matter more than someone else’s?’ they might say, ‘Well, it matters more to me, yes, but then his or her welfare matters more to him or her.’ ” Ultimately, he hopes that people will get beyond focusing on themselves and “look at this larger point of view of the universe.”

Born in Melbourne to parents who had escaped from Nazi-occupied Austria, Mr. Singer now splits his time between Princeton, N.J., and Melbourne. He and his wife have three adult children.

As for how he has disposed of his own income over the years, Mr. Singer concedes that he did make family vacations a priority. “We spend money on [vacations] that no doubt could do more elsewhere, but that’s something that’s important…. I work pretty hard during the normal year, and my wife’s been working as well, so we think it’s worth making that time” for the family, he explains. (1)

^I don’t think this is problematic hypocrisy - to still spend money on family vacation. We all need hobbies + activities that recharge us so we can better show up in our work. And besides, the point of life can’t only be to reduce suffering. The point of reducing suffering is to give people freedom so that they can enjoy the pleasures of this precious life. As Thomas Nagel put it in The View from Nowhere:

There is a great deal of misery in the world, and many of us could easily spend our lives trying to eradicate it… But how could the main point of human life be the elimination of evil? Misery, deprivation, and injustice prevent people from pursuing the positive goods which life is assumed to make possible. If all such goods were pointless and the only thing that really mattered was the elimination of misery, that really would be absurd.

Mr. Singer and his wife give mostly to charities that aid people in the developing world, including to groups that send money to people in need and that provide bed nets to help prevent the spread of malaria in Africa.

Though he has focused in recent years on giving, Mr. Singer says that his views on other subjects have not changed. He still thinks that the suffering of animals is comparable to human suffering. “At the moment, I’d say we don’t really know enough about how we compare the tragedy of a family losing a child with the suffering of chickens confined for a year in a crowded space [where they] can’t stretch their wings,” he says.

Mr. Singer has also been both criticized and lauded for his position on income inequality. He supports higher, more progressive tax rates. “I think most sensible people do believe if you earn half a million, you should be taxed at a higher percentage rate than someone who earns $50,000 or $100,000.”

In his new book, he makes a case for people to tax themselves through giving. “They’re adding more meaning to their lives rather than spending money on things that don’t make much of a difference to quality of life,” he says. “There are plenty of studies,” he adds, “showing that beyond a certain level—around $75,000—having more money doesn’t make much of a difference in well-being.”

In the years ahead, Mr. Singer hopes to increase the percentage of his own income that he donates. “I see it as a continuing process,” he says. How can others learn to be more altruistic? He pauses and then responds, “I suppose studying philosophy is really the answer.”

1. https://www.wsj.com/articles/peter-singer-on-the-ethics-of-philanthropy-1428083293

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

DO NOT DO THIS!!!

If a website has a paywall, like New York Times, DO NOT use the ctrl+A shortcut then the ctrl+c shortcut as fast as you can because then you may accidentally copy the entire article before the paywall comes up. And definitely don't do ctrl+v into the next google doc or whatever you open because then you will accidentally paste the entire article into a google doc or something!!!! I repeat DO NOT do this because it is piracy which is absolutely totally wrong!!!

125K notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm begging you guys to start pirating shit from streaming platforms. there are so many websites where you can stream that shit for free, here's a quick HOW TO:

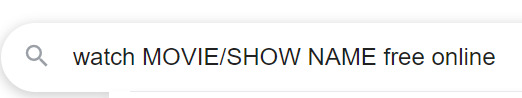

1) Search for: watch TITLE OF WORK free online

2) Scroll to the bottom of results. Click any of the "Complaint" links

3) You will be taken to a long list of links that were removed for copyright infringement. Use the 'find' function to search for the name of the show/movie you were originally searching for. You will get something like this (specifics removed because if you love an illegal streaming site you don't post its url on social media)

4) each of these links is to a website where you can stream shit for free. go to the individual websites and search for your show/movie. you might have to copy-paste a few before you find exactly what you're looking, but the whole process only takes a minute. the speed/quality is usually the same as on netflix/whatever, and they even have subtitles! (make sure to use an adblocker though, these sites are funded by annoying popups)

In conclusion, if you do this often enough you will start recognizing the most dependable websites, and you can just bookmark those instead. (note: this is completely separate from torrenting, which is also a beautiful thing but requires different software and a vpn)

you can also download the media in question (look for a "download" button built into the video window, or use a browser extension such as Video DownloadHelper.)

#for adblocking--ublock origin is my favorite but adblocker plus is also popular#also i once again highly recommend using firefox especially on mobile#to enable adblock on firefox mobile just click 3 dot menu > addons > addon manager > enable uBlockOrigin#that's for android i assume it's similar for iOS#update it is NOT similar for iOS bc Apple hates you. i'll write another post later#anyway. PLEASE USE AN ADBLOCK ALL THE TIME (except for specific websites you want to support)#your internet browsing experience will be so enormously improved#also on firefox if you want to get past a paywall click the 'Toggle reader view' button as soon as the page loads#(it's on the right of the taskbar. a little rectangle with horizontal lines)#works for most news sites by showing you the webpage text that is hidden under the 'you've run out of free articles' popup#doesn't work for everything but it's worth a shot

80K notes

·

View notes

Text

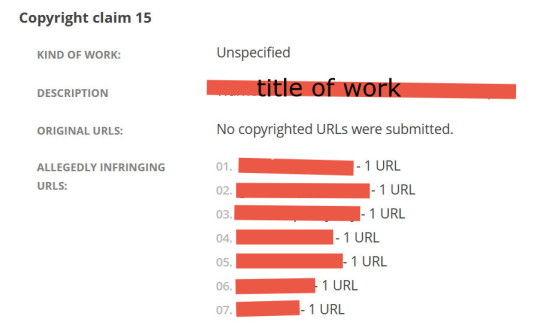

Good morning everybody

EDIT: new link bc I didn’t know the Washington post was owned by Jeff 🙃

#wga strike#now this?#im so happy#amazon#Amazon lawsuit#also the paywall#must have been my one free article 🤪

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

I swear to God if you wrote something like this into a political satire like Spitting Image, it’d be called too on-the-nose.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The young woman was catatonic, stuck at the nurses’ station — unmoving, unblinking and unknowing of where or who she was.

Her name was April Burrell.

Before she became a patient, April had been an outgoing, straight-A student majoring in accounting at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. But after a traumatic event when she was 21, April suddenly developed psychosis and became lost in a constant state of visual and auditory hallucinations. The former high school valedictorian could no longer communicate, bathe or take care of herself.

April was diagnosed with a severe form of schizophrenia, an often devastating mental illness that affects approximately 1 percent of the global population and can drastically impair how patients behave and perceive reality.

“She was the first person I ever saw as a patient,” said Sander Markx, director of precision psychiatry at Columbia University, who was still a medical student in 2000 when he first encountered April. “She is, to this day, the sickest patient I’ve ever seen.”

It would be nearly two decades before their paths crossed again. But in 2018, another chance encounter led to several medical discoveries reminiscent of a scene from “Awakenings,” the famous book and movie inspired by the awakening of catatonic patients treated by the late neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks.

Markx and his colleagues discovered that although April’s illness was clinically indistinguishable from schizophrenia, she also had lupus, an underlying and treatable autoimmune condition that was attacking her brain.

After months of targeted treatments — and more than two decades trapped in her mind — April woke up.

The awakening of April — and the successful treatment of other peoplewith similar conditions — now stand to transform care for some of psychiatry’s sickest patients, many of whom are languishing in mental institutions.

Researchers working with the New York state mental health-care system have identified about 200 patients with autoimmune diseases, some institutionalized for years, who may be helped by the discovery.

And scientists around the world, including Germany and Britain, are conducting similar research, finding that underlying autoimmune and inflammatory processes may be more common in patients with a variety of psychiatric syndromes than previously believed.

Although the current research probably will help only a small subset of patients,the impact of the work is already beginning to reshape the practice of psychiatry and the way many cases of mental illness are diagnosed and treated.

“These are the forgotten souls,” said Markx. “We’re not just improving the lives of these people, but we’re bringing them back from a place that I didn’t think they could come back from.”

– A catatonic woman awakened after 20 years. Her story may change psychiatry.

#block JavaScript in site settings if article is paywalled#April burrel#disability#schizophrenia#lupus#mental illness#catatonia#chronic illness#institutionalization#psychiatry#medical science#healthcare#autoimmune disease#Washington post#knee of huss

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

. . . But in 1948 Israel declared its sovereignty from the British Mandate through the besiegement of indigenous Palestinians. The new nation retained Regulation 133(3) with an important caveat: It was amended to give military commanders complete control over where a body is buried, as opposed to the original “community to which such person belongs.” This is the legal basis of postmortem detention, and over the last 80 years the scope of the law has expanded greatly. Namely, who is subject to postmortem detention by the military (from “enemy soldier” to the blanket term “terrorist”) and when the state is entitled to seize bodies (from “times of war” to “forever war on terror”).

Regulation 133(3) can now impose restrictions on funerals when a body is returned to a family. When Palestinian prisoner Mustafa Arabat succumbed to torture in 1992, Israeli courts ruled in favor of the military to enforce that his funeral be held in the middle of the night and only attended by immediate family. Today, families whose bodies are eventually returned to them must abide by the military’s rules on how to express their final rites. Israeli law explicitly defines these funerals as a threat to “public order” and grants soldiers power over a family’s grieving.

. . . full article on The Nation (29 June, 2023)

[archived link]

#palestine#israel#gaza#i've seen this article spread around before but here it is with an archived link (which lets you bypass the paywall)

800 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boycotting works. Keep it up.

#the article is paywalled so there's not really a way for me to quote more info#Indigo / Chapters#Free Palestine

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title & subtitle:

[Nov. 21] The Harvard Law Review Refused to Run This Piece About Genocide in Gaza: The piece was nearing publication when the journal decided against publishing it. You can read the article here.

Article text:

On Saturday, the board of the Harvard Law Review voted not to publish “The Ongoing Nakba: Towards a Legal Framework for Palestine,” a piece by Rabea Eghbariah, a human rights attorney completing his doctoral studies at Harvard Law School. The vote followed what an editor at the law reviewdescribed in an e-mail to Eghbariah as “an unprecedented decision” by the leadership of the Harvard Law Review to prevent the piece’s publication.

Eghbariah told The Nation that the piece, which was intended for the HLR Blog, had been solicited by two of the journal’s online editors. It would have been the first piece written by a Palestinian scholar for the law review. The piece went through several rounds of edits, but before it was set to be published, the president stepped in. “The discussion did not involve any substantive or technical aspects of your piece,” online editor Tascha Shahriari-Parsa, wrote Eghbariah in an e-mail shared with The Nation. “Rather, the discussion revolved around concerns about editors who might oppose or be offended by the piece, as well as concerns that the piece might provoke a reaction from members of the public who might in turn harass, dox, or otherwise attempt to intimidate our editors, staff, and HLR leadership.”

On Saturday, following several days of debate and a nearly six-hour meeting, the Harvard Law Review’s full editorial body came together to vote on whether to publish the article. Sixty-three percent voted against publication. In an e-mail to Egbariah, HLR President Apsara Iyer wrote, “While this decision may reflect several factors specific to individual editors, it was not brd on your identity or viewpoint.”

In a statement that was shared with The Nation, a group of 25 HLR editors expressed their concerns about the decision. “At a time when the Law Review was facing a public intimidation and harassment campaign, the journal’s leadership intervened to stop publication,” they wrote. “The body of editors—none of whom are Palestinian—voted to sustain that decision. We are unaware of any other solicited piece that has been revoked by the Law Review in this way. “

When asked for comment, the leadership of the Harvard Law Review referred The Nation to a message posted on the journal’s website. “Like every academic journal, the Harvard Law Review has rigorous editorial processes governing how it solicits, evaluates, and determines when and whether to publish a piece…” the note began. ”Last week, the full body met and deliberated over whether to publish a particular Blog piece that had been solicited by two editors. A substantial majority voted not to proceed with publication.”

Today, The Nation is sharing the piece that the Harvard Law Review refused to run.

enocide is a crime. It is a legal framework. It is unfolding in Gaza. And yet, the inertia of legal academia, especially in the United States, has been chilling. Clearly, it is much easier to dissect the case law rather than navigate the reality of death. It is much easier to consider genocide in the past tense rather than contend with it in the present. Legal scholars tend to sharpen their pens after the smell of death has dissipated and moral clarity is no longer urgent.

Some may claim that the invocation of genocide, especially in Gaza, is fraught. But does one have to wait for a genocide to be successfully completed to name it? This logic contributes to the politics of denial. When it comes to Gaza, there is a sense of moral hypocrisy that undergirds Western epistemological approaches, one which mutes the ability to name the violence inflicted upon Palestinians. But naming injustice is crucial to claiming justice. If the international community takes its crimes seriously, then the discussion about the unfolding genocide in Gaza is not a matter of mere semantics.

The UN Genocide Convention defines the crime of genocide as certain acts “committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.” These acts include “killing members of a protected group” or “causing serious bodily or mental harm” or “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

Numerous statements made by top Israeli politicians affirm their intentions. There is a forming consensus among leading scholars in the field of genocide studies that “these statements could easily be construed as indicating a genocidal intent,” as Omer Bartov, an authority in the field, writes. More importantly, genocide is the material reality of Palestinians in Gaza: an entrapped, displaced, starved, water-deprived population of 2.3 million facing massive bombardments and a carnage in one of the most densely populated areas in the world. Over 11,000 people have already been killed. That is one person out of every 200 people in Gaza. Tens of thousands are injured, and over 45% of homes in Gaza have been destroyed. The United Nations Secretary General said that Gaza is becoming a “graveyard for children,” but a cessation of the carnage—a ceasefire—remains elusive. Israel continues to blatantly violate international law: dropping white phosphorus from the sky, dispersing death in all directions, shedding blood, shelling neighborhoods, striking schools, hospitals, and universities, bombing churches and mosques, wiping out families, and ethnically cleansing an entire region in both callous and systemic manner. What do you call this?

The Center for Constitutional Rights issued a thorough, 44-page, factual and legal analysis, asserting that “there is a plausible and credible case that Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinian population in Gaza.” Raz Segal, a historian of the Holocaust and genocide studies, calls the situation in Gaza “a textbook case of Genocide unfolding in front of our eyes.” The inaugural chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno Ocampo, notes that “Just the blockade of Gaza—just that—could be genocide under Article 2(c) of the Genocide Convention, meaning they are creating conditions to destroy a group.” A group of over 800 academics and practitioners, including leading scholars in the fields of international law and genocide studies, warn of “a serious risk of genocide being committed in the Gaza Strip.” A group of seven UN Special Rapporteurs has alerted to the “risk of genocide against the Palestinian people” and reiterated that they “remain convinced that the Palestinian people are at grave risk of genocide.” Thirty-six UN experts now call the situation in Gaza “a genocide in the making.” How many other authorities should I cite? How many hyperlinks are enough?

And yet, leading law schools and legal scholars in the United States still fashion their silence as impartiality and their denial as nuance. Is genocide really the crime of all crimes if it is committed by Western allies against non-Western people?

This is the most important question that Palestine continues to pose to the international legal order. Palestine brings to legal analysis an unmasking force: It unveils and reminds us of the ongoing colonial condition that underpins Western legal institutions. In Palestine, there are two categories: mournable civilians and savage human-animals. Palestine helps us rediscover that these categories remain racialized along colonial lines in the 21st century: the first is reserved for Israelis, the latter for Palestinians. As Isaac Herzog, Israel’s supposed liberal President, asserts: “It’s an entire nation out there that is responsible. This rhetoric about civilians not aware, not involved, it’s absolutely not true.”

Palestinians simply cannot be innocent. They are innately guilty; potential “terrorists” to be “neutralized” or, at best, “human shields” obliterated as “collateral damage”. There is no number of Palestinian bodies that can move Western governments and institutions to “unequivocally condemn” Israel, let alone act in the present tense. When contrasted with Jewish-Israeli life—the ultimate victims of European genocidal ideologies—Palestinians stand no chance at humanization. Palestinians are rendered the contemporary “savages” of the international legal order, and Palestine becomes the frontier where the West redraws its discourse of civility and strips its domination in the most material way. Palestine is where genocide can be performed as a fight of “the civilized world” against the “enemies of civilization itself.” Indeed, a fight between the “children of light” versus the “children of darkness.”

The genocidal war waged against the people of Gaza since Hamas’s excruciating October 7th attacks against Israelis—attacks which amount to war crimes—has been the deadliest manifestation of Israeli colonial policies against Palestinians in decades. Some have long ago analyzed Israeli policies in Palestine through the lens of genocide. While the term genocide may have its own limitations to describe the Palestinian past, the Palestinian present was clearly preceded by a “politicide”: the extermination of the Palestinian body politic in Palestine, namely, the systematic eradication of the Palestinian ability to maintain an organized political community as a group.

This process of erasure has spanned over a hundred years through a combination of massacres, ethnic cleansing, dispossession, and the fragmentation of the remaining Palestinians into distinctive legal tiers with diverging material interests. Despite the partial success of this politicide—and the continued prevention of a political body that represents all Palestinians—the Palestinian political identity has endured. Across the besieged Gaza Strip, the occupied West Bank, Jerusalem, Israel’s 1948 territories, refugee camps, and diasporic communities, Palestinian nationalism lives.

What do we call this condition? How do we name this collective existence under a system of forced fragmentation and cruel domination? The human rights community has largely adopted a combination of occupation and apartheid to understand the situation in Palestine. Apartheid is a crime. It is a legal framework. It is committed in Palestine. And even though there is a consensus among the human rights community that Israel is perpetrating apartheid, the refusal of Western governments to come to terms with this material reality of Palestinians is revealing.

Once again, Palestine brings a special uncovering force to the discourse. It reveals how otherwise credible institutions, such as Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch, are no longer to be trusted. It shows how facts become disputable in a Trumpist fashion by liberals such as President Biden. Palestine allows us to see the line that bifurcates the binaries (e.g. trusted/untrusted) as much as it underscores the collapse of dichotomies (e.g. democrat/republican or fact/claim). It is in this liminal space that Palestine exists and continues to defy the distinction itself. It is the exception that reveals the rule and the subtext that is, in fact, the text: Palestine is the most vivid manifestation of the colonial condition upheld in the 21st century.

hat do you call this ongoing colonial condition? Just as the Holocaust introduced the term “Genocide” into the global and legal consciousness, the South African experience brought “Apartheid” into the global and legal lexicon. It is due to the work and sacrifice of far too many lives that genocide and apartheid have globalized, transcending these historical calamities. These terms became legal frameworks, crimes enshrined in international law, with the hope that their recognition will prevent their repetition. But in the process of abstraction, globalization, and readaptation, something was lost. Is it the affinity between the particular experience and the universalized abstraction of the crime that makes Palestine resistant to existing definitions?

Scholars have increasingly turned to settler-colonialism as the lens through which we assess Palestine. Settler-colonialism is a structure of erasure where the settler displaces and replaces the native. And while settler-colonialism, genocide, and apartheid are clearly not mutually exclusive, their ability to capture the material reality of Palestinians remains elusive. South Africa is a particular case of settler-colonialism. So are Israel, the United States, Australia, Canada, Algeria, and more. The framework of settler colonialism is both useful and insufficient. It does not provide meaningful ways to understand the nuance between these different historical processes and does not necessitate a particular outcome. Some settler colonial cases have been incredibly normalized at the expense of a completed genocide. Others have led to radically different end solutions. Palestine both fulfills and defies the settler-colonial condition.

We must consider Palestine through the iterations of Palestinians. If the Holocaust is the paradigmatic case for the crime of genocide and South Africa for that of apartheid, then the crime against the Palestinian people must be called the Nakba.

The term Nakba, meaning “Catastrophe,” is often used to refer to the making of the State of Israel in Palestine, a process that entailed the ethnic cleansing of over 750,000 Palestinians from their homes and destroying 531 Palestinian villages between 1947 to 1949. But the Nakba has never ceased; it is a structure not an event. Put shortly, the Nakba is ongoing.

In its most abstract form, the Nakba is a structure that serves to erase the group dynamic: the attempt to incapacitate the Palestinians from exercising their political will as a group. It is the continuous collusion of states and systems to exclude the Palestinians from materializing their right to self-determination. In its most material form, the Nakba is each Palestinian killed or injured, each Palestinian imprisoned or otherwise subjugated, and each Palestinian dispossessed or exiled.

The Nakba is both the material reality and the epistemic framework to understand the crimes committed against the Palestinian people. And these crimes—encapsulated in the framework of Nakba—are the result of the political ideology of Zionism, an ideology that originated in late nineteenth century Europe in response to the notions of nationalism, colonialism, and antisemitism.

As Edward Said reminds us, Zionism must be assessed from the standpoint of its victims, not its beneficiaries. Zionism can be simultaneously understood as a national movement for some Jews and a colonial project for Palestinians. The making of Israel in Palestine took the form of consolidating Jewish national life at the expense of shattering a Palestinian one. For those displaced, misplaced, bombed, and dispossessed, Zionism is never a story of Jewish emancipation; it is a story of Palestinian subjugation.

What is distinctive about the Nakba is that it has extended through the turn of the 21st century and evolved into a sophisticated system of domination that has fragmented and reorganized Palestinians into different legal categories, with each category subject to a distinctive type of violence. Fragmentation thus became the legal technology underlying the ongoing Nakba. The Nakba has encompassed both apartheid and genocidal violence in a way that makes it fulfill these legal definitions at various points in time while still evading their particular historical frames.

Palestinians have named and theorized the Nakba even in the face of persecution, erasure, and denial. This work has to continue in the legal domain. Gaza has reminded us that the Nakba is now. There are recurringthreats by Israeli politicians and other public figures to commit the crime of the Nakba, again. If Israeli politicians are admitting the Nakba in order to perpetuate it, the time has come for the world to also reckon with the Palestinian experience. The Nakba must globalize for it to end.

We must imagine that one day there will be a recognized crime of committing a Nakba, and a disapprobation of Zionism as an ideology brd on racial elimination. The road to get there remains long and challenging, but we do not have the privilege to relinquish any legal tools available to name the crimes against the Palestinian people in the present and attempt to stop them. The denial of the genocide in Gaza is rooted in the denial of the Nakba. And both must end, now.

#palestine#uspol#the nation#geopol#long post#the article is paywalled so here it is for ease of access#📁.zip

488 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Source)

#destiel#us politics#Angela Chao#Mitch McConnell#Tesla#billionaire#castiel#dean winchester#breaking news#i hate linking to the daily mail but don't want to link to a paywalled WSJ article

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Understanding the Power of Intrinsic Motivation" (HBR)

Summary.

At some point, we all are assigned to work that we find tedious and unchallenging. If we don’t figure out how to turn these tasks into interesting and challenging problems to solve, we’ll struggle to complete tasks in a timely and reliable manner, sabotaging our own success and growth at work. One skill that can help you do this is intrinsic motivation, or the incentive you feel to complete a task simply because you find it interesting or enjoyable. Learning how to harness this skill early in your career will help you build the resilience you need to reach your goals in any field. Here’s how to get started.

Look to understand how your job fits into the bigger picture. If you don’t feel like you’re contributing value, you’re more likely to become demotivated. The next time you’re assigned a vague task ask: What problem are we trying to solve by doing this work? How am I helping contribute to the solution? When you know that your contributions have a purpose, your tasks will immediately feel more interesting.

Perform easy tasks right away. When we check items off our to-do lists, feel-good hormones are released in our brains. This makes us feel accomplished, which makes the task more interesting and rewarding, which in turn, makes us more motivated to do it.

Avoid too much “mindless” repetition. When a task starts to feel boring, it’s often because the outcome of completing the task is no longer interesting to you. What can you do to change that, and make the outcome feel exciting? For example, can you challenge yourself to execute the task in less time while still achieving the same result or better?

Look for opportunities to help others. One of the easiest ways to tap into intrinsic motivation is to participate in activities you find inherently rewarding. Helping others is an easy way to do this.

At our jobs, we will inevitably face activities that don’t naturally interest us or that we perceive as boring, irrelevant, uncomfortable, or too difficult. This is rooted in how our brains are designed: Though the brain rewards us for spending mental energy on expanding ourselves, it rewards us even more for conserving our energy — which is why we struggle with activities that don’t immediately spark our curiosity, or why we tend to get bored with things over time.

If we don’t figure out how to turn these activities into interesting and challenging problems to solve, we’ll struggle to complete tasks in a timely and reliable manner, sabotaging our own success and growth at work.

This is where tapping into our intrinsic motivation can help. Intrinsic motivation is a term used to describe the incentive we feel to complete a task simply because we find it interesting or enjoyable. Extrinsic motivation is what we feel when we complete a task for some external reward.

In short, intrinsic motivation allows us to perform at our very best. Learning how to harness this skill early in your career will help us build the resilience we need to reach our goals in any field, and teach us how to bring more joy into your day-to-day job. Here are six simple ways to tap into your intrinsic motivation.

Look to understand how your job fits into the bigger picture.

When you’re assigned a project or a task at work, it’s typically a part of the solution to a larger problem or a step on the way to reach a larger goal. But early in your career, it may be difficult to see the value you’re contributing — and if you don’t feel like you’re contributing value, you’re more likely to become demotivated, as most people have a psychological need to feel that their efforts aren’t in vain.

The next time you’re asked to do something vague — “Can you deliver this to me by 1 pm tomorrow? “Can you look into this for me?” “Can you create materials X and Y and email them to me?” — ask questions like:

What problem are we trying to solve by doing these tasks?

How big is the problem?

How frequently does the problem occur?

What negative consequences does it cause?

What additional benefits could be gained by solving it?

How am I helping contribute to the solution?

The answers will help you discover the value you’re bringing. For example, let’s say you’re asked to make 100 copies of a press release for a new product. Initially, this may seem tedious, but if you dig a little deeper you could discover your work is helping to bring in new customers or put the product in front of communities who need it. Or maybe you’re asked to alphabetize a large spread sheet of data. At first, the task probably feels boring. But after asking a few questions, you may learn that you’re making important information more accessible to people across your company. When you know that your contributions have a purpose, your tasks will immediately feel more interesting.

Perform easy tasks right away.

Be action-oriented and strive to perform simple tasks right away. If you’re in a meeting, for instance, and it’s decided that another meeting is required to complete the discussion, send out the invite for the additional meeting right after the current meeting concludes. If someone calls or emails to request information, and you have it readily available, send the information over right away.

It may sound like the advice here is to complete simple tasks quickly just to get them out of the way. But the idea is actually to collect easy wins. When we check items off our to-do lists, feel-good hormones are released in our brains. This makes us feel accomplished, which makes the task more interesting and rewarding, which in turn, makes us more motivated to do it. If you adopt this habit, you’ll do more than increase your intrinsic motivation to complete easy tasks. You’ll also begin to establish and even perceive yourself as a responsive and helpful professional, while avoiding a backlog of work.

Avoid too much “mindless” repetition.

Another way to make a task more interesting is to change how you approach it. Because we’re energy-conserving creatures, we often stop challenging ourselves and start performing tasks the same way repeatedly out of habit. This leads to boredom because, over time, the tasks become less challenging.

What can you do to make the outcome feel exciting? For example, can you challenge yourself to execute the task in less time while still achieving the same result or better? I use this approach every day to sharpen my mind, perform better, and to make sure that I continuously improve some aspect of my work.

Look for opportunities to help your colleagues.

One of the easiest ways to tap into intrinsic motivation is to participate in activities you find inherently rewarding. For example, when we help people, we take a break from our own worries, which relaxes us. When we succeed in helping someone, we get energizing feedback that tells us we are okay, strong, and in control.

Every day, make it a goal to help a colleague in some way. For instance, if your peer is struggling to design a presentation, and you’re especially skilled in this area, offer to lend them a hand. If you’re great at data analysis, and someone is finding it difficult to measure the outcome of a project, see if you can give them feedback. These positive experiences will motivate you to continue sharing knowledge, making your workday more rewarding and enjoyable.

Channel your frustrations into solutions.

It’s normal to feel frustrated from time to time at work. But letting negative feelings overwhelm you is the kryptonite to intrinsic motivation and will ultimately derail you from reaching your goals. Negative thoughts and feelings, when unmanaged, slow your brain down, increase your stress levels, and make it more difficult to solve problems.

To avoid this, set aside 15 to 30 minutes on your calendar whenever you feel overwhelmed by negative emotions at work. Use this time to privately to reflect: You might process difficult interactions, vent about a bad day, or scream about how annoying your boss is. This will help you decompress in a healthy way, and stop those thoughts and feelings from overwhelming you. Upon reflection, you may realize that you have fewer reasons to be negative than you think. The goal is to better understand what’s driving your feelings and address those things — as opposed to avoid them — making you better equipped to move forward.

Turn a boring meeting into a learning opportunity.

Meetings are not always the most interesting use of time. Especially when you’re early in your career, you may be asked to sit in on meetings that feel like they have nothing to do with your role or responsibilities. Still, passive participation in these meetings ultimately helps no one. Even if you believe that a meeting doesn’t directly impact you or your career growth, there are easy way to use the time to your advantage. If you can do that, you can turn the meeting from “boring” to “rewarding,” and tap into your intrinsic motivation.

For instance, if you’re in a meeting that feels boring, don’t immediately check out. Instead, consider what you can learn from the other participants. If you’re watching another department present, pay attention to how they think, how they share information, and what they’re particularly good at. Ask yourself: How can I emulate that in my next team meeting to become a stronger presenter? How can I use this information to grow? Suddenly, you’ve turned a boring meetings into a learning opportunity. As a result, you’ll be more motivated to participate, pay attention, and learn something new.

. . .

Developing intrinsic motivation takes practice. Thankfully, once this process has begun and we start seeing the positive effects of our efforts, we’ll naturally start to reinforce these habits and techniques in our everyday life. Growth is an incredible motivator, which we must cultivate for ourselves. External rewards can only get us so far before they lose their appeal. Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, evolves with us as we grow and helps develop our own incentives to do great work.

0 notes

Text

Just wanted to share an excerpt from this article where Esteban talks a little about the Concours Excellence Mecanique competition of Alpine. This interview was done during the Alpine PR event held in Madrid last December.

#the article is behind a paywall but it's actually a really good read#i'll share more excerpts soon#the fact that Esteban is also a sponsor (either he contributes money or his services) of the competition really shows just how important#giving and providing opportunities like this are to him#opportunities that may not have been available to him back then#esteban ocon#eo31

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

You versus the guy she tells you not to worry about

#i did look this up a few hours after i reblogged that post yesterday(? or was it the other day) I DO BELIEVE IT'S SHELLEY#if only for the fact that it was for most of a century being identified as LEIGH HUNT instead! yeah right#that is not leigh hunt in 1822#i recommend googling the uva library article about it. it shows the full portrait which the telegraph does not in its preview#and that one is also behind a paywall so i couldn't even reeeead it#thank you university of virginia <3#it is not slacking for information btw. there's a forthcoming article by the person who propisitioned that this is shelley#i look forward to it#percy shelley#art#william edward west#romanticism#portraits#sorry amelia curran. your painting is still better than i could do#but i am feral at the thought of having such a professional likeness#THAT IS A REAL MAN BEFORE US#with such believable and realistic features#i want to believe#i know without a proper title given by the painter we'll never really know#but i a million times will accept this is shelley before i accept that the cobbe portrait is shakespeare lol#whenever i see that being published as shakespeare im like. sir. that's clearly thomas overbury#chandos portrait stans rise#sorry i dont often post about it but i am obsessed with likenesses of famous ppl especially disputed ones#especially disputed ones before the innovation or proliferation of photography!!! cuz wow!!!!

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

currently remembering that one time I needed a reference for a fanfiction I was writing and found a peer-reviewed paper about how grief affects children only it was locked behind a paywall so I emailed the author of the paper with my .edu email and said I was working on a project (which was technically true) and he emailed me the pdf for free

peace and love on planet earth

#tfw you're so into writing a fanfiction you're hitting up databases for peer reviewed articles#remember kids: people who actually care about your education don't hide resources behind exhorbitant paywalls#fanfiction#writing fanfic#fanfic#ao3#dark academia#academia#silly academia#<- me

43 notes

·

View notes