#obon

Text

Beautiful outfit put together by Mai_Waka for last Halloween. Yet, the komori (bat) and hozuki (physallis) are traditional summer motifs in Japan, perfect for the Obon (festival of the dead) season !

#japan#fashion#kimono#obi#summer in japan#obon#hozuki#physallis#ground cherry#komori#bat#halloween#着物#帯

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sean bienvenidos, japonistasarqueológicos a una nueva entrega, en esta ocasión hablaré sobre Obon el festival de los difuntos una vez dicho esto pónganse cómodos que empezamos.

-

En Japón, en los días de agosto, del 13 al 16, se celebra el Obon, que lo podemos ver en multitud de animes, películas y doramas ya hice mención sobre que estas cosas no solo hay que verlas, como meros dibujos, ya que tienen mucho sentido cultural e histórico. Esta festividad tiene muchos elementos muy característicos como el Gozan no Okuribi también llamado Daimonji, muy característico de finales de estas fiestas, porque suelen ser una serie de dibujos alguno de un torii y otros como el kanji de fuego, por mencionar algunos ejemplos.

-

Los pepinos(se utiliza para cuando el difunto llega) y berenjenas(caso contrario cuando el difunto se va ) simbolizan la llegada y el regreso del difunto al más allá. Hay muchos países que celebran esta festividad de formas distintas, pero todos tienen en común que honran a sus antepasados, es una festividad que tiene 400 a 500 años de antigüedad y es de origen budista. Para finalizar la publicación mencionaremos el Awa-Odori, (Odori significa bailar) y data del siglo XVI.

-

Espero que os guste y nos vemos en próximas publicaciones, que pasen una buena semana.

日本の考古学者の皆さん、新しい回へようこそ。今回はお盆についてお話ししましょう。

-

日本では、8月の13日から16日にかけて、お盆の行事が行われる。 アニメや映画、ドラマなどでもよく見かけるが、これらは単なる絵空事ではなく、多くの文化的、歴史的な意味を持っていることはすでに述べた。例えば、五山の送り火は「大文字」とも呼ばれ、鳥居の絵や「火」という漢字の絵など、お盆の風物詩となっている。

-

キュウリ(故人が来るときに使う)とナス(故人が帰るときに使う)は、故人があの世に到着し、戻ってくることを象徴している。この祭りをさまざまな方法で祝う国はたくさんあるが、先祖を敬うという点では共通している。阿波踊りは16世紀に遡る。

-

それでは、良い一週間を。

Welcome, Japanese archaeologists to a new installment, this time I will talk about Obon, the festival of the dead, and with that said, make yourselves comfortable and let's get started.

-

In Japan, in the days of August, from the 13th to the 16th, Obon is celebrated, which we can see in many anime, movies and doramas. I have already mentioned that these things should not only be seen as mere drawings, as they have a lot of cultural and historical meaning. This festivity has many very characteristic elements such as the Gozan no Okuribi also called Daimonji, very characteristic of the end of these festivities, because they are usually a series of drawings of a torii and others such as the kanji of fire, to mention some examples.

-

Cucumbers (used for when the deceased arrives) and aubergines (otherwise when the deceased leaves) symbolise the arrival and return of the deceased to the afterlife. There are many countries that celebrate this festival in different ways, but they all have in common that they honour their ancestors, it is a festival that is 400 to 500 years old and is of Buddhist origin. To end the publication we will mention the Awa-Odori, (Odori means dancing) and dates back to the 16th century.

-

I hope you like it and see you in future publications, have a nice week.

#日本#歴史#文化#オタク#アニメ#お盆#阿波踊り#五山の送り火#大文字#ユネスコ#祖先#Japan#history#culture#otaku#anime#Obon#AwaOdori#GozannoOkuribi#Daimonji#unesco#ancestors

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mizore Ito (Misery-chan) - Summer Festival

My character Mizore Ito (Misery-chan)

The friendly phantasms are back and full of summer festival mischief! 🏮👻👺

Mizore's Toyhouse Profile

While working on this piece, I felt inspired by the song chakachaka by Mayumi Kojima:

Mayumi Kojima - chakachaka

Done with Clip Studio Paint EX

August 2023

#art#original art#oc#original character#Mizore Ito#Misery-chan#Japan#Japanese#summer festival#summer matsuri#matsuri#祭り#夏祭り#Obon#お盆#ghost#ghosts#yokai#youkai#cute#creepy cute#summer#yukata#mask#妖怪#幽霊#原创#浴衣#Japanese ghost#my art

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Peony Lantern

The Peony Lantern

The evening air still held the heat of the day. In the distance, Shinnojo Ogiwara could hear the music from the festival, filtering up the narrow street, interspersed with faint adult laughter and high piping children’s voices. Earlier, he had gone to the shrine and left his offering for his wife. She was dead many years now. His daimyo had had a hand in their marriage, bringing the two families together, and Ogiwara had never had any complaints about her. She had been an easy woman, easy with her smiles, easy with her care, easy to grow to love. She had made life easy, for him and later for their children. She had died easy too, slipping away quietly after a quiet sickness.

His grief for her had been easy as well, just as quiet and simple to slip into the pattern of as she had been.

His love for her had been a samurai's love. It had not taxed him or drawn his attention away from his duties. It had been, like her, an easy thing. Easy to pick up, easy to set aside when duty called for it. He had thought losing her was easy as well. Too easy he sometimes worried but his children had needed him and his lord had needed him and life had gone on and she had become an easy memory, soft but not demanding in his chest. When he had left his offerings earlier for her, he had been grateful that even her loss, she had made easy on him.

He wasn’t sure why he was standing outside his town house, feeling so very -

Lonely.

In life, you accepted what you were given by the Wheel of Fate. He had always been stoic, dealing with what was in front of him. He had not been created to be a dreamer, a poet. He was his daimyo’s rock, steady, reliable and unimaginative. He knew that. It was something he could, and often was, proud of. Yet here, in the quiet warmth of the evening, feeling the cotton of his yukata sticking to the skin between his shoulder blades, hearing a celebration he could not find it in him to join in the distance, he felt as if he had missed something, somewhere along the way. He felt - restless. Lonely and restless.

His children were all gone. He’d given them better lives to go to. His lord surrounded himself with younger men these days. The countryside was quiet. There was no need to ride out and defend anything. Ogiwara felt as if time was slipping past him now and he had nothing left to do with it. Some of his friends, the ones that had survived their youth, had joined monasteries, preparing themselves for their eventual death and turn on the Wheel but Ogiwara couldn’t bring himself to do that. Not yet. He was still too young for that. Too old for his past life yet too young for his future one. Caught like a toad in tree sap, trying to move yet having nowhere to go. He fought the feeling but it was a gradual growth inside of him, harder to ignore when the world was silent as it was now. Day by day, month by month, it slowly ate away at his heart.

He had given his life to his lord and his duty, to first his father and then his children. He had held nothing back from them and now, when they did not need him, he realized he had nothing of himself left for himself. What did a man do, when he had nothing but himself left?

On the street outside, a light bobbed. He frowned at it. He had thought the street was empty only moments ago and yet, as if pulled up out of the cobbles by his thoughts, suddenly there was a lantern. He had thought everyone else was at the celebration but now, moving - no, floating along, there was a golden pink light, shaped fanciful into a peony flower. For just a moment, as he recognized the lantern’s shape, he even thought he could smell it, the flower, not the lantern. Absentmindedly, he watched it drift closer to him in the evening covered street. It seemed to be coming from a very far way away, so much farther away than the small stretch of street it drifted across and it flickered as it came, sometimes dipping out of existence entirely before bravely flickering back to life, the golden pink glow of it immeasurably fragile in the dark shadows around it. In his mind, he knew it was only a peony painted lantern, carried by some noble’s servant to light their steps in the evening darkness.

Something in his chest still held his breath each time the light disappeared and silently cheered encouragement each time it stubbornly came back to life after.

In time it resolved itself, growing steadily brighter and more sure of itself and, following behind its light, came the soft clacking of wooden shoes on stone, faint and strangely melodic in the night air, like spring rain falling on bamboo chimes. Again he smelled a floral note in the air and, enchanted by the strange fancy his mind was making of such a mundane event, he inhaled it deeply. Every moment was fleeting. He had learned early to enjoy what moments came while they were there - even, perhaps now, an older man’s suddenly awake imagination that painted an evening with a god’s brush for a few seconds of time. Foolish perhaps, but who was there to see it but himself?

As he thought it, the lamp came close enough that he could see what it cast its light for and his chest suddenly closed over entirely as his world seemed to spin sideways and then stop entirely.

She was beautiful.

Ogiwara had been to the Shogun’s palace before. He had been to the Emperor's palace. He had seen the most beautiful women in the land gathered together, dressed in the most elegant silks opulence could give them.

They looked like sparrows held up against the hawk that glided behind the peony lantern.

She was physically beautiful. She was physically so much more than beautiful. Poets made songs around skin as moon glow beautiful as hers and wrote plays over the darkness of her hair and the bottomless darkness of her eyes. But there were other women in the world with moon skin and night fall hair and midnight shadow eyes. What made her beautiful, Ogiwara thought, watching her glide along serenely behind the peony lantern carried by her scuttling servant girl, was how she moved. She didn’t trip along gaily, light like a young coltish girl, new as morning dew to the world and all it held. Nor did she melt along, a woman of the world who was used to being adored, content in her circle of attention, doted on to the point of becoming alabaster. No. She moved like the hawk he had first thought of, drifting on the wind under the power of her own wings, all of her contained and drawn from only inside of herself, sure of the place she had created before her as she moved into it. She moved, he thought, like an empress that had never known an emperor.

It made her beautiful enough to stop his heart.

Standing silent at his garden gate, he doubted they saw him as they approached on the street and then slipped past him. He never knew what made him open his mouth but the words had to be said, whether anyone but the night heard them or not. As the pink gold glow from the peony lantern passed like a pool in front of his garden gate he whispered:

“What a lucky man I am. For dawn has decided, early, to rise and then pass in front of my lowly garden gate and only my eyes are here to see it.”

It was a clumsy poem. He’d never been good at moon reading nights in his diamyo’s gardens or at petal parties when the trees came into bloom. He lacked the ability for word play that could turn one sentence into three different meanings and he was too sturdy with his chosen words for flight. Still, he knew when a moment called for a poem and this evening was a kind of magical beauty that needed to be remembered and marked properly.

The soft tak-tak of the woman’s shoes stopped. In the shadow and light from the lantern, for a moment, her skin was as golden pink as the light. She did not turn her head toward him, eyes dark pools in the shadows of her face. For a moment, it was quiet. Even the sounds of the festival were gone in the evening air. And then:

“What a lucky woman I am. For someone has mistaken my lonely wind-blown candle for the hope of a morning dawn and, almost, only my ears are here to hear it.”

The lady’s voice was low and soft, too deep to belong to a young girl and there was a sweet accent touching the final edges of each of her words, a half-heard song in the fall of them. The servant holding the lantern was bent low in the lady’s shadow but she was a second set of ears. Ogiwara found it unique that the lady would acknowledge that. In the magic of the gold and pink tingled evening, it was a strange thing, like a window left open before a rainstorm. The light around the woman paused, the shadow around the servant girl did as well. Ogiwara found himself outside of both. He was a widower and neither poor enough to need a second wife, nor wealthy enough to afford a mistress. He had never seen the woman in front of him before. Her voice though, like her movements, ran sure as river water of itself before her and his chest ached in a way he had never felt before, like a tongue burned by snow for the first time somehow wants to prolong the feeling.

“The walls of my house are sturdy shelter,” he said, not sure which answer he hoped to hear. “If a candle needed a place to rest from the wind for a time.”

Her face did turn toward him then and there was light in the darkness of her eyes like sunlight across rippling river water. Barely, the tips of her pale lips lifted, such a small thing and yet he felt the burst of pride inside his chest, that he was the cause of it.

She paused, a single long moment, and then she, carefully, lifted the very low hem of her dress and stepped from the street up to his garden walk. The click of her shoes was soft in the darkness.

He smelled flowers. She was not much shorter than he was.

“A candle, brought in from the wind, glows brighter once it is safe.”

“My walls are safe but not fire resistant,” he pushed the gate open and marveled that he could speak in more than just words for once. “Let us bring the candle in.”

Her name was Otsuyu. She did not give him a family name. Perhaps she was a nobleman’s wife, recently moved to the town. Perhaps she worked for one of the upscale teahouses. She did not tell him and he did not ask. The world outside, celebrating Obon, did not matter to them. Instead, she sang for him and he had the servants make the tea for her that he usually saved for his diamyo’s visits. They talked of books he had only half read and plays she had only half watched and, together, they laughed, softly, for the life they’d not noticed passing them by in those moments. She was older than his children, younger than he was and her smiles and laughter were fleeting, making each moment he caused one to be a moment of pleasure for himself. She wove poetry out of the small decorations he’d collected to hang in his house and he folded little pigs for her out of paper he’d been using for ink blotting, feeling foolish until her delighted laughter at the little speckled creatures filling her moon-glowing palms made the air sweet. When he reached for her, she came, skin cool against his in the heat from the summer air. Her servant waited on the other side of the screen and the gold and pink glow from the peony lantern, slipping past the paper wall was the only light in the room as Otsuyu opened her arms and drew him down to her on his bed.

“Your moon skin is cool,” he told her and her voice in the dark whispered back:

“So warm me with your own.”

He did.

She did not slip away after, content to rest with her head on his chest and his fingers tangled in her hair and he felt something stir in his chest that felt dangerous. It felt alive again.

She did stir, just before dawn, rising and drawing her robe around her. He rose with her and added his own over hers and she did not refuse it. Something dangerous bubbled in his chest again. If felt like hope.

“To keep the moon warm,” he told her as he draped it around her shoulders. The light from the lantern on the other side of the wall was starting to fade and it was very dark where they stood close together in his room.

“It is a fine robe,” she told him, fingers touching its fabric and then his chest and he felt something thud painfully on the other side of his rib cage from where her fingers glided like falcon feathers.

“It is,” he agreed. He’d been wearing it to the festival. You dressed your best for those kinds of things. Her hair was dark across the shoulders of it now and he reached up to lift it back. Last night had been a poet’s tale but the day was approaching and life wasn’t a poet’s work. Still, he couldn’t resist adding: “I have more. If a candle should need another.”

In the dark, he felt her look more than saw it. Her hands came to rest on his arms, light as the morning dew surely forming outside. For a moment, it was quiet. And then:

“How often should I come?” her low voice whispered in the dark. He felt the way it coiled down through him and realized, as short as the night had been, he had only one answer:

“Forever.”

In the dark she gave a moment to the word, felt the way they both heard it ring, soft and yet deep as a monastery bell lost in the mountains between them.

“How long will you wait?” she asked. He realized there was only one answer he wanted to give.

“Forever.”

The word hung in the air a second time, sinking deep. She lifted and her lips pressed to his. For a moment, he tasted earth, deep and dark and cool. Then she was drawing away in the dark, slipping out of the room and the fading light of the peony lantern slipped away with her. Ogiwara stayed where she had left him until dawn was already creeping under the shutters of his windows.

It’s light was beautiful but not as beautiful as the light from the peony lantern.

The day crawled past. It was still Obon so he had no solicitors, no headmen, to deal with but there were still correspondences to be dealt with. There were invitations from friends.

He left them where they lay on his desk and sat out in the garden as the day slowly inched past.

Ogiwara was good at waiting. It was what made him such an asset to his lord and what made him such a stable samurai - but he had never felt as stretched thin as he did while the day crawled its agonized way past him. Corpses on the battlefield, he thought, moved faster as they settled in to rotting. He wished he had asked Otsuyu for something of hers, a hair comb or a slip of silk. In the light of day, the night previous seemed hard to believe in, full of the longing certainty and logic that only existed in dreams. She had said she would come again but polite words were creatures of their own, slipping nooses and forest traps to find their escape. As sturdy as he was, he knew there were other samurai that offered more. Lords that offered more. Last night, thinking of their own personal dead, perhaps they had both been lonely and so found each other that way. Tonight, he would again be lonely, he thought, but that was not enough to offer a woman like Otsuyu.

He rose and ordered a feast prepared for that night. Not the kind you invited friends to, with ample food and drink. He ordered the kind of food that might please a single person, a woman who traveled with a fanciful peony for a lantern. Sweets and delicates and light foods that would be cool in the heat of the evening. He ordered flowers. Not an excess but the rare ones that were more beautiful for being individuals in their vases. He had his futon changed out, brought down the one, and the quilts, he saved for special guests, kept in storage with their sweet herbs and silken covers. He ordered the house cleaned, top to bottom, sent his servants to buy new tatami mats even though it wasn’t the season for them. He was not rich but he was not poor and he had no reason to spend money on himself. Let him spend it on her.

On the hope of her.

If she did not come…

If she did not come it would be ash in his mouth.

But if she did?

If she did he would give her what she was worth for as much as someone like him could.

The afternoon came on and he found a strange clenching in his stomach, one he recognized, with surprise, as both excited anticipation and held back dread. It was a new feeling to him. He had felt both before, but never together. He was surprised to find he almost enjoyed the pain.

“Quite a lot of activity in your house.” It was his neighbor, Satsuo, and he said it as Ogiwara stepped outside his gate to make sure the step up into it was level and swept clean. “My servants tell me you’re expecting someone. Is your wife coming back to check on you?”

Satsuo was too nosy, a palace official that had retired, or been retired, and spent his days trying to remember how it felt to order others around. They were not on bad terms, he and Ogiwara. They had both watched the world pass them by and there were evenings when there was comfort in sitting together with sake between them, pretending it hadn’t. For that, Ogiwara accepted the prodding half-joke and gave him the politeness of a response.

“My wife has no reason to come back. She finished well here.” And, because of their friendship, he could add: “Beside, if she did come back, it would be to check on her children. There is no need for her to check on me.”

Behind him, in the courtyard of his home, the cook’s voice rose for a moment before muttering back out over one of the baskets brought from market by a servant boy.

“A man is only worth the children he leaves behind,” Satsuo intoned before he slipped another look at Ogiwara. “You look strange, my friend. I would swear you were waiting for an Obon ghost. Who is the fuss your house is making for?”

“I feel strange,” Ogiwara admitted, something he wouldn’t usually have done but - there was a great deal today he would not usually have done. What was one more thing? “But there is no lonely ghost coming. I am waiting for the moon to fall tonight.”

The fanciful statement left his neighbor stuttering and, for the first time, Ogiwara felt the power in word poetry on his own tongue. Satsuo pried more but there was nothing more to tell him and so Ogiwara did not. If she came tonight - she would come. If she did not -

The moon might as well fall for him. He had no thoughts beyond that.

The day slipped away and as evening came on, Ogiwara sent his servants to bed or to their own families. He had no need of them. There was nothing he could not provide for Otsuyu himself. What little he might need, her servant could provide.

And - if she did not come - he needed no one but himself there to witness it.

He took his position by his garden gate as the shadows lengthened into sunset.

Satsuo tried to wait with him but Ogiwara was a samurai and his neighbor was only an official. It was not hard, without saying a word or making a gesture, to make it clear his company was not welcome. His neighbor slipped away into his own house, murmuring evening words, after only a short attempt.

Ogiwara waited.

Evening fell.

The last of the sun disappeared.

Night slipped quietly forward on slippered feet to spread its darkness.

Ogiwara stood under the single lantern he’d left lit near the gate and watched the moon start to rise. Behind him, in the silent house, the food sat in its dishes, waiting for someone’s touch. Ogiwara waited as well.

Though the soft night came a faint sound.

The soft tak tak of wooden shoes over stone.

A glow, golden pink, drifted to him along the empty street.

Ogiwara stopped breathing.

Again, the light seemed to come from much further away than where he knew it must have rounded the corner of the street to be visible. As it had last night, it bobbed in and out of sight, extinguished one moment, appearing again the next. This time however the sound of wooden soles attended it, falling like water drops even when the light wasn’t there to guide them. Steady and sure and coming to him.

It was far too long before he saw the whisper of silk and darkness and the moon-pale hint of Otsuyu’s beautiful face. Without willing it, he smiled and she raised her bottomless dark eyes to his - and smiled in return. It was a quiet smile, a small one, but it was private and for him only. His heart jerked to life in his chest again, painful and welcome, and he held out his hands for hers.

Moon skin, just as cool and pale, slipped in to fill them.

He could breath again.

And, perhaps he just imagined it, but her eyes looked just as relieved as his felt.

He led her into his silent house and her servant brought the golden pink glow of the peony in with them.

The moon had come to Ogiwara’s house again, and there was no wind strong enough to threaten to blow it out.

Again, she left before dawn and, again, he did not ask where she went or who she went to. If she wanted to tell him, when she wanted to tell him, she would. It was enough for him that she had come.

That she promised to come again.

He let her go and, as dawn rose, he finally slept for the first time in two days. Under the light of the morning sun, he slept well.

He woke when his servants came to tell him there was a priest at his gate. It was true, Ogiwara hadn’t gone to the temple yesterday to leave food for the spirits of his ancestors. As he washed and dressed, he admitted that he should be taken to task for such a misstep. While he had left offerings the first day of the festival, he had neglected his family duty the second. His food had been prepared for Otsuyu instead. He felt the guilt of that - but not the regret. He would tell the priest he would make up for it today. Tonight the spirits would be guided back to the underworld, following their lanterns. Ogiwara hadn’t lied about his wife. If she visited at all, she visited their children. But there were other ancestors and he would be sure they were properly honored before their ghosts drifted away into the darkness, following the floating lanterns back to the sea.

The last thing he wanted, now that he had found Otsuyu, was a lingering spirit causing harm because it had been neglected.

He met the priest in the garden, where the older man waited, even though Ogiwara had told his servants to bring him inside and give him something to eat and drink. To his surprise, his neighbor was there as well. He gave Satsuo a look but the other man ducked it and kept the priest between them.

For the first time in many years, Ogiwara was aware of the weight of his swords. He always wore them when greeting visitors. He said it was to honor his guests but anyone that studied history knew better. It had been habit, not thought, that had put them on him to greet the priest. Seeing Satsuo using the robed man as a shield, Ogiwara stepped clear of the overhang of his roof and rested lightly on the balls of his feet as he greeted the two.

The proper greetings were exchanged, the offer of tea was turned down, pleasant conversation about the festival filled space. The priest was not here about Ogiwara’s offerings. He didn’t even mention them or their lack. Instead, face grave, he finally came to the purpose of his visit.

“Samurai Shinnojo I believe you are in the kind of danger that only I can protect you from.”

Ogiwara let his hand fall to the hilt of his sword. It was a samurai’s work to protect himself and others. If the priest was here, that meant the threat he mentioned was not physical. He had come about the offerings after all.

That didn’t explain Satsuo’s presence.

“How am I threatened?” he asked and now Satsuo finally exhaled a breath that shook and stepped forward.

“I saw your guest last night, Shinnojo. I was curious. You were so secretive. I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw who was visiting you in the night. You were right to call her the moon.”

It wasn’t something that pleased him to hear but Ogiwara couldn’t pretend he was surprised. Satsuo had been an official. It had been his life to put his nose into every corner of other’s lives. He should stop now that he wasn’t an official anymore but Ogiwara knew how hard it was to leave behind the habits of your past.

It didn’t mean he felt like sharing Otsuyu, not even in conversation. All he did was nod in response. The priest took over.

“Your neighbor has been watching out for you. On Obon, ghosts roam the streets, looking to cause mischief and harm. Your neighbor, fearing for your safety, peeked in one of your windows once the woman came inside.” Ogiwara sent Satsuo a look and it was enough to have the man hiding behind the priest again. Everyone there knew Satsuo’s peering had nothing to do with worry over Ogiwara’s safety.

“Shinnojo-san, you are sleeping with a ghost,” the priest said.

Ogiwara snorted before he could stop himself. The priest was too old to be offended.

“I apologize,” he told the old man. “Whatever my neighbor has told you,” he glared at Satsuo, “for whatever reason, is a waste of your time. My visitor last night was living.”

Satsuo surprised him them, actually coming around the priest and, more shocking, going to his knees in a bow. His voice shook but even Ogiwara would be lying if he did not call it sincere.

“My friend, we have lived next to each other for years. I swear to you on every single day that has passed between us, I have not lied. Yes, I spied on you and the lady. I was greedy for your experiences. But I swear to you, I swear it - when I looked, you had your arms around a skeleton, living flesh to rotting and another rotting corpse sat in the corner with a flower lantern. Cut off our friendship. But do not let that creature into your house again tonight. I will beg.”

It would have been easy to dismiss Satsuo. It was what, with his whole chest, Ogiwara wanted to do. The man had intruded into things that weren’t his place and worse, he spoke against something that Ogiwara…

That Ogiwara wasn’t sure he wanted to go back to living without. Otsuyu made him feel again. He had forgotten what that had felt like.

Except Ogiwara was a samurai. Emotions weren’t what was important. Emotions were a trap. He knew that. And, finally, he understood why. Because it tore deeply inside of him to ignore them now. He still wasn’t sure he forgave his neighbor. Instead, he looked over the man’s lowered head at the priest.

“What should I do?”

The priest told him.

Again, Ogiwara prepared for the coming evening.

The day passed too fast. Long before he was ready, the shadows of the day were stretching into the quiet darkness of the evening, lit only by the distant trails of people carrying their lanterns down to the river, to set them adrift to guide the spirits back to their proper place in this world.

Ogiwara stood in the center of his garden and he waited.

Across his gate, almost lost in the growing darkness of the night, a simple paper ofuda fluttered, restless in the breeze.

Inside his garden, Ogiwara could not see the street. If the peony lantern appeared and fought its way through the dark to him tonight, he could not tell.

What he did hear, as the night settled low over the buildings, was the soft tak tak of wooden shoes approaching in the darkness.

It sounded, now that he listened, like fingers of bone, trying to find a way in past the wooden shutter of a window.

The sound came to a stop outside his closed gate.

The world, buried under distant stars, seemed to hold its breath in silence for a very long, thin-stretched exhale of time.

She was out there, on the street, having come expecting his lit lantern to guide her to his gate and him waiting for her. Instead, she had found darkness and the gate closed against her. Ogiwara stood in the darkness, halfway between the house and the gate and listened. His heart felt dead in his chest and yet his ears still strained for the damning sound of her shoes, clicking away from him forever into the darkness. Instead, after a moment, it was her voice that slipped in, finding its way easily through the wood without lifting.

“My lord,” a question and a call and he felt something stab him deeply, anger and longing. He was being a fool, keeping her out there for no reason but a spying neighbor. And yet - he waited.

“My love,” she called it softly again and it caused prickles to run over his skin. On its own, his mouth started to open but he shut it. There was the soft sound of her steps, clicking low in the night. One step that brought her almost to the gate.

“Ogiwara,”it was too much.

“Otsuyu,” her name was somewhere inside him, a curse or a prayer or a cry and it strangled between all of them as it came out of him. It told her he was there. He couldn’t bear the thought of her thinking he had abandoned her to the night.

“Won’t you open the gate for me, Ogiwara?” she asked him and there was a tremble in her voice he’d never heard before. It hurt. She should not tremble. Not a woman like her.

“Won’t you open the gate and come in, Otsuyu?”

That was the question. A mortal woman would be able to step past the protective charm on the gate.

A ghost would not.

If she was mortal, she only had to step inside and he would love her for the rest of his life.

If she wasn’t -

What would he do if she wasn’t?

Step through, he silently begged her. Make a fool of me and a priest and a neighbor with too much time on his hands. Step through and come to me. The silence beyond the gate waited.

He could not see the golden pink light of the peony lantern.

“I cannot,” she finally whispered and the wood of the gate took her voice and made it hollow.

The rice paper building he had been creating of hope fell inside of him without a sound. He closed his hand over his sword hilt. He had felt anger moments ago. Where had it gone?

“Why me?”he asked the darkness and the darkness answered softly.

“You were lonely. And searching. As lonely and searching as I was. I was lost and fading and you offered me shelter and strength. When I am with you, I am - happy. I don’t remember what I was before but - I do not think I was ever happy. Not as I am with you.”

“What were you going to do to me?” that came out rougher, the anger coming back for a moment. She whispered words that made his heart ache - but if her body had been a lie, why not her words too, all the more painful because he wanted them to be true? “Eat me? Kill me? Suck all my life away and leave a husk behind? Tell me, Otsuyu,” his voice shook now and it was with anger. “What were you going to do to me after I had loved you?”

“Ogiwara,” his voice was a sigh full of tears as it slipped past the gate. “I was going to love you. Forever. Just as you asked.”

It stole the anger from him, drained it in a rush like a sudden wound sweeping all the blood from his body. He felt old. And cold. And as if he would weep. She was dead and he was alive yet he felt as if he were the one dying. He had no words left for her.

She filled the silence between them instead. Like the wind, it crooned low and thin between the cracks of the gate.

“Shinnojo Ogiwara, you said I could come to you forever. But now the warmth you once gave me has been stolen away by your newfound coldness and I am again as lonely as the moon you once compared me to. You said you would wait for me and yet your gate is closed to me and your heart offers me no more shelter. I am a dim candle and soon the wind will snuff me out forever. Yet I cannot hate you. With you I have felt a life I did not feel even when alive. I hope it torments you for the rest of your life, that you have left me out here in the dark and cold, abandoned and alone. I hope you remember for the rest of your life that you are the one I will love long after I have finally reached my turn at the Wheel. I love you, Ogiwara. I love you. I love you. I love you.”

Her voice died down into a silence that wept it was so brittle and lost. There was no other sound from the darkness of the gate. She was gone.

Gone.

Gone and he was alive. Tomorrow the sun would rise. He would live. He would live tomorrow and the day after and the day after and he would never hear the soft clack of wooden soled shoes outside his gate or inhale peony from a woman’s skin.

His life would go back to what it had been before Obon.

His house would be empty again.

He would be empty again.

Love, real love, was a curse. It tore a man between his duty to his woman and to his lord. But there was no lord that needed him anymore and the curse was that love lost was more painful than love never known.

He strode across his yard to the gate and he knew each step that he took was a decision he was making. He made it, over and over, until he reached the wood and ripped the gate open.

Outside, in a pool of golden pink light, Otsuyu waited for him with eyes as bottomless as the cold sea and as full of precious liquid.

“You didn’t leave?” he asked and it was raw and breathless in his throat. She gave him her small smile, somehow, past the tears in her eyes.

“You told me I could come to you forever.”

“Otsuyu,” another decision, one that was easier to make than it should have been, had him past the barrier of the gate and had her crushed close to him in his arms. She made a little sound, laughter and tears and despair and buried her decayed face against his shoulder. He smelled old earth. He smelled peony. He smelled rot. He smelled moonlight. Tears wet the fabric of his robe and he held bones and he held a soft hawk of a woman. He said her name again and did not let go. He felt her fingers in his robe and she did not either.

Time stopped mattering.

Eventually though, still unwilling to let go of her, he freed one arm, reaching out to rip the ofuda loose from his gate. Her fingers, barely there on his arm, stopped him before he could.

“No,” she whispered against him. “It is too late for that. I cannot return to pretending to be alive.”

He settled his arm around her and let what she meant sink past what she had told him.

Another decision.

Again, it was far too easy to make.

“Then where?”he asked.

Finally, she drew back from him and she was the form he had known the first night. Reaching down, she took his hand in her moon pale one. Her eyes were very dark when they looked up at him.

“All that is left for us is my home now.”

Her home. The dead didn’t have houses. They had graves. Ogiwara took one last look back at his own house, giving himself that moment to remember. Remember all that had come before, all that he had been. He exhaled. Looking down at the woman in front of him, all shadows and peony light, he nodded.

“Let’s go.”

The next morning, Satsuo was horrified to find his neighbor’s gate swinging open and the man’s servants looking in vain for their lord. Ogiwara wasn’t hard to find though. Not if you knew where to look.

Satsuo and the priest found him in the graveyard, lying at the foot of a grave with a smile on his face. As dead as the skeleton half buried in the ground of the grave that he had his arms wrapped around.

The Peony Lantern, also called Botan Dōrō, is considered one of the three great ghost stories of Japan. Imported from China in a book of mortality tales, the Peony Lantern was rewritten in 1666 by Asai Ryoi and the story became, and remains, wildly popular since then. A myriad of rewrites of the story have gone on to spawn plays, movies, books, dramas and manga. It’s a horror story, it’s a love story, it’s a warning, its a wish.

Please forgive the cultural mistakes I’ve made (and any editing mistakes, I just finished this and haven't had time to let it sit long enough to edit it). I hope you enjoy my gift of this version of The Peony Lantern. All reblogs of this are greatly appreciated and the best response possible. Happy Halloween.

#the peony lantern#botan doro#ghost story#happy halloween#paranormal#folklore#original fiction#short story#original story#fanfic#please reblog if you enjoy it#halloween gifts#obon#obon festival#samurai#this turned out to be 18 page long#which is about 13 pages longer than I thought it would be#I hope you enjoy it#short story fail

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

お盆 (Obon)

The aftermath:

#sleepy bois inc#technoblade#philza#miss trixtin#tommyinnit#wilbur soot#mcyt#fan art#obon#digital drawing#digital art#drawing#i'd planned to put more effort into this but oop it's already obon

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lantern Lights

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

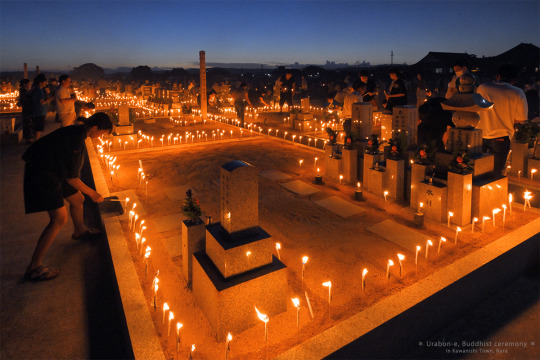

【墓会式】

一度拝見したいと思っていた墓会式へ。

各家の墓地の周りに家族が灯火を立て

墓地が綺麗というのも変ですが幻想的な光景が広がっていました。

こちらの共同墓地では屋台が出て

小さな子供たちも楽しみながら

家族そろってお墓参り。

ご先祖さまも喜ばれ、良い風習だなと思いました。

川西町八ヶ郷墓地(はっかごうぼち)にて撮影

2023年8月11日

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

⋆͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏Oh! JiNSeok

#oh jinseok#jinseok#oh jinseok icon#oh jinseok icons#jinseok icon#jinseok icons#obon#obon icon#obon icons#boys24#boys24 icon#boys24 icons#oh jin seok#oh jin seok icon#jin seok#jin seok icon#the heavenly idol#the heavenly idol icon#the heavenly idol icons#jungshin#oh jungshin#jungshin icon#jungshin icons#oh jungshin icon#oh jungshin icons#Spotify

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

All aboard the feeling train! A short one this time.

#madatobi#madara uchiha#senju tobirama#tobirama senju#uchiha madara#naruto#mdtb#tobirama#naruto founders#madara#obon#ao3#illogical writes

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

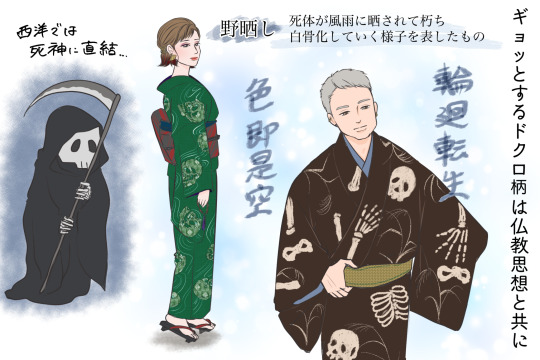

Lovely article+illustrations by Kimono Ichiba (via Tanpopo <3), overviewing famous "scary"patterns... which are in fact often auspicious as traditional Japanese patterns ;)

I believe I have them all on the blog somewhere but it's nice having them in one place so let's go!

Spiderwebs (kumo no su)

In ancient China, spider were seen as auspicious messengers connecting Heaven to Earth.

As the spider catches its prey in its web, spiderweb came to signify "grasping happiness".

Apparently during Edo period, prostitutes and geisha used spiderweb patterned items as a good luck charm (meaning something like "this customer will come back").

A very famous spiderweb depiction is the Lady Rokujo ukiyoe [焔 honô (the flame of passion)] by female artist Uemura Shoen. Wisteria caught in the web could mean ``I hope [Prince Genji] will come tonight'' which is pretty sad considering her story T_T

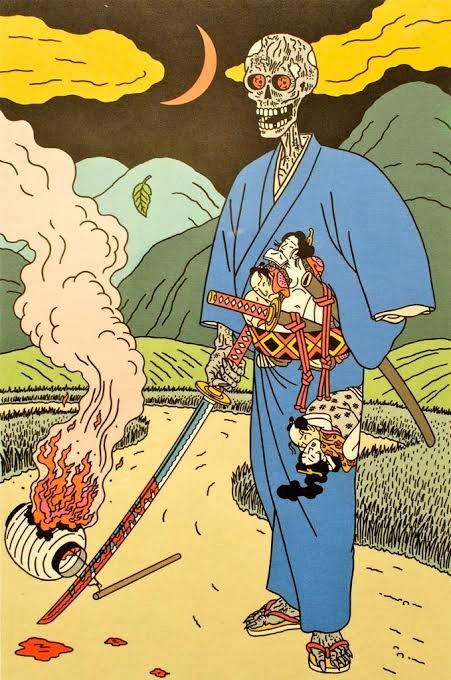

Skulls (dokuro)

Exact name for human remains pattern is "nozarashi" (lit. "weather beaten") ie bones scattered in a field. This depicts a corpse turned to bones/unveiled from its grave by the elements.

Skulls are thought to ward off evil and bad luck. Bones can also symbolize a do-or-die spirit, or hope for rebirth after death.

OP stresses a theory linking bones pattern to a buddhist saying 色即是空 shikisokuzekū "form is emptiness, matter is void, all is vanity". An interpetation is that we'll all turn to dust one day so we're all equal.

Bones patterns are often seen during Obon (Festival of the dead) season.

Monsters, ogres and ghosts (yôkai / oni / yûrei)

Monsters patterns were then worn to ward off bad luck and evil spirits. Reasoning is: let's repel scary things by wearing an even scarier monster!

Fearsome monsters were especially use by people with dangerous jobs, like Edo period firemen.

Firemen often had the lining of their heavy fire attire (火事装束 kajishouzoku) embelished with lavish designs of brave heroes and fantastic monsters. It was both a talisman and a way to show that they did not fear danger or death.

Another reason behing monsters patterns is the Edo period love for "scary" entertainements, be it ghost stories, parlor or other types of games, art (see for ex. Utagawa Kuniyoshi), etc. And Edo city dwellers were all about being fashionable so a monster pattern would have been considered quite iki!

#japan#art#history#pattern history#kimono#obi#halloween#spider#spiderweb#kumo#kumo no su#skull#skeleton#dokuro#nozarashi#weather beaten bones#obon#monster#youkai#oni#ghost#yurei#firemen#kajishouzoku#kaidan#ghost stories#Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai#One Hundred Supernatural Tales#Kimodameshi#Test of courage

374 notes

·

View notes

Text

#legends arceus#pokemon legends arceus#pearl clan leader#diamond clan leader#obon#2023#maxie ancestor#archie ancestor

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

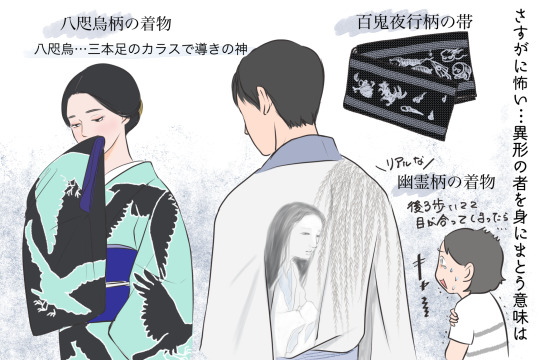

Sean bienvenidos japonistasarqueologícos a una nueva entrega para finalizar el Obon se realizan los llamados Gozan no Okuribi, tambien conocido como Daimonji se realizan el día 16 de agosto.

-

Espero que os guste y nos vemos en próximas publicaciones, que pasen una buena semana.

-

Welcome Japanese archaeologists to a new installment to end the Obon, the so-called Gozan no Okuribi, also known as Daimonji, are held on August 16.

-

I hope you like it and see you in future publications, have a good week.

-

日本の考古学者の皆さん、お盆の締めくくりとなる新たな行事、いわゆる五山の送り火(大文字としても知られています)が 8 月 16 日に開催されます。

-

気に入っていただければ幸いです。今後の出版物でお会いできることを願っています。良い一週間をお過ごしください。

-

#日本#歴史#文化#オタク#アニメ#お盆#阿波踊り#五山の送り火#大文字#ユネスコ#祖先#Japan#history#culture#otaku#anime#Obon#AwaOdori#GozannoOkuribi#Daimonji#unesco#ancestors

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

my localization of mtgjp's comic

#mtg#magic the gathering#localization#gravecrawler#dread wanderer#obon#this makes me want to go back to old comics#and translate them#but theres literally hundreds

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

お盆 (o-bon)

Every August Japan celebrates o-bon, the time of year when ancestors return to the world of the living. People celebrate by lighting fires, holding special dances in the town square, and visiting their family graves.

#Japan#japanese#japanese culture#japanese art#asian art#Japanese Calligraphy#Japanese calligraphy#calligraphy#japanesecalligraphy#japaneseCulture#obon#o-bon#japanese festival#japanese festivals#お盆#お盆休み

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes