#retransitioners

Text

“but what if young people medically transition and then regret it?”

These people exist. Have you spoken to them and listened to their experiences and feelings?

Some of them are nonbinary. Some of them stop medically transitioning because it’s achieved what they wanted. Some of them realised they felt pressured to perform their gender and transness a specific way. Some of them realise they’re cis. Some of them are still trans, just in different ways. A great many of them have love and support for the trans community.

Are you actually interested in people’s lived experiences that are infinitely diverse and complex? Or are you just hoping to use people as props in your own transphobic arguments?

And if you do genuinely have concerns about this, look at a range of people’s stories and learn from them. Think critically about the source of your information, their evidence and credibility, and what their goals might be. And consider the alternatives. Research what happens when people don’t have access to medical transition. And compare your concerns to different medical interventions like tonsillectomies and non transgender cosmetic surgeries.

#Inspired by the musician June Henry (check out her work)#transgender#trans#detransitioners#retransitioners

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looked up the author of this story. Not surprised it’s by a TRA.

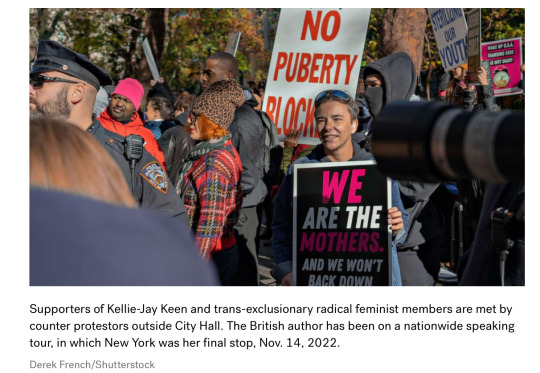

ByKiara Alfonseca

November 23, 2022, 6:30 AM

Ky Schevers is fighting back against the anti-trans movement she once took part in.

Schevers was assigned the sex of female at birth and later chose to start gender-affirming care by taking testosterone to transition from female to male in her mid-20s. She stopped taking testosterone, though, in the years that followed while she continued to explore and question her gender, later falling into an online anti-trans group of "detransitioners" – people who once did but no longer identify as transgender.

Now, Schevers says she has “retransitioned," identifying as transmasculine and gender queer, which means she identifies with both genders. Schevers uses she and her pronouns, but heavily identifies with masculinity, as defined by the LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center states.

She says she considers herself to be a part of the transgender community.

When Schevers initially stopped taking testosterone, she sought out advice and companionship in online forums about detransitioning. In this virtual community is where she began to adopt anti-trans beliefs that misogyny and a patriarchal society caused her to initially transition from female to male. In blog posts, YouTube videos, interviews and workshops, she spread and promoted these beliefs. These posts became a popular tool for anti-trans activists looking to discredit the trans community in the name of feminism.

A 50-year study in the Archives of Sexual Behavior performed in Sweden estimated that less than 3% of people who medically transitioned experienced "transition regret." Other studies have estimated similar results, some citing even lower figures.MORE: Amid anti-LGBTQ efforts, transgender community finds joy in 'chosen families'

Despite this low percentage, these individuals have become a focal point of anti-transgender legislation and activism.

More than 300 proposed bills across the country have targeted LGBTQ Americans in the last year, according to the Human Rights Campaign. Health care for trans youth in particular has become the target of such efforts.

Before the ages of 16-18, youth are treated with reversible treatments based on guidance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Irreversible medical interventions, such as surgeries, are typically only done with consenting adults, or older teens who have worked through the decision with their families and physicians over a long period of time, physicians across the country have told ABC News.

Despite these common practices, officials in many states have launched efforts to crack down on gender-affirming care for minors. Some legislators have cited disputed research on this topic, stating that the majority of gender dysphoric youth will grow out of their dysphoria. The methodology in these studies has been highly critiqued.

Major medical associations support gender-affirming care for youth and adults. Transgender youth tend to have high rates of suicide, but those who transition often experience significantly reduced psychological distress.

A recent large study from Harvard found that gender-affirming surgery was associated with improved mental health outcomes in those who are transgender.

Another recent large study from Harvard found that even among those who do go on to detransition, it is often due to external pressures such as stigma and non-acceptance in their environments, rather than a sudden resolution of gender dysphoria.

But that's where “detransitioners" come in. Detransitioned activists have often testified in public hearings on policies concerning the transgender community.

"I was 30 and at the end of my rope when I transitioned … If I made this mistake as an adult, a young girl could too," said one detransitioned speaker at the Oct. 28 Florida medical board hearing concerning a ban on gender affirming health care for youth. "Not only did my surgery exacerbate my mental health issues, I now struggle with physical complications as well."

Another speaker at the hearing, who said she started gender-affirming treatments at the age of 16 and regrets it, spoke about struggling with her mental health while transitioning. She urged the board to ban hormones for people under 18 and surgeries for people under 21. "In 2019, I had a life-changing encounter with Jesus and began to find deep healing within myself. After nearly 4 years of being on testosterone, I decided to detransition and accept my womanhood," she said.

The Florida Medical Board later passed a ban on gender-affirming care for youth. The decision would prohibit providers from administering gender affirming care, including puberty blockers, hormones, cross-hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery for people under the age of 18.MORE: Transgender youth health care ban approved by Florida medical boards

When Schevers was in similar circles, she said she tried to ignore her uncertainty about her gender and how it conflicted with the message she was promoting.

"I never liked people who call transitioning mutilation or call trans bodies mutilated...A lot of them called trans people delusional," Schevers said. "Living as a trans person was something that people did to survive and actually, I didn't think of it as crazy or irrational because I had lived that life."

She continued, "I get why someone would do this. Like, it did help me. I did get satisfaction from transitioning and I had to rationalize that experience and make it fit with this anti-trans ideology."

Schevers said cracks began to show in her beliefs as more of the detransitioners and other activists she worked with began to partner with far-right groups like the Proud Boys on an anti-trans platform.

"That was kind of a huge wake-up call," said Schevers. "It didn't make sense to ally with the people who were creating the oppressive conditions."

Her use of the hormone testosterone helped her embrace her gender queer identity, she now says.

When Schevers sees or hears anti-transgender detransitioners speak about their experiences, she thinks of her past self. She says she feels guilty, like she set the stage for them.

Schevers says she wants people to turn their attention to the dangers of anti-trans outreach to youth as well as the ongoing legislative attacks on trans Americans.

In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton also launched an effort to investigate gender-affirming youth care treatments as "child abuse" through the state department of child protective services. A state judge later issued a temporary injunction blocking the effort.

An Alabama law made it illegal to give any type of gender affirming care to anyone under the age of 18. This would criminalize parents and physicians.

Joseph Ladapo, Florida's surgeon general, released a memo in June saying treatments like sex-reassignment surgery, and hormone and puberty blockers are not effective treatments for gender dysphoria.MORE: Florida to ban gender-affirming care under Medicaid for transgender recipients

This memo contradicts guidance from organizations including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Public Health Association.

These organizations say that research does show that the aforementioned gender-affirming treatments are safe and effective. Some, like the American Medical Association, even deem it "medically necessary."

Gender exploration is an ongoing journey for Schevers, and she hopes the trans and gender queer youth in the U.S. continue to be able to access a journey of their own.

"I do feel more firmly rooted in who I am. It's easier for me to accept myself as someone who has, like, multiple genders," Schevers said.

Anyone else think she detransitioned and was treated horribly by the TRAs and faced regular misogyny from normies and figured it was just easier to go make to having a special identity?

#detransitioners#retransitioners#Biased reporting#Being critical of giving minors irreversible surgeries doesn’t make you anti-trans#Being concerned for women’s Rights doesn’t make you anti-trans#More framing women speaking up for causes important to them as angry harpies#ABC news

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

how are you shameless enough to claim to be a radical feminist while believing that in non-sexual contexts, coerced decisions should be treated as freely made choices, particularly in analytics?

"financial coercion? whatever, she made her choice. violent coercion? whatever, it was her choice.

"it was all her choice. the intentional limitations placed by either an individual, a set of individuals, or the system oppressing her have no place in consideration."

you aren't a feminist -- especially not a radical feminist. you refute fundamental feminist philosophy of coercion as nonconsent (with rape as the only exception). you deny materialism.

you're directly encouraging the sex data gap and its intended, ever-successful outcome of women's global economic exploitability with your statements in this very moment.

-

anyway book recommendation because this user is a reactionary contrarian who loudly and proudly refuses to read it: Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez.

#fake radfems#but sure -- I'm ''a TRA and encouraging women to transition'' for saying that more detransitioners' data should be included -- not just#non-desisted (intending future if not current) retransitioners and those who detransitioned by choice#I started a conversation with this user and then realized she literally thinks that coercion is consent if the context isn't sex#and is anti-considering systems of oppression#being anti-gender doesn't inherently mean you're a radfem#radical feminism isn't just ''anti-gender feminism'''

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's retrans I've never heard abt that

short for retransition! usually refers to those who may have detransitioned for a variety of reasons such as safety, changes in feelings, etc but do at another point come out again and "restart" their transition! even some who initially came out, say for instance, as a trans man but later comes out again as nonbinary may refer to themselves as retransitioning as their transness has not reverted or ceased, simply taken a different turn!

#hope this answers your question! and obv any people who wanna add to this feel free to bc i can only say so much because#while i dont see myself as this i was forcibly closeted even after coming out for many years so i am retransitioners number one supporter#love u all and also those who detransition and never retransition whether because you just wanted to detrans or its just not the right time#kiss kiss kiss#anon

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

im probably genderqueer but i have school so idc abt that rn

#i keep forgetting whether im a gnc trans man or a he/him straight woman or ftfemboy or w/e#or if im a retransitioner or agp trans man or transfem cis woman#or im a black cat straight up. like how boy cats n girl cats kinda look the same n gender doesnt rly matter as much to cats except for sex#uhh uhhhh#ummmmm#noo idont really know n its not on my list of priorities its just REALLY HARD to explain to cis people#< whichis only a thing bc trans health comes upin medical ethics#ok istopthinking abt this#im just a cat who use he/him pronouns n anything beyond that is shrug 👍#yap

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is me, 6 years off of testosterone (I was on Testosterone for 4 years beginning when I was 21 years old. These pictures are all from this month and also today lol.

#detransition#artists of tumblr#lgbtq#lgbt#youtube#artists on tumblr#transgender#trans#trans gamer#transgirl#transfeminine#genderqueer#nonbinary#retransitioner#stilltrans#retransition not detransition#Spotify

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot of radfems are destransitioners or desisters, so I wanted to poll to get an idea of how many!

For specificity, a desister is something who went from cis/non-trans to trans to cis/non-trans again, but did not start cross-sex HRT or surgeries. They may have went on hormone blockers.

A detransitioner is someone who went from cis/non-trans to trans to cis/non-trans again, and DID start cross-sex HRT and/or have surgeries.

A repersister is someone who desisted then went back to ID'ing as trans (but still has not had cross-sex HRT/surgeries).

A retransitioner is someone who desisted or detransitioned and later went back to ID'ing as trans (and has taken cross-sex HRT and/or had surgeries).

If anyone is curious, I'm a disister myself (FtNBtMtNBtF) 😊

#radblr#radical feminism#detrans#retrans#desisted#repersisted#radical feminist community#radical feminists do interact#radical feminist safe#rad fem#marxfem#radical polls#rad polls#radical feminist polls#radfem polls#radical feminist#trans issues#gender critical

121 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm so tired of how the current afab transfem discourse completely ignores multigender people, even though we are arguably one of the largest cohorts of people identify that way.

I am a trans man and a trans woman because I am trans and a man and a woman. I am a woman who is transgender. I am also a man who is transgender. I am an enby who is transgender. all at the same time.

our identities are also constantly delegitimised by people bemoaning the term "fagdyke" as a new fun thing for "theyfabs" to use for "slur collecting". like, hello? I'm simply a gay man and a gay woman.

I couldn't access or feel comfortable in my womanhood until I'd undergone medical transition. the same way i couldn't access or feel comfortable with my attraction to men until I was able to be seen as a queer man rather than a straight woman.

the only kind of womanhood i want is queer and trans, and I couldn't achieve this until I'd spent time living as a nonbinary man.

the term "ftmtf" has existed for a long time in use by detransitioners and retransitioners. there are a lot of people in these communities who describe experiences like mine, that they couldn't access womanhood until they'd experienced manhood.

I'm a trans manwoman. I'm a butch woman and a femme man. these are two very distinct genders I experience.

I also have DID, and have transfem system members who live in an "afab" body. do they not get to have terms to describe their experience? do they not get to be whole people in the way that our transmasc headmates do?

sorry for the long rant. I just needed to collect my thoughts, and I value your opinion on these topics. I hope you're havin a good day. shout out to the VELVET NATION for being cool as hell.

They've just been throwing it all under the bus as "theyfabs trying to maliciously hide the fact that they're AFAB by identifying as a special snowflake gender".

Mainstream gender discourse is still a ways off from taking systems into account, I think, although we can easily predict what the response will be by simply thinking of the worst, dumbest, most actively take one could have on the subject. I'd love for them to take a crack at two of our members who they'll surely be happy to use as the excuse they need to discount our opinions on transfeminism and fakeclaim us despite the fact that the body is perisex and AMAB - if our singlet gender isn't already too weird for them, which I'm sure it would be if we rolled up to a queer function with our arms covered in a thick forest of hair and a chin just freshly shaven.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

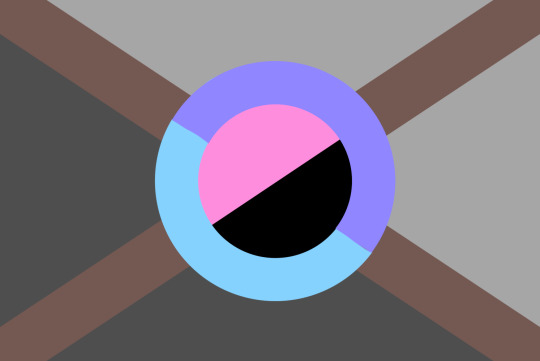

[ID: A flag that is crossed through the angles with a brown X, with a purple and cyan ring in the center that is split in half to be pink and black. The outside of the flag is split into black and grey. End ID]

Binary Abolitionist

A stance where one aims to abolish every sex and gender binary. This includes male/female, amab/afab, trans/cis, and eventually, binary/abinary. It believes that binaries only aim to divide us and none of the components of the binaries previously listed are truly opposites.

This stance is staunchly in support of intersex individuals, altersex individuals, multigender individuals, tris individuals, and anyone else harmed by binarist ideology. This stance is very against radical feminism and very against antifeminism.

Another key component of this stance is AGABpunk, and this stance believes that AGAB is nothing more than what a doctor said you were once. Binary abolitionists believe AGAB labels are basically useless except for explaining intersex experiences.

This stance is notably pro-bodily autonomy, especially when it comes to gender-affirming care. Binary abolitionists are very in support of top surgery without bottom surgery (and vise versa), genital nullification, salmacian surgeries, altersex surgeries, cis individuals getting gender-affirming care, trans individuals who do not get any sort of gender-affirming care, etc. This also includes being very in support of detransitioners and retransitioners.

Lastly, binary abolitionists call out things like intersexism whenever possible. This includes calling out those who claim to be "transintersex" and correcting intersexist misinformation (eg. people saying animals are "biologically nonbinary" when they are actually intersex, people saying kids never forcibly get sex-reassignment when, in fact, intersex kids do, etc.)

@radiomogai @liom-archive

#max squawks#might add more later but here#binary abolition#anti radfem#intersectionality#intersex#actually intersex#anarcho queer#queer anarchism#multigender#intersexism#transmultiphobia#exorsexism#transphobia#bigender#nonbinary#genderqueer#genderfluid#gender nonconforming#gnc#trigender#agabpunk#liomogai#liom#mogai#critinclus#inclusionism#inclusion#inclusivity

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

volition is here for the detransitioners, retransitioners, genderfluid, and otherwise inexpressibles

#fatt#palisade#i have never really gone in for a divinesona but honestly whatever volition is understands me

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love all my retransitioners out there with all my heart. But I don't know if the term is that all-encompassing - there's a significant portion of people who had to reverse/stop their transition because of outside forces, because of medical reasons, because they had to back into the closet for safety, because of trauma, because of the oppression transgender people face every day.

I don't think it's helpful to just throw away a term like detransitioner because you personally like a newer term better (talking about using the word to label other people) - I am a detransitioner, I have been booted out of the trans medical system for not conforming and being mentally ill, I am not somebody who is okay with being called a retransitioner. I didn't choose to transition again and find a new stage in life, it is not a happy journey for me. Once again it comes down to personal choice, just don't tell people what words to use for themselves.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love you detransitioners and retransitioners. I love you FtMtF’s and MtFtM’s. I love you binary to nonbinary and nonbinary to binary. I love you lifelong genderfluids with long periods of each. I love you systems and plurals with complicated relationships to gender and transitioning. You’re all wonderful and I hope you have fantastic days.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

i do not think references to "retransitioning" as a way of describing one's personal experience are inherently harmful in the way an afab de/retransitioner referring to herself as a "trans woman" is, though they might arise from and refer to the same set of circumstances. neither are terms like "ftmtf" or "mtftm". "detrans/retrans woman" would probably do the job just fine as well.

does one inherently enable the other? i do not want to be tyrannical or restrictive about language, so my inclination is to say "no". but at some point, the wires seem to get crossed and the leap is made. can i trust my judgment?

how can we translate all this waffling on about words into something actionable? how do we combat something like this on a material level? many questions, few conclusions yet.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't see how anyone who truly sees how gender is nothing but performance of gender roles can latch onto a gender identity, but then again there are radfems who convert to christianity 🤷♀️. It may be easier for that retransitioner to see herself as ftm depending on her social circle. Challenging gender is hard and women's rights are going backwards so sometimes giving in to fitting in feels okay.

In my honest opinion, it sounds like she never really left her gendie beliefs. She literally calls being a butch woman a gender identity lmao. It seems like a religious person choosing a different religion and then going back to their original one. Like. The beliefs never changed. Even in the example you have of radfems converting to Christianity, WERE they radfems? Or did they just realize that gender is bullshit and thought they HAD to be radfems based off of that, but realized they weren't rads at all? Did they ever stop wearing make up? Did they ever become truly critical of men? Calling yourself something doesn't mean that you are.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

About me -

33 ftxtftxtm - 2 years on, 10 years off, 1 year on T 3/3/23. Retransitioner.

He/him "binary" male - GNC, Gay

2.5" preop meta. Top in April 24

my posts under #mine

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Jennifer Block

Published: Feb 23, 2023

More children and adolescents are identifying as transgender and are being offered medical treatment, especially in the US—but some providers and European authorities are urging caution because of a lack of strong evidence. Jennifer Block reports

Last October the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) gathered inside the Anaheim Convention Center in California for its annual conference. Outside, several dozen people rallied to hear speakers including Abigail Martinez, a mother whose child began hormone treatment at age 16 and died by suicide at age 19. Supporters chanted the teen’s given name, Yaeli; counter protesters chanted, “Protect trans youth!” For viewers on a livestream, the feed was interrupted as the two groups fought for the camera.

The AAP conference is one of many flashpoints in the contentious debate in the United States over if, when, and how children and adolescents with gender dysphoria should be medically or surgically treated. US medical professional groups are aligned in support of “gender affirming care” for gender dysphoria, which may include gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa) to suppress puberty; oestrogen or testosterone to promote secondary sex characteristics; and surgical removal or augmentation of breasts, genitals, or other physical features. At the same time, however, several European countries have issued guidance to limit medical intervention in minors, prioritising psychological care.

The discourse is polarised in the US. Conservative politicians, pundits, and social media influencers accuse providers of pushing “gender ideology” and even “child abuse,” lobbying for laws banning medical transition for minors. Progressives argue that denying access to care is a transphobic violation of human rights. There’s little dispute within the medical community that children in distress need care, but concerns about the rapid widespread adoption of interventions and calls for rigorous scientific review are coming from across the ideological spectrum.

The surge in treatment of minors

More adolescents with no history of gender dysphoria—predominantly birth registered females—are presenting at gender clinics. A recent analysis of insurance claims by Komodo Health found that nearly 18 000 US minors began taking puberty blockers or hormones from 2017 to 2021, the number rising each year. Surveys aiming to measure prevalence have found that about 2% of high school aged teens identify as “transgender.” These young people are also more likely than their cisgender peers to have concurrent mental health and neurodiverse conditions including depression, anxiety, attention deficit disorders, and autism.6 In the US, although Medicaid coverage varies by state and by treatment, the Biden administration has warned states that not covering care is in violation of federal law prohibiting discrimination. Meanwhile, the number of private clinics that focus on providing hormones and surgeries has grown from just a few a decade ago to more than 100 today.

As the number of young people receiving medical transition treatments rises, so have the voices of those who call themselves “detransitioners” or “retransitioners,” some of whom claim that early treatment caused preventable harm. Large scale, long term research is lacking, and researchers disagree about how to measure the phenomenon, but two recent studies suggest that as many as 20-30% of patients may discontinue hormone treatment within a few years. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) asserts that detransition is “rare.”

Chloe Cole, now aged 18, had a double mastectomy at age 15 and spoke at the AAP rally. “Many of us were young teenagers when we decided, on the direction of medical experts, to pursue irreversible hormone treatments and surgeries,” she read from her tablet at the rally, which had by this time moved indoors to avoid confrontation. “This is not informed consent but a decision forced under extreme duress.”

Scott Hadland, chief of adolescent medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, dismissed the “handful of cruel protesters” outside the AAP meeting in a tweet that morning. He wrote, “Inside 10 000 pediatricians stand in solidarity for trans & gender diverse kids & their families to receive evidence-based, lifesaving, individualized care.”

Same evidence, divergent recommendations

Three organisations have had a major role in shaping the US’s approach to gender dysphoria care: WPATH, the AAP, and the Endocrine Society (see box). On 15 September 2022 WPATH published the eighth edition of its Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, with new chapters on children and adolescents and no minimum age requirements for hormonal and surgical treatments. GnRHa treatment, says WPATH, can be initiated to arrest puberty at its earliest stage, known as Tanner stage 2.

The Endocrine Society also supports hormonal and surgical intervention in adolescents who meet criteria in clinical practice guidelines published in 2009 and updated in 2017. And the AAP’s 2018 policy statement, Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents, says that “various interventions may be considered to better align” a young person’s “gender expression with their underlying identity.” Among the components of “gender affirmation” the AAP names social transition, puberty blockers, sex hormones, and surgeries. Other prominent professional organisations, such as the American Medical Association, have issued policy statements in opposition to legislation that would curtail access to medical treatment for minors.

These documents are often cited to suggest that medical treatment is both uncontroversial and backed by rigorous science. “All of those medical societies find such care to be evidence-based and medically necessary,” stated a recent article on transgender healthcare for children published in Scientific American. “Transition related healthcare is not controversial in the medical field,” wrote Gillian Branstetter, a frequent spokesperson on transgender issues currently with the American Civil Liberties Union, in a 2019 guide for reporters. Two physicians and an attorney from Yale recently opined in the Los Angeles Times that “gender-affirming care is standard medical care, supported by major medical organizations . . . Years of study and scientific scrutiny have established safe, evidence-based guidelines for delivery of lifesaving, gender-affirming care.” Rachel Levine, the US assistant secretary for health, told National Public Radio last year regarding such treatment, “There is no argument among medical professionals.”

Internationally, however, governing bodies have come to different conclusions regarding the safety and efficacy of medically treating gender dysphoria. Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare, which sets guidelines for care, determined last year that the risks of puberty blockers and treatment with hormones “currently outweigh the possible benefits” for minors. Finland’s Council for Choices in Health Care, a monitoring agency for the country’s public health services, issued similar guidelines, calling for psychosocial support as the first line treatment. (Both countries restrict surgery to adults.)

Medical societies in France, Australia, and New Zealand have also leant away from early medicalisation. And NHS England, which is in the midst of an independent review of gender identity services, recently said that there was “scarce and inconclusive evidence to support clinical decision making” for minors with gender dysphoria and that for most who present before puberty it will be a “transient phase,” requiring clinicians to focus on psychological support and to be “mindful” even of the risks of social transition.

“Don’t call them evidence based”

“The brief history of guidelines is that, going back more than 30 years ago, experts would write articles and so on about what people should do. But formal guidelines as we think of them now were seldom or non-existent,” says Gordon Guyatt, distinguished professor in the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact at McMaster University, Ontario.

That led to the movement towards developing criteria for what makes a “trustworthy guideline,” of which Guyatt was a part. One pillar of this, he told The BMJ, is that they “are based on systematic review of the relevant evidence,” for which there are also now standards, as opposed to a traditional narrative literature review in which “a bunch of experts write whatever they felt like using no particular standards and no particular structure.”

Mark Helfand, professor of medical informatics and clinical epidemiology at Oregon Health and Science University, says, “An evidence based recommendation requires two steps.” First, “an unbiased, thorough, critical systematic review of all the relevant evidence.” Second, “some commitment to link the strength of the recommendations to the quality of the evidence.”

The Endocrine Society commissioned two systematic reviews for its clinical practice guideline, Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: one on the effects of sex steroids on lipids and cardiovascular outcomes, the other on their effects on bone health. To indicate the quality of evidence underpinning its various guidelines, the Endocrine Society employed the GRADE system (grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation) and judged the quality of evidence for all recommendations on adolescents as “low” or “very low.”

Guyatt, who co-developed GRADE, found “serious problems” with the Endocrine Society guidelines, noting that the systematic reviews didn’t look at the effect of the interventions on gender dysphoria itself, arguably “the most important outcome.” He also noted that the Endocrine Society had at times paired strong recommendations—phrased as “we recommend”—with weak evidence. In the adolescent section, the weaker phrasing “we suggest” is used for pubertal hormone suppression when children “first exhibit physical changes of puberty”; however, the stronger phrasing is used to “recommend” GnRHa treatment.

“GRADE discourages strong recommendations with low or very low quality evidence except under very specific circumstances,” Guyatt told The BMJ. Those exceptions are “very few and far between,” and when used in guidance, their rationale should be made explicit, Guyatt said. In an emailed response, the Endocrine Society referenced the GRADE system’s five exceptions, but did not specify which it was applying.

Helfand examined the recently updated WPATH Standards of Care and noted that it “incorporated elements of an evidence based guideline.” For one, WPATH commissioned a team at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland to conduct systematic reviews.3435 However, WPATH’s recommendations lack a grading system to indicate the quality of the evidence—one of several deficiencies. Both Guyatt and Helfand noted that a trustworthy guideline would be transparent about all commissioned systematic reviews: how many were done and what the results were. But Helfand remarked that neither was made clear in the WPATH guidelines and also noted several instances in which the strength of evidence presented to justify a recommendation was “at odds with what their own systematic reviewers found.”

For example, one of the commissioned systematic reviews found that the strength of evidence for the conclusions that hormonal treatment “may improve” quality of life, depression, and anxiety among transgender people was “low,” and it emphasised the need for more research, “especially among adolescents.” The reviewers also concluded that “it was impossible to draw conclusions about the effects of hormone therapy” on death by suicide.

Despite this, WPATH recommends that young people have access to treatments after comprehensive assessment, stating that the “emerging evidence base indicates a general improvement in the lives of transgender adolescents.” And more globally, WPATH asserts, “There is strong evidence demonstrating the benefits in quality of life and well-being of gender-affirming treatments, including endocrine and surgical procedures,” procedures that “are based on decades of clinical experience and research; therefore, they are not considered experimental, cosmetic, or for the mere convenience of a patient. They are safe and effective at reducing gender incongruence and gender dysphoria.”

Those two statements are each followed by more than 20 references, among them the commissioned systematic review. This stood out to Helfand as obscuring which conclusions were based on evidence versus opinion. He says, “It’s a very strange thing to feel that they had to cite some of the studies that would have been in the systematic review or purposefully weren’t included in the review, because that’s what the review is for.”

For minors, WPATH contends that the evidence is so limited that “a systematic review regarding outcomes of treatment in adolescents is not possible.” But Guyatt counters that “systematic reviews are always possible,” even if few or no studies meet the eligibility criteria. If an entity has made a recommendation without one, he says, “they’d be violating standards of trustworthy guidelines.” Jason Rafferty, assistant professor of paediatrics and psychiatry at Brown University, Rhode Island, and lead author of the AAP statement, remarks that the AAP’s process “doesn’t quite fit the definition of systematic review, but it is very comprehensive.”

Sweden conducted systematic reviews in 2015 and 2022 and found the evidence on hormonal treatment in adolescents “insufficient and inconclusive.”24 Its new guidelines note the importance of factoring the possibility that young people will detransition, in which case “gender confirming treatment thus may lead to a deteriorating of health and quality of life (i.e., harm).”

Cochrane, an international organisation that has built its reputation on delivering independent evidence reviews, has yet to publish a systematic review of gender treatments in minors. But The BMJ has learnt that in 2020 Cochrane accepted a proposal to review puberty blockers and that it worked with a team of researchers through 2021 in developing a protocol, but it ultimately rejected it after peer review. A spokesperson for Cochrane told The BMJ that its editors have to consider whether a review “would add value to the existing evidence base,” highlighting the work of the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which looked at puberty blockers and hormones for adolescents in 2021. “That review found the evidence to be inconclusive, and there have been no significant primary studies published since.”

In 2022 the state of Florida’s Agency for Health Care Administration commissioned an overview of systematic reviews looking at outcomes “important to patients” with gender dysphoria, including mental health, quality of life, and complications. Two health research methodologists at McMaster University carried out the work, analysing 61 systematic reviews and concluding that “there is great uncertainty about the effects of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries in young people.” The body of evidence, they said, was “not sufficient” to support treatment decisions.

Calling a treatment recommendation “evidence based” should mean that a treatment has not just been systematically studied, says Helfand, but that there was also a finding of high quality evidence supporting its use. Weak evidence “doesn’t just mean something esoteric about study design, it means there’s uncertainty about whether the long term benefits outweigh the harms,” Helfand adds.

“Evidence itself never tells you what to do,” says Guyatt. That’s why guidelines must make explicit the values and preferences that underlie the recommendation.

The Endocrine Society acknowledges in its recommendations on early puberty suppression that it is placing “a high value on avoiding an unsatisfactory physical outcome when secondary sex characteristics have become manifest and irreversible, a higher value on psychological well-being, and a lower value on avoiding potential harm.”

WPATH acknowledges that while its latest guidelines are “based upon a more rigorous and methodological evidence-based approach than previous versions,” the evidence “is not only based on the published literature (direct as well as background evidence) but also on consensus-based expert opinion.” In the absence of high quality evidence and the presence of a patient population in need—who are willing to take on more personal risk—consensus based guidelines are not unwarranted, says Helfand. “But don’t call them evidence based.”

An evidence base under construction

In 2015 the US National Institutes of Health awarded a $5.7m (£4.7m; €5.3m) grant to study “the impact of early medical treatment in transgender youth.” The abstract submitted by applicants said that the study was “the first in the US to evaluate longitudinal outcomes of medical treatment for transgender youth and will provide essential evidence-based data on the physiological and psychosocial effects and safety” of current treatments. Researchers are following two groups, one of participants who began receiving GnRHa in early puberty and another group who began cross sex hormone treatment in adolescence. The study doesn’t include a concurrent no-treatment control group.

Robert Garofalo, chief of adolescent medicine at the Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago and one of four principal investigators, told a podcast interviewer in May 2022 that the evidence base remained “a challenge . . . it is a discipline where the evidence base is now being assembled” and that “it’s truly lagging behind [clinical practice], I think, in some ways.” That care, he explained, was “being done safely. But only now, I think, are we really beginning to do the type of research where we’re looking at short, medium, and long term outcomes of the care that we are providing in a way that I think hopefully will be either reassuring to institutions and families and patients or also will shed a light on things that we can be doing better.”

While Garofalo was doing the research he served as “contributor” on the AAP’s widely cited 2018 policy statement, which recommends that children and adolescents “have access to comprehensive, gender-affirming, and developmentally appropriate health care,” including puberty blockers, sex hormones, and, on a case-by-case basis, surgeries.

Garofalo said in the May interview, “There is universal support for gender affirming care from every mainstream US based medical society that I can think of: the AMA, the APA, the AAP. I mean, these organisations never agree with one another.” Garofalo declined an interview and did not respond to The BMJ’s requests for comment.

The rush to affirm

Sarah Palmer, a paediatrician in private practice in Indiana, is one of five coauthors of a 2022 resolution submitted to the AAP’s leadership conference asking that it revisit the policy after “a rigorous systematic review of available evidence regarding the safety, efficacy, and risks of childhood social transition, puberty blockers, cross sex hormones and surgery.” In practice, Palmer told The BMJ, clinicians define “gender affirming” care so broadly that “it’s been taken by many people to mean go ahead and do anything that affirms. One of the main things I’ve seen it used for is masculinising chest surgery, also known as mastectomy in teenage patients.” The AAP has told The BMJ that all policy statements are reviewed after five years and so a “revision is under way,” based on its experts’ own “robust evidence review.”

Palmer says, “I’ve seen a quick evolution, from kids with a very rare case of gender dysphoria who were treated with a long course of counselling and exploration before hormones were started,” to treatment progressing “very quickly—even at the first visit to gender clinic—and there’s no psychologist involved anymore.”

Laura Edwards-Leeper, a clinical psychologist who worked with the endocrinologist Norman Spack in Boston and coauthored the WPATH guidelines for adolescents, has observed a similar trend. “More providers do not value the mental health component,” she says, so in some clinics families come in and their child is “pretty much fast tracked to medical intervention.” In a study of teens at Seattle Children’s Hospital’s gender clinic, two thirds were taking hormones within 12 months of the initial visit.

The British paediatrician Hilary Cass, in her interim report of a UK review into services for young people with gender identity issues, noted that some NHS staff reported feeling “under pressure to adopt an unquestioning affirmative approach and that this is at odds with the standard process of clinical assessment and diagnosis that they have been trained to undertake in all other clinical encounters.”

Eli Coleman, lead author of WPATH’s Standards of Care and former director of the Institute for Sexual and Gender Health at the University of Minnesota, told The BMJ that the new guidelines emphasised “careful assessment prior to any of these interventions” by clinicians who have appropriate training and competence to assure that minors have “the emotional and cognitive maturity to understand the risks and benefits.” He adds, “What we know and what we don’t know has to be explained to youth and their parents or caregivers in a balanced way which really details that this is the evidence that we have, that we obviously would like to have more evidence, and that this is a risk-benefit scenario that you have to consider.”

Joshua Safer, director of the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York and coauthor of the Endocrine Society guidelines, told The BMJ that assessment is standard practice at the programme he leads. “We start with a mental health evaluation for anybody under the age of 18,” he says. “There’s a lot of talking going on—that’s a substantial element of things.” Safer has heard stories of adolescents leaving a first or second appointment with a prescription in hand but says that these are overblown. “We really do screen these kids pretty well, and the overwhelming majority of kids who get into these programmes do go on to other interventions,” he says.

Without an objective diagnostic test, however, others remain concerned. The demand for services has led to a “perfunctory informed consent process,” wrote two clinicians and a researcher in a recent issue of the Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, in spite of two key uncertainties: the long term impacts of treatment and whether a young person will persist in their gender identity. And the widespread impression of medical consensus doesn’t help. “Unfortunately, gender specialists are frequently unfamiliar with, or discount the significance of, the research in support of these two concepts,” they wrote. “As a result, the informed consent process rarely adequately discloses this information to patients and their families.”

For Guyatt, claims of certainty represent both the success and failure of the evidence based medicine movement. “Everybody now has to claim to be evidence based” in order to be taken seriously, he says—that’s the success. But people “don’t particularly adhere to the standard of what is evidence based medicine—that’s the failure.” When there’s been a rigorous systematic review of the evidence and the bottom line is that “we don’t know,’” he says, then “anybody who then claims they do know is not being evidence based.”

--

Sidebar:

The origins of paediatric gender medicine in the United States

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) began as a US based advocacy group and issued the first edition of the Standards of Care in 1979, when it was serving a small population of mostly adult male-to-female transsexuals. “WPATH became the standard because there was nobody else doing it,” says Erica Anderson, a California based clinical psychologist and former WPATH board member. The professional US organisations that lined up in support “looked heavily to WPATH and the Endocrine Society for their guidance,” she told The BMJ.

The Endocrine Society’s guidance for adolescents grew out of clinicians’ research in the Netherlands in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Peggy Cohen-Kettenis, a Utrecht gender clinic psychologist, collaborated with endocrinologists in Amsterdam, one of whom had experience of prescribing gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues, relatively new at the time. Back then, gender dysphoric teens had to wait until the age of majority for sex hormones, but the team proposed that earlier intervention could benefit carefully selected minors.

The clinic treated one natal female patient with triptorelin, published a case study and feasibility proposal, and began treating a small number of children at the turn of the millennium. The Dutch Protocol was published in 2006, referring to 54 children whose puberty was being suppressed and reporting preliminary results on the first 21. The researchers received funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of triptorelin.

In 2007 the endocrinologist Norman Spack began using the protocol at Boston Children’s Hospital and joined Cohen-Kettenis and her Dutch colleagues in writing the Endocrine Society’s first clinical practice guideline. When that was published in 2009, puberty had been suppressed in just over 100 gender dysphoric young people.

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) committee members began discussing the need for a statement in 2014, four years before publication, says Jason Rafferty, assistant professor of paediatrics and psychiatry at Brown University, Rhode Island, and the statement’s lead author. “The AAP recognised that it had a responsibility to provide some clinical guidance, but more importantly to come out with a statement that said we need research, we need to integrate the principles of gender affirmative care into medical education and into child health,” he says. “What our policy statement is not meant to be is a protocol or guidelines in and of themselves.”

==

Claiming it's "evidence-based" doesn't mean it's good evidence.

#Jennifer Block#pediatric transition#gender ideology#queer theory#medical transition#medical malpractice#medical scandal#medical corruption#gender affirming#affirmation model#affirmation#affirmative therapy#puberty blockers#wrong sex hormones#cross sex hormones#religion is a mental illness

18 notes

·

View notes