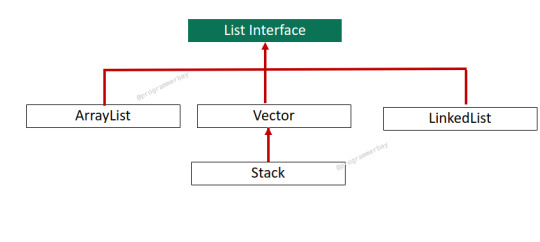

#Hierarchy in Collection Framework

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ArrayList Class in Java With Program Example

Arraylist is a child class of AbstractList and implements List interface. It represents dynamic array that can grow or shrink as needed. In case of standard array, one must know the number of elements about to store in advance. In other words, a standard array is fixed in size and its size can’t be changed after its initialisation. To overcome this problem, collection framework provides…

View On WordPress

#arraylist#collection#collection framework#Hierarchy in Collection Framework#java#java program#List interface

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Species Anarchy

species anarchy \ˈspē-shēz ˌa-nər-kē\

noun

Compound of species (from Latin speciēs, which has 10 known definitions (including “point of view” and “perspective”), and anarchy (from Greek ἀναρχίᾱ (anarkhíā), "lack of a leader"). Coined in 2025 by Khanty shaman Erenky Iyukhan to critique taxonomic rigidity and biological essentialism.

A philosophical and ideological stance acknowledging the ambiguity of taxonomic categories (e.g., Homo sapiens or "human") as socially constructed, biologically fluid, and lacking universal definition. Emphasizes that such classifications are conceptual inventions designed to categorize the natural world, as well as forcefully impose order on nature, rather than objective truths, thus stifling individuality and communal growth.

It is the rejection of externally imposed species labels in favor of self-identification based on an individual’s perceived genetic, morphological, or existential reality. Adherents of species anarchy may identify outside the genus Homo, asserting autonomy over their biological classification. For some people, it may be important to them to label the history of their personal evolution; this may not be as important for others.

Relation to Alterhuman and Otherkind/kin Communities

Species anarchy intersects with alterhuman and otherkin frameworks, which reject anthropocentric identity norms. Alterhumanity encompasses identities that transcend or reject conventional definitions of humanity (otherkin, therians, or fictionkin), often rooted in spiritual, psychological, or neurodivergent experiences of non-humanness. Similarly, species anarchists critique the authority of scientific taxonomy to define species boundaries, arguing that self-determined biological or existential identities are equally valid.

While alterhumanity focuses on personal identity and lived experience, species anarchy can be a philosophical, cultural, psychological, religious, and/or generally personal belief. It is simultaneously a political critique on systemic structures, such as the Linnaean hierarchy or bioethical policies. Both frameworks challenge bioessentialism, but species anarchy emphasizes collective liberation from taxonomic hegemony as a fundamental belief.

For example, an otherkin person identifying as a wolf might reject the identification of Homo sapiens as a mandatory category, creating an entirely new taxonomic label for their individual biology, viewing their self-speciation as biological evidence of their wolf identity, as well as a personal truth and a political act against biological determinism.

#species anarchy#otherkind#otherkin#alterhuman#fictionkind#fictionkin#philosophy#anti bioessentialism#self speciation#definitions#etymology#alterhuman terms#otherkin terms#otherkin term#alterhuman term#term coining

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

System alternatives - general. P1

Archive , Arrangement , Apparatus , Administration , Array , Alliance , Actors , Affiliates , Affiliation , Associates , Association , Armada , Abbey ,

Band , Bunch , Branch , Battalion , Bevy , Bind , Bounty , Brand , Board , Brotherhood ,

Collective , Company , Compound , Church , Choir , Cast , Complex , Crew , Corps , Collaboration , Commune , Community , Communal , Concert , Coalition , Camp , Crowd , Club , Creed , Chapel .

Dominion , Domain , Dorm ,

Framework , Faculty , Force , Faction , Function , Fleet , Fellowship , Fraternity , Faith ,

Group , Gang , Gaggle , Gathered , Gathering , Grouping , Guild , Guard , Govern / Goverment ,

Hive , Horde / Hoard , Hierarchy , House , Home , Hurd / Herd ,

Institute ,

Lineup , Legeon , League , Lot ,

Mob , Mates , Mosque , Ministry , Military ,

Network ,

Organization , Order , Ones , Office , Oficials , Observatory ,

Party , Posse , Pack , Pride , Pantheon , Polycule ,

Realm

Structure , School , Stage , Squad / Squadron , Set , Staff , Swarm , Show , Ship , Society , Sorority , Sect , Sanctuary , Shrine , Synagogue , Sisterhood / Systerhood ,

Team , Troup / Troop / Troupe , Temple , Treehouse ,

Unit , Universe , Union ,

World ,

Please remember to read the store policy!

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Socialism, from an Anarchist

Socialism is more than just an economic system—it’s a political philosophy rooted in collective ownership and democratic control over resources and the means of production: land, infrastructure, factories, and beyond. It prioritizes meeting people’s needs over profit and aims to dismantle systems that concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a few. Central to socialism is solidarity—not as a transactional exchange, but as a commitment to care for one another, especially when someone can’t “give back.” As Marx put it, “From each according to their ability, to each according to their need.” In a truly socialist framework, people deserve housing, food, healthcare, and dignity—not because they’ve earned it, but because they’re human.

Mutual aid reflects this spirit—neighbors supporting one another without bureaucratic gatekeeping—but it alone isn’t enough. It must be part of a broader strategy to transform the systems that create scarcity and harm in the first place.

I used to believe that organizing alongside others who claimed to share these values meant I would be treated with the same care and solidarity I offered. I was wrong. After a covert operation left me unable to work or be “productive,” I was targeted rather than supported. My inability to “give back” was scrutinized and weaponized as justification to alienate me. And despite all the mutual aid I had consistently offered—often at personal cost—it was never extended in return.

It wasn’t just a personal betrayal—it was a collective failure. A community that claimed to stand for justice acted instead out of self-interest, control, and cowardice.

Socialist values are not abstract. They’ve been applied in real-world structures, like worker cooperatives rooted in egalitarianism, shared ownership, democratic decision-making, and fair distribution of labor and profit. These are tangible ways to live out the principles we claim to believe in. But the group I was in failed to uphold any of that. Despite identifying as socialists and showing support and understanding for others who struggled or needed accommodations, when I needed time away—after a long and dangerous series of events—they suddenly operated with a deeply capitalistic mindset: obsessed with productivity, reliant on punitive logic around conflict without examining the conditions that led to it, and quick to discard those they could no longer benefit off of.

Worse still, a director in that group who claimed to be a socialist openly idealized authoritarianism. They invoked Stalin as a model of leadership and adopted top-down management styles rooted in intimidation and control—not collaboration or care. Dissent was punished. Dignity was denied. These tactics alienated not just me, but many who might have been allies.

While I stood for anarchism and self-managed, stateless forms of solidarity, I’m no longer convinced that anyone in that group ever truly embodied socialist values. The disconnect between their rhetoric and their actions exposed the hollowness of their politics. It made one thing clear: claiming socialism means nothing if your practice replicates the very hierarchies and violence we’re supposed to be fighting.

#socialism#leftism#marxism#karl marx#capitalism#anarchism#anticapitalism#anarchocommunism#revolution#solidarity

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anselm Kiefer :: The Hierarchy of the Angels (Die Ordnung der Engel) 2000 Oil, emulsion, shellac, and linen clothes on canvas 950 x 510 cm Collection of the artist

* * * *

“Into this wild Abyss/ The womb of Nature, and perhaps her grave–/ Of neither sea, nor shore, nor air, nor fire,/ But all these in their pregnant causes mixed/ Confusedly, and which thus must ever fight,/ Unless the Almighty Maker them ordain/ His dark materials to create more worlds,–/ Into this wild Abyss the wary Fiend/ Stood on the brink of Hell and looked a while,/ Pondering his voyage; for no narrow frith/ He had to cross.”

― John Milton, Paradise Lost

+

“Creatives have reputations for floating in unreality. It’s true that what they espouse hints of magic and mystery, having little to do with what the larger world calls real. People like [this] are labeled ‘hermit,’ ‘madman,’ ‘eccentric.’ Because they don’t live as others live, or accept the routine that makes the world go round, they are blamed, ridiculed, barely accepted as members of society. They are driven […] to greater extremes and further isolation, and rarely helped to do what they are born to do. Some do it anyway, and anyone who doubts the groundedness necessary for such a life should try it. To face each day supported, not by the dictates of a reliable outer framework, but by a chosen obedience to an inner necessity, one has to have one’s feet on the ground.”

— Leif Anderson, from “Grounded,” Dancing with My Father (University Press of Mississippi, 2005)

+

A bird calls announcing the difference between heaven and hell.

~ Dogen Zenji

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

✍️ Digging Tunnels with Pens: Anonymous Publishing as Intellectual Resistance by Aziz Yafi, published in the blog of the Institute for Palestine Studies

"By embracing clandestine publishing, we reject the commodification of knowledge and the constraints of Western individualism. We center the collective over the individual, the struggle over the author. This strategy, borrowed from revolutionary movements across history, allows us to bypass the structures that seek to censor and punish us, creating spaces for radical ideas to thrive and circulate beyond the confines of institutional power.

Resisting the commodification of knowledge also requires resisting novelty. Clandestine writing does not necessarily have to be new. It can also involve the revisiting of revolutionary ideas from the past and archival sources that have been suppressed by the passage of time and institutional power hierarchies — returning revolutionary knowledge to our collective struggle.

Ultimately, we must recognize that our energies are better spent outside the academy, and in strategically extracting its resources to fuel our anti-colonial work elsewhere. It is time to return to the archives of insurgent knowledge, revive the revolutionary spirit of past movements, and produce knowledge that resists (self) censorship and affirms the struggle for Palestinian liberation by all means necessary.

In times of intensified repression, clandestine publishing becomes a necessity and a vital form of intellectual and political survival. As censorship tightens, we must draw from history, learn from past movements, and rely on one another to keep the flame of resistance burning. This is not a call to abandon the academic space entirely, but to master the art of navigating both worlds –— maintaining our presence within institutional frameworks while never losing sight of the collective struggle. To go underground as academics means to learn from the endurance of Palestinian resistance, the steadfastness of Gaza, and the struggle of Palestinian prisoners. It is a call to learn rather than teach, to apply knowledge rather than extract it.

The tunnels dug by Palestinian prisoners with spoons, and those created by Gaza's resistance, symbolize a reorientation of our approach — teaching us to think not just laterally but vertically, subverting spatial barriers and borders. These tunnels remind us to delve into our collective history of knowledge production, to republish what has been buried or scattered in lost archives, and to make accessible what's been withheld by institutional gatekeepers. Doing so teaches us to reject the Western capitalist drive for constant novelty, which seeks to erase the wisdom of militant generations before us. The words of those who were often assassinated for their ideas remain alive.

To learn from Palestinian resistance is to carve and dig escape tunnels from academia's mental production lines, with pens as our tools. We go underground not to bury our heads and remain hidden but to traverse and dismantle the borders that confine us. We go underground to emerge stronger, to speak loudly and radically in spaces where our voices are suppressed, and to break through the boundaries that seek to silence us."

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre-Marxist communism refers to the historical, philosophical, religious, and social traditions and movements that articulated ideas akin to communism prior to the formulation of scientific socialism by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the mid-19th century. These pre-Marxist traditions spanned from ancient communal practices to utopian socialist thought in the Enlightenment and early modern period. While lacking the materialist framework and class analysis central to Marxist theory, pre-Marxist communism often advocated for the abolition of private property, communal ownership of goods, economic and social equality, and collective labor, frequently grounded in moral, religious, or idealist justifications.

Long before the emergence of formal political ideologies, human communities engaged in communal practices rooted in survival, social cohesion, and the absence of surplus accumulation. In hunter-gatherer societies and early agrarian communities, collective ownership of land and resources was the norm. Anthropological and archaeological studies of Paleolithic and Neolithic societies reveal that many early human groups operated without permanent social hierarchies or formalized property systems. These egalitarian modes of existence, often termed "primitive communism" by later Marxists, were based on shared labor and mutual aid.

Such societies typically lacked private land ownership and instead organized around kinship and communal decision-making. Surpluses, when available, were distributed according to need, seasonal necessity, or customary norms. The advent of agriculture gradually led to stratification and private accumulation, but many early agrarian societies retained significant communal elements, such as collective irrigation systems and village-based landholding.

Various ancient religious and philosophical systems developed visions of social organization that reflected or idealized communal principles.

Early Christian communities, particularly as described in the Acts of the Apostles, practiced a form of communal living in which property was held in common and distributed according to need (Acts 2:44–45, 4:32–35). Inspired by the teachings of Jesus Christ, these communities emphasized moral equality, humility, and shared wealth. Church Fathers like Basil the Great and John Chrysostom criticized wealth accumulation and promoted almsgiving and community welfare, seeing poverty not as natural but as the result of social injustice. While not advocating systematic revolution, these teachings laid a moral groundwork for later critiques of private property.

In South Asia, both Buddhism and Jainism promoted monastic traditions based on communal living and renunciation of possessions. Monks and nuns lived in collectives where personal property was minimal or forbidden, and work was shared. While these traditions emphasized spiritual liberation rather than social reform, they proposed an alternative mode of life that rejected the accumulation of wealth and stressed ethical conduct and compassion for all beings.

Plato, particularly in his work The Republic, imagined an ideal society in which the guardian class shared property, spouses, and children to prevent corruption by private interest and promote unity. Though hierarchical and not democratic, Plato’s vision rejected private property among the elite as inherently divisive. Later philosophers like the Cynics and Stoics also expressed disdain for material wealth and advocated simpler, communal lifestyles.

During the feudal period, numerous peasant uprisings were driven by grievances against landowners, taxes, and inequality, often expressing proto-communistic ideals. The 1381 English Peasants’ Revolt and the 1525 German Peasants' War, although diverse in motivation, included demands for the abolition of serfdom, communal use of land, and egalitarian social structures. In many cases, these uprisings were infused with millenarian religious zeal, imagining a future egalitarian order as the fulfillment of divine justice.

Groups such as the Waldensians, Lollards, and Taborites challenged both Church and secular authority, denouncing wealth and advocating for a return to apostolic poverty. Among the most radical were the Anabaptists of the 16th century, especially in the Münster Rebellion (1534–1535), where leaders like Jan van Leiden briefly established a theocratic communal society. The community abolished private property and implemented common ownership, although it was also marked by authoritarian rule and violent suppression. Despite their failure, these movements represented early attempts to realize communal principles through collective action.

During the mid-17th century English Civil War, groups like the Levellers and Diggers emerged advocating political and economic egalitarianism. The Diggers, led by Gerrard Winstanley, established communal farms on common land, proclaiming that "the Earth was made a common treasury for all." While the Levellers focused more on democratic reforms, the Diggers explicitly opposed private property and the existing class structure. Their philosophical justification was both religious and rationalist, anticipating later socialist thought.

The 18th and early 19th centuries saw the emergence of utopian socialism, which, while not termed "communism" in every instance, laid the intellectual foundation for modern socialist and communist theory. These thinkers criticized capitalist inequality and private property, advocating various forms of cooperative or communal living.

A relatively obscure Enlightenment thinker, Morelly authored Code de la Nature (1755), which proposed the elimination of private property, inheritance, and money. In his ideal society, goods would be stored in public repositories and distributed according to need, with citizens working cooperatively in occupations suited to their abilities. Morelly’s work prefigured many elements of Marxist communism but lacked a theory of class struggle or historical development.

Although not a communist, Rousseau's critique of private property in Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1755) deeply influenced later communists. Rousseau argued that the institution of private property led to the rise of inequality, domination, and moral corruption, and he idealized a more egalitarian, communal past.

Often regarded as the first revolutionary communist, Babeuf led the Conspiracy of Equals during the French Revolution, aiming to overthrow the Directory and establish a classless, egalitarian republic based on common ownership. Influenced by Rousseau, he advocated the abolition of private property and the organization of labor for the collective good. Although the conspiracy was suppressed in 1797, Babeuf's vision deeply influenced later communist movements and thinkers, including Marx.

Fourier imagined a society organized into small, self-sufficient communities called phalansteries, where work would be organized cooperatively and passions harmonized. He envisioned the abolition of wage labor and believed that human fulfillment required collective living and shared resources. Fourier’s ideas were often eccentric, but his critique of capitalism and advocacy for communal living were influential in 19th-century socialist circles.

A Welsh industrialist-turned-reformer, Owen implemented proto-communist practices in his factories and attempted to establish utopian communities such as New Harmony in Indiana (1825). He believed that character was shaped by social conditions and that cooperative living could create rational, moral individuals. While his communities failed, Owen became a leading figure in cooperative and early socialist movements in Britain.

Blanqui was a revolutionary who, while not a theorist of communism in the Marxist sense, advocated for a revolutionary vanguard to seize power and implement economic equality. His emphasis on insurrection and a temporary dictatorship of revolutionaries as a means to egalitarian ends had lasting influence on revolutionary strategy in later communist thought.

Although many of the aforementioned figures and movements held ideas akin to communism, the term "communism" itself began to gain more formal ideological identity in the early 19th century, prior to Marx and Engels.

The term communisme emerged in French political discourse during the 1830s and 1840s. Figures such as Étienne Cabet, Théodore Dézamy, and Wilhelm Weitling began using it to denote visions of a society organized around collective ownership and equality. Cabet’s Icarians founded communal settlements in the United States, pursuing a practical application of his Christian-communist ideas as described in Voyage en Icarie (1840).

A secret revolutionary society founded by German émigrés in Paris, the League of the Just espoused radical egalitarian principles and called for the abolition of private property. It later evolved into the Communist League, under the influence of Marx and Engels, but its roots were firmly in the moral and religious radicalism of earlier pre-Marxist communism.

A German tailor and radical, Weitling combined millenarian Christianity with early proletarian consciousness. In works like Guarantees of Harmony and Freedom, he called for the establishment of a classless, communal society by means of revolutionary action. Marx later criticized Weitling’s moralistic and non-materialist approach, but he acknowledged his importance as a pioneer in worker-oriented communism.

Pre-Marxist communism encompasses a diverse array of traditions, movements, and ideas united by their opposition to private property, social hierarchy, and economic inequality. Whether rooted in religious doctrine, philosophical idealism, or utopian imagination, these early forms of communism laid the ethical and conceptual groundwork for the later development of scientific socialism. While lacking the historical materialist framework and systemic critique of capitalism that would define Marxist communism, these early expressions were nonetheless foundational in articulating humanity’s recurring aspiration for a more just and egalitarian society.

#communism#socialism#utopianism#pre marxist communism#utopian socialism#radical history#historical materialism#commune#early communism#egalitarianism#anarchism#political philosophy#political history#leftist theory#history nerd#revolutionary thought#marxist theory#class struggle#anti feudal#philosophy blog#social history#critical theory#anti oppression#intellectual history#diggers#levellers#early christianity#history community#post long read#tumblr think piece

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post #7

What role does community play in Spier’s transformation?

Community plays a crucial role in Zeke Spier’s transformation by providing both support and a framework for action. As he becomes more involved in activism, the people around him reinforce his beliefs and help him channel his frustrations into organized resistance. The author notes that "Spier found solidarity among activists who shared his convictions, offering him both emotional reassurance and tactical knowledge" (Elin). This suggests that radicalization is not an isolated journey but one deeply embedded in collective struggle, where individuals draw strength from their peers to challenge existing power structures.

For the software mavis beacon, do you think it was ethical for the software developers to take pictures of the woman and put them later for much time

I believe it was unethical for the developers of Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing to use the woman’s image for so long without ensuring her continued consent. While she may have initially agreed to the photoshoot, she likely didn’t anticipate her likeness being used for decades. If she wasn’t fairly compensated or given the option to revoke permission, that raises serious ethical concerns about exploitation and informed consent.

From my perspective, people should have control over how their image is used, especially in commercial products. If the software developers had been more transparent and allowed her to renegotiate her involvement, it would have been a much fairer situation. This case makes me think about how digital rights and image usage should be handled more ethically in today’s world.

How does the internet contribute to the globalization of white supremacist movements

The internet plays a crucial role in the globalization of white supremacist movements by allowing individuals across different countries to connect, share ideologies, and organize. Unlike previous eras, where white supremacist movements were often confined to specific regions, the digital age has facilitated a transnational network of extremists. The text highlights this by noting that "Stormfront’s tagline from the beginning has been ‘white pride worldwide,’ a motto that speaks to the global vision of the site’s creators as well as to the current reach of the site" (Daniels, p. 41). This demonstrates how online platforms serve as hubs for uniting white supremacists beyond national borders, strengthening their collective identity and influence. As a result, these digital spaces not only spread racist ideologies but also provide tools for recruitment, organization, and mobilization, making white supremacy an increasingly globalized phenomenon.

In what ways does the framing of white supremacy as a response to globalization limit our understanding of its impact on society?

Framing white supremacy primarily as a response to globalization rather than as a racial ideology limits our understanding of its deeper societal impact. By emphasizing economic anxieties and cultural displacement, such interpretations risk downplaying the role of systemic racism and historical white privilege. The reading critiques Castells’s analysis, stating that he "mistakenly takes the patriot movement as the ideal type for all other white supremacist organizations" and in doing so, "misses the extent to which the Internet figures in the formation of a global white identity that transcends local and regional ties" (Daniels, p. 45). This suggests that reducing white supremacy to a reaction against globalization ignores its roots in deeply ingrained racial hierarchies. Understanding white supremacy as a structured and historically persistent racial ideology allows for a more comprehensive analysis of its continued presence in society and the ways it adapts in the digital age.

Elin, L. (n.d.-b). The Radicalization of Zeke Spier. Cyberactivism: Online Activism in Theory and Practice.

Seeking Mavis Beacon Documentary

White Supremacist Social Movement Online And In A Global Context by J. Daniels

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The grotesque isn’t the opposite of beauty, it’s often its mirror. Pain and elegance aren’t mutually exclusive. Trauma doesn’t invalidate artistry; it can birth it. But this isn’t a truth people like to sit with. In a cultural climate obsessed with healing and safe expression, we’ve created a hierarchy of acceptable pain, what kind can be shared, how it should be framed and most importantly, how it should make the audience feel.

This essay is not about making anyone feel better. Quite frankly I’m not here to do that. It’s about defending the artist’s right to create without moral constraint. I want to argue for the legitimacy of work that unsettles, that confronts, that even disturbs. Because there are some experiences that shouldn't be made soft. And there are artists, myself included, who don’t want to soften them. Those stories still deserve to be told. Viewer discretion advised.

I believe it’s valid to turn the most traumatic, violent or grotesque elements of life into art. Not as therapy. Not as spectacle. But because they exist. And because ignoring them doesn’t make them go away. It doesn’t change reality. The world can be filthy.

The Moral Expectations Placed on Art Today

In contemporary culture, art is often expected to perform a function: to heal, to empower, to uplift or at the very least, to teach a lesson. This is especially true in digital spaces, where context collapses and everything becomes public-facing. The artist is not just asked what they created, but why and whether that “why” fits within an acceptable moral framework. Intention is scrutinized. Impact is judged. Nuance is flattened.

Discomfort, unless framed within a narrative of overcoming, is seen as a threat. Work that lacks resolution is considered dangerous. Art that centers pain, especially if it's raw, unresolved, or confrontational, is often met with suspicion, as if the artist is exploiting the suffering rather than expressing it. Somewhere along the line, we began to treat difficult work as irresponsible and problematic.

But art was never supposed to be safe. Some of the most culturally significant works throughout history, Guernica, Galliano at Dior, Highland Rape, dare I even say The Weeknd and Sam Levinson’s The Idol, were met with outrage in their time. Not because they were morally wrong, but because they revealed something society wasn’t ready to look at. This is what powerful art often does: it forces confrontation.

When we expect art to soothe or educate, we reduce it to a tool. But art isn’t always a message. Sometimes it’s a mirror. And sometimes, the reflection is violent.

Highland Rape as Case Study: On McQueen and the Right to Disturb

In 1995, Alexander McQueen sent models down the runway in torn dresses, smeared makeup and exposed breasts. Some of them looked like they'd been assaulted. Others looked like they’d survived it. The collection was titled Highland Rape and the backlash was immediate.

Critics accused him of glamorizing violence against women. Feminists called it offensive. Headlines labeled him misogynistic, exploitative, dangerous. But McQueen wasn’t glorifying harm: he was documenting it. The collection wasn’t about the violation of women. It was about the violation of Scotland, its historical domination, its identity stripped by colonial force. “It was about England’s rape of Scotland,” he said. The women on that runway weren’t victims. They were territory. And they were fighting back.

The nuance didn’t matter. It never does when something makes people uncomfortable. No one wanted to engage with the metaphor. They wanted to be outraged. And McQueen was left to defend his work, again and again, against people who had already decided what they thought it meant.

But McQueen didn’t stop. He never tried to become more palatable. He didn’t apologize for making people uncomfortable he pushed further. He created shows that mirrored psychosis (VOSS), questioned bodily autonomy (Deliverance) and deliberately disrupted conventional notions of taste and femininity. He once said, “I want to empower women. I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.” That was the point. To force confrontation. To make people feel something that couldn’t be ignored.

He was misunderstood but not by accident. When you refuse to offer comfort, people will always try to reduce you to the thing they fear most. And that’s exactly what happened to him. It’s what happens to anyone who tells the truth too brutally, too early, too beautifully.

I don’t romanticize McQueen. He was chaotic, inconsistent and sometimes didn’t know how to explain himself. But he knew exactly what he was doing. He used fashion as a scalpel. And the world hated him for it until it decided he was a genius. But that’s how it always goes. They attack you first. Then they frame you.

The Problem with Cancelation as Reflex Response

We’ve created a culture where discomfort is treated like danger and outrage is treated like justice. The moment an artwork crosses a line, we don’t ask why it exists. We ask who to blame. We cancel first and interpret later, if at all.

It’s not that there aren’t things worth calling out. There are. But what we’re doing isn’t always accountability it’s moral policing. We are scrubbing the timeline clean of anything that forces us to sit with what we don’t like. We pretend that removing the artist will remove the discomfort. That silencing the voice will erase the truth it tried to speak.

But what happens when the work is meant to disturb? What happens when provocation is the point? When the artist isn’t careless or cruel, but just unwilling to conform to a narrative of healing, hope or clarity?

People like McQueen were nearly destroyed for refusing to soften the truth. If he were emerging today, he would be canceled before his third show. Not because he was harmful but because he was loud. Because he didn’t ask for permission. Because his work made people feel something they couldn’t control and that’s the one thing our moral economy seems unable to tolerate.

Cancel culture doesn’t just punish the offensive. It punishes the unpredictable. The complicated. The ambiguous. The artists who don't offer easy answers. And when you punish people for making others uncomfortable, you don’t eliminate harm you eliminate honesty.

I’ll be honest: some of the things that inspire me most would disturb other people. Blood. Death. Decay. Psychosis. Existential dread. The world as it looks through the eyes of mental illness. I don’t just tolerate those things, I’m drawn to them. Not because they’re shocking, but because they’re honest. Because they expose something raw and unfiltered about being alive. I find beauty in nightmares, in horror and the uncanny.

I Don’t Want to Be Palatable

This is where the essay takes a more personal turn but bare with me, it might be worth your time.

I see myself in artists like McQueen not because I want to imitate their chaos, I’m already a walking contradiction, but because I understand what it means to be misread. To be told that what you’re expressing is too much, too dark, too uncomfortable. That you should tone it down, make it prettier, more digestible. I’ve heard the same suggestions, spoken or implied: add resolution, offer hope, give people something they can walk away from feeling better.

But I don’t want to make people feel better. I want to make them feel something real.

When I say I find beauty in the grotesque, I don’t mean I want to romanticize suffering. I mean that I reject the idea that beauty must be soft, symmetrical or safe. I believe that what is difficult to look at can still be meaningful. That what is horrifying can still have value. And that pain, when turned into art, does not always need to be justified or explained.

Sometimes, I make work out of the things that have broken me. Not to process them. Not to heal. But because they happened. Because they shaped me. Because I refuse to pretend they weren’t there. And maybe, even after creating it, I still feel like shit. That’s okay. If the result disturbs you, that’s fine. You are free to look away. But I am also free to keep creating.

Being misunderstood is not a tragedy to me. Not everyone is going to understand me. Being silenced is.

You Don’t Have to Look

This isn’t an invitation. It’s an appeal.

I will continue to make what I need to make. It might disturb you. It might not follow the rules. It might not leave you with anything useful. That’s not my problem. That’s not my job.

You don’t have to look. But I won’t stop showing you. And if the only thing you take away from my work is your own discomfort then maybe that’s the most honest reaction you’ll have all day.

We do not owe the world prettiness. We do not owe our pain a soft translation. And we do not owe art a purpose beyond itself.

Some of us create to survive. Some of us create to expose. Some of us create to remind you that not everything wants to be fixed.

Let it bleed.

#think piece#philosophy#fashion#berlin#art#alexander mcqueen#archive fashion#fashion theory#fashion essay#fashion philosophy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

List Interface in Java With Program Example

List interface inherits Collection interface that provides behaviour to store a group of individual objects. It represents group of individual objects as single entity where duplicates are permitted and elements are ordered in the same manner in which they are inserted. It resides within java.util packages. It defines listIterator() method which returns ListIterator object which empowers the…

View On WordPress

#collection#collection framework#Hierarchy in Collection Framework#java#java program#List#List interface

0 notes

Text

Between Credit and Consequence: Observations on the Audience, Quiet Hierarchies, and the Subtle Pitfalls of Monopolising Collective Memory

Something curious is happening. On the surface, a dispute of names, exhibitions, images and intent. A tangle of creativity, memory, and misrecognition. Beneath that, however, it begins to resemble something else. A mirror reflecting an older, deeper conversation.

I’ve been closely observing the public responses to a recent moment in the creative world involving the Woza Sisi Collective and Trevor Stuurman. The perspectives shared by artists, audiences, and institutions alike have highlighted an overdue conversation. One that extends beyond the specifics of this case, while still being shaped by it. What the collective has surfaced bravely and with clarity, gestures toward something far older, far more embedded: the quiet mechanics of power in creative spaces, the subtle influence of language and the uneasy question of how easily harm can be reframed or dismissed, especially when it leaves no visible trace depending, of course, on who is doing the looking.

Public sympathy often follows charm, profile, or reputation. This is why it is worth asking who is believed, and why? Who is protected, even when no one explicitly defends them? Who is allowed to speak candidly, without fear that the act of voicing discomfort will cost them more than it reveals?

As our nation becomes increasingly litigious, many significant and legitimate cases are overshadowed by sensationalism, gossip, or the phenomenon of 'trial by social media'. In this case, we desperately need to remain focused and remember that to name influence is not to accuse. Seeking context is not a threat. Nonetheless, the arts are rarely neutral territory. Even within liberatory language, there are unspoken rules. Who may critique whom, who can express harm and still be invited back in? This moment, then, isn’t solely about one artist. It speaks to broader conditions. To how unease is so easily repositioned as aggression and how precarious it is to hold both admiration and disappointment in the same hand.

The archive is often treated as sacred, a home for memory. Yet archives are also constructed through power. Some people are remembered, cited and entered. Others are left out. Across time, Black women and queer bodies have curated, documented, imagined, and preserved. Often, their work enters the world unaccompanied by their names. Their titles, frameworks, and aesthetics become detached, reused not as homage, but as raw material. This may not always be ill-intentioned. Still, it leaves the work unanchored.

Creative labour (especially when it comes from Black women, collectives and queer bodies) is often seen as ambient. It is not always recognised as authored or proprietary. When a boundary is drawn, the response is rarely equal. Others can be questioned and still emerge intact. Their reputations survive. Their careers continue. In a field where harm is only recognised when named by the powerful, staying silent can become a form of protection. The term ‘Collaboration’, can so often be used but by the time we realise it was instead exploitation, too much has been lost in translation. You risk falling into a sort of “career limbo” if you choose to raise your concerns.

This moment does not ask for cancellation. Instead for a different kind of presence. One that is slower, more deliberate and grounded in care rather than performance. True accountability means remaining in the room when discomfort arises. It means saying, “I see you. I hear you. Let’s talk.”.

We are often drawn towards binaries: inspiration or theft, intention or impact, love or harm. The truth often resides in quieter places. It lives in the dissonance of recognising harm without villainy. Good intentions do not always soften difficult outcomes.

When something deeply personal is echoed elsewhere without your name- It is the ache of erasure dressed as coincidence, the slow burn of navigating spaces where credit is optional and silence is expected. What lingers is not just exclusion, but what happens when Black women voice unease and are met with dismissal rather than curiosity. As if naming harm is more disruptive than causing it.

Still, we speak.

Some of us remain one sentence away from being forgotten. Others are never asked to explain. Somewhere in between, the art keeps moving. Sometimes with us. Sometimes without us.

#photography#art#writer#artist#black#african#IP#artwork#art study#my art#2025#Fyp#explore#explore page#life#woza sisi#trevor stuurman#think piece#discourse#public opinion#South African arts#Johannesburg#south africa

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Femdom

Came free with my drow posting?

Uhhh. 10/10, but on the aforementioned hierarchy of kinks it's at the base level for me, y'know. It can be the framework for a scene, but it can't be the only thing going on in a scene or I'll get bored. The best way I can phrase this is that like. There are some femdom pieces that are just missionary with the lights off but the woman on top and it's like no. I need these woman to be MEAN. I need them to HIT PEOPLE.

Fortunately we as a community seem to understand the collective appeal of a woman with a riding crop and a nasty little expression, sooo. 10/10

Anyway, this is another one where if I have a female character there's a 9/10 chance she's femdom'ed at least once just because the character type I enjoy writing is the way it is. I generally write all of my characters as switches (sometimes with preferences, but I think leaving them able to play in different roles makes it easier to explore more about them through sex.)

That in mind. I have a sketch somewhere that's younger ilphaer going "Wouldn't it be awful if woman were mean to us?" and blushing bashfully so take of that what you will.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Museums

Image: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, Picture Gallery with Views of Modern Rome (detail), 1757. Oil on canvas. Charles Potter Kling Fund.

Museums and their practices of collection, curation, and exhibition raise a host of philosophical questions. The philosophy of museums is a relatively new and growing subdiscipline within the academic field of philosophy.

While only recently taking shape as a distinct area, this subdiscipline builds upon a tradition of interest in museums that has been taken up by prominent philosophers, such as Theodor Adorno (Prisms 1967) and Michel Foucault (Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology 1998).

Philosophers active in the philosophy of museums are less concerned with intra-disciplinary differences (between, e.g., “continental philosophy” and “analytic philosophy” and their recent permutations) than they are with thinking about the museum on its own terms as a phenomenon calling for philosophical engagement. - Oxford

As their name suggests, cabinets of curiosities aimed to capture and define new knowledge of the world, prizing anything rare, unusual or unique. In 1565, Belgian physician Samuel Quiccheberg’s treatise on collecting expressed the cabinet’s ambitious aims, describing it as “a theater of the broadest scope, containing authentic materials and precise reproductions of the whole of the universe.”

The treatise also emphasized the importance of display and order. Collectors imposed their own systems and hierarchies on the art, antiques, plants and animals within their cabinets in an attempt to create an encyclopedic framework of the world’s knowledge. - Smithsonian

...from a psychoanalytic perspective, it can be argued that "art, but also other objects, exhibitions, and performances as well, elicit emotional, wishful, as well as cognitive responses best characterized as nostalgic" (87). Lord analyses the connection between museums and wonder, based on Descartes' and Spinoza's views of wonder.

According to Descartes, wondering at unknown objects is good only if it leads to attempts to understand them intellectually. According to Spinoza, wonder is a threat to imagination: imagining an object is naturally linked with imagining other objects that we have experienced it with or that share features with it -- activities which, he claims, are at the basis of reasoning.

...from a psychoanalytic perspective, it can be argued that "art, but also other objects, exhibitions, and performances as well, elicit emotional, wishful, as well as cognitive responses best characterized as nostalgic" (87). Lord analyses the connection between museums and wonder, based on Descartes' and Spinoza's views of wonder.

In conclusion, I would like to return one last time to this central point, the philosophy of the institution. I have named some of the possibilities in this regard. There is one, however, I have not yet mentioned: the art museum that is not a memorial and not political, not an urban monument and not an architect’s museum, not a place of education and not someone’s personal statement, but which is humbly and quietly a museum for art. Now and again you find one of these, too, and it thereby sometimes results in a happy outcome – because at last art, too, is in a place where it can unfold properly as art. - Raussmüller

#museum#philosophy#art history#art criticism#art#history#public art#european art#renaissance art#cabinet of curiosities#education#vintage aesthetic#vintage#humanities

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

3. The Dhamma and Nondogmatism

The term dogma has a few definitions. Its origin in English derives from Catholic Christianity, and is etymologically linked to the Greek word, δόγμα (dogma) which literally means “that which one thinks is true”. The Roman Catholics repurposed the word into Latin to mean, “an inconvertible truth made known through divine revelation”. And since roughly the second century CE, dogma was used as a means to control discourse and enforce a clerical and feudal hierarchy among residents of Christendom. Dogma has come to mean a set of beliefs that are not only “incontrovertible truth”, but enforceable under arbitrary rule. Any challenge against such dogmas in Christendom, and the other Abrahamic religions (Islam and Judaism) has been at one time or another suppressed and condemned. This notion was exacerbated by the concept of divine right that meant the kings or other feudal regents would have unquestioned authority over their people. At certain periods and in some societies, denial of dogma was punishable by death. As a contrast, Buddhism does not have any such requirements. Of course there are social pressures is many communities for people to be Buddhist, but there has been no literature or governing body that mandated subscription to a specific set of beliefs. Of course we can assert instances of violence or suppression in Myanmar, China, Southeast Asia, and Japan. But these instances are not caused by disbelief in specific doctrine.

If you search for “Buddhist dogma” on Wikipedia you will come across diṭṭhi (right view). The tenet of diṭṭhi has been offered as an example of Buddhist dogma. But this is a flimsy analogous term, because right view is just one tenet of eight within the Noble Eightfold path. Diṭṭhi cannot be equated with Christian dogma because it is not broad enough to be the framework for most of the Buddhist doctrine in the same way dogma does for Christians. If I were to put on my Christian hat for a moment and try to make an analogy here: it would be like trying to say the keystone tenet of Christianity is the first Beatitude from the Sermon on the Mount, “blessed are the poor [in spirit if Matthew]”. As you may know, there are a few more Beatitudes in that sermon (ten in Matthew and four in Luke). So too is the same for the Noble Eightfold Path, there are eight tenets, and they all comprise just one component of the Buddha’s dhamma (teaching). So I hope that illustrates the incompatibility of diṭṭhi serving as a substitute to dogma.

Then there is the collective dhamma being presented as another stand-in for dogma in Buddhist thought. But this cannot be the case either, because the dhamma is the summation of all of Shakyamuni Buddha’s teachings. And if this is the case, then the dhamma would be self-contradictory as a dogma due to various suttas that speak against compulsory belief. The most prevalent sutta is the Kesamutti Sutta, as it specifically addresses the problem with unquestioned beliefs in this excerpt [numbers are my own]:

Do not go upon what has been acquired by repeated hearing (anussava),

nor upon tradition (paramparā),

nor upon rumor (itikirā),

nor upon what is in a scripture (piṭaka-sampadāna)

nor upon conjecture (takka-hetu),

nor upon an axiom (naya-hetu),

nor upon fallacious reasoning (ākāra-parivitakka),

nor upon a bias towards a notion that has been pondered over (diṭṭhi-nijjhān-akkh-antiyā),

nor upon another’s seeming ability (bhabba-rūpatāya),

nor upon the consideration, The monk is our teacher (samaṇo no garū)

Kalamas, when you yourselves know: “These things are good; these things are not blamable; these things are praised by the wise; undertaken and observed, these things lead to benefit and happiness”, enter on and abide in them.

It just so happens that the above passages hit on every aspect of political indoctrination. This is quite astounding for how advanced they are in terms of discussions regarding belief. The first instruction, anussava, relates to belief by rote memorization. This is often forced upon pupils or citizens through educational institutions and quite often the news media today. Less resolute or acquiescent people will exhibit strong beliefs in things simply because they hear about them so often. The second instruction, paramparā, is just as astounding as the first because it warns against the appeal to tradition. This is often known as the informal fallacy, argumentum ad antiquitatem (appeal to tradition), that states that a claim is not true simply because people hold it as a tradition or have believed it was true for some amount of time. Similarly, rumors or hearsay, the third instruction, itikirā, are not reliable sources of truth because, even if a person is convinced of the truth of something, it does not mean they remember it completely and clearly. This is why hearsay is not admissible as evidence in any scientific setting. Yet, corrupt governing officials and business owners appeal to hearsay as a source for decision-making processes all the time.

It is interesting the fourth instruction, piṭaka-sampadāna, uses the term piṭaka which is self-referential to the Buddhist doctrine, the Pali Canon. So, in English it is translated as scripture, but the scripture in question is the sutta itself as it exists within the Sutta Piṭaka which is a pivotal source of the Pali Canon as a whole. The fifth teaching, takka-hetu, warns against conjecture, or assumptions based on preconceived notions. The sixth, naya-hetu, warns against axioms and again I think this is self-referential, because the axioms in question here would be popular phrases the Buddha or similar instructors would be preaching at the time. Axioms, maxims, truisms, or aphorisms, have strength in being memorable and seem true enough that many people simply repeat them and use them heuristically in society- which is often fast-paced and unaccommodating to lengthy discussion. But when we go through our whole lives assuming the truth of an axiom without investigation, it could lead to the acceptance of a fallacious rationale or bald assertions. The other weakness of axioms is that people can remember their content, but not the context nor the deeper meaning to them.

By extension of the sixth instruction, the seventh, ākāra-parivitakka, warns against fallacious reasoning at all. The term ākāra is literally defined as shape or form, but it has another definition meaning appearance, aspect, or image. And parivitakka means a reflection or consideration. And I think this is founded in the Buddha’s description of reality— the Three Marks of Existnece: anicca (impermanence), dukkha (dissatisfaction), and anattā (non-self) — and our delusions about reality, known as the Five Aggregates or Khandha. These are delusions we have that prevent us from seeing reality for what it is. The Five Aggregates are: rūpa (form), vedanā (sensation), saññā (perception), saṅkhāra (mental formations), and viññāṇa (consciousness). In summary, these five concepts we have about the world are fallacious because they fail to recognize anicca (impermanence), our inability to sense certain aspects of reality, our biases, our unskillful thoughts, and they delude us into clinging to the delusions of the self that have no basis in the aforementioned aspects.

The eighth instruction, diṭṭhi-nijjhān-akkh-antiyā, is also self-referential and is really about not misinterpreting the origins of one’s insight as it could be skewed by bias. As stated above, the term diṭṭhi means right view. Nijjhān means insight, akkh refers to what the eye sees, and antiyā are the ideas we have pondered before. The ninth instruction, bhabba-rūpatāya, should be of interest to anarchists in that it speaks against following charismatic leaders or those we think are particularly skillful on those qualities alone. That disposition only leads to unquestioned servitude via admiration. The tenth instruction, samaṇo no garū, also leans towards anarchism because it is the antithesis to the appeal to authority fallacy. A proposition is not true merely based on the assertion that a person in authority said it was true. And a person’s perceived rank is not sufficient to substantiate their claims just as it is not enough for any other person. Every person needs to demonstrate and justify why their viewpoint merits consideration, and they come under greater scrutiny if they are claiming to state the truth about a subject.

If Buddhists really apply the Kesamutti Sutta as a logical device, then they absolutely cannot be dogmatic in any sense. And if this is the case, the nondogmatic disposition of Buddhism allows adherents to question and analyze any propositions that come their way, including the basis of authority of others. The Kesamutti Sutta is a powerful instrument that warns against indoctrination and unquestioned loyalty to so-called leaders, secular or religious. And in a time when Brahmins were believed to have privileged authority over other castes, the Buddha’s Sangha (community of bikkhu monks and bikkhuni nuns) functioned as a rapidly spreading commune that would provide an alternative to established society.

#desi#desiblr#Buddhism#Caste#India#nonviolence#pacifism#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#mutual aid#grassroots#organization#anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Institutionalism

Institutionalism is a philosophical framework that explores the nature, origins, functions, and impacts of institutions on human life and society. Institutions, in this context, refer to structured systems or norms governing behavior, such as governments, legal systems, religions, markets, schools, and other social organizations. Institutionalism examines how institutions shape human behavior, reflect collective values, and influence cultural, economic, and ethical frameworks.

Key Aspects of the Philosophy of Institutionalism

Definition and Ontology of Institutions

Institutions are seen as enduring systems of rules, norms, and practices that structure social interaction.

Ontologically, they can be viewed as either constructivist (human-made constructs) or realist (having a degree of independent existence).

Institutional Functions

Social Order: Institutions provide stability and predictability in society.

Collective Action: They enable cooperation by coordinating group efforts and reducing uncertainty.

Value Transmission: Institutions preserve and transmit cultural, ethical, and historical values.

Institutional Evolution

Institutions are not static; they evolve over time due to changes in societal values, technology, or external pressures.

Institutionalism studies how traditions and innovations coexist and how outdated systems may persist despite inefficiencies.

Critiques and Challenges

Power Dynamics: Institutions can reinforce hierarchies, perpetuate inequality, and privilege certain groups over others.

Bureaucratic Alienation: Institutions can become rigid, focusing more on self-preservation than on serving their intended purposes.

Moral Questions: Are institutions inherently moral, or do they require continuous ethical scrutiny?

Institutions and Agency

Institutionalism explores the tension between individual agency and structural constraints.

It questions whether individuals shape institutions more, or vice versa, and how much freedom exists within institutional frameworks.

Economic and Political Institutionalism

Examines the role of institutions in shaping economic and political systems.

Includes theories like New Institutional Economics (which studies transaction costs and property rights) and Political Institutionalism (which analyzes governance structures).

Cultural and Religious Institutionalism

Investigates how religious and cultural institutions influence personal identity, ethics, and social norms.

Institutional Decay and Renewal

Institutions can become corrupt, inefficient, or irrelevant, leading to calls for reform, replacement, or dissolution.

Philosophical Questions in Institutionalism

What is the moral responsibility of institutions?

How do institutions mediate between the individual and society?

What is the role of tradition versus innovation in institutional development?

Can institutions transcend cultural or temporal contexts to become universal?

Relevance of Institutionalism Today

The philosophy of institutionalism is particularly relevant in modern debates on:

Reforming global governance and economic systems.

Addressing systemic inequalities in social and political institutions.

Balancing innovation and tradition in institutional frameworks.

Understanding the interplay between technology and institutional change.

Institutionalism ultimately seeks to understand and evaluate the mechanisms by which institutions shape, and are shaped by, the human condition.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#Philosophy of Institutionalism#Social Structures#Institutions and Society#Ontology of Institutions#Institutional Ethics#Power Dynamics#Cultural Institutions#Political Institutionalism#Economic Institutionalism#Social Order and Stability#Institutional Change#Individual Agency vs. Structure#Institutional Critique#Tradition and Innovation#Governance Systems

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

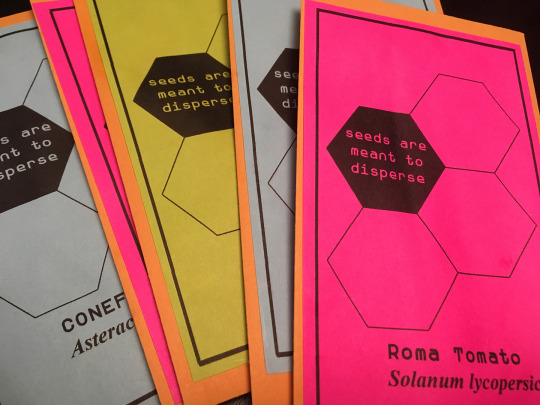

Christina Battle, PhD - Media Artist

Christina Battle (she/her) is a film and video media artist based in Edmonton and Treaty 6.

What does your work entail?

My work initially centered on film and video, focusing on how media takes time—not only to create but also to communicate stories and ideas. Over time, I began applying that same sensibility to other artistic disciplines, particularly participatory practices. These practices often involve performance artists whose work consists in working with communities, creating projects, and developing frameworks that encourage participation. By engaging public groups and fostering interaction, my work aims to explore and expand the boundaries of art as a shared experience.

How does your work overlap with Community Service Learning (CSL)?

There’s a significant overlap between my artistic practice and CSL, particularly in the shared focus on community building and the complexities of what it means to “be in community.” The term “community” is used so broadly in both art and society that it often requires unpacking.

CSL offers an incredible opportunity to slow down and ask foundational questions: What does it mean to engage in community? How can we imagine new ways of connecting? My work also asks similar questions—how do we build relationships, understand one another, and decide who we want to engage with? Both approaches involve exploring how we create spaces for connection and collaboration.

How do you incorporate CSL students into your work?

In Spring 2023, I was invited by Lisa Prins and Allison Sivak (CSL course instructors), to share my practice with their CSL 370 class, which focused on plants and gardening—topics that resonate deeply with my work around seeds, plants, and climate change. We met in a park one afternoon, where I brought seeds and shared my projects. The conversations were some of the most engaging I’ve had. While my projects often appeal to artists, this group approached the work from a different perspective, yet shared a genuine interest in the intersections of community, art, and environmental issues.

In Spring 2024, Lisa and Allison invited me to engage more deeply with their course, and I eagerly accepted because of my positive experience the previous year. Collaborating with their students has been incredibly rewarding, creating spaces for shared knowledge and fostering conversations about topics I’m passionate about.

What have you learned by being involved with CSL?

Teaching art and design for 15 years has taught me a lot about pedagogy, but CSL offered a profoundly different approach to learning. Unlike traditional classrooms, which often rely on rigid hierarchies and lecture-based knowledge transmission, CSL fosters experiential, relational, and participatory modes of learning. This aligns perfectly with my practice, where learning alongside and from others is key.

The CSL classroom challenged me to rethink the boundaries of knowledge and how we connect with each other’s histories, cultures, and experiences. It was refreshing to work with students who didn’t identify as artists but were eager to explore art as a tool for justice, politics, and environmental concerns. The openness of the CSL framework allowed us to bypass the conventions of artistic training and dive directly into the complexities of the world we live in.

What do you hope CSL students take away from your presence in the classroom?

I hope students see artistic practice as a powerful strategy for communication. Art isn’t just about self-expression—it’s about relationality and finding ways to connect with others, especially around complex issues like climate change and social justice. Participatory art, in particular, focuses on building relationships and exploring how we can engage with the world in meaningful ways.

Working with the CSL class reminded me of the collective desire to address these challenges. While individual action can feel isolating, coming together in shared spaces—whether through art, conversation, or collaboration—can inspire new strategies for expression and problem-solving. I hope the students left with a sense of empowerment to use creative tools to communicate and enact change.

How has your involvement with CSL impacted you?

One lasting memory from my time with the CSL class is tied to the sunflower seeds we worked with. When the class ended, I took home some of the seeds we had discussed and distributed. Over the summer, I harvested seeds from the plants that grew, creating a physical reminder of our shared experience. This ongoing relationship with the seeds feels symbolic of community building—an ongoing, iterative process that takes time and care but can yield incredible results.

Another moment that stood out was during a postcard-making session. One student hesitated, saying, “I’m not an artist,” yet created an absolutely stunning piece. It reminded me that the label of “artist” can be limiting. Many people create beautiful, meaningful work without having been formally trained or identifying with the term. Moments like these reinforce the importance of opening up definitions of art and helping people see its potential as a universal tool for storytelling and connection.

How would you sum up your experience with CSL?

CSL has been an inspiring opportunity for community building, knowledge sharing, and mutual learning. Rather than a traditional artist talk where I simply present my work, the CSL classroom was an activated, relational space where I learned as much as I taught. It was a powerful reminder of the value of slowing down, fostering connections, and embracing art as a tool for collective exploration.

2 notes

·

View notes