#Typical Crustaceans

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Although dam removals have been happening since 1912, the vast majority have occurred since the mid-2010s, and they have picked up steam since the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which provided funding for such projects. To date, 806 Northeastern dams have come down, with hundreds more in the pipeline. Across the country, 2023 was a watershed year, with a total of 80 dam removals. Says Andrew Fisk, Northeast regional director of the nonprofit American Rivers, “The increasing intensity and frequency of storm events, and the dramatically reduced sizes of our migratory fish populations, are accelerating our efforts.”

Dam removals in the Northeast don’t generate the same media attention as massive takedowns on West Coast rivers, like the Klamath or the Elwha. That’s because most of these structures are comparatively miniscule, built in the 19th century to form ponds and to power grist, textile, paper, saw, and other types of mills as the region developed into an industrial powerhouse.

But as mills became defunct, their dams remained. They may be small to humans, but to the fish that can’t get past them “they’re just as big as a Klamath River dam,” says Maddie Feaster, habitat restoration project manager for the environmental organization Riverkeeper, based in Ossining, New York. From Maryland and Pennsylvania up to Maine, there are 31,213 inventoried dams, more than 4,000 of which sit within the 13,400-square-mile Hudson River watershed alone. For generations they’ve degraded habitat and altered downstream hydrology and sediment flows, creating warm, stagnant, low-oxygen pools that trigger algal blooms and favor invasive species. The dams inhibit fish passage, too, which is why the biologists at the mouth of the Saw Kill transported their glass eels past the first of three Saw Kill dams after counting them...

Jeremy Dietrich, an aquatic ecologist at the New York State Water Resources Institute, monitors dam sites both pre- and post-removal. Environments upstream of an intact dam, he explains, “are dominated by midges, aquatic worms, small crustaceans, organisms you typically might find in a pond.” In 2017 and 2018 assessments of recent Hudson River dam removals, some of which also included riverbank restorations to further enhance habitat for native species, he found improved water quality and more populous communities of beetles, mayflies, and caddisflies, which are “more sensitive to environmental perturbation, and thus used as bioindicators,” he says. “You have this big polarity of ecological conditions, because the barrier has severed the natural connectivity of the system. [After removal], we generally see streams recover to a point where we didn’t even know there was a dam there.”

Pictured: Quassaick Creek flows freely after the removal of the Strooks Felt Dam, Newburgh, New York.

American Rivers estimates that 85 percent of U.S. dams are unnecessary at best and pose risks to public safety at worst, should they collapse and flood downstream communities. The nonprofit has been involved with roughly 1,000 removals across the country, 38 of them since 2018. This effort was boosted by $800 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. But states will likely need to contribute more of their own funding should the Trump administration claw back unspent money, and organizations involved in dam removal are now scrambling to assess the potential impact to their work.

Enthusiasm for such projects is on the upswing among some dam owners — whether states, municipalities, or private landholders. Pennsylvania alone has taken out more than 390 dams since 1912 — 107 of them between 2015 and 2023 — none higher than 16 feet high. “Individual property owners [say] I own a dam, and my insurance company is telling me I have a liability,” says Fisk. Dams in disrepair may release toxic sediments that potentially threaten both human health and wildlife, and low-head dams, over which water flows continuously, churn up recirculating currents that trap and drown 50 people a year in the U.S.

Numerous studies show that dam removals improve aquatic fish passage, water quality, watershed resilience, and habitat for organisms up the food chain, from insects to otters and eagles. But removals aren’t straightforward. Federal grants, from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or the Fish and Wildlife Service, favor projects that benefit federally listed species and many river miles. But even the smallest, simplest projects range in cost from $100,000 to $3 million. To qualify for a grant, be it federal or state, an application “has to score well,” says Scott Cuppett, who leads the watershed team at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Hudson River Estuary Program, which collaborates with nonprofits like Riverkeeper to connect dam owners to technical assistance and money...

All this can be overwhelming for dam owners, which is why stakeholders hope additional research will help loosen up some of the requirements. In 2020, Yellen released a study in which he simulated the removal of the 1,702 dams in the lower Hudson watershed, attempting to determine how much sediment might be released if they came down. He found that “the vast majority of dams don’t really trap much sediment,” he says. That’s good news, since it means sediment released into the Hudson will neither permanently worsen water quality nor build up in places that would smother or otherwise harm underwater vegetation. And it shows that “you would not need to invest a huge amount of time or effort into a [costly] sediment management plan,” Yellen says. It’s “a day’s worth of excavator work to remove some concrete and rock, instead of months of trucking away sand and fill.” ...

On a sunny winter afternoon, Feaster, of Riverkeeper, stands in thick mud beside Quassaick Creek in Newburgh, New York. The Strooks Felt Dam, the first of seven municipally owned dams on the lower reaches of this 18-mile tributary, was demolished with state money in 2020. The second dam, called Holden, is slated to come down in late 2025. Feaster is showing a visitor the third, the Walsh Road Dam, whose removal has yet to be funded. “This was built into a floodplain,” she says, “and when it rains the dam overflows to flood a housing complex just around a bend in the creek.” ...

On the Quassaick, improvements are evident since the Strooks dam came out. American eel and juvenile blue crabs have already moved in. In fact, fish returns can sometimes be observed within minutes of opening a passageway. Says Schmidt, “We’ve had dammed rivers where you’ve been removing the project and when the last piece comes out a fish immediately storms past it.”

There is palpable impatience among environmentalists and dam owners to get even more removals going in the Northeast. To that end, collaborators are working to streamline the process. The Fish and Wildlife Service, for example, has formed an interagency fish passage task force with other federal agencies, including NOAA and FEMA, that have their own interests in dam removals. American Rivers is working with regional partners to develop priority lists of dams whose removals would provide the greatest environmental and safety benefits and open up the most river miles to the most important species. “We’re not going to remove all dams,” [Note: mostly for reasons dealing with invasive species management, etc.] says Schmidt. “But we can be really thoughtful and impactful with the ones that we do choose to remove.”

-via Yale Environment 360, February 4, 2025

#rivers#riparian#united states#north america#northeast#pennsylvania#massachusetts#new york#dam#dam removal#good news#hope

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyone else still geeking out on the mystery mollusc? 🤓

Bathydevius caudactylus swims slowly through the midnight zone, an expansive environment of open water 1,000 to 4,000 meters (3,300 to 13,100 feet) below the surface. Most nudibranchs we know of live on the seafloor. They are common in coastal environments, including tide pools, kelp forests, and coral reefs. A small number of species are known to live on the abyssal seafloor. A few are pelagic and live in open waters near the surface.

While most sea slugs use a raspy tongue to feed on prey attached to the seafloor, the mystery mollusc uses a cavernous hood to trap prey like a Venus fly trap plant. Crustaceans are on the menu for Bathydevius caudactylus, though we are still not quite sure how such a slow swimmer catches such speedy prey.

If threatened, Bathydevius caudactylus can light up with bioluminescence. On one occasion, we observed a mystery mollusc illuminate and then detach a glowing finger-like projection from the tail, much like a lizard dropping its tail as a decoy to distract predators.

Bathydevius caudactylus is typically spotted swimming or floating in the water column, but descends to the seafloor to reproduce. We have observed several spawning individuals attached to the muddy seafloor with their muscular foot.

530 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inspired by "Implicit Demand for Proof" by imperialhuxness

-1-

“I need you on the ground,” Ren says instead, measured, but tight-strung as a grappling cable. Apparently sensing the retort on the tip of Hux’s tongue, he continues, “But I’m not taking you into the thick of combat.”

Hux thins his lips, keeps up the patient tone. “That’s where this team and I will be most effective.”

“At too high a risk.”

Since when do you care about risks? Hux barely bites back, instead manages, level, “Nothing we do is without risk.”

Ren’s gaze flashes with an insistence that isn’t anger. His eyes are like coals, waiting for a spark. “I’m not taking you into that firefight.”

Really.

Fucking really.

“So you won’t take me into a firefight,” Hux lowers his voice to a hiss, but it still reverbs under the high ceiling, “yet you dragged me ten klicks below the surface of Coruscant.”

“Well, maybe I--” Ren hesitates, gnawing his lips. His gaze drops to the mosaic tile between their boots, then flickers back to Hux’s face. “I shouldn’t have.”

Hux is too pissed off to bask in the near-admission of wrong. “Well, you can compensate by bringing me this time, when it makes actual, tactical sense.”

“You’re not going into a combat zone.”

“I was born and raised in a--”

Ren’s voice drops to a whisper. “That’s an order,” he says, invoking it almost gently, below earshot of the men.

Hux purses his lips, aware of his surroundings again. Of the absolute indecorum of this argument.

Around himself and Ren, three officers stare at their feet, four tap too aggressively at their datapads. The two trooper commanders confer in whispers about a new blaster model. Mitaka seems interested in the mosaic on the floor.

“Yes, sir,” Hux forces out, Academy pert, and the gathered staff returns more or less to professional attention.

--- -2-

Hux whirls toward the sound as a massive shape bursts through the treeline, scattering leaves. Some sort of megafauna. Some sort of monster.

The creature’s smooth skin glistens livid green, its underbelly sickly pale. Its mouth opens wide, baring short, sharp teeth like a Rodian fly-trap’s. It has six legs, each ending in a crustacean pincer, which stab the ground with each step. It reeks of rot and salt, as if it just crawled out of brackish water.

Hux’s pulse skyrockets, and he jumps back on adrenaline. Why do you ever leave the ship, every time you leave the ship it’s some shit like this, every goddamn time—

He yells to Ren that they should run, even as the creature screeches again, lunges toward them.

But Ren stays put. “You should run.”

And Hux would. He would, but he’s already several meters back, and the soles of his boots weigh a kiloton. He’s rooted to the ground. The blood pounds in his ears, and he can’t move, can’t think.

The thing screeches. It’s high-pitched. It rends the air. Its movements ruffle the foliage around it. Its pincers break the damp earth.

Ren steps in front of Hux. Into its path.

--- -3-

But Yago’s lips still twist into something unbearably self-satisfied. “General Armitage Hux,” he says, “was executed six months ago on a charge of high treason. So even if Hux were alive, it would be my sworn duty to have him shot in the back of the head.”

It hits like a blow. Phantom pain lances through his leg, between his ribs. Yago’s right. There’s no defense when he’s--

Before Hux can formulate one, Ren’s gaze kindles. “I’m Supreme Leader,” he returns, typical thoughtless clapback. “I hereby pardon him.”

(Typical thoughtless clapback.)

Everyone knows traitors receive no mercy.

--- -4-

A humanoid figure emerges from the shadows like he’s been waiting there. In two strides, he closes the distance to Hux and Ren. It’s clear he’s part alien, skin teal-tinged and marked with pale striations. His voice is somewhat rough with drink, but his movements are smooth, purposeful, eyes trained on Hux.

“Thought you could just slip out with your date?” he spits.

There are far bigger concerns than correcting the assumption.

“What?” Hux returns, elegantly.

“The bartender told me you were coming this way,” the man says, ill-concealed rage contorting his mouth. “Got a lot more nerve than I’d give you credit for, showing your face like this.”

Shit. Hux’s pulse picks up, and for a second the alley takes on the sharp edges of panic. You knew this would happen eventually, you knew -- Stop.

“I’m sorry,” he says, tamping down the worst case scenario, “what are you--”

But it’s like he doesn’t even hear it.

“Kind of man that’ll pull a trigger from a thousand lightyears away. Not even the guts to look at what you’d done.” The man’s eyes flash with the sort of hatred Hux actually recognizes. “My wife was on Courtsilius, General Hux .”

The man takes a step closer, and Hux is about to spread his hands and explain with a baffled simper that he’s got the wrong person. That the Hosnian ‘Cataclysm’ was an unspeakable tragedy and a monstrous war crime.

But before he can speak, sulfurous green ignites in his periphery. The air hums, cracks with the sudden whiff of ozone. The blade of the antique saber impales the man’s chest.

--- -5-

Ren shakes his head. “But I still need you,” he says, eyes glittering, desperate, searching. “What about weapons dev? And you can actually conduct diplomacy--”

Hux cracks a smile. “That’s going a bit far.”

Ren huffs a laugh, but doesn’t indulge him. “You balance me,” he continues. “I don’t know what I’ll do. I love you.”

Hux’s pulse drops into his stomach. His spine stiffens, more from surprise than actual discomfort. It isn’t a concept with which he’s familiar. But it’s right, somehow. As Ren’s eyes search his face, curious but unshrinking, he can’t deny it.

527 notes

·

View notes

Text

gynandromorph stag beetle !!

the finished version on procreate and the initial doodle from my sketchbook !!

“a gynandromorph is an organism, typically an insect, crustacean, or bird, that possesses both male and female characteristics.” or, yanno, intersex beetle :)

available on redbubble!

#art#artist#artists on tumblr#original art#digital art#traditional art#queer artist#trans artist#small artist#trans community#traditional drawing#traditional illustration#trans rights#transgender rights#trans#transgender#beetle#bug art#beetle art#gynandromorphism#gynandromorph#procreate art#procreate#intersex

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Novel Norway Lobster

Nephrops norvegicus, better known as the Norway lobster, the Dublin Bay lobster, or in its culinary form as langoustine or scampi, is a small lobster found all along the European coast in the Atlantic ocean, from Norway and Iceland to Portugal, as well as the Adriatic Sea. They reside in muddy seabeds at up to 800 m (0.5 mi) below the surface.

Norway lobsters spend most of their time digging, maintaining, and hiding in their burrows, which are built about 20 to 30 cm (8 to 12 in) deep in the mud. When they do leave their burrows, it is only to forage or mate. Like many lobsters, N. norvegicus is an omnivore; they feed on anything they can find, including carrion, worms, fish, jellyfish, and other crustaceans. Predators include larger crustaceans, such as shore crabs, cod, stingrays, and small spotted catsharks.

The breeding period for Dublin Bay lobsters depends on the population's location and the temperature of the water, but generally takes place in late winter or spring. Females typically mate with 2-3 males, and carries 1000-5000 eggs under her tail for 8 to 9 months. After hatching, the planktonic larvae drift through the ocean for about two months, during which time they rise to the surface at night and descend to the ocean floor during the day. After settling on the bottom, juveniles undergo a molt before becoming fully mature. Afterwards, adults typically undergo 1-2 molts every year, and can live up to 10 years in the wild.

N. norvegicus is typically pink or orange in color, with a white underbelly and a darker stripe along the upper part of the claw. Adults can reach up to 20 cm (8 in) in length including the claws, which can comprise up to half that length. Its large eyes are exceptionally sensitive to light, and Norway lobsters are rarely seen during the daytime.

Conservation status: The Dublin Bay lobster is classified as Least Concern by the IUCN. It is commonly harvested for food, and populations are monitored closely.

Photos

Sue Scott

Institute of Marine Research

Hans Hillewaert

#norway lobster#dublin bay lobster#Decapoda#Nephropidae#lobsters#decapods#malacostracans#arthropods#marine fauna#marine arthropods#benthic fauna#benthic arthropods#deep sea fauna#deep sea arthropods#Atlantic ocean#Adriatic Sea#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology

402 notes

·

View notes

Text

The giant oarfish (Regalecus glesne), also known as the "king of herrings," is the longest bony fish in the world, reaching lengths of up to 36 feet (11 meters). It is a deep-sea species found in oceans worldwide, typically at depths of 650 to 3,000 feet (200 to 1,000 meters). Recognizable by its long, ribbon-like silver body and red, crest-like dorsal fin that runs the length of its back, the oarfish has inspired numerous myths about sea serpents.

Despite its size, the giant oarfish is a harmless filter feeder, consuming plankton, krill, and small crustaceans. Rarely seen alive, oarfish are most commonly encountered when they wash up on shores or are observed near the surface due to illness or disorientation. Their elusive nature and unusual appearance have made them a subject of fascination, often linked to folklore and omens of earthquakes in some cultures. However, there is no scientific evidence connecting oarfish sightings to seismic activity.

credit: David Attenborough Fans.

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Cephalopoda - Nautilida

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Order: Nautilida

Common Name: “nautilus” (pl: “nautiluses” or “nautili”)

Families: 1 - Nautilidae

Anatomy: Smooth external shells with internal chambers, 50-90+ tentacles, toothed radula within parrotlike beak

Diet: crustacean molts, hermit crabs, carrion

Habitat/Range: Indo-Pacific ocean, at depths of several hundred metres

Evolved in: Order Nautilida in the Devonian, Family Nautilidae in the Triassic (230 million years ago)

Propaganda under the cut:

During the Middle Devonian, Nautilus species were more diverse, and their shells were more varied than those found in species of living Nautilus, ranging from curved (cyrtoconic), through loosely coiled (gyroconic), to tightly coiled forms, represented by the Rutoceratidae, Tetragonoceratidae, and Centroceratidae. Only a single genus, Cenoceras, with a shell similar to that of the modern nautilus, survived the Triassic extinction, at which time the entire Nautiloidea almost became extinct. They diversified again, but never reached the extent of diversity they had before the Triassic extinction. The nautilids were not as affected by the end Cretaceous mass extinction as the Ammonoids that became entirely extinct, possibly because their larger eggs were better suited to survive the conditions of that environment-changing event.

Nautiluses are the sole living cephalopods to have external shells. They can withdraw completely into their shell and close the opening with a leathery hood formed from two specially folded tentacles.

The nautilus has the extremely rare ability to withstand being brought to the surface from its deep natural habitat without suffering any apparent damage from the experience. Where fish or crustaceans brought up from such depths inevitably arrive dead, a nautilus will be unfazed despite the pressure change of as much as 80 standard atmospheres (1,200 psi).

Nautiluses have a seemingly simple brain, lacking the large complex brains of octopus, cuttlefish and squid, and had long been assumed to lack intelligence. But recent experiments have shown not only memory, but a changing response to the same event over time.

In a study in 2008, a group of Chambered Nautiluses (Nautilus pompilius) were given food as a bright blue light flashed until they began to associate the light with food, extending their tentacles every time the blue light was flashed. The blue light was again flashed without the food 3 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours later. The nautiluses continued to respond excitedly to the blue light for up to 30 minutes after the experiment. An hour later they showed no reaction to the blue light. However, between 6 and 12 hours after the training, they again responded to the blue light, but more tentatively. The researchers concluded that nautiluses had memory capabilities similar to the "short-term" and "long-term memories" of the more advanced cephalopods, despite having different brain structures.

Female nautiluses spawn once per year and regenerate their gonads, making nautiluses the only cephalopods to be able to breed more than once in their lifetime.

Nautiluses may live for more than 20 years, which is exceptionally lengthy for a cephalopod, many of whom live less than 3 even in captivity and under ideal living conditions. However, nautiluses typically do not reach sexual maturity until they are about 15 years old, limiting their reproductive lifespan to often less than five years.

The osmeña pearl is not actually a pearl, but a jewellery product derived from the iridescent inner layer of the nautilus shell. Nautilus shells are also sold whole, carved as souvenirs, or historically used to make items such as lamps and cups. However, these are not simply shells that wash ashore; the animals are killed for the shell. The low fecundity, late maturity, long gestation period, and long life-span of nautiluses make them vulnerable to overexploitation, and high demand for their ornamental shells is causing population declines. In 2016 all species in the family Nautilidae were added to CITES Appendix II, regulating international trade, though in some places they can still openly be found for sale in tourist areas. The best way to combat nautilus population decline is to stop the demand for these shells.

#animal polls#I’m not gonna lie I have 1.5 nautilus shells in my house 😓#bought them when I was young and before nautiluses were protected#I know better now of course but they’re just… here… on my shelf of skulls and stuff#If you want one I suggest looking in antique and thrift shops so you’re not directly funding nautilus poaching!#don’t buy them from shell shops and other tourist attractions#or Etsy#Round 3#Cephalopoda#Nautilida

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

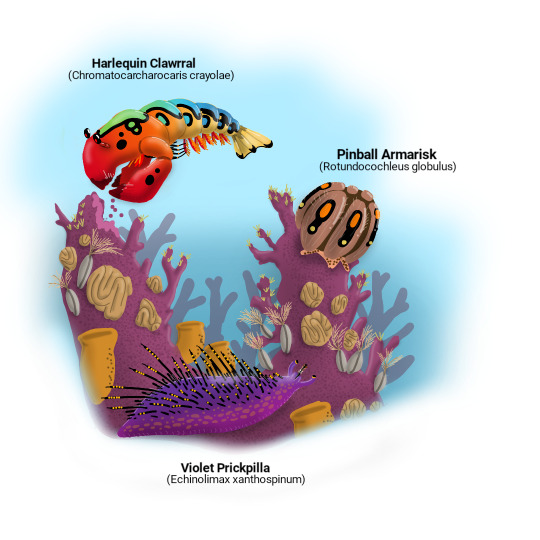

The abundance of coral reefs in the tropical oceans of the Middle Temperocene are conducive to the diversity of all sorts of organisms, all specialized and centered around the calcified skeletons of billions upon billions of tiny polyps. Unsurprisingly, where there is coral, there are plenty of coral-eaters: for where there is a food source left unexploited, a niche will, sooner or later, come to emerge to take advantage of the resource and benefit off of ot to survive.

One of the oldest lineages are the clawrrals: an ancient clade of small shrarks that, rather than using their rostrum and pincer pseudo-jaws for seizing and dismembering active prey, instead specialized upon durophagy, crunching up coral with their powerful tripartite "beak" and feeding on the soft parts within. So successful is this clade that they have endured since the days of the Middle Rodentocene, over 130 million years ago. This is, however, not to say that their survival had been stable throughout, as their diversity have been devastated twice, first in the dawn of the Glaciocene when changing water climates led to a significant die-off of clawrral species due to significant levels of coral bleaching in the regions that became suddenly much colder, and another more recent one in the Early Temperocene, when warming seas devastated those that had adapted to the cold: yet, by luck, some species managed to survive and flourish once more.

The genus Chromatocarcharocaris is one of the most successful of these to survive, and today in the Middle Temperocene number in hundreds of species all across the tropical oceans. These brightly-colored reef species come in all sorts of patterns, colors and shapes, with some species radiating out from coral-eating to other forms of generalized durophagy, including bivalves, quillnobs, and even scavenged bones and shells of deceased marine organisms. The harlequin clawrral (C. crayolae) is a typical member of its genus, ranging across Mesoterra's coast. Like many of its genus, it sports bright colors as a warning to predators thanks to its diet of coral polyps with defensive toxins, which it is immune to and even sequesters in its body to make it highly distateful to predators. Some coral polyps, like other cnidarians, have developed stinging cells as defenses, but the clawrrals in turn have developed a high resistance to them, allowing them to consume a dangerous meal few other competition wants to touch.

A specialization to feeding on the abundant corals of the reefs, however, is no longer the monopoly of the clawrrals. As gastropods became ever more successful in the seas, gradually competing more with the crustaceans, several highly specialized ones also emerged to feed on this abundant, rarely-exploited resource. Violet prickpillas (Echinolimax xanthospinum), a member of a group of shell-less marine gastropods known as the slugworms, similar to the Earth nudibranchs. This species in particular is notable for developing defensive spines in place of a hard shell, allowing it to chew away at coral reefs with little concern. Pre-chewed coral with the softer centers exposed are of particular favor to them, causing them to frequent areas clawrrals inhabit and, preferring different parts of the same food, are able to coexist with minimal competition.

An even more unsual gastropod coexists with these: asterisks, six-armed bottom-feeders vaguely similar to starfish. Yet even that passing resemblance has been lost in the peculiar pinball armarisk (Rotundocochleus globulus), which, while still retaining the six-sided shape has now evolved a hard covering on each side, forming a round, orb-like body with its mouth and foot protruding from the bottom, anchoring it to its feeding surface while its radula scrapes away attached algae and other attached microorganisms onto the coral surfaces. When threatened, it retracts its soft parts inward and closes its six plates to form a near-impenetrable spheroid, dropping to the ocean floor as it does so. Once danger is passed, it begins its slow journey back up to reef to resume its feeding.

As destructive as these organisms may sound, feasting upon the very foundation of the reef ecosystem itself, they are, in fact, now very important to the well-being of the tropical coral reefs themselves. Countless millennia of being fed on relentlessly have caused their favored coral species to grow at a much faster rate, and develop chemical defenses that make them less-ideal homes for other small organisms. By keeping these aggressive, poisonous or even venomous stinging species constantly trimmed, they prevent them from overgrowing the reef and crowding out other, more-amicable kinds that are vital homes and nesting grounds to the other species of the shallow seas.

------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#species profile

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good morning yall! Hope you're ready for a new fish today cuz we got an all timer here today!

Today's fish is none other than my personal favorite fish, the Brook Trout (salvelinus fontinalis)! These beauties are native to Eastern North America, in both Canada and the United States, ranging from Lake Superior, to the coastal waterways from the Hudson Bay to Long Island, though they have spread far beyond their native ranges, mostly via aquacultural practices and artificial propagation, making them invasive species in many regions of North America and the world at large!

Two ecological forms of Brook Trout have been recognized by the US Forest Service, the longer-living potamodromous (fish whose migration occurs fully within fresh water) population, known as coasters , and the anadromous (fish whose migration occurs from fresh water to salt water) population, known as salters. Adult coasters typically reach lengths over 2 feet in length and weigh up to 15lbs, compared to adult salters, which average between 6 to 15 inches and about 5lbs. They're characterized by their vibrant coloration, with olive green bodies and spectacular yellow and blue rimmed red spots, white and black trimming along their orange fins, and dense, irregular lines along the top of their bodies. Often, the bellies of male Brook Trout becomes bright red or orange when spawning.

During the spawning season, female Brook Trout will construct a depression in the stream bed, referred to as a "redd", where groundwater percolates upward through the gravel. Male Brook Trout will approach the female, fertilizing the eggs. The eggs are only slightly denser than water, and can easily be swept away by the current. To avoid this, the female will bury the eggs in a small gravel mound, from which they hatch 4 to 6 weeks later. During this incubation period, the eggs receive oxygen from the streamwater that passes through the gravel beds and into their gelatinous shells. Once they hatch into small fry fish that retain their yolk sack for nutrients, which compensates for the lack of nutrients provided by the parents during the early stages of development. Following the consumption of the yolk, the fry Brook Trout will shelter from predatory species in rocky crevices and inlets, growing from fry to fingerlings, until reaching full maturation at the ripe old age of 6 months.

Despite their native range spanning across low-elevation lakes and watersheds, Brook Trout are increasingly confined to higher elevations in the Appalachian Mountains, especially in southern regions of Appalachia. Over seas, however, Brook Trout have thrived in introduced populations in much of Europe, Argentina, and New Zealand since as early as the 1850's! Their typical habitats include large and small lakes, rivers, creeks, and spring ponds in cold temperate climates. They thrive in clear spring water with moderate flow rates and healthy vegetation populations and other resources which provide natural hiding places. Although they are more resilient and adaptable to varying environmental changes, such as pH levels and temperatures, Brook Trout struggle in temperatures warmer than 72 degrees Fahrenheit. Their diets include aquatic insects at all stages of life, adult terrestrial insects such as grasshoppers and crickets, crustaceans and frogs, molluscs, invertebrates, smaller fish, and even small aquatic mammals such as voles, and even other young Brook Trout! This highly indiscriminate diet and environmental resiliency allows for their success across the globe.

Given all of this, Brook Trout are classified as a Secure by NatureServe's conservation metrics, but that label may be misleading; these incredible fish face severe and repeated extirpation (localized extinction) in many of their native habitats due to habitat destruction, pollution, damming, and invasive species. Meanwhile, Brook Trout present the danger of extirpation to other fish in their nonnative habitats, indicating that efforts must be taken to curb these populations. In short, there are more than enough Brook Trout, but they simply are not where they are meant to be.

A true fish out of (the specifically correct body of) water, the Brook Trout scores within the top percentile of all fishies on our highly advanced fish ranking scale.

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

A shrimp is a crustacean (a form of shellfish) with an elongated body and a primarily swimming mode of locomotion – typically belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchiata of the order Decapoda, although some crustaceans outside of this order are also referred to as "shrimp."

#adheredart#my art#drawing#digital art#clinical trial#clinical trial game#shrimp#lee smith#angel martinez#angelee#the text is literally the first 3 paragraphs of the wikipedia page for shrimp#ctg

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lazing Lagoons

Merformers AU

Jazz x reader

Word count: 2.1k

Warnings: None, Absolute fluff.

Jazz masterlist

Full masterlist

Ask are open, please make,e sure to check my full masterlist and read my rules.

There will most likely be a part 2 to this

_____________

a human stands off to the side of the large outdoor rescue lagoon taking water samples, swirling them in little jars as they write down notes. They slowly step into the water in the shallow end taking coral samples and checking the few Rays which swim closer wanting a treat. The loud sound of water splashing has them tensing up "Don't even think about it!" They call over their shoulder.

A large webbed hand stops mid grab for fish in the bucket on the ledge of the pool.

The large silver and grey Mer surfaces, bright opal like optics flicker to the human as the Mer flashes a grins impishly, razor sharp denta flickering in the low light of the overhang. He swishes his long shimmering tail through the water as he drifts closer to the human who stands there looking mildly unimpressed. "Aww c'mon! Can't blame a mer for tryin'!" He calls back to them, energetically splashing tiny waves at their back.

Surfing nimbly through the shallows, Jazz zooms closer to observe their work on the coral, chin perched casually on crossed arms as he peers over the large reef bed, resting against it while he watches them with the tiny samples. "Whatcha got dere? Find any pretty shells? Ooh lookit dat lil crab!" His gaze darts around watching the crustacean quickly disappear before it becomes a meal.

A sudden flash of movement draws his attention a small silvery fish darting past. Jazz lunges with a playful growl, coming up empty handed as his prey slips through his fingers. Popping back to the surface, he beams unrepentantly at the human's stern glare.

"Aw don't lookit me like dat! Mers gotta eat, ya know!" Jazz swears with a wink and finger gun, before slipping silently back under the water to resume his hunt. In truth he wasn't that hungry but whenever he snuck into the lagoon he took his opportunity to try and snag a fish or two before getting scrolled.

They roll their eyes as a smile falls onto their lips. "You know the carnal isn't there for you to come in here you know, it's so the reef sharks have access to the ocean, and doing ocean releases." They state as they slowly move back to the bucket. Jazz waves a dismissive clawed hand, tails lazily keeping him afloat. "Psh, dem sharks ain't never around." fins flared and pearly teeth flashing. The human huffs out a reluctant chuckle, knowing full well he's the reason for the reef sharks' absence. “Uh huh, Sure you're not just spooking them to steal their fish?” They shoot back, refocusing on labelling samples, but can't help shooting sly glances at the spirited mer.

Jazz notes their amused smiles and beams, pleased as always to coax more positives from the typically stoic human. He swims lazily nearer, laying chin atop dripping arms as big opalescent optics peer owlishly up at them as the work. "Ya know, if yer ever feelin' adventurous enough for a swim with lil ol' me, Betcha ain't never seen the ocean reef like we merfolk do!" The offer, as always, hangs temptingly in the air.

They grab the bucket of fish and begin emptying it into the water, the small fish dart off in different directions into the reef, it makes Jazz's fins flare as his optics narrow as if on the hunt. "Don't eat them, they aren't for you!" They shoot back at him when he begins eyeing some of the colourful mix of reef fish, they splash water at him which earns a loud whine of a thrill from him.

"Awww c'mon, one lil fishy ain't gonna hurt nobody! But you're right, you're right..." he concedes with a sigh. Drifting back closer to the human who continues To watch him to make sure he didn't try and eat the fish meant for the reef.

"You know I swear I'm the only human who has issues with mer trying to get into pools, I swear if I ever told anyone about you they'd want to study why you're so interested in getting in here, bet Seaworld would pay me good money for you as an exhibit" they state in a huff, it was all talk, they would never do that, Jazz was a rather sweet mer, had surprise and scared the crap out of them the first time he ever showed up wanting to steal fish. It had shocked them even more when he had spoken to them.

Jazz at least has the good grace to look abashed at the chiding, schooling his handsome features into an expression of utmost innocence. Flashing a roguish grin, he swims lazy circles around the human, listening with keen interest as they speak. At the mention of study and dissection, his bioluminescent markings flare in alarm.

"Oh no no, we don't be wanting any a' dat study nonsense! Merfolk got our secrets ya know." He waggles his optic ridges. Boldly, he loops an arm around slim waist, drawing them close as a small collection of thrills and clicks leave him.

"How 'bout you just keep ol' Jazz your little secret, hmm? Then we can have all kinda fun exploring together without no pokin' and probin'." He rumbles softly, staring up at them with such optics that shimmer in blues, Greens and purples, it really did give the illusion of Opal in some ways.

After a moment, the human sighs, they flick him softly and turn away from him to put the bucket up. "So what can I do for you, and why are you in the lagoon? Did you drag yourself across the walkway to get in here?, did anyone see you?" They ask with arms crossed.Jazz rubs his forehead ruefully where the human flicked him, grin turning sheepish. Clearly his antics have piqued their curiosity or worry.

He swims a lazy loop in the water, gleaming dorsal fin cutting elegant lines through the water. "Well ya see, I MAY have spotted ya workin' over here and got a lil curious is all." He winks roguishly. "As for why I be here specifically..." Jazz casts a finned hand grandly about the enclosure. "Let's just say a certain lil reef shark was gettin' a bit big for his fins and I decided to, eh, relocate him elsewhere for awhile. No harm done!"

He flashes them a cheeky smile. "An' drag myself across the walkway? Psh, please. With these babies?" Jazz flares his tailfin proudly, fins flowing with iridescent light. "I'd put Aquaman himself to shame! Naw, I just slipped myself on through the current gates when the tide was changin'."

They glare at him " Jazz if you have broken the ocean grate down there in not going to be happy" they state while staring him down. Jazz holds his webbed claws up defensively, fins fluttering in placation. "Now, now, no need to be gettin' all ornery! I wouldn't do nothin' to compromise the barrier, I promise, I have claws i pudit back in place."

He flashes them a pleading look, big opal eyes widening in a manner he knows is hard to resist almost like cat eyes. Circling closer, Jazz gently grasps their wrist, feeling their pulse pound rapidly against his palm. He rumbles low in his chest. "All I wanna do is spend some time with ya."

Gingerly, Jazz lifts their hand to his faceplates, nuzzling gently against their fingers as his biolights dance an invitation. "Whaddya say? Slip in wit me, just for a lil while." Jazz gazes at them pleadingly, hoping his charm can sway them. They let out a sigh as they walk deeper into water. The lagoons were too shallow for a mer his size to be in there too long but he could still swim rather well throughout the lagoons Of the rescue facility.

Jazz's face lights up with unrestrained delight as they move deeper into the water so he didn't have to rest against the bank, willingly engaging with him. With chirps and whistles, he zips energetically around the shallow pool, fins splaying gracefully to manoeuvre his bulk through the tight space.

Jazz makes the most of it, launching up to momentarily breach the surface before slipping smoothly back beneath in a shimmer of chrome and azure. He circles ever closer to the human, radiating calm invitation. "Ain't this fun? Don't gotta go too deep ta enjoy the splash, eh?" Jazz grins, His optics practically glow with joy to have their focused attention.

"You're a pest you know" they state with a barely kept smile. As he slowly drifts closer.

Jazz merely chuckles softly at their halfhearted insult, spark soaring to see the smile they try to conceal. "Aw, but yer smilin' so I must be doin' somethin' right.” They nearly yelp as Jazz pulls them into the water only to land against his chest laying across it as the mer floats peacefully in the pool.

His grin flashes his sharp teeth up at their surprise face as strong arms encircle their waist, drawing them fluidly into the water. Jazz makes sure to keep their head above the surface, securing them safely against his broad frame.

"Oops, lil accident there!" He trills innocently, though his optics glitter with delight. Jazz gently cradles their back, letting them adjust to the cool embrace of the water. "See? Nothin' to worry about with lil ol' Jazz around." He rumbles soothingly, running webbed fingers in slow circles across tense muscles until he feels them begin to relax.

Floating was as easy as breathing for him, he held the human close yet loose, waiting patiently for panic or anger. They let out a grumbled sigh as they relaxed against his frame. One hand hangs over his shoulders in the water as they lay their head up on his shoulder as they both just exist. Floating in the pool as Ray's and fish swim around the lagoon.

In truth they did enjoy his visits, but they fretted over him getting caught by others. They doubted anyone at the refugee would say anything but they didn't want to risk him getting caught, money could make people do alot of things and they didn't want to risk Jazz's safety or his pod.

Jazz's whole frame practically vibrates with subdued joy to feel them sinking into his embrace. One hand rises from the water to gently cradle their back, holding them securely as his claws trail soothing patterns across their back. He nuzzles their head fondly, inhaling the soft scent as his optics close briefly in contentment. Floating here in peaceful stillness.

They cuddle into him. "Do you want me to come swimming with you tonight?" They softly inquire. When they speak, murmuring that tender question, Jazz's spark practically swells until he fears it may burst from his chest. Slowly opening his optics, he peers down at them with such caring and gratitude, it's plain for all to see how deeply he cared for this human and how much they meant to him.

"Ah would be the happiest mer in all the sea if ya did," Jazz rumbles softly, servo coming up to gently cradle their cheek. Leaning in, he presses a chaste kiss to their forehead with a tenderness that belies his brutal strength.

"But only if it's what you truly want. I'd never force ya or put ya in danger, you gotta know that." Pressing their heads together, Jazz cradles them as if the most precious of gems. All he desires is their happiness.

The hum softly against him. "I finish my shift in half an hour, if you can sneak back out without getting caught ill meet you over by the jetty in the mangroves" they mumble softly as they sit up against his frame. "I still have to feed the eels"

Jazz practically vibrates with barely contained elation, optics glowing fiercely as he gazes up at their darling face. All he can do is hold them tenderly and nod. Slowly releasing them to stand, Jazz watches with eager affection as they exit the pool. "I'll be waitin' for ya where the water meets the land, babydoll." He rumbles softly, spark thrilling at the thought of going swimming with them.

Surfacing silently, Jazz offers one last wave before slicing smoothly through the water back down the ocean gate to the reserve's channels, back out to the open sea. Here, under the dusky sky, he lets his joy ring out for all to hear in a joyous chorus of whistles and clicks. Stealthily, he slips into the mangroves' shadowed crevices, ready and waiting for them to finish their shift.

_________

Let me know if you would like to be added to tag list (tagged for every fic)

Taglist

@angelxcvxc

@saturnhas82moons

@kgonbeiden

@murkyponds

@autobot79

@buddee

@bubblyjoonjoon

@chaihena

@pyreemo

@lovenotcomputed

@mskenway97

@delectableworm

@cheesecaketyrant

@ladyofnegativity

@desertrosesmetaldune

@stellasfallow

@coffee-or-hot-cocoa

@shinseiokami

@tea-loving-frog

@aquaioart

@daniel-meyer-03

@pupap123

@dannyaleksis

@averysillylittlefellow

#transformers#transformers idw#transformers x human#transformers x reader#mtmte#transformers gen 1#transformers generation one#idw jazz#tf jazz#jazz transformers#transformers jazz#jazz#jazz x reader#mermaid transformers#merformers#mermaid#mermaid au

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wet Beast Wednesday: krill

The ocean is a huge place and food can be sparse. While the ocean receives plenty of energy in the form of sunlight, that energy needs to be converted into a form animals can consume. This is a job that krill have adopted with gusto. These little shrimpy critters live all over the world and play a vital role in the cycling of energy and nutrients. Krill are among the most common and important marine species, but many people overlook them or think of them as nothing but whale food. let's take a dive into the world of krill to show you that there's more there to appreciate.

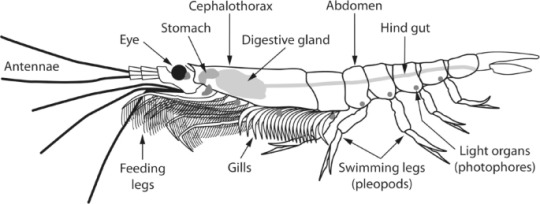

(Image: a side view of an antarctic krill. It is a shrimp-like animal divided into a solid cephalothorax and flexible abdomen. On one end of the cephalothorax are the eyes and antennae and on the underside are multiple pairs of thin, feathery legs and gills. Along the segmented abdomen are paddle-like appendages. The tail is fanned out. The body is translucent with spots of red pigment. The cephalothorax looks green due to the presence of algae in the stomach. End ID)

There are 86 known species of krill in the order Euphausiacea. While they look a lot like shrimp or prawns, Euphausiacea is actually a sister group to Decapoda, which contains the shrimp, prawns, and most other crustaceans you've heard of. Krill can be distinguished from shrimp by the gills and number and anatomy of the limbs. Krill are zooplankton, a description which makes many people think they must be microscopic. In fact, plankton just means an organism is carried around by currents and cannot swim against them and has nothing to do with size. Most krill reach 1 to 2 centimeters as adults, but some species can get larger. The largest species, Thysanopoda cornuta, can reach 9.5 cm (3.75 in).

(Image: a swarm of krill in the ocean with so many members, it makes the water look red. End ID)

Krill anatomy is very similar to that of shrimp. Their bodies are divided into a cephalothorax, flexible abdomen, and tail fan. The cephalothorax is a fusion of the head (cephalon) and thorax. On the head are compound eyes, mouth, and antennae. Emerging from the thorax are legs. These legs are alternatively called pereiopods thoracopods, or thoracic legs. This is one of the key areas where krill are different from decapods. Decapods always have 5 pairs of thoracic legs and at least some of them are adapted for moving around on the ocean floor. Krill have a varying number of these legs and none are adapted for seafloor life. Krill spend their entire lives in the water column. Behind the legs are the gills, which are exposed to the water. The abdomen is long and flexible and has appendages called pleopods or swimmeretes that are used to assist in swimming and moving water over the gills. Decapods also have these. Finally is the tail fan, which is used in swimming and is also found in decapods. Krill exoskeletons are typically transparent with a bit of pigment on the top. All but one species of krill are bioluminescent, though its possible that the bioluminescence comes from their food. Krill have gills that are exposed to the water while Decapod gills are inside of their exoskeletons.

(Image: an anatomical diagram of a krill, with different external and internal body parts labeled. End ID. Source)

Krill are primarily filter-feeders that live in all oceans and in the shallow and deep seas. Most species feed on phytoplankton, especially diatoms, while other are omnivores or carnivores that hunt zooplankton and larval fish. The thoracic legs are covered in filamentous structures and will be held out in a formation called the feeding basket. Plankton passing through the basket will get caught and transferred to the mouth. Krill have a simple digestive tract with a two-chambered gut. The first chamber acts as a mill, crushing the hard shells of the diatoms to make digestion easier. Most krill practice diel vertical migration, a common ocean strategy where animals will remain at depth during the day and move closer to the surface at night. Some species remain in the deep sea all their lives. As krill feed, they become heavier and more sluggish and will sink, allowing the hungrier krill. Krill swim and feed in massive swarms.

(Image: an antarctic krill balanced on a human finger, to show its size. It is barely longer than the first segment of the finger. End ID)

Krill are a vital part of ocean ecology. Energy is introduced to phytoplankton by the sun and used to produce the energy-storing molecule ATP. Krill eat the phytoplankton and convert that energy into a form larger animals can consume and digest. Whales can't gain energy from phytoplankton, but they can get that energy from krill. Krill are a vital food source for baleen whales, seals and sea lions, fish, squid, and other animals. By eating phytoplankton and then being eaten themselves, krill allow that energy to move through the entire food web. Krill also play a role in moving nutrients and carbon through the ocean. Carbon enters the ocean through runoff and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere entering the surface waters. Phytoplankton take in the carbon dioxide and covert it into forms of carbon that other organisms can use. The krill then eat the plankton, taking the carbon into themselves. Through feces, molted exoskeletons, and dead krill, that carbon can sink into the deep sea, where it can become sequestered in the sea floor. Similarly, nutrients can pass from krill to their predators or into the deep sea through feces and remains. Without krill and other animals filling similar roles, carbon and nutrients would have a much harder time reaching the deep ocean and larger animals wouldn't be able to access the energy stored in phytoplankton.

(Image: a diagram showing the highly complex process by which krill assist in moving carbon through the ocean. End ID. Source)

Being animals with exoskeletons, krill have to molt when they outgrow their current shells. Generally speaking, young krill will molt more often than older ones. Most crustaceans will slow down as they age, with each molt occurring further and further apart. This is not the case with krill, which keep molting at a relatively consistent rate through their lives. some species of krill can also get smaller after a molt instead of always getting bigger. This is used when food is unavailable, reducing the amount of energy the animal needs. Some species have been observed going 9 months between meals. Some species can spontaneously molt as a reaction to threats, leaving behind the empty exoskeleton as a decoy for predators.

(Image: a northern krill. It is similar to the antarctic krill, but with a different arrangement of pigment. End ID)

Krill typically mate seasonally, though some tropical species can mate year-round. A female can produce thousands of eggs, which can make up a third of her body weight during mating season. Being a major prey animal, krill need to reproduce rapidly to keep their populations up. Most species will mate and produce eggs multiple times per mating season. Males approach females and deposit sacs of sperm into their genital openings. The females then produce eggs which can be treated in two ways. Most species will release their eggs into the water column and provide no further care. 29 species instead attach their eggs to a sac held by the rearmost thoracic legs and carry them until the eggs hatch. Some of these species hatch at a more mature stage. Once the eggs hatch, they have to swim upwards to reach the photic zone of the ocean, where photosynthesis can take place. Larvae progress through several developmental stages. Like other crustaceans, they start as a napulus larva, though some sac-brooders will hatvch at the more advanced pseudometanapulus stage. Either way, they progress then to the metanapulus stage. At this stage, they can lo longer subside on yolk and must reach the photic zone and metamorphose into the calyptosis stage, the first stage with a mouth, before starving. The final larval stage is called the furcilia, which passes through a number of molts. During each molt, the abdomen will grow another segment and pair of swimmeretes. After the final furcilia stage, the krill will resemble a small adult. Krill life spans vary baes on species, from less than a year to 10 years, with species in colder water usually living longer. Relatively few krill will die of old age. In the antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, over half the population is eaten every year.

(Image: several stages of krill development form egg to napulus to more advanced larval stages that look like the adult. End ID. Source)

Krill conservation needs vary by species, but in general, they are highly abundant and in little danger of extinction. Krill are among the most abundant animals in the world, with antarctic krill having one of the largest total biomass of any animal. Monitoring the krill population is extremely important because of their importance to the global ecosystem. Krill have been fished commercially for centuries, used as food, bait, supplements, animal feed, and for shrimp paste and fish oil. Most krill fishing takes place around Antarctica as the krill there are highly abundant and seen as cleaner. As the krill fishery grows, more studies need to be done on the impact on the population and the other species that rely on them. Krill are also impacted by global climate change, ocean acidification, and pollution. Krill can ingest microplastics, which can then be passed onto whatever eats them. Krill are keystone species, meaning they are crucial to the health of their environments. If they go, massive parts of the ocean ecosystem will collapse.

(Image: someone holding a pile of dozens of krill in their hands. End ID)

#wet beast wednesday#biology#ecology#zoology#marine biology#animal facts#invertebrates#invertiblr#crustacean#krill#antarctic krill#informative#educational#image described

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jellies are trending 🙌🏼

Everyone is familiar with the basic idea of a jellyfish, but what do we mean when we use that term? Jellies in the class Scyphozoa include most of the species that people think of when hearing the word “jellyfish.” Their life cycles typically include a polyp stage, attached to the bottom, that produces baby medusae. When conditions are right, these babies can grow up to form vast blooms of adult jellies. These "true jellies" are commonly studied at the sea surface, but those living deep in the water column are less well known. Some deep-sea jellies defy what we imagine when we think of jellyfish—some with bells that can stretch up to a meter across, others with no tentacles at all. Many species of swimming jellies are actually in another group called the Hydromedusae. These jellies are often small and transparent, ranging from very few to numerous tentacles. Some Hydromedusans have tentacles that point ahead of them instead of trailing behind them as they swim. These species eat other gelatinous organisms rather than the crustaceans favored by many of their cousins. Even with all this dazzling diversity, we have yet to encounter many of the delicate drifters that live in the deepest waters of our vast ocean.

761 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incostanza, An Allegory of Fickleness

Artist: Abraham Janssens I (Flemish, 1575–1632)

Date: c. 1617

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark

Description

The present painting shows “fickleness” in keeping with the era’s code books of symbols in art, where the semi-clad woman, the ever-changing moon, and crustaceans - capable of walking sideways - serve as markers for those of a mercurial temperament.

The artist, moved by a visual desire that we would now term voyeurism or fetishism, focuses intently on her breasts, which shine with a brightness even greater than that of the crescent-moon face she holds in her hand.

The breasts are associated with other feminine characteristics: with bodily matters, impulsivity, and the subconscious as well as with fertility and pregnancy.

The woman may be attractive, but she is also potentially dangerous. In contrast to the moon, the sun was typically a symbol of maleness and masculinity, i.e. of intelligence, will, exaltedness, and divinity.

#allegorical art#painting#oil on anvas#allegory of fickleness#inconstanza#woman#semi clad woman#moon#crustaceans#rabbit#abraham janssens i#flemish painter#flemish art#netherlandish#european art#artwork#oil painting#17th century painting

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

On the topic of baby shirmps

I LOVE SHIRMPS SO MUCH SOMEONE STOP ME BEFORE I BREAK MY PHONE

The shirmps already come with that working mentality to go clean (IT IS SO CUTE TO SEE A SMALL SHIRMP DOING THE SAME THING AS THE BIGGER SHIRMP AAA) I am thinking that maybe now yuu is a shrimp merperson but they got eels in them would the kids come out as mixed? Maybe one of them is a shirmp but with the colors of the twins and there is also a moray eel but with the bright colors of shirmps

WHAT I WAS GETTING TO is that maybe since kids can be shirmp or eel that the baby shirmp just out of nowhere starts doing that cleaning motion and their moray eel sibling is confused about it (sort of how some cats are raised with dogs so they copy some of their characteristics)

The moray version of confusing the hell out of their shirmp sibling is that one day the eel sibling tied themselves into a knot and they go "????"

-Vaquita

Also that idea is so fucking good oml in the sweet side consider mereggs glow when in touch with their parents (the fishy way of a baby kicking)

THATS SO CUTE AAAAAAAA BABY SHRIMP BABY SHRIMP BABY SHRIMP

I like to imagine that a shrimpmer Yuu would be a Pacific cleaner shrimp, which are the ones most often found around morays. They're a bright red with a singular white stripe down their back with very long antennas:

I think that for the babies, the easiest route to take is either a moray kid or a shrimp kid in either teal or red colors. We can imagine how a hybrid might work, but that requires more time that I don't have atm to write.

I think that the moray babies would be curious of their shrimp siblings, especially when they start mimicking their shrimp parent's mannerisms and “cleaning”. They think it's cute, and the moray siblings are a great practice for cleaning for the baby shrimps! Plus, that means less work for Yuu in the long run.

On the other hand, I think the shrimp babies are confused by their moray siblings' predatory instincts. Baby morays feed on mostly small raw fish and crustaceans (like shrimp) until they get more teeth in and are able to eat larger chunks of fish provided by their fathers. The shrimp siblings get weirded how seeing their siblings feed on their animal counterparts.

Though, they all get along and like to compare their colors to each other! Some of the morays are a deep red not typically associated with morays, while a few of the shrimps are a combination of teal and red, making them look a bit like a mosaic! And, of course, all of them glow when feeling strong emotions. Mostly happiness though, they're very spoiled and cherished.

This is why they love to clutch onto Yuu when they carry another batch of eggs. Their siblings glow whenever they rub Yuu's tummy and say hello! What a sweet sight that must be!

(I have many thoughts about this, it might have to become a series at some point tbh)

#mochi asks#twst#twisted wonderland#jade leech#floyd leech#twst x reader#twisted wonderland x reader#jade leech x reader#floyd leech x reader#vaquita anon

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Dive into the Diving Spider

The diving spider, or water spider (Argyroneta aquatica) is perhaps one of the most unique arachnid species on Earth, noted for living almost entire life completely underwater. This species is found throughout northern Europe and Asia in clear freshwater ponds, lakes, wetlands, and slow-moving rivers with lots of aquatic vegetation.

Like other spiders, the water spider does breathe air. When submerged, specialized hydrophobic hairs create an air bubble attached to its abdomen, which allows the spider to store oxygen while moving around underwater. In addition, these spiders build a web known as diving-bell webs. These webs, constructed of spider silk, are constructed underwater, and supplied with air bubbles from the surface. A. aquatica spends most of its time in these webs, leaving only to replenish its air supply-- about once every 24 hours-- or to find prey.

The diving bell spider's prey are, unsurprisingly, primarily insects. In particular they feed on water fleas, aquatic isopods, insect larvae, and small crustaceans like shrimp. Individuals catch their prey by hiding inside their webs until prey trips one of the trip-wires constructed in the surrounding vegetation. They then surge out, seize their prey, and drag it back into the air-filled web where the spider can digest it. Predators of water spiders include aquatic beetles, dragonfly larvae, and frogs. Fish can also predate upon water spiders, but they are usually scarce due to the low aquatic oxygen environment in which the spiders live.

Ordinarily, A. aquatica is a fairly plain, brown spider. Males are slightly larger than females; 18.7 mm (0.74 in) to their 13.1 mm (0.51 in) in length; this is a rare phenomenon in spiders, as females are typically larger. Males also have a longer pair of front legs. However, females were found to construct much larger nests, as they must also provide space for their eggs and young.

When a male is ready to mate, which occurs during spring, he will construct several sperm packages that he holds in his palps, or mouth appendages, while he seeks out potential mates. If he finds a receptive mate, the two will engage in a swimming ritual around her web before he gives her one of his sperm packages. Afterwards, the female constructs a sac with 50-100 eggs; she may do this up to 6 times throughout a single year. The eggs hatch 3-4 weeks after laying, and the offspring remain in the nest for another 2-4 weeks. Individuals typically become sexually mature not long after, and may live up to 2 years in the wild.

The water spider can deliver a painful bite, with symptoms of inflammation, vomiting, and fever lasting 5-10 days. However, the bite is not known to be fatal to humans.

Conservation status: The diving bell spider has not been evaluated by the IUCN. The primary threat is likely habitat destruction, although at least one area in South Korea has been designated specifically as protected habitat for the species.

Want to request an uncharismatic critter? Just send me proof of donation to any of these vetted fundraisers for Palestinian refugees!

Photos

Stephan Hetz

#water spider#diving bell spider#Araneae#Dictynidae#spiders#arachnids#arthropods#invertebrates#freshwater fauna#freshwater arthropods#freshwater invertebrates#lakes#lake arthropods#lake invertebrates#wetlands#wetland arthropods#wetland invertebrates#europe#asia#northern europe#northern asia#animal facts#biology#zoology#ecology

198 notes

·

View notes