#north island giant moa

Text

Oh, extinct birds, how I love you and miss you.

In order:

White swamphen (Porphyrio albus), native to Lord Howe Island

Huia (Heteralocha acutirostris), native to Aotearoa New Zealand

Dodo (Raphus cucullatus), native to Mauritius

Laughing owl (Ninox albifacies), native to Aotearoa New Zealand

Mysterious starling (Aplonis mavornata), native to Mauke

North Island giant moa (Dinornis novaezealandiae), native to Aotearoa New Zealand

O'ahu 'ō'ō (Moho apicalis), native to O'ahu

[Image IDs in alt text.]

#extinction#extinct animals#extinct birds#watercolor#scientific illustration#white swamphen#huia#dodo#laughing owl#mysterious starling#giant moa#'o'o#artaneae

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

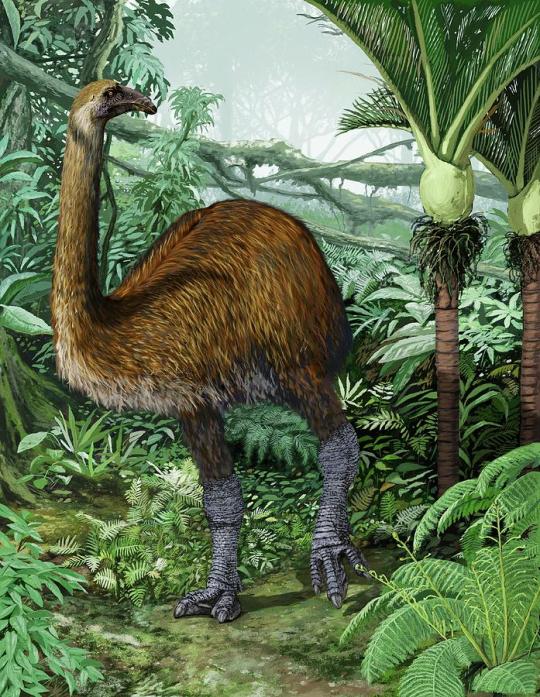

Today's Novembirb is the North Island Giant Moa!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinornis better known as the Giant Moa is an extinct genus of birds belonging to the moa family of the suborder order Dinornithiformes, a group of large flightless birds which lived on the islands of New Zealand some 2 million to 500 years ago. There are 2 currently recognized species the North Island giant moa (Dinornis novaezealandiae) and the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus). These diurnal avians tended to be found in the lowlands of there island homes inhabiting Shrublands, Grasslands, Coastlands, and Forests where they occupied the niche of large terrestrial browsing herbivore similar to certain antelope, bovines, cervids, and giraffes of today, feeding upon Twigs, seeds, berries, leaves, flowers, fungi, vines, herbs, and shrubs. In life giant moas displayed a large reversed sexual dimorphism whereby the females were up to twice the size of males. With males reaching around 5 to 6.5ft (1.52 to 1.98m) in height and 120 to 195 (55 to 88kg) in weight, and females reaching roughly 10 to 12.5ft (3.05 to 3.81m) in height and 170 to 550lbs (78 to 250kgs) in weight these birds where amongst the largest to ever exist, with the North Island Giant Moa currently holding the record of the tallest bird ever and the South Island Giant Moa being the second tallest. However both are beaten in terms of weight by there fellow recently extinct ratite the elephant bird. Dinornis had long slim, elongated bones compared to other moa species, Maori historical accounts describe the animals as tall, two legged, tailess, wingless giants with slender necks. Brown, slightly streaked, downy, wool like feathers covered all of there bodies sans there heads, feet, and part of the neck. It is believed that the settlement of New Zealand by the Maori directly lead to the Moas extinction, as they were extensively hunted for there meat and feathers. Whats possibly more devastating was the introduction of Polynesian rats and dogs which likely destroyed moa nests and killed moa chicks faster than these large birds could mature and reproduce.The last of the giant moa likely died out around 1500 C.E. with the last species of smaller Moa the Upland Moa possibly holding out until the 1800s.

Art used belongs to the following creators:

Giova Favazzi

Mark Witton

Jaime Chirinos

Gabriel N. U.

Dana Franklin

#pleistocene pride#pleistocene#pliestocene pride#cenozoic#ice age#stone age#pliestocene#bird#dinosaur#giant moa#moa#new zealand#extinct

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The abundance of megafauna in various parts of the world (at least counted when agriculture and cities appeared) is basically a measure of how long Homo sapiens has existed there.

Africa was the continent of our origins, and it still retains mostly of its Pleistocene megafauna -- lions, elephants, rhinos, giraffes, hippos, gorillas, buffalos, the works. Even ostriches, when flightless birds are usually first to go. That's because African macroanimals evolved alongside with humans and had time to adapt (mostly by being incredibly pissed off at everything that exists in their general neighborhood).

Eurasia came next, being only colonized in the last 70,000 years or so, and it still retained some large species, like bears, horses, deers, wolves, etc. Australia and the Americas are next, both colonized from Eurasia some 50,000 and 20,000 years ago, respectively. Australia still has a lot of large reptiles because they survive on little food, but its mammalian and bird megafauna were nuked; kangaroos are the only native Australian mammals above a few dozen kg. Same storyfor South America. North America did a bit better because historically (I mean, Deep Time historically) it's been more or less continuous with Eurasia, rather than a fully independent landmass.

Then the small islands come -- Madagascar, New Zealand, the Hawai'i -- all settled in historical times (the Maori look like they should have been in New Zealand since the dawn of the world, but in fact they only got there during the European late Middle Ages). Their megafauna, moas and giant lemurs, was utterly wiped within centuries. There are tiny oceanic islands like the Mauritius (home of the dodo) that were only reached by European navigators in the last 2 centuries, but most of those barely had any macrofauna in the first place.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝚍𝚎𝚟𝚕𝚘𝚐_𝟶𝟸.𝟷

Moa's Ark & Zealandia

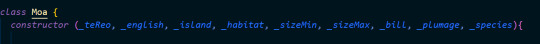

https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/moas-ark-1990/series

Moa's Ark (1990s TV series) opening animation. It was during the 90's that scientists formulated the "Zealandia" protocontinent theory and complexity of how species migrated over time, putting the last nail in the coffin of the idea that everyone got a free ride over on a piece of Australia. Going through Aotearoa's natural history doco archives has been a lot of fun.

Hello again! I took a bit of a break in posting long- form updates, but I think there's enough on my mind for a second batch of posts this week. After that there will again just be small updates on the Instagram until May - when I may have some sort of concept media for the sim to show off. For now I'll aim for a focused peek into a couple of aspects of it as usual.

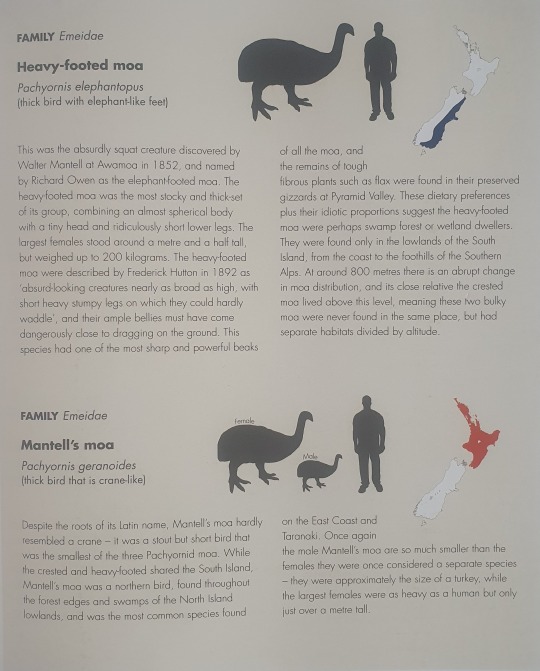

This post is going to be all about the Moa, the species that got me hooked on this project. It's also going to be about species variation, and the tension between scientific accuracy and visual accessibility.

Moa skeletal reconstitutions at Te Papa Tongarewa, Museum of New Zealand.

A couple of interesting facts about the moa;

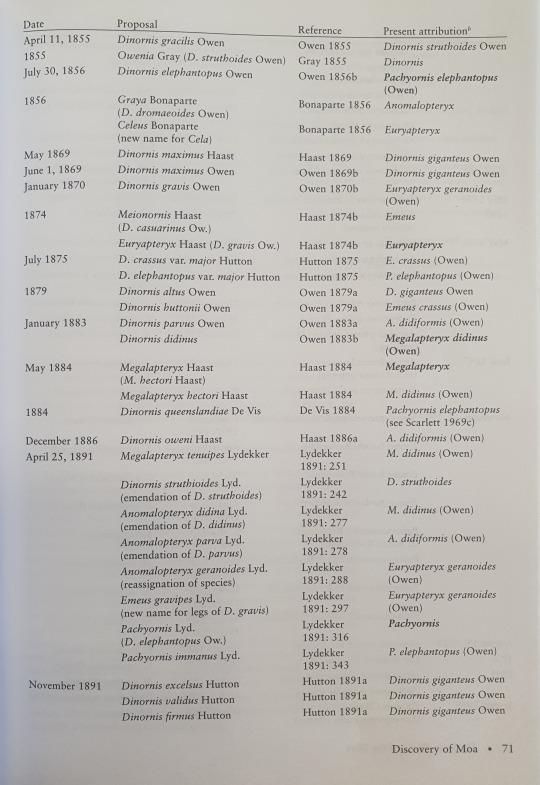

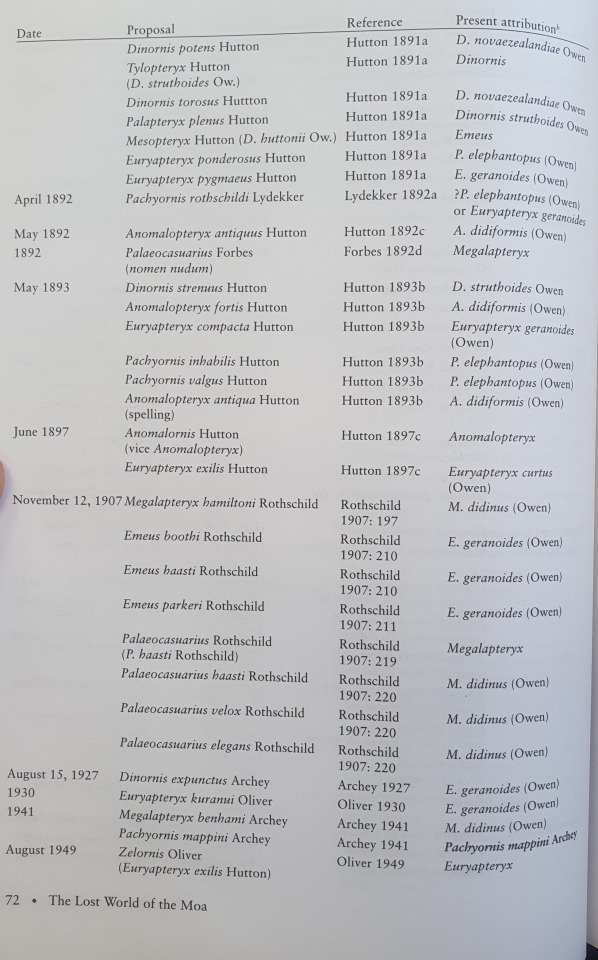

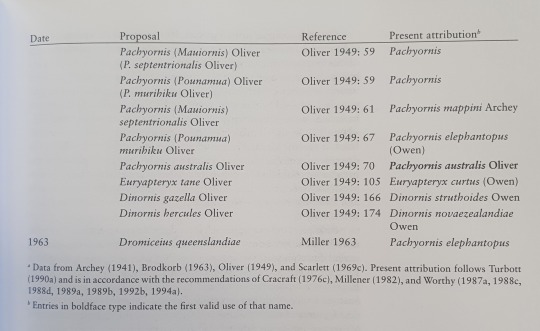

-We currently classify them as nine species. Here is a full catalog of every time someone thought they'd found a new one:

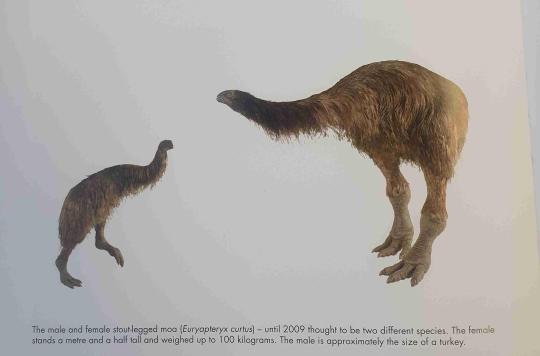

-Within many species, female moa can be more than twice the size of males (yes, this is one reason so many moa "species" were identified)

-Moa are unique in that they had no wings (not even the kiwi's tiny t-rex stubs) and, thank goodness because so many NZ species can be traced back to evolving from Australian fauna, their closest past relatives are South American tinamous rather than the emu.

-They also got a bad wrap for their past perception as tall, emu- like, big dumb grass grazers. Actually, while they're nowhere near as smart as multi-sense-foraging kiwi, they could identify and feast on a whole variety of twigs, herbs, leaves and berries - most of which were found in the more common forest than grassland.

This is why they have a bulky build and head-forward posture (until kinda recently, museum curators tended to give them that tall, emu/giraffe like posture, even adding extra vertebrae for show.)

Whanganui Regional Museum (This isn't close to the worst examples)

So; how do I even begin to approach the scope, as well as potential uncertainty, of data we have on the Moa?

Here's one way: Oversimplification!

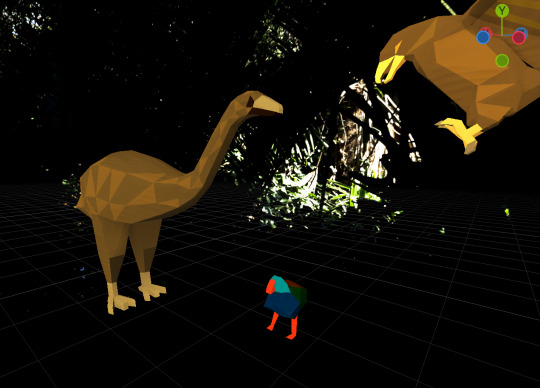

Screenshots from Godot editor & runtime previews for compatibility (web) mode and forward+ (basically more shaders) renderer. The camera is RTS- style; getting the runtime shots was a bit finnicky.

I've started to build low-poly models in Blender for the fauna, which in the future I'd love to rig for animation and get super technical with appearance variation. For now I'll focus on the system for placing them in the right biome and basic pathing behaviour, and the Moa will be a North Island giant moa based vaguely off this model for an AR national park exhibit: https://moaparkotorohanga.wordpress.com/2014/07/08/a-collection-of-moa-feedback-from-trevor-worthy-and-lizzy-perrett/

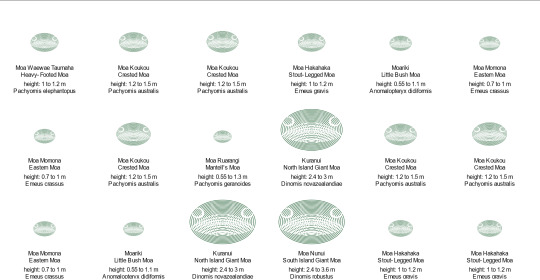

While I'm not working directly on the simulator for the next while, I am building this 2D tool to represent the moa's species variation; it is *incredibly* helpful to have just set up a system where I can add and edit instances of a broader Moa "class", and I'm looking forward to giving each species its visual character (the main creative liberty I'll be taking is colour coding from grey to brown to communicate which of New Zealand's islands each species populated, as well as their preferred biome (there's 3 main ones: subalpine mountain, wet podocarp forest, dry forest/ lowland)

Moa "collection" project at time of writing.

If this exercise has highlighted anything though, it's just how difficult it is to reduce life's complexities to a single shape that represents a single numeric value. Those who read my last posts may remember that any given moa species' size may have varied over time and with temperature, (generally bigger during ice ages and smaller out of them) along altitude, (generally bigger and bulkier higher up) and just within species based on how they adapted to any given place. Not to mention the relatively massive lady moa.

And since we're only working with what's left of them all - the only intact gizzard samples proving that whole diet theory, and most of the remains we have to work with, are those found in Pyramid Valley in Canterbury (a swamp with surrounding mosaic of vegetation and forest) - who knows how to truly depict what life was like tens of thousands of years ago.

From the Moa book by Quinn Berentson

A very cursed JavaScript "spreadsheet".

So, very long-winded post. I hope you found something interesting within! Something that made you think about nature's craziness maybe. I meant to get across just how much there is to scientific communication, and I barely touched on how I aim to keep the overall narrative in focus (or basically be aware of it.)

I can't wait to work on this more collaboratively, with folks who really know their stuff about ecology and the cultural aspects of Aotearoa - I think the potential for collaboration and education is what's keeping me going with this project.

Until next time ! - here's some of my highlights from a trip to the Zealandia ecosanctuary.

Kia hora te marino

Kia whakapapa pounamu te moana

Hei huarahi mā tātou i te rangi nei

Aroha atu, aroha mai

Tātou i a tātou katoa

Hui e! Tāiki e!

May peace be widespread

May the sea be like greenstone

A pathway for us all this day

Let us show respect for each other

For one another

Bind us all together!

#devlog#gamedev#indiedev#programming#birblr#moss#plants#aotearoa#oceania#natural history#nature#godot engine#javascript#ecology#science

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Section 9 / The De-extinction Labs

General Layout:

Every aspect of Section 9 is inside of a large, eleven-story building. Each of the enclosures and tanks are set up for specific species from across the world, giving the section a mixture different environments from mountainous ranges and open plains to dry deserts and damp marshlands.

The section's halls are marked with signs. Guests can also get around by taking the section's underground trains.

There's a wide variety of restaurants, gift shops, and amenities, within the section, along with lab tours, fossil digs, and learning centers.

The Animals:

Amphibians: Golden Toads, Mountain Mist Frogs, Scarlet Harlequin Toad, and Yunnan Lake Newts.

Aquatic/Semi-Aquatic Mammals: Caribbean Monk Seals, Japanese Otters, Maui Dolphins, Sea Minks, Steller's Sea Cow, and Vaquita Porpoises.

Birds: Broad-billed Parrots, Carolina Parakeets, Cuban Macaws, Dodos, Great Auks, Kākāpōs, Laughing Owls, Mauritius Blue Pigeons, North Island Giant Moas, Oʻahu ʻakialoa, Oʻahu nukupuʻu, Oʻahu ʻōʻō, Passenger Pigeons, and Philippine Eagles.

Insects: Rocky Mountain Grasshoppers, Laysan Weevils, Saint Helena Earwigs, and Xerces Blue Butterflies.

Fish: Blue Walleyes, Chinese Paddlefish, Gravenches, Java Stingaree, Tecopa Pupfish, Thicktail Chubs,

Misc. Carnivores Animals: Amur Leopards, Falkland Islands Wolves, Formosan Clouded Leopards, Saber-Tooth Cats, Tasmanian Tigers, Zanzibar Leopards

Misc. Herbivorous Animals: Atlas Bear, Aurochs, Bluebucks, Bubal Hartebeests, Carpathian Wisents, North African Elephants, Northern Hairy-nosed Wombat, Pygmy Three-Toed Sloths, Quaggas, Saolas, Schomburgk's Deer, Toolache Wallabies, and Wooly Mammoths.

Other Animals: Acorn Pearly Mussels

Primates: Bornean Orangutans, Gigantopithecus Blackis, and Hainan Gibbons.

Reptiles: Domed Mauritius Giant Tortoises, Domed Rodrigues Giant Tortoises, Hanyusuchus, Hawksbill Sea Turtles, Pinta Giant Tortoises

Rhinoceroses: Javan Rhinoceroses, Northern White Rhinoceroses, Southern Black Rhinoceroses, and Western Black Rhinoceroses.

[Amur Leopards, Bornean Orangutans, Hainan Gibbons, Hawksbill Sea Turtles, Kākāpōs, Javan Rhinoceroses, Maui Dolphins, Northern White Rhinoceroses, Northern Hairy-nosed Wombats, Philippine Eagles, Pygmy Three-Toed Sloths, Saolas, Scarlet Harlequin Toads, and Vaquita Porpoises]

#highlighted & bracketed animals are ones currently facing extinction (as of 5/19/2024)#the series is set in 2056#the butterfly's effect#notes#writers on tumblr#writeblr#writblr#writers#writing#current wip#wip#work in progress#extinct animals#extinct species#extinction#prehistoric animals#prehistoric#recently extinct#critically endangered#endangered#endangered species

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teppanya Launches Super Premium Unlimited Madness Menu at Its Newest Branch in Mall of Asia

Our favorite Teppanyaki restaurant has just opened a bigger and better branch at the SM Mall of Asia and it promises to deliver a spectacular dining experience for all its guests. Teppanya has been an enjoyable indulgence for us ever since we first discovered its unlimited teppanyaki promotion at SM North EDSA a couple of years ago (Read: Teppanya Launches 5th Anniversary Unlimited Madness Promo). We kept going back to Teppanya even during the pandemic years so we were happy to find out that they recently opened a new branch with a new premium VIP menu that will beat even five-star hotels in the city.

The newest branch of Teppanya is located at Seaside By The Bay in SM Mall of Asia, just in front of the MOA concert grounds. This is actually a more accessible location since you can just park your car in front of the restaurant or at the open parking lot right across. It is also their first branch that is not directly inside a mall so you can expect to find a bigger and grander venue when you visit.

Similar to their other branches, the MOA outlet features all teppanyaki tables so each guest can get the full Teppanya experience up close. This location is much more spacious as it comes with 14 teppanyaki tables all custom-made for your dining pleasure. Teppanya MOA can accommodate over 200 diners but they still get long lines especially during weekends and holidays.

They also have several private dining rooms which can accommodate up to 12 guests, each with its own dedicated teppanyaki table and chef. These can be booked with a minimum consumable amount of P20,000.

Teppanya has an a la carte menu serving premium Japanese dishes including sushi, tempura, tonkatsu and more, but what really made them famous is their Unlimited Madness promotion. Starting at P1988+ per person, you can eat all the teppanyaki and Japanese items that you want. This is available daily for lunch from 11:00am to 3:00pm and for dinner from 4:00pm to 12:00mn.

But for today, The Hungry Kat was invited for a special preview of their new Super Premium Unlimited Madness menu which will come with all their usual teppanyaki dishes plus unlimited servings of A5 Wagyu, Alaskan Snow Crabs, Foie Gras aburi sushi, premium Iberico Pork, and more!

We were seated at one of their private dining rooms with a magnificent view of the bay. This is also a connecting private room so you can combine it with the other room for those big parties and gatherings.

Dining at Teppanya always starts with a fiery exhibition from the talented teppanyaki chefs. The interactive dining experience is what makes this unique from other eat-all-you-can buffets.

While the chef was busy setting up the table, we were given a few starters which included this magnificent Otoro Sashimi. The otoro comes from inside the tuna's belly and is the most desirable and most expensive part of the fish. The sashimi is so fatty that it almost melts in your mouth.

The chef then prepared his first dish, the Wagyu Usuyaki Roll which is an upgraded version of the Usuyaki Beef Roll served on the regular menu.

The Wagyu Usuyaki Roll is cooked and assembled right on the grill. This meaty roll comes with mushroom and veggies that is placed inside a savory wagyu beef. It is then topped with garlic chips and doused in their secret sauce. This is a very delicious and filling appetizer.

Next is the Wagyu Aburi and Wagyu Aburi with Ikura or salmon caviar. This bite-sized wagyu sushi comes with tender slices of wagyu lightly torched to bring out more of its umami flavors.

The Hokkaido Giant Scallop is a huge piece of scallop which came all the way from the waters of Hokkaido island in Japan. These plump and juicy scallops are cooked on the teppanyaki grill then served back on their half shells.

Another premium seafood item is the Wild Alaskan Snow Crab. Its sweet and tender crab meat is really good which also makes it quite expensive. That's why it's very seldom to find these exquisite items at an all-you-can eat menu.

Here's a very luxurious sushi trio called the Emperor Aburi Set. It comes with Wagyu with Black Truffle, Foie Gras, and Unagi sushi. The foie gras is topped with gold flakes while the wagyu itself comes with a slice of truffle. You really can't get a more premium sushi lineup than this.

The chef continues to demostrate his acrobatic skills using the egg while preparing our Chahan Mixed Fried Rice. Expect to see these entertaining performances from the teppanyaki chefs throughout your meal which the kids and adults alike will surely love.

The chahan is a mixed fried rice cooked with beef, chicken, and shrimps. You can also opt for the Seafood Chahan which has scallops and shrimp instead.

The highlight of the new super premium Unlimited Madness menu are the wagyu steaks. Let's start with the Australian Darling Downs Wagyu MB5 Picanha which really looks good even before it is cooked. The picanha is a tender and juicy cut of beef taken from the top of the rump.

The teppanyaki chef works his magic and grills the wagyu steak delicately. You can really taste the difference of the texture and flavor with each bite.

Another premium meat served to us was the Iberico Secreto Steak which is often called the wagyu of pork. This very tender and flavorful pork comes from a thin cut of meat hidden behind the shoulder blade of an Iberico pig. It tastes just as heavenly as the wagyu beef!

The Australian Duck Breast Fillet was another standout dish. I do love eating roasted duck but this is another outstanding way of presenting this meat.

We all like to eat sandwiches but the A5 Wagyu Sando is truly a cut above the rest. This beef sandwich comes with A5 grade wagyu and is topped with gold flakes.

They saved the best wagyu for last with the Japan Miyazaki Wagyu A5 Chuck-Eye Steak and the Japan Miyazaki Wagyu A5 Chuck Strip Steak.

We were truly in wagyu heaven with these two high-grade items with a Beef Marbling Score of 8-9 signifying wagyu of the highest quality. We were already quite full but we couldn't resist having more of these luxurious wagyu.

To end our special tasting menu, we had a cold ice cream dessert that was cooked on the teppanyaki grill! The Banana Flambé comes with caramelized banana strips grilled on the teppan table and then topped with vanilla ice cream. This was then flambéed and drizzled with chocolate syrup and tempura bits for the most indulgent teppanyaki dessert ever.

The new Super Premium Unlimited Madness Menu will be available soon for P4988+ per person at Teppanya Mall of Asia and its other branches. We would like to thank the owners of Teppanya especially Mr. and Mrs. Pineda for hosting our small media group. Teppanya Mall of Asia is an exciting new dining destination that will definitely impress families, kids, esteemed guests, and everyone else that will experience its fiery offerings. I'm already eagerly waiting for the opening of their next branch at the Shangri-La Plaza Mall later this year.

Teppanya Mall of Asia

Unit 1-6 SM Seaside by the Bay, SM Mall of Asia, Pasay City

8571-9390 / (0915) 2683108 / (0962) 0643104

www.facebook.com/TeppanyaphMOA

1 note

·

View note

Text

2 New Zealand: Sloshing through the South Island

As long as there is wilderness there is hope. I went southwest from Christchurch to Queenstown, at the edge of the waterworld of Fiordland. Even today it is one of the world’s last wildernesses. But a thousand years ago, before the arrival of any humans, it was like the world before the Fall.

Then, there were no predators except falcons, hawks and eagles – no meat-eaters. There were no browsing mammals, no land mammals at all, apart from two species of small bat. Everything grew and flourished, and the weather came up from the Roaring Forties, watering this corner of New Zealand with twenty-five feet of rain a year. It is still one of the wettest places in the world.

It was once so safe here that the birds lost their sense of danger, and without enemies some stopped flying – among them, the flightless New Zealand goose and the Fiordland crested penguin, now extinct. Others evolved into enormous and complacent specimens, like the spoiled and overfed children I have seen in Auckland – the giant rail, more than a yard tall, or the feathered long-necked moa, a distant relative of the emu and the ostrich and Bid Bird, which grew to be ten feet tall.

In that old paradise the trees grew abundantly and the moss was two feet deep – a perfect seabed for new trees. The creatures lived on roots and insects, and not on each other. The foliage grew without being cut or grazed. Fiordland which had been created by glaciers, was the Peaceable Kingdom.

After the Maori arrived, probably in the tenth century, from the Cook Islands in tropical Polynesia, with the dog (kuri) and the rat (kiore) they kept for food, they made forays into Fiordland from the north. They had a great love for decorative feathers, and in their quest for them, and for food, they hunted many birds to extinction. The Maori dogs and rats preyed on the ground-dwelling birds. For the first time since its emergence from the Ice Age, Fiordland’s natural balance was disturbed. The arrival of these predators produced the ecological equivalent of Original Sin.

There were always treasure-seekers in Fiordland – Maoris looking for feather and greenstone, pakehes (whites) looking for gold – but such people were transients. Fiordland never had any permanent settlement, only camps and way stations and temporary colonies of sealers and whalers at the edge of the sea. People came and went.

Fiordland remained uninhabited – a true primeval forest.

But the humans who passed through left many of their animals behind. They introduced various species either for sport or food, or in the mistaken belief that one animal would stabilize another. The pattern is repeated all over the Pacific – there are wild goats gobbling up Tahiti, and wild horses chewing Marquesas to shreds, wild pigs in the Solomons, and sneaky egg-eating mongooses, presented to the islands by missionaries, all over Hawaii. The rabbits and wild dogs in Australia did so much damage that a vermin-proof fence was put up across New South Wales that is longer than the Great Wall of China.

The foreign animals brought chaos to Fiordland. When the rabbits went wild, the stoats and weasels were introduced to keep them in check, but instead they ate birds and bird eggs and the rabbits increased. Every other non-native creature was similarly destructive. The New Zealanders I met hated these foreign animals even more than the islanders, but they hated them for the same reasons – because of their indecent fertility and their breeding habits and their excessive greed, eating everything in sight.

The greatest threat to vegetation was the red deer. Deer breed quickly and can go anywhere. Helicopters flying over almost inaccessible hanging valleys could spot three to four hundred deer in the steepest places. The Norway rats that came to New Zealand on ships have multiplied and reduced the native bird population. There are American Elk in Fiordland, the only herd in the Southern Hemisphere.

“They’re a nuisance,” Terry Pellet told me. He was the District Conservator of Fiordland. “There are so many exotic species that thrive here and harm the local flora and fauna – possums, chamois and hares.”

And the Germans, he said, were terrible about paying hut fees.

What is native and what is alien is a Pacific conundrum.

In New Zealand all strangers were suspect, whether they were animal or vegetable. You can shoot a red deer any day in Fiordland and it is always open season on elk.

Foreign trees are regarded as unsightly weeds, whether they are Douglas fir, silver birch, or spruce, and no growing things are hated more than the rampant gorse and broom planted by sentimental homesick Scots.

Nearly all the people I met said they wanted to reclaim their hills and make them bald and bright again, ridding them of these alien plants and animals, to bring about the resurgence of flightless birds, vegetarians and insectivores, and to preserve the long valleys of native confiers and beeches. There have been some pleasant surprises. One guiless, ground-dwelling bird, the plump leaky takahe, which the Maoris hunted, was thought to be extinct. In 1948 some takahes were found in a remote region of Fiordland. Although protected, the bird faces an uncertain future.

Old habits of contentment, curiosity, and trust – the legacy of paradise – remain among many bird species in Fiordland. Anyone taking a walk through the rainforest will be followed by the South Island robin, the fantail, the tomtit, and the tiny rifleman, New Zealand’s smallest bird. These birds seem absolutely without fear and will flutter and light a few feet away, pecking at insects the hiker has disturbed. The key, or mountain parrot, is so confident it becomes an intruder, squawking its own name and poking into your knapsack.

So, in magnificent Fiordland, far from the dreary frugality of Christchurch and its suburbs, the birds were unafraid and all the water was drinkable; the birdwatcher didn't need binoculars and the hiker had no use for canteen.

I cheered up and decided to go for a one-week hike over the mountains and through the rain forest. I would paddle my kayak somewhere else.

The best-known long distance walk in Fiordland is the Milford Track, but it is now a victim of marketing success, and “the finest walk in the world” is simply tourist based hyperbole. It has become crowded and intensely regulated, and as a result rather hackneyed.

The Routeburn Track was my choice, because – unlike the Milford, which is essentially a valley walk with one hight climb – it rises to well above the scrub line and stays there, circling the heights, offering vistas of the whole northeast corner of Fiordland. I decided to combine the Routeburn with the Greenstone Valley Walk, so that I would have a whole week of it and so that I could enter and leave Fiordland the way people have done for centuries, on foot.

There is an intense but simple thrill in setting off in the morning on a mountain trial knowing that everything you need is on your back. It is a confidence in having left all inessentials behind and entering a world of natural beauty which has not been violated, where money has no value, and possession are a deadweight. The person with the fewest possessions is the freest: Thoreau was right.

Even my recently gloomy had lifted. I felt a lightness of spirit, and the feeling was so profound it had a physical dimension – I felt stronger and that eased my load. From the age of nine or ten, when I first began hiking, I have associated camping with personal freedom. My pleasure has intensified over the years as equipment has improved and become more manageable and efficient.

When I was very young, camping equipment was just another name for “war surplus.” Everything was canvas. It was made for the Second World War and Korea. It was dusty, mildewed and very heavy. I struggled with my pup tent. My sleeping-bag was filled with cotton and kapok and weighed fifteen pounds. Now all the stuff is light and colorful and almost stylish.

And hikers are no longer middle-aged Boy Scouts. A violinist, a factory worker, an aspiring actor, a photographer, a food writer, a student, and a grumpy little man with an East European accent made up our Routeburn hiking party. We were, I supposed, representative. Some dropped by the wayside; the photographer stayed on at one hut to take pictures, and the man who kept interrupting discussions with, “Hah! You sink so! You must be choking!” at last went home, and when we finished only three of us pushed on to the Greenstone. Isidore, the violinist, cursed the water and mud and apologized for being a slow walker, but he was better at other pursuits – he was concert master of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, and he had a knack for beating me at Scrabble during the long nights at the trackside shelters.

We started walking up a muddy track at the north end of Lake Wakitipu in sight of deer and majestic stags.

“I find it hard to view these creatures as pests,” I said.

“Vermin is not the first thing that comes to mind when you see the monarch of the glen.”

“Vermin!” Isidore said, mockingly. He had the northern Michigan habit of talking with his teeth clamped together. He soon stumblingly fell behind.

He caught up at lunch, while we were beside a stream (which we drank from). We were bitten by sandflies there and we set off again. After a horizontal stretch through Routeburn Flats, among the tawny blowing tussocks, we climbed steeply on a track that took us through gnarled and ancient beeches to Routeburn Falls. This was a succession of cataracts which cascaded over black rocks on about six levels of bouldery terraces.

From this level, it was possible to see clearly how the glaciers carved Fiordland, creating the characteristic U-shaped valleys, whose sheer walls gave them the illusion of even greater height. The dragging and abrasive glaciers smoothed the valleys’ walls, but here the ice had been about five thousand feet thick, and so the top of the mountains were jagged and sharp where the glacier didn't reach.

That night we stayed in a hut. A hut on the Routeburn Track I discovered is essentially a small drafty shelter erected over a Scrabble board. At the Falls hut that night we talked as the rain began to patter on the roof.

“How did the Maori withstand this cold?” Isidore asked, massaging life back into his sensitive violinist fingers.

James Hayward, the aspiring actor, did not have the most accurate explanations, but they were always memorable.

“The Maori kept warm by catching keas,” he said, referring to the mountain parrots. “They hollowed out the birds and strapped them to their feet and used them for slippers.”

“I sink you are choking,” came a voice. “Hah!”

James merely smiled.

“You’re talking crap, Jim,” someone said. “They’ve found Maori sandals on the trails.”

“You see a lot of interesting things on the trails,” James said. “I once saw a man on the Routeburn in a bowler hat, a pin-striped suit, a tightly rolled umbrella, and all his camping gear in a briefcase.”

He had to raise his voice, for the wind and rain had increased. It kept up all night, falling fast and turning to sleet and making a great commotion, with constant smashing sounds, pushing at the side of the hut and slapping the windows.

I played Scrabble with Pam, the student. She said that she beat most of her friends.

“You won't beat me,” I said. “Word are my business.” She was a big strong girl. She had the heaviest rucksack in the group.

“If you beat me, I’ll carry your pack over the Harris Saddle tomorrow.”

She beat me easily, but in the morning I felt sure that I would be spared the effort of carrying her pack. The rain was still driving down hard. Visibility was poor. Between swirling cloud and glissades of sleet, I could see that the storm had left deep new snow on the summit of Momus and other nearby mountains. From every mountainside, cataracts had erupted, milky-white, spurting down the steep rock faces.

“Let’s go walkabout,” James said.

The narrow footpath near the hut coursed with water and I had wet feet before I had gone ten yards. We tramped up the path in the snowy rain and wind, marvelling at how the Routeburn Falls was now about twice the torrent it had been the day before. We climbed for an hour to the hilltop lake that lay in a rocky bowl, a body of water known here, and in Scotland as a “tarn.” (”Burn” its also Scottish, for that matter, meaning “stream.”) The storm crashed into the tarn for a while, but even as we watched, it lessened and soon ceased altogether. Within fifteen minute the sun came out and blazed powerfully – brighter than any sunlight I had ever seen.

The photographer, Ian, said, “This sunlight I three quarters of a top brighter than anywhere else on earth I’ve taken pictures.”

It seems that the greenhouse effect can be measured with a light-meter.

In the dazzling light, Pam helped me strap on her fifty-pound pack and we climbed upward. Lake Harris, a few miles up the trail, was green-blue enclosed by cliffs.

Then we were above it, tramping through alpine scrub and the blowing spear grass they called spaniard. Staggering under the weight of Pam’s pack, I tottered towards Harris Saddle (4,200 feet), which stands as a glorious gateway to Fiordland. Beyond it is the deep Hollyford Valley, which winds to the sea, and hight on its far side the lovely Darren Mountains, with glaciers still slipping from their heights and new now whipping from their ridges.

The Harris Saddle was worth the long climb for the sight of panorama of summits to the west, a succession of mile-high mountains – Christina, Sabre, Gifford, Te Wera, and Madeline. I could not imagine mountains packed more tightly than this – a whole ocean of whitened peaks, like an arctic sea.

Apart from the wind whispering in the stunted scrub, there was silence here. At this height, among powerful mountains, I felt that I had left mean and vulgar things far behind, and entered a world without pettiness. Its counterpart, and a feeling it closely resembles, is that soaring sense of well-being inspired by a Gothic cathedral – not a nineteenth century New Zealand imitation, of which there were many, but a real one.

Walking along the ridge of the Harris Saddle, I had a clear recollection of the London I had left, of various events that people talked about: a steamy affair between a literary editor and one of her younger assistants; of a famous widow, an obnoxious Ann Hathaway type, who gave parties – drinkers jammed in a room full of smoke – that people boasted of attending. I saw people – writers – talking on television programs, and partygoers smoking and snatching drink form a waitress’s tray, and shrieking at each other, and talking about the literary editor and her younger lover, and then they all went home drunk. From this path blowing with wild flowers and loose snow these far-off people seemed tiny and rather pathetic in their need for witnesses.

“Bullshit!” I yelled into the air, startling Isidore until the discerned that I was smiling.

I needed to come here to understand that, and I felt I would never go back. Walking these New Zealand mountains stimulated my memory. My need for this strange landscape was so profound. Travel, which is nearly always seen as an attempt to escape from the ego, is my opinion the opposite. Nothing induces concentration or inspires memory like an alien landscape or a foreign culture. It is simply not possible (as romantics think) to lose yourself in an exotic place. Much more likely is an experience of intense nostalgia, a harking back to an earlier stage in your life, or seeing clearly a serious mistake. But this does not happen to the exclusion of the the exotic present. What makes the whole experience vivd, and sometimes thrilling, is the juxtaposition of the present and the past – London seen from the heights of Harris Saddle.

Leaving the other behind I started the long traverse across the high Hollyford Face – three hours at a high altitude without shelter, exposed to the wind but also exposed to the beauty of the ranges – the forest, the snow, and a glimpse of the Tasman sea. It was more than three thousand feet straight down, from the path on these cliffs to the Hollyford River on the valley floor. The track was rocky and deceptive, and it was bordered with alpine plants – daisies, snowberries, and white gentians.

Ocean Peak was above us as I moved slowly across the rock face. It was not very late, but these mountains are so high the sun drops behind them in the afternoon, and without it I was very cold. The southerly wind was blowing from Antarctica. As the day darkened, I came to a bluff, and beneath me in a new valley was a green lake. It was at such a high altitude that it took me another hour to descend the zigzag path.

Deeper in the valley I was among ancient trees, and that last half-hour, before darkness fell, was like a walk through an enchanted forest, the trees literally as old as the hills, grotesquely twisted and very damp and pungent. A forest that is more than a thousand years old, and that has never been touched or interfered with, has a ghostly look, of layer upon layer of living things, and the whole forest clinging together – roots and trunks and branches mingled with moss and rocks, and everything above ground hung with tufts of lichen called “old man’s beard.”

It was so dark and damp here the moss grew on all sides if the trunks – the sunlight hardly struck them. The moss softened them, making them into huge, tired, misshapen monsters with spongy arms. Everything was padded and wrapped because of the dampness, and the boughs were blackish green; the forest floor was deep in ferns, and every protruding rock was upholstered in velvety moss. Here and there was a chuckle of water running among the roots and ferns. I was followed by friendly robins.

It was all visibly alive and wonderful, and in places gad a subterranean gleam of wetness. It was like a forest in a fairy story, the pretty and perfect wilderness of sprites and fairies, which is the child’s version of paradise – a lovely Disneyish glade where birds eat out of your hand and you know you will come to no harm.

I began to feel hopeful again about my life. Maybe I didn't have cancer after all.

It was cold that night – freezing, in fact. I woke in Mackenzie Hut to frosty bushes and icy grass and whitened ferns. There was lacework everywhere, and the sound of a far-off waterfall that was like the how of city traffic.

There were keas screaming overhead as I spent that day hiking – for the fun of it – to the head of Lake Mackenzie.

The paradise shelducks objected to my invading territory, and they gave their two-tone complaint – the male duck honking, the female squawking. I continued up the valley, boulder-hopping much of the way along a dry creek bed. I was steep, most of the boulders were four or five feet thick, so it was slow going. I sheltered by a rock the size of a garage to eat my lunch. The wind rose, the crowds grew lumpier and crowded the sky. The day darkened and turned cold.

I climbed onward, and the higher I got the freer I felt – it was that same sense of liberation I had felt on Harris Saddle, remembering the trivialities of London. At the highest point of the valley face, an uplifted platform just under Fraser Col, the clouds bulged and snow began to fall. I was in a large quarry-like place littered with boulders the size of bungalows in Wellington, in a gusting wind. I decided not to linger. The commonest emergency in these parts is not a fall or a broken limb but rather an attack of hypothermia. I decided quickly, moving from rock to rock, to whip up my blood and warm myself, and I arrived back at the hut exhausted after what was to have been a rest day.

That night was typical of a stop at a trail hut. Over dinner we discussed murder, race relations, AIDS, nuclear testing, the greenhouse effect, Third World economies, the Maori claim to New Zealand, and Martin Luther King Day.

The Czech, whom I thought of as the Bouncing Czech – he had emigrated from Prague to become a businessman somewhere in California – said, “I never celebrate Martin Luther King Day at my plant. I make my men work.”

“How long have you lived in America?” I asked.

“Since sixty-eight.”

“Do you know anything about the civil rights movement in the United States?”

“I know about my business,” he said. That was true – he spent a great deal of time boasting about how he had made it big in America.

“But you’re doing it in a free country,” I said. “When you left Czechoslovakia you could have gone anywhere, but you chose America. Don’t you think you have an obligation to know something about American history?”

“As far as I am concerned, Martin Luther King is not significant.”

“That's an ignorant opinion,” I said

Isidore said, “Does anyone want to play Scrabble?”

The hut was small. I was angry. I went outside and fumed, and through the heavy mist an owl hooted, “More pork!”

I woke early and left the hut quickly the next morning, so that I wouldn't have to talk to the Czech. He was a rapid walker and what is known in camping circles as an equipment freak: very expensive multicolored gear.

It was raining softly as I set off, and roosting on a branch above the path ahead was a New Zealand pigeon.

it was like no other pigeon in the world, fat as a football, and so clumsy you wondered how it stayed aloft; it does so with a loud thrashing of wings. In the past, the Maori who walked this way snared these kereru and ate them. They needed them to sustain themselves in their search for the godly greenstone, a nephritic jade hard enough to use for knives and axes and lovely enough for jewellery. They dug these rare stone all over the Routburn Track. On that same stretch, from Mackenzie to Lake Howden, I heard a bellbird. This remarkable mimicking bird trills and then growls and grates before bursting into song. It was much admired by the Maori. At the birth of a son they cooked a bellbird in a sacred oven in a ritual of sacrifice meant to insure that the child had fluency and a fine voice.

The light rain in the morning increased to a soaking drizzle, turning the last mile on the Routeburn Track into a muddy creek. I passed under Earland Falls, which splashes 300 hundred feet down – the water coursing unto the rocky path. There was water and mist and noise everywhere, and it involved a sort of baptism to proceed. Farther down the track, the woods offered some protection from the rain, and yet we arrived at Howden Hut drenched. That is normal for Fiordland. Photography cannot do justice to rain, and so most photographs of Fiordland depict a sunny wilderness. But that sunshine is exceptional.

At Lake Howden, for example, there are roughly two hundred rain days a year, producing twenty-five feet of rain.

It was still raining in the afternoon, and yet I was looking forward to three more days walking, down the Greenstone Valley to Lake Wakitipu. It was the sort of rain that makes local enthusiasts start their explanations with if only –

“If only it weren't so misty you'd be able to see wonderful –”

Wonderful peaks, lakes, forests, cliffs, waterfalls, ridges, saddles and ravines. They were all obscure by the rain.

But the wonderful woods with their mossy grottoes were enough. This was a famous valley, one that had been pushed open when a glaciers split off from the Hollyford Valley and flowed southeast about thirty miles to Lake Wakitipu. It was another Maori route to the greenstone deposits at the top of the lake. Its presence so near the rivers and lake confirmed them in their belief that stone was a petrified fish. Greenstone had both spiritual and material significance and was cherished because it was so difficult to obtain.

Isidore still struggled along, humming Brahms. The Czech evaporated – we never saw him again – and we were joined by two New Zealanders, a courting couple, who were terrific walkers, and who tripped and pushed each other, there blobs of mud, splashed each other in the icy streams, wrestled at lunch in the tussocky meadows – kiwi courtship. And there was an elderly lawyer and his wife, from somewhere in Oregon.

Seeing the mixed bunk room at one of the Greenstone huts, the man said, “Oh, I get it. It’s bisexual!”

Not exactly, but we knew what he meant.

The Greenstone was a walk down a river valley – no snow and sleet here. After breakfast we set off together but since everyone walked at a different pace we ended up walking alone, meeting at a rest spot for scroggin (nuts and raisins) and then onward through the forest for lunch – on the Greenstone it was always a picnic by a drinkable river – and finally slogging throughout most of the afternoon toward one of the riverside huts. As the river widened to a mile or two it became louder and frothier, and the soaked graywacke stone that lay in it made it greener.

Cataracts poured from the mountains above the trail, but they were so high and the wind so strong that they were blown aside, like vaporizing bridal veils – a gauze of mist that vanished before it reached the valley floor. We were followed by birds and watched by deer and hawks and falcons. The weather was too changeable and the prevailing westerlies too strong to assure one completely rainy – or sunny – day. Clouds were always in rapid motion in the sky and being torn apart by the Livingstone Mountain at the edge of Fiorldland – for we had now left the park proper and we were making our way through Wakitipu State Forest to the lake.

The silver beeches of the high altitudes gave way to the thicker, taller red beeches of the valley and the slender and strange young lancewood trees with their downward-slanting leaves at the margin of the valley floor. We walked along the sluices of long-ago rockslides and through a forest of whitened trunks of trees killed by a recent fire, and by a deep gorge and a rock (called roche moutonnée) too stubborn for the glacier to budge, and through cool mossy woods, and knee-deep in a freezing creek – the courting couple shrieking and kicking water at each other – always followed by birds.

At the last swing bridge that trembled like an Inca walkway near the mouth of the Greenstone, where the Caples Valley converged to form an amphitheater of mountainsides, the foliage was of a European and transplanted kind – tall poplars in autumnal gold, standing like titanic ears of corn, and dark Douglas fir, and the startling red leaves of copper beeches – the trees of the New Zealanders call foreign weeds and would like to destroy, root and branch.

I was sorry to reach the end of the trail, because there is something purifying about walking through a wilderness. To see a land in the state which it has existed since it rose from the waters and let slip its ice, a land untouched, unchanged, its only alteration a footpath so narrow your elbows are forever brushing against ferns and old boughs, is greatly reassuring to the spirit.

Bush-bashing on these tracks had stimulated my imagination, and the vast landscape had a way of putting human effort into perspective. The smaller one feels on the earth, dwarfed by mountains and assailed by weather, the more respectful one has to be – and unless we are very arrogant, the less likely we are to poison or destroy it. In the Pacific the interlopers were doing the most damage – bringing nuclear waste to Johnston Island, digging a gigantic copper mine in Panguna in the North Solomons, stringing out miles of drift nets to trap and kill every living creature that came near its ligatures, testing nuclear devices at Moruroa Atoll in the Tuomotus.

But this too was Polynesia – this rain forest, these Southern Alps. Te Tapu Nui, the Maori called their mountains. “The Peaks of Intense Sacredness.”

#P14#The Happy Isles of Oceania#Paddling the Pacific#Part One: Meganesia#New Zealand: Sloshing through the South Island#Paul Theroux

0 notes

Photo

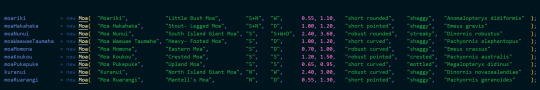

North Island giant moa bones collected in 1993, housed at the Auckland War Memorial Museum in Auckland, New Zealand. [ x ]

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me at Auckland museum with the North Island giant moa skeleton, a lorge boye. Also feat. bust of English dude Sir Richard Owen who was the first European to correctly identify a moa fossil (their existence and extinction was already widely known by Māori).

#selfie#me#girlslikeus#moa#dinornis#dinornis novaezealandiae#gothgoth#him tol#skeleton#femme#transisbeautiful#amab - all moa are beautiful#wlw#Richard Owen#museum#North Island giant moa#Auckland museum

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

School kids in New Zealand discovered a giant penguin fossil with long legs

https://sciencespies.com/nature/school-kids-in-new-zealand-discovered-a-giant-penguin-fossil-with-long-legs/

School kids in New Zealand discovered a giant penguin fossil with long legs

Ancient New Zealand has been home to an incredible array of absurdly large birds. This has included a waist-high parrot, nicknamed Squawk-zilla (Heracles inexpectatus) – the largest parrot ever known on Earth, possibly hunting for flesh around 20 million years ago.

Two-meter-high flightless Moa also made their home there, along with their predator, Haast’s Eagles (Hieraaetus moorei), with a monstrous 3-meter wingspan, around 2 million years ago.

Now researchers have added a new giant penguin to this gloriously super-sized menagerie – one discovered by a lucky group of school kids back in 2006.

“It’s sort of surreal to know that a discovery we made as kids so many years ago is contributing to academia today. And it’s a new species, even!” said Steffan Safey, who was one of the children on the Hamilton Junior Naturalist Club’s field trip at the time. “Clearly the day spent cutting it out of the sandstone was well spent!”

Within a now solidified layer of what once was muddy siltstone, the students discovered the fossilized remains of the towering penguin’s torso, leg, and arm bones.

Massey University paleontologist Simone Giovanardi and colleagues have now examined and formally described the find, found in rock from around 30 million years ago, in Kawhia Harbour on the North Island of New Zealand.

“The penguin is similar to the Kairuku giant penguins first described from Otago but has much longer legs, which the researchers used to name the penguin waewaeroa – Te reo Māori for ‘long legs’,” explained zoologist Daniel Thomas from Massey University.

“These longer legs would have made the penguin much taller than other Kairuku while it was walking on land, perhaps around 1.4 meters tall, and may have influenced how fast it could swim or how deep it could dive.”

An analysis of living and extinct members of the penguin’s family trees suggests these species reached their large proportions independently from each other. Natural selection seems to have an interesting habit of shaping birds into giants when they’re isolated in a habitat free of predators.

Somehow, when Zealandia split from Gondwana 80 million years ago, it was (or soon became) free of predatory mammals, making it an ideal melting pot for such evolutionary experiments.

At least 10 known ancient giant penguins have been found on this continent, including the 60-million-year-old, 1.6-meter-tall Crossvallia waiparensis discovered in 2019, and 30-million-year-old Kairuku waitaki, that’s related to the new find.

Some researchers suspect after having survived the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago, penguins were able to take advantage of the lack of giant marine predators.

Left with plentiful resources needed to support bigger bodies, they were able to expand into new ecological niches – an ecological phenomenon called mesopredator release.

This roughly coincided with their shift into becoming flightless divers – flight would also have constrained their size. And without predatory land mammals around, the giant penguins had a safer place to breed in Zealandia.

Comparing the fossil to other species, Giovanardi and team note that following K. waewaeroa there was a trend towards shorter legs in this group of penguins. The change in body length may decrease the bird’s surface/volume ratio and the surface area for parasites, both of which would reduce drag for their underwater flight.

Once other marine predators like sharks and marine mammals got big during the Eocene and Oligocene, any edge provided by swimming faster would have become a vital advantage again for these birds.

“Kairuku waewaeroa is emblematic for so many reasons,” explained Thomas. “The fossil penguin reminds us that we share Zealandia with incredible animal lineages that reach deep into time, and this sharing gives us an important guardianship role.

“The way the fossil penguin was discovered, by children out discovering nature, reminds us of the importance of encouraging future generations to become kaitiaki [guardians].”

This research was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

#Nature

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

coral & mauve :)

coral: an animal you wish hadn't gone extinct

I was going to say Haast's eagle, but that thing could potentially carry infants away; so, the North Island giant moa.

mauve: any unpopular opinions?

Bikinis are practically underwear.

Color Asks

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Origins of giant extinct New Zealand bird traced to Africa

Scientists have revealed the African origins of New Zealand's most mysterious giant flightless bird – the now extinct adzebill – showing that some of its closest living relatives are the pint-sized flufftails from Madagascar and Africa.

Led by the University of Adelaide, the research in the journal Diversity showed that among the closest living relatives of the New Zealand adzebills – which weighed up to 19 kilograms – are the tiny flufftails, which can weigh as little as 25 grams. The closeness of the relationship strongly suggests that the ancestors of the adzebills flew to New Zealand after it became physically isolated from other land.

This finding mirrors the close relationship between New Zealand's kiwi and the extinct Madagascan elephant birds, published by University of Adelaide researchers in 2014, hinting at an unappreciated biological connection between Madagascar and New Zealand.

Like the better-known moa, the two species of adzebill – the North Island adzebill and South Island adzebill –disappeared following the arrival of early Maori in New Zealand, who hunted them and cleared their forest habitats. Unlike the moa, adzebills were predators and not herbivores.

"The adzebill were almost completely wingless and had an enormous reinforced skull and beak, almost like an axe, which is where they got their English name," says Alexander Boast, lead author and former Masters student at the University of Adelaide. "If they hadn't gone extinct, they would be among the largest living birds."

#South Island Adzebill#Aptornis defossor#North Island Adzebill#Aptornis otidiformis#St. Bathans Adzebill#Aptornis proasciarostratus#Aptornis#Aptornithidae#Sarothruridae#Gruiformes#Aves#birds#adzebill#flufftail#ornithology#evolution#extinction#New Zealand

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Very Cool! Thank you😁❤️❤️❤️❤️

The world’s largest eagles

Eagles are birds of prey synonymous with strength, power, and tenacity. They are gracious birds used as national symbols in many countries such as the United States and Japan. In the avian kingdom, eagles can be found at the very top of the food chain. Their ability to adapt to endemic environments has made them very successful birds in terms of hunting down prey and weathering the harshest environmental conditions. These heavily built birds have attracted interest from scientists and researchers who study their unique adaptations and habitats.

Haast’s eagle, 300 cm (118 inches)

The Haast’s eagle is currently an extinct species that once lived in the southern islands of New Zealand. It was the largest eagle to have lived during its time and the most ferocious predator in its ecosystem. It had wings that were suited to flapping and maneuvering in the dense forest vegetation. The Haast’s eagle preyed on flightless birds such as moa.

This giant eagle weighed up to 17.8 kg and had a wingspan of 3 meters. Due to its large size and the continuous decline of flightless birds, it approached the maximum size limit through evolution, and this ultimately led to its extinction.

Steller’s sea eagle, 250 cm (98.4 inches)

Steller’s sea eagle is one of the largest birds of prey found in the coastal areas of northeastern Asia where its main prey is fish and sea birds. It is a powerful and heavily built bird with bright contrasting colors. It is covered with black feathers for the most part except on the wings in the shoulder area and the legs and lower body which are much brighter.

It has a wedge-shaped tail which is longer compared to the white-tailed eagle. The Steller’s body length ranges from 85 cm to 105 cm while the wingspan ranges between 1.95 m to 2.5 m. It has bright yellow beak and talons.

White-tailed eagle, 244 cm (96 inches)

The white-tailed eagle is the largest European eagle and has a bright white tail while the rest of the body is almost entirely brown in color. It has a conspicuous head and beak which protrude forward giving it almost a vulture-like profile. The legs, feet, eyes, and beak are yellow. It has a wingspan of 193-244 cm and a length of between 74-92 cm.

The white-tailed eagle can be found in a wide range of habitats such as lowlands and close to water bodies. They hunt and prey on a wide variety of mammals, fish, and birds. Fish is the major diet while mammals such as fox, sheep roe deer have been recorded as regular prey

Australian wedge-tailed eagle, 230 cm (7.55 inches)

The Australian wedge-tailed eagle is the largest bird of prey in Australia and New Guinea. It is also known as bunjil or the Eaglehawk. It has a long wingspan of up to 2.3 meters and the characteristic wedge-shaped tail. The feet are covered with feathers up to the base.

It has a pale beak, white feet and dark brown color around the eyes. The bunjil weighs between 3.2 kg and 5.3 kg with the females being heavier than the males. This bird can be found in the sea-level regions and the mountainous regions. It is dominantly found in open lands, wooded and forested landscapes.

Golden eagle, 220 cm (7.23 inches)

The Golden eagle is the most popular national bird in countries such as Germany, Austria, Mexico, and Albania. It is very common in the Northern hemisphere and the most widely found eagle species. It is the most powerful bird of prey in North America and known for its swiftness and strength. It is dark brown in color with golden brownish color around their necks and head.

It feeds on small mammals such as jackrabbits and can sometimes attack large mammals such as lambs, goats and other domestic animals. It has a wingspan of 185-220 cm and weighs between 3.1 kg-6.2 kg. The Golden eagle can be found in open country with natural vegetation which allows it to spot prey easily. They also prefer elevated areas such as mountains, riverside cliffs, and canyonlands. Currently, the Golden eagle population appears to be stable.

Philippine eagle, 220 cm (86.6 inches)

The Philippine eagle is the largest and heaviest known eagle. As the name suggests, it is endemic to the rainforests of the Philippines. It is a relatively unknown bird mostly because of its exotic origin and the small wild population. This eagle is currently faced with the danger of extinction due to habitat exploitation. It is endemic to four main islands in the Philippines such as Luzon, Mindanao, Samar, and Leyte.

There are between 82-233 mating pairs in the island of Mindanao where a majority of the population is found. It has long, brown feathers on its head which form an impressive mane-like appearance. The Philippine eagle, also known as the great monkey-eating eagle, has a wingspan of between 184-220 cm and a body mass of 4.5kg-8kg.

Since July 1995, the Philippine eagle became the national animal of the Philippines. Although considered the largest eagle, it does not have the longest wingspan due to its habitat preferences of thick forests and woodlands which require limited wingspans for maximum maneuver in the condensed spaces.

Harpy eagle, 200 cm (78.7 inches)

The harpy eagle is a powerful bird of prey and one of the largest in the world. It has huge, strong talons that can compare to a bear’s claws and its legs can be as thick as a human’s wrist. With a wingspan of up to 2 meters, it’s a good navigator across Central and South America.

The harpy eagle is the national bird of Panama. A long tail, broad and rounded wings allow the harpy eagle to navigate the rainforests of South America. Like many forest raptors, its wings are well adapted to the forest canopy and enable it to dodge through branches.

The adult harpy eagle has black feathers on the main body and grey head and neck. It preys on medium sized arboreal mammals such as sloths and monkeys.

Martial eagle, 193 cm (75.8 inches)

The Martial eagle is one of the most impressive African eagles and the largest and most powerful bird of prey in Africa. The martial eagle weighs in at 6.6 kg and has a wingspan of more than 6 feet 4 inches long. It has dark brown upper parts and white belly with black streaks.

It has very powerful talons for tearing and holding prey. Its diet is mainly mammalian, preying on small antelopes, domestic goats, hyrax, and lambs. On various occasions, the Martial eagle has been recorded preying on large birds such as the European stork. Its habitat includes the African savannah and thorn bush regions on the south cape. It breeds on the edge of the forest.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Last stop for the day, Kiwi North. This is a museum and Kiwi House in Whangarei housing a nocturnal habitat where they keep kiwis that need rescue. The museum is worth a look but the highlight is the nocturnal house where your eyes need to adjust to the low light conditions for at least 15 minutes. Two little “furry” birds were housed when I went through and it took a while for my eyes to adjust.

Memorable in the museum are the bones of the Giant Moa bird, many reaching 12 feet in height. This flightless New Zealand North Island bird became extinct in and around 1400 due to over hunting by the Maori.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Time for the next round!!! It’s time to vote in the BIRD SPECIES that WILL be the competitor in this year’s Dinosaur March Madness!!!! All eligible species ARE LISTED. Please READ the below information so that you make an informed voting choice! You have through February 4th!!!!!!!!

HIGHLIGHTS & INELIGIBLES

Giant Moa

The giant moa were two of the largest known moa - a group of large flightless birds from New Zealand, closely related to modern tinamous, which mainly fed on low lying vegetation in their environment. They were some of the dominant herbivores of New Zealand, and only went extinct a few thousand years ago due to human hunting.

The two species are the North Island Giant Moa and the South Island Giant Moa. They differ primarily in that they come from different islands of New Zealand - with the North Island Giant Moa coming from the northern island, and the South Island Giant Moa coming from the southern island, but in addition to this, the South Island Giant Moa was also the biggest known moa, and the tallest known species of bird.

List of ineligible candidates: None

Ducks, Geese, & Relatives

The anatids - ducks, geese, swans, and their relatives - are waterfowl that feature heavily in everyday life. Primarily herbivorous, they feed on water plants in a variety of habitats, such as lakes, ponds, and wetlands. They have webbed feet, short pointed wings, and bills that are usually flattened. Some species, the mergansers, are piscivorous, using serrations on their bills to catch fish. Many of them undergo very large annual migrations, and some have been domesticated. They come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, with many have long slender necks, and most also having short and strong legs for swimming - though they’re relatively awkward walking around on land.

Highlighted species include the Hooded Merganser (a diving duck in which the male has a conspicuous black-and-white head crest), the Kauaʻi Mole Duck (an extinct Hawaiian duck that had poor eyesight, likely foraging on land by smell and touch), the Northern Shoveler (an unmistakable duck with a spatula-like bill, very specialized for feeding on plankton), and the Trumpeter Swan (the largest living waterfowl).

List of ineligible candidates: None

Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds are a group of highly specialized birds that include some of the most spectacularly colored and smallest dinosaurs known. They have extremely strong hearts and wings specialized for hovering, which they can flap at very high speeds to allow for them to hover and procure nectar from flowers much like bees and butterflies—in short, they’re dinosaurs that convergently evolved with insects. Males are, typically, smaller than females in the smaller hummingbirds, and larger than females in the larger hummingbirds. They have the highest metabolism of any animal to support their rapid wing beats. Their colors serve to compete for both territory and mates, and is primarily brilliantly colored in male hummingbirds - and they even use the sun to enhance their sheen.

Highlighted species include the Marvelous Spatuletail (in which the males have a pair of extremely long tail feathers with expanded tips), the Sword-billed Hummingbird (which has a bill longer than the length of its body), the Xanthus’s Hummingbird (which has white “eyebrows” and is found only in Baja California), the Long-billed Hermit (in which the males have dagger-like bills for fighting), and the Anna’s Hummingbird (in which the males perform diving displays reaching 385 body-lengths per second and make sounds using their tail feathers).

List of ineligible candidates: Bee Hummingbird, Vervain Hummingbird

Turacos

Turacos are a group of poorly flighted African birds that feature a wide variety of weird plumages and pigmentations, including some of the only truly green pigments found in animals (rather than green due to iridescent sheen and/or combinations of other pigments). They evolved perching ability similar to, but independently from, perching birds and parrots, making their feet an interesting example of convergent evolution. Though they are weak fliers, they do run about the trees very rapidly, and make a lot of noisy alarm calls to each other. They are some of the weirdest and prettiest known birds, in terms of both names and plumage.

Highlighted species include the Great Blue Turaco (the largest species of turaco, with bright blue plumage, yellow tail feathers, an interesting black tufted crest on its head, and a red band on its beak), the Guinea Turaco (an actually true green bird with a fluffy crest on its head and bright red rings around its eyes), the Bare-Faced Go Away Bird (which not only has one of the best names of any dinosaur, but also has a literal bare face and it is very noisy and restless), and the Red-Crested Turaco (which is very small, true green, and has a red crest as well as tiny wings that are red underneath—seriously, so smol).

List of ineligible candidates: None

Cranes

Cranes are a group of birds that tend to be large or very large in size, and often quite tall. They have long legs and necks and often nest near water. Some species migrate long distances. Cranes are omnivores and forage on the ground or in water. They maintain strong pair bonds, often mating for life. New pairs engage in elaborate dances prior to mating. Most species have a long, coiled windpipe that allows them to produce loud, trumpeting calls.

Highlighted species include the Grey Crowned Crane (known for having a crown of stiff golden feathers on their heads and a red inflatable throat pouch), the Siberian Crane (one of the rarest cranes, almost pure white except on places along the wings only visible in flight, males and females are known for streaking mud through their feathers for display in breeding season), and the Sandhill Crane (known for soaring flight and one of the longest fossil histories for any living bird, with the oldest fossil being 2.5 million years old).

List of ineligible candidates: Wattled Crane, Blue Crane, Demoiselle Crane, Red-Crowned Crane, Whooping Crane, Common Crane, Hooded Crane, Black-Necked Crane, G. afghana, G. antigone, G. nannodes, G. haydeni, G. penteleci, G. bogatshevi, G. latipes, Maltese Crane, G. pagei, G. primigenia

Auks

Auks are a group of seabirds that use their wings to swim and dive underwater where they feed on fish and plankton. This makes them similar to penguins, despite not being closely related. (Indeed, the term “penguin” was actually first applied to auks.) Unlike penguins, auks live in the Northern Hemisphere and all extant species can fly. However, they need to flap very quickly during flight due to their short, paddle-like wings. Auks spend most of their lives at sea, typically only coming ashore during breeding season. They often mate for life and generally nest in large colonies.

Highlighted species include Miomancalla (a prehistoric flightless relative of auks and the largest known shorebird), the Atlantic Puffin (known for its bright orange bill and spends a large portion of its time in open ocean), the Ancient Murrelet (which spends less time on land than any other bird, with juveniles making their way to the sea at only 1-3 days old), the Crested Auklet (known for its strange forehead crest and smelling strangely like citrus), and the Dovekie (a very small auk that is completely adorable).

List of ineligible candidates: Great Auk

Herons

Herons are a group of predatory wading birds with long legs, long bills, and long necks. Members of this group that have mostly white plumage are often known as “egrets”. Herons typically hunt by standing and waiting for prey to come within reach, before spearing the hapless victim with their beak. Most species feed primarily on fish, but they will generally eat any animal small enough to swallow. Herons possess specialized down feathers that grow continuously and disintegrate at the tips, forming a powder that helps the birds remove grease from their plumage while preening. Many species grow ornamental plumes during breeding season, and they generally nest in trees (though the well-camouflaged bitterns tend to nest in reed beds instead), sometimes in large colonies. Unlike many other long-necked birds (such as storks and cranes), herons fly with their necks folded back rather than outstretched.

Highlighted species include the Boat-billed Heron (has a large, broad black beak for feeding on shrimp and small fish), the Eurasian Bittern (known for communicating with very deep calls and camouflaging itself by freezing with its bill in the air to mimic reeds), the Green Heron (known for keeping its neck close to its body until it strikes at prey like a harpoon, as well as using small objects such as feathers to bait fish), and the Goliath Heron (the largest heron in the world, almost never moves away from water).

List of ineligible candidates: None

Hawks, Eagles, & Relatives

The majority of diurnal birds of prey are members of Accipitridae, including kites, hawks, eagles, and Old World vultures. They are found on every continent except for Antarctica and have adopted a wide variety of lifestyles. Collectively, they are known to prey on everything from insects to large mammals such as deer. They generally have extremely powerful feet and large talons that they use to capture and kill prey. Accipitrids have extremely keen eyesight, able to perceive objects at higher acuity from far greater distances than humans can. In most species, the females are larger than the males and mated pairs often pair for life.

Highlighted species include the Palm Nut Vulture (unusually for an accipitrid, it primarily feeds on oil palm fruit), the Haast’s Eagle (a massive extinct eagle that preyed on moa, and believed to be the Pouakai of Maori legend), the Swallow-tailed Kite (a very graceful flier known for its long, forked tail and nests in wooded areas or near wetlands), the Steller’s Sea Eagle (one of the largest eagles and feeds primarily on fish, though it is known to prey on seabirds as well), and the Harris’s Hawk (one of the few raptors that hunts in packs, popular in falconry due to its intelligence).

List of ineligible candidates: Harpy Eagle, Bearded Vulture

Typical Owls

Strigidae includes most modern owls other than barn owls and their close kin. Owls are primarily nocturnal birds of prey. The long feathers on their face form a disk that helps collect sound and direct it towards their ears. They use their large eyes and sensitive hearing to hunt at night, and most species have specialized wing feathers that allow them to fly silently while approaching prey. They are generally cryptically colored to help them avoid larger predators and smaller birds that may harass them during the day. Females are usually larger than males, and most species seem to maintain long-term pair bonds.

Highlighted species include Ornimegalonyx (an extinct genus believed to be the largest owl to exist), the Snowy Owl (a popular and well recognized owl known for its white plumage, was one of the original species of birds described by Linnaeus himself), the Eurasian Eagle Owl (one of the largest living and most widely distributed species of owl, has prominent ear tufts), the Northern White-faced Owl (nicknamed the “transformer owl” for its defensive behaviors such as puffing its feathers when facing a relatively small predator and pulling its feathers inward and narrowing its eyes for camouflage when faced with a larger one), and the Northern Hawk Owl (one of the few owls that is only active during the day).

List of ineligible candidates: Spotted Owlet, Little Owl, Forest Owlet, Burrowing Owl, A. megalopeza, A. veta, A. angelis, A. trinacriae, A. cunicularia, A. cretensis

Kingfishers

Kingfishers are a group of often brightly-colored birds that have dagger-like bills and short legs. They are predatory and most species hunt by watching from a perch. When prey is spotted, they swoop down to catch it in their bill before beating it to death against a hard surface. Though some kingfishers do indeed eat fish, many species primarily feed on land animals. They have keen eyesight, and species that fish are able to account for the effects of water refraction and reflection when diving for prey. Most kingfishers nest in burrows, though some use tree holes or dig cavities in termite nests.

Highlighted species include the Shovel-billed Kookaburra (a large kingfisher with a uniquely short, broad bill), the Common Kingfisher (well-recognized kingfisher found widely across Eurasia and Northern Africa, has a greenish-blue or blue body), the Guam Kingfisher (extinct in the wild, only surviving birds are in a captive breeding program), and the Pied Kingfisher (known for commonly bobbing its head and flicking its tail when perched as well as hovering while searching for prey, often groups in large numbers at night to roost).

List of ineligible candidates: Rufous-Bellied Kookaburra, Spangled Kookaburra, Blue-Winged Kookaburra, Laughing Kookaburra

Toucans

Toucans are a group of tree-dwelling birds most notable for their very long and slender bills, which contrast heavily with their, in general, short and compact bodies. Their bills are very colorful, with their light weight allowing the birds to hold them up, given their tiny bodies and short necks; they also have serrations which aid in feeding on fruit that can’t be reached by other birds. In addition, the bills are great for thermoregulation, allowing the toucans to release heat from the bill. They also might use the large bills to actually intimidate other birds and steal eggs and babies from their nests. They have very long tongues - like their close relatives the woodpeckers - that allow them to find food deep in trees. Their tails are also highly adapted - with the vertebrae fused and attached with a ball and socket joint, allowing the tail to jut forward towards the head. They are very social birds in the tropics, and they may fight with their bills and chase each other while they digest food.

Highlighted species include the Toco Toucan (the largest and arguably best known toucan, has a black body and brightly colored beak), the Curl-crested Aracari (has a distinct short crest of curled feathers along the top of its head), and the Plate-billed Mountain Toucan (known for two distinct colorations between the northern and southern members of its species, northern toucans have brown eyes and orange on the upper beak while southern toucans have violet/green eyes and yellow and pink on the upper beak).